Abstract

Background: Systems thinking (ST) is an approach to problem-solving that views systems through a holistic perspective, focusing on the interconnections and relationships between various elements. In healthcare, the World Health Organization’s 2009 report marked a paradigm shift toward ST, prompting the development and use of ST tools to address complex challenges. Despite this, limited attention has been given to ST’s application in healthcare human resource management (HRM). This paper aims to provide a scoping review of ST application in healthcare HRM to explore its value in workforce management. Methods: Following Arksey and O’Malley’s framework, a scoping review was conducted to map how ST has been applied in healthcare HRM. Peer-reviewed articles published between 1999 and December 2024 were identified through Scopus and PubMed, using search terms such as systems thinking, human resources, and workforce. Data were extracted using a structured tool, and findings were analyzed through the lens of the system level of application. Results: The review identified 19 studies from 15 countries, with the majority using qualitative or mixed methods approaches across diverse settings. Core applications were applied at the macro, meso, and micro system levels to address workforce challenges, map feedback loops, identify leverage points, and strengthen stakeholder collaboration. ST was commonly applied at regional and national levels and supported improved workforce planning, policy development, and service coordination. Most studies employed soft systems modeling. Conclusions: This review highlights ST’s potential to enhance HRM by recognizing interdependencies across workforce functions. Findings suggest that ST enables more integrated strategies, promotes collaboration, and supports systemic decision-making. The adoption of ST in healthcare HRM may address persistent workforce challenges, though implementation remains limited by reductionist perspectives and unfamiliarity with ST tools.

1. Background

Systems thinking is an approach to problem-solving that views systems through a holistic perspective, focusing on the interconnections and relationships between various elements [1,2]. While definitions of ST vary [1,3], many descriptions highlight the importance of considering the system as a whole and recognizing that the interactions among its components shape its overall behavior [1,4].

ST originated in the early 20th century, driven by a growing awareness of the limitations of the traditional reductionist approach in addressing complex challenges [5]. The adoption of ST in healthcare gained momentum in the 21st century, particularly after the World Health Organization’s (WHO) 2009 report [2] framed it as a paradigm shift from traditional, reductionist approaches to a more holistic, dynamic perspective that acknowledges the complexity and interconnectedness of health systems [2]. This shift sparked a surge in the development and application of ST tools and methodologies to tackle persistent healthcare challenges.

A systematic review of the literature published between 2002 and 2015 identified 516 articles on ST in health, reflecting growing interest in the field [3]. Another review analyzed 36 global case studies from 2002 to 2013, showcasing practical applications of ST concepts and tools [6]. These cases, among others, featured initiatives aimed at strengthening local health systems and addressing complex challenges such as childhood obesity, neonatal mortality, and the effectiveness of tobacco control efforts [6].

This substantial body of evidence on ST illustrates a recognition that linear problem-solving approaches are insufficient for managing the complexities of health systems [1,2,6,7]. The acknowledgement highlights the potential of ST to navigate intricate challenges and improve health outcomes for individuals and populations [8].

Despite the increasing prominence of ST, scholars note the persistent challenge of achieving consensus on its concepts and attributes, which may reflect the field’s continuous evolution and diverse disciplinary origins [1,7,9,10].

Before examining the properties of complex systems, it is useful to first clarify what is meant by a “system” within a systems thinking approach. According to the literature, a system consists of a network of relationships among distinct elements that together form a coherent, sustainable pattern or whole [4]. This pattern enables the system to maintain itself over time, adapting as necessary to changes in its environment [4]. When defining a system through the lens of ST, several key concepts emerge: elements, interconnections, holism, purpose, and boundaries.

Arnold et al. [9] noted that these elements or components must be identified to understand a system’s structure and purpose [9]. Johnson et al. [11] further explained that the components of a system must be defined according to the specific problem or objective [11]. For example, in the WHO 2009 report [2], a health system is viewed as comprising organizations, people, and actions that aim to promote, restore, or maintain health [2]. The report outlined six building blocks that interact within health systems: service delivery, health workforce, health information, medical technologies, health financing, and leadership and governance [2]. Thelen et al. [1] described health systems as complex adaptive systems (CAS) made up of operational interconnected elements like healthcare providers, patients, policymakers, and broader societal structures [1].

Another feature of systems is the interaction between their components, forming networks of relationships [4]. These interconnections are central to ST, as they explain the system’s behavior, with feedback loops and complex interactions shaping its evolution [1,11].

