Abstract

In an increasingly interconnected world, the capacity of societies to withstand, adapt to, and recover from crises is a central challenge for security and sustainable development. Yet, despite extensive research on resilience, the mechanisms through which systemic vulnerabilities emerge and propagate across social domains remain poorly understood. This paper addresses this gap by proposing a network-based framework: the Complex Analysis for Socio-Environmental Adaptation (CASA), which models resilience as a graph-structured system. Each node in CASA represents a social or infrastructural component whose resistance is derived from indicators of installed capacities, while edges capture interdependencies among sectors. We formalize a damage propagation model in which the loss of capacity in one node dynamically affects connected components, revealing the topological patterns that drive systemic fragility. Comparative simulations demonstrate that CASA’s topology amplifies the impact of highly connected nodes, rendering them crucial for resilience planning. An application to a real-world case demonstrates how initial disruptions in access to drinking water cascade into governance, economic, and social instabilities. The results provide both theoretical and operational insights, highlighting that resilience depends not only on the strength of individual components but also on the network architecture that links them. CASA thus offers a replicable and data-informed approach for identifying drivers of social conflict and guiding anticipatory resilience strategies in complex territorial systems.

1. Introduction

Social resilience is crucial in today’s highly interconnected world, where interdependence increases exposure to systemic vulnerabilities. Understanding how resilience operates and developing ways to quantify it are therefore of central importance [1,2].

Among the many definitions of resilience, we adopt the concept of adaptive resilience, which refers not only to a system’s capacity to maintain or recover from shocks [3] but also to its ability to learn from past crises and incorporate this information into future responses [4]. Adaptive resilience emerges from continuous interactions between a system and its environment and is closely aligned with the theory of Complex Adaptive Systems (CAS) in complexity science, pioneered by Holland [5] and Gell-Mann [6].

Resilience is also intimately linked to security, understood as the capacity of communities, states, and international institutions to anticipate, withstand, adapt to, and recover from crises at different scales [7]. Integrating resilience measures into critical infrastructures and social systems has been shown to reduce vulnerabilities and strengthen stability across sectors [8]. Such findings underscore the need for multidimensional approaches that combine anticipation, preparedness, and adaptation to future threats.

From an adaptive perspective, societies with longer historical trajectories may exhibit greater resilience; however, this capacity depends not only on their age but also on how subsystems, such as organizations, infrastructures, and governance mechanisms, can integrate past experiences. Resilience, therefore, emerges from cross-scale interactions, where individual, community, and institutional responses must be articulated to confront socio-environmental pressures, whether natural or human-made.

Thus, administrators of social systems facing critical events must understand how their historical context translates into territorial and community resilience [9], which is unique to that society in that specific territory and dependent on the capacities installed at various scales and sectors. Our work addresses a significant part of this task by developing a general descriptive framework to comprehend the installed resilience capacities at different scales and how they collectively operate to enhance the global emergent resilience of the system. Once the resilience of a society is quantified, establishing its initial condition to confront future critical events becomes essential. Therefore, understanding and analyzing the interdependence among its components, that is, addressing the dynamic characteristics of resilience in that system to understand how this initial condition reacts to future events, is the main objective of this study, focusing on the dynamics within the descriptive framework mentioned above.

Again, the theory of CAS provides a valuable perspective here, as it encompasses two fundamental concepts related to system dynamics: robustness, which allows these systems to withstand stresses without interruption, and antifragility, which strengthens them in the face of such challenges [10]. Furthermore, complex adaptive systems are characterized by a heterogeneous and modular nature, which is crucial for our work, as different social sectors, possibly with various installed capacities and interconnected modularity, will naturally emerge. Thus, when considering social systems as adaptive, resilience can be defined by their capacity to absorb, recover, and adapt to different pressures while maintaining their structural integrity, akin to their identity. This involves flexibility, redundancy, and establishing diverse connections between associated social components.

In order to achieve the objectives described above, in this paper we introduce the Complex Analysis for Socio-Environmental Adaptation (CASA) model developed by our group [11], as a conceptual framework, based on the analysis from the complex adaptive systems perspective, encapsulating the fundamental interactions of the social system that determines its different sectoral states and respective resilience capacities. The CASA model is introduced as a tool to understand the resilience capacities of the social system installed in its individuals, territory, institutions, and critical infrastructure [12]. Although our current model does not yet incorporate a feedback loop within the system’s own dynamics, this insight is crucial to strengthening territorial and community security, as well as to enhancing social resilience by identifying vulnerable and robust components. This could increase society’s capacities to reorganize and strengthen its functions, enhance structures, and identities in situations involving complex dynamics of event propagation associated with an initial critical event.

Indeed, the cascade of events in interdependent systems is a phenomenon that can lead to catastrophic consequences if not managed properly [13]. It is well known that Complex Systems, given their heterogeneous architecture of relationships, are robust against random attacks but very sensitive to a focused attack on a critical component, causing propagation of failures through the interconnected system, amplifying the initial impact and complicating the system, its functions, and its recovery [14]. This is where the importance of studying the dynamics of the proposed descriptive model lies.

The proposal of a model like CASA, which evidences the social resilience capacities installed in a territory, interconnected and dynamic as a whole, transforms the proposed framework into a valuable tool to face critical events better. This is our central working hypothesis. By “feeding” the CASA model with specific historical data on the capacities installed in a specific territory, the CASA architecture can become a powerful tool for analyzing capacities within a social system, predicting the impact of critical events on specific society sectors, and finally, due to its interconnected nature, evaluating the dynamics of failure propagation.

The structure of this paper is as follows: the next section introduces the CASA model. The following sections provide an analysis of the structure of the proposed dynamic model and the results of applying this model to different scenarios, including a real case. The final sections focus on discussion, summarizing our conclusions, and the research opportunities offered by this methodological approach.

