Abstract

Polycentric governance enables decentralized yet coherent multilevel decision-making by fostering alignment across governance, policy, and strategic goals. In the United States (U.S.), a prominent global climate actor, this polycentric structure is being tested. An Executive Order issued on 8 April 2025, opens the possibility to stop the enforcement of state-level laws that might condition the exploitation of energy resources based on considerations concerning climate change and the environment. This federal action might disrupt subnational efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and mitigate climate impacts, exposing a misalignment between federal and state climate governance—a dynamic that remains underexplored in the existing literature. This critical mini-review article proposes a novel conceptual framework that presents this misalignment between federal and state climate perspectives as an emerging meta-system pathology in U.S. climate governance, introducing the concept of perspective desalignment. Drawing on the analysis of 73 Web of Science papers and a review of 16 journal articles published in 2018–2025, this study highlights the breakdown of shared understanding and strategic coherence among key stakeholders, including federal and state governments, industry, and academia. The findings underscore that any effective climate governance will require federal–state realignment. The paper concludes with implications and recommendations for restoring alignment and enabling more effective, collaborative climate governance.

1. Introduction

Advanced economies, including the United States, Canada, Japan, and countries in Western Europe, are expected to continue reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the following decades, driven by their service-oriented industrial structure, sustainable energy mix, and robust climate policies [1,2]. Major global actors, notably the U.S., China, and the European Union (EU), have committed [3] to pursuing climate mitigation. This will foster intensive strategic competition across sectors related to carbon neutrality, involving energy, standards, and regulations under polycentric governance [4]. From an institutional analysis perspective, the concept of polycentric governance, first articulated by Elinor Ostrom, recipient of the 2009 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences [5,6] for addressing complex environmental challenges (e.g., climate change, water governance, and energy transitions), is characterized by multiple decision-making centers (e.g., national, subnational, and local authorities), each with varying degrees of formal independence, that interact through competitive, cooperative, or contractual relationships and operate under an overarching set of rules [5,6,7,8,9,10]. Elinor Ostrom [5]’s idea of polycentric governance extends the conceptual origin of polycentric political systems introduced in 1961 by Vincent Ostrom et al. [8], in contrast to monocentric or centralized forms of governance. Polycentricity has long been viewed as the antithesis of centralized bureaucracy and a path toward resilience, flexibility, diversity, inclusion, and local responsiveness of real-world governance systems [5,6,8,9,11,12,13,14], such as those forming the U.S. federal structure [15,16,17]. Polycentric governance offers promising opportunities for climate action [18]. For example, tensions between state and federal institutions in the U.S. can be examined via the polycentric governance paradigm [19], especially when contrasting it with a top-down federal climate action, which would be a monocentric form of governance [17,20]. On the surface, it may appear that the collection of actions by both the federal and state sides would suffice to reach resilience at the nation-state. However, in systems thinking, resilience is not only about adapting well in the face of adversity or significant sources of stress [21,22,23], it also requires decentralization of decision-making [24] and alignment, coherence, or harmonization of goals or policies across governance system layers [25,26,27].

Climate resilience is not merely an ecological or technological issue [28,29,30,31,32]—it is fundamentally a systems challenge. Addressing it effectively—whatever the political position may be regarding the emission of greenhouse gases or the preparation for climate change-induced events—requires alignment across governance levels, institutional logics, and operational strategies [2,27,33,34,35].

Historically in the U.S., federal support significantly leverages and encourages state-level climate initiatives through supportive climate policies, funding programs (e.g., Climate Pollution Reduction Grants for states, local governments, tribes, and territories), enhancing the states’ capacity against extreme weather events (e.g., natural disasters), and providing financial support (e.g., Inflation Reduction Act of 2022) to address climate-induced events, reduce energy costs, and invest in clean energy [36,37,38,39]. Herrick and Vogel [36] and Farmer [37] empirically demonstrated that state and federal financial investment increases the likelihood of success for municipal energy programs. As in any federal system, where federal and state governance levels are organically related through a bi-directional relationship (i.e., a mutual influence between federal and state climate governance, policies, and choices, rather than a one-directional blocking process), positive and negative feedback exist between these two levels of the U.S. federal system [40,41,42].

Based on the literature, over the past three decades, some republican presidential campaigns—bolstered by party leadership in both the U.S. Senate and House—have persistently challenged the legitimacy of climate crisis mitigation efforts and the scientific consensus on anthropogenic climate change [43]. This opposition reflects a broader ideological resistance to environmental and climate policy [44]. Political ideology continues to shape both national and subnational approaches to climate change adaptation and mitigation, often driving ideologically motivated governance frameworks [45]. As a complex socio-environmental phenomenon, public understanding of climate change is deeply influenced by collective dynamics, including socio-demographic factors, personal values, and political orientation [46].

The governance of U.S climate policies has a pluralistic and federalistic structure [47]. Up to two dozen states have climate policies that may make them compliant with the Paris agreement; however, the U.S. withdrawal from this agreement, which aims to encourage subnational institutions to participate in a polycentric, multistakeholder governance structure, poses a serious challenge [48]. States can defend their independence in climate action under the U.S. federalist system. This situation is not unique to the U.S., as it is also apparent in the tension between the EU and member states on different topics, including energy and climate policies. Nonetheless, the Executive Order of 8 April 2025, which intends to address state energy laws touching climate and environmental impacts [49,50], seems to suggest that emerging disagreements between the U.S.A.’s state and federal levels can lead to systemic fracture, a meta-system pathology brought about by a breakdown in shared understanding and strategic alignment across federal and state institutions. From the complex system governance (e.g., U.S. climate governance) viewpoint, meta-system pathologies are dysfunctions within a meta-system, the overall level where the governance coalesces, yielding the coordination, control, communication, and integration or management of subsystems or constituent systems (i.e., governed systems) [51,52,53,54,55,56,57]. In this light, federal and state institutions should be seen as interconnected complex systems, or systems of systems (SoSs) [58,59] made up of numerous components that interact with each other in intricate ways, leading to emergent behaviors that are difficult to predict or understand solely from the individual parts [60]. If one subscribes to this viewpoint, dealing with climate laws requires a different set of lenses.

U.S. climate governance can be characterized as a polycentric governance system where multiple decision-making centers, including federal, state, and even local governments, interact, overlap, and sometimes conflict in shaping climate-related policies [26,43,48,61,62,63,64,65,66].

States and cities have taken on a more substantial role in addressing climate change in global debates and local endeavors [67]. In the U.S., states such as California, New York, and Texas have taken the lead in implementing policy-driven collaborative climate governance to enhance local and subnational level dynamics and community responses to national politics and policy, fostering industrial innovation in renewable energy, grid optimization, smart grids, advanced metering infrastructure, and sustainable urban planning [15,68,69,70,71,72]. Moreover, residents in Colorado have actively resisted unconventional oil and gas (UOG) production [73]. These initiatives were not isolated experiments; they leveraged bottom-up resilience to climate change [74,75,76] and represented localized responses to global challenges, underpinned by data, science, and regional realities. A substantial portion of climate adaptation efforts took place within tribal communities and through state and municipal governments, irrespective of who were in the Oval Office [47]. These climate efforts are initiated at the state level to support boomerang federalism [77]. In the context of increasing the understanding of the relationship between subnational and national climate change politics in the U.S., Fisher [77] introduced the concept of boomerang federalism, which builds on the extant research on federalism and vertical policy integration and alignment following the country’s vertical climate governance structure. Fisher [77] proposed boomerang federalism for describing a phenomenon where subnational governments take progressive or innovative policy actions that then influence or boomerang back to the federal level, prompting national-level policy change or response. Any conflict between the federal and state levels, as the mentioned federal Executive Order might provoke, will reverse years of progress, potentially destabilizing a delicate intergovernmental balance essential for climate resilience. Noteworthy, such a conflict will likely undermine trust, deter investment, and introduce volatility in strategic planning, particularly in industries that thrive on long-term stability and innovation.

