Abstract

In highly dynamic and information-intensive logistics environments, understanding how firms achieve modeling and simulation ambidextrous innovation (MSAI) through strategic alignment is crucial. Drawing on organizational information processing theory (OIPT), we develop an integrative framework that links strategic congruence with capability development and innovation outcomes. The study examines (1) whether buffering–bridging congruence (B–B congruence) exists and how it enhances MSAI through operational stability, financial flexibility, and knowledge management capability; (2) how these three capabilities shape the differentiated pathways toward exploitative and explorative simulation innovation; and (3) how firms may leverage a simulation-driven decision framework to achieve strategic–capability alignment in the highly dynamic maritime logistics environment. The framework is empirically tested using polynomial regression models based on survey data from Chinese maritime logistics firms, analyzed with SPSS 27.0 and STATA 15. Our empirical results indicate that, regardless of the level of buffering strategy or bridging strategy, the firm’s operational stability, financial flexibility, and knowledge management capabilities are always higher when buffering and bridging strategy are congruent. The results also show that the three capabilities influence MSAI differently. Specifically, knowledge management capability exerts positive effects on both exploitative and exploratory modeling innovation. Financial flexibility mainly promotes exploitative innovation, while its influence on exploratory innovation is not significant. In contrast, operational stability does not enhance exploitative innovation but unexpectedly shows a positive effect on exploratory innovation. The findings advance OIPT’s theoretical application in simulation-intensive settings and offer guidance for firms seeking to align capabilities and strategy in complex systems, providing both theoretical and practical insights.

1. Introduction

In today’s logistics landscape, intensified global competition and rapid technological change expose firms to persistent volatility and uncertainty [1,2]. Modeling and simulation (MS) tools, such as digital twins and data-driven scenario experiments, have become indispensable for decision-making in advanced logistics systems. These technologies allow managers to assess demand fluctuations, test disruption responses, and reconfigure supply networks to enhance adaptability and resilience [3,4,5]. According to organizational information-processing theory (OIPT), firms operating under such turbulence must achieve a fit between their information-processing needs and capacities [6,7,8].

In this context, maritime logistics firms face a strategic paradox: maintaining operational stability while pursuing system innovation through MS. Ambidexterity theory addresses this dual challenge by emphasizing the balance between exploitative and explorative innovation [9,10]. Exploitative innovation refines existing simulation models for greater efficiency and reliability, while explorative innovation uses modeling tools to experiment with novel configurations and technologies [11,12]. Achieving ambidextrous innovation has thus become crucial for sustaining performance amid supply chain shocks and market dynamism [13,14,15].

To manage uncertainty, firms typically rely on two complementary strategies: buffering and bridging [3,16]. Buffering focuses on building internal resource slack, such as safety stock or cash reserves, to absorb shocks and stabilize operations [12,17,18], whereas bridging strengthens external ties to access additional resources, knowledge, and technology [16,19]. Both strategies mitigate risks, yet excessive reliance on either may cause rigidity or high coordination costs [20,21]. Consequently, recent studies highlight the importance of buffering-bridging (B-B) congruence-the alignment of internal and external strategies-as a means to balance information-processing requirements and capacity [21,22,23].

Although research on ambidextrous innovation and B-B strategies has advanced considerably, the two streams have largely evolved independently, leaving their potential interplay insufficiently understood. In particular, existing studies provide limited insight into the capability-building mechanisms through which B-B congruence shapes firms’ modeling and simulation ambidextrous innovation (MSAI). Prior simulation-oriented research has predominantly focused on system-level resilience or risk control, rather than examining how strategic alignment translates into internal capability configurations that support ambidextrous innovation [22]. Furthermore, the nonlinear or asymmetric effects of fit-misfit relationships remain underexplored, restricting our understanding of the dynamic implications of B-B congruence in organizational innovation.

To extend this line of inquiry, we develop an integrative framework grounded in OIPT. The framework is structured around three guiding questions: (1) How does B-B congruence enhance operational stability, financial flexibility, and knowledge management capability to address the heightened information-processing demands of simulation ambidexterity? (2) Do these capabilities exert differentiated influences on exploitative and explorative simulation innovation? (3) How can firms configure strategic resources and organizational capabilities to achieve a simulation-driven balance between exploitation and exploration in a highly dynamic maritime logistics environment?

This framework is empirically tested using survey data from Chinese maritime logistics firms. According to the China Industry Research Network (CIRN, 2025), digital investment among major Chinese ports and shipping firms has grown at an annual rate exceeding 25%, and more than 40% of large enterprises have deployed digital-twin or simulation-based decision platforms [24]. This industry, characterized by high dynamism, capital intensity, and network dependence, provides an appropriate setting for studying strategic alignment and capability development under information-processing challenges [25,26,27].

The findings contribute to research on modeling and simulation in logistics systems in three main ways. First, the study links B-B congruence with OIPT to explain how horizontal strategic fit enhances the capabilities that drive MSAI [8,28,29]. Second, it identifies the heterogeneous effects of operational, financial, and knowledge-based capabilities on exploitative and explorative innovation [30,31,32]. Third, it introduces a methodological advancement by operationalizing B-B congruence through polynomial regression and response surface analysis, allowing for nonlinear assessment of fit–misfit effects [22].

Overall, this study contributes to a deeper understanding of how strategic alignment and capability configuration enable firms to balance control and change within modeling- and simulation-based logistics systems. The findings provide theoretical insight and practical guidance for building more resilient, adaptive, and innovation-oriented supply chain networks.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Buffering Strategy, Bridging Strategy, and Modeling and Simulation Ambidextrous Innovation

In advanced logistics systems, coping with environmental uncertainty requires mechanisms ensuring both stability and adaptability [3,4]. Two essential strategies are buffering and bridging [2,5]. Buffering relies on internal redundancy, such as safety stock and cash reserves, to absorb disruptions and maintain stability [6,7], while bridging emphasizes external collaboration to gain access to resources, information, and technology, thus enhancing adaptability [5,8]. From an information-processing perspective, bridging strengthens the ability to acquire and transfer information, effectively mitigating uncertainty [4,9]. Empirical research suggests both strategies help manage supply chain risks and improve performance [8,10]. However, overreliance on buffering may lead to rigidity and reduced innovation, whereas excessive bridging increases dependence and coordination costs [11,12]. Hence, integrating both is crucial; their dynamic balance allows firms to optimize resource allocation and information processing for sustainable performance and resilience [14,15,16]. These strategies are increasingly applied in modeling and simulation studies on supply chain resilience and system performance [2,17].

Building on this, scholars highlight organizational ambidexterity, the dynamic capability to pursue exploration and exploitation simultaneously, as key to innovation and competitiveness [18,19,20]. In logistics management, ambidexterity involves balancing operational efficiency with exploratory breakthroughs via simulation-based models [21,22]. Structural differentiation or contextual integration of both activities helps firms avoid rigidity and sustain adaptability [18,23]. Empirical findings confirm that balancing exploration and exploitation enhances firm performance and system advancement [25,26,27].

Innovation, therefore, serves as a fundamental driver of system performance and competitiveness [28,29]. The emerging concept of modeling and simulation ambidextrous innovation (MSAI) extends traditional ambidexterity by embedding modeling and simulation as dynamic tools for balancing the two orientations. Through simulation-driven experimentation, firms can predict outcomes, refine operations, and foster continuous learning between models and real-world practices [30,31]. This strengthens adaptability, reliability, and responsiveness.