2. Related Work

As we mentioned in the previous section, understanding resilience in social systems requires an integrative perspective that combines network science, an interdisciplinary approach, and applied frameworks for urban and community resilience. During the past two decades, several conceptual and quantitative models have been developed to evaluate and improve the ability of societies and cities to absorb, adapt to, and recover from systemic disruptions. This section reviews key resilience models and frameworks and positions the CASA model within this broader scientific landscape.

Resilience thinking emerged from ecological sciences [15,16,17], emphasizing adaptive capacity and feedback between systems and their environments. Later, urban and social applications adopted these ideas to analyze interdependencies across infrastructures, governance, and communities [18,19]. These perspectives evolved into operational frameworks designed to support decision-making and policy interventions [12,20].

The City Resilience Framework (CRF), developed by Arup and the Rockefeller Foundation [21], conceptualizes resilience through four key dimensions: Health & Wellbeing, Economy & Society, Infrastructure & Environment, and Leadership & Strategy. It provides a diagnostic tool to evaluate strengths and weaknesses in urban systems and to prioritize interventions. Similarly, The United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction has advanced global efforts through the Making Cities Resilient 2030 (MCR2030) initiative [22], which provides a structured pathway for local governments to strengthen disaster risk reduction capacities and align with the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction. MCR2030 offers cities a roadmap to enhance their resilience across three progressive stages: commit, plan, and implement; supported by partnerships, peer learning, and performance monitoring. Its framework builds upon earlier programs such as the Making Cities Resilient Campaign (2010–2020) and complements models like CRF and OECD’s Resilient Cities Project by emphasizing governance maturity, local ownership, and evidence-based progress tracking. Within this landscape, CASA contributes as a quantitative modeling complement to these global, policy-oriented frameworks, offering a dynamic and data-driven approach to simulate the evolution of resilience and its cascading impacts.

Parallel to these conceptual models, quantitative frameworks based on complex systems and network theory have emerged. Liu et al. [14] provided a comprehensive synthesis of network resilience, emphasizing that interdependence across critical infrastructures amplifies systemic fragility. Anwar et al. [1] introduced a systems-thinking approach linking social facilities and utilities, revealing that structural vulnerabilities arise from interaction patterns rather than component fragility alone. Similarly, Hurst and MacDermott [13] and Feng et al. [23] analyzed cascading failures in interdependent infrastructures, showing that resilience depends on topological robustness and redundancy.

The ARISE model [24] marked a crucial step toward integrating social and environmental dimensions, providing a framework for Analysis of Resilience for Integrated System Effectiveness. CASA builds directly on this lineage, expanding ARISE’s conceptual base by incorporating network dynamics, propagation mechanisms, and metadata-driven indicators (e.g., affected subjects and categories). Unlike ARISE and CRF, CASA explicitly models the temporal evolution of damages across a connected graph of social sectors, allowing for the simulation of cascading failures and identification of conflict drivers under different stress scenarios.

The Complex Analysis for Socio-Environmental Adaptation (CASA) model represents a methodological synthesis between conceptual frameworks like CRF and ARISE and quantitative approaches rooted in network theory. CASA’s novelty lies in integrating dynamic propagation of damages, multiscale sectoral interdependencies, and empirically derived resilience indicators to quantify how disturbances spread across social systems. By simulating cascading effects and mapping affected subjects and categories, CASA provides a causal, data-driven framework that bridges the gap between abstract theory and actionable policy tools.

In this sense, CASA extends beyond traditional static models by explicitly addressing temporal dynamics, systemic feedbacks, and the structural determinants of vulnerability. This approach aligns with recent efforts to integrate complexity science into resilience governance [25,26], promoting a paradigm where resilience is not only a capacity to recover but a property emerging from the continuous adaptation of interconnected systems.

3. Proposed Approach

The CASA model offers an advanced methodology grounded in Complex Systems Theory, positing that the social system of a territory functions as an adaptive entity with evolutionary characteristics.

Operationally, CASA serves as a quantitative and dynamic model, utilizing indicators across social, economic, structural, environmental, technological, political, energy, cultural, and other dimensions to visualize system behaviors and mechanisms, including causal relationships and decision-making processes. Although the conceptual framework draws inspiration from complex adaptive systems, where feedback loops are central, the present implementation models only the feed-forward propagation of impacts. The analytical principles underlying CASA can also contribute to broader frameworks for anticipatory modeling and decision support in complex, uncertain environments. By integrating counterfactual reasoning and adaptive network analysis, such approaches could enhance our collective capacity to understand, simulate, and respond to emerging systemic disruptions. Future work will extend CASA to include adaptive feedback and recovery dynamics [15,16,17].

In practical terms, the CASA model is a connected graph of social resilience components designed to capture the interactions among key elements identified in various social resilience models, such as the ARISE model, which provided the foundational framework [20]. Unlike traditional models, where components are often considered in isolation, CASA integrates these elements into a network that spans multiple scales. This interconnectedness is essential for modeling the structure and dynamics of social resilience within a territory, forming a quasi-universal architecture based on the methodologies used to establish these connections.

The initial phase consisted of identifying specific resilience elements, with the ARISE model as the primary reference due to its comprehensiveness. Advanced text analysis and automated processing techniques were employed to detect the co-occurrence of these elements in the global scientific literature over the past 14 years [11]. This process involved using keyword combinations related to each component and subsequently mapping these connections across extensive scientific databases. After analyzing over 70 million Web of Science scientific documents from diverse fields, the Maximum Spanning Tree (MST) algorithm [27] was applied to reduce the complexity of the resulting densely connected co-occurrence network while retaining its essential structure. The MST algorithm prioritizes connections that maximize node connectivity based on the highest weight or frequency of co-occurrence, ensuring that all elements remain linked by the most significant relationships while discarding less relevant or weaker ones.

