Abstract

As times to access health services have significantly increased worldwide in recent years, strategies and tools to better manage patients’ waiting lists have gained research interest. Computer-Based Patient Prioritization Tools (PPT) aim to manage access to care by ranking patients on waiting lists equitably and rigorously so that higher-priority patients are treated ahead of those with lower priority, regardless of when they were added to the list. However, healthcare systems are inherently complex, involving multiple stakeholders, dynamic interactions, and contextual constraints that make the implementation of such tools challenging. The development of decision-support tools in such environments follows an iterative life cycle that includes design, implementation, verification, validation, and deployment. Among these stages, validation is critical to ensure that the tool not only meets its intended specifications but also produces improved outcomes without unintended consequences when integrated into real-world workflows. Although the literature devoted to PPT is rich, works describing the transition of research prototypes to real-world applications within these complex systems are relatively scarce. This paper presents and discusses the validation process of a PPT, illustrating how this step contributes to improving the tool, building future users’ confidence, and providing insights into the challenges and difficulties related to expert evaluation in complex healthcare environments.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the imbalance between the supply and demand for health services has worsened, leading to longer waiting lists and delays beyond clinically recommended periods. For example, by the end of 2019, over 27,000 patients in Portugal had been waiting for surgery for more than one year [1], while in Australia, the percentage of elective patients waiting over a year ranged between 1.7% and 2.8% from 2015 to 2020 [2]. The situation deteriorated further during the COVID-19 pandemic, with operating room case volumes in the United States decreasing by around 35% between March and July 2020 compared to the prior year [3]. Such disruptions, which affected most medical and diagnostic services, created significant backlogs, requiring hospitals to operate at 120% of historical throughput for ten months to recover just two months of additional surgical demand.

To try and mitigate this situation, decision-support tools have been proposed and deployed to support activities related to the delivery of health services. Aiming at reducing clinicians’ workload and increasing the efficiency of administrative tasks, these tools have shown potential in predicting patients’ health trajectories, recommending treatments, guiding surgical care, monitoring patients, and supporting efforts to improve population health. However, as pointed out by [4], “innovations in medications and medical devices are required to undergo extensive evaluation, often including randomized clinical trials, to validate clinical effectiveness and safety.” Similar rigor should apply to decision-support tools, especially when integrated into complex healthcare systems where multiple stakeholders, dynamic interactions, and contextual constraints can lead to unintended consequences.

In this context of higher demand and longer waiting times, the need for Computer-Based Patient Prioritization Tools (PPT) has accelerated. PPTs aim to manage access to care by ranking patients equitably and rigorously based on clinical criteria so that those with urgent needs receive services before those with less urgent needs. While PPTs have been widely studied, few works have explored their real-world implementation and, more importantly, the constructs determining successful adoption in clinical practice [5,6]. The development of such tools follows an iterative life cycle—design, implementation, verification, validation, and deployment—where verification and validation (V&V) play a critical role in ensuring reliability, safety, and user trust [7,8].

Recent studies on the acceptability of new technologies in healthcare show that a substantial proportion of users remain hesitant toward AI-based solutions, mainly due to concerns about accuracy and security. This highlights the importance of robust verification and, even more specifically, validation processes before deployment in complex healthcare environments [9].

This paper presents and discusses the validation process of a PPT as part of its development life cycle. It follows the more technical, software-oriented verification process performed after the construction of the prototype and it can be considered an early stage of implementation. Validation aims to demonstrate how the tool can deliver improved outcomes while avoiding unintended consequences when integrated into a complex healthcare system characterized by multiple stakeholders, interdependent processes, and resource constraints. Such complexity amplifies the risk of emergent behaviors and unintended effects, making rigorous validation essential before large-scale deployment. The PPT was designed to manage patients’ access to the urodynamic test (UT) in the urology service at the Hospital de Clínicas of the Federal University of Paraná, Brazil [10,11]. The UT is an interactive diagnostic study of the lower urinary tract, essential for diagnosing conditions such as urinary incontinence and neurogenic bladder [12].

At the Hospital de Clínicas of the Federal University of Paraná, the waiting list for the UT has grown dramatically, exceeding 3000 patients with an average waiting time of three years. The list was managed manually using an Excel spreadsheet, with no formal method for selecting patients. In practice, prioritization depended on residents, who informed administrative staff which patients they believed should be scheduled for the exam. The absence of structured criteria created several issues: patients who had already undergone other treatments, older patients, and even deceased patients remained on the list because there was no routine process for updating or removing cases. Patients who returned to the clinic with worsening symptoms were usually prioritized, introducing a bias linked to the frequency of follow-up visits. Conversely, patients with urinary incontinence—particularly women—often remained on the list indefinitely, as their condition was perceived as non-urgent. This lack of standardization resulted in prolonged waiting times and inequities in access to care, highlighting the need for a systematic and transparent prioritization approach. These challenges justified the development of a PPT that, if not reducing the average waiting time, could at least support managers in prioritizing patients based on clinical urgency, ensuring transparency, consistency, and fairness in the decision-making process [6].

This paper is structured as follows: the next section presents a literature review on PPT, followed by a methodological section that introduces the development of the PPT designed for managing the prioritization of access to UT, and the process proposed for its validation. Then, results are presented and discussed. Conclusions, further research avenues, and limitations of this work conclude the paper.

