Abstract

Rapid progress in sustainable and intelligent transportation has intensified interest in smart airport initiatives, driven by the need to support environmentally responsible and technology-enabled aviation development. As complex sociotechnical subsystems of smart aviation, smart airports integrate advanced digital, operational, and organizational technologies to enhance efficiency, resilience, and passenger experience. With increasing emphasis on such transformations, multiple strategic development plans have emerged, each with distinct priorities and implementation pathways, which necessitates a rigorous and transparent evaluation mechanism to support informed decision-making under uncertainty. This study proposes an integrated spherical fuzzy multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) framework for assessing and ranking smart airport development plans. Subjective expert judgments are modeled using spherical fuzzy sets, allowing for the simultaneous consideration of positive, neutral, and negative membership degrees to better capture linguistic and ambiguous information. Expert importance is determined through a hybrid weighting scheme that combines a social trust network model with an entropy-based objective measure, thereby reflecting both relational credibility and informational contribution. Criterion weights are computed through an integrated approach that merges criteria importance through the inter-criteria correlation (CRITIC) method with the stepwise weight assessment ratio analysis (SWARA) method, balancing data-driven structure and expert strategic preferences. The weighted evaluations are aggregated using a spherical fuzzy extension of the combined compromise solution (CoCoSo) method to obtain the final rankings. A case study involving smart airport development planning in China is conducted to illustrate the applicability of the proposed approach. Sensitivity, ablation, and comparative analyses demonstrate that the framework yields stable, discriminative, and interpretable rankings. The results confirm that the proposed method provides a reliable and practical decision support tool for smart airport development and can be adapted to other smart transportation planning contexts.

1. Introduction

The aviation sector is entering a period of profound transformation driven by the rapid diffusion of digital and intelligent technologies. As global air traffic continues to rise, airports face increasing pressure to handle larger volumes of passengers and cargo while maintaining rigorous standards of safety, security, and service quality. Conventional management practices, which often rely on fragmented procedures and limited data utilization, have become insufficient for meeting these demands. In response, the concept of the smart airport has emerged as a central direction for modern airport development [1]. Smart airports are not simply incremental upgrades of existing infrastructure. They represent a comprehensive reconfiguration of airport operations and management to align with the requirements of the digital era [2,3,4].

A smart airport integrates multiple advanced technologies to create an intelligent and interconnected ecosystem. Core enablers such as the Internet of Things (IoT), artificial intelligence (AI), big data analytics, and automation work together to enhance efficiency, safety, and passenger experience [5,6]. IoT-based sensing networks provide continuous real-time data on passenger movements, equipment conditions, and environmental variables, which supports evidence-based decision-making and more efficient operational control [7]. AI and machine learning algorithms analyze these data to predict maintenance requirements, optimize scheduling, and improve security management, allowing airport systems to act proactively rather than reactively [6]. Big data analytics further strengthen strategic decisions by identifying trends, forecasting passenger demand, and optimizing resource allocation [1]. Automation technologies improve reliability and throughput in routine operations such as check-in, security screening, and baggage handling. Automated kiosks, robotic baggage systems, and intelligent gates exemplify how automation can reduce delays and enhance precision [8]. Together, these technologies foster a data-driven airport environment that improves service continuity and passenger satisfaction. Real-time flight updates, personalized information, and intelligent customer service systems create a smoother and more engaging travel experience [9,10].

The development of smart airports is therefore a vital pathway to improve both passenger experience and operational effectiveness in modern air transportation. Passenger satisfaction has become an important factor influencing airport competitiveness and economic performance, particularly in regions such as China where high-speed rail has become a strong alternative to air travel. To maintain service quality and operational efficiency, airports must integrate advanced digital and intelligent technologies [11]. However, implementing smart airport initiatives requires significant investment and careful coordination among multiple systems and stakeholders. Hence, a systematic and transparent evaluation framework is needed to compare and prioritize development alternatives [12]. The objective of this study is to develop a robust method for assessing smart airport development strategies. A multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) approach is adopted to account for the diverse technological, operational, and sustainability-related factors that affect development outcomes. Through a structured evaluation of these factors, decision-makers can select strategies that balance innovation, feasibility, cost efficiency, and long-term resilience.

The evaluation of alternative smart airport development plans requires the consideration of multiple interrelated aspects. In light of the growing complexity and strategic importance of this issue, the present study seeks to address the following research questions:

- RQ1: Which factors play critical roles in influencing the evaluation and prioritization of smart airport development plans?

- RQ2: In what ways can uncertainty modeling techniques such as fuzzy set theory and spherical fuzzy sets support the representation of ambiguous and imprecise information within the evaluation process?

- RQ3: How can advanced multi-criteria decision-making tools, including stepwise weight assessment ratio analysis (SWARA), criteria importance through inter-criteria correlation (CRITIC), and the combined compromise solution (CoCoSo) method, be systematically integrated to enhance the objectivity and robustness of the decision-making process?

- RQ4: What practical insights can be derived from the evaluation of smart airport development plans, and how can these insights inform future initiatives in smart airport operations and the broader smart aviation context?

This study investigates the evaluation and selection of smart airport development plans from an operational perspective using MCDM techniques. Several motivations underpin this research.

(1) Smart airport construction has become a strategic priority in the modernization of civil aviation in China. Despite its growing relevance, systematic frameworks for assessing and comparing development plans remain limited. This study aims to establish a comprehensive and transparent evaluation model to help fill this methodological gap.

(2) Decision-making in smart airport planning often involves incomplete and uncertain information. Expert judgment is therefore essential to supplement data scarcity and capture domain knowledge. The spherical fuzzy set (SFS) provides an effective mechanism to model ambiguity and hesitation, making it an appropriate foundation for representing expert evaluations.

(3) Since multiple experts are usually involved in the assessment process, the reliability of their opinions must be objectively quantified. To achieve this, this study integrates a social trust network model, which captures subjective trust among experts, with an entropy-based weighting scheme, which reflects the variability in their evaluations. This hybrid structure improves the credibility and balance of the aggregated expert opinions.

(4) Weight determination for multiple evaluation criteria is another crucial step in achieving reliable results. To ensure comprehensiveness, both subjective and objective dimensions of importance are considered. The SWARA method is applied for subjective weighting, while the CRITIC method captures objective variations among criteria. Their combination allows for a more balanced and consistent assessment of criterion importance.

(5) Evaluating smart airport development plans is inherently a complex MCDM problem that requires a method capable of producing stable and interpretable results across diverse conditions. The CoCoSo method, known for identifying compromise solutions through the integration of multiple decision strategies, is selected for this purpose to strengthen the robustness of the evaluation outcomes.

In multi-attribute decision-making, attribute weights play a decisive role because they encode the relative importance of criteria and thus directly affect the final ranking of alternatives. Existing approaches can be broadly classified into subjective weighting, which relies on expert preferences; objective weighting, which is derived from data dispersion and inter-criteria correlation; and combined weighting, which attempts to reconcile these two perspectives. Recent studies on case-based reasoning for medical insurance fraud detection and on cloud model-based multi-stage decision-making under probabilistic interval-valued hesitant fuzzy environments further underline the importance of carefully designed weighting schemes in complex decision contexts [13,14]. In this study, the proposed SF–CRITIC and SF–SWARA-based scheme follows the combined weighting philosophy by incorporating both expert knowledge and data-driven information in a unified manner.

Building upon these motivations, this research proposes an integrated MCDM framework for evaluating smart airport development plans. The framework incorporates the social trust network, entropy measure, SWARA, CRITIC, and CoCoSo methods within a spherical fuzzy environment. Through this integration, uncertain expert assessments are effectively modeled, while both expert and criterion weights are consistently addressed. The proposed approach provides a unified and rigorous structure for ranking and selecting smart airport development alternatives under uncertainty.

The significance of this research can be viewed from two complementary perspectives. From a practical perspective, a systematic and credible evaluation framework helps decision-makers identify the most feasible and effective development strategies, enabling airport operators and policymakers to allocate resources to the most influential factors and improve operational performance. From a theoretical perspective, this study advances MCDM research by demonstrating how human reasoning in complex decision environments can be approximated through fuzzy modeling without requiring direct human intervention. The integration of advanced weighting and aggregation techniques further supports rational and transparent decision-making under uncertainty.

