Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Four-point bend testing of a drop-stitch fabric inflatable panel at three different span-to-depth ratios and three different inflation pressures illustrates the large magnitude of shear deformations due to transverse loads.

- A rigorous mechanics-based model is developed to incorporate the nonlinear shear constitutive relationship of the panel sidewalls to predict the deflections of panels subjected to four-point bending. The panel sidewall nonlinear shear stress-strain relationship was developed experimentally from results of torsion tests and used in conjunction with this new modeling approach to quantify shear deflections with Timoshenko beam theory.

- To improve panel shear stiffness, a second specimen was fabricated with braided sidewalls to align fibers more closely with the principal stress directions. Four-point bending tests of this specimen verified that overall panel deflections decreased, with the largest reductions occurring at the lowest inflation pressure and smallest panel span-to-depth ratio.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- The panel shear deflections make up as much as 78% of the total panel deflection at small span-to-depth ratios, verifying the importance of accurately determining panel shear constitutive properties and incorporating them in panel deflection predictions.

- Load-deflection results from the panel with braided sidewalls indicate that this approach shows promise for increasing drop-stitch panel stiffness.

Abstract

In this paper, the impact of shear deformations on the load–deflection response of transversely loaded inflatable panels made from drop-stitch fabric is explored. A nonlinear shear constitutive model was derived from torsion tests and integrated into Timoshenko beam theory to predict deflection components. Four-point bend tests of the same panel are conducted at pressures of 34.5, 68.9, and 103 kPa and for span-to-depth ratios of 7.2, 12.5, and 17.8 to give load–deflection response with varying levels of shear deformation. Analytical, mechanics-based expressions are derived to quantify load–deflection response due to bending and shear, including deflections caused by the drop-stitch yarns. The resulting expressions are shown to predict the measured load–deflection behavior to within 20% at the theoretical wrinkling load while indicating that the midspan deflection caused by shear deformations including the effect of the drop-stitch yarns are 78% of the total panel deflection for the lowest inflation pressure and smallest span-to-depth ratio. An approach to reducing panel shear deformability through the incorporation of braided sidewalls is proposed, and a second panel with this modification is fabricated and tested in four-point bending to experimentally demonstrate effectiveness. For the smallest span-to-depth ratio, shear stiffening reduced panel midspan deflection by 17–22% depending on inflation pressure.

1. Introduction

Inflatable fabric beams, arches and panels used as structural members possess high strength-to-weight ratios, regain their original shape and capacity following overloading, and can be stowed in a small volume when deflated and re-deployed multiple times. The bending response of inflated members subject to transverse loads has been studied for many years, with early analytical research focused on the response of inflatable beams with circular cross-sections defined by isotropic membranes [1,2,3,4]. Subsequent studies have examined the load–deflection behavior of inflated fabric beams analytically and computationally [5,6,7,8,9,10], and significant experimental research has also been conducted on this topic [9,11,12,13,14,15,16,17], often in conjunction with finite-element simulations or analytical approaches to predicting load–deformation response. Common observations are that beam stiffness and capacity increase with increasing inflation pressure, although the mechanics of these increases can be due to several factors. One important response driver is fabric wrinkling, a local buckling of the fabric shell that occurs when the stresses due to applied loads exceeds the initial inflation-induced pre-stress which leads to softening load–deformation response [12,13,14,15,16,17].

The stiffening behavior driven by the internal pressurized air as the beam undergoes deformation-induced volume changes has also been treated in prior work, and this concept was first introduced by Fichter [4] for shear deformations of an inflated beam made from a linearly elastic membrane. Decades later, Fichter’s original result was duplicated by the application of pressure–volume work of the enclosed internal air ( work) using a Timoshenko beam framework [10]. The shear stiffening effect has also been addressed by treating the inflation pressure acting on the inner surface of an inflated beam as a follower force [8,13]. Stiffening caused by post-wrinkling volume changes due to bending deformations has also been addressed [10,12]. Although reference [16] questions the appropriateness of beam theory for the analysis of inflated fabric members, it is generally regarded as a good descriptor of their behavior and continues to be used (see references [8,12,14,17], for example). Indeed, recent work experimentally demonstrated the appropriateness of beam theory for pre-wrinkling response using four-point bend tests of PVC-coated fabric beams [17].

Although most prior studies have focused on bending load–deflection response, a few have also addressed linearized buckling of straight inflated fabric columns without wrinkling [4,18] or considered the global stability straight inflated fabric columns accounting for fabric wrinkling [12]. Building on this, some studies have considered the response of inflated fabric arches, which must carry both compression and bending. Arch stability and buckling were treated in [19], although fabric wrinkling and work were not addressed. An experimental and computational treatment of the nonlinear response and stability of single arches can be found in [20], where the techniques developed in [10,12] for the treatment of wrinkling and consideration of work were implemented. In reference [21], the impact of wrinkling on arch load–deformation response and stability were addressed experimentally and computationally, and in reference [22] arch load–deformation response in the pre- and post-wrinkling range was assessed experimentally and via simulation. The response and deployment of an entire structure with supporting inflated arches and coupling beams was tackled in references [23,24].

Drop-stitch (spacer fabric) panels differ from more widely analyzed inflated fabric beams and arches with circular cross-sections. Their primarily rectangular cross-section that provides a flat load-bearing surface makes them practically appealing, as evidenced by their use in commercially available articles including inflatable boats, paddleboards and dive platforms. Recent research has shown that drop-stitch panels have potential for use as structural wall and roof members in rapidly deployable shelters through simulations of the impact of combined bending and compression due to wind and snow load on the deflections and capacity of drop-stitch panels [25]. In reference [26], the experimental and numerical assessment of drop-stitch panel bending performance demonstrated pressure-dependent stiffness and capacity, although only small panel deflections were considered. In [27], a drop-stitch panel was tested in four-point bending, showing increasing stiffness and capacity with increasing load and significant panel post-wrinkling stiffness and capacity. An experimental and numerical study considering wrinkling, post-wrinkling response, work and the impact of drop-stitch yarns on bending behavior is reported in reference [28]. One important conclusion of the study was that within the framework of Timoshenko beam kinematics, the drop-stitch yarns produce an additional bending moment as the beam deforms in shear, which increases panel deflections and reduces the wrinkling load. More recently, analytical and FE-based solutions were developed for panels subjected to two-way bending in the pre-wrinkling range [29], and reference [30] reports on the projectile impact behavior of drop-stitch panels.

Overall, the bending stiffness and strength of drop-stitch panels have received relatively little attention compared to inflated fabric beams and arches with circular cross-sections. One important theme common to both, however, is the impact of inflation pressure on response and the significance of shear deformations. The coated, woven fabrics from which most inflated fabric beams and arches as well as drop-stitch panels are made have low shear stiffness [12,17,28,31]. Recently, Zhang et al. [17] conducted biaxial tension tests and picture frame tests to assess the moduli of a coated, woven fabric used in an inflatable fabric beam and reported a secant elastic modulus that is approximately 17 times that of the shear modulus, and Ye et al. [15] report a coated fabric shear modulus that is less than 2% of the warp (axial) direction elastic modulus. Other prior research has indicated that drop-stitch panel deflections due to shear can be 50% or more of total midspan deflection even at modest span-to-depth ratios and intermediate inflation pressures [28]. Beyond increasing deflections under transverse loads, significant shear deformations will reduce panel compressive buckling capacity and therefore the ability to carry simultaneous bending and compression loads that are commonly encountered in many structural applications [25]. Further, while torsion tests of a panel from one prior study [28] indicate that the panel skins experience pressure-dependent, softening nonlinear shear stress–strain response, to the best of the authors’ knowledge all prior studies have considered only linear shear stress–strain behavior characterized by an effective or secant shear modulus for the prediction of panel load–deflection response.

This study specifically addresses the impact of shear deformations and shear stress–strain nonlinearity on the behavior of drop-stitch panels subjected to transverse loads through coupled experiments and analysis. A drop-stitch panel is tested in four-point bending for a range of span-to-depth ratios and inflation pressures to induce different levels of shear deformation. The same drop-stitch panel is then tested in direct torsion at different inflation pressures and an analytical framework is developed to allow the direct determination of the pressure-dependent nonlinear shear stress–strain constitutive response of the panel skin from measured torsion–twist data. Analytical expressions are developed to compute panel deflection accounting for bending, the nonlinear shear constitutive behavior determined from the torsion tests, and the effect of the drop-stitch yarns. Measured panel load–deflection response is then compared with predicted response, and the relative contributions of different deformation modes are quantified. Finally, a method of increasing panel shear stiffness by incorporating sidewalls with braided fabric is presented. A second panel fabricated with this modification is subjected to the same four-point bend test regime as the control panel to assess the impact of the shear stiffening. This study significantly expands on prior research into drop-stitch panel bending behavior that have treated the coated fabric sidewalls and linearly elastic [25,26,27,28,29]. Further, while previous studies have considered the effect of drop-stitch yarns on panel bending [25,28], this paper for the first time explicitly couples the combined effect of sidewall shear stress–strain nonlinearity and drop-stitch fabric yarns with the onset of wrinkling. Additionally, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, the modification of a drop-stitch panel to reduce shear deflections through modification of the panel sidewall fiber orientation has not previously been attempted in any study. Lastly, the experimental results presented here add to a relatively sparse set of available data on the bending load–deflection response of inflated drop-stitch panels.

2. Response of Panel with Woven Sidewalls Subjected to Four-Point Bending

2.1. Details of Test Specimen

The control panel with conventional woven sidewalls was made from the same drop-stitch material used in the panels examined in reference [28], with neoprene-coated layers of woven, 420 denier × 420 denier, nylon drop-stitch fabric having a weight of approximately 2710 g/m2 including the coating as reported by the manufacturer. The thickness of the coated drop-stitch fabric was measured to be approximately 2.1 mm. The sidewalls were made from 510 g/m2, 0–90 woven, polyester chafer fabric with a 680 g/m2 urethane coating for air impermeability and a coated thickness of 1.4 mm. Welded seams were used to connect the sidewalls and drop-stitch skins. The overall panel length between inflation ports was 2.98 m to accommodate bend testing with a range of span lengths. The panels were manufactured by Kennon Products, Inc. at their facility in Sheridan, WY, USA. Figure 1 shows a photo of the panel with woven sidewalls and Table 1 gives the measured panel height and overall width corresponding to as-tested inflation pressures.

Figure 1.

Photo of drop-stitch panel with woven sidewalls.

Table 1.

Overall dimensions of panels with woven sidewalls.

