Abstract

The rising presence of artificial intelligence (AI) across European industries is gradually reshaping how societies manage resources, reduce waste, and pursue long-term sustainability. While researchers widely acknowledge the economic and social implications of AI, they have not yet sufficiently explored its contribution to advancing a circular economy. This study examines how varying levels of AI adoption across EU Member States relate to material footprint, resource productivity, waste generation, and recycling performance. The analysis draws on harmonized Eurostat data from 2023, the most recent year for which complete and comparable indicators are available, enabling a coherent cross-sectional perspective that reflects the period when AI began to exert a more visible influence on economic and environmental practices. By combining measures of AI uptake with key circular economy indicators and applying factor analysis, neural network modelling, and cluster analysis, the study identifies underlying patterns and country-specific profiles. The results suggest that higher AI adoption is often associated with greater resource productivity and more efficient material use. However, its effects on waste generation and recycling remain uneven across Member States. These findings indicate that AI can support circular economy objectives when embedded in coordinated national strategies and supported by robust institutional frameworks. Strengthening the alignment between digital innovation and sustainability goals may help build more resilient, resource-efficient economies across Europe.

1. Introduction

The accelerating interplay between digital transformation and sustainability is reshaping how contemporary economies understand and manage material resources. Over the past decade, the circular economy (CE) has emerged as a central policy framework aimed at reconciling economic development with environmental constraints, promoting the reuse, regeneration, and efficient use of materials as an alternative to the traditional linear model [1,2]. Within this evolving landscape, artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly recognized not only as a technological tool but also as a transformative force capable of shaping production systems, consumption dynamics, and governance mechanisms [3,4]. By enabling predictive analytics, real-time monitoring, and enhanced decision-making capabilities, AI has the potential to reduce material footprints, improve resource productivity, and optimize waste management processes across multiple sectors [5,6].

In the European Union (EU), the integration of AI into sustainability strategies is taking place within a complex policy environment shaped by initiatives such as the European Green Deal and the Circular Economy Action Plan. These frameworks position digital innovation as an essential lever for achieving climate neutrality and resource efficiency. However, the pace and depth of AI adoption vary considerably across Member States due to differences in technological capacity, economic structure, and institutional readiness [7,8]. Emerging evidence suggests that while technologically advanced countries are increasingly able to align AI deployment with circular practices, states with more limited digital infrastructures may struggle to capture similar benefits, potentially widening existing sustainability gaps [9,10,11]. This divergence underscores the importance of understanding not only the opportunities but also the uneven distribution of advantages associated with AI-driven circularity.

This observation provides a natural transition to the gaps that persist in the current body of research. Although prior studies have explored AI applications in specific domains—including waste management [12], water systems [13], and manufacturing [14], as well as the role of blockchain in improving transparency and traceability [15,16]- these contributions primarily focus on isolated technologies or sectoral contexts. As a result, they provide fragmented insights that do not fully capture how varying degrees of AI adoption shape macro-level outcomes in the circular economy. What remains insufficiently examined is the broader relationship between AI integration and national-level indicators of material use, recycling performance, and resource productivity across the EU.

The present study seeks to address this gap by employing a comprehensive and systematic analytical approach. Using harmonized European indicators, the research combines factor analysis, a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) neural network, and hierarchical cluster analysis to examine AI adoption and circular performance as interconnected components of Europe’s sustainability transition. This integrated methodology enables the exploration of latent structures, nonlinear dynamics, and cross-country similarities that would otherwise remain hidden in more traditional analytical designs. The study’s contribution, therefore, lies not only in its empirical findings but also in the methodological framework through which the results are generated, offering a more holistic understanding of how AI shapes the circular economy at the European level.

The remainder of the paper is organized to situate these contributions within the broader academic debate. The following section reviews the theoretical and empirical foundations linking AI and the circular economy, followed by a detailed description of the data and methods used in the analysis. Subsequent sections present the results and discuss their implications for Europe’s sustainability trajectory, concluding with reflections on policy relevance and directions for future research.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Artificial Intelligence as a Catalyst for Circular Economy Performance in the European Union

In recent decades, the shift toward a sustainable economic model has become a strategic priority across Europe, and the circular economy has emerged as a structural solution to the resource crisis and to decarbonization. Unlike the traditional linear model based on the “production–consumption–waste” paradigm, the circular economy envisions a regenerative system in which materials and energy circulate continuously, reducing environmental impact while encouraging innovation [1,2,17,18,19]. According to Sánchez-García et al. [3], this change signifies not just an economic shift but a profound transformation in how European societies view the relationship among resources, technology, and sustainability.

Within this evolving ecosystem, AI plays a vital role in promoting circular performance by providing predictive and decision-making tools that support innovative resource management and help decrease the material footprint [20]. Machine learning models analyze real-time production and consumption data, forecast demand, and optimize processes to prevent overproduction and waste [5,14]. Additionally, neural network algorithms identify inefficiencies along value chains, enabling companies to optimize material flows and prolong product lifecycles [21].

This convergence between AI and the circular economy redefines the idea of resource productivity, enabling a proper decoupling of economic growth from raw material use. Several studies [22,23] indicate that incorporating digital technologies into the EU’s environmental strategies has improved energy efficiency and extended the lifespan of materials. Likewise, Cudecka-Purina et al. [24] and Ferro and Bonollo [25] highlight that the European circular economy—fueled by AI and innovative policies—directly supports the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals, mainly by reducing waste and boosting recycling rates.

AI applications in circular resource management are essential for optimizing collection, sorting, and reuse processes. Fang et al. [12] demonstrate that intelligent systems can reduce waste collection routes by up to 36%, significantly lowering logistics costs and carbon emissions. Digital tools such as MWaste and Pilahin achieve over 90% accuracy in waste classification, demonstrating AI’s potential to enhance operational efficiency [26,27]. In electronic waste management, Ramya et al. [28] found that hybrid neural networks can significantly improve the recovery of valuable components, thereby reducing environmental impact and industrial costs.

Beyond optimizing resource flows, AI also increases resource productivity by enhancing process efficiency and enabling real-time adjustments in manufacturing and service activities [4,5,8]. Intelligent control systems reduce downtime, streamline production cycles, and facilitate more precise allocation of inputs, all of which contribute to generating more output from the same amount of material. In parallel, AI-enabled sorting, classification, and traceability technologies significantly improve the effectiveness of recycling systems by increasing the purity of recovered materials and reducing contamination rates. The literature, therefore, provides a coherent basis for expecting that countries with higher levels of AI uptake will exhibit more advanced recycling outcomes and higher resource productivity, as digital technologies enable tighter coordination between material flows and recovery processes [5,25].

At the industrial level, AI enables a shift toward symbiotic models in which resource flows are shared across economic sectors. Patricio et al. [29] reveal that mechanisms based on predictive analytics can identify opportunities for intersectoral collaboration, helping to reduce the material footprint and strengthen circular value chains. At the same time, blockchain technologies improve AI’s potential by ensuring traceability and transparency in circular processes. Ahmed and MacCarthy [15] and Hakkarainen and Colicev [30] demonstrate that decentralized ledgers can verify the sustainable origin of materials and prevent fraud within supply chains. Other researchers [16,31] emphasize that combining AI and blockchain allows for complete product lifecycle tracking, laying the foundation for automated yet ethically validated decision-making. However, the literature acknowledges that institutional and ethical challenges accompany these benefits. Han et al. [32] warn about the risks linked to data centralization and a lack of digital skills, especially in countries with less developed technological infrastructure. Similarly, Chaudhary and Nidhi [11] emphasize the urgent need for ethical governance frameworks to prevent the emergence of new forms of technological inequality.

