Abstract

Super-utilization, defined as frequent and often avoidable use of emergency departments and hospital admissions, has attracted significant policy and research attention due to its impact on healthcare costs. Over the past decade, care management and integrated care interventions have been promoted as solutions to reduce per capita expenditure and service use. However, systematic reviews and primary studies consistently report limited success in shifting utilization patterns or improving care experiences. This narrative review based upon critical systems heuristics explores the conceptual evolution of super-utilization and examines whether current approaches reflect the underlying complexity of the health system and patient needs. The three-phase narrative and complexity-informed review aimed to identify the evolution of Super-utilization as an issue and its key drivers, in relation to the dynamic systems in which it occurs. The findings reveal a predominant emphasis on cost containment and acute care metrics, with minimal incorporation of person-centered outcomes, lived experience, or local system dynamics. Even when addressing social determinants, interventions remain narrowly focused on utilization and/or costs as the key outcome. Super-utilization or High-Need/High-Cost trajectories reflect multi-level dynamics—biological, psychological, social, and political—yet these are rarely integrated into program design or evaluation. Centralized policy frameworks such as the Triple Aim risk reinforce inequities unless they actively address under-resourced populations and the complexity of chronic illness and ageing. Radical transformation of policy is required to make the nature of care of high-cost/high-need super-utilizers central to quality metrics that may improve outcomes rather than inappropriate utilization metrics which make little impact on healthcare costs. This review concludes that super-utilization requires a shift in paradigm toward systems-informed, needs-based approaches that integrate complexity theory and distributive justice to guide future research and interventions.

1. Introduction

Internationally, Super-utilization of acute hospital services represents frequent hospital emergency department utilization and frequent acute readmissions for a small percentage of the population. The terms Super-utilizer and Super-utilization are used as a shorthand term to encompass perceived high levels of use of acute hospital services that are deemed to be expensive. Acute care in hospitals represents systems which are open to individuals seeking care which often reflect unmet individual needs driven by complex influences transcending hospital settings and even health systems. This is viewed as a crisis of inefficient use of hospital resources for conditions by individuals (frequent flyers, repeat admitters) that could be more effectively and efficiently managed elsewhere.

Is the reduction of per capita costs of frequent users amenable to predominant care management models? What reconfigurations will improve the meeting of individual needs as a complex phenomenon influenced by numerous interconnected factors? Will focusing on social determinants of health and population aging, and improving population health reduce Super-utilization?

The intersection of value for money and reducing healthcare costs per capita with the emergence and evolution of super-utilization, system transformation, and care management are multiple streams of policy that have intersected since the late 20th Century. Super-utilization was deemed to be a source of patients with above average utilization or costs [1,2]. This prompted healthcare systems to explore strategies for managing high-utilization patients more effectively.

However, to date, there is evidence that care management interventions and system transformation efforts to improve Super-utilization have limited success in shifting either utilization or costs [3] particularly where social determinants of health and aging populations are key drivers [4]. Traditional care management models have struggled to effectively address super-utilization. Holistic, long-term solutions are increasingly called for that recognize the importance of addressing social determinants of health and population aging in tackling this frequent acute care utilization. Yet there has been little attention to the phenomena of Super-utilization representing a complex phenomenon influenced by numerous interconnected components ranging from individual care seeking, community resources, and health service dynamics [5].

This review is exploratory, narrative-based, system-mapping, and concept-evolving—because the research questions are “what is going on here, and how did this evolve?” This contrasts with traditional research questions built for hypothesis-driven, intervention-focused, or causal inference studies. These questions reflect the dual aims of mapping the conceptual evolution of “super-utilization” and interrogating how it has been framed, measured, and addressed across policy and practice. The questions emerged iteratively through engagement with foundational literature, keyword refinement, and systems-mapping, consistent with critical systems-thinking approaches to health systems evaluation [6]. Critical systems heuristics (CSH) ask ‘what are the underlying assumptions—values, power structures, knowledge bases, and moral stances—which affect how a situation is perceived?’ [7] CSH is not a ‘prescribed methodology’ with step-by-step directions of standard best practices, but instead a framework to encourage reflection [7].

The following questions are addressed in this paper: What is ‘Super-utilization’ and how it has been framed in the literature over time, and what underlying assumptions have guided its framing? What types of interventions have been implemented to reduce Super-utilization, and how effective are they in shifting utilization patterns, improving patient outcomes, and addressing social determinants of health? To what extent do existing interventions and evaluations incorporate systems-thinking, complexity theory, and the lived experience of high-need, high-cost populations reflecting distributive justice? How would complexity-informed models of care move toward improved equity and patient-centered outcomes in high-need/high-cost populations?

2. Materials and Methods

A narrative review of the nature of Super-utilization was conducted in three stages with a synthesis commencing in March 2021.

The project began with the observed problem of super-utilization and repeated reports of “failed” interventions—programs where clinicians and researchers perceived improvements for high-need patients without corresponding shifts in conventional utilization metrics. This prompted an inductive exploration of the literature, rather than a theory-driven protocol, to understand the framing and evolution of “super-utilization” as a construct across health systems. Because patterns of heavy acute care use have been framed through differing policy, payment, and quality lenses over time, the review first traced how the concepts in healthcare have been socially produced within health systems discourse, research, and policy. I then developed a brief scan of key and foundational articles which were presented to a workshop as co-chair of the Working Group of the North American Primary Care Research Group (NAPCRG), Committee on the Science of Family Medicine [8].

Building on workshop feedback, I employed a multi-phase, CSH-informed narrative methodology to explore how super-utilization has been conceptualized, constructed, and operationalized across health systems literature. The strategy used repeated cycles of keyword refinement and snowball sampling. Initial “seed codes” for super-utilization-related terms were drawn from early policy and research documents and then expanded through immersion in the literature [9,10,11]. Open coding of retrieved articles identified and grouped related concepts. Codes were refined and clustered into broader themes [12]. Codes were linked into conceptual groups and frequency analyses guided prioritization. Conceptual saturation was monitored iteratively [13,14].

Only after the thematic analysis was complete did the study explicitly draw on a formal theoretical framework. Critical Systems Heuristics [6,7] was identified as the most appropriate lens for interpreting and justifying the approach post hoc. CSH’s emphasis on boundary critique, stakeholder perspectives, and value-laden assumptions resonated with the findings of this review and with the reflexive, iterative coding process already undertaken. This framework helped contextualize the implicit assumptions embedded in how super-utilization is framed, measured, and evaluated in literature and policy.

Given the heterogeneity of interventions and definitions associated with high-need, high-cost patients, the review adopted a transdisciplinary systems lens to examine four interrelated domains:

- -

- Phase 1: The historical emergence of super-utilization as a policy and analytic construct.

- -

- Phase 2: The thematic patterns arising from systematic search strategies using utilization-related terminology.

- -

- Phase 3: The typologies of care management interventions and their systems-level characteristics.

- -

- Phase 4: A synthesis phase integrating review findings with a complex-systems and CSH perspective.

Each domain used complementary search strategies and analytic approaches, with iterative movement across phases as the field evolved. Table 1 provides an overview of the phases, research questions, and literature lenses, and Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7 present the data summaries and supporting analyses for each stage.

Table 1.

Phase of the review with research questions, analytic focus, and literature lens.

In Phase 1, I traced the historical emergence of super-utilization and related policy responses by identifying key foundational texts and milestone studies, supported by the NAPCRG reference group [8]. Secondly, I performed a structured narrative search to characterize the dominant themes and frequency of key terms across indexed literature using utilization-related search strategies. Thirdly, I reviewed care management and intervention typologies, synthesizing how these models have addressed—or failed to address—systemic complexity, social needs, and patient-centered outcomes. Finally, a synthesis offers a systems-informed lens [15] through which to interpret the persistence and evolution of super-utilization interventions across health systems, and their nonalignment with principles of improving quality of care.

2.1. Phase 1: Historical Emergence

I first conducted a snowball sample of grey and peer-reviewed literature from key policy initiatives, program documents, and empirical studies that shaped the emergence of “super-utilization” in health systems discourse. This phase emphasized key inflection points in policy, terminology, and conceptual framing, including landmark U.S. and International initiatives from 2000–2011.

