Abstract

Despite the underdeveloped formal institutional system in China’s capital market, the venture capital (VC) industry has continued to grow rapidly, exhibiting a clear trend of network formation. To better understand the formation of VC networks, this study systematically analyzes factors from three dimensions: endogenous network structures, multidimensional relational networks among VC firms, and informal networks of venture capitalists. Using data from the Wind database and other sources, networks are constructed based on 1317 investment events involving 157 VC firms. An exponential random graph model is applied to assess the effects of multiple network embeddings on VC network formation. The results reveal that, among endogenous structural factors, triad closure structures are more likely to be embedded in VC networks than two-path structures with brokerage functions. In terms of exogenous factors, the geographic distance network among VC firms exerts a negative effect on VC network formation, while knowledge proximity networks—i.e., those based on industry, investment stage, and region—positively influence VC networks formation. Informal networks of venture capitalists increase the probability of VC network formation. Compared with previous studies, this research is based on self-organization, market-oriented, and relational logics, integrating multiple factors—including endogenous network structures, venture capital firm characteristics, and venture capitalists—and introduces a cross-network perspective to build a novel multilevel network embedding ERGM framework to examine VC network formation. Furthermore, the study reveals how informal ties substitute for formal institutions in China’s VC network formation.

1. Introduction

The central role of venture capital in China’s economic strategy—highlighted by the 2024 CPC meeting—frames the urgency to understand how venture capital networks form despite institutional constraints. Specifically, the meeting emphasized the need to actively develop venture capital and expand patient capital to promote technological innovation in China. Innovation, in essence, is an investment process [1]. Venture capital firms tend to pursue high-risk, high-return projects, which makes their investment decisions face information asymmetry and significant uncertainty. Especially when investing in pioneering innovative enterprises, this demands greater capital size and risk tolerance. Therefore, venture capital firms often adopt syndication to reduce investment risks [2]. Syndicated investment forms foundation of VC networks, which are created through joint investments in entrepreneurial firms [3]. These networks have become the primary structure supporting inter-organizational relationships in the venture capital industry.

While syndication reduces investment risk, it introduces agency conflicts and opportunistic behaviors due to diverse roles across institutions—e.g., lead vs. follow investors—amplifying the importance of governance structures. In essence, these issues should be addressed through the establishment of a multi-level capital market system and formal institutional safeguards. However, compared to developed countries, China’s formal institutions remain relatively underdeveloped. Theoretically, this would reduce interactions among investment institutions and hinder the formation of joint investments and networks. In practice, the opposite appears to be true. Given the prevalence and significance of VC networks, it is essential to explore why venture capital in China demonstrates robust network development.

A review of the existing literature indicates that venture capital networks are essentially formed through co-investment among venture capital firms [4], and their formation mechanisms are closely linked to the motives driving such co-investments. Consequently, prior studies have largely examined the formation logic of venture capital networks from a co-investment perspective. Specifically, related studies have mainly focused on the following aspects: First, from the perspective of individual characteristics of venture capital firms, since a single firm is limited in terms of information, knowledge, and resources, it tends to focus on the intangible assets of potential partners—such as reputation, capability, and existing collaboration history—when selecting syndication partners [5,6,7,8,9]. Second, from the perspective of inter-organizational attributes and external environmental similarity, previous studies have examined how factors such as investment experience, industry knowledge, professional domain, geographic distance, and institutional culture influence the formation of co-investment relationships [10,11,12]. As research has further deepened, scholars have begun to recognize that co-investment should not be understood merely as dyadic cooperation between firms, but should be studied within the broader context of multi-party syndication. For example, Zhang et al. [13] explored the effects of network structural features, such as network size and density, on the formation of multi-party syndication relationships. Driven by the ERGM methodology, an increasing number of studies have incorporated endogenous network structural factors into the analysis, such as network position embedding and reciprocity structures, to examine their influence on the formation of venture capital networks [14,15]. However, although these studies have examined network structural factors, they have mainly focused on indicators such as network size, density, centrality, and reciprocity. In comparison, relatively limited attention has been given to the triad closure structures and two-path structures, which exhibit important self-organizing characteristics. In fact, these two structural patterns, respectively, reflect the logic of trust accumulation and the pathways of information transmission and are therefore critical for uncovering the endogenous mechanisms underlying venture capital networks formation.

Moreover, as a statistical model for analyzing network formation mechanisms, the ERGM method can account for both individual actor attributes and dyadic as well as network-level relationships [16]. Therefore, scholars have increasingly applied ERGM models to examine the combined effects of individual-level features, dyadic relations between organizations, and network structures on venture capital network within a unified framework [14,17]. Compared with traditional regression models, this approach alleviates endogeneity concerns and addresses the challenge of integrating multi-level influencing factors. However, when including inter-organizational similarity factors in ERGM models, existing research still mainly followed a dyadic matching logic. They focus on the pairwise characteristics between investment firms to explore their cooperation tendencies, without truly extending these dyadic relationships to the overall network level. For example, Zheng et al. [18] applied the ERGM method and considered industry, geographic location, and capital type homogeneity among venture capital firms as important factors in partner selection. However, when incorporating these inter-organizational homophily factors, the study still remained at the dyadic matching level. Thus, it is unable to uncover the generative mechanisms of cooperative behavior within the broader network context. In contrast, this study argues that networking has become the primary form of relationships between venture capital firms. It is necessary to extend dyadic inter-organizational relationships to the network level within the model, and to analyze how interactions between different networks influence cooperation behavior from a “network affecting network” perspective. Notably, this network analysis perspective has already been widely applied in innovation collaboration network field, analyzing the impact of multi-dimensional networks on the formation of collaboration networks through the QAP method [19]. Therefore, this study adopts this cross-network analysis approach and incorporates it into the ERGM framework to reveal the mechanisms underlying the formation of venture capital networks.

Furthermore, existing research has largely relied on a market-oriented logic, focusing on explaining collaboration motives at the organizational level while relatively neglecting the relational networks among venture capitalists within the organizations. In the specific context of China, informal institutional factors such as personal ties, guanxi, and social circles can significantly influence organizational behavior and internal relationships. However, many studies, based on the assumption that individuals are affiliated with organizations, often generalize individual-level emotional ties directly to organizational relationships—which is commonly observed in previous research [20,21]—thereby blurring the boundaries between organizational economic relationships and individual emotional ties. As a result, most studies examine the effects of social network characteristics on co-investment solely at the organizational level [8]. Although previous studies have recognized the importance of internal venture capitalists’ network, they have primarily focused on micro-level effects such as economic returns, transactional behaviors, and the establishment of investor-entrepreneur relationships. For example, Lee [22] and Liu et al. [23] found that personal connections, such as alumni relationships between venture capitalists and entrepreneurs, significantly influence transaction behavior. Similarly, senior executives’ career backgrounds, alumni ties, and other personal characteristics also have a significant impact on a firm’s investment decisions and performance [24]. However, there is still a lack of systematic research on how personal relationship networks exert cross-level influences on inter-organizational networks among VC firms, and whether they can serve as a substitute or compensatory mechanism in contexts where formal institutions are absent.

Based on the gaps mentioned above, this study builds a multi-level framework that integrates endogenous network structures, inter-organizational networks, and personal networks of venture capitalists, grounded in network self-organization logic, market-oriented logic, and relationship-oriented logic. Specifically, the framework addresses three aspects: (1) from the perspective of endogenous network structures, it focuses on the roles of triad closure and two-path structures in shaping venture capital networks; (2) it extends dyadic inter-organizational characteristics, such as geographic distance and knowledge similarity, to the network level, examining the effects of geographic proximity and knowledge proximity networks on venture capital network formation; (3) it incorporates personal networks among venture capitalists to examine their cross-level effects on the formation of venture capital networks, and further explores whether these personal networks can function as informal mechanisms that substitute for or compensate for deficiencies in formal institutional.

This rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the relevant literature and develops the research hypotheses. Section 3 describes the research design. Section 4 presents the analysis of the results and provides testing and discussion. Finally, Section 5 presents the research conclusions, contributions, implications, and limitations.

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Endogenous Network Structures and Venture Capital Networks

The formation of a network is influenced by its self-organizing processes. The establishment of any given tie in the network typically depends on the configuration of other existing ties. This autocorrelation mechanism appears as structural features at the macro level of the network. In other words, network structure results from self-organization and therefore exhibits endogenous effects [25,26]. Therefore, the endogenous drivers of network formation can be inferred by analyzing its structural features.

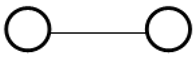

Among them, the most representative network structures are triad closure and 2-path structures. Triad closure is a network structure feature, typically captured by the geometrically weighted edgewise shared partners (GWESP) statistic. It indicates that when node A is connected to node B and C, B and C are also likely to form a direct connection, thus creating a closed triad. This structure reflects the transitive function of the network, meaning that if two nodes share a common neighbor, they are likely to form a direct tie with each other [27]. In venture capital networks, if two VC firms have a common co-investment partner, they are more likely to establish a new partnership. Additionally, through triad closure, VC firms can access a richer set of partner resources to respond to competition or protect their interests within the network [16]. Therefore, the triad closure structure helps facilitate the formation of venture capital networks.

