Abstract

Polychrome sculptures are complex, multilayered artifacts that embody the intersection of artistic craftsmanship, material science, and cultural heritage. Over the past two decades, the study of material identification in polychrome sculptures has shown marked interdisciplinary development, driven by advances in analytical technologies that have transformed how these objects are studied, enabling high-resolution identification of pigments, binders, and structural substrates. This review synthesizes key developments in the identification of polychrome sculpture materials, focusing on the integration of non-destructive and molecular-level techniques such as XRF, FTIR, Raman, LIBS, GC-MS, and proteomics. It highlights regional and historical variations in materials and craft processes, with case studies from Brazil, China, and Central Africa demonstrating how multi-modal methods reveal both technical and ritual knowledge embedded in these artworks. The review also examines evolving research paradigms—from pigment identification to stratigraphic and cross-cultural interpretation—and discusses current challenges such as organic material degradation and the need for standardized protocols. Finally, it outlines future directions including AI-assisted diagnostics, multimodal data fusion, and collaborative conservation frameworks. By bridging scientific analysis with cultural context, this study offers a comprehensive methodological reference for the conservation and interpretation of polychrome sculptures worldwide.

1. Introduction

Polychrome sculptures are complex, multilayered artifacts that embody the intersection of artistic craftsmanship, material science, and cultural heritage. Whether in the form of Chinese clay, wood, and stone sculptures or Western painted stone, polychrome wooden carvings, and terracotta works, these artifacts reflect the evolution of artistic techniques and religious expression through their distinctive materials and craftsmanship [1,2]. Beyond their ritual and aesthetic significance, polychrome sculptures represent a convergence of technological innovation, material science, and cross-cultural interaction.

Over the past two decades, the study of material identification in polychrome sculptures has shown marked interdisciplinary development, driven by the rapid advancement of scientific techniques for heritage analysis. Researchers from art history, chemistry, and conservation science have applied a range of modern analytical tools to uncover the complex stratigraphy and material systems of these artifacts [3,4]. Frequently used technologies include Raman spectroscopy, Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray fluorescence (XRF), X-ray diffraction (XRD), laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS), as well as multispectral and microscopic imaging. These techniques offer high sensitivity and non-destructive capabilities for identifying pigments and inorganic mineral components [5,6].

Meanwhile, significant advances have also been made in the analysis of organic materials. Molecular-level techniques such as gas/liquid chromatography (GC-MS, LC-MS) and proteomics now allow researchers to identify complex binding media within paint layers—especially animal glue, lipids, plant gums, and natural resins [7,8]. For example, Lluveras-Tenorio et al. (2017) employed multi-omics analysis to reveal the stratigraphy and organic adhesives in the painted layers of the Bamiyan Buddhas, providing critical insights into their reconstruction and conservation [9]. Microorganisms are among the main factors responsible for the alteration of stone substrates, causing chromatic changes, weakening of the mineral matrix, and biodeterioration. In the context of polychrome stone artworks, microbial colonization has also been shown to contribute to the degradation of paint layers, highlighting the need for targeted microbiological investigations [10].

Material identification plays a vital role not only in reconstructing ancient technological recipes but also in informing conservation and restoration strategies [11]. The analysis of pigments, fillers, and binding agents across different historical periods and regions enables researchers to trace the evolution of craft techniques and the transmission of materials and ideas across cultures [12,13]. Additionally, material characterization helps diagnose degradation mechanisms and informs targeted conservation measures, such as humidity control, structural reinforcement, and anti-fungal treatments. Increasing attention has been paid to multi-technique integration and data fusion in recent years [14,15]. As a result, material identification has become a central link between art-historical interpretation, material science, and conservation practice. It not only unveils the technical logic behind historical polychrome sculpture production but also establishes a methodological foundation for modern conservation—one that is increasingly driven by intelligent and multimodal approaches [1,6].