While exploitative innovation improves efficiency through refinement of existing systems, explorative innovation drives breakthroughs via simulation-based experimentation and digital twins [20,29,32]. MSAI thus represents a paradigm where simulation acts as both an analytical instrument and an organizational capability supporting learning and innovation balance [33,34]. However, tensions persist: excessive exploitation restricts adaptability, while excessive exploration reduces stability [34]. Hence, organizational design and modeling approaches that coordinate both have been shown to enhance long-term resilience and competitiveness [35,36,37]. Recent studies also stress that environmental dynamism, competition, and digital transformation influence this balance [1,18,38]. For instance, Xing et al. (2025) show how dual innovation capabilities moderate the relationship between digital economic development and labor productivity, linking digital innovation to system outcomes [39]. Consequently, the convergence of modeling, simulation, and ambidextrous innovation offers a robust framework for managing complexity and uncertainty in logistics systems.

Despite progress in understanding buffering–bridging (B–B) strategies and ambidextrous innovation separately, theoretical integration between them remains limited. Prior studies rarely examine how B–B congruence facilitates the development of organizational capabilities that enable MSAI. Moreover, few empirical efforts have explored how such congruence shapes the multidimensional capacities (e.g., operational, financial, and knowledge management) necessary for sustaining dual innovation under uncertainty [36,37,38]. As a result, this study proposes a framework linking B–B congruence, firm capabilities, and MSAI. This integrative view not only advances theoretical understanding of strategic fit under information-processing demands but also provides a modeling perspective on how logistics firms can configure resources and learning mechanisms to enhance resilience and innovation in dynamic environments.

2.2. Theoretical Foundation

In highly dynamic and uncertain environments, how firms effectively acquire, process, and utilize information to sustain survival and competitive advantage has long been a central issue in management research. The core proposition of organizational information-processing theory (OIPT) [40] is that, for organizations to operate efficiently in complex and dynamic contexts, a fit must be achieved between information-processing requirements and information-processing capacity. From this perspective, firms are viewed as open systems, and when they face increased uncertainty arising from market fluctuations, rapid technological change, or task complexity in the process of formulating and implementing strategic tasks, the challenges of information processing become more pronounced, exerting direct influence on decision-making and resource allocation [41,42]. If organizations are able to enhance their information-processing capacity through appropriate mechanisms to meet these requirements, they may gain competitive advantage [43]. Conversely, failure to identify, transmit, and interpret critical information in a timely manner may lead to resource misallocation and strategic failure [44]. Thus, firms need to ensure sufficient capabilities and resource commitments to match such requirements [43].

In recent years, OIPT has been widely applied in fields such as strategic management, innovation management, and supply chain management to explain how firms employ organizational design to cope with environmental dynamism and task complexity. For example, researchers have used the integrated OIPT framework to examine the drivers of digital transformation strategies, their relationship with supply chain performance [44,45], and their role in green supply chain innovation and sustainable performance [46]. Gupta et al. (2019) applied OIPT to explain how smart supply chains, combined with information system flexibility, can achieve greater supply chain agility [47].

OIPT emphasizes that firms can strengthen their ability to handle complex tasks and uncertainty by building vertical information systems and horizontal relational networks, thereby facilitating coordination of planning and information sharing among members [46,48]. Within this framework, the degree of fit between information-processing requirements and capacity reflects the extent to which the information collected and processed aligns with strategic implementation and resource capabilities [49]. This fit is considered a critical condition for improving organizational performance [50]. In the structure of OIPT, buffering and bridging strategies are regarded as two typical mechanisms for coping with environmental uncertainty [48]. The former reduces immediate information-processing requirements by creating internal resource redundancies to mitigate external shocks, while the latter enhances information-processing capacity by leveraging external relational networks to acquire additional resources and knowledge, thus achieving a balance between requirements and capacity [4,9]. This alignment is precisely what B–B congruence represents [8].

Moreover, OIPT also provides a theoretical foundation for understanding MSAI. Ambidextrous innovation requires firms to maintain a balance between exploitative and explorative innovation [20,21], and is closely associated with environmental dynamism [1]. Firms must rely on effective information processing to support strategic judgment and action [41,48]. In this regard, MSAI can be viewed as a concrete manifestation of information-processing requirements in the digital and system modeling context. Exploitative innovation depends on stable information-processing mechanisms to ensure efficiency and reliability, whereas explorative innovation requires flexible mechanisms to support breakthrough attempts.

Through simulation-based modeling environment-,such as digital twin systems and data-driven scenario experiments-firms can dynamically process information, visualize decision consequences, and test exploratory ideas before real-world implementation. This enables organizations to integrate information processing and decision modeling as part of their ambidextrous innovation strategy, improving both adaptability and reliability. Lu et al. (2023), for example, applied an information-processing framework to evaluate the role of digital transformation factors and various information-processing alternatives in shaping sustainable ambidextrous innovation and performance in complex environments [50]. Extending from this, simulation-driven information-processing systems can further enhance firms’ ability to achieve balance between exploration and exploitation through iterative learning and modeling feedback loops. Therefore, OIPT offers a useful theoretical lens for explaining how firms configure strategies and capabilities to achieve Modeling and Simulation Ambidextrous Innovation (MSAI) under conditions of complexity.

Because MSAI encompasses both incremental improvement and breakthrough exploration, it substantially increases the information-processing requirements faced by organizations. When firms are able to achieve a balance between requirements and capacity through the congruence of buffering and bridging, they are more likely to succeed in simulation-driven ambidextrous innovation [18]. Operational stability, financial flexibility, and knowledge management capabilities, as key outcome-oriented capacities of B–B congruence, serve as distinct supporting conditions for exploitative and explorative innovation [8,51,52]. In this study, these capabilities are further interpreted as the core enablers that transform modeling and simulation insights into dynamic innovation outcomes.

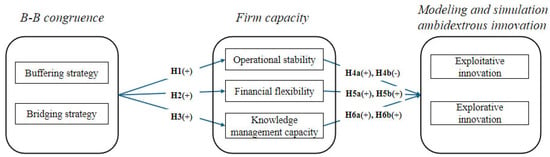

In sum, OIPT provides an appropriate and robust framework for this study by clarifying how organizations balance information-processing requirements and capabilities through B–B congruence to realize MSAI. The conceptual framework of the study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

2.3. Hypothesis Development

Buffering–Bridging Congruence and Organizational Capability

Operational stability can be regarded as a core information-processing dimension within the framework of OIPT, reflecting an organization’s ability to sustain daily operations and respond to external uncertainties. When environmental fluctuations increase information-processing demands, firms need to rely on stable processes, routines, and resource reserves to mitigate shocks and maintain continuity [53]. Buffering strategies, such as building redundant resources, including cash reserves, formalized procedures, and risk control mechanisms, may strengthen an organization’s capacity to withstand uncertainty and reduce the immediate information-processing burden arising from external volatility [2,6], thereby supporting operational stability [2]. In the human resource domain, maintaining a pool of multi-skilled employees is also considered an effective means of enhancing operational stability [54]. At the same time, bridging strategies—by fostering connections with the external environment to acquire information and resources—can improve an organization’s ability to sense and anticipate changes [25,55], indirectly ensuring the quality and stability of inputs [5,8] and enabling rapid recovery and flexible responses to disruptions [56]. The alignment of buffering and bridging allows firms to sustain basic operational stability under external shocks, while leveraging external networks to repair and adapt swiftly, thereby strengthening overall information-processing capacity and operational resilience. Based on this reasoning, the study proposes:

H1.