The key contributions of this study are summarized below:

(1) An integrated MCDM framework is developed for evaluating smart airport development plans, capable of capturing uncertain expert knowledge and reflecting both subjective and objective evaluation dimensions.

(2) A hybrid expert weighting scheme is proposed, combining the social trust network with the entropy measure to determine expert credibility in a balanced and data-driven manner.

(3) An integrated criterion weighting approach is introduced, merging the CRITIC and SWARA methods under a spherical fuzzy environment to account for both subjective perception and objective data dispersion.

(4) The CoCoSo method is employed to synthesize the evaluation results, linking expert and criterion weighting processes with the spherical fuzzy decision environment, thereby enhancing the reliability and interpretability of the final rankings of smart airport development plans.

In addition, smart airport development is not confined to a single national or regional context but has become a global priority that must respond to heterogeneous regulatory regimes, technological infrastructures, and socio-economic conditions. The proposed framework is therefore conceived as a flexible decision support tool that can be adapted to different regional settings by adjusting the evaluation criteria, expert structures, and data sources while preserving the core methodological structure. The main methodological novelty of this study lies in developing an integrated spherical fuzzy decision-making framework for smart airport development that (i) combines social trust-based and entropy-based expert weighting in a unified scheme, (ii) adopts a hybrid SF–CRITIC and SF–SWARA criterion weighting mechanism to balance subjective and objective information, and (iii) employs the SF–CoCoSo compromise solution to transform the weighted spherical fuzzy evaluations into a robust and discriminative ranking of development plans under expert uncertainty and heterogeneity.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews the relevant studies and theoretical background associated with smart airport evaluation. Section 3 outlines the essential preliminaries required for the proposed framework. Section 4 develops the MCDM model in detail. Section 5 describes a real-world case study that demonstrates the applicability of the proposed approach, and Section 6 analyzes and discusses the obtained results. Finally, Section 7 concludes this paper and highlights the key findings and future research directions.

2. Related Works

2.1. Smart Airports

The emergence of smart airports reflects the growing influence of Industry 4.0 technologies in the aviation sector. A smart airport can be understood as a technologically enabled system that integrates digital, sensing, and automation solutions into airport operations to achieve seamless, efficient, and data-driven management. Under this paradigm, technologies such as the Internet of Things (IoT), artificial intelligence (AI), big data analytics, and advanced automation are utilized to optimize resource allocation, improve safety management, and enhance passenger service quality. Smart airports aim to transform the passenger journey through features such as self-service check-in, biometric identification, personalized notifications, and real-time information services. Sustainability has also become a central focus, with energy-efficient infrastructure, smart lighting, and digital waste management contributing to greener operations.

The rapid expansion of global air transport demands adaptive airport systems capable of managing higher passenger and cargo volumes without compromising service quality. Smart airports are regarded as a viable response to these challenges by improving efficiency, reliability, and safety in airport management. Consequently, research on smart airport technologies has expanded considerably in recent years. Kalaivani et al. [15] discussed how the integration of IoT technology into the airline industry has led to the development of intelligent airports and provided an overview of how the IoT changes the airport experience for passengers. Khadonova et al. [3] examined the implementation of digital technologies at Russian airports, highlighting the role of GLONASS/GPS navigation, Bluetooth Low Energy, M2M communication, and industrial IoT in asset tracking and process control. Rubio-Andrada et al. [16] analyzed the smart airport concept from the passenger viewpoint, emphasizing satisfaction with the deployment of intelligent services. Booranakittipinyo et al. [17] employed sentiment analysis to explore travelers’ perceptions of smart airport facilities. Göçmen [12] proposed an evaluation framework covering environmental impacts, docking and navigation, object detection, communication integration, and terminology standardization as key smart airport dimensions. Göçmen [12] also developed a decision support system using the analytical hierarchy process (AHP) and a fuzzy inference system (FIS) to evaluate performance standards. Wandelt and Zheng [18] presented a comprehensive review of the current state of the art in intelligent air transportation systems, supporting the transformation of the aviation industry into a connected, efficient, and sustainable ecosystem. Agrawal et al. [19] explored the crucial role of airport automation and digitization in addressing challenges faced by the travel sector and improving traveler experience through efficient identity verification and reduced wait times.

In China, the modernization of airport infrastructure has progressed rapidly, positioning many airports at a relatively high technological maturity level. Nonetheless, the further integration of IoT-based systems offers opportunities to enhance operational resilience, efficiency, and real-time monitoring capability. A growing number of Chinese airports have begun adopting or planning to adopt smart airport solutions. However, such initiatives involve diverse technologies including self-service systems, cybersecurity mechanisms, biometric identification, cloud-based services, and business intelligence platforms. Determining which technological areas should receive priority investment remains a complex task that requires systematic evaluation.

Existing studies primarily emphasize technological implementation and system integration, while relatively few have developed structured frameworks for comparing and prioritizing different development strategies. The absence of such evaluation mechanisms limits decision-makers’ ability to allocate resources efficiently and hinders coordinated progress toward fully intelligent airport systems. Therefore, establishing a rigorous and transparent evaluation approach for smart airport development plans is essential to support strategic decision-making and guide future infrastructure investments.

2.2. Spherical Fuzzy Set

Fuzzy set theory, first proposed by Zadeh [20], provides a foundational framework for describing and analyzing imprecise and vague information. By assigning degrees of membership to elements, it has become a powerful tool for handling uncertainty in a wide range of applications [21,22,23]. Traditional fuzzy sets, however, employ only a single membership degree, which restricts their ability to capture hesitation or neutrality in expert judgment. To overcome this limitation, Atanassov [24] developed the intuitionistic fuzzy set (IFS), which introduces both membership and non-membership functions, allowing for partial hesitation to be represented.

Building upon this advancement, Kutlu Gündoğdu and Kahraman [25] proposed the spherical fuzzy set (SFS), characterized by three independent functions that represent positive, neutral, and negative membership degrees. This three-parameter representation satisfies the condition that the squared sum of these degrees does not exceed one, enabling a more flexible depiction of uncertainty. SFSs have demonstrated strong representational capability and have been increasingly adopted in multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) research [26,27,28]. Several studies illustrate their utility. Mathew et al. [29] combined the AHP and the technique for order of preference by similarity to ideal solution (TOPSIS) within a spherical fuzzy framework to support advanced manufacturing system selection, where the spherical fuzzy AHP derived the weights of criteria, and spherical fuzzy TOPSIS produced the ranking of alternatives. Kutlu Gündoğdu and Kahraman [30] defined interval-valued SFSs and constructed an interval-valued spherical fuzzy TOPSIS approach for evaluating 3D printer selection problems. Liu et al. [31] introduced linguistic SFSs to extend the multi-attributive border approximation area comparison (MABAC) and the interactive and multi-criteria decision-making (TODIM) methods, demonstrating their applicability in assessing public opinions on shared bicycles in China. Rahnamay Bonab et al. [32] integrated the Choquet integral with group decision-making under the spherical fuzzy environment to evaluate autonomous logistics vehicles, offering decision-makers greater flexibility in expressing preference. Akram et al. [33] incorporated SFSs into the preference ranking organization method for enrichment evaluation (PROMETHEE) and applied this model to identify optimal sites for Fangcang shelter hospitals in Wuhan during the COVID-19 pandemic. Zahid and Akram [34] designed a multi-criteria group decision-making technique, the spherical fuzzy ELECTRE III method, to address waste management problems by investigating waste-to-energy technologies. These studies collectively highlight the versatility and adaptability of SFSs in modeling uncertainty in complex decision contexts.

2.3. MCDM Methods

In MCDM, one of the most critical tasks is to determine the relative importance of criteria that influence the final decision outcome. Various weighting methods have been developed and can generally be grouped into two categories: subjective and objective.

Subjective approaches rely on expert evaluation to assign importance levels to criteria. Representative methods include the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) [35,36], the best–worst method (BWM) [37], and SWARA [38]. Among these, SWARA offers a relatively simple yet systematic mechanism that ranks criteria according to expert judgments without requiring pairwise comparisons. This method has been widely used across domains such as sustainable mining, biomedical waste management, and human resource planning. Deveci et al. [39] used a Fermatean fuzzy SWARA to prioritize potential risks in sustainable mining operations. Seikh and Mandal [40] applied SWARA within an integrated MAGDM model for biomedical waste management under an interval-valued Fermatean fuzzy environment. Saeidi et al. [41] combined Pythagorean fuzzy SWARA with TOPSIS to rank sustainability factors in human resource management. Bouraima et al. [42] employed interval-rough SWARA within an IR-SWARA–CoCoSo model for group decision-making.

