Abstract

Against the backdrop of global climate governance and China’s “dual carbon” goals, carbon emissions trading (CET) has become a core policy instrument for promoting low-carbon transformation. However, it remains unclear whether CET policies can effectively improve corporate carbon performance and, more importantly, through which micro-level mechanisms such effects operate within firms. To address these gaps, this study applies a difference-in-differences (DID) approach to examine the impact of CET policy on corporate carbon performance and its transmission pathways. The results show that CET policy significantly enhances corporate carbon performance. Heterogeneity analysis further reveals that this positive effect is more pronounced in regions with lower environmental governance intensity, and that the policy’s effectiveness strengthens over time. Mechanism tests indicate that financing constraints and R&D investment serve as chain mediators: CET policy alleviates financing constraints, stimulates R&D investment, and thereby improves carbon performance. Moreover, the moderating effect analysis shows that executives’ green backgrounds reinforce the policy’s effectiveness by further easing financing constraints and mitigating their negative impact on R&D investment. Overall, these findings deepen the micro-level understanding of market-based environmental regulation and provide policy implications for optimizing CET policy design, improving resource allocation efficiency, and fostering low-carbon transformation and sustainable competitive advantages for enterprises.

1. Introduction

Since the Industrial Revolution, intensive human activities have led to a sharp increase in greenhouse gas emissions, resulting in global warming that poses severe threats to ecosystems, economic development, and human well-being. In response, the international community has made concerted efforts to address climate change. Landmark initiatives such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the Kyoto Protocol, and, more recently, the Paris Agreement have established global mechanisms to control carbon emissions, promote low-carbon development, and encourage market-based environmental governance. Under these international frameworks, carbon pricing instruments such as carbon taxes and emissions trading systems (ETS) have been widely implemented in jurisdictions including the European Union, the United Kingdom, and South Korea.

Against this global governance backdrop, China has progressively strengthened its climate commitments. Since 2011, China has launched pilot carbon emissions trading (CET) schemes in seven provinces and cities, followed by the announcement of a unified national market in 2017. In 2020, China pledged to achieve carbon peak by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060, and in July 2021, officially inaugurated its national CET market, initially covering the power generation sector. By 2024, cumulative trading volume in the national market had exceeded 48 billion yuan. As a key market-oriented instrument, CET has become a central pillar of China’s low-carbon transition strategy and provides an important policy context for examining its impact on corporate carbon performance.

As a market-incentive environmental regulation tool, the CET policy internalizes the negative externalities of corporate carbon emissions by setting total carbon emission caps, allocating emission quotas, and establishing a market trading mechanism [1]. This not only encourages low-emission enterprises to profit from selling their carbon allowances but also compels high-emission enterprises to implement carbon reduction measures [2]. Moreover, it conveys signals of corporate environmental responsibility to alleviate financing constraints and, according to the Porter hypothesis, drives companies to increase R&D investment, achieving “innovation compensation” through low-carbon technology innovation [3]. Importantly, the CET policy is fundamentally designed to facilitate high-quality, low-carbon development, rather than merely achieving emission reductions.

However, although prior studies have extensively examined the policy’s impact on emission abatement [4,5,6,7], they have paid insufficient attention to its influence on corporate carbon performance. This represents a notable research gap, because carbon performance emphasizes the overall efficiency of carbon management and better reflects whether firms achieve substantive low-carbon transformation beyond mere compliance. Unlike emission-reduction outcomes, carbon performance captures a broader set of dimensions, including economic and environmental benefits and the extent to which carbon management aligns with corporate strategy and operational systems [8]. Accordingly, carbon performance, operationalized in this study as carbon efficiency measured by revenue per unit of emissions, provides a parsimonious and comparable indicator for assessing whether environmental regulation promotes efficiency-oriented low-carbon transformation, yet it remains insufficiently examined in CET-based empirical evaluations.

Moreover, higher-order theory indicates that characteristics of the executive team influence the corporate response strategy to environmental regulations, with executives having a stronger green background more likely to transform policy pressure into strategic opportunities [9]. Building on these insights, this study employs a difference-in-differences (DID) model, using data from publicly listed companies in China from 2010 to 2020, to deeply investigate the core questions: “How does the CET policy affect corporate carbon performance? What are the mechanisms of its impact? Does the executive green background play a moderating role in this?”.

This study finds that CET policy significantly enhances corporate carbon performance. Furthermore, the positive effect of CET policy on corporate carbon performance is more pronounced in regions with low environmental governance intensity, and this effect becomes more pronounced over time. Additionally, further analysis of the mediation reveals the underlying mechanisms. On one side, CET policy enhances corporate carbon performance by easing financing constraints. On the other side, CET policy stimulates companies to increase R&D investment, thereby improving corporate carbon performance. Furthermore, a chain mediating mechanism exists, where CET policy alleviates financing constraints, which in turn boosts R&D investment, ultimately improving corporate carbon performance. Additionally, the results of the moderation effect analysis indicate that the executive green background significantly strengthens the effectiveness of CET policy in alleviating financing constraints and mitigates the negative impact of financing constraints on R&D investment. This moderating role enhances the efficiency of the mediated pathway from “relief of financing constraints to increased R&D investment” significantly amplifying the policy’s impact on improving corporate carbon performance.

This study offers three key contributions. First, this study positions this contribution as confirmatory with extension by evaluating CET effectiveness through an efficiency-oriented corporate carbon performance metric rather than relying solely on emission-reduction outcomes. While carbon performance has been discussed in prior work, empirical assessments often rely on either disclosure-based indicators (e.g., carbon disclosure scores) [8,10,11] or single-dimension performance metrics (e.g., emissions intensity) [7,12,13]. Building on these established approaches, we operationalize corporate carbon performance as carbon efficiency (operating revenue per unit of emissions) and explicitly benchmark this proxy as a parsimonious, policy-relevant, and cross-industry comparable measure that complements disclosure- and intensity-based metrics, especially when firm-level emissions disclosure is incomplete or inconsistent. By doing so, the study clarifies what is incremental versus novel: it does not redefine carbon performance conceptually, but provides a transparent and scalable measurement strategy. Moreover, this study fills an empirical gap by scrutinizing the heterogeneous factors affecting corporate carbon performance. Previous research primarily centered on environmental regulations [14,15], innovation [16,17], and market demand [5,10]. We highlight the significant, yet previously underexplored, influences of regional environmental governance intensity and policy duration on corporate carbon performance, thereby enriching the analysis of dynamic changes in corporate environmental strategies.

Secondly, this study contributes significantly by delineating the mediating mechanisms through which CET policy impacts corporate carbon performance. Existing literature primarily investigates the effects of CET policy concerning environmental behavior [17], economic gains [18,19], and technological advancements [4,20]. However, enhancing corporate carbon performance necessitates sustained investments in environmental and R&D sectors, with financing constraints often posing substantial barriers. Innovatively, the research introduces the perspective of financing constraints, examining their role as a link between CET policy and corporate carbon performance. We explore how policy-driven alleviation of financing constraints affects the allocation of resources within enterprises, thus clarifying the chain-mediated impact of financing constraints and R&D investments on the effectiveness of CET policy in improving corporate carbon performance. Ultimately, by investigating these multifaceted mechanisms, the study offers a comprehensive understanding of the intricate relationship between CET policy and corporate carbon performance.

Thirdly, this study unveils for the first time the positive moderating mechanisms through which executive green background enhances the effectiveness of carbon reduction policies in improving corporate carbon performance. It reveals that these background strengthens the policy’s role in alleviating financing constraints and reducing their inhibitory impact on R&D investment, thereby positively moderating the mediating chain from financing constraints to R&D investment to carbon performance. This finding not only expands the boundaries of research into policy effects by incorporating executive characteristics but also offers practical insights for corporations looking to optimize their executive team structures and enhance their responsiveness to policies.

