Abstract

The rapid growth of University Science and Technology Innovation Parks (USTIPs) have recently been vital to China’s innovation-driven development. However, contributions to regional economic growth remains understudied. The Yangtze River Delta (YRD), given its economic foundation, concentration of higher institutions, and innovation policy emphasis, provides an ideal context for such study. This paper examines the relationship between USTIPs and regional economic development in the YRD. A multivariate regression analysis across 41 cities revealed that a 1% increase in USTIP quantity corresponds to a 0.122% rise in GDP, a 0.096% increase in high-tech industrial output, and a 0.087% improvement in land use efficiency. These effects are weaker than those of other Science and Technology Innovation Parks (STIPs), which contribute a 0.595% GDP increase, 0.106% growth in high-tech output, and 0.289% improvement in land use efficiency. A comparative analysis further showed that 12 USTIPs employ 21,325 staff with a registered capital of USD 2.12 billion, substantially lower than 123 STIPs that employed 226,055 staff with USD 24.09 billion capital. Despite these limitations, USTIPs are established as long-term drivers of innovation ecosystems and regional competitiveness. These findings serve as empirical evidence linking USTIPs to economic growth, providing valuable insights for optimizing regional innovation policies.

1. Introduction

Technological innovation has recently emerged as a key driver of regional economic transformation, industrial upgrading, and high-quality development [1]. As central hubs of knowledge creation, talent development, and technological advancement, universities play a crucial role within national innovation systems [2]. University Science and Technology Innovation Parks (USTIPs) serve as a key platform for academic research and industry–academia integration [3]. These platforms are increasingly essential in portraying universities’ innovation potential, accelerating technology transfer, and supporting regional socio-economic development [4,5]. Their operational efficacy significantly impacts the magnitude of the relationship between innovation, industrial, and talent chains, with strategic implications for enhancing regional innovation capacity and competitiveness [6]. Theories such as the National Innovation Systems (NIS) theory, the Triple Helix Model (university–industry–government collaboration), and the Innovation Spillover Theory establishes how USTIPs promote economic growth [7,8,9]. These theories collectively indicate that USTIPs are comprehensive platforms that transform academic knowledge into economic output through multi stakeholder collaboration and knowledge diffusion [10,11,12,13,14,15].

Research globally shows that USTIPs have rapidly evolved from incubation-oriented facilities into complex multi-stakeholder innovation hubs [16]. The governance structures of USTIPs have changed from the early single actor models dominated by a host university or government to institutional framework characterized by more comprehensive and coordinated multi-stakeholder governance [17]. High-performing science parks tend to adopt more open and collaborative governance frameworks that enhance overall strategic alignment among actors for their effective operation [18]. USTIPs have also undergone functional transition to a more comprehensive innovation hub. Studies indicate that, beyond their earlier role as basic incubation hubs, USTIPs have presently transformed to comprise a range of diversified functions that include research commercialization, startup incubation and acceleration, talent training, high-end enterprise clustering, innovation services, and policy experimentation [19]. This diversification marks a significant transformation from a mere physical space to multi-stakeholder innovation hubs. USTIPs in China have exhibited development patterns that are consistent with international trends and are shaped by the country’s strategies and regional institutional framework [20,21]. Chinese USTIPs depend not only on universities for knowledge creation, scientific research capabilities, and human capital, but also rely heavily on local industrial policies, fiscal incentives, spatial planning, land support mechanisms, technology intermediaries, and industrial capital [22,23]. The combined influence of these interrelated factors helps explain the different development trajectories of USTIP in China’s rapidly growing innovation system.

Several studies have highlighted the multi-dimensional economic contributions of science and technology parks in enhancing innovation performance, job creation, and industrial restructuring [24,25,26]. Research on Stanford Research Park and Cambridge Science Park have demonstrated the potential of robust university–industry integration in creating regional innovation spillovers and entrepreneurial dynamics [27,28,29]. Such findings have led to the broader assessment of incubation mechanisms, university–industry collaboration, and the dynamics of innovation hubs [30,31]. Studies have shown that proximity to universities significantly improves the capacity of science parks to generate and absorb innovative ideas and advanced knowledge, which in turn increases their absorptive capacity [28,32]. Further empirical studies show that most firms and employees located within USTIPs have substantial multiplier effects that contribute to the indirect and induced employment in surrounding areas [33,34]. In China, recent studies indicate that USTIPs improve the productivity and innovation outputs of tenant firms [17,35], contribute to employment generation [36], and support the development of high-tech industries [37,38]. Such studies reveal that USTIPs facilitate the agglomeration of high-tech enterprises and support the transition of knowledge-oriented industrial structures [14,39].

However, despite the growing studies on USTIPs, vital knowledge gap still exists regarding its socio-economic contributions, particularly within the economic region of the Yangtze River Delta (YRD) in China. Existing studies are largely descriptive, lacking an empirical evaluation of newer and more diversified USTIP models. The YRD region in China has undergone rapid expansion that is characterized by large scale urban growth and socio-economic development [20]. Technological innovation has emerged as a vital pillar of the integrated development strategy of the region [40]. Such innovations are driven by a dense concentration of top-tier universities whose global ranking reflects increasing academic strength and research capacity [41]. However, despite the advances, the economic contributions of these universities remain understudied, especially through USTIPs. While universities and research institutions are abundant in the YRD, their potential to drive regional economic development and facilitate industrial transformation has not been fully harnessed [42].

In response to these research gaps, the present study examines USTIPs through a more detailed and systematic analysis on how the developmental patterns of USTIPs in the YRD influence regional economic development. Therefore, the study answers the following questions: (i) What are the key development characteristics of USTIPs in the YRD? (ii) What are the comparative advantages and limitations relative of USTIPs relative to other STIP types? (iii) What are the key roles of USTIPs to the regional economic development of the YRD region?

2. Theoretical and Analytical Framework

This study examines the influence of USTIPs on regional economic development. To provide a robust theoretical foundation, we integrated the National Innovation Systems (NIS) theory, the Triple Helix Model (university–industry–government collaboration), and the Innovation Spillover Theory to develop a comprehensive theoretical framework for empirical analysis.

2.1. National Innovation System (NIS)

The NIS framework emphasizes the systematic interaction between institutions, businesses, and government policies in promoting innovation [8]. In the context of USTIPs, the NIS highlights the vital role of regional innovation infrastructure that includes research institutions, technology transfer hubs, and policy support [13]. Such elements help strengthen regional productivity, promote industrial upgrading, and improve land use efficiency by enhancing knowledge creation, accelerating technology transfer, and optimizing resource allocation [9].