Holism underscores the idea that systems cannot be fully understood by isolating their parts and must be viewed as a cohesive whole, with the environment as an essential component [4,12]. For example, a forest demonstrates the holistic nature of systems. It is more than just a collection of trees. It is an ecosystem where the interactions between trees, climate, soil, animals, and plants shape its overall characteristics. This holistic view extends to health systems. Peters [13] emphasized the need to perceive health systems as cohesive entities, where the combined functioning of policies, agents, and structures results in emergent behaviors, such as the adaptability of health systems to pressures [13]. These emergent properties are the result of interactions between system elements [13].

Each system exists to fulfill a particular function or goal, which guides the interactions among its components [11,13]. Thus, purpose is the driving force that organizes the elements and interconnections of a system, giving it direction and coherence [2,11]. In the case of health systems, the purpose could be improving population health, delivering equitable care, or efficiently managing healthcare resources.

ST also requires establishing boundaries to determine what is included within the system and what lies outside it. Peters [13] and Johnson et al. [11] pointed out that systems are defined by the scope of the problem being addressed [11,13]. For example, a system in the health sector can be identified at the national level, but depending on the context, a specific hospital or department can also be defined and function as a system, demonstrating all the necessary system characteristics such as elements, interconnections, holism, purpose, and boundaries.

Research on ST highlights the following key dimensions in applying it to healthcare: (1) understanding system structure and recognizing interconnections; (2) identifying and interpreting system feedback; (3) identifying leverage points; (4) understanding the system’s dynamic behavior; (5) using models to propose solutions; and (6) creating simulation models [1,2,9,13,14]. These six elements, outlined by Thelen et al. [1] as part of the Systems Thinking for Health Actions framework, aim to close the gap between theoretical and practical applications of ST in healthcare [1].

Building on these dimensions, applying ST to human resource management (HRM) in healthcare offers a way to address the complex, interconnected factors influencing workforce effectiveness and sustainability [15]. HRM encompasses the strategies and activities that support the recruitment, selection, training, performance assessment, and retention of the workforce, while ensuring leadership, workplace culture, and compliance with labour standards are maintained [16]. The health workforce includes everyone engaged in activities primarily intended to improve health [17], spanning frontline clinicians delivering direct patient care, those providing essential support, and those responsible for managing staff and shaping how health systems function [17,18].

Traditional HRM approaches tend to address problems in isolation, without accounting for their systemic effects, often resulting in ineffective policies and unintended consequences [19,20,21,22]. In contrast, ST emphasizes interconnectedness—across clinical staff, training, administrative processes, and patient care pathways—which enables HRM to design strategies that reflect these relationships and promote collaborative efforts [6,10,23].

Applying a ST lens to HRM also means understanding that workforce planning, recruitment, training, retention, and performance are not isolated functions. Rather, they are interdependent components of a larger system, where decisions in one area inevitably affect others [13].

While ST has been applied in other areas of healthcare, it remains underexplored in HRM despite ongoing workforce challenges [23,24]. Evidence on how ST has been used in practice to address human resource challenges across different levels of healthcare is scarce, particularly in relation to issues such as staff shortages, workforce migration, and capacity pressures [24].

The purpose of this paper is to conduct a scoping review of the practical application of ST in healthcare HRM, addressing the current gap in its use within this field. This review examines existing examples and synthesizes how ST can improve workforce management across various healthcare settings. By systematically mapping the available evidence, it seeks to bridge the divide between conceptual discussions and practical applications, and to highlight how ST can inform more integrated and effective HRM strategies, offering insights for policymakers, healthcare leaders, and researchers.

2. Methods

The research team used Arksey and O’Malley’s [25] framework to complete a scoping review of the literature on the practical application of ST to HRM in healthcare. The study’s purpose was to systematically explore the body of evidence on the subject, map the nature of ST application and the settings where it was applied, and identify gaps in the evidence.

The main research question was as follows: (1) What is the scope and use of ST application in healthcare HRM practice? To ensure the usability of the review findings, two additional questions were included: (1) In what specific areas of workforce management has ST been applied? (2) What challenges related to ST application were highlighted?

The researchers searched for peer-reviewed literature on the topic published from 1999 to December 2024. The search was conducted on Scopus and PubMed. The search terms and databases were finalized in consultation with a librarian, and the terms included words such as systems thinking, systems dynamics, human resources, healthcare workforce, and management practice (see Table 1). The searches were conducted using the following strings: (“systems thinking” OR “system dynamic*” OR “systems dynamic*” OR “dynamic analysis” OR “agent-based model*” OR “feedback loop*” OR “causal loop diagram*”) AND (“management practic*” OR “human resourc*”)

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

(“systems thinking” OR “system dynamic*” OR “systems dynamic*” OR “dynamic analysis” OR “agent-based model*” OR “feedback loop*” OR “causal loop diagram*”) AND (“workforce*”OR “healthcare workforce*”). Backward reference searching was also performed to identify additional relevant publications. The most recent search was carried out on 6 July 2025, and the review process adhered to the PRISMA reporting guidelines, as detailed in the accompanying PRISMA checklist (see Table S1 in Supplementary Material).