2. Literature Review and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Literature Review

2.1.1. Carbon Emissions Trading Policy

CET policy is a market-driven environmental instrument that internalizes corporate emission cost through carbon allowances, driving carbon reduction. This policy has long been a focus of academic attention, with its impact on enterprises being a key research topic. Current studies mainly concentrate on the effect of CET policy on company innovation and carbon reduction.

The conclusions on the impact of CET policy on innovation are not consistent among scholars. Some support the Porter hypothesis, suggesting that CET policy significantly promotes innovation [21]. Wang et al. (2023) argue that environmental regulation stimulates corporate innovation [22], with productivity gains from innovation offsetting compliance cost [23]. Additionally, corporate innovation can reduce carbon emissions [24], and when emissions are reduced to a certain level, enterprises can sell surplus carbon allowances to gain additional revenue, which can be reinvested in low-carbon technology innovation, creating a positive feedback loop [25]. Conversely, other scholars support the compliance cost hypothesis, asserting that CET policy increases compliance cost [26], hindering technological innovation [27]. Zhang et al. (2021) suggest that a company’s reaction to CET policy is contingent upon the expenses associated with acquiring carbon allowances and the cost related to carbon-reducing technology innovation [28]. When carbon prices are high, spending on carbon allowances crowds out R&D investment, thus affecting innovation [29]. Additionally, Zhao et al. (2024) note that under limited carbon allowances [30], bankruptcy or relocation may become options for energy-intensive industries in response to CET policy.

Concerning the influence of CET policy on reducing carbon emissions, scholars generally conclude that the two are positively related [12,31,32]. At the national level, Bel and Joseph point out that under CET policy, appropriately reducing the distribution of CET quotas can effectively achieve carbon reduction [33]. Furthermore, the integration and optimization of the CET market can reduce GDP losses in countries with high emission control cost, thereby promoting carbon reduction [34]. Across different regions, Zhou et al. (2019) concluded that China’s CET policy decreases carbon emissions in pilot areas through industrial restructuring [12]. After the industrial structure has been restructured, the proportion of fossil energy usage decreases, thus changing the energy consumption structure, and further achieving carbon reduction in the pilot regions [35]. At the enterprise and industry levels, existing literature indicates that CET policy leads to a decrease in carbon emissions by influencing corporate investment decisions [17], technological innovation [36], and green transformation [37].

2.1.2. Carbon Emissions Trading Policy and Corporate Carbon Performance

Existing literature mainly explores the significance of CET policy in determining carbon performance from the perspectives of corporate environmental behavior, economic benefit, and technological innovation. First, CET policy internalizes emission expenditure, motivating companies to attain carbon reduction [15]. Shi et al. (2022) find that this incentive is particularly significant for carbon-intensive industry [4]. To reduce emission cost, companies often enhance production workflows and increase energy efficiency, thereby enhancing their carbon performance. Second, CET policy can effectively influence corporate economic benefit. Xu and Xu (2024) show that the proper use of carbon allowances can reduce compliance cost and improve economic efficiency [19]. Additionally, companies can sell surplus carbon allowances to generate extra revenue, further improving their carbon performance [18]. Moreover, CET policy stimulates companies to invest in green technology innovation. Liu et al. (2023) find that CET policy increases competitive pressure on companies [16], stimulating their investment in technological innovation and develop sustainability technologies to gain a competitive edge, thereby enhancing their carbon performance.

2.1.3. Literature Summary

In summary, although existing studies have provided valuable insights into the impacts of CET policies, several critical gaps remain. First, the current literature predominantly focuses on emission-reduction outcomes or innovation performance, while giving limited attention to corporate carbon performance measured in terms of carbon efficiency, which captures firms’ ability to generate economic output with lower carbon emissions. This imbalance limits our understanding of whether CET policies can promote efficiency-oriented low-carbon transformation rather than merely deliver emission cuts. Moreover, although scholars have acknowledged regional and temporal variation in CET effects, the spatiotemporal heterogeneity in its impact on carbon performance, particularly under differing levels of environmental governance intensity and policy duration—has not been systematically examined.

Second, the policy transmission mechanism remains only partially unpacked. Existing studies mainly discuss direct policy effects, but the micro-level pathways through which CET influences corporate carbon performance are still underexplored. Specifically, empirical evidence is lacking regarding whether financing constraints serve as a mediating channel, and whether CET policies can trigger a chained transmission mechanism—whereby the alleviation of financing constraints enhances R&D investment, which subsequently improves carbon performance.

Third, prior research pays limited attention to internal governance heterogeneity. While existing studies emphasize external institutional conditions, they largely overlook how firm-level governance characteristics influence policy effectiveness. In particular, the moderating role of executives’ green backgrounds—an emerging factor shaping strategic environmental decision-making—has not yet been investigated within the CET framework.

Addressing these gaps, the present study advances the literature in three ways. First, this study adopts a carbon performance perspective and complements existing CET research that predominantly focuses on emission reduction by emphasizing carbon efficiency as an outcome of policy implementation. Second, it identifies and empirically validates a complete “financing–innovation–carbon performance” chain mechanism, opening the black box of CET policy transmission at the micro level. Third, it incorporates executives’ green backgrounds into the analytical framework, revealing how internal governance features condition the effectiveness of market-based environmental regulation. Together, these contributions enrich the theoretical discourse on CET policies and offer a more comprehensive understanding of their micro-level effects.

2.2. Research Hypothesis

2.2.1. Direct Effect of CET Policy on Corporate Carbon Performance

Emissions trading was first formalized by Dales, who proposed that regulators could set an aggregate emissions cap and allocate tradable allowances to market participants, thereby achieving cost-effective abatement through trading. In China’s CET pilot programs, this market logic operates within a distinctive institutional setting characterized by administratively determined allowance allocation (with a large share initially allocated for free), mandatory monitoring–reporting–verification (MRV) and compliance obligations, and heterogeneous enforcement capacity across regions [38]. These design features mean that firms face not only an economic price signal but also a regulatory compliance constraint that is credibly enforced through the pilot institutions.

From a property-rights perspective, the Coase theorem suggests that once emission rights are defined and transaction arrangements are in place, trading can internalize the negative externality of carbon emissions and improve allocative efficiency [39]. In China’s pilots, allowances effectively become a quasi-asset tied to verified emissions and annual compliance. When a firm’s verified emissions exceed its allocated allowances, it must either purchase additional allowances or undertake operational and technological adjustments to reduce emissions and lower future compliance pressure [40]. Specifically, firms can respond by short-term production or energy-use adjustments that immediately curb emissions, or longer-term green innovation and process upgrading that improves carbon-use efficiency. Both responses can enhance corporate carbon performance as measured by carbon efficiency, because they reduce emissions per unit of economic output.

In addition, the trading mechanism creates a direct economic channel. Firms that cut emissions below their allocated quotas generate surplus allowances that can be sold in the market. Under the pilot rules, this translates emission reductions into tradable carbon assets and potential cash flow, improving firms’ economic returns while maintaining lower emissions [41]. Taken together, the compliance constraint and the monetization of surplus allowances link the China-specific CET pilot design to improvements in carbon efficiency through both abatement-driven efficiency gains and allowance-related economic benefits [31]. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1:

CET policy enhances corporate carbon performance by internalizing carbon externalities through enforceable MRV-based compliance constraints and tradable allowance incentives, which induce firms to reduce emissions and improve carbon performance.

