Abstract

Citizen-centric smart city construction (SCC) has been the crucial mode for enhancing citizens’ well-being with rapid urbanization. While smart cities are constructed to improve urban operational safety, the concomitant low resilience of infrastructure, data breaches, and other issues also lead to physical, financial, and legal consequences, which therefore have the complicated the impact on citizens’ security perception of smart city construction (CSPSCC). To achieve sustainable smart city construction, it is important to clarify the influencing factors on CSPSCC. Although the enhancement of CSPSCC needs the joint efforts of citizens, government, and social organizations, the previous studies mostly focus on influencing factors from the single stakeholder. To address this gap, the theory of planned behavior was expanded to examine factors influencing CSPSCC from the perspective of participatory governance. Taking Nanjing as a case, hypotheses testing, mediating testing, and heterogeneity analysis were carried out for this theoretical model. The results show that the security governance of citizens, the government, and social organizations all had a positive impact on CSPSCC, with citizens’ behavioral intention being the most significant influencing factor. In addition, CSPSCC is also significantly affected by the citizens’ age, educational level, and usage frequency of smart city services.

1. Introduction

Over half of the global population lives in cities, and this percentage is rapidly rising [1,2]. Rapid urbanization has caused several global urban problems such as traffic jams and resource shortage [3]. In order to solve these issues, smart city construction (SCC) has become the emerging urban development paradigm adopted by most countries [4,5], which refers to the construction of smart infrastructure and the provision of smart city services that rely on smart infrastructure [6,7]. Citizen-centric SCC is committed to enhancing the well-being of citizens by providing convenient and high-quality smart city services [8,9], and the security perception is the basis of citizens’ well-being. SCC is leveraged by many cities to improve urban security. For example, Singapore has taken safety and security as one of its five national artificial intelligence (AI) strategies and has applied AI into two security improvement projects, drowning detection system and border clearance operation [10]. Rio de Janeiro in Brail tasked IBM with developing a sensor network to detect crime and prevent landslides [11]. Meanwhile, SCC sometimes make urban infrastructure networks more vulnerable, threatening citizens’ security perception. For example, the instability of the power grid system would cause failures in the communications, transportation, and even medical industries in smart cities, which would have a catastrophic impact on citizens [12]. Gartner reported that one in five communication systems have experienced a security breach in recent years [13]. SCC will not only suffer from service degradation such as miscalculation, service unavailability, and response time delay but also suffer from intentional and unintentional data breaches [14]. In the past decade, the United States has seen a 170% rise in data breaches. Facebook deliberately provided Cambridge Analytica with data from 87 million users for use in the U.S. presidential campaign [15]. These problems not only lead to physical, financial, and legal consequences but also pose a threat to citizens’ security perception.

Citizens’ security perception of smart city construction (CSPSCC) is the key criterion in evaluating the performance of SCC, and determining its influencing factors is an important prerequisite for formulating its enhancement strategies. The process of its enhancement requires the participatory governance of multiple stakeholders. As a model of empowerment and democratization, participatory governance emphasizes the transformation of the traditional top-down governance model into a triangular structure of collaborative governance between the government, social organization, and citizen [16]. Social organizations always include SCC companies, media, and non-governmental organizations. The concept of participatory governance has been applied to activities such as epidemic prevention and control [17], megaproject operation [18], and energy transition [19]. This concept is in line with the global guidelines for citizen-centric smart city development, but the previous studies mostly verified the influencing factors on certain smart city services from the perspective of a single stakeholder. For example, Lu (2024) explored the influence of the delivery speed and brand reputation of suppliers on citizens’ security perception of online shopping [20]. Putnik and Bošković (2015) verified that social media played the most crucial role in influencing students’ security perception of Internet social networking [21]. Alfalah (2023) examined how internet security awareness among university students influences their perception of cybersecurity in learning management systems from the users’ perspective [22]. Rahman et al. (2023) found that roadway users’ usage experience and attitudes significantly influence their safety perception of autonomous vehicles in smart cities [23]. Luo and Choi (2022) pointed out that the government penalty schemes have a significant impact on citizens’ security perception of e-commerce [24]. To summarize, while some studies have explored factors affecting citizens’ security perception of certain smart city services from the perspective of a single stakeholder, few have systematically examined them from the perspective of participatory governance, limiting the development of effective strategies for enhancing CSPSCC. To fill this important knowledge gap, this study would comprehensively examine the factors influencing CSPSCC from the perspective of participatory governance.

China’s urbanization is advancing rapidly, and the smart city has become the main mode of urban development in China. Since 2013, the Chinese government has announced several batches of smart city pilot projects, and there are more than 700 smart cities being constructed, which is one of the largest smart city experimental plants in the world [25]. As one of the initial batches of pilot smart cities and one of 13 megacities in China, Nanjing boasted a well-developed SCC system and had a population of 9.54 million and an urbanization rate of 87.2% in 2023 [26]. Nanjing is a good representation of the smart city in China and other similar economies. Therefore, this study will sort out the influencing factors of CSPSCC from the perspective of governance participation and take Nanjing city as a case study to verify the influencing mechanism so as to improve the CSPSCC.

2. Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Theoretical Framework in the Context of Participatory Governance

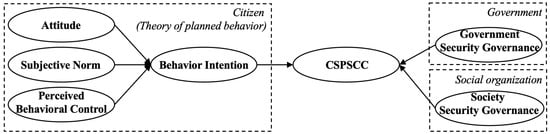

The CSPSCC studied in this paper is defined as citizens’ subjective perception of SCC to safeguard their safety through physical security, data security, and service reliability, formed based on their own usage experiences and external environmental information. Participatory governance in SCC typically always involves multiple stakeholders, including the government, social organizations, and citizens, as shown in Table 1. To ensure the comprehensiveness of this research, all three types of stakeholders were included in the theoretical framework. The influencing factors from the citizens themselves have attracted a lot of attention from scholars, and many theoretical models have been proposed. Among them, the theory of planned behavior (TPB) proposed by Ajzen (1991) is a cognitive theory used to understand and predict human perception and behavior [27] and has been widely used in the fields of emerging technique adoption perception [28], crowdfunding risk perception [29], and dangerous driving behaviors [30]. This theory ignores the influencing factors from the external environment. Therefore, the influence of Government Security Governance and Society Security Governance on CSPSCC was extended into the theoretical framework in the context of participatory governance, as demonstrated in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Stakeholders in the participatory governance in SCC.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework based on extended TPB.