The integration of AI into circular processes aligns closely with European sustainability policies. According to Fetting [33], the European Green Deal promotes digitalization as the key driver of the ecological transition, while Castellet-Viciano et al. [34] argue that green infrastructure can evolve into data hubs for decision-making on resource reuse. In this context, Hernández-Chüber et al. [35] show that using machine learning models in wastewater management enables dynamic optimization of tariffs and resource flows, helping balance sustainability with profitability.

Recent empirical studies support the idea that AI enhances circular performance by increasing resource efficiency. Research such as [35,36,37,38] shows that predictive neural network models can reduce material waste by 20–25% and increase recycling rates from 50% to over 80% within ten years. Similar findings in the energy and transportation sectors confirm that AI can help decouple economic growth from the use of limited resources, thereby supporting Europe’s climate-neutrality goals [39]. From a broader perspective, the literature suggests that AI-driven circularity involves reconfiguring global value chains through digitalization, traceability, and intersectoral collaboration [40,41]. This transformation is also highlighted in the comparison by Marino and Pariso [7], who argue that the circular performance of EU member states is directly related to their levels of digitalization and investment in research and innovation [42]. However, the success of circular performance depends not only on technology but also on institutional and social capacity to implement it effectively. Bellini and Bang [43] highlight ongoing barriers to data interoperability, while Agrawal et al. [44] emphasize the need to standardize circular indicators to enable true comparability among member states. Additionally, Rusch et al. [10] highlight the ethical considerations of these efforts, arguing that AI should not be seen solely as a tool for efficiency but as a transformative force for collective governance.

Therefore, within the European Union, AI adoption increasingly relates to the success of the circular economy. A well-established digital infrastructure enables complex analysis of production, recycling, and consumption, helping reduce material footprints and enhance resource efficiency. As Sánchez-García et al. [3] illustrate, the combination of AI and circular innovation creates a new economic model grounded in adaptability, transparency, and shared responsibility. AI, therefore, becomes not only a tool for efficiency but also a key component of the new sustainable European economy. This cognitive infrastructure redefines the relationship among technology, resources, and development.

AI’s growing presence in production systems is increasingly associated with measurable reductions in material use [25]. By enabling more accurate demand forecasting, identifying inefficiencies along supply chains, and supporting predictive maintenance, AI-driven processes limit unnecessary extraction of raw materials and prevent overproduction. Several studies show that machine learning and intelligent monitoring systems contribute to substantial reductions in material throughput by helping firms anticipate resource needs more precisely and avoid losses associated with inefficient operations. These mechanisms establish a clear conceptual link between AI adoption and lower material footprints at the macro level, particularly in economies with sufficiently developed digital infrastructure to support such applications.

Based on these allegations, the hypothesis suggests that greater adoption of artificial intelligence in EU member states is associated with improved circular economy performance, as evidenced by increased resource efficiency, higher recycling rates, and a smaller material footprint.

Hypothesis H1.

Higher levels of AI adoption across EU Member States are associated with better circular economy performance, as indicated by lower material footprints, higher resource productivity, and higher recycling rates.

2.2. Patterns of AI Integration and Circular Sustainability

Europe’s shift toward a smart circular economy is not just an economic change but a complex reshaping of the continent’s technological and institutional landscape. Given the rapid digitalization, EU member states have advanced at different speeds in incorporating AI into economic and environmental activities, leading to unique patterns of sustainable success. As Sánchez-García et al. [3] note, the adoption of AI and related technologies, from blockchain to the Internet of Things, not only transforms resource management but also reignites debates on European cohesion and convergence in sustainability.

According to Neves and Marques [1], the circular economy is a regenerative system in which resource valorization, reuse, and recycling are interconnected processes driven by digital innovation. Similarly, Mukherjee et al. [2] contend that AI serves as the link connecting these processes, facilitating systemic coordination of material and informational flows across industries and regions. However, the level of technological integration varies widely across countries, leading to comparable clusters of circular performance shaped by digital infrastructure, institutional maturity, and public policy priorities [7,8].

Recent research indicates that EU member states can be categorized by their levels of digitalization and progress in the circular economy. Kabirifar et al. [45] note that regions with advanced integration of reduction, reuse, and recycling principles, supported by AI, achieve better performance in waste and resource management. Complementary studies by Massaro et al. [40] show that adopting Industry 4.0 technologies offers competitive advantages in the energy and manufacturing sectors, accelerating the transition toward sustainable circular models.

Conversely, comparative analyses by Marino and Pariso [7] reveal ongoing fragmentation between Northern and Southern Europe, where differences in digital infrastructure and innovation capacity directly influence circular performance. Mhatre et al. [8] identify two main clusters: one comprising economies with strong technological integration and coherent public policies, and another characterized by fragmented approaches and dependence on linear resource models.

The clustering dynamic also extends to patterns of waste and resource management. Parajuly et al. [46] and Shittu et al. [47] demonstrate that national recycling and e-waste reuse policies produce different effects depending on the level of automation and AI adoption. Countries with strong digital infrastructures can integrate automated material classification systems based on visual recognition and machine learning, achieving high efficiency levels [12,48]. In contrast, economies with slower digitalization remain reliant on manual processes and strict regulations, placing them in medium- or low-performance clusters [49,50].

The literature at the intersection of AI and blockchain further underscores the development of distinct models of digital circularity. These combined technologies ensure complete traceability of material flows, improve transparency, and reduce losses [51,52]. In Western Europe, where these tools are widely adopted, recycling and reuse rates are notably higher than in regions with developing infrastructures [30,31].

Ortega-Gras et al. [41] describe this as a “dual transition”, both digital and green, emphasizing the synergy between AI and sustainability in Europe’s economy. They state that countries that align technological investments with climate strategies tend to develop high-performance circular clusters characterized by innovation, effective governance, and intersectoral collaboration [40].

Although empirical evidence supports the positive relationship between digitalization and circular performance, the literature also emphasizes systemic barriers. Han et al. [32] highlight challenges with interoperability between technological systems and the lack of digital skills in public administrations. These issues explain why some member states remain on the fringes of high-performance clusters despite implementing ambitious sustainability policies [43,44].

At the macroeconomic level, scholars [53,54] examine AI integration into the circular economy through European policy frameworks, highlighting how legislative complexity can exacerbate structural disparities among countries. Nations with stable regulatory environments and significant investments in green innovation are more likely to develop high-performance clusters [55,56]. At the same time, regions with fragmented regulation tend to progress more slowly toward circularity goals.

Recent research on AI applications in wastewater management clearly shows how technological differences lead to varying sustainability outcomes. Countries that implement predictive models and optimization algorithms for water reuse can significantly reduce energy costs and resource waste. In contrast, regions relying on traditional infrastructure find it difficult to adopt such innovations [13,57,58].

From a regional perspective, Stoenoiu and Jäntschi [9] confirm similarities in circularity levels among Eastern European countries, where digital transformation is still in its early stages. In contrast, Northern and Western European economies form clusters of digital and ecological convergence, where AI becomes a strategic tool for competitiveness and social cohesion [36,59].

Theoretically, scholars emphasize AI’s role as a shaping force in the development of sustainable ecosystems. Rusch et al. [10] and Chaudhary & Nidhi [12] view AI not just as a tool for efficiency but as a transformative power that reshapes the relationships among technology, governance, and social equity. As a result, clusters of circular performance reflect not only technological gaps but also the extent to which each country incorporates ethical and institutional values into its digital transition.

Based on this evidence, the hypothesis suggests that EU member states can be grouped into similar clusters characterized by the interaction between the level of artificial intelligence adoption and circular economy performance, revealing different models of technological integration and sustainability.

Hypothesis H2.