Despite increasing attention to multilevel climate governance as a form of multistakeholder or polycentric climate governance [43,48,61,63,65], there remains a notable gap in the scientific literature regarding the systemic misalignment that might materialize between federal and state climate perspectives in the United States when implementing the recent Executive Order [49,50]. This paper addresses that gap by proposing a novel conceptual framework that interprets this potential federal–state desalignment as an emerging meta-system pathology within U.S. climate governance, introducing the concept of perspective desalignment. The core challenge for this study is to digest the relevant literature to shed light on how to best approach the crossroads between climate meta-system levels in the U.S. polycentric vertical climate governance structure, U.S. climate change policies, U.S. climate resilience, bottom-up resilience, and boomerang federalism. Section 2 details the research methodology employed in this study. Section 3 introduces and elaborates on the conceptual framework. Section 4 discusses key implications and offers recommendations. Finally, Section 5 presents the study’s conclusions and potential limitations and outlines directions for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

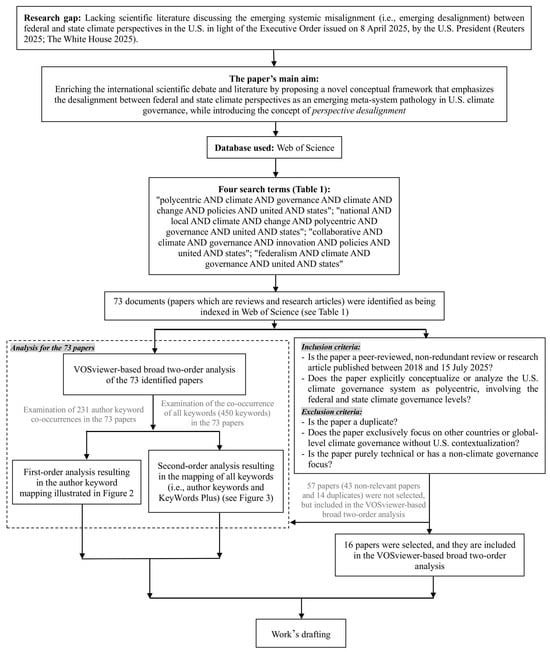

This study utilizes a four-term research methodology, involving a broad two-order analysis (Figure 1). A literature review is effective for synthesizing research findings and constructing conceptual and theoretical frameworks [78,79,80]. The Web of Science database is utilized to identify peer-reviewed papers and perform the conceptual framework presented in this paper. Four search terms were taken into account: (i) [polycentric AND climate AND governance AND climate AND change AND policies AND united AND states]; (ii) [national AND local AND climate AND change AND polycentric AND governance AND united AND states]; (iii) [collaborative AND climate AND governance AND innovation AND policies AND united AND states]; and (iv) [federalism AND climate AND governance AND united AND states] (Table 1). By searching “All fields” in the Web of Science database, the search terms result in a total of 73 published documents that are all review articles and research articles (i.e., all published documents are journal articles) (Figure 1 and Table 1). The inclusion criteria for this study consisted of: (i) peer-reviewed, non-redundant review articles and research articles published between 2018 and 15 July 2025; (ii) papers that explicitly conceptualize or analyze the U.S. climate governance system as polycentric, involving the federal and state climate governance levels. To ensure relevance, exclusion criteria are applied to remove (i) duplicate papers, (ii) papers focusing exclusively on other countries or global-level climate governance without U.S. contextualization, and (iii) papers with a purely technical or non-climate governance focus. To remove duplicates from the 73 published papers, a Web of Science plain text file (i.e., .txt file) was saved for each of the four search terms, and then the four plain text files were merged into a single .txt file. Based on the 73 document titles, 14 duplicate papers were removed using RStudio (version 2023.06.1 + 524) [81] (Figure 1 and Table 1). Following the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Figure 1), 43 non-relevant papers—excluding the 14 duplicates—were removed, and the total number of documents was reduced from 73 to 16 journal articles (i.e., reviews and research articles) (Figure 1 and Table 1), providing the most direct empirical or conceptual contributions to understanding polycentric climate governance in the U.S. context. While geographical distribution and methodological diversity were remarked, the primary selection rationale was thematic alignment with the present critical mini-review, based on the used search terms (Figure 1 and Table 1).

Figure 1.

Diagram of research methodology. The research gap was formulated in light of the Executive Order issued on 8 April 2025 [49,50].

Table 1.

The number of relevant papers per search term used in the Web of Science database.

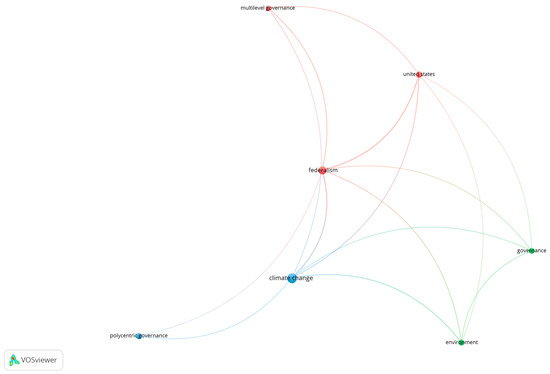

VOSviewer (version 1.6.20) [85] was used to conduct the broad two-order analysis based on the full counting approach for the 73 published papers identified in the Web of Science database (Figure 1 and Table 1). The single merged .txt file was subject to running the VOSviewer analysis (Figure 2 and Figure 3). The 14 duplicates retrieved through the search terms used are among the analyzed 73 documents; the combined dataset was processed and analyzed in VOSviewer, which automatically handles duplicate records through digital object identifier (DOI) and title matching [85]. Figure 2 depicts the results of the first-order analysis, involving the examination of 231 author keyword co-occurrences across the 73 papers. To establish the author keyword mapping illustrated in Figure 2, the selected minimum frequency of a keyword is set to five, following the default setting in VOSviewer. This minimum occurrence threshold’s value has been widely used in previous VOSviewer-based bibliometric studies to balance network density and interpretability [85]. Figure 2 demonstrates that the most extensive collection of interconnected author keywords comprises seven. It reveals the existence of three author keyword clusters, linked by two key terms: climate change and federalism. Referring to Figure 2, the first cluster consists of three interrelated author keywords—federalism, multilevel governance, and the United States. The second cluster encompasses two intercorrelated author keywords—governance and environment. The third cluster contains two interconnected author keywords—polycentric governance and climate change.

Figure 2.

VOSviewer-generated co-occurrence map of author keywords for the 73 papers found in Web of Science.

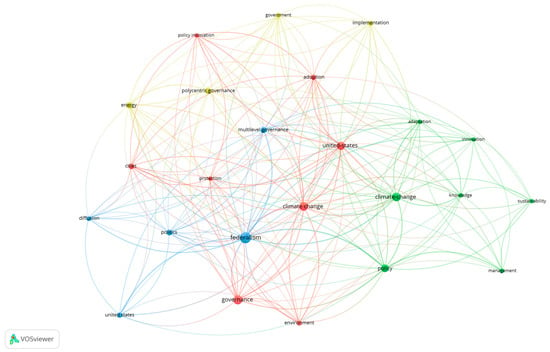

Figure 3.

VOSviewer-generated co-occurrence map of all keywords (i.e., author keywords and KeyWords Plus) for the 73 papers found in the Web of Science database.

Figure 3 presents the outcomes of the second-order analysis, which entails examining all keyword co-occurrences in the 73 published papers found in the Web of Science database (Table 1). The mapping of all keywords is constructed with a minimum frequency threshold of five in the VOSviewer, following the default setting in VOSviewer and as justified for the mapping of author keywords shown in Figure 2. Of the 450 keywords, 25 meet the threshold (Figure 3). Removing the keyword Canada from those 450 keywords, there remain 24 keywords that meet the threshold. It discloses the presence of four clusters of all keywords, linked by two key terms: climate change and federalism. As shown in Figure 3, the first cluster encompasses eight interrelated keywords: adoption, cities, climate change, environment, governance, policy innovation, protection, and United States. The second cluster contains seven interconnected keywords: policy, adaptation, climate-change, innovation, knowledge, management, and sustainability. The third cluster comprises five intercorrelated keywords: multilevel governance, federalism, politics, the United States, and diffusion. The fourth cluster contains four interconnected keywords: polycentric governance, implementation, government, and energy. Figure 3 presents the hidden concepts and their interconnections with the seven essential ones (i.e., polycentric governance, multilevel governance, climate change, federalism, governance, United States, and environment) for this study (Figure 2). The next section of this paper highlights the key concepts observed in Figure 2 and Figure 3, as well as their relationships in the context of U.S. climate governance as a polycentric governance system, which contributes to the development of a novel conceptual framework.

