Abstract

Micro and small enterprises (MSEs) in emerging markets often face resource and capability constraints, highlighting the need to leverage digital innovation for improved performance. Although entrepreneurial orientation (EO) is widely recognized as a driver of firm performance (FP), the capability-based mechanisms linking EO to performance through digital innovation remain underexplored. To address this gap, this study develops and empirically validates a Digital Innovation Opportunity Transformation (DIOT) framework, which explains how EO enhances FP through sequential capability mechanisms—digital opportunity recognition and digital opportunity exploitation—and how IT-environmental support (ITES) strengthens these effects. Using survey data from 286 Ethiopian MSEs and structural equation modeling, the findings reveal that EO has a significant positive impact on FP (β = 0.14, p < 0.05) and generates indirect benefits through internal digital innovation capabilities. Additionally, ITES amplifies these indirect pathways, suggesting that supportive digital infrastructures enhance the outcomes of EO-driven innovation efforts. The study advances theoretical understanding by validating the DIOT framework and elucidating the internal mechanisms linking EO to FP. It also offers practical insights for managers, technology providers, and policymakers seeking to promote EO-led digital innovation in resource-constrained emerging economies.

1. Introduction

Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO), commonly conceptualized through innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking, is widely recognized as a critical strategic posture for enhancing firm performance (FP) [1,2,3]. A substantial body of empirical research has documented a positive association between EO and FP across diverse organizational and institutional contexts [4,5]. However, growing evidence suggests that the performance outcomes of EO are neither automatic nor uniform across contexts. Rather, the effectiveness of EO is highly context-dependent and contingent upon the mechanisms through which entrepreneurial behaviors are translated into tangible outcomes, particularly in dynamic and resource-constrained environments typical of emerging markets.

Micro and small enterprises (MSEs) operating in such contexts often face severe financial, technological, and managerial constraints, alongside weak institutional frameworks and underdeveloped innovation ecosystems [6,7]. These conditions can significantly limit firms’ ability to convert EO into sustained performance gains. Although EO may provide strategic flexibility and an entrepreneurial mindset to navigate uncertainty, prior empirical findings remain inconsistent regarding how and under what conditions EO leads to superior performance, particularly in digitally transforming environments. This inconsistency highlights a critical gap in understanding the internal processes and contextual enablers that shape the EO–FP relationship in emerging economies.

The contemporary intelligence era—characterized by the rapid diffusion of artificial intelligence, big data analytics, cloud computing, and digital platforms—is fundamentally reshaping competitive dynamics and organizational practices [4,8,9]. In this environment, firms are increasingly required not only to adopt digital technologies but also to develop the capability to sense, interpret, and act upon digitally enabled market opportunities. For MSEs in emerging markets, however, traditional approaches to strategy execution are often inadequate due to limited technological infrastructure, skill shortages, and constrained managerial capabilities [10,11]. Merely adopting digital technologies does not guarantee value creation; many firms struggle to translate digital adoption into innovation-driven outcomes and measurable performance improvements. This challenge highlights the importance of dynamic “perception-to-action” capabilities, which enable firms to recognize and capitalize on digital innovation opportunities in alignment with their entrepreneurial orientation.

Digital Innovation Opportunity Transformation (DIOT) refers to the process through which firms identify, create, and exploit market opportunities enabled by digital technologies, resulting in new products, services, processes, or business models [12,13,14]. Despite its growing relevance, systematic empirical research examining how EO translates into FP through digital innovation opportunity transformation remains limited. This gap is particularly evident in emerging markets, where institutional voids, market volatility, and technological fragmentation complicate the realization of opportunities. Moreover, external contextual conditions—such as the availability of digital infrastructure and supportive policy environments—may either facilitate or constrain this transformation process; yet, their moderating influence on EO-driven performance outcomes remains underexplored.

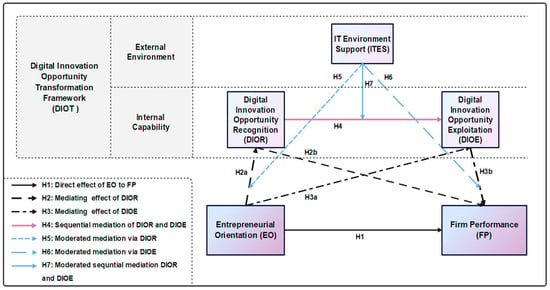

To address these limitations, this study conceptualizes DIOT as a sequential internal transformation mechanism comprising Digital Innovation Opportunity Recognition (DIOR) and Digital Innovation Opportunity Exploitation (DIOE), and examines how this process is conditioned by IT Environment Support (ITES). By integrating internal capability development with external environmental support, the proposed DIOT framework offers a coherent explanation of how EO-driven entrepreneurial behaviors are converted into tangible performance outcomes under conditions of resource scarcity and digital uncertainty.

Ethiopia provides a particularly relevant empirical context for examining these relationships. As an emerging economy undergoing institutional transition, Ethiopia has placed increasing emphasis on industrialization, digitalization, and private sector development [15]. Nevertheless, the entrepreneurial landscape remains characterized by institutional voids, limited technological infrastructure, and weak innovation capabilities. MSEs dominate Ethiopia’s economic structure and play a central role in employment creation and economic growth, yet they frequently exhibit low productivity and constrained performance outcomes. These conditions make Ethiopia an appropriate setting for examining whether and how EO can be effectively leveraged through digital innovation opportunity transformation to enhance FP.

Against this backdrop, the central research problem addressed in this study is the lack of a clear and empirically validated explanation of how entrepreneurial orientation is transformed into firm performance through digital innovation opportunity processes, and how this transformation is contingent upon external IT environment support in emerging market MSEs. While prior studies have predominantly examined the direct effects of EO on FP, they have devoted insufficient attention to the sequential mediation mechanisms and contextual moderators that determine when, how, and under what conditions EO leads to performance gains in digitally constrained environments. This study directly responds to this problem by developing and empirically testing a moderated sequential mediation framework that captures both internal transformation processes and external environmental contingencies.

Accordingly, this study addresses the following research questions, which are explicitly aligned with the identified research problem and the proposed DIOT framework:

- RQ1: How does EO influence FP in MSEs in emerging markets?

- RQ2: How do internal capabilities—specifically DIOR and DIOE—mediate the EO–FP relationship?

- RQ3: How does ITES moderate the sequential mediation of EO on FP through DIOR and DIOE?

Using survey data collected from 286 MSEs in Ethiopia, this study empirically tests the proposed moderated sequential process model using Structural Equation Modelling (SEM). The principal theoretical contribution lies in the development and empirical validation of the DIOT framework, which extends EO research beyond direct-effect models by incorporating dynamic internal mechanisms and contextual boundary conditions. By integrating Innovation Opportunity Theory and the Resource-Based View, the framework responds to long-standing calls for greater attention to mediation processes and environmental heterogeneity in entrepreneurship research.

From a practical perspective, the findings offer actionable guidance for entrepreneurs, managers, technology providers, and policymakers on how to systematically recognize and capitalize on digital opportunities, design agile decision-making processes, and leverage supportive IT environments to convert EO into sustainable performance outcomes. External actors—particularly policymakers and technology providers—are highlighted as critical enablers through investments in digital infrastructure, innovation incentives, and ecosystem development initiatives, especially in resource-constrained and digitally fragmented emerging markets, including Sub-Saharan Africa.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the theoretical foundation and develops the hypotheses. Section 3 describes the materials and methods, including the research design, sampling, data collection, measurement tools, and analytical approach. Section 4 reports the data analysis and empirical findings. Section 5 discusses the results in the context of relevant theoretical frameworks and empirical studies. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper, highlights its implications and limitations, and suggests directions for future research.

