Abstract

The success of marine environmental regulations in terms of social challenges in Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) countries is the main subject of this study, which compares and contrasts them with an eye toward sustainability, the integration of digital technologies, environmental law, and reducing ecological degradation. Environmental solid governance is essential as BRI countries increase their marine activity, an important part of the world economy by systems thinking; the marine industry includes a broad range of operations about the ocean and its resources through social challenges to promote environmental legislation in terms of emissions in the countries participating in the BRI. This study evaluated the effects of institutional quality and technical advancements in marine policies between 2013 and 2024. This project aims to examine how various policy contexts relate to marine conservation, how well they comply with international environmental regulations, and how digital technology can improve the monitoring and implementation of policies through systems thinking. This study aims to determine common obstacles and best methods for enforcing marine policies by examining research from different BRI countries. The results deepen our understanding of how these policies can be best utilized to meet sustainable development objectives while preventing the degradation of marine ecosystems due to economic growth and business.

1. Introduction

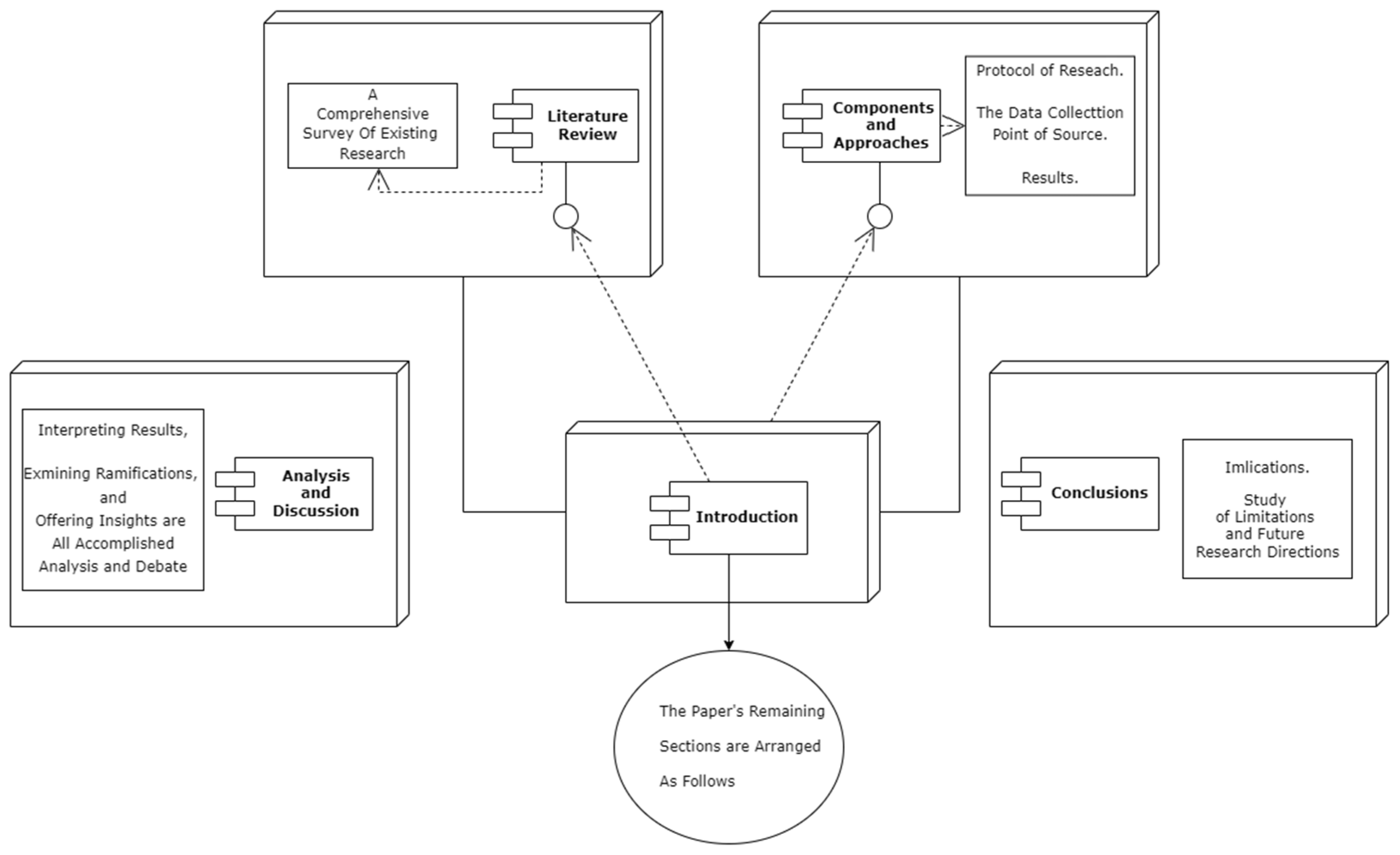

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), led by China, has become a major global development plan in recent years. Its goal is to improve economic integration and regional connectivity between Asia, Europe, and Africa [1]. The environmental effects of these operations have drawn a lot of attention amid the swift advancements in economics and infrastructure [2]. Coastal development, resource exploitation, and increased shipping significantly harm marine habitats. Therefore, effective marine environmental policies are essential to reducing negative consequences and advancing sustainability. We focus on comparing the efficacy of the marine ecological policies that BRI countries have put in place, emphasizing how well they can advance environmental legislation and sustainability with several methods and how they work to find best practices and possible areas for development and systems thinking. The results would be anticipated to enhance the comprehension of how global partnerships within the BRI plan may harmonize economic expansion with ecological responsibility, guaranteeing the preservation of aquatic environments for posterity [3]. While its driving role still needs strengthening, the BRI has also significantly increased participating countries’ eco–economic system coupling coordination level. These suggest that trade and investment behavior on a BRI basis positively contribute to environmental sustainability. According to various policies concerning the BRI, China has expanded its legislative responsibilities in the marine environment. Digital technology has recently contributed to a new momentum that propels sustainability and efficiency within the marine sector, making it an innovative industry [4]. Such technologies, including data analytics, satellite tracking of ships, and autonomous ships, leave a smaller environmental impact with the more efficient management of resources. The sustainable marine environment policy brings ecological protection and economic development into balance. Strict marine rules are, therefore, becoming increasingly important. More and more countries are in the process of joining programs like the Belt and Road Initiative to address the challenges of globalization and climate change, support the growth of the marine industry, and protect aquatic habitats for future generations. In this respect, formulating and implementing effective policies and regulations become of the essence, and these rules need to be updated (5). The establishment of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea came initially due to the damage caused to the marine environment by the rapid growth of the modern economy. Several other nations have also established such laws through their movements for marine development and conservation [5]. In 2013, China launched the BRI. This stimulated economic growth across Asia and elsewhere by facilitating infrastructure building and investment to boost economic growth throughout Asia and beyond. This large-scale initiative spans more than 140 countries and focuses on collaboration and connectivity in several industries, such as energy, digital infrastructure, and transportation. The BRI has placed a greater emphasis on sustainable development as environmental concerns have grown, especially in marine settings vital to biodiversity and millions of people’s livelihoods [6]. We aim to assess how well BRI countries’ marine environmental policies foster environmental sustainability. The examination intends to uncover best practices and highlight the issues that these countries face in combining economic growth with ecological preservation. Most countries struggle to achieve environmental sustainability and sustainable development, especially emerging and developing countries like Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Indonesia, and Malaysia, prioritizing accelerating their social challenges and economic progress. However, increased energy consumption brought about by rising economic growth has increased carbon emissions. Marine ecosystems are essential to financial stability and global biodiversity, and their health and sustainability must be preserved through implementing marine environmental regulations [7]. When taken as a whole, these studies highlight the multifaceted approach needed to support environmental sustainability in BRI countries. This paper’s remaining sections are arranged as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The sectional model derived from particular research studies.

We need to ensure that marine resources are appropriately managed and preserved for future generations. Marine regulations control activities, including fishing, shipping, and coastal development. Reasonable marine regulations are instrumental in ensuring that the BRI effectively balances environmental protection with national economic development. Various policy inclinations between the marine sectors and governance levels might further reduce, effectively, the effectiveness of MSP, even with developments in marine management [8]. The greening of finance within the Belt and Road Initiative has effectively reduced environmental degradation while fostering economic expansion. Examples are tax cuts for corporations and interest rate subsidies for green loans. In this regard, the present study aims to assess how marine environment legislations in BRI countries support ecological sustainability. Avenues of improvement and best practices can be identified in how other countries implement and enforce those laws, as illustrated [9]. Good marine environmental legislation promotes environmentally and economically benign sustainable development, protecting marine habitats while contributing to the attainment of the broader goals of the BRI. This research evaluates marine environmental legislation’s effectiveness in ecological sustainability within the nations in the BRI. Among the specific objectives are evaluating existing policies, identifying best practices, and analyzing challenges experienced in enforcing them. Therefore, the policies adopted, their quantifiable impact on sustainability, and the challenges in their cooperative enforcement are significant themes that this research covers [10]. With this information, this research recommends how marine governance under the BRI can be further improved to assist stakeholders in devising more environmentally friendly and sustainable practices. In the final analysis, the MEMAS model offers an all-encompassing approach to building a marine policy regime capable of meeting environmental sustainability challenges and enabling the Blue Economy’s growth, demonstrating the importance of constant monitoring and international cooperation [11].