Subsequently, these elements were mapped to sectors and pillars—higher levels within the ARISE base model—using a structured dictionary [28]. This transformation of connections between elements into connections between sectors and pillars preserves a high-level representation of the system’s structure. Understanding these high-level networks is crucial for analyzing interactions between different areas or dimensions of the social system. These networks were pivotal in identifying critical higher-level connections that might have been overlooked following the MST application. To address this, a reverse dictionary transformation was applied to reconnect these essential components, ensuring that interactions are maintained across all scales. This approach ensures that the CASA model not only retains the structure of the original model but also expands it to incorporate a more detailed view of system interactions at multiple scales, thereby enabling a deeper and more applicable analysis of the social resilience within a territory. For more details on the methodology for constructing the CASA graph, see [29].

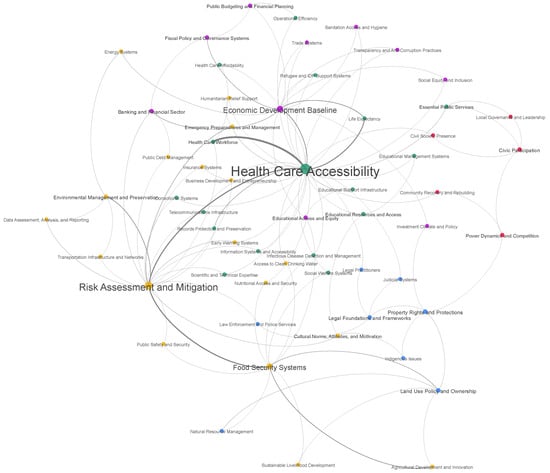

As depicted in Figure 1, the CASA model enables the study of various sectoral characteristics of society concerning resilience but under a systemic view. In this case, it is clear that certain components, such as Health Care Accessibility, Risk Assessment and Mitigation, Food Security Systems, and Economic Development Baseline, play a fundamental connecting role in the framework of elements that define social resilience. The systemic nature of CASA is essential to our work, as we understand this connected structure as a requirement for achieving social resilience. In other words, weakness in one or more components weakens the resilience potential of the complete social system.

Figure 1.

CASA Model. Node size represents the number of links. Node color represents communities detected by [30] algorithm: “Governance and Economic Development” (purple), “Legal issues” (blue), “Social Infrastructure and Public Services” (green), “Community Empowerment” (red), “Sustainable Development and Risk Management” (yellow). The width of links (weight) represents the strength of the relationship, determined by the frequency of co-occurrence that determined it.

Although the structure of the CASA network could be quasi-universal, due to the methodology that considers global scientific knowledge for its construction, its applicability does depend on the properties of the society that inhabits a territory. Thus, the conjugation between the resilience capacities of a territory, defined by a value R for each component dependent on public-historic data, superimposed on this relational structure, allows us to evaluate the resilience characteristics of a territory (and its society) at a specific point in time, highlighting the descriptive nature of the framework. On the other hand, it is possible to analyze how this resilience responds to specific failures or attacks by employing the CASA model’s framework alongside data specific to a particular social system within a territory. Thus, the model allows us to investigate the dynamics of damage propagation in response to different events impacting various sectors (nodes or communities) of society.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Damage Propagation Model

To analyze damage propagation between the different components of CASA, we introduce a dynamical model that considers the interaction between the R value, and an effectation A coming from another node(s). Each node starts with a positive initial resistance, defined within the interval , representing the capacities installed for resilience in a territory for each node to withstand an impact. The R calculation is the average of a series of normalized indicators, obtained from qualitative questions, indices, or rates, that represent the installed capacities in a specific dimension of social resilience (i.e., CASA element). The R value corresponds to the node metadata used to calculate damage propagation; other metadata of CASA elements are used to qualify this propagation, as will be discussed later. The set of indicators for each CASA element, as well as other metadata, are detailed in the website of the project [29].

The propagation of damage between nodes in the CASA model is highly dependent on the graph’s architecture, as it dictates the possible paths (set of links) through which damage can spread and influences the intensity of the propagation, which is more pronounced when the damage traverses strong links (i.e., links with high weight) such as the one between Health Care Accessibility and Health Care Workforce shown in Figure 1. Conversely, the intensity of the damage is inversely proportional to time step simulation (t). This relationship is captured in the following propagation equation, which determines the resistance of a node i, , after receiving an affectation:

where is the resistance of the node i at time t, corresponds to the resistance of the node i at the previous iteration step , to the affectation of a node i coming from the j node to wich i is directly connected, to the weight of the link between nodes i and j that are directly connected. The sum extends to all j nodes that are directly connected to node i; the total number of nodes will be the degree of node i, . Finally, t corresponds to the time or iteration step of the model.

In Equation (1), if then will become negative, indicating that the node is considered “damaged.” In this scenario, the damaged node will propagate as damage to its neighboring nodes in the form of an impact, or affectation A. This process illustrates how a damaged node spreads the loss of its capabilities. For instance, if a node represents the number of people managing a system, its failure would result in damage equivalent to losing that number of people in their workplace. According to [31], this damaged state reflects the vulnerability of the CASA element since it depends on the magnitude of the damage, in this case, the total loss of its capabilities. We are aware that this is a major simplification since all the elements of CASA are fragile (i.e., they are susceptible to being damaged) and a partial loss of capabilities can also affect other elements of the network; however, this first version of the propagation model allows us to elucidate other essential behaviors.

Finally, we have established a memory mechanism in the model that prevents a node attacked in the previous step from receiving the same attack, coming from the same node, at the current time. This memory mechanism operates as a procedural constraint rather than an adaptive feedback process. It prevents redundant propagation paths, but does not represent a true learning or recovery dynamic. In future extensions, CASA will explicitly model adaptive mechanisms by allowing nodes to modify their resistance or connectivity in response to accumulated impacts, thus introducing genuine feedback and recovery processes consistent with complex adaptive systems theory.