2.2.2. The Mediating Role of Financing Constraints

Financing constraints refer to the limitations enterprises face when accessing external capital, influenced by factors such as information asymmetry between financiers and firms, and agency problems within organizations [42]. In China’s CET pilot context, the compliance regime requires firms to conduct MRV and to fulfill annual compliance obligations, which increases the credibility of firms’ environmental information disclosure and reduces information opacity in capital markets [43]. Drawing on signaling theory, corporate participation in CET demonstrates a firm’s environmental responsibility awareness and sustainable development potential to external stakeholders, thereby enhancing investor confidence and willingness to provide financial support, which alleviates financing constraints [24]. Additionally, China’s policy-driven expansion of green finance and banks’ “green credit” allocation practices strengthens this signal, enabling CET-regulated and low-carbon transitioning firms to obtain preferential access to financing resources and further easing financing constraints [44]. Moreover, carbon allowances obtained through CET can be utilized as carbon assets for pledge financing. Financial institutions provide loans based on the market value assessment of these allowances, creating an innovative financing channel that mitigates financing constraints [45].

Eased financing constraints improve corporate carbon performance, operationalized as carbon efficiency, by relaxing the resource bottleneck for efficiency-enhancing low-carbon transformation. First, firms can allocate capital to low-carbon and environmental projects, diversifying business portfolios and reducing operational carbon emissions. Second, enterprises can invest in professional carbon management teams and systems to monitor, analyze, and optimize carbon data, enabling precise and efficient development of emission reduction strategies [46]. Based on these mechanisms, the study hypothesize as follows:

H2:

CET policy improves corporate carbon performance by alleviating financing constraints; that is, CET participation reduces firms’ financing constraints, which in turn enhances corporate carbon performance.

2.2.3. The Mediating Role of R&D Investment

After the government implements CET policy, the emissions costs for companies are internalized. To reduce these costs, companies often need to implement actions to realize carbon reduction [6]. Following the Porter hypothesis, environmental regulations create pressure on companies, motivating them to innovate and improve [3]. In China’s CET pilot programs, such pressure is reinforced by the institutionalized MRV and compliance regime and by the expectation of progressively tighter allowance constraints, which together make emission reduction and cost control recurring managerial objectives rather than one-off responses [38]. When companies participate in CET, the pressures from emission reduction and cost savings stimulate them to boost R&D investment in developing more efficient and green technologies [36]. This innovation incentive is further strengthened because carbon prices and quota scarcity translate technological improvements into measurable compliance savings and potential allowance gains, providing an explicit economic return to low-carbon R&D within the pilot market [7]. The advancement and implementation of green technologies can significantly improve corporate carbon performance as measured by carbon efficiency [17].

Furthermore, under the CET policy, firms must continuously balance allowance compliance costs against internal abatement options, which prompts a re-optimization of resource allocation toward efficiency-enhancing innovation. To improve production efficiency and environmental capacity, companies may increase R&D investment, enabling them to develop and adopt cleaner production technologies and products [20], thereby enhancing corporate carbon performance and increasing their market competitiveness in green products. Additionally, CET policy provides new investment opportunities for companies, motivating them to allocate resources to low-carbon technology innovation with future profit potential [25]. Through continuous R&D investment, companies can increase their long-term returns, reduce future environmental risks, and ultimately improve corporate carbon performance via sustained improvements in carbon-use efficiency [47]. Drawing from the above analysis, this study hypothesize as follows:

H3:

CET policy improves corporate carbon performance by increasing corporate R&D investment; that is, CET participation stimulates firms’ R&D investment, which in turn enhances corporate carbon performance.

2.2.4. The Chain Mediation Impact of Financing Constraints and R&D Investment

Drawing on signaling theory, CET compliance in China’s pilot programs, supported by MRV and annual allowance surrender requirements, conveys more credible and verifiable environmental responsibility signals to external stakeholders, thereby reducing information asymmetry between firms and investors. This signaling effect enhances external trust and improves firms’ access to financing, which alleviates their financing constraints [24]. Lower financing constraints provide firms with increased capital availability, enabling them to make long-term and uncertain R&D investments. According to innovation theory, sufficient and stable capital supply is a prerequisite for technological innovation, particularly in capital-intensive industries where green R&D requires substantial input, long payback periods, and tolerance for risk [15,48].

When financing constraints are eased, firms are more capable of sustaining innovation continuity, avoiding the interruption of R&D activities and the loss of accumulated knowledge and technological capabilities [49]. Consequently, increased R&D investment enhances firms’ ability to develop and apply green technologies, improve energy efficiency, and optimize carbon management systems. This process ultimately strengthens corporate carbon performance by achieving substantive emission reduction and economic–environmental benefits [50]. Therefore, CET policy can influence carbon performance through a progressive mechanism in which policy signals alleviate financing constraints, which in turn stimulate R&D investment and eventually improve carbon efficiency. Based on the above reasoning, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H4:

Financing constraints and R&D investment mediate the impact of CET policy on corporate carbon performance in a chain mediation.

2.2.5. The Moderating Effect of Executive Green Background

The accumulation of environmental education, professional experience, and technical skills comprises the green background of executives, which not only aids in integrating environmental considerations into corporate decision-making but also propels sustainable corporate development [1]. According to signaling theory, upper echelons theory, and the resource-based view, the green background of the executive team is seen as a strategic asset for companies to address environmental regulations, significantly enhancing their capacity to respond to such regulations [9]. In China’s CET pilot context, where firms face MRV-based compliance, quota constraints, and evolving local enforcement as well as carbon price uncertainty, executives’ green background becomes particularly valuable for interpreting regulatory requirements and coordinating internal responses [51]. Under the framework of CET policy, this background enables executives to more effectively identify and exploit strategic opportunities in the carbon market, optimize resource allocation, and increase R&D investment, thereby transforming policy pressures into competitive advantages.

Firstly, executives with a green background can professionally translate the effectiveness of corporate participation in CET into market signals, for example, by strengthening emissions accounting and verification routines, formulating credible compliance and abatement roadmaps, and communicating measurable low-carbon progress, reducing information asymmetry, boosting investor confidence, and securing low-cost financing. Secondly, their professional judgment aids in the precise assessment of the feasibility and risks associated with carbon quota pledge financing, which is highly dependent on quota valuation, policy rules, and compliance risk under the pilot policy, promoting innovative applications of carbon financial instruments, expanding financing channels, and alleviating financing constraints. Additionally, given the high volatility of the carbon trading market, executives with a green background can accurately assess policy risks and proactively plan R&D directions, such as establishing green technology funds and building industry-academia-research collaborative networks, steering R&D resources towards low-carbon and green areas. The technological foresight and resource integration capabilities of such executives generate a synergistic effect, not only guiding the precise planning of low-carbon technology R&D directions but also facilitating the efficient transformation of R&D investment into corporate carbon performance. This creates a dynamic mechanism of “policy incentives-R&D breakthroughs-performance enhancement.” Based on the analysis, this study proposes the following hypotheses.

H5:

The executive green background positively moderates the mitigating effect of the CET policy on corporate financing constraints.

H6:

The executive green background weakens the negative impact of financing constraints on R&D investment.

H7:

The executive green background positively moderates the chained mediation effect through which the CET policy influences corporate carbon performance via financing constraints and R&D investment.

