Abstract

This systematic search with narrative synthesis examines metaverse business models and their shift toward immersive virtual ecosystems. Following the PRISMA flow for identification and screening to structure transparency, we review 91 publications to map the shift from classical and digital models to metaverse models, highlighting new value propositions, revenue mechanisms, and the integration of VR, AR, and blockchain across the value chain. Our contributions are threefold: we articulate the transition patterns from classical and digital to metaverse business models; we propose a structured metaverse business framework with evaluation dimensions; and we compile a candidate metric set to support comparative analysis. Interpreting the evidence through a socio-technical systems lens, the synthesis indicates an emergent shift in how value is created, delivered, and captured. We identify five core dimensions for assessing metaverse business models: scalability, technological adaptability, user engagement and retention, ethical and sustainability practices, and economic viability as critical dimensions for future comparative analysis of metaverse business models. Building on these findings, we propose a metaverse business framework and a set of candidate KPIs to enable comparative evaluation and guide investment, design, and governance. The paper advances digital transformation theory and outlines a research agenda on dynamic capabilities and the long-term sustainability of metaverse business models.

1. Introduction

A business model outlines how a company creates, delivers, and captures value, essentially showing how it operates and makes money. It includes the company’s value proposition, revenue streams, customer segments, channels, and cost structure. Shafer et al. [1] view business models as representing a firm’s core logic and strategic choices for creating and capturing value within a value network. Mitchell and Bruckner Coles [2] use a set of guiding questions to describe a business model, focusing on the who, what, when, where why, to whom, how, and how much of an organization’s operations. According to Olofsson & Farr [3], a business model is an architectural layer between planning and implementation. Furthermore, Osterwalder [4] places a business model at the center of a triangle comprising business strategy, organization, and ICT, within a legal and social environment characterized by customer demand, competitive forces, and technological change, emphasizing the role of both internal and external factors. They propose nine building blocks of a business model: value proposition, target customer, distribution channel, relationship, value configuration, capability, partnership, cost structure, and revenue model. On the other hand, Gassmann et al. [5] propose a simplified approach through a business model ‘magic triangle’, guided by four questions: (1) what do you offer to the customer? (2) how is the value proposition created; (3) who is your target customer; and (4) how is revenue created; or simplified ‘Who-What-How-Value?’, creating a framework that is simple and convenient for both scientific and practical analysis.

The classical business model typically revolves around a linear value chain, where products or services flow from production to the end consumer through a series of well-defined steps: value creation, value proposition, value delivery, and value capture. This model emphasizes physical products, services, and direct interactions in a physical or digital space, but within the confines of traditional platforms and media. On the other hand, a business framework provides a structured approach for analyzing, understanding, and making decisions about a business. It can include theories, methodologies, and tools for assessing business operations, strategy, and growth opportunities.

For illustration, a classic business model example is the retail business model, where a company buys products at wholesale prices and sells them to end consumers at retail prices. Such a model relies on purchasing inventory, marking up prices to cover costs and generate profits, and selling through physical or online stores. The value is created by providing consumers with convenient access to various products, and the company captures value through the margin between the wholesale and retail prices. Transferring a classical retail business model to the Metaverse could involve creating virtual storefronts in a digital world where consumers can interact with products in a 3D space. This model might leverage virtual reality (VR) to enhance customer experience, allowing them to “try” products virtually. The value proposition shifts towards immersive shopping experiences, with value captured through digital transactions. Revenue could come from virtual goods sales, in-world advertising, and premium experiences. To support this model, the business would need to innovate in digital inventory management, VR technology, data processing, and cybersecurity.

The main difference between a classical business model and a metaverse business model lies in the scope and dimensionality of interactions and transactions, including the platform and interaction method. The metaverse business model is positioned at an advanced stage of digital transformation, where digitalization has significantly matured within a company’s operations. The transition from a classical to a digital and then to a metaverse business model can be viewed as a digital maturity continuum. A digital business model integrates digital technology into all aspects of business operations, enhancing efficiency and customer experience and creating new value propositions through digital means [6]. The main difference between digital and metaverse business models lies in their level of immersion and interactivity. Digital business models leverage the internet and digital technologies to sell products or services, prioritizing efficiency and reach. Metaverse business models, however, offer immersive, 3D virtual environments where users can interact with the digital world and one another in more complex and engaging ways. Prior peer-reviewed scholarship has synthesized how pre-blockchain virtual worlds functioned as economies, including user-generated content markets, virtual goods monetization, and governance arrangements that anticipate many metaverse logics [7]. Nowadays, the metaverse business model takes digital transformation further by leveraging immersive virtual environments, refining the potential of Industry 5.0 [8], marketing innovation [9], and disrupting the current notion of business process execution [10]. This means that the metaverse business models can be observed as the latest stage of digital transformation, as a temporary hype, or-if key conditions are realized (e.g., interoperability, robust governance, and widespread adoption)-as an onset of a new paradigm that might surpass the digital transformation as we currently understand it. The rationale is that the Metaverse entails not just a technological shift but a holistic integration of digital and physical realities, offering higher levels of engagement, interaction, and immersion, which translate into potential for innovative products and services, novel transactional forms, and new modes of value creation and capture. This surpasses traditional digital transformation, which has primarily focused on digitizing existing processes rather than creating entirely new socio-technical realities.

Whereas classical models are constrained by physical and digital boundaries of the current internet and economic systems, metaverse models operate in a platform-mediated, increasingly immersive virtual ecosystem that integrates social, financial, and experiential aspects deeply intertwined with digital currencies and non-fungible tokens (NFTs), enabling a new economy based on virtual goods and services. Metaverse models offer specific digital experiences, virtual goods, services, virtual spaces, assets, and experiences that can transcend what is possible in the physical world. The value proposition becomes significantly enhanced, offering users not just products or services but experiences and identities within a virtual world. Value delivery leverages virtual platforms, requiring robust digital infrastructure to support immersive experiences. Finally, value capture can include new forms, such as transactions in virtual currencies, the trade of virtual goods, and the monetization of virtual real estate and experiences. This shift enables innovative and enhanced customer engagement, as well as new revenue streams from virtual experiences, while also requiring adaptations in value delivery, such as the utilization of virtual reality technologies. Consequently, metaverse business models should be analyzed not only as technological innovations but also as complex, adaptive systems integrating technological, economic, social, and ethical dimensions.

However, the current business environment supports various business models operating at different levels of digital transformation. Gil-Cordero et al. [11] examine the factors influencing small and medium-sized enterprises’ (SMEs’) intentions to adopt the Metaverse, focusing on effort expectancy, performance expectancy, and business satisfaction. They found that business satisfaction, which involves obtaining information, reducing uncertainty, and analyzing competition, plays a critical role in SMEs’ approach to the Metaverse. Utilizing the Metaverse in any form, particularly the transition to a metaverse business model, requires a substantial technological infrastructure and investment. Therefore, the companies that existed before the metaverse era could be reluctant to make the leap, especially if they lack information or perceive the environment as uncertain. Recent case-based evidence highlights that successful Metaverse moves hinge on building and integrating digital-asset and organizational capabilities through organizational change and innovation ecosystems. Leadership typically follows a staged roadmap from exploration to experimentation to consolidation [12]. Since the Metaverse is still in its early stages, with many unknowns, further research is necessary to gain a deeper understanding.

Polyviou & Pappas [13] explore the concept of Metaverses as immersive virtual worlds that simulate the physical world, where digital representations of people, places, and things (e.g., avatars) can interact and collaborate. Their paper emphasizes the transformative potential of metaverses for businesses and society. It proposes a methodological framework for future researchers to organize the literature on Metaverses and guide them in identifying new research avenues, particularly regarding how Metaverses can reshape business strategies, operations, policies, and structures, focusing on dimensions such as design, strategy, management, and value measurement. As a promising avenue for future research, Gursoy et al. [14] propose research on economic and business models in the Metaverse.