2.2. Triple Helix Model (THM)

The triple helix model highlights the collaborative relationship between universities, industries, and governments [15]. Within USTIPs, these interactions are strongly reflected through joint scientific research, business incubation, open experimental platforms, and innovation support policies [10]. The THM suggests that collaboration between the three sectors not only improve technology transfer efficiency but also promotes the technological commercialization process, thereby accelerating regional economic growth [14].

2.3. Innovation Spillover Theory (IST)

The theory of innovation spillover indicates that the knowledge and technology generated by a single innovation subject will spread to surrounding enterprises and industries through geographical proximity, personnel mobility, supply chain relationships, and other channels, and further generate positive external effects [11]. In USTIPS, research hubs from universities, high-tech enterprises, and knowledge and technology spillovers can improve regional industrial innovation capabilities [7], promote industrial upgrading, and generate broader economic benefits [35].

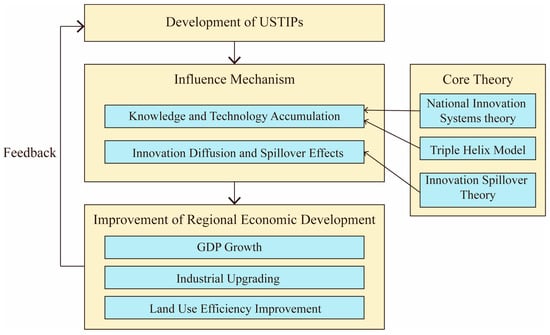

2.4. Integrated Analytical Framework

Based on the three (3) theories discussed above, this study proposes an integrated analytical framework (Figure 1), which illustrates how USTIPs promote regional economic development through the synergy of the national innovation system, triple helix interaction, and innovation spillover effects:

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework.

2.4.1. Knowledge and Technology Accumulation (NIS and Triple Helix)

USTIPS strengthens regional innovation infrastructure and improves cooperation in university–industry–government partnerships.

2.4.2. Innovation Diffusion and Spillover Effects (Innovation Spillover)

Knowledge produced within USTIPs is spread to local enterprises, thereby promoting industrial restructuring and upgrading.

2.4.3. Improvement of Regional Economic Performance

Under the combined effect of enhanced innovation capability and industrial upgrading, regional GDP growth, land use efficiency, and industrial competitiveness significantly improve.

2.5. Research Hypotheses

Based on the above theoretical framework, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1:

The development of USTIPs has a significant positive effect on regional GDP growth, industrial restructuring and upgrading, and land use efficiency.

H2:

While USTIPs exert significant positive economic effects, their effects are weaker compared to other types of STIPs.

3. The Study Area and Data Sources

3.1. The Study Area, i.e., Yangtze River Delta Region

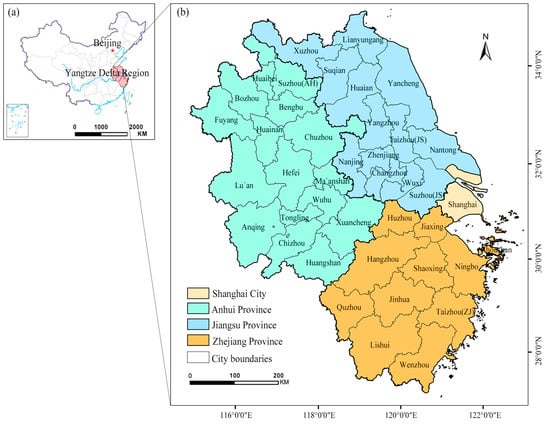

The Yangtze River Delta (YRD) region is one of China’s most economically dynamic and innovation-intensive territories. It has forty-one cities across Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Anhui provinces (Figure 2) with a land area of approximately 358,000 km2 and permanent population of 238 million in 2024, representing 16.9% of China’s population [43].

Figure 2.

Location map of (a) China and (b) Yangtze River Delta Region.

The rationale of choosing the YRD region as the study areas is mainly due to the following:

Firstly, the YRD region demonstrates formidable economic prowess characterized by both scale and momentum. In 2024, the region’s GDP exceeded RMB 33 trillion, i.e., USD 4.6 trillion, growing at 5.5% annually [43]. Remarkably, while occupying merely 4% of China’s land area, the YRD generated 24.7% of national economic output, and achieved a per capita GDP of RMB 139,400, i.e., USD 19,500.

Secondly, the YRD region serves as China’s central hub for technological innovation [44]. It has high ranking academic institutions that include Zhejiang University, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Fudan University, University of Science and Technology of China, Nanjing University, and Chinese Academy of Sciences Shanghai Branch that deliver robust scientific research. Similarly, the YRD region has several innovation actors comprising 78% of China’s high-tech enterprises, 63% of unicorn startups, and regional headquarters of multinational R&D centers. Industry pioneers such as Alibaba, SMIC, and iFLYTEK anchor this vibrant corporate innovation ecosystem.

Thirdly, the integration of the YRD region constitutes a strategic priority for China’s new development paradigm. Technological innovation serves as the vital engine that drives this integration process by creating opportunities for the advancement of USTIPs and the intensification of competitive pressures. These compel USTIPs to enhance core competencies through operational scaling and innovation upgrading.

Therefore, focusing on China’s YRD provides vital analytical data and scientific insights for the region’s socio-economic growth and development.

3.2. Data Sources

3.2.1. Rationale for Data Selection

The dataset of three provinces and one municipality in the Yangtze River Delta (YRD) Region (i.e., Anhui, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Shanghai) were utilized for the study. The datasets obtained from the 2022 statistical data of the National Bureau of Statistics of China and the China Land Cover Database (CLCD) which provided the validated economic and industrial data of the YRD region, obtained across the entire study period. Also, Gaode Map version 16.6.1 was utilized for mapping due to its high precision in geocoding and Point of Interest (POI) identification. The study applied logarithmic transformations to the study’s variables to mitigate heteroscedasticity and facilitate the economic interpretation of regression coefficients in terms of percentage changes and elasticities.

3.2.2. Data of STIPs and USTIPs

We utilized a mixed method approach to identify the study area’s Science and Technology Innovation Parks (STIPs). The sources of primary data included official registries from China’s Ministry of Science and Technology, Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Commission, and provincial science departments of Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Anhui. These repositories cataloged national/provincial-level development zones, university science parks, technology–business incubators, and new-type R&D institutions. Secondary data were obtained using Gaode Map version 16.6.1. The Point-of-Interest (POI) were identified and classified under “industrial parks” and “research institutions” and filtered against the National framework of China’s Bureau of Statistics’ that classified the country’s high-tech industries. The study further conducted a deduplication and a cleansing procedure, with a total of 5430 validated STIPs compiled.