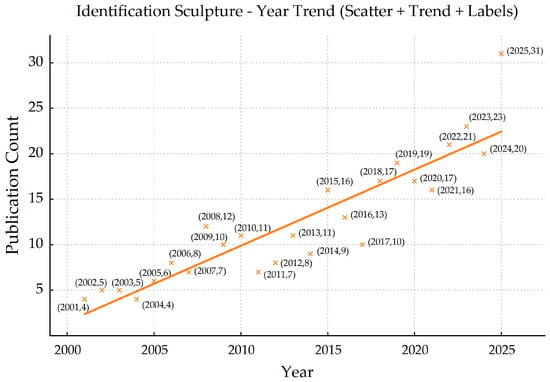

A bibliometric search (accessed on 20 September 2025) on the Web of Science using the keywords “identification” and “sculpture” shows that, over the past twenty years, research in the identification of sculpture materials and technologies (particularly for polychrome works) has steadily grown in both volume and diversity. Prior to 2000, the field was dominated by scattered case studies focused on preliminary material analyses of museum objects. After 2000, with the wider adoption of Raman, XRF, FTIR, GC–MS, and 3D imaging, the research output gradually increased, forming a more systematic and interdisciplinary domain. A trend analysis of publications (Figure 1) from 2000 to 2025 reveals a steady upward trajectory despite low annual publication counts, indicating that “material and structural identification of sculptures” has become a steadily expanding subfield within heritage science.

Figure 1.

Annual publication trend (2000–2025) on material identification in polychrome sculpture studies based on Web of Science data.

Geographically, while a significant proportion of published research originates from countries such as China, the United States, the United Kingdom, Italy, France, and Germany, increasing contributions are also emerging from regions such as Japan, South Korea, Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America—reflecting a gradual diversification of the field. While Chinese scholars have produced notable results on Buddhist cave sculptures, wooden figures, and tomb sculptures, it is important to recognize that these findings represent one part of the broader East Asian context. Parallel research efforts have also emerged in Japan and South Korea, especially in the study of lacquered and wooden Buddhist statuary, as well as Southeast Asia, where polychrome wooden and stucco sculptures in Myanmar and Thailand have drawn increasing analytical interest [16,17,18]. European teams focus on Greco-Roman and medieval sculptures, investigating the relationships between painted surfaces, construction techniques, and aging mechanisms [2,19]. In North America, major museums such as The J. Paul Getty Museum and The Metropolitan Museum of Art function as key platforms for materials research and conservation studies. For instance, recent polychromy research conducted at The Met, including a multidisciplinary investigation of an Attic funerary stele, highlights the role of museum-based research in advancing technical art history and materials analysis [20]. Likewise, the Getty Conservation Institute contributes to conservation science through systematic studies of material characterization and preservation methodologies, reinforcing the Getty’s position as an international research hub [21]. Additionally, studies from regions such as Israel, Egypt, and South America have expanded the diversity of perspectives—offering insight into polychromed limestone, Coptic wood, and colonial church sculpture. Although less prevalent, research from Latin America [22] and the Middle East has contributed valuable insights, particularly in the analysis of church sculptures and polychromed limestone carvings. Collectively, these studies have established an international research network centered around East Asia and Europe and extending into the Americas and the Middle East.