At this point, we need to add a note on the terminology-we use “Metaverse” (capitalized) when referring to the overarching socio-technical vision and ecosystem, and we use “metaverse” (lowercase) when used adjectivally or to denote specific implementations (e.g., metaverse business models, metaverse platforms).

In the rest of the paper, we examine a business model in the Metaverse, focusing on the unique aspects of metaverse business models, including their core elements, such as innovative revenue streams and value propositions. Further, we examine how metaverse models navigate technological advancements, legal frameworks, cybersecurity, data privacy, and sustainability challenges. Additionally, the role of cutting-edge technologies and analytical tools in shaping these business models, the significance of user engagement, and strategic considerations for businesses entering the Metaverse will be explored, alongside the potential diffusion of metaverse technologies across industries.

The next section describes the methods used and precedes Results and Discussion, which are divided into subsections for easier systematization. Starting from its beginnings, we introduce the early stages of the metaverse adoption, progressing to a discussion of the metaverse business model and issues surrounding its application. The Results and Discussion section concludes with a proposal of the metaverse business framework. The Conclusion summarizes theoretical and managerial implications, along with limitations and proposals for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

The initial analysis and reporting follow the PRISMA guidelines [15,16], with the topic serving as the basis for the inclusion criteria. The PRISMA checklist is available in Appendix A (we use selected PRISMA 2020 reporting items appropriate for a narrative review to structure transparency, as we did not conduct a meta-analysis or a full PRISMA systematic review). The search comprises a business model or business framework in combination with the Metaverse. The search for the documents in the WoSCC and Scopus by keywords, abstract, and title using the respective search engines was conducted on 6 February 2024. The exact search string was TITLE-ABS-KEY (metaverse AND (“business model” OR “business framework”)) for Scopus (Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), and TS = (metaverse AND (“business model” OR “business framework”)) for Web of Science Core Collection (Clarivate, Philadelphia, PA, USA). All languages, timespan, and document types were included in the search. This also includes online first and early access indexed publications. Records were exported (BibTeX), merged, and deduplicated in R using bibliometrix package [17].

While the restriction of using only these two archives may have resulted in the omission of some relevant studies not indexed in these databases, the use of WoSCC and Scopus ensures that the included literature is subject to rigorous indexing standards and reflects a verified level of scholarly quality. This choice also enhances transparency and replicability of the review process, as the search strategy can be systematically reproduced using the same databases and criteria. The fixed search date (6 February 2024) likewise restricts our evidence to that point in time, and subsequent publications fall outside scope but can be incorporated in the updates.

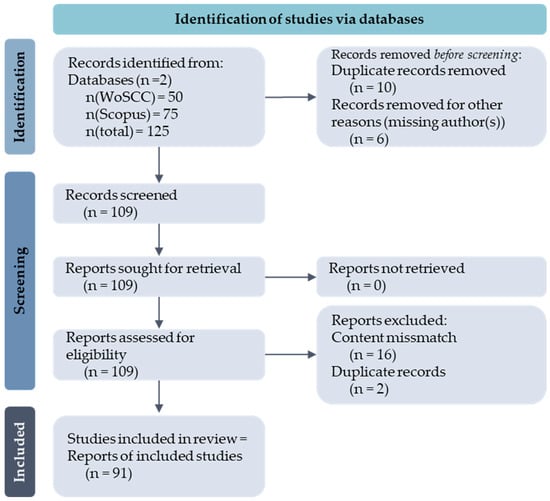

Figure 1 details the PRISMA flow (we applied selected PRISMA items to document search and screening): 125 records retrieved (50 WoSCC, 75 Scopus), 16 removed (duplicates, missing authors), 109 screened, 18 excluded for content mismatch and manually discovered duplicates (Appendix B, Table A2 and Table A3), leaving 91 for synthesis.

Figure 1.

PRISMA-style flow diagram. Source: Authors.

The inclusion criteria involved the selection of peer-reviewed and indexed scholarly outputs that explicitly discuss business models/frameworks in relation to the metaverse, and provide conceptual, methodological, or applicative content relevant to value propositions, value chains, or revenue mechanisms. In addition, borderline papers were included if they explicitly link at least one business model element (value proposition, value chain, revenue) to metaverse contexts, or may serve as a relevant example, even when the full canvas was not presented (Appendix B, Table A4). Items lacking a metaverse–business–model link, non-scholarly sources, editorials/notes (unless containing substantive model content), or records with missing essential metadata (e.g., authors) are excluded.

Both authors independently screened all records (titles/abstracts and full text). Disagreements at any stage were resolved through discussion until a consensus was reached; no third reviewer was required.

At the beginning of our analysis, in the screening stage, we employed bibliometric analysis to gain initial insights (Table 1). Bibliometric analysis relies on the statistical exploration of scientific activities, offering a method that enhances transparency and reproducibility compared to other review types, thereby ensuring more objective and reliable outcomes [17]. In this case, it offers valuable quantitative initial insights into topic popularity and academic relevance.

Table 1.

Main information about documents.

The main information about the examined documents reveals a short period, with 109 documents and a 13.88% annual growth rate. The documents comprise 63 journal articles, 10 book chapters, 2 books, 24 conference papers, 9 reviews, and a note. Only 109 publications were published by 95 sources, which indicates that there is no specific outlet for this line of research. In addition, 3028 identified references suggest that researchers in this area draw from other fields.

Regarding topic development, the first paper, a case study, was written in 2008. That shows that science lagged behind the developments in practice and joined in to observe the new patterns. Another paper was published in 2010, followed by a break until one paper was published in 2018. Following this, a surge in research publications on the topic began in 2022, with 20 publications, 78 documents in 2023, and 8 publications in the first month of 2024. This also indicates that the actual annual growth rate is even higher, as excluding the papers prior to and including 2018 (3 papers) yields a 36.75% yearly growth rate. These figures indicate topic popularity rather than evidentiary strength. Our synthesis therefore emphasizes convergent constructs across sources, while acknowledging potential temporal bias.

While bibliometric analysis provides valuable first insights into publication patterns and research trends, it is not appropriate for deriving an in-depth conceptual understanding of business model dynamics in the Metaverse. To achieve this, we complement the bibliometric overview with a narrative synthesis, enabling us to systematize and critically interpret the conceptual and theoretical underpinnings of the field [18].

No meta-analysis was planned or conducted due to heterogeneity, so this is not a full PRISMA systematic review. In addition, quantitative synthesis, GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation), and RoB (Risk of Bias) tools are not appropriate for a predominantly conceptual or heterogeneous evidence. Because the corpus combines conceptual and empirical work, we applied a minimal design-appropriate appraisal. For the conceptual/theoretical papers, clarity of constructs, coherence of logic, and novelty/utility were considered. For the empirical research and case studies, clarity of design, data adequacy, and analytic transparency were the guidelines for the paper quality. While quality was not an exclusion criterion, it governed the selection of the papers that served as the main arguments in the narrative. Book chapters and proceedings papers were included as they are parts of indexed publications (which requires a peer review), and they were used for additional arguments or observations, not as core evidence for framework construction.

We employed a structured narrative synthesis, comprising five steps: first, initial mapping (scoping the literature); second, cross-case contrasts; third, grouping themes around Gassmann’s Who-What-How-Value framework; fourth, identifying emerging issues; and fifth, construction of the layered framework (without statistical pooling or formal qualitative coding) [19,20].

The 91 identified documents have been reviewed, and their findings are synthesized through a narrative review. This highlights the evolution of thought and evidence on metaverse business models. The sheer volume of publications in such a short period underscores the Metaverse’s transformative potential in reshaping business strategies, value propositions, value chains, and revenue models that require thorough insights.

In the rest of the paper, we strive to systematically address several pivotal questions relevant to understanding and navigating the emerging metaverse landscape from a business model perspective:

- What are the main elements of the Metaverse business models, as well as the potential revenue models and value propositions unique to the Metaverse?