The data included the name of the STIPs, the year of establishment, the entity of establishment, geographical coordinates, functional classification, and other information. We used Python 3.8.10 for data collection and processing and geocoded the target park with the help of the Gaode Map version 16.6.1 Open Platform Web Service API to obtain accurate coordinates. In addition, we utilized the STIPs’ official websites and authoritative reports, manually collected and verified attribute data that include year of establishment to ensure its effectiveness for econometric modeling, and finally derive the STIPs dataset from 1992 to 2024.

These STIPs were categorized into the seven (7) categories presented in Table 1, i.e., government-led, university-led, enterprise-led, university–government collaboration, university–industry collaboration, government–enterprise collaboration, and tripartite (government–enterprise–university). The USTIPs has university-led, university–government collaboration, university–industry collaboration, and tripartite collaboration having a total of 965, while other STIPs comprised government-led, enterprise-led, and government–enterprise collaboration having a total of 4465.

Table 1.

USTIPs and other STIPs within the YRD based on the founding entities.

3.2.3. Enterprise Development Data

The study acquired enterprise development data of the YRD region using Qichacha’s geospatial query platform. The platform provided the registration names, industry classification, social insurance enrolee counts, and registered capital of all the enterprises with the YRD. Their point data were spatially mapped in ArcGIS 10.7.1 and grouped as USTIP-located or other-STIP-located based on centroid positioning.

3.2.4. Regional Economic Development Data

Data spanning the years 2000 to 2022 were collected for this study. The extent of the YRD region’s built-up area were retrieved from China’s Annual Land Cover Dataset (CLCD) [45]. Also, economic indicators and control variables were obtained using China’s Statistical Yearbook (National Bureau of Statistics) and Provincial/Municipal Statistical Yearbooks (Anhui, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Shanghai).

4. Methodology

4.1. Variable Selection

In order to test the hypotheses, the following variables were selected:

4.1.1. Independent Variables

The independent variables for this study comprise the number of USTIPs and the number of other types of STIPs.

4.1.2. Dependent Variables

The study employed four key dependent variables, namely Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the proportion of the secondary industry (STR1), the proportion of the tertiary industry (STR2), and land use efficiency (LUE), to reflect economic development. This was based on similar approach used in earlier studies [46,47,48].

4.1.3. Control Variables

The number of permanent residents (POP), fixed assets investment (INV), foreign direct investment (OPE), and government expenditure (GOV) served as the study’s control variables as previously utilized [49,50,51]. Table 2 defines all variables used in this study.

Table 2.

Description of study’s independent, dependent variables, and control variables.

4.2. Spatial and Regression Analysis

4.2.1. Spatial Analysis

The study spatially mapped and analyzed the distribution of University Science and Technology Innovation Parks (USTIPs) in the YRD region using ArcGIS 10.7.1 Software.

4.2.2. Regression Analysis

A linear regression analysis was employed to examine the relationship between the independent variables and economic development indicators during the period between 2000 and 2022, with a comparative analysis conducted to assess the differential contributions of USTIPs relative to other STIPs. The study employed the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) method for the calculation of regression coefficients. The method was to obtain the optimal coefficient estimation value by minimizing the sum of squared residuals [52]. The regression analysis was performed using SPSS 26.0 and Python 3.9. The results were calculated using Equation (1) below:

where

Y represents the dependent variable, such as GDP, STR1, STR2, or LUE;

, are independent variables, representing the quantities of USTIP and STIP, respectively;

, are coefficients of the core independent variable, representing the average change in the dependent variable Y for each unit increase in the core independent variable while controlling for other variables;

, , , are control variables representing POP, INV, OPE, and GOV, respectively;

, , , are control variables, and their coefficients represent the average change in the dependent variable Y for each unit increase in the control variable, while keeping other variables constant;

is the error term, indicating the random errors that the model cannot explain comprising all factors not considered by the model, as well as measurement errors.

4.2.3. Model Validation and Endogeneity

The study utilized a t-test to verify whether the relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable in the regression model is significant. If the p-value is less than 0.05, the statistical result is considered significant, rejecting the null hypothesis and assuming that the independent variable has a significant impact on the dependent variable. Thereafter, the R2 was used to assess the model’s fit of goodness. The closer the R2 value is to 1, the better the fitting effect of the model on the data, and the higher the variability of the data that the model can explain. The F-value was also conducted to test the overall significance of a regression model. It was calculated using the ratio of Mean Square for Regression (MSR) to Mean Square for Error (MSE) of the regression model. The F-value was used to determine whether the regression model is more explanatory than the simple mean model. If the F value is much greater than 1, it indicates that the regression model is significantly better than the model that only contains constants, that is, the model as a whole is significant. All regression models were estimated using heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors (SEs), ensuring that coefficient estimates are accompanied by consistent and reliable standard errors. The smaller the robust SE, the smaller the difference between the predicted and observed values of the model, and the higher the accuracy of the model.

Although the study employed the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) for its analysis, several measures were undertaken to reduce endogeneity. Control variables that include population (POP), fixed asset investment (INV), foreign direct investment (OPE), and government expenditure (GOV) were incorporated to capture the baseline economic conditions that may simultaneously influence USTIP development and regional economic growth. Also, the temporal span of the dataset utilized helped to capture the long-term influence of USTIP development, reducing short-term bias. Lastly, the comparative analysis between USTIPs and other STIPs helped isolate the relative influence of USTIPs within the regional innovation hubs. These measures do not completely eliminate endogeneity but help to improve robustness and interpretability of the results.

Therefore, to rigorously address the endogeneity issue arising from the potential reverse causal relationship between USTIPs and regional economic development, the study further employed an instrumental variable (IV) approach using a two-stage least squares (2SLS) regression. Two instrumental variables were utilized comprising:

- (i)

- Historical University Presence: Measured by the number of undergraduate universities in each city in 2000. This variable is closely related to the current developmental basis of USTIP, but as a historical variable, it meets the requirement of exogeneity.

- (ii)

- Land Resource Endowment: Measured by the built-up area of the city in 2000. The early built-up area reflects the development foundation and land development inertia of cities and is highly correlated with the subsequent location of USTIPs. The scale of urban development in 2000 is due to historical development and is not directly related to the present economic error term.

5. Results

5.1. Analysis of the STIP System in China

The analysis of the result reveals that China has progressively established a multi-tiered Science, Technology, and Innovation Platform (STIP) system since 1980s (Table 3).

Table 3.

STIP System in China.

