Abstract

Urban metro systems face increasing pressure to reconcile passenger service quality with infrastructure maintenance demands during late-night operations. This study proposes a coordinated optimization framework that integrates train timetabling with a flexible and selective skip-stop strategy. A mixed-integer programming model is formulated to jointly maximize passenger Origin–Destination (OD) accessibility and extend available maintenance windows. To solve the high-dimensional and computationally intensive model efficiently, a hybrid GWO-CNN algorithm is designed, where a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)-based surrogate model replaces the time-consuming fitness evaluation process in the Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO). A real-world case study on the Beijing metro network demonstrates that the proposed method increases OD accessibility by 23.60% and extends maintenance window by 8310 s. Compared to the conventional GWO, the GWO-CNN algorithm achieves superior solution quality with a 98.4% reduction in computation time. Sensitivity analyses further reveal the trade-offs between skip-stop rates, objective weight settings, and optimization outcomes, offering practical insights for metro operators in tailoring late-night scheduling strategies to both passenger demand and maintenance priorities.

1. Introduction

Urban metro systems serve as the backbone of public transportation in many large- and medium-sized cities, providing high-capacity, reliable, and sustainable mobility. However, unlike road-based modes, metro operations are typically suspended during nighttime hours to allow for essential infrastructure maintenance, such as track inspections, signal system checks, and rolling stock servicing. These activities are vital to ensuring long-term operational safety and service quality. As a result, determining appropriate schedules for the final service period, especially the last trains on each line, is a critical yet challenging task for transit agencies [1].

Late-night timetables directly influence both passenger accessibility—particularly for those requiring inter-line transfers—and the length of non-operational windows available for maintenance. Striking a balance between these two conflicting objectives is essential but non-trivial. Although existing studies on the last train timetabling problem (LTTP) have explored coordination among multiple lines to improve late-night transferability, most approaches focus exclusively on adjusting train arrival and departure times to optimize connections [2]. These methods often fail to capture the broader network accessibility for passengers with multi-transfer trips.

More importantly, existing models generally overlook the potential of train stop pattern adjustment—such as skip-stop strategies—to enhance OD accessibility. Skip-stop operations, if properly coordinated, can significantly improve transfer feasibility by reducing travel times and enabling passengers to reach key transfer stations in time.

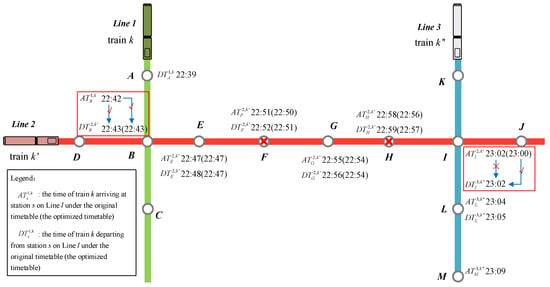

Figure 1 illustrates a simplified example of skip-stop operations in a three-line metro system. Suppose a passenger travels from station A on Line 1 to station M on Line 3, requiring transfers at stations B and I. Based on the initial timetable, the passenger fails to make the second transfer at station I and cannot reach station M. However, by applying a skip-stop strategy on Line 2—specifically skipping low-demand stations F and H—the passenger can arrive at station I by 23:00 and successfully catch the last train on Line 3. This example demonstrates that adjusting stopping schemes, in addition to timetables, can enhance network accessibility during the final service period.

Figure 1.

Example of skip-stop operation in a simplified metro network.

Despite this potential, skip-stop strategies are rarely considered in LTTP. Moreover, to ensure service coverage, skip-stop is typically avoided for last trains. This study addresses this limitation by introducing a selective skip-stop strategy—applied only to non-last trains—to preserve full coverage while enhancing OD accessibility.

In parallel, the critical role of the maintenance window has been largely neglected in existing LTTP research. As metro systems continue to expand and age, especially in legacy networks like Beijing and Shanghai, the conflict between increasing maintenance needs and limited non-operational hours has become increasingly prominent. Incorporating maintenance requirements into timetabling decisions is essential for sustaining long-term system performance and safety.

Similar concerns have been raised in recent studies on mainline railway operations, where researchers have begun integrating maintenance requirements into scheduling models [3,4]. These studies underscore the growing recognition of maintenance-aware operations in the railway domain. However, such considerations remain largely absent in urban metro scheduling, especially during the late-night period, where time windows are shorter and operational flexibility is limited.

To address these gaps, this paper proposes a coordinated optimization framework for late-night metro operations that simultaneously optimizes train timetables and stopping patterns across multiple metro lines during the final service period. The key contributions of this study are as follows:

- (1)

- We formulate a bi-objective mixed-integer programming (MIP) model that jointly maximizes passenger OD accessibility and extends maintenance windows. The model explicitly integrates a flexible skip-stop strategy—applied selectively to non-last trains—and captures realistic passenger transfer logic across multi-line trips, including route choices and timing feasibility constraints.

- (2)

- To efficiently solve the high-dimensional and computationally intensive MIP model, we design a hybrid metaheuristic algorithm that embeds a CNN-based surrogate model within the GWO framework. The surrogate model learns the objective landscape from a curated solution dataset and replaces time-consuming fitness evaluations in the GWO search process, achieving significant acceleration without sacrificing solution quality.

- (3)

- A comprehensive case study based on the Beijing metro network—covering 13 bidirectional lines, hundreds of stations, and thousands of OD pairs—demonstrates the effectiveness and scalability of the proposed approach. The results show substantial improvements in both OD accessibility and maintenance time, while the proposed GWO-CNN algorithm reduces computational time by 98.4% compared to conventional metaheuristics.

- (4)

- Sensitivity analysis reveals the trade-offs between skip-stop rates, objective weights, and optimization outcomes. The findings provide practical guidance for transit agencies to tailor late-night scheduling strategies based on line-specific characteristics and operational priorities.

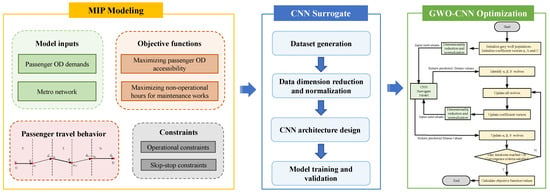

Figure 2 presents the overall methodological framework of this study. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the related literature on last train timetabling and skip-stop operations. Section 3 presents the model formulation. Section 4 introduces the GWO-CNN solution algorithm. Section 5 provides a detailed case study, and Section 6 concludes with practical implications and future research directions.

Figure 2.

Overall methodological framework diagram.

2. Literature Review

This section reviews prior research in two key areas relevant to this study: (1) last train timetabling in metro systems, (2) skip-stop strategies in metro operations. And then the integrated challenges and research gaps are summarized.