- How does the metaverse business model address technological, legal, cybersecurity, data privacy, and sustainability issues?

- What innovative technological and analytical applications play a role in metaverse business models?

- How do user engagement and experiences shape the metaverse business landscape?

- What are the strategic and operational considerations for businesses entering the Metaverse?

- How can metaverse technologies transform various sectors?

For traceability, our six guiding questions map to specific outputs as follows:

- Q1 (core elements, value propositions, revenue models) → Section 3.2 and Table 2;

- Q2 (technological, legal, cybersecurity, privacy, sustainability) → Section 3.3.1, Section 3.3.2 and Section 3.3.3;

- Q3 (innovative technological and analytical applications) → Section 3.2.2 and Section 3.3.3;

- Q4 (user engagement and experiences) → Section 3.2.1 and Section 3.3.4;

- Q5 (strategic and operational considerations) → Section 3.2 and Section 3.3.6 (framework);

- Q6 (sectoral diffusion) → Section 3.3.5 (applications and examples);

- PRISMA items and screening details → Appendix A; excluded/borderline records → Appendix B.

In this narrative systematization, we explore and elucidate the emergent topics within the selected articles, focusing on how these topics have evolved. Our approach was grounded in a comprehensive reading and interpretative analysis of the content rather than employing numerical analysis, counting, or formal coding strategies commonly found in other types of systematic reviews or meta-analyses. This process enabled us to immerse ourselves in the material, gaining a profound understanding of the thematic outlook and its development throughout the literature.

We explore the metaverse business models through predefined lenses of Gassmann et al.’s [5] elements. Given the raised questions, we further explore intertwined areas by systematically sifting through the content, identifying key themes, patterns, and shifts in discourse without quantifying their occurrence. This method facilitated a nuanced synthesis of the literature, highlighting significant trends, topics, and research gaps. Our analysis was iterative, with continuous refinement of themes as we delved deeper into the articles. This approach enabled us to trace the development of topics over time, understanding their contextual relevance and implications for the field, and maintaining the exploratory and interpretative nature of the analysis.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Beginnings

As the first document to address the intersection of Metaverse and business systems, the book “Interdisciplinary Aspects of Information Systems Studies” by [21] features a chapter by Cagnina & Poian [22] that explores a metaverse business model through a case study of Second Life. The article presents a comprehensive analysis of how new (at the time) web-based technologies, particularly focusing on Second Life, impact e-business practices, proposing a theoretical framework to understand the business possibilities within Web 2.0 platforms.

The form of the metaverse business model, as illustrated using Second Life, combines technological advancements with user engagement to create a unique, immersive experience. The framework identifies technology as the set of structural conditions defining digital interactions and content creation as the manipulation of technology by users to satisfy their needs. This includes the development of three-dimensional structures and items by users, blurring the lines between firms and customers.

Interactivity and immersion are the main analytical dimensions. Interactivity encompasses the processes established between users, hardware, and software, influencing learning and skill acquisition. Immersion refers to the level of involvement and motivation experienced by users, which enhances telepresence and positively impacts brand attitudes. The model underlines the importance of engaging users and fostering a strong sense of community among prosumers (users who both produce and consume). This leads to collective environment enactment, where users contribute to building and improving the virtual world.

There is also an economic aspect; Second Life introduces an economic system with an official currency, the Linden Dollar, that can be exchanged for US dollars, allowing residents to generate real-world income from their creations within the virtual world. Acknowledged legal issues refer to recognizing residents’ intellectual property rights to their creations as a fundamental element. This aspect encourages innovation and creativity by ensuring users retain ownership over their digital creations. Successful virtual business strategies in Second Life include engagement campaigns and leveraging the community of prosumers for creative input, as exemplified by the marketing efforts of “Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix” and Coca-Cola’s Virtual Thirst competition. Overall, this model emphasizes the integration of web-based features with distinctive aspects of the Metaverse, leading to the creation of communities of prosumers.

Similarly, the alpha.tribe [23] was an experimental group that functioned as a collective to operate the virtual fashion business in Second Life. This collective approach allowed for a diverse range of creative inputs and explorations. The author’s approach was primarily self-observational, suggesting that the enterprise’s design and operation were closely monitored and reflected upon by the creator(s). This introspective method likely informs adjustments and evolutions in the business strategy and creative direction. However, the enterprise and its creative processes are documented visually, which not only serves as evidence of the work performed but also as a means to engage with audiences and consumers. While Second Life illuminates early prosumer logics, its firm-hosted, non-interoperable architecture limits direct generalization to today’s tokenized and AI-augmented ecosystems.

Uddin et al. [24] pinpoint the origins of the Metaverse to the birth of the Internet, emphasizing the role of technology. They view Metaverse as an inseparable combination of virtual and physical systems that enable immersive user experience, serve as the interface for content creation, and foster further technological development at their intersection.

While these papers suggest the development of a new phenomenon, Ioannidis & Kontis [25] disagree. Through their research, they outline the historical development of the Metaverse, beginning with early 20th-century fiction that introduced concepts of virtual realities, and progressing through technological advancements such as VR headsets and online virtual worlds, to modern interpretations and implementations, including digital twins and blockchain technologies. They highlight key milestones and technologies that have shaped the Metaverse concept over time, suggesting an ongoing evolution towards more integrated, realistic, and interactive virtual environments. The Metaverse’s potential for social interaction, entertainment, work, and education is emphasized alongside the technological and conceptual challenges that remain in realizing its complete vision. However, the realization of its business potential is a more recent subject that requires a deeper insight.

3.2. Theoretical Background of the Metaverse Business Model

We adopt a systems lens consistent with socio-technical systems theory, treating business models as adaptive configurations of technologies, organizations, and institutions. We therefore read existing proposals as co-evolving socio-technical configurations, where technological affordances, organizational routines, market logics, and regulatory constraints adapt jointly. The following studies illustrate various socio-technical pathways through which the metaverse business model is conceptualized, highlighting the multi-layered nature of this evolving ecosystem.

From a business perspective, the Metaverse is still in its infancy, with much of its potential revenue generation and value chain yet to be fully realized [26]. The book paints the Metaverse as a burgeoning digital realm, powered by advancements in virtual and augmented reality, aiming to transition from a 2D to a 3D online experience. This transition is accompanied by the tokenization of a broad range of digital assets, suggesting a future where digital and virtual assets play a central role in the economy. The Metaverse is envisioned as a network of persistent, interoperable virtual worlds. Its development, significantly boosted by the COVID-19 pandemic, suggests a future where digital interactions could closely mimic or even enhance real-world interactions. This has vast implications for commerce, education, healthcare, and other sectors, extending into areas such as property tokenization and the creation of digital twins for real-world assets. This broad perspective sets the stage for more targeted frameworks that emphasize strategic alignment, ethics, or sector-specific transformations.

While primarily dealing with the Mechanics-Dynamics-Aesthetics (MDA) game design approach, Bockle et al. [27] propose a framework that encourages a systematic approach to designing metaverse environments, focusing on why the Metaverse adds value, what design elements are needed, and how to apply strategic design principles effectively. While Bockle et al. [27] argue that metaverse initiatives must align design choices with explicit business objectives across consumer, industrial, and enterprise contexts, Anshari et al. [28] extend this logic to the ethical domain, emphasizing that sustainability and trust are not add-ons but integral components of long-term value creation.

3.2.1. Innovations and User Experience

An innovative e-commerce platform that integrates live commerce with the Metaverse, using digital twin technology, is proposed by Jeong et al. [29]. This type of business model aims to enhance the online shopping experience by allowing consumers to interact with products and brands in a virtual space, overcoming the limitations of traditional live commerce. It emphasizes creating engaging content and virtual brand experiences to attract and retain customers. The business model is detailed through the Business Model Canvas, highlighting its unique value proposition and the essential components required for success.