At the initial stage, the Economic and Technological Development Zones (ETDZs) of China were created as advanced manufacturing clusters that served as the main engine of regional economic growth. Subsequently, High-Tech Industrial Development Zones (HTIDZs) emerged with a dedicated focus on cultivating high-technology industries and today serving as the main hubs for China’s innovation-driven development strategy. Later, the National Innovation Demonstration Zones (NIDZs) of China were established to serve as core platforms for advancing China’s innovation-driven development and promoting the transition toward an innovation-oriented society. These large-scale zones also had smaller but yet strategically significant entities that comprise University Science Parks (USPs), technology business incubators, maker spaces, and new Research and Development (R&D) institutions. These entities jointly form a diversified, multi-level STIP system that combines industrial, academia, and research activities.

The Yangtze River Delta (YRD) region hosts about 20 to 35% of all the national-level STIPs. This number underscores the region’s role as China’s most dynamic innovation hub. Also, the provincial and municipal governments within the YRD have expanded the regional network by introducing localized certification schemes that reinforce the density and diversity of the innovation landscape. Recent policies such as the 2024 Action Plan for Promoting High-Quality Development of National-Level New Areas in China, issued by the National Development and Reform Commission, prioritizes the development of scientific capacity and industrial competitiveness as its key strategic objective. Similarly, universities are increasingly integrated into innovation chains through USPs and collaborative research consortia, accelerating industry/academia/research collaboration and strengthening regional innovations.

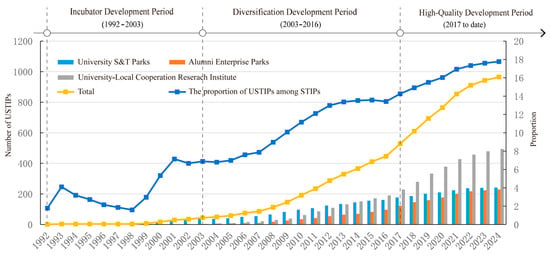

5.2. Analysis of the Growth of USTIPs in the YRD Between 1992 and 2024

Since 1992, USTIPs within the Yangtze River Delta (YRD) have experienced rapid and dynamic expansion (Figure 3). This expansion can be categorized into the three distinct phases presented below.

Figure 3.

The number of USTIPs in YRD from 1992 to 2024.

5.2.1. Incubator Development Period (1992–2002)

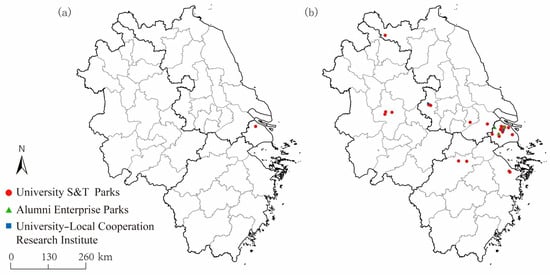

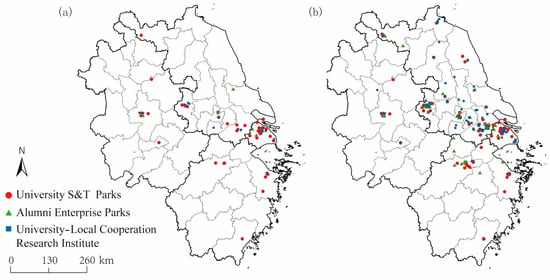

During this initial stage, USTIPs within the YRD region mainly adopted the conventional university science park models, which emphasized technology transfer and venture incubation. The establishment of the Shanghai University of Technology Science Park in 1992 marked the region’s first USTIP. From 1999 to 2001, key university science parks in the YRD, within the Shanghai Jiao Tong University and Zhejiang University, were officially recognized as national university science parks. This recognition stimulated broader institutional participation in park development; however, the growth was mainly in Shanghai, Nanjing, and Hefei. By 2002, a total of 35 USTIPs were operating within the YRD, following an incubation-oriented paradigms (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Spatial mapping of USTIPs in (a) 1992 and (b) 2002.

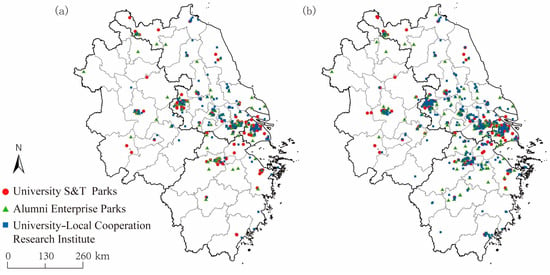

5.2.2. Diversification Development Period (2003–2016)

This phase marked a transition from the singular incubation models to the diversified and collaborative innovation structures (Figure 5). Two landmark developments occurred in 2003 with the establishment of the Yangtze Delta Region Institute of Tsinghua University (YIT) and the Suzhou Institute for Advanced Research (SIAR), which became the catalysts for the region’s scientific innovation. During this period, the number of USTIPs grew significantly, rising from 44 in 2003 to 334 in 2016, with geographic expansion into Hangzhou and Suzhou. By 2016, university–local government research institutes became the predominant model, accounting for 42.5% of all USTIPs. This trend signified the region’s progression toward more integrated and multi-tie innovation system.

Figure 5.

Spatial mapping of USTIPs in (a) 2007 and (b) 2012.

5.2.3. High-Quality Development Period (2017 to Date)

This phase is being shaped by the broader context of urban transformation and regional integration within the YRD as shown in Figure 6. This stage is defined by the strengthening of multi-agent collaboration mechanisms, cross-regional collaborations, and integrated frameworks of “research × transformation (incubation) × industrialization × talent training”. Such initiatives highlight the growing interconnectedness between academic resources and local development agendas. Spatially, USTIPs have merged with five core innovation hubs in Shanghai, Nanjing, Suzhou, Hangzhou, and Hefei, and have simultaneously expanded to surrounding urban areas. By 2024, the YRD hosted 955 USTIPs, representing 17.8% of all Science and Technology Innovation Parks (STIPs) in YRD. This progress highlights the strategic consolidation, functional maturity, and regional significance of USTIPs within YRD region as drivers of China’s innovation-led development.

Figure 6.

Spatial mapping of USTIPs in (a) 2017 and (b) 2024.

5.3. Regression Analysis Between USTIPs Growth and Economic Development Indicators

The study employed a multivariate linear regression model across forty-one YRD cities, with GDP, STR1, STR2, and LUE as dependent variables, number of USTIPs as the independent variable, and POP, INV (investment), OPE, and GOV as controls. The regression results revealed a substantial positive effect of USTIPs on regional economic development.

