Simple Summary

The family Equidae enjoys an iconic evolutionary record, especially the genus Equus which is actively investigated by both paleontologists and molecular biologists. Nevertheless, a comprehensive evolutionary framework for Equus across its geographic range, including North, Central and South America, Eurasia and Africa, is long overdue. Herein, we provide an updated taxonomic framework so as to develop its biochronologic and biogeographic frameworks that lead to well-resolved paleoecologic, paleoclimatic and phylogenetic interpretations. We present Equus’ evolutionary framework in direct comparison to more archaic lineages of Equidae that coexisted but progressively declined over time alongside evolving Equus species. We show the varying correlations between body size, and we use paleoclimatic map reconstructions to show the environmental changes accompanying taxonomic distribution across Equus geographic and chronologic ranges. We present the two most recent phylogenetic hypotheses on the evolution of the genus Equus using osteological characters and address parallel molecular studies.

Abstract

Studies of horse evolution arose during the middle of the 19th century, and several hypotheses have been proposed for their taxonomy, paleobiogeography, paleoecology and evolution. The present contribution represents a collaboration of 19 multinational experts with the goal of providing an updated summary of Pliocene and Pleistocene North, Central and South American, Eurasian and African horses. At the present time, we recognize 114 valid species across these continents, plus 4 North African species in need of further investigation. Our biochronology and biogeography sections integrate Equinae taxonomic records with their chronologic and geographic ranges recognizing regional biochronologic frameworks. The paleoecology section provides insights into paleobotany and diet utilizing both the mesowear and light microscopic methods, along with calculation of body masses. We provide a temporal sequence of maps that render paleoclimatic conditions across these continents integrated with Equinae occurrences. These records reveal a succession of extinctions of primitive lineages and the rise and diversification of more modern taxa. Two recent morphological-based cladistic analyses are presented here as competing hypotheses, with reference to molecular-based phylogenies. Our contribution represents a state-of-the art understanding of Plio-Pleistocene Equus evolution, their biochronologic and biogeographic background and paleoecological and paleoclimatic contexts.

Keywords:

Equidae; Equinae; hipparionini; protohippini; equini; paleoecology; paleoclimatology; biochronology; phylogeny; evolution 1. Introduction

Studies on the evolution of the family Equidae started in the middle of the 19th century following the opening of the western interior of the United States. Marsh [1] produced an early orthogenetic scheme of Cenozoic horse evolution detailing changes in the limb skeleton and cheek teeth. Gidley [2] challenged the purported orthogonal evolution of horses with his own interpretation of equid evolution. Osborn [3] chose not to openly debate the phylogeny of Equidae but rather displayed Cenozoic horse diversity in his 1918 treatise on the unparalleled American Museum of Natural History’s collection of fossil equids. Matthew [4], however, did produce a phylogeny detailing 10 stages, actual morphological grades, ascending from Eohippus to Equus. Stirton [5] provided a widely accepted augmentation of Matthew’s earlier work with his revised orthogonal scheme of North American Cenozoic Equidae. Simpson [6] published his book on horses, which was the most authoritative account up to that time. His scheme was vertical rather than horizontal in its view of North American equid evolution, with limited attention paid to the extension of North American taxa into Eurasia and Africa. MacFadden [7] updated in a significant way Simpson’s [6] book, depicting the phylogeny, geographic distribution, diet and body sizes for the family Equidae.

This work principally focused on the evolution of Equus and its close relatives in North and South America, Eurasia and Africa during the Plio-Pleistocene (5.3 Ma–10 ka). We documented several American lineages that overlap Equus in this time range, whereas in Eurasia and Africa, only hipparionine horses co-occurred with Equus beginning at ca. 2.6 Ma, which we included in this work for their biogeographical and paleoecological significances. These taxa were reviewed by MacFadden [7] and Bernor et al. [8] including the references therein.

In the present manuscript, we aimed to revise and discuss the most recent knowledge on the Equinae fossil record, with the following goals:

- (1)

- Provide a systematic revision of tridactyl and monodactyl horses from 5.3 Ma to 10 ka. These taxa are discussed in chronological order, from the oldest to the youngest occurrence in each region starting from North and Central America, South America, Eastern Asia (i.e., Central Asia, China, Mongolia and Russia), Indian Subcontinent, Europe and Africa, with their temporal ranges, geographic distributions, time of origins and extinctions. Part of this information is also reported in Table S1;

- (2)

- Integrate the distribution of the fossil record with paleoclimate and paleoecological data in order to provide new insights into the evolution of Equinae and their associated paleoenvironments;

- (3)

- Compare and discuss the latest morphological and genetic-based phylogenetic hypotheses on the emergence of the genus Equus. Recently, Barrón–Ortiz et al. [9] and Cirilli et al. [10] provided phylogenies of Equus, including fossil and extant species, with different resulting hypotheses. We compare and discuss the results of these two competing hypotheses here;

- (4)

- Provide a summary synthesis of the major patterns in the evolution, adaptation and extinction of Equidae 5.3 Ma–10 ka.

2. Materials and Methods

We provide a revised taxonomy of all Plio-Pleistocene Equus across the Americas, Eurasia and Africa summarizing previously published research, as a group of 19 researchers from Europe and North and South America. We provide an updated chronology and geographic distribution for these species. We followed the international guidelines for fossil and extant horse measurements published by Eisenmann et al. [11] and Bernor et al. [12]. Over the last 30 years, these methods have been applied to several case studies in Equinae samples from North and South America, Eurasia and Africa, which led to the identification of new species as well as to the clarification of the taxonomic fossil record. More recently, Cirilli et al. [13] and Bernor et al. [14] provided a combination of analyses to analyze fossil and extant samples including univariate, bivariate and multivariate analyses on cranial and postcranial elements using boxplots, bivariate plots, Log10 ratio diagrams and PCA. We found that robust, overlapping statistical and analytical methods led to a finer resolution of the taxonomy and, ultimately, biogeographical and paleoecological studies. We provide essential information on those species we recognized in the record under consideration.

The taxonomic revision of the 5.3 Ma to 10 ka equid genera and species is given below and includes the authorship, chronological and paleobiogeographic ranges and some historical and evolutionary considerations on the taxon. A reduced emended diagnosis of the species is reported in the Supplementary Materials in order to offer the most relevant anatomical features to identify the taxon. Additional information is reported in Table S1.

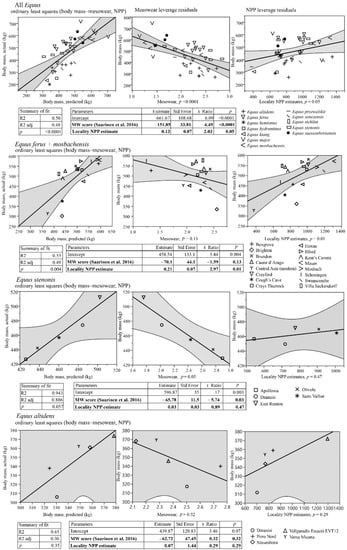

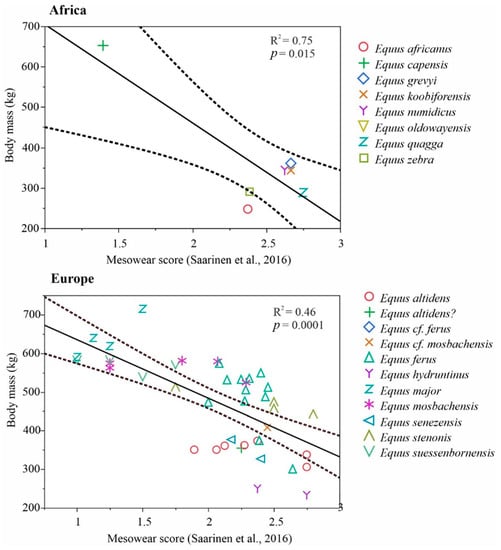

We compiled a global Neogene dataset of Equinae body mass estimates and paleodietary information for extensive palaeoecological analyses. These data were collected during several museum visits and complemented with data from publications and databases. Paleodietary information included results from traditional mesowear [15], low-magnification microwear [16] and isotopic analyses of equids from American, Eurasian and African localities (Tables S2 and S3). Net primary productivity (NPP) estimates were calculated for equine localities from the mean hypsodonty and mean longitudinal loph counts of large herbivorous mammal communities using the equation of Oksanen et al. [17]. The equation was as follows: NPP = 2601 − 144HYP − 935 LOP, where HYP is the mean ordinated hypsodonty, and LOP is the mean longitudinal loph count.

For the selected localities, body mass estimates based on metapodial measurements of equine paleopopulations [18,19], univariate mesowear scores calculated using the method of Saarinen et al. [20], and NPP estimates [17] were included to test whether the diet and productivity of the paleoenvironments were connected with body size patterns in equine horses. For this purpose, we used ordinary least squares linear models with body mass estimates as the dependent variable and the mean mesowear scores and NPP estimates as the explaining variables. These analyses were based on Eurasian and African Equus because of the large amount of data available and high variation in the ecology and environments of that genus during the Pleistocene, particularly in Europe but also, to some extent, in Asia and Africa. Because of slight methodological differences concerning the North American equine data [21] (Section 6.2 in the Supplementary Materials), we discuss them separately from Eurasian and African Equus in the context of the patterns revealed by the Eurasian and African Equus models. We also discuss the paleoenvironmental and habitat properties of key equine species based on what is known regarding the vegetation type and climate in their environments/paleoenvironments. Furthermore, we compared the patterns in the equine body size evolution, dietary ecologies and paleoenvironments between the continents and discuss how differential changes in biome distribution on the different continents could explain the observed differences in the body size patterns between continents.