2.2. Test Protocol and Instrumentation

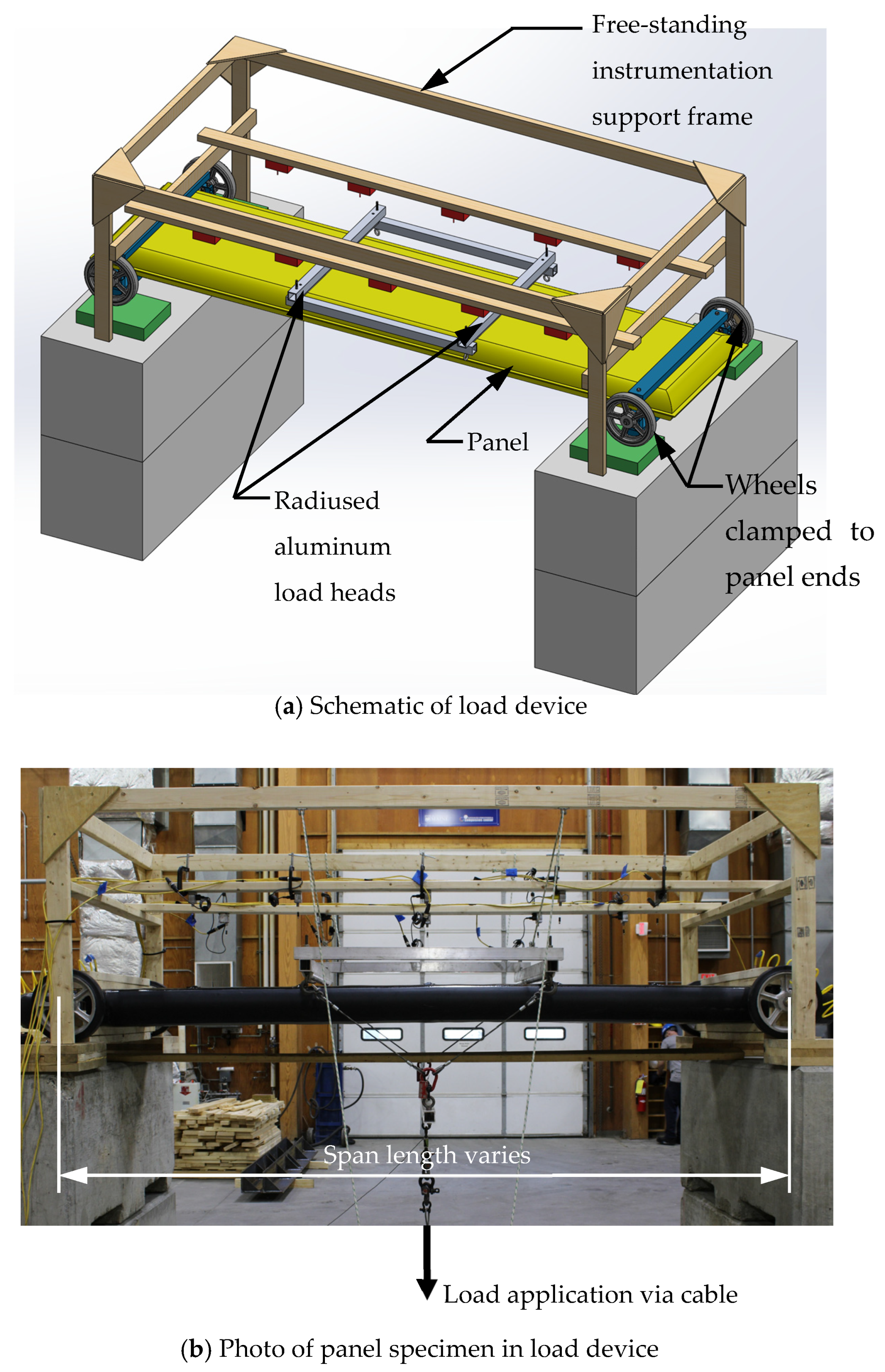

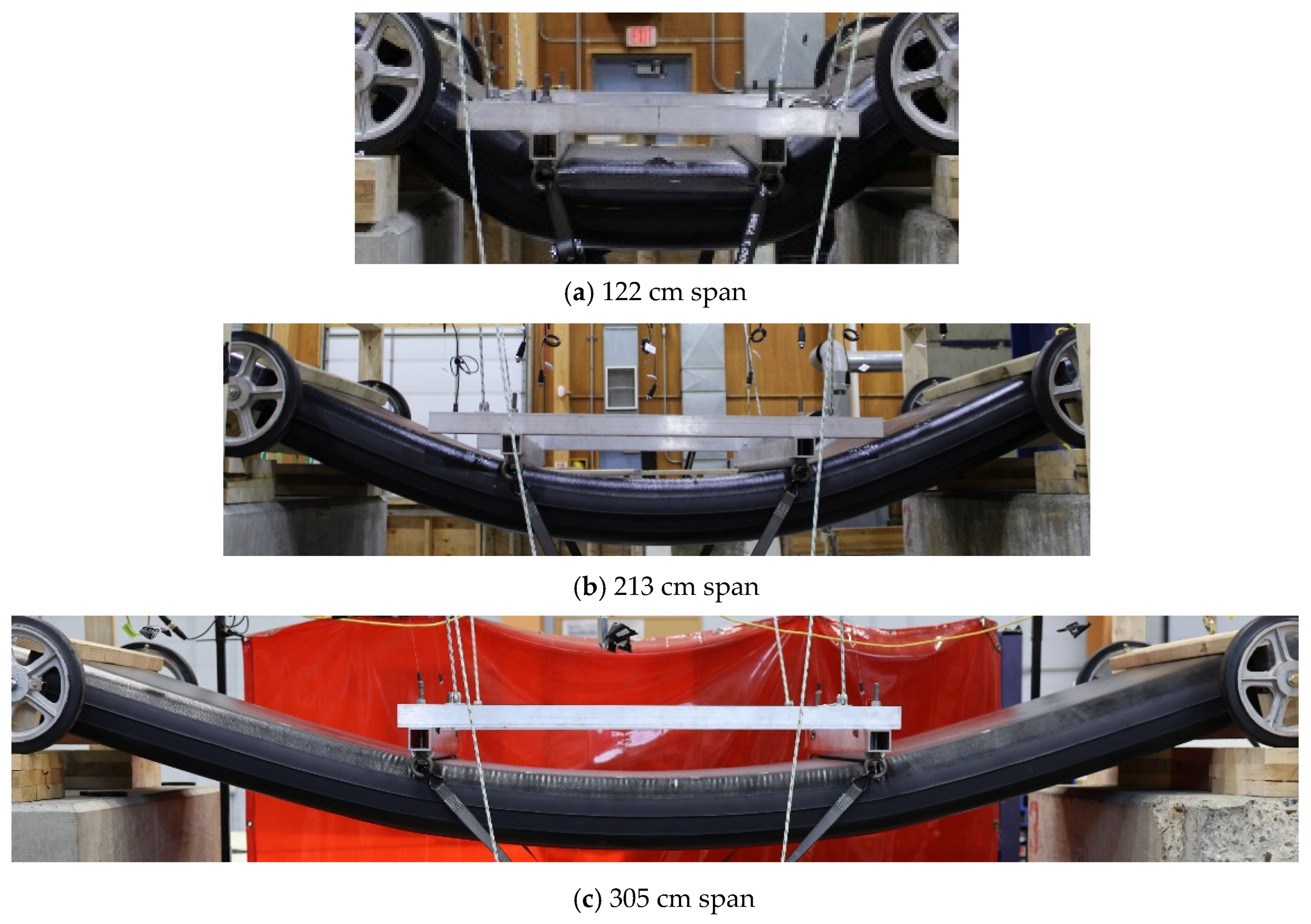

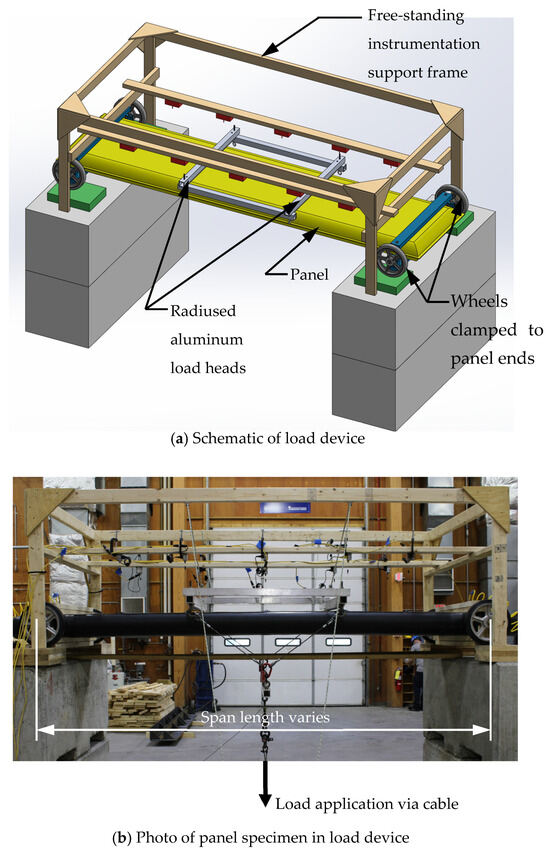

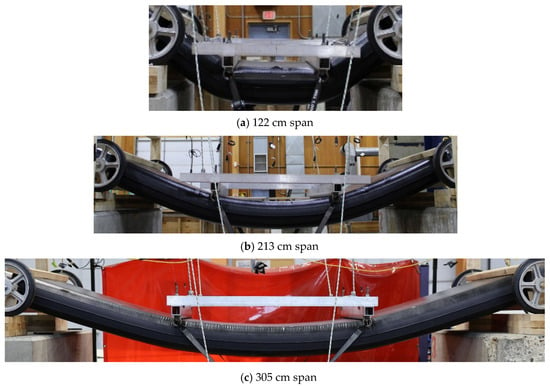

The panel was tested in four-point bending with three different span lengths of 122 cm, 213 cm and 305 cm. These spans were selected to produce span-to-depth ratios of approximately 7.2, 12.5 and 17.8 and drive varying amounts of shear and bending deflection. The test rig is illustrated both schematically and with a photo in Figure 2. To produce simply supported conditions, each end of the panel rested on a pair of wheels centered on the panel depth and clamped to the panel ends, which allowed both panel ends to freely translate inward and rotate as the panel displaced vertically. Load was applied via a lightweight aluminum load frame with high-density polyethylene load heads in contact with the panel that were machined to a 75 mm radius, and the spacing of the load heads was set to be one third of the span length for all tests. The load frame was pulled downward by a steel cable attached to an electro-mechanical actuator. The weight of the load frame and all hardware above the load cell was determined to be 179 N for the 122 cm span, 200 N for the 213 cm span, and 211 N for the 305 cm span. While the torsion tests and the bending tests described later were run in an indoor environment, they could have been somewhat affected by the modest temperature and humidity fluctuations in the test facility.

Figure 2.

Panel four-point bend test rig.

Tests were run in displacement control at a rate of approximately 15 cm/min after placement of the load frame on the panel. Prior tests of a panel made from similar materials run at both at this load rate and half that rate gave nearly identical results [28], indicating that rate effects should not be significant. All span configurations were tested at inflation pressures of 34.5 kPa, 68.9 kPa and 103 kPa and pressure was regulated and monitored during all tests. Three tests of each span and pressure configuration were run to ensure that consistent panel response was observed and results reported here are for the third replicate of each test. The maximum applied midspan displacement was approximately 18 cm for the two longer spans before the load heads began to significantly indent the upper panel surface. For the shortest 122 cm span, data were successfully gathered to a midspan displacement of approximately 10–12 cm before the load heads began to significantly indent the upper panel surface. The specimen was instrumented with three pairs of string potentiometers attached to the panel upper surface to capture any differential displacements across the panel width although no significant differential displacements were observed. One pair was attached at midspan, and one pair was attached 50 mm outside each load head within the shear spans.