5.3.1. USTIPs Directly Stimulate GDP Growth

Table 4 shows that a 1% increase in the number of USTIPs was associated with a 0.443% rise in GDP. This can be attributed to the numerous economic activities hosted within USTIPs comprising enterprise output, investment attraction, technology commercialization, and job creation. For example, Jicui Yaokang, incubated through Nanjing University’s Humanized Models and Drug Screening Innovation Technology Institute, has grown into one of the world’s largest murine model suppliers, reporting RMB 687 million in revenue in 2024. Similarly, since its establishment four years ago, Xidian University’s Hangzhou Research Institute has signed 558 contracts and agreements worth RMB 490 million and attracted RMB 630 million investment in corporate R&D. These cases exemplify how USTIPs generate direct economic output and also mobilize private-sector innovation capital.

Table 4.

Regression results between GDP and USTIPs.

5.3.2. USTIPs Accelerate Industrial Restructuring and Upgrading

Table 5 and Table 6 indicate an inconsistent but yet a balancing dynamic: a 1% increase in USTIP numbers corresponds to a 0.099% decline in STR1, i.e., traditional industries and a 0.167% increase in STR2, i.e., emerging industries. This signifies the role of USTIPs as both catalysts for upgrading conventional industries and incubators for new growth sectors. However, parks such as Nanjing Gulou National University Science Park leverage the city’s manufacturing base by nurturing high-tech enterprises such as NARI Group and Emerson Electric. This fosters industrial clusters in electronics, power automation, and new materials. Therefore, USTIPs drive the rise in frontier technologies. The Hefei National Comprehensive Science Center, drawing on the scientific achievements of the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC), has incubated globally leading quantum technology enterprises that include QuantumCTek and Origin Quantum. These firms have established Hefei as the “Quantum Capital,” highlighting the role of USTIPs in positioning the YRD at the forefront of next-generation industries.

Table 5.

Regression results between STR1 and USTIPs.

Table 6.

Regression results between STR2 and USTIPs.

5.3.3. USTIPs Enhance the Efficiency of Regional Economic Development

Table 7 shows that for every 1% increase in the number of USTIPs, land use efficiency (LUE) increases by 0.243%. Therefore, USTIPs function as integrative platforms that acquire resources from universities, enterprises, and governments to build collaborative innovation systems. For instance, Shanghai University Science Park, through its Robotics Key Laboratory and collaboration with Kangda Kale Medical Technology Co., Ltd. (affiliated with East China Normal University), has advanced minimally invasive interventional therapy and precision medicine. Such cases exemplify how USTIPs not only improve economic outputs but also enhance the overall efficiency and quality of regional development. The result of various regression models reveals that USTIPs significantly contribute to the YRD’s economic transformation by boosting GDP, restructuring industries, and improving efficiency. These findings highlight the strategic role of USTIPs as vital hubs for high-quality innovation-driven regional development in China.

Table 7.

Regression results between LUE and USTIPs.

5.4. Instrumental Variable Analysis for Endogeneity Problem

The study utilized a two-stage least squares (2SLS) method for the instrumental variable (IV) analysis. The regression results of the first stage (Table 8) show that IV1 (β = 0.37, p < 0.05) and IV2 (β = 0.206, p < 0.05) are significantly positively correlated with the number of USTIPs, indicating that they are key factors influencing USTIP growth. Also, the first stage revealed an F-statistic value of 10.749, exceeding the threshold of 10. This result rules out the concerns of weak instrumental variables.

Table 8.

First-stage regression results.

The regression results of the second stage (Table 9) indicate that, after considering endogeneity problems, the positive impact of USTIPs on regional economic development remains statistically significant. Specifically, the regression coefficients of USTIPs for GDP, STR1, and STR2 are 1.223, 0.326, and 0.801, all greater than the corresponding OLS regression coefficients of 0.443, 0.099, and 0.167. This indicates that U STIPs have a stronger influence on economic growth and industrial structure. Also, USTIPs’ regression coefficient for LUE is 0.103, which is lower than the 0.243 in OLS regression, but still retains a strong positive influence. Thus, the analysis of the IV confirms the study’s findings of USTIP’s positive economic contributions. It also provides more credible evidence, indicating that this relationship is not solely driven by reverse causality.

Table 9.

Second-stage regression results.

5.5. Comparative Analysis of Economic Contributions Between USTIPs and Other STIP

For the comparative analysis, the study employed a multivariate linear regression model across forty-one YRD cities, with the four indicators of economic development, i.e., GDP, STR1, STR2, and LUE as dependent variables. The number of USTIPs were used as the independent variable, while population (POP), investment (INV), openness (OPE), and government expenditure (GOV) were the control variables. The results revealed significant but heterogeneous effects of USTIPs on regional economic development (Table 10).

Table 10.

Regression results between economic development and USTIPs.

The results indicate that USTIPs exert weaker economic effects compared to other types of science and technology innovation parks. Specifically, a 1% increase in USTIP quantity was associated with 0.11% GDP growth, a 0.096% increase in STR2, and a 0.087% rise in LUE, with no statistically significant effect on STR1.

The non-significant impact on STR1 indicates that USTIPs have a relatively limited effect on the transformation and upgrading of the secondary industry, with the current driving effect appearing more evident in the tertiary industry, which is centered on technological innovation services. This finding underscores the need to promote the deeper integration of university-generated innovations with traditional secondary industries.

In comparison, the other STIPs demonstrated substantially greater impacts with a 1% increase corresponding to 0.595% GDP growth, 0.106% STR2 increase, and 0.289% LUE improvement. This difference highlights the small operational scale and lower productivity level of USTIPs compared to other STIPs. These results are further substantiated by large-scale statistical data. According to the 2024 Statistical Yearbook, enterprises located in National High-tech Industrial Development Zones (HTIDZs) within the YRD region generated a total revenue of USD 2104.98 billion in 2023, employing 7.4343 million people, with per-employee revenue reaching USD 297,290. By comparison, enterprises incubated from national-level USTIPs had lower figures with a total revenue of USD 19.17 billion and 180,200 employees that resulted in a per-employee revenue of USD 106,408. This difference highlights USTIPs’ smaller operational scale and weaker productivity levels relative to other STIPs. As presented in Table 11, the Hangzhou Chengxi S&T Innovation Corridor provides a micro-level case that exemplifies this disparity.

Table 11.

Comparison of statistical data between USTIPs and other STIPs in Hangzhou Chengxi S&T innovation corridor.

Among the total STIPs of 135, only 12 are USTIPs. These 12 parks accommodate 861 enterprises with USD 2.12 billion in registered capital and 21,325 insured employees, with a registered capital density of USD 57.22 million/km2 and employee density of 5748/km2. In comparison, the 123 non-university STIPs had stronger indicators comprising USD 24.09 billion in registered capital and 226,055 insured employees that corresponds to a capital density of USD 74.64 million/km2 and employee density of 7005/km2.

