Abstract

Leader–member relationships shape public sector performance, yet how leader–member exchange (LMX) operates through capability and motivation pathways remains underexplored. Drawing on social information processing and career construction theories, this study examines how LMX quality influences civil servant performance through career adaptability and perceived social impact. Moderated mediation analyses of survey data from 363 civil servants in Province A, China, reveal that higher-quality LMX enhances career adaptability and perceived social impact, which, in turn, predict higher task performance and organizational citizenship behavior. However, LMX differentiation weakens these positive effects when perceived as high. In practice, public agencies should prioritize high-quality, low-differentiation LMX systems that enhance civil servants’ performance.

1. Introduction

Workplace relationships fundamentally shape organizational performance, particularly in public administration, where complex institutional environments demand strong relational coordination [1]. Leader–member exchange theory emphasizes the quality of dyadic relationships between leaders and subordinates as a critical mechanism shaping employee attitudes and behaviors [2]. High-quality leader–member exchange (LMX) is characterized by mutual trust, respect, and liking, providing employees with greater access to resources, support, and development opportunities, whereas low-quality LMX relies more on formal contracts and limited interaction [3]. While extensive private-sector research demonstrates LMX’s positive effects on performance, commitment, and reducing counterproductive behaviors [4,5,6], public sector contexts may exhibit distinct mechanisms and boundary conditions.

Public organizations face distinctive challenges that differentiate them from private firms—limited market signals, purchaser–beneficiary separation, competing stakeholder demands, and a strong emphasis on procedural fairness and equality [1,7]. In bureaucratic settings characterized by high formalization and hierarchical authority, civil servants operate under deeply institutionalized norms that prioritize equitable treatment over performance-based differentiation [1]. These institutional features render relational mechanisms particularly salient: formal rules and material incentives often prove insufficient, and employee motivation and performance depend heavily on the quality of interpersonal relationships with their supervisors. Accordingly, examining how LMX operates in public administration—and under what conditions—is essential for theory and practice.

Despite the theoretical promise of LMX in public management, existing research has revealed two critical gaps. First, while preliminary studies show that high-quality LMX reduces turnover intentions and enhances work engagement among civil servants [8,9,10], the mechanisms linking LMX to job performance remain underexamined. Specifically, LMX influences performance through dual complementary pathways: a motivation pathway via perceived social impact and a capability pathway via career adaptability. These mechanisms are particularly salient in public administration, where civil servants’ performance depends critically on prosocial motivations to serve the public interest and the adaptive capacity to navigate complex, ambiguous institutional demands [11,12]. These two pathways are functionally complementary: perceived social impact reflects the proximal and affective motivational energy that fuels immediate engagement, whereas career adaptability represents the long-term adaptive capacity for handling evolving role complexity—two functionally distinct yet complementary forms of psychological capital. However, empirical evidence of this dual-pathway model in public organizations remains limited. In addition, prior research has not adequately examined how the public sector’s institutional emphasis on fairness and equality shapes the operation of these pathways. The role of LMX differentiation—the extent to which leaders form varying-quality relationships with different subordinates [13,14]—remains overlooked in public administration, despite its potential to signal distributive unfairness in contexts where equitable treatment is normatively expected.

This study addresses these gaps by developing and testing a moderated mediation model that explains how LMX influences civil servant performance through dual pathways. Drawing on social information processing theory [15], we propose that high-quality LMX supplies positive social cues that heighten the perceptions of work-related social influence, stimulate intrinsic motivation, and improve performance. Concurrently, building on career construction theory [16], we argue that high-quality LMX offers a supportive context and developmental opportunities that build career adaptability, thereby enhancing performance.

Critically, we extend these perspectives by theorizing that the public sector’s institutional emphasis on procedural fairness and equality makes these pathways vulnerable to disruption. Unlike private-sector settings, where performance-based differentiation may be acceptable, the bureaucratic norms of public organizations render any visible relational inequality highly consequential. To capture this institutional dynamic, we introduce perceived LMX differentiation (PLMXD) as a critical boundary condition. While LMX reflects an individual’s own exchange quality with their leader, PLMXD represents employees’ subjective perceptions of relational disparities within their work unit—a distinct social–contextual cue that fundamentally alters how individuals interpret their organizational environment [13,14]. Drawing on justice theory [17,18], we argue that when employees perceive that their leader forms varying-quality relationships with different team members, they interpret this differentiation as a signal of distributive unfairness and procedural bias. Such perceived relational inequality triggers negative emotions and cognitions. It prompts employees to question their own status and organizational fairness, thereby eroding the motivation- and capability-related benefits of high-quality LMX. Conversely, when differentiation is low, the fairness and equality norms reinforce trust and cooperation within the work unit, amplifying LMX’s positive influence.

We test this moderated mediation model using two-wave survey data from 363 grassroots civil servants in Province A, China, employing structural equation modeling to assess the proposed relationships. This study makes three distinctive theoretical contributions to public management research. First, by conceptualizing perceived social impact as a subjective cognitive outcome of the way individuals process work-related information, we extend social information processing theory to illustrate how relational cues help members interpret the social influence of their work—a mechanism particularly relevant in public service, where mission-driven motivation is central. Second, drawing on career construction theory, we highlight the supportive role of relational resources in fostering civil servants’ career adaptability, thereby extending the theory beyond individual traits to the relational mechanisms that promote adaptive growth in bureaucratic settings. Third, and most critically, we theorize and empirically demonstrate that LMX differentiation operates as a critical social cue that shapes civil servants’ performance. In public administration—where procedural justice, equity, and bureaucratic accountability are deeply institutionalized—LMX differentiation is more likely to be construed as favoritism or unfairness than in private firms. Such differentiation not only reflects the structural features of public organizations but also profoundly influences employees’ role perceptions and career development, thereby deepening our understanding of micro-level relational dynamics in public systems. By clarifying these mechanisms and boundary conditions, this study advances both LMX theory and public management scholarship, offering insights into how public leaders can foster employee performance.

2. Theory and Hypotheses

According to the social information processing theory [15], individuals’ work attitudes and perceptions are shaped by social cues in their environment. In high-quality LMX relationships, the leader’s trust, support, and respect [2,3] signal to their employees that their work is valued, enhancing their belief that their efforts positively impact others—thus contributing to their perceived social impact [19]. We propose perceived social impact as a key motivational mediator linking LMX to civil servants’ performance, as it is particularly salient in public organizations for two reasons. First, perceived social impact resonates strongly with public service values that emphasize collective service and public welfare [11,20]. Civil servants are intrinsically motivated by the belief that their work benefits society, and perceived social impact captures this core prosocial dynamic [19]. Second, given the complexity and ambiguity inherent in public sector work [12,21], perceived social impact helps civil servants connect their daily tasks to broader societal goals, enhancing their sense of meaning and engagement [22,23]. Unlike generic motivational constructs, perceived social impact specifically addresses how relational quality translates into prosocial motivation—a particularly critical mechanism in public service contexts where work fundamentally serves others.