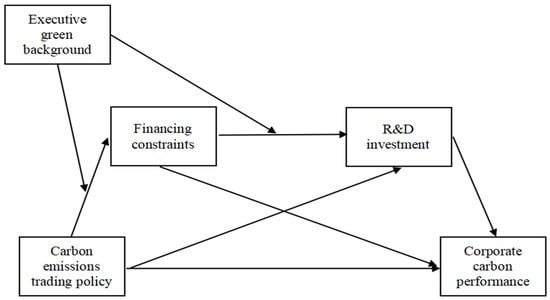

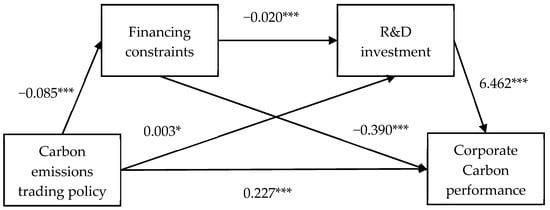

Therefore, this study constructs a moderated chained mediation model to explain the mechanism through which the CET policy affects corporate carbon performance. The conceptual model is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

3. Research Design

3.1. Sample Selection and Data Sources

Since the launch of China’s national CET market in 2021, initially focusing on the power generation industry, with the aim of avoid the effect of this policy, the study utilizes data from publicly traded companies in China for the period 2010–2020 as the initial sample. To guarantee the robustness of the empirical analysis, firms in the financial and insurance industries, those labeled with “ST” or “ST *” designations, and firms with incomplete key variable data were excluded. After filtering, a total of 4868 observation samples were acquired. It should be noted that the sample size is relatively limited because the analysis focuses exclusively on listed firms that participated in carbon emissions trading within pilot regions during the period 2010–2020, in line with the policy’s pilot-based and sector-specific implementation. To alleviate the influence of extreme observations, all continuous variables were winsorized at the 1% and 99% levels. Roster of firms engaged in CET was manually compiled based on information published by relevant departments in each pilot city. Additionally, the study also involves provincial-level carbon emissions data and financial data of listed companies, sourced from the WIND database and the China Energy Statistical Yearbook.

3.2. Variable Definitions and Measurements

3.2.1. Carbon Performance

Based on the study by Mai et al. (2024) [8] and considering data availability, this study measures corporate carbon performance as carbon efficiency, defined as the ratio of operating revenue to carbon emissions, where a higher value reflects superior carbon performance. Given that improvements in carbon outcomes typically lag behind the easing of financing constraints and increases in R&D investment, the one-period lagged carbon performance is used as the dependent variable.

A key measurement challenge is that firm-level verified emissions data are not consistently available for the full sample and period. Accordingly, firm-level emissions are estimated by combining provincial emission statistics with provincial main business cost data, allocating provincial emissions to firms based on their share of provincial main business costs. This proxy is theoretically robust and methodologically appropriate, as it captures the carbon efficiency of economic output, corresponds to the time-lagged nature of emission-reduction effects, and accords with widely adopted estimation practices in the absence of micro-level carbon disclosure. Specifically, provincial emissions are allocated to firms based on their share of provincial main business costs. We acknowledge that this proxy may introduce measurement error because it cannot fully capture intra-provincial and inter-industry heterogeneity in energy intensity and emission factors. Nevertheless, it provides a feasible and commonly used approximation of firm-level carbon exposure when micro-level emissions disclosure is unavailable, and it is well aligned with our focus on carbon performance as carbon efficiency. Importantly, any remaining measurement error is likely to be non-systematic with respect to CET treatment and therefore would tend to attenuate estimated effects rather than mechanically generate significant results. To further mitigate this concern, we incorporate province-by-industry fixed effects to absorb persistent heterogeneity in energy intensity and emission factors across province–industry cells, thereby reducing potential bias arising from the provincial emissions allocation procedure.

Furthermore, the measure is policy-relevant, reflecting the carbon-intensity reduction logic embedded in China’s “Dual-Carbon” strategy and the emission-efficiency goals specified in the 14th Five-Year Plan. It also possesses broad industry applicability, as it evaluates emission efficiency relative to output rather than relying on industry-specific production or technological conditions, thereby enabling meaningful comparison across sectors in large-sample analyses. Overall, this indicator ensures measurement validity, data continuity, and cross-firm comparability in empirical research on corporate carbon performance. Accordingly, this indicator supports empirical analysis by ensuring data continuity and cross-firm comparability, while the above robustness analyses help address potential bias arising from proxy-based emissions estimation. The calculation formula is presented below:

3.2.2. Policy Interaction Term

The primary independent variable is CET policy interaction term DID, composed of time × treat. Since the carbon market pilot regions were mainly opened from mid-2013 to early 2014, the study identifies 2014 as the year of policy implementation. Therefore, for years before 2014, time = 0; and for years after 2014, time = 1. If the company participates in CET, then treat = 1; otherwise, treat = 0. Although the CET pilot programs were launched at slightly different calendar dates across regions between 2013 and 2014, the empirical analysis is conducted using annual data, which limits the ability to distinguish within-year implementation differences. More importantly, while several pilot regions announced their schemes in 2013, the establishment of binding compliance obligations, including quota surrender and verified emissions accounting, became effectively operational for regulated firms around 2014. Accordingly, following existing practice, this study treats 2014 as the first common effective policy year across pilot regions. Any residual timing mismatch is unlikely to be systematically correlated with firm-level outcomes and therefore would tend to attenuate estimated effects rather than bias them upward.

3.2.3. Mediating Variables

- 1.

- Financing constraints

Based on the study by Hadlock and Pierce (2010) [52], this study employs the absolute value of the SA index to quantify firms’ financing constraints, where a larger value represents a higher level of financial constraint. The SA index is grounded in firm size and age, two fundamental determinants of external financing frictions, and is less likely to suffer from endogeneity arising from firms’ financial policies, making it one of the most widely adopted indicators in the literature. This feature is particularly important in a policy-evaluation setting such as ours, because the CET policy may simultaneously affect firms’ cash flows, leverage, dividend policy, and investment decisions. Indices such as the KZ and WW measures incorporate several accounting- and cash-flow-based components that are more directly influenced by these corporate decisions, which may generate mechanical comovement with the policy shock and complicate causal interpretation in mediation analysis. Although no single measure can fully capture all dimensions of corporate financing constraints, the SA index provides a relatively stable and policy-insensitive proxy that reflects long-term structural financing barriers, and is therefore suitable for the purposes of this study. We acknowledge that alternative proxies may capture additional dimensions of financing frictions; accordingly, our mechanism results should be interpreted as evidence consistent with the proposed financing-constraint channel rather than as a complete measurement of firms’ financing conditions.

- 2.

- R&D investment

Building on the approach of Cui and Qiao (2024) [53], R&D investment is quantified by the proportion of R&D expenditure relative to operating revenue. This indicator is appropriate because it reflects a firm’s continuous innovation input intensity while controlling for firm size, thereby ensuring comparability across firms and over time. Moreover, the ratio captures the extent to which firms allocate resources to technological upgrading and innovation activities, which is consistent with the theoretical logic that innovation capability depends not on absolute input volume but on sustained and proportional investment in R&D. Although green R&D would be a more direct measure of low-carbon innovation, firm-level green R&D expenditure is not consistently disclosed in China. Moreover, CET-induced innovation often operates through reallocating overall R&D resources toward low-carbon applications rather than increasing a separately reported green R&D category. Therefore, total R&D investment is adopted as a pragmatic and conservative proxy for firms’ innovation response to CET policy.

3.2.4. Moderating Variables

Based on the study by Cheng et al. (2025) [54], this study utilize the number of executives with a green background in the current year plus one, and then take the logarithm as the measure of the executive green background (LSBJit). This indicator is theoretically appropriate because executives with environmental or sustainability-related backgrounds are more likely to demonstrate stronger environmental governance awareness, specialized sustainability expertise, and practical experience in green management, which can shape firms’ strategic choices and resource allocation toward low-carbon development. In addition, the logarithmic transformation mitigates the influence of extreme values and improves cross-firm comparability, thereby enhancing the indicator’s empirical robustness and explanatory validity.

3.2.5. Control Variables

Based on the studies by Liu et al. (2023) [16], Mai et al. (2024) [8], and Jiang et al. (2024) [55], this study controls for company size (SIZEit), leverage (LEVit), profitability (ROAit), internal cash flow (CASHFLOWit), ownership concentration (TOP5SHAREit), market value (TOBINQit), ownership type (SOEit), marketization index (MARKET), time trend (Time Trend), industry fixed effect (Industry), and year fixed effect (Year). The detailed definitions of all control variables are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definition of control variables.