2. Literature Review on Patients’ Prioritization Tools

Over the past decades, waiting lists have expanded significantly due to a combination of structural and demographic pressures. Rising demand for healthcare services—driven by population aging, the growing prevalence of chronic diseases, and advances in medical technology—has outpaced the capacity of health systems to deliver timely care. At the same time, resource constraints, including workforce shortages and limited infrastructure, have exacerbated this imbalance, making waiting lists a persistent challenge worldwide.

In response, many countries have undertaken various strategies to reduce waiting times. These interventions typically target either demand, supply, or both. On the demand side, cost-sharing mechanisms have been proposed to curb excessive utilization; however, such measures are widely regarded as inequitable and unpopular. On the supply side, persistent shortages of healthcare personnel and funding constraints remain significant barriers to expanding service capacity. Even more, studies have reported moderate success when dedicated funding envelopes were allocated to reduce specific waiting lists [13]. Beyond these measures, efforts have also focused on improving efficiency within existing resources. Drawing inspiration from lean thinking—particularly the principles of the Toyota Production System—many hospitals have adopted process improvement strategies over the past decade to streamline workflows and ultimately reduce delays.

In contrast to these approaches aimed at increasing capacity or curbing demand, patient prioritization seeks to optimize access by ensuring that those with the greatest need are treated first. The complexity of assessing, ranking, and managing patients on waiting lists has led to the development of PPTs. These tools are intended to assist decision-makers in determining which patients should be scheduled when demand exceeds available capacity. Typically, PPTs employ a weighted set of criteria, allowing each patient to be evaluated against predefined factors. The cumulative score derived from these criteria enables systematic ranking and supports resource allocation decisions [5,14]. PPTs have attracted considerable attention for their potential to promote fairness, transparency, consistency, and efficiency—four foundational principles for managing waiting lists and ensuring equitable access to healthcare services [15,16].

The criteria used in PPTs vary depending on the clinical context but commonly include personal factors (e.g., age), social factors (e.g., ability to work), clinical indicators (e.g., quality of life, severity of condition), and other context-specific elements [17,18]. This contextual dependency has led to a lack of standardization across tools, as highlighted in several studies [19,20].

Precisely, selecting the appropriate criteria and determining their relative importance constitute one, if not the most challenging aspect in the development of PPTs. The choice of criteria must reflect both clinical relevance and ethical considerations, yet there is no universal consensus on which factors should be prioritized. Studies have shown that criteria such as pain intensity, functional limitations, disease progression, and social roles are commonly used, but their inclusion and evermore, the weight they receive, vary significantly across tools and contexts [5,14,17]. This lack of standardization in criteria and objectives complicates comparisons between systems and may affect the fairness and transparency of prioritization decisions.

In recent years, ethical dimensions are increasingly integrated into prioritization frameworks. Some authors argue that prioritization should not solely rely on clinical urgency but also consider equity, social vulnerability, and moral responsibility [21,22]. Moreover, assigning weights to each criterion—a process often based on expert consensus, statistical modeling, or decision-making frameworks like the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP)—introduces further complexity. The relative importance of criteria can be influenced by clinical urgency, patient-reported outcomes, and societal values, making the weighting process inherently subjective [23]. Furthermore, participatory modeling approaches involving stakeholders have been proposed to ensure legitimacy and inclusiveness in decision-making [21]. For instance, some tools rely on participatory approaches involving clinicians and patients to establish consensus, while others use simulation or AI-based models to optimize scoring systems. Despite these efforts, the challenge remains to balance clinical objectivity with ethical sensitivity, ensuring that prioritization tools are both effective and just.

Examples of scoring systems illustrate how PPTs operate in practice. For example, the Western Canada Waiting List Project developed tools for various specialties, including hip and knee arthroplasty, cataract surgery, and mental health services. These tools use point-count systems, where each criterion is assigned a numerical value, and the total score determines the patient’s priority level [15,16,24]. In orthopedic surgery, the WOMAC index evaluates pain, stiffness, and physical function, producing a score from 0 to 100. Patients are then categorized into urgency groups [5]. Similarly, the Obesity Surgery Score (OSS) incorporates BMI, obesity-related comorbidities, and functional limitations to identify high-risk patients and prioritize bariatric surgery [25].

Efforts have also been made to develop generic tools applicable across elective procedures. One such tool evaluates patients based on clinical and functional impairment, expected benefit, and social role, encompassing subcriteria like disease severity, pain, progression rate, daily activity limitations, and caregiving responsibilities [20]. The Surgical Waiting List Info System (SWALIS) project in Italy exemplifies a national initiative to standardize prioritization across surgical services. It provides real-time data to monitor waiting lists and supports equitable and efficient resource management [26].

Despite the potential benefits of patient prioritization tools, their implementation in clinical settings is scarce and faces several barriers. Organizational resistance to change, limited staff training, and concerns about the accuracy and fairness of scoring systems can hinder adoption [6]. Healthcare professionals may be skeptical of algorithm-based decisions, especially when ethical considerations and patient preferences are not adequately addressed [21]. A critical barrier is the issue of user trust—clinicians and administrators may hesitate to rely on prioritization tools if they perceive them as opaque or unreliable. This lack of trust can significantly impede integration into routine practice. However, rigorous validation processes, including assessments of reliability, validity, and clinical relevance, can help mitigate this barrier by demonstrating the tool’s effectiveness and legitimacy [17,18]. Technical challenges, such as integrating prioritization tools into existing electronic health record systems, also pose significant obstacles. Moreover, the lack of standardized protocols and the need for continuous validation of the tools across diverse clinical contexts complicate their widespread use [22]. Addressing these barriers requires participatory implementation strategies, ongoing evaluation, and institutional support to ensure that prioritization tools are effectively and ethically integrated into healthcare workflows.