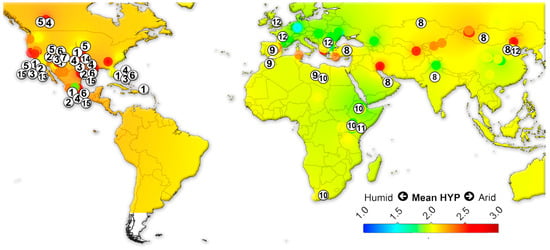

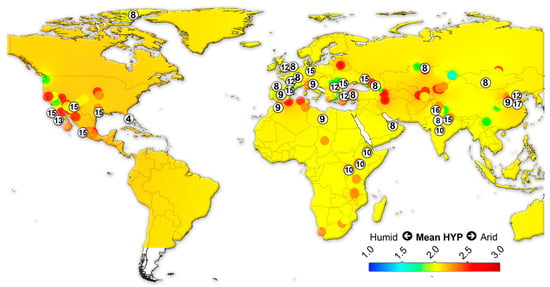

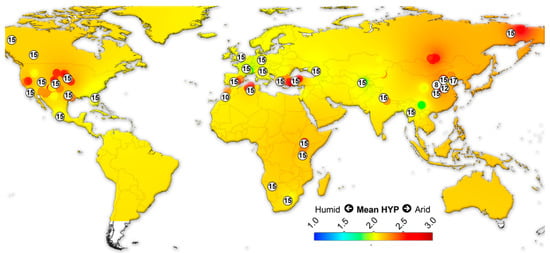

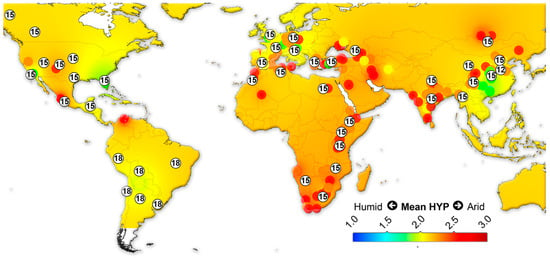

We assembled data on the large herbivorous mammals (i.e., Artiodactyla, Perissodactyla, Proboscidea and Primates) from the NOW database [22] and calculated the mean ordinated crown height for each locality (Table S4) following Fortelius et al. [23] for lists with at least two species with a hypsodonty value. All NOW localities between 7 Ma to recent from North and South America, Eurasia and Africa were included in the study and divided into four different age groups: 7–4 Ma; 4–2.5 Ma; 2.5–1.5 Ma; 1.5 to the recent. Mean ordinated crown height is a robust proxy for humidity and productivity at the regional scale [23,24,25,26]. We plotted the results onto present-day maps and interpolated between the localities using Quantum GIS 3.14.16 Pi. For the interpolations, thematic mapping and grid interpolation were used with the following settings: 20 km grid size; 800 km search radius; 800 grid borders. The interpolation method employed an inverse distance-weighted algorithm (IDW).

Finally, we discuss the most recent phylogenetic outcomes on the origin of the genus Equus. We compared the morphological-based cladistic results of Barrón-Ortiz et al. [9] and Cirilli et al. [10] with the genomic-based analyses of Orlando et al. [27], Jónsson et al. [28] and Heintzman et al. [29] in order to identify similarities between the two different cladistic approaches.

3. Systematics of the Equinae since 5.3 Ma in North, Central and South America

3.1. North and Central America

Horses have been commonly found in numerous terrestrial North and Central American vertebrate faunas. From the Middle Miocene through the Early Pleistocene, the diversity of horses encompassed the genera Astrohippus, Boreohippidion, Calippus, Cormohipparion, Dinohippus, Nannipus, Neohipparion, Pliohippus, Protohippus, Pseudohipparion and an Hipparionini of indeterminate genus or species. The genus Equus is commonly interpreted to have first appeared during the Blancan North American Land Mammal Age (NALMA), though recent analyses propose an earlier origin of crown-group Equus that extends into the Middle to Late Pliocene [29]. Nevertheless, the genus peaked in diversity and widespread geographic distribution during the Pleistocene. In the particular case of North and Central America, we use Equus in the broad sense (i.e., sensu lato), as the generic taxonomy of this group of equids has not been resolved and is an area of ongoing study (e.g., [9,10,29]).

What follows is a summary of the species of equids present in North and Central America from the Late Miocene to the Late Pleistocene (Hemphillian to Rancholabrean NALMAs) based on a review of the literature. In the particular case of Equus sensu lato, we recognized potentially valid species based on a meta-analysis of relevant studies (published between 1901 and 2021; n = 68) discussing fossil specimens of this group of equids; details of this analysis are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

- 1. Calippus elachistus, Hulbert, 1988 [30] (Right Mandibular Fragment with m2–m3, UF342139). This species seems to be restricted to Florida (USA) from the Late Miocene to the Late Hemphillian. The occlusal dimensions of its cheeck teeth are much smaller than any other species of Calippus, except Ca. regulus, with slightly smaller occlusal dimensions in the early to middle wear stages and significantly smaller basal crown lengths than Ca. regulus.

- 2. Calippus hondurensis, Olson and McGrew, 1941 [31] (Partial Skull Containing Left P2–M3 and Right P2–4, WM 1769). This species has been reported in Puntarenas (Costa Rica), Gracias (Honduras), Mexico (Guanajuato, Hidalgo, Jalisco and Zacatecas) and in the USA (Florida). It may be distinguished by its small size and relatively small protocone.

- 3. Dinohippus leardi, Drescher, 1941 [32] (M1, CIT 2645). This species has been recorded from the Late Miocene in California (USA). The size of the molars is similar to that of Pliohippus nobilis or larger in unworn teeth.

- 4. Dinohippus spectans, Cope, 1880 [33] (Left M2 with Associated or Referred P2, AMNH 8183). This species has been recorded in Oregon, Nevada, California, Texas and Idaho (USA) dating to the Late Miocene, with molar teeth of larger size than those of any of the extinct American horses, except Equus excelsus, approximately equal to those of Hippidion principale.

- 5. Astrohippus ansae, Matthew and Stirton, 1930 [34] (Partial Left Maxilla with P2-M3, UC30225). This species is a Hemphilian–Blancan species recorded in Zacatecas (Mexico), New Mexico, Oklahoma and Texas (USA).

- 6. Astrohippus stockii, Lance, 1950 [35] (Palate with P2-M2, Front Portion of M3 on the Right Maxilla and P2-M2 on the Left One, CIT3576). This species has been recorded in Chihuahua, Guanajuato and Jalisco (Mexico) and Florida, New Mexico and Texas (USA), from the latest Hemphilian to Blancan NALMAs. Astrohippus stockii is smaller than A. ansae, but it possesses higher-crowned cheek teeth [35]. In recent phylogenetic analyses, A. stockii was recovered as the sister group to the clade composed of “Dinohippus” mexicanus plus Equus sensu lato [8,36] or the sister group to the clade composed of successive species of “Dinohippus” (i.e., “Dinohippus” leardi, “Dinohippus” interpolatus, Dinohippus leidyanus and “Dinohippus” mexicanus) plus Equus sensu lato [37].

- 7. Dinohippus interpolatus, Cope, 1893 [38] (First and Second Upper Molars, Plate XII, Figures 3 and 4). This is a late Hemphillian-Blancan species that has been recorded in Hidalgo and Zacatecas (Mexico) and in California, Kansas, New Mexico and Texas (USA).

- 8. Dinohippus leiydianus, Osborn, 1918 [3] (Skull, Jaws, Vertebrae, Fore and Hind Limbs, Considerable Portions of the Ribs and Other Parts of the Skeleton of One Individual, AMNH 17224). This species comes from the late Hemphillian–Blancan with records in Alberta (Canada) and in Arizona, California, Kansas, Nebraska and Oklahoma (USA).

- 9. Dinohippus mexicanus, Lance, 1950 [35] (Partial Left Maxilla with P2-M3 and Part of the Zygomatic Arch, LACM-CIT 3697). This species has been found in Chihuahua, Guanajuato, Jalisco, Hidalgo, Nayarit and Zacatecas (Mexico) and in California, Florida, New Mexico and Texas (USA) from Hemphillian to Blancan NALMAs. It is a medium-sized monodactyl equine horse.

- 10. Cormohipparion occidentale, Leidy, 1856 [39] (Four Left and One Right Upper Cheek Teeth, ANSP 11287). This species is a Hemphillian–Blancan species recorded in California, Florida, Nebraska, New Mexico and Oklahoma (USA). It is a large and hypsodont North American hipparion.

- 11. Nannippus aztecus, Mooser, 1968 [40] (Fragmented Right Maxillary with P3–M3, FO 873). This species has been recorded in Mexico (i.e., Chihuahua, Guanajuato and Jalisco) and in the USA (i.e., Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma and Texas) from the latest Hemphillian to Blancan NALMAs. It is a small-sized horse.

- 12. Nannippus lenticularis, Cope, 1893 [3] (Two Upper Cheek Teeth). This species has been recorded from Hemphillian to Blancan NALMAs in Alberta (Canada) and in Alabama, Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma and Texas (USA).

- 13. Nannippus peninsulatus, Cope, 1885 [41] (M2, AMNH8345). This is a Hemphillian–Blancan species with records in Guanajuato, Hidalgo, Jalisco and Michoacan (Mexico) and in Arizona, Florida, Kansas, Nebraska, New Mexico and Texas (USA). Nannippus peninsulatus was a highly cursorial equid that appears to have been functionally monodactyl [42,43]. It had an estimated body mass of 59.6 kg [44].

- 14. Neohipparion eurystyle, Cope, 1893 [38] (TMM 40289-1). This species has been recorded in Alberta (Canada); Guanajuato, Hidalgo, Jalisco and Zacatecas (Mexico); Alabama, California, Florida, Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma and Texas (USA) from the Hemphillian to Blancan NALMAs. It is a very hypsodont medium-sized hipparion.

- 15. Neohipparion leptode, Merriam, 1915 [45] (Lower Molar, UCMP 19414). This species is a Hemphillian–Blancan species recorded in California, Kansas, Nebraska, Nevada, Oklahoma and Oregon (USA). It is a large hipparion.