2.3. Bend Test Results

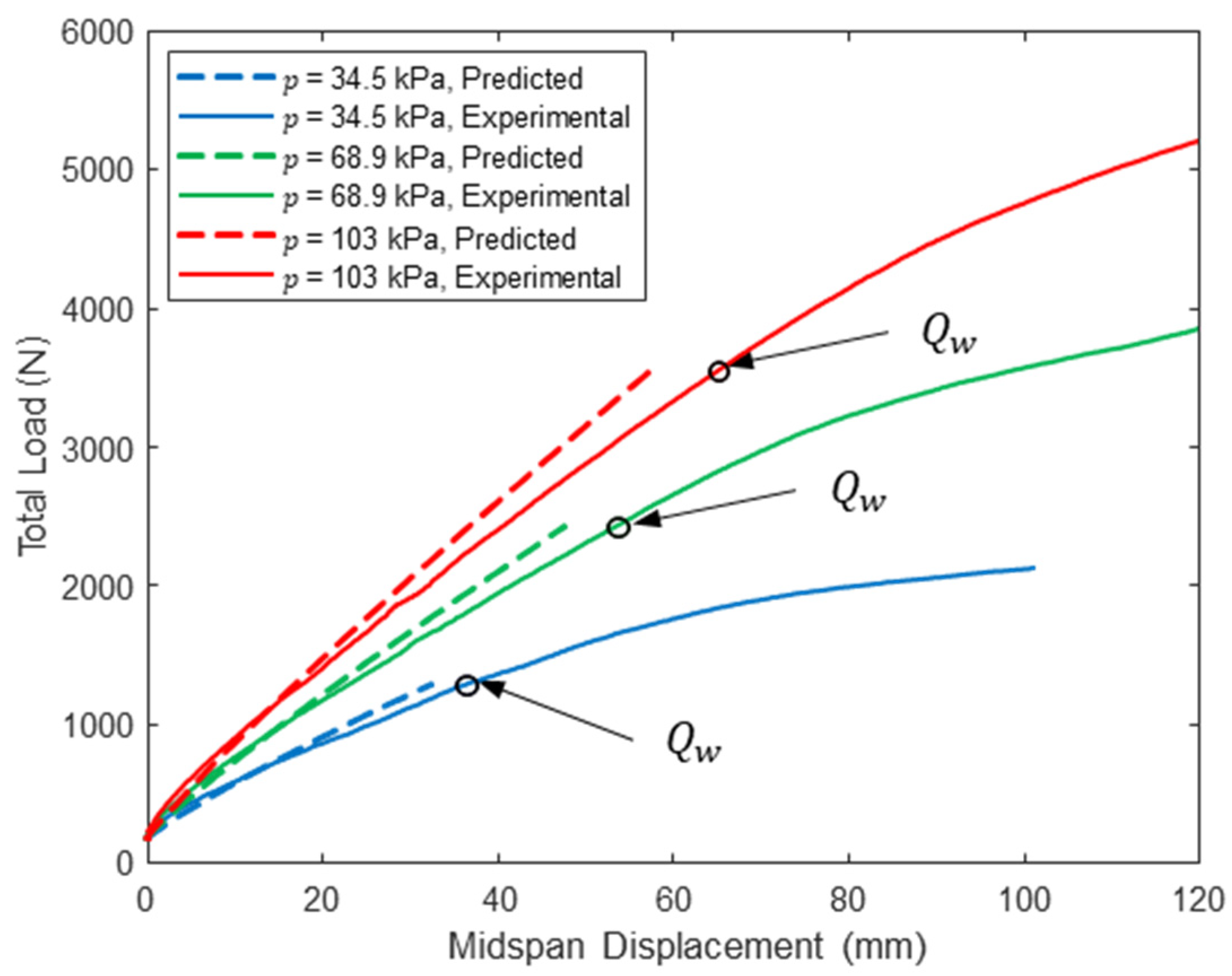

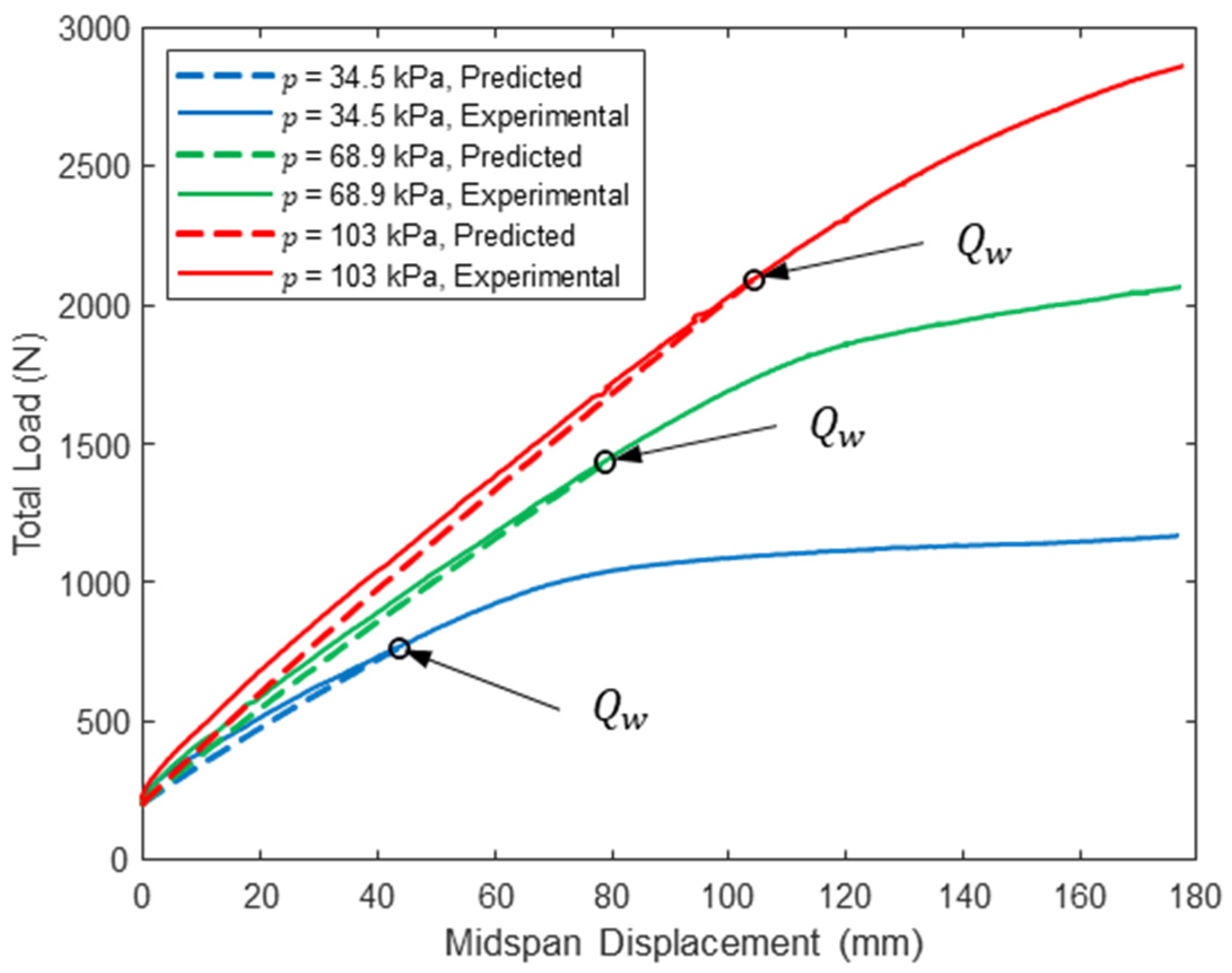

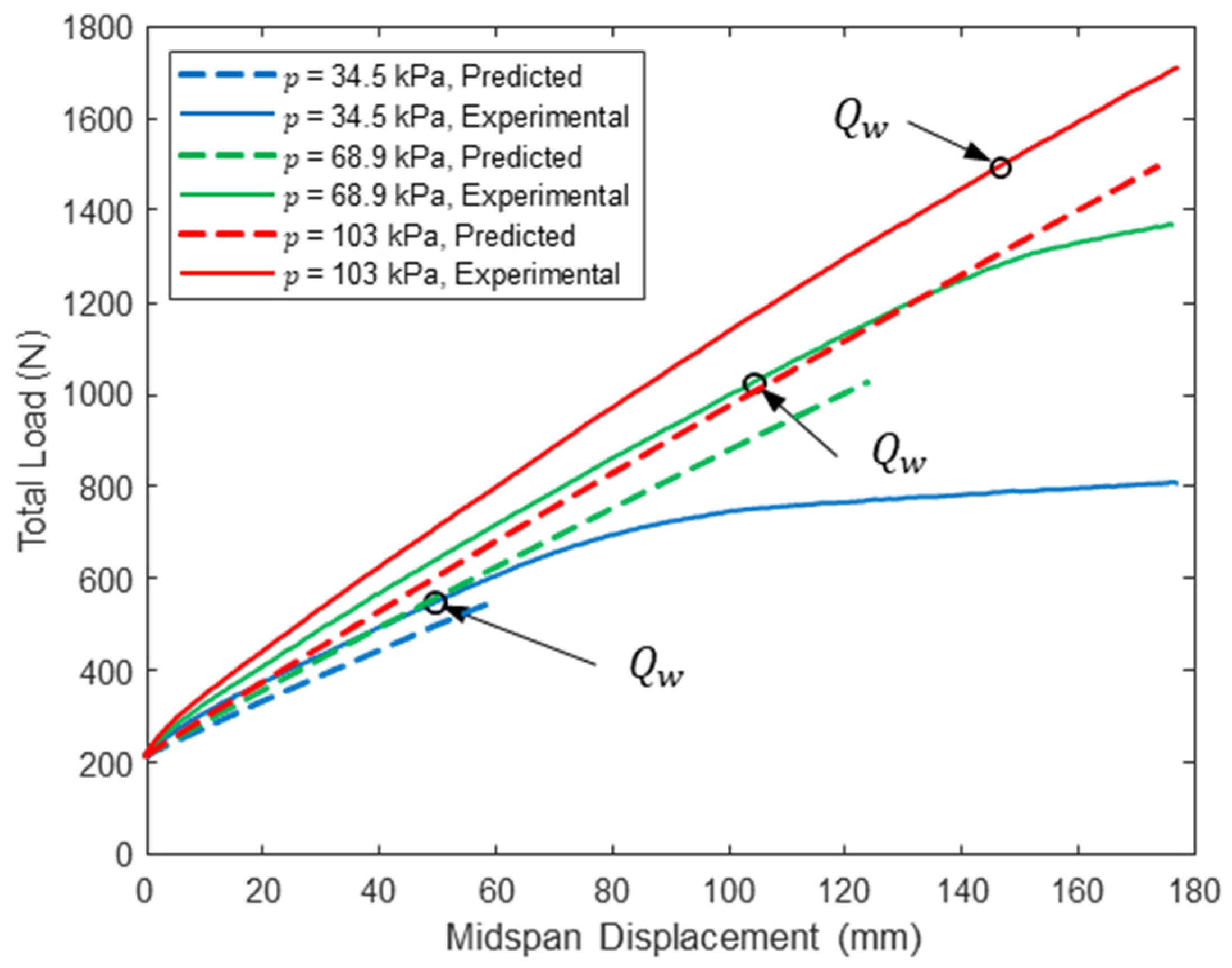

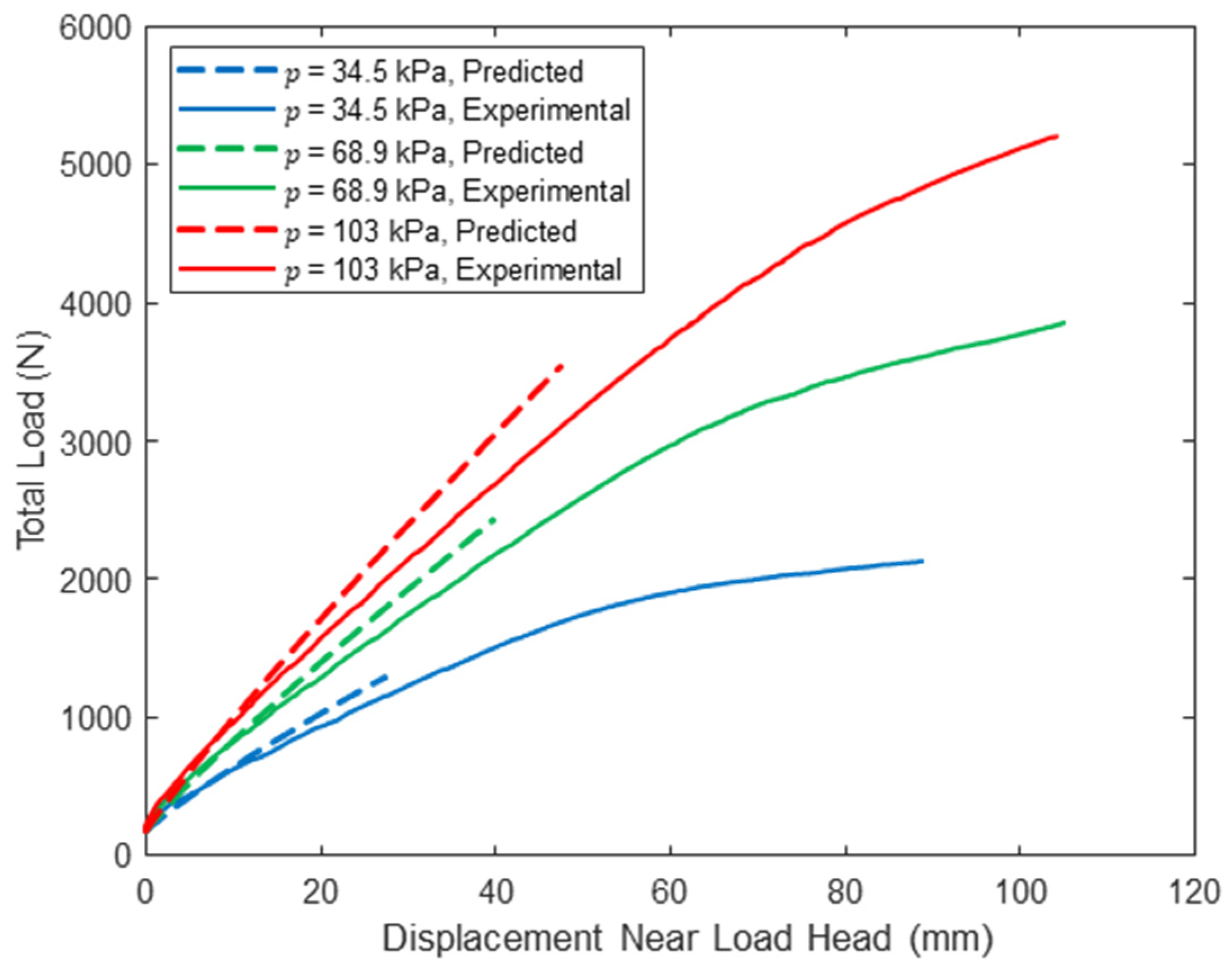

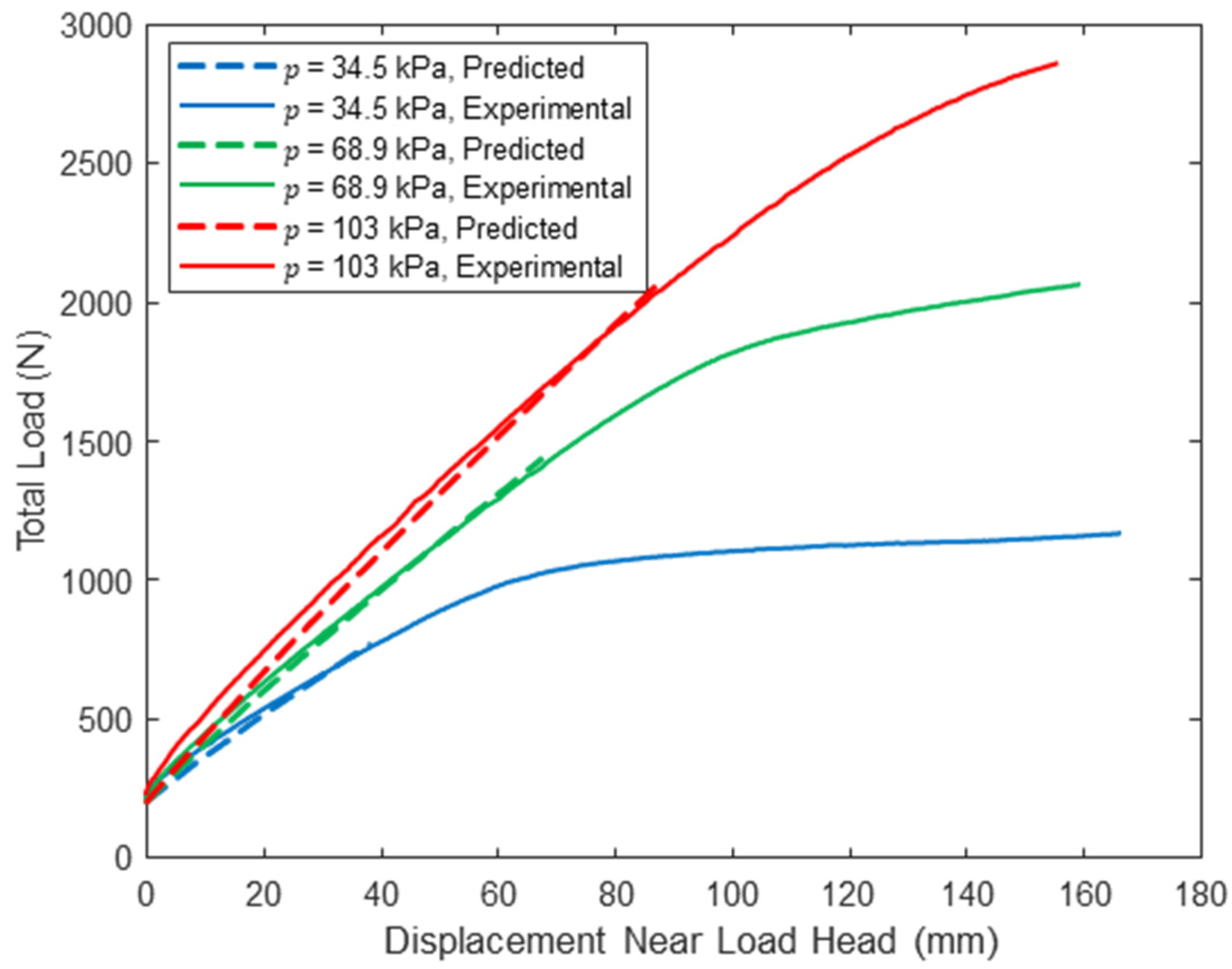

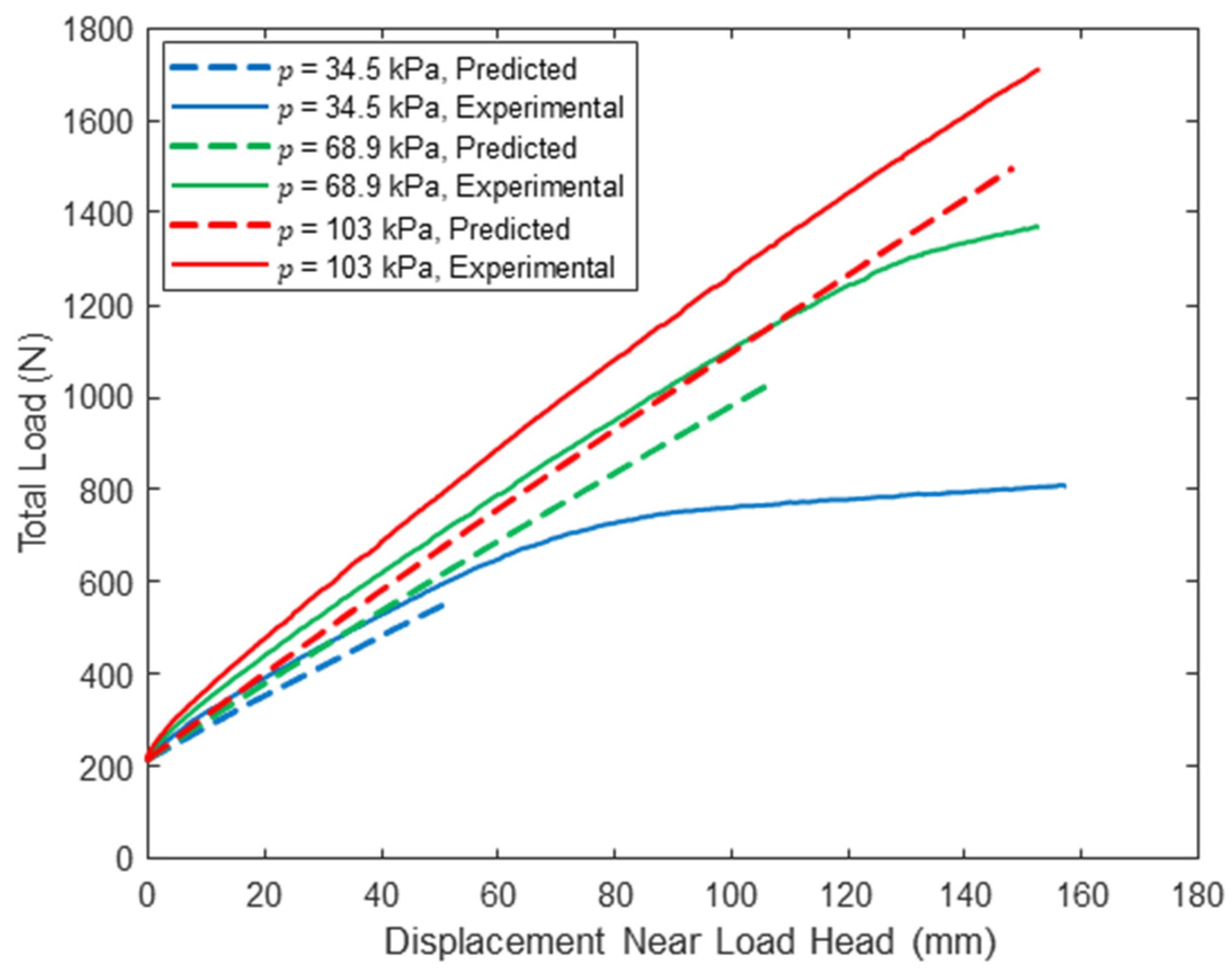

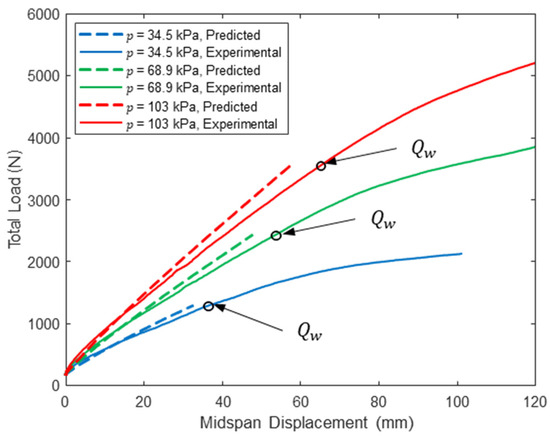

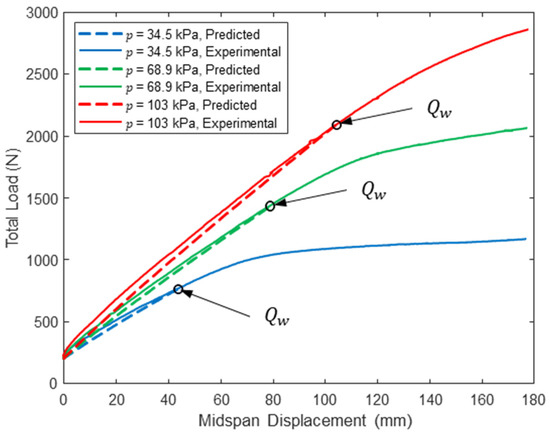

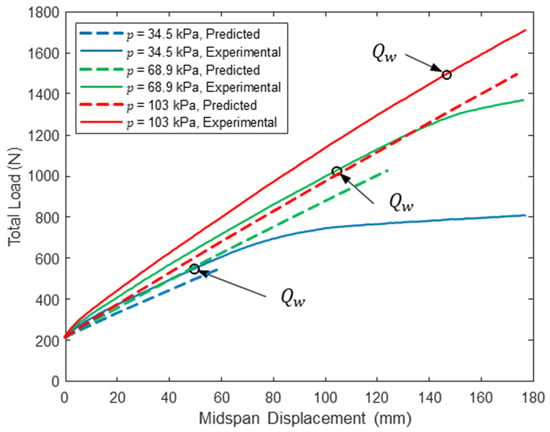

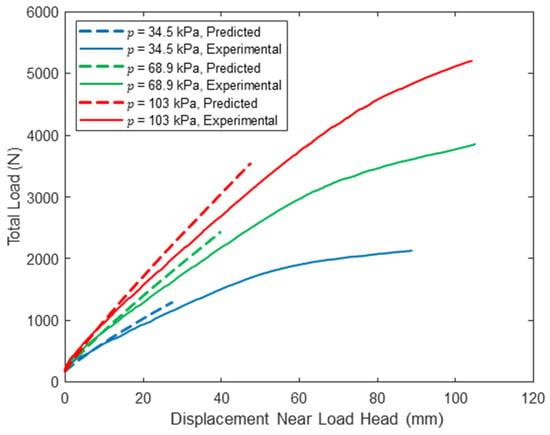

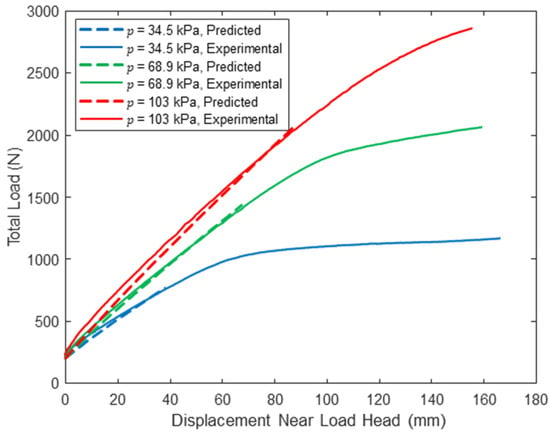

The midspan load–displacement response for each combination of span length and pressure are given in Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5, and load–displacement response 50 mm from the load heads is given in Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8. Data reported are the average of all string potentiometer readings at corresponding locations along the span, since no significant differences were recorded across the panel width or between string potentiometer pairs near the two load heads. Additionally, the total load includes the loading assembly weight, with displacement set to zero when the load assembly is placed on the specimen.

Figure 3.

Woven sidewall panel midspan load–displacement response (L = 122 cm).

Figure 4.

Woven sidewall panel midspan load–displacement response (L = 213 cm).

Figure 5.

Woven sidewall panel midspan load–displacement response (L = 305 cm).

Figure 6.

Woven sidewall panel load–displacement response near load head (L = 122 cm).

Figure 7.

Woven sidewall panel load–displacement response near load head (L = 213 cm).

Figure 8.

Woven sidewall panel load–displacement response near load head (L = 305 cm).

For all span lengths, the load–displacement response is nonlinear, although the nonlinearity is more pronounced for lower inflation pressures and shorter span lengths. This is because the panel was loaded into the post-wrinkling range, but wrinkling occurs at larger displacements with increasing span due to increasing panel compliance with increasing span. Panel wrinkling is discussed in detail later in this paper. Consistent with bend test results from prior studies [26,27,28], panel stiffness and capacity increase dramatically with inflation pressure. Panel capacity also increases significantly with decreasing span length. These observations are highlighted in Table 2, in which the range of measured loads corresponding to 100 mm of panel midspan displacement is reported for each combination of span length and inflation pressure and all three test replicates. In addition to highlighting the impact of inflation pressure on panel capacity and stiffness, the results in Table 2 illustrate the repeatability of the experiments: the maximum and minimum values differ by less than 5% for all combinations of test parameters and differ by less than 2% for five of the nine unique combinations.