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Entrepreneurial Orientation and Firm Performance

Entrepreneurial orientation refers to a firm’s strategic posture characterized by innovativeness, risk-taking, and proactiveness in responding to market dynamics and seizing emerging opportunities [1]. A substantial body of literature suggests a strong correlation between EO and FP [16,17]. For instance, empirical studies indicate that firms with higher EO exhibit superior performance outcomes by effectively responding to competitive pressures and exploiting market opportunities [18,19]. Similarly, underscores the importance of core EO dimensions—proactiveness, risk-taking, and innovativeness—as key drivers for managing fluctuating environments and pursuing expansion opportunities, ultimately leading to superior business results [20].

Existing research also indicates that EO strengthens innovation capability, speeds up decision-making processes, and improves the allocation of internal resources. These effects together contribute to higher firm performance and stronger competitive positions [21]. Firms that actively implement entrepreneurial practices—such as fostering entrepreneurial decision-making, initiating new ventures, and launching innovative products—are empirically shown to achieve measurable performance gains.

In the digital era, EO assumes even greater importance as firms must rapidly adapt to technological shifts and market uncertainties. However, evidence remains limited on the mechanisms through which EO translates into performance under digitally intensive and resource-constrained conditions, particularly for MSEs in emerging markets, where financial, technological, and managerial limitations may restrict the effective realization of EO-driven outcomes. Based on this reasoning, the study proposes the following hypothesis:

H1:

Entrepreneurial orientation has a positive impact on firm performance.

2.2. Framework Based on Digital Innovation Opportunity Transformation (DIOT)

Emerging markets are characterized by institutional volatility, technological discontinuity, and persistent resource scarcity. Firms operating in such contexts need to cultivate dynamic capabilities that enable them not only to sense potential opportunities but also to transform them into commercial outcomes [22]. In these contexts, opportunity emergence in these settings typically occurs at the nexus of technological evolution, shifting consumer demands, and policy changes [10]. However, translating such opportunities into performance gains requires more than recognition alone; it depends on firms’ ability to mobilize and reconfigure resources and to implement appropriate strategic actions, often through resource orchestration and business model innovation [23].

Empirical research demonstrates that under conditions of high uncertainty, a firm’s ability to identify and exploit innovation opportunities is a critical determinant of both performance and long-term survival [24]. In the digital era, opportunity recognition and exploitation are increasingly shaped by advanced digital technologies, including big data analytics, cloud computing, and artificial intelligence. These technologies enhance firms’ capacity to sense, evaluate, and act on emerging opportunities with greater speed and precision [25]. Digital innovation, therefore, goes beyond the simple adoption of new technologies; it represents a strategic process through which firms develop new products, services, and business models, improve organizational performance, and strengthen competitive advantage [26,27,28]. Recent research further highlights the role of digital transformation maturity and dynamic capabilities, which reflect a firm’s ability to systematically integrate, adapt, and leverage digital technologies to achieve sustained value creation in complex and resource-constrained environments [10,12,22].

Building on these insights, this study develops the DIOT framework to explain how EO translates into FP in emerging market contexts. The framework integrates internal capability mechanisms with external environmental conditions to provide a more holistic explanation of performance outcomes. Specifically, the internal mechanism unfolds through two sequential transformation capabilities. DIOR reflects a firm’s ability to detect changes in markets and technologies through data analytics, market intelligence, and knowledge assimilation [29]. DIOE denotes the capacity to convert recognized opportunities into economic value through the application of digital technologies and business model innovation [30,31].

Together, these stages constitute the core transformation process within the DIOT framework, illustrating how firms scan market signals, interpret digital trends, and reconfigure internal resources to convert opportunity insights into measurable performance outcomes. Rather than relying on broad capability concepts, this study provides a context-specific explanation of how EO becomes operational and performance-enhancing through a sequential process of digital opportunity recognition and exploitation. The external mechanism of this framework is embodied in ITES, which captures the availability of digital infrastructure, data access, platform services, and institutional support that facilitate innovation processes [32]. A supportive digital ecosystem expands firms’ capacity to sense emerging opportunities, reduces transformation costs, accelerates resource recombination, and ultimately strengthens the linkage between EO and FP.

2.2.1. Internal Capability: DIOR and DIOE as Mediators

Although prior research on EO has identified mediating factors such as absorptive capacity, financial performance, and networking capabilities [33,34,35], these mechanisms are largely conceptualized in traditional innovation settings. As a result, they offer limited explanatory power for understanding how EO influences FP under conditions of digital transformation.

In digitally intensive environments, the capability to recognize and exploit technology-enabled opportunities becomes central to value creation, making DIOR and DIOE more suitable mediating mechanisms [36]. Empirical evidence shows that firms with stronger EO and entrepreneurial alertness are better able to identify emerging digital opportunities and respond to them effectively [37,38]. Likewise, the perception of technological opportunities stimulates investment in innovation activities, thereby reinforcing firms’ digital capability base [39]. Accordingly, DIOR and DIOE provide theoretically meaningful pathways for explaining how EO translates into performance outcomes in digitalized entrepreneurial settings.

DIOR captures how firms interpret digital shifts and market signals through intelligence systems, analytics, and knowledge transformation processes, corresponding to the “sensing” dimension in the dynamic capability literature [29]. Conversely, DIOE reflects firms’ ability to mobilize resources and transform recognized opportunities into new offerings, technologies, or business models, representing the “execution” phase of opportunity transformation [30,31]. Together, these stages depict a progression from recognizing opportunity potential to extracting value from it.

EO enhances a firm’s innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking, which in turn improves the ability to identify digital innovation opportunities [40,41]. In resource-constrained environments, this capability enables firms to discover scalable digital opportunities with manageable risk exposure. However, DIOR alone does not generate performance gains. Firms must also activate DIOE to translate insights into viable innovations, which requires deliberate resource allocation and alignment of the business model [20,42]. The perception–action logic supports this sequencing, suggesting that effective execution must be preceded by the interpretation of opportunities [43]. Accordingly, EO is expected to foster DIOR, which subsequently stimulates DIOE, leading to performance enhancement. This sequential mediation provides a coherent mechanism linking strategic orientation to outcomes, particularly for MSEs navigating uncertainty and digital transformation in emerging economies.

Based on the above analysis, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2:

DIOR mediates the relationship between EO and FP.

H2a:

EO has a significant positive effect on DIOR.

H2b:

DIOR has a significant positive effect on FP.

H3:

DIOE mediates the relationship between EO and FP.

H3a:

EO has a significant positive effect on DIOE.

H3b:

DIOE has a significant positive effect on FP.

H4:

DIOR and DIOE sequentially mediate the link between EO and FP, such that EO positively affects FP through the successive mediation of DIOR and DIOE.

2.2.2. External Environment: ITES as a Moderator

IT Environment Support (ITES) functions as a key contextual enabler that shapes how EO translates into FP, particularly for MSEs operating in resource-constrained emerging markets [44]. ITES comprises digital infrastructure, data accessibility, platform services, and knowledge networks that facilitate the detection, interpretation, and deployment of digital innovation opportunities [45]. By enhancing informational reach and the accuracy of market signal interpretation, ITES enhances firms’ capacity to identify and validate emerging opportunities, thereby strengthening the relationship between EO and DIOR [46,47].

The moderating role of ITES becomes especially salient in the sequential process linking opportunity recognition to exploitation. Drawing on Innovation Opportunity Theory, the value of sensing activities is realized only when recognized opportunities are effectively transformed into actionable solutions [29]. ITES supplies the digital analytics, automation routines, and collaborative platforms necessary to enhance evaluation accuracy, decision-making speed, and execution reliability [48]. Consequently, ITES not only enhances the relationship between EO and DIOR but also facilitates the transformation of DIOR into DIOE, thereby amplifying the sequential pathway from recognition to exploitation and ultimately to firm performance.

This sequential moderation mechanism offers a theoretical advantage over simpler models that assume a single-stage moderation effect. By accounting for ITES at multiple stages of opportunity transformation, the model captures how external digital environments actively shape both sensing and execution capabilities, providing a deeper and more contextually relevant insight into the EO-performance connection [49,50,51]. Empirical evidence supports this perspective, showing that supportive IT environments enhance opportunity evaluation, exploitation efficiency, and outcome realization in entrepreneurial settings [49,50].