In high-quality LMX relationships, leaders provide essential support, encouragement, and career investment for their subordinates, helping civil servants overcome resource shortages. This encourages civil servants to realize that their work is valued by the organization, providing them with the social cue that “my work benefits others” [22]. High-quality LMX relationships also create deeper, more open communication channels. Leaders can provide honest, constructive feedback and advice, helping civil servants better connect their daily tasks with the public mission [2]. This communication process enables civil servants to understand that even mundane administrative tasks contribute to social welfare, thus giving their work deeper meaning and enhancing their perceived social impact [19]. From a complementary social exchange theory perspective [24,25], high-quality LMX creates reciprocal obligations built on mutual trust and investment. When leaders invest in subordinates through career development opportunities and socioemotional support, subordinates feel obliged to reciprocate [4,26]. This reciprocity manifests as increased perceived social impact—employees feel their actions matter both to the leader who has invested in them and to the public they serve [27]. The affective connection in LMX relationships further amplifies this perception. Mutual regard between leaders and subordinates fosters more frequent work interactions [3]. Through these interactions, the leader’s commitment is interpreted and internalized as a model of meaningful service, strengthening the civil servant’s sense of social impact [28]. When civil servants identify with committed leaders and observe their prosocial behaviors, they more readily link their own efforts to social contributions, reinforcing their perceptions of exerting a positive impact on others and society.

When civil servants’ perceived social impact increases, this positive recognition drives their performance and OCB. In the public sector, this impact is particularly important as it is closely linked to their intrinsic public service mission [20]. When civil servants recognize that their actions benefit others, their personal efforts are seen as achieving positive outcomes for others. This awareness includes an assessment of their own abilities and the expected results, meaning they believe their efforts can lead to an effective performance that will benefit others [19]. This foresight inspires them to invest the effort and complete their tasks while adhering to high standards, thus improving task performance. Furthermore, perceived social impact helps convert professional values into intrinsic motivation. When civil servants realize that their work is meaningful to the public, they develop a stronger sense of social responsibility and mission. This emotionally driven understanding encourages them to engage in behaviors beyond formal duties, such as helping colleagues or taking on additional responsibilities. In fact, research indicates that when employees recognize that their actions can benefit others, they are more motivated to exert effort [29]. Their actions are no longer merely directed to complete tasks but are driven by a commitment to public service and a sense of social responsibility. This heightened prosocial motivation directly enhances both in-role task performance and extra-role organizational citizenship behaviors [30]. Therefore, enhancing perceived social impact through high-quality LMX relationships will directly improve civil servants’ task performance and OCB.

Accordingly, Hypothesis 1 was proposed, which comprised the following:

Hypothesis 1a:

LMX positively influences grassroots civil servants’ task performance through the enhancement of perceived social impact.

Hypothesis 1b:

LMX positively influences grassroots civil servants’ OCB through the enhancement of perceived social impact.

According to career construction theory [16,31], career adaptability is defined as a psychological resource reflecting one’s readiness to deal with current and anticipated career tasks, transitions, and challenges [32]. We propose career adaptability as another key mediator linking LMX to civil servants’ performance, functionally distinct from the pathway represented by perceived social impact. While perceived social impact reflects proximal affective motivational energy—the immediate sense of purpose derived from perceiving one’s work as socially impactful—career adaptability represents the long-term adaptive capacity acquired through psychosocial resources [33,34]. These are complementary forms of psychological capital operating through different mechanisms: perceived social impact addresses civil servants’ performance motivations, whereas career adaptability addresses whether they possess the capability to translate motivation into sustained performance. Career adaptability is particularly salient in public sector contexts. First, public administration involves evolving governance demands, complex citizen interactions, and frequent policy reforms [23], requiring civil servants to continuously adapt to shifting priorities and resource constraints. Career adaptability comprises the psychological readiness and self-regulatory competencies necessary to navigate these challenges. In addition, in bureaucratic organizations where career paths depend heavily on supervisory relationships [35,36], career adaptability represents converting relational resources from LMX into proactive career management and problem-solving abilities.

Career construction theory views career building as a psychosocial activity that integrates the self with society [16]. It identifies four core dimensions of career adaptability: concern (career planning and future orientation), control (responsibility for career decisions), curiosity (exploration of opportunities), and confidence (problem-solving self-efficacy) [31,33]. We argue that high-quality LMX functions as a developmental context that systematically enhances all four dimensions. As a social exchange relationship grounded in mutual obligation and reciprocity, LMX provides employees with critical career development resources [4]. Subordinates in high-quality LMX relationships receive support, challenging assignments, increased responsibility, decision-making capabilities, and access to information from their leaders [4,37,38]. These experiences foster career concern by clarifying long-term trajectories, enhance career control by granting autonomy and responsibility, stimulate career curiosity through exposure to diverse tasks and learning opportunities, and build career confidence through mastery experiences and positive feedback. In high-quality LMX relationships, frequent interactions and participation in decision-making help reduce uncertainty and ambiguity in career development [4,39], enabling civil servants to believe they can handle work-related challenges and proactively shape their career paths. According to the conservation of resources theory [40,41] and the resource-based view [42], high-quality LMX serves as a social resource enabling the accumulation of cognitive and emotional capital. Career adaptability functions as a conversion hub that mobilizes these accumulated resources into proactive coping and a problem-solving capacity [43]. Compared with the private sector, grassroots civil servants’ career development paths and access to resources depend more heavily on internal organizational hierarchies. In this context, LMX is not merely a working relationship but a vital channel through which employees access developmental resources, build positive self-conceptions, and cultivate career adaptability.

As a psychosocial resource, career adaptability has a significant impact on an employee’s task performance and OCB. Employees with higher career adaptability are better able to make long-term plans and adjust to their work environments, thereby improving job performance [44]. They tend to demonstrate greater work engagement and proficiency [45]. In contrast, individuals with limited adaptability may encounter difficulties in career planning and exhibit more negative workplace behaviors [46]. This is also closely related to the process of self-regulation. As an adaptive resource, career adaptability is a self-regulatory ability that enables individuals to address unfamiliar, complex, and ill-defined problems arising from developmental career tasks, career transitions, and job trauma [43]. It allows individuals to broaden, improve, and ultimately realize their self-concept in professional roles, thereby creating a working life and building a career framework [32,47]. Therefore, civil servants with high career adaptability can complete their formal work tasks efficiently. At the same time, their deep understanding of the public interest and abundant psychological resources motivate them to assume additional responsibilities. These extra-role efforts not only enhance organizational effectiveness but also promote public well-being.

Building on the above discussion, Hypothesis 2 was formulated, which comprised the following:

Hypothesis 2a:

LMX positively influences grassroots civil servants’ task performance by increasing career adaptability.

Hypothesis 2b:

LMX positively influences grassroots civil servants’ OCB by increasing career adaptability.

The effects of LMX may not be the same for all civil servants. Team contextual characteristics, particularly the perceived variability in leader–member relationships, shape how individuals interpret and respond to their own LMX quality. We define PLMXD as an individual’s perception of the extent to which the leader forms varying-quality relationships with different team members [13,48]. It captures whether employees perceive an overall uneven or inconsistent relational environment within the team. We argue that PLMXD serves as a critical situational cue that alters the effectiveness of individual LMX relationships. According to the fairness heuristic theory [49,50], individuals use fairness-related information as heuristic cues to judge the trustworthiness and legitimacy of authorities. Perception of a high LMX differentiation signals a violation of distributive and procedural justice norms [51,52], undermining the legitimacy of the leader’s actions and reducing employees’ work motivation [53,54]. This fairness-based mechanism is particularly salient in public-sector organizations, where fairness, procedural justice, and equal treatment are deeply institutionalized norms [1,11].