Objective weighting methods derive the relative importance of criteria directly from quantitative evaluation data, thereby reducing subjectivity. Notable examples include the CRITIC approach [43], entropy-based schemes [44], and related data-driven techniques [45,46]. The CRITIC method determines weights by assessing both the variability and correlation among criteria, capturing their mutual influence. Its flexibility has led to applications across various engineering and management problems. Wen et al. [47] incorporated CRITIC with a cloud model to assess the operational safety of straddle-type monorail systems. Haktanır and Kahraman [48] combined CRITIC and REGIME in a Pythagorean fuzzy environment for selecting wearable health technologies. Akram et al. [49] applied a CRITIC–EDAS hybrid model for evaluating industrial waste management techniques. Li et al. [50] integrated CRITIC and VIKOR for pipeline risk analysis, accurately reflecting the correlations among multiple risk factors.

Beyond weighting methods, many comprehensive MCDM models have been proposed to improve decision quality [51]. Among them, the CoCoSo method, proposed by Yazdani et al. [52], represents an effective approach that aggregates multiple compromise strategies to determine an optimal alternative. CoCoSo integrates the principles of the weighted sum model and the weighted product model and is capable of maintaining a stable ranking of alternatives even when the alternative set is modified [53]. This robustness has promoted its use in diverse contexts, such as spatial planning, defense technology, and healthcare evaluation. Ghasemi et al. [54] combined CoCoSo with a geographic information system to analyze the spatial distribution of green spaces in Tehran. Erdal et al. [55] integrated fuzzy Shannon entropy with fuzzy CoCoSo to support missile system selection under uncertainty. Wang and Wang [56] formulated a group decision-making framework for healthcare waste treatment using linguistic terms and the weakened hedge Bonferroni mean operator within the CoCoSo model. Chen et al. [57] employed Fermatean fuzzy linguistic CoCoSo for occupational hazard risk prioritization. Haseli et al. [58] merged CoCoSo with the base criterion method under fuzzy ZE-numbers to evaluate sustainable alternatives for managing urban transport crises.

Social networks and trust information have also been incorporated into group decision-making. Luo and Zhang [59] proposed a multi-criteria group decision-making model that utilizes an expert trust network and cloud model operators for comprehensive evaluation based on linguistic variables. Wang et al. [60] introduced a consensus model that incorporates both external trust relationships among experts and the internal reliability of experts within social network group decision-making. Chen et al. [61] proposed a decentralized trust management system based on blockchain technologies to secure information dissemination in intelligent transportation systems. Luo et al. [62] developed a three-stage recommendation method for new energy vehicles that incorporates users’ preferences and social trust relationships.

Recently, several studies have investigated the application of MCDM methods in smart transportation. Kundu et al. [63] proposed an integrated fuzzy MCGDM framework that combines fuzzy BWM and fuzzy multi-attribute ideal–real comparative analysis to evaluate urban public transportation systems. Santos-Arteaga et al. [64] transformed an MCDM setting into a game-theoretical scenario to account for the strategic evaluations and credibility of experts in sustainable transportation assessment. Krishankumar et al. [65] developed a decision-making framework using q-rung fuzzy information and the measurement of alternatives and ranking based on compromise solution (MARCOS) method for the evaluation of zero-carbon measures to promote sustainable transport in smart cities. Kilic and Demirel [66] reviewed existing research that utilizes fuzzy decision systems for sustainable public transport, focusing on decision-making processes and mechanisms in uncertain environments.

Despite extensive progress in the field, very few studies have explored how these advanced decision-making tools can be applied to the evaluation of smart airport development plans. Given the complex and uncertain nature of such strategic infrastructure decisions, the integration of spherical fuzzy sets with MCDM techniques can provide a more rigorous and reliable analytical framework. The present study therefore combines SWARA, CRITIC, and CoCoSo within the spherical fuzzy environment, together with a social trust-based expert weighting scheme, to develop a comprehensive method for assessing and ranking smart airport development strategies.

In summary, existing studies typically either (a) use social network or trust information without spherical fuzzy modeling, (b) employ a single subjective or objective weighting scheme under spherical fuzzy sets, or (c) apply CoCoSo-type ranking without jointly considering expert trust structures and hybrid weighting. To the best of my knowledge, no work has integrated social trust-based expert weighting, hybrid SF–CRITIC and SF–SWARA criterion weighting, and SF–CoCoSo ranking within a single spherical fuzzy framework tailored to smart airport development.

3. Preliminaries

This section recalls the fundamental concepts and operations of SFS, which provide the mathematical basis for the proposed framework.

Definition 1

([25]). Let X be a universal set. A spherical fuzzy set D on X is defined as

where , , and denote, respectively, the positive, neutral, and negative membership degrees of the element x. These functions satisfy , and

The corresponding hesitation degree is given by . For convenience, the triple is referred to as a spherical fuzzy number (SFN).

Definition 2

([25]). For an SFN , the score function is defined as

Definition 3

([25]). For the same SFN , the accuracy measure is defined as

Let and be two SFNs. Their comparison is carried out according to the following rules:

- 1.

- If , then .

- 2.

- If , then

- (a)

- if , then ;

- (b)

- if , then .

For three SFNs , , and , and a real number , the basic operations are defined as follows:

- 1.

- .

- 2.

- .

- 3.

- .

- 4.

- .

Definition 4

([25]). The Euclidean distance between two SFNs and is defined as follows:

Definition 5

([25]). Consider a finite family of SFNs and a corresponding weight vector . The spherical fuzzy weighted average (SFWA) operator is defined as

Definition 6

([25]). Under the same setting, the spherical fuzzy weighted geometric (SFWG) operator is given by

Definition 7

([67]). For an SFN , the associated entropy measure is defined as

4. Research Framework

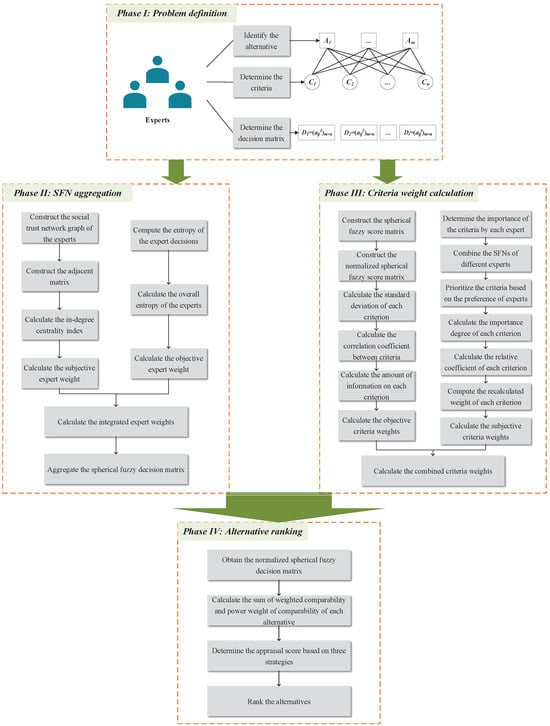

In this section, an integrated MCDM approach based on the social trust network, CRITIC, SWARA, and CoCoSo methods is proposed for evaluating and ranking smart airport development alternatives within a spherical fuzzy environment. The method consists of four phases: problem definition, spherical fuzzy decision matrix aggregation, criterion weight calculation, and alternative ranking. The overall framework of the proposed method is shown in Figure 1. It is designed for a strategic planning problem in which expert evaluations are uncertain and heterogeneous, criteria are interrelated, and candidate plans exhibit close performance. In this context, the social trust network captures expert reliability and influence, SF–CRITIC accounts for objective information and inter-criteria correlation, SF–SWARA reflects expert priority structures, and SF–CoCoSo produces a compromise-based ranking from the weighted spherical fuzzy evaluations. Their combination addresses expert heterogeneity, criterion interdependence, and trade-offs among alternatives in a single coherent decision-making pipeline.

Figure 1.

Framework of proposed method.

