A Time-Dependent Dijkstra’s Algorithm for the Shortest Path Considering Periodic Queuing Delays at Signalized Intersections

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Model Formulation

3.1. Network Topology Model

3.2. Extended Network Weight Matrix

3.2.1. Basic Parameter Weight Matrices

3.2.2. Periodic Queuing Delay-Related Parameter Weight Matrices

3.3. Signalized Intersection Periodic Queuing Delay Calculation Model

3.3.1. Calculation Method Overview

3.3.2. Calculation of Periodic Queuing Delay at Signalized Intersections

3.4. Total Path Weight Calculation

4. Time-Dependent Dijkstra’s Algorithm

4.1. Algorithm Concept Overview

4.2. Algorithm Procedure

| Algorithm 1: An time-dependent Dijkstra’s algorithm accounting for periodic queueing delays at signalized intersections |

|

4.3. FIFO Property and Algorithm Correctness

4.4. Algorithm Computational Performance

5. Numerical Experiments and Analysis

5.1. Traffic Network Description

5.2. Comparison of the Proposed Algorithm with Other Algorithms

5.2.1. Shortest Path at Different Departure Times

5.2.2. Shortest Path at Different OD Pairs

5.3. Simulation Validation and Analysis

5.3.1. Simulation Environment Construction

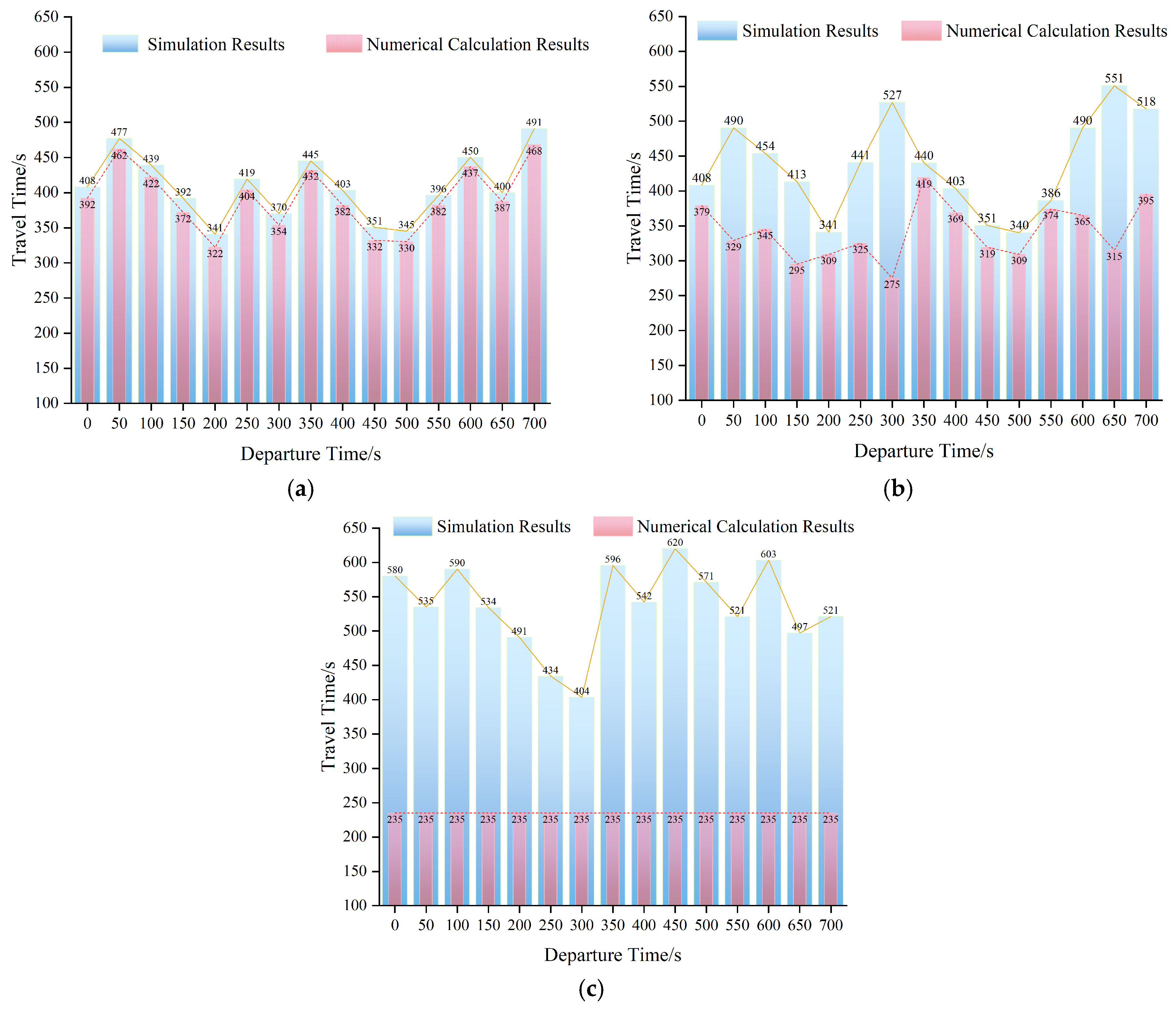

5.3.2. Analysis of Different Departure Times

5.3.3. Analysis of Simulation Results for Different OD Pairs

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Miller-Hooks, E.D.; Mahmassani, H.S. Least expected time paths in stochastic, time-varying transportation networks. Transp. Sci. 2000, 34, 198–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Sun, D.; Rilett, L.R. Heuristic shortest path algorithms for transportation applications: State of the art. Comput. Oper. Res. 2006, 33, 3324–3343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nannicini, G.; Baptiste, P.; Barbier, G.; Krob, D.; Liberti, L. Fast paths in large-scale dynamic road networks. Comput. Optim. Appl. 2010, 45, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artigues, C.; Huguet, M.; Guèye, F.; Schettini, F.; Dezou, L. State-based accelerations and bidirectional search for bi-objective multi-modal shortest paths. Transp. Res. Part C 2013, 27, 233–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallottino, S. Shortest-path methods: Complexity, interrelations and new propositions. Networks 1984, 14, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deo, N.; Pang, C.Y. Shortest-path algorithms: Taxonomy and annotation. Networks 1984, 14, 275–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Zhang, F.; Lei, L. Dynamic path planning based on service level of road network. Electronics 2022, 11, 3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari, E.; Rahmani, A.M.; SaberiKamarposhti, M.; Sahafi, A. An optimal path-finding algorithm in smart cities by considering traffic congestion and air pollution. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 55126–55135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Tian, S.; Zhang, N.; Liu, G.; Wu, Z.; Li, W. Optimization strategy for electric vehicle routing under traffic impedance guidance. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Chen, X.; Liao, R.; Yu, L. Development and evaluation of a vehicle platoon guidance strategy at signalized intersections considering fuel savings. Transp. Res. Part D 2019, 77, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.Q.; Zhang, K.; Li, M.; Chen, X.D.; Lin, X.; Li, S. Integrated optimization of traffic signal timings and vehicle trajectories considering mandatory lane-changing at isolated intersections. Transp. Res. Part C 2024, 160, 104013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.Y.; Miller-Hooks, E. Adaptive routing considering delays due to signal operations. Transp. Res. Part B 2004, 38, 385–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Shao, H.; Wu, T.; Fainman, E.Z.; Lam, W.H.K. Finding the reliable shortest path with correlated link travel times in signalized traffic networks under uncertainty. Transp. Res. Part E 2020, 144, 102159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakici, Z.; Aksoy, G. Does the minimization of the average vehicle delay and the minimization of the average number of stops mean the same at the signalized intersections? Int. J. Transp. Sci. Technol. 2024, 13, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Shao, H.; Wang, F.; Feng, Y.; Shen, L. A reliable energy consumption path finding algorithm for electric vehicles considering the correlated link travel speeds and waiting times at signalized intersections. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2022, 32, 100877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, L.; Tian, Z.; Zhao, N.; Roberts, C. A Novel Multi-Agent-Based Approach for Train Rescheduling in Large-Scale Railway Networks. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, R.; Jafari, M.; Kharbeche, M. Data-driven optimization for dynamic shortest path problem considering traffic safety. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 18237–18252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, E.W. A note on two problems in connexion with graphs. Numer. Math. 1959, 1, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, R.W. Algorithm 97: Shortest path. Commun. ACM 1962, 5, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, P.E.; Nilsson, N.J.; Raphael, B. Correction to: A formal basis for the heuristic determination of minimum cost paths. SIGART Bull. 1972, 37, 28–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.H.; Liu, Y.Q.; Huang, Q.L.; Zhang, Y.X.; Luan, G.F. An improved Dijkstra’s shortest path algorithm for sparse network. Appl. Math. Comput. 2007, 185, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enayattabar, M.; Ebrahimnejad, A.; Motameni, H. Dijkstra algorithm for shortest path problem under interval-valued Pythagorean fuzzy environment. Complex Intell. Syst. 2019, 5, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Zhang, X.; Hu, Y.; Liu, R.; Wang, Q.; He, H. Research on mobile agent path planning based on deep reinforcement learning. Systems 2025, 13, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.S.; Lin, J.F.; Yao, J.X.; He, D.W.; Zheng, J.S.; Huang, J.; Shi, P. Path planning for smart car based on Dijkstra algorithm and dynamic window approach. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2021, 2021, 8881684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziliaskopoulos, A.; Kotzinos, D.; Mahmassani, H.S. Design and implementation of parallel time-dependent least time path algorithms for Intelligent Transportation Systems applications. Transp. Res. Part C 1997, 5, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.L.; Hu, J.L.; Song, Y.F.; Li, Y.K.; Du, J. A new exact algorithm for the shortest path problem: An optimized shortest distance matrix. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 158, 107407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, X.; Shao, H.; Song, X.; Shen, L. Finding the optimal reliable energy consumption path for electric vehicles under rainfall conditions. Transp. B 2024, 12, 2352492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolen, A.W.J.; Rinnooy Kan, A.H.G.; Trienekens, H.W.J.M. Vehicle routing with time windows. Oper. Res. 1987, 35, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, N. Simple heuristics for the vehicle routing problem with soft time windows. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 1993, 44, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramel, J.; Simchi-Levi, D. Probabilistic analyses and practical algorithms for the vehicle routing problem with time windows. Oper. Res. 1996, 44, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziliaskopoulos, A.K.; Mahmassani, H.S. A note on least time path computation considering delays and prohibitions for intersection movements. Transp. Res. Part B 1996, 30, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, H.J.; Zhang, H.M.; Ghosal, D.; Chuah, C.N. Dynamic traffic routing in a network with adaptive signal control. Transp. Res. Part C 2017, 85, 64–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Q.; Cheng, L.; Yuan, T.F.; Cheng, Y.; Li, M.M. The constrained reliable shortest path problem for electric vehicles in the urban transportation network. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 261, 121130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Z.Y.; Du, M.Q. Hyperpath searching algorithm considering delay at intersection and its application in CVIS for vehicle navigation. J. Adv. Transp. 2022, 2022, 2304097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.L.; Yang, H.H. Shortest paths in traffic-light networks. Transp. Res. Part B 2000, 34, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, R.K.; Orlin, J.B.; Pallottino, S.; Scutellà, M.G. Minimum time and minimum cost-path problems in street networks with periodic traffic lights. Transp. Sci. 2002, 36, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanjary, M.; Faez, K.; Meybodi, M.R.; Sabaei, M. Shortest paths in synchronized traffic-light networks. In Proceedings of the 24th Canadian Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering (CCECE), Niagara Falls, ON, Canada, 8–11 May 2011; pp. 882–886. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Yang, J.; Huang, J. The real-time shortest path algorithm with a consideration of traffic-light. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2016, 31, 2403–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.M.; Li, J.; Liu, S.X. Study on the shortest reliable path of stochastic time-dependent transportation networks considering waiting time at signalized intersections. J. Adv. Transp. 2023, 18, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Shao, H.; Wu, T.; Lam, W.H.K.; Zhu, E.C. An energy-efficient reliable path finding algorithm for stochastic road networks with electric vehicles. Transp. Res. Part C 2019, 102, 450–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Añez, T.; De La Barra, T.; Pérez, B. Dual graph representation of transport networks. Transp. Res. Part B 1996, 30, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easa, S.M. Traffic assignment in practice: Overview and guidelines for users. J. Transp. Eng. ASCE 1991, 117, 602–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanteau, R.M. Using cumulative curves to measure saturation flow and lost time. ITE J. 1988, 58, 27–31. [Google Scholar]

| Intersection | East Approach | West Approach | South Approach | North Approach | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left Turn | Straight | Left Turn | Straight | Left Turn | Straight | Left Turn | Straight | |