2. Literature Review

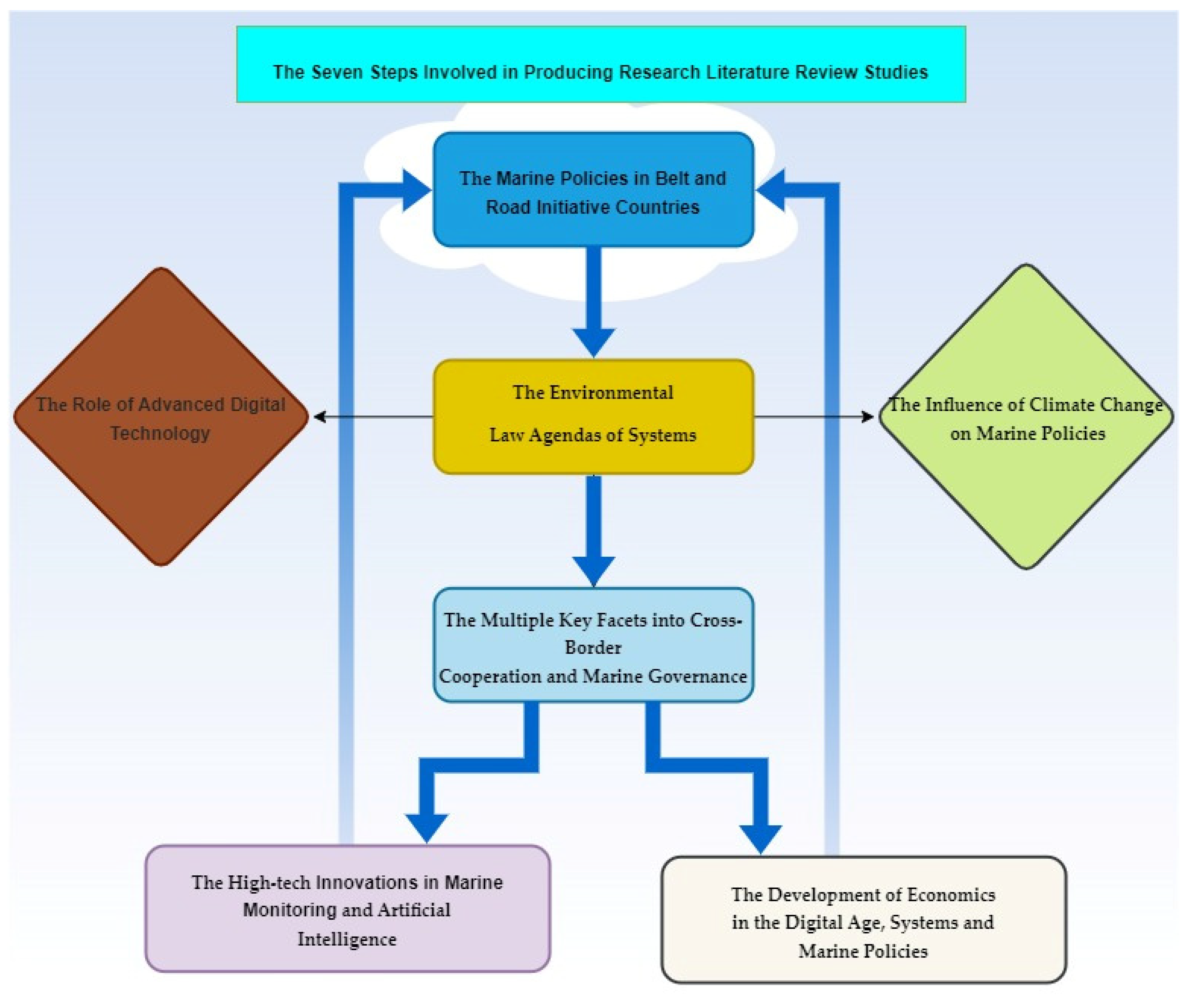

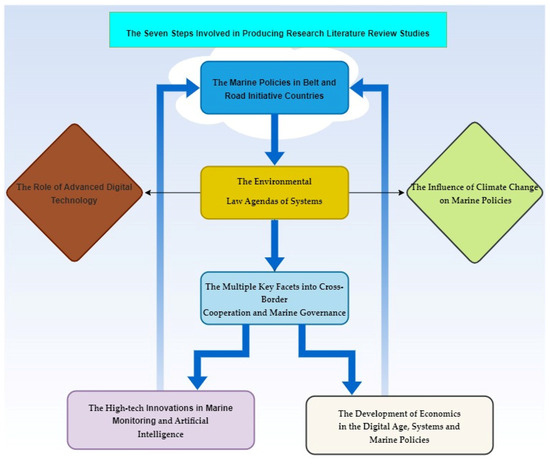

The Research Synthesis emphasizes the interaction between regulatory agendas and technological advancements in promoting environmental law and sustainability, especially in digital technology and comparative research among countries participating in the BRI [12]. It expresses how marine policy can better comply with environmental regulations, promoting sustainable behaviors. The evaluation also evaluates how digital technologies monitor and enforce these norms, exposing variations in how they are implemented among BRI countries. Ultimately, it emphasizes how customized strategies that consider regional circumstances are necessary to enhance the efficacy of policies and the results provided for the environment [13]. Research comprises seven crucial components, each with considerable intricacy, created extensively, as shown in Figure 2, that précises these components and an academically sound story that explains the information to facilitate comprehension.

Figure 2.

Upfront theoretical narrative.

2.1. The Marine Policies in Belt and Road Initiative Countries

China launched a major geopolitical and economic initiative, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which aims to improve global trade connectivity through infrastructure investments, including marine routes. Because this effort involves the creation of sizeable marine infrastructure and international cooperation, it has significant consequences for marine policies in BRI countries. The goal of the 21st Century Marine Silk Road, the marine portion of the BRI, is to increase trade and communication between Asia, Africa, and Europe. Over 60 countries signed preliminary agreements to cooperate with China, while over 100 countries endorsed the plan. While this can help catalyze economic growth in countries with underdeveloped infrastructure, many concerns about neo-colonialism and geopolitical instability continue to be raised. The BRI has brought opportunities but also societal challenges to Sri Lanka [14]. The program has enhanced economic development and overcome various infrastructural deficiencies, but it has also increased debt levels and raised several concerns about national sovereignty and transparency [15]. Studies indicate that the BRI bears financial and geopolitical risks and can decrease shortages through catch-up economic growth by emerging countries. Thus, countries participating in this program should work out a mechanism to enhance the openness of projects under the BRI, sustainability, and accountability. The participating governments in the marine policy are mainly concerned with the impacts of the Belt and Road Initiative on seaports. The COVID-19 pandemic and geopolitical unrest are limiting factors in efforts toward increasing the efficiency of port projects. China holds a tight grip on the marine port sector and is aggressively pursuing its ambitions to expand its presence in areas of interest [16]. The effort seeks to improve seaport project efficiency but is confronted with geopolitical conflicts and the COVID-19 pandemic. China has significantly influenced the marine port sector and is working to increase its footprint in key areas. However, the pandemic’s impact and strategic economic concerns have led to a recognized “cooling” of sentiments toward Chinese investments in Europe [17]. The literature advises promoting regional collaboration and attending to strategic economic interests to increase trust in Chinese investments [18]. BRI countries’ marine policies must also consider broader environmental and sustainability concerns. Effective marine governance is essential, as demonstrated by the continuing talks for a legally binding instrument to preserve and sustain marine biological diversity. The marine policy should mention environmental impact assessments, environmental management plans, marine genetic resources, and capacity building. Economic development and environmental sustainability are two driving imperatives that have been closely determining the marine policies in the countries participating in the Belt and Road Initiative. It thus requires the need to bridge the gap between science and policy so that the best possible research can be used to inform marine policies and achieve the ambitious objectives concerned with the complex challenges of marine biodiversity conservation. While the BRI presents some unique opportunities in economic development and the infrastructural landscape, it is equally imperative to be mindful regarding the prudent management of environmental, financial, and geopolitical risks [19].

2.2. Environmental Law Agendas of Systems

The agendas for environmental law demonstrate an increasingly complex and dynamic topic that interacts with public health, sustainability, governance, and indigenous rights, among other disciplines. According to a systematic review by Atta and Sharifi, stakeholder participation and clear systems thinking are essential for preventing institutional collapse and ensuring successful policy implementation [20]. The Rule of Law has a crucial role in supporting environmental sustainability. The present evaluation highlights deficiencies in investigating fundamental rights and justice systems, proposing avenues for future research to augment worldwide environmental goals. According to Sartor et al.’s analysis of the ISO 14001 standard, enterprises should integrate environmental management systems to enhance sustainability [21]. This norm has greatly influenced corporate environmental objectives, although more theory-based studies are needed to comprehend its broader effects fully. Significant obstacles, such as non-compliance and conceptual ambiguities, are shown by Kassie’s inquiry into the barriers to the effective adoption and enforcement of international environmental legislation. The disparities between Global North and South countries exacerbate these problems, underscoring the necessity for customized approaches to policy execution that consider economic dependence and regime types. Holstead et al. suggest researching the street-level bureaucrats’ involvement in environmental governance [22]. These players play a critical role in converting international agreements into regional initiatives that impact how the public perceives environmental laws. The study recommends concentrating on their agency and practices better to understand these bureaucrats’ influence on governance outcomes. The survey conducted by researchers Mustafa and Fauzia regarding the Malaysian Environmental Quality Act demonstrates how environmental law and public health are intertwined, especially in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. This study promotes integrated approaches to meet sustainable development goals by highlighting the significance of legal systems thinking in pollution management and health protection. Merger states that the conference on global environmental law addresses matters concerning international law and its relation to ecological governance. Interdependence between a range of institutional and legal levels creates opportunities for the collaborative engagement of global environmental problems. Research by Darian-Smith on American Indian and ecological legislation reveals that Native Americans have increasingly become involved in environmental politics [23]. This engagement refocuses American environmental goals by identifying Indigenous rights and perspectives as highly relevant when writing laws. Burger’s literary study of environmental law shows how environmental myths and stories influence legal arguments and judicial judgments, underlining the narrative dimensions of legal procedures. Further, a better understanding of these stories will provide greater insight into the goals and effects of environmental legislation. The comprehensive analysis that Ashford and Caldara carry out of environmental law, politics, and economics makes a convincing case for strict laws together with flexible means of enforcement [24]. They outline how the law can contribute to solving more general problems of sustainable development and stimulating technical change through the participation of numerous actors. It highlights the complexity of environmental law, especially the importance of a multidisciplinary approach. Integrating their strategies will be crucial to resolving issues that are continuously growing in complexity among such disciplines [25].