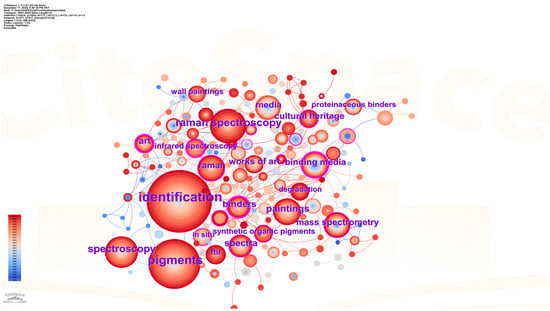

In terms of research themes and methodological paths (Figure 2), a CiteSpace co-occurrence analysis reveals “identification” as the central keyword, with high-frequency terms such as “pigments,” “Raman spectroscopy,” and “microscopy.” This indicates that research has primarily focused on three areas: pigment identification, binder analysis, and the reconstruction of structural and technological systems. In pigment studies, Franquelo et al. (2011) and Cosano et al. (2019) used micro-Raman spectroscopy to reveal multistage painting processes [23,24]. In binder analysis, Kuckova et al. (2013) distinguished between original and overpainted protein-based systems using MALDI-TOF and mass spectrometry [25]. In structural studies, Shen et al. (2022) analyzed mud sculptures at Qinglian Temple, revealing composite systems of plaster and pigment layers [26]. Overall, the focus has shifted from simply identifying “what the materials are” to a more holistic understanding of “how they were made” and “how they have aged.”

Figure 2.

Keyword co-occurrence network based on publications related to material identification in sculpture studies (2000–2025).

This paper aims to provide a comprehensive review and synthesis of research on material identification in polychrome sculptures over the past two decades. It focuses on three key objectives: (1) to survey current analytical techniques and their applications in the study of pigments, binders, and structural layers; (2) to compare cross-cultural approaches in terms of research objects, methods, and theoretical frameworks, highlighting regional craft traditions and complementary analytical perspectives; and (3) to identify current challenges, including difficulties in identifying organic binders, lack of standardization in non-invasive diagnostics, and insufficient depth of interdisciplinary integration. The paper concludes with a discussion of future directions such as AI-assisted analysis, shared data platforms, and digital reconstruction. By critically assessing existing findings, this review seeks to provide a comprehensive scientific and methodological reference for future conservation and materials research, thereby promoting deeper integration between traditional craft studies, conservation science, and digital heritage initiatives.

2. Materials and Craftsmanship of Polychrome Sculptures

2.1. Material Composition

Polychrome sculptures typically consist of a multilayered structure combining inorganic and organic materials, including the core body, preparatory layers, painted and gilded surfaces, and protective coatings. This stratified organization reflects both functional requirements and artistic conventions, as schematically illustrated by representative polychrome sculptural surfaces (Figure 3) [27]. The structural core determines mechanical behavior and shaping techniques: East Asian examples often employ clay or wood, while Western traditions favor wood, limestone, and marble, with regional variants such as colored terracotta and reliefs [27,28]. For instance, analysis of Confucius Temple murals in Qufu shows compatibility between softwood substrates and overlying lime layers [29]. Baroque sculptures in Portugal and Brazil used spruce or pine wood with gypsum- or carbonate-based grounds for structural rigidity [30,31]. In limestone sculptures, complex interfaces between stone and polychrome layers influence both deterioration and restoration strategies [32]. In many Chinese and European polychrome sculptures, additional internal reinforcements—such as plant fibers, pulp inclusions, or metal joints—are incorporated, forming hybrid support systems that enhance structural stability while accommodating thick decorative layers.

Figure 3.

Representative polychrome sculptural surface showing the layered material composition, including substrate, preparatory layers, painted areas, and gilded elements [27].

Preparatory layers (gesso or ground) serve to level surfaces and enhance pigment adhesion. Western examples use gypsum and calcium carbonate mixtures, sometimes enhanced with clays or proteins to improve workability. In China, traditional lime layers contain kaolinite, calcite, gypsum, and plant fibers, offering both reflectivity and crack resistance [29]. The visual stratification visible in Figure 3 highlights the close relationship between substrate materials, preparatory layers, and polychrome finishes, underscoring the material logic underlying polychrome sculptural production across different cultural contexts.

Pigments are predominantly mineral-based, with some organic dyes. Studies of 18th-century Baroque icons in Brazil and Portugal report lead white, cinnabar, red ochre, azurite, and malachite as dominant. Renaissance terracotta reliefs feature both historical and modern pigments like cobalt blue and barium sulfate from restoration phases [28]. Lead white is ubiquitous and also contributes to radiocarbon-based dating [32]. Organic colorants such as indigo and alizarin have been identified even in micro-samples through Raman and mass spectrometry [33].