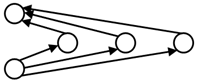

The two-path structure is another important network feature, typically measured by the geometrically weighted dyad-wise shared partners (GWDSP) statistic. It captures the number of node pairs that share a common neighbor. Specifically, if nodes A and B share the same neighbor C, there exists an indirect path of length two between A and B, reflecting potential bridging relationships in the network. This structure represents the pattern of indirect connections among nodes. In venture capital networks, investment firms occupying intermediary positions play a role in channeling resources and thus have clear brokerage functions [28]. However, in a two-path structure, information and knowledge must be transmitted through the intermediary node, which may reduce circulation efficiency and lead to information delays or distortion. This increases communication costs and cooperation barriers among venture capital firms. Therefore, 2-path structures with brokerage functions may inhibit the formation of venture capital networks.

In summary, compared with 2-path structures, triad closure structures are more likely to facilitate the formation of venture capital networks. Based on the discussion above, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1:

Venture capital networks exhibit a preference for embedding triad closure structures, meaning that triad closure structure enhances the probability of the formation of venture capital networks.

2.2. Multi-Dimensional Proximity Networks of Investment Institutions and Venture Capital Networks

The concept of proximity initially originated from geographic proximity, which refers to the spatial closeness of economic activities [29]. Over time, scholars have argued that proximity should not be limited to geography alone. Since human activities occur within diverse social, organizational, institutional, and cultural contexts, the proximity concept has evolved into a broader, multi-dimensional framework [30]. Current research on proximity mainly focuses on how different dimensions—such as geographic, technological, and knowledge proximity—affect knowledge transfer, diffusion, and innovation capacity [19,31]. However, academic perspectives remain divided on whether proximity exerts a positive or negative influence, and no unified conclusion has yet been established.

In the venture capital filed, due to the high levels of uncertainty and risk, investment firms must possess extensive professional expertise. As a result, knowledge compatibility becomes a key factor when they select syndication partners. In addition, for practical reasons such as discussing joint matters (e.g., equity allocation, project evaluation, and firm management) and reducing cooperation risks, geographic proximity also becomes a critical criterion for partner choice. Therefore, this study focuses on examining the effects of geographic proximity and knowledge proximity networks on the formation of venture capital networks.

2.2.1. Geographic Distance Network and Venture Capital Network

The geographical distance network measures the spatial proximity among venture capital firms. It is constructed as an adjacency matrix based on the geographic distances between the registered locations of the firms, reflecting the degree of spatial closeness among them. Geographic distance has long played a key role in the formation of social relationships, providing opportunities for trust and knowledge sharing between firms. Previous studies on geographic distance have mostly focused on how the distance between investment firms and their portfolio companies affects investment decisions and performance [32,33]. However, geographic distance also has an important impact on syndication decisions among investment firms.

From the perspective of trust mechanisms, investment institutions often face information asymmetry when considering syndicated investments. It is difficult to accurately assess the qualifications and capabilities of potential partners, and predict whether they may engage in opportunistic behavior that could harm mutual interests [18]. Nowińska A [34] argue that geographic proximity fosters similar cultural and institutional norms, promotes interaction, and enhances trust, thereby facilitating cooperation. Furthermore, the closer the geographical distance between investment firms, the easier it is for them to monitor each other’s actions, reducing the likelihood of opportunistic behavior. Conversely, greater geographic distance increases information asymmetry and communication costs between organizations [35], raising the risk of opportunism and hindering joint investments among firms.

From the perspective of resource acquisition and sharing, access to information and knowledge is a key motivation for joint investment [8]. Geographic proximity increases opportunities for face-to-face interaction, allowing institutions to observe, learn and imitate each other’s behaviors [36]. This promotes the exchange and acquisition of information and knowledge [37], thereby enhancing the probability of cooperation. In addition, closer geographic distances help reduce communication costs and increase the frequency of interaction, which is particularly beneficial for the transfer of tacit knowledge [37], thereby enhancing the willingness of investment firms to cooperate. Consequently, greater geographic distance tends to inhibit syndication between venture capital firms. Extending this mechanism to the network level, it can be inferred that geographic distance networks have a negative effect on the formation of venture capital networks. Based on the above, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2:

The geographic distance network exerts a significant negative impact on the formation of venture capital networks, indicating that geographic distance reduces the probability of the formation of venture capital networks.

2.2.2. Knowledge Proximity Network and Venture Capital Network

The knowledge proximity network measures the similarity of investment firms in terms of their knowledge structures. This network is constructed as an adjacency matrix by analyzing the alignment of firms in investment industries, stages, and regions, reflecting the degree of knowledge closeness among them. From the perspective of trust, investment institutions are more inclined to consult with reliable partners when evaluating whether a project is worth investing in [5,38]. When the knowledge similarity between collaborating firms is high, they are more likely to develop consistent investment philosophies and cognitive frameworks. This shared understanding deepens trust between organizations [39], thereby increasing the probability of cooperation among investment firms. Furthermore, a similar knowledge base provides a common ground for understanding, reducing communication barriers [40] and enabling more accurate and smooth exchange of information and knowledge. This lowers transaction costs and information asymmetry, thereby effectively enhancing mutual trust between cooperating firms.

From the perspective of knowledge transfer, a higher degree of knowledge proximity allows organizations to acquire and absorb knowledge more easily, thereby promoting collaboration between them [41]. In addition, similar knowledge structures reduce the barriers and cost of knowledge exchange, making knowledge acquisition more convenient and coordination more seamless. This improves the efficiency of knowledge sharing and absorption within the industry [42,43], ultimately increasing the likelihood of cooperation among investment institutions. Extending this mechanism to the network level suggests that knowledge proximity networks positively influence the formation of venture capital networks.

Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3:

Knowledge proximity networks exert a significant positive impact on the formation of venture capital networks, indicating that knowledge proximity increases the probability of venture capital network formation.

2.3. Venture Capitalists’ Informal Network and Venture Capital Network

An informal network refers to a social relationship network composed of members with complementary knowledge, similar interests, or shared emotional ties [44]. The core of such networks lies in relationships, which are maintained not by explicit rules or contracts, but primarily through conventions, trust, and commitment. Moral expectations and trust among members sustain the network’s development and operation. In contrast, a formal network is established through contracts, agreements, or institutional arrangements between organizations or individuals. Its foundation is the “contract,” which clearly defines the rights and responsibilities of network members. Examples of formal networks include alliance networks, patent licensing networks, CVC investment networks, and business networks maintained through contractual relationships [45]. Current research on the relationship between informal and formal networks presents divergent views. One perspective suggests that informal networks can support or complement formal networks, contributing to a more integrated system. Their interaction promotes knowledge sharing and transfer, thereby improving the functioning of formal networks [46]. Conversely, another perspective argues that because informal networks rely on personal connections and lack formal constraints, they may conflict with formal networks when members’ interests diverge, thus limiting their complementary potential [47].

Studies on informal networks encompass various types of social ties, such as those among relatives, friends, and colleagues. Examples include alumni networks based on shared educational backgrounds, friendship-based emotional networks, and advisory networks [44]. In China, where social relationships and “circle” cultural are highly valued, and given that the venture capital industry is high-risk and knowledge-intensive, venture capitalists’ educational and professional backgrounds can have a significant impact on the investment decisions and performance of their firms. Therefore, this study constructs informal networks of venture capitalists based on their social ties, focusing on two dimensions: shared educational experiences and shared employment experiences. It then examines how these informal networks affect the formation of venture capital networks.

2.3.1. Venture Capitalists’ Alumni Network and Venture Capital Network

The alumni network refers to a social network formed based on shared educational backgrounds. It shows the social connections established among individuals or organizations through a common alumni identity. It reflects the informal trust among members and potential channels for information sharing. From the perspective of trust, shared alumni relationships indicate that venture capitalists have similar educational backgrounds. This fosters shared memories and values, emotional bonds, evoking a sense of belonging, and strengthening mutual recognition and trust in each other’s identity and capabilities [48]. Trust can reduce the motivation for deception and psychological defensiveness, lowering vigilance and opportunism, thereby improving cooperation efficiency and reducing the cost of information transmission [49,50]. Therefore, when employees of organizations share alumni ties, it can effectively facilitate communication and collaboration, reduce monitoring and transaction costs, and ultimately increase the willingness of investment firms to cooperate.

From the perspective of resource accessibility, the trust and sense of recognition established through alumni relationships create favorable conditions for information and knowledge exchange. On the basis of trust, both parties are more willing to communicate openly and proactively share experiences and insights. This reduces barriers to resource flow and facilitates the transfer of tacit knowledge among network members [51]. As a result, investment firms connected through alumni relationships are more likely to establish collaborative partnerships. Extending this mechanism to the network level, it can be inferred that the network connections among investment institutions are shaped by the alumni networks of venture capitalists. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 4:

Alumni networks exert a significant positive impact on the formation of venture capital networks, meaning that investment institutions with shared alumni relationships are more likely to form syndicates.

2.3.2. Venture Capitalists’ Shared Employment Experience Network and Venture Capital Network

The shared employment experience network refer to a social network formed based on shared work experience in the same organization, institution, or company. This network is constructed as an adjacency matrix based on these shared work experiences among members. It reflects the trust, information flow channels, and resource access potential among members. Shared employment experience relationships mean that venture capitalists have previously worked at the same organization and have been shaped and influenced by the same corporate culture and institutional norms. From the perspective of trust, venture capitalists’ past employment experiences reflect their mobility across different VC firms. Such experiences not only enable them to maintain connections with former colleagues but also facilitate the establishment of new ties in their current organizations. The shared work background and frequent interactions enable employees in both the former and current organizations to build connections, thereby reinforcing the trust foundation between investment institutions [52] and laying the groundwork for collaboration [5,53]. Zaheer et al. [54] also emphasize that when employees of two firms share similar backgrounds or experiences, the firms are more likely to build trust.