3. Conceptual Framework

The ability of governments to evaluate, prevent, prepare for, respond to, and recover from climate-induced disasters relies on several factors, including efficient governance mechanisms, policies, laws, strategic planning, equity metrics, standardized protocols, and a systems approach to cross-sectoral concerns and multidimensional challenges [25,86]. In policy and research, the concept of coherence has been used widely and ambiguously to refer to a wide range of understandings, including coherence between actors, levels of governance, different policies and goals, goals and resources, and the three global normative frameworks (GNFs)—the Sendai resilience framework for disaster risk reduction 2015–2030, the United Nations (UN) 2030 agenda for sustainable development, and the Paris agreement under the UN framework convention on climate change (UNFCCC) [27,87,88,89,90,91]. Inspired by a model of hourglass federalism or hourglass federal systems as institutional configurations of governments [92], the authors of [87] emphasized systemic coherence between those three interconnected GNFs to describe how they are horizontally interlinked at the international scale. Globally, national and subnational governance structures ensure the implementation of climate actions [93]. Increased participation, bottom-up climate stakeholder engagement, and collaboration between subnational and national government levels are essential for leveraging climate change adaptation [94]. A polycentric governance system is a condition for being able to manage the trade-off between maintaining local autonomy and coordinating decisions at the regional level across fragmented policy communities [95].

Furthermore, the authors of [96] suggest that a polycentric climate policy network may facilitate the overcoming of central government blockages. The literature on climate change mitigation and energy transition has long shown the importance of actions from different levels of government, which can be ensured through polycentric governance [97]. Policies are catalysts for goals; the challenge of polycentric governance lies in aligning policies and, therefore, goals across diverse governance mechanisms [26]. At the subnational climate and environmental governance level, U.S. state and local actors play a central role in environmental policy development and implementation [84]. Thousands of industrial enterprises and many subnational U.S. governments are actively working to combat climate change [63]. On the one hand, state and local governments are the implementation agents for a wide range of federal policies in the U.S. [82]; on the other hand, compared to national governments, subnational entities such as states and other actors have often taken the lead on policy in climate change politics [83], which enhances boomerang federalism [77] and bottom-up resilience (i.e., bottom-up climate resilience) in the U.S [74,75,76].

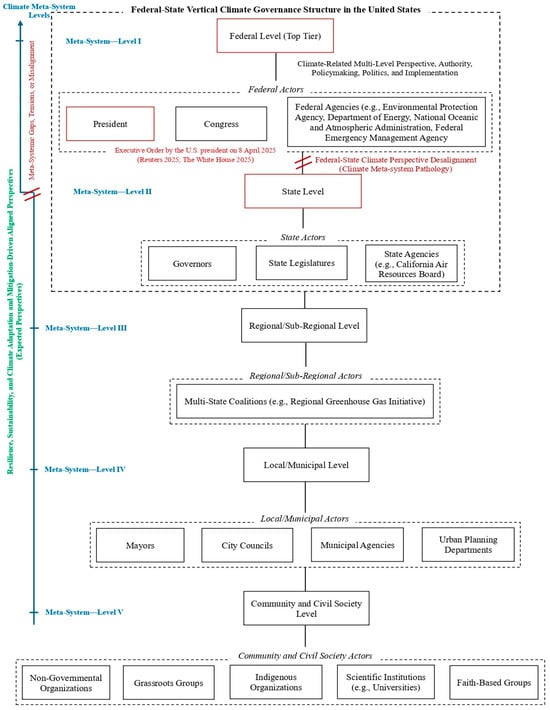

Transitioning from systemic coherence between the three GNFs toward alignment involves moving toward a multilevel federal system-based polycentric or multilevel governance to consider the vertical relationships between global, regional, sub-regional, national, and subnational decision-making institutions [87,98]. Polycentric governance is theorized to enhance efficient policy execution by using local knowledge and experience, fostering the involvement of non-governmental actors, and utilizing the coordinating and sanctioning power of centralized authorities [99]. The U.S. operates under a federal political system—power and authority are constitutionally divided between the federal (i.e., central or national) government and individual state (i.e., subnational) governments [100,101]. In the intersection between federalism and climate governance, it appears that the U.S. Constitution divides the duty for international agreements such as the Paris agreement between the executive and legislative branches, and hence excludes states from having a formal role in such affairs, which has significant implications for full U.S. commitment to climate-related treaties [15]. Therefore, one could argue that state policies have considerable limitations, both in terms of horizontal diffusion across regions and in vertical diffusion that informs and drives federal policy. In this case, a polycentric vertical climate governance structure refers to how a climate-related multilevel perspective, authority, policymaking, politics, and implementation responsibilities are distributed across different levels of government and societal actors (i.e., climate governance layers, climate governing structure levels, or climate meta-system levels), from national to local, as shown in Figure 4. The hierarchical structure (i.e., the five-level meta-system structure) of the U.S. polycentric vertical climate governance, illustrated in Figure 4, aligns with the empirical distribution of authority observed in the U.S. polycentric governance. It is supported by the recent publications cited in Table 1 and (i) a work analyzing the structure and alignment of U.S. multilevel climate policies [102], (ii) a study on American climate policy odyssey-based shift of intergovernmental roles [103], (iii) a contribution emphasizing decarbonization-driven federalism or new climate federalism in the U.S. [104], (iv) a paper investigating pro-climate coalitions in the U.S. [105], and (v) interstates alliances (e.g., the U.S. Climate Alliance [106]). Moreover, the separation between the fourth and fifth levels (i.e., the local/municipal level and community and civil society level) of the U.S. polycentric vertical climate governance structure (Figure 4) is supported by recent conceptual [17] and empirical [107] frameworks within the U.S. context. The recent federal Executive Order [49,50], when implemented by the Department of Justice, will clash with state-level climate change policies, e.g., blocking the enforcement of state laws passed to reduce carbon emissions and combat climate change. This, more than just a climate policy shift, will most certainly result in a profound systemic dysfunction of the U.S. multi-level climate governance structure. We refer to this situation as federal–state perspective desalignment. Indeed, the Executive Order, with a clear focus on energy, directed the U.S. Attorney General to identify state laws that address climate change, environmental, social, and governance (ESG) initiatives, ecological justice, and greenhouse gas emissions, and to take action to block them, based on a report that the Attorney General should submit within 60 days after the order’s date [49,50]. This report by the Attorney General has not been submitted as of October 2025. Therefore, although some actions against the states’ laws have been initiated (e.g., two lawsuits—U.S. v. Vermont [108], in the U.S. District Court for the District of Vermont, and U.S. v. New York [109], in the US District Court for the Southern District of New York—challenging those states’ climate superfund laws), the Executive Order is ineffective as of today. So, nobody can really be sure what its real impact is going to be. The conceptual framework proposed in this study is a theoretical methodological approach intended to help analyze such a state of affairs [49,50].

Figure 4.

Federal–state climate perspective desalignment as an emerging meta-system pathology in U.S. polycentric governance. The Executive Order [49,50] is indicated within this sketch.

Desalignment means systemic misalignment or disconnection, often implying the loss of prior alignment, lack of coordination, or deeper structural discord between different-level meta-systems or governing structures (i.e., different-level higher-order systems or higher-level systems [51,52,53,54,55,56]), such as the federal and state levels (Figure 4), i.e., misalignment between vertical meta-systems or meta-systemic misalignment in this study. The concept of desalignment is more commonly presented as systemic misalignment in political, social, or strategic discussions in frameworks related to polarized and punitive intergovernmental relations [110], mismatches in governance design versus capacity [111], divergence of state responses from federal ones in pandemics (e.g., coronavirus disease 2019 or COVID-19) [112], and institutional misalignments between what the constitutions say and how federal and local governments operate within federations [113]. Furthermore, in politics and international relations, Kissinger [114] discusses strategic desalignment in the context of shifting global power structures; in EU and governance studies, the authors of [115] analyze political desalignment between EU institutions and national policies. Generally, the concept of desalignment is less common and French-influenced, sometimes used in European English, influenced by a French term: “désalignment” [116]. So far, the construct of misalignment is more common in English. Desalignment and misalignment both refer to a lack of proper alignment, while they have subtle differences in usage and connotation. Misalignment is widely used in technical (e.g., mechanics [117]), organizational (e.g., misalignment between the team’s goals and management’s expectations [118]), everyday contexts, and even governance and policy studies to describe governance/policy misalignment [26,119,120]. Desalignment is suggested as best suited for frameworks relating to meta-system pathologies (or meta-systemic pathologies or failures, e.g., mismatches and divergence between different-level meta-systems) in different fields, including climate meta-systems or climate meta-system levels—involving climate meta-system pathologies or climate meta-systemic pathologies—(Figure 4) within polycentric climate governance structures or environments [5,6,8,11,12,13]. Based on the general, pragmatic conception of Hall [121] and Baumgartner and Jones [122] on the perspective-policy nexus, perspectives often precede and originate policies, which is analogous to inceptions preceding conceptions and perceptions—one can say that perspective desalignment promotes policy misalignment and incoherence between governance layers. Moreover, considering the two-way causality between perspectives and policies [123], the misalignment or incoherence of policies [27,87,88,91] strengthens perspective desalignment between meta-systems, and therefore erodes polycentric governance.