2.3. The Role of Advanced Digital Technology

Digital technologies are critical to optimizing resource use and improving sustainability practices within the circular economy context. Predictive analytics, data management, and virtual reality are essential technologies that enhance the transparency of the supply chain and product lifecycle. These developments show how digital technology may significantly improve environmental operations [26]. Digital technology plays a critical role in education by enhancing both the accessibility and quality of learning. It encourages the incorporation of ICT, e-learning, and AI applications to improve educational possibilities and prepare students for a future driven by technology. Digital tool integration promotes inclusion and adaptability in learning contexts, especially in isolated locations with inadequate infrastructure. Technology in the classroom also changes the way that education is delivered, boosts student engagement, and offers individualized learning opportunities [27]. Privacy concerns and the digital divide must be resolved to realize these advantages fully. Digital technology also greatly influences social relationships, changing connectedness and communication. Social networks are strengthened by technology, but worries about depersonalization and dependence on data are also raised. Artificial intelligence (AI) and big data analytics are digital tools that help with strategic decision-making and optimize financial management procedures [28]. Issues like the digital gap and privacy concerns must be resolved to maximize these advantages. Additionally, digital technology significantly impacts social interactions, which changes communication and connectivity. It improves social networks and connectedness but raises questions about data reliance and depersonalization [29]. Digital tools such as artificial intelligence (AI) and big data analytics simplify financial management processes and help make strategic decisions. Also, it presents new difficulties regarding data security and changing business models. Digital technologies in healthcare reduce material and human losses by increasing efficiency and accuracy [30]. However, carefully considering stakeholder reactions and governance is necessary for successful implementation. Innovation and digital technology have a complicated relationship that affects people directly and indirectly at different stages of economic development, and digital technology is a driver for change in many fields. It brings significant advantages but poses problems that must be strategically managed. Its contributions to advancing healthcare, education, social interactions, sustainability, and financial management are well established [31].

High-Tech Innovations in Marine Monitoring and Artificial Intelligence

The technological developments in marine monitoring present an active area with many applications and rapid advancements. Modern advancements have made it possible to monitor marine ecosystems much more effectively, economically, and comprehensively than with more conventional approaches. A significant advancement is the utilization of cabled video observatories, which offer high-definition video footage for tracking fish populations and activity over time [32]. Machine learning (ML/DL) and AI have become revolutionary technologies in marine monitoring. By enabling real-time data processing, anomaly identification, and predictive modeling, these technologies improve the ability to monitor the environment at sea. AI applications are growing in developing clever, affordable solutions that replace labor-intensive, conventional techniques [33]. AI systems still need further development to overcome algorithmic biases and poor data quality. The breadth and resolution of observations of coastal ecosystems have increased thanks to advancements in marine technologies such as satellite monitoring, drones, and in situ sensor networks. These technologies, based on AI and deep learning, allow for collecting and analyzing massive amounts of data, offering vital insights into the dynamics and stresses of ecosystems. However, to effectively manage ecosystems in the face of global change, gaps in monitoring capacity must be filled, which calls for ongoing innovation. Cutting-edge underwater devices are being developed to detect marine pollution, mainly plastic trash [34]. Despite being at low to middle Technology Readiness Levels, these technologies have potential applications in monitoring programs. The necessity for customized solutions in marine monitoring is highlighted by creating a decision tool to choose suitable technologies depending on specific scenarios. New technologies are also essential for improving seafood traceability and combating illicit fishing. Integrating molecular genetics and electronic monitoring technologies into fisheries’ management improves surveillance and traceability and guarantees sustainable fisheries [35]. These technologies support productive and sustainable farming methods by enabling real-time data collection and prediction capabilities. Incorporating cutting-edge technologies into marine monitoring propels notable data gathering, processing, and administration advancements [36].

2.4. Influence of Climate Change on Marine Policies

Climate change’s impact on marine policies is a complex subject that calls for all-encompassing adaptation solutions in several sectors. The research identifies some crucial domains, such as fisheries’ governance, coastal adaptation, marine cargo insurance, and ecosystem management, where climate change affects marine policies. First off, marine cargo insurance is heavily impacted by climate change, especially in cold chains. Extreme weather events and climate change are occurring more frequently, disrupting global supply chains and increasing the risk of shipping containers while they are being stored in ports [37]. The need for more research on how climate change affects marine cargo insurance policies is highlighted because cargo owners have transferred these risks to marine cargo insurers. Climate change presents severe dangers to coastal systems. Hence, strategies for adaptation must be put in place. Still in its early stages, the adaptation policy cycle has notable shortcomings regarding geographic breadth, sectoral integration, and economic emphasis. Closing these gaps helps coastal communities better adapt to climate change and strengthens the resilience of coastal social–ecological systems. Climate change also hazards marine and coastal ecosystems, with differing reactions based on regional stresses and ecosystem features. Effective management necessitates a multi-species and multi-stressor strategy to forecast changes at the ecosystem level. Adverse effects can be lessened by addressing local stresses like coastal development and nutrient enrichment, guiding workable conservation strategies and spatial management plans. Climate change also has a significant impact on the governance of fisheries [38]. Furthermore, climate change adaptation must be considered in the design of future ports and marine projects. The present research focused on particular case studies and existing infrastructures, demonstrating that sound systems thinking is necessary when incorporating mitigation techniques for climate change into the design of marine projects [39]. The Mediterranean, particularly vulnerable to climate change because of rising coastal hazards, including erosion and floods, requires rigorous risk assessment techniques [40]. Sustainable development and management of coastal regions depend on policies addressing climate change’s short- and long-term effects. Climate change adaptation strategies must be incorporated into marine policy to ensure sustainable growth [41].

2.5. Multiple Facets across Borders in Legal Cooperation and Marine Governance

Specifically, marine ecosystem issues generally require cross-boundary cooperation and marine governance in areas where natural and administrative boundaries differ. The scholarly literature has identified various vital aspects and measures that must be included to improve naval governance and transboundary cooperation [42]. One part of the governance basis of the Council of Europe, “territorial and cross-border cooperation”, underlines that governance principles and processes are needed to underpin institutional capacity and regional development. European standards for local and regional governance processes might make this approach particularly relevant in regions such as Ukraine. Adaptation and long-term commitment are also valued in the Global Environment Facility Large Marine Ecosystems initiative, having a framework for international cooperation based on the ecosystem-based management of shared marine resources. Another essential tool to foster collaboration across borders is Transboundary Marine Spatial Planning [43]. Promoting collaborative governance resolves transboundary issues through stakeholder involvement, cross-sector integration, and government-to-government cooperation. Although the benefits of TMSP for marine governance are evident, the sustainability of transboundary projects will require heightened cooperation and capacity building in the future [44]. When overcoming the institutional barriers and taking advantage of local competitive advantages, the case of European Macaronesia is another example of the crucial importance of cross-border cooperation for MSP. This has also underlined the involvement of foreign affairs with all the relevant authorities. The GCLME research has also shown that cross-border ocean governance is crucial in areas experiencing significant biological and political issues. International agreements, such as those with the UNCLOS, might encourage collaboration [45]. The BBNJ Agreement represents a critical progressive global ocean governance system move. It integrates existing structures, processes, and institutions to support the conservation of marine biodiversity and sustainable use beyond national jurisdiction. In that vein, essential governance goals have to be pursued concerning protecting local livelihoods and fishery stocks, for example, against international organized crime in the form of foreign fishing vessels [46]. Approaches to stakeholder engagement must be applied to enhance ocean governance, ensuring transparency and inclusivity in collaboration, considering power differentials, and coordinating agendas of disjointed governance. Global sustainability with successful cross-border cooperation requires a multi-modal approach using sound governance principles in combination with collaborative systems thinking TMSP and international agreements such as the BBNJ [47].

2.6. Development of Economics in the Digital Age, Systems, and Marine Policies

Research examining these intersections shows that the digital era has significantly impacted marine policies and economic systems. For countries like Indonesia, whose marine potential is enormous but untapped because of low effectiveness and security levels, reforming marine policies in the digital age is essential to improving marine efficacy and security. Although obstacles like infrastructure constraints and policy adaptation still exist, integrating digital technology can enhance port connection, supply chain efficiency, and security systems. Digitalization is also essential for managing marine ecosystems, as demonstrated in Sulawesi, Indonesia, where resource management is revolutionized by technologies such as blockchain, GIS, and remote sensing. Although skill and infrastructure shortages prevent these technologies from reaching their full potential, they improve monitoring and prediction capacities. Therefore, a combination of traditional ecological knowledge and new instruments is required for effective deployment. The reduction in marine pollution in China has benefited the digital economy. According to spatial econometric research, the DE has a significant positive regional spillover impact and reduces marine pollution through direct and indirect effects. A non-linear, inverted U-shaped curve represents this relationship, indicating that whereas early digitalization initiatives may increase pollution, subsequent developments lead to decreases. Digital technology is also causing significant changes in the marine sector, especially in management and logistics. For example, blockchain technology improves marine logistics’ efficiency and trustworthiness, while the Internet of Things enhances traffic management and vessel–port communication [48]. While these advancements improve resource efficiency and transportation times, cybersecurity remains a significant worry. Because digital marketing methods make it possible to promote items more effectively and widely, the fishing sector is changing. To fully reap the rewards of internet marketing, which raises brand recognition and expands the consumer base, this transition necessitates more public awareness of ICT. Additionally, digital technology integration increases GDP growth and productivity in marine economic activity. Digitalization and spatial integration are suggested to improve fishing industry production systems’ productivity, focusing on staff skill development and digital literacy [49]. The Blue Economy idea emphasizes the significance of sustainable behavior backed by digital change. This approach will further create policies that are innovative and imaginative in their content, using technology in a balance of ecosystem preservation with economic growth to ensure the well-being of the community without necessarily sacrificing environmental integrity [50].