Gursoy et al. [14] outline a comprehensive framework for delivering enhanced virtual reality experiences within the Metaverse, focusing on multi-view content synthesis and efficient content delivery mechanisms. Particularly, they highlight experience and purchase co-creation through the participation of the focal customer. They emphasize immersive user experiences, resource optimization, and potential monetization strategies through unique digital offerings, aligning with broader Metaverse development and engagement strategies. Both contributions [14,29] show how immersive design and technological infrastructure combine to enhance customer experience, whether through retail interactions or multi-view content ecosystems.

Mancuso, Petruzzelli et al. [30] further develop the idea of mechanisms, exploring individual microfoundations (skills and actions of individuals) and relational microfoundations (relationships among individuals) that underpin value creation and capture. These microfoundations explain macro variables that affect innovation in value creation and value capture within the business model innovation. While this underlines how resilience and innovation capacity depend not only on technological adoption but also on microfoundations—skills, routines, and relationships that sustain transformation —it also touches upon the co-creation aspect, which further raises questions about authorship/ownership, tokenization, and the development of virtual economies and crypto economies.

Lastly, not all strategies will be successful, so it is relevant to explore recovery strategies. While addressing the issue of recovery strategies, Mir et al. [31] also consider Metaverse and synthetic services (AI-/avatar-mediated service interactions). The opportunities and challenges of service recovery in the Metaverse need effective strategies to manage service failures in virtual hospitality experiences. They highlight the integration of virtual and real-world services by firms such as McDonald’s and Starbucks, suggesting novel avenues for compensating for service failures across these realms. The Proteus effect refers to the phenomenon where an individual’s behavior in the virtual world, influenced by their digital avatar’s appearance and capabilities, affects their behavior and attitudes in the real world. These cases illustrate service failure and recovery in avatar-mediated contexts and invite the application of attribution and justice theories to virtual settings (e.g., how avatar appearance shapes blame and fairness), yielding design implications for resilient value propositions.

3.2.2. Performance, Productivity, and Optimization

In the realm of engineering management, the Metaverse has the potential to be transformative, enhancing productivity, fostering new business models, and increasing organizational competitiveness. The discussion is structured around five key areas: supply chain management, logistics management, decision-making, technology management, and knowledge management [32]. In terms of business models, the Metaverse is seen as a fertile ground for innovation. It presents opportunities for creating new revenue streams through the development of virtual products and services. Organizations can leverage the Metaverse to design immersive experiences, facilitating novel ways of interaction, collaboration, and transaction. The Metaverse’s impact is discussed in relation to enhancing supply chain visibility, improving logistics operations, and enabling more efficient and informed decision-making processes.

El Jaouhari et al. [33] highlight the lack of integrated approaches to combining metaverse technologies and manufacturing resilience, especially during disruptions such as COVID-19. They suggest further research into metaverse applications in manufacturing to leverage their full potential. This study offers a conceptual framework but calls for empirical research to validate the proposed benefits and applications of metaverse technologies in manufacturing settings. The potential avenue lies in extending ‘phygital’ transformation [34] to the production process (tightly coupled combinations of physical processes and digital interactions).

Mancuso et al. [34] examine how digital business model innovation within the Metaverse can approach virtual economy opportunities, highlighting new value creation and capture mechanisms emerging from metaverse opportunities. They categorize these opportunities around internal processes and customers, focusing on ‘phygital’ transformations that blend physical and digital realities, as well as virtual transformations that enhance customer engagement through digital identities and communities.

Another venue is a multi-dimensional optimization framework for microservices [35] in the context of cloud-native and metaverse scenarios, focusing on security mechanisms, high concurrency testing, and system reliability. The author proposes a model to enhance service maturity by addressing development, testing, deployment, and operational challenges, demonstrating that the technological and analytical frameworks are inseparable from the business model. It aims to optimize the service lifecycle, from development to online operation, with specific strategies for code quality, stress testing, service deployment, and system protection. Additionally, it introduces automated quality checks to maintain long-term service maturity, with experimental results indicating improvements in system performance and reliability.

3.2.3. Supply Chain

Siahaan et al. [36] examine logistics development in relation to technology trends and enabling factors in the Metaverse, building on the Malcolm Baldrige’s Performance System Model. Positioning logistics as a metaverse value proposition reveals new services (tracking, virtual fulfillment) and cyber-physical transparency across the chain. These services could transform how goods are managed, tracked, and delivered within digital environments, enhancing customer experiences. This could redefine operations and processes, including supply chain management (SCM), by leveraging digital platforms and cyber-physical systems for more efficient and transparent logistics operations. As logistics evolve to meet the needs of the Metaverse, new revenue models may emerge. For instance, companies could generate income through virtual logistics services, facilitating trade within the Metaverse, or managing the supply chain of virtual goods, possibly using cryptocurrencies or other digital payment methods.

Another line of work on metaverse integration in SCM identifies key barriers to its implementation, including technological limitations, lack of governance, integration challenges, and resistance due to traditional organizational culture [37]. Addressing these barriers is a prerequisite for businesses looking to leverage the Metaverse for enhanced SCM efficiency, and authors stress the importance of technological readiness, governance standards, strategic planning for technology integration, and an innovation-oriented culture to adopt metaverse technology in supply chain management practices successfully. These works [32,36,37,38] shift the focus from customer-facing innovation to the back-end of metaverse infrastructures, exploring decentralization, supply chain, and logistics issues. Read through a systems lens, these works foreground feedback loops (e.g., demand-capacity-latency) and endogenize coordination costs and trust formation.

3.2.4. Virtual Economy and Financial Aspects

A creator crypto economy model for blockchain-enabled social media (BSM), focusing on decentralization and user engagement through innovative practices, was introduced by Zhan et al. [38]. They outline a business model based on four pillars: fundamental technologies, governance and operations, incentive mechanism design, and organizational structure and performance, aimed at overcoming the challenges of traditional social media by offering a more participatory and equitable framework. The model emphasizes the importance of blockchain technology in creating a secure, transparent, and user-centric platform.

Zadorozhnyi et al.’s [39] suggestions for improving accounting and auditing methodologies within the Metaverse align directly with enhancing a company’s value proposition by ensuring the reliability and legitimacy of virtual assets. The paper recommends improving the methodology and organization of accounting and auditing within the Metaverse, specifically for non-current intangible assets, IT company goodwill, NFTs, cryptocurrencies, and other virtual objects. They suggest classifying NFTs based on their usefulness into non-current and current assets for appropriate accounting reflections. This contributes to the value chain by enabling the precise classification and accounting of virtual goods and services, which can enhance revenue models through the accurate tracking of sales and investments in virtual environments, while also increasing transparency. The issue of accounting and taxation has also been investigated by Pandey & Gilmour [40], who find that transactions in the Metaverse challenge traditional revenue recognition and deferral concepts due to the introduction of new applications powered by blockchain and emerging technologies, such as NFTs and decentralized finance (DeFi) tools. The authors emphasize the importance of a case-based approach for the accounting industry in the Metaverse, particularly in light of the current lack of standardized regulations. The emphasis on auditing, accounting, and taxation [39,40] illustrates that even fundamental economic functions must be reconfigured to accommodate virtual assets.

3.2.5. Ethical Considerations

Anshari et al. [28] propose a metaverse business model that emphasizes the ethical implications of data collection and utilization for sustainable business practices. Their research highlights the transformative potential of the Metaverse for businesses, including the ability to generate massive amounts of data for innovative value creation, while also pointing out the ethical considerations related to data ownership and privacy. The model suggests the involvement of various stakeholders, including academics, business professionals, and policymakers, in developing a framework of ethical compliance for metaverse applications. This involves understanding and acting to connect society, business, education, and the environment in response to the interests of all stakeholders. Their business model emphasizes the importance of ethical practices in promoting the social sustainability of an organization, based on the notion that ethical conduct can enhance organizational performance, reinforce brand capital, and generate value for shareholders, ultimately leading to long-term financial benefits.