This comparison shows that USTIPs exert weaker economic effects, operate at smaller scales, and deliver lower output efficiency relative to other STIPs. Such findings highlight the importance of regional development strategies to address USTIPs’ structural bottlenecks while concurrently leveraging their advantages through targeted policy interventions to strengthen their economic contributions.

6. Discussion

The results revealed that University Science and Technology Innovation Parks (US-TIPs) exert a significant impact on regional economic development (β = 0.122, p < 0.01), thus verifying research hypothesis H1 which states that the development of USTIPs has a significant positive effect on regional GDP growth, industrial restructuring and upgrading, and land use efficiency. However, consistent with Hypothesis H2, such contributions remain markedly weaker than compared to the other Science and Technology Innovation Parks (β = 0.595, p < 0.001). This finding underscores the presence of structural bottlenecks within the YRD region that demand urgent consideration.

The declining economic influence is attributed to the failure of USTIPs within the YRD region to achieve cluster effects due to insufficient resource integration capabilities and limited industrial chain embeddedness. USTIPs usually have fewer enterprises and less capital overall, leading to smaller output, while other STIPs in the region with large government-designated high-tech zones typically have more established industries and larger firm clusters than USTIPs. Despite their abundance to high-quality talent pools, USTIPs mainly served as campus-based innovators without effectively leveraging alumni networks and broader social capital [53,54]. This results in fragmented innovation activities that fail to generate economies of scale. In contrast, the underdeveloped industry–academia coordination mechanisms constrain tenant composition by primarily focusing on technology startups [55,56]. This hinders the attraction of industries, thereby limiting knowledge spillovers and stifling innovation circulation within the broader industrial system.

Another significant challenge is the lopsided emphasis on frontier research over industrial application. For instance, national reports in China indicates that while Chinese enterprises achieve a patent industrialization rate of 48.1%, universities reach only 3.9%. This disparity suggests an underutilization of academic intellectual capital and the inefficiency of technology transfer pathways [57]. Therefore, the present study highlights this problem in three interrelated ways that include research agendas often prioritize academic outputs over market applicability, commercialization requirements are frequently overlooked, and fragmented policy frameworks continue to impede the conversion of knowledge into productivity. These findings align with earlier studies that identified limited knowledge transfer [58], inadequate industry engagement [59], and insufficient support mechanisms for transforming research into practical outcomes [60]. It has also been reported that substantial research teams of universities do not fully understand the practical needs of the industry [49]. This contributes to the failure of technical cooperation.

In addition, university faculty members face multiple obstacles when transiting from scientists to entrepreneurs [61]. At the level of identity recognition, they are compelled to juggle the triple roles of scholar, educator, and entrepreneur. This results in conflicts in values, objectives, norms, and practices. At the property rights level, disputes often arise regarding ownership and benefit distribution [62], mostly in multi-funded projects where the distinction between official and non-official achievements is blurred. This leads to recurring conflicts over collaborative outcomes. At the skills level, most scientific researchers lack entrepreneurial competencies such as business management, financial insight, and market awareness [63]. This deficiency hinders the establishment of complete value chains from technological development to market-ready products.

Despite these constraints, the strategic importance of USTIPs lies less in its direct economic outputs and their catalytic role in fostering high-quality regional innovation. They serve as key platforms for multi-stakeholder resource convergence that promote the development of innovation-driven ecosystem by strengthening industry/academia/research integration. Therefore, USTIPs effectively enhance the innovation capacity of entire YRD region using the universities, research institutes, enterprises, and government entities. The case of Hangzhou exemplifies how USTIPs can drive systemic innovation. The city has Zhejiang’s first MNSTI project that is backed by over 2.1 billion yuan and the world’s largest-capacity hyper gravity centrifuge. Similarly, Beihang University’s scientific facility has an investment exceeding 3.5 billion yuan, serving as the world’s most advanced breakthroughs in deep-space exploration. The Hangzhou High-Tech Zone also plans to establish a 500-million-yuan technology transfer fund to link research, technology transfer, and industrial incubation. These examples demonstrate the significance of USTIPs in strengthening innovation ecosystems and long-term regional competitiveness.

The successes of the Stanford Research Park in the United States and Cambridge Science and Technology Park in the United Kingdom are deeply rooted in entrepreneurial culture [21], active venture capital market [28], and decades of transformation [64], which led to large-scale innovation clusters with global influence. Studies in Japan show that the government promotes technology transfer through the national subsidy system [65,66]. The findings reveal that the influence of such an intervention is mainly dependent on the tripartite collaboration. This comparative analysis provides valuable perspective into the efficiency gap between foreign and Chinese USTIP. USTIPs in China exhibit limitations in terms of physical scale, concentration of high-tenants, and the collaboration between industry, universities, and research institutions. These international examples suggest that USTIPs in the Yangtze River Delta remain at an early stage of a comparable development trajectory, demonstrating a strong regional potential to lead innovation in China.

Therefore, addressing the identified challenges would help significantly in achieving regional improvements in technological output, organizational capacity, and innovation performance.

7. Conclusions

The study provides an empirical understanding of how University Science and Technology Innovation Parks (USTIPs) strategically contribute to high-quality regional development, while providing the various constraints that limit their economic contributions. The study establishes three major findings. The study revealed that USTIPs exerted a clear and statistically significant positive impact on the regional economic development within the YRD. This is mainly due to enterprise incubation, technology commercialization, capital concentration, and employment generation. Despite this impact, USTIPs still contribute less economically than other types of Science and Technology Innovation Parks (STIPs). These weaker effects are mainly due to constraints such as limited resource integration and insufficient industrial chain coordination; evaluation and knowledge transfer mechanisms that prioritize research over industrial application; and persistent barriers to academic entrepreneurship. Also, the study’s outcome reveals that although the immediate economic impact of USTIPs was modest, USTIPs possess strong innovation potential and long-term strategic relevance. USTIPs ability to integrate research, industry, and educational functions positions as them as vital hubs for advancing regional scientific and industrial innovation, particularly within China’s 21st century innovation-driven framework.

8. Policy Recommendations

Based on the above findings, the following prioritized and operational actions are proposed to strengthen USTIP performance within the Yangtze River Delta (YRD) and beyond:

- (i)

- Prioritize USTIPs within national and regional innovation strategies: Governments should elevate USTIPs as core instruments for implementing innovation-driven development. This will help improve and enhance their economic and innovation jobs.