- 16. Hipparionini genus and Species Indeterminate. Hulbert and Harington [46] reported a remarkable specimen of a Hipparionini equid from the Canadian Arctic, which represents the northernmost fossil record of an equid reported to date. It was found in an Early Pliocene deposit (~3.5–4 Ma) from the Strathcona Fiord, Beaver Pond locality, Ellesmere Island, Canada [46]. The specimen consists of associated maxillae and premaxillae with the right dI1 and dP2–dP4 and the left dP1–dP4 of a young foal (approximately 6–10 months of age) [46]. It is a relatively large hipparionine equid (estimated adult tooth row length of 150 mm), with deciduous premolars that have low crowns; complex enamel plications; oval, isolated protocones; a facial region that shows a reduced preorbital fossa located posterior to the infraorbital foramen [46]. This combination of traits is not known in any contemporaneous North American hipparionines, but it is found in some Asiatic hipparionines, particularly Plesiohipparion, indicating possible affinities with this group and suggesting a previously unrecognized dispersal event from Asia into North America [8,46]. Alternatively, the Ellesmere Island hipparionine could represent a previously unknown autochthonous lineage of high-latitude North American hipparionines that potentially evolved from the mid-Miocene North American Cormohipparion [46].

- 17. Neohipparion gidley, Merriam, 1915 [45] (Left M3, UCMP 21382). This species is a Hemphillian species recorded in California and Oklahoma (USA). It is the largest of the North American hipparions.

- 18. Boreohippidion galushai, MacFadden and Skinner, 1979 [47] (Partial Skull with Well-Preserved Dentition, AMNH 100077). This is a late Hemphillian horse from Arizona (USA).

- 19. Cormohipparion emsliei, Hulbert, 1987 [48] (partial skull with most of the right maxilla including dP1, P2-M3; right and left premaxillae with I1–I3; edentulous fragment of the left maxilla with alveoli for dP1 and P2). UF 94700. All elements possibly belong to the same individual as they present similar stages of tooth wear and preservation. It is a species recorded in the latest Hemphillian to Blancan NALMAs in Alabama, Florida and Louisiana (USA). It is a medium-sized species of Cormohipparion.

- 20. Pseudohipparion simpsoni, Webb and Hulbert, 1986 [49] (Associated P3-M1, UF 12943). This is a latest Hemphillian species recorded in Florida, Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas (USA).

- 21. Pliohippus coalingensis, Merriam, 1914 [50] (UCMVP 21341). This species is a Pliocene horse from California (USA).

- 22. Nannippus beckensis, Dalquest and Donovan, 1973 [51] (Partial Skull with Right and Left P2–M3, TMM41452-1). This is a Blancan species from Texas (USA). This species is a medium-sized and moderately hypsodont hipparion.

- 23. Equus simplicidens, Cope, 1892 [52] (Left M1, TMM 40282-6). This species is interpreted to have been a medium- to large-sized equid with primitive dentition [53], recorded in Baja California (Mexico) and Arizona, California, Idaho, Kansas, Nebraska and Texas (USA) from Blancan to Irvingtonian. The species was initially based upon fragmented molars, with sizes comparable to E. occidentalis and E. caballus [52]. According to Skinner [54], E. simplicidens shows great similarities in the skull and dentition with the modern Equus grevyi, and the differences in the skull are small and expected in temporal and geographic separation. Gidley [55] described the Hagerman horses based upon characters common to all zebrine horses, with taxonomically significant differences from non-zebrines, but the characters used to distinguish it from other zebrines are of doubtful validity [56]. Comparing E. simplicidens with the East African Grevy’s zebra, E. grevyi, Skinner [54] included both in the subgenus Dolichohippus [57]. This proposal was questioned by Forsten and Eisenmann [57], as the cranial similarities found by Skinner [54] might be allometrically related to the large skull size [57]. Furthermore, Skinner [54] did not compare the basicranium, missing the comparison of Franck’s Index (i.e., the distance from the staphylioin to the hormion and from the hormion to the basion). The index was considered phylogenetically important, as the lengthening of the hormion to the basion distance seems to have led to a decrease in the index during Equus evolution, with a high index being related to a more primitive character than a lower derived index [57]. In Forsten and Eisenmann’s [57] analysis, both E. simplicidens and Pliohippus (Dinohippus), considered the generic ancestor of Equus, presented a high index, while E. grevyi and the other extant species presented lower indices. Following Matthew [4], Forsten and Eisenmann [57] also suggested E. simplicidens should be included in the subgenus Plesippus [4,58]. Equus simplicidens has long been considered the earliest common ancestor of Equus [57], but a recent analysis of the genus Equus suggested that Plesippus and Allohippus should be elevated to a generic rank, indicating Allohippus stenonis as the sister taxon to Equus and Plesippus simplicidens and P. idahoensis as the sister taxa to the Allohippus plus Equus clades [9]. On the other hand, recent cladistic analyses combined with morphological and morphometrical comparisons of skulls suggest E. simplicidens as the ancestor of Equus, not endorsing Plesippus and Allohippus at the genus or subgenus level [10].

- 24. Equus idahoensis, Merriam, 1918 [59] (Upper Left Premolar, UCMP 22348). This is a Blancan and early Irvingtonian species recorded in Arizona, California, Idaho and Nevada (USA). The type locality is Locality 3036C, in the beds of the Idaho locality, near Froman Ferry on the Snake River, 8 mi SW Caldwell, Idaho. According to Winans [56], none of the traits from the original description of E. idahoensis are unique to this species. However, large samples of specimens (e.g., Grandview, Idaho; 111 Ranch, Arizona) have been referred to as E. idahoensis, which have distinctive morphological features [9,60] that indicate that this is a potentially valid species. The cheek teeth are large and heavily cemented.

- 25. Equus enormis, Downs and Miller, 1994 [61] (The holotype, IVCM 32, is a partial skull and right and left mandibles, with the right distal humerus, right radius-ulna, MCIII, unciform, magnum, trapezoid and MCIII, phalanges 1, 2, and 3 of the manus; partial pelvis, right femur, MTIII with MTII and MTIV and phalanx 3 of the pes from Vallecito Creek, Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, San Diego County, California, USA). This species is known primarily from the late Blancan – Irvingtonian of California (USA). Equus enormis is a large-sized monodactyl horse with an estimated height at the withers of 1.5 m.

- 26. Equus cumminsii, Cope, 1893 [38] (Fragmentary Upper Molar, TMM 40287-14). This small species has been recorded in Kansas and Texas (USA) from Blancan to early Irvingtonian (NALMAs). Although it is poorly represented by fossils and the type of specimen is a single damaged tooth, some authors consider this species as an early ass based on dental morphology [60,62,63].

- 27. Equus calobatus, Troxell, 1915 [64] (Left MTIII, YPM 13470). This species is a large stilt-legged horse reported from the late Blancan to early Rancholabrean NALMAs, with records in Alberta (Canada); Aguascalientes (Mexico); Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma and Texas (USA). The original discovery consisted of “unusually long and slender” limb bones [64] from Rock Creek, Texas, but no single holotype specimen was designated. Hibbard [65], therefore, selected YPM 13460 as the lectotype. Because the lectotype and cotypes are limb bones with no distinctive characters other than the large size and relative slenderness of the metapodials, there are few morphological criteria available for evaluating this species. Multiple studies [29,56] have synonymized E. calobatus with Equus (or Haringtonhippus) francisci, but other studies consider it a valid species [66,67].

- 28. Equus scotti, Gidley, 1900 [68] (Associated Skeleton with Skull, Mandible, Complete Feet and Forelimb Bones, One Complete Foot and Hindlimb and All the Cervical, Several Dorsal and Lumbar Vertebrae, AMNH 10606). This species is recorded from the late Blancan to Rancholabrean NALMAs in Alberta, Ontario, Saskatchewan and Yukon (Canada) and in California, Florida, Idaho, Kansas, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma and Texas (USA). Winans [54] also interpreted E. scotti to be on average slightly smaller than E. simplicidens, but the measurements provided in that study actually indicate the opposite, and subsequent review confirms that E. scotti was of a larger form than E. simplicidens.

- 29. Equus stenonis anguinus, Azzaroli and Voorhies, 1993 [69] (Complete Skull and Jaw, USNM 23903). This is a late Blancan species recorded in Arizona and Idaho (USA). It is described as similar to E. stenonis from the Early Pleistocene of Italy, with skull dimensions falling within the size range of this latter species [69]; however, the limb bones are, on average, more elongated. Equus stenonis anguinus possesses a preorbital pit and a deep narial notch as do the European E. stenonis samples.

- 30. Equus conversidens, Owen, 1869 [70] (Fragmentary Right and Left Maxilla with All Cheek Teeth, IGM4008, Old Catalog Number MNM-403). This is a widespread species reported to have ranged from the Irvingtonian to Rancholabrean with a geographic distribution encompassing North and Central America: Alberta (Canada); Aguacaliente de Cartago (Costa Rica); Apopa Municipality (El Salvador); Aguascalientes, Chiapas, Hidalgo, Jalisco, Michoacán, Nuevo Leon, Puebla, Oaxaca, San Luis Potosi, Sonora, Estado de Mexico, Tlaxcala, Yucatán and Zacatecas (Mexico); Azuero Peninsula and El Hatillo (Panama); Arizona, California, Florida, Kansas, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Texas and Wyoming (USA). The holotype specimen from the Tepeyac Mountain was described by Owen [70] based upon photos [71]. Owen considered the species to be almost identical to E. curvidens (South American E. neogeus) but with cheek tooth rows converging towards their anterior ends. Cope [72] interpreted the anterior convergence of the cheek tooth rows to be an artifact of the restoration compounded by the photography and assigned the specimen to E. tau, albeit without any stated justification. Gidley [69] interpreted the two sides of the maxilla to be from different individuals, since they were found separately and with missing broken edges. Hibbard [65] provided a reconsideration of the specimen and confirmed that Cope [68] was correct regarding the distortion of the palate and that Gidley [73] was incorrect regarding the two sides deriving from different individuals. Azzaroli [74] described a fragmentary skull (LACM 308/123900) from Barranca del Muerto near Tequixquiac, Mexico, in which the “two tooth rows converge rostrally, giving evidence that the palate of the holotype (of E. conversidens) was correctly mounted and that Owen’s name is after all appropriate”.