| I1 | 283 | 530 | 295 | 508 | 264 | 301 | 277 | 288 |

| I2 | 245 | 199 | 233 | 190 | 134 | 581 | 160 | 602 |

| I3 | 431 | 457 | 422 | 421 | 201 | 130 | 54 | 88 |

| I4 | 325 | 344 | 315 | 366 | 367 | 287 | 376 | 302 |

| I5 | 203 | 310 | 214 | 315 | 213 | 620 | 198 | 633 |

| I6 | 332 | 312 | - | 400 | 340 | - | - | - |

| I7 | - | - | 264 | - | 437 | 429 | - | 420 |

| I8 | 210 | - | - | - | - | 497 | 343 | 464 |

| I9 | 88 | 130 | 164 | 108 | 178 | 635 | 198 | 609 |

| I10 | 230 | 210 | 225 | 241 | 204 | 612 | 233 | 623 |

| I11 | 166 | 154 | 186 | 121 | 214 | 798 | 208 | 805 |

| I12 | 154 | 320 | 133 | 303 | 288 | 350 | 267 | 355 |

| I13 | 298 | 304 | 233 | 332 | 276 | 501 | 254 | 463 |

| I14 | 204 | 418 | 221 | 429 | 301 | 410 | 297 | 422 |

| I15 | 213 | 456 | 209 | 487 | 203 | 433 | 230 | 460 |

| Road Segment Number | Node | Distance (m) | Average Speed (km/h) | Travel Time (s) | Road Segment Number | Node | Distance (m) | Average Speed (km/h) | Travel Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I1–I2 | 725 | 54 | 48.33 | 12 | I7–I11 | 443 | 51 | 31.27 |

| 2 | I1–I4 | 465 | 47 | 35.62 | 13 | I8–I9 | 728 | 47 | 55.76 |

| 3 | I2–I3 | 1300 | 57 | 82.11 | 14 | I8–I12 | 270 | 48 | 20.25 |

| 4 | I2–I5 | 523 | 53 | 35.52 | 15 | I9–I10 | 613 | 46 | 47.97 |

| 5 | I–I7 | 554 | 49 | 40.70 | 16 | I9–I13 | 235 | 54 | 15.67 |

| 6 | I4–I5 | 689 | 45 | 53.92 | 17 | I10–I11 | 693 | 48 | 51.98 |

| 7 | I4–I8 | 275 | 47 | 21.06 | 18 | I10–I14 | 194 | 46 | 15.18 |

| 8 | I5–I6 | 587 | 46 | 45.94 | 19 | I11–I15 | 354 | 52 | 24.51 |

| 9 | I5–I9 | 416 | 56 | 26.74 | 20 | I12–I13 | 737 | 58 | 45.74 |

| 10 | I6–I7 | 664 | 45 | 53.12 | 21 | I13–I14 | 568 | 55 | 37.18 |

| 11 | I6–I10 | 525 | 45 | 42.00 | 22 | I14–I15 | 641 | 56 | 41.21 |

| Intersection | Cycle (s) | Phases | Phase 1 Green (s) | Phase 1 Movement | Phase 2 Green (s) | Phase 2 Movement | Phase 3 Green (s) | Phase 3 Movement | Phase 4 Green (s) | Phase 4 Movement | Phase 5 Green (s) | Phase 5 Movement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | 120 | 4 | 44 | E-W Through | 27 | E-W Left | 25 | N-S Through | 24 | N-S Left | - | - |

| I2 | 180 | 5 | 25 | E-W Through | 35 | E-W Left | 70 | S Through | 30 | N Through | 20 | N-S Left |

| I3 | 180 | 4 | 55 | E-W Through | 57 | E-W Left | 48 | S Through | 20 | N Through | - | - |

| I4 | 120 | 4 | 30 | E-W Through | 30 | E-W Left | 25 | N-S Through | 35 | N-S Left | - | - |

| I5 | 160 | 4 | 35 | E-W Through | 25 | E-W Left | 70 | N-S Through | 30 | N-S Left | - | - |

| I6 | 65 | 2 | 35 | S Release | 30 | E-W Through | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| I7 | 65 | 2 | 25 | W Release | 40 | N-S Release | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| I8 | 60 | 2 | 20 | E Release | 40 | N-S Release | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| I9 | 180 | 4 | 30 | E Release | 35 | W Release | 85 | N-S Through | 30 | N-S Left | - | - |

| I10 | 130 | 3 | 60 | N-S Through | 25 | N-S Left | 45 | E-W Through | - | - | - | - |