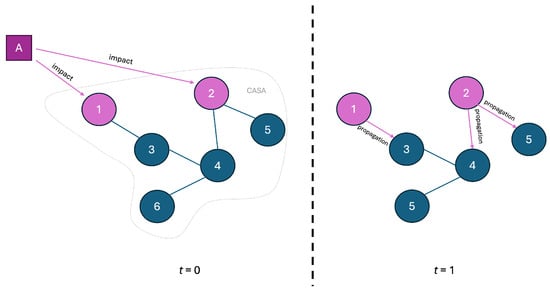

The propagation, described by Equation (1), begins at , following the initial impact on the CASA graph at . This initial impact represents the effect of a specific phenomenon (natural or human-made) on one or more nodes of the CASA graph and serves as the starting condition for propagation (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the damage propagation in CASA model. At CASA graph is impacted by an event affection A. Nodes 1 and 2 (purple color) are damaged by A. At propagation damage occurs from node 1 and node 2. At this step, node 1 could affect node 3, and node 2 could affect nodes 4 and 5.

It is important to note that the initial impact is always greater than the resistance of the impacted node(s); so, they begin propagating to their neighbors. As seen in Figure 2, the impact of event A causes damage to nodes 1 and 2 at . Subsequently, damage propagation spreads to the neighbors of the previously impacted nodes according to the Equation (1).

4.2. Analysis of CASA Topology and Its Effect on Propagation

To analyze the effect of topology, we compare the propagation of damage over the CASA graph with the propagation of similar damage over a graph with the same number of nodes and links but randomly redirected. In this comparison, we work with a “homogeneous” version of the CASA graph (and its random version), i.e., we give all nodes a resistance and a link weight to all pairs of connected nodes.

The damage to resilience components can be interpreted in several ways. The simplest approach involves quantifying the number of damaged nodes over time, which reflects the propagation of the damage. However, in this work we also introduce two measures related to the loss of the connectivity of the CASA graph due to the node damage. Under our approach, the connected-structure of CASA is a minimum to define the social resilience capacity of a society. This means that the damage to one or more nodes represents the loss of that connected property and, therefore, the “fracture” of the social resilience system. To quantify this fracture, we analyzed two topological properties of the CASA network during damage propagation: (i) the number of isolated components (i.e., one or more nodes connected between them but disconnected from others) that reflects the level of fracture of the network; and (ii) the number of CASA elements that continue to be part of the larger connected structure (named “giant component”) that reflects the robustness of the resilience system.

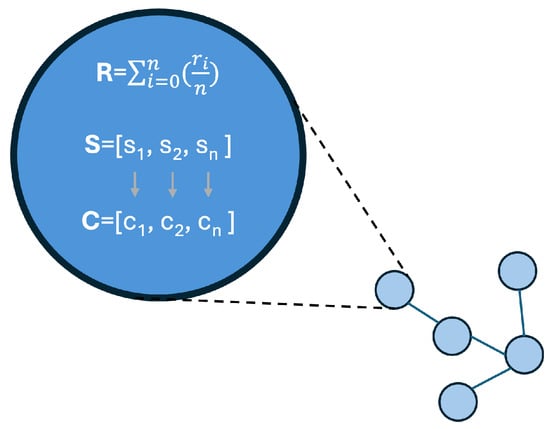

4.3. Social Drivers of Conflict

To unveil drivers of conflict, the propagation model uses a second set of node metadata. As explained in the previous section, each node is characterized by a resistance value R, which plays a role in the propagation Equation (1). This resistance value is obtained by averaging the values, = [0, 1], of each historical indicator that describes the installed resilience capacities in the node. For each of those indicators, an affected subject, , was established (Table 1). With this information, each affected subject was classified into one or more of the five categories : material, social, economic, legal, and governance. Thus, S and C complete the node metadata (Figure 3).

Table 1.

Examples of affected subjects for selected CASA elements and their category (s = social, l = legal, m = material, g = governance, and e = economic). For a complete version of each CASA element metadata, see [29].

Figure 3.

Detail of node’s metadata. Resistance R, affected subjects S, and associated categories C.

In the damage propagation model, when a node is damaged, that is , the affected subjects of the damaged node are saved in one(s) of the lists corresponding to each category in each iteration, as long as its value is less than the impact received. The final result is listed by category with the frequency of affected subjects, e.g., . Finally, analyzing these lists will provide us with the main potential drivers of social conflict derived from the spread of damage over the network.

4.4. Real Case Analysis

In order to analyze the proposed model in a real-world case, we examined a locality in central Chile that faces serious environmental problems, including both pollution and water scarcity. The Puchuncaví commune, located at 32°43′34″ S, 71°24′54″ W, is often characterized as a “Sacrifice Zone” due to its enduring environmental stress, as highlighted by [32,33]. The social and environmental damage that occurs due to industrial pollution and drought conditions in an eminently agricultural area is a source of social instability. For this work we used data collected by a councilor of the commune of Puchuncaví during the months of April and May 2023. The list of indicators and R values used in this analysis are available in [29].

5. Results

This section presents the results of the damage propagation analysis on the CASA model. First, it is essential to note that, as explained earlier, the topology of the CASA graph is derived from a bibliographic analysis over a massive scientific knowledge database, which justifies the interaction of each sector of society represented by a node. Additionally, each node, affected by the propagation of events, incorporates different societal characteristics through historical public data. It is essential to note that, in its current version, CASA models only the forward propagation of impacts based on fixed dependencies and does not yet incorporate dynamic feedback or adaptive recovery. Therefore, the results should be interpreted as structural vulnerability analyzes rather than adaptive behavior simulations.

We will begin by presenting an analysis that highlights the impact of topology on the propagation of failures. To do this, we will compare the topology of CASA graph with random networks, allowing us to demonstrate the model’s strengths. Following this, we will show the damage propagation for a real-world case along with a subsequent analysis of the emerging potential drivers of social conflict.