Based on this theoretical and empirical foundation, the hypotheses outlined below are as follows:

H5:

ITES moderates the indirect effect of EO on FP through DIOR, enhancing EO’s impact via opportunity recognition.

H6:

ITES moderates the indirect effect of EO on FP through DIOE, enhancing EO’s impact via opportunity exploitation.

H7:

ITES moderates the sequential indirect effect of EO on FP through DIOR and DIOE, reinforcing the full recognition-to-exploitation process.

Figure 1 provides a visual representation of the conceptual framework based on the DIOT model discussed above.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

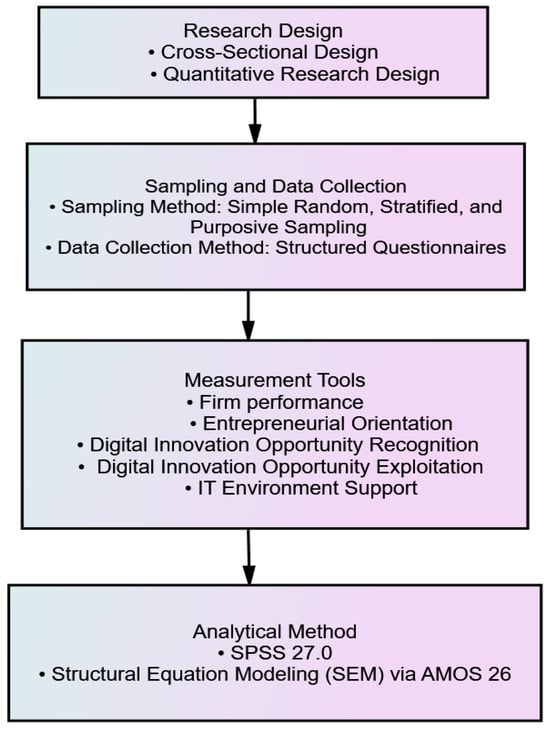

This study adopts a quantitative research design to systematically test the hypothesized relationships among the core constructs using empirical data. Quantitative approaches enhance methodological rigor by allowing structured measurement, statistical analysis, and generalization of findings across comparable contexts. In line with this approach, a cross-sectional design was employed, with data collected at a single point in time. This design is well-suited for investigating relational patterns among variables and is widely applied in research on entrepreneurial orientation and innovation. Figure 2 presents an overview of the methodological framework adopted in this study, summarizing the key stages of the research process, consistent with best practices for methodological transparency in prior empirical research [52].

Figure 2.

Methodological framework of the study.

3.2. Sampling and Data Collection

The sampling frame was obtained from the Ethiopian Micro and Small Enterprises Office, which provided an official registry of formally registered MSEs. From this population, 400 enterprises were selected using a combination of simple random and stratified sampling to ensure proportional representation across business sectors. Five major cities—Addis Ababa, Bahir Dar, Gondar, Adama, and Hawassa—were purposively selected as the research locations. These cities function as key commercial hubs with high MSE activity, relatively developed institutional support, and diverse entrepreneurial ecosystems. Such variation enhances external validity and ensures the inclusion of a geographically and socioeconomically representative sample. Data were collected through structured questionnaires administered between June and September 2025. Firm owners and managers were targeted as respondents because they serve as the primary decision-makers and possess reliable knowledge of their firms’ strategic behavior, innovation practices, and performance outcomes. This approach aligns with prior entrepreneurial research that recognizes owners and managers as appropriate key informants due to their direct involvement in business operations [53,54]. The questionnaire (as Table A1 shows) was originally developed in English and translated into Amharic using a back-translation procedure to ensure conceptual equivalence and clarity. In total, 400 questionnaires were distributed through direct on-site visits.

After screening for incomplete or inconsistent responses, 286 valid questionnaires were retained, yielding a usable response rate of 71.5%. The inclusion criteria required firms to be formally registered before January 2025, active during the data collection period, and to have responses provided by an owner or manager. Informal enterprises or firms without eligible respondents were excluded from the analysis. The final sample is considered sufficient for structural equation modeling, and a bootstrapping procedure with 5000 resamples was applied to enhance the robustness of the statistical findings.

3.3. Measurement Tools

All constructs were measured using established and validated scales widely applied in entrepreneurship and digital innovation research. Given the emerging-market context of Ethiopia, the measurement items were carefully adapted to ensure linguistic clarity, cultural appropriateness, and conceptual equivalence, following best practices for adapting cross-cultural instruments. The questionnaire was initially developed in English, translated into Amharic, and then back-translated to ensure accuracy.

A five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree) was used for all items. This scale was chosen instead of the more commonly used seven-point scale in EO research because it reduces respondent burden for MSE owners and managers with diverse educational backgrounds, improves comprehension and response consistency in field survey settings, and is supported by prior evidence showing that five-point scales enhance reliability and reduce cognitive load in emerging-market contexts [55]. The detailed measurement items are reported in Appendix A.

Firm performance. FP was measured using 6 items adapted from prior studies [56,57], capturing key dimensions of MSE growth, profitability, and competitiveness. An example item is: “The company’s average sales growth over the past three years has outperformed that of our competitors” (M = 4.62, SD = 0.51). These subjective performance measures are appropriate in contexts where audited financial data are limited and are commonly applied in MSE performance research.

Entrepreneurial Orientation. EO was measured using 12 items that covered its three core dimensions—innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking—with four items per dimension, adapted from validated scales [56,57]. An example item is: “I am capable of applying traditional business concepts in innovative ways” (M = 4.88, SD = 0.27). The three-dimensional structure aligns with the theoretical EO framework, ensuring a comprehensive measurement of strategic behaviors.

Digital Innovation Opportunity Recognition and Exploitation. DIOR was measured using 3 items, and DIOE was measured using 5 items, adapted from prior research [58]. Example items include: “We regularly develop new ideas related to products or services, target markets, and management approaches (DIOR, M = 4.56, SD = 0.64). And “We allocate adequate human resources to support the development of new business opportunities (DIOE, M = 4.65, SD = 0.47). DIOR captures the firm’s ability to identify and sense new digital opportunities, while DIOE measures the firm’s capacity to implement, mobilize resources, and convert opportunities into tangible outcomes.

IT environment support. ITES was measured using 4 items adapted from prior research [59], assessing the firm’s technological infrastructure, data processing capabilities, and digital support systems. An example item is: “Our company’s IT technology enables us to monitor and analyze customer loyalty and satisfaction” (M = 4.84, SD = 0.25). ITES captures the technological context that enables DIOR and DIOE, reflecting how IT capabilities facilitate opportunity recognition, exploitation, and overall firm performance. The five-item structure ensures comprehensive coverage of IT resources relevant to emerging-market MSEs.

3.4. Nonresponse Bias and Common Method Bias

Non-response bias was evaluated by comparing early and late respondents across key demographic and firm characteristics. The results revealed no statistically significant differences between these groups, suggesting that non-response bias does not compromise the representativeness of the sample. To address potential common method bias (CMB), multiple methodological safeguards and diagnostic procedures were implemented to mitigate this issue. First, Harman’s single-factor test showed that the first unrotated factor accounted for only 24.04% of the total variance, which is below the recommended 50% threshold [60], indicating that no single factor dominates the variance structure. Second, a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)—based common latent factor technique was employed by introducing a latent method factor onto which all indicators were loaded. Comparison between the baseline and method-factor models demonstrated no significant improvement in model fit, suggesting a limited threat from common method bias. Third, a theoretically unrelated marker variable was embedded in the instrument. The non-significant correlations between this marker variable and the core constructs provided additional evidence that CMB does not materially influence the results. Taken together, these diagnostic tests collectively support the robustness of the dataset and affirm that neither non-response bias nor CMB materially affects the accuracy of the results.