The comprehensive sketch shown in Figure 4 illustrates the U.S. polycentric governance system, where five climate governing structures or decision-making centers operate. There, we illustrate where the emerging meta-systemic misalignment (pathology, gap, or clash) between the federal and state levels might occur. When the federal climate governance level or top-tier level (e.g., the president, Congress, and federal agencies, including Environmental Protection Agency or EPA, Department of Energy or DE, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration or NOAA, and Federal Emergency Management Agency or FEMA) actively dismantles or obstructs state-level climate actions, it might give rise to the circumstances that will eventually result in a meta-system pathology [51,52,53,57]. When the pathology takes shape, the overarching system no longer functions as a unified organism but as a fractured entity (Figure 4). As shown in Figure 4, vertical coordination is fragmented, which makes alignment critical on the path toward achieving a consistent and synergic climate policy (i.e., alignment of goals and perspectives) by the five climate meta-systems: (i) federal level; (ii) state level, including governors, legislatures, and state agencies (e.g., California Air Resources Board or CARB); (iii) regional/sub-regional level, including multistate coalitions (e.g., Regional Greenhouse Initiative); (iv) local/municipal level, including mayors, city councils, municipal agencies, and urban planning departments; and (v) community and civil society level, including scientific institutions, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), grassroots groups, indigenous organizations, and faith-based groups.

The economic dimension of climate policy alignment or realignment [26,87] enters into the picture at the intersection between investments by private and public actors, subsidies and other forms of public aid, direct and indirect costs to end consumers, economic sustainability, and the polycentric governance structure [61]. All these factors can be affected by an emerging climate meta-system pathology (Figure 4). As all climate actions interact with, transform, and depend upon economic activities, any pathology will affect the distribution of costs and benefits of those actions. Some consequences are direct, such as the magnitude of investments, some are mediated by markets, as the effects on prices of goods and services, and others are much more difficult to anticipate, as the potential impact of climate-induced high-impact and low-probability events (e.g., natural disasters) years or even decades into the future.

Polycentric climate governance is a systems approach, participatory multistakeholder governance, a landscape for policy alignment, and a lever for innovation and the triple bottom line (i.e., economic, social, and environmental) of sustainability in general and economic sustainability in particular for countries, through harmonized, coordinated, and decentralized collective economic actions and common goals-oriented contributions by different institutions or organizations to find adaptable and flexible solutions [5,6,11,12,13,24,48,124], allowing for coping with economic sustainability challenges (e.g., energy costs [37,44,71,97,125], economic sustainability-driven circular economy [126], etc.). Therefore, polycentric vertical climate governance is vulnerable to meta-systemic disruptions, such as cascading perspective desalignment-caused climate policy misalignment and uncertainty, spreading over climate meta-system levels, including the federal and state levels (Figure 4), which can engender more profound clean energy market uncertainty [127], a downturn in the renewable energy sector by slowing the renewable transition, and undermining long-term trust among investors (i.e., long-term investments) in cleaner energy initiatives and innovation [128].

4. Implications and Recommendations

4.1. Implications and Recommendations for Scientific Institutions

Why should the federal–state climate governance perspective desalignment be considered a significant issue? Because, as a meta-system misalignment, it risks causing cascading failures at regional/sub-regional, local/municipal, and community and social levels (i.e., the three climate meta-system levels under the federal and state levels). This has vast implications, not just environmental, but also economic and social. Rather than empowering bottom-up resilience and boomerang federalism by strengthening communities and subnational actors to innovate and act, a desalignment will result in impairments—either top-down through federal directives that centralize control, thereby blocking local climate change mitigation and adaptation initiatives, regardless of their effectiveness; or bottom-up, with actions clashing with federal provisions (Figure 4). A polycentric climate policy would align patterns of climate-relevant consumption and production in the U.S. industrial and energy systems. This objective will certainly be stalled by the climate governance perspective desalignment. Consequently, no effective governance will be possible without a balance between autonomy and sovereignty for a shared perspective approaching climate change policy as a platform for sustainable growth.

The misalignment between federal and state perspectives on climate policy generates several critical barriers to climate resilience:

- Disrupted research-to-policy cycles: Conflicting federal and state agendas can lead to the marginalization or misapplication of scientific findings, undermining evidence-based policymaking;

- Funding instability: Federal resistance to climate initiatives jeopardizes sustained funding, leaving states with limited resources to compensate for withdrawn or restricted grants;

- Knowledge fragmentation: In the absence of coordinated national efforts, climate research becomes increasingly localized and siloed, impeding data integration, shared learning, and the development of coherent, system-wide strategies.

Scientific institutions as community and civil society actors are crucial in designing, validating, and disseminating frameworks for climate and energy transitions [125,129,130,131,132]. Scientists should become more than observers—they must engage as systems translators and crucial climate policy actors, ensuring that evidence is accessible, persuasive, and adaptive across governance levels. Moreover, scientists also have the duty to translate complex scientific knowledge into practical insights that policymakers, managers, and the public can act on. They should act as bridges between data and decision-making in a polycentric climate governance system, as illustrated in Figure 4. Furthermore, scientists must upgrade their involvement in creating a shared understanding of climate change and accountable climate policies and governance among individuals and institutions across the five climate meta-system levels (Figure 4).

4.2. Implications and Recommendations for Policymakers

For policymakers at the state level (Figure 4), the meta-system misalignment leads to climate resilience barriers such as:

- Policy vulnerability: State laws risk invalidation or obstruction, disincentivizing innovation-based climate resilience;

- Legal and constitutional strain: Inter-jurisdictional conflicts may escalate, diverting resources away from implementation and into litigation;

- Short-termism: Under uncertain federal climates, long-term planning (e.g., state-level net-zero or decarbonization targets, investment in renewable energy infrastructure, climate-resilience urban planning, etc.) becomes politically and economically risky. This will result in planning myopia among policymakers in the U.S.

States looking for a path forward should aim at coalition-building, interstate strategic alliances (e.g., the U.S. Climate Alliance [106]) as polycentric coordination and alignment mechanisms, and an insistence on resilience-based design in all new policies. To do so, states and even cities or regions should (i) create collective leverage to balance—rather than confront—federal decisions in the context of interacting adaptively with the federal level to achieve complementarity and climate resilience for the U.S., which aligns with the vision of polycentric governance theory regarding subnational activity [5]; (ii) reinforce polycentric climate governance by activating a horizontal layer of governance, reducing over-reliance on federal consistency, and avoiding climate policy/action conflicts with other states [133,134]; and (iii) foster policy innovation and diffusion through the sharing of climate data and policy innovations, as done, for instance, by Washington State negotiating the linkage and coordination of its cap-and-invest emissions trading system with the already linked market of California and Québec [135] or collaborating on zero-emission goals.

4.3. Implications and Recommendations for Resource Managers

From energy and water utilities to emergency planners, the federal–state perspective desalignment introduces numerous climate resilience barriers. For instance:

- Operational confusion: Conflicting signals from federal agencies (e.g., EPA, DE, NOAA, and FEMA) and state agencies (e.g., CARB) (Figure 4) will disrupt planning cycles and increase compliance costs;

- Systemic inefficiencies: Fragmented policy leads to redundant or contradictory infrastructure investments;

- Reduced adaptive capacity: In climate-sensitive sectors, lack of cohesion hampers real-time response to climate change-induced disruptions (e.g., heatwaves, droughts, etc.).