Table 2.

Range of loads corresponding to 100 mm of observed midspan displacement for the three replicates of each test configuration.

The relative importance of shear deformation at different span lengths is illustrated qualitatively in Figure 9, which contains photographs of the displaced panel taken at a midspan displacement greater than or equal to the panel depth for all span lengths. As noted earlier, quantitative displacement data at these large displacements may not be useful due to large wrinkles forming near the load heads and the load heads deforming the panel upper surface, especially for the 122 cm span. However, these images clearly show the shortest span with a deformed shape closely matching three straight line segments, which is consistent with shear deformation dominating panel load–deflection response. As the span length increases, panel curvature becomes much more pronounced, which is consistent with bending deformations contributing more to total deflection. This topic is explored analytically in greater detail later in this paper.

Figure 9.

Panel displaced shapes at large deflections.

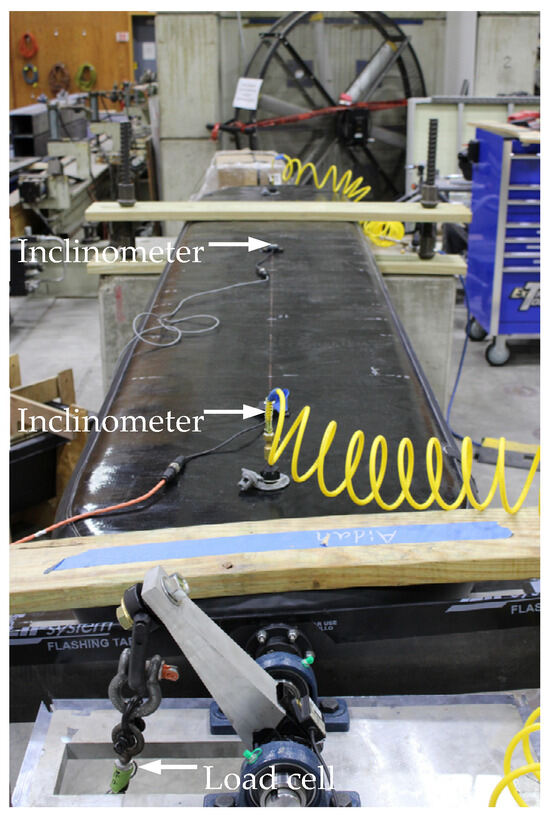

3. Development of Woven Panel Fabric Shear Constitutive Relationship

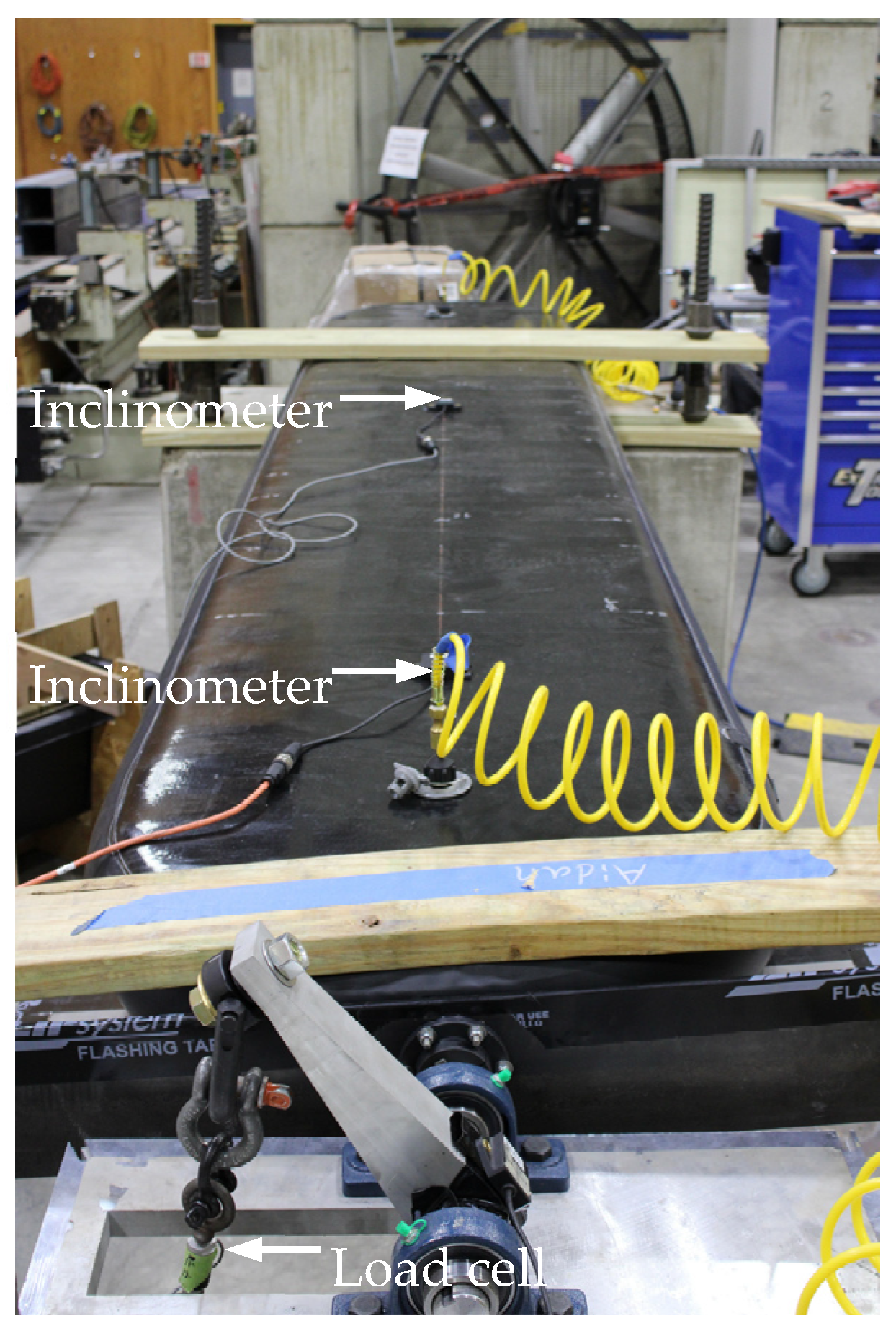

To assess the shear stiffness of the drop-stitch control panel with woven sidewalls, it was subjected to direct torsion while the angle of twist per unit length was measured. Figure 10 shows the test fixture where the far end of the panel was clamped and torque was applied at the opposite end using an electro-mechanical actuator connected via a steel cable to the end of a lever arm keyed to a bearing-supported shaft. An inline load cell was used to measure force, and the inclination of the lever arm was also measured so that torque could be accurately computed from the applied force and mechanism geometry at any angle of twist [32]. The length of panel subjected to torque was 1.4 m, and digital inclinometers spaced at 84 cm were placed on the panel upper surface and centered within that length to measure . Pressure was regulated during the torsion tests.

Figure 10.

Drop-stitch panel in torsion test fixture.