2.2. Research Hypotheses

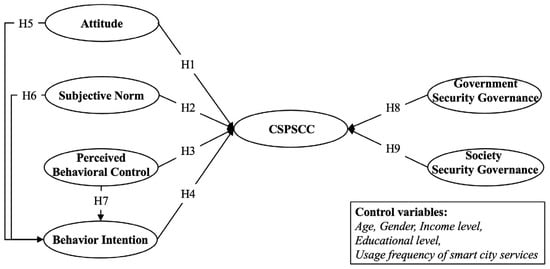

The previous studies related to CSPSCC are critically presented and discussed to develop the research hypotheses and model for influencing factors on CSPSCC in the context of participatory governance, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Theoretical model of CSPSCC.

Attitude refers to citizens’ subjective evaluation of SCC, that is, whether they think SCC is comfortable and beneficial. Subjective Norm refers to the pressure citizens feel from external environments, including friends, government, media, and companies, when making decisions about whether to adopt smart city services. Perceived Behavior Control is the ability of citizens to perceive, accept, and deal with potential security risks when using smart city services. Behavioral Intention refers to whether citizens are willing to use smart city services. These four are the original latent variables in TPB, and many studies have analyzed the influencing relationships between them. For example, Ma confirmed that information security employees’ attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control positively affected their information security perception [38]. Wang et al. also found that these three factors of individual investors were significantly associated with their perceived security in crowdfunding investment [29]. Man et al. argued that citizens’ security perception of COVID-19 vaccination was influenced by their behavior intention [39]. Therefore, the following four hypotheses are proposed.

Hypothesis 1:

Attitude is associated positively with CSPSCC.

Hypothesis 2:

Subjective Norm is associated positively with CSPSCC.

Hypothesis 3:

Perceived Behavior Control is associated positively with CSPSCC.

Hypothesis 4:

Behavior Intention is associated positively with CSPSCC.

Behavioral Intention includes citizens’ own willingness to adopt smart city services and their willingness to recommend smart city services to other people. It may not only directly affect CSPSCC but is also often affected by Attitude, Subjective Norm, and Perceived Behavioral Control. These influencing relationships are already demonstrated in the adoption intentions of various smart city services. For example, Gu et al. proved that residents’ participation intention in smart community construction was influenced by these three factors [40]. Based on the TPB, Cudjoe et al. verified that residents’ intention to adopt an intelligent waste-sorting system was influenced by these three factors [41]. The similar influencing relationship was verified regarding citizens’ behavioral intention to adopt intelligent household electrical appliances [42], farmers’ behavioral intention to use intelligent agricultural techniques [43], and teachers’ willingness to adopt smart education services [44]. Therefore, the following three hypotheses are proposed.

Hypothesis 5:

Attitude is associated positively with Behavior Intention.

Hypothesis 6:

Subjective Norm is associated positively with Behavior Intention.

Hypothesis 7:

Perceived Behavioral Control is associated positively with Behavior Intention.

For the stakeholders of the participatory governance of smart cities, in addition to the citizens themselves, there are also social organizations (e.g., supply companies, media, non-governmental organizations) and government, which will have an impact on CSPSCC. The involvement of these stakeholders is intrinsically aligned with the core tenets of participatory governance. Their security-related initiatives directly operationalize key participatory mechanisms, including transparency, co-decision-making, and accountability. Specifically, such engagement not only facilitates citizens’ access to authoritative information but also empowers them to express demands and participate in governance feedback loops, all of which collectively shape CSPSCC. For instance, Zhang et al. proposed that the safety operation of the smart public transportation sensing platform had an effective impact on the security perception of citizens [45]. Lu et al. argued that citizens’ perception of medication safety was positively correlated with exposure to television and print media while negatively correlated with social media exposure [46]. Non-governmental organization involvement also had a significant impact on the psychological security of adolescents [47] and villagers [48]. The direct impact of government normative regulations, service regulations, and incentive regulations on family farmers’ safety perception and behavior adoption has been confirmed by Zhu et al. [49]. Therefore, the following two hypotheses are proposed.

Hypothesis 8:

Government Security Governance is associated positively with CSPSCC.

Hypothesis 9:

Social Organization Governance is associated positively with CSPSCC.

Apart from the influencing factors related to citizen, social organization, and government participatory governance, the demographic of citizens might have a significant impact on CSPSCC. Many studies have shown that females tend to feel less secure than males when using ride-share services [50], digital games [51] and digital financial activities [52]. The impact of citizens’ age heterogeneity on their security perception was also verified in the areas of digital media use [53] and digital energy consumption [54]. Citizens with a higher education level and income level tend to be more sensitive to the perception of SCC [55]. Notably, the effect of smart city services usage frequency on citizens’ perceptions has also been confirmed [26]. Accordingly, the citizens’ gender, age, educational level, income level, and usage frequency of smart city services have been taken as the control variables. Nine proposed hypotheses and five control variables can be seen in Figure 2.

3. Survey Design and Data Collection

3.1. Survey Design

The questionnaire was designed to collect citizens’ perceptions so as to quantify the theoretical model of CSPSCC. The questionnaire contained three parts, of which the first part was used to outline the purpose of the questionnaire and the definition of professional terms such as security perception and SCC so as to facilitate the respondents’ understanding of the questionnaire content. The second part included choice questions about the demographic information of the respondents so as to analyze the effect of citizens’ heterogeneity on CSPSCC. The specific division of groups and their demographic information were demonstrated in Table A1 of Appendix A. The third part contained the setting questions of observed variables under each latent variable in the theoretical model. All the questions of observed variables required respondents to answer with the five-point Likert scale from and 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”).