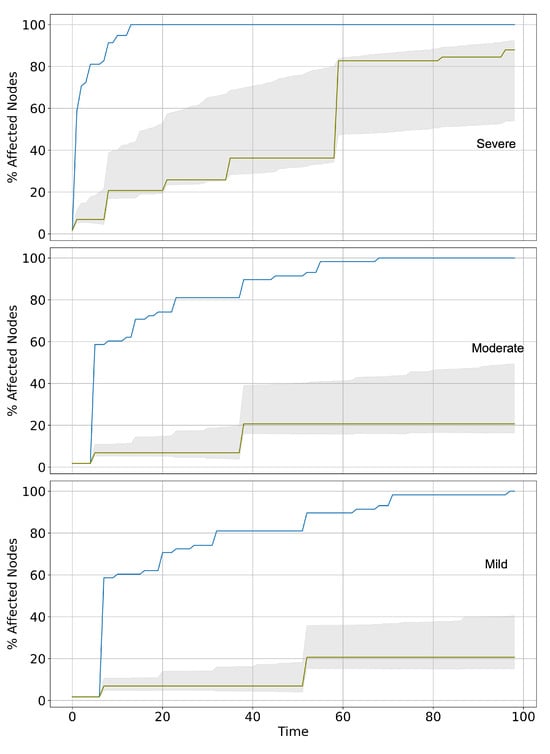

5.1. The Effect of Network Topology

Figure 4 shows the spread of damage when hitting the Health Care Accessibility (blue line) and Power Dynamics and Competition (green line) nodes, for severe attack (100% of damage is spread, top plot), medium spread ( of damage is spread, middle plot), and mild spread ( of damage is spread, bottom plot). Notice that this modulation that generates these three scenarios, severe, medium, and mild attack, only operates in the first moment of propagation .

Figure 4.

Damage propagation on the CASA model in a homogeneous scenario when the attack is on a very connected node and a poorly connected one. Percentage of affected nodes: severe (top), moderate (middle), and mild attack (bottom) on a highly connected component (Health Care Accessibility, blue line) and other poorly connected (Power Dynamics and Competition, green line). The Grey zone represents the average behavior of affected nodes as a result of 100 simulations on a random version of the CASA model. Simulations implemented in a homogeneous context, Resistances = 1, Weights = 1.

As can be seen, the propagation speed follows an expected behavior, being faster in the “severe” case and slower in the “mild” case; in both simulations, an impact is observed on a highly connected node (Health Care Accessibility) and another poorly connected to the rest (Power Dynamics and Competition). However, the importance of connectivity in the scope of the damage is striking. The figure shows how the impact on a node with many connections allows the damage to reach all the nodes (blue line) sooner or later. The same does not occur with an impact on a poorly connected node, where the damage fails to spread through the network, especially if the attack is medium or mild. It is interesting to note how the distribution of links in the network also plays a role in propagation. When comparing the speed of damage propagation in the network with random links with severe attacks, we observe that it occurs slowly, statistically similar to the propagation that begins in a node with few links by distributing responsibility among the components of the social resilience system.

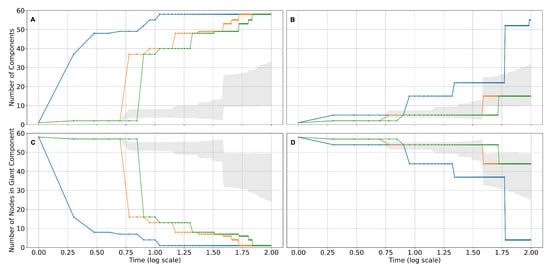

Figure 5 shows two related topological properties for the same cases as the previous analysis. The top and bottom plots on the left side of Figure 5 show the number of isolated components that appear when the network fractures due to damage to the nodes over time. The right top and bottom plots show the number of nodes that make up the giant component of resilience that remains when the network fractures due to damage to the nodes.

Figure 5.

Damage propagation on the CASA model in a homogeneous scenario when the attack is on a very connected node and a poorly connected one. Number of components (A,B), and Number of nodes belonging to the giant component of resilience (C,D) for severe (blue line), moderate (orange line), and mild (green line) attacks on a highly connected component (Health Care Accessibility, (A,C)) and other poorly connected (Power Dynamics and Competition, (B,D)). The grey zone represents the average behavior of 100 simulations on a random version of CASA model under medium attack. Note that a logarithmic time scale was used to make the difference between attack severities visually clear.

As can be seen, severe attacks show severe fractures in the resilience system where many components are quickly isolated from the rest and where the giant component loses size rapidly. The figure also shows that in the case of an attack on a highly connected node, such as Health Care Accessibility (top row), it generates fractures much higher than those of a resilience structure with random links and much worse when the initial impact occurs in a node with few connections (bottom row).

In the case of an attack on a highly connected node, we observe that the fracture of a random version of CASA is much less severe. This is compared to the fractures caused by medium and mild attacks on poorly connected nodes (bottom plots).

As the analysis shows, resilience is dynamic and shaped by structure and connectivity among system components. By examining damage propagation, the model reveals that vulnerability often hinges on network topology, where highly connected nodes—such as critical infrastructure or governance elements—play a significant role in either sustaining resilience or, when compromised, accelerating system-wide collapse [14]. This insight underscores the importance of these key nodes in resilience planning, as their failure can trigger cascading effects that destabilize the broader system.

CASA’s network topology plays a critical role in determining resilience outcomes. Comparisons between CASA and randomized networks reveal that highly connected systems can enhance resilience or hasten damage propagation, depending on the affected nodes. For instance, highly connected nodes like Health Care Accessibility represent crucial resilience points. If disrupted, they can lead to widespread consequences, as demonstrated by simulations in this study. In contrast, decentralized or less connected nodes spread failures more slowly, highlighting the importance of distributed, redundant systems in strengthening resilience [23].