This review focused on the healthcare workforce population of nurses, physicians and allied health professionals, as well as interventions that included health human resources management. Forecasting models that focused on predicting the future demand and supply of health manpower to improve long-term HR planning were considered outside the scope of this review, as the aim was to document existing practices rather than model future scenarios. In addition, forecasting models typically rely on quantitative projections rather than system-level interactions, which differ from the conceptual emphasis of this review.

Articles that described specific disease management, drugs and medicine supply chains, database management, and health information technologies and infrastructure were excluded. This was done to maintain the review’s specific focus on the application of systems thinking to HRM in healthcare, as including these topics would expand the scope beyond workforce-related systems and dilute the emphasis on HRM practices. Table 1 provides an outline of the inclusion and exclusion criteria used in the scoping review.

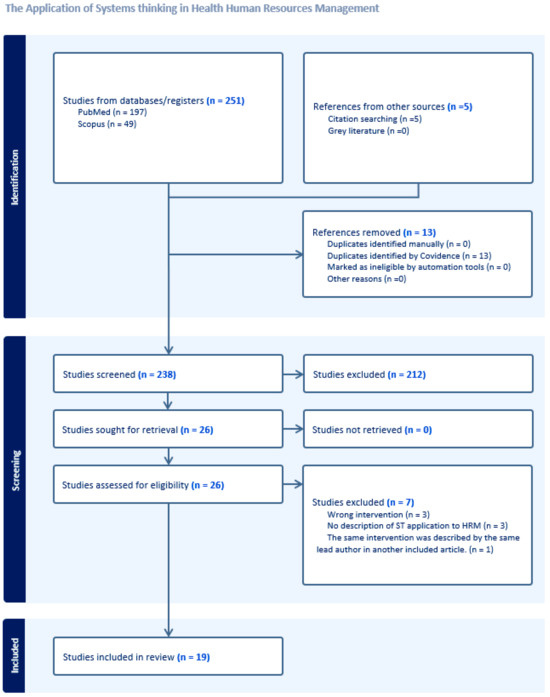

In total, 251 references were imported into Covidence [26], and 13 duplicates were removed. Five studies were identified through a citation search. A total of 238 studies with abstracts were screened by VB and EN; 26 were selected for full-text review, and 19 met the inclusion criteria and were included in this paper. Throughout the screening process, the researchers (VB and EN) met regularly to review and refine the inclusion and exclusion criteria and to resolve any disagreements.

The results from the search and selection of papers are provided in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

The extraction tool was created, which included the author, year, country, level of ST application, study aim(s), type of healthcare settings, study design, context, ST application, and description of main findings (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of included papers on ST in healthcare HRM.

Once data were extracted from five papers, the research team met to review and refine the tool. After extracting the data, we determined the level at which systems thinking was applied in healthcare HRM—macro, meso and micro. The macro level covered international, national, provincial, district, or regional systems and governments; the meso level focused on healthcare organizations and practice settings; and the micro level included teams, specific departments and units, or individual healthcare workers.

3. Findings

The review included publications from the following countries: Australia (2), Belgium (1), China (1), Georgia (1), Germany (1), Ghana (1), India (1), Iran (2), Jordan (1), Singapore (1), South Africa (1), Tanzania (1), Thailand (1), Uganda (2), and the UK (2). Notably, no papers were found on the topic from North or South America.

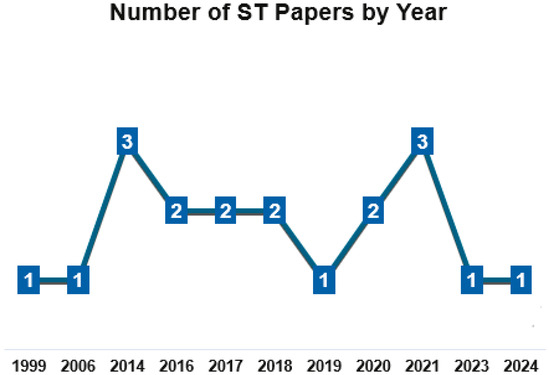

Figure 2 illustrates the timeline of published papers, showing a steady interest in applying ST to HHR. However, it also indicates that, despite this interest, the number of published studies on the topic remains limited.

Figure 2.

Timeline of published ST papers.