| I11 | 130 | 3 | 80 | N-S Through | 20 | N-S Left | 30 | E-W Through | - | - | - | - |

| I12 | 170 | 5 | 40 | E Through | 30 | W Through | 20 | E-W Left | 45 | N-S Through | 35 | N-S Left |

| I13 | 160 | 4 | 37 | E-W Through | 38 | E-W Left | 54 | N-S Through | 31 | N-S Left | - | - |

| I14 | 130 | 4 | 40 | E-W Through | 25 | E-W Left | 35 | N-S Through | 30 | N-S Left | - | - |

| I15 | 130 | 4 | 42 | E-W Through | 25 | E-W Left | 38 | N-S Through | 25 | N-S Left | - | - |

| Departure Time | Proposed Algorithm | Considering Signalized Intersection Waiting Time | Traditional Dijkstra’s Algorithm | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shortest Path | Travel Time (s) | Shortest Path | Travel Time (s) | Shortest Path | Travel Time (s) | |

| 0 | O1-I1-I4-I5-I6-I7-I11-I15-D9 | 392.16 | O1-I1-I4-I5-I6-I7-I11-I15-D9 | 379.00 | O1-I1-I4-I8-I12-I13-I14-I15-D9 | 235.06 |

| 50 | O1-I1-I4-I8-I9-I13-I14-I10-I11-I15-D9 | 462.16 | O1-I1-I4-I5-I6-I7-I11-I15-D9 | 329.00 | ||

| 100 | O1-I1-I2-I5-I6-I7-I11-I15-D9 | 421.89 | O1-I1-I4-I5-I9-I13-I14-I15-D9 | 345.21 | ||

| 150 | O1-I1-I2-I5-I6-I7-I11-I15-D9 | 371.96 | O1-I1-I4-I5-I9-I13-I14-I15-D9 | 295.21 | ||

| 200 | O1-I1-I2-I5-I6-I7-I11-I15-D9 | 322.28 | O1-I1-I2-I5-I6-I7-I11-I15-D9 | 309.00 | ||

| 250 | O1-I1-I2-I5-I6-I7-I11-I15-D9 | 403.75 | O1-I1-I4-I5-I9-I13-I14-I15-D9 | 325.21 | ||

| 300 | O1-I1-I2-I5-I6-I7-I11-I15-D9 | 353.92 | O1-I1-I4-I5-I9-I13-I14-I15-D9 | 275.21 | ||

| 350 | O1-I1-I2-I3-I7-I11-I15-D9 | 432.03 | O1-I1-I2-I3-I7-I11-I15-D9 | 419.00 | ||

| 400 | O1-I1-I2-I3-I7-I11-I15-D9 | 382.07 | O1-I1-I2-I3-I7-I11-I15-D9 | 369.00 | ||

| 450 | O1-I1-I2-I3-I7-I11-I15-D9 | 332.11 | O1-I1-I2-I3-I7-I11-I15-D9 | 319.00 | ||

| 500 | O1-I1-I4-I5-I9-I10-I14-I15-D9 | 330.17 | O1-I1-I4-I5-I9-I10-I14-I15-D9 | 309.36 | ||

| 550 | O1-I1-I4-I8-I9-I13-I14-I15-D9 | 382.07 | O1-I1-I4-I8-I9-I13-I14-I15-D9 | 374.00 | ||

| 600 | O1-I1-I2-I5-I6-I7-I11-I15-D9 | 436.96 | O1-I1-I4-I5-I9-I13-I14-I15-D9 | 365.21 | ||

| 650 | O1-I1-I2-I5-I6-I7-I11-I15-D9 | 387.32 | O1-I1-I4-I5-I9-I13-I14-I15-D9 | 315.21 | ||

| 700 | O1-I1-I2-I3-I7-I11-I15-D9 | 468.34 | O1-I1-I4-I5-I9-I13-I14-I15-D9 | 395.21 | ||

| Key Parameters | Average Travel Time (s) | Average Total Delay Time (s) | Average Ratio of Delay Time (%) | Average Improvement Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Different Algorithms | |||||

| Traditional Dijkstra’s Algorithm | 524.33 | 289.19 | 55 | 25.36 | |

| Considering Signalized Intersection Waiting Time Algorithm | 437.10 | 182.71 | 40 | 10.46 | |