This study employed various methods to ensure the comprehensiveness and content validity of the questionnaire. First, a systematic literature review was conducted for latent variables to determine the setting questions of the observed variables. Specifically, on 24 January 2025, according to the search strategy “Topic=smart cit*” and “Topic=intention or perception or acceptance or behavio* or consideration or willingness”, 5920 articles were retrieved from the Web of Science database. The PRISMA statement was applied to screen the literature, resulting in 48 relevant articles, from which questionnaire items related to the observed variables were extracted. Second, a committee including 17 experts specializing in smart city governance was formed to determine the setting questions of the observed variables through four rounds of the Delphi survey. Third, a pre-survey was conducted with 120 citizens to make the questionnaire items easily understood by the respondents, and the questionnaire items were revised according to their feedback and filling effect. The final questionnaire items of observed variables and their sources are demonstrated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Latent variables and corresponding observed variables in the theoretical model.

3.2. Data Collection

The questionnaires were distributed to citizens in Nanjing in March 2025 and received ethical approval from the corresponding author’s university. To ensure a comprehensive sample, respondents were randomly chosen from various community types in Nanjing and contacted via community residential committees. Electronic questionnaires are the main means of collection, and a paper questionnaire assisted by investigators is the way for the elderly or disabled to answer questions. To achieve the 95% confidence level with a 5% confidence interval, at least 385 valid responses are needed to represent 9.54 million citizens [69], and 1347 questionnaires were finally collected. By screening 117 questionnaires with a short response time and continuous identical answer items, 1230 questionnaires were used as samples with an effective rate of 91.31%.

4. Results

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was selected for its ability to simultaneously estimate complex causal pathways and mediating effects across stakeholders within a single model [26]. Consequently, it serves as the optimal method for empirically validating the extended TPB theoretical framework in this study. This study adopted the two-stage approach proposed by Anderson and Gerbing [70]. The initial stage was conducted to analyze the reliability and validity of the measured model, while the second stage tested the fit of the hypotheses to the structural model. The effect of citizens’ demographic heterogeneity on CSPSCC was tested by the Mann–Whitney U test and Kruskal–Wallis H test.

4.1. Measured Model

Reliability refers to the consistency of the results obtained from the measured model. The Cronbach’s Alpha values for the latent variables in this study range from 0.820 to 0.906, as demonstrated in Table 3, meeting the requirement of exceeding 0.7, so the reliability of the measured model is acceptable [71].

Table 3.

Descriptive statistical results of factors influencing the feeling of security.

Validity includes convergence validity and discriminative validity. Convergence validity means that observed variables measuring the same latent variable will eventually fall on the same latent variable. The values of composite reliability for latent variables satisfy the requirement of being greater than 0.7, while the values of average variance extracted satisfy the requirement of being greater than 0.5, as illustrated in Table 3. The normalized factor loading of each observed variable meets the requirement of being greater than 0.5. Therefore, the convergence validity of the measured model is acceptable [72]. Discriminative validity means that there are differences between different latent variables, and the observed variables under different latent variables will fall on different latent variables. As shown in Table 4, all latent variables among the correlation coefficients are between 0.307 and 0.560, and the square root of average variance extracted of each latent variable is greater than its correlation coefficient with other latent variables. Hence, the discriminative validity of the measured model is approvable.

Table 4.

Correlation analysis of latent variables.

4.2. Structural Model

4.2.1. Model Fitness Test

The structural model aims to test the hypotheses in the theoretical model. To test the degree of the data matching the theoretical model, the fitness indices of the model were calculated as shown in Table 5. It can be found that the actual values of all fit indices are within the acceptable range, indicating that the model fits well.

Table 5.

The acceptable ranges and actual values of fit indices.

4.2.2. Hypotheses Test

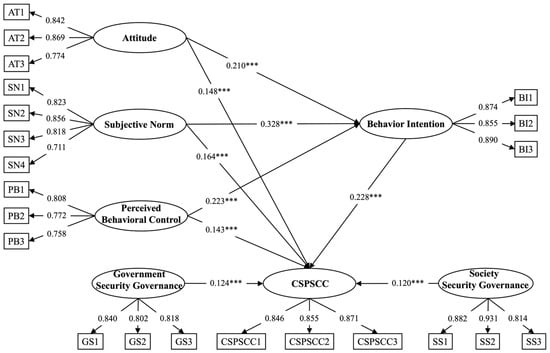

The nine hypotheses in Figure 2 are all supported at the significance level of 0.01, as presented in Figure 3 and Table 6. The results show that Attitude, Subjective Norm, and Perceived Behavior Control all have a significant positive influence on Behavior Intention. Meanwhile, Attitude, Subjective Norm, Perceived Behavioral Control, Behavioral Intention, Government Security Governance, and Social Security Governance have a significant positive influence on CSPSCC. In Figure 3, the factor loading of the observed variable on the latent variable indicates how well the observed variable explains the latent variable to which it belongs. For example, for the latent variable of Attitude, the factor loadings of AT1, AT2, and AT3 are 0.842, 0.869, and 0.774, respectively, so the explanatory ability for Attitude is that AT2 is greater than AT1 is greater than AT3. The standardized path coefficient reflects the direct influence among latent variables. For example, the standardized path coefficient from Attitude to CSPSCC is 0.148, which means that a one-unit change in Attitude will directly lead to a 0.148-unit change in CSPSCC.

Figure 3.

Analysis result of structural equation modeling. Note: *** represents p < 0.001.

Table 6.

Hypotheses test results of the theoretical model.

4.2.3. Mediating Effect Test

According to the results of the hypotheses test, it can be observed that there may be mediating effects in three influencing paths, including Behavior Intention mediating the effect of Attitude, Subjective Norm, and Perceived Behavioral Control on CSPSCC. Bootstrap (2000) was used in this study to test the significance of the mediating effect, and the results showed that the bias-corrected 95% confidence interval and percentile 95% confidence interval of these three paths all excluded a zero value. Therefore, Behavioral Intention plays a partial mediating effect among the three influence paths in Table 7.

Table 7.

Mediating effect of the theoretical model.