2.1. Last Train Timetabling in Metro Networks

The LTTP has been widely studied as a means to improve service levels in metro networks during late-night operations. Early research primarily focused on station-based transferability (ST-LTTP), aiming to synchronize arrival and departure times of last trains at transfer stations to improve passenger transfer success [5]. For example, Kang and Meng [6] formulated a mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) model to minimize the total transfer connection time for last train passengers. Similarly, Zhang et al. [7] introduced a period-based optimization model to reduce transfer failures during the final service period, while Wang et al. [8] proposed an integrated model to minimize energy consumption and enhance transfer accessibility.

However, ST-LTTP models emphasize point-to-point coordination and often neglect broader passenger reachability. In response, more recent research has shifted toward destination-based reachability (DR-LTTP), which considers the accessibility of OD pairs throughout the network [9,10]. For example, Yao et al. [11] introduced detour-routing strategies to increase destination coverage, while Chen et al. [12] developed a MIP model to maximize the weighted sum of accessible OD pairs on the urban rail networks. Other studies such as Wang et al. [13] and Li et al. [14] incorporated time-dependent assignment and elastic demand into DR-LTTP formulations. Huang et al. [15] and Ning et al. [16] made last train timetabling optimization considering multimodal coordination. Similarly, Ning et al. [17] accounted for heterogeneous passenger preferences and uncertainties in travel conditions and coordinated last train timetabling problem with ride-hailing service. Zhou et al. [18] developed a novel MILP model to optimize operation extension strategy for last train timetables and introduced Pareto method to balance social benefits and operation costs. Considering arrival uncertainties, Du et al. [19] proposed a robust method to solve the last train timetabling problem with service compatibility maximization.

Despite these advances, most LTTP models remain limited in two key ways: (1) they often assume full-stop train services and do not consider station-skipping mechanisms as a coordination tool. (2) They often disregard system maintenance requirements, treating service planning and infrastructure needs as separate problems.

2.2. Skip-Stop Strategies in Metro Operations

Skip-stop operation is a commonly used strategy to improve operational efficiency and reduce travel times. Two general categories exist:

A/B-type skip-stop, where trains are grouped into sets (e.g., A and B), each serving alternating stations [20]. This approach is easy to implement and ensures balanced service coverage. Recent studies have sought to improve transferability within A/B patterns [21] or optimize their deployment under demand heterogeneity [22].

Flexible skip-stop, which allows individual trains to skip stations dynamically based on demand profiles or operational objectives [23,24,25]. This approach offers greater adaptability and has been used in various contexts such as off-peak planning [26,27], event-related demand surges [28], and delay mitigation [29].

Despite these developments, most skip-stop research focuses on regular hours, and assumes adequate train frequency to compensate for skipped stops. Its use in late-night metro operations is rarely investigated. Moreover, skip-stop strategies are typically studied on individual lines, while their potential benefits within a multi-line, network-level coordination framework remain underexplored.

2.3. Research Gaps and Motivation

Table 1 summarizes representative studies on the LTTP. Compared with existing works, the proposed study distinguishes itself by integrating skip-stop decisions, explicitly considering infrastructure maintenance windows and incorporating CNN into algorithm design.

Table 1.

Comparison of representative LTTP studies.

Based on the literature above, several limitations can be identified: (1) neglect of maintenance windows: Most studies fail to consider infrastructure maintenance needs, despite their strong dependency on last train timings. (2) Underutilization of skip-stop strategies for nighttime operations: despite the proven effectiveness of skip-stop for metro operations, its potential to improve late-night OD accessibility has not been studied. Additionally, few works investigate skip-stop strategies within multi-line, network-scale settings, particularly under service coverage constraints. (3) Scalability and computational bottlenecks: the joint optimization of timetables, skip patterns, and passenger transfers results in a high-dimensional, nonlinear model. Existing algorithms, including exact solvers and basic heuristics, face significant challenges in solving such problems efficiently for large metro networks.

To bridge the above gaps, this paper proposes an integrated optimization framework for late-night metro operations, aiming to maximize OD accessibility while extending the non-operational window for maintenance. A flexible, train-specific skip-stop policy is introduced and applied only to non-last trains, preserving full station coverage by the last trains while enhancing transfer success and OD accessibility. To handle computational complexity, a hybrid GWO-CNN algorithm is developed and tested via real-world case study.

3. Model Formulation

In this section, we constructed a MIP model to optimize the train timetables and stopping plans collaboratively with the goals of improving passengers’ OD accessibility and extending non-operational hours for maintenance works.

3.1. Basic Assumptions

Prior to the model formulation, the following assumptions are established:

Assumption 1.

With the support of traveler information systems (e.g., mobile apps and platform screens), it is assumed that passengers have access to the train schedule as well as skip-stop information and make boarding decisions accordingly [31].

Assumption 2.

The passenger demands during routine late-night operations are less than the train capacity. It should be noted that non-recurrent high-demand scenarios triggered by special events (e.g., concerts, sports games) are beyond the scope of this study [5,6].

Assumption 3.

The transfer walking time is fixed and known for all passengers of each transfer relationship [30].

Assumption 4.

Overtaking is prohibited to all metro lines [31].

3.2. Notations

Sets:

: Set of metro lines, where up and down directions of one corridor are treated as separate lines, .

: Set of trains on line during the final service period, .

: Set of stations on line , .

G: Set of origin-destination pairs, , .

: Set of passengers with origin station and destination station .

: Subset of in which passengers’ entry times are within the same train headway.

: Set of feasible routes for passenger group .

: Set of transfer stations on route .

Parameters and Variables:

: Walking time from entry gate to platform at station on line .

: Transfer walking time at transfer station from line to line .

: Entry time for passenger p at his origin station o on line .

/: Maximum and minimum headways on line .

/: Maximum and minimum running time between stations and on line .

/: Maximum and minimum dwell time at stations on line .

: Minimum headway between a front train departing from and a rear train arriving at a station.

: Minimum headway between a front train departing from and a rear train passing through a station.

: Skip rate of a train on line .

/: Maximum and minimum skip rate.

/: Weight of optimization objectives.

Intermediate variables:

: Arrival time of train k at station on line .

: Departure time of train k from station on line .

: 1 if train on line is time-feasible for a transfer from feeder train k; 0 otherwise.

: 1 if train on the connecting line is selected at station of route for passenger group ; 0 otherwise.

: 1 if route is accessible for ; 0 otherwise.

: 1 if the metro network is accessible for during late night; 0 otherwise.

Decision variables:

: Running time of train k between stations and on line .

: Dwell time of train k at station on line .

: Headway between trains k and (k + 1) on line .

: 1 if train k stops at station on line ; 0 otherwise.

3.3. Constraints

3.3.1. Operational Constraints

Headway influences the efficiency and safety of train operations. Equation (1) defines the domain of decision variable .

Equation (2) limits train running times due to the traction characteristics and speed limitations.