Although PPTs have been widely discussed in the literature for their conceptual and methodological merits, evidence of rigorous validation and verification remains scarce. The reviewed studies emphasize theoretical frameworks or propose algorithmic models, and only a few of them conduct evaluations in real-world clinical environments. This gap raises concerns about the reliability, generalizability, and practical applicability of these tools. This paper proposes and illustrates a validation process for a patient prioritization tool, emphasizing that rigorous validation—through reliability testing, stakeholder engagement, and contextual adaptation—is key to fostering trust and facilitating successful implementation in clinical practice.

3. Methods

This section begins by providing background on the development of the Patient Prioritization Tool (PPT) for urodynamic testing, followed by a description of the iterative validation process designed to assess its reliability and clinical relevance. A comprehensive account of the tool’s development and verification lies beyond the scope of this paper; interested readers are referred to [10,11] for a detailed explanation. Nevertheless, a brief overview of the tool’s structure and underlying principles is essential to contextualize the validation approach presented herein.

3.1. A PPT for Managing Access to Urodynamic Test

Decision problems in healthcare are inherently complex, involving multiple stakeholders, interdependent processes, and evolving patient conditions. Managing access to UT exemplifies this complexity, as it constitutes a multicriteria decision problem with clinical, operational, and ethical dimensions. To address these challenges, a multidisciplinary team—including urologists, nurses, mathematicians, and engineers—was formed to design and implement a PPT [10,11].

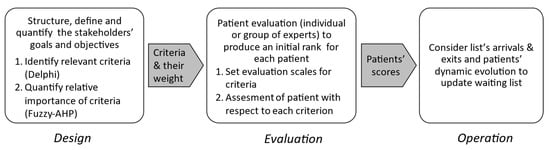

The tool’s development followed three main steps reported in Figure 1, which correspond to the Design, Evaluation, and Operation phases. In the first step, Design, experts identify and agree on relevant criteria for prioritization using consensus methods such as Delphi or the Technique for Research of Information by Animation of a Group of Experts (TRIAGE) [27]. A hybrid fuzzy AHP technique is then applied to quantify the relative importance of each criterion following the structure given in [28]. At the end of the Design phase, a set of criteria , as well as a vector containing the weight of each criterion such that and .

Figure 1.

A general framework for PPT design and operation.

The second step, Evaluation, encompasses two activities. First, an evaluation scale is established for each criterion. Some scales are standardized (e.g., numerical pain assessment), while others are designed by experts according to their clinical experience and the expected range of values for each criterion. Then, each patient is assessed by one or several experts. against each criterion using these scales. As a result, a global score is computed for each patient, and the waiting list is sorted accordingly, with higher scores indicating greater urgency.

In the third and last step, Operation, the ranked list is translated into service delivery schedules, considering practical and administrative constraints. These constraints make it almost impossible to treat patients in the exact order established by the patients’ scores, so an optimization tool is needed to elaborate service delivery schedules (see, for example, [29]). Furthermore, waiting lists are dynamic so that new patients arrive while others quit the system once they have received the required service. Finally, a patient may evolve very fast, so his position on the waiting list must be reevaluated upon a change in his situation.

3.2. Verification and Validation

Verification and Validation (V&V) are fundamental concepts in many disciplines. In this paper, V&V are explicitly defined in the context of software development and computer simulation, which is the relevant scope for our work. In this context, V&V are used to establish the credibility of models and simulations. V&V is a process aiming to demonstrate that a computer simulation model adequately mirrors its real or conceptual counterpart and, even more important, that the results and insights extracted by experiments carried on the simulation model can be trusted as they would have been obtained from the real or conceptual artifact. Inspired by this interpretation, we adopted a similar process for developing and deploying PPTs within a complex healthcare environment.

Verification refers to the process of confirming, through objective evidence, that a system or tool meets its specified requirements and design specifications (International Organization for Standardization, ISO 9000 [30]). In the context of software-based decision-support systems, verification ensures that the technical and functional characteristics of the tool—such as algorithms, scoring mechanisms, and data handling—are implemented correctly, without assessing their clinical usefulness. In other words, verification ensures that the conceptual model is correctly implemented in software, free of logical or coding errors. This step typically involves rigorous testing, inspections, and documentation to demonstrate internal consistency and compliance with regulatory or design criteria. Unlike validation, which evaluates whether the tool fulfills its intended purpose in real-world settings, verification focuses on “building the product right” rather than “building the right product”. Establishing robust verification protocols is essential to ensure reliability and safety before deployment in clinical environments.

In software development and computer simulation, validation involves empirical testing, pilot implementations, and comparative studies to evaluate performance under practical constraints. Robust validation is essential to ensure that the developed decision-support tools are not only correctly built but also clinically useful, safe, and acceptable to stakeholders before widespread adoption. However, even when these internal processes are completed, the ultimate value of any decision-support tool depends on user confidence and acceptance—especially in complex systems where multiple stakeholders interact. This final step, often referred to as accreditation or certification, aims to demonstrate to end-users that the tool is reliable and fit for its intended purpose.