B–B congruence has a significant positive effect on operational stability.

From the perspective of OIPT, financial flexibility can be regarded as an organization’s information-processing capacity in resource allocation, namely, the ability to acquire and redeploy funds promptly in response to environmental demands. In highly dynamic market contexts, firms are required both to capture new opportunities continuously and to ensure the efficient use of scarce financial resources [18,57]. To respond effectively to environmental changes, organizations need mechanisms for information processing across both internal and external dimensions [19]. Buffering mechanisms, such as cash reserves, low leverage ratios, and risk-control measures, provide firms with a stable and sound capital structure, thereby reducing the impact of external shocks on financial conditions [2,51]. Such internal redundancy contributes to greater financial stability and autonomy. At the same time, bridging mechanisms—through the establishment of external financing channels, strategic partnerships, and trust-based relationships—help firms ease financing constraints, broaden resource access, and enhance the flexibility of financial arrangements [23,26]. In this way, they secure external sources of financial resilience. Accordingly, B–B congruence in the financial dimension reflects the combination of internal capital security and external financing flexibility, enabling firms to maintain both stability and adaptability under complex environments, thereby improving overall information-processing and resource-allocation efficiency. Hence, the study proposes:

H2.

B-B congruence positively impacts financial flexibility.

Knowledge management capability is regarded within the OIPT framework as a key process for enhancing information-processing capacity. It encompasses not only the creation, sharing, and retention of knowledge but also how firms integrate internal and external knowledge resources to meet the increasing information-processing demands of the environment [28]. Buffering mechanisms foster the storage and transfer of knowledge through stable internal processes and institutionalized arrangements, such as the establishment of knowledge repositories. As carriers of organizational knowledge, repositories [58] define the scope of activities firms can undertake and reflect their existing knowledge base and structures [59]. A well-developed knowledge repository incorporates both breadth (horizontal structure) and depth (vertical structure) [58], enabling firms to draw on existing knowledge while simultaneously acquiring new knowledge, thereby enhancing overall effectiveness [52]. Bridging mechanisms, in contrast, emphasize the acquisition of diverse knowledge through external collaborations, alliances, and open innovation, which expand firms’ knowledge boundaries [60]. The introduction of external knowledge can enrich both the breadth and depth of organizational knowledge, providing essential support for innovative activities [58]. Accordingly, consistent B–B strategies in the domain of knowledge management take the form of an organic combination of internal retention and external absorption, ensuring dynamic knowledge management in uncertain environments [61,62]. Accordingly, the study proposes:

H3.

B–B congruence has a significant positive effect on knowledge management capability.

Operational stability refers to the ability of organizations to maintain production, supply chain operations, and business continuity in the face of environmental uncertainty and external shocks. It is generally regarded as a core condition for firms to manage risks, safeguard performance, and create value [63]. In the fields of supply chain and innovation management, operational stability is not only a manifestation of risk control but also a prerequisite for subsequent strategy implementation and innovation activities [64]. From the perspective of OIPT, heightened environmental uncertainty increases the demand for information processing [40]. By maintaining a high level of operational stability, firms can mitigate volatility through institutionalized processes and resource redundancy, thereby enabling incremental improvements under relatively lower information-processing requirements. Prior studies suggest that stable processes and standardized mechanisms provide the institutional, procedural, and resource foundations necessary for exploitative innovation, supporting efficiency enhancement and incremental optimization [30,65].

However, stability is not always considered beneficial for innovation. Levinthal and March (1993) argue that excessive reliance on stable structures may lead to habitual dependency, weaken firms’ sensitivity to emerging opportunities, and hinder risk-taking decisions [34]. Highly programmed mechanisms may reduce tolerance for ambiguity and uncertainty, which are essential conditions for the development of exploratory innovation. Accordingly, while operational stability reduces volatility in information-processing demands, it may also limit firms’ absorptive flexibility toward new knowledge and opportunities, thereby exerting a negative influence on exploratory innovation.

Incorporating a modeling and simulation lens, operational stability can be interpreted as a structural condition shaping how firms design and evaluate digital representations of their operational systems. High stability facilitates accurate simulation models for exploitative improvement by reducing process variability, whereas excessive rigidity may constrain adaptive simulation for exploratory innovation, limiting the organization’s ability to test new designs or simulate emerging supply chain configurations under complex conditions. Hence, this study proposes:

H4a.

Operational stability positively impacts MS exploitative innovation.

H4b.

Operational stability negatively impacts MS exploratory innovation.

Financial flexibility emphasizes an organization’s adaptability and resilience in capital structure adjustment, financing choices, and resource allocation. It is considered a critical factor for coping with environmental uncertainty and supporting strategic investments such as innovation [66,67]. When environmental dynamism intensifies, firms face increasing information-processing requirements associated with investment decisions and risk exposure [1]. Financial flexibility enables firms to reallocate funds to meet diverse strategic needs in volatile environments, thereby enhancing information-processing capabilities. It helps organizations respond to unexpected risks and approach emerging opportunities with improved resource allocation [68].

Reliable financial safeguards can optimize internal processes and resources, improving operational efficiency. At the same time, the ability to flexibly allocate funds allows organizations to respond more rapidly to changes in external demand, thereby facilitating continuous incremental improvement of existing products or services [69], that is, exploitative innovation. Furthermore, since exploratory innovation often involves new technology development and market expansion, which are typically associated with high failure risks and significant resource consumption [20], financial flexibility provides both funding support and a buffer against risks, ensuring smoother progress in exploratory initiatives.

Viewed through the modeling and simulation framework, financial flexibility enhances firms’ capacity to simulate alternative investment strategies and dynamic resource configurations. It strengthens exploitative modeling by enabling precise scenario analyses for process optimization, while also fostering exploratory simulation that allows firms to test high-risk innovation pathways, assess digital transformation alternatives, and explore new supply chain architectures. Overall, the study proposes the following hypotheses:

H5a.

Financial flexibility positively impacts MS exploitative innovation.

H5b.

Financial flexibility positively impacts MS exploratory innovation.

Knowledge is widely regarded as one of the most strategically valuable organizational resources for innovation [1,62]. The essence of innovation lies in the recombination and application of knowledge [70]. The extent to which an organization searches for, creates, shares, retains, and applies knowledge reflects its level of knowledge management [71], which is considered a form of dynamic capability [72,73]. By integrating internal knowledge accumulation with external knowledge absorption, knowledge management serves as a fundamental basis for supporting innovation [1,61].

Knowledge management helps address firms’ increasing information-processing requirements. On the one hand, by codifying knowledge, facilitating knowledge sharing, and accumulating best practices, organizations can continually optimize existing processes and improve knowledge systems, thereby supporting exploitative innovation [28]. On the other hand, through open knowledge acquisition and external collaboration, firms can overcome knowledge constraints, enhance their ability to integrate and absorb knowledge across boundaries, expand knowledge reserves, and stimulate new ideas that foster exploratory innovation [52]. Effective knowledge management capabilities are therefore considered crucial for innovation [1,23]. Firms with stronger knowledge management capabilities are better positioned to achieve balance in ambidextrous innovation and to improve efficiency [1,62].

Extending this logic to modeling and simulation, knowledge management capability underpins firms’ ability to construct, refine, and validate digital models that represent operational dynamics and innovation mechanisms. Strong knowledge codification and transfer processes enhance exploitative modeling by standardizing simulation practices, while cross-boundary knowledge exchange promotes exploratory simulation that experiments with new technological configurations or system designs. Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H6a.