3.5. Analytical Method

This study employed a two-stage statistical analysis approach. First, SPSS 27.0 and AMOS 26.0 were used to assess the reliability and validity of the measurement model. Second, the study examined the effect of EO on FP, including a mediation analysis to explore the roles of DIOR and DIOE in the EO-performance relationship, following the procedure outlined by [61]. The robustness and significance of the associations were evaluated by analyzing standardized beta coefficients and their corresponding p-values. Additionally, IT-environment support capabilities were introduced as a moderating variable to assess their impact on the proposed relationships.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

To assess the measurement model, several criteria were evaluated, including factor loadings, internal consistency reliability, convergent validity (as reported in Table 1), and discriminant validity (as reported in Table 2). All item loadings exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.50, indicating strong indicator reliability [60]. Regarding internal consistency, the results of the SEM revealed that both composite reliability and Cronbach’s alpha values ranged between 0.70 and 0.95 for all constructs, confirming satisfactory reliability levels [62]. Convergent validity was assessed through the average variance extracted (AVE), and all constructs reported AVE values above the 0.50 threshold. This suggests that the indicators of each latent variable were strongly interrelated and captured a substantial portion of the construct’s variance [63]. Discriminant validity was further verified using the Fornell–Larcker criterion, whereby the square root of each construct’s AVE was found to be greater than its correlations with other constructs. These results support the distinctiveness of the constructs and confirm the discriminant validity of the measurement model [63].

Table 1.

Convergent validity and the reliability of constructs.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and correlations for study variables.

The confirmatory factor analysis results indicate an acceptable fit of the measurement model, meeting commonly recommended thresholds [64]. These findings confirm the adequacy of the measurement model for subsequent SEM analysis, as reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of goodness-of-fit indices.

4.2. Empirical Results and Interpretations

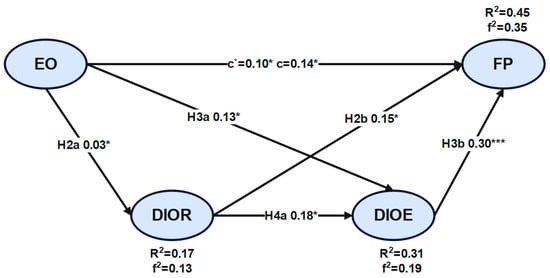

4.2.1. Main Association Analysis (H1)

The empirical results reveal a significant positive relationship between EO and FP, with a standardized path coefficient of β = 0.14, p < 0.05, thereby confirming H1 (refer to Table 4). The structural relationships, including the path coefficients for the direct effects before mediation (c = 0.14 *) and after mediation (c’ = 0.10 *), along with the R2 and f2 values for each of the FP, DIOR, and DIOE, are illustrated in Figure 3. This finding underscores EO as a pivotal strategic posture that directly enhances firm outcomes, particularly in dynamic and resource-constrained environments.

Figure 3.

Structural Equation Modeling. c’ is direct effect after mediating and c is direct effect before mediating. * p < 0.05 and *** p < 0.001.

EO, which includes innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking [65], enables firms to recognize and exploit new opportunities, respond to market shifts, and strengthen their competitive position through strategic experimentation. Innovativeness fosters novel product and process development, proactiveness ensures firms are first movers rather than followers, and risk-taking empowers bold decision-making under uncertainty.

From a theoretical standpoint, this relationship is well explained by the resource-based view [46], which argues that firm-specific capabilities that are valuable and difficult to replicate are central to sustained performance advantages. EO meets these resource criteria as a behavioral and cultural asset, particularly in emerging markets where external institutional mechanisms are often weak or inconsistent. Under such conditions, internally driven strategic orientations, such as EO, play a more important role in helping firms cope with uncertainty and institutional gaps.

This result also aligns with and extends prior findings by [66,67,68], who emphasize EO’s positive effect on performance in volatile institutional contexts. While these studies confirm EO’s capacity to promote adaptability and opportunity exploitation in resource-limited settings, the current study advances this understanding by empirically demonstrating EO’s performance-enhancing impact within digitally evolving and institutionally fragmented environments.

Table 4.

Result of structural model analysis.

Table 4.

Result of structural model analysis.

| Hypothesis | Path | Estimate (β) | S.E | C.R. | p-Value | Supported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | EO → FP | 0.14 * | 0.103 | 2.528 | 0.011 | Yes |

| H2a | EO → DIOR | 0.03 * | 0.127 | 1.959 | 0.048 | Yes |

| H2b | DIOR → FP | 0.15 * | 0.047 | 2.593 | 0.010 | Yes |

| H3a | EO → DIOE | 0.13 * | 0.098 | 2.225 | 0.026 | Yes |

| H3b | DIOE → FP | 0.30 *** | 0.067 | 4.990 | 0.000 | Yes |

Note: The model demonstrates substantial explanatory power for FP (R2 = 0.45), moderate for DIOR (R2 = 0.17), and substantial for DIOE (R2 = 0.31), in line with the thresholds proposed by [62,69]. Effect sizes (f2) indicate a large effect on FP (0.35), medium on DIOE (0.19), and small-to-medium on DIOR (0.13). * p < 0.05 and *** p < 0.001.

4.2.2. Simple Mediation and Sequential-Mediation Analysis (H2–H4)

The analysis reveals that EO significantly affects FP not only directly but also through distinct mediation mechanisms involving digital innovation capabilities. Specifically, as shown in Table 5, the indirect effect of EO on FP through DIOR is significant (β = 0.057, 95% CI [0.020, 0.410]), supporting H2. Likewise, EO indirectly enhances FP via DIOE, with a significant indirect path (β = 0.075, 95% CI [0.010, 0.205]), providing support for H3. Furthermore, the sequential mediation model reveals that EO has a significant influence on FP through the combined path of DIOR followed by DIOE (β = 0.123, 95% CI [0.007, 0.026]), thereby validating H4.

Table 5.

Simple and Sequential Mediation.

The significant mediation effects indicate that EO enhances performance partly by strengthening firms’ ability to recognize and prioritize digital opportunities (DIOR) and by enabling them to effectively mobilize resources and execute innovation (DIOE). The indirect effect through DIOR suggests that firms with higher EO tend to better detect and interpret relevant signals in their business environment, and this opportunity-recognition capability contributes meaningfully to performance improvements. Likewise, the mediation through DIOE implies that EO equips firms with the ability to transform identified opportunities into concrete innovation outcomes, reinforcing the performance impact through execution.

The validated sequential pathway (EO→DIOR→DIOE→FP) further demonstrates that EO shapes performance through a perception-to-action mechanism. Firms first translate EO-driven awareness of digital opportunities into structured recognition (via DIOR) and then convert these insights into exploitation outcomes (via DIOE), producing cumulative performance gains. This ordered mechanism aligns with entrepreneurial process views, where the progression from identifying to acting on opportunities constitutes a core pathway for generating performance.

Taken together, these mediation results highlight EO’s strategic contribution in turbulent and digitally evolving contexts. EO amplifies both opportunity-sensing and opportunity-implementing capacities, enabling firms to better navigate uncertainty and enhance innovation-led performance, thereby reinforcing its importance as a capability-developing driver within the dynamic capability logic [48].

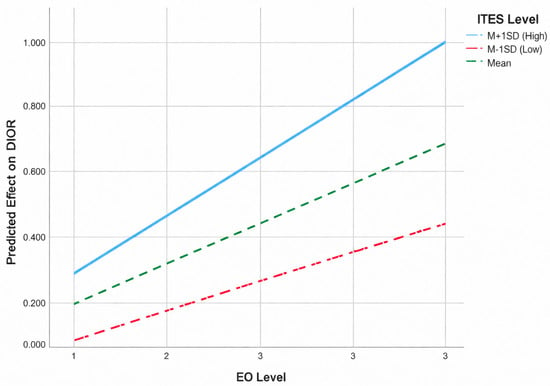

4.2.3. Moderated Mediation and Moderated Sequential-Mediation Analysis (H5–H7)

The conditional indirect effects reported in Table 6 provide empirical support for H5–H7, demonstrating that ITES operates as a contextual moderator that conditions the indirect and sequential indirect effects of EO on FP through digital innovation mechanisms.