3. Components and Approaches

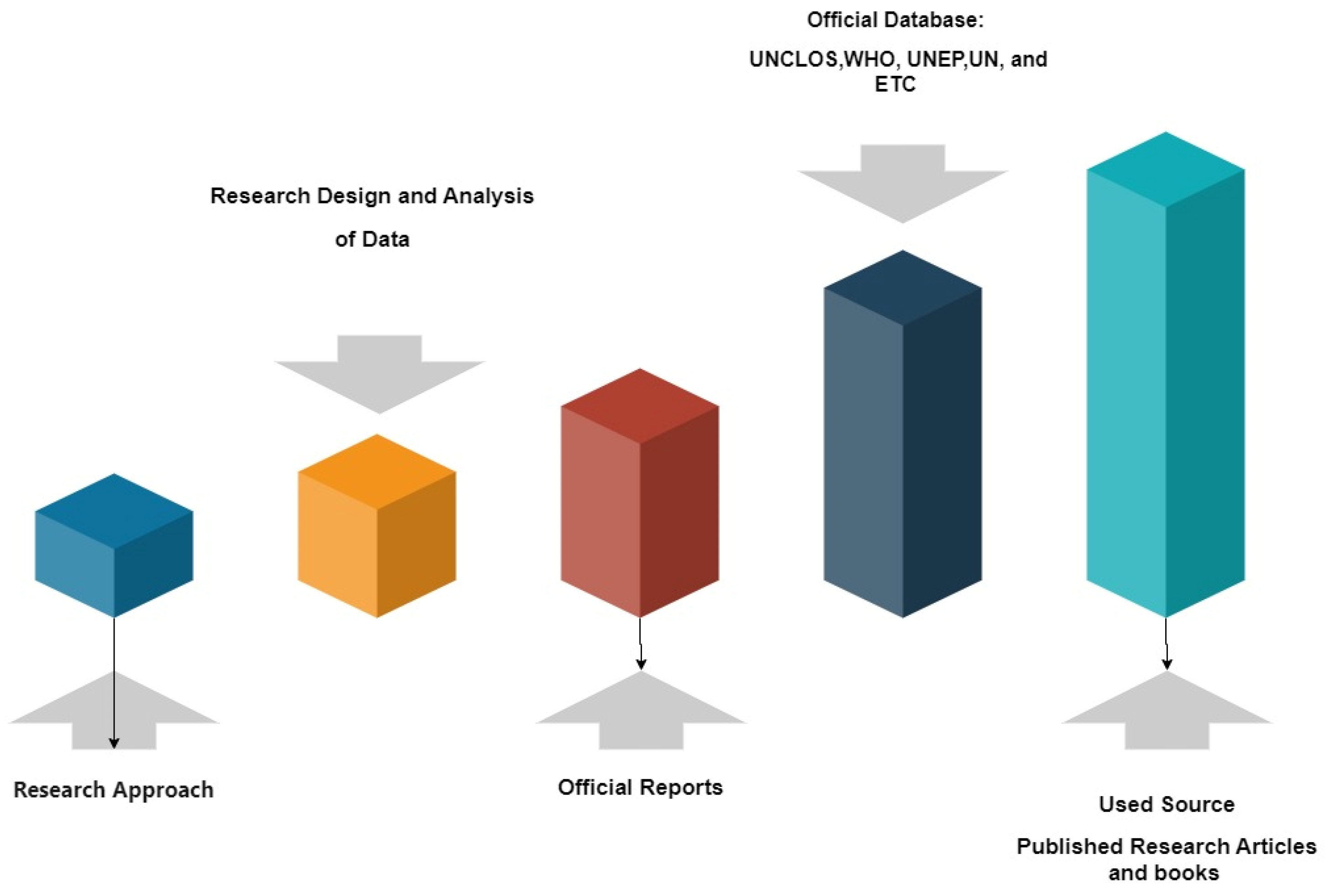

This study underscores how important it is to base any assessment of the effectiveness of marine rules in supporting environmental legislation and sustainability in BRI countries on a sound foundation of digital technology. The comparison of data across several BRI countries in the research serves to discover new ideas and best practices that enhance policy implementation. Digital technologies improve the monitoring and enforcement of environmental legislation, investor engagement, and public knowledge. In that respect, our project aims to produce insightful knowledge that will impact future advancements in marine policy systems, empowering them to be robust, flexible, and sustainable vis-à-vis global environmental issues [51]. Figure 3 shows the thorough methodology used in this study and describes the methodical approach to data collecting and analysis. It highlights the sequential processes—participant selection, intervention design, and evaluation metrics—used to guarantee validity and reliability. Well-organized systems thinking strengthens this study’s replicability and makes it easier to comprehend the research process, giving the findings a solid basis [52].

Figure 3.

The detail of the research design with knowledge of the study aims.

3.1. Protocol of Research

This study’s methodology combines several approaches into a cohesive context for tracking advancement. Words like action research, participatory action, BRI, marine industry, challenge, impact, and economics were permitted to be included anywhere in the title, abstract, or keywords of journal papers published in English starting in 2013. These papers were located using the Scopus search engine. It should be noted that the search phrases were not case-sensitive, and terms that had an asterisk next to them meant that derivative terms were also included. One potential issue with digital technology could be a challenge to environmental law. To reduce false positives in the sustainability results, these keyword combinations were designed to yield the most relevant content for the review [53]. The authors additionally conducted a full-length article search utilizing the straightforward search tool of the Journal of Participatory Research Methods’ database to enhance the search results with more resources, given the study’s emphasis on participatory research methodologies. Due to the functional limitations of the search engine provided by this journal and its specific focus on participatory research, the search parameters were narrowed down to only include terms related to digital technology. For example, this research paper evaluates how well digital technologies and marine regulations support environmental law and sustainability in countries taking part in the BRI through a comparative analysis, with an emphasis on published books, research articles, literature reviews of national and international laws, reports from international organizations like the World Bank and United Nations [54], and specific initiatives within BRI countries; the approach combines secondary data collection with policy document analysis [55]. The three parts of this study are background research (reading pertinent literature), data analysis (using both qualitative and quantitative methods), and reporting (assembling findings into thorough reports). These studies are presented at conferences, published in academic publications, and distributed to interested parties to impact future marine regulations and technology uses. This research intends to improve the efficiency of digital technologies and marine policies in attaining environmental sustainability in BRI nations by offering comprehensive and comparative views across multiple countries [56].

3.2. The Data Collection Point of Source

A rigorous analysis of the efficacy of marine legislation in BRI countries should be conducted using various data sources [57]. For instance, the World Bank maintains a wealth of environmental and economic data. In turn, the FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department is a source of information on fisheries management, and there is a reflective analysis of international marine policy within the UN Environment Programme [58]. The International Marine Organization provides guidelines concerning marine environmental policy, the Asian Development Bank reports on sustainable development in Asia, and national ecological agencies publish appropriate results. Moreover, the quality of the research can be improved due to comparative analyses comprised of reports [59].

3.3. Results

The study’s gathered data were examined to find meaningful patterns and revelations, thoroughly analyze and discuss, and identify essential relationships that highlight the significance of the findings. These findings offer practical applications for further research, add to the corpus of current knowledge, and stress the importance of these findings for shaping practice and policy, with the ultimate goal of advancing knowledge and promoting advancements in the pertinent sector.

3.3.1. The Role of Systems Thinking in BRI and Marine Policies, Including Technologies

Systems thinking is crucial for marine policies, including those relevant to BRI countries, as it promotes a general understanding of the interaction of environmental, social, and technological factors. It plays an indispensable role in developing holistic perceptions regarding the interplay among factors related to the environment, social life, and technology. It thus helps policymakers tackle challenges such as climate change, biodiversity loss, and socio-economic disparities among BRI countries [60]. Systems thinking within marine policy is not only much needed but also highly imperative in the context of the BRI, as it would appear to be an integrated understanding of environmental, social, and technological linkages. It will permit policy thinkers to work on complex challenges of socio-economic disparities across BRI countries. Systems thinking can promote collaborative governance by recognizing that marine ecosystems do not exist in a vacuum, allowing cross-border cooperation with shared marine resources [61].

Combining systems thinking and digital technologies also enhances data collection and analysis, allowing for sound decisions. Big data and remote sensing could serve in the monitoring and enforcement of marine-related regulations. All these could ensure that countries comply with various environmental laws, which could be an essential way of adapting policies to the dynamic nature of marine environments and the socio-economic contexts of different countries. Eventually, systems thinking reinforces sustainable practice and crystallizes the interests of many stakeholders, fostering resilience on marine governance [62]. By taking this approach, BRI countries can elaborate on comprehensive strategies that support environmental sustainability and address the social challenges of their peculiar contexts.

3.3.2. Developing Asia Accelerated

Due to robust export growth, especially in electronics, and strong domestic demand, emerging Asia’s growth picked up speed in the first quarter of 2024, as shown in Table 1. The growth estimate for the region in 2024 has been revised up to 5.0%, while the estimate for 2025 remains at 4.9%. According to current forecasts, headline inflation in emerging Asia will drop from 3.3% to 2.9% this year and stabilize at 3.0% in 2025 [63].

Table 1.

Economic forecasts for Asia and the Pacific.