Knowledge management capability positively impacts MS exploitative innovation.

H6b.

Knowledge management capability positively impacts MS exploratory innovation.

3. Method

3.1. Sampling and Survey Design

To test the proposed research model, a survey was conducted between February and May 2025 among firms operating in China’s maritime logistics industry. This industry provides a suitable empirical setting for examining MSI because its operations heavily rely on simulation-based optimization and data-driven planning to improve scheduling efficiency, manage operational risks, and support strategic decisions. In recent years, the increasing digitalization of maritime operations has encouraged firms to apply modeling and simulation systems more systematically, which makes it possible to distinguish between exploitative and explorative forms of MSI in practice.

The survey was carried out in collaboration with a professional research company that specializes in maritime and logistics industries. The company maintains a large database covering major ports and shipping firms across China and has extensive experience in collecting high-quality data from managerial respondents. The sample included four categories of firms-shipping companies, port operators, freight forwarders, and maritime technology service providers. These firms together form the core of China’s maritime logistics network and represent different levels of MSI practice. Shipping companies and port operators usually apply simulation models to optimize scheduling and resource allocation, freight forwarders employ modeling tools for route planning and efficiency prediction, while maritime technology providers develop system platforms and digital twin applications that drive innovation at the industry level. Including all four types of firms therefore offers a more complete picture of MSI across operational, process, and technological layers.

Before launching the main survey, a pretest was conducted to evaluate the clarity and logical consistency of the questionnaire. Twenty senior managers from shipping firms participated in the pretest, and thirteen of them joined an online review panel to discuss the questionnaire and provide feedback. Based on their suggestions, the research team refined item wording and sequencing to ensure clarity and alignment with industry terminology. The final questionnaire consisted of three sections. The first section described the purpose of the study and assured respondents that their information would remain confidential and be used only for academic research. The second section measured the key latent constructs of this study, including strategic orientations, firm capabilities, and MSI dimensions. The third section collected basic firm information and control variables such as firm size, founding year, business type, region, and level of digitalization. All measurement items used a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

3.2. Data Collection and Sample Profile

Several procedural remedies were applied to minimize common method bias, such as randomizing question order, separating conceptually related constructs, varying item wording, and including an attention check item. The research company also made follow-up phone calls and collaborated with industry partners to encourage participation and ensure balanced representation across firm types and sizes. The sampling was carried out in collaboration with a specialized maritime and logistics research agency, using stratified random sampling based on firm type and firm size from their enterprise database covering major port cities across China. A total of 300 valid responses were received. During data cleaning, 11 questionnaires were excluded. Among them, six respondents failed the attention check item, while another five were completed in an unusually short time compared to the average duration observed during the pre-test phase. To ensure that the sample is sufficiently representative and provides adequate statistical power, we followed common recommendations in the literature suggesting that the sample size should be at least five times the number of free parameters in the model, including error terms [74]. Based on this guideline, the number of valid responses collected in this study exceeds the estimated threshold, supporting the robustness of the subsequent analyses. After these adjustments, the final dataset provided a robust and representative sample of China’s maritime logistics industry, suitable for subsequent structural equation modeling analyses. Detailed information on respondent demographics is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Respondent demographics.

3.3. Measurement Items Design

All constructs were measured using multi-item scales adapted from prior studies and refined to fit the MSI context in maritime logistics (Table 2). BUF was adopted from Sher and Lee (2004) [75] and Tseng and Lee (2014) [76] to assess the firm’s efforts to strengthen supply chain buffers and enhance resilience when facing disruptions. This construct reflects practices such as diversifying suppliers and developing redundancy to reduce operational vulnerability; a representative item is “We source from geographically diverse suppliers to reduce the risk of disruptions in any single region”. BRI was adapted from Bode et al. (2011) [5] and Olabode et al. (2025) [77] to measure how the firm builds and maintains collaborative ties with external partners to support coordinated responses to change, illustrated by “We maintain strong and ongoing cooperative relationships with our supply chain partners”. OPS was drawn from Brandon-Jones et al. (2014) [78] and Rojo et al. (2018) [79] to capture the firm’s ability to maintain stable operations and recover rapidly when interruptions occur; for example, “Our organization can quickly restore normal operations when faced with interruptions”.

Table 2.

Measurement items.

For FIN, a widely agreed-upon scale in MSI or maritime logistics research has not yet been established. Therefore, the items were cautiously adapted from prior work on financial resource flexibility and capital reallocation under uncertainty [80,81], and were refined through pilot feedback to ensure that they reflect responsiveness to operational contingencies rather than overall financial performance. A representative item is “We are able to adjust our capital allocation quickly in response to market changes”. KMC was adapted from Sher and Lee (2004) [75] and Tseng and Lee (2014) [76] to capture how knowledge is shared, integrated, and applied across organizational units, reflected in “Employees clearly understand one another’s responsibilities and areas of expertise”. Finally, EXI and ERI were adopted from Enkel et al. (2017) [29] to measure ambidextrous innovation behavior, with EXI indicating incremental refinement and ERI indicating exploratory search. All items were rated on a seven-point Likert scale from “1 = strongly disagree” to “7 = strongly agree”.

3.4. Bias Tests

Because the data were collected using a single survey instrument, we assessed whether common method bias or systematic response patterns might pose a threat to the validity of the results. We first conducted Harman’s single-factor test. An exploratory factor analysis showed that the first factor accounted for 23.7% of the total variance, which is below the commonly used 50% threshold [82]. While this approach provides only an initial indication, it suggests that common method bias is unlikely to be dominant.

To provide a more robust assessment, we further employed a marker variable technique. As a theoretically unrelated construct, we included respondents’ attitudes toward sustainable tourism, which bears no conceptual linkage to MSI practices or innovation behavior. The inclusion of this marker variable did not materially change the significance or magnitude of the structural relationships, offering additional support that common method bias is not a substantial concern.

In addition, we examined potential non-response bias by comparing early and late respondents following Armstrong and Overton (1977) [83]. Independent-sample t-tests revealed no statistically significant differences across demographic characteristics or focal variables (p > 0.10), suggesting that non-response bias is unlikely to affect the results. We also assessed discriminant validity using the Heterotrait–Monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT) criterion, and all values fell below 0.85, indicating that the constructs are empirically distinct. Finally, variance inflation factor (VIF) values ranged from 1.21 to 2.48, well below the recommended threshold of 5, which suggests that multicollinearity is not a concern. Taken together, these diagnostic checks indicate that the data are not substantially affected by common method bias or non-response bias, and that the constructs exhibit adequate discriminant validity and independence for structural model estimation.

4. Empirical Analysis Results

4.1. Construct Reliability and Validity

Before formal analysis, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess the measurement quality of all latent constructs (Table 3 and Table 4). The overall model demonstrated a good fit to the data, with CFI = 0.979, TLI = 0.975, RMSEA = 0.037, Chi-square = 385.79, DF = 278, and SRMR = 0.033, which fall within the commonly accepted thresholds [84]. Moreover, the results in Table 3 indicate that all standardized factor loadings exceed the recommended level of 0.70, with values ranging from 0.724 to 0.923, suggesting that the items provide a reasonable representation of their intended constructs. The average variance extracted (AVE) values fall between 0.551 and 0.825, surpassing the 0.50 benchmark and thereby supporting convergent validity, consistent with the guidelines proposed by Fornell and Larcker (1981) [85]. In terms of internal consistency, the composite reliability (CR) values range from 0.786 to 0.950, all exceeding the commonly accepted threshold of 0.70, indicating satisfactory reliability and aligning with the recommendations of Hair et al. (2009) [82].