Equation (3) sets constraints on train dwell times. It ensures that, on one hand, passengers have sufficient time to board, while on the other hand, it prevents excessively long stops that could compromise service quality.

The departure time of train on line from the first station is calculated by Equation (4).

For each line , Equations (5) and (6) formulate the relationships of train arrival and departure times with the time-related decision variables, respectively.

The tracking headway between two consecutive trains should satisfy Equation (7).

3.3.2. Skip-Stop Constraints

To reduce passengers’ waiting time on the platforms, it is stipulated that a train cannot skip two consecutive adjacent stations in Equation (8).

Equation (9) sets that adjacent trains are not allowed to skip a same station.

During train operations, some stations are mandatory for trains to stop, such as the first station, the last station and transfer stations, as constrained by Equation (10).

where represents the number of stations on line . represents the set of transfer stations on line .

Furthermore, Equation (11) stipulates that the last train on each line follow the all-stop strategy.

where represents the number of trains on line during the late-night operation period.

In order to maintain regular service quality, the skipping frequency per train is defined and limited by Equations (12) and (13).

3.4. Passenger Travel Behavior

Note that passengers generally prefer direct trips without interchanging between different trains. Given the longer headways at night and the desire to minimize travel time, passengers are assumed not to skip a feasible train to wait for a subsequent one. With these concerns and Assumption 1, it is assumed that passengers board the first direct trains during their trips.

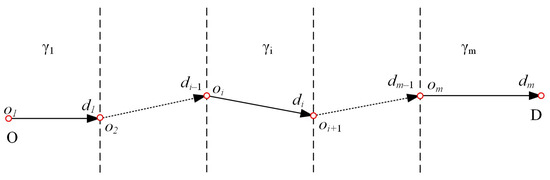

For passengers whose trips involve multiple transfers, their travel routes can be decomposed into several phases, as shown in Figure 3. For a travel route consisting of phases, the i-th phase is denoted as , indicating that passengers travel from original station to destination station during that phase. It is easy to deduce that for the i-th () phase, we have . During the first phase , passengers will take the first train that stops at station , as station is a transfer station that is mandatory to stop for all trains (see Equation (10)). Subsequently, during the transfer from to (), passengers can always take the first train since both stations and are transfer stations. In the final phase , passengers waiting at the last transfer station will board a train that stops at their destination station .

Figure 3.

Illustration of transfer phases on a route.

In summary, passengers may only experience increased waiting times during the first and last phases of their trips due to the skip-stop strategy. And passengers will wait at most for one additional train with Equation (9). Therefore, the increase in waiting time is limited to within a single headway. It should be noted that although the introduction of a skip-stop strategy may increase travel time for some passengers, it does not affect passengers’ accessibility since the last trains take the all-stop pattern.

3.5. Objective Functions

3.5.1. Maximize Passenger OD Accessibility

As noted before, passengers will take the first stopping train at their origin stations, so Equation (14) can determine the specific train k that passenger p can board at his origin station. On this basis, it can be deduced that passengers in who enter the origin station during the same train headway can board the same train k at the origin station. Thus, passengers in are further divided into some groups (denoted as ) based on their entry times.

In large-scale metro networks, multiple routes typically exist for a given OD pair. Passengers in share the same set of feasible routes, denoted as . Based on the first stopping train k that passenger group can board at the origin station (as determined by Equation (14)), passengers will continue to transfer along route . Each route consists of a series of transfer stations (denoted as ), and passengers will make a transfer from the feeder line l to the connecting line at .

To ensure feasibility and realism in train matching at transfer stations, passengers are assumed to always board the earliest available connecting train at station that departs after their arrival plus the necessary walking time . This rule ensures transfer success and enables further recursive transfer checks for downstream stations. First, a binary variable is introduced to indicate whether train on line is time-feasible for a transfer from feeder train k, as formulated in Equation (15). Then another binary variable is defined to indicate whether train is selected at transfer station . And Equations (16)–(18) guarantee that if a feasible connecting train exists, exactly the earliest train is chosen.

With the above constraints, the connecting train is uniquely determined and propagated forward for subsequent transfer stations along route , enabling recursive application of the transfer logic across the entire route. Then another binary variable is introduced to denote whether route r is accessible for passenger group , as defined in Equation (19):

where denotes the number of transfer stations in .

Finally, a binary variable is introduced to represent the OD accessibility of passenger group . As expressed in Equation (20), if there is at least one route with , it means that the metro network is accessible for passenger group and ; otherwise .

For ensuring better service quality, operators should try to maximize passenger OD accessibility during late-night operations. Therefore, the total number of accessible passengers is considered in objective function.

where denotes the number of passengers in passenger group .

3.5.2. Maximize Non-Operational Hours for Maintenance Works

As highlighted by Ma et al. [1], extending non-operational hours for maintenance work is essential for operation safety. Herein, is introduced to indicate the extended non-operational time for line l. It can be expressed as the difference between the arrival times of the last train () at the terminal station () before and after optimization, i.e., and .

For each line , Equation (23) ensures that the optimized timetables can reserve more non-operational hours for maintenance works.

Subsequently, the second objective function can be formulated by Equation (24).

3.5.3. Integrated Objective Function

Combining the two objectives and , a linear weighting approach is applied to convert the bi-objective issue to a single objective one:

This formulation allows the model to flexibly balance service quality and infrastructure availability. The weight coefficients and can be tuned by the operator according to different operational priorities or policy preferences. In case study, sensitivity analysis is conducted on to explore the trade-off frontier.

4. Solution Algorithm

Section 3 has formulated the MIP model for the coordinated optimization problem. Building upon this mathematical foundation, this section presents the solution methodology. Specifically, a hybrid metaheuristic approach integrating the GWO with a CNN-based surrogate is developed to solve the proposed model efficiently. The algorithm framework, detailed execution procedures, and the training strategy of the surrogate model are elaborated in the following subsections.

4.1. Algorithm Framework and Motivation

From a methodological perspective, the coordinated optimization model established in Section 3 is fundamentally an NP-hard combinatorial optimization problem characterized by high complexity and a non-continuous, non-convex solution space [31]. Specifically, the inherent nonlinearity in transfer logic and the binary combinatorics of skip-stop decisions create a search space that grows exponentially with the number of stations and trains. Consequently, it is difficult to solve by exact solvers such as CPLEX or Gurobi for large metro networks involving hundreds of trains and thousands of OD pairs.

To address this challenge, we design a hybrid metaheuristic framework based on the GWO, enhanced with a CNN-based surrogate model. GWO is a population-based optimization algorithm inspired by the social hierarchy and hunting behavior of grey wolves [34]. It balances exploration and exploitation through a simple parameter structure and has shown robust performance in solving high-dimensional, nonlinear optimization problems [35,36]. However, in our problem where the fitness function is expensive to evaluate, large populations and long iteration cycles become computationally costly. To mitigate this, a CNN-based surrogate model is introduced to approximate the objective function, replacing costly evaluations with rapid prediction. This significantly reduces the computational burden while pre-serving solution accuracy, enabling real-time assessment of large-scale populations for large-scale metro network.