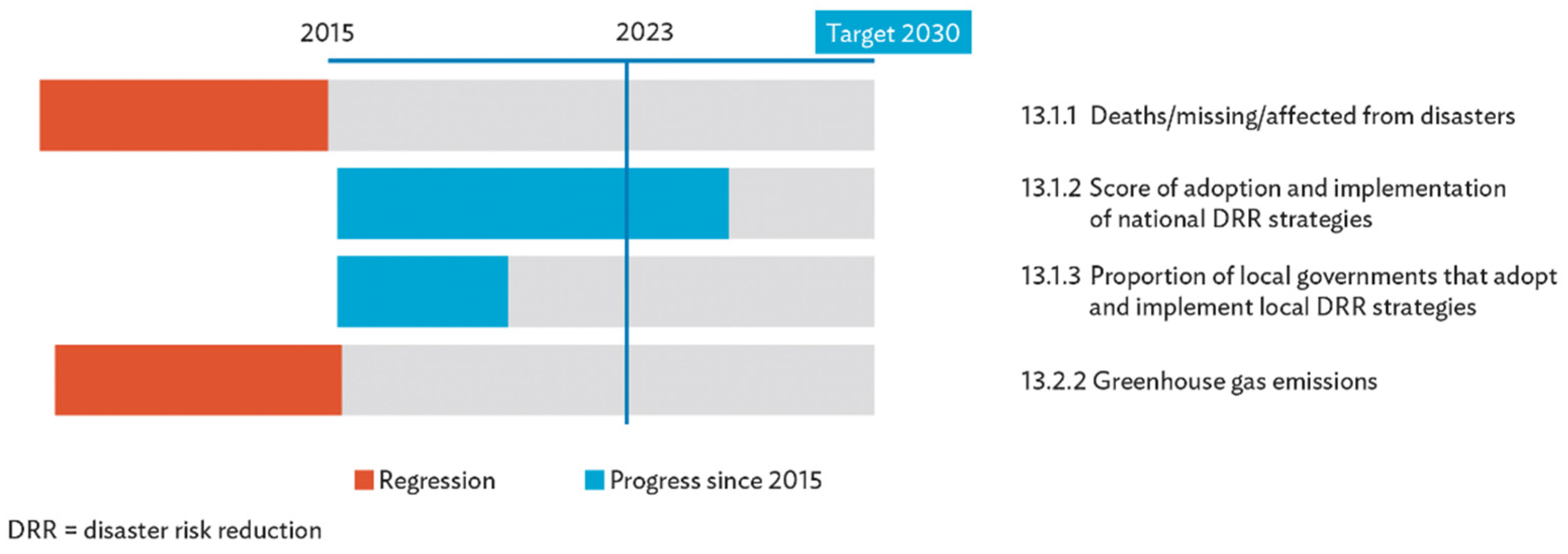

3.3.3. Climate Action Indicators

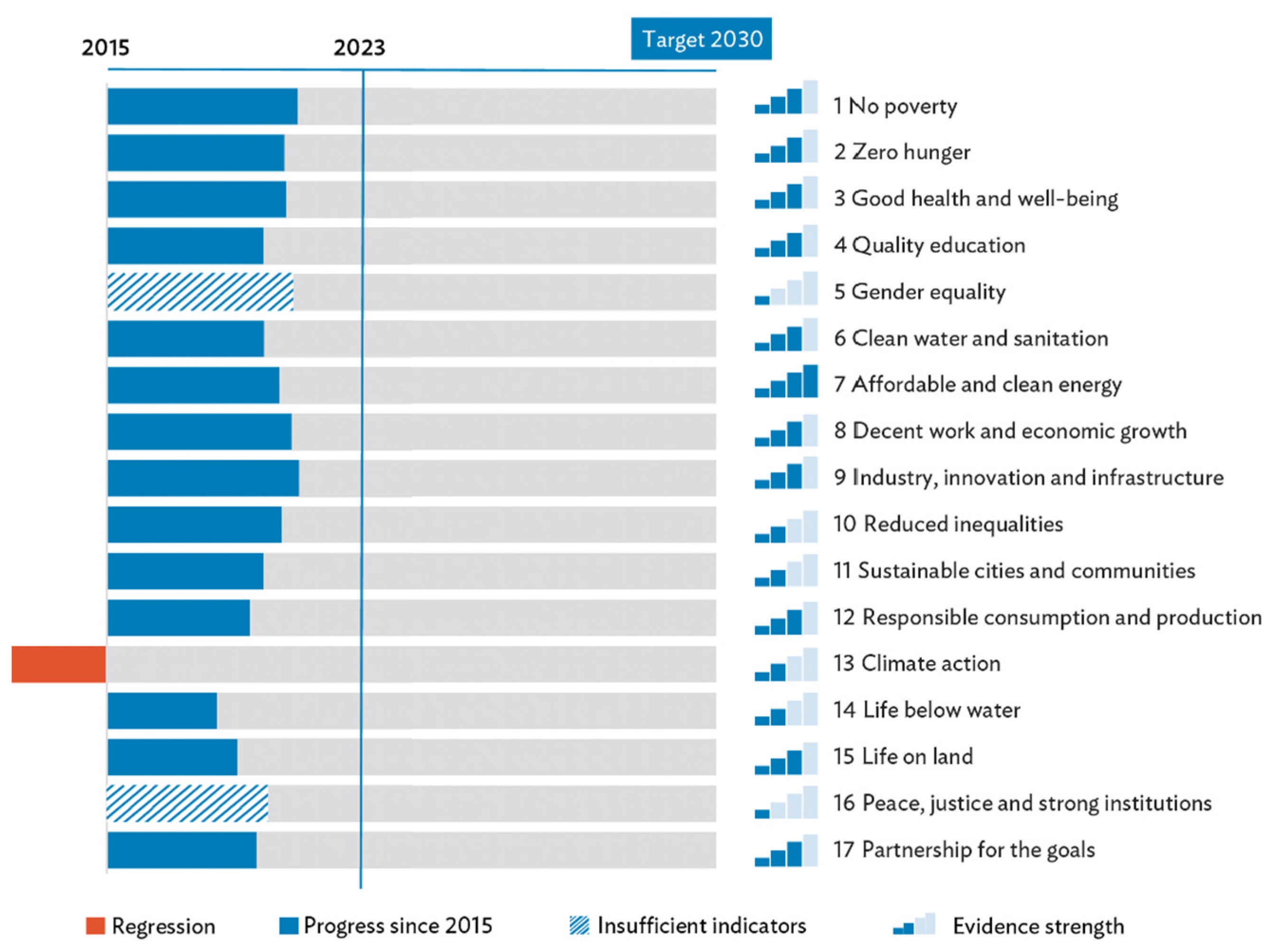

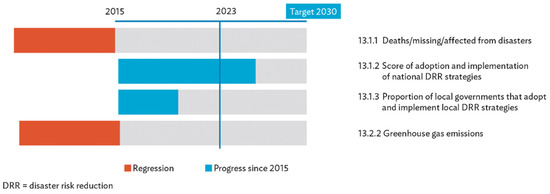

When SDG 13 is broken down into its four indicators, a closer look at progress toward the goal yields contradictory findings. As shown in Figure 4, Indicator 13.1.2 suggests that national governments in Asia and the Pacific region are on schedule to implement disaster risk reduction (DRR) programs by 2023. Indicator 13.1.3 indicates that the percentage of local governments that have approved and implemented localized DRR initiatives, however, has fallen short of the 2023 target [64]. In addition, it does not seem that these policy changes have decreased the number of fatalities, missing people, or people impacted by disasters (indicator 13.1.1). Alarmingly, indication 13.2.2 reveals that efforts to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions have regressed even more [65].

Figure 4.

The four indicators’ progress.

3.3.4. In Asia and the Pacific, SDG 13’s Climate Action Is Rapidly Regressing

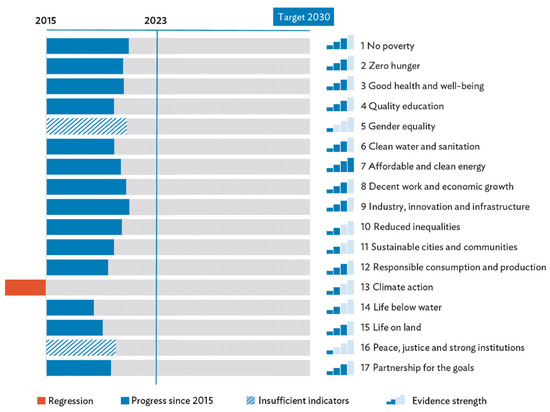

Data at the regional level indicate that Asia and the Pacific are witnessing a frightening regression in climate action advancement [66]. In terms of SDG advancement, data gathered by the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific at the national or economic level show that by 2023, shown in Figure 5, the region was not meeting the majority of SDG targets. Notably, there was an alarming regression in progress made toward SDG 13 climate action [67].

Figure 5.

Sustainable Development Goals. Source: Asian and Pacific Regional Economic and Social Commission of the United Nations. SDG Gateway for Asia–Pacific. https://data.unescap.org/dataanalysis/sdg-progress (accessed on 23 September 2024).

3.3.5. Rule of Law in South Asia Countries

South Asia’s Rule of Law varies significantly from country to country, with Nepal obtaining the highest (0.52) and Afghanistan scoring the lowest (0.32). India is not far behind Nepal in terms of protecting fundamental rights. It faces social challenges in the areas of civil and criminal justice. Sri Lanka continues to operate in a balanced manner, especially when it comes to security and order. On the other hand, as seen by their poor rankings, Pakistan and Bangladesh both face significant difficulties with regulatory enforcement and corruption. The region as a whole has structural problems with transparency, governance, and the legal system, as shown in Table 2, which emphasizes the need for change to strengthen the Rule of Law and the need for reforms in South Asia [68].

Table 2.

Rule of Law Index scored in South Asian countries.

3.3.6. The Artificial Intelligence Act (AIA)

The Artificial Intelligence Act (AIA) is intended to create a comprehensive regulatory system that classifies AI systems according to risk levels (unacceptable, high-risk, and low-risk), guaranteeing proper oversight and compliance procedures. This is accomplished by the legislative architecture for the AIA of the European Union. To supervise implementation and promote cooperation among member states, establishing a European Artificial Intelligence Board is essential to this architecture. Regulator-sponsored sandboxes will foster innovation while imposing strict limitations on high-risk AI systems, such as transparency requirements and conformance checks, as shown in Table 3. The EU’s commitment to ethical and responsible AI development is furthered by the AIA, which incorporates current data protection laws and guarantees that AI technology respects individuals’ rights to privacy [69].