EU Member States can be grouped into homogeneous clusters based on the relationship between AI adoption levels and circular economy outcomes, revealing distinct patterns of technological integration and sustainability performance.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Design

The research design aimed to explore the complex relationships among the use of artificial intelligence-based technologies, economic performance, and sustainability aspects across European Union countries. The study employed a quantitative, comparative, and exploratory approach to identify hidden patterns of interdependence and convergence among indicators describing digitalization and resource-efficiency processes. Using a multimethod analytical framework, the research combined factor analysis, Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) neural networks, and cluster analysis to simultaneously reveal causal relationships, structural patterns, and groupings among member states.

The methodological structure followed a logical sequence: factor analysis reduced data dimensions and identified underlying factors explaining correlations among economic, technological, and ecological variables; the MLP neural network then analyzed the strength and direction of these relationships, offering a nonlinear perspective on how AI use affects resource performance; and the cluster analysis grouped member states based on their levels of digitalization and sustainability.

The research employed a deductive approach grounded in specialized literature, but also incorporated inductive reasoning when analyzing emerging patterns in the data. This way, the design balanced statistical precision with contextual insight, establishing a strong foundation for comparing digital and sustainable performance across the European Union.

3.2. Selected Data

The empirical analysis utilized a dataset from official European sources, primarily Eurostat and the European Commission. The empirical analysis uses harmonized Eurostat data for 2023, the most recent year with complete and comparable values available across all indicators included in the study. Using a single, fully aligned cross-sectional dataset ensures that the variables reflect the same economic and technological context, avoiding inconsistencies that might arise from combining observations drawn from different years. This temporal choice also reflects the period when AI technologies began to have more pronounced effects on resource productivity, waste generation, and recycling outcomes across EU Member States.

The variable selection aimed to balance the technological, economic, and ecological aspects of development. To achieve this, the study included the following variables: AIT (the proportion of enterprises using at least one AI-based technology), RMC (raw material consumption, in tonnes per capita), RP (resource productivity, in PPS/kg), GPW (packaging waste generated, kg per capita), GPP (plastic packaging waste, kg per capita), RRPWt (recycling rate of total packaging waste), and RRPWp (recycling rate of plastic packaging waste) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Variables used and measures.

These variables assess the relationship between digital transformation and ecological performance, chosen for their ability to indicate both the extent of new technology adoption and the efficiency of resource management. Ideally, including these variables allows for analysis within a triple-conceptual framework—digitalization, sustainability, and productivity—that shapes Europe’s new circular economy model.

To ensure consistency and comparability across EU Member States, the study uses AIT as the single indicator of artificial intelligence adoption. Although AI is inherently multidimensional, the AIT measure, defined by Eurostat, captures whether enterprises use at least one of several AI-based technologies, including machine learning, natural language generation, text mining, computer vision, and robotic process automation. This composite structure allows AIT to reflect the general level of AI integration without relying on multiple, heterogeneous metrics that differ in scale, availability, and reporting quality across countries. Selecting a single, harmonized indicator also reduces the risk of multicollinearity and ensures methodological coherence across factor analysis, neural network modeling, and cluster analysis. Thus, AIT provides a robust, comparable proxy for assessing how AI uptake relates to national-level circular economy performance.

Using these variables, the research provides a strong empirical foundation for testing hypotheses about how digital transformation impacts economic and ecological sustainability.

3.3. Methods

The analysis followed a methodological framework structured in three interconnected stages: factor analysis, the Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) neural network, and cluster analysis. Each method examined different levels of relationships among variables, from uncovering latent structures to modeling nonlinear interactions and grouping countries based on their sustainability and digitalization profiles.

The factor analysis was the initial step, aimed at reducing data dimensionality and identifying common factors that explain the correlations among the studied variables [66]. We can express the factor model mathematically as

where

—the factor loadings;

—observed variable (FW, PD, GDPpc, PTE, and FCEH);

—common factors;

—unique errors.

The next stage used a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) neural network to model the nonlinear relationships among the variables identified earlier. The MLP architecture included an input layer (AIT, RMC, RP, GPW, GPP, RRPWt, RRPWp), a hidden layer, and an output layer that represented the sustainability performance indicators. The hidden layer employed a sigmoid activation function, while the output layer utilized a linear activation function. The training process followed the backpropagation algorithm [67].

where

—input variable (FW);

—input variables (PD, GDPpc, PTE, and FCEH);

and —connection weights;

and —biases;

, —activation functions.

Finally, cluster analysis grouped European Union countries based on the similarities among the studied variables [68]. Using Euclidean distance and the Ward method, the analysis produced homogeneous clusters that reflect different levels of digital integration and sustainability [69].

By combining these methods, the study employed a comprehensive and rigorous approach that not only tested the proposed hypotheses but also offered an integrated interpretation of how technology, economy, and environment interact within the modern European context.

4. Results

To test hypothesis H1, we first conducted an exploratory factor analysis. The KMO coefficient (0.629) indicated good sample adequacy. At the same time, the highly significant Bartlett’s test (χ2 = 69.091, p < 0.001) confirmed the presence of interdependent relationships among variables, justifying the use of the principal axis extraction method.

Two main tendencies emerged from the overall correlation structure. On one hand, the use of AI technologies (AIT) showed a positive association with resource productivity (r = 0.463, p < 0.01) and with the generation of packaging waste (r = 0.400, p < 0.05), indicating that more digitalized economies tend to have higher productivity levels and produce enough economic activity to generate significant material flows (Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlation Matrix.

Conversely, weak or negative links between AI adoption and recycling rates, especially for plastic waste (r = −0.150), suggest that AI adoption does not automatically improve ecological efficiency. Instead, it often reveals structural differences between countries with advanced recycling systems and those still developing.

The single extracted factor, with an initial eigenvalue of 2.474 and an explained variance of 48.89%, captures this ambivalence. This result indicates that the factor captures only part of the multidimensional relationships among AI adoption, resource productivity, waste generation, and recycling rates. The remaining unexplained variance suggests that additional latent dimensions are likely present but could not be extracted without compromising statistical reliability, given the limited number of observations and the heterogeneity of the indicators. Therefore, while the one-factor solution provides a proper synthetic representation of the dominant pattern, linking productivity and material flows, it should be interpreted with caution, recognizing that it reflects only a partial view of the broader structural interplay between digitalization and circular economy performance.

The highest factor loading was observed for GPW (0.976), followed by RP (0.648) and GPP (0.570), indicating that the primary factor dimension reflects a combination of economic performance based on resource productivity and pressure from waste flows (Table 3). The resulting factor describes a structural model of “partial circular productive growth,” where AI promotes efficiency but does not fully resolve the tensions between economic expansion and material sustainability.

Table 3.

Communalities and factor matrix.

The extracted communalities support this interpretation. GPW (0.952) and RP (0.420) retain most of their initial variance, indicating a consistent relationship between economic intensity and AI use. In contrast, AIT (0.170), RMC (0.020), and RRPWp (0.015) show low communalities, suggesting these dimensions are only weakly explained by the common factor. This distribution of variance implies that digitalization does not affect all components of the circular economy equally, but has a greater impact on high-value-added sectors. At the same time, its effects on recycling and raw material consumption remain limited.

The factor analysis supports the idea that AI helps reshape the European circular economy, but its effects depend on each member state’s institutional and infrastructural context. The positive connections among AIT, RP, and GPW demonstrate convergence between technological innovation and economic performance, while also highlighting the persistence of the productivity paradox, in which increased efficiency does not necessarily reduce resource pressure. Without cohesive circular policies, AI risks widening the gap between environmentally advanced countries and those still in the early stages of digital transition. The single identified factor thus reflects continuity, not rupture, between digital progress and ecological challenges, confirming that AI can drive Europe’s circular economy only when technological innovation is paired with investment in infrastructure, clear recycling policies, and adaptable institutional frameworks.