4.3. Heterogeneity Test of CSPSCC

In order to test the impact of citizens’ demographic heterogeneity on CSPSCC, the Mann–Whitney U test was conducted for different genders of citizens, while the Kruskal–Wallis H test was conducted for other control variables, including different ages, educational levels, income levels, and usage frequencies of smart city services of citizens. The results are presented in Table A1 of Appendix A. It was found that the p values of age and educational level were 0.000 and less than 0.05, indicating that the citizens’ age, education level, and usage frequency of smart city services had an impact on CSPSCC. The p values of gender and income level were 0.410 and 0.169, both greater than 0.05, demonstrating that the heterogeneity of gender and income level had no effect on CSPSCC. Comparing the means of different groups, it can be found that the average CSPSCC in the group of older citizens is lower. However, for education level and smart city services usage frequency, there was the opposite trend: the group with the higher education level and the group with the higher usage frequency of smart city services had a higher average CSPSCC.

5. Discussions, Implications, and Contributions

5.1. Discussions

Based on the results of the hypotheses test, mediating effect test, and heterogeneity analysis of CSPSCC, this study discusses the impact of the security governance of citizens, government, and social organizations and the citizens’ heterogeneity on CSPSCC from the perspective of participatory governance.

5.1.1. Security Governance of Citizens

According to the direct effect and indirect effect in Section 4.2, the total effect of citizen-related latent variables (i.e., Attitude, Subjective Norm, Perceived Behavioral Control, Behavior Intention) on CSPSCC can be calculated as 0.196, 0.239, 0.194, and 0.228, respectively. Crucially, a detailed examination of the path coefficients reveals that Subjective Norm exerts the strongest influence on Behavioral Intention (0.328), significantly surpassing Perceived Behavioral Control (0.223) and Attitude (0.210). This suggests that citizens’ intention to participate in SCC, and their subsequent security perception, is driven more by social influence and authoritative endorsement than by individual functional experience or personal capability. Therefore, the “indirect path” initiated by Subjective Norm serves as the most critical channel for enhancing CSPSCC via behavioral intention. To further pinpoint the source of this social influence, the observed variables of Subjective Norm were analyzed. SN2 has the highest factor loading (0.856) and mean value (3.731), while SN4 has the lowest factor loading (0.711) and mean value (2.915). This indicates that in the context of Chinese smart cities, government promotion is significantly more conducive to citizens’ use of smart city services than company promotion. This conforms to the research result of Lu et al. [46], which indicated that exposure through official channels had more positive effects than other channels. Regarding Behavioral Intention itself, the factor loadings (0.874, 0.855, 0.890) and mean values (3.889, 3.728, 3.776) of the corresponding three observed variables BI1, BI2, and BI3 are high. Since Behavioral Intention acts as a pivotal mediator that translates the effects of Attitude, Subjective Norm, and Perceived Behavioral Control into final security perception, citizens’ willingness to use should be fully mobilized. This agrees with the research result of Joo et al. [73], indicating that the Behavioral Intention of SCC represented the extent to which citizens were willing to make efforts to use smart city services and therefore is an important prerequisite for enhancing CSPSCC

5.1.2. Security Governance of Government and Social Organization

Government Security Governance and Society Security Governance hold similar path coefficients on CSPSCC. For Government Security Governance, the factor loadings (0.840, 0.802, 0.818) and mean values (3.776, 3.861, 3.941) of its three observed variables are high, indicating that the government’s governance action could significantly affect CSPSCC. In recent years, the mechanism of “unified management based on one-network” proposed by the Nanjing Municipal government has achieved remarkable results, and the Nanjing Data Bureau has been established to promote smart city construction. These initiatives have significantly enhanced the position of the government in smart city security governance, which conforms to the results of the research performed in Nanjing by Li et al. [68]. For Society Security Governance, the observed variables SS1 and SS2, which represent the supply company and media, have greater factor loadings (0.882, 0.931) and lower mean values (2.814, 2.900). This discrepancy indicates that while supply companies and media are perceived as critical determinants of security, their actual performance in Nanjing currently falls short of public expectations. The low perceived efficacy of supply companies can be interpreted through the lens of platform accountability [74]. Although supply companies are the primary providers of smart services, the frequent occurrence of network fraud and data leakage incidents suggests a governance gap where profit maximization often outweighs security obligations. This reflects a broader challenge in the digital era where the lack of robust platform accountability leads to “algorithmic irresponsibility,” causing citizens to lose trust in the technical infrastructure of smart cities. Similarly, the low score of media governance highlights the crisis of trust in media in the age of misinformation. Media acts as the information filter for citizens to perceive urban security. However, to gain better audience traffic, media outlets may deliberately exaggerate risks or spread unverified negative information [75]. Instead of functioning as a safety watchdog, such media practices amplify anxiety.

5.1.3. Heterogeneity Analysis on CSPSCC

SCC aims to enhance the well-being of all citizens, including security perception, by providing smart city services. However, the heterogeneity of citizens will lead to the digital divide in smart cities, which puts the vulnerable groups in a more disadvantageous position. This study has confirmed that the age of citizens is negatively correlated with CSPSCC, while the educational level and the usage frequency of smart city services are positively correlated with CSPSCC. Previous studies have shown that the elderly have a lower security perception due to the decline in physical fitness [76], and the low ease-of-use of smart city services always prevents elderly citizens from participating in smart city governance [77], which are the potential reasons for the low CSPSCC of elderly citizens. The higher educational level and usage frequency of smart city services can make citizens more familiar with SCC, have more knowledge of safety precautions, and hold higher CSPSCC, which agrees with the other studies [78]. This study showed that the heterogeneity of gender and income level had no significant effect on CSPSCC. Several studies conducted in Pakistan [79] and the United States [80] show that the difference in citizens’ income level has an impact on CSPSCC. The possible reason is that China’s SCC is predominantly government-led and public-welfare-oriented. In this context, most smart city services are provided as public goods with minimal or no direct cost to end-users. This inclusive approach ensures equitable access regardless of economic status, thereby effectively mitigating wealth-based digital inequalities and preventing the emergence of a security perception gap driven by income disparity.

5.2. Implications

According to the analysis and discussion of the results, three implications involving citizens, government, and social organizations were proposed to enhance the CSPSCC.