2.2. Phase 2: Narrative Search of Utilization Terminology and Constructs 2012–2024

2.2.1. Initial Key Papers for the Snowball Sample

Emerged from Group Discussions in a workshop held by the complexity science working group of the North American Primary Care Research Group, Committee on the Science of Family Medicine in 2022 [16]. The Working Group met regularly every month by videocall and provided ongoing feedback which led to the development of a list of key foundational texts as a starting point for an historical scanning and terminological and thematic narrative outlined in Table 2 in Section 3.

2.2.2. Snowball Sampling

I conducted a snowball sample beginning from the key articles to generate key terms for a structured search to characterize the breadth and dominant themes in the literature. A structured PubMed search was conducted using Boolean search terms related to super-utilization, including “super-utilizer”, “frequent flyer”, “readmission prevention”, and “high-cost/high-need.” Filters were applied to limit results to Clinical Trials, Randomized Controlled Trials, Systematic Reviews, and Meta-Analyses published between 2012 and 2024. Term selection was performed iteratively through initial seed terms drawn from foundational literature and validated through repeated search refinement, frequency mapping, and manual clustering. While no automated topic modeling or n-grams were used in this review, the core thematic groupings were stable across lexical variants.

2.2.3. Searching Strategy and Thematic Review

Across iterations, the principal PubMed query (1 January 2012–30 March 2024) returned ~34,000 records tagged to one or more super-utilization–related terms; ~3690 were indexed in the most recent 12-month interval (to 30 March 2024). Automated PubMed publication-type tags within the broader corpus included 806 RCTs, 1206 clinical trials, 36 narrative reviews, and 779 systematic reviews. (Counts fluctuated modestly across repeat queries because of database updates and indexing drift; see Section 3.3). Additional filtering by qualitative methods and case studies was applied to capture less visible implementation insights. The search strategy and results are summarized in Table 3 and Table 4.

To examine how emphases differed by perspective, I ran companion searches oriented toward (a) individual-focused identifiers (Superutilizer terms; Table 3) and (b) provider/management perspectives (Care Management terms; Table 4). A fourth query added mixed-methods and qualitative filters to better capture experiential literature.

2.3. Phase 3: Typology and Systems Framing of Care Management Models

The third phase investigated the taxonomy of care management and intervention models targeting high-utilization populations. This included a structured PubMed search using terms such as “care coordination”, “integrated care”, “primary care”, and “case management”, in combination with utilization outcomes. I further analyzed the representation of concepts such as quality of life, social determinants, system complexity, and predictive analytics. A typology was developed from this sample to identify patterns across intervention types, contextual features, and systems behaviors (Table 5 and Table 6).

2.4. Phase 4: Synthesis: Emergent Patterns in the Context of Systemic Complexities

This multi-phase methodology enabled triangulation of policy, empirical, and conceptual insights into a unified systems-based understanding of super-utilization in healthcare. The first 3 sections identified the key attractors and drivers of Super-utilization interventions which are interrogated in this section in the context of a systems model.

Acute care is demonstrably a complex system [17,18]. A complex system has so many interacting parts that it is difficult, if not impossible, to influence the behavior of the system based on interventions in its component parts. Superutilization (frequent use) follows the expected pareto distribution 80:20-rule of acute hospital utilization metrics. Complex systems exhibit non-linearity driven by attractors—individuals in their social contexts, services, and policies do not follow normal distributions [18,19].

3. Results

The findings of this review are presented in three interrelated domains, corresponding to the analytic phases outlined above. Each subsection includes a synthesis of the key concepts, frequency of thematic representation, and emergent patterns that reflect how super-utilization has been framed, implemented, and critiqued within the literature. Synthesis reflects the emergent nature of the Super-utilization phenomena and how its priorities are misaligned with the evidence and an understanding of complex system phenomena.

3.1. How Has the Concept of Super-Utilization Emerged in Policy and Academic Discourse, and What Foundational Paradigms Have Shaped It?

This section examines the origin and diffusion of the term “super-utilizer” and related constructs, identifying the key actors, policies, and assumptions embedded in their use (Table 1).

Historical papers included The World Bank Development Report, 1993 [20], OECD [21,22], Getting More for the Dollar [22], Kaiser Permanente 2002 [23], and the World Health Organization Report, 2004 [24]. Other landmark articles included the Super-utilizer Summit [25], and the Triple Aim 2008 [26], the role of the hospital in a changing environment [27], and Blueprints for Complex Care [28]. The themes of these papers emerged as the context of the term, Super-utilizer, with the earliest published use of the term by Jiang et al. in 2012 [1,2].

A pivotal policy and practice driver was the U.S. Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) [29], launched 1 October 2012. This Medicare value-based purchasing initiative intended to strengthen communication and coordination, to better engage patients and caregivers, in discharge planning, and integrate providers in enhanced care management activities to reduce avoidable read-missions [30,31]. In the fragmented U.S. delivery system, HRRP and contemporary Accountable Care initiatives aimed to link economic efficiency with quality improvement efforts and elevated acute care utilization (readmissions; ED attendances) as high-visibility performance benchmarks. Parallel quality agendas in OECD countries similarly adopted avoidable admissions as an indicator of system performance [32]; wider efficiency dashboards expanded these metrics to include hospital readmissions, ED use, and total health expenditure per capita across high-, middle-, and low-income settings [33].

The term hotspotting, in relation to super-utilizer or high-cost patient interventions, appears to have entered the health services literature in the early 2010s, particularly through the Camden Coalition’s work in Camden, New Jersey. Public attention via Atul Gawande’s “The Hot Spotters” (2011) [34] helped define the concept: using data to locate patients with outsize healthcare utilization and deploying targeted interventions. By 2014–2015, the term is being used regularly in program descriptions and evaluations, especially in U.S.-based pilot studies of programs modeled on Camden’s approach [35].

The term “high-need, high-cost” appears to crystallize circa 2015–2016 in U.S.-based Commonwealth Fund policy/research documents [36], and afterward in peer-reviewed studies [3]. International adoption of the paired term seems to lag, with many studies outside the U.S. using related but distinct terms either high-cost or high-need. Formal peer-reviewed academic adoption of the composite label appear only later [37]. International literature tends to use ‘high-need’ or ‘high-cost’ separately or together [38,39], along with other framing terms (e.g., frequent user, repeat readmitters, complex needs, super-utilizer) [40,41,42] as these terms persist in the literature.

Consolidation and Reassessment: 2019–2024

Subsequent evaluative syntheses moderated earlier expectations. A systematic review and realist synthesis from the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) reported small–moderate effects on utilization and minimal impact on costs across heterogeneous interventions targeting high users [3,43]. Case management approaches improved care coordination and linkage with primary care but generally did not translate into robust outcome gains [44,45,46,47]. Commentators noted a growing disillusionment with the limited ability to bend utilization curves despite substantial investment [48]. This prompted a turn toward impactability questions—what works, for whom, and under what conditions—and toward examining patient engagement as a prerequisite for benefit. A re-analysis of the Camden Coalition Hotspotting trial [44] suggested that individuals with comparatively less disrupted lives who are able (and willing) to participate derived greater benefit, raising foundational questions about program targeting and aims to improve outcomes for the most disadvantaged [49]. Trials may have improved care coordination [50], that is improvements in integrated care, yet did not demonstrate any improvements in quality of life or experiences of care. The Camden and other hotspotting programs in the US have persisted attempting to improve quality of care for vulnerable individuals in areas of socio-economic depravation without demonstrating improvements in utilization metrics [35]. Integrated care models, prioritizing comprehensive and coordinated care delivery, saw growing implementation despite mixed findings [51,52,53]. In parallel, deep-end practices in Scotland and other variations internationally reflect the bottom-up community centric approaches to address health inequities in ‘deprived’ communities without substantial cost shifts being demonstrated [54]. Hospital readmission prevention remains a focus of quality initiatives in the US and internationally [55].

There has been a move to person-centric end of life care with a shift reducing admissions in the last years of life (last 180 days) in OECD countries and beyond. There are many initiatives in place yet, to date, little evidence that there have been successes in terms of cost containment or quality [56]. There is considerable confusion in this space.

Clinical inappropriateness and system barriers to community care are separate, as they require distinct solutions. Society must provide accessible community care options and train staff to support terminally ill patients outside hospitals. This foundation enables effective evaluation of inappropriate admissions and excessive hospital stays [57].