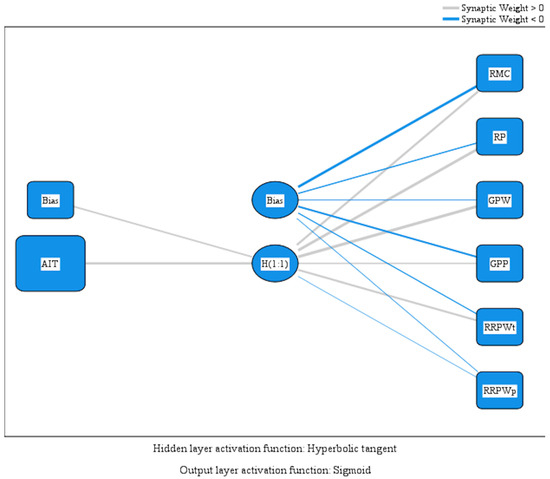

Analyzing the multilayer perceptron (MLP) artificial neural network offers a more detailed and nuanced understanding of how AI technology adoption influences the circular performance of European economies. The model used AIT, the share of businesses adopting at least one AI-based technology, as the independent variable, and examined its relationship with six key indicators of the circular economy: raw material consumption (RMC), resource productivity (RP), generation of packaging waste (GPW), plastic packaging waste (GPP), and their respective recycling rates (RRPWt and RRPWp) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

MLP model. Source: author’s design with SPSS v.27.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Note: AIT—Enterprises uses at least one of the AI technologies; RMC—Raw material consumption; RP—Resource productivity; FW—Food waste—bio, household, and similar waste; GPW—Generation of packaging waste; GPP—Generation of Plastic packaging; RRPWt—Recycling rate of packaging waste—total; RRPWp—Recycling rate of plastic packaging waste.

The model included a single hidden layer with two neurons, selected based on convergence stability and the small sample size. The hidden layer used a hyperbolic tangent activation function, while the output layer employed a linear function. Training was performed using the backpropagation algorithm with a fixed learning rate of 0.01 and a maximum of 10,000 iterations, and early stopping was used when the validation error failed to improve for 20 consecutive epochs. We randomly split the dataset into 70% for training and 30% for testing to evaluate the model’s generalization.

With a total training error (Sum of Squares Error) of 3.510 and an average error of 0.867, the model showed stability and consistency in estimating overall relationships. The testing phase confirmed this reliability: the total error stayed moderate at 2.769, and the average error of 1.037 indicated a reasonable ability to generalize. Essentially, the neural network detected recurring patterns linking AI use with circular performance, even though these relationships vary across the economic and ecological dimensions of sustainability.

Within the model, the connections between the hidden layer and the output variables showed several significant tendencies (Table 4).

Table 4.

MLP parameter estimates.

The strongest positive relationship was between AIT and resource productivity (RP), with a high connection coefficient (1.386), followed closely by the relationship with packaging waste generation (GPW—1.532). This dual correlation reflects a trend already identified in the literature: artificial intelligence enhances economic efficiency but can also increase material flows, especially in economies with active industrial sectors. Therefore, AI acts as both a catalyst for productivity and a driver of resource pressure, particularly when technological innovation is not supported by firm policies that promote economic decoupling.

Moderate positive correlations with RMC (0.847) and GPP (0.522) suggest that AI integration does not significantly reduce raw material consumption or plastic packaging production but instead tends to boost their efficiency. More broadly, these findings highlight an incomplete shift toward circularity: while AI provides tools for increased efficiency, without strong regulations and recycling infrastructure, its benefits remain limited.

The findings on recycling are also fairly mixed. The link between the hidden layer and overall recycling rates (RRPWt = 0.833) suggests a positive but moderate effect of AI on waste recovery capacity. This result indicates that industrial digitalization can enhance material traceability and circular logistics, although these advances mainly occur in technologically advanced economies. On the other hand, the weak negative relationship with plastic packaging recycling (RRPWp = −0.084) underscores a vulnerability; plastic waste management is an area where AI technologies have yet to reach their full potential.

Assessing model performance using relative error metrics offers additional insight into the consistency of these relationships. Minor deviations occurred for RP (0.775) and GPW (0.736) during training, confirming the strength of economic connections, while higher errors for GPP (0.981) and RRPWp (1.001) indicated greater uncertainty in managing plastic waste. During testing, variations increased for GPW and GPP, suggesting that the relationships between AI and waste generation depend on each country’s structural traits—an indirect confirmation of the heterogeneity observed across Europe in the factor analysis.

The network parameters also revealed a distinct separation between productive and ecological aspects. The negative bias of the hidden layer (−1.335) and the outputs related to recycling highlighted systemic tensions in the circular transformation process: although AI enhances efficiency, its benefits are constrained by the lack of consistent institutional frameworks across the European Union. These differences support the concept of digital asymmetry, which proposes that countries with more advanced technological infrastructure reap the benefits of digital circularity more rapidly, while emerging economies are in a gradual adaptation stage.

In the context of hypothesis H1, which posits that higher levels of AI adoption are associated with better circular performance—reflected in lower material footprints, increased resource productivity, and improved recycling rates—the findings provide partial, context-specific validation. The MLP model consistently confirms the positive impact of AI on resource productivity and, to a lesser extent, on recycling processes. However, there is no clear evidence of a reduction in material consumption or a systematic decrease in waste flows, indicating that AI technologies currently serve more as tools for economic optimization rather than proper drivers of ecological sustainability.

Therefore, hypothesis H1 is only partially confirmed, indicating that while AI supports improvements in economic and operational performance, it has not yet fully transformed Europe’s circular economy. The findings reinforce the idea that artificial intelligence can serve as a key driver for sustainable transition. Still, its success depends on coherent public strategies, digital maturity, and the ethical and institutional integration of technology. Without these elements, AI risks merely enhancing economic efficiency without achieving the ultimate goal of the circular economy: balancing growth with resource regeneration.

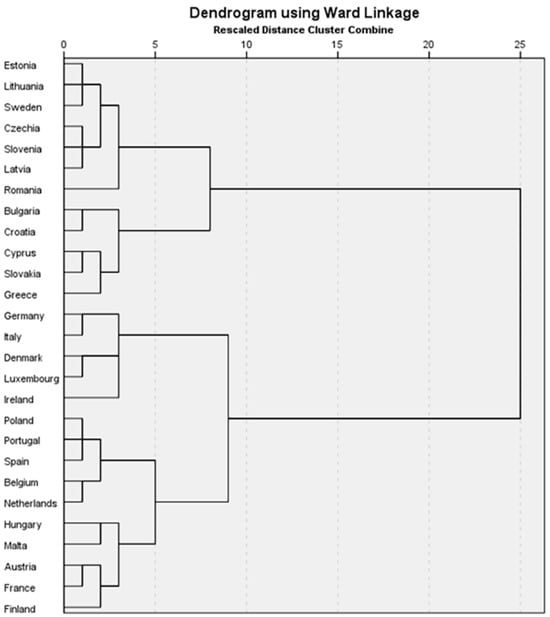

The cluster analysis aimed to identify homogeneous patterns among the member states of the European Union, based on the relationship between the level of adoption of AI-based technologies and the performance of the circular economy. The variable set included indicators relevant to both digitalization and sustainability: AIT (the percentage of enterprises using at least one AI technology), RMC (raw material consumption per capita), RP (resource productivity, expressed in PPS/kg), GPW (generation of packaging waste per capita), GPP (plastic packaging waste per capita), RRPWt (total recycling rate of packaging waste), and RRPWp (recycling rate of plastic packaging).

The hierarchical clustering procedure applied Ward’s minimum-variance method in combination with squared Euclidean distance, which jointly aim to minimize within-cluster variability while maximizing separation between groups. In the dendrogram, the height at which branches merge reflects the degree of dissimilarity among countries; thus, larger vertical jumps indicate substantial structural differences. We defined the cluster boundaries by examining the discontinuities in linkage height. A pronounced increase in the agglomeration coefficient allowed the identification of two major clusters, representing distinct profiles of AI adoption and circular economy performance across EU Member States (Figure 2 and Table A1 in the Appendix A). This threshold provided a statistically coherent point at which further merging would combine countries with fundamentally different technological and environmental characteristics.