3.3. Model Building

3.3.1. Difference-in-Differences (DID) Model

To test H1, the study establishes a model as follows:

where the dependent variable CPit+1 represents the one-period lagged carbon performance of listed companies, and the primary independent variable is the CET policy interaction term DID. Controls are the control variables, including company size, leverage, profitability, etc. Time Trend is the time trend variable, Industry refers to industry fixed effect, and Time represents time fixed effect. If is significantly greater than 0, H1 is supported. To mitigate the confounding effects of contemporaneous environmental and industrial policies, we explicitly control for a set of time-varying regional and firm-level policy proxies, including the regional marketization index and industry—year fixed effects. These controls help absorb the influence of other policy interventions that evolve over time and across regions, thereby improving the identification of the CET policy effect.

3.3.2. Chain Mediation Model

Based on the chain mediation testing procedure [57,58], we construct Model (4) to test the influence of CET policy on corporate financing constraints. Based on Model (4), Models (5) and (6) are added to construct the chain mediation model as follows:

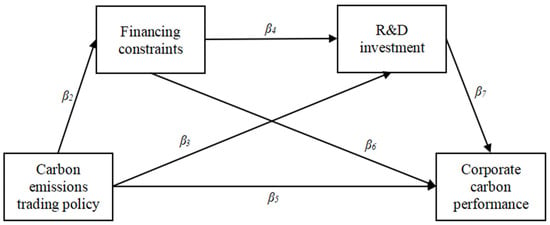

As shown in Figure 2, the chain mediation model above includes two independent mediation effect: “CET policy → Financing constraints → Corporate carbon performance” and “CET policy → R&D investment → Corporate carbon performance.” The independent mediation effect is represented by the product of coefficients from Models (4)–(6), and . It also includes one serial mediation effect: “CET policy → Financing constraints → R&D investment → Corporate carbon performance.” The chain mediation effect is represented by the product of coefficients from Models (4), (5), and (6), . The total mediation effect encompasses the combined impact of both the independent and serial mediation effects: ().

Figure 2.

Mechanism path diagram of the chain mediating model.

3.3.3. Moderated Mediation Model

To test the moderating effect of executive green background in the chain mediation effect, the following model was constructed:

when is significant, Hypothesis H5 is verified. When is significant, Hypothesis H6 is verified. This study draws on the “mediation effect difference method” proposed by Edwards and Lambert (2007) [59], which has higher test power, and uses the Bootstrap method to resample 5000 times to verify Hypothesis H7.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis and VIF Test

4.1.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

As shown in Table 2, the maximum, minimum, standard deviation, and mean values for CPit+1 during the sample period are 8.101, 0.185, 0.962, and 1.536, respectively, indicating significant variation in corporate carbon performance among companies, with generally low levels. The mean, maximum, and minimum values for R&Dit are 0.033, 0.212, and 0.0002, respectively, indicating considerable differences in R&D investment among companies, with an overall low level. Overall, the results imply that the variables selected for the study exhibit a sound statistical distribution.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of variables.

4.1.2. VIF Test

To assess the potential multicollinearity problem among explanatory variables, this study conducts a VIF test. As shown in Appendix A (Table A1), all VIF values fall within the range of 1.13–3.00, which is far below the commonly accepted threshold of 10 and even below the stricter criterion of 5. These results suggest that multicollinearity is not a serious concern in the regression model, and the estimated coefficients are statistically reliable.

4.2. Main Results

4.2.1. Baseline Regression Analysis

Table 3 presents the analysis results of Model (3). In column (1), control variables, as well as fixed effect, are not considered; in column (2), control variables are added to the model from column (1); and in column (3), both industry and time fixed effect are further included. Whether or not control variables and fixed effect are included, DID and CPit+1 are markedly positive at the 1% significance level. As shown in the column (3), the DID coefficient is 0.290, indicating that the carbon performance of companies participating in CET is, on average, 29.0% higher than that of companies not participating in carbon trading. The results suggest that participation in carbon trading significantly improves corporate carbon performance, thus confirming H1.

Table 3.

Main effect regression analysis results.

Moreover, this finding is consistent with prior studies arguing that market-based environmental regulations can incentivize emission reduction and improve firms’ environmental performance [12,55]. Similarly to the evidence from the EU ETS reported by Dechezleprêtre et al. (2023) [14], these results confirm that emissions trading enhances firms’ carbon efficiency by internalizing carbon costs and encouraging low-carbon practices. Meanwhile, the results also align with the Porter Hypothesis [3], which posits that appropriate environmental regulation can stimulate firms’ innovation and ultimately lead to better environmental outcomes. Therefore, the empirical findings not only validate the effectiveness of China’s CET policy at the micro-firm level but also reinforce the conclusions of existing literature in both international and domestic contexts.

4.2.2. Robustness Check

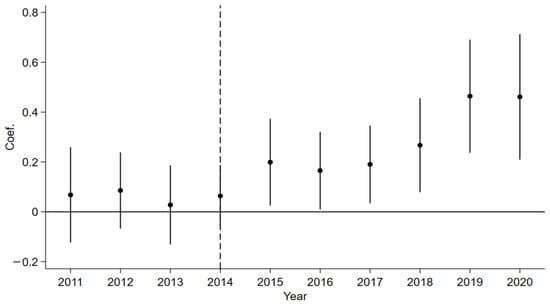

- Parallel trend testThe study employs the initial year of the sample period (2010) as the base year to conduct a parallel trend test. Table 4 and Figure 3 indicate that prior to CET policy’s introduction, all confidence interval includes 0, indicating no substantial disparities between the treatment and control groups. Following CET policy’s introduction, the interaction terms are significant (with confidence interval is above 0). These results confirm the validity of the parallel trend assumption.

Table 4. Parallel trend test.

Table 4. Parallel trend test. Figure 3. Parallel trend test for treatment and control groups.

Figure 3. Parallel trend test for treatment and control groups.

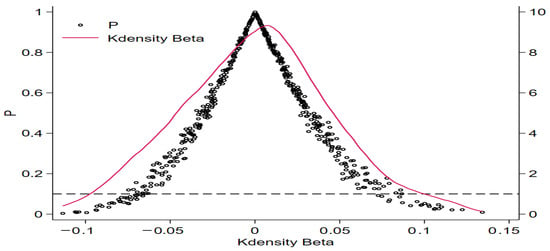

- 2.

- Placebo testIn this study, a placebo test is designed based on the approach of constructing virtual treatment groups. In the placebo test, 500 random policy shocks are constructed, with 100 companies randomly selected as pilot companies for each shock. The p-values of the 500 regressions are then calculated, and the p-values along with the estimated coefficients are plotted in a kernel density graph (Figure 4). In Figure 4, the estimated coefficients are concentrated around 0, with most estimates not meeting the 10% significance criterion, and the regression coefficients are all to the left of the baseline model’s regression coefficient (0.290), suggesting that the placebo test validates the reliability of the results.

Figure 4. Placebo test.

Figure 4. Placebo test.

- 3.

- Other robustness checksThe outcomes of additional robustness tests are shown as Table 5. Control represent the regression results of the omitted control variables. These checks include: to exclude potential bias from sample characteristics, the current carbon performance CPit is utilized as the dependent variable, with the results are displayed in column (1); to eliminate the effect of regional factors and individual characteristics on the dependent variable, individual fixed effect () replace industry fixed effect. The result of this check is shown in columns (2); accounting for the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, observations for 2020 were excluded and the model was recalculated, with the results shown in column (3); to reduce sample selection bias, the propensity score matching (PSM) method is used for 1:1 nearest neighbor matching, and a new control group is set, with the results shown in column (4). To eliminate the confounding influence of persistent heterogeneity at the province–industry level on the dependent variable, province-by-industry fixed effects (Province × Industry) are included. The result of this robustness check is reported in column (5). After conducting these checks, the core findings of this study remain unchanged.