In parallel, interest has grown in virtual care/remote patient monitoring as a strategy to reduce acute presentations [58,59]. Across the strongest syntheses, telehealth—especially remote patient monitoring (RPM)—shows the clearest and most consistent economic signal for reducing downstream utilization [60]. Multiple evaluations (US and OECD) find RPM is often cost-effective, with value largely driven by fewer hospital admissions and some reduction in ED visits, though results vary by disease area (most compelling for cardiovascular disease and hypertension, frequently favorable for heart failure), perspective (payer/health-system > provider), and implementation model [61]. Large program evaluations of tech-enabled “virtual wards” similarly suggest avoided non-elective admissions and net financial benefit at scale, but these findings are early and sensitive to assumptions about counterfactual use and staffing [58,62]. By contrast, the health-economic evidence base for AI is still immature: while select use-cases appear promising, published evaluations remain sparse, heterogeneous, and methodologically uneven, limiting firm conclusions about cost-effectiveness for readmission/ED reduction specifically [63]. Conversational agents (chatbots) have growing usability and feasibility evidence, but rigorous trials linking them to reduced readmissions/ED use and demonstrable cost-effectiveness are largely absent [64].

Table 2.

Brief historical snapshot of the evolution of Super-utilization.

Table 2.

Brief historical snapshot of the evolution of Super-utilization.

| Time | Context | Key Papers |

|---|---|---|

| Late 20th to early 21st century: Super-utilization is a cost-driver | Rising healthcare costs led to pressure to contain expenses while maintaining quality care. High levels of acute hospital care utilization impact on costs spurred exploration of strategies for managing high-utilization patients better, with care and system transformation initiatives emerging. The term Super-utilization emerged circa 2012 | World Bank Development Report, 1993 [20], OECD Quality Indicators Reports [21,22], Getting More for the Dollar [22], Kaiser Permanente Report, 2002 [23], World Health Organization Report, 2004 [24], Jiang HJ et al. Characteristics of Hospital Stays for Super-Utilizers by Payer, 2012 [1] |

| 2000s to 2010s: The Triple Aim and Value-based Care Models | Integrated care initiatives, part of system transformation efforts, aimed to enhance care coordination and efficiency while aligning with global endeavors to lower healthcare costs per capita, originating from the WHO, OECD, and US. The Triple Aim outlined goals of care, health, and cost. Care management and case management programs focused on targeting interventions to high-risk and high-cost patients, were seen as potential mechanisms for achieving value for money by improving outcomes and reducing unnecessary healthcare utilization. The modern hospital oscillated between providing a refuge/safety net for the vulnerable versus gatekeeping expensive disease and technology care. | Hasselman D. The Super-utilizer Summit, Center for Health Care Strategies 2013 [25], Berwick D et al. The Triple Aim. 2008 [26], Humowiecki M et al. Blueprints for Complex Care [28]. U.S. Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) [29], OECD. Health at a Glance 2019. OECD Indicators 2019 [32]; World Health Organization. Building the economic case for primary health care: a scoping review. 2018 [33]. McKee M et al. The role of the hospital in a changing environment 2000 [27] Cardona-Marell et al. The role of hospital in the last years of life 2017 [57] |

| 2010s to Present: Impact of Approaches to Super-utilization | The adoption of ‘value-based’ care models strengthened the connection between value for money and reducing healthcare costs per capita, addressing Super-utilization and care management/integrated care models, and prioritizing comprehensive and coordinated care delivery, and saw growing implementation despite mixed findings. International key bodies continue to endorse system transformation involving Super-utilization to contain costs. Hotspotting in underserved communities (deep-end practices) typically involves identifying specific geographic areas or populations with high levels of healthcare needs and targeting interventions to address those needs. | Berwick D. On transitioning to value-based health care. 2013 [65] Douglas et al. Global Adoption of Value-Based Health Care Initiatives Within Health Systems. 2025 [51]. Gawande, A. (16 January 2011). The Hot Spotters: Can We Lower Medical Costs by Giving the Neediest Patients Better Care? The New Yorker, 40–51 [28] Humowiecki M et al. Blueprints for Complex Care [28]. Accountable Communities [35,66] Deep End projects [54,67] HealthAlliance Caboolture [68] |

| Circa 2015- | The Super-utilization terminology shifted to High-Need/High-Cost patients in these settings circa 2014–16, although terminology remains mixed and variable. Interventions may include community alignment/engagement with community organizations, faith-based groups, and local stakeholders, use of community health workers outreach and programs and interventions targeting social determinants such as housing instability, food insecurity, transportation barriers, and economic hardship to address underlying health disparities. Also, the concept of rates of admissions in the last 180 days of life has more recently emerged, as Super-utilization initiatives move to segment populations to more targeted objectives. In recent years, the framework has evolved to include a focus on the well-being of the healthcare workforce and advancing health equity, leading to what is now referred to as the Quintuple Aim. This expansion recognizes the importance of supporting healthcare providers and addressing disparities in health outcomes among different populations. However, there is no evidence that such initiatives shift the cost or quality curve to date. | McCarthy D 2015 Models of Care for High-Need, High-Cost Patients: An Evidence Synthesis [36] Chang ET, Asch SM, Eng J, et al. What Is the Return on Investment of Caring for Complex High-need, High-cost Patients? Journal of General Internal Medicine 2021;36(11):3541–3544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07110-y [48] Sarnak D, Ryan J. How High-Need Patients Experience the Health Care System in Nine Countries. 2016. The Commonwealth Fund. Nundy S, Cooper LA, Mate KS. The Quintuple Aim for Health Care Improvement: A New Imperative to Advance Health Equity. JAMA. 2022;327(6):521–522. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.25181 [69] |

| Parallel Developments | Telecare, virtual care, remote care. Post covid, there has been a massive switching to telehealth, virtual patient care and remote monitoring. Overall, technology may bend utilization and costs in the right direction when embedded in well-designed care pathways and funded from a payer/sector perspective, but generalizability depends on local context, reimbursement, and the fidelity of implementation. Data analytics and predictive modelling techniques were leveraged to identify high-utilization patients at risk of poor outcomes and tailor interventions to their specific needs, thereby optimizing resource allocation and improving cost-effectiveness. | Schulte T et al. Big Data Analytics to Reduce Preventable Hospitalizations-Using Real-World Data to Predict Ambulatory Care-Sensitive Conditions. 2023 [70,71] virtual care/remote patient monitoring as a strategy to reduce acute presentations Norman, G., Bennett, P., & Vardy, E. (2023). Virtual wards: a rapid evidence synthesis and implications for the care of older people. Age Ageing [58,59]. Across the strongest syntheses, telehealth—especially remote patient monitoring (RPM) De Guzman, K.R., Snoswell, C.L., Taylor, M.L., Gray, L.C., & Caffery, L.J. (2022). Economic Evaluations of Remote Patient Monitoring for Chronic Disease: [60]. Potter, J., Watson Gans, D., Gardner, A., O’Neill, J., Watkins, C., & Husain, I. (2023). Using Virtual Emergency Medicine Clinicians as a Health System Entry Point (Virtual First) [58,59,60] Xue, J et al. (2023). Evaluation of the Current State of Chatbots for Digital Health: Scoping Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 25, e47217. https://doi.org/10.2196/47217 [64]. Zhang, Y., Peña, M.T., Fletcher, L.M., Lal, L., Swint, J.M., & Reneker, J.C. (2023). Economic evaluation and costs of remote patient monitoring for cardiovascular disease in the United States: a systematic review. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 39 [61]. Voets, M.M., Veltman, J., Slump, C.H., Siesling, S., & Koffijberg, H. (2022). Systematic Review of Health Economic Evaluations Focused on Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: The Tortoise and the Cheetah. Value in Health, 25(3), 340–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2021.11.1362 [63]. |

3.2. How Have the Patterns (Terms, Metrics, and Framings) of Super-Utilization Changed over Time, and What Do These Reveal About Underlying System Priorities? What Are the Key Frame Works?

Based on the discussions with the reference group, a complicated picture of the nature of Super-utilization and the impact of strategies and interventions emerged [16]. It was determined to proceed with a narrative review based on key papers identified and described in Table 3, in order to develop a more in depth understanding of the key themes with a structured review of the literature on Super-utilization.

Table 3.

Initial key papers for the snowball sample that emerged from complexity science working group of the North American primary care research group, committee on the science of family medicine in 2022 [24,72].

Table 3.