This paper focuses on the validation that follows the verification phase, within the software development and simulation framework. Specifically, the validation process involves comparing the tool’s behavior with expert judgment under controlled conditions. Furthermore, prototype validation is one of the key categories of software validation techniques identified in the literature [31]. Nevertheless, methodological guidance details for prototype validation remain limited, and its implementation must consider the software domain, quality requirements, and the specific utilization context.

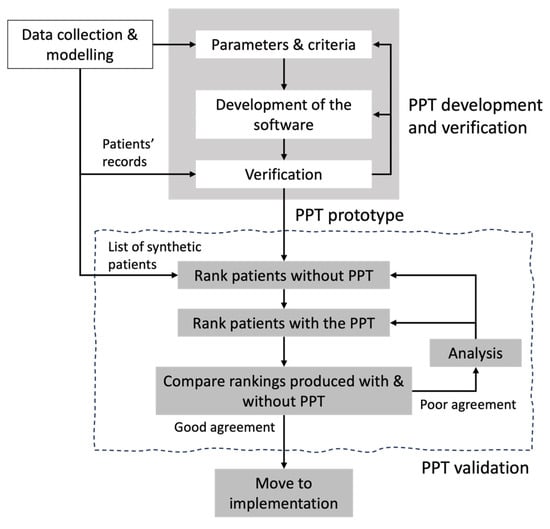

We propose a holistic, expert-driven iterative validation process illustrated in Figure 2. This approach acknowledges the inherent complexity of healthcare systems and the need for iterative refinement to align algorithmic logic with clinical reasoning.

Figure 2.

Process proposed for the Verification and Validation of the PPT.

The empirical validation process begins by generating a representative set of patients to prioritize. Selecting appropriate test data is critical: if the data set does not reflect the intended application, conclusions about the model’s suitability and quality may be misleading, potentially restricting its use. Moreover, according to recent research, synthetic data offers several key advantages over actual historical patients’ records, mainly related to privacy and confidentiality protection—synthetic data does not have a one-to-one mapping to the original data or to real patients [32,33]. This choice is consistent with best practices in software development and simulation, where synthetic datasets are commonly used to ensure privacy while enabling robust testing. Then, the iterative validation process starts. In the absence of a “gold standard” for patient prioritization—a common challenge in complex healthcare systems—we compare the rankings produced by the PPT with those generated by domain experts. Therefore, in the first step, experts are required to individually read the patients’ files and rank the patients according to their priority. Then, each expert will use the PPT to rank again the patients.

In the second step, the agreement between the ranks is evaluated. To measure the agreement between any two lists or rankings and having each objects (patients in our case), we compute both the Average Spearman footrule distance [34] and the Spearman correlation [35,36]. The Average Spearman distance is defined as the sum, over all the patients , of the absolute differences between the ranks of each patient in the two complete lists:

where , or simply , ranges from 0 (perfect agreement) to (complete disagreement). The Spearman correlation is a nonparametric version of the Pearson correlation that measures the strength and direction of a monotonic relationship between the ranks of data. It can be any value from −1 to 1, and the closer the absolute value of the coefficient to 1, the stronger the relationship, with 1 indicating a perfect positive correlation, −1 a perfect negative correlation, and 0 no correlation. If there are no tied ranks, the following simpler formula allows to compute :

To test the agreement between the experts and the PPT’s rankings, we proceed as follows. We compare the ranks produced by the experts to assess inter-expert agreement and confirm whether they share similar goals and criteria. We also compare the rankings generated by the tool—one based on each expert’s assessments. Each PPT ranking is compared to the corresponding expert ranking, and the two PPT rankings are compared to assessing robustness. If the agreement is high, the process stops. Otherwise, discrepancies are analyzed collaboratively with experts, and if necessary, PPT parameters (i.e., weights granted to the criteria) may be adjusted.

This iterative, expert-driven approach is particularly valuable in complex systems where no objective benchmark exists. It not only validates the conceptual logic of the PPT but also fosters user confidence by involving experts in refining the tool. Ultimately, this validation process complements prior verification steps and strengthens the readiness of the PPT for real-world deployment.

4. Results

This section reports the application of the proposed validation methodology to the PPT for managing access to urodynamic tests. The application of the validation process followed the next main steps. First, a synthetic dataset of patients was generated to simulate real clinical scenarios. Second, two experts independently evaluated each patient within the PPT according to the predefined criteria and scales established during the Design phase (see [10,11]). Performing these evaluations directly in the PPT ensured the independence of each expert’s judgment while reinforcing the robustness of the results by incorporating multiple expert opinions (in our case, two). Third, the prioritization tool (PPT) computed a ranking of patients based on these evaluations and the weights previously assigned to each criterion, as described in [10,11]. Subsequently, each expert produced an individual ranking of the same patients according to their clinical judgment. Then the validation process begins. In this process, the concordance between the rankings generated by the PPT (using the experts’ evaluations) and those produced manually by the experts is evaluated and discrepancies are analyzed collaboratively with experts. If discrepances show that criteria in the PPT are not aligned with experts’, the PPT parameters (i.e., weights granted to the criteria) may be adjusted. These steps are detailed in the following subsections.

Data collection for testing. The process began with the generation of ten synthetic patients by a nurse from the outpatient clinic of urinary dysfunction. The sample size was small to allow manual ranking by physicians while ensuring diversity in terms of pathologies, signs, and symptoms—an essential consideration in complex healthcare systems where patient heterogeneity significantly impacts prioritization.