Table 5. Main effect robustness checks.

Table 5. Main effect robustness checks.

4.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.3.1. Heterogeneity in Regional Environmental Governance Intensity

Based on the Porter hypothesis, reasonable environmental regulations can stimulate corporate innovation, resulting in “innovation compensation” that offsets compliance cost and even generates net gains [3]. However, CET-induced responses are not unidirectional. Competing compliance-cost arguments imply that when regulatory pressure becomes excessively stringent or enforcement is highly punitive, firms may prioritize short-term compliance over long-term upgrading, reallocating scarce cash flow toward allowance purchases, end-of-pipe treatment, or administrative compliance activities rather than productivity-enhancing green innovation. In addition, regional institutional capacity constraints shape how CET incentives translate into firm behavior. In regions with moderate environmental governance intensity, enforcement is typically sufficiently credible to discipline high emitters while leaving firms room to adjust through managerial upgrading and technology investment, making the innovation-compensation pathway more likely to dominate. By contrast, when regional governance intensity is very high, especially under strong inspection campaigns and rigid compliance requirements, firms may face heightened liquidity pressure and regulatory uncertainty, which can amplify the crowding-out of environmental and R&D investment and weaken improvements in carbon performance [22]. Conversely, in regions with very weak governance capacity, limited monitoring infrastructure and enforcement credibility may reduce the effective carbon price signal, potentially dampening firms’ incentives to transform substantively beyond symbolic compliance.

To examine the heterogeneous role of regional governance conditions in shaping CET effectiveness, this study follows Xie et al. (2017) [60] and uses the industrial pollution regulation completion amount relative to industrial added value for each province as a proxy for regional environmental governance intensity. Specifically, regional environmental governance intensity (ERIit) is calculated as industrial pollution control investment divided by industrial added value. This proxy captures the input-based intensity of local environmental governance effort and implementation capacity relative to the scale of industrial activity, rather than a pure measure of regulatory stringency. We acknowledge that (ERIit) may be correlated with regional industrial structure and economic development level; therefore, we control for the level of regional market-oriented economic development in our baseline specifications, and interpret (ERIit) as a composite indicator of governance effort devoted to pollution control per unit of industrial output. The sample is categorized into low and high regional environmental governance intensity groups based on the average value of regional environmental governance intensity.

As illustrated in Table 6, in the low group, DID’s coefficient is 0.227 and reaches significance at the 1% level, suggesting that when regional environmental governance intensity is low, CET policy significantly improves corporate carbon performance. In the high regional environmental governance intensity group, DID’s coefficient is 0.213 and reaches significance at the 1% level. Furthermore, the Fisher coefficient difference test yields a p-value of 0.036, which passes the 5% significance level, confirming that the impact of CET policy on corporate carbon performance differs significantly between the two groups. Therefore, the promotional effect of CET policy is more pronounced in regions with lower environmental governance intensity.

Table 6.

Heterogeneity analysis results.

4.3.2. Heterogeneity in Policy Duration

Considering that companies need time to respond to the CET policy, the beneficial influence of this policy on corporate carbon performance requires time to accumulate. CET policy variable DID is split into a short-term group (SDID) and a long-term group (LDID) to test the heterogeneity of CET policy’s impact over time. For companies participating in CET, SDID is assigned a value of 1 for the first and second years of market participation, and 0 otherwise; from the third year onwards, LDID is assigned a value of 1, and 0 otherwise.

The results are shown as Table 6. SDID’s coefficient is 0.165, which meets the 1% significance criterion. LDID’s coefficient is 0.339 and meets the 1% significance criterion. These results suggest that CET policy substantially enhances corporate carbon performance regardless of the time span, with a stronger effect in the long term.

5. Mechanism Analysis

5.1. Chain Mediation Effect Analysis

This study employed bootstrap analysis (5000 resamples) with Stata18.0 to test mediating and chain mediating effects. As shown in Figure 5. The direct effect of CET policy on corporate carbon performance was positive and significant (β5 = 0.227, p < 0.001), revalidating Hypothesis H1. The direct effect of CET policy on financing constraints was negative and significant (β2 = −0.085, p < 0.001), indicating this policy significantly alleviates financing constraints for participating firms. The direct effect of CET policy on R&D investment was positive and significant (β3 = 0.003, p < 0.01), demonstrating the policy significantly enhances corporate R&D investment. Thus, each direct effect path in the chain mediation model was significant.

Figure 5.

Direct path diagram. * and *** represent significance levels of 10% and 1%, respectively.

According to Table 7’s results, three indirect effect paths existed in the chain mediation.

Table 7.

Bootstrap analysis of chain mediation results.

First, the indirect effect of CET policy → Financing constraints → Corporate carbon performance was 0.033 (95% CI [0.021, 0.045]), excluding zero, confirming significant mediation and validating Hypothesis H2. The underlying reason is that CET participation sends a positive environmental signal and enhances firms’ access to external financing, which alleviates capital shortages and enables higher spending on low-carbon initiatives, thereby improving carbon performance. This channel implies that the carbon market functions not only as a compliance mechanism but also as a credibility device: firms that engage in CET and demonstrate stronger carbon governance tend to face lower perceived risk by lenders and investors, resulting in improved credit availability and financing terms. As a result, firms are better able to fund carbon management upgrades—such as MRV systems, energy-saving retrofits, and cleaner equipment replacement—that directly improve carbon efficiency.

Second, the indirect effect of CET policy → R&D investment → Corporate carbon performance was 0.019 (95% CI [0.002, 0.040]), excluding zero, indicating significant mediation and supporting Hypothesis H3. This occurs because CET imposes emission-reduction pressure consistent with the Porter Hypothesis, thereby incentivizing firms to increase innovation input. Higher R&D investment accelerates the development and application of green technologies, which enhance energy efficiency and reduce emissions at the source, ultimately improving firms’ carbon performance. Beyond technological upgrading, this mechanism also suggests a strategic reallocation effect: firms respond to carbon pricing by shifting R&D portfolios toward process innovation, low-carbon product design, and digital energy-management solutions. Over time, these innovations can generate both compliance benefits (lower allowance demand and reduced penalty risk) and market benefits (improved product competitiveness in green-sensitive markets), jointly reinforcing carbon performance improvements.

Third, the indirect effect of CET policy → Financing constraints → R&D investment → Corporate carbon performance was 0.012 (95% CI [0.007, 0.016]), excluding zero, validating the chain mediation effect and Hypothesis H4. This finding reveals a clear transmission mechanism: CET policy eases financing constraints, thereby enhancing firms’ willingness and capacity to undertake innovation investment, which ultimately improves carbon performance. Its economic implication lies in the fact that improved capital availability reinforces the innovation-driven emission-reduction pathway, forming a “financing → innovation → performance” chain that amplifies the long-term carbon mitigation benefits of CET. Notably, the presence of this sequential pathway indicates that the innovation response to CET is financially conditioned: when external capital becomes more accessible, firms can sustain longer-horizon and higher-risk green R&D projects rather than relying on short-term, incremental adjustments. This also helps explain why CET effects may strengthen over time—initial financial relief supports cumulative innovation, which then translates into measurable efficiency gains with a lag.

Overall, these findings confirm that CET policy enhances corporate carbon performance through both single mediation channels (financing constraints and R&D investment) and a sequential chain mediation pathway. This highlights that the effectiveness of CET policy depends not only on direct emission constraints but also on its ability to reshape firms’ financial conditions and innovation incentives.