Additionally, shared employment experiences contribute to the development of similar cognitive structures among employees. This shared cognition not only fosters psychological identification and trust [55], but also aligns their judgment when evaluating issues, significantly reducing communication costs and lowering barriers to resource exchange. As a result, knowledge sharing and information flow become more efficient [56,57], ultimately increasing the likelihood of collaboration between investment institutions. Extending this mechanism to the network level suggests that inter-firm network connections are partially influenced by the shared employment experience networks of venture capitalists. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 5:

Shared employment experience networks exert a significant positive impact on the formation of venture capital networks, indicating that investment institutions with shared professional affiliations are more likely to form syndicates.

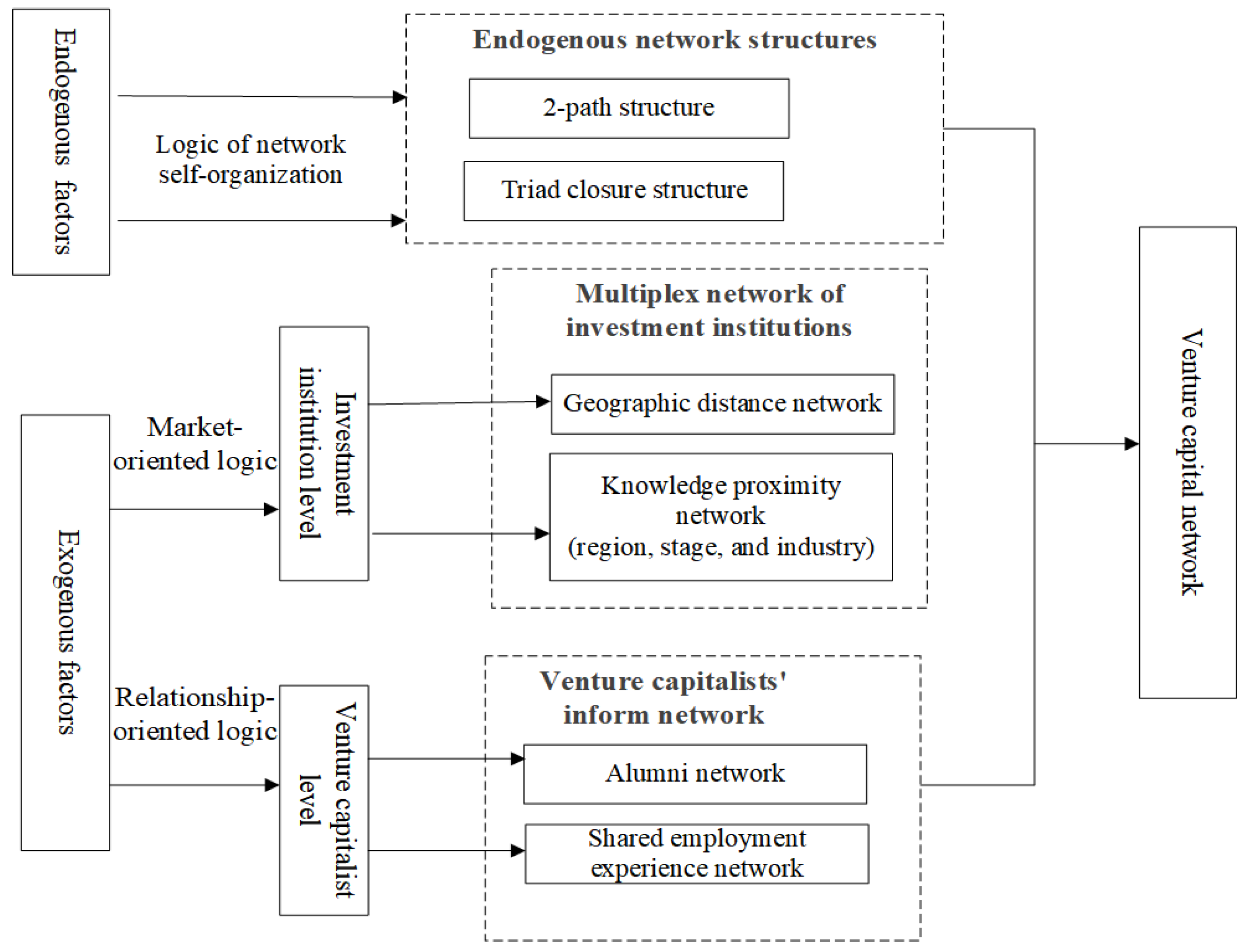

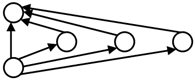

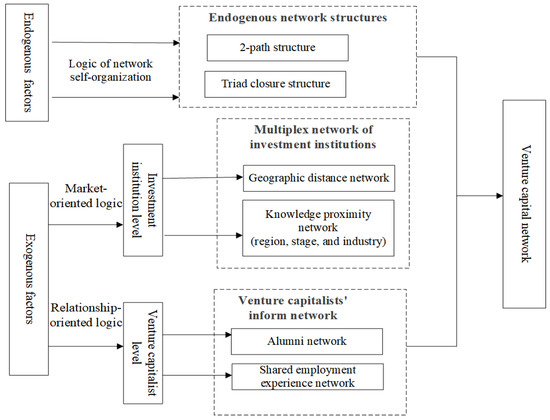

Based on the above analysis, we propose the research hypotheses table and the conceptual model diagram, shown in Table 1 and Figure 1, respectively.

Table 1.

Research hypotheses table.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of the research.

3. Research Design

3.1. Data Sources and Process

Data sources: The sample data primarily come from the PEVC and Person databases of Wind, which are widely recognized in academia for their high data reliability. These sources are supplemented and cross-verified with information from the CVSource database, Bestla analytics, and official company websites to ensure data accuracy and completeness. This study uses data up to the year 2021 as the sample for analysis.

The specific data processing procedures are as follows:

First, the sample of investment institutions was identified. Specifically, this study selects investment events from 2021 as the sample. After removing incomplete records, we obtained 3986 investment events involving 272 investment firms. Next, Following the approach of Shen et al. [52], we further selected active firms with three or more investment events, reducing the sample to 166 firms. This selection logic aims to exclude occasional investors who participated in only one or two investments, focusing instead on consistently active core institutions. It ensures that the analyzed samples exhibit stable investment behavior and traceable management team backgrounds, while minimizing noise caused by sporadic investment activities. On this basis, considering the need to identify key venture capital managers and their interpersonal network, we further selected firms with complete management team information. This resulted in a final sample of 157 firms and 1317 investment events. All selected sample are active venture capital firms that have been continuously operating, provide complete information, and have participated in at least three investment events. In terms of industry and geographic coverage, the sample covers major Chinese venture capital industries, such as healthcare, consumer services, and information technology. Geographically, most firms are located in active venture capital regions such as Beijing, Tianjin, the Yangtze River Delta, and the Pearl River Delta. Overall, the sample is highly representative in terms of industry and regional distribution, reflecting the concentration characteristics of the Chinese venture capital market.

Second, the sample of venture capitalists was identified. Based on the 157 selected investment firms, we collected the names and personal information of managers who remained in office until the end of 2021 using the Wind database (Person database and PEVC database). The information was manually collected, cross-checked, and supplemented using data from the CVSource database, Bestla database, official company websites. Although some data were extracted from proprietary databases (Wind, Bestla), summary statistics and network matrices are available upon request to ensure transparency. It is worth noting that, following the approach of Shen et al. [52], this study focuses on investment firm managers such as partners, presidents, and vice presidents, as they are the primary decision-makers in investments and have relatively complete personal background information.

Finally, the relevant network matrices were constructed. Information on the sampled investment firms—including investment events, geographic location, invested industries, regions and stages—was processed to build the venture capital network, geographic distance network, and knowledge proximity networks (by industry, region, and stage). Subsequently, information on internal venture capitalists’ alumni connections and previous employment experiences was then used to construct the alumni network and the shared employment experience network. In total, seven relational matrices were obtained for the 157 investment firms.

Based on these procedures, relevant metrics and network relationship matrices were first calculated using software such as R version 4.2.1. The ERGM was then developed using the statnet package in R version 4.2.1. The model-fitting process employed the Markov Chain Monte Carlo Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MCMC MLE) method. To assess model performance, the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) values were compared—where lower AIC and BIC values indicate better model fit and inform the selection of the optimal model. Finally, Goodness-of-Fit (GOF) tests and MCMC diagnostics were conducted to evaluate the alignment between the optimal model and the observed venture capital network.

3.2. Measurement of Variables

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

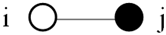

Venture Capital Network: Following prior research [2], the venture capital network is constructed as an adjacency matrix based on the number of joint investments between venture capital firms. It is a weighted, undirected network, where the edge weights reflect the frequency of co-investments. This approach captures not only whether two firms have collaborated but also the closeness of their cooperation.

3.2.2. Independent Variables

- A.

- Endogenous network structures

The endogenous network structures in this study include the triad closure and two-path structure. Following Snijders [58], the triad closure structure is measured using the geometrically weighted edgewise shared partners (GWESP) metric. It indicates that when node A is connected to both nodes B and C, nodes B and C are also likely to form a direct connection. This structure reflects the network’s transitivity.

The two-path structure is measured using the geometrically weighted dyad-wise shared partners (GWDSP) metric, which captures the number of node pairs that share common neighbors. Specifically, if nodes A and B share the same neighbor C, there exists an indirect path of length 2 between them. This structure reflects the brokerage function.

- B.