The relationship between LMX and perceived social impact depends critically on the level of PLMXD. When PLMXD is low, the relational environment is relatively egalitarian and fair. Civil servants can interpret their high-quality LMX relationships as authentic signals that their work is valued and contributes to others [22]. The fairness climate strengthens the support climate, enabling civil servants to perceive that their work benefits the public and their colleagues [55]. Social information processing theory [15] posits that when differentiation is low, the dominant social cue is one of equity and shared support, which strengthens the individual’s ability to recognize the social value of their contributions. In contrast, when PLMXD is high, the strong situation theory [56,57] explains why LMX becomes ineffective. Strong situations are characterized by clear, salient cues that lead individuals to interpret the environment, thus constraining behavioral variance. High PLMXD creates a strong negative situation: the pronounced inequality in leader treatment signals favoritism, fostering a collective belief that the leader’s behavior is normatively illegitimate [53,58]. Even civil servants with high-quality LMX relationships recognize that such advantages stem from relational favoritism rather than the social value of their work. Such differentiation erodes the interpersonal justice climate within teams [59], undermining recognition of their work’s social impact. This powerful fairness violation cue overrides individual relational advantages, leading to uniformly low or non-significant effects of LMX on perceived social impact [57]. Thus, the positive effect of LMX on employees’ perceived social impact is stronger when perceived LMX differentiation is low than when it is high.

Hypothesis 3:

When PLMXD is high, the positive effect of LMX on perceived social impact will weaken.

Building on this moderation logic, we propose a first-stage moderated mediation model. Because PLMXD weakens the relationship between LMX and perceived social impact, the entire indirect pathway from LMX through perceived social impact to performance outcomes will also be conditional on PLMXD. Specifically, when PLMXD is low, civil servants can effectively convert their high-quality LMX into stronger perceived social impact, which in turn enhances task performance and OCB. When PLMXD is high, the strong negative situation undermines this conversion process, attenuating the indirect effects. Thus, Hypothesis 4 was proposed, which comprised the following:

Hypothesis 4a:

The indirect relationship between LMX and task performance via perceived social impact is stronger at lower than at higher levels of PLMXD.

Hypothesis 4b:

The indirect relationship between LMX and OCB via perceived social impact is stronger at lower than at higher levels of PLMXD.

Similarly, the conversion of LMX into career adaptability depends on the perceived fairness of the relational environment. Career construction theory [16,33] posits that individuals construct vocational meaning through interpretive and interpersonal processes, particularly by observing how leaders treat others [4]. In public-sector settings, where performance criteria are ambiguous and promotion pathways rigid, civil servants are highly attuned to cues about fairness. When PLMXD is low, civil servants can interpret their high-quality LMX relationships as legitimate developmental resources that reflect recognition of their competence and potential. This enhances their career concern, career curiosity, career confidence, and career control—the four dimensions of career adaptability [33]. The fair and consistent treatment across the team reinforces the belief that effort and merit will be rewarded, encouraging proactive career management. Conversely, when PLMXD is high, the strong situation theory [57] explains why LMX becomes ineffective. High differentiation signals that resource allocation is based on favoritism rather than merit, creating uncertainty about the effort–reward correlation. These fairness violations act as a powerful negative cue, creating a shared sense that relationships matter more than merit, thereby constraining the LMX-career adaptability pathway and fostering negative work attitudes [5,54]. Such pervasive unfairness disrupts career identity construction, even among those with high-quality LMX [13]. The strong situational constraint suppresses the translation of relational resources into adaptive career strategies, effectively nullifying the developmental benefits of LMX. Thus, the positive effect of LMX on an employee’s career adaptability is stronger when perceived LMX differentiation is low than when it is high.

Hypothesis 5:

When PLMXD is high, the positive effect of LMX on career adaptability will weaken.

Above, we propose a first-stage moderated mediation model. Because PLMXD weakens the relationship between LMX and career adaptability, the entire indirect pathway from LMX through career adaptability to performance outcomes will also be conditional on PLMXD. Specifically, when PLMXD is low, civil servants can effectively convert their high-quality LMX into stronger career adaptability, which in turn enhances task performance and OCB. When PLMXD is high, the strong negative situation undermines this conversion process, attenuating the indirect effects. Thus, Hypothesis 6 was formulated, which comprised the following:

Hypothesis 6a:

The indirect relationship between LMX and task performance via career adaptability is stronger at lower than at higher levels of PLMXD.

Hypothesis 6b:

The indirect relationship between LMX and OCB via career adaptability is stronger at lower than at higher levels of PLMXD.

3. Methods

3.1. Data and Sample

This study was conducted in Province A in Northeast China, which has mid-level economic development. Given the highly hierarchical and standardized nature of China’s public administration [60], its municipal and district/county bureaucracies closely resemble those elsewhere; Province A’s civil service performs typical functions in social governance, policy implementation, and citizen services. This supports the sample’s external validity for studying grassroots civil servants. Although China’s political system differs from liberal democracies, cross-national research indicates that modern bureaucracies share common features in personnel management and organizational functioning [1]. Thus, the mechanisms we identify in workplace relationships and performance have comparative relevance across institutional contexts.

Questionnaires were administered online and anonymously, with respondents informed of the study’s purpose and confidentiality principles. To reduce identity sensitivity and increase willingness to participate, respondents were not required to disclose their specific workplace. During the data collection process, we learned that some participants were affiliated with departments such as the Healthcare Security Bureau, the Human Resources and Social Security Bureau, and the Tax Bureau. Data were collected at two time points to reduce common method bias [61]. At Time 1, participants reported their LMX, PLMXD, and demographic information. Three weeks later, at Time 2, the same participants completed measures of task performance, OCB, perceived social impact, and career adaptability. Following best practices in public administration research [62,63], this temporal separation enhanced the reliability of the measured relationships.

In Wave 1, 1508 questionnaires were collected, of which 767 remained valid after removing those that failed attention checks (e.g., “Please select ‘strongly agree’ for this item”), were incomplete, or were completed in under four minutes. In Wave 2, 1074 questionnaires were collected, with 586 valid responses. Matching responses using participants’ online nicknames yielded a final sample of 363 valid paired responses. Attrition was due to missed follow-ups or unmatched identifiers, a common challenge in field surveys of civil servants. Among the final sample, 67.8% were female, the average age was 35.55 years, average tenure was 11.74 years, 83.2% held a bachelor’s degree or above, and 98% were at or below the section-chief rank—patterns consistent with recent studies of grassroots civil servants in China [64,65,66].

3.2. Measures

The measurement instruments in this study were derived from widely recognized scales established in prior international research. Following Brislin’s [67] guidelines, we applied a translation and back-translation process to adapt all items for local comprehension. Each construct was assessed using a seven-point Likert scale, where 1 indicated “strongly disagree” or “completely inconsistent” and 7 indicated “strongly agree” or “completely consistent.” All measurement items are listed in Table A1.

LMX: This variable was measured using the scale developed by Chen and Tjosvold [68], which includes five items, such as “My manager and I care about each other’s work problems and needs.” In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.941.

PLMXD: This variable was measured using the scale developed by Piccolo et al. [69], which includes four items, such as “Some team members have a positive working relationship with my supervisor, while other team members do not.” In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.859. Due to data availability, this study assessed LMX differentiation at the individual perception level. We used individual-level RLMXD because employees’ subjective perceptions more proximally and validly predict their own attitudes and behaviors than team-level variance, are widely operationalized this way, and align with our individual-level outcomes [70,71,72].

Career adaptability: This variable was measured using the career adaptability scale developed by Maggiori et al. [73]. The scale includes twelve items, such as “I know how to determine the appropriate procedures for each work task.” In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the scale was 0.941.