Resource managers (e.g., water resources, energy and utility, forest and land, agricultural and rangeland, and coastal and marine managers), as key actors in climate governance, especially at the operational and ecosystem levels, need clear and consistent governance signals. Otherwise, the systems they manage become rigid rather than resilient. Federal and state agencies should systematically coordinate with resource managers to set clear—and ideally stable—standards for GHG emissions (e.g., under the Clean Air Act); set consistent climate adaptation tools and policies; establish balanced norms for the monitoring air and water quality, and the control of pollution; prepare for hazard mitigation (e.g., building resilient infrastructure—BRIC program); etc.

5. Conclusions, Research Limitations, and Future Research

Drawing on systems thinking, climate policy research, multilevel governance, and institutional analysis, this paper analyzes a large pool of 73 papers and reviews 16 peer-reviewed journal articles (Figure 1) to enrich the international scientific debate and literature by discussing the emerging desalignment between the state and federal perspectives on climate governance layers due to the recent executive order in the U.S., while introducing the construct of perspective desalignment. While state–federal misalignment is not unique to the U.S., this study provides a novel conceptual framework, taking as an example the desalignment of perspectives that might occur in U.S. climate governance as a consequence of a recent Executive Order.

Our conceptual framework is based on the combination of Nobel Prize laureate Elinor Ostrom’s idea of polycentric governance with a meta-system pathology model, thus offering an interdisciplinary perspective. Furthermore, this paper examines the challenge arising from the potential emerging desalignment in the U.S. climate policy, taking into consideration meta-system pathologies, climate meta-system levels in the U.S. polycentric vertical climate governance structure, U.S. climate change policies, U.S. climate resilience, bottom-up resilience, and boomerang federalism. In this respect, the United States stands at a critical juncture: it can accentuate fragmented governance—an expression of monocentric control and disjointed approaches—or it can pursue meta-systemic realignment, enhancing the existing mechanisms (e.g., boomerang federalism, bottom-up climate resilience initiatives, federal supportive climate policies, funding programs, etc.) and ensuring positive feedback (i.e., positive bi-directional relationship) between the federal and state levels. This realignment would involve all five layers of governance working toward coherent climate goals (Figure 4). Reestablishing alignment between federal and state perspectives does not imply uniformity, but rather systemic coherence and collaborative governance. True climate resilience is not achieved through centralization or top-down mandates alone; it requires empowering subnational actors—states, cities, and industries—as integral components of a robust polycentric system. Scientific institutions, policymakers, and resource managers have a critical role to play in facilitating this governance realignment by strengthening U.S. polycentric climate governance, fostering bottom-up resilience, and leveraging the dynamics of boomerang federalism to overcome key barriers to climate resilience (Section 4.1, Section 4.2 and Section 4.3). Moreover, the federal–state climate governance perspective desalignment affects not just the alignment across governance, policies, and goals, but also disturbs the capacities required for climate resilience by generating those barriers.

The overall research process shown in Figure 1 and described in Section 2 was designed to establish the original framing, termed perspective desalignment, as a foundation for the conceptual framework presented in Section 3. As the policies and research will continue to progress in the following years, the methodology could be applied again in the next two/three years for reassessing the evolution of the topic, the validity of the concept of perspective desalignment, and testing new analytic approaches on climate resilience and climate governance as a complex system governance or governance of SoSs. This research process permits the exploration of scientific limitations associated with the lack of secondary data in the literature, which is explained by the novelty of this research contribution and its mechanisms. To date, no studies have explicitly integrated the concepts of polycentric climate governance, climate policy, and meta-system pathologies within a unified framework. There remains a significant gap in the literature regarding the role of bottom-up resilience and climate change governance dynamics in the U.S. context. Furthermore, there is currently no empirical evidence examining boomerang federalism as a driver of polycentric climate governance in the United States. The governance discussed in this paper stops at the national level, while the emerging meta-system pathology in U.S. climate governance is a global concern that will have international implications, driven by cascading failures in countries’ climate governance structures and policies worldwide, which is still undiscovered in the existing literature.

The empirical testing of the proposed approach is out of the scope of our current efforts (i.e., out of the scope of this study). Any future empirical contribution, based on the understanding of perspective desalignment as a meta-system pathology, will have to consider all factors affecting the systemic misalignment between different-level (vertical) meta-system (governing structure) perspectives (e.g., federal and state level perspectives). In future work, we will propose variables and indicators to characterize and measure multilevel governance systems. Those variables and indicators will aim at ascertaining the divergence of intergovernmental responses in dealing with a common concern (e.g., climate concerns), the number of intergovernmental policy misalignments and conflicts, the discrepancies between different-level government funding, divergence between different-level climate policymakers’ emissions targets and standards, a cross-level coordination inefficiency index, the divergence of choices and priorities between intergovernmental stakeholders on energy actions, institutional misalignments between what law stipulates and how different-level governments operate within a country, divergence and conflicts between economic incentives to investments, etc. In summary, the focus will be on determining and evaluating the vertical mismatch, miscoordination, and misalignment between the various levels in the meta-system.

Future research will focus on empirical validation, such as practical cases (e.g., case studies for California or New York that will expand on this contribution) to confirm the concreteness of the recommendations (Section 4.1, Section 4.2 and Section 4.3), investigate how the five levels of the climate meta-system interact and influence one another and assess the strategic implications of the interactions between those five levels for the vertical structure of U.S. polycentric climate governance (Figure 4). Additional scholarly contributions are needed to illuminate the consequences of federal–state perspective desalignment, particularly its cascading effects on regional, sub-regional, municipal, and community-level governance systems.

Empirical studies are also essential to evaluate the long-term impacts of persistent systemic misalignment on national climate governance capacity. Future research should explore how bottom-up coalitions might create effective climate policies across federal and state boundaries. Moreover, attention should be given to the formation of multilevel strategic alliances—especially among scientific institutions, local governments, and civil society—as key actors operating across different climate meta-system levels. Such alliances could play a critical role in mitigating perspective desalignment and advancing more resilient and integrated climate governance frameworks.

Finally, sustained empirical inquiry is needed to understand how systemic misalignment affects long-term resource management and adaptive capability across several dimensions, including time and location (region), such as the EU (and its member states) and the African Union (and its member states). For instance, based on a recent study by Alberton [136], divergence of priorities between the EU member states on regional concerns related to climate, including energy, makes intergovernmental decision-making in climate policy increasingly complex, which urges conducting future case studies to investigate the EU polycentric climate governing system (i.e., the EU polycentric climate meta-system) and the climate perspective desalignment that may be taking or might take place between the EU institutions, regional authorities, national governments, and non-state actors (e.g., cities and non-profit organizations), and provide critical insights for supporting the EU polycentric climate governance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.H., N.P. and P.F.K.; methodology, A.H.; software, A.H.; validation, A.H., N.P., P.F.K. and M.M.; formal analysis, A.H.; investigation, A.H., N.P., P.F.K. and M.M.; resources, A.H. and N.P.; data curation, A.H.; writing—original draft preparation, A.H., N.P., P.F.K. and M.M.; writing—review and editing, A.H., N.P., P.F.K. and M.M.; visualization, A.H., N.P., P.F.K. and M.M.; supervision, A.H., N.P., P.F.K. and M.M.; project administration, A.H. and N.P.; funding acquisition, A.H. and N.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work of A. Hallioui and N. Pedroni was supported by the research project “ARtificial Intelligence and STOchasTic simulation for the rEsiLience of critical infrastructurES—ARISTOTELES” funded by MIUR—Italian Ministry for Scientific Research under the PRIN 2022 program (grant 2022TAFXZ5, CUP E53D23000960006, Grant Decree n. 716 dated 25 May 2023) and by the European Union—Next Generation EU program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely appreciate the MDPI reviewers’ time and insightful comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors are aware of no personal or financial conflicts that might have affected the research reported in this study.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| U.S. | United States |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| EU | European Union |

| SoSs | Systems of Systems |

| UOG | Oil and gas |

| DOI | Digital Object Identifier |

| GNFs | Global Normative Frameworks |

| UN | United Nations |

| UNFCCC | United Nations framework convention on climate change |

| ESG | Environmental, social, and governance |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| EPA | Environmental Protection Agency |