Table 6.

Conditional Indirect Effects of EO on FP.

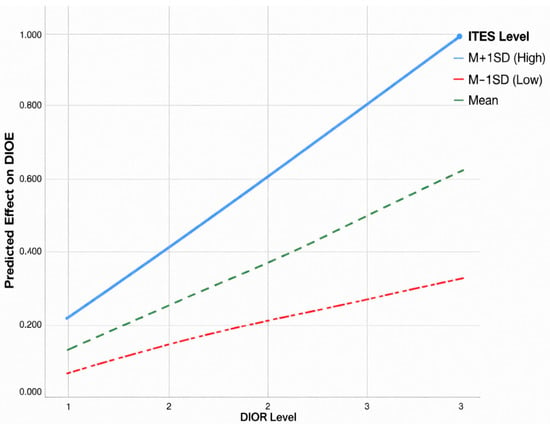

H5 proposes that ITES moderates the indirect effect of EO on FP via DIOR. The results show that this indirect effect strengthens as ITES increases. As illustrated in Figure 4, the positive relationship between EO and DIOR is stronger under high ITES conditions, indicating that firms operating in digitally supportive environments are more effective in converting EO into opportunity recognition. This conditional effect on DIOR underpins the moderated mediation mechanism, confirming that ITES enhances EO-driven sensing capabilities and, in turn, amplifies EO’s indirect impact on FP through DIOR. Thus, H5 is supported.

Figure 4.

ITES moderates the effect of EO on DIOR.

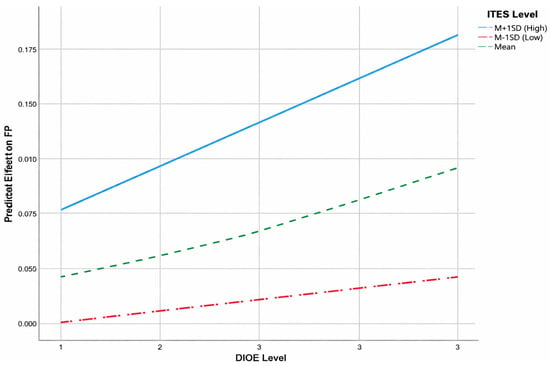

H6 predicts that ITES moderates the indirect effect of EO on FP via DIOE. The conditional indirect effects reported in Table 6 reveal a systematic increase in this pathway at higher levels of ITES. As shown in Figure 5, the relationship between DIOR and DIOE is stronger when ITES is high, suggesting that technological infrastructure and IT support facilitate the transformation of recognized opportunities into exploitable digital innovations. This pattern suggests that ITES enhances EO’s indirect performance effect by strengthening the exploitation mechanism, thereby providing support for H6.

Figure 5.

ITES moderates the effect of DIOR on DIOE.

H7 examines whether ITES moderates the sequential indirect effect of EO on FP through DIOR and DIOE, capturing the full recognition-to-exploitation process. The results reported in Table 6 indicate that the conditional sequential indirect effect increases progressively across higher levels of ITES, providing clear evidence of moderated sequential mediation. As illustrated in Figure 6, the relationship between DIOE and FP is stronger under high ITES conditions, indicating that digitally supportive environments enhance the extent to which exploited opportunities translate into superior performance outcomes. Although the magnitude of the effect is relatively modest, the consistent upward trend confirms that ITES reinforces the combined recognition and exploitation mechanisms, thereby strengthening EO’s sequential indirect impact on FP. These findings support H7.

Figure 6.

ITES moderates the effect of DIOE on FP. M represents the mean and SD denotes the standard deviation. Thus, M + 1 SD (High) indicates a value one standard deviation above the mean, while M − 1 SD (Low) indicates a value one standard deviation below the mean.

Overall, these results suggest that ITES functions primarily as a contextual amplifier rather than a direct driver of performance. Consistent with prior research [65], digitally and institutionally supportive environments reduce information frictions and operational constraints, enabling EO to exert a stronger effect on both opportunity recognition and exploitation, ultimately leading to FP. This finding is highly pertinent to emerging-market environments, where resource and structural limitations often constrain the effectiveness of EO in driving innovation-based performance outcomes.

5. Discussion

This study examined how EO—encompassing innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking—influences FP through digital innovation processes, as well as the contingent role of ITES. Consistent with H1, the findings indicate that EO has a significant positive impact on FP in emerging market contexts. EO thus remains a critical driver of competitiveness, particularly under conditions of uncertainty [66,67]. However, traditional EO–FP frameworks, largely developed in pre-digital contexts, may not fully account for contemporary challenges in emerging markets, such as weak digital infrastructure, regulatory instability, and resource constraints [48].

To address gaps in traditional EO frameworks, this study adopts the DIOT framework, positioning EO as a driver of digital innovation. Our findings strongly support H2 and H3, showing that both DIOR and DIOE independently mediate the EO–FP relationship. Empirical evidence confirms that EO significantly enhances DIOR (H2a), which, in turn, positively influences firm performance (H2b), aligning with earlier research suggesting that strategic alertness to digital innovation opportunity recognition translates into tangible performance gains [39,70,71]. Similarly, EO significantly fosters DIOE (H3a), and DIOE positively impacts performance (H3b), highlighting the importance of effectively transforming recognized opportunities into value-creating actions [42,72,73,74]. These findings collectively highlight the mediating roles of DIOR and DIOE in linking EO to FP, further reinforcing the theoretical contribution of the DIOT framework. By extending Innovation Opportunity Theory, the DIOT framework highlights that entrepreneurial success depends not only on recognizing opportunities but also on executing them effectively—especially in digitally evolving and resource-constrained environments [38,75,76].

Sequential mediation analysis (H4) confirms that EO influences FP through the pathway of DIOR and DIOE, demonstrating that opportunity recognition alone is insufficient without subsequent exploitation. This finding aligns with the DIOT framework, which posits that DIOR and DIOE routines collectively transform entrepreneurial potential into economic value. By validating the full DIOT mechanism (EO → DIOR → DIOE → FP), the study provides a process-oriented explanation of how entrepreneurial behavior translates into performance in digitalized contexts, emphasizing the complementary roles of recognition and execution.

The patterns associated with H5, H6, and H7 collectively demonstrate that the entrepreneurial process is not solely an internal strategic function but is strongly shaped by the level of ITES in which firms operate. The findings suggest that EO becomes more effective in generating performance outcomes when firms are embedded in digital environments that enhance their capacity to sense, interpret, and respond to emerging opportunities. This dynamic reinforces a core mechanism within the DIOT framework: ITES strengthens both DIOR and DIOE, thereby enhancing the transformation of entrepreneurial intent into innovation-driven outcomes [77,78]. Specifically, H5 and H6, which examine moderated mediation, indicate that ITES amplifies the indirect effects of EO on FP through distinct digital innovation mechanisms. H5 shows that ITES strengthens the effect of EO on FP through opportunity recognition, suggesting that firms with higher EO are better able to identify and prioritize valuable opportunities when they operate within supportive IT environments that provide connectivity, digital infrastructure, and resources for sensing opportunities. H6 demonstrates that ITES enhances the effect of EO on FP through opportunity exploitation, indicating that firms in richer ITES can more effectively mobilize and deploy resources to implement and commercialize the opportunities they identify. Furthermore, H7 highlights that ITES moderates the entire sequential process linking EO, opportunity recognition, opportunity exploitation, and firm performance. This finding implies that the combined recognition-to-exploitation process is most effective when firms operate in digitally supportive ITES, where ecosystem-level resources facilitate the translation of entrepreneurial intent into tangible performance outcomes [79]. In emerging markets—where institutional volatility, cultural risk aversion, and chronic resource constraints often weaken firms’ ability to convert entrepreneurial drive into tangible performance—ITES provides the essential informational, infrastructural, and coordination advantages that enable MSEs to innovate under uncertainty [22,48].