This study also highlights sectoral inter-dependencies. CASA underscores how various social sectors—healthcare, infrastructure, governance, and economy—are interconnected. This means that a failure in one sector, like energy, can cascade across the system, affecting healthcare, governance, and social stability. CASA’s ability to model these interconnections makes it a valuable tool for policymakers aiming to prevent cascading failures. This functionality is particularly relevant for crisis management and policy design, where understanding failure propagation is essential for maintaining social stability [1].

5.2. Real Case Analysis: Access to Drinking Water in Puchuncaví, Central Chile

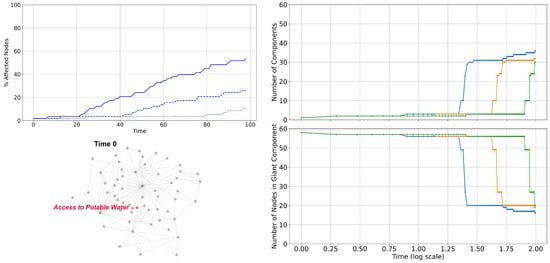

In this section, we present the results of applying the damage propagation model on CASA “fed” with real data on its resilience capacities. In particular, we consider the damage propagation that initially affected access to potable water in Puchuncaví, on the coast of central Chile.

Figure 6 presents the results of the simulation carried out in Puchuncaví by applying the CASA model and simulating the propagation of damage affecting initially the access to drinking water, considering different intensities of the attack (severe, medium, and mild). The top right plot of the figure shows the percentage of components of the CASA social resilience system damaged over time. As can be seen, the spread of damage is faster in a severe attack (continuous line) than in a medium or mild attack (dashed and pointed lines, respectively). On the other hand, this simulation highlights the role played by the capacities installed in the components of the territory (R values) and the weights in the links that relate to them. When comparing the results with those in Figure 4, whose composition was homogeneous in R values and the weight of the links, we can see that the damage spread is slower over time in the case of an attack on a highly connected node.

Figure 6.

Damage propagation on the CASA model in a real scenario after an initial impact on Access to Clean Drinking Water in Puchuncaví, central Chile. (Top left): Percentage of affected nodes for severe (continuous line), moderate (dashed line), and mild attack (pointed line). (Bottom left): CASA graph at time t = 0 affected in the Access to Potable Water. (Top Right): Number of components of CASA graph over time. (Bottom right): Number of nodes belonging to the giant component of the CASA graph. Severe (blue line), moderate (orange line), and mild attack (green line). Note that in the bottom figures, a logarithmic time scale was used to make the attack severity difference clear.

A similar behavior concerning the homogeneous case is observed in the fracture of the CASA resilience network, both in the number of isolated components (top right plot of Figure 6) and in those that belong to the large connected component (bottom right plot of Figure 6). In both cases, the fracture of the network is slower over time in the case of an attack on a highly connected node. However, the figure shows that the reaction times are considerably different concerning the magnitude of the damage, with the severe attack being two times faster in fracturing the network than the mild case. On the other hand, we observe a similar behavior between all the attack levels, where there is an abrupt change from damage that leaves 3% of nodes isolated and a giant component that brings together almost 55% of the resilience components to a fractured network with more than 30 isolated components and a large component that brings together only 20% of them.

Real-world analyses, such as disruptions in critical sectors (e.g., water access in central Chile), illustrate how failures in one area can cascade, amplifying initial impacts and revealing complex interdependencies within social resilience networks. For example, in Puchuncaví, historical environmental degradation and limited access to essential services have sparked social unrest, showing how local issues can escalate into broader conflicts if unaddressed. CASA’s integration of historical data on past failures and environmental stresses makes it well-suited for analyzing systems facing recurring challenges, such as frequent natural disasters or long-term degradation [20]. This feature allows policymakers to design interventions that address immediate vulnerabilities and long-term resilience needs.

Furthermore, CASA’s adaptability allows it to respond to systemic changes over time. By incorporating historical data on capacities, the model remains relevant for systems facing long-term stresses, such as climate change, political instability, or pandemics. This adaptability aligns with resilience theories emphasizing recovery, learning, and adaptation to improve future resilience [16]. CASA reflect the real-world complexities of socio-ecological systems, where resilience involves recovery and transformation in response to emerging challenges.

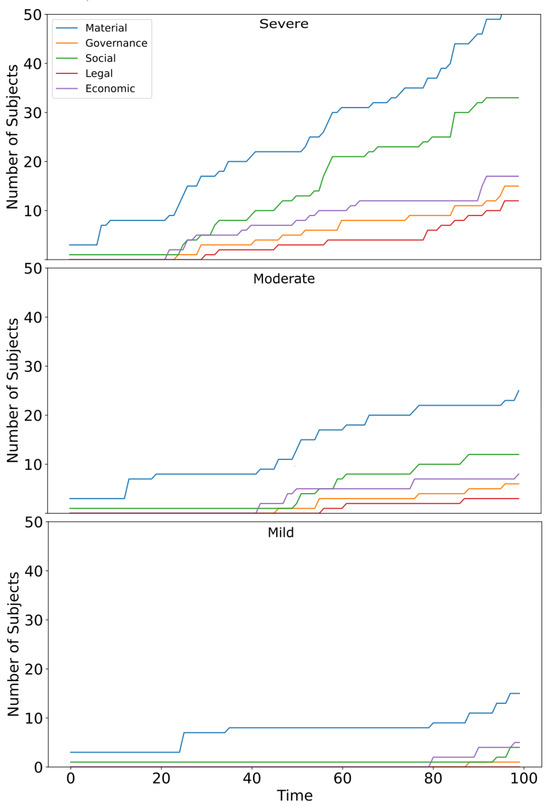

Finally, perhaps the most interesting results of this simulation with real data about installed capacities in the territories are the damages caused to the affected subjects (see Figure 7), potential drivers of social conflict. As can be seen, in severe and moderate attacks, the primary damage occurs at the infrastructure or material level (blue line), followed by damage of a social nature (green line), which triggers economic damage (purple line), governance damage (orange line), and finally legal damage (red line). In the case of the mild attack, the damage appears only at the material level.