| DE | Department of Energy |

| NOAA | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

| FEMA | Federal Emergency Management Agency |

| CARB | California Air Resources Board |

| NGOs | Non-Governmental Organizations |

| BRIC | Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities |

References

- Jang, M.; Min, B. Stochastic Forecasting of Long-Term Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Energy Transitions: A Comparative Analysis of the US, EU, China, and Korea. Energy 2025, 327, 136376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linkov, I.; Bridges, T.; Creutzig, F.; Decker, J.; Fox-Lent, C.; Kröger, W.; Lambert, J.H.; Levermann, A.; Montreuil, B.; Nathwani, J.; et al. Changing the Resilience Paradigm. Nat. Clim. Change 2014, 4, 407–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Paris Agreement; HeinOnline: Getzville, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Fang, Y. Global Climate Governance Inequality Unveiled through Dynamic Influence Assessment. npj Clim. Action 2024, 3, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. A Polycentric Approach for Coping with Climate Change; SSRN: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Polycentric Systems for Coping with Collective Action and Global Environmental Change. Glob. Environ. Change 2010, 20, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassis, G.; Bertrand, N. Can Overarching Rules and Coordination in Polycentric Governance Help Achieve Pre-identified Institutional Goals over Time? Evidence from Farmland Governance in Southeastern France. Policy Stud. J. 2025, 53, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, V.; Tiebout, C.M.; Warren, R. The Organization of Government in Metropolitan Areas: A Theoretical Inquiry. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1961, 55, 831–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlager, E.; Olivier, T.; Cox, T.; Hanlon, J. Polycentricity and State Reinforced Self-Governance: The Case of the New York City Watersheds Governing Arrangement. Ecol. Soc. 2025, 30, art3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, T.H.; Bodin, Ö.; Cumming, G.S.; Lubell, M.; Seppelt, R.; Seppelt, T.; Weible, C.M. Building Blocks of Polycentric Governance. Policy Stud. J. 2023, 51, 475–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Beyond Markets and States: Polycentric Governance of Complex Economic Systems. Am. Econ. Rev. 2010, 100, 641–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990; ISBN 9780521371018. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E.; Gardner, R.; Walker, J. Rules, Games, and Common-Pool Resources; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1994; ISBN 9780472065462. [Google Scholar]

- Lofthouse, J. Self-Governance, Polycentricity, and Environmental Policy; SSRN Electronic Journal: Rochester, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabe, B.; Smith, H. Climate Governance and Federalism in the United States. In Climate Governance and Federalism; Fenna, A., Jodoin, S., Setzer, J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023; pp. 306–327. [Google Scholar]

- Nix, P.; Goldstein, A.; Oppenheimer, M. Models of Sub-National U.S. Quasi-Governmental Organizations: Implications for Climate Adaptation Governance. Clim. Change 2024, 177, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellner, E.; Petrovics, D.; Huitema, D. Polycentric Climate Governance: The State, Local Action, Democratic Preferences, and Power—Emerging Insights and a Research Agenda. Glob. Environ. Polit. 2024, 24, 24–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A.J.; Huitema, D.; Hildén, M.; van Asselt, H.; Rayner, T.J.; Schoenefeld, J.J.; Tosun, J.; Forster, J.; Boasson, E.L. Emergence of Polycentric Climate Governance and Its Future Prospects. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 977–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordaan, S.M.; Davidson, A.; Nazari, J.A.; Herremans, I.M. The Dynamics of Advancing Climate Policy in Federal Political Systems. Environ. Policy Gov. 2019, 29, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huitema, D.; Mostert, E.; Egas, W.; Moellenkamp, S.; Pahl-Wostl, C.; Yalcin, R. Adaptive Water Governance: Assessing the Institutional Prescriptions of Adaptive (Co-)Management from a Governance Perspective and Defining a Research Agenda. Ecol. Soc. 2009, 14, art26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasser, P.; Lustenberger, P.; Cinelli, M.; Kim, W.; Spada, M.; Burgherr, P.; Hirschberg, S.; Stojadinovic, B.; Sun, T.Y. A Review on Resilience Assessment of Energy Systems. Sustain. Resilient Infrastruct. 2021, 6, 273–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aven, T. On Some Recent Definitions and Analysis Frameworks for Risk, Vulnerability, and Resilience. Risk Anal. 2011, 31, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haimes, Y.Y. On the Definition of Resilience in Systems. Risk Anal. 2009, 29, 498–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulu, K.; Ezeani, E.; Salimi, Z.; Simenti-Phiri, E.; Chunga, C.K.; Musanda, P.; Halwiindi, P. Determinants of Effective Participatory Multi-Actor Climate Change Governance: Insights from Zambia’s Environment and Climate Change Actors. Environ. Sci. Policy 2025, 167, 104040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katina, P.F.; Gheorghe, A.V. Blockchain-Enabled Resilience: An Integrated Approach for Disaster Supply Chain and Logistics Management, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; ISBN 9781003336082. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley Biggs, N.; Hafner, J.; Mashiri, F.E.; Huntsinger, L.; Lambin, E.F. Payments for Ecosystem Services within the Hybrid Governance Model: Evaluating Policy Alignment and Complementarity on California Rangelands. Ecol. Soc. 2021, 26, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.; Iacobuta, G.; Hägele, R. Maximising Goal Coherence in Sustainable and Climate-Resilient Development? Polycentricity and Coordination in Governance. In The Palgrave Handbook of Development Cooperation for Achieving the 2030 Agenda; Chaturvedi, S., Janus, H., Klingebiel, S., Li, X., de Mello e Souza, A., Sidiropoulos, E., Wehrmann, D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 25–50. [Google Scholar]

- Beheshtian, A.; Donaghy, K.P.; Richard Geddes, R.; Oliver Gao, H. Climate-Adaptive Planning for the Long-Term Resilience of Transportation Energy Infrastructure. Transp. Res. E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2018, 113, 99–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selva, J.; Tonini, R.; Molinari, I.; Tiberti, M.M.; Romano, F.; Grezio, A.; Melini, D.; Piatanesi, A.; Basili, R.; Lorito, S. Quantification of Source Uncertainties in Seismic Probabilistic Tsunami Hazard Analysis (SPTHA). Geophys. J. Int. 2016, 205, 1780–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, M.; Dueñas-Osorio, L. Multi-Dimensional Hurricane Resilience Assessment of Electric Power Systems. Struct. Saf. 2014, 48, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, M.; Dueñas-Osorio, L. Time-Dependent Resilience Assessment and Improvement of Urban Infrastructure Systems. Chaos Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci. 2012, 22, 033122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, M.; Dueñas-Osorio, L.; Min, X. A Three-Stage Resilience Analysis Framework for Urban Infrastructure Systems. Struct. Saf. 2012, 36–37, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldschmeding, F.; Kemp, R.; Vasseur, V.; Scholl, C. Institutional Logics as an Object of Change: The Experiences of a Water Organization Using Design Thinking for Climate Adaptation in a Multi-Stakeholder Process. Sustain. Sci. 2025, 20, 759–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, T.; Hossain Lipu, M.S.; Alom Shovon, M.M.; Alsaduni, I.; Karim, T.F.; Ansari, S. Unveiling the Impacts of Climate Change on the Resilience of Renewable Energy and Power Systems: Factors, Technological Advancements, Policies, Challenges, and Solutions. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 493, 144933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremer, S.; Glavovic, B.; Meisch, S.; Schneider, P.; Wardekker, A. Beyond Rules: How Institutional Cultures and Climate Governance Interact. WIREs Clim. Change 2021, 12, e739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrick, C.; Vogel, J. Climate Adaptation at the Local Scale: Using Federal Climate Adaptation Policy Regimes to Enhance Climate Services. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, J.L. State-Level Influences on Community-Level Municipal Sustainable Energy Policies. Urban. Aff. Rev. 2022, 58, 1065–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Climate Pollution Reduction Grants. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/inflation-reduction-act/climate-pollution-reduction-grants (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Internal Revenue Service Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. Available online: https://www.irs.gov/inflation-reduction-act-of-2022?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Trachtman, S. Building Climate Policy in the States. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 2019, 685, 96–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karch, A.; Rose, S. States as Stakeholders: Federalism, Policy Feedback, and Government Elites. Stud. Am. Political Dev. 2017, 31, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulder, L.; Stavins, R. Interactions between State and Federal Climate Change Policies; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, J.; Taminiau, J.; Nyangon, J. American Policy Conflict in the Hothouse: Exploring the Politics of Climate Inaction and Polycentric Rebellion. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 89, 102551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karapin, R. Federalism as a Double-Edged Sword: The Slow Energy Transition in the United States. J. Environ. Dev. 2020, 29, 26–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Q. What Affects Government Planning for Climate Change Adaptation: Evidence from the U.S. States. Environ. Policy Gov. 2019, 29, 376–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraembs, T.V.; Drobnič, S. Ill-Informed or Ideologically Driven? Climate Change Awareness and Denial in Europe. Popul. Environ. 2024, 46, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, R.K. Climate Adaptation Law and Policy in the United States. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 1059734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M. Governing the Global Climate Commons: The Political Economy of State and Local Action, after the U.S. Flip-Flop on the Paris Agreement. Energy Policy 2018, 118, 440–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trump Issues Order to Block State Climate Change Policies. Reuters 2025. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/climate-energy/trump-issues-order-block-state-climate-change-policies-2025-04-09/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- The White House Protecting American Energy from State Overreach. Available online: https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/04/protecting-american-energy-from-state-overreach/ (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Katina, P.F.; Omolo, B.; Adebiaye, R.; Hallioui, A. Systems theory-based framework for discovery and classification of metasystemic pathologies in engineered complex systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Annual Conference and 45th Annual Meeting: Engineering Management Riding the Waves of Smart Systems, ASEM 2024, Virginia Beach, VI, USA, 6–9 November 2024; pp. 231–241. [Google Scholar]