Table 3.

Reliability and validity test results.

Table 4.

Correlations among constructs.

We further examined discriminant validity by comparing the square root of each construct’s AVE with the inter-construct correlations. As shown in Table 4, the square roots of AVE (reported on the diagonal) are consistently higher than the corresponding correlations. These results collectively suggest that the measurement model demonstrates acceptable reliability and validity, and is suitable for subsequent structural analysis.

4.2. Hypothesis Testing Results

4.2.1. Polynomial Regression Model and Response Surface Analyses

To examine whether the congruence between BUF and BRI contributes to firm capability development (i.e., OPS, FIN, and KMC), we estimated a polynomial regression model with response surface analysis [84,86]. This approach is preferred because it allows BUF and BRI to retain their individual effects while also capturing their combined and nonlinear influences [87]. For example, while the difference-score approach would treat the cases of BUF = 4, BRI = 2 and BUF = 6, BRI = 4 as equivalent, the latter reflects a higher overall strategic engagement, which may translate into stronger resource deployment. The polynomial method is therefore more suitable for identifying the effect of BUF–BRI congruence. Thus, we constructed the following polynomial regression model:

where Z refers to the firm’s capacity in terms of OPS, FIN, and KMC. Controls is the vector of control variables (firm age, firm size, and ROA).

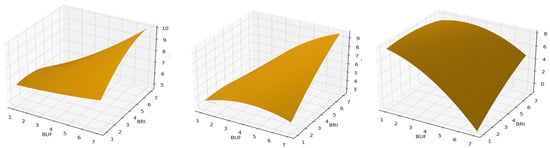

We report the analysis results in Table 5. The response surface indicates a significant downward curvature along the incongruence line (BUF = −BRI), where BUF and BRI diverge. The coefficient was negative and statistically significant (b = −0.3321, p = 0.003, 95% CI = [−0.551, −0.113]). This downward curvature suggests that misalignment between BUF and BRI reduces OPS, whereas greater congruence—particularly at higher levels—corresponds to enhanced operational stability. Thus, H1 is supported. A similar pattern appears for FIN. The curvature along the incongruence line was negative and significant (b = −0.4159, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [−0.578, −0.254]). This suggests that firms face reduced financial adaptability when BUF and BRI are imbalanced. In contrast, congruence enables more flexible allocation and mobilization of financial resources. Therefore, H2 is supported. Furthermore, the effect also holds for KMC, with a negative and significant curvature (b = −0.2004, p = 0.037, 95% CI = [−0.389, −0.012]). When BUF and BRI diverge, firms appear less effective in acquiring, sharing, and integrating knowledge. Congruence between the two strategies, however, is associated with stronger knowledge management capacity. Thus, H3 is supported.

Table 5.

Polynomial regression results.

To further confirm these results, we further conducted a ridge test using 5000 bootstrap resamples to examine whether the peak of the response surface lies along the congruence line [88,89]. For all three outcomes—OPS, FIN, and KMC—the 95% confidence interval for the intercept included zero and the interval for the slope included one, indicating no significant deviation from the congruence line. This confirms that higher levels of these capabilities are associated with BUF–BRI congruence, rather than with imbalanced configurations.

We plot the response surfaces in Figure 2 to illustrate how BUF and BRI jointly shape OPS, FIN, and KMC. The figure shows that the predicted levels of OPS, FIN, and KMC are highest when BUF and BRI move in the same direction and reinforce each other. In contrast, when BUF and BRI diverge in magnitude or direction, the predicted performance consistently declines across the three outcomes. Taken together, the visual patterns in Figure highlight the importance of the alignment between BUF and BRI for achieving favorable operational, financial, and knowledge results.

Figure 2.

Response surface of the B-B strategy.

4.2.2. Structural Equation Modeling Analysis

We examined H4–H6 using a structural equation modeling (SEM) approach, and the results are presented in Table 6. The path estimates show that the effect of OPS on EXI was statistically non-significant (β = 0.016, p > 0.05), indicating that greater OPS does not necessarily translate into a stronger focus on exploitative innovation. Thus, H4a is not supported. Similarly, although the effect of OPS on ERI reached significance (β = 0.119, p < 0.05), the direction of the effect was positive rather than the hypothesized negative. Therefore, H4b is rejected.

Table 6.

Structural equation modeling results.

For FIN, the results are mixed. The effect of FIN on EXI was positive and significant (β = 0.132, p < 0.05), supporting H5a. However, the effect of FIN on ERI was not significant (β = 0.074, p > 0.05), suggesting that FIN alone does not necessarily encourage ERI. Thus, H5b is not supported. Finally, the effects of KMC were consistently positive and significant across both types of innovation. The results show that KMC positively influenced EXI (β = 0.198, p < 0.01) as well as ERI (β = 0.179, p < 0.01), supporting both H6a and H6b.

Knowledge management capability shows a consistently positive effect on both exploitative and explorative innovation, which aligns with the findings of Zhou and Li (2012) [58] and Jia et al. (2022) [62], underscoring the foundational role of knowledge integration in innovation processes. Financial flexibility significantly influences only exploitative innovation, echoing Marchica and Mura (2010) [51], who argue that financial slack tends to support incremental investments. The absence of an effect on explorative innovation suggests that financial resources alone may be insufficient for high-risk, uncertain simulation experimentation, which may require stronger organizational learning cultures or leadership support [32].

Finally, operational stability exhibits a positive association with explorative innovation, which appears to diverge from the concerns raised by Levinthal and March (1993) [34]. A possible explanation is that, in simulation-based environments, stable processes and structured data systems provide a repeatable and controllable context for experimentation, reducing actual risk exposure and supporting “disciplined experimentation” as highlighted in recent digital-transformation research [30].

5. Discussion

Drawing on organizational information-processing theory (OIPT), this study explores how firms can design consistent buffering and bridging strategies to reduce information-processing demands while simultaneously strengthening core capabilities such as operational stability, financial flexibility, and knowledge management. In doing so, firms are better positioned to address the complex information-processing challenges associated with modeling and simulation ambidextrous innovation (MSAI). The findings offer several theoretical and practical implications.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

First, this study examines and extends the applicability of OIPT in the contexts of supply chain management and innovation management. OIPT not only provides insights into how firms develop and configure adaptive capabilities in dynamic environments but also reveals how they strategically balance information-processing demands with capacity building to achieve sustained competitive advantage. This resonates with and expands upon the conclusions of prior research [44,46], thereby enriching the theoretical boundaries of OIPT’s application in complex, simulation-driven environments. Specifically, it demonstrates that modeling and simulation contexts heighten the need for alignment between organizational design and information-processing structures, validating OIPT’s relevance to digital and data-intensive decision-making.

Second, this study emphasizes the critical role of buffering–bridging congruence (B–B congruence) in capability development and in achieving a dynamic balance between information-processing demands and problem-solving capacity. Buffering strategies help accumulate redundant resources through internal allocation, while bridging strategies enhance adaptability through external linkages. The alignment of the two allows organizations to effectively integrate physical, digital, and informational resources, which is particularly crucial for simulation-based modeling activities that require iterative data exchange and coordination. The study thus contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of strategic congruence in simulation-enabled logistics systems, addressing existing research gaps on how the synergy between buffering and bridging shapes innovation outcomes under complex and uncertain conditions.