- (ii)

- USTIPs development must align with regional economic objectives: USTIPs should focus more on economic vitality and ensure that development strategies and performance evaluation systems give equal priority to industrial restructuring (STR1). This includes balancing academic excellence with industrial relevance and societal value creation to improve both long-term productivity and the structural upgrading of the regional economy.

- (iii)

- Strengthen university-led innovation ecosystems: Universities should leverage USTIPs by clustering innovative enterprises and adopting multi-stakeholder governance models. This approach will help universities establish competitive innovation hubs. Policies should focus on deepening the integration between academia and industry in order to drive the upgrading of traditional industries (STR1), while simultaneously improving innovation economy (STR2) and land use efficiency (LUE).

- (iv)

- Adopt context-model for stronger university–region integration: USTIP should have local industrial bases, university strengths, locational advantages, and policy frameworks helps to effectively achieve both academic and economic objectives.

- (v)

- Leverage regional integration for cross-jurisdictional coordination: Governments and universities should promote the shared deployment of research assets across regional jurisdictions to address disparities in academic funding and discipline–industry mismatches across cities. Such measure will contribute to a more integrated and dynamic innovation ecosystem.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W.; methodology, S.Z.; validation, A.F.K. and Z.H.; formal analysis, S.Z. and Y.W.; investigation, S.Z. and Y.W.; data curation, S.Z., A.F.K., and Z.H.; writing—original draft, S.Z.; writing—review and editing, A.F.K. and Z.H.; visualization, S.Z.; supervision, Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution section.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yuan, X.-M.; Wei, F.-L.; Li, H.; An, Y. Analysis of the Coupling Coordination and Spatiotemporal Evolution of High-Tech Industrial Technological Innovation and Regional Economic Development. Complexity 2022, 2022, 3076336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magumba, D. Institutionalizing University-Business Innovation Systems in an Innovation Economy. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 2023, 8, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Feng, Y.; Liu, S. Analyzing the Innovation Ecosystem of China’s Major Science and Technology Projects: From the Ecological and Systems Science Perspective. Proj. Leadersh. Soc. 2024, 5, 100156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Li, S.; Shen, Q. Science and technology evaluation reform and universities’ innovation performance. Technol. Soc. 2024, 78, 102614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Liu, R.; Yang, B. Bridging the ivory tower and industry: How university science parks promote university-industry collaboration? Res. Policy 2025, 54, 105241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton-Tejon, M.; Barge-Gil, A.; Martinez, C.; Albahari, A. Science and technology parks and their heterogeneous effect on firm innovation. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2024, 73, 101820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Li, S. Can the Establishment of University Science and Technology Parks Promote Urban Innovation? Evidence from China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Xu, M. The Role of Universities in the National Innovation System and the Evolution of Practice. In Proceedings of the 2025 11th International Conference on Humanities and Social Science Research (ICHSSR 2025), Beijing, China, 25–27 April 2025; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2025; pp. 1550–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q. Study on Collaborative Path of Transformation of Scientific and Technological Achievements in Universities-Taking Chengdu as an Example. Adult High. Educ. 2025, 7, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fu, W.; Schiller, D. Structural and agentic powers in university-based regional innovation across Chinese core and non-core cities. Reg. Stud. 2025, 59, 2555873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarpong, D.; Meissner, D.; Moraes, G.H.S.M.d.; Vismara, S. The impact of university-industry engagement and the rise of competency transfer partnerships. J. Technol. Transf. 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Liu, X.; Song, Y.A. A Quantitative Research on the Collaborative Innovation Policy of Industry-University-Research Institute in Shanghai-Three-Dimensional Analysis Based on Policy Subjects, Policy Tools and Innovation Chains. Adv. Appl. Math. 2023, 12, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theeranattapong, T.; Pickernell, D.; Simms, C. Systematic Literature Review Paper: The Regional Innovation System-University-Science Park Nexus. J. Technol. Transf. 2021, 46, 2017–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailu, A.T. The Role of University–Industry Linkages in Promoting Technology Transfer: Implementation of Triple Helix Model Relations. J. Innov. Entrep. 2024, 13, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Yang, D. Research on the mechanism of government-industry-university-research collaboration for cultivating innovative talent based on game theory. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Koko, A.F.; Han, Z. Spatio-Temporal Correlation between Growth of Science and Technology Innovation Parks (STIPs) and Urban Development in Yangtze Delta Region (YDR), China Using Remote Sensing and GIS Techniques. Geocarto Int. 2025, 40, 2453617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadorin, E.; Klofsten, M.; Löfsten, H. Science Parks, Talent Attraction and Stakeholder Involvement: An International Study. J. Technol. Transf. 2021, 46, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.S.; Nguyen, H.N.; Lin, C.-L. Exploring the Development Strategies of Science Parks Using the Hybrid MCDM Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Dong, B.; Jin, P. Do Science Parks Promote Companies’ Innovative Performance? Micro Evidence from Shanghai Zhangjiang National Innovation Independent Demonstration Zone. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koko, A.F.; Han, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Ding, N.; Luo, J. Spatiotemporal Analysis and Prediction of Urban Land Use/Land Cover Changes Using a Cellular Automata and Novel Patch-Generating Land Use Simulation Model: A Study of Zhejiang Province, China. Land 2023, 12, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Cheng, Z. What Drives the Development of University Science Parks in China: From the Perspective of Evolutionary Economic Geography. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Zhang, F.; Wu, F.; Feng, Y. Governing innovation-driven development under state entrepreneurialism in China. Cities 2024, 152, 105194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; He, A.; Zhai, L.; Yan, S. Can interactive platform of university science parks enhance the quality of university research outcomes? Evidence from a difference-in-differences model. Front. Phys. 2025, 13, 1642172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, C.; Lokshin, B.; Mohnen, P. Heterogeneity in performance of science and technology parks in China: Is there “club” convergence? Pap. Reg. Sci. 2023, 102, 1145–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashau, P.; Fields, Z. The Development of University Technology and Innovation Incubators to Respond to the Needs of the Modern Economy. Int. J. Criminol. Sociol. 2022, 9, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Wu, J.; Yang, H. Increasing entrepreneurs through green industrial parks: Evidence from special economic zones in China. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2024, 72, 287–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albahari, A.; Barge-Gil, A.; Pérez-Canto, S.; Landoni, P. The effect of science and technology parks on tenant firms: A literature review. J. Technol. Transf. 2023, 48, 1489–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval Hamón, L.A.; Ruiz Peñalver, S.M.; Thomas, E.; Fitjar, R.D. From high-tech clusters to open innovation ecosystems: A systematic literature review of the relationship between science and technology parks and universities. J. Technol. Transf. 2024, 49, 689–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamuro, H.; Ikeuchi, K.; Kitagawa, F. The impact of cluster policy on academic knowledge creation and regional innovation: Geography of university–industry collaboration in Japan. Reg. Stud. 2025, 59, 2467407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestro, A.R.; Matos, G.P.; Silva, D.J.; Reis, D.L.; Teixeira, C.S. An analysis on the interactions between actors of the innovation ecosystem and incubators. Int. J. Sci. Manag. Tour. 2024, 10, e949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, M. The role of government-industry-academia partnership in business incubation: Evidence from new R&D institutions in China. Technol. Soc. 2023, 72, 102194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löfsten, H.; Klofsten, M. Exploring dyadic relationships between Science Parks and universities: Bridging theory and practice. J. Technol. Transf. 2024, 49, 1914–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, L.J.; Lim, J.; Pavlakovich-Kochi, V. The University Research Park as a Micro-Cluster: Mapping Its Development and Anatomy. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2013, 43, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdaliso, J.M.; Andrés, C. Science and technology parks as evolving policy instruments: Challenges when embracing the innovation district model. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2025, 33, 646–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ding, S. How Do National University Science Parks Influence Corporate Green Innovation? Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies. Quant. Financ. Econ. 2024, 8, 757–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, D.; Liu, K.; Fu, G.J.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, B.Y.; Bi, F.Q. Relying on the University Science and Technology Park to Carry out the Research and Practice of Integration of Expertise and Innovation Education Reform—Taking the National University Science and Technology Park of Northeast Petroleum University as an Example. Adv. Educ. 2023, 13, 7979–7984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, T. Does University-Industry Collaboration Improve Firm Productivity? Evidence from China. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0305695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ávila, L.V.; Shulla, K.; Favarin, R.; Filho, W.L.; Trevisan, M.; Salvia, A.L.; Giazzon, L.; Santini, É. The role of science and technology parks in meeting the sustainable development goals (importance of sustainability for the STPS). Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Cui, X.; Sarker, M.N.I.; Firdaus, R.B.R. Impact of industry-university-research collaboration and convergence on economic development: Evidence from Chengdu-Chongqing economic circle in China. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Shi, R.; Wu, N.; Yang, J. Measuring the impact of technological innovation on urban resilience through explainable machine learning: A case study of the Yangtze River Delta region, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 127, 106457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, N.; Szumilo, N. Universities’ global research ambitions and their localised effects. Land Use Policy 2019, 85, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, B.; Wang, H.; Wang, H. Is There a Surplus of College Graduates in China? Exploring Strategies for Sustainable Employment of College Graduates. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. China Statistical Yearbook 2024; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2024.