4.1. Phase I: Problem Definition

Step 1: Decision-making problem determination

Consider the smart airport development evaluation problem with a group of t experts , a set of m alternatives , and n evaluation criteria . The kth expert provides evaluations in the form of SFNs, leading to the individual decision matrix

where denotes the spherical fuzzy evaluation of the ith alternative on the jth criterion given by expert . These SFNs are obtained by converting the linguistic judgments of the experts.

In this study, the linguistic term set and the corresponding spherical fuzzy numbers in Table 1 are used [68]. For each linguistic term , the associated triplet satisfies and provides a symmetric and monotone progression from very low to very high assessments in the spherical fuzzy domain. This scale is chosen because it is consistent with the original definition of spherical fuzzy sets by explicitly modeling positive, neutral, and negative membership degrees; has been widely used in spherical fuzzy MCDM studies; and offers a simple yet sufficiently fine granularity for expert linguistic evaluations in the smart airport development context. Although other linguistic parameterizations could be employed in principle, using this established spherical fuzzy scale facilitates comparability and preserves the intended semantics of the three membership components.

Table 1.

Spherical fuzzy linguistic term scale.

4.2. Phase II: SFN Aggregation

Step 2: Compute the experts’ subjective weights

Since the decision-making process involves multiple experts with heterogeneous backgrounds and experience levels, it is essential to assign their weights in a suitable manner to improve the reliability of the aggregated results. In this study, a social trust network is employed to derive the subjective weights of the experts as follows.

Step 2-1: By analyzing the trust relationships among the experts, construct a social trust graph to represent the trust relations among them, where nodes correspond to experts, and edge represents the trust from to .

Step 2-2: Construct the adjacency matrix based on the trust graph to represent the trust among the experts as

where denotes the trust degree assigned by expert to expert .

Step 2-3: Calculate the in-degree centrality index of each expert with regard to the overall trust it receives from other experts as

Step 2-4: Calculate the subjective weight of each expert as

Compared with equal or purely entropy-based expert weighting, the social trust network allows the framework to distinguish between highly trusted and less trusted experts by using the structure of interpersonal trust relations. This is particularly important in strategic smart airport planning, where some stakeholders naturally play a more central role in shaping the decision.

Step 3: Compute the experts’ objective weights

To more comprehensively represent the importance and credibility of the experts, objective weights are computed based on the entropy of their evaluations as follows.

Step 3-1: For each element of the decision matrix of the experts, compute the corresponding entropy value as

where is the spherical fuzzy evaluation provided by expert for on .

Step 3-2: For the kth expert , calculate the overall entropy measure as

Step 3-3: Based on the entropy measure, calculate the objective weight of each expert as

Step 4: Calculate the integrated experts’ weights

In this step, by combining the subjective weight and the objective weight of each expert, the integrated weight of each expert is obtained as

Step 5: Aggregate the spherical fuzzy decision matrix

To obtain the comprehensive evaluations, the spherical fuzzy decision matrices of all experts are aggregated by considering the integrated expert weights. The aggregated decision matrix is given by

where is the aggregated evaluation of alternative on criterion and is obtained by

with SFWA denoting the spherical fuzzy weighted averaging operator using the expert weights .

4.3. Phase III: Criterion Weight Calculation

Step 6: Compute the objective criterion weights

To accurately determine the importance of the criteria, the objective weights are computed by extending the CRITIC method to the spherical fuzzy environment. In the SF–CRITIC method, the contrast intensity of each attribute is quantified using the standard deviation (SD), and the conflict among attributes is measured by the correlation coefficient. The procedure is summarized as follows.

Step 6-1: Based on the aggregated spherical fuzzy decision matrix, construct the spherical fuzzy score matrix , where

Step 6-2: Construct the normalized spherical fuzzy score matrix by normalizing the elements in S as

where , and .

Step 6-3: Calculate the SD of each criterion as

where .

Step 6-4: Calculate the correlation coefficient between criteria and as

Step 6-5: Compute the amount of information associated with each criterion as

Step 6-6: Calculate the objective criterion weight as

The SF–CRITIC method is used as the objective weighting component because it simultaneously considers the dispersion of criterion scores and the correlation among criteria so that criteria that are highly redundant receive lower weights than those that provide distinct information.

Step 7: Compute the subjective criterion weights

The subjective weights of the criteria are determined by extending the SWARA method with SFNs, where the importance of each criterion is estimated based on its position in an ordered ranking. The SF–SWARA-based subjective criterion weight calculation proceeds as follows.

Step 7-1: For each expert, determine the importance of the criteria using linguistic terms, and convert the linguistic terms into the corresponding SFNs.

Step 7-2: Aggregate the SFNs of different experts using the SFWA operator, and calculate the score degree and accuracy degree of the aggregated SFNs using Equations (2) and (3).

Step 7-3: Order the criteria from the most significant to the least significant according to the score degree and accuracy degree of the aggregated SFNs.

Step 7-4: Calculate the importance degree of each criterion, except for the first criterion, as

where denotes the score value of the jth criterion in the ranking order.

Step 7-5: Compute the relative coefficient of each criterion as

Step 7-6: Based on the relative coefficient, calculate the recalculated weight as

Step 7-7: Calculate the subjective criterion weight as

SF–SWARA is adopted as the subjective weighting component because it provides a simple and transparent procedure for experts to express relative importance through an ordered list and adjustment coefficients, which reduces cognitive burden while preserving nuanced priority information.

Step 8: Calculate the combined criterion weights

By integrating both the objective and subjective weights, the combined weight of each criterion is calculated as

where is a decision coefficient that controls the balance between the objective SF–CRITIC weights and the subjective SF–SWARA weights. A larger value of increases the influence of data-driven information, whereas a smaller value gives more emphasis to expert judgments. In this study, is adopted as the baseline value to give comparable importance to objective and subjective information.

In this way, the hybrid SF–CRITIC and SF–SWARA scheme integrates data-driven and judgment-driven information, avoiding the limitations of purely objective or purely subjective weighting in long-term infrastructure planning problems.

4.4. Phase IV: Alternative Ranking

In this study, to accurately and reliably obtain the evaluations of different smart airport development alternatives, the CoCoSo method is extended with SFNs, and the SF–CoCoSo method is employed. The procedure is detailed as follows.

Step 9: Obtain the normalized spherical fuzzy decision matrix

Based on the aggregated spherical fuzzy decision matrix, obtain the normalized spherical fuzzy decision matrix as

This normalization preserves the spherical fuzzy structure while ensuring that higher values of are consistently associated with more desirable performance for all criteria.

Step 10: Calculate the sum of weighted comparability and the power weight of comparability of each alternative

Based on the normalized spherical fuzzy decision matrix, calculate the sum of the weighted comparability of each alternative using the SFWA operator as

Then, calculate the power weight of comparability of each alternative using the SFWG operator as

Step 11: Determine the appraisal scores based on three strategies

Based on three appraisal strategies, the scores of each alternative are calculated as

where and denote the score values of and , respectively, and is a coefficient that controls the relative emphasis on the additive and multiplicative components in the third strategy. In the subsequent case study, is adopted as the baseline setting to assign equal importance to these two components.

Step 12: Rank the alternatives

By combining the three appraisal scores of each alternative, the overall utility is computed as

The alternatives are then ranked according to the descending order of .

The SF–CoCoSo method is selected as the core ranking tool for several reasons. First, CoCoSo is a compromise solution approach that simultaneously exploits additive and multiplicative aggregation operators, which allows it to capture both the cumulative performance of an alternative across all criteria and the balance among those criteria. This structure is suitable for strategic planning problems such as smart airport development, where candidate plans often exhibit close performance, and strong dominance in a few criteria should not fully compensate for weaknesses in others. Second, the CoCoSo formulation naturally incorporates the combined SF–CRITIC and SF–SWARA criterion weights so that the ranking procedure reflects both data-driven variability and expert-assessed strategic importance within a single appraisal index. Third, by working in the spherical fuzzy environment, the SF–CoCoSo method operates directly on evaluations characterized by positive, neutral, and negative membership degrees, thereby preserving more information about expert judgments under uncertainty than conventional crisp or single-valued fuzzy implementations. Consequently, SF–CoCoSo provides a robust and interpretable ordering of smart airport development plans that is consistent with the weighted spherical fuzzy decision matrix obtained in the earlier phases of the framework.

4.5. Stepwise Implementation in the Smart Airport Case

To clarify how the proposed framework is applied in practice, this subsection provides a stepwise description of its implementation in the smart airport development case.