- 31. Equus lambei, Hay 1915 [75] (~200 ka–~10 ka) (nearly complete skull from a female, USNM8426, collected from Gold Run Creek in the Klondike Region, Yukon Territory, Canada). This species inhabited the steppe–tundra grasslands of Beringia, with remains having been recovered from Siberia, Alaska, and the Yukon (extending slightly into the adjacent Northwest Territories). Recent genomic evidence suggests that E. lambei and E. ferus may represent a single species [29,76,77,78], although further research is required before this phylogeny can be resolved (see Supplementary Materials, Section 3.4 supplementary text for a discussion on E. ferus in North America).

- 32. Equus (or Haringtonhippus) francisci, Hay, 1915 [76] (Complete Cranium, Mandible and MTIII, TMM 34–2518). This species has been recorded from Irvingtonian to Rancholabrean localities in the Yukon (Canada); Aguascalientes, Estado de Mexico, Jalisco, Puebla, Sonora, and Zacatecas (Mexico); Alaska, Arizona, Florida, Kansas, Nebraska, New Mexico, Texas and Wyoming (USA). It is the oldest name assigned to the stilt-legged group and was first described as being similar to E. tau but with different P3-M1 proportions, which is expected in teeth at different stages of wear and, therefore, probably not a significant taxonomical difference (56). Eisenmann et al. [67] reassigned E. francisci to the genus Amerhippus, as Amerhippus francisci. Heintzman et al. [29] assigned stilt-legged, non-caballine specimens from Gypsum Cave, Natural Trap Cave, the Yukon and elsewhere to their new genus Haringtonhippus under the species Ha. francisci, based upon complete mitochondrial and partial nuclear genomes as well as morphological data and a crown group definition of the genus Equus. Barrón-Ortiz et al. [9] considered Haringtonhippus to be a synonym of Equus and regarded both E. francisci and E. conversidens as distinct taxa based upon morphological criteria.

- 33. Equus fraternus, Leidy, 1860 [79] (Upper Left P2, AMNH 9200). This species has been recorded in Alberta (Canada) and in Florida, Illinois, Mississippi, Nebraska, Pennsylvania, South Carolina and Texas (USA) from Irvintonian to Rancholabrean. Winans [56] considered the dental characteristics used to identify the species to vary with wear and that the specimens used in its diagnosis represented more than one individual, making it uncertain whether to attribute it to one species. Azzaroli [74,80] referred several complete skulls, mandibles and other bones from the southeastern USA to this species.

- 34. Equus pseudaltidens, Hulbert, 1995 [67] (right maxillary with worn DP2, DP3, DP4, M1 and M2 and unerupted P2, P3 and P4 (BEG 31186-35); right and left mandibles with worn i1, di2, dp2, dp3, dp4, m1 and m2 and unerupted p2, p3 and p4 (BEG 31186-36); cranium lacking occiput (BEG 31186-37); right third metacarpal (BEG 31186-3); right and left femora (BEG 31186-2, 34); right and left tibiae (BEG 31186-1, 10); right and left third metatarsals (BEG 31186-4, 7); first phalanx (BEG 31186-24), all thought to belong to the same individual and estimated to have been approximately 3 years old [81]). This species was originally described as Onager altidens by Quinn [81]. The use of Onager instead of Hemionus by Quinn [81] was invalid [67]. Referral of this species to the genus Equus makes it a homonym of Equus altidens, von Reichenau, 1915 [53,67,82]. Therefore, Hulbert [67] proposed the replacement name E. pseudaltidens for E. altidens (Quinn). Also referred to this species are a pair of maxillae (BEG 31186-23) and a right mandible (BEG 31186-22) of an animal approximately 1 year old, and 24 deciduous and permanent upper and lower teeth recovered from the type locality [81]. Equus pseudaltidens is known from the Irvingtonian–Rancholabrean and it has been reported from the Gulf Coastal Plain of Texas [67,81] and possibly from Coleman, Florida [67]. It is a stilt-legged equid with metapodial dimensions that are similar to extant hemionines [67,76]. Compared to other stilt-legged equids discussed here, Equus pseudaltidens is smaller than E. calobatus but larger than both E. francisci and E. cedralensis [67,76,83]. Kurtén and Anderson [84] synonymized E. (Hemionus) pseudaltidens with Equus (Hemionus) hemionus. Winans [85] assigned it to her E. francisci species group. Hulbert [67] considered that E. pseudaltidens and E. francisci were distinct species and hypothesized that they are sister taxa. Azzaroli [74] synonymized E. pseudaltidens (as Onager altidens) with E. semiplicatus. Eisenmann et al. [67] considered E. pseudaltidens distinct from E. semiplicatus and E. francisci and assigned it along with the latter species to Amerhippus. Heintzman et al. [29] considered E. altidens (=E. pseudaltidens) a junior synonym of Haringtonhippus francisci.

- 35. Equus verae, Sher, 1971 [86] (Holotype Mandible with a Full Row of Teeth, GIN 835-123/21, River Bolshaja Chukochya Exp. 21, Kolyma Lowland, Northeast Yakutia). This species is a large-bodied, stout-legged Early Pleistocene (Olyorian)–Rancholabrean species recorded in Northeastern Siberia (Russia) and the Yukon (Canada). E. verae is much larger than the E. stenonis species and similarities in the teeth and the size of limb bones with E. suessenbornensis, suggesting a subspecies position for E. verae as well as for E. coliemensis (see below). Eisenmann [87,88] suggested that E. verae may belong to the subgenus Sussemionus, but this has not been substantiated by other authors.

- 36. Equus occidentalis, Leidy, 1865 [89] (Lectotype Left P3, VPM 9129). It is a Rancholabrean NALMA horse with records in Mexico (i.e., Baja California and Sonora) and the USA (i.e., Arizona, California, Nevada, New Mexico and Oregon). Leidy [89] named E. occidentalis from two upper premolars and one lower molar from two widely separated geographic localities but did not designate a holotype. Gidley [73] selected a left P3 from Tuolumne County, California, as the lectotype. Merriam [90] referred to E. occidentalis thousands of bones of a large and stout-limbed equid recovered from Rancho La Brea. Savage [91] and Miller [92] believed that the equid from Rancho La Brea, identified as E. occidentalis, did not conform to the lectotype designated by Gidley [73], but neither of these authors proposed a new name. Azzaroli [74] decided to retain the name E. occidentalis sensu Merriam [90] and selected the skull figured by Merriam [90] as his lectotype. However, since Gidley [73] had already designated a lectotype for the species, according to ICZN Article 74, no subsequent lectotype designations can be made. Brown et al. [93] concluded that some of Leidy’s original fossils of E. occidentalis (exclusive of the Tuolumne County tooth) most likely come from the McKittrick asphalt deposits; this locality was not named by Leidy [89], because the town of McKittrick, California, was not named until 1900. These authors also confirmed that many specimens from the original type series of E. occidentalis closely resemble the large Pleistocene horses from McKittrick and Rancho La Brea [93]. Barrón-Ortiz et al. [94] recognized the presence of this species outside of the North American Western Interior during the Late Pleistocene. Barrón-Ortiz et al. [9] recognized it as a valid species closely related to E. neogeus.

- 37. Equus cedralensis, Alberdi et al., 2014 [83] (fragment of a mandibular ramus formed by two specimens: one p2-m3 right row (DP-2675 I-2 15) and a second fragment of the symphysis with the anterior dentition (DP-2674 I-2 8), articulated together from Rancho La Amapola, Cedral, San Luis Potosí, Mexico, and stored at the Paleontological Collection (DP-INAH) of the Laboratorio de Arqueozoología “M. en C. Ticul Álvarez Solórzano” Subdirección de Laboratorios y Apoyo Académico, INAH in Mexico City). This species is primarily known from the Rancholabrean of Mexico (i.e., Aguascalientes, Chihuahua, Estado de Mexico, Michoacán, Puebla and San Luis Potosí). Equus cedralensis is an equid with a small body mass (estimated mean mass of 138 kg) [83,95]. Equus cedralensis was diagnosed as stout-legged, but a recent analysis placed it within stilt-legged horses and with its dental morphology being similar to Ha. francisci. Jimenez-Hidalgo and Diaz-Sibaja [96] considered it a junior synonym of Ha. francisci. Equus cedralensis differs from the holotype of Ha. francisci, as it is smaller in size and the lower first and second incisors possess enamel cups.

- 38. Equus mexicanus, Hibbard, 1955 [65] (cranium lacking the LM3 (No. 48 (HV-3)) from Tajo de Tequixquiac, Estado de México, Mexico, and stored at the Museo Nacional de Historia Natural; the specimen is cataloged as IGM4009). This species is known from the Rancholabrean of Mexico (i.e., Aguascalientes, Chiapas, Estado de Mexico, Jalisco, Michoacán, Oaxaca, Puebla, San Luis Potosi and Zacatecas) and the USA (i.e., California, Oregon and Texas). Equus mexicanus is a large body sized species (estimated mean mass of 458 kg) [83,95]. Winans [85] placed E. mexicanus in her Equus laurentius species group, but as with other species groups in this study, this was not a strict synonymy. Azzaroli [74] recognized E. mexicanus as a valid taxon, noting that previous investigations had proposed synonymy with and tentatively identified as E. pacificus but rejecting this, since the latter species was initially based upon a single tooth. Barrón-Ortiz [97] assigned specimens identified as E. mexicanus to E. ferus scotti. Barrón-Ortiz et al. [94] assigned specimens identified as E. mexicanus to E. ferus. Barrón-Ortiz et al. [9] recognized E. mexicanus as a valid taxon distinct from E. ferus.