- Multidimensional relational networks of investment institutions

Geographic distance network (Edgecov_Geo): This refers to an adjacency matrix constructed based on the geographic distances between the registered cities of venture capital firms. Following previous studies [59], the geographic distance was calculated using the Haversine formula based on the registered city coordinates of each VC firm. Each element in the adjacency matrix is then normalized to produce a valued matrix with entries ranging from 0 to 1.

Here, Dij denotes the distance between firm i and firm j, where long and lat represent the longitude and latitude, respectively, measured in radians. A conversion coefficient C = 3, 437 is used to translate radians into miles on the Earth’s surface.

Knowledge Proximity Network (Edgecov_Kno): This network is represented by an adjacency matrix based on the degree of knowledge similarity between VC firms. Given that the knowledge possessed by a VC firm relates to the industry, stage, and geographic location of their portfolio firms, this study examines the consistency of investment choices across these three dimensions. The level of consistency is then used to measure the degree of knowledge similarity between institutions. Following Liu’s method for calculating consistency, industry knowledge similarity is measured as follows:

where didj represents the degree of industry knowledge similarity between investment institution i and institution j. L refers to the number of industry categories (classified into 11 categories according to the Wind Database); and Mij denotes the proportion of industries in which VC firm i and VC firm j invest within the same category.

The same approach is used to calculate stage similarity and regional similarity. Investment stages are divided into four categories: seed, startup, expansion, and maturity. Investment regions are divided into four categories: Beijing-Tianjin, Yangtze River Delta, the Pearl River Delta, and other regions. All three matrices—industry, stage, and region—are valued adjacency matrices, with entries ranging from [0, 1].

- C.

- Informal networks of venture capitalists

Alumni Network (Edgecov_Alu): The alumni network is represented as an adjacency matrix based on the shared educational backgrounds among venture capitalists. An alumni connection is considered to exist if venture capitalists from two firms have attended the same educational institution. It should be noted that the dependent variable is a weighted network, in which the edge weights reflecting frequency of co-investment. In addition, the number of shared educational ties among venture capitalists varies across firms, which may affect the intensity of inter-firm collaboration. Therefore, the alumni network is constructed as a weighted network, where the weight is defined by the number of shared educational relationships among venture capitalists from different firms.

Shared Employment Experience Network (Edgecov_Per): This variable is also represented by an adjacency matrix, constructed based on shared employment experiences among venture capitalists. A connection is considered to exist if venture capitalists from two institutions have previously worked at the same organization. Like the alumni network, this network is constructed as a weighted network, with edge weights defined by the number of shared employment experiences among venture capitalists from different firms.

3.2.3. Control Variables

According to previous studies [18,52,60], node-level attributes of investment institutions—such as institution age, team size, capital background, network status, investment experience, fund management scale, and investment amount—may also influence their attractiveness as syndication partners. Therefore, these attributes are included in the model as control variables.

Institution Age (nodefactor_age): Measured as the number of years from the institution’s founding to 2021. Categorized as follows: 0: 1–5 years; 1: 6–10 years; 2: 11–15 years; 3: over 15 years.

Team Size (nodecov_size): Measured by the number of executives in the management team.

Capital Background (nodefactor_bg): Categorized as: foreign capital, Sino-foreign joint capital, and domestic capital.

Network Status (nodecov_stat): Measured using degree centrality in the venture capital network.

Investment Experience (nodecov_exp): Measured by the total number of investment events conducted by the institution prior to 2021.

Fund Management Scale (nodecov_gov): Measured by the total fund management scale of the venture capital institution up to 2021.

Investment Amount (nodecov_inmon): Measured by the total investment amount of the venture capital institution up to 2021.

To facilitate understanding, Table 2 summarizes the terms used in the ERGM model and provides their interpretations.

Table 2.

Interpretation of ERGM terms.

3.3. ERGM Construction

The general expression for the Exponential Random Graph Model is:

where is a normalizing constant used to ensure that the probability distribution falls within the range of [0, 1] and sums to 1 across all possible networks, and θ represents the statistical parameter corresponding to the network statistic specified in the model. The models constructed in this study are as follows.

Model 1: Initially incorporating control variables

Model 2: Incorporate endogenous network structures based on Model1

Model 3: Incorporate multidimensional relational networks of investment firms based on Model 2

Model 4: Incorporate informal networks of venture capitalists based on Model 3

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Analysis of Model Results

The simulation of the ERGM in this study adopts a stepwise approach in which variables were gradually introduced and parameters iteratively adjusted until the estimation results stabilized. As in traditional regression analysis, the ERGM uses t-tests to assess the statistical significance of parameter estimates. The model fitting results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

ERGM results.

Model 1 in Table 3 serves as the baseline specification, incorporating only edge and node attribute variables. The coefficient of the edge is significantly negative (θ1 = −4.102, p < 0.001), which is a typical characteristic of real-world networks. Among the node-level variables, only network status (Nodecov_Sta) and investment amount (Nodecov_Inm) exhibit significantly positive effects (p < 0.001), indicating that higher network status and larger investment amounts significantly increase the likelihood of forming syndication ties. The AIC and BIC values for Model 1 are 6333 and 6415, respectively.

Building upon Model 1, Model 2 incorporates endogenous network structures. The result show that the coefficient of GWDSP is significantly negative (θ2 = −0.067, p < 0.001), indicating that two-path structure has a negative effect on the formation of the venture capital network. Specifically, for each 1-unit increase in the two-path structure, the probability of tie formation decreases to 0.93 (exp (−0.067)) times its original value. The coefficient for GWESP is significantly positive (θ3 = 1.529, p < 0.001), indicating that, compared with two-path structure, triad closure structure exerts a stronger positive effect on the formation of the venture capital network. Specifically, each one-unit increase in triad closure increases the likelihood of tie formation by a factor of 4.614 (exp (1.529)). This suggests that the venture capital network tends to embed in triad closure structures. Thus, Hypothesis 1 is supported. Moreover, Model 2 yields improved model fit, with AIC and BIC values of 6114 and 6211, respectively—both lower than those of Model 1.

Model 3 extends Model 2 by incorporating multidimensional relational networks at the venture capital firm level. The results show that the coefficient of the geographic distance network (Edgecov_Geo) is significantly negative (θ4 = −0.075, p < 0.001), indicating that geographic distance network has a significant negative impact on the venture capital network. Specifically, for each one-unit increase in geographic distance, the probability of tie formation between venture capital firms decreases to 0.928 (exp (−0.075)) times its original value, supporting Hypothesis 2.

In the knowledge proximity network, the coefficient for industry-level knowledge proximity (Edgecov_Kno.ind) is significantly positive (θ5 = 0.777, p < 0.001), indicating that the industry-level knowledge proximity network has a significant positive effect on the formation of the venture capital network. Specifically, for each one-unit increase in industry-level knowledge proximity, the probability of tie formation between venture capital institutions increases to 2.175 (exp (0.777)) times its original value. Similarly, the coefficient of regional-level knowledge proximity (Edgecov_Kno.geo) is significantly positive (θ6 = 0.402, p < 0.001), indicating that the regional-level knowledge proximity network has a significant positive effect on the formation of the venture capital network. Specifically, for each one-unit increase in regional-level knowledge proximity, the probability of tie formation between venture capital firms increases to 1.495 (exp (0.402)) times its original value. The coefficient for stage-level knowledge proximity (Edgecov_Kno.pha) is also significantly positive (θ7 = 0.885, p < 0.001), suggesting that stage-level knowledge proximity has a significant positive effect on the venture capital network formation. Specifically, for each one-unit increase in stage-level knowledge proximity, the probability of network tie between venture capital firms increases by a factor of 2.423 (exp (0.885)). These results confirm that knowledge proximity—across all three dimensions—enhances venture capital network formation. thereby supporting Hypothesis 3.

Additionally, Compared with Model 2, the coefficient of the GWESP remains significantly positive and increases slightly (θ3 = 1.563, p < 0.001), indicating that it continues to exert a positive effect on the formation of venture capital networks. Specifically, for each one-unit increase in triad closure structures, the probability of tie formation between venture capital firms increases to 4.773 (exp (1.563)) times its original value., further supporting for Hypothesis 1. In addition, the model fit continues to improve, with AIC and BIC values reduced to 6033 and 6159, respectively.

Building upon Model 3, Model 4 incorporates informal networks at the venture capitalist level. In Model 4, at the level of informal networks, the coefficient for the alumni network (Edgecov_Alu) is significantly positive (θ8 = 0.111, p < 0.05), indicating that shared educational backgrounds positively influence on the venture capital network formation. Specifically, for each one-unit increase in alumni ties, the probability of tie formation between venture capital firms increases to 1.117 (exp (0.111)) times its original value, supporting Hypothesis 4. Similarly, the coefficient for the shared employment experience network (Edgecov_Per) is also significantly positive (θ9 = 0.359, p < 0.001), indicating that the shared employment experience network has a significant positive effect on the formation of the venture capital network. Specifically, for each one-unit increase in shared employment experience, the probability of tie formation in the venture capital network increases to 1.432 (exp (0.359)) times its original value. Thereby supporting Hypothesis 5. By comparison, the effect of shared employment experience network (β = 0.359) is over three times that of alumni network (β = 0.111), suggesting shared employment experience fosters stronger trust than shared education background.