Step 1 (Phase I): Problem setting and elicitation of expert evaluations. A group of decision-makers and a set of smart airport development plans and evaluation criteria are first defined. Each decision-maker then evaluates every plan with respect to each criterion using the linguistic term set shown in Table 1. These linguistic assessments are collected separately for all alternatives and criteria.

Step 2 (Phase I): Spherical fuzzy representation of linguistic evaluations. Each linguistic term is converted into a spherical fuzzy number according to the scale in Table 1. For each expert , this yields a spherical fuzzy decision matrix , where denotes the positive, neutral, and negative membership degrees corresponding to the evaluation of under by expert , as in Equation (8).

Step 3 (Phase II): Computation of expert weights using the social trust network and entropy. The experts express their mutual trust relationships, which are encoded into the social trust adjacency matrix defined in Equation (9). Based on the in-degree centrality in Equation (10), the subjective trust-based weights are obtained via Equation (11). In parallel, entropy-based objective weights are computed from Equations (12)–(14). These two components are combined through Equation (15) to produce the final expert weight vector , which corresponds to Phase II Steps 2–4.

Step 4 (Phase II): Aggregation of individual decision matrices. The individual spherical fuzzy decision matrices are aggregated into the group decision matrix by applying the SFWA operator with the expert weights , as in Equation (17). This aggregation corresponds to Phase II Step 5 and yields a single spherical fuzzy evaluation for each alternative with respect to each criterion .

Step 5 (Phase III): Determination of objective criterion weights using SF–CRITIC. The aggregated decision matrix R is transformed into the spherical fuzzy score matrix through Equation (18), which is then normalized to using Equation (19). Using , the standard deviation and correlation coefficients are computed via Equations (20) and (21). The information content of each criterion is calculated from Equation (22), and the objective SF–CRITIC weights are obtained using Equation (23). This implements Phase III Step 6.

Step 6 (Phase III): Determination of subjective criterion weights using SF–SWARA. The experts rank the criteria in terms of their perceived importance for smart airport planning. These qualitative judgments are first expressed by linguistic terms and converted into SFNs. The SFWA operator is used to aggregate expert views, and score and accuracy values are computed according to Equations (2) and (3). Following the SF–SWARA procedure in Equations (24)–(27), the ordered importance information is transformed into subjective criterion weights . This corresponds to Phase III Step 7.

Step 7 (Phase III): Construction of the combined criterion weights. The objective weights and subjective weights are combined through the decision coefficient according to Equation (28) to obtain the final criterion weights . This implements Phase III Step 8 and balances data-driven and judgment-driven information in the weighting process.

Step 8 (Phase IV): Ranking of alternatives using the SF–CoCoSo method. Using the aggregated spherical fuzzy decision matrix R and the final criterion weights , the SF–CoCoSo procedure described in Equations (29)–(35) is applied. First, the normalized matrix is obtained via Equation (29). The comparability measures and are then computed through the SFWA and SFWG operators in Equations (30) and (31). Next, the three appraisal scores are derived from Equations (32)–(34). Finally, the overall utility is calculated using Equation (35) to provide a compromise-based ranking of the smart airport development plans. This step corresponds to Phase IV Steps 9–12.

This stepwise description links each methodological component to a concrete operation in the smart airport case and clarifies how the integrated framework produces the final decision outcome.

5. Case Study

This section presents a practical application to demonstrate the feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed method for selecting optimal smart airport development alternatives.

5.1. Case Description

In recent years, the concept of the smart airport has gained increasing attention from both academia and industry for its potential to realize sustainable, resilient, and intelligent transportation hubs. To address the growing challenges of airport modernization, multiple strategic development plans have been proposed worldwide. In this study, a case concerning the development of a smart airport in Shandong Province is examined to provide systematic and reliable decision support for future planning.

A total of nine development alternatives are considered, denoted as . A panel of five domain experts , comprising two professors specializing in airport development, one professor in sustainability, and two senior managers from airport management enterprises, participated in the evaluation. Each expert has more than five years of experience in the aviation sector, which helps to ensure the credibility and representativeness of the assessments.

The nine smart airport development alternatives represent distinct strategic directions for airport transformation and are summarized as follows.

- Seamless Passenger Journey and One-ID (): A passenger-centered strategy that emphasizes the end-to-end digitalization of airport processes. Through biometric identity management, automated bag-drop systems, and mobile-based self-service platforms, this plan aims to minimize bottlenecks, enhance accessibility, and improve the overall travel experience.

- Airside and Terminal Operations Excellence (): An operations-driven initiative that incorporates Airport Collaborative Decision-Making (A-CDM), predictive maintenance, and integrated apron management. It focuses on increasing throughput, optimizing resource utilization, and reducing delays via IoT-enabled data coordination.

- Smart Baggage, Cargo, and Ground Logistics Automation (): A strategy that extends automation and digital traceability across baggage and cargo handling chains using RFID tracking, autonomous ground vehicles, and advanced baggage management systems to enhance reliability, efficiency, and operational resilience.

- Net-Zero Energy and Resource Circularity Program (): A sustainability-oriented approach that promotes decarbonization and circular resource use. It involves renewable energy deployment, the electrification of ground operations, water reuse, and intelligent waste management, supported by energy-efficient building design.

- Landside–Airside Multimodal Integration (): A multimodal transport strategy that connects the airport with rail, metro, and bus systems. Smart curbside and parking management systems are employed to mitigate congestion, enhance accessibility, and encourage low-carbon travel.

- Next-Generation Safety and Security Modernization (): A comprehensive modernization of safety and security systems that integrates advanced screening technologies, biometric verification, cyber defense, and emergency management platforms. The plan includes enhanced baggage scanners, drone detection, and improved runway safety technologies.

- Airport Digital Twin and Data Platform (): A data-centric strategy focusing on the creation of a digital twin of airport infrastructure. Enabled by IoT sensors and big data analytics, the digital twin supports predictive maintenance, real-time monitoring, and scenario simulations for improved decision-making and planning.

- Community, Noise, and Environmental Quality Management (): A socially and environmentally oriented plan that aims to mitigate the externalities of airport operations. It integrates noise mapping, low-noise flight procedures, air quality monitoring, and community engagement mechanisms to enhance transparency and public trust.

- Resilience, Health, and Emergency Preparedness (): A resilience-focused initiative designed to safeguard airport operations from pandemics, extreme weather, and cyber threats. It includes redundant power systems, enhanced ventilation, public health screening, and comprehensive emergency operations centers to support continuity under uncertainty.

For evaluation, eight key criteria are identified based on a literature review and expert consultation.

- Operational Efficiency (): Assesses the capability of each alternative to streamline operations such as check-in, security, boarding, and baggage handling. Key considerations include resource optimization, scalability, and real-time data utilization for decision support.

- Passenger Experience (): Evaluates enhancements in service quality, accessibility, personalization, and comfort. The objective is to reduce processing time and improve the overall passenger journey within the terminal.

- Technological Integration (): Measures the effectiveness of integrating advanced technologies such as AI, IoT, and automation, including system interoperability, cybersecurity robustness, and infrastructure adaptability to future technological evolution.

- Sustainability (): Focuses on environmental performance, encompassing energy efficiency, carbon emission reduction, renewable energy utilization, and sustainable building materials and design.

- Economic Impact (): Assesses economic viability through cost–benefit analysis, return on investment, job creation, and contributions to regional economic development.

- Safety and Security (): Examines the improvement in safety and security mechanisms, including threat detection, biometric identification, emergency response, and compliance with aviation safety standards.

- Customer Satisfaction (): Evaluates feedback and engagement mechanisms, loyalty programs, and communication efficiency to sustain passenger satisfaction and brand loyalty.

- Risk Management (): Measures the robustness of risk identification and mitigation, including contingency planning, crisis response, and resilience to operational disruptions.

The set of eight criteria was obtained through a combined literature- and expert-driven process. First, a structured review of recent studies on smart airports, smart aviation, and airport modernization, as well as relevant industry reports and policy documents, was conducted to compile an initial long list of potential evaluation dimensions. This list covered technical, operational, service-oriented, and strategic aspects of smart airport development. Second, the preliminary criteria were discussed with a panel of domain experts, including senior managers from the focal airport, technical staff from the information and operations departments, and academic experts in aviation management. Through iterative discussion, overlapping or marginal items were merged or removed, and the wording and scope of the remaining items were refined. Finally, the expert panel confirmed that the resulting eight criteria jointly provide a comprehensive and non-redundant representation of the key priorities for smart airport development in the considered context.