5.2. Moderating Effect Analysis

Table 8 presents the results for Models (7) and (8). The result of Model (7) shows that the interaction term between executive green background and the CET policy is significantly negative at the 1% level (λ3 = −0.090, p < 0.001), indicating that the executive green background significantly strengthens the CET policy’s effect on alleviating corporate financing constraints, thus confirming hypothesis H5. Further analysis of Model (8) reveals that the interaction term between executive green background and financing constraints is significantly positive at the 1% confidence level (λ6 = 0.006, p < 0.001), suggesting that an enhanced executive green background significantly weakens the negative impact of financing constraints on R&D investment, thereby confirming hypothesis H6.

Table 8.

Moderating effect analysis results.

These results are consistent with the theoretical arguments developed above. In China’s CET pilot setting, where compliance relies on MRV routines, quota constraints, and evolving local enforcement under carbon price uncertainty, executives with a stronger green background are better able to interpret regulatory requirements and coordinate internal responses. This capability allows them to translate CET participation into more credible market signals by strengthening emissions accounting and verification practices, formulating clear compliance and abatement roadmaps, and communicating measurable low-carbon progress, thereby reducing information asymmetry and enhancing external stakeholders’ confidence. As a result, CET participation is more likely to improve firms’ access to external financing and lower perceived transition risk, which amplifies the policy’s role in easing financing constraints (H5). Moreover, green-background executives possess stronger technological foresight and resource-integration capabilities, making them more inclined and more able to protect strategic R&D budgets when liquidity becomes tight. By improving internal carbon governance and prioritizing long-term low-carbon innovation, they mitigate the crowding-out effect of financing constraints on R&D investment, helping firms sustain green innovation efforts even under financial frictions (H6).

To ensure that these interaction results are not driven by the count-based operationalization of executive green background, we further re-measure the moderator as the proportion of green-background executives within the top management team (LSBJPit) and re-estimate Models (7) and (8). The results are consistent with those reported in columns (3) and (4), with the interaction terms remaining statistically significant and retaining the same signs. In addition, to alleviate concerns about omitted-variable bias arising from potential interactions between executive green background and other firm characteristics, we further include interaction terms between LSBJit and SIZEit (LSBJit × SIZEit) as well as between LSBJit and SOEit (LSBJit × SIZEit) status as additional controls. The results are consistent with those reported in columns (5) and (6). The key moderating effects remain robust, with the core interaction terms continuing to be statistically significant and exhibiting the same directions.

This study adopts the “mediation effect difference method” proposed by Edwards and Lambert (2007) [59], which offers a more powerful test of mediated effects. Utilizing the Bootstrap method, the study performs 5000 resamples to validate the moderated mediation effect. The procedure involves taking values of the moderating variable one standard deviation above and below its mean, denoted as M + SD and M − SD, respectively. If the test results between these standard deviations show significant differences, it indicates that the mediation effect varies significantly with the values of the moderating variable, confirming the presence of a moderated mediation effect. The results, as shown in Table 9, reveal that when the executive green background is at a high level (M + SD), the indirect effect of the policy through “financing constraints → R&D investment → corporate carbon performance” is 0.028 (95% CI = [0.004, 0.052]), not containing zero. In contrast, at a low level (M − SD), the indirect effect is −0.007 (95% CI = [−0.019, 0.004]), which includes zero, suggesting that executive teams with a weaker green background struggle to convert policy pressure into effective incentives for improving carbon performance. Further tests of differences between groups show that the difference in indirect effects between high and low levels is 0.035 (95% CI = [0.006, 0.068]), not containing zero. This result implies that the executive green background significantly positively moderates the chained mediating pathway between financing constraints and R&D investment, supporting hypothesis H7.

Table 9.

Bootstrap Moderating effect analysis results.

These findings are consistent with the theoretical logic that executive green background enhances firms’ ability to translate CET-induced pressure into an internally coordinated “finance–innovation” response. When green-background executives are more prevalent, firms tend to establish more professional MRV routines and carbon governance systems, which improves the credibility of environmental commitment and reduces perceived transition and compliance risks among external financiers. This strengthens the policy’s capacity to ease financing constraints and, crucially, allows firms to channel newly available funds into longer-horizon, higher-risk green R&D projects. Moreover, green-background executives typically have stronger technological foresight and resource integration capability, enabling them to prioritize low-carbon innovation in capital budgeting and to protect R&D expenditures from being crowded out by short-term liquidity pressures. As a result, the sequential pathway becomes effective only when managerial human capital is sufficiently aligned with low-carbon strategy, explaining why the indirect effect is significant at high green-background levels but not at low levels.

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1. Conclusions

The study explores the connection between CET policy and corporate carbon performance, along with the underlying mechanisms, utilizing data from Chinese publicly traded firms (2010–2020). The main conclusions are listed below: (1) CET policy significantly improves the carbon performance of participating companies. (2) The impact is heterogeneous. The positive effect of the CET policy on corporate carbon performance is observed in regions with lower environmental governance intensity, and this effect becomes more pronounced over time. (3) Financing constraints and R&D investment contribute to the chain mediation effect, where the CET policy alleviates financing constraints, increases R&D investment, and ultimately improves corporate carbon performance. (4) The executive green background enhances the CET policy’s effectiveness in alleviating financing constraints and reducing financing constraints’ negative impact on R&D investment, positively moderating the chain-mediated effects.

6.2. Implications

Based on the empirical results, this study proposes implications at both governmental and corporate levels. To enhance the practical relevance of these recommendations, the discussion further considers implementation feasibility, potential challenges, and corresponding safeguard measures.

From the government perspective, first, a regionally differentiated CET implementation strategy should be advanced, with priority support for areas where environmental governance capacity remains weak. A feasible pathway is to adopt a tiered regulatory framework that matches regulatory requirements to local MRV capacity. For example, regions with weaker capacity can start with standardized reporting templates, minimum MRV thresholds, and centralized third-party verification, while regions with stronger capacity can move toward stricter quota tightening and more frequent compliance audits. To reduce implementation gaps, the central government can establish a unified national carbon data platform that connects enterprise emissions reporting, allowance allocation, trading records, and compliance outcomes. In implementation, two practical obstacles should be anticipated. One is regional protectionism, where local governments may weaken enforcement to protect local industries; this can be mitigated by cross-regional inspections, transparent disclosure of compliance performance, and performance-based fiscal transfers linked to verified compliance quality. The other is data silos across environmental, industry, and financial regulators; this can be addressed by defining data standards, interfaces, and accountability rules for data sharing. From a cost–benefit perspective, these measures entail upfront costs in digital infrastructure and verification capacity, but they can yield benefits by lowering compliance uncertainty, reducing opportunistic behavior, and improving the credibility and efficiency of the carbon market.

Second, strengthening green finance can help alleviate firms’ financing constraints and improve the policy transmission from CET to innovation and carbon efficiency. A practical implementation route is to promote carbon-performance-linked credit and carbon-asset–based financing through standardized rules. Specifically, regulators can require unified carbon accounting and disclosure that is consistent with the CET MRV system, develop valuation guidelines for allowances and verified emission reductions, and build a risk identification toolkit for financial institutions, including stress tests under carbon price volatility and compliance risk. Potential obstacles include the difficulty of carbon asset valuation, banks’ conservative risk preferences, and limited availability of high-quality emissions data. To overcome these barriers, policymakers can introduce risk-sharing arrangements such as partial guarantees, interest subsidies for qualified low-carbon projects, and pilot insurance products for carbon price risk. In cost–benefit terms, such instruments may increase short-term fiscal burden and administrative complexity, but they can crowd in private capital, reduce the cost of green innovation, and improve the efficiency of resource allocation.