Table 3.

AIA of the European Union’s components.

3.3.7. International Cooperation

Several essential structures and organizations are part of the legislative landscape that surrounds environmental management and marine law. In light of the unprecedented problems posed by climate change, the UNCLOS provides the legal systems thinking for marine governance, fostering amicable relations and sustainable resource management. MSP has the potential to increase the marine industry by 15%. It reduces stakeholder conflicts and enhances marine biodiversity while facilitating the organized use of marine spaces. Studies have shown that effective management techniques can improve fish stocks by 30%. Marine environmental management and adaptation strategies focus on preserving marine ecosystems while adjusting to environmental changes. As seen by the 20% drop in plastic trash entering seas, the UNEP coordinates global environmental activities that considerably reduce marine pollution and promote sustainable practices. By regulating shipping norms, the IMO has significantly decreased marine pollution and is working toward a 30% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. The Environmental Law and Climate Change section highlights the need for robust legal agendas to reduce the effects of climate change, with possible worldwide economic gains of over USD 1 trillion by 2030. By 2030, investments in sustainable fisheries might return USD 3 for every USD 1 spent, according to projections made by the OECD, which promotes international collaboration on sustainable marine practices, as shown in Table 4. These organizations and bases show how to tackle environmental sustainability and marine governance’s social challenges [70].

Table 4.

Line affords all-inclusive overview cooperation.

4. Analysis and Discussion

The interconnectedness between digital technologies, goals of environmental law, climate change impacts, and international cooperation combines to determine assessments of marine policy effectiveness in BRI participant nations. Even if many BRI countries have started embracing the benefits of sustainable marine governance, they still have a long way to go in implementing effective policies. Application and purposes range far and wide between states, some of which have laudable compliance with international agreements. Still, for others, due to limitations of resources and political will, the absence of meaningful enforcement of the law stands in the way of full compliance with its provisions [79]. One of the valuable ways to conceptualize the management and monitoring of the marine domain is through digital technology. Big data analytics, blockchain, and satellite images are some technologies that might finally improve accountability and transparency in marine resource management. Simultaneously, however, inequities in technological access among BRI countries may further increase marine governance processes [80]. All these relations are even more tangled by the threat that climate change-associated rising sea levels and increased acidity poses to marine environments and the livelihoods depending on them. Hence, the marine policies of BRI member countries need revision to incorporate initiatives that assure climate resilience, requiring heavy finance and coordination across national borders in most cases. Regional cooperation would be indispensable in managing transboundary environmental issues and shared marine resources [81]. It also becomes necessary to extend regional cooperation on sustainable practices that may be facilitated by collaborative systems thinking and governance improvement to take up initiatives like pollution control or cooperative fisheries management practices. Improvements in marine surveillance technologies, including autonomous underwater vehicles and remote sensing, provide new options for data gathering and enforcement, enabling governments to respond effectively to criminal activity and harm to the environment [82].

4.1. BRI-Participating and Marine Assistance

Incentives to comply with the marine rules, such as ‘blue carbon’ credits and sustainability certificates for fishing, might make the industry more viable within the economic context of the digital era. The success and viability of these projects depend upon how BRI member countries can handle the social aspects of marine governance in a rapidly changing world. This might enhance marine policy efficiency in BRI-participating countries and create marine ecosystems with continued health by fostering cooperation, utilizing technical developments, and harmonizing environmental legislation to sustainability goals. A comparison is proof of the differences in approaches and findings as to the extent to which marine policies in BRI countries support environmental legislation, sustainability, and integration of digital technology [83]. This study also highlights how digital technology may, in general, contribute a great deal to marine policy sustainability and efficiency within many geographical areas. To this end, reforming Indonesia’s marine policy is strongly recommended to improve marine security and effectiveness in the era at hand. Digital technology may be introduced into practice to enhance supply chain efficiency, port connectivity, and marine security systems accordingly. Nonetheless, infrastructure constraints and policy modifications continue to be major roadblocks. The sustainable growth of China’s marine economy is also largely attributed to digital technologies. The study highlights that technical innovation is essential for closing the gap between regions and encouraging environmentally friendly growth in marine industries. International law and technology have a crucial influence on marine policy [84]. The UNCLOS offers systems thinking for the sustainable management of marine resources, emphasizing the necessity of cross-border cooperation and legislative modifications to accommodate new technology [85]. Advanced technologies such as GIS and remote sensing are transforming the management of marine ecosystems in Sulawesi, Indonesia, yet obstacles, including policy systems thinking adaption and talent gaps, still exist.

The Blue Economy idea in Indonesia emphasizes how crucial digital transformation is to managing sustainable fisheries. Digital technology integration promotes community welfare while protecting ecosystems by facilitating efficient market access and resource consumption [86]. National governance contexts are the primary cause of disparities in marine policy amongst nations in the North Atlantic. Nonetheless, shared strategic objectives exist for industries like conservation and fisheries, indicating the possibility of coordinated policy responses [87]. Digitalization is essential for sustainability in expanding marine ecosystems in the Balkans. According to the study, exchanging knowledge among developed EU countries can aid in closing the digital divide and fostering a robust marine business environment. A comparative analysis assesses the efficacy of China’s marine fishery ecological policies, underscoring the necessity of well-coordinated sustainable development plans that balance ecological and economic factors. While both China and Japan follow international environmental law, Japan emphasizes domestic environmental preservation more, according to a comparative study of their marine ecological protection laws [88].

4.2. Cooperation in Digital Transformation and Legislation

While China has assumed increased legal responsibility for marine areas, EU marine and coastal policy has only recently been digitized. Digitalizing the technology and international legal frameworks is critical in devising a marine strategy under BRI. A creative approach to ICT solutions has thus emerged as an essential instrument for realizing the SDGs and raising living standards. Digital transformation might, therefore, be instrumental in improving sustainability and observing environmental legislation within diverse contexts, even if policy change, infrastructure, and regional particularities are ongoing obstacles to achieving this. Such initiatives can be further facilitated by international cooperation and information sharing that aid in securing the more equitable and sustainable use of marine resources globally [89]. In this way, digital technology integration has changed the mindset of various stakeholders for the sustainability of marine conservation efforts. AI, satellite surveillance, drones, and other data collection and processing developments have made real-time monitoring of aquatic environments possible. All these developments facilitate the detection of illicit fishing operations and the evaluation of the health of biodiversity, placing policymakers in a better position to make educated choices.

For example, AI algorithms can project fish populations and establish limits on catches that will not deplete fish stocks, thus guaranteeing the responsible utilization of marine resources. Even so, there are many challenges to securing longer-term results. The existing limitations go a long way in demonstrating how prolific digital technologies have become [90]. This obsolete or systems thinking could lead to enforcement and compliance gaps within certain BRI countries. This calls for an all-rounded scrutiny of areas where legislation can be improved. It is an opportune time for the legislatures to change the existing act, including habitat loss, climate change, and new technologies. Stakeholders are essential in enforcing policy [91]. The involvement of the local people has to cooperate to effectively conserve resources in the sea. Knowledge about the traditional practices that the communities have amassed for generations can become a part of the conservation process by involving local communities. It might provide a fundamental understanding of managing the ecosystem and reaching sustainability. For instance, ecological sustainability constitutes the basis for most conventional fishing methods, and such methods would, therefore, help complement modern conservation strategies. A few examples of marine conservation show the importance of adaptive management policies regarding new scientific findings and shifting environmental conditions at the ground level [92].

4.3. Promoting Environmental Law and Sustainability

Recent tendencies in the promotion of environmental law and sustainability emphasize the embedding of digital technologies, such as blockchain and big data analytics, into the design for heightened transparency and compliance in environmental governance. Countries participating in the BRI increasingly embrace a marine policy that supports ecological sustainability in a manner consonant with economic growth. Most of these policies are based on international contexts like UNCLOS, which sustainably provide guidelines for resource management. Moreover, there is an emerging appreciation that cross-border cooperation and community participation are twin ingredients of somewhat prudent environmental legislation. Alongside advances in monitoring and enforcement, there are other areas of financial incentives for sustainability practices to meet the challenges of climate change and long-term ecological integrity. SDG 14 aims to achieve the conservation of oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development. The oceans cover more than 70% of the Earth’s surface and are regulators of the Earth’s climate, besides being a significant source of food and conserving biodiversity. SDG 14 addresses the challenges of overfishing, pollution, and climate change affecting marine environments [93]. Some of the main goals it identifies to accomplish for SDG 14 include reduction in marine pollution, conservation of marine and coastal ecosystems, reduction in ocean acidification, and management of fishing to sustain overfishing levels and deter illicit activities. Marine biodiversity is one of the major components of ecosystem health, and it states that at least 10 percent of marine and coastal areas should be protected, a target most countries are still trying to reach. Oceans also contribute a lot to the global economy through industries such as fishing, tourism, and marine transport. This has been a very unsustainable activity, threatening marine life and human livelihoods. In view of reaching SDG 14, collaboration between governments, industries, and communities is required to ensure that management of the oceans is sustainable and the consequences human activities have on marine life are minimized. In fact, this goal is central to ensuring healthy seas for the future [94].