All numerical calculations in this case study, including the implementation of the proposed method, the comparative analysis, and the sensitivity and ablation analyses, were carried out in MATLAB R2023b.

5.2. Results

In this case, the proposed method is employed to evaluate and select the optimal smart airport development plan. The main computational steps are summarized below.

Step 1: The five experts provide their evaluations of the nine smart airport development alternatives with respect to the eight criteria using the linguistic term set described in Section 4. These linguistic terms are converted into spherical fuzzy numbers according to the linguistic scale in Table 1. The resulting spherical fuzzy decision matrices for experts – are reported in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6.

Table 2.

Spherical fuzzy decision matrix of .

Table 3.

Spherical fuzzy decision matrix of .

Table 4.

Spherical fuzzy decision matrix of .

Table 5.

Spherical fuzzy decision matrix of .

Table 6.

Spherical fuzzy decision matrix of .

To illustrate the conversion process, consider the evaluation of alternative under criterion of expert , which is assessed with the linguistic term “High”. According to Table 1, this term corresponds to the spherical fuzzy number

which satisfies . Applying this mapping to all linguistic evaluations yields the spherical fuzzy decision matrices that serve as inputs to the subsequent stages of the framework.

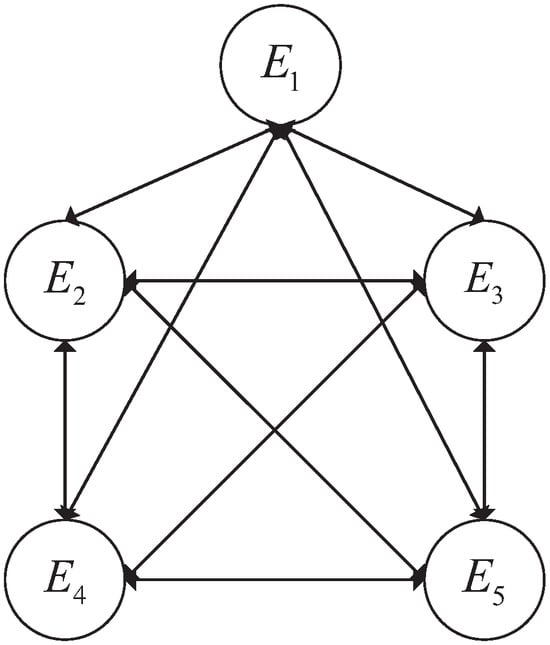

Step 2: Based on the trust relationships among the experts, the social network trust graph is constructed, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Social network trust graph with five experts.

Then, the adjacency matrix that represents the trust among the experts is obtained as

Based on the adjacency matrix, the in-degree centrality indices of the experts are calculated via Equation (10) as . Thus, according to Equation (11), the subjective weights of the experts are

Step 3: According to the spherical fuzzy decision matrices of the experts, the entropy values of their evaluations are calculated using Equation (12), and the overall entropy measure of each expert is obtained as

Based on these entropy measures, the objective weights of the experts are

Step 4: By combining the subjective and objective weights, the integrated weights of the experts are obtained using Equation (15) as

Step 5: Based on the spherical fuzzy decision matrices of the experts and their integrated weights, the aggregated spherical fuzzy decision matrix is obtained by using Equation (16). The resulting group decision matrix is reported in Table 7.

Table 7.

Aggregated spherical fuzzy decision matrix.

Step 6: To obtain the objective criterion weights, the spherical fuzzy score matrix is first computed using Equation (18), as reported in Table 8.

Table 8.

Spherical fuzzy score matrix.

The normalized spherical fuzzy score matrix is then constructed using Equation (19), and the SD of each criterion is calculated via Equation (20) as

The CRC values between each pair of criteria, obtained using Equation (21), are

The amount of information carried by each criterion, computed via Equation (22), is

Finally, the objective weights of the criteria are obtained using Equation (23) as

Step 7: To determine the subjective weights of the criteria, the experts evaluate the importance of each criterion using linguistic terms, which are converted into the corresponding SFNs listed in Table 9.

Table 9.

Spherical fuzzy judgments on the importance of the criteria.

The SFNs provided by different experts are aggregated using Equation (7), and the corresponding score values for each criterion are calculated as

The criteria are then ranked in descending order according to these scores, and the importance degree , relative coefficient , and recalculated weight are obtained as summarized in Table 10.

Table 10.

SF–SWARA calculation results.

Hence, the subjective weights of the criteria are obtained via Equation (27) as

Step 8: Based on the objective and subjective criterion weights, the combined criterion weights are calculated using Equation (28) as

In this case study, the decision coefficient in Equation (28) is set to , which reflects an equal emphasis on the subjective SF–SWARA weights and the objective SF–CRITIC weights when constructing the combined criterion weights.

Step 9: Considering the characteristics of the criteria, the aggregated spherical fuzzy decision matrix is normalized using Equation (29). Since all criteria in this case are benefit criteria, the normalized spherical fuzzy decision matrix coincides with the aggregated matrix in Table 7.

Step 10: Using the SFWA and SFWG operators, the sum of weighted comparability and the power weight of comparability for each alternative are obtained, as summarized in Table 11.

Table 11.

and of each alternative.

Step 11: By applying Equations (32)–(34), the appraisal scores , , and for each alternative are calculated, as listed in Table 12. In this case, the coefficient in Equation (34) is set to , which yields a balanced compromise among the three aggregation strategies embedded in the SF–CoCoSo method and avoids overemphasizing any single partial index.

Table 12.

The appraisal scores of each alternative.

The values and are determined in consultation with domain experts. The experts indicated that, for strategic smart airport planning, neither purely subjective nor purely data-driven information should dominate the weighting stage, and the different aggregation components within SF–CoCoSo should be treated in a balanced way. The chosen parameter values therefore implement this compromise in a transparent and reproducible manner.

Step 12: Using Equation (35), the overall utility of each alternative is obtained (Table 12). Ranking the alternatives in descending order of yields

Hence, is identified as the most preferred smart airport development alternative in the considered setting.

From the combined spherical fuzzy evaluations and the hybrid criterion weights, it can be observed that and achieve the highest overall scores on the most influential criteria. In particular, exhibits very strong performance on the criteria that receive the largest combined weights, which capture core smart airport priorities such as operational efficiency, passenger experience, technological integration, and safety and security. At the same time, attains at least medium performance on the remaining criteria, so no severe trade-offs arise that could offset these advantages in the aggregated appraisal score.

Alternative also performs strongly on several highly weighted criteria and shows pronounced strengths on sustainability and community-related dimensions. However, its performance on some operational and implementation-oriented criteria is slightly weaker than that of , which leads to a marginally lower composite score and explains its position as the second-ranked plan. The next group of alternatives, represented by and , combines solid improvements in airside and terminal operations with notable contributions to energy efficiency and resource circularity but does not match the simultaneous strength of on the most critical criteria.

In contrast, alternatives such as and obtain lower overall utilities. These plans emphasize important but comparatively more specialized dimensions, such as landside–airside multimodal integration and ground logistics automation, which are perceived by the experts as secondary to immediate needs in safety, security, core operational performance, and environmental stewardship in the current development phase.

Overall, the results indicate that strategies directly linked to next-generation safety and security modernization and to environmental and community impact management receive the highest decision weight in the evaluated context. This pattern reflects both the operational imperatives of modern airports and the broader societal expectations for sustainable and resilient air transport infrastructure. The case study thus illustrates how the proposed spherical fuzzy MCDM framework can support transparent and structured prioritization among competing smart airport development pathways.

6. Evaluation and Discussion

According to the case study results, the proposed spherical fuzzy MCDM framework can effectively evaluate multiple smart airport development alternatives and identify the most suitable plan. The analysis shows that is selected as the preferred alternative, in agreement with the judgments of the expert panel and with the current strategic focus on enhancing safety and security in airport development practice. To further assess the performance, robustness, and interpretability of the proposed framework, additional analyses are carried out in this section.

6.1. Sensitivity Analysis

To analyze the robustness of the proposed framework with respect to its main parameters, two sets of sensitivity analyses are carried out for the coefficients and . The first concerns the construction of the combined criterion weights, and the second concerns the internal aggregation mechanism of the SF–CoCoSo ranking procedure.