Perceived social impact: This variable was measured using the scale developed by Grant [19], which includes three items, such as “I am very conscious of the positive impact that my work has on others.” In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the scale was 0.934.

Task performance: This study divided work performance into two dimensions: in-role performance and extra-role performance, corresponding to task performance and OCB, respectively. Task performance refers to behaviors that are formally required within the work role, representing duties that employees must complete to earn compensation and maintain their employment relationship. Task performance was measured using the scale developed by Williams and Anderson [74], which includes five items, such as “meets formal performance requirements of the job.” In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the scale was 0.868.

Organizational citizenship behavior: OCB refers to discretionary behaviors that exceed formal job requirements and benefit the overall functioning of the organization but are not necessarily formally rewarded or recognized. OCB was measured using the scale developed by Taylor [75]. The scale includes seven items, such as “I take time to listen to co-workers’ problems and worries.” In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the scale was 0.881.

Due to data availability constraints, this study used self-reported assessments from grassroots civil servants to collect work performance data. Task performance is closely related to the formal job description and standard operating procedures, rather than the more creative and ambiguous aspects of performance [76]. As task performance is relatively clear, the difference between self-reported and leader-reported performance is normally insignificant [77]. A meta-analysis [78] has also shown that self-reported measurements are consistent with leader reports, lending credence to using self-reported measurements for OCB. Although self-reported data from cross-sectional surveys often raise concerns about common method bias [79], a post hoc Harman’s single-factor test showed that the variance explained by the first factor was below the 50% threshold [75], indicating the minimal impact of common method bias. These results suggest that using self-assessed measures to capture civil servants’ job performance is reliable.

Control variables: Following previous research, this study controlled for individual-level variables, including gender, age, education level, and work tenure. Prior studies have confirmed that these variables may influence employee work performance [80,81]. In the questionnaire, gender was coded as 1 = male and 2 = female; education was coded from 1 to 4 (1 = high school or below, 2 = junior/vocational college, 3 = bachelor’s, 4 = master’s or above). Age and tenure were continuous variables measured in years.

Table 1 presents the univariate descriptive statistics, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, and correlation coefficients for the study variables. Overall, the correlations between the study variables were consistent with our expectations.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, alphas, and correlations.

4. Results

This study employed structural equation modeling to examine the hypothesized relationships [82]. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using Mplus to evaluate the discriminant validity of the six constructs in the research model: LMX, PLMXD, career adaptability, perceived social impact, task performance, and OCB. The hypothesized six-factor model demonstrated an acceptable fit to the data (χ2 = 463.428, df = 215, CFI = 0.964, TLI = 0.958, RMSEA = 0.056, SRMR = 0.040).

To further assess the discriminant validity, we compared the six-factor model with a series of alternative models in which conceptually related constructs were combined. Specifically, in the five-factor model 1, task performance and OCB were combined into one factor. The four-factor model further combined career adaptability and perceived social impact on the basis of the five-factor model 1. The three-factor model combined all Time 2 variables (career adaptability, perceived social impact, task performance, and OCB) into a single factor. The two-factor model further combined all Time 1 variables (LMX and PLMXD) into one factor based on the three-factor model. The one-factor model combined all variables into a single factor.

Chi-square difference tests indicated that the six-factor model provided a significantly better fit than all the alternative models: the five-factor model 1 (Δχ2 = 16.502, Δdf = 5, p < 0.001), four-factor model (Δχ2 = 615.340, Δdf = 9, p < 0.001), three-factor model (Δχ2 = 1516.840, Δdf = 12, p < 0.001), two-factor model (Δχ2 = 2100.935, Δdf = 14, p < 0.001), and one-factor model (Δχ2 = 3648.659, Δdf = 15, p < 0.001). These results support the discriminant validity of the six-factor measurement model.

To establish discriminant validity between LMX and PLMXD, we compared the six-factor model (separating LMX and PLMXD) with the five-factor model 2 (combining them). The six-factor model fit substantially better (χ2 = 463.428, df = 215, CFI = 0.964, TLI = 0.958, RMSEA = 0.056, SRMR = 0.040) than the five-factor model (χ2 = 1053.865, df = 220, CFI = 0.880, TLI = 0.862, RMSEA = 0.102, SRMR = 0.082, Δχ2 (5) = 590.437, p < 0.001; see Table 2). An EFA further supported two factors (KMO = 0.875; Bartlett χ2 = 2485.87, p < 0.001; eigenvalues = 4.81 and 2.09; 70.1% variance), with strong pattern-matrix loadings (LMX: 0.81–0.92, avg. 0.87; PLMXD: 0.65–0.88, avg. 0.78) and no cross-loadings ≥ 0.30. Multicollinearity was not a concern (VIFs: LMX = 1.46, PLMXD = 1.18). Collectively, these results indicate that LMX and PLMXD are related but are empirically distinct constructs that warrant separate modeling.

Table 2.

Results of confirmatory factor analysis.

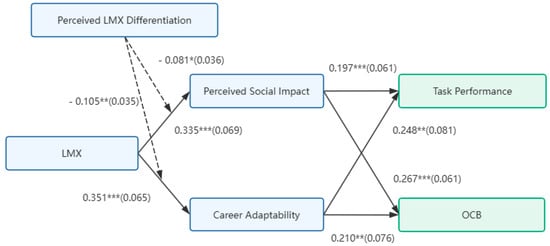

The analysis results are presented in Figure 1 and Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6. Several relationships are statistically significant. LMX has a significant positive effect on perceived social impact (β = 0.335, p < 0.001) and career adaptability (β = 0.351, p < 0.001). In addition, social impact is positively associated with task performance (β = 0.197, p < 0.001) and OCB (β = 0.267, p < 0.001). Career adaptability is also positively associated with task performance (β = 0.248, p < 0.01) and OCB (β = 0.210, p < 0.01).

Figure 1.

Results for the theoretical research model. Note: *** p < 0.001 ** p < 0.01 * p < 0.05.

Table 3.

Results for perceived social impact and career adaptability.

Table 4.

Results for task performance.

Table 5.

Results for OCB.

Table 6.

Moderated mediation effect results for the research model.

Hypotheses 1a and 1b concerning the mediating role of perceived social impact were tested. The results indicate that the indirect effect of LMX on task performance through perceived social impact was positive and significant [indirect effect = 0.066, 95% CI (0.026, 0.129)], and the indirect effect of LMX on OCB through perceived social impact was also positive and significant [indirect effect = 0.090, 95% CI (0.044, 0.155)]. Thus, Hypotheses 1a and 1b were supported.

Next, Hypotheses 2a and 2b concerning the mediating role of career adaptability were tested. The indirect relationship between LMX and task performance via career adaptability was positive and significant [indirect effect = 0.087, 95% CI (0.032, 0.156)], and the indirect relationship between LMX and OCB via career adaptability was positive and significant [indirect effect = 0.074, 95% CI (0.024, 0.137)]. Thus, Hypotheses 2a and 2b were supported.