In terms of methodology, there were qualitative studies (n = 13, 69%), mixed-methods studies (n = 5, 26%), and a review (n = 1, 5%). Four studies (21%) were conducted as part of evaluations—realist evaluations (India, Iran), process evaluation (Tanzania), and impact evaluation (China). The main findings for each study are presented in Table 2.

The majority of studies applied soft systems modeling (n = 13, 68%), while only six (32%) used hard systems modeling, specifically system dynamics (SD). Soft systems modeling employs conceptual tools to analyze and map a system from multiple perspectives, with examples including causal loop diagrams, stakeholder mapping, sociograms, logic models, focus groups, and stakeholder interviews [4]. Hard systems modeling involves quantitative simulation models built from mathematical equations that represent system relationships, typically implemented with system dynamics software such as Vensim or Powersim [4].

The most common level of application was regional (n = 8, 42%), followed by national (n = 5, 26%), facility level (n = 3, 16%), unit level (n = 2, 11%). One study focused on international humanitarian level (5%).

Healthcare settings where ST was applied varied and included emergency care (n = 4), maternal and child health (n = 3), public health (n = 1), palliative care (n = 1), refugee care (n = 1), hospital specialty unit (eye clinic) (n = 1), family medicine (n = 1), rural community paramedicine (n = 1), and healthcare services non-specified (e.g., provided in clinics, hospitals, etc.) (n = 6).

Across the studies reviewed, systems thinking has been applied at macro (n = 14), meso (n = 3), and micro (n = 2) levels to address urgent and complex challenges in health human resources management.

At the macro level, studies focused on national or regional health systems, using ST to map unintended consequences of workforce policies, simulate policy scenarios, and reveal feedback loops that undermine reforms. For instance, in Ghana, systems thinking was used to show how increasing doctors’ pay through the Additional Duty Hours Allowance policy triggered strikes, wage pressures, and loss of trust, highlighting the need for prospective system mapping before implementing workforce policies [27]. In Thailand, researchers combined group model building and system dynamics to understand the persistent imbalance between workforce supply and demand, testing policy options that could adapt the workforce to an ageing population [32]. Similarly, Keyvani et al. [31] used a system dynamics model to unpack the interconnected economic and demographic drivers of health worker emigration in Iran, providing evidence for retention-focused policy interventions. Other macro-level studies mapped performance-based financing and gatekeeping policies, revealing how complex feedback loops could undermine intended goals if the health workforce context was not carefully integrated into design [40,43]. The application of causal loop diagrams and dynamic modeling at this level showed how deeply embedded workforce challenges are within larger health system structures [21,30].

At the meso level, systems thinking was used to improve understanding of workforce dynamics within specific healthcare organizations and services. For example, Alizadeh-Zoeram et al. [28] used system dynamics to demonstrate how well-meaning quality improvements in a hospital clinic led to workload spirals and errors if staffing adjustments lagged behind service demand. In the UK, Manley et al. [23] applied a whole-systems lens to urgent and emergency care, defining workforce enablers like clinical leadership and integrated career pathways to reduce duplication and ease system strain. Paina et al. [35] mapped how dual practice by health professionals evolved in urban Uganda, showing how feedback loops made local HR management policies fragile in practice. These meso-level studies showed that addressing human resources issues within facilities demands seeing connections between staff capacity, service quality, and organizational learning.

At the micro level, systems thinking was utilized to understand team interactions and departmental constraints that shape daily workforce realities. For example, Pype et al. [38] showed how palliative care teams in Belgium function as complex adaptive systems, with workplace learning emerging from constant interaction and adaptation among team members. In Singapore, Schoenenberger et al. [42] mapped the systemic factors driving emergency department crowding, finding that expanding ED staff or geriatric emergency services alone could worsen crowding unless primary care access improved. These micro-level applications reveal how local team dynamics and unit-level constraints can amplify or hinder wider workforce reforms.

4. Discussion

These findings address the main research question by illustrating the scope and practical applications of ST in healthcare HRM across healthcare system levels. The review shows that ST has been implemented across various levels, with macro-level applications being the most prevalent (74%), followed by meso-level (16%), and micro-level (10%). This distribution highlights ST’s flexibility in addressing workforce challenges at different scales.

The range of healthcare settings where ST was applied demonstrates its adaptability. Applications were identified in emergency care, maternal and child health, public health, palliative care, refugee care, specialty hospital units, family medicine, and rural community paramedicine. Additionally, several studies applied ST in broader clinical and hospital settings without specifying a particular healthcare service. In terms of healthcare types, most of the settings were public, with only one private institution identified (see Table 2). This may reflect the complexity of applying ST approaches in private settings, where organizational priorities and funding structures can limit opportunities for broad, system-level initiatives.