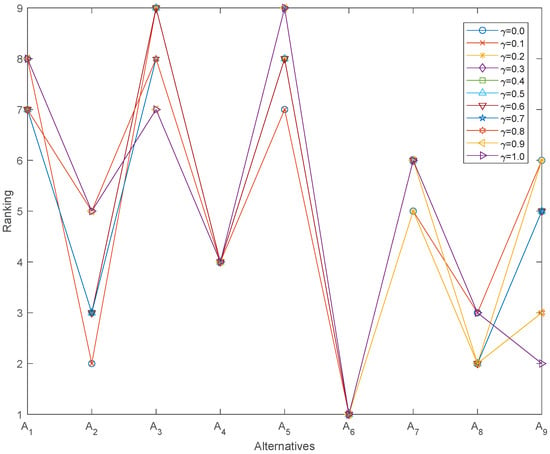

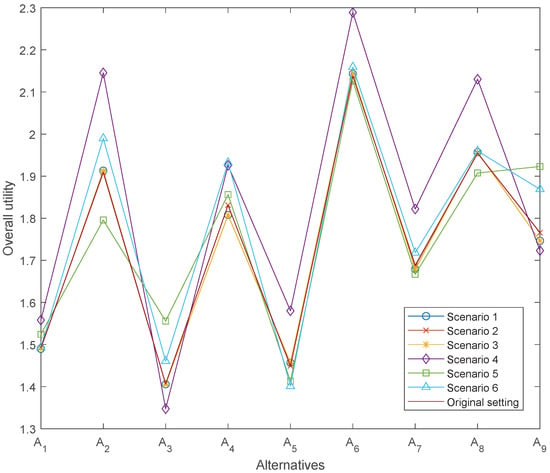

In this study, the decision coefficient in Equation (28) controls the balance between the subjective SF–SWARA weights and the objective SF–CRITIC weights when generating the combined criterion weights. To assess its impact, eleven values of are considered from to in increments of . For each value of , the combined weights are recalculated, and the complete evaluation procedure is repeated. The corresponding utility values and rankings of the nine smart airport development alternatives are reported in Table 13 and illustrated in Figure 3.

Table 13.

Evaluation results with different values of .

Figure 3.

Ranking results with different values of .

From Table 13 and Figure 3, it can be observed that changes in lead to moderate variations in the utility values and rankings of some mid-ranked alternatives. When is close to 0, the combined criterion weights are dominated by subjective SF–SWARA information, and alternatives such as and benefit from criteria that experts regard as strategically important but less dispersed in the data. As increases towards 1, the combined weights are increasingly driven by the objective SF–CRITIC information, and the utilities of some alternatives, such as , , and , become more sensitive to the empirical variation and correlation structure of the criterion scores. These shifts manifest as changes in their relative positions within the middle of the ranking.

However, the main recommendation of the framework remains unchanged. Alternative is consistently ranked first for all values of in the range , and alternative is consistently ranked last. The remaining alternatives exhibit only local rank reversals among neighboring positions. This behavior indicates that, although the balance between subjective and objective weighting influences the prioritization of secondary development plans, the identification of as the most favorable strategy is robust with respect to substantial changes in . The results therefore support the use of as a reasonable compromise that gives comparable importance to expert judgment and data-driven information without altering the core decision outcome.

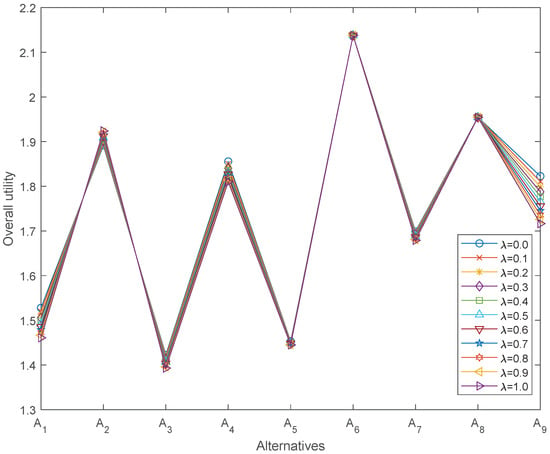

The coefficient in Equation (34) controls the relative emphasis of the third CoCoSo appraisal strategy within the SF–CoCoSo aggregation scheme and thus affects the final appraisal score and the overall utility . To examine its influence, eleven values of from to are considered while keeping fixed at its baseline value. For each , the appraisal scores and utilities are recomputed. The results are summarized in Table 14 and Figure 4.

Table 14.

Evaluation results with different values of .

Figure 4.

Evaluation results with different values of .

From Table 14 and Figure 4, it can be seen that variations in induce smooth and monotonic changes in the utility values of all alternatives, but these changes are relatively small in magnitude. More importantly, the ranking order of the alternatives remains identical for all tested values of . In particular, consistently attains the highest utility value, and consistently attains the lowest. The intermediate alternatives preserve their relative positions as well, so no rank reversals occur when the emphasis within the SF–CoCoSo aggregation shifts from the average-based to the extremum-based components.

From a decision-making perspective, these findings imply that the internal trade-off mechanism of the SF–CoCoSo method has only a limited impact on the relative attractiveness of the smart airport development plans in this case. The preferred alternative is not an artifact of a specific calibration of , and the stability of the ranking with respect to confirms that the aggregation procedure is numerically well behaved. Taken together with the analysis for , the sensitivity results indicate that the proposed framework yields reliable, robust, and consistent recommendations across a wide range of plausible parameter settings.

6.2. Ablation Analysis

To further demonstrate the effectiveness and necessity of the individual components of the proposed framework, an ablation analysis is conducted. In the proposed method, the social trust network is combined with the entropy measure to determine the experts’ weights, where the subjective weights are obtained from the social trust structure, and the objective weights are derived from the dispersion of the experts’ evaluations. In addition, the SF–CRITIC method and the SF–SWARA method are integrated to calculate the criterion weights, with SF–CRITIC providing objective weights and SF–SWARA providing subjective weights. In the ablation analysis, selected components of this architecture are removed or simplified, and the resulting changes in the ranking of smart airport development alternatives are examined. Six ablation scenarios are considered and compared with the original setting. The corresponding utility values and rankings are summarized in Table 15 and illustrated in Figure 5.

Table 15.

Evaluation results under different ablation settings.

Figure 5.

Evaluation results under different ablation settings.

The first three scenarios focus on the expert weighting mechanism. When the social trust network is removed and only entropy-based objective weights are used, or when the entropy measure is removed and experts are weighted only by the trust network, the ranking pattern exhibits only moderate changes relative to the original setting. In particular, remains the best alternative in all three cases, and the top few positions are preserved with only local swaps among neighboring alternatives. The variant without any expert weight calculation, where all experts are treated as equally important, yields utility values and rankings that are very close to those obtained under the full expert weighting scheme. These results indicate that the social trust model and the entropy measure primarily refine the contribution of individual experts and slightly adjust the ordering of mid-ranked plans, but they do not affect the identification of the leading strategy.

The next two scenarios isolate the impact of the criterion weighting components. When SF–CRITIC is removed and the criterion weights are determined solely by SF–SWARA, the ranking becomes more strongly aligned with the subjective importance assessments of the experts. In this case, alternatives that perform well on subjectively dominant criteria, such as and , gain relative advantage, and the utilities of mid-ranked alternatives change more markedly. Conversely, when SF–SWARA is removed and only SF–CRITIC is used, the weights reflect purely data-driven contrast and correlation information. This leads to noticeable shifts, for example, the substantial improvement in from a mid-ranked position in the original setting to the second place, while moves downwards. These patterns confirm that SF–CRITIC and SF–SWARA capture complementary aspects of criterion importance and that using only one of them can bias the evaluation toward either statistical variability or perceived strategic relevance.

In the scenario without criterion weight calculation, all criteria are assigned equal importance. The resulting ranking remains similar to the original one, and is still identified as the best alternative. However, the changes in the positions of alternatives such as , , and indicate that equal weighting reduces the ability of the model to reflect the differentiated influence of the criteria and leads to less nuanced discrimination among competing plans. Compared with the original configuration, the hybrid SF–CRITIC and SF–SWARA scheme yields more informative weights that better separate high-performing and low-performing alternatives while preserving the same top-ranked strategy.