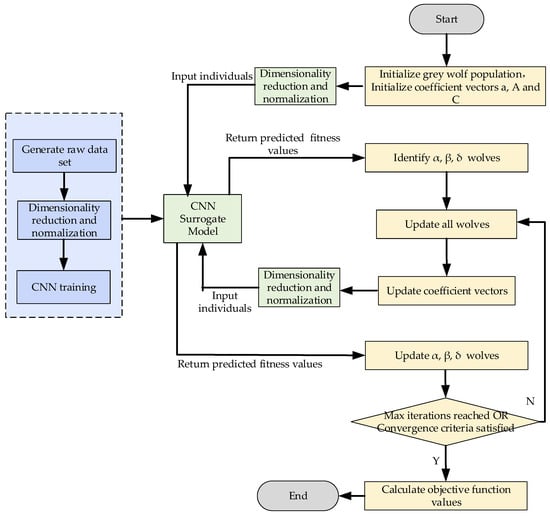

4.2. Algorithm Procedures of GWO-CNN

The GWO-CNN algorithm proceeds through the following steps:

- Initialize the population

A population of grey wolf individuals is generated under the operational constraints defined in the model. Each individual represents a feasible scheme, encompassing all decision variables. Coefficient vectors and are initialized to guide search directions, with parameter vectors updated via:

where and are random vectors uniformly distributed in [0, 1] to ensure search direction diversity. decreases linearly with iterations.

- 2.

- Data dimension reduction and normalization

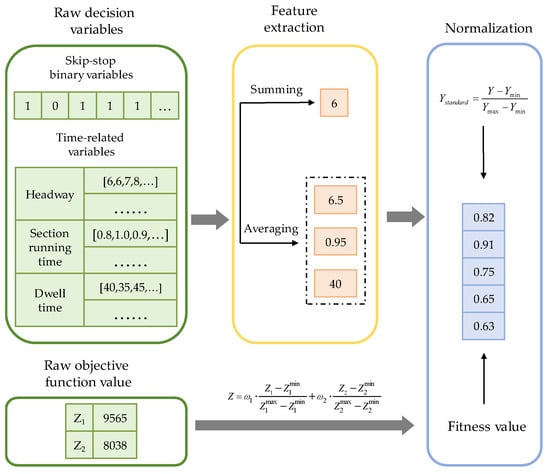

In the proposed model, the number of decision variables is directly related to the number of metro lines, train trips, and stations. In large-scale metro networks, the dimensionality of the decision space can grow rapidly, posing significant challenges for CNN-based surrogate models in learning complex mappings. To address this issue, a feature extraction and dimensionality reduction strategy is adopted, where multiple decision variables of the same type (e.g., binary stopping indicators, continuous time variables) are compressed into a single feature vector (see Figure 4). This reduces input complexity for the CNN model while preserving essential decision information. Normalization is then applied to both the features and objective values to eliminate scaling bias and ensure uniform learning behavior. Each feature is linearly transformed into the [0, 1] interval using Equation (28).

where and represent raw and normalized values, respectively. and denoting dataset extremes.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of data dimension reduction and normalization.

- 3.

- Fitness evaluation

Instead of computing the exact objective value for each solution, the trained CNN surrogate model estimates the fitness of each individual. The population is then ranked based on estimated fitness, and the top three individuals are designated as the best solution (, alpha wolf), the second-best solution (, beta wolf), the third-best solution (, delta wolf). The remaining wolves are classified as general individuals (, omega wolves).

- 4.

- Position update

Each grey wolf updates its position according to the cooperative hunting strategy defined by the positions of the top three leaders. The update Equations (29)–(35) compute distances to elite individuals and synthesize new candidate positions through weighted aggregation. The prey is represented by the current best solution, guiding the population toward promising regions in the search space.

where denotes the current iteration index. represents the current individual under evaluation. The three distance vectors , and measure the spatial distances between the current individual and the elite solutions (, and ), respectively. Each distance vector generates a candidate position (, and ) through the cooperative hunting mechanism. The final updated position is then determined by Equation (35), which implements the weighted aggregation of these candidate positions.

- 5.

- Coefficient adaptation

The coefficient vectors, introduced in Step (1), are dynamically adjusted based on the iteration progress. The initial coefficient prioritizes global exploration and is linearly decreased to zero during iterations according to Equation (36). As reduces, coefficient vectors and are updated via Equations (26) and (27) to shift the search strategy from global exploration to local exploitation, enabling progressive convergence toward the optimal solution.

where represents the maximum iterations.

- 6.

- Iterative control

The algorithm iteratively executes Steps 3–5 until the maximum number of iterations is reached or the fitness convergence criterion is satisfied.

The workflow of the proposed GWO-CNN algorithm is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Flowchart of the GWO-CNN algorithm.

4.3. CNN Training

- Hierarchical architecture design

The rationale for selecting a one-dimensional CNN over traditional Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) or Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) lies in the inherent structure of the decision variables. The inputs, such as skip-stop patterns and headway sequences, exhibit strong sequential characteristics and local correlations (e.g., the skipping decision of a station is often correlated with its adjacent stations). The one-dimensional CNN architecture, with its sliding convolutional kernels, efficiently captures these local dependencies while maintaining a significantly lower parameter count compared to fully connected networks. This lightweight design ensures rapid inference speed, which is critical for the surrogate model embedded within the iterative GWO search process.

Based on this design philosophy, the CNN model is constructed to learn the complex, nonlinear mappings between decision features and fitness values. As depicted in Figure 6, the architecture comprises multiple hierarchical layers: an input layer receiving the normalized features, convolutional layers with ReLU activation for feature extraction, pooling layers for dimensionality reduction, and fully connected layers for global pattern recognition [37,38].

Figure 6.

Forward propagation model architecture diagram.

- 2.

- Data preparation and preprocessingTo construct a high-quality dataset that enables the CNN surrogate to learn the global fitness landscape, a rigorous data generation and sampling strategy is implemented based on the model constraints defined in Section 3.

- (1)

- Data generation: The GWO algorithm is executed for 20 independent runs with different random seeds to ensure diversity in search trajectories. In each run, a population of 100 individuals evolves over 100 iterations, generating a total pool of 200,000 raw candidate solutions. All generated individuals are strictly constrained by the operational constraints to ensure physical feasibility.

- (2)

- Sampling strategy: To ensure the dataset covers a broad range of scenarios from suboptimal to near-optimal, we adopt a stratified sampling strategy based on evolutionary stages: 30% of the samples are selected from early iterations (Iterations 1–30). These solutions, initialized randomly, exhibit high diversity and lower fitness, helping the CNN learn the global features of the solution space. 40% of the samples are drawn from intermediate iterations (Iterations 31–70), capturing the gradient information as the population moves toward promising regions. 30% of the samples are taken from the final stages (Iterations 71–100), representing high-quality, and near-optimal solutions essential for precision.