Initial key papers for the snowball sample that emerged from complexity science working group of the North American primary care research group, committee on the science of family medicine in 2022 [24,72].

| Citation | Study Focus | Country/Setting | Methodology | Key Insights |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camden Coalition [28] | Community-based care coordination | USA (NJ) | Program documentation | Emphasized patient complexity, social needs, and community navigation |

| Finkelstein et al. (2020) [73] | Camden Coalition “Hotspotting” RCT Underserved Communities | USA | Randomized Controlled Trial | No significant impact on readmission; highlighted importance of engagement and selection bias |

| Berkman (2021) [3] and Chang (2022) [73] | Synthesis of HNHC patient interventions | USA | Systematic review, realist synthesis | Found small to moderate effects on utilization; minimal impact on cost or outcomes |

| Iovan et al. (2020) [43] | US emergency care interventions for super-utilizers | USA | Systematic review | Identified weak evidence base; large heterogeneity in interventions and outcomes |

| Lantz (2020) [Milbank Quarterly] [74] | Policy critique of super-utilizer programs | USA | Theoretical commentary | Critic of evaluation paradigm and achievement of equity goals |

| [Burton C, Elliott A, Cochran A, et al. EMJ [17]] | Frequent ED attendance as a complex system | UK | Data linkage + statistical analysis | Revealed non-linear patterns and self-organization in ED usage |

| De Guzman KR, Snoswell CL, Taylor ML, et al. [60] Zhang Y, et al. [75] | Telehealth Virtual ward transitional care, chatbots | International USA/Canada | Systematic review + meta-analyses | Improvements in some metrics for specific conditions such as COPD. questions about cost, scalability and generalizability |

3.2.1. Iterative Search Development

The structured search terms used in this review were developed through a scoping and iterative snowball sampling process, grounded in foundational literature and policy documents (see Table 2) that shaped the evolution of the super-utilization discourse. The process began with initial index terms and MeSH headings derived from key sources such as the Camden Coalition publications, HRRP evaluations, and systematic reviews on high-cost, high-need patients.

These foundational documents informed a three-phase approach to search strategy refinement:

Phase 1—Core Concept Identification: Terms like “superutilizer,” “readmission prevention,” and “frequent ED user” were drawn from early U.S. policy initiatives (e.g., HRRP, Camden Coalition) and linked publications including Jiang [1,2], Lantz [74], Berkman [3] and McCarthy [36].

Phase 2—Terminological Expansion: Synonym clusters were developed using snowball sampling of article keywords, title variants, and citation chaining. This included common synonyms (e.g., “frequent flyer,” “repeat admitter,” “acopia”) as well as broader umbrella terms like “high-need/high-cost.”

Phase 3—Care Management Linkage: A third search strategy cross-linked superutilization with care models (e.g., “case management”, “transitional care”, “virtual care”) and system-level concepts (e.g., “social determinants”, “integrated care”, “complex care”, “predictive analytics”).

Throughout, the aim was to balance sensitivity with relevance, ensuring inclusion of both quantitative and qualitative studies, and capturing terminological evolution across U.S., OECD, and international settings. This was not a quantitative exercise, but based on emersion in the literature with multiple search iterations.

A representative set of final search formulations is provided below.

- Super-utilization root search: ((((((superutilization) OR (superutilisation) OR (super-utilization) OR (superutilizers) OR (repeat admissions)) OR (emergency department frequent use)) OR (high-cost/high-need)) OR (readmission prevention program)) OR (potentially avoidable hospitalization/hospitalisation))).

- Expanded superutilizer synonym search: ((superutilizer) OR (super-utilizer) OR (hotspot user) OR (repeat admitter) OR (repeat emergency department attender) OR (frequent user) OR (frequent flyer) OR (high-need/high-cost) OR (acopia)).

- Care management linkage search: ((primary care) OR (nurse)) AND ((care management) OR (care coordination) OR (case management) OR (integrated care) OR (transitional)) OR (remote OR virtual care) AND ((utilization) AND (ED) OR (readmission) OR (super utilization)).

3.2.2. Search Yield and Thematic Signal

Across iterations, the principal PubMed query (1 January 2012–30 March 2024) returned ~34,000 records tagged to one or more super-utilization–related terms; ~3690 were indexed in the most recent 12-month interval (to 30 March 2024). Automated PubMed publication-type tags within the broader corpus included 806 RCTs, 1206 clinical trials, 36 narrative reviews, and 779 systematic reviews. Counts fluctuated modestly across repeat queries because of database updates and in-dexing. Table 4 describes Super-utilization as a phenomenon.

To examine how emphases differed by perspective, I ran companion searches ori-ented toward individual-focused identifiers. Superutilizers as a cohorts or groupings of individuals profiles are described in Table 5 and provider/management/service per-spectives terminology profiles are described in Table 6. A further query added mixed-methods and qualitative filters beyond RCTs and systematic reviews to better capture experiential literature.

3.2.3. Relative Frequency of Major Themes

Across all four search groupings, utilization metrics dominated the indexed literature, peaking in the 12-year Super-utilization query and again in the past-year subset. Care management terms were the next most prevalent theme (≈20–25% of retrieved records across Super-utilization {Table 4} and Superutilizer queries {Table 5}). Cost tags ranked third.

Conversely, needs (health, social, functional, or quality-of-life) were comparatively underrepresented—≈8% of records in the broad Super-utilization search versus ≈20% in the Superutilizer search and ≈24–25% in the Care Management search {Table 6}. Provider roles most frequently indexed were nursing and primary care. Despite their centrality in policy narratives, care management processes remain a relative “black box” in the evidence base; systematic reviews report limited detail on operational components and sparse data on patient-reported quality-of-life outcomes [32].

Themes related to system transformation appeared primarily in Care Management–oriented searches. Homelessness, quality of life, and broader needs language were uncommon in the Super-utilization corpus but reached ~20% frequency in the other searches, especially when qualitative filters were applied. Disease-specific framing was proportionally higher in Care Management (≈37% of records) than in Super-utilization or Superutilizer searches (≈4–11%). Broader contextual/systemic constructs—population health, community, social determinants, or social needs—were present but low (<12%). Explicit multi-level systems or complex adaptive systems terms were rare (<1%), as were hotspot or ecological systems tags (<1%). See Table 4.

Table 4.

Superutilization key themes key concepts and frequencies from narrative searches on super-utilization literature (pubmed 2012–2024). super-utilization key themes identified by searching terms of ((((((superutilization) or (super-utilization) or (superutilizers) or (repeat admissions)) or (emergency department frequent use)) or (high-cost/high-need)) or (readmission prevention program)) or (potentially avoidable hospitalization/hospitalization))))) on 30 March 2024. ((((((superutilization) or (superutilisation) or (super-utilization) or (superutilizers) or (repeat admissions)) or (emergency department frequent use)) or (high-cost/high-need)) or (readmission prevention program)) or (potentially avoidable hospitalization/hospitalization))))) with filter and case study (n = 30) or qualitative methods [n = 81]. Table totals represent how many articles mention the term with some overlap amongst articles. (Search conducted 12 April 2024).

Table 4.

Superutilization key themes key concepts and frequencies from narrative searches on super-utilization literature (pubmed 2012–2024). super-utilization key themes identified by searching terms of ((((((superutilization) or (super-utilization) or (superutilizers) or (repeat admissions)) or (emergency department frequent use)) or (high-cost/high-need)) or (readmission prevention program)) or (potentially avoidable hospitalization/hospitalization))))) on 30 March 2024. ((((((superutilization) or (superutilisation) or (super-utilization) or (superutilizers) or (repeat admissions)) or (emergency department frequent use)) or (high-cost/high-need)) or (readmission prevention program)) or (potentially avoidable hospitalization/hospitalization))))) with filter and case study (n = 30) or qualitative methods [n = 81]. Table totals represent how many articles mention the term with some overlap amongst articles. (Search conducted 12 April 2024).

| Super-Utilization Key Themes | Total (n = 34,046) | % of Total | Past Year (n = 3690) | % of Past Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalization, Readmission, ED Attendance | 23,445 | 70% | 3622 | 98% |

| Utilization/Use | 15,668 | 46% | 1419 | 38% |

| Complex/Case/Care Management; Medication or Integrated Care | 7239 (6077) | 21% (17%) | 939 | 25% |

| Costs/Economic Outcomes | 4340 | 12% | 338 | 9% |

| Population Health/Community/SDOH/Social Needs | 4230 | 12% | 603 | 16% |

| Disease | 3752 | 11% | 456 | 10% |

| Primary Care | 2763 | 8% | 355 | 9% |

| Needs (Health, Social, or Quality of Life) | 2985 | 8% | 463 | 9% |

| Complexity (General) | 2382 | 7% | 296 | 13% |

| Community-Specific Term | 1768 | 5% | 248 | 9% |

| Health Needs | 1720 | 5% | 260 | 7% |

| Quality of Life | 1354 | 4% | 234 | 7% |

| Social Determinants (SDOH) | 1105 | 4% | 142 | 6% |

| Complex Care (as specific term) | 912 | 3% | 102 | 4% |

| Predictive Analytics/AI/Big Data | 710 | 3% | 101 | 4% |

| Homelessness | 411 | ~1% | 59 | <1% |

| Multilevel Systems | 120 | <1% | 15 | <1% |

| Complex Adaptive Systems | 70 | <1% | 50 | 1% |

| Hotspot | 35 | <1% | 11 | <1% |

Table 5.