Figure 2.

Dendrogram. Source: author’s design with SPSS v.27.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Within each central cluster, the dendrogram showed additional branching, supporting the formation of coherent subclusters. In Cluster A, for example, countries are naturally separated into two subgroups: A1, composed of Baltic and Central European states with emerging digital capabilities, and A2, which includes Southeastern economies characterized by distinct resource-efficiency dynamics and lower AI uptake. Similarly, Cluster B is divided into B1 and B2, differentiating high-performance Western and Northern European economies from those with more heterogeneous circular outcomes. This hierarchical structure reflects both the statistical patterns captured by the clustering algorithm and the underlying economic and technological realities of EU Member States.

The cluster analysis revealed a clear, meaningful structure in how EU member states differ in their AI adoption and circular economy performance. Beyond just listing values, the results show consistent patterns that highlight structural differences in how digitalization and sustainability intersect across European economies.

The primary group, called Cluster A, includes Central and Eastern European countries such as Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia, Romania, the Czech Republic, and Slovenia, along with a secondary subgroup comprising Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Slovakia, and Greece. Overall, these countries have a moderate level of AI technology adoption, around 5.9%, which is notably below the European average of 8.24%. Although digitalization levels remain relatively low, resource productivity is 1.91 PPS/kg, close to the EU average, indicating a growing potential for efficiency gains. However, high raw material consumption (18.9 tonnes per person) and moderate recycling rates (about 62%) suggest an incomplete transition to a circular economy, with traditional economic processes and infrastructure still dominant.

Subcluster A1, which includes the Baltic states of Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia, stands out for its slightly higher recycling rate (63.74%) and a resource productivity level similar to that of more developed economies. These results can be linked to recent investments in digitalization and EU convergence policies that have supported automation and industrial innovation. In contrast, subcluster A2, which groups Southeastern European countries, shows a higher level of resource efficiency (2.05 PPS/kg) but produces less packaging and plastic waste, reflecting less industrialization and a slower rate of AI adoption.

Cluster B, which includes Western and Northern EU countries such as Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, France, Denmark, Finland, and Austria, displays an almost opposite profile. With an average AI adoption rate exceeding 10%, this group demonstrates a high level of technological integration and significantly higher resource productivity (3.27 PPS/kg), nearly twice that of Cluster A. The higher figures for packaging waste generation (182.5 kg per capita) and material consumption (18.3 tonnes per capita) do not suggest structural inefficiency but instead reflect the economic intensity characteristic of developed economies, characterized by extensive value chains and greater capacity for data collection and reporting.

Subcluster B1, composed of high-performing economies such as Germany, Italy, Denmark, Luxembourg, and Ireland, exhibits the highest productivity levels (3.63 PPS/kg) and a digitalization rate well above the European average at 10.85%. These countries combine innovation-driven economies with strong recycling infrastructures (67.18%), showcasing a successful blend of technology and sustainability. In contrast, subcluster B2, which includes diverse economies such as Spain, Belgium, the Netherlands, Austria, and Finland, shows a more complex relationship.

Although the average AI adoption rate remains high at 9.72%, recycling performance varies considerably, with lower scores in certain Nordic and Mediterranean countries. This variation does not indicate a lack of technological ability but instead reflects cultural and institutional differences in the implementation of circular policies. Comparing the two clusters reveals a clear divide between a digital–industrial Europe, known for high technological performance and productivity, and a Europe in transition toward a circular economy, which balances growth with sustainability. Interestingly, both groups have similar levels of raw material use, around 18 to 19 tonnes per person, suggesting that the differences are not due to the material intensity of their economies but to how technology is used to convert resources into economic and ecological value.

The cluster analysis supports hypothesis H2, which posits that EU member states can be logically grouped according to the relationship between AI adoption levels and circular economy performance. Clustering not only demonstrates internal consistency but also highlights a different development approach, where AI serves as a dividing factor in circular performance. Countries in Cluster B have successfully turned technology into a catalyst for sustainability, while those in Cluster A are still in a phase of structural adjustment, where AI functions more as an emerging tool rather than as an integral part of green transition strategies.

The analysis reveals that AI is not the sole driver of progress but part of a broader ecosystem that includes public policies, infrastructure, and human capital prepared for change. In this way, the identified clusters do not represent a static snapshot of Europe but rather a dynamic map of its transition toward an intelligent circular economy, one where technology increasingly integrates with the continent’s structural sustainability.

5. Discussion

This research confirms that transitioning to a European circular economy is a complex process influenced by multiple interactions between AI technology adoption levels and resource-use efficiency. The empirical analysis, based on comparative data from European Union member states, aimed to test two hypotheses. The first suggested that greater AI adoption is associated with better circular performance, indicated by higher resource productivity, a smaller material footprint, and increased recycling rates. The second hypothesis is that member states could be grouped into similar clusters based on the relationship between digitalization and sustainability, revealing different models of technological integration.

The results of the factor analysis and the Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) model offered complementary insights into how artificial intelligence influences the transformation of circular performance. The relationships identified between AIT (the percentage of enterprises using at least one AI technology) and relevant economic indicators, especially resource productivity and packaging waste generation, demonstrate a significant connection between digitalization and efficiency. Moderate positive correlations between AIT and RP, along with the neural model results, suggest that AI adoption enhances the optimization of economic processes, particularly by automating production flows, reducing material losses, and increasing the added value of resources. These findings partly support hypothesis H1, indicating that AI indeed boosts economic performance and resource efficiency, although its effects on ecological sustainability remain inconsistent.

While the findings offer valuable insights into the relationship between AI adoption and circular economy performance, we should interpret the results with caution. Several methodological constraints limit the strength of the conclusions. First, the correlations observed between AI uptake and sustainability indicators are moderate and therefore do not warrant strong causal inferences. Second, the factor analysis revealed relatively low communalities for several variables and a single extracted factor that accounts for less than half of the total variance, indicating that important latent dimensions remain unrepresented in the model. Third, the small sample size and variability in national-level indicators constrain the MLP neural network’s predictive capacity and may introduce instability in the estimated relationships. Taken together, these limitations reinforce our conclusion that Hypothesis H1 is only partially supported and suggest that the empirical patterns we identify should be viewed as indicative rather than definitive. The literature discussed in the theoretical section supports this interpretation. Recent studies [4,5] have shown that industrial digitalization and AI algorithms can significantly improve energy efficiency and resource optimization. However, their environmental benefits largely depend on the level of systemic technological integration. Similarly, Kirchherr and van Santen [70] argue that the European circular economy should be seen not only as a technological change but also as an institutional transformation, in which infrastructure, public policy, and organizational culture are just as necessary as the technology itself.

From this perspective, the factor analysis confirmed that the relationship between AI and sustainability is often ambivalent. While artificial intelligence improves resource productivity, it does not automatically reduce material consumption or increase recycling rates. This observation aligns with the productivity paradox discussed by Bocken and Short [71], which suggests that technological efficiency gains can, in the short term, boost economic activity and overall resource use, partially offsetting the progress driven by innovation. As a result, AI acts as a catalyst for economic performance, although its environmental impact is primarily shaped by each member state’s structural and institutional context.

The MLP neural network model deepened this understanding by showing that the relationships between AI and circular performance are mainly nonlinear and depend on each country’s economic features. The strong links between AIT and RP highlight improved resource efficiency in digital economies. At the same time, the changing values for recycling and material consumption indicate that circular transformation still relies on physical infrastructure and policies. This finding aligns with the conclusions of other authors [1,7,41], who stress that the circular transition needs cross-sectoral data and technology integration and that AI should be seen not as a replacement for environmental policy but as a tool that enhances its effectiveness.