Two complementary data sources were used: (i) existing clinical records, including the date of the patient’s first consultation, socio-economic characteristics, and previous test results; and (ii) patient responses to a questionnaire based on the uro-functional classification. Data collection spanned three weeks, as patients were encouraged to provide detailed narratives of their conditions.

To facilitate expert evaluation, a researcher transcribed the collected information into narrative-style patient histories, including names (fictional), age, gender, occupation, test results, and relevant clinical details. This format was chosen to mirror the physicians’ usual workflow, making the evaluation process as realistic as possible. An example of such a record is provided below.

“A female patient, 25 years old, neurogenic bladder due to congenital spinal cord injury, reports having a great loss in work activity due to the disease, has no dependents, lives with her mother. The patient retired due to disability. She reports a large amount of urine loss all the time. She waits in line for 14 months to perform Urodynamics. No renal disease, normal USG, creatinine of 0.3, and oxybutynin with significant improvement of symptoms. ICIQ = 21.”

Test of agreement—Round one. The ten patients’ records (P01 to P10) were submitted to two experts who individually ranked them. To minimize potential bias, the files were presented in random order, and experts were instructed not to communicate during the evaluation. The first expert was the urodynamics doctor’s chief, and the other was a resident urologist. Both experts had participated in the Design step, contributing to the identification of the relevant criteria and the quantification of their relative importance. We will refer to the ranks produced by the urodynamics’ chief and by the resident as and , respectively.

Next, both experts assessed each patient according to the criteria and scales defined in the PPT (see step two, Evaluation, in the previous subsection). Based on these evaluations, the PPT generated two rankings: (using expert ’s assessments) and (using expert ’s assessments). Patients were sorted by their computed scores, with higher scores indicating greater urgency. The agreement metrics and were computed between and to assess the inter-rated agreement, and between the two ranks produced by each expert (i.e., manually and using the PPT). Finally, we also computed the values of the metrics between the two ranks produced using the PPT. Table 1 reports the results. Each line gives the ranking of each patient P01 to P10 in a prioritized list (lines , , and ). The right part of the table reports the values of the agreement metrics between the lists. For instance, the value of the Spearman average distance between list and list , , is given under header . Notice that since then .

Table 1.

Rankings and agreement metrics after the first prioritization round.

The comparisons provide insights into the alignment between expert judgment and the tool’s logic, as well as the tool’s robustness when fed with different expert inputs. Table 1 shows that the rankings produced by both experts are quite similar, with agreement values of and . Although both experts work within the same service, slight differences in their interpretation of patient histories prevent a perfect match. In practice, it is unlikely that two experts will produce identical rankings. For this reason, we accept as a high agreement rate and adopt this value as a baseline for comparison. The two rankings produced by the PPT also exhibit good agreement, with distances and , slightly worse than our baseline. However, when comparing the rankings produced by experts and to those generated by the PPT based on their assessments ( and , respectively), the differences are substantial. Specifically, the values of and rise to and , respectively, and we observe a similar deterioration in and , that produced values of and , respectively.

In summary, there is a strong agreement between the rankings produced by the two experts, but significant divergence from the PPT-generated rankings. Since the two PPT rankings are relatively consistent, further investigation was required to identify the reasons for these discrepancies and to determine corrections to the PPT if needed.

Analysis round one. The two experts (the chief and the resident) participated in a meeting with the research team to discuss how they assessed and prioritized the patients in the test set, and to identify the factors explaining the differences between their rankings and those produced by the PPT.

We began by examining patients whose positions differed most between the manual and PPT-generated lists. This analysis revealed that patients with neurogenic bladder were assigned lower priority in the manual rankings compared to the PPT rankings. Neurogenic bladder is recognized as a primary risk factor for kidney complications, and the experts acknowledged its high importance in the prioritization process. They realized that this aspect—particularly creatinine levels—had been undervalued in their manual assessments, whereas the PPT had appropriately weighted it during evaluation.

Test of agreement—Round two. Based on the results of the analysis, we did not find reason to modify the PPT. However, the experts were invited to reconsider their rankings using any methodology they deemed appropriate. In this second round, the experts decided to work together, adopting a two-step approach. First, they categorized patients into three priority groups—high, medium, and low—and then they ranked the patients within each group. In this revised classification, patients with neurogenic bladder were assigned to the high-priority category; those with Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH) to the medium-priority category; and patients with Urinary Incontinence Refractory (UIR) and other conditions to the low-priority category. Within each category, patients were ordered based on their risk of developing kidney disease.

The experts revisited the patient histories, prioritizing first according to kidney function parameters (creatinine). When renal function was similar between two patients, the underlying condition served as the secondary criterion. For example, between a patient with BPH and another with neurogenic bladder—both with similar renal function—the latter was prioritized due to the higher risk of sudden renal complications. At the end, the experts produced a new joint ranking referred to as . Table 2 presents this ranking and the agreement metrics and computed between and and , the rankings generated by the PPT in the first round using the assessments of the Chief and the Resident, respectively.

Table 2.

Rankings and agreement metrics after the second prioritization round.

The results indicate that ranking is closer to the ones produced by the PPT. Indeed, is closer to than , suggesting that the Resident’s assessments were less accurate. Nevertheless, the distances still reflect low agreement.

Analysis round two. A new look at the experts’ ranking showed that patient P06 was the main reason for the discrepancy with the ranking . We thus analyzed the patient P06 history in more detail, and we discovered that P06 had been classified as having kidney disease, although the actual patient’s condition—renal cyst grade I—was not of clinical relevance. This can be considered an error or inaccuracy of the data. We corrected the assessment of P06 with respect to this criterion in the PPT and a third round was launched.