Overall, the ablation analysis shows that the full integration of social trust and entropy-based expert weighting with the hybrid SF–CRITIC and SF–SWARA criterion weighting and the SF–CoCoSo ranking procedure produces the most consistent and well-differentiated evaluation. Across all ablation scenarios, remains the preferred smart airport development plan, which corroborates the robustness of the main decision recommendation. At the same time, simplifying or omitting components, particularly in the criterion weighting stage, tends to weaken the discriminatory power of the framework and alter the ordering of mid-ranked alternatives. These observations confirm that the integrated design of the proposed method is important for obtaining stable, interpretable, and practically meaningful decision support in smart airport development problems.

6.3. Comparative Analysis

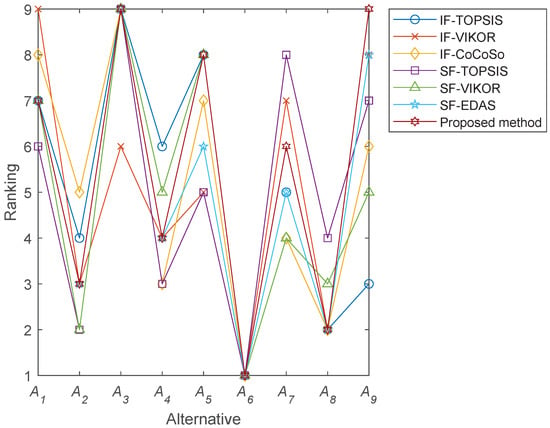

To further validate the proposed method, its ranking results are compared with those obtained from several alternative multi-criteria decision-making approaches. The comparative methods include spherical fuzzy TOPSIS, spherical fuzzy VIKOR, spherical fuzzy EDAS, intuitionistic fuzzy TOPSIS, intuitionistic fuzzy VIKOR, and intuitionistic fuzzy CoCoSo. The ranking orders produced by all methods are summarized in Table 16, and their profiles are illustrated in Figure 6.

Table 16.

Comparison results.

Figure 6.

Comparative analysis results.

From Table 16, it can be observed that all comparative methods identify as the best smart airport development alternative. This unanimous choice of provides strong evidence for the reliability of the ranking produced by the proposed SF–CoCoSo-based framework. At the same time, the ranking positions of some mid-level alternatives, such as , , , , and , differ across methods. These differences are expected because the methods rely on distinct fuzzy representations and different aggregation principles, which lead to nuanced changes in the relative appraisal of alternatives with similar performance profiles.

The empirical comparison also clarifies the specific contribution of the SF–CoCoSo component within the proposed framework. The ranking obtained by the SF–CoCoSo method shows a clear separation between leading alternatives, in particular and , and trailing ones while remaining broadly consistent with the overall preference structure of the benchmark methods. In this sense, the SF–CoCoSo procedure is not in conflict with established MCDM approaches but refines their outcomes by providing stronger discrimination among alternatives that would otherwise cluster closely in the middle of the ranking.

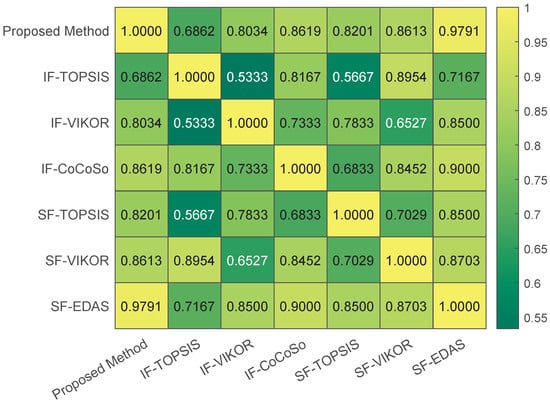

In order to quantify the agreement between the proposed method and the comparative approaches, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients are computed. The resulting coefficients between the proposed SF–CoCoSo-based framework and the six benchmark methods are , as shown in Figure 7. All coefficients are positive and mostly close to , which indicates a moderate to strong positive association between the ranking orders. In particular, the very high correlation with spherical fuzzy EDAS suggests that the SF-based distance and deviation-type evaluations produce largely compatible preference structures. These results further confirm that the proposed method yields ranking patterns that are consistent with existing techniques while providing additional resolution among competing plans.

Figure 7.

Spearman rank correlation coefficients of different methods.

On the basis of the comparative analysis, several advantages of the proposed method can be summarized as follows.

(1) Similarly to SF–TOPSIS, SF–VIKOR, and SF–EDAS, the proposed method is formulated in the spherical fuzzy environment. Compared with other fuzzy sets such as intuitionistic and Pythagorean fuzzy sets, spherical fuzzy sets explicitly consider positive, neutral, and negative membership degrees under the constraint , which enables a richer and more flexible characterization of epistemic uncertainty. This allows decision-makers to express their evaluations with higher flexibility and accuracy, thereby enhancing the reliability of the resulting rankings.

(2) The proposed method employs a comprehensive expert weighting scheme that integrates a social trust network with an entropy-based measure. The social trust network captures subjective credibility relationships among experts, whereas the entropy measure reflects the informational content and dispersion of their evaluations. By combining these two components, the method derives expert weights that simultaneously account for interpersonal trust and data quality, which improves the robustness of the aggregated group assessments relative to schemes based solely on equal weights or single-factor weighting.

(3) The proposed method adopts an integrated criterion weighting mechanism that combines SF–CRITIC and SF–SWARA. The SF–CRITIC part provides objective weights by exploiting the contrast intensity and correlation among criteria based on spherical fuzzy scores, while the SF–SWARA part derives subjective weights from ordered expert judgments of importance. The resulting combined weights balance data-driven and judgment-driven information, which, as shown in the sensitivity and ablation analyses, leads to a more reliable and robust prioritization of criteria than when using either component alone or assuming equal importance.

(4) In the ranking stage, the CoCoSo method is extended with spherical fuzzy sets to form the SF–CoCoSo procedure. Three appraisal scores corresponding to different aggregation strategies are first obtained and then synthesized into an overall utility value for each alternative. This design jointly captures additive and multiplicative performance effects and ensures that the top-ranked alternative performs well across multiple appraisal perspectives rather than excelling in only a single index. The comparative results demonstrate that, under this scheme, the proposed method yields reliable, reasonable, and robust rankings, with consistently identified as the most attractive smart airport development strategy across all comparative methods and analyses.

6.4. Discussion

This study develops a comprehensive framework for evaluating smart airport development plans under uncertainty based on an integrated spherical fuzzy multi-criteria decision-making approach. By jointly incorporating expert weighting, criterion weighting, and an advanced ranking procedure within a unified model, the framework addresses the complexity and ambiguity inherent in large-scale airport planning decisions. The empirical results from the case study provide insights into the underlying performance patterns of the alternatives and offer answers to the research questions posed in this work.

The dominance of in the final ranking, together with the strong performance of alternatives such as and , can be explained by their behavior with respect to the most influential criteria. The combined SF–CRITIC and SF–SWARA weights indicate that a small subset of criteria, primarily related to technological integration, safety and security, and passenger experience, plays a leading role in the evaluation, since these criteria receive substantially larger weights than the others. Alternative attains high spherical fuzzy evaluations on all of these key criteria and avoids very low evaluations on the remaining ones, which results in the highest overall appraisal score. Alternative performs similarly well on most of the highly weighted criteria and even slightly better than on some forward-looking, innovation-oriented aspects, but it is penalized by weaker scores on criteria associated with resource requirements and implementation risks, which leads to a lower composite score. Alternatives such as and also achieve favorable scores on several high-weight criteria, especially those linked to environmental performance and operational efficiency, which explains their positions among the top-ranked plans.

By contrast, mid-ranked plans typically display mixed profiles. Some alternatives exhibit excellent performance on a few criteria but show clear disadvantages on other criteria that still carry non-negligible weights, which results in only moderate composite scores. Low-ranked plans are generally characterized by consistently lower evaluations on both core and supporting criteria. Hence, the superiority of and other top-ranked alternatives is not arbitrary but driven by their alignment with the most important dimensions of smart airport development as encoded in the combined weighting scheme and captured in the spherical fuzzy evaluations.

RQ1: What are the factors that influence the evaluation and selection of smart airport development plans?