Superutilizer search term frequencies (PubMed 2012–2024). superutilizer search or (((superutilizer) or (super-utilizer) or (hotspot user) or (repeat admitter) or (repeat emergency department attender) or (frequent user) or (frequent flyer) or (high-need/high-cost) or (acopia))); using alternative search terms (homelessness) and (frequent utilization or remission) yielded 435 results. (frequent utilization or readmissions) filtered by clinical trial, meta-analysis, randomized controlled trial, review, systematic review, from 1 January 2012–12 April 2024 n = (29,407) (filtered by homelessness yielded n = 54 (frequent utilization or readmissions) filtered by case study methods n = 187. (frequent utilization or readmissions) filtered by homelessness (n = 54); using alternative search terms (homelessness) and (frequent utilization or remission) yielded 435 results without filters and with filters by clinical trial, meta-analysis, randomized controlled trial, review, systematic review, from 1 January 2012–12 April 2024 (n = 45). (Search conducted 12 April 2024).

Table 5.

Superutilizer search term frequencies (PubMed 2012–2024). superutilizer search or (((superutilizer) or (super-utilizer) or (hotspot user) or (repeat admitter) or (repeat emergency department attender) or (frequent user) or (frequent flyer) or (high-need/high-cost) or (acopia))); using alternative search terms (homelessness) and (frequent utilization or remission) yielded 435 results. (frequent utilization or readmissions) filtered by clinical trial, meta-analysis, randomized controlled trial, review, systematic review, from 1 January 2012–12 April 2024 n = (29,407) (filtered by homelessness yielded n = 54 (frequent utilization or readmissions) filtered by case study methods n = 187. (frequent utilization or readmissions) filtered by homelessness (n = 54); using alternative search terms (homelessness) and (frequent utilization or remission) yielded 435 results without filters and with filters by clinical trial, meta-analysis, randomized controlled trial, review, systematic review, from 1 January 2012–12 April 2024 (n = 45). (Search conducted 12 April 2024).

| Super-Utilizers Rates of Key Concepts by Narrative Search Terms | 1 January 2012–12 April 2024 n = 4580 | % | 1 Years n = 567 | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Readmission rates or ED attendance frequencies | 1431 | 31 | 6 | <1 |

| Rates or frequencies | 1261 | 27 | 4 | <1 |

| Care and (management or coordination or complex or integrated) | 973 | 21 | 4 | <1 |

| Needs | 899 | 20 | 3 | <1 |

| (Primary care) and ((care or (management or coordination or complex or integrated))) | 437 | 9.5 | 4 | <1 |

| (Primary care) and ((nurse or (management or coordination or complex or integrated))) | 314 | 7 | 37 | 6 |

| Disease | 174 | 4 | 1 | < |

| (Utilization) or costs | 134 | 3 | 3 | <1 |

| Unmet needs | 40 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Homelessness | 87 | 1.3 | 1 | |

| SDOH | 4 | <1 | 1 | |

| Person-centered | 14 | <1 | 0 | 0 |

Table 6.

Care management search term frequencies (pubmed 2012–2024) care management search results ((primary care) or (nurse)) and ((care management) or (care coordination) or (case management) or (integrated care) or (transitional)) and ((utilization) and (ed) or (readmission) or (super utilization)) filtered by clinical trial, meta-analysis, randomized controlled trial, review, systematic review. Adding additional search term and case study or qualitative methods (n = 29,707).

Table 6.

Care management search term frequencies (pubmed 2012–2024) care management search results ((primary care) or (nurse)) and ((care management) or (care coordination) or (case management) or (integrated care) or (transitional)) and ((utilization) and (ed) or (readmission) or (super utilization)) filtered by clinical trial, meta-analysis, randomized controlled trial, review, systematic review. Adding additional search term and case study or qualitative methods (n = 29,707).

| Concept/Search Term Care Management | Filtered (n = 4432) | % of Filtered | With Case Study/Qualitative Methods (n = 29,707) | % of Expanded |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rates or frequencies | 2485 | 56% | 7125 | 25% |

| Disease | 1623 | 37% | 7312 | 29% |

| Needs | 1049 | 24% | 7125 | 25% |

| Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) | 75 | 2% | 443 | 2% |

| Quality of Life (QOL) | 66 | 1.5% | 309 | 1% |

| Homelessness and (frequent utilization or readmission) | 25 | <1% | 93 | <1% |

| Costs | 650 | 15% | 1529 | 6% |

3.3. How Have the Terms, Metrics, and Framings of Super-Utilization Changed over Time, and What Do These Reveal About System Priorities? Intervention Typologies and Emergent Patterns

This section synthesizes the conceptual and operational diversity of care management models. It identifies distinct intervention types (e.g., disease-specific programs, hotspotting, virtual wards), characterizes their typical metrics, and maps their alignment—or misalignment—with complex systems principles (Table 7).

Table 7.

Narrative of super-utilization intervention typologies in the literature in the context of systems–this is not exhaustive as other terms exist in the complicated literature of us and OECD health systems and other international systems. This is a result of narrative and identifying references to illustrate important themes and taxonomies in the international OECD orientated literature. It is not comprehensive but purposive.

Table 7.

Narrative of super-utilization intervention typologies in the literature in the context of systems–this is not exhaustive as other terms exist in the complicated literature of us and OECD health systems and other international systems. This is a result of narrative and identifying references to illustrate important themes and taxonomies in the international OECD orientated literature. It is not comprehensive but purposive.

| Taxonomy/Intervention Type | Key Characteristics/Definitions | Complex Systems Features Identified by This Author | Representative References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Super-utilizer (SU) | Top-Down indicators Defined by high ED/hospital use and cost (e.g., HCUP data) | Utilization metrics limited to age/geography/payer context; lacks systems nuance | Jiang et al. (2012, 2014) [1,2,76,77,78]; HCUP Briefs [77] |

| Avoidable Hospital Admissions (AHA), Potentially Preventable Hospitalization (PPH), Ambulatory Care Sensitive Conditions (ACSC) International | Top-Down Indicators Preventable with timely primary care; OECD QI metrics | Utilization Metrics Limited Social determinants, geographic variation, health indicators lack context of local system dynamics | OECD [22,55]; Thygesen et al. (2015) [79]; Sowden et al. (2020) [80] |

| Readmission Programs Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) US Hospital Admission Risk Program (HARP) Australia | Top Down Rehospitalization within 30 days; condition-specific metrics | Utilization Metrics Demonstrate regression to the mean, variation in outcomes, complexity of metrics interpretation | Beauvais et al. (2022) [29].; Nuckols et al. (2017) [81] |

| Disease Management Chronic Disease Management International | Central Programs Chronic condition-focused interventions (e.g., COPD, CHF) | Utilization Metrics, Mortality Limited Success in Specific diseases Unintended consequences, implementation, fairness issues, complex systems producing disease–not shifting the cost curve | Ref. [82] Global Burden of Disease Study (2021) Psotka MA, et al. (2020); Mathematica Policy Research. (2017). Damery S, Flanagan S, Combes G. (2016); Liu H et al. (2018) [83,84,85,86] |

| Frequent Emergency Department (ED) Attendance, Frequent Flyers, Frequent Users, etc. Persistent, Transient ED users etc. International | Service Centric Variable 3–>6 ED visits/year; context-specific thresholds | Utilization Metrics Emergence, variation by setting, regression to mean; lack community systems context | Shehada et al. (2019) Ng SHX, et al. 2020 Moe J, et al. 2022; Grafe CJ, Horth RZ, Clayton N, et al. 2020 [40,71,87] |