Test of agreement—Round three. In this third round, we consider ranking E produced jointly by the experts during round two and a new ranking, referred to as , produced by the two experts using the PPT. Ranking E and the agreement metrics with respect to are reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

Rankings produced after correction of P06’s data.

The updated ranking demonstrated substantial convergence with the experts’ ranking, leading to values of 1.2 and 0.842 for the agreement metrics and , which confirms a good agreement.

Analysis round three. It is noteworthy that patient P01, diagnosed with neurogenic bladder, was initially poorly prioritized by both the experts and the PPT. Although this patient had normal test results, annual follow-up was necessary to prevent kidney damage due to spinal disease. Consequently, the physicians decided to place this patient on a separate list for periodic examinations. The ranking of the PPT was manually adjusted to reflect this decision.

Final analysis. The final rankings, presented in Table 4 achieved agreement distances of , which matches our baseline for , and , which is very close to 1. Importantly, both experts deemed the final PPT ranking () as reasonable as their own, and expressed confidence in the tool, confirming their willingness to adopt it in practice.

Table 4.

Final rankings and agreement metrics.

5. Discussion

The primary objective of the validation process was to ensure that the behavior of the PPT aligns with the prioritization logic defined by the experts during the design phase. In pursuing this goal, the process revealed certain inconsistencies between the agreed weighting framework and the experts’ individual decision-making practices. Although the experts had reached consensus on the relative importance of the different criteria, this agreement did not fully translate into their manual rankings. When prioritizing patients individually, each expert tended to deviate from the agreed weighting logic, suggesting that cognitive biases and contextual factors influence decision-making even when predefined priorities are clear. This reinforces the need for structured tools such as PPT to ensure consistency and adherence to the intended prioritization framework.

Specifically, the analysis of the initial discrepancies between manual and PPT rankings led experts to conclude that they did not give neurogenic bladder sufficient relevance in their assessments, even though its importance was acknowledged during the design phase. The experts adapted their approach to ensure adequate consideration of neurogenic bladder, and the experiments demonstrated that the distance between their second ranking and the PPT’s ranking was significatively reduced.

Applying all relevant criteria consistently across multiple patients also proved challenging. To mitigate this difficulty, experts changed their ranking strategy: patients were first separated into priority groups and then sorted within each group. Using this approach, they produced a new ranking that was extremely close to the PPT’s, particularly for high- and low-priority patients, while medium-priority patients were ranked similarly.

Finally, discrepancies concerning patient P06 allowed the team to identify a data error. After correcting this error, the agreement between the manual and PPT rankings reached values that can be considered as excellent.

The validation process provided valuable insights into the challenges and complexities associated with expert-based evaluation. By analyzing and comparing their own rankings with those generated by the PPT, the experts were prompted to reconsider not only the relative importance assigned to each criterion but also the relevance of certain criteria in practice. During this process, the experts recognized a potential gap between the importance they believed a criterion should have and the actual weight it received in their decision-making. This observation underscores the cognitive limitations inherent in complex, multicriteria decision contexts and highlights the value of systematic approaches such as PPT. Both experts acknowledged that maintaining stability and consistency in applying criterion weights is a key feature of the tool. Ultimately, the experts expressed strong confidence in the PPT’s results and endorsed its practical implementation, recognizing its potential to enhance transparency, fairness, and reliability in patient prioritization.

Beyond validating the PPT’s performance, the process itself provided a structured framework for expert reflection and iterative improvement. The application of the process involved several key steps: first, experts compared their initial manual rankings with the PPT-generated ranking, which highlighted discrepancies and prompted discussion about the interpretation of criteria. Second, adjustments were made to ensure that critical clinical factors, such as neurogenic bladder, were adequately weighted. Third, experts adopted a grouping strategy to simplify ranking, which improved alignment with the PPT and reduced cognitive load. These steps illustrate how the process not only validated the tool but also served as a learning mechanism, enabling experts to refine prioritization practices and uncover systemic weaknesses in referral pathways. This iterative approach demonstrates the practical value of combining quantitative methods with expert judgment to achieve more equitable and transparent decision-making.

When asked to summarize his impressions about the development of the PPT for helping to manage the access to the urodynamic test, the chief of urology service answered: “This research prompted a critical reassessment of the urodynamic examination process, from patient indication to service delivery. By engaging physicians in reflective analysis, the study exposed weaknesses in the referral and prioritization mechanisms, encouraging the health system to adopt a more structured and equitable approach. This included recognizing that time of arrival in the waiting list should not be the sole criterion for care allocation, as medical urgency and social context must also be considered.

The findings led to concrete management improvements. The hospital redefined its patient flow, distinguishing those who truly required urodynamic testing from those who could benefit from alternative, conservative treatments such as physiotherapy or pessaries. This process fostered a more efficient and fair use of resources and deepened the organization’s understanding of equity, prioritization, and patient-centered care within the public health context.

6. Conclusions

This paper illustrates and discusses the validation process designed to assess the extent to which a Computer-Based Patient Prioritization Tool (PPT), conceived to manage patients’ access to the urodynamic test in the urology service at the Hospital de Clínicas of the Federal University of Paraná, Brazil, can produce outcomes that meet experts’ requirements before its potential implementation. Validation plays a critical role in the development life cycle of decision-support tools, especially in complex healthcare systems where multiple stakeholders, interdependent processes, and resource constraints can lead to unintended consequences if tools are not rigorously tested.