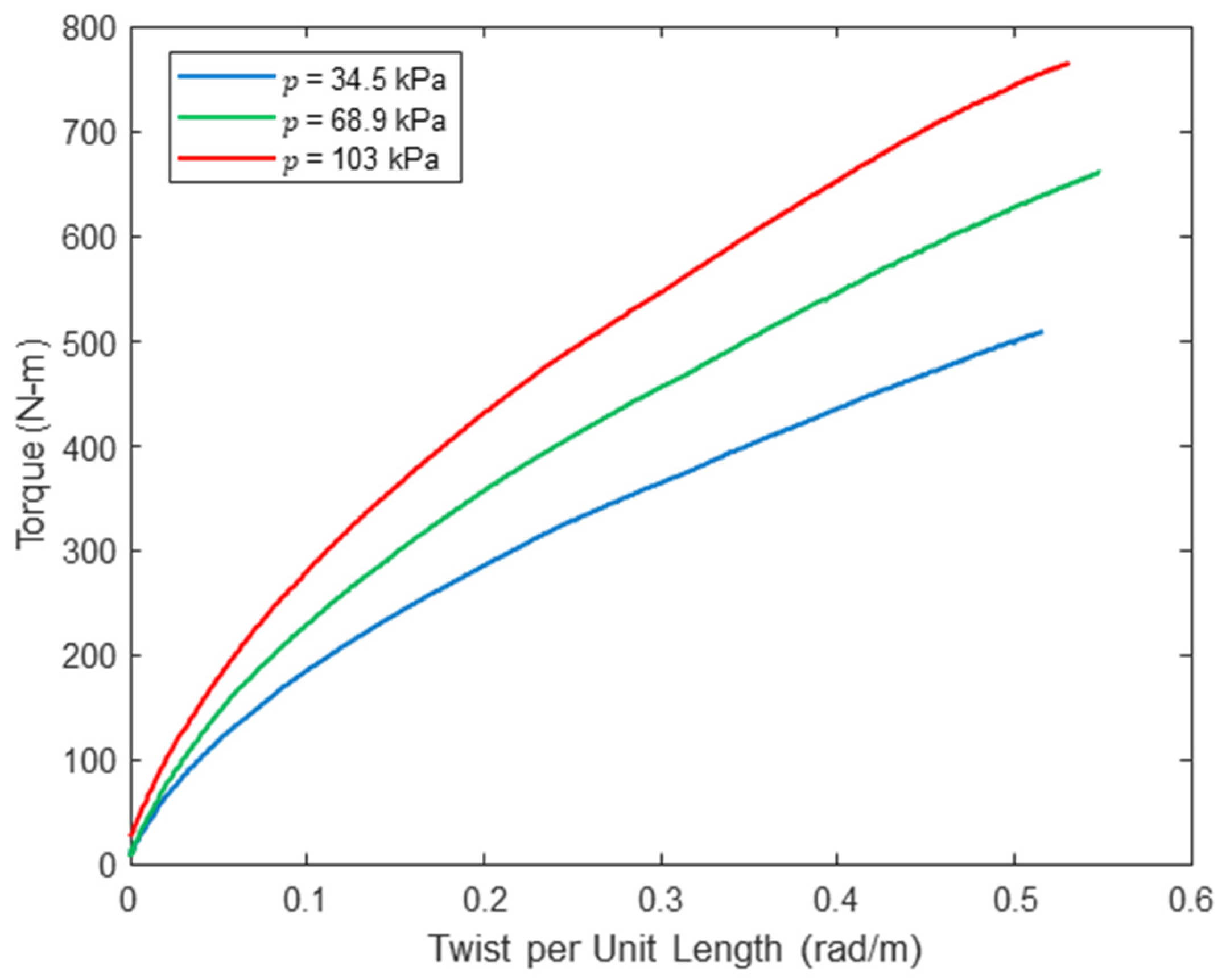

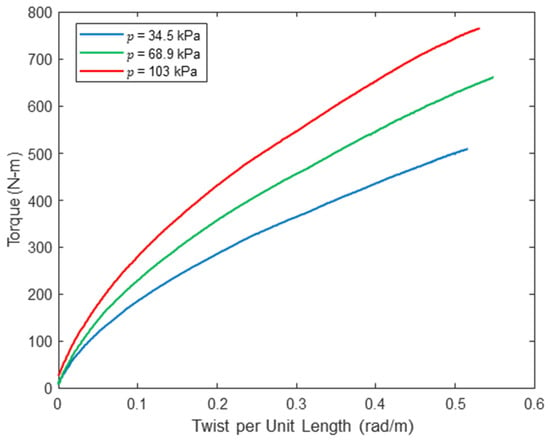

The panel was tested five times at each inflation pressure of 34.5 kPa, 68.9 kPa and 103 kPa, and after the first two cycles of load the results were very repeatable. Small residual twists remained after unloading, which were 0.014 rad/m, 0.024 rad/m and 0.018 rad/m immediately after unloading for pressures of 34.5 kPa, 68.9 kPa and 103 kPa, respectively. These values are all less than 4.4% of the maximum applied twist per unit length. Following deflation and subsequent inflation, the panels returned to their original shape. For torque vs. for the fifth repetition, all inflation pressures are shown in Figure 11, which highlights two important aspects of the response. First, increasing inflation pressure significantly increases shear stiffness: for a large angle of twist per unit length of 0.5 rad/m, the panel inflated to 34.5 kPa carried a torque of 497 N-m, while the panel inflated to 103 kPa carried a torque of 741 N-m. This is consistent with prior experimental research, which has indicated significant increases in coated, woven fabric shear stiffness with inflation pressure [12,28,31]. Second, the relationship between and is nonlinear. This implies a nonlinear relationship between shear stress and strain , which to the best of the authors’ knowledge has not been explored or quantified in prior research on the load–deflection response of inflatable fabric beams or drop-stitch panels. It is possible that some tension developed in the specimen during testing, as both ends were clamped and restrained against movement in the longitudinal direction of the panel, which could have affected the shear response of the panel. In the future, the clamped end should incorporate two layers of low-friction material between the panel and clamps to prevent significant tension from developing.

Figure 11.

Measured torque vs. twist per unit length.

We note here that the sidewalls are effectively a soft composite, and the shear constitutive response is therefore a function of the coating properties and thickness as well as the fabric, although this test and these results do not allow their relative contributions to be determined. In their biaxial shear tests of PTFE- and PVC-coated woven fabrics, Xu et al. [33] point out that they resist shear deformation through a complex interaction between warp and weft yarns and interplay between the coating and yarns. The latter will depend on the degree of penetration between the coating into the fabric, a topic examined using diffusion theory by Horiashchenko et al. [34] for fabrics to which a hot melt polymer was applied to fabric surfaces. Reference [35] contains a detailed review of prior analytical and numerical models that treat coated fabrics as soft composites and consider the coupled elastic or viscoelastic contributions from the yarns and coating. Ultimately, however, the macroscopic engineering shear properties of coated fabrics are determined experimentally using biaxial cruciform tests or picture frame tests [36], torsion tests of cylinders [31], or other fabric-specific methods (see reference [35] for a detailed review of fabric shear test methods). Further, a softening shear stress–strain response like that seen in this study is often observed at the modest magnitudes of strain typical for inflated beams, arches and panels [33].

Because the sidewall and drop-stitch top and bottom skins do not have the same thickness or fabric density, they cannot be assumed to carry the same shear stress when the panel is subjected to torsion. To address this, the measured thicknesses of the panel skin and sidewall are employed in the analysis described next while the fabric shear stress–strain () response is assumed to be identical for both the top and bottom skins and sidewalls. However, it must be noted that this assumption of constant material stress–strain response may not be strictly correct, since it could vary with changes in the fiber density and the relative amount of and type of coating present in the individual elements of the panel. Further, this assumption is necessary for the following development of the response which implies that the impact of different shear constitutive relationships of the sidewalls and drop-stitch skins cannot be explored.

With these caveats, the nonlinear response can be derived from the measured vs. at each inflation pressure as follows. First, the response is considered to be a series of piecewise linear relations, where is a small increment of torque producing a corresponding increment of twist per unit length . This implies that a change in shear stress can be computed as shown in Equation (1), where is the area enclosed by the meridian of the cross-section and is the thickness of the coated fabric at any location in the section 1.4 mm for the sidewalls and 2.1 mm for the drop-stitch skins). As described in [33], this relationship is based only on equilibrium, which requires that shear flow (the product of shear stress times thickness) be constant around the thin-walled cross-section. Equation (1) therefore applies regardless of whether the material shear stress–strain relationship is linear or nonlinear and for closed sections with varying wall thickness.

Considering the shear stress–strain relationship to be similarly piecewise linear, an increment of shear stress caused by an increment of shear strain is given by Equation (2), where is the tangent slope of the fabric curve (tangent modulus).

It then follows from the basic mechanics of torsional deformation [37] that can be computed from Equation (3), where is the torsional moment of inertia given by Equation (4) for the closed, thin-walled panel section. In Equation (4), is computed incorporating the different wall thicknesses of the drop-stitch skin () and sidewalls (), and is the flat width of the panel top and bottom skins, computed as .

Combining Equations (1)–(4) gives the relationship of Equation (5) between an increment of shear strain in the panel sidewalls caused by . Note that since the variation in fabric thickness around the panel significantly influences per Equation (4), the variation in thickness will have a significant impact on per Equation (5) and thus does impact the derived shear constitutive relationship.

Given that and can now be computed using Equations (1) and (5) for measured values of and with no dependence on the material constitutive properties, it follows that the shear stress in the sidewall and corresponding sidewall shear strain can be determined for any measured pair of torque and corresponding angle of twist per unit length per Equations (6) and (7).

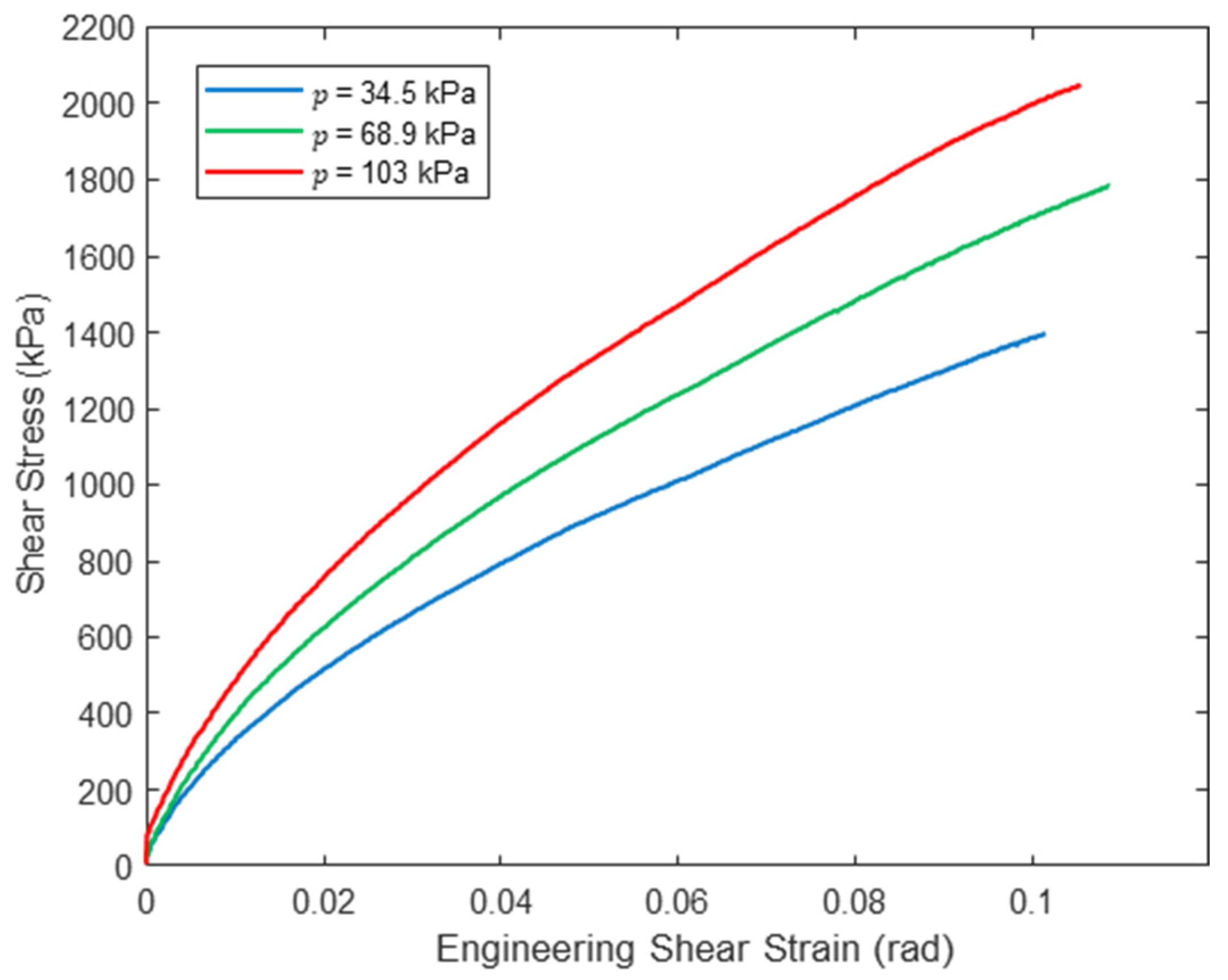

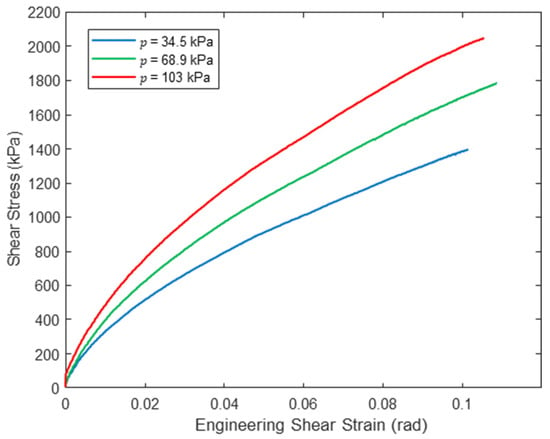

Figure 12 shows the nonlinear response determined from the measured vs. at each inflation pressure and Equations (6) and (7). These pressure-dependent shear constitutive relationships are used later in this paper to calculate the deflection of the drop-stitch panels subjected to four-point bending.

Figure 12.

Panel woven sidewall shear stress–strain relationship.

4. Mechanics of Woven Sidewall Panel Bending and Calculation of Load–Deflection Response Accounting of Shear Nonlinearity

Prior studies on the prediction of the bending response of inflated fabric panels [25,26,27,28] have relied on Timoshenko beam theory, and shear deflections of these structures can be significant. The results of one study on a panel made from the same drop-stitch fabric as those tested here and having a span-to-depth ratio of 12.1 indicate that 50% or more of deflection due to transverse load is caused by shear deformations, which is a consequence of the relatively low shear stiffness of the fabric relative to its Young’s modulus [28]. It is also important to incorporate the stiffening effect of pressure–volume work done by the confined air undergoing deformation-induced volume changes [4,10,15,17] which results in the internal shear force given by Equation (8) when Timoshenko beam kinematics are imposed. Here, is the resultant force caused by the inflation pressure acting on the internal area enclosed by the panel skins .

The application of Equation (8) is straightforward for the calculation of shear deflections if the fabric shear stress–strain response is linearly elastic and characterized by a constant shear modulus . However, this is not the case if the shear stress–strain relationship is nonlinear. Both the large shear deformations of drop-stitch panels and the applicability of Equation (8) play a significant role in the calculation of the onset of panel wrinkling as discussed next.

4.1. Determination of the Pressure-Dependent Wrinkling Loads

An important consideration is the calculation of the wrinkling load , defined as the transverse load that results in net longitudinal fabric stress reaching zero, i.e., the magnitude of the load-induced compressive bending stress in the panel skin equals the magnitude of the longitudinal tensile prestress caused by the inflation pressure. will depend in part on the wrinkling moment given below in Equation (9), which is determined by equating inflation-induced skin pretension to load-induced compressive stress caused by assuming linearly elastic longitudinal stress–strain response. In Equation (9), is the cross-sectional bending moment of inertia of the panel, is the cross-sectional area of the panel skin, and other terms are as defined previously.