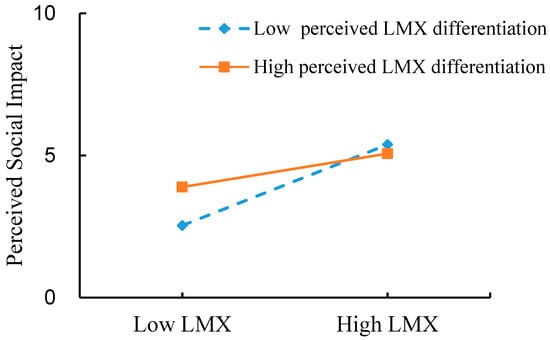

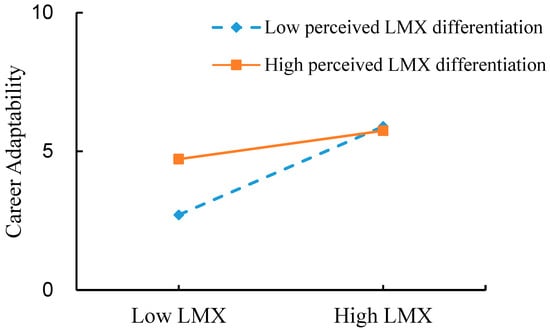

This study further examined the moderating role of PLMXD. The regression analysis indicated that PLMXD significantly moderated the relationship between LMX and perceived social impact (β = −0.081, SE = 0.036, p < 0.05), as well as the relationship between LMX and career adaptability (β = –0.105, SE = 0.035, p < 0.01), supporting Hypotheses 3 and 5. To further interpret these moderation effects, simple slope analyses were conducted. Figure 2 shows that when PLMXD was low (−1 SD), LMX significantly predicted greater perceived social impact (β = 0.474, SE = 0.113, p < 0.001); this effect was weaker when PLMXD was high (+1 SD; β = 0.196, SE = 0.065, p < 0.01). The slope difference was significant (Δβ = −0.278, SE = 0.123, p < 0.05), indicating that PLMXD attenuated the positive effect of LMX on perceived social impact. Similarly, as shown in Figure 3, the positive relationship between LMX and career adaptability was significantly weaker when LMX differentiation was high (β = 0.172, SE = 0.056, p < 0.01) compared with when it was low (β = 0.531, SE = 0.112, p < 0.001). The slope difference was also statistically significant (Δβ = −0.360, SE = 0.121, p < 0.01), further indicating that PLMXD reduced the enhancing effect of LMX on career adaptability.

Figure 2.

Simple slope analysis of the effect of PLMXD on perceived social impact.

Figure 3.

Simple slope analysis of the effect of PLMXD on career adaptability.

Finally, Hypotheses 4a, 4b, 6a, and 6b, which predicted that PLMXD moderates the indirect relationships previously revealed, were examined. Following Preacher et al.’s [83] recommendations, the results show that the indirect effect of LMX on task performance via perceived social impact was stronger under low PLMXD conditions [indirect effect = 0.093, 95% CI (0.038, 0.187)] than under high PLMXD conditions [indirect effect = 0.039, 95% CI (0.010, 0.090)], and the difference between these two effects was significant [difference index = −0.055, 95% CI (−0.133, −0.016)]. Thus, Hypothesis 4a was supported.

Hypothesis 3c predicted that PLMXD moderates the indirect effect of LMX on OCB via perceived social impact. The results show that the indirect effect on OCB via perceived social impact was stronger under low PLMXD conditions [indirect effect = 0.127, 95% CI (0.064, 0.231)] than under high PLMXD conditions [indirect effect = 0.052, 95% CI (0.018, 0.106)], and the difference between these two effects was significant [difference index = −0.074, 95% CI (−0.167, −0.123)]. Thus, Hypothesis 4b was supported.

Hypothesis 6a predicted that PLMXD moderates the indirect effect of LMX on task performance via career adaptability. The results show that the indirect effect of LMX on task performance via career adaptability was stronger under low PLMXD conditions [indirect effect = 0.134, 95% CI (0.075, 0.219)] than under high PLMXD conditions [indirect effect = 0.045, ns], and the difference between these two effects was significant [difference index = −0.089, 95% CI (−0.199, −0.024)]. Thus, Hypothesis 6a was supported.

Finally, Hypothesis 6b predicted that PLMXD moderates the indirect effect of LMX on OCB via career adaptability. We found that the indirect effect of LMX on OCB via career adaptability was stronger under low PLMXD conditions [indirect effect = 0.112, 95% CI (0.034, 0.218)] than under high PLMXD conditions [indirect effect = 0.036, 95% CI (0.012, 0.078)], and the difference between these two effects was significant [difference index = −0.076, 95% CI (−0.173, −0.019)]. Thus, Hypothesis 6b was supported.

5. Discussion

This study examines how LMX shapes civil servants’ in-role performance (task performance) and extra-role performance (organizational citizenship behavior). We propose a relational–motivation/capability–behavioral model in which perceived social impact and career adaptability act as mediators, and PLMXD serves as a moderator. Survey evidence from grassroots civil servants supports these hypothesized relationships and validates the proposed framework.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

The study’s first contribution is deepening our understanding of how LMX influences performance in public organizations. While LMX theory has been extensively validated in the private sector [84,85], its application in public administration remains limited. Public organizations face unique institutional environments—multiple stakeholders, limited incentives, complex evaluation systems, and strong procedural constraints [86]—that may fundamentally alter leader–subordinate dynamics. This study provides empirical evidence for understanding LMX mechanisms in this distinctive context.

The second contribution extends social information processing theory and career construction theory by conceptualizing LMX as a relational mechanism that simultaneously influences motivation and capability. We define “perceived social impact” as the civil servant’s subjective processing of environmental information, illustrating how they interpret work value through leader interactions and thereby deepening the understanding of how social cues shape behavior [15]. This perspective aligns with evidence on the critical role of social work characteristics in performance [87]. Additionally, we demonstrate that relational resources are crucial for developing adaptability in public contexts, enriching career construction theory’s explanatory power in bureaucratic settings.

The third contribution identifies a “motivation–capability dual-pathway” model with distinctive characteristics in public organizations. Perceived social impact and career adaptability constitute the strongest predictors because they jointly index the intrinsic service motivation (“why”) and adaptive competence (“how”) characteristics necessary to navigate complex, dynamic administrative contexts. This model echoes performance theory in that both motivation and ability are essential to performance [88]. It aligns with public service motivation research that emphasizes intrinsic motives [89,90] and highlights the importance of capacity building [91,92]. Importantly, the study clarifies the causal role of career adaptability in public organizations. Unlike in the private sector, adaptability is often regarded as a prerequisite for building high-quality exchanges [93,94]. In the public sector, stable employment and standardized career tracks require leader support for developing adaptability. With employment security and hierarchical management, a civil servant’s growth depends more on their leader’s allocation of resources and guidance than on individual competition [86,95].

The fourth contribution of this study is the introduction of PLMXD into public administration research. It serves as a contextualized construct to capture the subtle dynamics of differentiated leadership practices in public organizations. Our finding that PLMX differentiation weakens the positive effects of high-quality relationships challenges the assumptions of private-sector research, where LMX differentiation has a double-edged nature and is highly context-dependent [13,14]. In public organizations, where fairness, equality, and procedural consistency are deeply institutionalized values, LMX differentiation is perceived not as a legitimate recognition of merit but as favoritism or a relational bias that violates collective justice [1]. Even employees in high-quality relationships experience diminished engagement when they perceive differential treatment within their teams. This finding resonates with the core values of public administration that emphasize procedural justice and equal treatment [96,97], indicating that principles of fairness in public organizations are not only normative requirements but also carry practical managerial value. By introducing LMX differentiation as a key moderating variable, this study reveals the unique mechanism of LMX in the public sector. The results indicate that understanding LMX’s effects requires considering its differentiation within the organizational system, thereby providing an important lens for advancing research on the effectiveness of public-sector governance.