At the endogenous network structure level, compared with Model 3, the coefficient of the GWDSP remains significantly negative and shows little change (θ2 = −0.049, p < 0.001), indicating that its negative effect on the formation of venture capital networks remains significant. Specifically, for each one-unit increase in the two-path structure, the probability of tie formation between venture capital institutions decreases to 0.95 (exp (−0.049)) times its original value. In addition, compared with Model 3, the coefficient of GWESP remains significantly positive, with a slight increase in magnitude (θ3 = 1.565, p < 0.001), indicating that the positive effect of GWESP on the venture capital network is still significant. Specifically, for each one-unit increase in triad closure structures, the probability of tie formation between venture capital institutions increases to 4.783 (exp (1.565)) times its original value. This indicates that, compared with two-path structures, the venture capital network is more likely to embed in triad closure structures. This reinforces the validity of Hypothesis 1.

At the venture capital firm level, compared with Model 3,the geographic distance network (Edgecov_Geo) coefficient remains significantly negative, and its magnitude increases (θ4 = −0.043, p < 0.001), indicating that greater distance continues to hinder the formation of inter-institutional ties. Specifically, 1-unit increase in geographical distance reduces the probability of network tie formation between these firms to 0.958 (exp (−0.043)) times the original probability, reaffirming Hypothesis 2.

For all knowledge proximity networks, the coefficients for industry-level (Edgecov_Kno.ind), region-level (Edgecov_Kno.geo), and stage-level (Edgecov_Kno.pha) knowledge proximity remain significantly positive. Specifically, compared with Model 3, the coefficient of industry-level knowledge proximity network remains significantly positive, and its magnitude increases (θ5 = 0.794, p < 0.001), indicating a positive effect on the venture capital network. Each one-unit increase in industry-level knowledge proximity raises the probability of tie formation between venture capital institutions to 2.212 (exp (0.794)) times its original value. For the region-level knowledge proximity network, the coefficient also remains significantly positive, and its magnitude increases (θ6 = 0.418, p< 0.001), reflecting its positive effect on the venture capital network. Each one-unit increase in region-level knowledge proximity raises the probability of tie formation to 1.519 (exp (0.418)) times the original. For the stage-level knowledge proximity network, the coefficient remains significantly positive, with an increase in magnitude (θ7 = 0.902, p< 0.001), indicating a positive effect on the venture capital network. For each one-unit increase in stage-level knowledge proximity, the probability of tie formation between venture capital institutions increases to 2.465 (exp (0.902)) times its original value. These results all support Hypothesis 3.

Model 4 achieves the best overall fit, with the lowest AIC (6015) and BIC (6156) values among all models. Therefore, Model 4 is selected as the optimal specification.