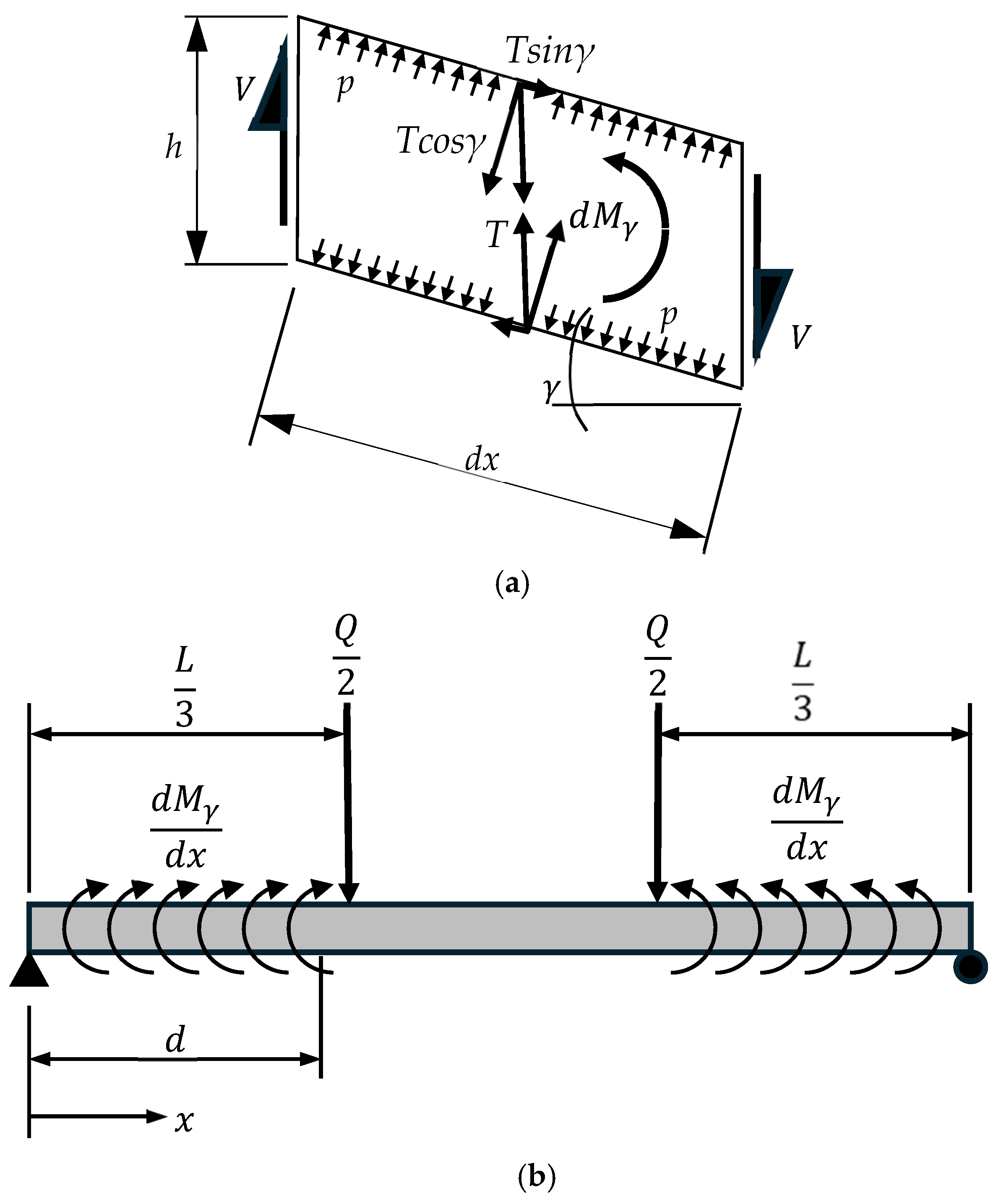

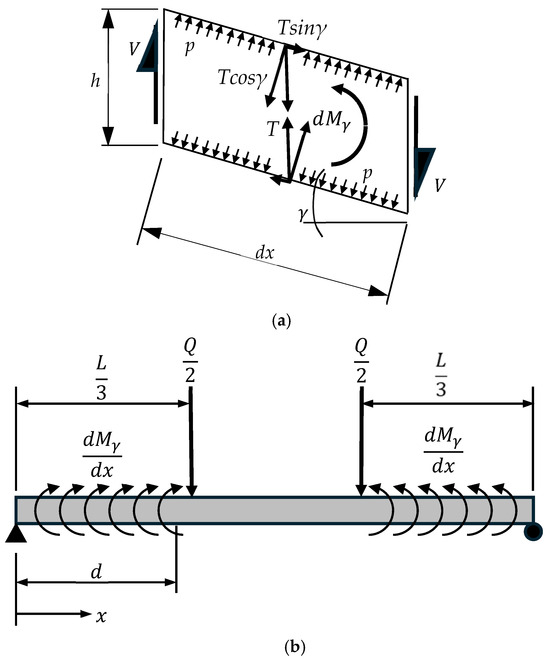

However, as detailed in references [25,28], does not depend only on the applied load at wrinkling , because shear deformation of a drop-stitch panel subjected to transverse loads causes an additional distributed bending moment due to the unbalanced horizontal force component of the drop-stitch yarns. This is illustrated in Figure 13a, which shows a differential length of panel subjected to a shear force caused by external transverse loads which produces an engineering shear strain that is consistent with Timoshenko beam kinematics [28]. In Figure 13a, represents the tension in the drop-stitch yarns which remain vertically oriented under a pure shear deformation per Timoshenko beam theory.

Figure 13.

Illustration of panel shear deformations and effect of drop-stitch yarns on panel bending. (a) Shear deformation of a differential length of panel dx. (b) Additional moment caused by drop-stitch yarn for panel in four-point bending.

Equilibrium of the differential length of panel in Figure 13a gives the additional distributed moment shown in Equation (10) [25,28].

This distributed moment causes additional longitudinal stress in the panel fabric, reducing the wrinkling load . The distributed moment can be treated like an externally applied load effect as illustrated in Figure 13b for the case of four-point bending considered here. The maximum moment in the panel due to the drop-stitch yarns and shear strain occurs over the middle third of the span and can be computed as shown below in Equation (11) since the shear strain is constant over each load span and zero between the load heads.

If the panel fabric is assumed to behave linearly elastically in both bending and shear, it is relatively straightforward to derive an explicit expression for for the case of four-point bending and decreasing the total shearing rigidity reduces as shown in reference [25]. However, the adoption of a nonlinear shear stress–strain relationship precludes the development of a simple closed-form expression for . Ignoring the panel self-weight since it produces a midspan moment that is very small compared to the moments due to the applied load at wrinkling and and setting the total moment in the panel equal to the wrinkling moment yields Equation (12), where denotes the shear strain corresponding to the onset of wrinkling.

The application of vertical force equilibrium to the panel shear spans gives Equation (13), which accounts for the shear force due to internal pressure of Equation (8).

In Equation (13), is the panel sidewall shear stress at the onset of wrinkling corresponding to , which can be determined for different inflation pressures via interpolation of the experimental shear stress–strain relationships developed previously for different inflation pressures (see Figure 12). is the shear area of the sidewalls defined in Equation (14), which incorporates the usual factor of two for a thin-walled tube that is based only on equilibrium and is independent of the shear constitutive behavior [37]. This is equivalent to basing shear strain on the maximum shear stress at the panel’s neutral axis.

Substituting Equation (13) into Equation (12) gives a single nonlinear equation that can be solved numerically for the one unknown corresponding to each combination of test inflation pressure and span length , which was accomplished for the specific panels studied here using Newton’s method. Once is known, the wrinkling load is computed from Equation (12). All computed wrinkling loads and corresponding shear strains are given in Table 3. In all cases, the shear strains at wrinkling are significantly less than the maximum shear strains determined from the torsion tests (see Figure 12). The values of reported in Table 3 are plotted with the experimental midspan deflections in Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 and generally agree with an experimentally observed increase in softening load-deformation response which is consistent with expectations.

Table 3.

Computed wrinkling loads and corresponding shear strains

4.2. Calculation of Panel Midspan Deflections

The midspan deflection of the panel can be computed for any load as the sum of the bending deflection , deflection due to the distributed moment produced by the drop-stitch yarns and shear deflection Because the fabric is considered axially linearly elastic with a Young’s modulus , the calculation of requires only the straightforward application of Equation (15) [37].

Both and result from shear deformations, and their computation requires first that the unknown shear strain corresponding to the load be calculated by solving Equation (16), which is the statement of vertical force equilibrium for any free body of the panel within the shear span. Equation (16) accounts for the increased shear stiffness arising from internal pressure (Equation (8)), and the sidewall shear stress depends nonlinearly on the shear strain according to the pressure-dependent, experimentally determined shear stress–strain relationships of Figure 12.

Once is known, the midspan shear deflection can be computed using Timoshenko beam kinematics as given by Equation (17).

The distributed moment caused by the drop-stitch yarn will be constant along each shear span since the shear force and are constant in this region and can be computed according to Equation (18) as derived in reference [25].

Repeating this process for a set of discrete loads gives all components of the panel midspan load–deflection response.

4.3. Calculation of Panel Deflections Within the Shear Spans

Deflections at a distance from the support due to bending and shear caused by any load are straightforward to compute using Equations (19) and (20) based on Timoshenko beam theory [37] once is determined through the use of Equations (19) and (20).

However, the calculation of the deflection due to the distributed moment caused by the drop-stitch yarns requires the evaluation of the integrals shown below in Equation (21). These expressions were developed by extending the formula for bending deflection due to a concentrated moment given in reference [37] to account for a uniformly distributed moment and taking advantage of the symmetry of the bending configuration.

Evaluating the integrals in Equation (21) gives the closed-form expression for of Equation (22).

5. Comparison of Predicted and Measured Load–Deflection Response of Panels with Woven Sidewalls

Calculating deflections requires that the fabric elastic modulus be known, which—similarly to the fabric shear stress–strain relationship—prior studies have shown to be pressure-dependent with increasing inflation pressure increasing [27,28]. In reference [28], the membrane modulus (the product of the continuum modulus and skin thickness) was estimated for drop-stitch panel fabric using inflation tests coupled with strain fields measured using digital image correlation. However, this approach did not account for the differing thicknesses of the sidewalls and drop-stitch fabric. In this study, a different approach is taken, where the measured midspan displacement for the 213 cm span specimen at the theoretical wrinkling load is used to back-calculate for each test inflation pressure. This intermediate span of 213 cm was chosen given that shear deflections will be more prominent in the shorter span, and less significant with the longer span. Alternatively, could have been back-calculated for each combination of pressure and span length, and the average for each pressure taken as the most representative value. Ultimately, of course, should be independent of span length, and there are inherent uncertainties and disadvantages with any method used to determine . However, using values of determined from the single intermediate span length of 213 cm and subsequently using them to predict the load–deflection response of the panels for all three spans provides some independent verification of their accuracy given that the relative amount of shear and bending deflection varies significantly for different spans. As with the shear response, all panel fabric is assumed to have the same modulus, but the thicknesses of the individual elements are considered when computing the bending moment of inertia . The resulting three back-calculated values of are 218 MPa, 245 MPa and 274 MPa for inflation pressures of 34.5 kPa, 68.9 kPa and 103 kPa, respectively. The 25.6% increase in over the full range of pressure agrees well with the 27.1% increase in membrane modulus reported in reference [28] for drop-stitch panels subjected to the same range of inflation pressures. Further, converting the membrane moduli from reference [28] to elastic moduli through dividing by the 2.1 mm skin thickness gives values of ranging from 206 MPa to 261 MPa, which agree well with the values back-calculated here.

A comparison between the predicted response and the experimentally measured midspan load–deflection response is provided in Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 for loads up to at the three tested span lengths and all three inflation pressures. Similarly, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8 include this comparison where displacements were measured within each shear span 50 mm from the load heads. The model midspan displacement predictions at exactly match the measured displacements for a span of 213 cm since the pressure-dependent values were back-calculated for this span length and string potentiometer location. However, predictions are reasonable for other spans and locations: the maximum relative error between the predicted and measured midspan displacement at is 18.2% for a span length of = 305 cm at all three inflation pressures, which provides a measure of confidence in the applicability of the mechanics detailed here.

Table 4 summarizes the breakdown of predicted displacements due to bending (, shear () and the drop-stitch yarn () at the onset of wrinkling. The reported values are computed as the total displacement corresponding to the application of and the weight of the load frame minus the displacement due to the weight of the load frame alone to be consistent with the results presented in Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8. The values in Table 4 indicate that the shear and drop-stitch yarn deflections, which are both driven by the shear deformability of the panel sidewalls, are largest when = 122 cm. They also decrease with increasing inflation pressure for all span lengths, which is a consequence of the stiffening effect of pressure–volume work due to shear deformations and the fabric itself stiffening with increasing inflation pressure (Figure 12). In the most extreme case with = 122 cm and = 34.5 kPa, the sum of and is 78% of the total predicted midspan deflection. However, even for the longest span and highest pressure where shear contributes the least to overall deformation, the sum of and is 43% of the total midspan deflection. These results emphasize the importance of determining the shear constitutive relationship of the panel sidewalls and accurately predicting shear deflections in cases where panel deflection is an important design consideration. Further, the large magnitude of the shear deflections indicates that increasing the shear stiffness of the panel sidewalls could be a practical way to increase overall panel stiffness. This is explored experimentally in the following section.

Table 4.

Breakdown of predicted displacements at the onset of wrinkling.

6. Behavior of Shear-Stiffened Panels with Braided Sidewalls

6.1. Panel Description and Fabrication

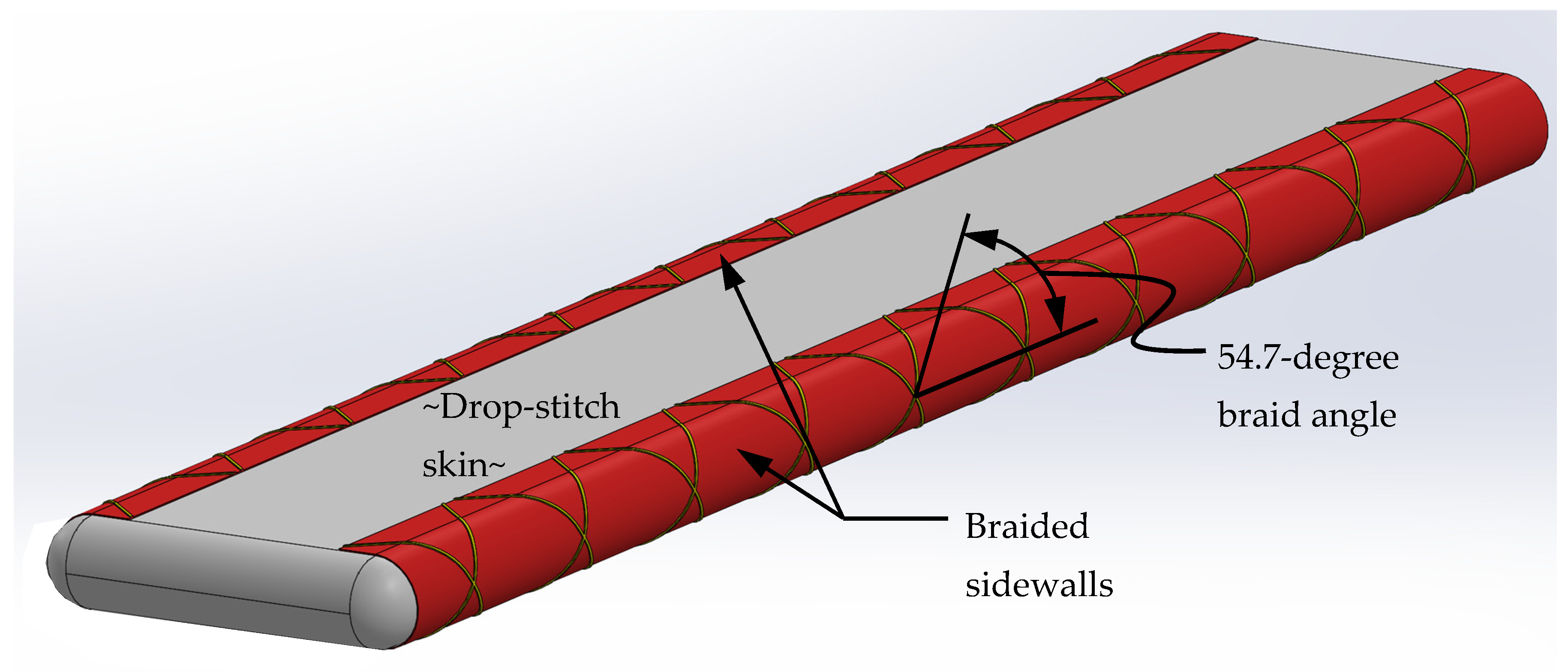

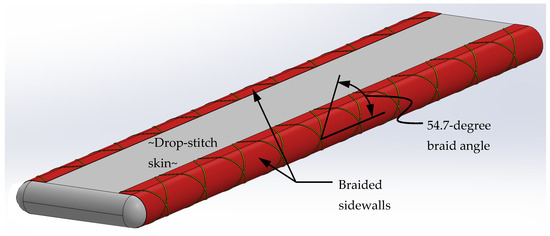

While the coating on a typical drop-stitch panel is a significant fraction of the skin thickness and therefore will contribute to panel skin moduli, the 0–90 degree woven sidewall fabric has an inherently low shear stiffness since the fibers do not align with the +/− 45 degree principal stress directions resulting from pure shear. In turn, this implies that an effective method of reducing panel shear deflections is to fabricate the sidewalls using a fabric with fiber tows oriented at angles as close as possible to +/− 45 degrees. In the present study, this was accomplished by fabricating a second drop-stitch panel with the same nominal dimensions and drop-stitch skins as the panel with woven sidewalls, but instead using a braided polyester fabric for the sidewall material as shown conceptually in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Conceptual rendering of a panel with braided sidewalls.