| Proposed Algorithm | 391.38 | 126.35 | 32 | - | |

| Departure Time | Proposed Algorithm | Considering Signalized Intersection Waiting Time | Traditional Dijkstra’s Algorithm | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shortest Path | Travel Time (s) | Shortest Path | Travel Time (s) | Shortest Path | Travel Time (s) | |

| O1-D9 | O1-I1-I4-I8-I9-I13-I14-I15-D9 | 430.08 | O1-I1-I4-I5-I9-I13-I14-I15-D9 | 314.00 | O1-I1-I4-I8-I12-I13-I14-I15-D9 | 235.06 |

| O1-D10 | O1-I1-I4-I8-I9-I13-I14-I15-I11-D10 | 394.22 | O1-I1-I4-I5-I6-I7-I11-D10 | 261.87 | O1-I1-I2-I3-I7-I11-D10 | 233.41 |

| O1-D7 | O1-I1-I2-I5-I9-I10-I14-D7 | 290.31 | O1-I1-I4-I5-I9-I13-I14-D7 | 214.13 | O1-I1-I4-I8-I12-I13-I14-D7 | 192.85 |

| O2-D7 | O2-I1-I2-I5-I9-I10-I14-D7 | 388.29 | O2-I1-I2-I5-I9-I13-I14-D7 | 272.59 | O2-I1-I2-I5-I9-I13-I14-D7 | 190.44 |

| O5-D13 | O5-I12-I8-I4-I1-I2-D13 | 312.76 | O5-I12-I8-I4-I5-I2-D13 | 203.52 | O5-I12-I13-I9-I5-I2-D13 | 149.67 |

| Different Algorithms | Average Travel Time (s) | Average Total Delay Time (s) | Average Ratio of Delay Time (%) | Average Improvement Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key Parameters | |||||

| Traditional Dijkstra’s Algorithm | 286.04 | 131.57 | 41 | 9.71 | |

| Considering Signalized Intersection Waiting Time Algorithm | 271.07 | 104.89 | 35 | 5.13 | |

| Proposed Algorithm | 250.67 | 82.88 | 31 | - | |

| Different Algorithms | Proposed Algorithm | Considering Signalized Intersection Waiting Time Algorithm | Traditional Dijkstra’s Algorithm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key Parameters | ||||

| Average Calculated Travel Time (s) | 391.95 | 341.58 | 235.06 | |

| Average Simulated Travel Time (s) | 405.31 | 436.94 | 536.07 | |

| Average Difference in Travel Time (s) | 13.36 | 95.36 | 301.01 | |

| Ratio of Calculated to Simulated Time (%) | 96.70 | 78.18 | 43.85 | |

| Average Improvement Percentage (%) | 7.80 | 32.26 | ||

| Different Algorithms | Proposed Algorithm | Considering Signalized Intersection Waiting Time Algorithm | Traditional Dijkstra’s Algorithm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key Parameters | ||||

| Average Calculated Travel Time (s) | 363.13 | 253.22 | 200.29 | |

| Average Simulated Travel Time (s) | 381.085 | 468.24 | 471.8 | |

| Average Difference in Travel Time (s) | 17.955 | 215.02 | 271.51 | |

| Ratio of Calculated to Simulated Time (%) | 95.29 | 54.08 | 42.45 | |

| Average Improvement Percentage (%) | - | 22.87 | 23.80 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ji, B.; Zhang, P.; Sun, C.; Zhang, J.; Li, W. A Time-Dependent Dijkstra’s Algorithm for the Shortest Path Considering Periodic Queuing Delays at Signalized Intersections. Systems 2026, 14, 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010061

Ji B, Zhang P, Sun C, Zhang J, Li W. A Time-Dependent Dijkstra’s Algorithm for the Shortest Path Considering Periodic Queuing Delays at Signalized Intersections. Systems. 2026; 14(1):61. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010061

Chicago/Turabian StyleJi, Binghao, Peng Zhang, Chao Sun, Junhui Zhang, and Wenquan Li. 2026. "A Time-Dependent Dijkstra’s Algorithm for the Shortest Path Considering Periodic Queuing Delays at Signalized Intersections" Systems 14, no. 1: 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010061

APA StyleJi, B., Zhang, P., Sun, C., Zhang, J., & Li, W. (2026). A Time-Dependent Dijkstra’s Algorithm for the Shortest Path Considering Periodic Queuing Delays at Signalized Intersections. Systems, 14(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems14010061