5.2.1. Citizens Should Actively Acquire Knowledge of SCC Security

Behavioral Intention is the latent variable with the highest total effect on CSPSCC, so citizens themselves should actively enhance their willingness to use smart city services. This intention is often influenced by citizens’ heterogeneity in age, educational level, and usage frequency of smart city services. The citizens with a high age, low education level, and low usage frequency of smart city services always hold low security perception and even lose rights and interests due to a lack of SCC security knowledge. To address this, citizens should take the initiative to learn about security knowledge related to smart city services by accessing educational content released through official government channels. This will help deepen their understanding of the operational mechanisms and potential risks of smart cities. At the same time, different demographic groups should be encouraged to participate in tailored training activities. For example, young people can engage in school-based safety courses to understand the formation and prevention of potential risks in smart cities. Elderly citizens can enhance their awareness and coping abilities by actively attending community-based lectures on the security of SCC.

5.2.2. Governments Should Improve the Policy and Legal System for SCC Security

Government security governance has a significant impact on CSPSCC. Although governments in smart cities mostly have published relevant policies and laws to safeguard citizens’ rights and security, the constantly updated smart city technologies (e.g., autonomous vehicles, telemedicine, humanoid robots) always break through the scope of existing policies and laws, bringing cybersecurity and data privacy issues, which poses a serious threat to CSPSCC. Therefore, the government should strengthen the review of SCC put into commercialization and publish systematic policies and laws in a timely manner to promote the healthy development of the standardization and industrialization of SCC. On the other hand, as SCC permeates every corner of our daily lives, citizens’ dependence on SCC is gradually increasing, and their needs and expectations are constantly changing. This also puts forward more of a need for the transparency, reliability, and security of SCC, so the government should continue to perfect the policy and legal system to satisfy the changing needs of the public.

5.2.3. Social Organizations Should Refrain from Disseminating Misinformation

The security governance of social organizations is an indispensable strength of enhancing CSPSCC. With the progress of mobile communication technology, the media have become one of the main channels for citizens to obtain external information, which has a strong influence on disseminating information and shaping public cognition. The media should objectively report the hot spots of public concern, avoid exaggerating or hyping misinformation, and reduce unnecessary panic among the public. As an important complementary force of the government, the media should convey the government’s policies and measures on smart city security in a timely manner so that the public can understand the efforts and guarantees made by the government. In addition, supply companies should proactively provide citizens with transparent information about SCC, including the purpose and process of data collection, storage, and use, to enhance public trust. Supply companies should also establish the user feedback mechanism to collect public opinions and suggestions on security issues, continuously improve and optimize security measures, and ensure that SCC meet public expectations and needs.

5.3. Contributions

By constructing and validating a participatory governance theoretical framework, this research not only clarifies the influencing mechanism of CSPSCC but also offers distinct theoretical advancements. The specific theoretical contributions are elaborated in the following three dimensions.

5.3.1. Extending TPB Framework with External Governance Factors

This study significantly advances the TPB by extending its applicability from individual cognitive factors to external governance determinants. Traditional TPB applications primarily focus on internal psychological variables. However, this study argues that in the complex socio-technical environment of smart cities, citizens’ perceptions are not only formed in isolation but are also deeply embedded in the external governance structure. While extant literature often treats the environmental context as a passive backdrop for individual decision-making, this study reconceptualizes it as an active driver of psychological security. By integrating “Government Security Governance” and “Society Security Governance” as key external constructs into the TPB model, this research establishes a more holistic theoretical framework. This bridge between micro-level individual cognition and macro-level institutional logic overcomes the limitations of the original TPB model, offering a theoretical lens for understanding how top-down institutional guarantees and bottom-up social support synergistically reshape CSPSCC.

5.3.2. Validating the Triangular Structure of Participatory Governance in SCC

This study empirically validates the triangular governance structure composed of the government, social organizations, and citizens within the specific context of SCC. Unlike previous research that often examined these stakeholders in isolation or assumed their roles theoretically, this research utilizes empirical data to confirm that CSPSCC is shaped by the synergistic effects of this triad. This empirical evidence challenges the traditional binary of “government–citizen” often seen in urban management literature. It highlights the critical, yet often underestimated, buffering role of social organizations in mitigating the tension between technological expansion and public privacy concerns. The findings demonstrate that effective security governance involves a dynamic equilibrium where government guidance, social organization involvement, and citizen participation coexist. This proves that the sustainability of SCC relies on the functional coupling of administrative regulation, market responsibility, and social supervision, rather than relying on any single pillar.

5.3.3. Clarifying the Influencing Mechanism and Contextualizing Digital Inequality

This study provides a comprehensive elucidation of the influencing mechanism and demographic boundaries of CSPSCC. First, regarding the influencing mechanism, this research theoretically identifies “Behavioral Intention” as a critical mediator that bridges individual cognition and security perception. It reveals that security perception is not merely a passive reception, but a psychological outcome actively constructed through citizens’ willingness to participate. Second, the study confirms that while age and education create a “knowledge-based divide,” the non-significant effect of income level contrasts with market-driven contexts. This unique finding regarding income offers a critical counter-narrative to the dominant discourse on the “digital divide” derived from market-driven economies. It suggests that the public welfare strategy in infrastructure supply can effectively decouple economic status from security rights. This provides a distinct theoretical reference for other economies, demonstrating that digital equity in security perception is achievable through inclusive institutional design, effectively mitigating the “wealth-based divide” even amidst rapid urbanization.

6. Conclusions

Smart city construction has been used in many countries to improve urban operational safety, but its reliance on intelligent technology also comes with threats to citizens’ security. To realize the sustainable development of citizen-centered smart cities, it is urgent to explore the influencing factors of CSPSCC to improve the well-being of citizens. Although CSPSCC is affected by multiple stakeholders, the previous studies mostly explored the influencing factors of CSPSCC from one single stakeholder. To fill up such an important knowledge gap, this paper comprehensively explored the factors affecting CSPSCC from the perspective of participatory governance. The theoretical model was developed based on the extended TPB, which was verified by the data collected from 1230 citizens in Nanjing. The results indicate that citizens’ Behavioral Intention is the most significant factor affecting CSGCSC and plays a mediating role in Attitude, Behavioral Norm, and Perceived Behavioral Control regarding CSPSCC. The security governance of government and social organizations has an effective impact on the enhancement of CSPSCC. Age, educational level, and usage frequency of smart city services have a significant impact on CSPSCC. Lastly, policy implications were put forward, indicating citizens should actively acquire knowledge of SCC security, governments should improve the policy and legal system for SCC security, and social organizations should refrain from disseminating misinformation. Therefore, this study not only expands the research perspective of citizen perception of SCC but also provides a reference for the sustainable development of smart cities in China and other similar economies.