- (3)

- Data preprocessing: From the stratified pool, a final dataset of 10,000 distinct samples is constructed. To improve model robustness, duplicate or highly similar solutions are filtered out to prevent data leakage or overfitting. Finally, all input features are dimensionally compressed and normalized according to the method in Figure 3. The corresponding objective values are normalized and aggregated into a unified composite score used as training labels.

- 3.

- Training results and validation

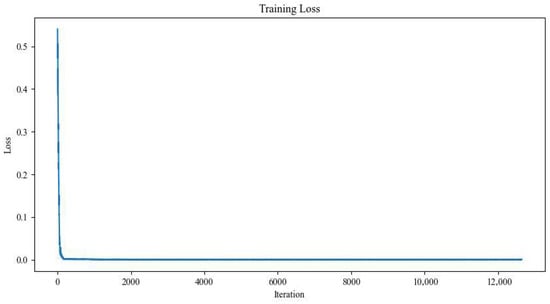

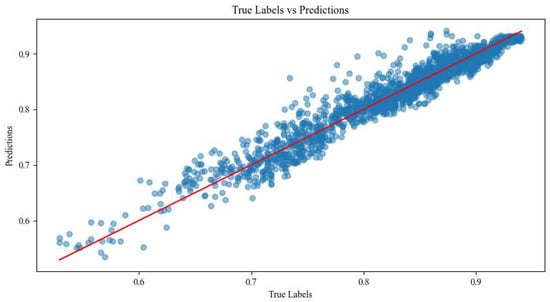

The preprocessed dataset is randomly partitioned into training (80%) and testing (20%) subsets using stratified sampling to maintain distribution consistency. As shown in Figure 7, the training loss decreased from an initial value of 0.0016 to a converged value of 0.0004, indicating sufficient learning convergence without significant overfitting. The predictive performance on the test set is visualized in the parity plot in Figure 8, where the high coefficient of determination ( = 0.981) confirms a strong correlation between the predicted and actual fitness values.

Figure 7.

Training loss curve.

Figure 8.

True vs. predicted values scatter plot.

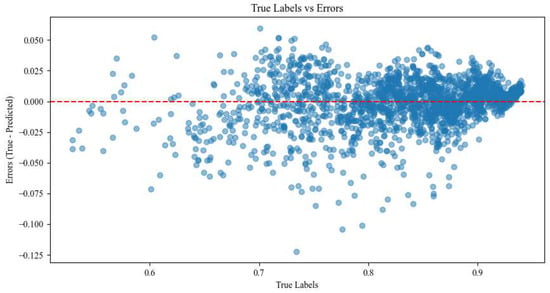

To comprehensively evaluate the surrogate’s reliability and robustness, we further employ 5-fold cross-validation. The dataset is partitioned into five subsets, and the model is trained and validated five times. The results demonstrate high stability, with an average Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of 0.015 and a Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) of 1.92%. Furthermore, the prediction error distribution analysis (visualized in Figure 9) reveals that the residuals are centered on the zero line, indicating no significant systematic bias. Approximately 95% of the residuals are concentrated within the range of [−0.05, 0.05], indicating no significant bias. Crucially, the error distribution exhibits a desirable feature where prediction accuracy improves as the fitness value increases. These consistent metrics confirm that the CNN surrogate achieves high prediction accuracy and generalization capability, making it a reliable substitute for the fitness function in the optimization task.

Figure 9.

Prediction error distribution.

4.4. Numerical Experiment on a Small-Scale Network

Before applying the algorithm to the large-scale metro network, we first validate the solution quality of the proposed GWO-CNN approach on a small-scale instance where the global optimal solution can be obtained by exact solvers (Gurobi 12.0.1). Figure 10 shows the map of the sample network consisting of 3 bi-directional lines and 3 transfer stations.

Figure 10.

Map of small-scale sample network.

The comparison results are presented in Table 2. The Gurobi, utilizing the Branch-and-Cut algorithm, obtained the global optimal fitness value of 0.6173 for this small-scale instance. In comparison, the proposed GWO-CNN algorithm achieved a fitness value of 0.6017. The optimality gap is 2.51% indicating that the solution found by GWO-CNN is extremely close to the theoretical global optimum. This firmly validates the accuracy and reliability of the proposed algorithm.

Table 2.

Comparison of algorithm optimization results for the small-scale network in Figure 10.

In terms of computation time, GWO-CNN demonstrated significant superiority. It completed the optimization in 45 s, which is not only faster than Gurobi but represents a dramatic 97.5% reduction compared to the traditional GWO. It is worth noting that while Gurobi is efficient for this small-scale problem, its computational time typically grows exponentially with network size. The fact that GWO-CNN is already faster than the exact solver on a small scale, combined with its massive speedup over the baseline heuristic, highlights its potential for scalability to large-scale networks where exact solvers become intractable.

5. Case Study

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed optimization model and solution algorithm, we conduct a case study using a real-world metro network. This section presents the case setup, performance evaluation, and sensitivity analysis of key parameters.

5.1. Case Setup

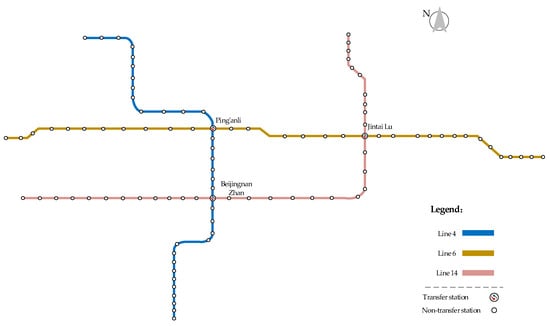

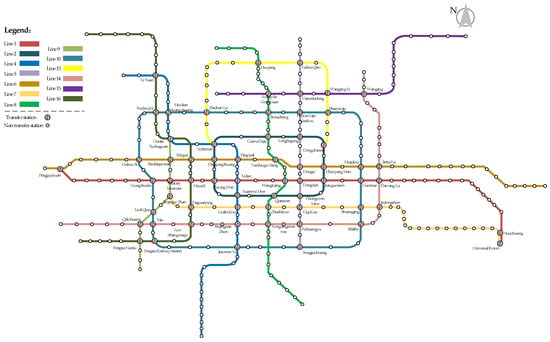

As illustrated in Figure 11, the studied network, a sub-network of Beijing metro, comprises 13 bidirectional metro lines with over 300 stations, including 63 transfer stations. The studied time period is from 22:30 until system closure. The original timetable of the last trains is the actual timetable collected from the official website of Beijing subway corporation. Some parameters in the model and algorithm are set as detailed in Table 3.

Figure 11.

Map of sub-network in Beijing Metro.