3.2. South America

Two genera, Equus and Hippidion, inhabited the South American continent with records from the Late Pliocene to the Late Pleistocene [98,99,100]. Hippidion is an endemic genus of South American horses characterized mostly by the retraction of the nasal notch, a particular tooth morphology (considered more primitive than Equus and comparable with Pliohippus) and the robustness and shortness of its limb bones [98]. The genus is, at present, represented by three species: Hippidion saldiasi, Hippidion devillei and Hippidion principale [98]. On the other hand, the South American Equus is represented by a single species, E. neogeus, with caballine affinities and metapodial variation corresponding to an intraspecific characteristic representing a smooth cline [9,99,100].

- 1. Equus neogeus, Lund, 1840 [101] (MTIII, 866 Zoologisk Museum). This is a Middle–Late Pleistocene species (Ensenandan and Lujanian SALMA) and the only representative of the genus in the South American continent [9,98,99,100]. Most records are from the Late Pleistocene, but its earliest appearance is recorded in the Middle Pleistocene in Tarija, Bolivia, dated at approximately 1.0–0.8 Ma [102,103]. It has a wide geographic range distribution, encompassing all of South America, except for the Amazon basin and latitudes below 40° [100]. The species probably became extinct sometime during the Late Pleistocene–Holocene transition as suggested by the youngest direct radiocarbon date of 11,700 BP (Río Quequén Salado, Argentina [104]).

- 2. Hippidion saldiasi, Roth, 1899 [105] (p2, Museo Nacional de La Plata). This is a Late Pleistocene species, dated between 12,000 and 10,000 years BP, mostly known from Argentinian and Chilean Patagonia, with records in Central Chile and the Atacama Desert [98,106]. The last records for the species were radiocarbon dated between 12,110 and 9870 BP in Southern Patagonia (Cerro Bombero, Argentina [107]) and Cueva Lago Sofía, Chile [108].

- 3. Hippidion principale, Lund, 1846 [109] (M2, Peter W. Lund Collection, ZMK). This is a Late Pleistocene species (Lujanian SALMA), with records in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil and Uruguay [98]. This species represents the largest Hippidion. There are few radiocarbon-dated records for this species, with the youngest situated at approximately 16,130 BP (Arroyo La Carolina, Argentina) [104]; however, remains found in archaeological contexts dating close to 13,200 BP in Tagua, Central Chile [110], suggest a later presence for this taxon.

- 4. Hippidion devillei, Gervais, 1855 [111] (P2–P3 Row and Fragmented Astragalus, IPMNHN). This species has been reported in Uquia (Argentina, Late Pliocene–Early Pleistocene), Tarija (Bolivia) and Buenos Aires (Argentina) from the Middle Pleistocene (Ensenadan SALMA) to the Late Pleistocene (Lujanian SALMA) and in Brazil [98]. This taxon has been directly radiocarbon dated only from cave contexts in the high Andes of Peru, with the youngest record of 12,860 BP [112,113].

4. Systematics of the Equinae since 5.3 Ma in Eurasia and Africa

4.1. Eastern and Central Asia (China, Mongolia, Russia, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Tajikistan)

The fossil record of the three-toed horses from Eastern Asia includes four different genera (i.e., Plesiohipparion, Cremohipparion, Proboscidipparion and Baryhipparion) with seven identified species. As for the Indian Subcontinent, Europe and Africa (see below), the Miocene–Pliocene boundary marks the extinction of the genera Hippotherium, Hipparion s.s., Sivalhippus and Shanxihippus [8]. On the other hand, Sun and Deng [114] argued that the Equus Datum in China is represented by the simultaneous appearance of five stenonine Equus species: E. eisenmannae, E. sanmeniensis, E. huanghoensis, E. qyingingensis and E. yunnanensis. Subsequently, Sun et al. [115] indicated the E. qyingingensis FAD at 2.1 Ma.

- 1. Plesiohipparion houfenense, Teilhard de Chardin and Young, 1931 [116] (MN13–MN15; 6–3.55Ma). The lectotype RV 31031 includes the right p3–m3 from Jingle, Shanxi. The earliest P. houfenense first occurs in the Late Miocene Khunuk Formation, Kholobolchi Nor, Mongolia [8,117,118,119] and the Late Miocene/Early Pliocene Goazhuan Formation of the Yushe Basin (5.8–4.2 Ma) [8,120]. It also occurs into the Pliocene of China.

- 2. Proboscidipparion pater, Matsumoto, 1927 [121] (MN14–MN15; 5–3.5 Ma). The lectotype THP14321 is a skull with a mandible estimated to be 4–3.55 Ma [122]. This species is reported from the Yushe Basin (China), and it may be the original source for the evolution of the Pliocene European species Proboscidipparion crassum and Proboscidipparion heintzi.

- 3. Plesiohipparion huangheense, Qiu et al., 1987 [122] (MN15; 5.0–3.55). The lectotype THP 10097 is a lower jaw fragment, including the cheek teeth, from the Yushe Basin [122]. It is a Chinese species reported from Inner Mongolia at 3.9 Ma [7,119,122] and more broadly from the MN15 of China and India [8]. Ultimately, Pl. aff. huangheense has been reported from the Early Pleistocene in Gulyazi, Turkey [123].

- 4. Cremohipparion licenti, Qiu et al., 1987 [122] (MN15, circa 4.0 Ma). The holotype is THP20764, an incomplete cranium from the Yushe Basin [122]. This distinctly Chinese species is the latest occurring member of the genus Cremohipparion and is reported from the Yushe Basin [8].

- 5. Baryhipparion insperatum, Qiu et al., 1987 [122] (MN16–MNQ17; 3.55–1.8 Ma). The holotype is THP19009, an incomplete cranium with the mandible from the Yushe Basin [122]. It is reported that this species is from the Pliocene in China.

- 6. Plesiohipparion shanxiense, Bernor et al., 2015 [124] (MNQ17; 2.5–1.8 Ma). The holotype is F:AM111820, a complete skull with the mandible [124]. This species, previously recognized as Plesiohipparion cf. P. houfenense [117], is the largest and, at the same, the time youngest member of the genus in Eastern Eurasia. It is believed to be 2.0 Ma in age [124]. It may represent the last evolutionary stage of the genus Plesiohipparion in China. The absence of the POF suggest an evolutionary relationship with Pl. houfenense.

- 7. Proboscidipparion sinense, Sefve, 1927 [125] (MN17-MQ1; 2.5–1.0 Ma). The holotype is PMU M3925, a complete cranium from Henan Province, China. Proboscidipparion sinense occurs later in the record and is approximately one-seventh larger than P. pater. Proboscidipparion sinense is the latest occurring hipparion in China extending its range up to 1.0 Ma [126].

- 8. Equus eisenmannae, Qiu et al., 2004 [127] (2.55–1.86 Ma). The holotype is IVPP V13552, a complete cranium with and the mandible from Longdan [127]. It is a large-sized horse, mostly known from the Early Pleistocene locality of Longdan (China), similar in size to E. livenzovensis (see below), and the primitive features of the cranial morphology suggest a close evolutionary relationship with E. simplicidens [10,13]. At the present time, its evolutionary linkage with other Chinese Equus is not known.

- 9. Equus sanmeniensis, Teilhard de Chardin and Piveteau, 1930 [128] (2.5–0.8 Ma). The lectotype is NIH 002 (Paris), a complete cranium with the mandible from Nihewan, Hebei Province. It is a large-sized, Early Pleistocene species from North and northwest China, Siberia (Aldan River, Bajakal Lake area), Kazakhstan and Tajikistan [114,129]. Sun and Deng [114] suggested a morphological similarity between E. sanmeniensis and E. simplicidens, although diversified from E. stenonis. This evolutionary hypothesis has also been supported by Cirilli et al. [10,13] through morphometric studies on crania. Equus sanmeniensis has been reported from the Early to Middle Pleistocene [114,130].

- 10. Equus huanghoensis, Chow and Liu, 1959 [131] (2.5–1.7 Ma). The holotype is IVPP V2385–2389, with three upper premolars and two molars from Huanghe, Shanxi (Sun and Deng, 2019). It is a large-sized, Early Pleistocene species from the localities of Nihewan (Hebei), Linyi (Shanxi), Sanmenxia Pinglu (Shanxi), Xunyi (Shaanxi) and Nanjing (Jiangsu). Sun and Deng [114] supported the hypothesis provided by Deng and Xue [130] that E. huanghoensis is a stenonid horse, considering the Nihewan sample as one of the Equus species with the largest palatal length with E. eisenmannae. The morphometric analyses of Cirilli et al. [10,13] show a primitive morphology of the cranium, similar to E. simplicidens and distinct from E. stenonis. Ao et al. [132] indicated the age of 1.7 Ma as the youngest record of this species in China.

- 11. Equus yunnanensis, Colbert, 1940 [133] (2.5–0.01 Ma). The lectotype is IVPP V 4250.1, an almost complete but deformed cranium. It is a medium-sized, Early Pleistocene species from the Chinese localities of Yuanmou (Yunnan), Liucheng (Guangxi), Jianshi and Enshi (Hubei), Hanzhong (Shaanxi) and Huili (Sichuan) and from Irrawaddy in Myanmar. The species was initially described by Colbert [133] on isolated cheek teeth, while better knowledge of this species came with the new discoveries from the Yuanmou locality. Deng and Xue [130] proposed a close evolutionary relationship with E. wangi, whereas Sun and Deng [114] suggested a close evolutionary relationship with E. teilhardi, suggesting that these species are distinct from all other Chinese stenonid horses [114].