Organizational ambidexterity theory suggests that firms adapt to new demands during periods of change by adjusting managerial, environmental, and organizational drivers [28]. The empirical results reveal differentiated mechanisms of the three capabilities in shaping MSAI. Contrary to our initial hypothesis and the analytical framework outlined by Zhou et al. (2021) [90], operational stability does not significantly enhance exploitative simulation innovation, and its influence on exploratory simulation innovation is positive but contrary to expectations. This suggests that, in simulation-oriented contexts, stability may no longer act as a constraint but instead provide a reliable foundation for experimental modeling and digital scenario testing. Firms with standardized processes and data infrastructures are better able to support simulation-based exploration, even under stable conditions.

In contrast, financial flexibility positively affects exploitative modeling and simulation innovation but shows no significant effect on exploratory innovation. This implies that while flexible financial structures facilitate resource deployment for incremental simulation refinement, they may not directly stimulate risk-taking or high-uncertainty modeling efforts.

Finally, knowledge management capability exerts a consistently positive influence on both exploitative and exploratory simulation innovation. This resonates with the theoretical perspective of maritime knowledge clusters proposed by Zhou et al. (2021) [91], which highlights that localized knowledge networks serve as a foundational source of global competitiveness. Knowledge integration and cross-boundary sharing enhance firms’ ability to design, test, and refine simulation models, enabling them to navigate between incremental optimization and radical experimentation. Taken together, these findings reveal that a balanced configuration of organizational capabilities—rather than their independent strength—determines firms’ success in MSAI, offering a refined perspective on capability–strategy alignment within OIPT.

5.2. Managerial Implications

For managers on the front lines, particularly in logistics-intensive sectors such as maritime and port operations, this study provides three practical insights for advancing MSAI and enhancing system resilience and sustainability.

First, managers should prioritize strategic congruence over isolated buffering or bridging actions. Instead of treating internal resource buffers and external network bridges as independent mechanisms, they should be designed synergistically. By embedding simulation modeling into strategic planning, firms can develop a “resilience playbook”—a digital decision framework that tests different B–B configurations under simulated disruptions (e.g., supplier bankruptcy, blocked shipping routes). This transforms abstract risk management into an actionable system-level strategy for sustaining operations and innovation readiness [92,93]. Managers may use existing simulation platforms (e.g., AnyLogic, FlexSim, or proprietary digital-twin systems) to evaluate how different levels of buffering (e.g., inventory or cash reserves) and bridging (e.g., number of partners, depth of information sharing) perform under simulated disruptions such as port congestion or fuel-price surges. This helps assess the coordination requirements between operational stability and financial flexibility and identify robust strategic responses.

Second, while operational stability provides the necessary foundation for simulation-based control and efficient operations, our findings reveal that excessive stabilization may hinder exploratory innovation. Managers should therefore pursue adaptive stability-maintaining reliable processes while using simulation environments to safely explore alternative strategies and innovations. To balance these dual demands, firms can adopt structural ambidexterity, establishing distinct units for stable operations and simulation-driven innovation projects. This organizational separation enables firms to preserve short-term efficiency without sacrificing long-term adaptability. Another practical approach involves establishing cross-functional “simulation innovation teams” that are authorized to access corporate simulation resources for modeling, testing, and learning from exploratory scenarios, while translating feasible insights back into operational units. Managers should also remain aware of potential cooperation pitfalls in maritime logistics, such as limited trust, misaligned goals, and challenges in cost, benefit evaluation [94].

Third, financial flexibility and knowledge management capability emerged as the most powerful enablers of MSAI. Financial flexibility allows rapid reallocation of resources to support both incremental improvements and digital experimentation, while knowledge management capability integrates internal learning with external collaboration to enhance system-wide adaptability. Managers should therefore strengthen data-sharing infrastructures and simulation capabilities to better convert organizational knowledge into actionable innovation pathways. Furthermore, firms may consider investments that integrate knowledge-management platforms with financial-agility tools. For instance, creating a simulation-linked knowledge repository to encode parameters, results, and insights from each experiment can support organization-wide learning. Collaboration with financial institutions to develop dynamic credit solutions informed by simulation data may also strengthen financial flexibility and allow timely responses to anticipated risks and opportunities.

From a policy perspective, governments should support systemic B–B congruence across supply chains by incentivizing collaborative simulation-based R&D programs rather than isolated funding. In addition, improving financial infrastructure, such as accessible capital markets and flexible innovation financing, can enhance firms’ capacity for both short-term resilience and long-term technological advancement. Finally, establishing shared digital infrastructures (e.g., national logistics data and simulation platforms) will enable industry-wide modeling collaboration, empowering the entire ecosystem to co-develop solutions and strengthen competitiveness in an era of uncertainty.

6. Conclusions

Based on OIPT, this study systematically examines how firms operating in highly dynamic and uncertain environments can foster capability building and ultimately enhance modeling and simulation ambidextrous innovation performance through the congruent design of buffering and bridging strategies. The findings indicate that aligned buffering–bridging strategies, as a form of horizontal fit within information-processing mechanisms, can facilitate the development of core capabilities such as operational stability, financial flexibility, and knowledge management capability. The formation and joint functioning of these capabilities may enable firms to achieve a dynamic balance between exploitative and exploratory innovation, thereby improving innovation performance. By revealing the structural pathways involved, this study not only provides new perspectives for theoretical research but also offers insights into how firms may strategically configure efficiency and adaptability to pursue sustainable competitive advantage.

Inevitably, this study has certain limitations. First, the research focuses on firms in China and collects data from a specific industry, which restricts the generalizability of the findings. Future studies are encouraged to test the conceptual framework in other emerging economies and industries to broaden its applicability. Second, the study relies on survey data to examine structural pathways, which presents temporal constraints and does not capture the dynamic evolution of relationships among the variables of interest. Future research could employ longitudinal datasets from different industries or alternative methods to provide deeper insights into the dynamic development of the model’s factors. Moreover, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits our ability to capture the dynamic causal evolution between B-B congruence and MSAI. Although multiple procedural and statistical remedies were employed to mitigate common-method bias, constructs such as financial flexibility may still be affected by subjective assessment and self-reporting. Future research could incorporate longitudinal tracking or multi-source data to enable more robust and comprehensive validation. Finally, additional variables may mediate or moderate the relationships examined in this study. Future research may enrich the boundary conditions, for example, by considering ownership structures or adopting different theoretical perspectives to refine the model.