However, there is significant difficulty in coordinating policy throughout BRI countries. Disparities in cultural backgrounds and political and economic priorities can make cooperation difficult. Signing regional accords that uphold state sovereignty and advance mutual purposes is essential. In addition to facilitating resource allocation and information exchange, international collaboration can help countries address shared difficulties more successfully. One cannot ignore how marine policies affect the economy. Long-term economic gains from sustainable marine practices include enormous fish stocks and better travel opportunities; the local economies that depend on marine resources may be at risk due to overfishing and habitat damage caused by ineffective laws. For marine ecosystems to remain sustainable, policymakers must balance environmental protection and economic development. Climate change makes the requests of marine policy even more challenging. Through ocean acidification, sea level rise, and extreme weather, aquatic biodiversity is threatened, as well as the way of subsistence for populations that depend on such environments [95]. Fisheries’ management adapted to changes in conditions is one of the ways that essential ecosystems are conserved and policy resilience enhanced against climate change. Effective marine conservation among BRI countries requires stakeholder involvement, flexible regulatory bases, and the incorporation of digital technology. These frameworks must be driven to use old knowledge, allow international cooperation, and use recent technological developments [96].

5. Conclusions

The consequences of this study go further to expose the nature of marine regulations in shaping the legal aspects of BRI participant countries in terms of sustainability and environmental concerns. Overall, our investigation indicates that almost all BRI countries have instituted broad ecological laws, and their practical effects tend to rely on how they are implemented in a digitized platform. From the past literature, analytics, discussion, and satellite surveillance promise a revolution in maritime governance, real-time compliance monitoring, and international collaboration. Apart from this, it reiterates the suggestion of responsive governance structures but goes much deeper into the nature in which adaptive maritime policy is called for in response to climate change. According to the literature, the results reveal that innovative policymaking approaches, such as stakeholder integration and participatory governance, effectively promote resilience on marine ecosystems; this supports earlier research findings on the need for region-specific approaches toward the particular environmental problem that BRI countries face. The debate and analysis were also rightly carried out, showing that policy implementation varies from country to country; thus, specific strategies are needed to implement effective governance. The broader argument is that BRI nations must collaborate and share technology innovations and best practices to improve maritime policy. Further research would also be warranted into the long-term impacts of such adaptive strategies on marine ecosystems and new technical innovations to strengthen objectives toward sustainable development. Due to this innovation and cooperation, BRI countries can better manage maritime resources and significantly contribute to achieving several global environmental goals.

Limitations of the Study and Future Research Directions

The following are some of the central issues that future studies should focus on while considering the performance regarding marine regulations for digital technology, sustainability, and environmental law promotion in BRI countries. These include applying digital technologies, international cooperation among relevant nations, and re-evaluating international legal frameworks for climate change and the Buena governance of marine policy. It is essential to recognize that digital technologies form the core of marine policy [97]. Improvement in monitoring and prediction capacities for the current revolution of marine ecosystem management is immensely indebted to blockchain, machine learning, GIS, remote sensing, and other technologies. However, for the technologies mentioned above to come into complete application, delays in policy adaptation and infrastructural limitations will have to be surmounted. Future research should dwell on strategic solutions to these problems and further emphasize integrating traditional ecological knowledge with modern digital technology. Another critical attribute of good ocean governance is harmonizing and coordinating marine legislation and international cooperation [98]. The North Atlantic pilot study concludes that all countries need fewer regulations at all levels of government. Additional research should explore the multiplicities and gaps of marine policy in BRI member states through outputs like comparative analysis to examine and provide recommendations for the identified anomalies. Adaptive measures in establishing marine policy are required to control and mitigate the impacts of climate change. According to the MEMAS model, systems thinking should be applied to make marine resources sustainable, considering their resilience against climate change. Further research will have to establish how these models compare with regional risks and the particularities of the countries concerned. Other significant drivers of marine policy include technology and international law [99]. While UNCLOS and other global efforts provide guidelines, new technologies and ethical issues will necessitate continued outreach and adaptation. Research should first focus on developing international legal regimes that support evidence-based decision-making and incorporate evolving technologies [100]. The changes digital technologies are imposing on marine policy in Indonesia show how easy it is to increase marine security and efficiency. Further research will be required to explore how other BRI countries might make similar adaptations while overcoming technological adoption obstacles and ensuring maximum cybersecurity and marine security benefits. Finally, the upcoming Regional Agreement on Principle 10 highlights how digital environmental democracy could make environmental laws more effective by emphasizing digital technology integration and environmental access rights. Consequent studies should look into how the countries in the BRI use these bases to encourage human rights and ecological sustainability. Important aspects include using digital technology, cross-border cooperation, and bringing the marine policy in BRI countries in line with international law [101,102].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, and writing—original draft preparation, validation, formal analysis, and resources: X.W.; data curation, investigation, formal analysis, draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization, and project administration: M.B.K.; funding acquisition: X.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a Study on the Acceptability and Enforcement of Foreign Judgments in Indian Private International Law (Hunan Provincial Social Science Achievement Review Committee, Project Number: XSP22YBC245).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Komakech, R.A.; Ombati, T.O. Belt and Road Initiative in Developing Countries: Lessons from Five Selected Countries in Africa. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohashi, H. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in the Context of China’s Opening-up Policy. J. Contemp. East Asia Stud. 2018, 7, 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yan, M.; Shao, W.; Zhang, Q.; Ji, C.; Mahmood, R.; Wang, P. Improved Urbanization-Vegetation Cover Coordination Associated with Economic Level in Port Cities along the Maritime Silk Road. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 163, 112116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Hu, C. China’s Competition Regulation in the Maritime Industry: Regulatory Concerns, Problems and Potential Implications. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 251, 107082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutual Legitimation Attempts: The United Nations and China’s Belt and Road Initiative|International Affairs|Oxford Academic. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ia/article/100/3/1207/7663931 (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Youjin, L.; Kotsemir, M.; Ahmad, N. One Belt One Road Initiative and Environmental Sustainability: A Bibliometric Analysis. Environ. Econ. Policy Stud. 2024, 26, 403–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemizadeh, A.; Liu, W.; Zareian Baghdad Abadi, F. Assessing the Viability of Sustainable Nuclear Energy Development in Belt and Road Initiative Countries. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2024, 81, 101519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, L.; Chen, S.; Zhang, T.; Zhou, J.; He, J.; Xu, W.; Wang, T. Has the Maritime Silk Road Initiative Promoted the Development and Expansion of Port City Clusters along Its Route? Cities 2024, 151, 105127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H. The Development of Floating Nuclear Power Platforms: Special Marine Environmental Risks, Existing Regulatory Dilemmas, and Potential Solutions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, D.M.U.; Saeed, M.M.; Mahmood, D.A. Pakistan’s Maritime Security And China Pakistan Economic Corridor. Kurd. Stud. 2024, 12, 1620–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusriandari, W.; Saputro, G.E.; Sarjito, A.; Rinaldi, M. Analysis of Indonesia’s Cooperation with China Through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Can Provide Opportunities or Challenges for Indonesia to Realize the World Maritime Axis. East Asian J. Multidiscip. Res. 2024, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victorio, A.P.; Celeste, E.; Quintavalla, A. Greening AI? The New Principle of Sustainable Digital Products and Services in the EU. Common Mark. Law Rev. 2024, 61, 1019–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapter 12: The Twin Transition to a Green and Digital Economy: The Role for EU Competition Law in: Research Handbook on Sustainability and Competition Law. Available online: https://www.elgaronline.com/edcollchap-oa/book/9781802204667/book-part-9781802204667-20.xml (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- The Belt and Road Initiative: A Key Pillar of the Global Community of Shared Future—The Third Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation. Available online: http://www.beltandroadforum.org/english/n101/2023/1010/c124-895.html (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Opportunities and Challenges for Economic Growth in Sri Lanka by OG Dayaratna-Banda, PDCS Dharmadasa: SSRN. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3365378 (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- Song, A.Y.; Fabinyi, M. China’s 21st Century Maritime Silk Road: Challenges and Opportunities to Coastal Livelihoods in ASEAN Countries. Mar. Policy 2022, 136, 104923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlićević, D. ‘China Threat’ and ‘China Opportunity’: Politics of Dreams and Fears in China-Central and Eastern European Relations. J. Contemp. China 2018, 27, 688–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhou, R.; Wang, Q. Toward Better Governance of the Marine Environment: An Examination of the Revision of China’s Marine Environmental Protection Law in 2023. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1398720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Belt & Road Initiative: A Modern Day Silk Road|Global Law Firm|Norton Rose Fulbright. Available online: https://www.nortonrosefulbright.com/en/knowledge/publications/d2e05e9f/the-belt-road-initiative---a-modern-day-silk-road (accessed on 19 March 2024).