- 12. Equus teilhardi, Eisenmann, 1975 [134] (2.0–1.0 Ma). The holotype is NIH001, an incomplete mandible. It is a medium-sized, Early Pleistocene species from northwestern and North China. Sun et al. [135] proposed a close evolutionary relationship between E. teilhardi and E. yunnanensis, later supported by the cladistic analysis of Sun and Deng [114].

- 13. Equus qyingyangensis, Deng and Xue, 1999 [130] (2.1–1.2 Ma). The holotype is NWUV 1128, an incomplete cranium. It is a medium-sized, Early Pleistocene species from northwestern and North China. Eisenmann and Deng [136] recognized some close anatomical features between E. simplicidens and E. qyingyangensis, suggesting a close evolutionary relationship between these two species. The latest phylogenetic results of Sun and Deng [114] and Cirilli et al. [10] support this last hypothesis. A new E. qyingyangensis sample has recently been described from Jinyuan Cave [115], with an FAD of 2.1 Ma.

- 14. Equus wangi, Deng and Xue, 1999 [130] (2.0–ca. 1.0 Ma). The holotype is NWUV 1170, a complete upper and lower cheek teeth rows from Gansu Province, Early Pleistocene [130]. Sun and Deng [114] reported a large size for E. wangi, similar to E. eisenmanne, E. sanmeniensis and E. huanghoensis. The phylogenetic position of E. wangi is not well defined, although Sun and Deng [114] highlighted a possible closer relationship with E. eisenmannae than any other stenonine Equus.

- 15. Equus pamirensis, Sharapov, 1986 [137] (Early Pleistocene). The holotype is IZIP 1-438 (Institute of Zoology and Parasitology, Uzbekistan), a complete upper tooth row from Kuruksai [137], approximately 2 Ma (MN17), possibly earlier. It is a large species of stenonine horse described from the Kuruksai, 18 km NE of Baldzuan, Tajikistan, in the Kuruksai River valley in the Afghan–Tajik Depression [138]. The site has been correlated to the middle Villafranchian. The taxonomy of this horse is contentious [138], with it being referred to variously as Equus (Allohippus) aff. sivalensis [137] and E. stenonis bactrianus [139]. We currently regard this as a distinct species.

- 16. Central Asian Small Equus sp. from Kuruksai [138] (Early Pleistocene). This is a small species of horse that co-occurs with the larger E. pamirensis at Kuruksai. Metrically, the metapodials fall within the range of variation of E. stehlini [138]. Similar small horse remains have also been found in the Early–Middle Pleistocene Lakhuti 1 locality in the Afghan–Tajik Depression [138].

- 17. Equus (Hemionus) nalaikhaensis, Kuznetsova and Zhegallo, 1996 [140]. This species was found in the late Early Pleistocene and early Middle Pleistocene (approximately 1 my, Jaramillo paleomagnetic episode) in Mongolia. The lectotype PIN 3747/500 is represented by the incomplete skull of an old male from Nalajkha [141].

- 18. Equus coliemensis, Lazarev, 1980 [142]. The holotype is a skull with very worn teeth (col. IA 1741). The type locality is the river Bolshaja Chukochya, Kolyma lowland, northeast Yakutia, Siberia, Russia. It is reported from the late Early Pleistocene in northeastern Siberia (Russia). Recently, Eisenmann [87] included E. coliemensis in the subgenus Sussemonius.

- 19. Equus lenensis, Rusanov, 1968 [143]. The holotype skull comes from the Lena River delta (GIN Yakutia col. 33). The type locality is the river Bolshaja Chukochya, Kolyma lowland, northeast Yakutia, Siberia (Russia). It is reported from the Middle Pleistocene from northeastern Siberia (Russia). Lazarev [144] considered E. lenensis to be close to the North American E. lambei, even larger and more heavily built than the latter. It is also known from the Middle Pleistocene in Yakutia Equus orientalis (Equus caballus/ferus orientalis) and Equus nordostensis (Equus ferus/caballus nordostensis) [143,144,145]. Equus nordostensis is characterized by a large size based on the skull, with low plication of the “marks” of the upper teeth and a long protocone [144]. According to Kuzmina [129], it is junior synonym of E. mosbachensis. Equus orientalis has a large skull and a long snout with an elongated teeth row, flat protocone and rare plication of the upper teeth [144].

- 20. Equus beijingensis, Liu, 1963 [146] (late Middle Pleistocene). The holotype is V2573-2574, a palate and jaw from Zhoukoudian, China [146,147]. It is a Chinese caballine horse recovered mostly form locality 21 of Zhoukoudian. Unfortunately, the species is not well represented, although Forsten [147] indicated a similar size with E. sanmeniensis. Liu [146] also indicated E. sanmeniensis as the possible ancestor for E. beijingensis; nevertheless, this hypothesis was discarded by Fortsen [147] and Deng and Xue [130], who identified E. beijingensis as a caballine horse, characterized by a U-shaped linguaflexid. Its evolutionary position is not well defined, although Forsten [147] and Deng and Xue [130] proposed that E. beijingensis is a relative of European E. ferus (their E. mosbachensis) or of a North Americam caballine horse [130].

- 21. Equus valeriani, Gromova, 1946 [148] (Late Middle–Late Pleistocene). The hypodigm includes upper and lower cheek teeth, figured in Eisenmann et al. [149]. It is an enigmatic taxon, described by Gromova [148], from Samarkand, Uzbekistan. According to Gromova [148] and Eisenmann et al. [149], it shows a stenonine metaconid-metastylid in the lower cheek teeth but with a long protocone in the upper cheek teeth. Its possible occurrence has also been proposed in Syrie (Kéberien Géométrique d’Umm el Tlel), although this identification still remains uncertain [149].

- 22. Equus dalianensis, Zhow et al., 1985 [150] (Late Pleistocene). The holotype is V821966, an incomplete mandible preserving two lower cheek teeth rows. It is a Chinese caballine horse described from Gulongshan Cave, Liaoning. Forsten [147] demonstrated close morphological and morphometrical similarities with E. ferus gemanicus, E. ferus orientalis and E. ferus chosaricus, suggesting that they all represent individual populations of a single widespread species, E. ferus. Deng and Xue [130] suggested a common origin for E. dalianensis and E. przewalskii, with no ancestor-descendant relationships between them. Nevertheless, a recent genomic analysis by Yuan et al. [151] revealed that E. dalianensis is a separate clade of caballine horses, distinct from E. przewalskii.

- 23. Equus ovodovi, Eisenmann and Vasiliev, 2011 [152] (0.04–0.01 Ma). The holotype is IAES 21, a fragmentary palate from Proskuriakova Cave [152]. It was described in the Late Pleistocene site of Proskuriakova Cave (Khakassia, southwestern Siberia, Russia). It was first considered a species related to E. hydruntinus and modern hemiones, although the genomic analyses by Orlando et al. [153] suggest a relationship with wild asses, representing a new separated fossil clade with no extant relatives [150]. For this reason, Orlando et al. [153] and Eisenmann and Vasiliev [152] included this species in the subgenus Sussemionus. Molecular studies suggest that E. ovodovi is a sister to extant zebras and is nested within the clade that includes both extant zebra and asses [154]. Equus ovodovi has been recognized in the Late Pleistocene of southern and eastern Russia and more recently in China [152,154,155].

- 24. Equus hemionus, Pallas, 1774 [156] (0.0 Ma). Pallas [156] did not refer to any holotype or lectotype but gave a detailed description of the anatomical features of the species, associated with an illustration of an animal located near Lake Torej-Nur, Transbaikal area [156] (V.19, pp. 394–417, Pl. VII). Equus hemionus is known as the Asiatic wild ass, distributed in China, India, Iran, Mongolia and Turkmenistan. Historically, it has also been reported in Afghanistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Tajikistan, Turkey and Ukraine. Four different subspecies are identified, mostly describing the present areal distribution: E. hemionus hemionus (Mongolia), E. hemionus khur (India), E. hemionus kulan (Turkmenistan) and E. hemionus onager (Iran). Another extinct subspecies was recognized in Syria, E. hemionus hemippus. The fossil record is not well studied, but crania and mandibles of the species have been reported from Narmada Valley in Central India [157], the Indian state of Gujarat [158], and the Son Valley in Northern India [159]. This species is distinguished from E. namadicus by its smaller size and smaller protocones on the premolars. Radiocarbon dates from these deposits suggest that this species entered South Asia during the last glacial period, most likely from West Asia [160,161]. The most recent genetic analyses suggest that the onager and kiang populations diverged evolutionarily ca. 0.4–0.2 Ma [28].

- 25. Equus kiang, Moorcroft, 1841 [162] (0.0 Ma). Moorcroft [162] did not designate any holotype or lectotype but provided a general description of the species [162]. Equus kiang is known as the Tibetan ass, with a distribution in China, Pakistan, India, Nepal and, possibly, Bhutan. Three subspecies have been identified, E. kiang kiang, E. kiang holdereri and E. kiang polyodont, with different authors pointing out their subspecific statuses [162,163,164,165]. At the present time, no paleontological information is available for E. kiang. Jonsson et al. [28] distinguished E. kiang from E. hemionus as a valid taxon. The most recent morphological cladistic analysis found E. kiang and E. hemionus to be stenonine horses [10].

- 26. Equus przewalskii, Poliakov, 1881 [166] (~0.1–0.0 Ma). The holotype, a skull (number 512) and skin (number 1523), are found in the collection of the Laboratory of Evolutionary Morphology, Moscow (museum exposition), originally obtained by N. M. Polyakov in Central Asia, southern Dzhungaria, in 1878 [129]. For a complete description of the species see Groves [167] and Grubb and Groves [168]. It is an extant species of caballine horse that is found in small geographic areas of Central Asia, although, historically, it once ranged from Eastern Europe to eastern Russia [169]. In China, E. przewalskii is common in the Late Pleistocene (~0.1–0.012 Ma) sites in the northern and central regions of the country, but it is absent in the Holocene, except in northwestern China [170]. It shows close morphological similarities with Equus ferus (see below), and both are members of caballine horses [10,28,153]. While genomic analyses have shown that the Przewalski’s horses are the descendants of the first domesticated horses from the Botai culture in Central Asia (Kazakhstan) around 5.5 ka [171,172], subsequent morphological studies have shown that Botai horses are not domestic horses but harvested wild Prezwalski’s horses [173].