Third, enhancing firms’ environmental management capacity is essential for sustained CET effectiveness. A concrete pathway is to establish a national competency framework for carbon management, including standardized training modules (MRV, carbon strategy, low-carbon investment evaluation, and compliance risk management) and an optional professional certification for carbon management personnel. To address likely constraints such as talent shortages and uneven managerial quality, policymakers can combine public training programs, incentives for firms to appoint qualified carbon managers, and support for digital tools that lower MRV and reporting costs. The expected trade-off is that training and certification systems require administrative resources, but they improve policy implementation quality by reducing reporting errors, enhancing internal governance, and strengthening firms’ ability to translate regulatory pressure into efficiency improvements.

From the corporate perspective, firms should translate compliance pressure into innovation incentives by adopting a staged low-carbon innovation roadmap. In the short run, firms can prioritize projects with clearer paybacks (energy efficiency upgrades, process optimization, and digital monitoring). In the medium to long run, they can expand to higher-impact innovations (clean technologies and product redesign), supported by collaboration with research institutions and technology suppliers. Firms should also proactively use green finance, but should recognize obstacles such as high upfront costs and uncertain returns. To manage these risks, firms can apply portfolio-based R&D budgeting, milestone-based evaluation, and joint development agreements that share costs and risks with partners. The cost–benefit logic is that while early-stage investment increases near-term expenditure, it reduces future compliance costs and carbon price exposure and improves carbon efficiency.

In addition, firms should refine internal governance by strengthening carbon accountability and decision rights. Practical measures include appointing executives with environmental expertise to lead cross-departmental carbon governance, linking performance evaluation and compensation to carbon efficiency targets and verified compliance outcomes, and building integrated carbon accounting and early-warning systems that connect operational data with compliance requirements. Implementation obstacles may include internal data fragmentation and resistance to organizational change; firms can mitigate these by clarifying data ownership, setting internal audit routines, and embedding carbon metrics into core operational KPI. These measures increase management and IT costs but can reduce compliance risks, improve operational efficiency, and enhance long-term competitiveness under tightening environmental regulation.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

- First, this study is constrained by data availability and research context. The empirical analysis is based on Chinese A-share listed firms, and firm-level carbon emissions are proxied using provincial emission statistics. Although this approach improves sample coverage and comparability, it may introduce measurement error because it cannot fully capture within-province and within-industry heterogeneity in energy intensity and emission factors. This limitation may bias the results in two ways. If the proxy error is largely non-systematic, it is likely to attenuate the estimated policy effect toward zero, implying that our baseline estimates may be conservative. However, if the accuracy of the proxy varies systematically across regions or industries, it may blur heterogeneity patterns and potentially distort subgroup comparisons. In addition, listed firms are typically larger and subject to stronger disclosure and governance requirements, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to unlisted firms or to institutional settings with different market and regulatory conditions. Future research could employ verified firm-level emissions disclosure or facility-level emissions records, validate alternative emissions proxies, and extend the analysis to broader firm populations, multinational samples, or cross-country settings to enhance external validity.

- Second, the study focuses primarily on financing constraints and R&D investment as mediating mechanisms, which limits the completeness of the policy transmission explanation. While the findings support a “financing–innovation–carbon performance” pathway, CET may also influence corporate outcomes through other channels, such as managerial attention and green governance upgrades, operational restructuring and process optimization, dynamic capabilities, supply-chain coordination, and ESG-related practices. Omitting these mechanisms may lead to biased estimates of the mediated effects if unmodeled channels are correlated with financing constraints or R&D investment, and it also means that the evidence should not be interpreted as implying these two mediators are the only relevant pathways. Future research may adopt multi-mediator designs, sequential identification strategies, or mixed-method approaches (e.g., case studies and interviews) to disentangle concurrent channels—including green investment (e.g., capital expenditures on energy-efficient equipment, cleaner production lines, and carbon management infrastructure)—and provide a more comprehensive account of how market-based regulation translates into substantive corporate low-carbon transformation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.F. Data Curation, J.F. Methodology, J.F. Software, J.F. Investigation, J.F. Formal Analysis, J.F. Writing—Original Draft, J.F. Supervision, W.H. Writing—Review & Editing, W.H. Supervision, L.L. Writing—Review & Editing, L.L. Supervision, J.D. Writing—Review & Editing, J.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank all individuals who participated in this study for their valuable time and contributions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

VIF Test.

Table A1.

VIF Test.

| Variables | VIF | 1/VIF |

|---|---|---|

| DID | 1.130 | 0.886 |

| SAit | 1.960 | 0.511 |

| R&Dit | 1.910 | 0.523 |

| LEBJit | 1.180 | 0.847 |

| SIZEit | 3.000 | 0.333 |

| LEVit | 2.550 | 0.393 |

| ROAit | 2.160 | 0.463 |

| CASHFLOWit | 1.510 | 0.664 |

| TOP5SHAREit | 1.640 | 0.610 |

| TOBINQit | 2.080 | 0.482 |

| SOEit | 1.440 | 0.693 |

| MARKET | 1.420 | 0.705 |

References

- Wang, Q.; Huang, H.; Liu, T. Job destruction or job creation?: Evidence from carbon emission trading policies. Econ. Anal. Policy 2024, 84, 1010–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.-g.; Jiang, G.-w.; Nie, D.; Chen, H. How to improve the market efficiency of carbon trading: A perspective of China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 59, 1229–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; van der Linde, C. Toward a New Conception of the Environment-Competitiveness Relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, B.; Li, N.; Gao, Q.; Li, G. Market incentives, carbon quota allocation and carbon emission reduction: Evidence from China’s carbon trading pilot policy. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 319, 115650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, L.; Sun, J.; Shen, M. Carbon emissions abatement with duopoly generators and eco-conscious consumers: Carbon tax vs carbon allowance. Econ. Anal. Policy 2023, 80, 786–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, B.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, X. Assessment of the co-benefits of China’s carbon trading policy on carbon emissions reduction and air pollution control in multiple sectors. Econ. Anal. Policy 2024, 81, 1322–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Liu, P.; Shi, X.; Ai, X. China’s emissions trading scheme, firms’ R&D investment and emissions reduction. Econ. Anal. Policy 2023, 80, 1021–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, Y.; Yu, K.; Zhang, X. Enhancing corporate carbon performance through green innovation and digital transformation: Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 96, 103630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Liu, Z.; Cao, P.; Zhang, H. Environmental subsidies and green innovation: The role of environmental regulation and chief executive officer green background. Clean. Technol. Environ. Policy 2025, 27, 389–402. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, L.; Tang, Q. Does voluntary carbon disclosure reflect underlying carbon performance? J. Contemp. Account. Econ. 2014, 10, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, A.E.; Albitar, K.; Elmarzouky, M. A novel measure of corporate carbon emission disclosure, the effect of capital expenditures and corporate governance. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 290, 112581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Zhang, C.; Song, H.; Wang, Q. How does emission trading reduce China’s carbon intensity? An exploration using a decomposition and difference-in-differences approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 676, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Zhu, X.; Gao, X.; Yang, X. The influence of carbon emission trading on the optimization of regional energy structure. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechezleprêtre, A.; Nachtigall, D.; Venmans, F. The joint impact of the European Union emissions trading system on carbon emissions and economic performance. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2023, 118, 102758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xi, B. The effect of carbon emission trading on enterprises’ sustainable development performance: A quasi-natural experiment based on carbon emission trading pilot in China. Energy Policy 2024, 185, 113960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, L.; Sun, H.; Chen, B.; Wang, L. Optimization of carbon performance evaluation and its application to strategy decision for investment of green technology innovation. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 325, 116593. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Shi, X.; Zheng, L.; Fan, S.; Zuo, S. Green innovation and carbon emission performance: The role of digital economy. Energy Policy 2024, 195, 114344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]