Author Contributions

X.W. was responsible for conceptualization, writing the original draft, as well as reviewing and editing the draft. J.S. was responsible for conceptualization, writing the original draft, supervision, formal analysis, and validation. M.F. was responsible for conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, writing the original draft, and validation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research Center for Enterprise Innovation and Development (REID), Anhui Institute of Information Technology, grant number 23kjcxpt003; by the High-Level Talent Research Initiation Project of Anhui Institute of Information Technology. The present Research has been conducted by the Research Grant of Kwangwoon University in 2024.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Soto-Acosta, P.; Popa, S.; Martinez-Conesa, I. Information Technology, Knowledge Management and Environmental Dynamism as Drivers of Innovation Ambidexterity: A Study in SMEs. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 22, 824–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.; Sharma, R.R.K.; Kumar, S.; Dubey, R. Bridging and Buffering: Strategies for Mitigating Supply Risk and Improving Supply Chain Performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 180, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Liu, J.; Scutella, J. The Impact of Supply Chain Disruptions on Stockholder Wealth in India. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2015, 45, 938–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C. Strategic Responses to Institutional Processes. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 145–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, C.; Wagner, S.M.; Petersen, K.J.; Ellram, L.M. Understanding Responses to Supply Chain Disruptions: Insights from Information Processing and Resource Dependence Perspectives. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 833–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj Sinha, P.; Whitman, L.E.; Malzahn, D. Methodology to Mitigate Supplier Risk in an Aerospace Supply Chain. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2004, 9, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, P.; Glick, W.H.; Huber, G.P. Organizational Actions in Response to Threats and Opportunities. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 937–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Wu, Y.; Chen, X.; Ding, R.; Liu, H. How Does Buffering–Bridging Alignment Influence Supply Chain Resilience? A Polynomial Regression Analysis. Inf. Manag. 2025, 63, 104241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premkumar, G.; Ramamurthy, K.; Saunders, C.S. Information Processing View of Organizations: An Exploratory Examination of Fit in the Context of Interorganizational Relationships. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2005, 22, 257–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, S.M.; Bode, C. An Empirical Examination of Supply Chain Performance along Several Dimensions of Risk. J. Bus. Logist. 2008, 29, 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laari, S.; Lorentz, H.; Jonsson, P.; Lindau, R. Procurement’s Role in Resolving Demand–Supply Imbalances: An Information Processing Theory Perspective. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2023, 43, 68–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simchi-Levi, D.; Wang, H.; Wei, Y. Increasing Supply Chain Robustness through Process Flexibility and Inventory. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2018, 27, 1476–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marley, K.A.; Ward, P.T.; Hill, J.A. Mitigating Supply Chain Disruptions—A Normal Accident Perspective. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2014, 19, 142–152. [Google Scholar]

- Manhart, P.; Summers, J.K.; Blackhurst, J. A Meta-Analytic Review of Supply Chain Risk Management: Assessing Buffering and Bridging Strategies and Firm Performance. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2020, 56, 66–87. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Balushi, Z.; Durugbo, C.M. Management Strategies for Supply Risk Dependencies: Empirical Evidence from the Gulf Region. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2020, 50, 457–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spieske, A.; Gebhardt, M.; Kopyto, M.; Birkel, H. Improving Resilience of the Healthcare Supply Chain in a Pandemic: Evidence from Europe during the COVID-19 Crisis. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2022, 28, 100748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.H.; Chou, C.Y.; Chang, H.L.; Hsu, C. Building Digital Resilience against Crises: The Case of Taiwan’s COVID-19 Pandemic Management. Inf. Syst. J. 2024, 34, 39–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, J.J.; Van den Bosch, F.A.; Volberda, H.W. Exploratory Innovation, Exploitative Innovation, and Ambidexterity: The Impact of Environmental and Organizational Antecedents. Schmalenbach Bus. Rev. 2005, 57, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, L.V.; Bucic, T.; Sinha, A.; Lu, V.N. Effective Sense-and-Respond Strategies: Mediating Roles of Exploratory and Exploitative Innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 94, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G. Exploration and Exploitation in Organizational Learning. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.A.; Tushman, M.L. The Ambidextrous Organization. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2004, 82, 74–83. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, C.B.; Birkinshaw, J. The Antecedents, Consequences, and Mediating Role of Organizational Ambidexterity. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Lieshout, J.W.; Van Der Velden, J.M.; Blomme, R.J.; Peters, P. The Interrelatedness of Organizational Ambidexterity, Dynamic Capabilities and Open Innovation: A Conceptual Model towards a Competitive Advantage. Eur. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 26, 39–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2025–2030 China Port Construction Industry Development Strategy and Market In-Depth Research Analysis Report; China Industry Research Network: Beijing, China, 2025; Available online: https://www.chinairn.com/hyzx/20251201/174909525.shtml (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Boumgarden, P.; Nickerson, J.; Zenger, T.R. Sailing into the Wind: Exploring the Relationships among Ambidexterity, Vacillation, and Organizational Performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 587–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirst, G.; Van Knippenberg, D.; Zhou, Q.; Zhu, C.J.; Tsai, P.C.F. Exploitation and Exploration Climates’ Influence on Performance and Creativity: Diminishing Returns as Function of Self-Efficacy. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 870–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enkel, E.; Heil, S. Preparing for Distant Collaboration: Antecedents to Potential Absorptive Capacity in Cross-Industry Innovation. Technovation 2014, 34, 242–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srisathan, W.A.; Ketkaew, C.; Naruetharadhol, P. Assessing the Effectiveness of Open Innovation Implementation Strategies in the Promotion of Ambidextrous Innovation in Thai Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enkel, E.; Heil, S.; Hengstler, M.; Wirth, H. Exploratory and Exploitative Innovation: To What Extent Do the Dimensions of Individual Level Absorptive Capacity Contribute? Technovation 2017, 60, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, M.J.; Tushman, M.L. Exploitation, Exploration, and Process Management: The Productivity Dilemma Revisited. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 238–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.R.; Kannan-Narasimhan, R.P. Formal Integration Archetypes in Ambidextrous Organizations. RD Manag. 2015, 45, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.A., III; Tushman, M.L. Organizational Ambidexterity in Action: How Managers Explore and Exploit. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2011, 53, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felício, J.A.; Caldeirinha, V.; Dutra, A. Ambidextrous Capacity in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinthal, D.A.; March, J.G. The Myopia of Learning. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 14, S95–S112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriopoulos, C.; Lewis, M.W. Exploitation–Exploration Tensions and Organizational Ambidexterity: Managing Paradoxes of Innovation. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 696–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junni, P.; Sarala, R.M.; Taras, V.A.S.; Tarba, S.Y. Organizational Ambidexterity and Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 27, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Li, Y.; Liu, W.; Hao, R.Y. Navigating the Innovation Maze: The Role of Supervisor Developmental Feedback in Fostering Ambidextrous Learning and Ambidextrous Innovation. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 32079–32101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Li, C.; Wang, S.; Li, Q. Digital Transformation, Risk-Taking, and Innovation: Evidence from Data on Listed Enterprises in China. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, M.; Gong, C.; Moon, G.H.; Ge, X. Digital Economy, Dual Innovation Capability and Enterprise Labor Productivity. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2025, 101, 104005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbraith, J. Designing Complex Organizations; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, M.; Bryde, D.J.; Stavropoulou, F.; Dubey, R.; Kumari, S.; Foropon, C. Modelling Supply Chain Visibility, Digital Technologies, Environmental Dynamism and Healthcare Supply Chain Resilience: An Organisation Information Processing Theory Perspective. Transp. Res. Part E 2024, 188, 103613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Q.; Lai, P.L.; Su, M.; Xing, J.; Fang, M. Talk is Cheap; Show Me the Code: Managing the Sustainable Performance of Shipping Firms through Big Data Analytics. Marit. Policy Manag. 2025, 52, 1162–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Q.; Cai, L.; Wang, X.; Fang, M. Digital Transformation as the Fuel for Sailing toward Sustainable Success: The Roles of Coordination Mechanisms and Social Norms. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2024, 37, 1069–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Liu, F.; Xiao, S.; Park, K. Hedging the Bet on Digital Transformation in Strategic Supply Chain Management: A Theoretical Integration and an Empirical Test. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2023, 53, 512–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Liu, F.; Xiao, S.; Park, K.; Gao, Y. Navigating Ethical Dilemmas in Supply Chain Finance: The Interplay Between Digitalization and Cultural Congruence. J. Bus. Logist. 2025, 46, e70027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Samadhiya, A.; Kumar, A.; Luthra, S.; Kumar, V.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Upadhyay, A. The Interplay Effects of Digital Technologies, Green Integration, and Green Innovation on Food Supply Chain Sustainable Performance: An Organizational Information Processing Theory Perspective. Technol. Soc. 2024, 77, 102585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Drave, V.A.; Bag, S.; Luo, Z. Leveraging Smart Supply Chain and Information System Agility for Supply Chain Flexibility. Inf. Syst. Front. 2019, 21, 547–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, R.; Swink, M. An Investigation of Visibility and Flexibility as Complements to Supply Chain Analytics: An Organizational Information Processing Theory Perspective. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2018, 27, 1849–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behl, A.; Gaur, J.; Pereira, V.; Yadav, R.; Laker, B. Role of Big Data Analytics Capabilities to Improve Sustainable Competitive Advantage of MSME Service Firms during COVID-19—A Multi-Theoretical Approach. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 148, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.T.; Li, X.; Yuen, K.F. Digital Transformation as an Enabler of Sustainability Innovation and Performance–Information Processing and Innovation Ambidexterity Perspectives. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 196, 122860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchica, M.T.; Mura, R. Financial Flexibility, Investment Ability, and Firm Value: Evidence from Firms with Spare Debt Capacity. Financ. Manag. 2010, 39, 1339–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chin, T.; Lin, J.H. Openness and Firm Innovation Performance: The Moderating Effect of Ambidextrous Knowledge Search Strategy. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 24, 301–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, S.; Sodhi, M.S. Managing Risk to Avoid Supply-Chain Breakdown. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2004, 46, 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, P.M.; Snell, S.A. Toward a Unifying Framework for Exploring Fit and Flexibility in Strategic Human Resource Management. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 756–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzzi, B. Social Structure and Competition in Interfirm Networks: The Paradox of Embeddedness. In The Sociology of Economic Life; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 213–241. [Google Scholar]