5.2. Practical Implications

Based on the findings, this study offers practical suggestions for public sector managers. First, managers should systematically improve LMX quality by holding regular one-on-one meetings to understand employees’ work challenges and career aspirations, providing targeted guidance and personalized support based on individual strengths. Second, managers should strengthen employees’ perceived social impact by explaining the social value of their work and sharing positive feedback from service recipients. For example, they can share citizen thank-you letters, highlight successful implementations in team meetings, or create visible feedback mechanisms (satisfaction scores, impact reports) that make public welfare contributions tangible. Third, managers should enhance career adaptability through personalized “skill development plans.” In Chinese government departments, this could include: (a) mentor–protégé pairings for specialized competencies, (b) individualized training tracks aligned with career ladders (generalist vs. specialist), (c) development tied to civil service evaluation criteria, and (d) strategic rotational assignments matched to individual needs. Finally, managers should reduce PLMXD by promoting fairness perceptions through transparent opportunity rotation, consistent communication schedules, and visible equity practices. When differential treatment is necessary, it should be based on objective performance and clearly explained to maintain a fair team climate.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study has several limitations. First, all variables were self-reported, raising the risks of social desirability and common method bias. Although we used temporal separation and statistical controls, future research should adopt multi-source designs (e.g., supervisor ratings, peer assessments, objective performance metrics) or dyadic leader–follower designs to mitigate these biases. Second, alternative mediators deserve examination—such as public service motivation and psychological safety—which may operate uniquely in public organizations. Third, additional moderators (e.g., leader fairness, organizational culture, institutional trust) may shape fairness interpretations of LMX differentiation. Fourth, multilevel designs are needed to capture both the individual- and team-level dynamics of LMX differentiation. Fifth, comparative studies across public-sector types (administrative vs. service departments), levels of government, and cultural contexts will enhance generalizability. Finally, our control set is not exhaustive—for example, individual affective orientation was not accounted for—which may affect effect estimates. Future research should incorporate a broader set of theoretically relevant controls. Despite these limitations, this study provides initial evidence of LMX processes in Chinese public administration.

6. Conclusions

This study advances public administration literature by demonstrating that LMX enhances grassroots civil servants’ task performance and OCB through two pathways: strengthening perceived social impact and fostering career adaptability. Critically, however, PLMXD weakens these positive effects, revealing how perceived relational inequality creates powerful contextual constraints that offset leaders’ influence. This finding underscores that relational consistency matters as much as relational quality in shaping performance outcomes in fairness-sensitive bureaucratic systems. These insights refine social information processing theory and career construction theory, revealing how employees’ interpretations of relational cues and developmental opportunities sustain their performance under strong institutional constraints. Practically, the findings highlight the need for public organizations to strengthen both the quality and consistency of leader–member exchanges, enhance employees’ sense of their social impact, and provide developmental pathways that build adaptability. In an era of rising demands on public servants, investing in these relational and developmental processes—alongside transparent, equitable leadership practices—is central to building effective and citizen-focused public organizations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.C., J.Y. and N.Y.; methodology, T.C., J.Y. and N.Y.; software, T.C. and J.Y.; validation, T.C.; formal analysis, T.C.; investigation, T.C.; resources, J.Y. and N.Y.; data curation, T.C.; writing—original draft preparation, T.C.; writing—review and editing, T.C., J.Y. and N.Y.; visualization, T.C. and J.Y.; supervision, J.Y. and N.Y.; project administration, J.Y. and N.Y.; funding acquisition, N.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Measures for the Ethical Review of Life Science and Medical Research Involving Humans promulgated by China and received approval from the Institutional Review Board of Harbin Institute of Technology School of Management. The study was evaluated and approved by the Ethics Committee of Harbin Institute of Technology (Reference No. HIT-2025-20; approved on 6 May 2025). As a non-interventional study involving surveys and questionnaires, all participants were fully informed about the purpose of the research, how their data would be used, and the anonymity guarantees provided. This study does not involve human experimentation as defined in the Declaration of Helsinki, and the questions in the questionnaires have no adverse effects on the mental health status of the respondents. The study uses anonymized data to conduct research, causing no harm to participants and involving neither sensitive personal information nor commercial interests. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are from a provincial-level survey of civil servants in China. During data collection, participants were explicitly assured that their responses would not be disclosed beyond the research team. To honor this informed consent and protect respondent confidentiality, the dataset cannot be shared publicly. Accordingly, the data supporting the findings are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Measurement of Variables in Questionnaires.

Table A1.

Measurement of Variables in Questionnaires.

| Variables | Measures |

|---|---|

| LMX [68] | 1. My manager and I care about each other’s work problems and needs. |

| 2. My manager and I recognize each other’s potential. | |

| 3. My manager and I are inclined to pool our available resources to solve the problems in my work. | |

| 4. My manager and I have confidence in each other’s capabilities. | |

| 5. My manager and I are satisfied with each other’s work. | |

| PLMXD [69] | 1. Some team members have a positive working relationship with my supervisor, while other team members do not. |

| 2. My supervisor has high-quality working relationships with some members of my team, but low-quality working relationships with other team members. | |

| 3. My supervisor has an effective working relationship with some team members, but ineffective working relationships with other team members. | |

| 4. My supervisor tends to develop high-quality working relationships with only a few trusted team members. | |

| Perceived social impact [19] | 1. I am very conscious of the positive impact that my work has on others. |

| 2. I am very aware of the ways in which my work is benefiting others. | |

| 3. I feel that I can have a positive impact on others through my work. | |

| Career adaptability [73] | 1. Thinking about what my future will be like. |

| 2. Preparing for the future. | |

| 3. Becoming aware of the educational and vocational choices that l must make. | |

| 4. Making decisions by myself. | |

| 5. Taking responsibility for my actions. | |

| 6. Counting on myself. | |

| 7. Looking for opportunities to grow as a person. | |

| 8. Investigating options before making a choice. | |

| 9. Observing different ways of doing things. | |

| 10. Taking care to do things well. | |

| 11. Learning new skills. | |

| 12. Working up to my ability. | |

| Task performance [74] | 1. Adequately completes assigned duties. |

| 2. Fulfills responsibilities specified in job description. | |

| 3. Performs tasks that are expected of him/her. | |

| 4. Meets formal performance requirements of the job. | |

| 5. Engages in activities that will directly affect his/her performance evaluation. | |