The proposed validation process aimed to identify and explain differences between prioritization decisions made by experts and those generated by the PPT, ultimately assessing the level of trust that can be placed in the tool. Through a series of recursive tests, disagreements were quantified using the Average Spearman footrule distance and the Spearman correlation coefficient. Initial results revealed strong agreement between experts but significant divergence from the PPT. However, this process uncovered both human and data-related issues: experts adjusted their weighting of criteria, and a data error was corrected. After these refinements, the disagreement decreased substantially to reach distances that confirm a very good agreement between the rankings, confirming the tool’s excellent performance. These results demonstrate that the PPT can reliably reproduce expert consensus and ensure consistency in prioritization decisions.

Beyond validating the PPT, this iterative process demonstrated its methodological value as a structured approach for aligning expert judgment with algorithmic logic and improving decision-support tools through feedback loops. From a practical perspective, the study contributed to enhancing transparency and fairness in patient prioritization, fostering user confidence, and prompting organizational changes in referral practices. These findings highlight the importance of structured validation in bridging the gap between research prototypes and real-world implementation in complex healthcare environments.

Despite the promising results, the validation process carried out has some limitations. First, the test set of 10 patients does not capture the full diversity of clinical profiles and scenarios. Larger and more heterogeneous samples are needed to confirm the tool’s robustness before practical implementation. Additionally, the patient descriptions used in the tests were synthesized from two sources—clinical records and patient questionnaires—and transcribed by a nurse into historical-like records, which may have homogenized and, potentially, introduced a bias in the information presented to experts. Future tests should involve real patient data to minimize potential bias introduced during test case preparation.

A second limitation concerns variability in expert opinions. The experiments involved two experts from the same service, whose rankings were highly consistent. However, other experts might produce more divergent rankings. Since the PPT design averages expert opinions, it is possible that some experts could reject rankings, including those generated by the tool. This highlights the importance of internal communication and change management during implementation. Stakeholders must understand that PPT rankings will approximate expert consensus but will not replicate any individual expert’s decisions. Finally, communication strategies should emphasize the benefits of standardized criteria and evaluation as a means to achieve fairness and transparency in access to healthcare services.

Future work will focus on expanding the test set, involving multiple experts from different institutions, and conducting real-world pilot studies to assess the tool’s performance in a complex healthcare environment. These steps are essential to strengthen trust, ensure scalability, and support the transition from prototype to practice.

Author Contributions

A.T.L.P., M.-E.L., R.d.F., A.R. and J.E.P.J. participated to the conception of the work. A.T.L.P., M.-E.L., A.R., J.D. and J.E.P.J. researched literature. A.T.L.P., R.d.F., J.R.F. and J.E.P.J. performed the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work. A.T.L.P. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors revised the first draft critically for important intellectual content. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Fonds de recherche du Québec Nature et Technologie [grant number 2018-PR-20810].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The ethics committee of The UFPR-Hospital de Clínicas da Universidade Federal do Paraná, Brazil, approved this study (CAAE: 85051918.2.0000.0096).

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data. Data were obtained from The UFPR-Hospital de Clínicas da Universidade Federal do Paraná, Brazil. Access to data requests should be addressed directly to the UFPR-Hospital de Clínicas da Universidade Federal do Paraná.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Administração Central do Sistema de Saúde. Relatório Anual Sobre o Acesso a Cuidados de Saúde nos Estabelecimentos do SNS e Entidades Convencionadas. ACSS 2019. Available online: https://www.ulssm.min-saude.pt/media/k2/attachments/administracao/Relatorio%20Anual%20sobre%20o%20Acesso%20a%20Cuidados%20de%20Saude_2019.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Elective Surgery Access (n.d.). Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/hospitals/topics/elective-surgery/waiting-times (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Berlin, G.; Bueno, D.; Gibler, K.; Schulz, J. Cutting Through the COVID-19 Surgical Backlog. 2020. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/cutting-through-the-covid-19-surgical-backlog# (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Maddox, T.M.; Rumsfeld, J.S.; Payne, P.R.O. Questions for Artificial Intelligence in Health Care. JAMA 2019, 321, 31–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCormick, A.D.; Collecutt, W.G.; Parry, B.R. Prioritizing Patients for Elective Surgery: A Systematic Review. ANZ J. Surg. 2003, 73, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Déry, J.; Ruiz, A.; Routhier, F.; Bélanger, V.; Côté, A.; Ait-Kadi, D.; Gagnon, M.P.; Deslauriers, S.; Pecora, A.T.L.; Redondo, E.; et al. A Systematic Review of Patient Prioritization Tools in Non-Emergency Healthcare Services. Syst. Rev. 2020, 9, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burstein, F.; Holsapple, C. Handbook on Decision Support Systems 1: Basic Themes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Musen, M.A.; Middleton, B.; Greenes, R.A. Clinical Decision-Support Systems. In Biomedical Informatics: Computer Applications in Health Care and Biomedicine; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 795–840. [Google Scholar]