In the practical application of ST, at the macro level, the key themes revolve around policy resistance, unintended consequences, health workforce supply–demand mismatches, and the complex effects of financing and migration. Studies such as Agyepong et al. [27] and Lebcir [21] revealed how new policies (like salary adjustments or healthcare reforms) can generate knock-on effects that ripple across the system. Others, like Leerapan et al. [32] and Keyvani et al. [31], demonstrated how system dynamics models help test national retention strategies and migration policies before implementation. The theme of stakeholder involvement and prospective scenario planning [30,43] also stands out.

At the meso level, common themes include workforce capacity erosion, workload spirals, dual practice management, and integrated workforce planning within organizations. Studies like Alizadeh-Zoeram et al. [28] and Manley et al. [23] showed how local policies and operational practices can either stabilize or destabilize service quality, depending on whether they account for feedback between staffing, learning curves, and quality demands. Paina et al. [35] highlighted how local contexts and informal practices shape real workforce outcomes.

Micro level studies highlighted the importance of team interactions, workplace learning, and unit-level challenges [38,42]. These studies show how front-line teams behave as complex adaptive systems where collaboration, mentoring, and information sharing directly influence staff effectiveness and retention.

4.1. Mapping Relationships and Feedback Loops

A unifying theme common across levels is that ST makes visible the hidden feedback loops that often explain why well-intentioned workforce interventions underperform or backfire. Whether it is national pay incentives, facility staffing plans, or team-level learning, these interventions interact with the broader system in ways that linear planning cannot capture. At all levels, stakeholder engagement and visual tools like CLDs help identify connections and coordinate actions more effectively. Overall, this review identified 13 studies (68%) that used CLDs in areas such as policy adjustment and resource allocation, unintended consequences of workforce policies, and the impact of funding and systemic drivers (see Table 2).

Across studies, CLDs have been used to illustrate how policy and funding decisions shape workforce stability and system performance. Analyses of salary reforms and healthcare restructuring, such as those in Ghana [27] and Georgia [21], demonstrated that policy shifts targeting one professional group often generate ripple effects across others, showing that workforce satisfaction and resource distribution are interdependent. Similarly, system mapping in Iran [28] and Uganda [40] revealed how workforce policies can create reinforcing feedback loops, where factors like workload, performance-based financing, or service demand either amplify strain or perpetuate advantage among better-resourced facilities.

CLD applications in diverse contexts, including Jordan’s refugee healthcare and China’s gatekeeping reforms, underscored that limited funding and institutional hierarchies can weaken system resilience. These studies collectively demonstrated that workforce and resource policies cannot be examined in isolation, as they interact through feedback mechanisms that shape quality, equity, and sustainability across the entire health system.

4.2. Identifying Leverage Points for HR Interventions

The application of ST enables HR managers to identify leverage points that drive improvements in workforce management and care delivery. Eight papers (42%) described how leverage points were identified, and which ones were targeted for potential HR interventions in emergency care, community health and healthcare access, and in leadership and workforce development.

4.3. Emergency Care

In the UK, SD modeling in emergency care shifted the focus from increasing capacity (e.g., beds, staff) to addressing referral patterns, thus identifying critical leverage points for improvement [41]. Research in Germany on emergency medical services pinpointed triage as a high-impact intervention, which increased dispatcher satisfaction and job retention [39]. Meanwhile, a paper from Singapore identified enhanced primary care as a key leverage point for reducing ED crowding that, unlike other interventions which produced unintended consequences, was found to strengthen primary care and improve patient flow without negative side effects [42].

4.4. Community Health and Healthcare Access

A study from Jordan identified community health volunteer programs as potential leverage points for improving healthcare access for refugees [36]. Research in Tanzania identified several catalytic variables (leverage points) in P4P programs, such as drug supply availability, staffing levels, and supervision quality, which were deemed critical for strengthening service delivery [30].

4.5. Leadership and Workforce Development

Additionally, research from Australia used ST to demonstrate how investing in leadership training and the professional development of staff involved in programs addressing obesity proved to be a powerful leverage point [29]. Similarly, a paper from South Africa identified leadership as a leverage point for improving staff motivation, patient attendance, and overall system performance [33]. In Uganda, research highlighted supervision tasks as a key leverage point within the PBF intervention [40]. The study recommended refining supervision responsibilities to prevent overburdening supervisors with verification tasks, thus improving program effectiveness [40].

As shown by these examples, identifying targeted, systemic changes at leverage points can lead to substantial improvements in workforce management.

The reviewed case studies collectively underscore the value of adopting a holistic perspective in healthcare HRM. Findings suggest that interventions in healthcare HRM should extend beyond isolated programs, adopting a broader approach that accounts for hidden interdependencies across roles, settings, and functions within the system [23,35,39,41].