Table 3.

Parameter settings in the model and algorithm.

5.2. Results Analysis

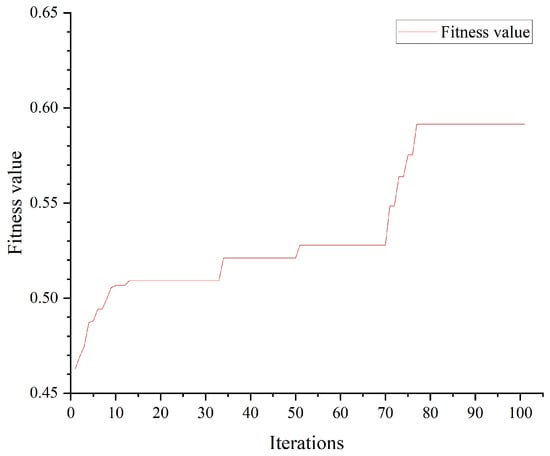

The proposed algorithm is implemented in Python 3.11.5 and executed on a HP (Beijing, China) desktop equipped with 4.2GHz 13th Gen Intel® Core™ i5-13400 processor and 32GB RAM. After 100 iterations, the optimization process converged, achieving a final fitness value of 0.5914. The convergence curve is illustrated in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Convergence curve of GWO-CNN algorithm.

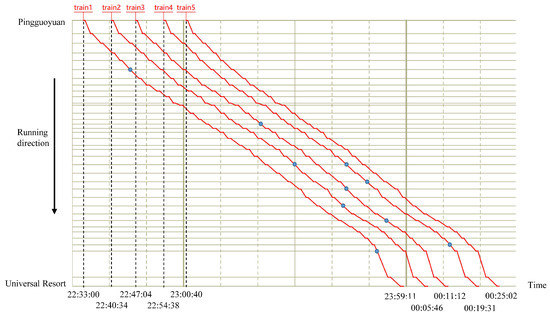

Except for the last train on each line, the skipping rate of other trains is controlled within the range of (0.10, 0.15], skipping 2–3 stations on average. Figure 13 illustrates the spatial distribution of skipped stations for down direction of Line 1. It involves 36 stations, including 13 non-skipping stations (i.e., transfer stations and terminals). A total of five trains are scheduled on this line during the study period. In the figure, the blue dots represent the stations skipped by each train. It can be observed that the skip-stop patterns vary across trains and are primarily concentrated in the downstream segment of the line.

Figure 13.

Train diagram of down direction of Beijing Metro Line 1 in the study period.

The optimization results are presented in Table 4. Compared with the original timetable, the proposed GWO-CNN algorithm achieves an improvement of 0.4869 in the fitness value Z. Specifically, the number of reachable OD pairs increases to 9944, representing a 23.60% improvement over the baseline. Furthermore, the maintenance time window is extended by 8310 s, with an average extension of approximately 5.53 min per line.

Table 4.

Comparison of algorithm optimization results for the large-scale network in Figure 11.

To further assess the effectiveness of the proposed GWO-CNN algorithm, a comparative experiment is conducted against the conventional GWO approach under identical computational settings. As shown in Table 4, the GWO requires approximately 4.0 h to complete 100 iterations, whereas the GWO-CNN accomplishes the same in merely 3 min, demonstrating a remarkable 98.4% reduction in computation time. This substantial improvement in computational efficiency is attributed to the CNN-assisted fitness evaluation mechanism. Beyond computational speed, the GWO-CNN algorithm also shows superior optimization performance. Compared to the GWO, the final solution accommodates 379 more accessible passengers and achieves a 3.50% increase in extended maintenance time. Overall, these results clearly demonstrate the effectiveness and efficiency of the GWO-CNN hybrid approach in generating high-quality solutions with significantly reduced computational time, highlighting its practical value for large-scale timetable optimization.

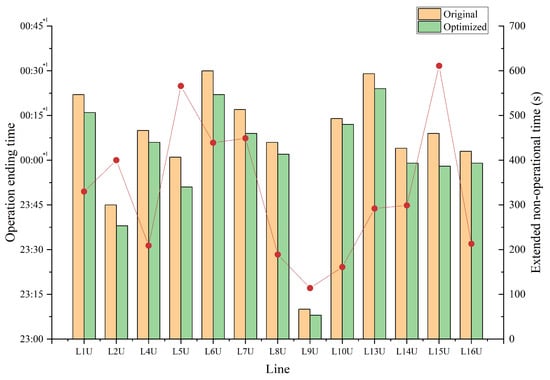

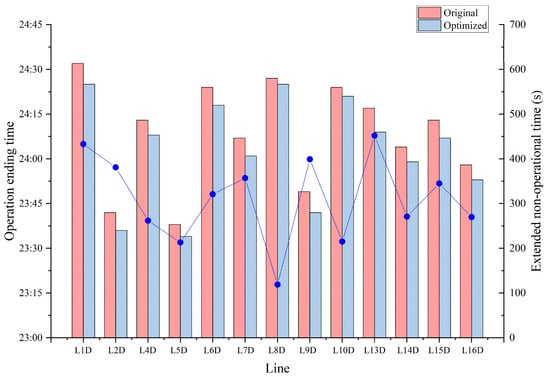

Table 4 shows that across the entire network, the cumulative extension of non-operational time exceeds 2.3 h, which can be redistributed among maintenance teams to reduce nighttime staffing pressure and improve operational safety. Moreover, the optimization results lead to a system-wide advancement in operation ending times, as illustrated in Figure 14 and Figure 15. The results reveal that 11 lines now complete operations before midnight compared to 6 originally, thus easing coordination pressure and increasing the overlap of available maintenance windows across lines. These improvements offer tangible benefits for infrastructure health and long-term sustainability, despite their seemingly small numerical values.

Figure 14.

Comparison of operation ending time for up-direction lines.

Figure 15.

Comparison of operation ending time for down-direction lines.

Additionally, the model’s flexibility allows for further customization based on operational priorities. For example, if the constraint in Equation (23)—which currently enforces non-negative extensions to each line’s maintenance window—is tightened (e.g., by setting a positive minimum threshold for lines with more urgent maintenance needs), the model can still accommodate this adjustment and produce targeted results accordingly. This adaptability enhances the model’s applicability to real-world metro systems facing diverse infrastructure and scheduling constraints.