Some related research still needs to be conducted in the future. First, this study relied on questionnaires for data collection, which resulted in a relatively small sample size for certain demographic groups, particularly the elderly. To ensure a more comprehensive representation, future research could adopt a multi-channel data collection approach by combining social media text mining with offline field interviews. This hybrid approach would allow for a broader sample size while effectively capturing the perceptions of elderly citizens. Second, while this study explored the influencing mechanism of CSPSCC, future research should move beyond static analysis. Besides simulating the influencing path to verify the effectiveness of improvement measures, longitudinal studies are recommended to track the dynamic changes in CSPSCC as smart city projects mature. Third, to enhance the generalizability and granularity of the findings, comparative studies could be conducted between cities with different governance models. Furthermore, future works could investigate domain-specific security perceptions by specifically focusing on sectors like smart healthcare or autonomous mobility.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.H., D.L. and M.Z.; methodology, G.H. and L.W.; software, G.H. and Y.W.; validation, G.H. and Y.W.; formal analysis, G.H.; investigation, Y.W., L.W. and H.Y.; resources, D.L.; data curation, G.H. and Y.W.; writing—original draft preparation, G.H.; writing—review and editing, G.H.; visualization, G.H.; supervision, D.L.; project administration, D.L.; funding acquisition, D.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Major Program of National Fund of Philosophy and Social Science of China, grant number 22&ZD068.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| CSPSCC | Citizens’ security perception of smart city construction |

| SCC | Smart city construction |

| SEM | Structural equation modeling |

| TPB | Theory of planned behavior |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Demographic information of respondents.

Table A1.

Demographic information of respondents.

| Item | Category | Amount | Mean | Standard Deviation | Z/Chi2 Value | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 587 | 3.440 | 1.016 | −0.848 | 0.396 |

| Female | 643 | 3.391 | 1.050 | |||

| Age | Under 18 | 81 | 3.527 | 1.243 | 25.059 | 0.000 |

| 18–35 | 678 | 3.497 | 0.972 | |||

| 36–50 | 344 | 3.394 | 0.972 | |||

| 51–65 | 96 | 3.038 | 1.192 | |||

| Over 65 | 31 | 2.699 | 1.367 | |||

| Educational level | Primary school and below | 61 | 2.683 | 1.412 | 19.654 | 0.001 |

| Junior high school | 171 | 3.388 | 1.074 | |||

| High school | 457 | 3.446 | 1.021 | |||

| Junior college and Undergraduate | 439 | 3.461 | 0.896 | |||

| Master’s degree or above | 102 | 3.549 | 1.158 | |||

| Income level | Under 2500 CNY per month | 105 | 3.438 | 1.084 | 6.960 | 0.138 |

| 2501–5000 CNY per month | 433 | 3.421 | 1.056 | |||

| 5001–7500 CNY per month | 459 | 3.419 | 1.034 | |||

| 7501–10,000 CNY per month | 158 | 3.496 | 0.938 | |||

| Over 10,000 CNY per month | 75 | 3.138 | 1.015 | |||

| Usage frequency of smart city services | Rarely | 151 | 2.647 | 1.291 | 64.170 | 0.000 |