While the optimal braid angle is 45 degrees for shear stiffness, netting theory states that for any braid angle less than 54.7 degrees as measured from the panel longitudinal axis, the braided fabric will contract when used in a pressure vessel, and for any angle greater than 54.7 degrees, it will expand [38]. Braid contraction would tend to reduce inflation-induced longitudinal prestress in the panel skins, and any braid realignment could cause geometric distortion. To avoid these undesirable effects, a braid angle of 54.7 degrees as measured from the panel longitudinal axis was used for the sidewalls.

A 150 cm wide braided fabric sheet was produced by A&P Technologies using polyester tows with a 54.7-degree braid angle and a weight of approximately 510 g/m2. The braid material, fabric weight and coating type and weight were selected to match the woven sidewall properties. The polyester fiber specified for the braid was specifically chosen for low shrinkage (~1% hot air shrinkage at 177 degrees C vs. a more typical 10% shrinkage) to maintain the dimensions of the coated sheet and minimize fiber misalignment. A 680 g/m2 urethane coating was applied to the braided fabric sheet by the Cooley Group of Cranston, Rhode Island, USA. To verify coating-fabric bond was sufficient, the Cooley Group ran adhesion tests on two samples, and both exhibited fabric tearing or separation indicating good adhesion. While it is possible that the degree of penetration of the urethane coating into the braid differed from that in the woven sidewall, every effort was made to ensure that the only significant difference between the panels was fiber orientation.

As with the original panel, the panel with braided sidewalls was also fabricated by Kennon Products, Inc. at their facility in Sheridan, WY, USA. After receiving the coated fabric, 47 cm wide pieces of coated braid were cut by Kennon and welded to the drop-stitch skins with a 10 cm overlap in the same manner that the woven sidewalls were attached to the original panel. The dimensions of the as-fabricated braided panel for the three target inflation pressures of 34.5 kPa, 68.9 kPa and 103 kPa are given below in Table 5 and are within one percent of the dimensions of the control panel with woven sidewalls except for overall panel width at the highest inflation pressure.

Table 5.

Overall dimensions of the panel with braided sidewalls.

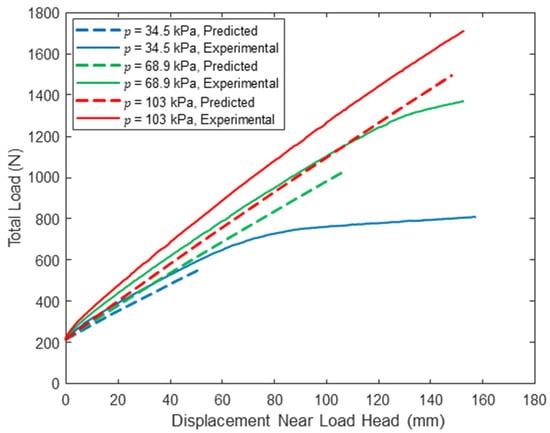

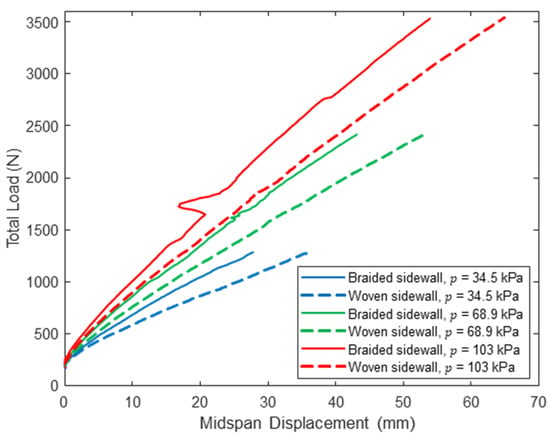

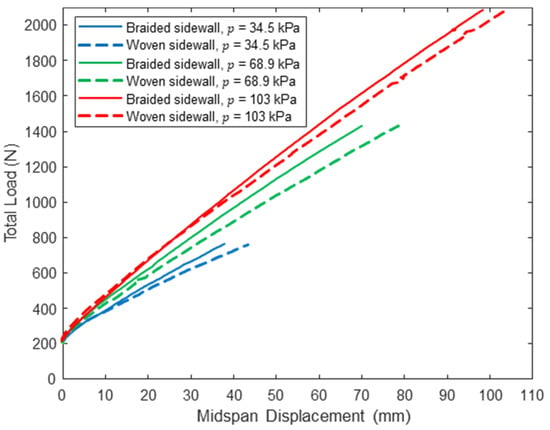

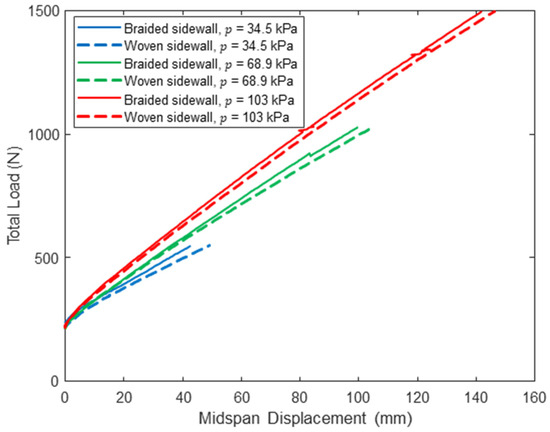

6.2. Load–Deflection Response of Panel with Braided Sidewalls

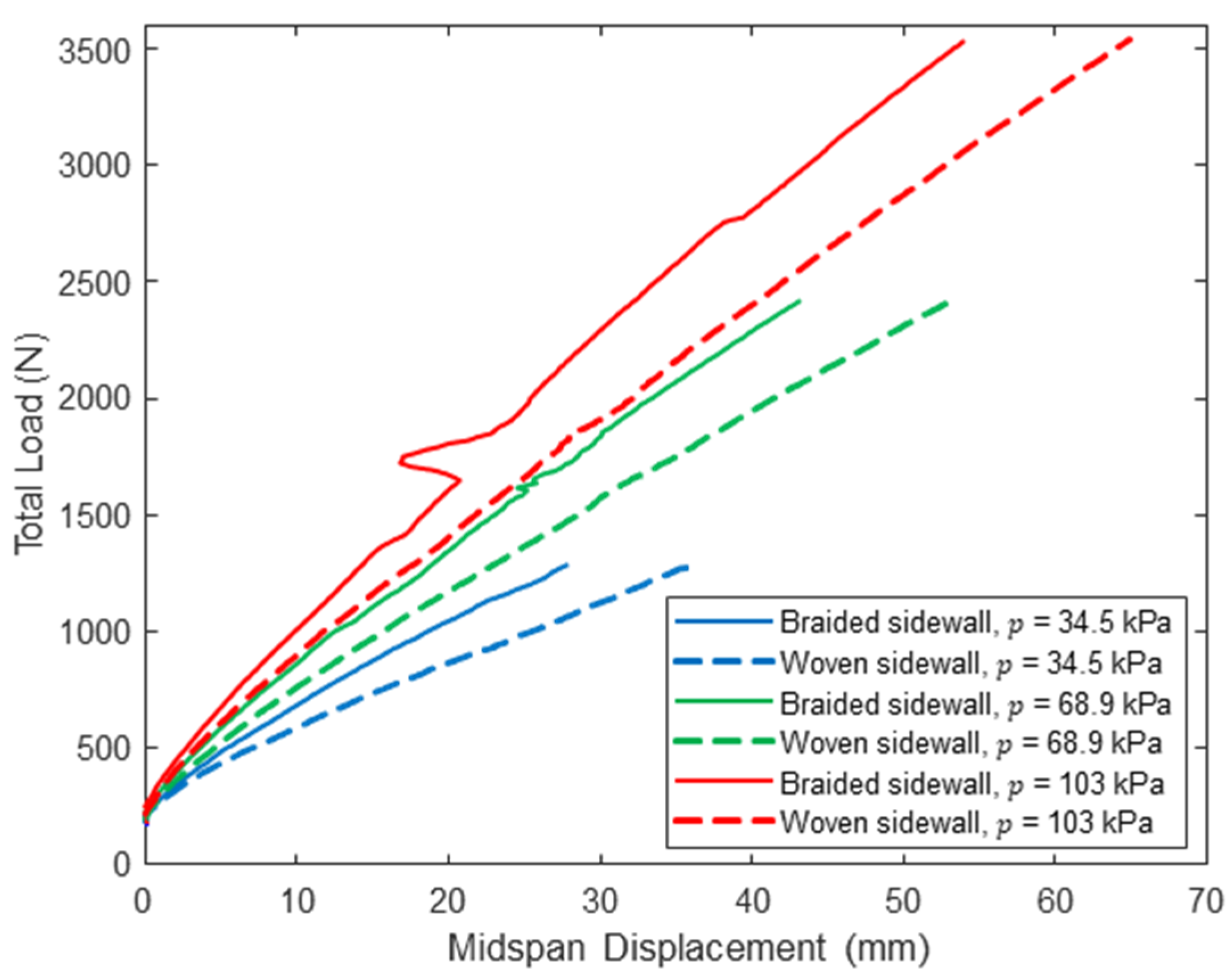

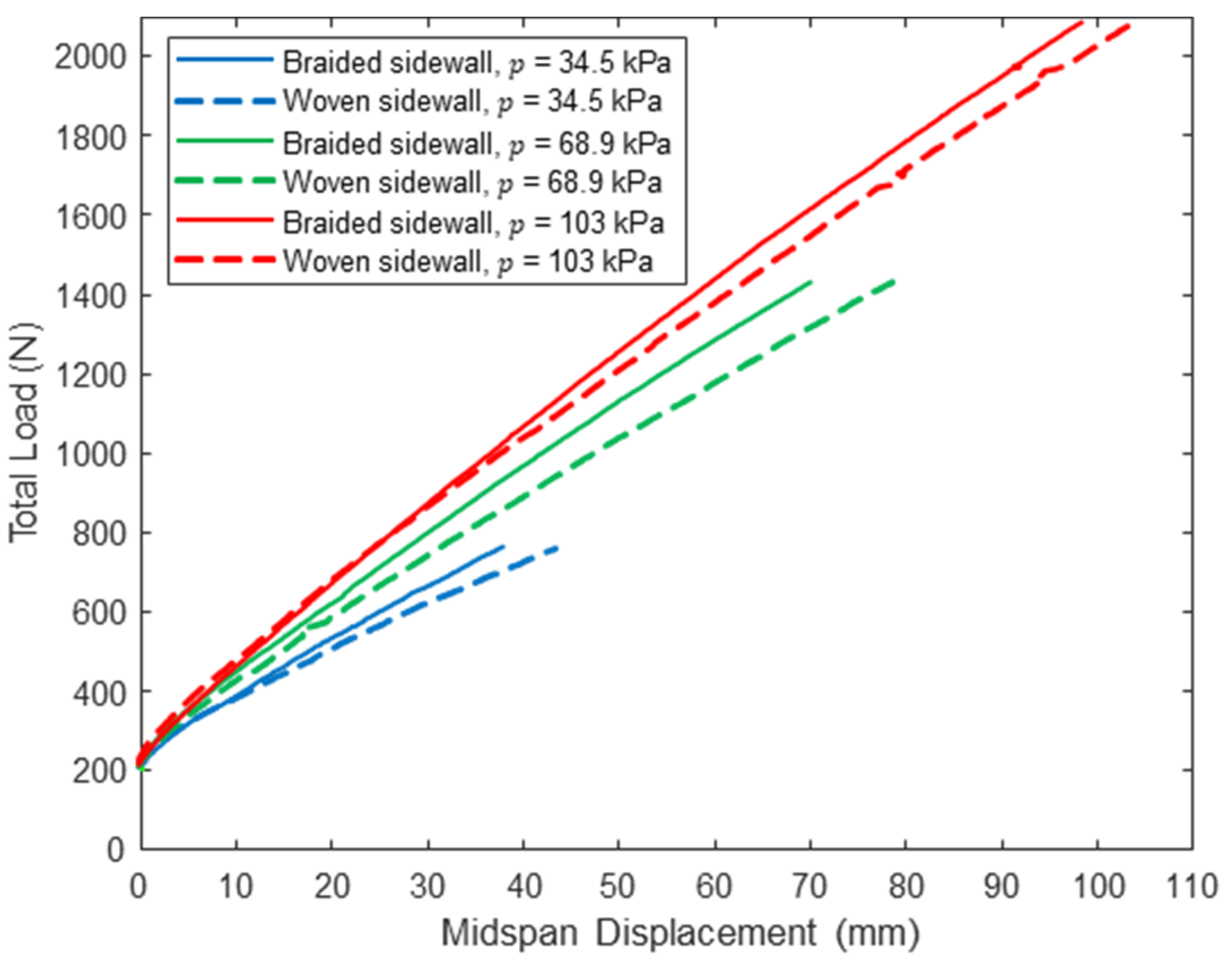

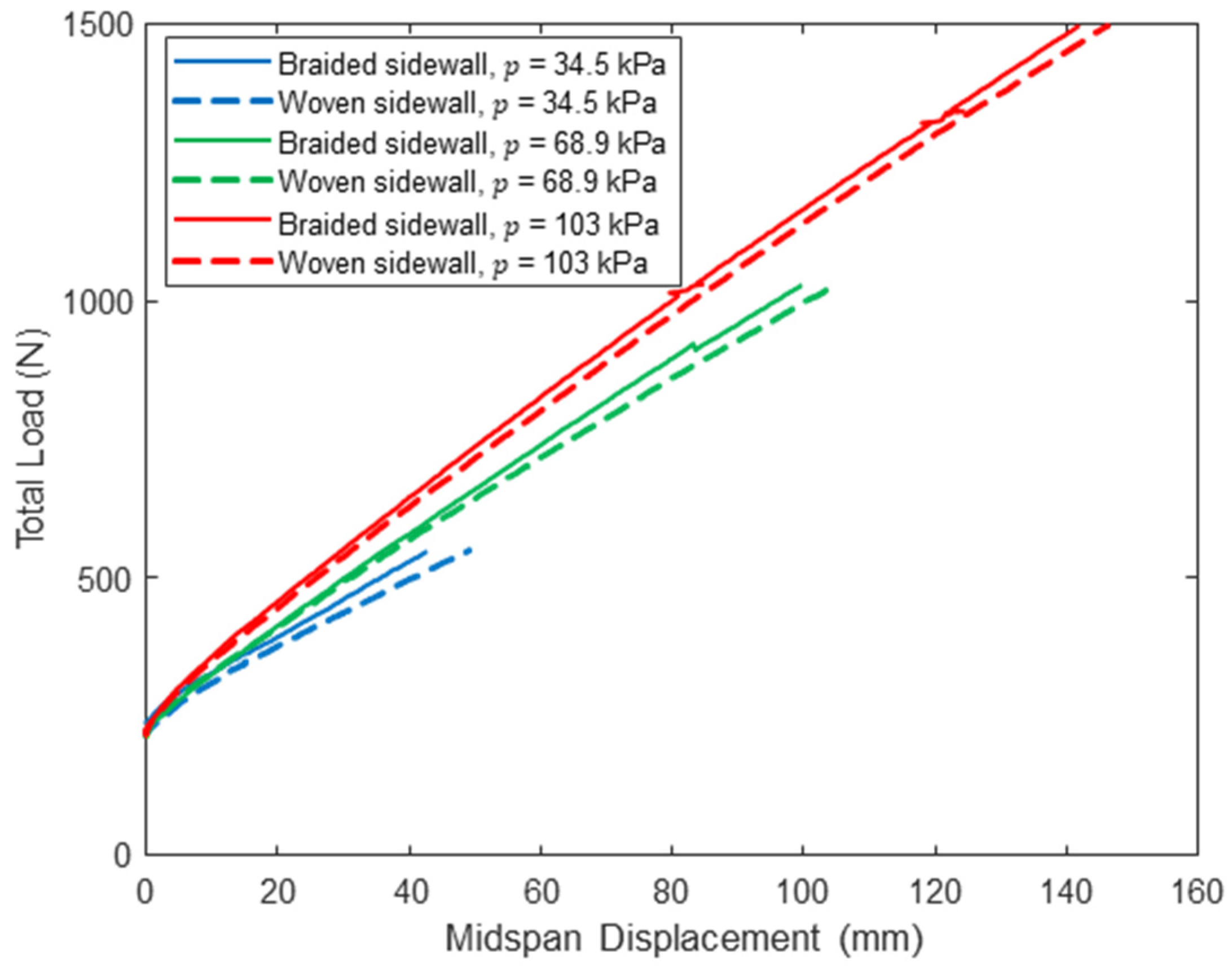

The midspan load–displacement response of the control panel with woven sidewalls and the shear-stiffened panel with braided sidewalls at loads up to are presented in Figure 15, Figure 16 and Figure 17. These results show that the braided sidewalls decrease panel deflections for all combinations of inflation pressure and span length. The impact of the braided sidewall increases as the span length is reduced, which is consistent with this configuration experiencing the highest shear deformations as discussed previously (see Table 4). The cause of the sudden jump in the load–displacement response for the 122 cm span braided panel at = 103 kPa and a displacement of about 20 mm is unknown but did not affect the displacement measured at .