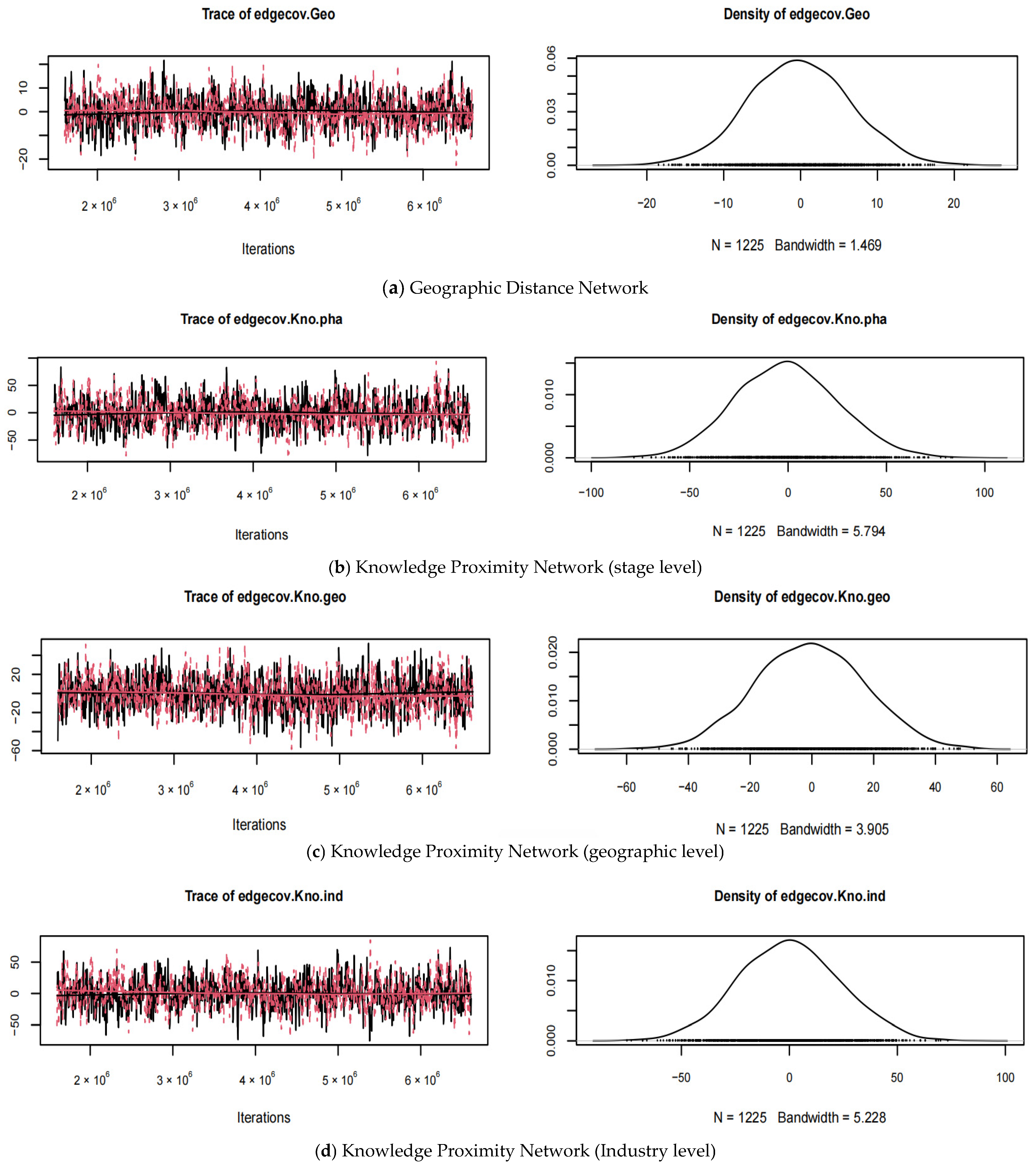

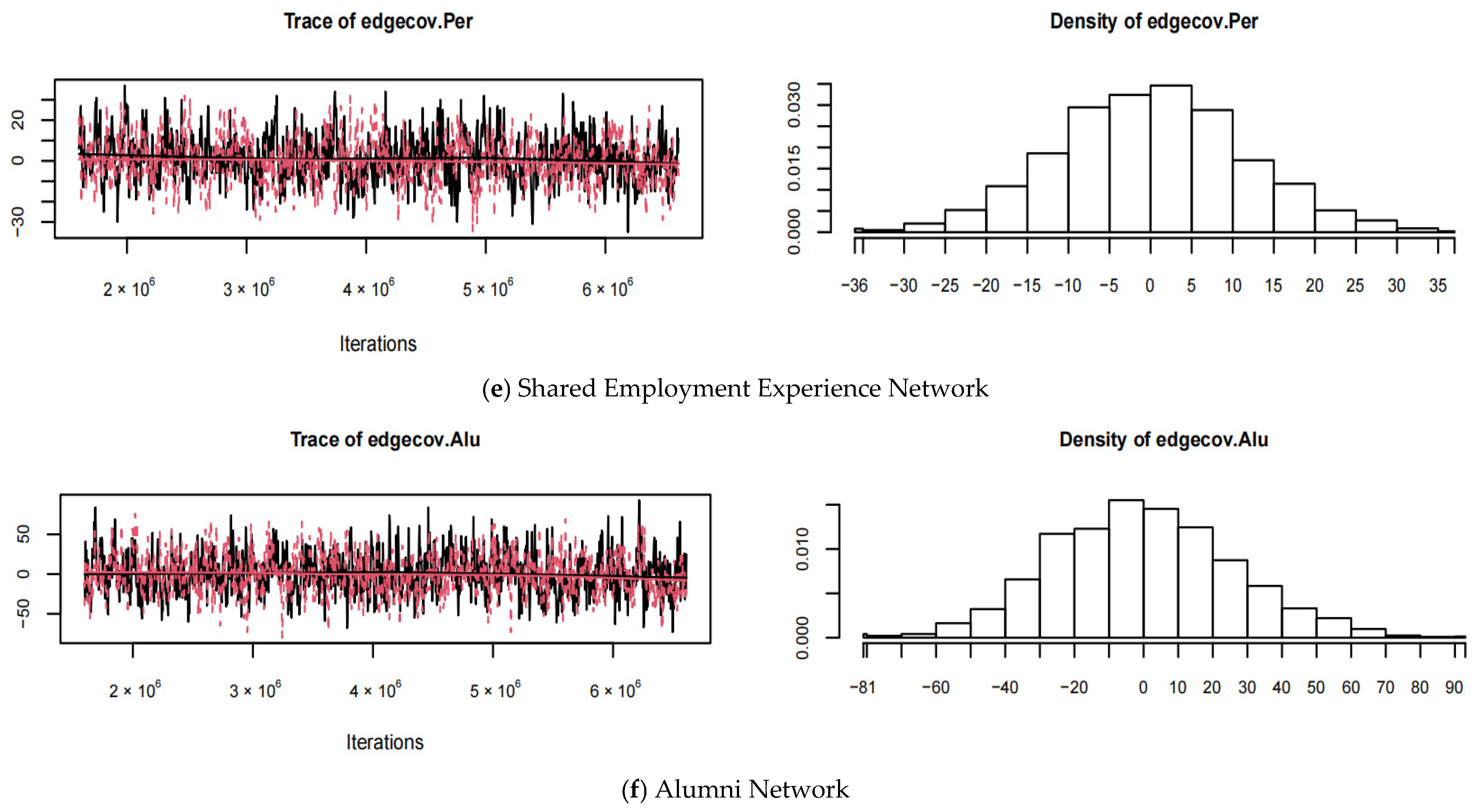

4.2. MCMC Model Diagnostics

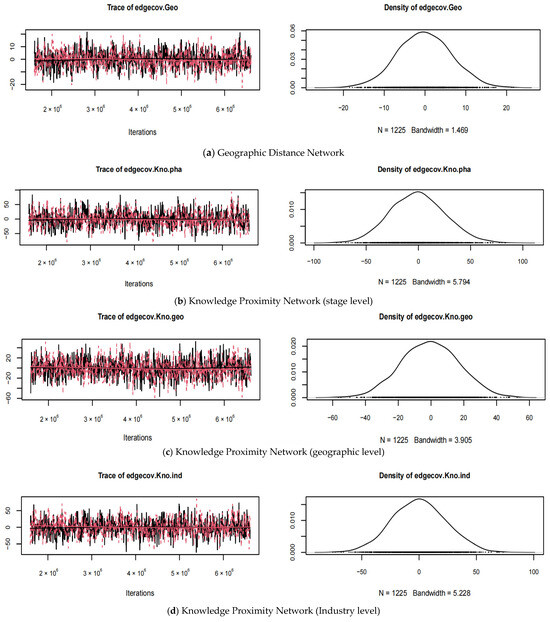

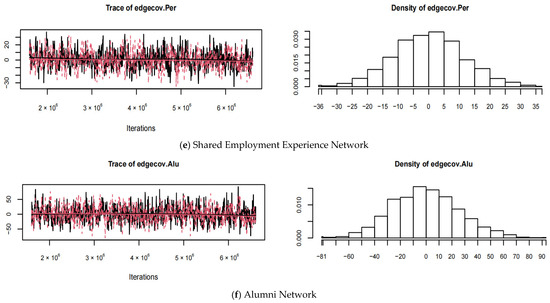

Since Model 4 was identified as the optimal model, we further conducted MCMC diagnostics based on Model 4 to assess whether the parameter estimation process achieved convergence and to check for any signs of near-degeneracy. This helps determine whether adjustments to the model specification or evaluation settings are necessary. Figure 2 presents the MCMC diagnostic results for Model 4.

Figure 2.

MCMC diagnostic plot.

Specifically, Figure 2 presents statistic included in the model, covering industry-, region-, and stage-level knowledge proximity networks, geographic distance networks, work experience networks, and alumni networks. The left panels show the time series traces of the MCMC chains, which allow us to observe the dynamic changes in the statistics over the iterations. The right panels display the corresponding density plots of the MCMC samples, which are used to examine their long-term distribution. In ERGM, assessing whether the model estimation has converged mainly focuses on the chain’s mixing behavior, whether the statistics fluctuate around the observed network statistics, and whether any systematic trends are present. If the model has achieved good convergence, the MCMC chains for each statistic should fluctuate randomly within a certain range, without showing any unidirectional drift or boundary-hitting behavior, and the density plots should be concentrated and stable.

As shown in Figure 2, the MCMC chains for all statistics in Model 4 fluctuate around 0, where zero represents the value of the corresponding statistic in the observed venture capital network. The chains fluctuate within a relatively stable range, without any sustained upward or downward trends, and show no obvious unidirectional drift or boundary-hitting behavior during the iterations, indicating good mixing. Meanwhile, the density plots on the right show that the distributions of the statistics are concentrated and unimodal, indicating that the model has not entered a degenerate parameter state. In summary, the MCMC diagnostics for Model 4 indicate that the model has achieved stable convergence, and none of the statistics exhibit signs of degeneracy.

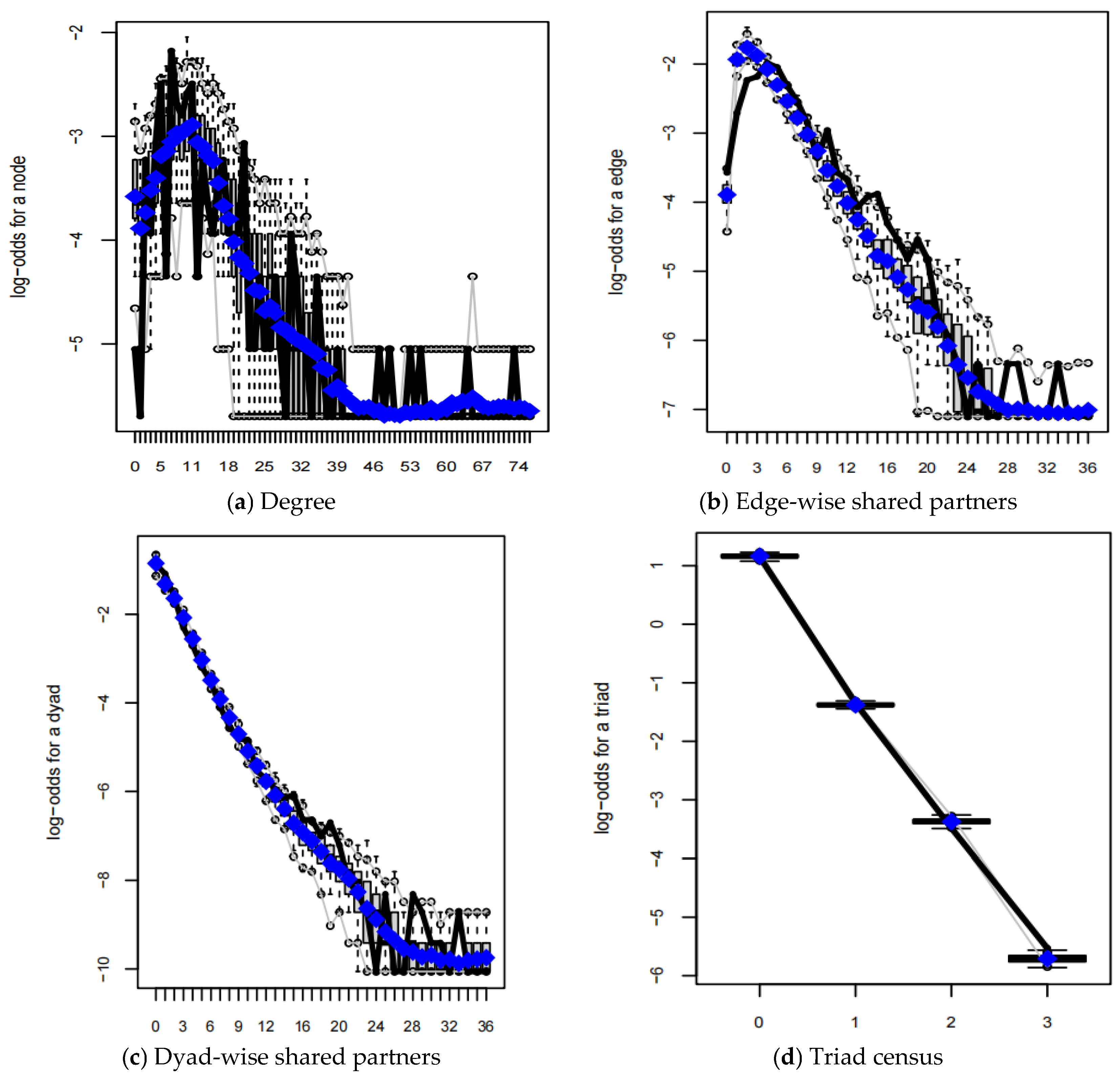

4.3. Goodness-of-Fit Test

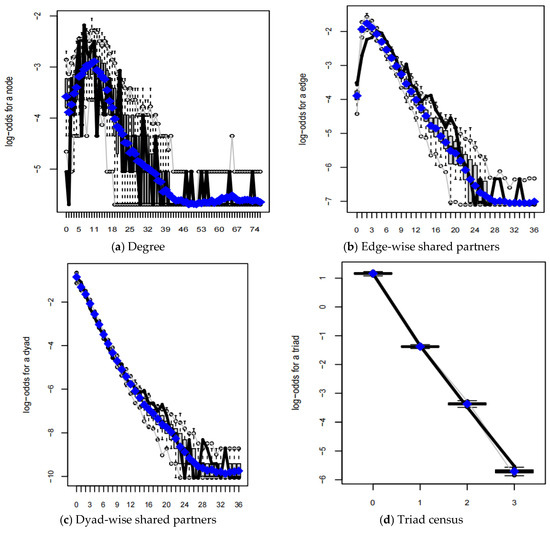

To assess model fit, in addition to using model selection criteria (such as AIC or BIC), graphical methods can be employed to visualize how well the predicted network matches the observed network [16].

Therefore, to further evaluate the fit of Model 4, we conducted a goodness-of-fit (GOF) test, using graphical methods to compare the simulated network with the observed network across relevant statistical indicators. Four commonly used network statistics were selected for this comparison: degree, edge-wise shared partners, dyad-wise shared partners, and triad census. Figure 3 presents the goodness-of-fit plots for the four indicators. By observing how well the point distributions of simulated networks align with the observed network in key structural features, we can intuitively assess the model’s goodness-of-fit.

Figure 3.

Goodness-of-fit diagnostics.