This positions ethical governance as a capability, not a constraint—one that shapes data access, stakeholder trust, and ultimately determines monetization options.

3.2.6. User Adoption

User adoption is another issue. User adoption hinges on perceived opportunities versus social threats [41], reminding designers that behavioral dynamics co-determine value realization. While ‘immersive experience’ is one of the most commonly used terms to describe user engagement in the Metaverse and a proposed added value, Hennig-Thurau et al. [42] empirically examine the habituation effects on user interaction outcomes in virtual-reality Metaverse settings compared to 2D settings. Unlike other studies, they find that while the virtual-reality Metaverse initially enhances social presence and interaction, these benefits decrease over time as users become habituated to it. The paper provides a nuanced view of the Metaverse’s potential and limitations for real-time multisensory social interactions, suggesting that the Metaverse accessed via virtual-reality headsets, despite its immersive advantages, may not sustain its superior value creation without addressing habituation and other negative effects, such as reduced social presence over time due to habituation, and potential limitations in physical mobility and self-presentation due to avatar use. Hence, adoption is path-dependent: initial telepresence gains may decay through habituation, requiring design responses (such as novelty pacing and social affordances) to sustain perceived value.

3.2.7. Systematization of Findings Based on the Value Proposition, Value Chain, and Revenue Stream

Gassmann et al. operationalize the framework by placing the ‘Who’ (the target customer) at the absolute center of the model. The questions form the corners of the triangle-‘What?’ (is offered), ‘How?’ (is it created), and ‘Value?’ (how is revenue captured)-and the answers to these questions become the core components that fill the triangle: the Value Proposition, the Value Chain, and the Revenue Model, all of which are designed to serve the central ‘Who’ ([5]: p1-Figure 1). To enable cross-comparison, we map the reviewed contributions onto three canonical business-model dimensions-value proposition, value chain, and revenue streams-summarized in Table 2. Section 3.3 synthesizes the transitions in metaverse business models, while Section 3.3.1, Section 3.3.2, Section 3.3.3, Section 3.3.4 and Section 3.3.5 examine operational insights, and Section 3.3.6 operationalizes these insights into a metaverse business framework for evaluation and comparison.

Table 2.

Systematization based on Gassmann et al.’s [5] elements.

Table 2.

Systematization based on Gassmann et al.’s [5] elements.

| Paper | Value Proposition | Value Chain | Revenue Stream |

|---|---|---|---|

| [28] | the importance of ethical data use for value creation, suggesting that trust and sustainability are integral to the value offered by metaverse businesses | a collaborative approach involving multiple stakeholders to establish ethical standards, suggesting a value chain that is both inclusive and transparent | ethical practices are seen as a pathway to long-term financial benefits, reinforcing brand capital and value for shareholders, hinting at a revenue model that aligns ethical compliance with profitability |

| [29] | enhanced customer experience through a digital twin technology in e-commerce, where the value lies in the immersive and interactive engagement with products | integrating technology (like digital twins) and creative content production, aiming to bridge virtual and physical commerce | diverse revenue streams, including advertising, brokerage fees from sales, and design fees for metaverse space customization, showcasing a multifaceted revenue model leveraging the unique aspects of the Metaverse |

| [39] | improving accounting and auditing methodologies within the Metaverse | separating accounting of costs for selling tangible and intangible objects, enabling precise classification and accounting of virtual goods and services | non-current intangible assets, IT company goodwill, NFTs, cryptocurrencies, and other virtual objects |

| [37] | unique advantages and solutions the Metaverse offer to supply chain issues | understanding and overcoming barriers can streamline operations, enhance collaboration, and foster innovation across the supply chain, optimizing each link from procurement to delivery | not specified explicitly |

| [43] | digital ownership and play-to-earn models | enabling authentication and NFTs ownership transfer, improving supply chain transparency | NFTs open up new streams through direct sales, royalties, and exclusive access to content or events, appealing to digital and real-world assets and integrating with traditional and emerging markets |

| [27] | the business opportunity (the “why”) is crucial for defining the value proposition and potential revenue streams in the Metaverse context | the customers are seen as users of the Metaverse, ranging from individual consumers to enterprises seeking internal or operational improvements; creators are developers, designers, and businesses that build and maintain metaverse environments, guided by strategic objectives and design principles to create valuable and engaging virtual spaces | the creation process by integrating strategic design elements that enhance user experience and engagement |

| [44] | personalized, individualized guest experiences enabled by data analytics and ambient intelligence | re-engineered for collaborative agility among stakeholders, optimizing the hospitality ecosystem | dynamic pricing, enhanced customer loyalty, and new revenue streams from digital and virtual services, aligning with the broader goal of sustainable value creation for all ecosystem participants |

| [10] | not specified explicitly | not specified explicitly | blockchain framework to enhance micro-transactions within the Metaverse, addressing scalability and delay issues |

| [14] | experiences based on individual preferences, co-created experiences, experience offerings, virtual activities, a digital preview of the digital experience, tangibilizing services, ‘Phygital’ experiences | enhanced trust and security, streamlined information processing, enhanced marketing research capacity, employee training, reduced capital expenditure, stakeholder collaboration, service experience design and development, technological requirements, and employee training, technology requirements of users, technology interoperability | virtual selling, and digital marketing; by utilizing NFTs, businesses can offer customers distinctive and customized digital experiences that not only enhance customer loyalty but also contribute to increased revenue |

| [45] | providing an environment where end users can create and interact with virtual worlds, though it also highlights the need for ethical considerations and moderation to protect users from harmful designs | the creation, distribution, and monetization of user-generated virtual worlds, emphasizing the role of end users as both creators and consumers within the Metaverse ecosystem | microtransactions within these virtual worlds, sharing profits with creators, but raises ethical concerns about exploiting young users and encouraging potentially harmful spending habits |

| [46] | Transformation of the B2B market through digital service innovation, through technologies like IoT, intelligent automation, and digital platforms, leveraging digital interconnectivity | digital platforms in facilitating B2B interactions, more efficient, flexible, and customer-centric value chains, emphasizing data-driven decision-making and enhanced connectivity across ecosystem actors | recurring revenue streams such as subscriptions for software and connected equipment, product-as-a-service offerings, outcome-based contracts, and innovative rental and leasing offerings |

| [47] | not specified explicitly | Circular value chain within the energy metaverse framework, emphasizing the need for sustainable, efficient, flexible, resilient, and affordable business models and value chains; co-design toolbox that enables stakeholders to develop and evaluate their business models and value chains in alignment with circular economy principles. | not specified explicitly |

| [34] | “phygital” transformations and virtual transformations that deepen customer interactions | integrating virtual experiences with traditional business operations | direct-to-avatar sales |

| [30] | not specified explicitly | technological infrastructure and knowledge management; stakeholders’ readiness and stimulation of interest | not specified explicitly |

| [48] | not specified explicitly | implementing intelligent manufacturing by organizing operations within a virtual environment; utilizing the Internet of Things (IoT) to gather data from various production and operational flows; employing federated learning to address security issues related to data sharing, thus facilitating effective data analysis and decision-making processes | not specified explicitly |

| [32] | leverage the Metaverse to design immersive experiences, facilitating novel ways of interaction, collaboration, and transaction; the customer base in the Metaverse comprises individuals and organizations looking to explore and exploit the virtual environment for social, cultural, educational, and business activities | the role of technology management in navigating the complex infrastructure required to support the Metaverse, including the integration and innovation of technologies like AR, VR, blockchain, and AI; improved knowledge acquisition, sharing, and application facilitated by virtual environments | new revenue streams through the development of virtual products and services |