- Sun, X. Research on the Innovation Radiation of Shanghai Science and Technology Innovation Center to the Yangtze River Delta. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1802, 042046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Huang, X. The 30m Annual Land Cover Dataset and its Dynamics in China from 1990 to 2019. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 3907–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; He, Q. Evaluation on Carrying Capacity of Economic, Resources and Environmental Based on the Improved Entropy Method. In Proceedings of the 2015 3rd International Conference on Education, Management, Arts, Economics and Social Science, Changsha, China, 28–29 December 2015; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2015; pp. 1183–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L. The Impact of Coordinated Development of Ecological Environment and Technological Innovation on Green Economy: Evidence from China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Li, X. Construction and application of smart city development evaluation index system. Acad. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2022, 5, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhemhafuki, S. Government Expenditure and Economic Growth: A Cross-Country Analysis. J. Econ. Stud. 2023, 1, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Liu, X.; Zuo, Y. Environmental regulation, pollution emissions and the current account. Rev. World Econ. 2024, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, D.; Wu, X.; Li, D. Changes in Demographic Factors’ Influence on Regional Productivity Growth: Empirical Evidence from China, 2000–2010. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayem, H.M.; Aziz, S.; Kibria, B.M.G. Comparison among Ordinary Least Squares, Ridge, Lasso, and Elastic Net Estimators in the Presence of Outliers: Simulation and Application. Int. J. Stat. Sci. 2024, 24, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, C.T. Analysis of the Functional Development & Progress of Beijing’s TusPark. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2018, 6, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-H.; Lee, W.-C. Establishing science parks everywhere? Misallocation in R&D and its determinants of science parks in China. China Econ. Rev. 2021, 67, 101605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Liu, S.; Rang, C. Research on the Development Path of Intellectual Property in Chinese Universities and Colleges in Light of Open Innovation. Libr. Inf. 2022, 4, 25–36. Available online: https://tsyqb.gslib.com.cn/CN/10.11968/tsyqb.1003-6938.2022051 (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Wang, J.; Gao, J. The Exploration and Practices of TusPark in Promoting Business Incubation and Industrial Development. J. Evol. Stud. Bus. 2022, 7, 298–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Chen, T. Study on Factors Influencing of College Sci-Tech Achievement Transformation Resistance-Based on the Perspective of Researchers’ Perceived Risk. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Education, Economics and Management Research (ICEEMR 2017), Singapore, 29–31 May 2017; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2017; pp. 144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, L.; Sjödin, D.; Parida, V.; Jovanovic, M. Conceptualizing Business Model Piloting: An Experiential Learning Process for Autonomous Solutions. Technovation 2023, 126, 102815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, Z. The Crux of the Transformation of Scientific and Technological Achievements in Universities and Its Resolving Logic. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2022, 42, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Fang, L. Restrictive factors and countermeasures for the transformation of scientific and technological achievements in universities. Chin. Univ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 11, 77–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattnaik, S.; Mmbaga, N.; White, T.D.; Reger, R.K. To Entrepreneur or Not to Entrepreneur? How Identity Discrepancies Influence Enthusiasm for Academic Entrepreneurship. J. Technol. Transf. 2024, 49, 1444–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ma, Y.; Sun, Y. The Role of Intellectual Property on Enterprise-Led Industry-University-Research Institution Cooperation: Case of Innovation Awards in China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousfiha, M.; Berglund, H. Micro-Transitions and Work Identity: The Case of Academic Entrepreneurs. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2025, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaire, P.N.; Tiwari, U. Evolution and Distribution of Business Incubators: A Literature Review. BIC J. Manag. 2025, 2, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Yu, L. Characteristic and Enlightenment on Universities Collaborative Innovation Mode of Japan Shikoku Area. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, T.; Inai, K.; Kutsuna, K.; Adhikary, B.K.; Buzás, N. Technology Transfer Performance: A Comparative Analysis of Two Universities in Japan. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2022, 90, 78–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).