Figure 7.

Categories of social conflict drivers that appear during the simulation of a severe impact on Access to Clean Drinking Water in Puchuncaví, central Chile. Number of affected subjects over time for a severe attack (top), moderate attack (middle), and mild attack (bottom). Subjects are separated by categories: Material (blue), Governance (orange), Social (green), Legal (red), and Economic (purple). Simulations correspond to the same scenario as Figure 6.

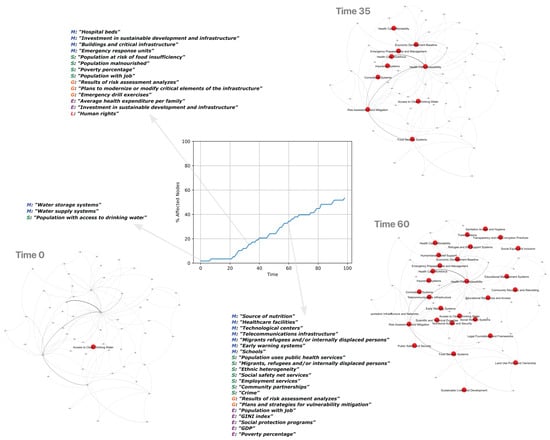

Our analysis of affected subjects shows that the initial material damage begins to affect different components of the resilience system’s social, economic, governance, and legal elements. At the beginning (t = 0), when the damage to the access to potable water affects the CASA model, material or infrastructure components such as “water storage systems”, and “water supply systems” are affected. Also, social subjects such as “population with access to drinking water” are obviously affected. However, as time passes, other material, social, economic, governance, and legal components appear affected by the inaccessibility of drinking water, becoming potential drivers of social crises, as depicted in Figure 8. For example, at t = 60 of the simulation, the model already shows problems in health, education, and telecommunications infrastructure. On the other hand, social issues associated with employment and safety services are already evident; governance problems associated with vulnerability mitigation; and economic problems related to inequality, and protection programs are also beginning to appear.

Figure 8.

Drivers of social conflict that appear during the simulation of a severe impact on Access to Clean Drinking Water in Puchuncaví, central Chile. Percentage of affected nodes and some affected subjects appearing during the simulation. CASA graphs are displayed with affected nodes (red) for the same time steps.

The model shows that initial material damages, such as infrastructure failures, often lead to broader consequences. For example, water scarcity can escalate into governance issues, social unrest, and economic disruption, as seen in Puchuncaví [34,35]. By tracking impacts across sectors, CASA helps identify conflict drivers, enabling policymakers to develop effective strategies for mitigating social tensions. These findings align with research advocating for resilience strategies that consider local system characteristics [20].

6. Conclusions

Building on the structural foundations of CASA introduced in [11], this study advances the model by explicitly incorporating propagation dynamics and conflict drivers. The CASA model offers a comprehensive framework for understanding and enhancing resilience within complex socio-environmental systems. This perspective emphasizes that resilience emerges not in isolation but from the dynamic interactions between interconnected sectors such as infrastructure, healthcare, governance, and economic networks [15,16]. Through network modeling and failure propagation simulations, CASA identifies vulnerabilities and resilience points under stressors like natural disasters, economic downturns, and social conflicts.

The CASA model offers a dynamic, promising approach to strengthening social resilience. Leveraging complex systems theory provides a detailed, multiscale analysis that captures interdependencies within social systems. CASA’s capacity to simulate sectoral disruptions, incorporate historical data, and adapt to evolving stresses makes it valuable for addressing global challenges like climate change, pandemics, and political instability. These features position CASA as a critical asset for informed decision-making and policy development.

The model’s emphasis on network topology underscores the need to safeguard highly connected hubs, such as healthcare or governance structures, in resilience planning. Additionally, CASA’s simulation of failure propagation across sectors is crucial for crisis management, helping identify cascading failures and design mitigation strategies. Insights from CASA can guide the development of resilient infrastructure and social systems, contributing to building more adaptable societies.

This study also identifies areas for future research. While CASA is a powerful tool, its effectiveness depends on the quality and granularity of input data. CASA’s predictions may be less reliable in regions with limited or outdated data. Future work should focus on improving data collection, analysis of the propagation of partial damage between CASA elements, introducing non-linear aspects in the propagation equation, and integrating real-time data to enhance the model’s predictive power. Furthermore, CASA would benefit from refined treatment of nonlinear, feedback-driven, and emergent behaviors, which are characteristic of Complex Adaptive Systems but challenging to model quantitatively. In forthcoming work, we plan to introduce adaptive coupling terms, node recovery dynamics, and feedback-based propagation to align CASA’s formal implementation with its complex systems theoretical foundations.

In conclusion, CASA provides a valuable approach to enhancing social resilience through a detailed system dynamics analysis. As global challenges threaten societal stability, models like CASA will play an increasingly vital role in guiding decisions and shaping resilient policies. This study advances theoretical understanding and offers practical applications for building secure, adaptable societies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.F., J.P.C. and R.M.B.; methodology, J.P.C., M.F., G.O. and R.M.B.; software, J.P.C. and G.O.; investigation, I.F., J.P.C., M.F., S.S., C.U., G.V. and E.R.; data curation, G.O.; writing—original draft preparation, I.F., J.P.C., M.F. and R.M.B.; writing—review and editing, M.F., E.R. and J.P.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Office of Naval Research (ONR) under Grant 14396746, and partially funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (Contract No. PID2021-122711NB-C21).