The cluster analysis offered a structural view of how these differences develop throughout Europe. The results identified two main clusters: a digital–industrial Europe, where AI adoption is high and circular performance is well-established, and a Europe that is still evolving, characterized by moderate digitalization and uneven structural efficiency. Cluster A, mainly composed of Central and Eastern European countries such as Romania, Lithuania, and Slovenia, shows moderate AI utilization and improving, but inconsistent, circular performance. Meanwhile, Cluster B, led by Western economies such as Germany, the Netherlands, and Denmark, demonstrates a more advanced integration of AI technologies, along with significantly higher resource productivity and stronger recycling systems.

This differentiation supports the validation of Hypothesis H2 and shows that we can logically group EU member states into homogeneous clusters based on the interaction between AI adoption and circular performance. The analysis shows that although the European Union promotes a unified digital–green transition strategy, empirical evidence reveals a layered dynamic in which progress depends on each country’s ability to turn technology into a driver of sustainability. This conclusion aligns with the observations of Ghisellini et al. [72], who argue that the European circular economy develops unevenly, depending on the economic context, levels of innovation, and waste management infrastructure.

The results also connect to the conceptual model proposed by Pieroni et al. [73], who describe the circular transition as an iterative spiral linking technological innovation, public policy, and organizational behavior. In this framework, countries in Cluster B appear to have reached a more advanced stage of integration, where AI supports not only optimization but also resource-cycle prediction and regenerative product design. Meanwhile, countries in Cluster A remain in an alignment phase, where AI is still seen mainly as an efficiency tool rather than an essential part of the circular model.

Taken together, these results clarify a key point: artificial intelligence, although transformative, does not operate independently. Its impact on sustainability depends on the economic and institutional systems in which it operates. AI can accelerate circular processes when combined with clear public policies, innovation incentives, and an organizational culture focused on sustainability. Without these supportive factors, its effect remains mainly limited to economic efficiency.

In a broader sense, these findings call for a reassessment of the relationship between technology and resources within Europe’s transition framework. AI is more than just a tool for automation—it functions as a form of systemic intelligence capable of predicting material flows, reducing losses, and supporting real-time, data-driven decision-making. As the cited authors [7,41] emphasize, digital and circular transitions cannot develop independently. Artificial intelligence thus becomes not only a means of efficiency but also a connector between the economy and ecology, between performance and renewal.

Reflecting on the two hypotheses leads to a nuanced conclusion. The first (H1) is reasonably supported, confirming AI’s positive impact on resource productivity but not on its consistent effect in reducing material footprints or increasing recycling rates. The second hypothesis (H2) is fully confirmed, as the cluster analysis reveals homogeneous state groups distinguished by their levels of technological integration and circular performance. Together, these findings indicate that AI catalyzes the European circular economy, though its effectiveness depends on institutional maturity and alignment of public policy frameworks.

Ultimately, the research shows that Europe’s shift to a smart circular economy is not automatic but a dynamic, context-dependent process. Artificial intelligence does not replace human and institutional efforts; it supports them by enabling better-informed decisions and more adaptable processes. The real innovation of the AI era is not just in the technology itself but in society’s ability to use it to rethink its relationship with resources, turning economic progress and ecological balance from separate goals into interconnected parts of the same sustainable transition.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

The results of this research strengthen the theoretical link between digital transformation and the circular economy, proposing a unified approach that views artificial intelligence not just as a technological tool but as a systemic driver of sustainability. This study builds upon existing literature by suggesting that the relationship between AI and circular performance depends on institutional factors and the unique socio-economic infrastructure of each member state. This perspective aligns with emerging theories that view the circular economy as a complex adaptive system in which technology simultaneously influences economic, ecological, and organizational aspects.

At the same time, empirical findings show that the relationship between AI and sustainability does not follow a straight line but instead exhibits threshold effects and feedback loops. This understanding provides a new interpretive approach for green-digital transition models. The study’s theoretical contribution lies in developing an explanatory model that integrates the logic of technological innovation with regenerative economics, establishing a foundation for a conceptual framework centered on circular intelligence—an emerging form of coordination among algorithms, resources, and public policies.

5.2. Practical Implications

The findings of this study offer several important implications for policy design across the European Union, particularly in light of the distinct clusters identified through the country-level analysis. The results show that AI adoption and circular economy performance do not evolve uniformly across Member States, indicating that policy interventions should reflect these structural differences rather than rely on a one-size-fits-all approach. Countries situated in the higher-performing cluster, typically characterized by stronger digital infrastructures and mature recycling systems, stand to benefit from policies that encourage deeper integration of AI into advanced material-recovery processes and industrial symbiosis networks. For these economies, the next step is to leverage predictive analytics and automation to optimize value-chain transparency, support product life extension strategies, and accelerate the shift toward high-value closed-loop systems.

By contrast, Member States positioned in the intermediate cluster require policy support focused on strengthening the institutional and technological foundations needed to translate AI potential into tangible circular outcomes. Enhancing digital skills, modernizing waste management infrastructure, and improving data interoperability between public and private actors are essential steps for enabling these countries to adopt AI-driven solutions effectively. Policies that facilitate cross-border knowledge transfer, promote collaborative innovation platforms, and reduce administrative barriers can help bridge the gap between emerging digital capabilities and sustainable resource use.

For countries in the lower-performing cluster, the findings underscore the importance of establishing the basic conditions for AI-enhanced circularity. Strengthening core infrastructure, improving data availability, and supporting long-term investments in digital public services are critical to creating an environment in which AI applications can operate meaningfully. In these contexts, early interventions may focus on targeted pilots in waste-sorting automation, local material-flow monitoring systems, and initiatives that build technical capacity among small and medium-sized enterprises. Such foundational support can foster a more enabling ecosystem from which more advanced AI-based practices can gradually emerge.

Across all clusters, the results highlight the broader need for coherent governance frameworks that align AI innovation with climate and resource-efficiency objectives. This implies not only investing in technologies but also ensuring that regulatory structures, procurement strategies, and public-sector coordination mechanisms are equipped to translate digital advances into measurable circular outcomes. By tailoring policy instruments to the distinctive characteristics of each cluster, the EU can more effectively promote a balanced and inclusive transition toward a digitally enabled circular economy.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Like any empirical study, this research has limitations that suggest new directions for scholarly work. The analysis used a limited set of macroeconomic and ecological variables that do not fully capture the internal processes through which AI affects organizational sustainability and consumer behavior. Additionally, the model was applied at the national level, limiting its ability to identify sector-specific differences among AI technologies.

A methodological limitation arises from the use of waste generation indicators such as packaging waste (GPW) and plastic packaging waste (GPP). These variables may partially reflect the economic scale, production intensity, or consumption patterns of each Member State rather than purely circular performance outcomes. Countries with larger or more industrialized economies naturally generate higher volumes of waste, independent of their circularity efforts. As a result, these indicators may confound structural economic effects with sustainability performance. Future research could address this issue by normalizing waste data through sectoral decomposition, incorporating per-unit-output waste intensities, or using firm-level datasets that better isolate circular practices from macroeconomic size effects.

Temporal constraints, stemming from data availability for a single analysis period, also limited the ability to observe dynamic changes in the circular transition. Future research could overcome these limitations by employing longitudinal models and expanding the range of variables to include institutional factors, innovation metrics, and firm-level microeconomic data. Another promising avenue involves qualitative analysis of how digital governance policies and circular economy strategies interact. This approach would not only validate the relationships identified here but also enhance understanding of the social and organizational mechanisms that influence AI’s effectiveness in promoting sustainability.