| High-need/High-cost (HNHC)/Persistent HNHC, Transient HNHC etc. | Segmentation of metrics to highest costing patients cost/utilization, persistent vs. transient use | Utilization Metrics Trajectory patterns, local variation, emergence of different cohorts | Berkman [39,88,89,90] |

| Hotspotting and Complex Care (e.g., Camden US) Deep-end Practices UK | Multidisciplinary, social determinants, trust-building | Utilization Metrics with Feedback loops, facing inertia in system change. Well-meaning bottom-up initiatives are limited by the overwhelming broader system factors | Ref. [73] Humowiecki [28,54,91] |

| Accountable Communities/Social Navigation US | Community-linked social needs integration models | Utilization Metrics—low adaptability, fragmentation; low impact due to top-down approaches | Ref. [35]; Renaud et al. (2023) [66] |

| System Complexity (General) | Small-area variation, emergent patterns, adaptive care models | Multilevel, nonlinear dynamics, cultural/contextual factors. Difficult paradigm shifts. Limited implementation | Ref. [92]; Burton et al. (2021) [93,94,95,96] |

| Trajectory or Journey Care | Individual journeys—resilience, support | Individual Journey Care. Well-meaning person-centric care, limited by funding streams directed at hospitals and institutions—paradigm shifts difficult | Martin et al. (2018) [93]; McIntyre [97] et al. Resilience in Chronic disease and frailty [96,98] |

3.4. What Dominant and Neglected Themes Emerge in the Literature, Particularly Regarding Cost, Care Experience, Equity, and System Complexity?

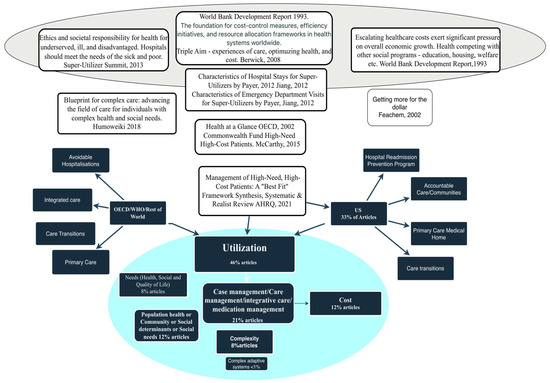

Across three major thematic searches, persistent patterns were identified. Most interventions focused narrowly on reducing utilization rates and associated costs. Figure 1 demonstrates the breakdown of the literature into predominantly a metrics outcome- driven endeavor. As the literature is continually expanding and changing, this analysis is purposive, attempting to be representative but cannot claim to be comprehensive.

Figure 1.

Overview of patterns of super-utilization in literature review References [20,21,22,23,24,25,26].

Patient-centered metrics were largely absent, appearing in only 8–25% of the reviewed literature depending on search category. Social determinants of health were acknowledged in many articles as confounders or drivers, but interventions rarely addressed them beyond descriptive framing, or as confounders. Notably, hotspotting, deep-end practices, and accountable communities’ programs aimed to address social determinants of health but did not demonstrate improved utilization metrics nor improved quality of life. Few studies incorporated system dynamics, feedback loops, or adaptation over time. Centralized policies, particularly those inspired by the Triple Aim, often failed to account for local conditions and disparities, and were largely driven by proxies for econometric ‘value for money’ rather than ‘experiences of health and quality of life’.

The dominant framing of super-utilization as a cost problem for hospitals has constrained the development of meaningful solutions. While some hotspotting and community-based efforts attempted to engage social complexity, most remained tied to quantitative performance indicators and narrow metrics of success. This technical orientation has eclipsed the broader relational, experiential, and structural aspects of chronic illness and care navigation.

3.5. To What Extent Do Current Approaches Reflect System Complexity and Patient Needs, and How Might Alternative Framings Inform Policy and Evaluation? A Systems Perspective

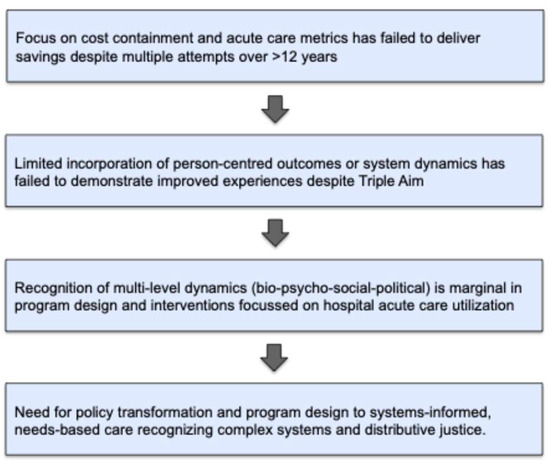

Consistent evidence exists about biological health and environmental factors that drive complex human systems [5,99]. The landmark Nature article by Martin Scheffer and others [98] identified the human ability to regulate essential physiological parameters—based on the coordinated functioning of organs and subsystems connected through complex hormonal and neural networks. This intricate dynamic system is continuously challenged by factors such as physical demands, nutritional input, adverse occurrences, lived environments and communities, and various other stressors [98]. A decrease in systemic resilience, defined as the ability to restore normal function after a disturbance, leads to poorer health with elevated risks of morbidity and mortality, and acute hospital use [100]. Emergency care and admissions are driven by factors beyond poor care coordination and lack of case management [50]. The focus on specific diseases, even if successful improvements did occur in areas such as heart failure, chronic pulmonary disease, asthma, and diabetes, account for a small proportion of repeat admissions. Such improvements did little to shift the bottom line. For example, in Australia, with diseases labeled as ambulatory care sensitive conditions, the biggest predictors of Super-utilization are health, self-perceived health, healthcare access, sociodemographic and community factors [101] Reduced systemic resilience is a major factor in acute healthcare use 102. These findings reinforce evidence linking population traits to healthcare usage, and show that social determinants such as income, food security, and homeownership relate to healthcare patterns. Such approaches recognize social determinants of health and there are moves to develop international indicators of High-need, High-cost across selected OECD countries [90]. Factors that are modifiable by health services inputs are limited to optimizing service performance [102] and cannot mitigate the complex systems factors that drive Super-utilization. Complex systems drive social determinants [95]. There is an emergent literature, but little evidence that models over time will account for the systemic and non-linear complexity of Super-utilization, as there are a few such approaches in the upcoming literature [89,93,96,102,103,104]. Addressing predisposition to Super-utilization goes beyond what health services can achieve, and requires multi-level intersectoral social and political-economic commitment (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Overview of findings from the review.

Strengths and Limitations

This review offers several strengths in its approach to understanding the emergence, framing, and evaluation of super-utilization in health systems. First, its constructivist and policy-oriented lens enables a broader interpretation of super-utilization—not simply as a clinical or economic category, but as a socially constructed concept shaped by funding models, political priorities, and shifting performance frameworks. This perspective allows for interrogation of the assumptions embedded in dominant metrics (e.g., readmission rates) and invites consideration of distributive justice, complexity, and lived experience.

Second, the review process demonstrated internal validity through iterative saturation and triangulation. Across multiple phases of structured and emergent search strategies, repeated refinements of terminology and inclusion criteria consistently returned the same core themes. The robustness of these themes across diverse literature searches—quantitative and qualitative, empirical, syntheses and policy-based—supports the credibility and coherence of the synthesis. See Supplementary Table S1 describing Mapping Inductive Coding Process to Critical Systems Heuristics (CSH) in the Thematic Analysis of Super-Utilization Literature to provide further reliability and validation of the analytic process.

However, there are limitations inherent in this type of narrative and scoping synthesis. While the multi-phase design allowed for a comprehensive capture of international literature, the review did not apply a strict PRISMA protocol or formal risk of bias assessment. This may limit reproducibility and make the findings less comparable to narrowly focused systematic reviews. Moreover, while the snowballing and term-expansion approach provided conceptual breadth, it relied on researcher judgment to balance sensitivity and specificity, potentially missing niche or localized studies.