Data Availability Statement

The data used for the construction of the CASA model are available through the Web of Science interface. In the case of resistance values of Puchuncaví, the data are public.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Anwar, G.A.; Dong, Y.; Ouyang, M. Systems Thinking Approach to Community Buildings Resilience Considering Utility Networks, Interactions, and Access to Essential Facilities. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2023, 21, 633–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Guo, N.; Gao, X.; Wu, F. How Carbon Emission Reduction Is Going to Affect Urban Resilience. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 372, 133737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraccascia, L.; Giannoccaro, I.; Albino, V. Resilience of Complex Systems: State of the Art and Directions for Future Research. Complexity 2018, 2018, 3421529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Broeke, G.A.; van Voorn, G.A.; Ligtenberg, A.; Molenaar, J. Resilience through Adaptation. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, J.H. Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Gell-Mann, M. The Quark and the Jaguar; Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Li, R.; Wang, W.; Qin, T.; Zhou, R.; Fan, W. Concepts, Models, and Indicator Systems for Urban Safety Resilience: A Literature Review and an Exploration in China. J. Saf. Sci. Resil. 2023, 4, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathurshan, M.; Saja, A.; Thamboo, J.; Haraguchi, M.; Navaratnam, S. Resilience of Critical Infrastructure Systems: A Systematic Literature Review of Measurement Frameworks. Infrastructures 2022, 7, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williner, A.; Tognoli, J. Guide for Designing Territorial Resilience Strategies Against Socio-Natural Disasters; Project Documents; ILPES–CEPAL: Santiago, Chile, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.; Gheorghe, A.V. Antifragility Analysis and Measurement Framework for Systems of Systems. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2013, 4, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, M.A.; Cárdenas, J.P.; Olivares, G.; Rasmussen, E.; Salazar, S.; Urbina, C.; Vidal, G.; Lawler, D. Harnessing Network Science for Urban Resilience: The CASA Model’s Approach to Social and Environmental Challenges. Appl. Netw. Sci. 2025, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.K.; Miner, T.W.; Stanton-Geddes, Z. (Eds.) Building Urban Resilience: Principles, Tools, and Practice; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hurst, W.; MacDermott, Á. Evaluating the Effects of Cascading Failures in a Network of Critical Infrastructures. Int. J. Syst. Syst. Eng. 2015, 6, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, D.; Ma, M.; Szymanski, B.K.; Stanley, E.; Gao, J. Network Resilience. Phys. Rep. 2022, 971, 1–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1973, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.; Holling, C.S.; Carpenter, S.R.; Kinzig, A. Resilience, Adaptability and Transformability in Social–Ecological Systems. Ecol. Soc. 2004, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C. Resilience: The Emergence of a Perspective for Social–Ecological Systems Analyses. Glob. Environ. Change 2006, 16, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batty, M. A Generic Framework for Computational Spatial Modelling. In Agent-Based Models of Geographical Systems; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 19–50. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes, F.; Folke, C.; Colding, J. (Eds.) Linking Social and Ecological Systems: Management Practices and Social Mechanisms for Building Resilience; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cutter, S.L.; Barnes, L.; Berry, M.; Burton, C.; Evans, E.; Tate, E.; Webb, J. A Place-Based Model for Understanding Community Resilience to Natural Disasters. Glob. Environ. Change 2008, 18, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arup and The Rockefeller Foundation. City Resilience Framework; Arup International Development: London, UK, 2014; Available online: https://www.arup.com/insights/city-resilience-index/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR). Making Cities Resilient 2030 (MCR2030): A Global Partnership for Local Resilience; UNDRR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://mcr2030.undrr.org (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Feng, K.; Wang, N.; Li, Q.; Lin, P. Measuring and Enhancing Resilience of Building Portfolios Considering the Functional Interdependence among Community Sectors. Struct. Saf. 2017, 66, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, J.R. ARISE Foundational Documents; Infinitum Humanitarian Systems: Seattle, WA, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.ihs-i.com/arise-foundational-documents (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Gallotti, R.; Sacco, P.; Domenico, M.D. Complex Urban Systems: Challenges and Integrated Solutions for the Sustainability and Resilience of Cities. Complexity 2021, 2021, 1782354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A.; Yamagata, Y. Principles and Criteria for Assessing Urban Energy Resilience: A Literature Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 60, 1654–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerini, P.M. The Min–Max Spanning Tree Problem and Some Extensions. Inf. Process. Lett. 1978, 7, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagberg, A.; Swart, P.J.; Schult, D.A. Exploring Network Structure, Dynamics, and Function Using NetworkX; LA-UR-08-05495; Los Alamos National Laboratory: Los Alamos, NM, USA, 2008.

- Complex Society Lab. CASA Model Materials & Methods. 2025. Available online: https://futurecomplexity.com/en/materials/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Blondel, V.D.; Guillaume, J.; Lambiotte, R.; Lefebvre, E. Fast Unfolding of Communities in Large Networks. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2008, 2008, P1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, K. A Beginner’s Guide to Fragility, Vulnerability, and Risk; University of Colorado: Denver, CO, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hormazábal, N.; Maino, S.; Vergara, M.; Vergara, M. Habitar en una Zona de Sacrificio: Análisis Multiescalar de la Comuna de Puchuncaví. Revista HáBitat Sustentable 2019, 9, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivanco, E. Zonas de Sacrificio en Chile: Quintero–Puchuncaví, Coronel, Mejillones, Tocopilla y Huasco. Componente Industrial y Salud de la Población; Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile: Valparaíso, Chile, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- La trampa del agua. Revista Anfibia. 2023. Available online: https://www.revistaanfibia.cl/la-trampa-del-agua/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Municipalidad de Puchuncaví. Informe Diagnóstico Medio Natural. 2016. Available online: https://www.munipuchuncavi.cl/2.0/sitio10/medioambiente/scam/informemedionatural.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).