6. Conclusions

This study provides an integrated examination of how the adoption of artificial intelligence relates to circular economy performance across EU Member States, combining factor analysis, neural network modelling, and cluster analysis. The results show that AI contributes meaningfully to resource productivity, confirming recent findings by Sánchez-García et al. [3] and Madanaguli et al. [4], who similarly highlight the potential of digital technologies to enhance efficiency and reduce operational losses. However, consistent with the observations of Gunter [18] and Mazur-Wierzbicka [23], the results suggest that AI alone is insufficient to drive significant reductions in material consumption or substantial improvements in recycling outcomes without supportive policy and infrastructural frameworks.

The partial confirmation of Hypothesis H1 reflects these structural dynamics. Moderate correlations and the limited variance explained by the factor analysis suggest that the relationship between AI and circular performance is multidimensional and context-dependent. The neural network results reinforce this complexity, revealing nonlinear but constrained associations that resonate with the broader literature on digital sustainability, which emphasizes the need for integrated technological and regulatory approaches [10,44]. These findings collectively suggest that digital tools can enable circularity. Still, their effectiveness depends on the maturity of public institutions, the availability of recycling infrastructure, and the alignment of market incentives.

The cluster analysis provides the most unmistakable evidence of structural differentiation within the EU. Countries with high AI uptake and firm productivity, such as Germany, Denmark, and the Netherlands, mirror the characteristics of the leading circular economies described in previous comparative studies by Marino and Pariso [7] and Stoenoiu and Jäntschi [9]. By contrast, countries in the lower-performing clusters share features consistent with the barriers identified by Han et al. [32] and Bellini and Bang [43], including infrastructural gaps, limited digital capabilities, and regulatory fragmentation. This confirms Hypothesis H2 and highlights the continued divergence between digital–industrial economies and those still transitioning toward advanced circular practices.

From a strategic and policy perspective, the findings underscore the importance of integrating AI adoption into broader systemic strategies for circular economy transformation. Successful circularity requires more than technological uptake: it depends on coordinated investments in digital skills, waste management infrastructure, and cross-sectoral governance, consistent with recommendations in recent sustainability transition research [24,34]. Policies that link AI innovation to material efficiency standards, incentivize product life extension, and improve traceability across value chains can strengthen the impact of digital technologies on ecological outcomes.

Overall, this research contributes to the growing evidence that Europe’s digital and circular transitions must evolve together. While AI enhances efficiency and supports decision-making, it is the integration of technology with coherent policy frameworks, institutional capacity, and societal engagement that ultimately determines progress. Future research should build on this foundation by employing longitudinal designs, sector-specific metrics, and firm-level datasets that capture the micro-level dynamics of AI-driven circularity. Such approaches would enable a more precise identification of the mechanisms through which digital transformation reshapes the sustainability landscape in the European Union.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a publicly accessible repository. The data presented in this study are openly available: Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/isoc_eb_ai__custom_18453074/default/table (accessed on 30 October 2025); https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/cei_pc020/default/table?lang=en&category=cei.cei_pc (accessed on 30 October 2025); https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/cei_pc035/default/table?lang=en&category=cei.cei_pc (accessed on 30 October 2025); https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/cei_pc040/default/table?lang=en&category=cei.cei_pc (accessed on 30 October 2025); https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/cei_pc050/default/table?lang=en&category=cei.cei_pc (accessed on 30 October 2025); https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/cei_wm020/default/table?lang=en&category=cei.cei_wm (accessed on 30 October 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EU | European Union |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CE | Circular economy |

| MLP | Multilayer Perceptron |

| AIT | Proportion of enterprises using at least one AI-based technology |

| RMC | Raw material consumption |

| RP | Resource productivity |

| GPW | Packaging waste generated |

| GPP | Plastic packaging waste |

| RRPWt | Recycling rate of packaging waste—total |

| RRPWp | Recycling rate of plastic packaging waste |

| FW | Food waste |

| GDPpc | GDP per capita |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Cluster data.

Table A1.

Cluster data.

| Clusters | Country | AIT | RMC | RP | GPW | GPP | RRPWt | RRPWp | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster A | Subcluster A1 | Estonia | 5.19 | 24.223 | 1.2405 | 139.25 | 34.78 | 68.5 | 42.4 |

| Lithuania | 4.86 | 21.024 | 1.6456 | 140.02 | 36.13 | 60.8 | 42.9 | ||

| Sweden | 10.37 | 22.474 | 1.9501 | 125.2 | 34.05 | 68.5 | 28.6 | ||

| Czechia | 5.90 | 16.68 | 2.4796 | 125.94 | 25.82 | 74.8 | 52.4 | ||

| Slovenia | 11.37 | 16.557 | 2.3763 | 138.54 | 30.69 | 73.6 | 51.5 | ||

| Latvia | 4.53 | 16.674 | 1.9311 | 144.75 | 25.71 | 63.1 | 59.2 | ||

| Romania | 1.51 | 28.76 | 1.0619 | 133.26 | 27.25 | 36.9 | 43.7 | ||

| Subcluster A1 mean | 6.25 | 20.91 | 1.81 | 135.28 | 30.63 | 63.74 | 45.81 | ||

| Subcluster A2 | Bulgaria | 3.62 | 21.233 | 1.0643 | 82.73 | 24.18 | 57.9 | 41.7 | |

| Croatia | 7.89 | 15.55 | 2.3444 | 81.39 | 18.52 | 51.9 | 28.2 | ||

| Cyprus | 4.67 | 18.749 | 1.8251 | 103.87 | 25.28 | 67.3 | 40.5 | ||

| Slovakia | 7.04 | 13.496 | 2.5425 | 103.94 | 25.17 | 71.9 | 54.1 | ||

| Greece | 3.98 | 11.458 | 2.4725 | 107.36 | 25.83 | 49.2 | 34.7 | ||

| Subcluster A2 mean | 5.44 | 16.0972 | 2.04976 | 95.858 | 23.796 | 59.64 | 39.84 | ||

| Cluster A mean | 5.91 | 18.91 | 1.91 | 118.85 | 27.78 | 62.03 | 43.33 | ||

| Cluster B | Subcluster B1 | Germany | 11.55 | 12.775 | 3.6509 | 215.19 | 37.51 | 69.4 | 52.2 |

| Italy | 5.05 | 9.994 | 4.5275 | 219.53 | 38.82 | 77.2 | 58.0 | ||

| Denmark | 15.17 | 20.757 | 2.0817 | 192.38 | 40.62 | 62.7 | 27.8 | ||

| Luxembourg | 14.45 | 31.892 | 4.3235 | 207.67 | 34.98 | 65.6 | 38.9 | ||

| Ireland | 8.01 | 14.026 | 3.5616 | 223.14 | 66.53 | 61 | 29.6 | ||

| Subcluster B1 mean | 10.85 | 17.89 | 3.63 | 211.58 | 43.69 | 67.18 | 41.30 | ||

| Subcluster B2 | Poland | 3.67 | 15.043 | 1.7497 | 172.69 | 34.44 | 67.4 | 46.3 | |