5.3. Sensitivity Analysis

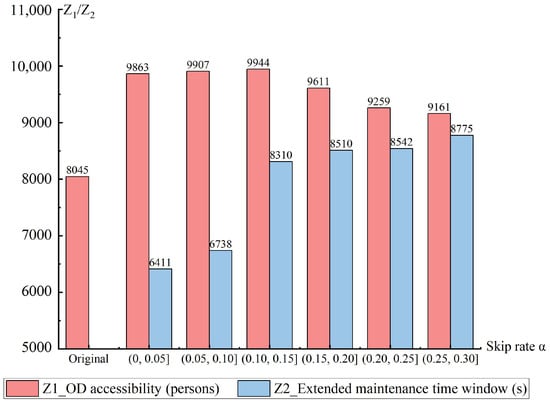

5.3.1. Skip Rates

To evaluate the impact of skip-stop rates on optimization performance, we conduct sensitivity analysis on skip rate ranging from (0, 0.05] to (0.25, 0.30], building upon the base scenario of (0.10, 0.15]. The results are depicted in Figure 16.

Figure 16.

Results of different skip rates.

As the skip-stop rate increases from (0, 0.05] to (0.25, 0.30], passenger accessibility initially shows a slight increase, followed by a gradual decline. This indicates that moderate skip-stopping can enhance network accessibility to a certain extent, whereas excessive skip-stopping leads to a reduction in the number of accessible passengers. Among all scenarios, the base scenario with a skip-stop rate of (0.10, 0.15] yields the highest accessibility. When the rate exceeds 0.15, accessibility declines significantly, suggesting that = 0.15 serves as a critical threshold and could be considered the upper limit for skip-stopping.

In contrast to the trend observed in accessibility, the extension in maintenance time increases steadily with higher skip-stop rates. Notably, the largest improvement occurs when increases from (0.05, 0.10] to (0.10, 0.15]. Overall, in the context of this case study, setting the skip-stop rate to (0.10, 0.15] appears to be a reasonable and effective choice. In practice, sensitivity analysis can be employed to determine an appropriate range for skip-stop rate settings.

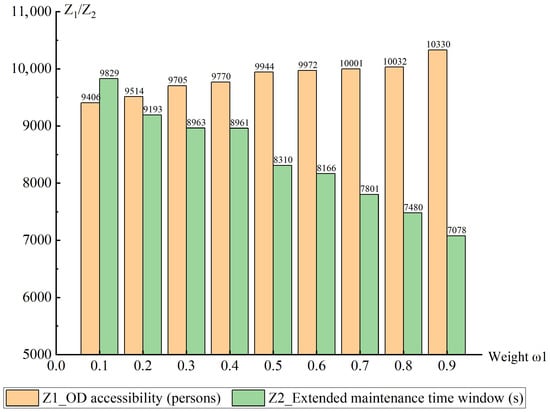

5.3.2. Weight of Objective Functions

In the baseline scenario, equal weights are assigned to the two objective functions. This section conducts a sensitivity analysis with respect to the weight coefficients. In the comparative experiments, is varied from 0.1 to 0.9, and the results are presented in Figure 17.

Figure 17.

Results of different objective weights.

As shown, increasing from 0.1 to 0.9 leads to a steady rise in OD accessibility, while the extended non-operational time for maintenance work exhibits an opposite and decreasing trend. This reveals a clear negative correlation between the two objectives. Specifically, as increases, the growth in OD accessibility is relatively moderate, whereas the reduction in advanced closure time is more pronounced. When increases from 0.1 to 0.5, OD accessibility improves by 5.72%, while the extended maintenance time reduces by 15.45%. As increases from 0.5 to 0.8, OD accessibility only increases by 0.88%, but the extended maintenance time decreases significantly by 9.99%. Notably, when increases from 0.8 to 0.9, OD accessibility sees a larger rise, increasing by 298 passengers, while extended maintenance time reduces by 5.38%.

This inherent trade-off characteristic necessitates the implementation of differentiated optimization strategies based on line characteristics and operational priorities to achieve coordinated optimization of both objectives. For lines serving commercial or residential areas, priority should be given to the accessibility objective by assigning higher weight coefficients to while relaxing closure time constraints. Conversely, aging trunk lines require greater emphasis on maintenance windows through earlier closures, with basic accessibility maintained by coordinated detour routing or supplementary bus bridging services during maintenance periods.

6. Conclusions

This study proposes a coordinated optimization framework for late-night train operations in urban metro systems, aiming to enhance OD accessibility while extending the available maintenance window. A bi-objective mixed-integer programming model is developed to jointly determine the timetables and stop patterns of multiple trains across interconnected lines. To efficiently solve the large-scale, nonlinear, and route-dependent model, we design a GWO-CNN hybrid algorithm that leverages the global search capability of the Grey Wolf Optimizer and the predictive power of a convolutional neural network surrogate model. This framework significantly reduces computational complexity and enables rapid timetable evaluations under multiple objectives.

A comprehensive case study on the Beijing metro network demonstrates the practical effectiveness of the proposed method, yielding several noteworthy findings: (1) compared with the original timetable, the GWO-CNN algorithm increases the number of reachable OD pairs by 23.60% and advances the system closure time by 8310 s. Compared to the traditional GWO, it accommodates 379 additional accessible passengers, shortens the closure time by 3.50%, and reduces computation time by 98.4%, showcasing clear advantages in both optimization quality and computational efficiency. (2) Sensitivity analysis on skip rate reveals that moderate levels of skipping improve network accessibility by enabling more effective transfer opportunities. However, excessive skipping begins to reduce the number of accessible passengers. In contrast, the extension of closure time continues to improve steadily with higher skip-stop rates, suggesting a trade-off between service quality and maintenance efficiency. (3) Sensitivity analysis on the objective weight confirms a clear negative correlation between OD accessibility and extended maintenance windows. It highlights the need for differentiated strategies: passenger-centric lines may prioritize accessibility, while infrastructure-sensitive lines should favor extended maintenance windows.