| [49] | the Metaverse has the potential to significantly remodel operations and supply chain processes, offering benefits such as enhanced innovation, collaboration, efficiency, agility, cost reduction in transactions, improved visibility and transparency, better information sharing, responsiveness, service levels, operational resilience, sustainable business models, revenue/profit enhancement, and promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion | for operations and supply chain management, the Metaverse can transform how goods are manufactured and transacted and how firms interact with customers, pointing toward an integrated, efficient, and responsive supply chain ecosystem capable of generating significant revenue streams; customers in the Metaverse can range from end-consumers seeking immersive experiences to businesses looking to innovate their product offerings and supply chain operations | the Metaverse is expected to create substantial economic value that spans various industries, including tourism, hospitality, retail, and more, allowing for immersive customer experiences before purchasing decisions |

| [50] | immersive experience, characterized by the illusion of place, the illusion of embodiment, and the illusion of plausibility | not specified explicitly | not specified explicitly |

| [35] | enhancing service maturity, reliability, and performance through a comprehensive optimization of Microservices, addressing development, deployment, and operational challenges | encompasses the entire lifecycle of Microservices, from development and testing through deployment to online operation, with an emphasis on security, reliability, and performance optimization | not specified explicitly |

| [51] | enhanced user engagement and new forms of online interaction | content creation, platform development, and infrastructure support, leveraging blockchain and VR technologies | virtual goods sales, real estate transactions, and immersive event hosting within these digital environments |

| [52] | creating engaging, game-like experiences across various contexts like learning, healthcare, and business | not specified explicitly | not specified explicitly |

| [53] | product differentiation, R&D, and innovation | network effects; enhancing the connection between virtual and physical businesses by establishing new infrastructure and confirming digital rights; developing active regulatory approaches for the metaverse sector to prevent unfair competition and data monopolies, to lower the barriers to entering and leaving the market; support the simultaneous development of digital and physical economies | pricing strategy |

| [54] | NFTs can redefine value propositions by offering unique, verifiable ownership of digital and physical assets | provenance, transparency, and authentication; NFTs support sustainable practices, combat counterfeiting, and incentivize stakeholders, thus opening up innovative business models and revenue opportunities in both digital and physical realms | monetizing digital assets and experiences, facilitating direct sales, and enabling secondary markets |

Notes: (1) the systematization is organized by the publication year and then alphabetically; (2) where a cell is marked not specified explicitly, the source does not state the element directly; we avoid imputing content beyond the text. Source: authors’ systematization.

3.3. Metaverse Business Model Development

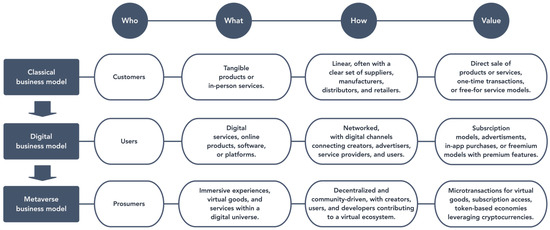

The transformation of the business model from classical to digital and then to the Metaverse can be described as a paradigm shift in how value is created, delivered, and captured (Table 2). Synthesizing across the reviewed studies, the following key transitions characterize this paradigm shift:

- From tangible to intangible. The classical business model focuses on tangible products and in-person services. As we move towards the metaverse model, the emphasis shifts to intangible, digital products and services, which are immersive and interactive.

- From linear to networked value chains. The traditional linear value chain of supplier-manufacturer-distributor-retailer-consumer is replaced by a more networked approach in the digital model. The Metaverse further evolves this into a decentralized ecosystem, where users contribute to and extract value from a virtual environment.

- From direct sales to subscription and freemium models. The classical model’s direct sales approach, often based on one-time transactions, transitions to subscription models, advertisements, and in-app purchases in the digital model. The Metaverse extends this with monetization strategies like virtual goods, experiences, and even blockchain-based transactions using cryptocurrencies and NFTs.

- From isolated operations to interconnected platforms. Classical businesses often execute core operations in isolation, whereas digital business models tend to leverage interlinked platforms. The metaverse model regards a fully integrated virtual platform where operations are deeply interconnected, and the boundaries between different service providers and users are blurred.

- From customer segmentation to community engagement. In the classical model, customer segmentation is key. The digital model introduces the concept of networked communities, which is further developed in the metaverse model, where user engagement and community development become central to the business strategy.

- From physical to virtual customer experience. The shift from physical customer experiences in the classical model to virtual experiences in the metaverse model represents a significant transformation. The metaverse model amplifies this by creating completely immersive virtual realities where the experience is not just a representation but a fully functional and interactive digital world.

- From centralized to more distributed control. Classical business models are typically centralized. Digitalization starts to distribute control, and while the Metaverse is still platform-centric, it has the potential to fully decentralize it, with users and creators having significant autonomy and influence over the platform’s evolution.

These transformations shape the business model’s ‘Who-What-How-Value?’ [5]. The ‘What?’ value proposition in the metaverse business model expands to include immersive experiences, virtual goods, and services within a digital universe. These offerings are often enhanced by technology such as virtual reality or augmented reality, which provides deeply engaging and interactive environments. In the Metaverse, the perspective is shaped by various value propositions, each offering unique advantages and solutions. From the fundamental importance of ethical data use to enhance customer experiences through immersion, interactivity, and digital twin technology, stakeholders navigate a realm where personalized guest experiences and transformational B2B markets intertwine. As digital ownership and play-to-earn models redefine user engagement, stakeholders grapple with the challenges and opportunities presented by circular value chains within the energy metaverse framework. The immersive experiences are characterized by illusion and plausibility and can also involve physical products being represented digitally. All of these factors highlight the complexities of service maturity optimization and the development of engaging, game-like experiences across diverse contexts. Additionally, it examines how NFTs redefine traditional value propositions by offering unique, verifiable ownership of digital and physical assets.

The business model is now decentralized and community-driven (‘Who?’), where creators, users, and developers all contribute to the ecosystem. Unlike the linear or even networked models, this approach relies on the active participation and co-creation of value by the community (Value?). Within the Metaverse, stakeholders collaborate to construct an inclusive and transparent value chain. The stakeholders may involve manufacturers, content designers, suppliers, tech partners, service providers, marketers, NFT owners and creators, customers, users, and the community. They establish ethical standards, integrating technology and creative content production to bridge the gap between virtual and physical commerce. Operations are streamlined across supply chains, with a focus on improving transparency through authentication and NFTs. Stakeholders embrace collaborative agility to optimize ecosystems and facilitate B2B interactions through digital platforms. Sustainability principles drive circular value chains, integrating virtual experiences with traditional business operations to create a more sustainable future.

Revenue generation is based on microtransactions for virtual goods, subscription access, and token-based economies leveraging cryptocurrencies (‘How?’). Revenue models strive to align with ethical practices while exploring diverse streams of profitability. The revenue streams manifest diversity, reflecting the multifaceted nature of digital economies. These include traditional avenues such as advertising, brokerage fees from sales, and design fees, as well as emerging models like dynamic pricing, micro-transactions, recurring revenue from subscriptions, outcome-based contracts, innovative rental offerings, sale of virtual items, access to premium digital spaces, or the utilization of blockchain technology for secure and decentralized financial transactions. Stakeholders leverage immersive value-added services and digital marketing techniques, utilizing NFTs to enhance customer loyalty and revenue. Revenue-sharing models within virtual worlds empower creators while recurring revenue streams from digital services drive sustainability. Monetization strategies focus on digital asset ownership and experiences facilitated through NFTs, facilitating direct sales and enabling secondary markets. As stakeholders navigate the evolving landscape, they explore innovative approaches to monetization while striving to ensure sustainable value creation for all ecosystem participants.