4.2. Indian Subcontinent

The Siwalik Group and co-eval sediments of the Himalayan Foreland Basin preserve an exceptional record of hipparionine and equine horses. The earliest lineage, Cormohipparion, appears in the record at approximately 10.8 Ma. The diverse indigenous Sivalhippus lineage ranges from 10.4 to 6.8 Ma, “Hipparion” from 10 to 9.6 Ma and Cremohipparion from 8.8 to 7.2 Ma [174]. Across the Mio–Pliocene boundary, a turnover in hipparion taxa seems to have taken place, with the older lineages being replaced in the Late Pliocene by Plesiohipparion and Eurygnathohippus along with a distinct but poorly known species “Hippotherium” antelopinum [119,175]. These Late Pliocene hipparionines are replaced by stenonine equids represented by Equus sivalensis and a small species of ass-like Equus in the Early Pleistocene [176]. By the Middle Pleistocene, a third species of large stenonine horse, Equus namadicus, is common in peninsular India deposits; this species went extinct in the Late Pleistocene [177]. Equus hemionus doesn’t appear in the record until ~0.03 Ma [177], and Equus caballus is found in Holocene archaeological sites [178].

- 1. “Hippotherium” antelopinum, Falconer and Cautley, 1849 [179] (3.6–2.6 Ma). The lectotype is NHMUK PV M.2647, a subadult right maxilla fragment with P2-M3. It is a species of hipparionine horse from the late Pliocene age deposits between the rivers Yamuna and Sutlej in India. This taxon has been the subject of much nomenclatural confusion. Lydekker named the lectotype and along with the hypodigm, placed it within the genus Hipparion. Later authors [180,181,182] have referred Miocene hipparionine material collected on the Potwar Plateau in Pakistan to this táxon and reassigned the species to the genus Cremohipparion. However, given that the hypodigm of “Hippotherium” antelopinum comes from the Late Pliocene and does not preserve any apomorphies of Cremohipparion; we refer to the late Pliocene specimens as “Hippotherium” antelopinum, separate from the Potwar Plateau specimens from the Dhok Pathan Formation, which can still be taxonomically referred to as Cremohipparion, but a formal description of the species with a new type of specimen is required. A more comprehensive study currently in preparation will attempt to resolve this issue

- 2. Plesiohipparion huangheense, Qiu et al., 1987 [122] (3.6–2.6 Ma). Jukar, et al. [119] identified NHMUK PV OR 15790, a mandibular fragment with p4-m1, originally classified as “Hippotherium” antelopinum, as P. huangheense from the Late Pliocene of the Siwalik Hills.

- 3. Eurygnathohippus sp. (3.6–2.6 Ma). Four mandibular cheek teeth from the Late Pliocene of the Siwaliks from the Potwar Plateau in Pakistan and the Siwalik Hills in India were identified by Jukar et al. [175] as Eurygnathohippus sp. These specimens all bear the characteristic single pli-caballinid and ectostylid.

- 4. Equus sivalensis, Falconer and Cautley, 1849 [179] (2.6–0.6 Ma). The lectotype is NHMUK PV M.16160, an incomplete cranium from the Siwaliks [183]. It is a large species of stenonine horse found in the Siwaliks of the Indian Subcontinent, ranging from the Potwar Plateau in the west to the Nepal Siwaliks in the east. The exact temporal distribution is unknown; however, based on paleomagnetic dating of the Pinjor Formation where the species was found, it likely ranges in age from 2.6 to 0.6 Ma [176,184]. However, some potentially older occurrences from just below the Gauss–Matuyama boundary (>2.6 Ma) have also been reported [185,186].

- 5. Equus sp. (~2.2–1.2 Ma). This is small species of Equus with smaller slender metapodials has been reported from the Pinjor Formation of the Upper Siwaliks. This species has been referred to as Equus sivalensis minor [187], Equus sp. A [188] or Equus cf. E. sivalensis [189]. A set of postcranial remains, including metapodials, astragali and phalanges, which were formerly tentatively referred to as “Hippotherium” antelopinum, are now believed to belong to this small species of Equus [138,184]. Based on specimens collected from the Mangla–Samwal Anticline and the Pabbi Hills in Pakistan, this species likely ranges in age from ~2.2 to 1.2 Ma [176]. Geographically, it ranges from the Pabbi Hills to the river Yamuna in the east.

- 6. Equus namadicus, Falconer and Cautley, 1849 [179] (~0.5–0.015 Ma). The lectotype is NHMUK PV M.2683, an incomplete cranium from the Siwaliks [183]. It is a large-sized stenonine horse from the Middle and Late Pleistocene of the Indian Subcontinent. The stratigraphic range includes the Middle Pleistocene Surajkund Formation in Central India [190] and Late Pleistocene deposits throughout peninsular India [177]. However, Lydekker [191] reported some specimens from the uppermost Upper Siwaliks, which might suggest that the species extends back to the early Middle Pleistocene.

4.3. Europe

As in Eastern and Central Asia, the Mio–Pliocene boundary represents a relevant turnover of three-toed horses in Europe, with the extinction of the genera Hippotherium and Hipparion s.s. The Pliocene and Pleistocene are characterized by the persistence of Cremohipparion, and the dispersion of Proboscidipparion and Plesiohipparion [7], represented by five species. The Equus Datum is represented by the oldest species, Equus livenzovensis, at ca. 2.6 Ma in Russia, Italy, France and Spain [176], which led to the Equus stenonis’ evolution and to the radiation of the African fossil species [10,13,184,192]. At the present time, we recognize 13 species in the genus Equus during the Pleistocene.

- 1. Plesiohipparion longipes, Gromova, 1952 [193] (7–3.0 Ma). The holotype is PIN2413/5030, a complete mt3 from Pavlodar [193]. It has been identified from Pavlodar (Kazhakstan), Akkasdagi and Calta (Turkey) [194] and Baynunah (UAE) [8,195]. In all cases, Pl. longipes was recognized by its extreme length dimensions of mc3s and mt3s. None of these attributions of Plesiohipparion display the characteristics of extremely angled and pointed metaconids and metastylids of Pl. houfenense, Pl. huangheense, Pl. rocinantis or Pl. shanxiense. If all these taxa are referable to Plesiohipparion, the chronologic range would be 7 Ma to the Early Pleistocene and the geographic range being from China to Spain.

- 2. “Cremohipparion” fissurae, Crusafont and Sondaar, 1971 [196] (MN14-15). The holotype is an mt3 from Layna, Spain, figured in Crusafont and Sondaar [196] (Pl. 1). It was originally described as “Hipparion” fissurae. The species is recorded from the MN15 Pliocene localities in Spain [197] and more recently from the MN14 of Puerto de la Cadena [198]. The most recent analyses provided by Cirilli et al. [192] suggest an attribution to the genus Cremohipparion, yielding this species as the possible last representative of the genus in Europe. Its evolutionary framework is not yet defined.

- 3. Proboscidipparion crassum, Gervais, 1859 [199] (ca. 4.0–2.7 Ma; MN14-16). Deperet [200] described and figured the sample from Roussillon, France, without assigning a holotype or lectotype. The sample figured by Deperet [200] (Pl. V, Figures 6–10; Pl. VI) represents the hypodigm for the species. The sample is a small-sized equid with remarkable similarities with Pr. heintzi [192,194]. No complete crania are known from this species, whereas it is well documented by isolated upper and lower cheek teeth and postcranial elements. Bernor and Sen [194] showed that Pr. crassum also has a very short mc3, whereas Cirilli et al. [192] gave substantial indications in cranial and postcranial elements for its attribution to the genus Proboscidipparion. This species is mostly known from the Pliocene of France (Perpignan, Montpellier) but also from Dorkovo (Bulgaria) and Reg Crag (England) [197,201,202].

- 4. Proboscidipparion heintzi, Eisenmann and Sondaar, 1998 [203] (MN15). The holotype is MNHN.F.ACA49A, a complete mc3 from Calta, Turkey [203]. It was originally identified and described “Hipparion” heintzi [203], whereas Bernor and Sen [194] restudied and allocated this taxon to Pr. heintzi, recognizing the similarity of the Calta juvenile skull MNHN.F.ACA336 to Chinese Pr. pater in the retracted and anteriorly broadly open nasal aperture accompanied by very elongate anterostyle of dP2 [190]. It has only been reported from the locality of Calta.

- 5. Plesiohipparion rocinantis, Hernández-Pacheco, 1921 [204] (3.0–2.58 Ma). The lectotype is a p3/4 figured in Alberdi [205] (Pl. 6, Figure 4). It is the largest three-toed horse from Europe. Qiu et al. [122], followed by Bernor et al. [124,206] and Bernor and Sun [207], recognized this species as being a member of the Plesiohipparion clade by cranial and postcranial morphological features. Plesiohipparion rocinantis is reported between 3.0 and 2.6 Ma [208,209] from La Puebla de Almoradier, Las Higuerelas and Villaroya (Spain); Roca-Neyra (France); Red Crag (England); Kvabebi (Georgia). This species may include “Hipparion” moriturum from Ercsi (Hungary) and the sample from Sèsklo (Greece) previously ascribed to Plesiohipparion cf. Pl. shanxiense [210]. It represents the last occurrence of Plesiohipparion in Europe at the Plio–Pleistocene transition [8,192].