| OCB [75] | 1. I help others who have heavy workloads. |

| 2. I take time to listen to co-workers’ problems and worries. | |

| 3. I go out of my way to help new employees. | |

| 4. I assist my supervisor with his/her work even when I am not asked. | |

| 5. My attendance at work is above the norm. | |

| 6. I obey informal rules that are developed to maintain order. | |

| 7. I give advance notice when I am unable to come to work. |

References

- Raadschelders, J.; Vigoda-Gadot, E. Global Dimensions of Public Administration and Governance: A Comparative Voyage; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Graen, G.B.; Uhl-Bien, M. Relationship-Based Approach to Leadership: Development of Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) Theory of Leadership over 25 Years: Applying a Multi-Level Multi-Domain Perspective. Leadersh. Q. 1995, 6, 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Maslyn, J.M. Multidimensionality of Leader-Member Exchange: An Empirical Assessment through Scale Development. J. Manag. 1998, 24, 43–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulebohn, J.H.; Bommer, W.H.; Liden, R.C.; Brouer, R.L.; Ferris, G.R. A Meta-Analysis of Antecedents and Consequences of Leader-Member Exchange: Integrating the Past with an Eye Toward the Future. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 1715–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.; Thomas, G.; Legood, A.; Dello Russo, S. Leader–Member Exchange (LMX) Differentiation and Work Outcomes: Conceptual Clarification and Critical Review. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilies, R.; Nahrgang, J.D.; Morgeson, F.P. Leader-Member Exchange and Citizenship Behaviors: A Meta-Analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.K.; Wright, B.E. Connecting the Dots in Public Management: Political Environment, Organizational Goal Ambiguity, and the Public Manager’s Role Ambiguity. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2006, 16, 511–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, M.; Ananthram, S.; Teo, S.T.; Pearson, C.A. Leader–Member Exchange and Relational Quality in a Singapore Public Sector Organization. Public Manag. Rev. 2015, 17, 1379–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Pham, L.N.T.; Vo, A.H.K. Faculty’ Turnover Intention in Vietnamese Public Universities: The Impact of Leader-Member Exchange, Psychological Safety, and Job Embeddedness. Public Organ. Rev. 2023, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesmert, L.; Vogel, R. Following Your Ideal Leader: Implicit Public Leadership Theories, Leader—Member Exchange, and Work Engagement. Public Pers. Manag. 2024, 53, 548–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J.L.; Wise, L.R. The Motivational Bases of Public Service. Public Adm. Rev. 1990, 50, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainey, H.G.; Bozeman, B. Comparing Public and Private Organizations: Empirical Research and the Power of the A Priori. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2000, 10, 447–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, D.J.; Liden, R.C.; Glibkowski, B.C.; Chaudhry, A. LMX Differentiation: A Multilevel Review and Examination of Its Antecedents and Outcomes. Leadersh. Q. 2009, 20, 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Erdogan, B.; Wayne, S.J.; Sparrowe, R.T. Leader-Member Exchange, Differentiation, and Task Interdependence: Implications for Individual and Group Performance. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2006, 27, 723–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salancik, G.R.; Pfeffer, J. A Social Information Processing Approach to Job Attitudes and Task Design. Adm. Sci. Q. 1978, 23, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M.L. The Theory and Practice of Career Construction. Career Dev. Couns. Putt. Theory Res. Work 2005, 1, 42–70. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, J. A Taxonomy of Organizational Justice Theories. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1987, 12, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Conlon, D.E.; Wesson, M.J.; Porter, C.O.; Ng, K.Y. Justice at the Millennium: A Meta-Analytic Review of 25 Years of Organizational Justice Research. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M. The Significance of Task Significance: Job Performance Effects, Relational Mechanisms, and Boundary Conditions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandenabeele, W. Toward a Public Administration Theory of Public Service Motivation: An Institutional Approach. Public Manag. Rev. 2007, 9, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainey, H.G.; Jung, C.S. A Conceptual Framework for Analysis of Goal Ambiguity in Public Organizations. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2015, 25, 71–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M. Relational Job Design and the Motivation to Make a Prosocial Difference. Acad. Manage. Rev. 2007, 32, 393–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.; Hatmaker, D.M. Leadership and Performance of Public Employees: Effects of the Quality and Characteristics of Manager-Employee Relationships. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2015, 25, 1127–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social Exchange Theory: An Interdisciplinary Review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, S.J.; Shore, L.M.; Liden, R.C. Perceived Organizational Support and Leader-Member Exchange: A Social Exchange Perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 82–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settoon, R.P.; Bennett, N.; Liden, R.C. Social Exchange in Organizations: Perceived Organizational Support, Leader–Member Exchange, and Employee Reciprocity. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wen, P.; Luo, L. Leaders’ Calling and Employees’ Innovative Behavior: The Mediating Role of Work Meaning and the Moderating Effect of Supervisor’s Organizational Embodiment. Systems 2025, 13, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karau, S.J.; Williams, K.D. Social Loafing: A Meta-Analytic Review and Theoretical Integration. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 65, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Parker, S.K. 7 Redesigning Work Design Theories: The Rise of Relational and Proactive Perspectives. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2009, 3, 317–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M.L. Career Adaptability: An Integrative Construct for Life-Span, Life-Space Theory. Career Dev. Q. 1997, 45, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porfeli, E.J.; Savickas, M.L. Career Adapt-Abilities Scale-USA Form: Psychometric Properties and Relation to Vocational Identity. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 748–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M.L. Career Construction Theory and Practice. Career Dev. Couns. Putt. Theory Res. Work 2013, 2, 144–180. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, C.W.; Lavigne, K.N.; Zacher, H. Career Adaptability: A Meta-Analysis of Relationships with Measures of Adaptivity, Adapting Responses, and Adaptation Results. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 98, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J.L.; Porter, L.W. Factors Affecting the Context for Motivation in Public Organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1982, 7, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, L. Does Person Organization Fit and Person-Job Fit Mediate the Relationship Between Public Service Motivation and Work Stress Among US Federal Employees? Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, M.C.; Kacmar, K.M. Discriminating among Organizational Politics, Justice, and Support. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2001, 22, 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, C.; Rosen, B. The Leader-Member Exchange as a Link Between Managerial Trust and Employee Empowerment. Group Organ. Manag. 2001, 26, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryee, S.; Chen, Z.X. Leader–Member Exchange in a Chinese Context: Antecedents, the Mediating Role of Psychological Empowerment and Outcomes. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of Resources: A New Attempt at Conceptualizing Stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The Influence of Culture, Community, and the Nested-Self in the Stress Process: Advancing Conservation of Resources Theory. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 50, 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolentino, L.R.; Sedoglavich, V.; Lu, V.N.; Garcia, P.R.J.M.; Restubog, S.L.D. The Role of Career Adaptability in Predicting Entrepreneurial Intentions: A Moderated Mediation Model. J. Vocat. Behav. 2014, 85, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugate, M.; Kinicki, A.J.; Ashforth, B.E. Employability: A Psycho-Social Construct, Its Dimensions, and Applications. J. Vocat. Behav. 2004, 65, 14–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossier, J.; Zecca, G.; Stauffer, S.D.; Maggiori, C.; Dauwalder, J.-P. Career Adapt-Abilities Scale in a French-Speaking Swiss Sample: Psychometric Properties and Relationships to Personality and Work Engagement. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 734–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neureiter, M.; Traut-Mattausch, E. An Inner Barrier to Career Development: Preconditions of the Impostor Phenomenon and Consequences for Career Development. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Fang, T.; Liu, F.; Pang, L.; Wen, Y.; Chen, S.; Gu, X. Career Adaptability Research: A Literature Review with Scientific Knowledge Mapping in Web of Science. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 5986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sui, Y.; Wang, H.; Kirkman, B.L.; Li, N. Understanding the Curvilinear Relationships between LMX Differentiation and Team Coordination and Performance. Pers. Psychol. 2016, 69, 559–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, E.A. Fairness Heuristic Theory: Justice Judgments as Pivotal Cognitions in Organizational Relations. Adv. Organ. Justice 2001, 56, 56–88. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Bos, K.; Lind, E.A.; Wilke, H.A. The Psychology of Procedural and Distributive Justice Viewed from the Perspective of Fairness Heuristic Theory. In Justice in the Workplace; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2012; pp. 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano, R.; Bowen, D.E.; Gilliland, S.W. The Management of Organizational Justice. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2007, 21, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Scott, B.A.; Rodell, J.B.; Long, D.M.; Zapata, C.P.; Conlon, D.E.; Wesson, M.J. Justice at the Millennium, a Decade Later: A Meta-Analytic Test of Social Exchange and Affect-Based Perspectives. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.T.; Martin, R. Beyond Personal Leader–Member Exchange (LMX) Quality: The Effects of Perceived LMX Variability on Employee Reactions. Leadersh. Q. 2008, 19, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, B.; Bauer, T.N. Differentiated Leader–Member Exchanges: The Buffering Role of Justice Climate. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Romá, V.; Le Blanc, P.M. The Influence of Leader-Member Exchange Differentiation on Work Unit Commitment: The Mediating Role of Support Climate1. Psychologica 2019, 62, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mischel, W. The Interaction of Person and Situation. Personal. Crossroads Curr. Issues Interact. Psychol. 1977, 333, 352. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, R.D.; Dalal, R.S.; Hermida, R. A Review and Synthesis of Situational Strength in the Organizational Sciences. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolino, M.C.; Turnley, W.H. Relative Deprivation Among Employees in Lower-Quality Leader-Member Exchange Relationships. Leadersh. Q. 2009, 20, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.; Lee, J.Y. Leader–Member Exchange Level and Differentiation: The Roles of Interpersonal Justice Climate and Group Affective Tone. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2017, 45, 1175–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.H. China’s Local Governance in Perspective: Instruments of Central Government Control. China J. 2016, 75, 38–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of Method Bias in Social Science Research and Recommendations on How to Control It. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luu, T.T. Service-Oriented High-Performance Work Systems and Service-Oriented Behaviours in Public Organizations: The Mediating Role of Work Engagement. Public Manag. Rev. 2019, 21, 789–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piatak, J.S.; Holt, S.B. Disentangling Altruism and Public Service Motivation: Who Exhibits Organizational Citizenship Behaviour? In Public Service Motivation; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, L. Organizational Tolerance for Mistakes and Grassroots Civil Servants’ Responsibility-Taking: An Experimental Study Based on the “Institution–Psychology–Behavior” Framework. Mod. Manag. Sci. 2024, 6, 103–112. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- You, F.; Chen, Z.; Liu, S. All or Nothing, or Waiting in Patience? The Impact and Paradoxical Mechanism of Dual Promotion Expectations on Proactive Behavior Among Grassroots Civil Servants. China Hum. Resour. Dev. 2025, 42, 6–23. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- An, Y.; Li, Y. Fulfilling Duties While Avoiding Responsibility: A Study on the Behavioral Characteristics of Young Grassroots Civil Servants. Contemp. Youth Res. 2025, 3, 82–100. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Brislin, R.W. The Wording and Translation of Research Instruments. In Field Methods in Cross-Cultural Research; Lonner, W.J., Berry, J.W., Eds.; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1986; pp. 137–164. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.F.; Tjosvold, D. Participative Leadership by American and Chinese Managers in China: The Role of Relationships. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 1727–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolo, R.F.; Mayer, D.M.; Ergodan, B.; Uhl-Bien, M. Does LMX Differentiation Help or Hinder Group Processes and Performance. In Proceedings of the 68th Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management, Anaheim, CA, USA, 8–13 August 2008. [Google Scholar]