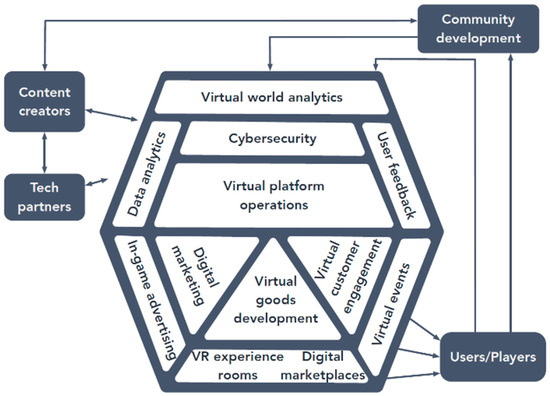

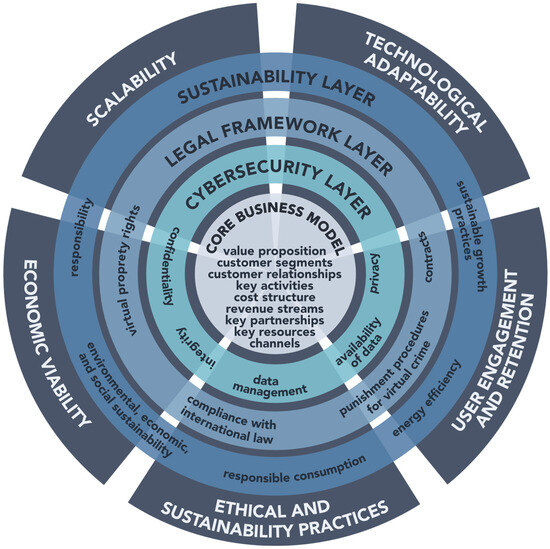

Figure 2 illustrates how the digital transformation journey redefines traditional business models, making them more adaptive to the digital age and the virtual economies exemplified by the Metaverse. It signifies a broader trend towards digitization, platformization, and cyber-physical systems, as well as the creation of participatory virtual economies driven by technological innovation. While the graphical representation emphasizes the “Who-What-How-Value” lens, the figure also implies deeper structural changes that are not immediately visible. Specifically, the metaverse stage is characterized by the broadening of the “Who?” dimension to include communities, creators, and decentralized actors, together with stronger feedback loops between value creation and value capture. This underscores the systemic nature of the transformation, where boundaries between firms and users blur, and co-creation becomes central to business model design. Whereas Figure 2 highlights the conceptual shifts in business logic, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 emphasize the expanded structural components and ecosystem linkages necessary to operationalize these shifts.

Figure 2.

The transformation from classical to metaverse business model’s ‘Who-What-How-Value?’ Source: Authors.

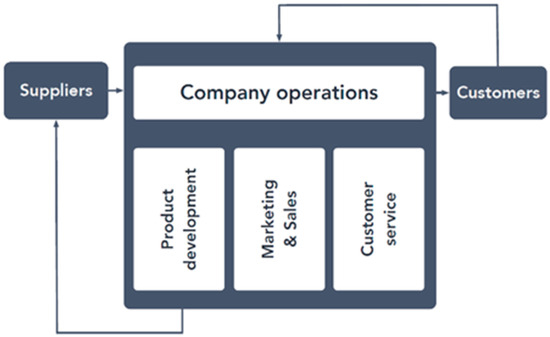

Figure 3.

An example of the classical business model. Source: Authors.

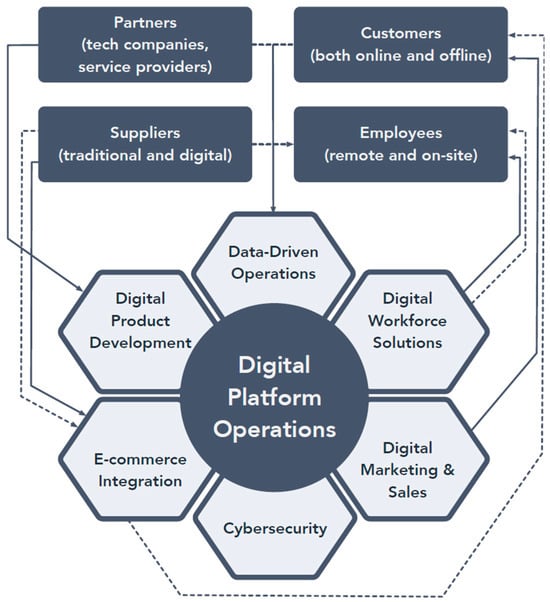

Figure 4.

An example of the digital business model. Source: Authors.

Figure 5.

An example of the metaverse business model. Source: Authors.

Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 demonstrate examples of transforming a value chain from the classical business model to a metaverse business model. Beyond the visual transition, the figures imply new functional requirements, such as identity and ownership verification, interoperability, and settlement mechanisms, which enable transactions and trust. Moreover, data analytics in the background functions as a horizontal backbone connecting diverse actors and activities, from content creators to communities. This expanded view clarifies that the metaverse value chain is not only more complex but also more interdependent, with B2B and B2C flows overlapping in a shared virtual infrastructure.

The classical model depicts a traditional, straightforward business setup centered on physical products and linear value chains (Figure 3) (for example, [1,4]). Figure 4 illustrates the shift to digital operations—networked and hive-like—emphasizing enhanced operational efficiency and new revenue streams through e-commerce and subscription services, as well as the parallel flow of information and tangible physical assets or goods and services. The digital model integrates digital platform operations, typically supported by cloud computing, big data analytics, and AI, to enable real-time data processing and personalized marketing (for example, [46]).

The digital business model (Figure 4) also covers cases where 3D/AR/VR features act as an auxiliary channel, while primary value is created and delivered outside a persistent shared spatial environment. The metaverse model (Figure 5) requires that a persistent, synchronous, spatial environment be the primary context of value, with continuity of identity and assets and, in more mature cases, there will be present a native user-generated-content (UGC) economy with monetization (creators co-create offerings and share in revenue), interoperability/composability (at minimum, an intent or roadmap for identity and asset portability across worlds), and community governance (governance embedded in operations and value capture).

Therefore, we classify a model as metaverse only when the primary locus of value creation, delivery, and capture is a persistent, synchronous, multi-user spatial environment (a shared world) that supports the continuity of identity and assets. If 3D/AR/VR is used only as an auxiliary channel while core value and monetization occur outside such an environment, the model remains digital. Such edge cases that use only selected metaverse-like elements (e.g., synchronous 3D without persistence and/or an economy) should be treated as advanced digital models with a proto-metaverse.

The metaverse business model (Figure 5) emphasizes the increased integration of operations, as well as the incorporation of immersive and interactive aspects, leveraging VR/AR technologies, blockchain, and AI-driven avatars to create fully interactive virtual environments. This model enables businesses to scale operations virtually, reducing physical infrastructure costs and creating diverse income opportunities. It offers increased customer engagement and interaction, transforming traditional customers into prosumers (for example, [34,51,54]).

Each stage in this evolution enhances business agility and scalability, enabling rapid market response and operational efficiency. Stakeholders are impacted differently at each stage. Digital models improve supplier relationships through better data sharing, while metaverse models offer new interaction methods for all stakeholders, enhancing their engagement and loyalty. For operational thresholds distinguishing business models across the digital-to-metaverse spectrum, see Section 3.3.5.

As value creation migrates to user-generated and tokenized assets, governance, security, and rights become first-order design variables rather than afterthoughts. Thus, the metaverse business model must remain adaptable in a multifaceted environment, where various questions arise regarding security, privacy, and rights issues, as well as sustainability and ethical concerns. Also, implementation is susceptible to technological availability, development, and comprehensive data analysis requirements, as well as ongoing user engagement issues. We continue to explore these questions in the following section, mapping the metaverse business framework.

3.3.1. Security, Privacy, and Rights

Among the first thresholds that every new system needs to overcome before it fully flourishes is resolving the legal issue. Since the Metaverse represents not only a technological advancement but a new way of doing things, it develops its own set of regularities and patterns. However, left unchecked, the behavior of the actors within this new framework could potentially harm some of the participants.

Additionally, Cobansoy Hizel [55] addresses human rights concerns that arise within the Metaverse. The author identifies the need for updated frameworks in light of technological and economic transformations that existing international instruments may not fully address.