Rook et al. [211] reported the occurrence of “Hipparion” sp. from the Early Pleistocene locality of Montopoli, Italy (2.6 Ma). The “Hipparion” sp. from Montopoli is represented by a single incomplete upper cheek tooth that, however, shows some morphological features distinct from the first Equus, E. livenzovensis occurring in the same locality [211]. Together with Villarroya, Roca-Neyra, Sèsklo, Guliazy and Kvabebi, the Montopoli specimen represents one of the last occurrences of three-toed horses in Europe and may, in fact, be a small species of Cremohipparion.

- 6. Equus livenzovensis, Bajgusheva, 1978 [212] (2.6–2.0 Ma). The holotype is POMK L-4, a fragmentary skull from Liventsovka [212] in the Early Pleistocene. The species represents the Equus Datum in Western Eurasia, Early Pleistocene localities dated at the Plio–Pleistocene boundary (2.58 Ma) such as Liventsovka (Russia), Montopoli (Italy) and El Rincón–1 (Spain) [184,212,213,214,215,216,217,218,219]. Recent research [214,216,220] suggests the occurrence of E. livenzovensis in Eastern European localities, dated between 2.58 and 2.0 Ma. The species shows the typical stenonine morphology, even though it is a large-sized horse.

- 7. Equus major, Delafond and Depéret, 1893 [221] (?2.6–1.9 Ma). The hypodigm is represented by a P2-M1 and a 1ph3 figured by Delafond and Depéret [221] from Chagny, France. It is poorly represented in the Early Pleistocene of Europe, being represented by few remains and localities. It was described by an incomplete upper cheek tooth row and postcranial elements from the Early Pleistocene locality of Chagny (Central France). Following the ICZN guidelines, Alberdi et al. [216] established that E. major has priority over Equus robustus Pomel, 1853 [222]; Equus stenonis race major Boule, 1891 [223]; Equus bressanus Viret, 1954 [224]; Equus major euxinicus Samson, 1975 [225]. Equus major has been reported from the European sites of Senèze, Chagny, Pardines and Le Coupet (France); Tegelen (the Netherlands); East Reunion and Norfolk (England) [216], and, as reported by Forsten [214], it may also be present at Liventsovka (Russia). It is a large-sized monodactyl horse, the largest species of the European Early Pleistocene.

- 8. Equus stenonis, Cocchi, 1867 [226] (2.45–ca. 1.6 Ma). The holotype is IGF560, a complete cranium from the Upper Valdarno Basin, Italy [13]. It was the most widespread Equus species during the Early Pleistocene (MNQ17 and MNQ18). In the last century, E. stenonis samples were identified under several subspecies as E. stenonis vireti, E. stenonis senezensis, E. stenonis stenonis, E. stenonis granatensis, E. stenonis guthi, E. stenonis mygdoniensis, E. stenonis anguinus, E. stenonis pueblensis and E. stenonis olivolanus. Recently, Cirilli et al. [13] reevaluated these subspecies, considering most of them to be ecomorphotypes of the same species, resulting in recognizing that E. stenonis is a monotypic, polymorphic species. At the present time, the species is reported as having occurred from Georgia to Spain in the circum-Mediterranean area as well as the Levant.

- 9. Equus senezensis, Prat, 1964 [227] (2.2–2.0 Ma). The lectotype includes a left P2-M3 and two mc3s, figured in Prat [227] (Pl.1 Figure C; Pl.2 Figure D,E). It is a medium-sized horse, distributed in France and Italy. Earlier referred to as E. stenonis senezensis [227], it has been recognized as a different species by Alberdi et al. [216] and Cirilli et al. [13]. It is morphologically similar to the European E. stenonis but with a reduced size. It is reported from the type locality of Senèze and possibly from Italy between 2.2 and 2.1 [228,229].

- 10. Equus stehlini, Azzaroli, 1964 [230] (1.9–1.78 Ma). The holotype is IGF563, an incomplete cranium from the Upper Valdarno Basin. It is the smallest Early Pleistocene Equus species. Over the last decades, it was considered both either a species or a subspecies of E. senezensis Azzaroli [216,230]. Cirilli [229] found that it can be considered a different Early Pleistocene species that probably evolved from E. senezensis. At the present time, E. stehlini is known only from Italy [228,229].

- 11. Equus altidens, von Reichenau, 1915 [82] (1.8–0.78 Ma). The lectotype is a right p2 figured in von Reichenau [82] (Pl. 6, Figure 17) from Sussenborn, Germany. It is a medium-sized horse, intermediate in size between E. stehlini and E. stenonis, occurring in Western Eurasia in the late Early to early Middle Pleistocene. Originally described from the Middle Pleistocene in Süssenborn [82], over the last decades its chronologic range was extended to the late Early Pleistocene, representing the most widespread species after 1.8 Ma until the Middle Pleistocene [231,232]. Recently, Bernor et al. [14] reported its first occurrence in Dmanisi (Georgia, 1.85–1.76 Ma), supporting the hypothesis of a dispersion of this species from east to west, being part of a faunal turnover that included several other mammalian species during this time frame [14,233,234]. It was also identified in Moldova (Tiraspol, layer 5) [129]. Several populations of E. altidens have been identified as different subspecies (i.e., E. altidens altidens and E. altidens granatensis). Nevertheless, within the nomen, E. altidens may also be included in other European taxa such as Equus marxi von Reichenau, 1915 [82]; Equus hipparionoides Vekua, 1962 [235]; E. stenonis mygdoniensis Koufos, 1992 [236]; Equus granatensis Eisenmann, 1995 [13,216,232,233,237,238]. Its origin remains controversial. Guerrero Alba and Palmqvist [239] proposed a possible African origin, claiming it to be part of the E. numidicus–E. tabeti evolutionary lineage. This latter hypothesis was also reported by Belmaker [240]. Eisenmann [87] included E. altidens in the new subgenus Sussemionus, with other Early and Middle Pleistocene species. More recently, Bernor et al. [14] proposed a new evolutionary hypothesis, considering that E. altidens originated in Western Asia and is potentially related to living E. hemionus and E. grevyi.

- 12. Equus suessenbornensis, Wüst, 1901 [241] (1.5–0.6 Ma). The lectotype is IQW1964/1177, a P2-M3 from Süssenborn, Germany. It is a large horse, larger than E. stenonis and E. livenzovensis but smaller than E. major. As for E. altidens, the species has been described from the Middle Pleistocene in Süssenborn [241], even if its best-known sample comes from the Georgian locality of Akhalkalaki (ca. 1.0 Ma) [242]. In addition to Akhalkalaki and Süssenborn, it has been reported in Central European localities such as Stránská Skála (Czech Republic) and Ceyssaguet and Solilhac (France) [216,243,244]. Over the last decades, its biochronologic range was extended to the late Early Pleistocene, with its earliest occurrence in the Italian localities of Farneta and Pirro Nord [216,231] and in the Spanish sites of Barranco León 5 and Fuente Nueva 3 [245].

- 13. Equus apolloniensis, Koufos et al., 1997 [246] (1.2–0.9 Ma). The holotype is LGPUT-APL-148, a nearly complete cranium from Apollonia, Greece [246]. It is a peculiar species of the late Early Pleistocene, mostly recorded from the locality of Apollonia–1 (Mygdonia Basin, Greece) and, possibly, from other localities of the Balkans and Anatolia [244,246,247]. As reported by Gkeme et al. [247], this species differs from E. stenonis and other European Early Pleistocene Equus, with a distinct cranial morphology, and its size is intermediate between E. stenonis and E. suessenbornensis. Koufos et al. [246] interpreted E. apolloniensis as an intermediate species between E. stenonis and E. suessenbornensis, whereas Eisenmann and Boulbes [248] considered E. apolloniensis as “a step within the lineage of asses”.

- 14. Equus wuesti, Musil, 2001 [249] (1.1–0.9 Ma). The holotypes are IQW1980/17067 and IQW1981/17619, two fragmentary mandibles with p2-m3 from Untermassfeld, Germany [249]. It has been established from the Epivillafranchian locality of Untermassfeld (Germany). Musil [249] reported isolated teeth, mandibles and long bones with primitive and derivate characteristics, and a larger size when compared with the widespread E. altidens. This evidence was also reported by Palombo and Alberdi [232], highlighting a more robust morphology of the postcranial elements. However, scholars disagree on its possible origin. Forsten [250] considered E. wuesti close to and derived from E. altidens, whereas others [249,251] recognized E. wuesti as the possible source for E. altidens. Nevertheless, considering the latest E. altidens discoveries [14,231,232,238], this last hypothesis seems to not be well supported. Palombo and Alberdi [232] suggest also that it can represent an ecomorphotype of E. altidens.

- 15. Equus petralonensis, Tsoukala, 1989 [252] (ca. 0.4 Ma). The holotype is PEC-500, an mc3 from Petralona Cave, Greece [252]. It is a slender and gracile horse from Greece (Petralona Cave). However, the taxonomic status of this species has been actively debated. Forsten [250] considered E. petralonensis as being a member of the E. altidens group, together with the Early Pleistocene equids from Libakos, Krimini and Gerakaou. Eisenmann et al. [67] synonymized E. petralonensis with Equus hydruntinus, within the subspecies E. hydruntinus petralonensis. Despite the taxonomic controversy surrounding this species, E. petralonensis may be considered a stenonine horse because of its mandibular cheek tooth morphology [246].

- 16. Equus graziosii, Azzaroli, 1969 [253] (MIS 6). No access number is available for the holotype, which is figured in Azzaroli [254] (Pl. XLV, Figure 1a,b) as a complete cranium from Val di Chiana, Arezzo. It is an enigmatic species from the late Middle–Late Pleistocene. It was described as a different species by Azzaroli [254] based on a partial cranium, mandibles and postcranial elements. According to Azzaroli [254], the cranium and maxillary and mandibular cheek teeth have typical asinine features, although some other authors have highlighted the morphological similarities with E. hydruntinus [244,255,256]. The evolutionary and phylogenetic position of E. graziosii is still questionable.