Figure 15.

Pre-wrinkling midspan load–displacement response for panels with woven and braided sidewalls (L = 122 cm).

Figure 16.

Pre-wrinkling midspan load–displacement response for panels with woven and braided sidewalls (L = 213 cm).

Figure 17.

Pre-wrinkling midspan load–displacement response for panels with woven and braided sidewalls (L = 305 cm).

Table 6 provides a quantitative comparison of measured midspan displacements between the two panels at the woven sidewall panel wrinkling load . The maximum decrease in midspan displacement at is 22.3% for the shortest span at the lowest inflation pressure, and the smallest decrease is 4% for the longest span at the highest inflation pressure. This is consistent with the results presented in Table 4, which show much smaller bending deformations as span length decreases. Further, the percent reduction in deflection decreases as inflation pressure increases, which is due in part to the increase in total shear stiffness caused by pressure–volume work as discussed in Section 4.

Table 6.

Summary of measured midspan displacements and estimated reductions in shear deflections at the onset of wrinkling for panels with woven and braided sidewalls.

It is important to note that the percent reductions in midspan displacement in Table 6 will, in all cases, be less than the reductions in shear displacement, since shear displacement is only a fraction of the total deflection. To explore this further, the reduction in shear deflection is approximated as follows. Since the total midspan deflection is the sum of all deflection components, the total deflection caused by shear can be written as Equation (23).

The bending deflection of both panels is assumed to be identical for a given combination of span length and inflation pressure, which is reasonable given that the panel is dominated by the top and bottom skins which are identical for both panels. Then, a reasonable estimate for the shear deflection at any span length and pressure can be computed by substituting into Equation (23) the computed values for from Table 4 and the total measured displacement corresponding to given in the left half of Table 6 for . The resulting values of are reported for both the woven and braided drop-stitch panels in the right half of Table 6 along with the corresponding percent decrease in shear deflection enabled by the braided sidewall. The reductions in shear deflections are, as expected, universally larger than the reduction in overall midspan deflections. They are also much more consistent than the reductions in overall deflections, with maximum reductions varying from 23.5 to 27.5% for all span lengths at the lowest inflation pressure of 34.5 kPa. As with total deflections, reductions are largest for the shortest span but never drop below 10% for any combination of span length and pressure. The most reliable results are likely those of the 213 cm span for which the pressure-dependent elastic moduli were computed and the predicted and observed overall displacements at are identical. In this case, the braided sidewall produced reductions in shear deflections of between 10.5% and 23.5% with the largest difference occurring at the lowest inflation pressure. Overall, these results point to the potential for effectively stiffening overall panel load–deflection response through shear stiffening of the panel sidewalls.

7. Conclusions

This study has examined the impact of shear on the load–deformation response of drop-stitch panels loaded transversely in bending. Experimental components included both bending tests for three different span lengths and three different inflation pressures as well as torsion tests of an individual panel to determine shear stress–strain response. A mechanics-based approach to developing the nonlinear shear stress–strain relationship of the panel sidewall fabric was developed. The use of braided fabric sidewalls in lieu of conventional 0–90 woven fabric to increase shear stiffness was explored experimentally. Major conclusions of this study are as follows.

- Torsion test results indicated that coated fabric shear stiffness increases with inflation pressure. The mechanics-based method developed to derive pressure-dependent, nonlinear sidewall shear constitutive response from torsion test results is more rigorous than the technique used in the past which did not account for different panel wall thicknesses and treated response as linearly elastic.

- Overall panel load–deflection response was strongly dependent on inflation pressure. Measured load–deflection behavior was nonlinear, with increasing softening at higher loads and at lower inflation pressures that is consistent with panel wrinkling. A general approach was developed to predict panel wrinkling loads that account for the impact of nonlinear sidewall shear stress–strain response and the resulting effect of drop-stitch yarns on stresses in the panel skins. The computed wrinkling loads correspond to an experimentally observed increase in softening of panel load–deformation response, especially for lower inflation pressures.

- Analytical results indicate that shear deflections of the panels become a larger fraction of total deflection as both span-to-depth ratio and inflation pressure decrease, reaching as much as 78% of the total deflection for the shortest span and lowest pressure. Even though larger span-to-depth ratios and higher inflation pressures resulted in lower shear deflections, they were still predicted to be 43% of total deflection for the longest span and highest pressure.

- The new approach to decreasing panel shear deflections using braided fabric for the panel sidewalls that was experimentally assessed using four-point bending tests resulted in a decrease in overall panel midspan deflection at wrinkling of up to 22% for the shortest span compared to the panel with conventional woven sidewalls. While reductions in total deflection were more modest as span length and inflation pressure increased, estimated reductions in shear deflections alone ranged from 10.5 to 23.5% over the full range of pressures at the intermediate span-to-depth ratio of 12.5. These results both confirm the importance of shear deformations on panel response and indicate that panel sidewall shear stiffening is a promising technique for improving panel performance.

While this study provides valuable insight into the load–deflection response of inflated drop-stitch panels, there are several aspects of this work that can be improved and warrant additional research. First, while the torsion tests are straightforward to execute, the method used to derive the sidewall shear constitutive relationship using this test data relies on the assumption that this relationship is constant for both the panel top and bottom skins and sidewalls. While this may be reasonable for panels with relatively thick coatings and sidewalls and top and bottom skins having similar fabric architecture, this assumption breaks down when these conditions are not met. This is reinforced by the fact that while the braided panel sidewall had the same fiber volume and coating as the woven sidewall, bending tests confirmed that it had a higher shear stiffness, which can be attributed to its different fiber architecture that is optimized for shear stiffness. Further, the panel sidewalls are soft composites whose mechanical properties depend on the coating type and thickness as well as the fabric architecture, and the torsion tests cannot distinguish their relative contributions. These caveats indicate the need for more rigorous testing and analysis to determine the pressure-dependent constitutive relationship of the panel sidewalls based on the properties of both the fabric and coating. Second, while the use of braided sidewalls to increase panel stiffness was successful, the sidewall fiber volume was fixed at that of the woven panel to ensure that the only variable was fiber orientation. This indicates that greater improvements are possible if larger fiber volumes are employed in braided sidewalls, and additional research on this topic would be valuable. Third, the analyses reported here only apply up until wrinkling and response equations were developed specifically for four-point bending. While prior research has examined post-wrinkling response as well as more general loading and structural configurations through finite-element analysis, existing computational methods will need to be adapted to incorporate nonlinear shear constitutive relationships of the panel sidewall. To support more advanced analyses, it would also be valuable to use optical strain measurements or high-resolution, time-stamped photos of the panel top skin during testing to help identify precisely when wrinkling initiates.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.G.D.; methodology, W.G.D. and A.G.M.; software, W.G.D.; validation, W.G.D. and A.G.M.; formal analysis, W.G.D.; investigation, W.G.D. and A.G.M.; resources, W.G.D.; data curation, A.G.M.; writing—original draft preparation, W.G.D.; writing—review and editing, A.G.M.; visualization, W.G.D.; supervision, W.G.D.; project administration, W.G.D.; funding acquisition, W.G.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities and Development Command—Soldier Center (DEVCOM SC) under Contract Nos. W911QY-20-C-0053. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of DEVCOM SC.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be provided upon reasonable request and with approval of the research sponsor.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Wood, J.D. The flexure of a uniformly pressurized, circular, cylindrical shell. J. Appl. Mech. 1958, 25, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reissner, E. On finite bending of pressurized tubes. Trans. ASME 1959, 26, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comer, R.L.; Levy, S. Deflections of an inflated circular-cylindrical cantilever beam. AIAA J. 1963, 1, 1652–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichter, W.B. A Theory for Inflated Thin-Wall Cylindrical Beams; NASA Technical Note D-3466; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1966.

- Van Le, A.; Wielgosz, C. Bending and buckling of inflatable beams: Some new theoretical results. Thin-Walled Struct. 2005, 43, 1166–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apedo, K.L.; Ronel, S.; Jacquelin, E.; Massenzio, M.; Bennani, A. Theoretical analysis of inflatable beams made from orthotropic fabric. Thin-Walled Struct. 2009, 47, 1507–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apedo, K.L.; Ronel, S.; Jacquelin, E.; Massenzio, M.; Bennani, A. Nonlinear finite element analysis of inflatable beams made from orthotropic fabric. Thin-Walled Struct. 2010, 47, 2017–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.-T.; Thomas, J.-C.; Van Le, A. Inflation and bending of an orthotropic inflatable beam. Thin-Walled Struct. 2015, 88, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.C.; Wielgosz, C. Deflections of highly inflated fabric tubes. Thin-Walled Struct. 2004, 42, 1049–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davids, W.G. Finite-element analysis of pressurized fabric tubes including pressure effects and local fabric wrinkling. Finite Elem. Anal. Des. 2007, 44, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicker, W.J. The structural characteristics of inflatable beams. Acta Astronaut. 1993, 30, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davids, W.G.; Zhang, H. Beam finite-element for nonlinear analysis of pressurized fabric beam-columns. Eng. Struct. 2008, 30, 1969–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malm, C.G.; Davids, W.G.; Peterson, M.L.; Turner, A.W. Experimental characterization and finite element analysis of inflated fabric beams. Constr. Build. Mater. 2009, 23, 2027–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Gan, J.; Ran, X.; Liu, H.; Wu, W. Bending and wrinkling behavior of polyester fabric membrane structures under inflation. J. Ind. Text. 2022, 51, 1007S–1033S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Gan, J.; Liu, H.; Guan, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Ran, X.; Gao, Z. Experimental and numerical studies on bending and failure behavior of inflated composite fabric membranes for marine applications. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Yue, M.; Feng, S.Z.; Ngamkhhanong, C. Structural behavior of air-inflated beams. Structures 2023, 47, 1613–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Wang, N.; Wu, M. Bending tests and numerical analysis of inflatable tubes. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2025, 28, 1476–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.-T.; Ronel, S.; Massenzio, M.; Apedo, K.L.; Jacquelin, E. Analytical buckling analysis of an inflatable beam made of orthotropic technical textiles. Thin-Walled Struct. 2012, 51, 186–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Plaut, R.H.; Goh, J.K.S.; Kigudde, M.; Hammerand, D.C. Shell analysis of an inflatable arch subjected to snow and wind loading. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2000, 37, 4275–4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davids, W.G. In-plane load-deflection response and buckling of inflated fabric arches. J. Struct. Eng. 2009, 135, 1320–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.M.; Wang, G.C.; Kang, J.T.; Tan, H.F. Buckling analysis of an inflated arch including wrinkling based on pseudo curved beam model. Thin-Walled Struct. 2018, 131, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Li, X.; Wang, W.; Xue, S.; Dou, F. Bending performance of highly pressurized inflatable membrane arches. Eng. Struct. 2025, 328, 119716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Li, Q.; Zhang, D.; Gong, J. Structural behavior of an air-inflated fabric arch frame. J. Struct. Eng. 2016, 142, 04015108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Guo, X.; Gong, J.; Qing, G.; Li, Z. Experimental deployment behavior of air-inflated fabric arches and a full-scale arch frame. Thin-Walled Struct. 2016, 103, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davids, W.G. Behavior of inflatable drop-stitch panels subjected to bending and compression. Materials 2023, 16, 6919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wielgosz, C.; Thomas, J.-C. Deflections of inflatable fabric panels at high pressure. Thin-Walled Struct. 2002, 40, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallaro, P.V.; Hart, C.J.; Sadegh, A.M. Mechanics of air-inflated crop-stitch fabric panels subject to bending loads. In Proceedings of the ASME 2013 International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition, San Diego, CA, USA, 13–21 November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Davids, W.G.; Waugh, E.; Vel, S. Experimental and computational assessment of the bending behavior of inflatable drop-stitch fabric panels. Thin-Walled Struct. 2021, 167, 108178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacorre, P.; Van Le, A.; Bouzidi, R.; Thomas, J.-C. A plate theory for inflatable panels. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2022, 256, 111969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, T.; Pandey, A.; Fontaine, D.; Matos, H.; Shukla, A. Projectile impact behavior of drop-stitch inflatables. Eur. J. Mech.-A/Solids 2025, 112, 105644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabche, J.P.; Peterson, M.L.; Davids, W.G. Effect of inflation pressure on the constitutive response of coated woven fabrics used in airbeams. Compos. Part B Eng. 2011, 42, 526–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlone, A.G. Testing and Analysis of Shear Reinforced, Inflatable Drop-Stitch Panels in Bending. Master’s Thesis, Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Maine, Orono, ME, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Sheng, L.; Fei, S. Experimental investigation of the engineering constants of architectural coated fabric under uniaxial and biaxial loading. J. Eng. Fibers Fabr. 2024, 19, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horiashchenko, S.; Musial, J.; Horiashchenko, K.; Polasik, R.; Kalaczyński, T. Mechanical properties of polymer coatings applied to fabric. Polymers 2020, 12, 2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Sheng, L.; Xu, H. A review of advanced coated fabric used in membrane structures: Test methods, mechanics properties and constitutive relationships. Structures 2024, 69, 107501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, P.; Clifford, M.J.; Long, A.C. Shear characterisation of viscous woven textile composites: A comparison between picture frame and bias extension experiments. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2004, 64, 1453–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gere, J.M.; Timoshenko, S.P. Mechanics of Materials, 2nd ed.; PWS Engineering: Boston, MA, USA, 1984; p. 741. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J.T.; Gibson, A.G. Composite angle ply laminates and netting analysis. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2002, 458, 3079–3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.