The use of specific terms versus their near-synonyms (e.g., “frequent flyer” vs. “super-utilizer”) or broader taxonomic extensions (e.g., “complex chronic patients”) can significantly influence retrieval sets and thematic clustering. To address this, I conducted cross-checks using expanded synonyms and evaluated the stability of thematic patterns. The core categories remained robust across term variations, indicating that the underlying thematic structures (e.g., cost containment, system navigation, patient complexity) were not highly sensitive to minor lexical changes.

Nonetheless, this review’s strength lies in surfacing the deeper paradigmatic assumptions and system-level dynamics that often go unexamined in traditional evaluations of super-utilization. It sets the stage for a shift toward more integrated, equity-informed, and complexity-aware approaches to high-need, high-cost populations.

4. Discussion

4.1. How Has the Concept of Super-Utilization Emerged in Policy and Academic Discourse, and What Foundational Paradigms Have Shaped It?

In Phase 1, this review explored the historical and policy origins of the term Super-utilization and its proliferation in the literature since 2012. The concept reflects a convergence of global policy concerns with economic efficiency, especially in fragmented systems with rising costs and poor coordination. Policy frameworks such as the Triple Aim (improving care experience, population health, and reducing per capita costs) served as powerful drivers. These frameworks gained traction internationally through the lens of avoidable hospitalizations and emergency department attendances, with super-utilization becoming a proxy for inefficiency.

Multiple variations of the term emerged, such as “frequent flyer,” “repeat admitter,” “high-utilizer,” and “high-need/high-cost”. By the mid-2020s, high-need/high-cost (HNHC) became more prominent in both U.S. and OECD literature. However, while these terms provided a focal point for resource-intensive populations, they also risked reinforcing a narrow, econometric framing, reducing complex human experiences to utilization counts. Person-centered outcomes and system-level dynamics were often marginal or absent.

Despite efforts to enhance care coordination and value-based care, the persistent emphasis on utilization rather than lived experience or complexity has limited the impact of such programs. Moreover, performance indicators often penalized systems serving disadvantaged populations, thereby entrenching inequities.

4.2. What Types of Interventions Have Been Implemented to Reduce Super-Utilization, and How Effective Are They in Shifting Utilization Patterns, Improving Patient Outcomes, and Addressing Social Determinants of Health?

Phase 2 reviewed the vast body of literature targeting super-utilization through interventions such as care coordination, case management, transitional care, and integrated service delivery. These programs, often guided by Triple Aim logic, were primarily evaluated based on reductions in emergency visits or readmissions.

Despite the investment and spread of these interventions, meta-analyses and pragmatic trials consistently reported modest or short-lived improvements. Studies often failed to meaningfully address underlying causes of high use, including poverty, multimorbidity, housing instability, and fragmented services. Evaluations also relied heavily on econometric and utilization metrics, with limited assessment of patient experience, quality of life, or long-term system impacts.

Enhanced frameworks like the “Quintuple Aim” have called for the inclusion of health equity over and above the Quadruple aim that addressed workforce well-being. However, few studies in this review demonstrated concrete equity-sensitive or complexity-informed approaches. Although social determinants are increasingly acknowledged, they are rarely understood as integrated as dynamic system drivers into program design or evaluation. In fact, they represent a lack of understanding of the evolution of individual poor health, lack of resources, and reduced resilience of communities, as well as health service dynamics and hospital-centric funding. There are notable exception such as Inter Mountain Health which is increasingly moving into community development [105].

4.3. How Have the Terms, Metrics, and Framings of Super-Utilization Shaped Research Publications, and What Does This Reveal About Underlying System Priorities?

The language and conceptual framing of super-utilization have played a central role in shaping the structure and outcomes of research. Search terms and metrics in Phase 3 showed a bias toward cost and utilization outcomes, reinforcing dominant system priorities. Lived experience, patient-reported outcomes, and relational continuity were rarely included.

This scoping phase revealed a publication landscape where research questions, methods, and reporting were implicitly aligned with the policy desire to reduce costs. The complexity of health and social needs among frequent users was often oversimplified through reductive labels and metrics. For instance, few studies disaggregated data by socioeconomic status, race, or comorbid burden. Instead, “success” was defined in terms of fewer hospital visits or shorter lengths of stay—regardless of whether individuals experienced improved stability or well-being. Non-recognition of the pareto distribution of acute care 80:20 or 90:10 rule (versus a normal distribution) [17,106] which would see super-utlization as expected rather than deviant.

Moreover, a lack of standard definitions for super-utilizer, high-cost/high-need, and frequent ED user further complicated synthesis across studies. The variation in terminology and thresholds obscured underlying population differences, limiting generalizability and policy translation.

4.4. To What Extent Do Existing Interventions and Evaluations Incorporate Systems-Thinking, Complexity Theory, and the Lived Experience of High-Need, High-Cost Populations Reflecting Distributive Justice?

The synthesis phase concluded that current paradigms insufficiently account for the complexity and structural inequities underpinning super-utilization. A radical reframing is needed to shift from econometric containment toward enabling healthier, more stable life trajectories for vulnerable individuals in the context of their family and community resources.

Most interventions reviewed operate under a linear, reductionist model—where high use is seen as a deviation to be corrected. Few programs accounted for non-linearity, emergence, adaptation, or path-dependence, all hallmarks of complex adaptive systems. Instead, simplistic causal assumptions drive short-term, transactional fixes. System resilience, care discontinuities or fragmentation, and historical disadvantage were rarely addressed.

Distributive justice offers a powerful lens for reimagining super-utilization. Instead of viewing high-need patients as cost burdens, policy and practice should prioritize these groups, their journeys and their settings for quality improvement, resource reallocation, and adaptive care models, rather than add-on services when they become high users. Community Interventions should embrace narrative methods, lived experience data, and relational continuity—alongside dynamic analytics that reflect system complexity at micro-, meso- and macro-levels.

In summary, addressing super-utilization requires a shift in both narrative and metrics—from “reducing the frequent user” to “enabling stable health trajectories in complexity.” Without this paradigm shift, systems will continue to punish vulnerability with misaligned incentives and under-resourced responses.

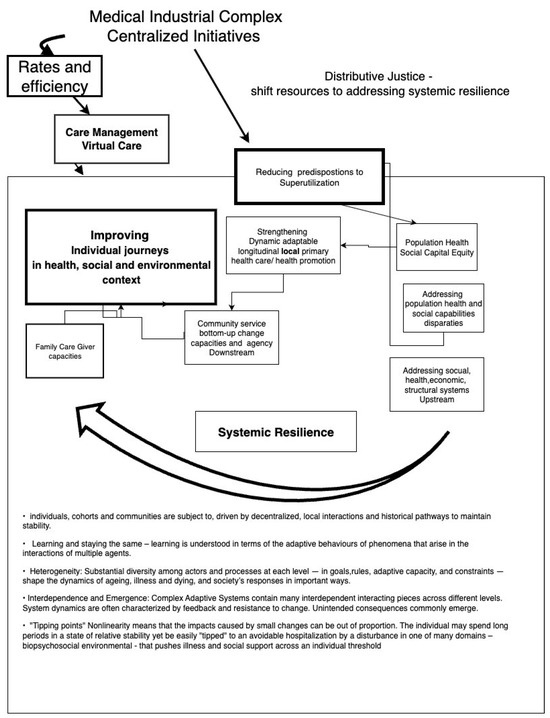

As depicted in Figure 3, super-utilization reflects more than inefficiency—it reveals systemic fragility. While dominant responses emphasize centralized care management and rates-based containment, these approaches inadequately address the interdependent, emergent, and nonlinear dynamics of health, illness, and social conditions. A justice-informed paradigm calls for systemic resilience: strengthening longitudinal local care, enabling family and community agency, and addressing upstream determinants. This shift not only reframes the ethics of resource use but offers a more adaptive response to the complexity of high-need, high-cost trajectories.

Figure 3.

Reframing super-utilization: from efficiency metrics to systemic resilience. This systems-informed conceptual model contrasts dominant health system responses to super-utilization—framed by centralized, efficiency-driven policies—with a distributive justice approach that prioritizes resilience, equity, and person-centered care. While current initiatives emphasize cost containment through care management and virtual interventions, this model proposes redirecting resources toward strengthening local primary care, supporting family and community agency, and addressing upstream social determinants. Super-utilization is reframed not as individual excess but as the outcome of complex, nonlinear trajectories shaped by biopsychosocial–environmental interactions–systemic resilience [98].