| Portugal | 7.86 | 15.947 | 2.0324 | 183.77 | 41.37 | 61.8 | 39.5 | ||

| Spain | 9.18 | 8.857 | 3.9952 | 185.53 | 42.67 | 69.9 | 52.7 | ||

| Belgium | 13.81 | 11.78 | 3.6386 | 166.72 | 29.97 | 79.7 | 59.5 | ||

| Netherlands | 14.10 | 29.18 | 6.3188 | 168.52 | 29.8 | 75.8 | 49.1 | ||

| Hungary | 3.68 | 13.445 | 2.2029 | 152.95 | 41.31 | 46.5 | 22.9 | ||

| Malta | 13.17 | 11.619 | 4.0208 | 171.38 | 29.29 | 33.7 | 17.5 | ||

| Austria | 10.79 | 21.445 | 2.7844 | 152.37 | 32.29 | 64.9 | 26.9 | ||

| France | 5.88 | 14.088 | 3.222 | 172.82 | 35.46 | 69 | 25.9 | ||

| Finland | 15.10 | 44.342 | 1.0005 | 153.46 | 28.49 | 59.4 | 29.3 | ||

| Subcluster B2 mean | 9.72 | 18.57 | 3.10 | 168.02 | 34.51 | 62.81 | 36.96 | ||

| Cluster B mean | 10.09 | 18.34 | 3.27 | 182.54 | 37.57 | 64.26 | 38.40 | ||

| EU mean | 8.24 | 18.60 | 2.67 | 154.24 | 33.22 | 63.27 | 40.59 | ||

References

- Neves, S.A.; Marques, A.C. Drivers and barriers in the transition from a linear economy to a circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 341, 130865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Nagariya, R.; Baral, M.M.; Patel, B.S.; Chittipaka, V.; Rao, K.S.; Rao, U.V.A. Blockchain-based circular economy for achieving environmental sustainability in the Indian electronic MSMEs. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2023, 34, 997–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-García, E.; Martínez-Falcó, J.; Marco-Lajara, B.; Manresa-Marhuenda, E. Revolutionizing the circular economy through new technologies: A new era of sustainable progress. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2024, 33, 103509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madanaguli, A.; Sjödin, D.; Parida, V.; Mikalef, P. Artificial intelligence capabilities for circular business models: Research synthesis and future agenda. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 200, 123189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, T.H.; van Loosdrecht, M.C.; Dai, Y.; Tong, Y.W. Machine learning and circular bioeconomy: Building new resource efficiency from diverse waste streams. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 369, 128445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbate, T.; Elgarahy, A.M.; De Pascale, G. Coming out the egg: Assessing the benefits of circular economy strategies in agri-food industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 385, 135665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, A.; Pariso, P. Comparing European countries’ performances in the transition towards the Circular Economy. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 729, 138142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhatre, P.; Panchal, R.; Singh, A.; Bibyan, S. A systematic literature review on the circular economy initiatives in the European Union. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoenoiu, C.E.; Jäntschi, L. Circular Economy Similarities in a Group of Eastern European Countries: Orienting towards Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusch, M.; Schöggl, J.P.; Baumgartner, R.J. Application of digital technologies for sustainable product management in a circular economy: A review. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2023, 32, 1159–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, P.; Nidhi, R. Artificial intelligence and blockchain: A breakthrough collaboration. J. Intellect. Prop. Rights 2023, 28, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, B.; Yu, J.; Chen, Z.; Osman, A.I.; Farghali, M.; Ihara, I.; Hamza, E.H.; Rooney, D.W.; Yap, P.S. Artificial intelligence for waste management in smart cities: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 1959–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Chover, V.; Bellver-Domingo, Á.; Castellet-Viciano, L.; Hernández-Sancho, F. AI Applied to the Circular Economy: An Approach in the Wastewater Sector. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluleye, B.I.; Chan, D.W.; Antwi-Afari, P. Adopting artificial intelligence for enhancing the implementation of systemic circularity in the construction industry: A critical review. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 35, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; MacCarthy, B. Blockchain-enabled supply chain traceability—How wide? How deep? Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2023, 263, 108963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, D.; Jalali, H.; Ansaripoor, A.H.; De Giovanni, P. Traceability vs. sustainability in supply chains: The implications of blockchain. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 305, 128–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockburn, I.; Henderson, R.; Stern, S. The impact of artificial intelligence on innovation: An exploratory analysis. In The Economics of Artificial Intelligence: An Agenda; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2018; pp. 115–146. [Google Scholar]

- Gunter, S. Circular economy: Illusion or first step towards a sustainable economy: A physico-economic perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, H. Building a circular economy. Nat. Outlook 2022, 611, S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhajharia, K.; Mathur, P.; Jain, S.; Nijhawan, S. Crop yield prediction using machine learning and deep learning techniques. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 218, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganeshkumar, C.; Jena, S.K.; Sivakumar, A.; Nambirajan, T. Artificial intelligence in agricultural value chain: Review and future directions. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2023, 13, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Song, W.; Liu, Y. Leveraging digital capabilities toward a circular economy: Reinforcing sustainable supply chain management with Industry 4.0 technologies. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 178, 109113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur-Wierzbicka, E. Circular economy: Advancement of European Union countries. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2021, 33, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudecka-Purina, N.; Atstaja, D.; Koval, V.; Purvins, M.; Nesenenko, P.; Tkach, O. Achievement of sustainable development goals through the implementation of circular economy and developing regional cooperation. Energies 2022, 15, 4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, P.; Bonollo, F. Design for Recycling in a Critical Raw Materials Perspective. Recycling 2019, 4, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumwar, S. MWaste: A deep learning approach to manage household waste. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.14498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saptaputra, E.H.; Bonafix, N.; Araffanda, A.S. Mobile app as digitalisation of waste sorting management. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1169, 012007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramya, P.; Ramya, V.; Rao, M.B. An efficient e-waste management system through energy-aware routing and hybrid optimization deep learning routing on an IoT-cloud platform. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Inventive Computation Technologies (ICICT), Lalitpur, Nepal, 10–12 April 2023; pp. 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patricio, J.; Kalmykova, Y.; Rosado, L.; Cohen, J.; Westin, A.; Gil, J. Method for identifying industrial symbiosis opportunities. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 185, 106437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakkarainen, T.; Colicev, A. Blockchain-enabled advances (BEAs): Implications for consumers and brands. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 160, 113763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzio, C.; Viglia, G.; Lemarie, L.; Cerutti, S. Toward an integration of blockchain technology in the food supply chain. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 162, 113909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Hu, R.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, H. Research on green technology innovation in manufacturing firms from ESG perspective. Acad. J. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2023, 5, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetting, C. The European Green Deal; ESDN Report No. 53; ESDN: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Castellet-Viciano, L.; Hernández-Chover, V.; Hernández-Sancho, F. The benefits of circular economy strategies in urban water facilities. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 844, 157172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Chover, V.; Castellet-Viciano, L.; Hernández-Sancho, F. A Tariff Model for Reclaimed Water in Industrial Sectors: An Opportunity from the Circular Economy. Water 2022, 14, 3912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladapo, B.I.; Olawumi, M.A.; Omigbodun, F.T. AI-Driven Circular Economy of Enhancing Sustainability and Efficiency in Industrial Operations. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladapo, B.I.; Olawumi, M.A.; Omigbodun, F.T. Machine Learning for Optimising Renewable Energy and Grid Efficiency. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladapo, B.I.; Olawumi, M.A.; Olugbade, T.O.; Ismail, S.O. Data analytics driving net zero tracker for renewable energy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 208, 115061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spandagos, C.; Tovar Reaños, M.A.; Lynch, M. Public acceptance of sustainable energy innovations in the EU. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 340, 130721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaro, M.; Secinaro, S.; Dal Mas, F.; Brescia, V.; Calandra, D. Industry 4.0 and circular economy: An exploratory analysis of academic and practitioners’ perspectives. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2021, 30, 1213–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Gras, J.J.; Bueno-Delgado, M.V.; Cañavate-Cruzado, G.; Garrido-Lova, J. Twin transition through the implementation of Industry 4.0 technologies: Desk-research analysis and practical use cases in Europe. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbdulRafiu, A.; Sovacool, B.K.; Daniels, C. The dynamics of global public research funding on climate change. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 162, 112420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellini, A.; Bang, S. Barriers for data management as an enabler of circular economy: An exploratory study of the Norwegian AEC industry. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1122, 012047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Wankhede, V.A.; Kumar, A.; Luthra, S.; Majumdar, A.; Kazancoglu, Y. An exploratory state-of-the-art review of artificial intelligence applications in circular economy using structural topic modeling. Oper. Manag. Res. 2021, 15, 609–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]