- James, L.R.; Jones, A.P. Organizational Climate: A Review of Theory and Research. Psychol. Bull. 1974, 81, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidyarthi, P.R.; Liden, R.C.; Anand, S.; Erdogan, B.; Ghosh, S. Where Do I Stand? Examining the Effects of Leader–Member Exchange Social Comparison on Employee Work Behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Bliese, P.D.; Mathieu, J.E. Conceptual Framework and Statistical Procedures for Delineating and Testing Multilevel Theories of Homology. Organ. Res. Methods 2005, 8, 375–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggiori, C.; Rossier, J.; Savickas, M.L. Career Adapt-Abilities Scale–Short Form (CAAS-SF) Construction and Validation. J. Career Assess. 2017, 25, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.J.; Anderson, S.E. Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment as Predictors of Organizational Citizenship and In-Role Behaviors. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J. Goal Setting in the Australian Public Service: Effects on Psychological Empowerment and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Public Adm. Rev. 2013, 73, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshuis, J.; De Boer, N.; Klijn, E.H. Street-Level Bureaucrats’ Emotional Intelligence and Its Relation with Their Performance. Public Adm. 2023, 101, 804–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, O.; Van der Vegt, G.S. Positivity Bias in Employees’ Self-Ratings of Performance Relative to Supervisor Ratings: The Roles of Performance Type, Performance-Approach Goal Orientation, and Perceived Influence. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2011, 20, 524–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, N.C.; Berry, C.M.; Houston, L. A Meta-Analytic Comparison of Self-Reported and Other-Reported Organizational Citizenship Behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, 547–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-Reports in Organizational Research: Problems and Prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidder, D.L.; Parks, J.M. The Good Soldier: Who Is s (He)? J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2001, 22, 939–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Paine, J.B.; Bachrach, D.G. Organizational Citizenship Behaviors: A Critical Review of the Theoretical and Empirical Literature and Suggestions for Future Research. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 513–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The Moderator–Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preacher, K.J.; Zyphur, M.J.; Zhang, Z. A General Multilevel SEM Framework for Assessing Multilevel Mediation. Psychol. Methods 2010, 15, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lianidou, T. The Role of Status and Power Inequalities in Leader-Member Exchange. Leadership 2021, 17, 654–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawitri, H.S.R.; Suyono, J.; Sunaryo, S. Interpersonal Justice, Leader-Member Exchange, and Employee Negative Behaviors: A Proposed Model and Empirical Test. Int. J. Bus. 2023, 28, 73–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainey, H.G. Understanding and Managing Public Organizations; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Morgeson, F.P.; Humphrey, S.E. The Work Design Questionnaire (WDQ): Developing and Validating a Comprehensive Measure for Assessing Job Design and the Nature of Work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumberg, M.; Pringle, C.D. The Missing Opportunity in Organizational Research: Some Implications for a Theory of Work Performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1982, 7, 560–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenabeele, W.; Scheepers, S.; Hondeghem, A. Public Service Motivation in an International Comparative Perspective: The UK and Germany. Public Policy Adm. 2006, 21, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritz, A.; Brewer, G.A.; Neumann, O. Public Service Motivation: A Systematic Literature Review and Outlook. Public Adm. Rev. 2016, 76, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hondeghem, A.; Vandermeulen, F. Competency Management in the Flemish and Dutch Civil Service. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2000, 13, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pynes, J.E. The Implementation of Workforce and Succession Planning in the Public Sector. Public Pers. Manag. 2004, 33, 389–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezapour, F.; Sattari Ardabili, F. Leader-Member Exchange and Its Relationship with Career Adaptability and Job Satisfaction Among Employees in Public Sector. Int. J. Organ. Leadersh. 2017, 6, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Guan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; She, Z.; Buchtel, E.E.; Mak, M.C.K.; Hu, H. A Relational Model of Career Adaptability and Career Prospects: The Roles of Leader–Member Exchange and Agreeableness. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2020, 93, 405–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tummers, L.G.; Knies, E. Leadership and Meaningful Work in the Public Sector. Public Adm. Rev. 2013, 73, 859–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosembloom, D.H. Public Administrative Theory and the Separation of Powers. Public Adm. Rev. 1983, 43, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, E.A.; Tyler, T.R. The Social Psychology of Procedural Justice; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 1988. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).