Legend (Key Concepts):

- Medical Industrial Complex/Centralized Initiatives: National policies and economic structures that prioritize efficiency, rate reductions, and system-level cost containment.

- Rates and Efficiency Focus: Emphasis on reducing readmissions, emergency attendances, and acute utilization as primary quality and performance metrics.

- Care Management and Virtual Care: Common tactical responses that may stabilize individual trajectories but often neglect underlying structural inequities.

- Distributive Justice Frame: Ethical and systemic shift toward equity by reallocating resources to support the needs of high-cost, high-need individuals and communities.

- Improving Individual Journeys: Focus on person-centered, longitudinal care within health, social, and environmental contexts.

- Systemic Resilience: The capacity of health and social systems to adapt dynamically to instability and complexity, ensuring stability and equity over time.

- Complex Adaptive Systems Principles: Path-dependence and heterogeneity: Illness and care trajectories are diverse and shaped by past experiences and context. Nonlinearity and tipping points: Small disruptions can trigger disproportionate deterioration in health or wellbeing. Hospital admission or ED attendance can be seen as a ‘tip’ into perceived worse health. Interdependence: Health outcomes emerge from interactions between biological, social, and structural systems, requiring multidimensional responses.

Across three major thematic searches, persistent patterns were identified. Most interventions focused narrowly on reducing utilization rates and associated costs. Patient-centered metrics were largely absent, appearing in only 8–25% of reviewed literature depending on search category. Social determinants of health were acknowledged but interventions rarely addressed them beyond descriptive framing. Few studies incorporated system dynamics, feedback loops, or adaptation over time. Centralized policies, including those inspired by the Triple Aim, often failed to account for local conditions and disparities. Case management is the major intervention to address Super-utilization internationally, yet has not demonstrated meaningful cost-effectiveness, nor a significant impact on health disparities. Telehealth [79], particularly remote patient monitoring (RPM), consistently reduces hospital admissions and is often cost-effective—especially for cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and heart failure—mainly from a payer or health-system perspective. Large-scale evaluations of tech-enabled virtual wards also point to fewer non-elective admissions and potential overall savings, though these results are still preliminary and context-dependent. In contrast, economic evidence for AI in healthcare remains limited and inconsistent, with few robust studies. While chatbots show growing feasibility, there is little proof they reduce readmissions or costs. Overall, technology may lower healthcare utilization and expenses when integrated into effective care pathways, but broader impact relies on local factors and implementation quality.

The dominant framing of super-utilization as a cost problem has constrained the development of meaningful solutions. While some hotspotting and community-based efforts attempted to engage social complexity, most remained tied to quantitative performance indicators and narrow metrics of success. This technical orientation has eclipsed the broader relational, experiential, and structural aspects of chronic illness and care navigation. See Figure 3.

From a CSH perspective, the dominant framing of super-utilization as primarily a cost problem reveals narrow boundary judgments about what counts as success and whose interests are prioritized. Metrics such as readmission rates and ED visits define the problem in technical and quantifiable terms, excluding deeper relational, experiential, and systemic dimensions of chronic illness and care navigation. Patients, carers, and local frontline actors are frequently absent from the design and governance of interventions. Institutional logics—efficiency, standardization, and throughput—tend to override individual needs, agency, and contextual complexity.

A complex systems perspective views Super-utilization as a socially constructed phenomenon that emerges from the interaction of biological vulnerability, psychosocial adversity, fragmented care, and policy-level resource constraints. Addressing these factors requires more than service coordination; it calls for a paradigm transformation in how health systems conceptualize and respond to high-need patients. One size does not fit all and feedback loops in learning systems should adapt to individual and group heterogeneity, tipping points etc. Interventions must integrate narrative, anticipatory, and relational approaches that stabilize health trajectories over time. Since the review was conducted, even more pressing literature is emerging that older more vulnerable people are spending longer waiting for emergency admissions due to workforce shortages in primary and community care to this point in time [107].

A key strength of this review lies in its internal validation through conceptual saturation and iterative triangulation. Across multiple rounds of literature identification and thematic analysis, core narratives persisted, affirming the robustness of the identified frameworks. This reflects the rigor of the constructivist search and analysis process, despite its departure from more conventional PRISMA protocols and based upon CSH principles. However, the approach has limitations because it is qualitative. It is recognized that more formal validation—such as through n-gram or topic modeling algorithms (e.g., LDA)—could provide an additional layer of analytic rigor. This is a potential enhancement for future studies and is included as a limitation. On balance, the validity of the paper’s conclusions is assured because the theme of cost containment predominated over quality of care, and particularly quality of life, in every iteration and permutation.

5. Conclusions

This review demonstrates that the dominant framing of super-utilization—as a problem of cost and system inefficiency—has constrained both the conceptual development and practical effectiveness of interventions. While policy models like the Triple Aim catalyzed attention, the resulting approaches prioritized utilization metrics over patient experience, equity, or system complexity.

Across the literature, interventions such as care coordination and case management have shown limited and often short-lived impact, with little engagement with the social and structural determinants underpinning high use. While this is changing with greater awareness over time, interventions and evaluations were rarely designed to capture complexity, emergent dynamics, or distributive justice. Terminological inconsistencies further obscure understanding, while reductive metrics continue to shape a research and policy landscape focused on containment rather than transformation.

Super-utilization is not merely an operational or clinical challenge, but a symptom of deeper systemic imbalances—reflecting the interaction of biological vulnerability, structural inequities, and health system fragility. Current models focused on cost containment and episodic care management fail to engage with the layered, dynamic realities of patients’ lives or the complexity of the systems in which they are embedded. To shift this paradigm, super-utilization must be reframed—not as a deviation to be minimized, but as an indicator of unmet need, community instability, and policy failure. This calls for complexity-informed, justice-oriented approaches that prioritize relational continuity, lived experience, and investment in upstream determinants. Strengthening local resilience, enabling community agency, and adopting adaptive, multi-level care models are critical to enabling stable health trajectories—particularly for those most marginalized. Without this shift, systems risk perpetuating cycles of reactive care and structural inequity. As workforce shortages and access barriers intensify, particularly for older and vulnerable populations, the imperative to address super-utilization through a systems lens becomes even more urgent. Future research and policy must move beyond surface-level metrics to tackle the interdependent, emergent, and inequitable dynamics that shape high-need, high-cost trajectories.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/systems13110965/s1, Table S1: Mapping Inductive Coding Process to Critical Systems Heuristics (CSH)7 in the Thematic Analysis of Super-Utilization Literature.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks colleagues and peer reviewers who contributed to the conceptual refinement of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jiang, H.J.; Weiss, A.J.; Barrett, M.L.; Sheng, M. Characteristics of Hospital Stays for Super-Utilizers by Payer, 2012. In Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs; Statistical Brief #190; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.J.; Weiss, A.J.; Barrett, M.L. Characteristics of Emergency Department Visits for Super-Utilizers by Payer, 2014. In Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs; Statistical Brief #221; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman, N.D.; Chang, E.; Seibert, J.; Ali, R.; Porterfield, D.; Jiang, L.; Wines, R.; Rains, C.; Viswanathan, M. Management of High-Need, High-Cost Patients: A “Best Fit” Framework Synthesis, Realist Review, and Systematic Review; Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 246; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2021. Available online: https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/products/high-utilizers-health-care/research (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Adler, N.E.; Cutler, D.M.; University, H.; Fielding, J.E.; Galea, S.; University, B.; Glymour, M.M.; Koh, H.K.; Satcher, D. Addressing Social Determinants of Health and Health Disparities: A Vital Direction for Health and Health Care. In NAM Perspectives; Discussion Paper; National Academy of Medicine: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plsek, P.E.; Greenhalgh, T. Complexity science: The challenge of complexity in health care. BMJ 2001, 323, 625–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, W. Beyond methodology choice: Critical systems thinking as critically systemic discourse. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2003, 54, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, W. Critical System Heuristics—Better Evaluation 2025. Available online: https://www.betterevaluation.org/methods-approaches/approaches/critical-system-heuristics (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Who are the Superutilizers? In Proceedings of the Workshop of The Complexity Science Working Group of Committee of the Science of Family Medicine, North America Primary Care Research Group Annual Conference, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 18–22 November 2022; North America Primary Care Research Group: Leawood, KS, USA, 2022.

- Rice, P.; Ezzy, D. Qualitative Methods, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Melbourne, Australia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]