- Sheffi, Y.; Rice, J.B., Jr. A Supply Chain View of the Resilient Enterprise. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Aissa Fantazy, K.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, U. An Empirical Study of the Relationships among Strategy, Flexibility, and Performance in the Supply Chain Context. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2009, 14, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.Z.; Li, C.B. How Knowledge Affects Radical Innovation: Knowledge Base, Market Knowledge Acquisition, and Internal Knowledge Sharing. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 1090–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, W.W.; Liu, G. How Information Technology Assimilation Promotes Exploratory and Exploitative Innovation in the Small-and Medium-Sized Firm Context: The Role of Contextual Ambidexterity and Knowledge Base. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2019, 36, 442–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.W. Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, W.M.; Levinthal, D.A. Absorptive Capacity: A New Perspective on Learning and Innovation. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, R.; Hu, W.; Li, S. Ambidextrous Leadership and Organizational Innovation: The Importance of Knowledge Search and Strategic Flexibility. J. Knowl. Manag. 2022, 26, 781–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheffi, Y. The Resilient Enterprise: Overcoming Vulnerability for Competitive Advantage; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W.; Chavez, R.; Jacobs, M.A.; Wong, C.Y. Openness to Technological Innovation, Supply Chain Resilience, and Operational Performance: Exploring the Role of Information Processing Capabilities. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2022, 71, 1258–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, M.J.; Tushman, M.L. Reflections on the 2013 Decade Award—“Exploitation, Exploration, and Process Management: The Productivity Dilemma Revisited” Ten Years Later. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2015, 40, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, D.J. Financial Flexibility and Corporate Liquidity. J. Corp. Financ. 2011, 17, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, J.P. The Capital Structure Implications of Pursuing a Strategy of Innovation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 415–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wei, J. Research on the Effect of Enterprise Financial Flexibility on Sustainable Innovation. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Liu, S.; Gao, L. Digital Finance, Financial Flexibility and Corporate Green Innovation. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 70, 106313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.M. Toward a Knowledge-Based Theory of the Firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, S109–S122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Chuang, S.H.; To, P.L. How Knowledge Management Mediates the Relationship Between Environment and Organizational Structure. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 728–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, U.; Lichtenthaler, E. A Capability-Based Framework for Open Innovation: Complementing Absorptive Capacity. J. Manag. Stud. 2009, 46, 1315–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterby-Smith, M.; Prieto, I.M. Dynamic Capabilities and Knowledge Management: An Integrative Role for Learning? Br. J. Manag. 2008, 19, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golob, T.F. Structural Equation Modeling for Travel Behavior Research. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2003, 37, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sher, P.J.; Lee, V.C. Information Technology as a Facilitator for Enhancing Dynamic Capabilities Through Knowledge Management. Inf. Manag. 2004, 41, 933–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, S.-M.; Lee, P.-S. The Effect of Knowledge Management Capability and Dynamic Capability on Organizational Performance. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2014, 27, 158–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olabode, O.E.; Nalmpanti, A.D.; Essuman, D.; Leonidou, C.N.; Hultman, M.; Boso, N. How and When Bridging and Buffering Strategies Drive Financial Performance: Evidence from Companies Using Key Account Management. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2025, 131, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandon-Jones, E.; Squire, B.; Autry, C.W.; Petersen, K.J. A Contingent Resource-Based Perspective of Supply Chain Resilience and Robustness. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2014, 50, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo, A.; Stevenson, M.; Lloréns Montes, F.J.; Perez-Arostegui, M.N. Supply Chain Flexibility in Dynamic Environments: The Enabling Role of Operational Absorptive Capacity and Organisational Learning. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2018, 38, 636–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Lin, J.; Luo, X. Enhancing Organizational Resilience Through Big Data Analytics Capability: The Mediating Role of Strategic Flexibility. Inf. Technol. People, 2025; ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, L.; Machado, J. Employees’ Skills, Manufacturing Flexibility and Performance: A Structural Equation Modelling Applied to the Automotive Industry. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 53, 4087–4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, J.S.; Overton, T.S. Estimating Nonresponse Bias in Mail Surveys. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Cable, D.M. The Value of Value Congruence. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 654–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Yuen, K.F.; Xie, D.; Wang, X.; Pang, Q. Are We on the Same Page? Effects of Sustainability Orientation (In)Congruence on Sustainable Shipping Performance. Oper. Manag. Res. 2025, 19, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Cai, L.; Park, K.; Su, M. Trust (In)congruence, Open Innovation, and Circular Economy Performance: Polynomial Regression and Response Surface Analyses. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 358, 120930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Lai, P.-L.; Wang, X. The Value of Congruence in Social Exchanges: A Dyadic Trust Perspective on Servitization. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2024, 123, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Q.; Wang, M.; Yao, J.; Fang, M. Employees’ Perceived Respect and Performance in Logistics 4.0: A Dyadic Perspective of the Congruence Between Employee Voice and Supervisor Listening. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2025; ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, X.; Yuen, K.F. Sustainability Disclosure for Container Shipping: A Text-Mining Approach. Transp. Policy 2021, 110, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yuen, K.F.; Tan, B.; Thai, V.V. Maritime Knowledge Clusters: A Conceptual Model and Empirical Evidence. Mar. Policy 2021, 123, 104299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Munim, Z.H. A Systematic Review on Human-centred Maritime Operations Analytics Involving Psychophysiological Data. Marit. Policy Manag. 2025, 52, 1208–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yuen, K.F. Prepare for the Sustainability Era: A Quantitative Risk Analysis Model for Container Shipping Sustainability-related Risks. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 475, 143661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, K.F.; Thai, V. Barriers to Supply Chain Integration in the Maritime Logistics Industry. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2017, 19, 551–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).