The first plot shows the degree distribution, representing the number of direct connections a VC firm has within the network. The second plot displays the distribution of edgewise shared partners, that is, the number of common neighbor nodes between a pair of co-investing firms, reflecting the network’s clustering level. The third plot presents the distribution of dyad-wise shared partners, which refers to the number of common neighbors between any two VC firms. The fourth plot illustrates the distribution of triads, the smallest closed units composed of three nodes, which can take different connection patterns [16]. The vertical axis represents the logit of relative frequency for the corresponding metric.

The vertical axis represents the log-odds ratio of each metric. The horizontal axis represents the configuration of the network statistics. The black line represents the observed value of a given network statistic in the venture capital network, while the gray area indicates the range covered by 95% of the simulated networks. When the black line falls within the gray area, it indicates that the simulated networks adequately capture the structural features of the actual venture capital network. From Figure 3, it can be observed that, overall, the black lines for all four network structure metrics largely fall within the gray 95% confidence intervals. This result suggests that the simulated networks closely resemble the observed network in terms of key structural features.

Therefore, Model 4 demonstrates a strong goodness-of-fit, confirming the model’s robustness in capturing the formation mechanisms of the venture capital network.

4.4. Further Research: Testing the Substitution Mechanism of Venture Capitalists’ Informal Networks

The results show that informal networks among venture capitalists significantly facilitate the formation of venture capital networks. This finding confirms that in China’s relationship-oriented society, even in a capital market environment with underdeveloped formal institutions, social network ties among venture capitalist can still promote the establishment of inter-organizational network relationships.

The underlying logic of this relationship can be explained as follows: institutional environments vary significantly across China’s provinces and cities. For instance, fiscal decentralization creates regional competition, leading venture capital firms in different areas to face varying levels of policy incentives. Moreover, regions differ substantially in terms of governance quality, the maturity of financial market institutions, contract enforcement mechanisms, and the overall business climate. As a result, the formal institutional environment is inconsistent across regions.

When actors operate in similar institutional environments, they face the same policies and regulations and are subject to common norms and rules [61]. This leads to similar behaviors among actors, enhances mutual trust, and reduces uncertainty and costs of collaboration [62]. Balland et al. [63] argue that institutional similarity functions as a “glue,” forming the foundation for the establishment of cooperative relationships. Such similarity supports stable partnerships and enhances knowledge exchange and mutual learning [61]. Conversely, when institutional environments differ substantially, organizations are more likely to face transaction risks and higher transaction costs. Therefore, to reduce risk, institutional consistency has become an important factor for investment institutions in deciding whether to establish cooperative relationships.

However, when venture capitalists from different investment firms share personal relationships, such as alumni or professional ties, their reliance on formal institutional alignment diminishes. This is because trust embedded within informal networks enhances implicit loyalty, reduces the potential opportunistic behavior, and mitigates transaction risks and costs. To some extent, this reduces the risks arising from differences in institutional environments, thereby helping to overcome collaboration barriers when the institutional environments unbalanced. That is, trust within informal networks compensates for the shortcomings caused by differences in institutional environments. Therefore, under the influence of trust among venture capitalists, investment firms can still establish network partnerships even when institutional environments are imperfect or inconsistent. Institutional consistency is no longer a necessary precondition for collaboration. A reasonable inference is that when informal networks among venture capitalists are considered, the reliance on and requirement for formal institutional alignment diminishes, and the positive effect of institutional similarity on venture capital network formation is weakened.

To empirically test this substitution mechanism, this study constructs an institutional similarity network (Edgecov_Ins) using two different approaches. One approach, following prior research [64], posits that when two venture capital firms are located in the same province, they typically face similar institutional constraints and regulatory environments. This similarity fosters alignment in their governance structures, operational logic, and management practices, thereby facilitating the formation of cooperative consensus. Accordingly, if two VC firms are situated in the same province or city, the corresponding element in the matrix is assigned a value of 1; otherwise, the value is 0.

The results are presented in Table 4. Model 5 includes only the institutional similarity network and excludes informal networks. The results show that the coefficient for the institutional similarity network (Edgecov_Ins) is significantly positive (θ = 0.148, p < 0.05), indicating a significant positive effect on the formation of the venture capital network. Models 6 and 7 build on Model 5 by incorporating the venture capitalists’ alumni network and shared employment experience network, respectively. In Model 6, the coefficient for the shared employment experience network is significantly positive (θ = 0.379, p < 0.001), whereas the coefficient for the institutional similarity network is positive but not significant (θ = 0.128, p > 0.05). In Model 7, the coefficient for the alumni network is significantly positive (θ = 0.127, p < 0.001), whereas the coefficient for the institutional similarity network is positive but not significant (θ = 0.124, p > 0.05). Compared with Model 5, the significance of the coefficient for the institutional similarity network is weakened. This indicates that informal networks of venture capitalists function as a trust mechanism, which can reduce the reliance on and requirement for formal institutional alignment when establishing syndicate relationships. In other words, informal networks serve as a compensatory mechanism, effectively substituting for deficiencies in formal institutional.

Table 4.

Results of testing the substitution mechanism in venture capitalists’ informal networks: Formal institutions measured by geographical co-location.

An alternative approach, following prior research [65], regional institutional differences in China primarily take the form of regional barriers and local protectionism. The resulting inconsistencies in standards, regulations, and law enforcement lead to administrative monopolies and market fragmentation. This fragmentation impedes the flow of resources across the country and hampers cooperation among investment firms. Therefore, we measure the institutional similarity using the similarity in the level of local protection. Specifically, we employ the regional consumer retail price index as a proxy, calculated using the following formula:

represents the institutional similarity between the regions where investment firms and are located. And represent the retail price indices of the regions where investment firms and are located, respectively. represents the maximum difference in the retail price indices across all regions.

The results are presented in Table 5. In Model 5, the coefficient of the institutional similarity network (Edgecov_Ins) is positive and significant (θ = 0.298, p < 0.05), indicating that institutional similarity network significantly promotes the formation of venture capital network. Models 6 and 7 build on Model 5 by incorporating the venture capitalists’ alumni network and shared employment experience network, respectively. In Model 6, the coefficient of the shared employment experience network is significantly positive (θ = 0.374, p < 0.001), whereas the coefficient for the institutional similarity network is positive but not significant (θ = 0.271, p > 0.05). In Model 7, the coefficient for the alumni network is significantly positive (θ = 0.125, p < 0.05), whereas the coefficient for the institutional similarity network is positive but not significant (θ = 0.263, p > 0.05). Compared with Model 5, the significance of the coefficient for the institutional similarity network is weakened. The results also indicate that informal networks among venture capitalists can serve as an effective compensatory mechanism, mitigating and substituting for deficiencies in formal institutions.

Table 5.

Results of testing the substitution mechanism in venture capitalists’ informal networks: Formal institutions measured by local protectionism.

Additionally, in the above research results, although the p-values of the institutional similarity network in Models 6 and 7 are greater than 0.05, indicating that informal networks may have a certain substitution effect, a larger sample or longitudinal data may help further clarify this pattern.

4.5. Robustness Test

To further assess the robustness of our findings, this study conducts robustness test using two different approaches.

The first approach involves replacing certain key variables. We re-measure the venture capital network and the informal networks of venture capitalists using a binary matrix method, followed by a robustness test. Specifically, the venture capital network was redefined as a binary adjacency matrix, where an element is set to 1 if two investment institutions co-invested in the same enterprise, and 0 otherwise. The alumni relationship network was similarly defined: an element equals 1 if venture capitalists from two institutions share the same educational background, and 0 otherwise. The shared employment experience network was also constructed as a binary matrix, where an element equals 1 if venture capitalists from two institutions previously worked at the same organization. Additionally, we measured the network densities of both types of networks to ensure structural comparability between the binary and weighted networks in the robustness tests. The results indicate that the binary and weighted networks for the venture capital network, the alumni network, and the shared employment experience network maintained similar densities, with differences of 0.018, 0.058, and 0.006, respectively. This ensures structural similarity in the robustness tests. The network density results are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Comparison of network densities.

The robustness test results are shown in Table 7. As shown, Model 4 yields an AIC value of 6014 and a BIC value of 6155. Compared to other model specifications, Model 4 continues to exhibit the lowest AIC and BIC values, confirming it as the optimal model. In addition, the coefficient significance results for Model 4 remain consistent with those obtained in earlier analyses. These findings confirm that the model is robust to alternative specifications of network construction.

Table 7.

Robustness test using variable substitution.

The second approach assesses robustness by redefining the sample selection criteria. Specifically, we set the threshold for investment activity to at least four deals and re-estimate the models based on the resulting sample. The results are presented in Table 8. As shown in Table 8, Model 4 incorporates all variables at the network-structural, venture capital firms, and venture capitalist levels, with an AIC of 5266 and a BIC of 5403. Compared with the other models, Model 4 exhibits better overall fit and can therefore be regarded as the preferred specification. In addition, the significance tests of the variables in Model 4 are consistent with the earlier results, indicating that the findings of this study are robust.

Table 8.

Robustness test using sample selection with adjusted thresholds.

5. Research Conclusions and Implications

5.1. Research Conclusions

Compared with capital markets in developed countries, the development of formal institutions in China remains relatively slow and incomplete. Theoretically, this should hinder the growth of the VC industry by exacerbating agency problems, transaction frictions, and opportunism among syndicate partners, thus reducing inter-firm collaboration and impeding network formation. However, in practice, China’s VC industry has expanded rapidly and demonstrates a clear trend toward networked development.