6. Conclusions, Implications, Limitations, and Future Research Directions

6.1. Conclusions

The present study advances the DIOT framework, offering a process-oriented understanding of how EO drives FP through digital innovation mechanisms. The findings from this study demonstrate that EO has a direct and positive effect on FP and that its impact is mediated by DIOR and DIOE, both independently and sequentially. This highlights that performance improvements depend on the full transformation from opportunity identification to actionable innovation. Additionally, ITES moderates all key pathways, indicating that the effectiveness of EO in driving performance is contingent on supportive digital and institutional contexts. These findings not only provide theoretical clarity on the EO–FP relationship in resource-constrained, digitally evolving environments but also extend Innovation Opportunity Theory by empirically validating the DIOT process. In particular, the study shows how integrating internal entrepreneurial capabilities with external environmental enablers enhances innovation-driven performance, offering a nuanced understanding of the mechanisms through which EO translates into firm success.

6.2. Theoretical Contributions

This study makes three key theoretical contributions to the literature on EO and digital innovation, particularly in emerging market contexts.

First, it develops the DIOT framework, which systematically explains how EO drives FP through internal mechanisms—DIOR and DIOE—and external support from the ITES. By integrating insights from Innovation Opportunity Theory and the RBV, DIOT addresses critical gaps in prior research, including a limited understanding of mediation mechanisms and insufficient attention to contextual heterogeneity [36,38]. This framework provides a theoretically grounded lens for understanding how strategic intent is translated into tangible innovation outcomes during digital transformation, emphasizing the process through which EO generates value, rather than only measuring its direct effects.

Second, the study advances understanding of the internal processes linking EO to FP by establishing the dual and sequential mediating roles of DIOR and DIOE. This sensing–acting pathway demonstrates that entrepreneurial firms first detect emerging digital signals and market opportunities (DIOR), which must subsequently be transformed into actionable innovations (DIOE) to generate performance gains. By highlighting this process-oriented mechanism, the study extends beyond traditional direct EO-performance links [19,20], demonstrating that opportunity recognition alone is insufficient and that value creation depends on effective execution. These insights are particularly relevant for MSEs in emerging markets, where limited resources necessitate reliance on internal innovation competencies, reinforcing the RBV perspective that EO constitutes a valuable, rare, and inimitable resource [80].

Third, the study extends theoretical understanding of how external digital environments shape the EO–FP relationship. Drawing on RBV and innovation opportunity theory, the findings demonstrate that ITES—including access to platforms, data infrastructures, and digital collaboration tools—amplifies EO’s effectiveness across the stages of digital opportunity transformation. Specifically, ITES strengthens the translation of EO into DIOR [81], the transition from DIOR to DIOE [29], and the performance impact of DIOE [45]. This underscores that external digital environments function as active moderators rather than passive backdrops, shaping the strategic execution of entrepreneurial initiatives—particularly in emerging markets by institutional voids, information asymmetry, and uneven digital infrastructure.

6.3. Practical Implications

The findings of this study offer several actionable implications for managers and entrepreneurs, technology providers, and policymakers, particularly in emerging-market contexts where resource constraints are common.

For entrepreneurs and managers of MSEs, the results highlight the importance of systematically recognizing and capitalizing on digital innovation opportunities. Specifically, the sequential process of DIOR followed by DIOE ensures that EO translates into tangible performance gains. This aligns with recent evidence indicating that higher levels of digital innovation significantly enhance MSEs’ innovation performance [82,83]. Managers are encouraged to institutionalize structured routines for environmental scanning, iterative innovation, and decision-making agility, while fostering an organizational culture that supports experimentation and employee participation. Furthermore, adopting scalable and cost-effective digital technologies, such as cloud-based platforms, low-code tools, and mobile-first applications, can help resource-constrained firms implement innovation strategies effectively.

For technology providers, the findings underscore their key role in enabling MSEs to transform EO into FP through digital innovation. By offering accessible and adaptable digital tools, providers can help firms recognize opportunities (DIOR) and convert them into actionable innovations (DIOE). Additionally, partnerships with NGOs, academic institutions, and development agencies to deliver digital training and local support further strengthen firms’ ability to implement these innovation strategies. Such support ensures that MSEs can effectively translate EO into improved performance, particularly in resource-constrained and digitally fragmented emerging markets.

For policymakers and development stakeholders, the findings emphasize their crucial role in shaping an enabling environment. The study demonstrates that ITES significantly moderates the EO-performance relationship, indicating that robust digital infrastructure and supportive policies are essential for translating EO into FP. Investments in broadband expansion, digital public services, innovation grants, tax incentives, and regulatory sandboxes can reduce adoption costs for MSEs. Additionally, fostering innovation ecosystems through incubators, accelerators, public–private partnerships, and cross-sectoral collaboration enhances the systemic conditions under which EO-driven digital innovation can thrive. Empirical evidence supports these strategies, showing that enhanced digital infrastructure and supportive policy frameworks significantly improve MSEs’ innovation outcomes and performance [84].

6.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study advances scholarly understanding of how EO translates into FP through sequential digital innovation opportunity transformation—namely, DIOR and DIOE—within the context of MSEs in Ethiopia. However, several limitations should be acknowledged.

First, the findings are set within a single emerging-economy context, where institutional capacity, technological readiness, and market dynamism differ from those in other regions. While this contextual specificity strengthens theoretical relevance for resource-constrained economies, it also limits generalisability. Comparative or multi-country studies could validate whether the sequential transformation mechanism (EO → DIOR → DIOE → FP) holds under different institutional, cultural, and technological conditions.

Second, although the cross-sectional design provides initial empirical evidence, it restricts causal interpretation and masks the temporal evolution of entrepreneurial behavior and innovation outcomes. Longitudinal designs or panel datasets would allow researchers to trace capability development, opportunity transformation sequencing, and performance trajectories over time.

Third, the reliance on self-reported perceptions introduces potential bias; future research could triangulate subjective measures with objective sources such as audited financial reports, digital usage metrics, or innovation output data to enhance measurement robustness.

Fourth, digital transformation patterns differ across sectors and organizational scales. Testing this model across high-tech industries and larger enterprises would enrich external validity and reveal sector-specific differences in how opportunity recognition and exploitation translate into performance.

Finally, future studies could deepen theory development by exploring additional mechanisms, such as learning capability and absorptive capacity, to extend the moderated mediation framework. Such inquiries would refine knowledge on how and under what conditions EO activates digital innovation opportunity processes and contributes to firm performance in emerging-market settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.A.W., R.M. and J.Z.; methodology, B.A.W.; software, R.M. and B.A.W.; validation, R.M., B.A.W. and J.Z.; formal analysis, B.A.W.; investigation, B.A.W.; resources, R.M.; and data curation, B.A.W.; writing—original draft preparation, B.A.W.; writing—review and editing, R.M. and J.Z.; visualization, R.M. and J.Z.; supervision, R.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China [Grant number 17BGL209]; This work was supported by the Hubei Provincial Key Research Project in Soft Science [2023EDA104]; This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities [Grant number WUT:104972024KFYrs0007].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it involved a questionnaire-based survey of firm owners and managers, did not collect personal or sensitive data, ensured anonymity and confidentiality, and posed no foreseeable risk to participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All of the data sets used in the manuscript are available upon the author’s reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate all the support from the School of Management, Wuhan University of Technology. The author would like to thank all those who participated in the survey for their valuable input.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EO | Entrepreneurial Orientation |

| DIOT | Digital Innovation Opportunity Transformation |

| DIOR | Digital Innovation Opportunity Recognition. |

| DIOE | Digital Innovation Opportunity Exploitation |

| ITES | IT Environment Support |

| FP | Firm performance |

| MSEs | Micro and Small Enterprises |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Questionnaire.