| Occasionally | 236 | 3.435 | 0.983 | |||

| Sometimes | 391 | 3.535 | 0.869 | |||

| Often | 300 | 3.534 | 0.936 | |||

| Usually | 152 | 3.594 | 1.082 |

References

- Huang, G.; Li, D.; Zhu, X.; Zhu, J. Influencing factors and their influencing mechanisms on urban resilience in China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 74, 103210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Huang, G.; Zhu, S.; Chen, L.; Wang, J. How to peak carbon emissions of provincial construction industry? Scenario analysis of Jiangsu province. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 144, 110953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Wang, Y.; Bao, H. Sharing or sparing? The trade-offs among urban services, food production and ecosystem services. Habitat. Int. 2024, 147, 103037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Li, D.; Ng, S.T.; Nie, X. Agent-based simulation modeling for enhancing the citizens’ sense of gain on smart city services in the VUCA era. In CRIOCM 2023, Proceedings of the 28th International Symposium on Advancement of Construction Management and Real Estate, Nanjing, China, 4–6 August 2023; Lecture Notes in Operations Research; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 1607–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, D.; Zhou, S.; Huang, H.; Huang, G.; Yu, L. Unveiling age-friendliness in smart cities: A heterogeneity analysis perspective based on the IAHP-CRITIC-IFCE approach. Habitat. Int. 2024, 151, 103153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, H.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, M.; Yang, Z.; Lu, L. Advancements in digital twin applications for intelligent construction quality management. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2026, 152, 03125011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yuan, J.; Chen, Y.; Wan, X.; Huang, G. Intelligent construction benefits the public: Evidence from the opinion analysis on social media. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024. Epub ahead of printing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Li, D.; Ng, S.T.; Wang, L.; Wang, T. A Methodology for assessing supply-demand matching of smart government services from citizens’ perspective: A case study in Nanjing, China. Habitat. Int. 2023, 138, 102880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Li, D.; Zhou, S.; Ng, S.T.; Wang, W. Public opinion on smart infrastructure in China: Evidence from social media. Util. Policy 2025, 93, 101886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzada, I. Citizens’ data privacy in China: The state of the art of the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL). Smart Cities 2022, 5, 1129–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Semirumi, D.T.; Rezaei, R. A thorough examination of smart city applications: Exploring challenges and solutions throughout the life cycle with emphasis on safeguarding citizen privacy. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 98, 104771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.Z.; Lin, Y.; Vokkarane, V.M.; Venkataramanan, V. Cyber-physical cascading failure and resilience of power grid: A comprehensive review. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 11, 1095303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.M.; Deebak, B.D. Security and privacy issues in smart cities/industries: Technologies, applications, and challenges. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2023, 14, 10517–10553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buil-Gil, D.; Kemp, S.; Kuenzel, S.; Coventry, L.; Zakhary, S.; Tilley, D.; Nicholson, J. The digital harms of smart home devices: A systematic literature review. Comput. Human. Behav. 2023, 145, 107770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M.; Khan Abbasi, M.A.; Khalid, T.; Shan, R.U.; Ullah, S.; Ahmad, T.; Saeed, S.; Alabbad, D.A.; Ahmad, R. Getting smarter about smart cities: Improving data security and privacy through compliance. Sensors 2022, 22, 9338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nassar, J.B.; Sharp, D.; Anwar, M.; Bartram, L.; Goodwin, S. Bridging data governance and socio-technical transitions to understand sustainable smart cities. J. Urban Technol. 2024, 31, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, C.; Kover, I.; Kyratsis, Y.; Kop, M.; Boland, M.; Boersma, F.K.; Cremers, A.L. The corona pandemic and participatory governance: Responding to the vulnerabilities of secondary school students in Europe. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 88, 103608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, G.; Felicetti, A.; Terlizzi, A. Participatory governance in megaprojects: The Lyon-Turin high-speed railway among structure, agency, and democratic participation. Policy Soc. 2023, 42, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Righettini, M.S.; Vicentini, G. Assessing and comparing participatory governance in energy transition: Evidence from the 27 European Union member states. J. Comp. Policy Anal. Res. Pract. 2023, 25, 565–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F. Online shopping consumer perception analysis and future network security service technology using logistic regression model. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2024, 10, e1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnik, N.; Bošković, M. The impact of media on students’ perception of the security risks associated with internet social networking—A case study. Croat. J. Educ. 2015, 17, 569–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfalah, A.A. The role of internet security awareness as a moderating variable on cyber security perception: Learning management system as a case study. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2023, 10, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.T.; Dey, K.; Dimitra Pyrialakou, V.; Das, S. Factors influencing safety perceptions of sharing roadways with autonomous vehicles among vulnerable roadway users. J. Saf. Res. 2023, 85, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, S.; Choi, T.M. E-commerce supply chains with considerations of cyber-security: Should governments play a role? Prod. Oper. Manag. 2022, 31, 2107–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, A.; Mao, C.; Wang, Z.; Peng, W.; Zhao, S. Finding the pioneers of China’s smart cities: From the perspective of construction efficiency and construction performance. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 204, 123410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Li, D.; Yu, L.; Yang, D.; Wang, Y. Factors affecting sustainability of smart city services in China: From the perspective of citizens’ sense of gain. Habitat. Int. 2022, 128, 102645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ud Din, S.; Wimalasiri, R.; Ehsan, M.; Liang, X.; Ning, F.; Guo, D.; Manzoor, Z.; Abu-Alam, T.; Abioui, M. Assessing public perception and willingness to pay for renewable energy in Pakistan through the theory of planned behavior. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 11, e1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Feng, X.; Zang, L. Does risk perception influence individual investors’ crowdfunding investment decision-making behavior in the metaverse tourism? Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 62, 105168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Zhan, X.; Deng, R.; Fu, X. Research on risky driving behavior of young truck drivers: Improved theory of planned behavior based on risk perception factor. J. Adv. Transp. 2024, 2024, 9966501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, B.S.; Elnaklah, R.; Agboola, O.P.; Abuhussain, M.A.; Tunay, M.; Dodo, Y.A.; Maghrabi, A.; Alyami, M. Enhancing Najran’s sustainable smart city development in the face of urbanization challenges in Saudi- Arabia. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 2024, 2905–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A.; Alizadeh, H. Societal smart city: Definition and principles for post-pandemic urban policy and practice. Cities 2023, 134, 104207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaluarachchi, Y. Implementing data-driven smart city applications for future cities. Smart Cities 2022, 5, 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Li, D.; Chen, Y.; Siano, P.; Lim, S.B.; Yigitcanlar, T. Participatory governance of smart cities: Insights from e-participation of Putrajaya and Petaling Jaya, Malaysia. Smart Cities 2022, 5, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biloria, N. From smart to empathic cities. Front. Archit. Res. 2021, 10, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masik, G.; Sagan, I.; Scott, J.W. Smart city strategies and new urban development policies in the Polish context. Cities 2021, 108, 102970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Zheng, Y. Smart city initiatives: A comparative study of American and Chinese cities. J. Urban Aff. 2021, 43, 504–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X. IS professionals’ information security behaviors in Chinese IT organizations for information security protection. Inf. Process Manag. 2022, 59, 102744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, S.S.; Wen, H.; Zhao, L.; So, B.C.L. Role of trust, risk perception, and perceived benefit in COVID-19 vaccination intention of the public. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, T.; Hao, E.; Zhang, L. Exploring determinants of residents’ participation intention towards smart community construction by extending the TPB: A case study of Shenzhen city. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024, 32, 5228–5252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudjoe, D.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H. Predicting residents’ adoption intention for smart waste classification and collection system. Technol. Soc. 2023, 75, 102381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, R.; Cai, H.; Li, L.; Zhao, Z. Smart household electrical appliance usage behavior of residents in China: Converging the theory of planned behavior, value-belief-norm theory and external information. Energy Build. 2023, 296, 113346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, G.; Chen, Y.; Li, R. Study on the influence mechanism of adoption of smart agriculture technology behavior. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asadi, Z.; Abdekhoda, M.; Nadrian, H. Understanding and predicting teachers’ intention to use cloud computing in smart education. Interact. Technol. Smart Educ. 2020, 17, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Jin, X.; Bai, S.; Peng, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J. Smart public transportation sensing: Enhancing perception and data management for efficient and safety operations. Sensors 2023, 23, 9228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Q.; Schulz, P.J.; Chang, A. Medication safety perceptions in China: Media exposure, healthcare experiences, and trusted information sources. Patient Educ. Couns. 2024, 123, 108209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandeira, M.; Graham, M.A.; Ebersöhn, L. The significance of feeling safe for resilience of adolescents in Sub-Saharan Africa. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1183748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhan, C. Building rural community disaster resilience in developing countries: Insights from a Chinese NGO’s safe rural community programme. Disasters 2023, 47, 1090–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Chen, J.; Liang, X.; Li, D.; Chen, K. Government regulations, benefit perceptions, and safe production behaviors of family farms -- A survey based on Jiangxi province, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 450, 141824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baufeldt, J.L.; Vanderschuren, M. Personal safety perception of ride-share amongst young adults in Cape Town: The effect of gender, vehicle access and COVID-19. Res. Transp. Econ. 2023, 100, 101323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigoroso, L.; Caffaro, F.; Micheletti Cremasco, M.; Cavallo, E. Developing a more engaging safety training in agriculture: Gender differences in digital game preferences. Saf. Sci. 2023, 158, 105974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodel, M.; Mesch, G. Inequality in digital skills and the adoption of online safety behaviors. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2018, 21, 712–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haunschild, I.M.S.; Leipold, B. The use of digital media and security precautions in adulthood. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2023, 2023, 1436710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strielkowski, W.; Kovaleva, O.; Efimtseva, T. Impacts of digital technologies for the provision of energy market services on the safety of residents and consumers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Chan, A.H.S.; Chen, K. Personal and other factors affecting acceptance of smartphone technology by older Chinese adults. Appl. Ergon. 2016, 54, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, V.; Wang, Y.; Wills, G. Research investigations on the use or non-use of hearing aids in the smart cities. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 153, 119231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, V. Smart cities as a testbed for experimenting with humans?—Applying psychological ethical guidelines to smart city interventions. Ethics Inf. Technol. 2023, 25, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, M.; Ali, R.; Hamid, S.; Akhtar, M.J.; Rahman, M.N. Demystifying the effect of social media EWOM on revisit intention post-COVID-19: An extension of theory of planned behavior. Future Bus. J. 2022, 8, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad Mohamed, T.Z. Extending the theory of planned behavior with government support and perceived risk to test the adoption of light electric vehicles in Tainan. Transp. J. 2024, 63, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulsara, H.P.; Trivedi, M. Exploring the role of availability and willingness to pay premium in influencing smart city customers’ purchase intentions for green food products. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2023, 62, 107–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.E.; Susanto, P.; Shah, N.U.; Khatimah, H.; Mamun, A. Al Does perceived behavioral control mediate customers’ innovativeness and continuance intention of e-money? The moderating role of perceived risk and e-security. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2023, 19, 4481–4502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumastuti, R.D.; Nurmala, N.; Rouli, J.; Herdiansyah, H. Analyzing the factors that influence the seeking and sharing of information on the smart city digital platform: Empirical evidence from Indonesia. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamamurad, Q.H.; Jusoh, N.M.; Ujang, U. Factors affecting stakeholder acceptance of a Malaysian smart city. Smart Cities 2022, 5, 1508–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, P.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Pan, K.; Yuan, D. Evaluating the effectiveness of Didi ride-hailing security measures: An integration model. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2021, 76, 139–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, P.T.I.; Lai, D.; Leung, C.K.; Yang, W. Data centers as the backbone of smart cities: Principal considerations for the study of facility costs and benefits. Facilities 2021, 39, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thi Loan, N.; Monzon Libo-on, R.; Tuan Linh, T.; Nam, N.K. Does social media foster students’ entrepreneurial intentions? Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2298191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, G.A.; Sandran, T.; Ganesan, Y.; Iranmanesh, M. Go cashless! Determinants of continuance intention to use e-wallet apps: A hybrid approach using PLS-SEM and FsQCA. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Shang, X.; Huang, G.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, M.; Feng, H. Can smart city construction enhance citizens’ perception of safety? A case study of Nanjing, China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2024, 171, 937–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, T.; Li, D.; Zhu, S.; Wang, Y. Does sponge-style old community renewal lead to a satisfying life for residents? An investigation in Zhenjiang, China. Habitat. Int. 2019, 90, 102004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Deng, X.; Hwang, B.-G.; Ji, W. Integrated framework of horizontal and vertical cross-project knowledge transfer mechanism within project-based organizations. J. Manag. Eng. 2020, 36, 04020062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhong, H.; Jing, N.; Fan, L. Research on the impact factors of public acceptance towards NIMBY facilities in China—A case study on hazardous chemicals factory. Habitat. Int. 2019, 83, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, K.; Hwang, J.; Joo, K.; Hwang, J. Acceptance of green technology-based service: Consumers’ risk-taking behavior in the context of indoor smart farm restaurants. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Yan, Y.; Li, J.; Jiang, B. Privacy and personal data risk governance for generative artificial intelligence: A Chinese perspective. Telecomm. Policy 2024, 48, 102851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisescu, O.I.; Sterie, L.G.; Mican, D. Fake News, Consumer cynicism and negative word-of-mouth: The mitigating role of trust in social media advertising. Comput. Human. Behav. 2026, 175, 108842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson-Pajala, R.M.; Alam, M.; Gusdal, A.K.; Marmstål Hammar, L.; Boström, A.M. Trust and easy access to home care staff are associated with older adults’ sense of security: A Swedish longitudinal study. Scand. J. Public Health 2024, 53, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Choudhury, A. Exploring older adults’ perception and use of smart speaker-based voice assistants: A longitudinal study. Comput. Human. Behav. 2021, 124, 106914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Tao, D. The roles of trust, personalization, loss of privacy, and anthropomorphism in public acceptance of smart healthcare services. Comput. Human. Behav. 2022, 127, 107026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.F.; Ikram, N.; Saleem, S. Digital divide and socio-economic differences in smartphone information security behaviour among university students: Empirical evidence from Pakistan. Int. J. Mob. Commun. 2023, 22, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancker, J.S.; Nosal, S.; Hauser, D.; Way, C.; Calman, N. Access policy and the digital divide in patient access to medical records. Health Policy Technol. 2017, 6, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.