The nuances of intellectual property rights are further examined by Zhou et al. [56], who address ownership issues in the Metaverse, with a particular focus on how these impact the success of user-generated innovations. The study articulates a nuanced understanding of virtual property and revenue generation, areas that have not been extensively studied within the context of the Metaverse. Key findings from the study reveal that the separation of content and platform ownership, along with their inherent interdependencies, creates significant tensions and challenges for entrepreneurs in the virtual world, possibly undermining other competing ownership interests. Such a dynamic poses risks to successful business creation, profitable technology development, and sustained innovation success from users.

However, the issue of intellectual property rights was sidelined by novel security threats and privacy issues that also require legal attention and measures. Digital forensic challenges and opportunities within the Metaverse and VR environments require further exploration, given the increasing risk of cyberattacks due to vulnerabilities and privacy issues. Ali et al. [57] present a metaverse forensic framework for investigating these cyberattacks, highlighting four specific cyberattack scenarios and their implications for virtual world security. The proposed forensic framework fits into a metaverse business model by enhancing the security and trustworthiness of the virtual environment. However, cyberattacks are not the only threat. Simon [51] mentions issues like sexual harassment as challenges within virtual environments, as well as potentially exploitative practices. Seo et al. [58] also developed a forensic framework focusing on potential crimes within the Metaverse, including money laundering, virtual burglaries, virtual theft, and fraud. Their framework consists of data collection, evidence examination and retrieval, analysis, and reporting. By providing methods for investigating and mitigating cyberattacks, businesses operating within the Metaverse can ensure a safer environment for users, which is crucial for maintaining customer confidence, trust, and protecting digital assets. This, in turn, makes the virtual space more appealing for commercial activities and investments.

Li [59] discusses the concept of “information fiduciaries” in the context of technology companies and their use of customer data. It suggests that these companies, such as Facebook (now Meta), should have a fiduciary duty, meaning they should act in the best interests of their customers, prioritizing their interests over their own, with a duty to maintain good faith and trust. This could be particularly relevant as platform companies in the Metaverse gain quasi-institutional power over users’ data and interactions.

Security and privacy are closely interconnected concepts in the digital world, where privacy refers to an individual’s right to control their personal information and keep it confidential. In contrast, security involves the measures and protocols implemented to protect data and assets from unauthorized access, breaches, and theft. Effective security practices are essential for maintaining privacy, as they safeguard sensitive information from potential threats and ensure that individuals’ personal data remains private and secure. Together, privacy and security create a trustworthy environment that enables individuals to share and store information securely. However, efforts to enhance security could intrude on privacy. This typically occurs when security measures require extensive monitoring, data collection, or access to personal information that individuals might consider private. For example, surveillance programs designed to detect criminal activity can also collect data on innocent individuals without their consent, raising privacy concerns. Balancing security needs with privacy rights is a critical challenge in the Metaverse, requiring careful consideration of the implications of security technologies and measures on personal privacy.

As the Metaverse expands, organizations focus on generating metadata, facing new cybersecurity risks due to vulnerabilities in AR, VR, IoT, blockchain, and cryptocurrencies [60]. This necessitates advanced risk assessment for infrastructure and devices involved in metadata management. Emerging threats involve cyber threats, including phishing, malware, ransomware, issues with metadata, Web 3.0, avatar security, deepfakes, and NFT spoofing. This emphasizes the importance of cybersecurity measures for cloud computing, IoT, AR, VR, wearables, and other emerging technologies that could act as a vector for attacks.

Security and privacy issues in the Metaverse are inevitably intertwined with supporting technologies. Blockchain technology plays a crucial role in advancing intelligent manufacturing within the Metaverse. Mourtzis et al. [61] focus on three main contributions: ensuring data validity, facilitating organizational communication, and enhancing process efficiency. They address cybersecurity challenges in the transition towards a highly digitalized “Society 5.0” and the industrial Metaverse, highlighting the need for further development in blockchain technology to overcome limitations in scalability, flexibility, and security. Rajawat et al. [62] also recognize the potential of blockchain and propose a new consensus mechanism combining Proof of Stake (PoS) and Proof of Authority (PoA) for enhanced security and scalability. The system features user-centric, decentralized identity management to safeguard personal information and utilizes smart contracts for secure Metaverse transaction processing, ensuring secure transaction proof, recording, and validation. Additionally, they introduce a reputation system that rewards rule-abiding users and penalizes violators. On the other hand, Habbal et al. [63] see AI as a solution for trust, risk, and security management (TRiSM). AI TRiSM in the Metaverse involves ensuring the development of safe, reliable, and ethically sound virtual spaces, contributing to the overall business model by enabling secure and trusted environments, which can attract more users and potentially open new revenue streams through secure virtual transactions, content creation, and enhanced user engagement in the Metaverse. This aligns with [32], which points out the need to establish interoperability standards, ensure user privacy, and address the ethical implications of virtual interactions.

Based on this overview, we broadly classify risks as (a) identity and ownership (IPR, identity theft), (b) integrity and availability (DoS, ransomware, spoofing), (c) conduct harms (harassment, harmful design), and (d) financial crime (fraud, laundering). Mitigating these risks is not only a compliance issue but a business imperative as trust translates into user retention, revenue stability, and long-term ecosystem viability. Because these risks translate into erosion of trust, exclusion, and increased resource intensity, their mitigation also becomes inseparable from ethical conduct and sustainability governance—issues we address in the following section.

These risks may be observed as the intersections of the technical dimension and conduct dimension with the individual and the ecosystem level. Identity theft and asset spoofing fall under technical at the individual level (for example, account takeover, counterfeit NFTs), denial of service and infrastructure outages fall under technical at the ecosystem level (for example, platform downtime, network failures), harassment and harmful design fall under conduct at the individual level (for example targeted abuse, dark patterns), and fraud and market manipulation fall under conduct at the ecosystem level (for example rug pulls, wash trading). Mitigations align with accountable stakeholders, with platforms responsible for identity controls, logging, safety operations, and resilience; creators responsible for user-experience choices and community norms; and regulators and standards bodies responsible for rights, auditability, and due process. These mappings lead us to further examination of sustainability and ethical issues in the next section, as well as technological issues and data analysis after that. Taken together, they correspond to the legal framework and sustainability layers in Figure in Section 3.3.6, making the feedback loops among compliance, trust, inclusion, and long-run viability explicit.

3.3.2. Sustainability and Ethical Issues

Metaverse was created through business endeavors, and scientists are catching up to observe the regularities and patterns of its systems and applications from various perspectives. As previously discussed, legal issues reveal that it is an emerging concept with the potential to foster various behaviors. Therefore, an understanding of the future requirements for sustainable entrepreneurship in the Metaverse is needed [64].

De Giovanni [65] outlines the implications of metaverse technologies for sustainable business models. The author emphasizes responsible digitalization, focusing on the triple bottom line (encompassing economic, environmental, and social aspects), ESG criteria (Environmental, Social, and Governance), and the SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals). The findings relate to creating a metaverse business model by highlighting the importance of sustainability, ethical considerations, and social impact. The value proposition revolves around responsible innovation, while the value chain integrates sustainability at each stage. The revenue model would derive from digital goods and services that align with sustainable and ethical guidelines. Their integration in the value chain could involve supply chain transparency, carbon reporting, or tokenized impact credits.

From an environmental standpoint, the Metaverse promises to reduce carbon emissions by substituting physical resources with digital assets and virtual interactions. However, there is a part of physical resources that is even more extensively used, from server farms to the user equipment. Further concerns about energy consumption and carbon emissions related to blockchain transactions highlight the need for sustainable energy solutions within this digital realm [66]. Based on their review, the authors conclude that organizations involved in the Metaverse are likely to enhance their sustainability efforts by adhering to robust governance practices outlined in the ESG framework. By acknowledging and addressing the Metaverse’s social, environmental, and governance challenges, stakeholders can better manage sustainability issues.