Table A1.

Questionnaire.

| Measurement Items | |

|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial Orientation | |

| EO1 | I am capable of applying traditional business concepts in innovative ways. |

| EO2 | I feel excited and energized when I develop new business ideas. |

| EO3 | Over the past five years, my business has introduced new products or improved existing ones. |

| EO4 | I consistently explores and implements new approaches to products, services, or processes. |

| EO5 | I take proactive steps instead of merely reacting to competitors’ actions. |

| EO6 | I constantly seeks out new business opportunities. |

| EO7 | I consistently recognizes and offers products that meet the evolving needs of customers. |

| EO8 | I actively plans and implements strategies to capitalize on emerging market trends. |

| EO9 | I am willing to take risks with my own and my family’s well-being to benefit my business. |

| EO10 | Taking courageous steps is essential to achieving my business goals. |

| EO11 | I actively take calculated risks to grow and improve my business. |

| EO12 | I makes bold decisions in uncertain situations to advance business objectives. |

| Digital Innovation Opportunity Recognition. | |

| DIOR1 | We regularly generate new ideas for products and services to meet market demands. |

| DIOR2 | We actively explore opportunities arising from technological advancements and digital changes. |

| DIOR3 | We systematically identify and pursue opportunities based on evolving customer needs and preferences. |

| Digital Innovation Opportunity Exploitation | |

| DIOE1 | We allocate adequate human resources to support the development of new business opportunities. |

| DIOE2 | We allocate financial resources to support the development of new entrepreneurial opportunities. |

| DIOE3 | We improve or develop our products and services to capitalize on emerging business opportunities. |

| DIOE4 | We adjust or refine our management models to capitalize on emerging business opportunities. |

| DIOE5 | Based on new business opportunities, we explore new markets. |

| IT Environment Support | |

| ITES1 | Our company’s ITES enables us to monitor and analyze customer loyalty and satisfaction. |

| ITES2 | Our company’s ITES can identify and address the unique needs of different customer segments. |

| ITES3 | Our ITES enables efficient extraction of meaningful market and customer insights from big data. |

| ITES4 | Our company’s ITES enables the analysis and forecasting of market interest in new products. |

| Firm Performance | |

| FP1 | The company’s average sales growth over the past three years has outperformed that of our competitors. |

| FP2 | The company’s average profitability over the past three years has exceeded that of our competitors. |

| FP3 | Average return on investment over the past three years has been higher than that of our competitors. |

| FP4 | Average market share growth over the past three years has surpassed that of our competitors. |

| FP5 | Average employment growth over the past three years has exceeded that of our competitors. |

| FP6 | Customer loyalty and retention over the past three years have been stronger compared to our competitors. |

References

- Covin, J.G.; Slevin, D.P. Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments. Strateg. Manag. J. 1989, 10, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehe, M.A.; Sesabo, J.K.; Isaga, N.; Mkuna, E. Individual entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: The mediating role of sustainable entrepreneurship practices. Sustain. Technol. Entrep. 2024, 3, 100079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcadell, F.J.; Úbeda, F. Individual entrepreneurial orientation and performance: The mediating role of international entrepreneurship. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2022, 18, 875–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.W.; Umar, M.; Khaddage-Soboh, N.; Safi, A. From innovation to impact: Unraveling the complexities of entrepreneurship in the digital age. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2024, 20, 3207–3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirumalla, K.; Oghazi, P.; Nnewuku, R.E.; Tuncay, H.; Yahyapour, N. Critical factors affecting digital transformation in manufacturing companies. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2025, 21, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Cai, L.; Fei, Y. Knowledge integration methods, product innovation, and high-tech new venture performance in China. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2019, 31, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusa, R.; Suder, M.; Duda, J. Role of entrepreneurial orientation, information management, and knowledge management in improving firm performance. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2024, 78, 102802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, A.; El Sawy, O.A.; Pavlou, P.A.; Venkatraman, N. Digital Business Strategy: Toward a Next Generation of Insights. MIS Q. 2013, 37, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paek, B.; Lee, H. Strategic entrepreneurship and competitive advantage of established firms: Evidence from the digital TV industry. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2018, 14, 883–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Dynamic capabilities and management systems theory. J. Manag. Organ. 2018, 24, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suder, M. Determinant or moderator ? Exploring the role of the dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation and the firm. Entrep. Int. J. Manag. 2025, 21, 87. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, S.; Durst, S.; Ferreira, J.J.; Veiga, P.; Kailer, N.; Weinmann, A. Digital transformation in business and management research: An overview of the current status quo. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 63, 102466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leso, B.H.; Cortimiglia, M.N.; Ghezzi, A.; Minatogawa, V. Exploring digital transformation capability via a blended perspective of dynamic capabilities and digital maturity: A pattern matching approach. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2024, 18, 1149–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.G.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.K. Technical founders, digital transformation, and corporate technological innovation: Empirical evidence from listed companies in China’s STAR market. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2024, 20, 3155–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebreeyesus, M. Innovation and microenterprise growth in Ethiopia. In Entrepreneurship, Innovation, and Economic Development; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauweraerts, J.; Pongelli, C.; Sciascia, S.; Mazzola, P.; Minichilli, A. Transforming entrepreneurial orientation into performance in family SMEs: Are nonfamily CEOs better than family CEOs? J. Small Bus. Manag. 2023, 61, 1672–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardi, Y.; Susanto, P.; Abror, A.; Abdullah, N.L. Impact of entrepreneurial proclivity on firm performance: The role of market and technology turbulence. Pertanika. J. Soc. Sci. Hum. 2018, 26, 241–250. [Google Scholar]

- Alqahtani, N.; Uslay, C.; Yeniyurt, S. Comparing the moderated impact of entrepreneurial orientation, market orientation, and entrepreneurial marketing on firm performance. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2024, 62, 2741–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Barrionuevo, M.M.; Molina, L.M.; García-Morales, V.J. Combined influence of absorptive capacity and corporate entrepreneurship on performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Batra, S. Absorptive capacity and small family firm performance: Exploring the mediation processes. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 22, 1201–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Perlines, F.; Blanco-González, A.; Miotto, G. Innovation in family businesses: Exploring the influence of entrepreneurial orientation and absorptive capacity on innovative capacity. J. Innov. Knowl. 2024, 9, 100600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maycotte, S.; Alvarez-Risco, A.; Garcia-Valenzuela, E.; Kuljis, M. Digital capabilities in emerging market firms: Construct development, scale validation, and implications for SMEs. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2025, 11, 100513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 23; Autio, E.; Nambisan, S.; Thomas, L.D.W.; Wright, M. Digital affordances, spatial affordances, and the genesis of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2018, 12, 72–95. [Google Scholar]