To better understand this phenomenon, this study establishes a multi-level network embedding analytical framework and employs ERGM to integrate multiple network factors—including investor-level, firm-level, and endogenous network structures—into a unified analysis, systematically revealing the multi-level mechanisms underlying the formation of venture capital networks. The main findings are as follows:

- (1)

- Guided by network self-organization logic, the study examines two key structures: triad closure structure and two-path structure. The results show that, compared to the 2-path structure with an intermediary function, triad closure structure is more likely to embed in venture capital network. In essence, venture capital firms with shared partners are more likely to form direct collaborations rather than relying on intermediaries. Accordingly, it suggests that triad closure structure with transitive functions can most effectively promote network formation through the transmission of trust.

- (2)

- Following a market-oriented logic, the study finds that geographic distance network negatively influences venture capital network formation. Greater spatial separation between VC firms increases information asymmetry risk and raises monitoring costs, thereby reducing the likelihood of networks formation. In contrast, knowledge proximity networks—based on industry, stage, and region—positively affect VC network formation. VC firms with shared knowledge backgrounds benefit from common cognitive frameworks, which reduce communication costs, foster trust, and improve both decision-making and post-investment coordination. Thus, VC firms show a preference for partners with similar knowledge backgrounds.

- (3)

- Based on the relationship-oriented logic, the study explores the cross-layer influence of venture capitalists’ informal networks—such as alumni ties and shared employment experience—on inter-organizational networks. The results show that informal network significantly increase the probability of VC network formation. This implies that these relationships go beyond private social bonds; they can facilitate the formation of venture capital networks through trust and resource sharing. Furthermore, the study incorporates institutional similarity networks to further examine how venture capitalists’ informal networks can complement and even replace formal institutions. It confirms that, in contexts with weak formal institutions, venture capitalists’ informal networks can facilitate cooperation among investment firms through mechanisms that do not fully align with formal institutions.

5.2. Research Contribution

The contribution of this study lies in the following aspects:

- (1)

- While existing studies have used ERGM to explore how venture capital networks form, they still rely mostly on dyadic homophily logic when including inter-organizational similarity factors in their models. That is, they explain cooperation tendencies between firms using only pairwise characteristics, rather than truly examining this relationship at the broader network level. However, as investment activities become increasingly networked, the relationships among venture capital firms now exhibit systematic network-level characteristics. Based on this, the study extends inter-organizational relationships from pairwise features to the network level and incorporates them into the ERGM model to examine interactions between different networks from a “network-on-network” perspective. It moves beyond the reliance on dyadic homophily logic in previous research and offers new perspectives and empirical avenues for understanding the formation of venture capital networks.

- (2)

- In studies on the formation mechanisms of venture capital networks, this research adopts an internal venture capitalist perspective and extends it to the network level, revealing the cross-level influence of venture capitalist informal networks on the formation of inter-organizational collaboration networks. It addresses the limitations of previous studies, which largely followed a market-oriented logic, focused on organizational-level factors, and paid little attention to the role of internal relationships in network formation. At the same time, previous studies on network structure have mostly focused on indicators such as size, density, centrality, and reciprocity. In comparison, they paid little attention to triad closure and two-path structures. This study incorporates these two types of structures into the model, enriching the research on factors influencing venture capital network formation and deepening the understanding of how such networks develop.

- (3)

- Based on China’s unique institutional and cultural context, this study empirically examines how informal institutions, represented by personal networks, can substitute for and complement formal institutions, promoting the formation of venture capital networks when formal institutions fail. This provides new empirical evidence on the role of personal networks in environments with weak formal institutions, overcomes the limitations of previous research that focused mainly on theoretical discussion, and deepens our understanding of how venture capital networks are formed.

5.3. Managerial Implications

Based on the above findings, this study offers the following managerial recommendations:

- (1)

- VC firms should transition from passive network participants to proactive network architects, intentionally building closed triadic structures centered around themselves to form highly trusted and collaborative networks. By doing so, they can obtain more stable and reliable informational advantages and foster richer cooperation opportunities. For example, VC firms may regularly organize joint due diligence activities and co-investment meetings to introduce partners to one another, thereby forming triadic or multi-party collaboration chains. In addition, VC firms can develop a partnership matrix to assess the linkages among existing partners, identify potential interconnection opportunities, and update these assessments regularly. VC firms can learn from Hillhouse Capital’s approach by building a “shareable and collaborative” investment ecosystem that integrates portfolio companies, LPs, and strategic partners into a unified resource pool. Through creating platforms for sharing industry-chain information and government resources, they can facilitate resource coordination among stakeholders and form a closed-loop network of “investment–industry–services”.

- (2)

- Institutions should adopt a dual-cooperation strategy that emphasizes knowledge alignment while actively addressing geographic barriers. When selecting network partners, firms should prioritize matches in industry, investment stage, and regional expertise to enhance joint decision-making and post-investment coordination. At the same time, they should apply measures to reduce the negative impact of geographic distance on collaboration. Specifically, firms can develop a “knowledge–geography matching assessment matrix” to evaluate potential partners based on industry, investment stage, and regional experience, giving priority to those with high knowledge alignment as collaboration partners. In addition, for highly compatible partners who are geographically distant, firms can adopt specific measures such as establishing remote communication channels, holding regular video conferences, conducting joint site visits, and participating together in industry events, in order to address the information asymmetry and monitoring costs caused by distance.

- (3)

- Investment firms should systematically manage and maintain managers’ personal informal networks—such as alumni and former colleagues—as strategic assets. Specifically, firms can regularly organize activities among managers and periodically review core team members’ alumni networks and work experiences to identify high-value relationships. They can also establish referral systems through shared contacts, hold informal knowledge-sharing meetings, and maintain ongoing communication through personal channels to strengthen relationships. In addition, firms should utilize informal mechanisms, particularly under high cooperation uncertainty, to facilitate communication and collaboration. For example, when entering new markets or engaging in first-time joint investments, firms can prioritize informal relationships to establish initial trust, thereby promoting smooth cooperation. At the same time, it is important to balance the reliance on informal and formal relationships. Excessive reliance on informal networks may lead to unethical or corrupt behaviors and the formation of closed cliques, thereby reducing exposure to diverse deal flows. For example, such closed circles can foster opportunistic behaviors and confine collaborations to existing partners, hindering the entry of potentially valuable new partners [44]. To mitigate these risks, firms should avoid having all network partners drawn solely from alumni or former colleagues.

In addition, firms should establish standardized trust mechanisms and implement compliant interaction practices to ensure that informal relationships among venture capitalists are legal and legitimate. For mafia-like social capital, firms should enforce institutional constraints to prevent improper behaviors, such as insider trading or misappropriation of funds, from disrupting market competition.

5.4. Limitations and Future Directions

The sample in this study covers data up to 2021, and the selection criterion was that a venture capital firm must have at least three investment events. The study lacks recent data, and the investment event threshold is relatively fixed. Future research could incorporate data from 2022 to 2024 and beyond, adjust the sample selection criteria, and set the investment event threshold to at least 2 or at least 4, in order to further deepen the analysis through group comparisons.

In addition, this study examines network formation mechanisms from a primarily static perspective, while venture capital networks exhibit dynamic evolutionary characteristics. Future research could incorporate dynamic network models to investigate how network structures, inter-organizational relationships, and personal networks interact over time to shape the evolution of the network. This would help reveal the dynamic logic underlying network formation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.G. and Y.X.; methodology, Y.G.; software, Y.G.; validation, Y.G. and Y.X.; formal analysis, Y.G.; resources, Y.X. and Y.Y.; data curation, Y.G.; Writing—original draft, Y.G. and Y.X.; Writing—review & editing, Y.X. and Y.Y.; supervision, Y.X.; funding acquisition, Y.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the MOE (Ministry of Education in China) Liberal Arts and Social Sciences Foundation (Grant No. 22XJA630007), the Natural Science Basic Research Program of Shaanxi Province (Grant No. 2024JC-YBMS-580) and the Beijing Wuzi University (Grant No. BWUISS09).

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Girdauskiene, L.; Venckuviene, V.; Savaneviciene, A. Crowdsourcing as a key method for start-ups overcoming valley of death. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Yin, J.; Jiang, H.; Wei, D.; Xia, R.; Ding, Y. Venture capital syndication network structure of public companies: Robustness and dynamic evolution, China. Systems 2023, 11, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Xu, M.; Wang, W.; Xi, Y. Venture capital network and the M&A performance of listed companies. China Financ. Rev. Int. 2021, 11, 92–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, E.; Kim, B.T.S. Overcoming uncertainty in novel technologies: The role of venture capital syndication networks in artificial intelligence (AI) startup investments in Korea and Japan. Systems 2024, 12, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, L.; Cao, Y. Understanding investor co-investment in a syndicate on equity crowdfunding platforms. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2023, 123, 1599–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lang, Z.; Duan, J.; Zhang, H. Heterogeneous venture capital and technological innovation network evolution:Corporate reputation as mediating variable. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 51, 103478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezeshkan, A.; Smith, A.; Fainshmidt, S.; Zhang, J. Risk, capabilities, and international venture capital syndication in China. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 25, 1671–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Luo, J.D.; Rong, K. How do venture capitals build up syndication ecosystems for sustainable development? Sustainability 2020, 12, 4385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arundale, K. Syndication and cross-border collaboration by venture capital firms in Europe and the USA: A comparative study. Venture Cap. 2020, 22, 355–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theisen, M.; Isaak, A.; Lutz, E. Organizational homophily of family firms: The case of family corporate venture capital. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2025, 63, 719–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourjade, S. The role of expertise in syndicate formation. J. Econ. Manag. Strateg. 2021, 30, 844–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]