- Katina, P.F. Metasystem Pathologies in Complex System Governance. In Complex System Governance: Theory and Practice; Keating Charles, B., Katina, P.F., Chesterman, C.W., Jr., Pyne, J.C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 241–282. ISBN 978-3-030-93852-9. [Google Scholar]

- Katina, P.F.; Keating, C.B.; Zio, E.; Masera, M.; Gheorghe, A.V. Governance of Smart Energy Systems. In Handbook of Smart Energy Systems; Fathi, M., Zio, E., Pardalos, P.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–20. ISBN 978-3-030-72322-4. [Google Scholar]

- Katina, P.F.; Keating, C.B.; Bradley, J.M. The Role of “metasystem” in Engineering a System of Systems. In Proceedings of the 2016 Industrial and Systems Engineering Research Conference, ISERC 2016, Anaheim, CA, USA, 21–24 May 2020; pp. 829–834. [Google Scholar]

- Keating, C.B.; Katina, P.F.; Bradley, J.M. Complex System Governance: Concept, Challenges, and Emerging Research. Int. J. Syst. Syst. Eng. 2014, 5, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, S. Brain of the Firm: The Managerial Cybernetics of Organizations, 2nd ed.; Wiley: New Jersey, NJ, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Katina, P.F. Metasystem Pathologies (M-Path) Method: Phases and Procedures. J. Manag. Dev. 2016, 35, 1287–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebestyén, V.; Czvetkó, T.; Abonyi, J. The Applicability of Big Data in Climate Change Research: The Importance of System of Systems Thinking. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 619092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katina, P.F.; Keating, C.B.; Bobo, J.A.; Toland, T.S. A Governance Perspective for System-of-Systems. Systems 2019, 7, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednar, J.; Page, S.E. Institutions and Cultural Capacity: A Systems Perspective. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2025, 234, 106990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deslatte, A.; Helmke-Long, L.; Stokan, E.; Chung, J. Economies of Inequality? Polycentric Metropolitan Governance and Strategic Sustainability Choices. Urban. Aff. Rev. 2025, 61, 315–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Anwer, N.; Mahapatra, K.; Shrivastava, M.K.; Khatiwada, D. Analyzing the Role of Polycentric Governance in Institutional Innovations: Insights from Urban Climate Governance in India. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley, D.M.; Abel, T.D.; Stephan, M.; Rai, S.; Rogers, E. Can Polycentric Governance Lower Industrial Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Evidence from the United States. Environ. Policy Gov. 2024, 34, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lofthouse, J.K.; Herzberg, R.Q. The Continuing Case for a Polycentric Approach for Coping with Climate Change. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Pei, X. Polycentric Governance and Resilience Enhancement for Mountain Landscapes in Metropolitan Areas: The Case of the Santa Monica Mountains, the Usa. Landsc. Archit. Front. 2019, 7, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D.H. Advantages of a Polycentric Approach to Climate Change Policy. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereverza, K.; Rohracher, H.; Kordas, O. Fostering Urban Climate Transition Through Innovative Governance Coordination. Environ. Policy Gov. 2025, 35, 631–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welton, S. Rethinking Grid Governance for the Climate Change Era. Calif. Law. Rev. 2021, 109, 209–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazmanian, D.A.; Jurewitz, J.L.; Nelson, H.T. State Leadership in U.S. Climate Change and Energy Policy: The California Experience. J. Environ. Dev. 2020, 29, 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyrs, T.H. Enabling Renewable Energy on Both Sides of the Meter: A Focus on State-Level Approaches in New York and Texas. Curr. Sustain. Renew. Energy Rep. 2018, 5, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graff, M.; Carley, S.; Konisky, D.M. Stakeholder Perceptions of the United States Energy Transition: Local-Level Dynamics and Community Responses to National Politics and Policy. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 43, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Matisoff, D.C. Advanced Metering Infrastructure Deployment in the United States: The Impact of Polycentric Governance and Contextual Changes. Rev. Policy Res. 2016, 33, 646–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryder, S.; Malin, S.A. ‘The System Is Engineered to Do This’: Multilevel Disempowerment and Climate Injustice in Regulating Colorado’s Oil and Gas Development. Soc. Probl. 2024, spae038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanson, A.V.; Masten, A.S. Climate Change and Resilience: Developmental Science Perspectives. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2024, 48, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Moser, S. Transformative Climate Adaptation in the United States: Trends and Prospects. Science 2021, 372, eabc8054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serra-Llobet, A.; Conrad, E.; Schaefer, K. Governing for Integrated Water and Flood Risk Management: Comparing Top-Down and Bottom-Up Approaches in Spain and California. Water 2016, 8, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, D.R. Understanding the Relationship between Subnational and National Climate Change Politics in the United States: Toward a Theory of Boomerang Federalism. Environ. Plann C Gov. Policy 2013, 31, 769–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallioui, A.; Herrou, B.; Katina, P.F.; Santos, R.S.; Egbue, O.; Jasiulewicz-Kaczmarek, M.; Soares, J.M.; Marques, P.C. A Review of Sustainable Total Productive Maintenance (STPM). Sustainability 2023, 15, 12362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallioui, A.; Herrou, B.; Santos, R.S.; Katina, P.F.; Egbue, O. Systems-Based Approach to Contemporary Business Management: An Enabler of Business Sustainability in a Context of Industry 4.0, Circular Economy, Competitiveness and Diverse Stakeholders. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 373, 133819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H. Literature Review as a Research Methodology: An Overview and Guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. Bibliometrix: An R-Tool for Comprehensive Science Mapping Analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deslatte, A.; Siciliano, M.D.; Krause, R.M. Local Government Managers Are on the Frontlines of Climate Change: Are They Ready? Public. Adm. Rev. 2023, 83, 1506–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meckling, J.; Trachtman, S. The Home State Effect: How Subnational Governments Shape Climate Coalitions. Governance 2024, 37, 887–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopper, J.S.; Swift, C.S. Considering Subnational Support of Climate Change Policy in the United States and the Implications of Symbolic Policy Acts. Environ. Politics 2022, 31, 969–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software Survey: VOSviewer, a Computer Program for Bibliometric Mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, P.; Spataru, C. Gaps in the Governance of Floods, Droughts, and Heatwaves in the United Kingdom. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1124166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dug, C.; Natoli, T. Coherence, Alignment and Integration: Understanding the Legal Relationship Between Sustainable Development, Climate Change Adaptation and Disaster Risk Reduction. In Creating Resilient Futures: Integrating Disaster Risk Reduction, Sustainable Development Goals and Climate Change Adaptation Agendas; Flood, S., Le Tissier, M., Columbié, Y.J., O’Dwyer, B., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 45–64. ISBN 978-3-030-80791-7. [Google Scholar]

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development 2018: Towards Sustainable and Resilient Societies; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018; ISBN 9789264301054. [Google Scholar]