Additionally, the studies demonstrated the advantages ST offers policymakers and practitioners, including heightened awareness of potential unintended consequences, identification of leverage points, facilitation of complementary partnerships, and a more comprehensive understanding of system dynamics that support strategic, informed decision-making [23,27,38,39,41].

The sources also emphasized the importance of leadership in the successful application of ST in healthcare HRM [23,29,34,37,38]. Effective leadership in this context is characterized by a commitment to change, the ability to cultivate relationships among diverse stakeholders, and the promotion of adaptability and innovation across the system [42].

However, the research revealed notable barriers to implementing ST in healthcare HRM. A prevalent reductionist mindset was found to hinder ST adoption [22,29]. Additionally, healthcare professionals often lack familiarity with ST tools, as their training typically focuses on individual diseases and treatments rather than a holistic view of health systems [22,38]. Organizational resistance, rooted in established hierarchies and professional silos, further complicates efforts to shift toward collaborative, system-oriented decision-making [22,37,38].

The studies also indicated that evaluating the impact of ST applications is challenging, as conventional evaluation methods often fail to capture the nuanced, long-term outcomes ST aims to achieve [1,37]. A common tendency toward retrospective, rather than prospective analysis was identified as a limitation in assessing ST’s potential impact [1,27].

Finally, resource constraints, including budget and time limitations, were reported to restrict the capacity to invest in activities necessary for effective ST implementation, especially in low and middle-income countries [21,22,27,29,33,36,37]. Fewer studies are conducted in these settings. High-income countries, with greater research capacity, dominate the evidence base. However, findings from these contexts may not be fully applicable or transferable to resource-constrained environments.

The limitations of this scoping review include the restriction to English-language titles, abstracts, and full-text articles, which may have excluded relevant studies published in other languages. The review also included only peer-reviewed literature, potentially omitting insights from grey literature or non-peer-reviewed sources. The variability in the definitions and descriptions of ST methodology across different sources may have resulted in some relevant articles being overlooked. In addition, the scope of HR applications related to ST may not have been fully captured in the review due to the diverse ways in which these concepts are presented in the literature.

Another limitation of the scoping review is that most included studies relied on soft systems modeling, creating a possibility that important quantitative feedback loops were overlooked and that qualitative approaches may not fully capture dynamic workplace interdependencies.

The scoping review did not examine the specific gaps underlying the limited integration of systems thinking in HRM, as such analysis was beyond its scope. However, this is an important direction for future research, which could examine factors such as cultural barriers, lack of training, and organizational resistance that may hinder broader implementation.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review examined how ST has been applied to HRM in healthcare and the extent to which such applications inform workforce policy and practice. The review found that although interest in ST has grown across diverse contexts, its integration into HRM remains limited and uneven across system levels. Most studies engaged with ST conceptually, highlighting interdependencies among workforce variables, but relatively few demonstrated the use of ST tools or frameworks to guide decision-making and implementation.

The application of ST in human resources management highlights its potential to move beyond traditional, fragmented approaches. By integrating workforce planning with broader systemic considerations, HR managers can more effectively address challenges and improve overall healthcare delivery. Reviewed studies illustrated how adopting a systems lens led to more sustainable solutions and enhanced collaboration among stakeholders, ultimately driving progress toward improved health outcomes.

Across all levels, the review identified recurring barriers to integration, including organizational resistance to non-linear approaches, limited ST capacity among managers, and insufficient institutional support for participatory learning and modeling. These barriers reinforce reductionist approaches to workforce planning that focus on immediate staffing targets rather than longer-term system resilience.

Overall, this review underscores the value of systems thinking as both an analytical lens and a practical approach for transforming healthcare workforce management. By identifying leverage points, mapping feedback loops, and fostering adaptive learning, ST can help bridge the persistent divide between short-term workforce targets and the broader goals of sustainable, equitable, and resilient health systems.

To strengthen ST integration in healthcare HRM, future work should prioritize four interrelated strategies:

- Building ST literacy through professional development and leadership training that emphasizes systems awareness and reflexive learning.

- Embedding participatory modeling within HR planning to align mental models across stakeholders and promote shared decision-making.

- Embedding ST in workforce evaluation frameworks to enable ongoing monitoring of interdependencies among policies, staffing, and service delivery outcomes.

- Supporting longitudinal research that examines how systems-oriented HRM approaches influence retention, motivation, and service quality over time.

Future research could focus on reviewing ST applications in specific healthcare settings, such as emergency care, to analyze whether there are similarities or differences in the HR solutions identified.