- Atta, N.; Sharifi, A. A Systematic Literature Review of the Relationship between the Rule of Law and Environmental Sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartor, M.; Orzes, G.; Di Mauro, C.; Ebrahimpour, M.; Nassimbeni, G. The SA8000 Social Certification Standard: Literature Review and Theory-Based Research Agenda. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 175, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanization-Induced Warming Amplifies Population Exposure to Compound Heatwaves but Narrows Exposure Inequality between Global North and South Cities|Npj Climate and Atmospheric Science. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41612-024-00708-z (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- Ariffin, M. Enforcement of Environmental Pollution Control Laws: A Malaysian Case Study. Int. J. Public Law Policy 2019, 6, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spring-Boarding into New Contexts: Reflections on Eve Darian-Smith’s Laws and Societies in Global Contexts: Contemporary Approaches—Reviews on Eve Darian-Smith, Laws and Societies in Global Contexts: Contemporary Approaches (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013)|International Journal of Law in Context|Cambridge Core. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/international-journal-of-law-in-context/article/springboarding-into-new-contexts-reflections-on-eve-dariansmiths-laws-and-societies-in-global-contexts-contemporary-approaches-reviews-on-eve-dariansmith-laws-and-societies-in-global-contexts-contemporary-approaches-cambridge-cambridge-university-press-2013/7C8E619C4EF26D409F3C02A050F9A09E (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- Hedlund, J.; Nohrstedt, D.; Morrison, T.; Moore, M.L.; Bodin, Ö. Challenges for Environmental Governance: Policy Issue Interdependencies Might Not Lead to Collaboration. Sustain. Sci. 2023, 18, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ershova, I.; Obukhova, A.; Belyaeva, O. Implementation of Innovative Digital Technologies in the World. Econ. Ann.-XXI/Ekon. Čas.-XXI 2020, 186, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkateswaran, P.S.; Ayasrah, F.T.M.; Nomula, V.K.; Paramasivan, P.; Anand, P.; Bogeshwaran, K. Applications of Artificial Intelligence Tools in Higher Education. In Data-Driven Decision Making for Long-Term Business Success; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 124–136. ISBN 9798369321935. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Jiang, X.; Khaskheli, M.B. The Role of Technology in the Digital Economy’s Sustainable Development of Hainan Free Trade Port and Genetic Testing: Cloud Computing and Digital Law. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, I.H.Y.; Su, J. Artificial Intelligence (AI) Learning Tools in K-12 Education: A Scoping Review. J. Comput. Educ. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaskheli, M.B.; Wang, S.; Yan, X.; He, Y. Innovation of the Social Security, Legal Risks, Sustainable Management Practices and Employee Environmental Awareness in The China–Pakistan Economic Corridor. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Zain, F.A.; Muhamad, S.F.; Abdullah, H.; Sheikh Ahmad Tajuddin, S.A.F.; Wan Abdullah, W.A. Integrating Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Principles with Maqasid al-Shariah: A Blueprint for Sustainable Takaful Operations. Int. J. Islam. Middle East. Financ. Manag. 2024, 17, 461–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguzzi, J.; Thomsen, L.; Flögel, S.; Robinson, N.J.; Picardi, G.; Chatzievangelou, D.; Bahamon, N.; Stefanni, S.; Grinyó, J.; Fanelli, E.; et al. New Technologies for Monitoring and Upscaling Marine Ecosystem Restoration in Deep-Sea Environments. Engineering 2024, 34, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochulor, O.J.; Sofoluwe, O.O.; Ukato, A.; Jambol, D.D. Technological Innovations and Optimized Work Methods in Subsea Maintenance and Production. Eng. Sci. Technol. J. 2024, 5, 1627–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Khaskheli, M.B. Innovation Helps with Sustainable Business, Law, and Digital Technologies: Economic Development and Dispute Resolution. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilley, A.; Dam Lam, R.; Lozano Lazo, D.; Dos Reis Lopes, J.; Freitas Da Costa, D.; De Fátima Belo, M.; Da Silva, J.; Da Cruz, G.; Rossignoli, C. The Impacts of Digital Transformation on Fisheries Policy and Sustainability: Lessons from Timor-Leste. Environ. Sci. Policy 2024, 153, 103684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neidig, C.; Lee, M.; Patrick, G.; Schloesser, R. Employing an Innovative Underwater Camera to Improve Electronic Monitoring in the Commercial Gulf of Mexico Reef Fish Fishery. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Plessis, F.; Goedhals-Gerber, L.; van Eeden, J. The Impacts of Climate Change on Marine Cargo Insurance of Cold Chains: A Systematic Literature Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2024, 23, 101018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, M.; Grilli, G.; Stewart, B.D.; Bark, R.H.; Ferrini, S. The Importance of Rebuilding Trust in Fisheries Governance in Post-Brexit England. Mar. Policy 2024, 161, 106034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J. A Jurisdictional Assessment of International Fisheries Subsidies Disciplines to Combat Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaleh, M.; Abdul-Rahim, A.S.; Liu, R.; Sun, Q. Nature of Property Rights and Motivation for Blue Growth: An Empirical Evidence from the Fisheries Industry. Nat. Resour. Forum 2024, 48, 184–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dananjaya, A.A.G.A.; Yasa, P.G.A.S. Regulation of peaceful passage rights in the territorial sea based on the united nations convention on the law of the sea (unclos). Policy Law Notary Regul. Issues 2024, 3, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, C.A.; da Silva, D.D.; Medeiros, S.E. Chapter 6: Multilevel Cooperation on Behalf of the Ocean Governance: The Brazilian Navy Case Study. In Governing Oceans; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2024; ISBN 978-1-03-531559-8. [Google Scholar]

- Tocco, C.L.; Frehen, L.; Forse, A.; Ferraro, G.; Failler, P. Land-Sea Interactions in European Marine Governance: State of the Art, Challenges and Recommendations. Environ. Sci. Policy 2024, 158, 103763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raharjo, S.N.I.; Pudjiastuti, T.N.; Nufus, H. Cross-Border Cooperation as a Method of Conflict Management: A Case Study in the Sulu-Sulawesi Sea. Confl. Secur. Dev. 2024, 24, 277–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, H. Critical Perspectives on the New Situation of Global Ocean Governance. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, Y.-C. Ocean Governance in Practice: A Study of the Application of Marine Science and Technology Research Techniques to Maritime Law Enforcement in Taiwan. Mar. Policy 2024, 163, 106081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, P. Cooperation—A Key for Successful Ocean Governance. WMU J. Marit. Aff. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, Q.; Khaskheli, M.B. Management Economic Systems and Governance to Reduce Potential Risks in Digital Silk Road Investments: Legal Cooperation between Hainan Free Trade Port and Ethiopia. Systems 2024, 12, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltran, M.; Tjahjono, B.; Suoneto, T.N.; Tanjung, R.; Julião, J. Rethinking marine plastics pollution: Science diplomacy and multi-level governance. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2024, 90, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emelianov, M.; Shapiro, G.I. Technological Oceanography. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Pepe, A.; Zamparelli, V.; Mastro, P.; Falabella, F.; Abdikan, S.; Bayik, C.; Sanli, F.B.; Ustuner, M.; Avşar, N.B.; et al. Innovative Remote Sensing Methodologies and Applications in Coastal and Marine Environments. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, 27, 836–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R. Revision of China’s Marine Environmental Protection Law: History, Background and Improvement. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1409772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harod, M. Sensors in the Marine Environments and Pollutant Identifications and Controversies. In Sensors for Environmental Monitoring, Identification, and Assessment; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 124–131. ISBN 9798369319307. [Google Scholar]

- OHCHR Databases. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/resources/databases (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- World Bank Open Data. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- Borja, A.; Berg, T.; Gundersen, H.; Hagen, A.G.; Hancke, K.; Korpinen, S.; Leal, M.C.; Luisetti, T.; Menchaca, I.; Murray, C.; et al. Innovative and Practical Tools for Monitoring and Assessing Biodiversity Status and Impacts of Multiple Human Pressures in Marine Systems. Envrion. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhailova, E.A.; Post, C.J.; Nelson, D.G. Integrating United Nations Sustainable Development Goals in Soil Science Education. Soil Syst. 2024, 8, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The International Maritime Organization’s Revised Greenhouse Gas Strategy: A Political Signal of Shipping’s Regulatory Future in: The International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law—Ahead of Print. Available online: https://brill.com/view/journals/estu/aop/article-10.1163-15718085-bja10162/article-10.1163-15718085-bja10162.xml (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- Szekely, G. The 12 Principles of Green Membrane Materials and Processes for Realizing the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. RSC Sustain. 2024, 2, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verboom, J.; Alkemade, R.; Klijn, J.; Metzger, M.J.; Reijnen, R. Combining Biodiversity Modeling with Political and Economic Development Scenarios for 25 EU Countries. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 62, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandsten, J. Challenges of Cross-Border Collaboration and Coordination in Marine National Parks. In A Case Study from the North-Eastern Skagerrak Region; GUPEA: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- A Quality Governance Framework for Sustainable and Resilient Socio-Ecological Systems—ProQuest. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/c32ec67c7511b0042466d39890aa8898/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y (accessed on 22 September 2024).

- ralph Economic Forecasts: Asian Development Outlook July 2024. Available online: https://www.adb.org/outlook/editions/july-2024 (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Asia and the Pacific’s Climate Bank. Available online: https://www.adb.org/climatebank (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Data and Statistics. Available online: https://www.adb.org/what-we-do/data (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- IF-CAP: Innovative Finance Facility for Climate in Asia and the Pacific. Available online: https://www.adb.org/what-we-do/funds/ifcap (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Key Indicators Database—Asian Development Bank. Available online: https://kidb.adb.org/economies (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- WJP Rule of Law Index. Available online: https://worldjusticeproject.org/rule-of-law-index (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Bhatt, H.; Bahuguna, R.; Swami, S.; Singh, R.; Gehlot, A.; Akram, S.V.; Gupta, L.R.; Thakur, A.K.; Priyadarshi, N.; Twala, B. Integrating Industry 4.0 Technologies for the Administration of Courts and Justice Dispensation—A Systematic Review. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D. Aligning the IMO’s Greenhouse Gas Fuel Standard with Its GHG Strategy and the Paris Agreement; International Council on Clean Transportation: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Stelzenmüller, V.; Lee, J.; South, A.; Foden, J.; Rogers, S.I. Practical Tools to Support Marine Spatial Planning: A Review and Some Prototype Tools. Marine Policy 2013, 38, 214–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marine Spatial Planning | Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission. Available online: https://www.ioc.unesco.org/en/marine-spatial-planning (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- Marine Environmental Management—Pollution Prevention Here, There and Everywhere. Available online: http://www.marineenvironmentalmgmt.com/ (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- Environment, U.N. UNEP—UN Environment Programme. Available online: https://www.unep.org/node (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- Q&A: How the IMO Is Working to Make Global Shipping Greener. Available online: https://unfoundation.org/blog/post/qa-how-the-imo-is-working-to-make-global-shipping-greener/?gad_source=1&gclid=Cj0KCQjwjNS3BhChARIsAOxBM6oJ11OvEZSq451udxFRj-rkoljyMxk8rz0hKh4Qmh9ck1jK0iGv2dYaAs0EEALw_wcB (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- Adeniyi, A.O.; Bakare, S.S.; Eneh, N.E. Legislative responses to climate change: A global review of policies and their effectiveness. Int. J. Appl. Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 6, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]