- Collste, D.; Pedercini, M.; Cornell, S.E. Policy Coherence to Achieve the SDGs: Using Integrated Simulation Models to Assess Effective Policies. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 12, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, J.; Lang, A. Policy Integration: Mapping the Different Concepts. Policy Stud. 2017, 38, 553–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, M. Mission Impossible: The European Union and Policy Coherence for Development. J. Eur. Integr. 2008, 30, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, M.G.; Payne, I. The Concept and Uses of Hourglass Federalism: A Comparative Study. Reg. Fed. Stud. 2025, 35, 257–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinen, D.; Arlati, A.; Knieling, J. Five Dimensions of Climate Governance: A Framework for Empirical Research Based on Polycentric and Multi-level Governance Perspectives. Environ. Policy Gov. 2022, 32, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.S.; Rosendo, S.; Sadasing, O.; Celliers, L. Identifying Local Governance Capacity Needs for Implementing Climate Change Adaptation in Mauritius. Clim. Policy 2020, 20, 548–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubell, M.; Robbins, M. Adapting to Sea-Level Rise: Centralization or Decentralization in Polycentric Governance Systems? Policy Stud. J. 2022, 50, 143–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillard, R.; Gouldson, A.; Paavola, J.; Van Alstine, J. Can National Policy Blockages Accelerate the Development of Polycentric Governance? Evidence from Climate Change Policy in the United Kingdom. Glob. Environ. Change 2017, 45, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, T.; Miedema, M. A Governance Approach to Regional Energy Transition: Meaning, Conceptualization and Practice. Sustainability 2020, 12, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, L.; Hesselman, M. Governing Disasters: Embracing Human Rights in a Multi-Level, Multi-Duty Bearer, Disaster Governance Landscape. Politics Gov. 2017, 5, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.E.; Koebele, E.A. Coordinating School Improvement: Understanding the Impact of State Implementation Approach on Coordination in Multilevel Governance Systems. Rev. Policy Res. 2025, 42, 188–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congressional Research Service. Federalism and the Constitution. Available online: https://constitution.congress.gov/browse/essay/intro.7-3/ALDE_00000032/ (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- U.S. Supreme Court. Bond v. United States; U.S. Supreme Court: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; Volume 572, p. 844. [Google Scholar]

- Pappas, M. The Structure of U.S. Climate Policy. Md. Law. Rev. 2024, 83, 347. [Google Scholar]

- Rabe, B. Contested Federalism and American Climate Policy. Publius J. Fed. 2011, 41, 494–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, N.; Litz, F.; Saha, D.; Clevenger, T.; Lashof, D. New Climate Federalism: Defining Federal, State, and Local Roles in a U.S. Policy Framework to Achieve Decarbonization. World Resour. Inst. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trachtman, S.; Inal, I.; Meckling, J. Building Winning Climate Coalitions: Evidence from U.S. States. Energy Policy 2025, 203, 114628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Climate Alliance U.S. Climate Alliance. Available online: https://usclimatealliance.org/ (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Strange, K.F.; Satorras, M.; March, H. Intersectional Climate Action: The Role of Community-Based Organisations in Urban Climate Justice. Local. Environ. 2024, 29, 865–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Justice United States; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency v. State of Vermont. Complaint for Declaratory and Injunctive Relief. Civil Action No. 2:25-cv-463. 2025. Available online: https://www.justice.gov/opa/media/1398811/dl?inline=&utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- U.S. Department of Justice United States; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency v. State of New York. Complaint for Declaratory and Injunctive Relief. Civil Action No. 1:25-Cv-03656. 2025. Available online: https://www.justice.gov/opa/media/1398816/dl?inline (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Goelzhauser, G.; Konisky, D.M. The State of American Federalism 2019–2020: Polarized and Punitive Intergovernmental Relations. Publius J. Fed. 2020, 50, 311–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howlett, M.; Ramesh, M. The Two Orders of Governance Failure: Design Mismatches and Policy Capacity Issues in Modern Governance. Policy Soc. 2014, 33, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkland, T.A.; Taylor, K.; Crow, D.A.; DeLeo, R. Governing in a Polarized Era: Federalism and the Response of U.S. State and Federal Governments to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Publius J. Fed. 2021, 51, 650–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolini, M.; Valdesalici, A. (Eds.) Local Governance in Multi-Layered Systems: A Comparative Legal Study in the Federal-Local Connection, 1st ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 108, ISBN 978-3-031-41791-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kissinger, H. World Order, Paperback ed.; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hooghe, L.; Marks, G. A Postfunctionalist Theory of European Integration: From Permissive Consensus to Constraining Dissensus. Br. J. Political Sci. 2009, 39, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larousse French-English/English-French Translator. Available online: https://www.larousse.fr/traducteur (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Lahmar, M.; Frihi, D.; Nicolas, D. The Effect of Misalignment on Performance Characteristics of Engine Main Crankshaft Bearings. Eur. J. Mech. A/Solids 2002, 21, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gede, D.U.; Huluka, A.T. The Impact of Strategic Alignment on Organizational Performance: The Case of Ethiopian Universities. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2247873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elia, S.; Larsen, M.M.; Piscitello, L. Choosing Misaligned Governance Modes When Offshoring Business Functions: A Prospect Theory Perspective. Glob. Strategy J. 2023, 13, 251–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, J.R.; Kemp, D.; Schuele, W.; Loginova, J. Misalignment between National Resource Inventories and Policy Actions Drives Unevenness in the Energy Transition. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P.A. Policy Paradigms, Social Learning, and the State: The Case of Economic Policymaking in Britain. Comp. Polit. 1993, 25, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, F.; Jones, B. Agendas and Instability in American Politics, 2nd ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009; ISBN 0226039498. [Google Scholar]

- Howlett, M.; Ramesh, M.; Perl, A. Studying Public Policy: Principles and Processes, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020; ISBN 0199026149. [Google Scholar]

- Milinski, M.; Marotzke, J. Economic Experiments Support Ostrom’s Polycentric Approach to Mitigating Climate Change. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2022, 9, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radtke, J. Understanding the Complexity of Governing Energy Transitions: Introducing an Integrated Approach of Policy and Transition Perspectives. Environ. Policy Gov. 2025, 35, 595–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mango, F.; Vincent, R.C. Does Polycentric Climate Governance Drive the Circular Economy? Evidence from Subnational Spending and Dematerialization of Production in the EU. Ecol. Econ. 2025, 231, 108533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, R.; Xu, P. Time-Varying Spillover Effects Between Clean and Traditional Energy Under Multiple Uncertainty Risk: Evidence from the U.S. Market. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrizio, K.R. The Effect of Regulatory Uncertainty on Investment: Evidence from Renewable Energy Generation. J. Law. Econ. Organ. 2013, 29, 765–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Maio, F.; Pedroni, N.; Taroni, M.; Zio, E. ARtificial Intelligence and STOchasTic Simulation for the REsiLience of Critical InfrastructurES (ARISTOTELES). In Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Conference on System Reliability and Safety (ICSRS), Sicily, Italy, 20–22 November 2024; pp. 482–486. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffart, F.M.; D’Orazio, P.; Holz, F.; Kemfert, C. Exploring the Interdependence of Climate, Finance, Energy, and Geopolitics: A Conceptual Framework for Systemic Risks amidst Multiple Crises. Appl. Energy 2024, 361, 122885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Sang, S.; Tiwari, A.K.; Khan, S.; Zhao, X. Impacts of Renewable Energy on Climate Risk: A Global Perspective for Energy Transition in a Climate Adaptation Framework. Appl. Energy 2024, 362, 122994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.K.; Park, S. Impacts of Renewable Energy on Climate Vulnerability: A Global Perspective for Energy Transition in a Climate Adaptation Framework. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 859, 160175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basseches, J.A.; Bromley-Trujillo, R.; Boykoff, M.T.; Culhane, T.; Hall, G.; Healy, N.; Hess, D.J.; Hsu, D.; Krause, R.M.; Prechel, H.; et al. Climate Policy Conflict in the U.S. States: A Critical Review and Way Forward. Clim. Change 2022, 170, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilgers, M.; McCuskey, J.B.; Marshall, S.; Griffin, T.; Uthmeier, J.; Carr, C.; Bird, B.; Kobach, K.; Coleman, R. Letter to the U.S. Department of Justice on Energy Actions; U.S. Department of Justice: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, N.; Russo, S.; Burtraw, D. Considerations for Washington’s Linkage Negotiations with California and Québec; Resources for the Future: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Alberton, M. Climate Governance and Federalism in the European Union. In Climate Governance and Federalism; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023; pp. 128–149. [Google Scholar]