- Arcuri, M.C.; Russo, I.; Gandolfi, G. Productivity of innovation: The effect of innovativeness on start-up survival. J. Technol. Transfer 2025, 50, 1111–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrell, T.; Pihlajamaa, M.; Kanto, L.; Vom Brocke, J.; Uebernickel, F. The role of users and customers in digital innovation: Insights from B2B manufacturing firms. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Z.; Ren, X.G. The dynamic mechanism, operational path, and development countermeasures of digital economy innovation from a science and technology perspective. Guizhou Soc. Sci. 2020, 12, 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Jahanmir, S.F.; Cavadas, J. Factors affecting late adoption of digital innovations. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 88, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svahn, F.; Mathiassen, L.; Lindgren, R. Embracing digital innovation in incumbent firms. MIS Q. 2017, 41, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckertz, A.; Kollmann, T.; Krell, P.; Stöckmann, C. Understanding, differentiating, and measuring opportunity recognition and opportunity exploitation. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Su, Z.; Ahlstrom, D. Business model innovation: The effects of exploratory orientation, opportunity recognition, and entrepreneurial bricolage in an emerging economy. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2016, 33, 533–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zobel, A. Benefiting from open innovation: A multidimensional model of absorptive capacity. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2017, 34, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S.; Wright, M.; Feldman, M. The digital transformation of innovation and entrepreneurship: Progress, challenges, and key themes. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 103773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.K.; Niranjan, S.; Markin, E. Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: The mediating role of generative and acquisitive learning through customer relationships. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2020, 14, 1123–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallmuenzer, A.; Strobl, A.; Peters, M. Tweaking the entrepreneurial orientation–performance relationship in family firms: The effect of control mechanisms and family-related goals. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2018, 12, 855–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomako, S.; Danso, A.; Boso, N.; Narteh, B. Entrepreneurial alertness and new venture performance: Facilitating roles of networking capability. Int. Small Bus. J. 2018, 36, 453–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donbesuur, F.; Boso, N.; Hultman, M. The effect of entrepreneurial orientation on new venture performance: Contingency roles of entrepreneurial actions. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 118, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Dess, G.G. Linking two dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation to firm performance: The moderating role of environment and industry life cycle. J. Bus. Ventur. 2001, 16, 429–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Núñez, F.; Serrano-Malebrán, J. Enhancing Firm Performance: How Entrepreneurial Orientation and Information Technology Capability Interact. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M.; Clauss, T.; Issah, W.B. Entrepreneurial orientation and new venture performance in emerging markets: The mediating role of opportunity recognition. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2022, 16, 769–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Vonmetz, K.; Orlandi, L.B.; Zardini, A.; Rossignoli, C. Digital entrepreneurship: The role of entrepreneurial orientation and digitalization for disruptive innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 193, 122638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, B.; Wood, E. The importance of opportunity recognition behaviour and motivators of employees when engaged in corporate entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2015, 16, 980–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.R.; Lévesque, M.; Shepherd, D.A. When should entrepreneurs expedite or delay the exploitation of opportunities? J. Bus. Ventur. 2008, 23, 333–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillmann, J.; den Hartigh, R.J.R.; Kurpiers, C.M.; Raisch, F.K.; de Waard, D.; Cox, R.F.A. Keeping the driver in the loop in conditionally automated driving: A perception-action theory approach. Transp. Res. Part Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2021, 79, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldanha, T.J.V.; Mithas, S.; Krishnan, M.S. Leveraging customer involvement for fueling innovation. MIS Q. 2017, 41, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Hartley, J.L. Guanxi, IT systems, and innovation capability: The moderating role of proactiveness. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 90, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbraith, J. Designing Complex Organizations. Reading, Mass; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, A.; Ruiz, L.; Benitez, J.; Schuberth, F.; Reina, R. IT impact on open innovation performance: Insights from a large-scale empirical investigation. Decis. Support Syst. 2023, 175, 114025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; Free Press Sch: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 13, 319–340.

- Williamson, O.E. The economics of organization: The transaction cost approach. Am. J. Sociol. 1981, 87, 548–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo, G.A.; Paes, T.F.A.; da Costa, J.S.; e Silva, C.S.J.; de Castro Júnior, L.G.; Gomide, L.R.; Ferreira, L.O.G. Optimizing forest sector performance based on life cycle cost analysis and real options. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 988, 179675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, M.; Magableh, I.K.; Ta’Amnha, M.; Mahrouq, M.H.; Asif, M.U. Mediating role of social media adoption between the impact of entrepreneurial orientation and perceived benefits of social media on performance of Jordanian entrepreneurial firms. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2025, 12, 2592424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, M.; Asif, M.U. From bricolage to turbulence: How strategic flexibility shapes entrepreneurial firms’ performance. J. Bus. Strategy, 2025; 1–25, online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawes, J. Do data characteristics change according to the number of scale points used? An experiment using 5-point, 7-point, and 10-point scales. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2008, 50, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbreath, J.; Lucianetti, L.; Thomas, B.; Tisch, D. Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance in Italian firms: The moderating role of competitive strategy. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2020, 26, 629–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semrau, T.; Ambos, T.; Kraus, S. Entrepreneurial orientation and SME performance across societal cultures: An international study. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1928–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, W.; Chen, J. Research on the mechanism of the role of big data analytic capabilities on the growth performance of start-up enterprises: The mediating role of entrepreneurial opportunity recognition and exploitation. Systems 2023, 11, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Yao, Q.; Boadu, F.; Xie, Y. Distributed innovation, digital entrepreneurial opportunity, IT-enabled capabilities, and enterprises’ digital innovation performance: A moderated mediating model. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2023, 26, 1106–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics; Sage Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Civelek, M.E. Essentials of Structural Equation Modeling; University of Alaska Press: Fairbanks, AK, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Dess, G.G. Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 135–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftab, J.; Veneziani, M.; Sarwar, H.; Ishaq, M.I. Organizational Ambidexterity, Firm Performance, and Sustainable Development: The Mediating Role of Entrepreneurial Orientation in Pakistani SMEs. J. Clean Prod. 2022, 367, 132956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulka, B.M.; Ramli, A.; Mohamad, A. Entrepreneurial competencies, entrepreneurial orientation, entrepreneurial network, government business support, and SMEs performance. The Moderating Role of the External Environment. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2021, 28, 586–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, M.D.C.; Perin, M.G. Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: An updated meta-analysis. RAUSP Manag. J. 2020, 55, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S. Psychosocial models of the role of social support in the etiology of physical disease. Health Psychol. 1988, 7, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Dass, M.; Arnett, D.B.; Yu, X. Understanding firms’ relative strategic emphases: An entrepreneurial orientation explanation. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 84, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miocevic, D.; Morgan, R.E. Operational capabilities and entrepreneurial opportunities in emerging market firms: Explaining exporting SME growth. Int. Mark. Rev. 2018, 35, 320–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.; Coelho, A.; Moutinho, L. Dynamic capabilities, creativity and innovation capability and their impact on competitive advantage and firm performance: The moderating role of entrepreneurial orientation. Technovation 2020, 92, 102061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Idárraga, D.A.; Hurtado Gonzalez, J.M.; Cabello Medina, C. Factors affecting the effect of exploitation and exploration on performance: A meta-analysis. Bus. Res. Q. 2023, 25, 312–336. [Google Scholar]

- Mathafena, R.B. Entrepreneurial orientation, market orientation, and opportunity exploitation in driving business performance: Moderating effect of interfunctional coordination. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2023, 15, 538–565. [Google Scholar]

- Nambisan, S.; Zahra, S.A. The role of demand-side narratives in opportunity formation and enactment. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2016, 5, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.C.; Chan, W.C.; Hung, S.W.; Lin, D.Z. How entrepreneurs recognise entrepreneurial opportunity and its gaps: A cognitive theory perspective. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2020, 32, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Wright, M.; Abdelgawad, S.G. Contextualization and the advancement of entrepreneurship research. Int. Small Bus. J. 2014, 32, 479–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welter, F. Contextualizing entrepreneurship—Conceptual challenges and ways forward. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba-Sánchez, V.; Meseguer-Martínez, A.; Gouveia-Rodrigues, R.; Raposo, M.L. Effects of digital transformation on firm performance: The role of IT capabilities and digital orientation. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, S.A.; Busenitz, L.W. The entrepreneurship of resource-based theory. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 755–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, H. Digital capabilities and metaverse entrepreneurial performance: Role of entrepreneurial orientation. J. Innov. Knowl. 2024, 9, 100617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.S.; Meisner, K.; Krause, K.; Bzhalava, L.; Moog, P. Is digitalization a source of innovation? Exploring the role of digital diffusion in SME innovation performance. Small Bus. Econ. 2024, 62, 1469–1491. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Slimane, S.; Coeurderoy, R.; Mhenni, H. Digital transformation of small and medium enterprises: A system atic literature review and an integrative framework. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 2022, 52, 96–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isidoro, R.; Mammadov, H. Digital transformation of small and medium-sized enterprises as an innovation process: A holistic study of its determinants. J. Knowl. Econ. 2025, 16, 8496–8523. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.