The predominance of public healthcare settings implementing ST identified by the scoping review may be due to various factors, such as greater alignment within broader health systems or limited interest and funding in the private sector. However, this pattern warrants further investigation to determine the influence of organizational structures and institutional contexts.

Overcoming resistance to change requires more than new policies—it depends on fostering an organizational culture that recognizes and values complexity. As the healthcare landscape continues to evolve, cultivating such a culture through systems thinking offers a pathway to more effective and responsive health systems that can adapt to emerging needs and challenges.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/systems13111001/s1, Table S1, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist, completed in accordance with the established guidelines [44].

Author Contributions

V.B.: Co-developed the study concept and research question with E.N., screened abstracts and full-text articles, drafted the initial manuscript, prepared tables and contributed to revisions and final approval. E.N.: Co-developed the study concept and research question with V.B., advised on the data extraction tool, screened abstracts and full-text articles, and contributed to final manuscript revisions. V.B. and E.N. met regularly during the screening process to review and refine the inclusion and exclusion criteria and resolve any disagreements. P.B. and J.Y.: Provided critical review and editorial input during the final stages and approved the completed manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests as defined by BMC, nor any other interests that could be perceived to influence the results or discussion presented in this paper.

References

- Thelen, J.; Fruchtman, C.S.; Bilal, M.; Gabaake, K.; Iqbal, S.; Keakabetse, T.; Kwamie, A.; Mokalake, E.; Mupara, L.M.; Seitio-Kgokgwe, O.; et al. Development of the Systems Thinking for Health Actions framework: A literature review and a case study. BMJ Glob. Health 2023, 8, e010191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Savigny, D.; Adam, T. (Eds.) Systems thinking for health systems strengthening. In Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rusoja, E.; Haynie, D.; Sievers, J.; Mustafee, N.; Nelson, F.; Reynolds, M.; Sarriot, E.; Swanson, R.C.; Williams, B. Thinking about complexity in health: A systematic review of the key systems thinking and complexity ideas in health. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2018, 24, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trochim, W.M.; Cabrera, D.A.; Milstein, B.; Gallagher, R.S.; Leischow, S.J. Practical challenges of systems thinking and modeling in public health. Am. J. Public Health 2006, 96, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. Complex Adaptive Systems: An Introduction to Computational Models of Social Life; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, J.; Goff, M.; Rusoja, E.; Hanson, C.; Swanson, R.C. The application of systems thinking concepts, methods, and tools to global health practices: An analysis of case studies. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2018, 24, 607–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M.C.; Sambo, L.G. Health systems research and critical systems thinking: The case for partnership. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2020, 37, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalla, A.D.G.; Bahr, R.R.R.; El-Sayed, A.A.I. Exploring the hidden synergy between system thinking and patient safety competencies among critical care nurses: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, R.D.; Wade, J.P. A definition of systems thinking: A systems approach. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 44, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, H.; Lakhani, A. Using systems thinking methodologies to address health care complexities and evidence implementation. JBI Evid. Implement. 2021, 20, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.A.; Anderson, D.E.; Rossow, C.C. Health Systems Thinking; Jones and Bartlett: Sudbury, MA, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, D. Exploring the Social Implications of General Systems Theory. In The Science of Synthesis; University Press of Colorado: Denver, CO, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, D.H. The application of systems thinking in health: Why use systems thinking? Health Res. Policy Syst. 2014, 12, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraldsson, H. Introduction to system thinking and causal loop diagrams. In Department of Chemical Engineering; Lund University: Lund, Sweden, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nuis, J.W.; Peters, P.; Blomme, R.; Kievit, H. Sustainable HRM: Examining and Positioning Intended and Continuous Dialogue in Sustainable HRM Using a Complexity Thinking Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde, M.; Ryan, G. Distributing HRM responsibilities: A classification of organizations. Pers. Rev. 2006, 35, 618–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Health Report 2006: Working Together for Health Who.int. World Health Organization. 2006. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9241563176 (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Bourgeault, I.L.; Chamberland-Rowe, C.; Simkin, S.; Slade, S. A Proposed Vision to Enhance CIHI’s Contribution to More Data Driven and Evidence-Informed Health Workforce Planning in Canada; University of Calgary: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zukowski, N.; Davidson, S.; Yates, M.J. Systems approaches to population health in Canada: How have they been applied, and what are the insights and future implications for practice? Can. J. Public Health 2019, 110, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowda, N.R.; Wankar, A.; Arya, S.K. Feedback system in healthcare: The why, what and how. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebcir, M. Health Care Management: The Contribution of Systems Thinking; University of Hertfordshire: Hatfield, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, R.C.; Cattaneo, A.; Bradley, E. Rethinking health systems strengthening: Key systems thinking tools and strategies for transformational change. Health Policy Plan. 2012, 27, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manley, K.; Martin, A.; Jackson, C.; Wright, T. Using systems thinking to identify workforce enablers for a whole systems approach to urgent and emergency care delivery: A multiple case study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, C.; Prowse, J.; McVey, L.; Elshehaly, M.; Neagu, D.; Montague, J.; Alvarado, N.; Tissiman, C.; O’Connell, K.; Eyers, E.; et al. Strategic workforce planning in health and social care—An international perspective: A scoping review. Health Policy 2023, 132, 104827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covidence—Better Systematic Review Management Covidence. 2020. Available online: https://www.covidence.org/ (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Agyepong, I.A.; Aryeetey, G.C.; Nonvignon, J. Advancing the application of systems thinking in health: Provider payment and service supply behaviour and incentives in the Ghana National health insurance scheme—A systems approach. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2014, 12, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh-Zoeram, A.; Pooya, A.; Naji-Azimi, Z.; Vafaee-Najar, A. Simulation of quality death spirals based on human resources dynamics. Inquiry 2019, 56, 46958019837430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensberg, M.; Allender, S.; Sacks, G. Building a systems thinking prevention workforce. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2020, 31, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassidy, R.; Tomoaia-Cotisel, A.; Semwanga, A.R.; Binyaruka, P.; Chalabi, Z.; Blanchet, K.; Singh, N.S.; Maiba, J.; Borghi, J. Understanding the maternal and child health system response to payment for performance in Tanzania using a causal loop diagram approach. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 285, 114277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyvani, H.; Majdzadeh, R.; Khedmati Morasae, E.; Doshmangir, L. Analysis of Iranian health workforce emigration based on a system dynamics approach: A study protocol. Glob. Health Action 2024, 17, 2370095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leerapan, B.; Teekasap, P.; Urwannachotima, N.; Jaichuen, W.; Chiangchaisakulthai, K.; Udomaksorn, K.; Meeyai, A.; Noree, T.; Sawaengdee, K. dynamics modelling of health workforce planning to address future challenges of Thailand’s Universal Health Coverage. Hum. Resour. Health 2021, 19, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lembani, M.; de Pinho, H.; Delobelle, P.; Zarowsky, C.; Mathole, T.; Ager, A. Understanding key drivers of performance in the provision of maternal health services in eastern cape, South Africa: A systems analysis using group model building. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, A.C.; O’Meara, P. Community paramedicine through multiple stakeholder lenses using a modified soft systems methodology. Australas. J. Paramed. 2020, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paina, L.; Bennett, S.; Ssengooba, F. Advancing the application of systems thinking in health: Exploring dual practice and its management in Kampala, Uganda. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2014, 12, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, P.K.; Rawashdah, F.; Al-Ali, N.; Abu Al Rub, R.; Fawad, M.; Al Amire, K.; Al-Maaitah, R.; Ratnayake, R. Integrating community health volunteers into non-communicable disease management among Syrian refugees in Jordan: A causal loop analysis. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e045455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashanth, N.S.; Marchal, B.; Devadasan, N.; Kegels, G.; Criel, B. Advancing the application of systems thinking in health: A realist evaluation of a capacity building programme for district managers in Tumkur, India. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2014, 12, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pype, P.; Mertens, F.; Helewaut, F.; Krystallidou, D. Healthcare teams as complex adaptive systems: Understanding team behaviour through team members’ perception of interpersonal interaction. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehbock, C.; Krafft, T.; Sommer, A.; Beumer, C.; Beckers, S.K.; Thate, S.; Kaminski, J.; Ziemann, A. Systems thinking methods: A worked example of supporting emergency medical services decision-makers to prioritize and contextually analyse potential interventions and their implementation. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2023, 21, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renmans, D.; Holvoet, N.; Criel, B. Combining theory-driven evaluation and causal loop diagramming for opening the “black box” of an intervention in the health sector: A case of performance-based financing in Western Uganda. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royston, G.; Dost, A.; Townshend, J.; Turner, H. Using system dynamics to help develop and implement policies and programmes in health care in England. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 1999, 15, 293–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenenberger, L.K.; Bayer, S.; Ansah, J.P.; Matchar, D.B.; Mohanavalli, R.L.; Lam, S.S.; Ong, M.E. Emergency department crowding in Singapore: Insights from a systems thinking approach. SAGE Open Med. 2016, 4, 2050312116671953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Mills, A. Challenges for gatekeeping: A qualitative systems analysis of a pilot in rural China. Int. J. Equity Health 2017, 16, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, T.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMAScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).