- Nadarzynski, T.; Miles, O.; Cowie, A.; Ridge, D. Acceptability of Artificial Intelligence (AI)-Led Chatbot Services in Healthcare: A Mixed-Methods Study. Digit. Health 2019, 5, 205520761987180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pécora, A.T.L.; De Fraga, R.; Ruiz, A.; Frega, J.R.; Pécora, J.E. Project Planning for Improvement in a Healthcare Environment: Developing a Prioritization Approach to Managing Patients’ Access to the Urodynamics Exam. J. Mod. Proj. Manag. 2021, 8, 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Pecora, A.T.L. Criação de Score Urofuncional Para Priorização de Pacientes Na Fila Do Estudo Urodinâmico Do Hospital de Clínicas Da Universidade Federal Do Paraná. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Federal Do Paraná Curitiba, Curitiba, Brazil, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, C.W.; Winters, J.C. AUA/SUFU Adult Urodynamics Guideline. Urol. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 41, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellan, L. Changes in waiting lists over time. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2008, 43, 547–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, K.E.; Taylor, N.; Shaw-Stuart, L. Triaging patients for allied health services: A systematic review of the literature. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2009, 72, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hador, D.C. The Steering Committee of the Western Canada Waiting List Project Setting Priorities for Waiting Lists: Defining Our Terms. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2000, 163, 857. [Google Scholar]

- Noseworthy, T.; McGurran, J.; Hadorn, D. Waiting for scheduled services in Canada: Development of priority-setting scoring systems. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2003, 9, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allepuz, A.; Espallargues, M.; Moharra, M.; Comas, M.; Pons, J.M. Prioritisation of patients on waiting lists for hip and knee arthroplasties and cataract surgery: Instruments validation. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2008, 8, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, A.; Gonzalez, M.; Quintana, J.M.; Bilbao, A.; Ibanez, B. Validation of a prioritization tool for patients on the waiting list for total hip and knee replacements. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2009, 15, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, J.M.; Escobar, A.; Bilbao, A.; Ibanez, B.; Arenaza, J.C. Development of explicit criteria for prioritization of hip and knee replacement. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2007, 13, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solans-Domènech, M.; Adam, P.; Tebé, C.; Espallargues, M. Developing a Universal Tool for the Prioritization of Patients Waiting for Elective Surgery. Health Policy 2013, 113, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiebe, K.; Kelley, S.; Fecteau, A.; Levine, M.; Blajchman, I.; Shaul, R.Z.; Kirsch, R. Operationalizing Equity in Surgical Prioritization. Can. J. Bioeth. 2023, 6, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haustein, T.; Jox, R.J. Allocation of Treatment Slots in Elective Mental Health Care—Are Waiting Lists the Ethically Most Appropriate Option? Am. J. Bioeth. 2024, 25, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frichi, Y.; Aboueljinane, L.; Jawab, F. Using discrete-event simulation to assess an AHP-based dynamic patient prioritisation policy for elective surgery. J. Simul. 2023, 19, 39–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantini, M.P.; Negro, A.; Accorsi, S.; Cisbani, L.; Taroni, F.; Grilli, R. Development and assessment of a priority score for cataract surgery. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2004, 39, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, J.A.C.; Quesada, C.F.; Marco, M.d.V.G.; González, I.A.; Benavides, F.C.; Ponce, J.; Velasco, P.d.P.; Gómez, J.M. Obesity Surgery Score (OSS) for Prioritization in the Bariatric Surgery Waiting List: A Need of Public Health Systems and a Literature Review. Obes Surg. 2018, 28, 1175–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, R.; Testi, A.; Tanfani, E.; Fato, M.; Porro, I.; Santo, M. A model to prioritize access to elective surgery on the basis of clinical urgency and waiting time. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2009, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, S.A.; Dery, J.; Lamontagne, M.-E.; Jamshidi, A.; Lacroix, E.; Ruiz, A.; Ait-Kadi, D.; Routhier, F. Prioritization of patients access to outpatient augmentative and alternative communication services in Quebec: A decision tool. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2020, 17, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, S.A.; Jamshidi, A.; Ruiz, A.; Ait-Kadi, D. A new dynamic integrated framework for surgical patients’ prioritization considering risks and uncertainties. Decis. Support Syst. 2016, 88, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.; Bélanger, V.; Marques, I.; Ruiz, A. Assessing the impact of patient prioritization on operating room schedules. Oper. Res. Health Care 2020, 24, 100232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quality Management Principles; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; ISBN 978-92-67-10650-2.

- Atoum, I.; Baklizi, M.K.; Alsmadi, I.; Otoom, A.A.; Alhersh, T.; Ababneh, J.; Almalki, J.; Alshahrani, S.M. Challenges of Software Requirements Quality Assurance and Validation: A Systematic Literature Review. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 137613–137634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajotte, J.; Bergen, R.V.; Buckeridge, D.L.; El Emam, K.; Ng, R.; Strome, E. Synthetic data as an enabler for machine learning applications in medicine. iScience 2022, 25, 105331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezoulas, V.C.; Zaridis, D.I.; Mylona, E.; Androutsos, C.; Apostolidis, K.; Tachos, N.S.; Fotiadis, D.I. Synthetic data generation methods in healthcare: A review on open-source tools and methods. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2024, 23, 2892–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaconis, P. Group Representations in Probability and Statistics. Lect. Notes-Monogr. Ser. 1988, 11, i-vi+1-192. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4355560 (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- de Raadt, A.; Warrens, M.J.; Bosker, R.J.; Kiers, H.A.L. A Comparison of Reliability Coefficients for Ordinal Rating Scales. J. Classif. 2021, 38, 519–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukaka, M.M. A guide to appropriate use of correlation coefficient in medical research. Malawi Med. J. 2012, 24, 69–71. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).