Furthermore, the study suggests future research directions. First, the current model assumes deterministic passenger demand and train operations. In practice, uncertainties such as passenger arrival variability and train delays can significantly impact performance. Incorporating stochastic or robust optimization techniques could enhance model resilience under real-world conditions. Second, energy efficiency is not explicitly considered in the current model. Incorporating energy-saving objectives—such as minimizing traction energy or maximizing the use of regenerative braking—could further enhance the sustainability of late-night operations. Third, extending the model to incorporate multimodal connections, such as feeder buses and ride-hailing service, could further enhance system-wide accessibility and operational flexibility during the late-night period.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.W., X.L., Z.H. and H.P.; methodology, Z.W., X.L., Z.H. and H.P.; software, Z.W., S.H., Z.C. and X.L.; validation, X.L. and H.P.; formal analysis, X.L. and Z.H.; investigation, Z.W. and X.L.; resources, X.L. and H.P.; data curation, Z.W. and X.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.W., S.H., Z.C., X.L., Z.H. and H.P.; visualization, Z.W., S.H. and Z.C.; supervision, X.L. and H.P.; project administration, X.L. and H.P.; funding acquisition, X.L. and H.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (No. LY21E080008), the Natural Science Foundation of Ningbo (No. 202003N4146), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 72371154).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ma, Y.; Wang, H.; Yang, H. Timetable scheduling considering non-traffic hour maintenance window. In Proceedings of the Australasian Transport Research Forum, Melbourne, Australia, 27–29 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, W.; Li, H.; Xiao, N.; Yang, H.; Jiang, Z.; Buhigiro, N. Modeling and solving the last-shift period train scheduling problem in subway networks. Physica A 2021, 569, 125775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buurman, B.; Gkiotsalitis, K.; Berkum, E. Railway maintenance reservation scheduling considering detouring delays and maintenance demand. J. Rail Transp. Plan. Manag. 2023, 25, 100359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Wang, R.; Zhang, C.; Yin, J.; Ma, L.; Yang, L. Optimization of train schedule with uncertain maintenance plans in high-speed railways: A stochastic programming approach. Omega 2024, 124, 102999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Wu, J.; Sun, H.; Zhu, X.; Gao, Z. A case study on the coordination of last trains for the Beijing subway network. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2015, 72, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Meng, Q. Two-phase decomposition method for the last train departure time choice in subway networks. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2017, 104, 568–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, X.; Yan, T.; Lu, L.; Shi, Y. Last train timetabling optimization for minimizing passenger transfer failures in urban rail transit networks: A time-period based approach. Physica A 2022, 605, 128071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Meng, X.; Guo, M.; Li, H.; Hou, Z. An integrated energy-efficient and transfer-accessible model for the last train timetabling problem. Physica A 2022, 588, 126575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, H.; Yan, X. Last train scheduling for maximizing passenger destination reachability in urban rail transit networks. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2019, 129, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Di, Z.; Dessouky, M.; Gao, Z.; Shi, J. Collaborative optimization of last-train timetables with accessibility: A space-time network design based approach. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2020, 114, 572–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Zhu, X.; Shi, H.; Shang, P. Last train timetable optimization considering detour routing strategy in an urban rail transit network. Meas. Control 2019, 52, 1461–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Mao, B.; Bai, Y.; Ho, T.; Li, Z. Timetable synchronization of last trains for urban rail networks with maximum accessibility. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2019, 99, 110–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Xu, R.; Song, X.; Wang, P. Collaborative optimization of last-train timetables for metro network to increase service time for passengers. Comput. Oper. Res. 2023, 151, 106091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Peng, R.; Luo, Q. Last train schedule optimization for metro systems considering minimum adjustment cost under elastic passenger demand. Transp. Lett. 2025, 17, 1302–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Wu, J.; Liao, F.; Sun, H.; He, F.; Gao, Z. Incorporating multimodal coordination into timetabling optimization of the last trains in an urban railway network. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2021, 124, 102889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, J.; Peng, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Xing, X.; Nielsen, O. Bi-objective optimization of last-train timetabling with multimodal coordination in urban transportation. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2023, 154, 104260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, J.; Xing, X.; Wang, Y.; Yao, Y.; Kang, L.; Peng, Q. Coordinating last-train timetabling with app based ride-hailing service under uncertainty. Physica A 2024, 636, 129537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Wang, W.; Wang, F.; Xu, R. Operation extension strategy on last train timetables in urban rail transit network: A Pareto optimality-based approach. Transportation 2025, 52, 2007–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Ye, X.; Chen, D.; Ni, S. Last-train timetable synchronization for service compatibility maximization in urban rail transit networks with arrival uncertainties. Appl. Math. Model. 2025, 138, 115768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, M.; Abdelhafiez, E.; Shalaby, M. Maximizing number of direct trips for a skip-stop policy in metro systems. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 137, 106091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Choi, J. An optimization method to design a skip–stop pattern for renovating operation schemes in urban railways. Transp. Lett. 2022, 14, 909–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Gu, W.; Cassidy, M.; Fan, W. Planning skip-stop transit service under heterogeneous demands. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2021, 150, 503–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limsawasd, C.; Athigakunagorn, N.; Khathawatcharakun, P.; Boonmee, A. Skip-stop strategy patterns optimization to enhance mass transit operation under physical distancing policy due to COVID-19 pandemic outbreak. Transp. Policy 2022, 126, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Wu, J.; Yang, X.; Liao, F.; Li, D.; Wei, Y. Analysis of energy consumption reduction in metro systems using rolling stop-skipping patterns. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 127, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrando, R.; Farhi, N.; Christoforou, Z.; Urban, A. A mathematical model for a two-service skip-stop policy with demand-dependent dwell times. J. Rail Transp. Plan. Manag. 2024, 31, 100461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Liu, X.; Chen, M. Optimal train scheduling under a flexible skip-stop scheme for urban rail transit based on smartcard data. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Rail Transportation (ICIRT), Birmingham, UK, 23–25 August 2016; pp. 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zheng, C.; Shen, J.; Chen, Z.; Ma, J.; Shen, Y. Metro stop-skipping rescheduling optimization considering passenger waiting time fairness. Transp. Lett. 2024, 16, 1115–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Sun, H.; Kang, L.; Lv, Y.; Yang, X.; Wei, Y. An integrated optimization approach for passenger flow control strategy and metro train scheduling considering skip-stop patterns in special situations. Appl. Math. Model. 2023, 118, 412–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Yu, J.; Liu, Z.; Chen, W. Optimal train skip-stop operation at urban rail transit transfer stations for nonrecurrent extreme passenger flow mitigation. J. Transp. Eng. Part A Syst. 2020, 146, 04020062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Wu, J.; Sun, H.; Yang, X.; Jin, J.; Wang, D. Scheduling synchronization in urban rail transit networks: Trade-offs between transfer passenger and last train operation. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2020, 138, 463–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Sun, H.; Wu, J.; Gao, Z. Last train station-skipping, transfer-accessible and energy-efficient scheduling in subway networks. Energy 2020, 206, 118127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, J.; Peng, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Nielsen, O. A bi-objective optimization model for the last train timetabling problem. J. Rail Transp. Plan. Manag. 2022, 23, 100333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Gao, Y.; Yang, L.; Cui, L. Timetable synchronization of the last several trains at night in an urban rail transit network. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2024, 313, 494–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Mirjalili, S.; Lewis, A. Grey Wolf Optimizer. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2014, 69, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faris, H.; Aljarah, I.; Al-Betar, M.; Mirjalili, S. Grey wolf optimizer: A review of recent variants and applications. Neural Comput. Appl. 2018, 30, 413–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, E.; Denizhan, B. Comparative study of application of production sequencing and scheduling problems in tire mixing operations with ADAM, Grey Wolf Optimizer, and Genetic Algorithm. Systems 2025, 13, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Yin, Z.; Jia, Y.; Xie, Y. Passenger flow estimation based on convolutional neural network in public transportation system. Knowl.-Based. Syst. 2017, 123, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arani, M.; Momenitabar, M.; Priyanka, T.J. Unrelated parallel machine scheduling problem considering job splitting, inventories, shortage, and resource: A meta-heuristic approach. Systems 2024, 12, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.