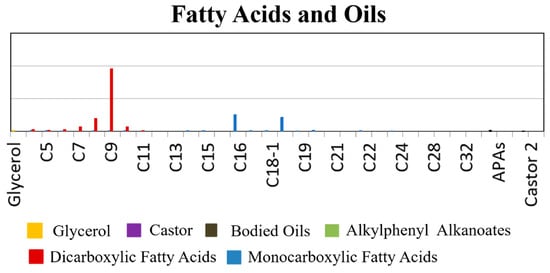

Binding media connect pigments to the substrate and significantly affect optical, mechanical, and aging behavior. Italian studies report frequent use of animal glue and drying oils in complex media systems [28]. In Chinese contexts, animal glue, plant gum, and tung oil are used for paint mixtures, gilding, and sealing [29]. Recent Py-GC/MS evidence further demonstrates that these binders often coexist at the micro-scale: fatty-acid profiles obtained from polychrome architectural paintings reveal the simultaneous presence of proteinaceous glue and heat-bodied tung oil, as indicated by the distribution of mono- and dicarboxylic fatty acids (Figure 4). In Papua New Guinea, FTIR and Raman revealed micro-scale coexistence of protein, resin, and polysaccharides [34]. European medieval works also show layered use of protein and oil binders [35].

Figure 4.

Relative concentrations of fatty acids identified in polychrome paint binders by Py-GC/MS, showing the coexistence of protein-based glue and heat-bodied tung oil [29].

Modern conservation materials now form part of this system. Han et al. (2024) evaluated common consolidants (AC33, B72, FKM, FEVE), showing that resin type impacts gloss, color, and weathering [36]. Case studies also warn against interface incompatibility between old protein-oil systems and polymer treatments, which may accelerate flaking or cracking [31,37]. Taken together, the compositional patterns illustrated in Figure 4 underline that polychrome sculptures should be understood as chemically composite systems rather than single-binder structures, revealing regional material traditions as well as layered historical phases that form the basis for structural analysis and deterioration studies.

2.2. Crafting Process and Stratigraphy

Polychrome sculptures follow a generally consistent yet regionally distinct stratigraphic process: core construction → ground layer → paint layer → gilding → protective varnish. In many East Asian traditions, this sequence may additionally include one or multiple paper or fiber-rich interlayers applied between paint campaigns, forming a complex composite stratigraphy. The choice of core material reflects regional and cultural practices—for example, clay and wood are commonly used in Chinese sculptures, while stone and terracotta are typical in many European works. Structural preparation typically includes shaping, smoothing, and infill steps suited to the core material. In Europe, medieval wooden sculptures often employed joinery and patching to ensure stability [38]. In China, techniques such as mixing clay with straw, fiber, or pulp were used to enhance crack resistance in Ming–Qing period figures [39]. Microscopic evidence further indicates that paper layers composed of bast fibers were deliberately introduced as intermediate strata, contributing to both surface regularization and repainting adaptability (Figure 5). Ground layers (gesso) serve as a preparatory coating to level surfaces and absorb subsequent paint layers [40].

Figure 5.

Morphology of paper fibers observed in polychrome sculpture stratigraphy, illustrating the use of ramie-based paper layers as intermediate strata within paint systems [39].

Paint layers reflect both aesthetic and material diversity. Chinese sculptures use mineral pigments with multilayer washes and wet-on-wet techniques; Western pieces mix mineral and organic pigments and employ tempera or oil binders to enhance color depth [35]. Stratigraphic observations combining fiber morphology and pigment layering demonstrate that repainting campaigns often reused paper interlayers as a structural and visual buffer, while stratigraphic analysis via microscopy and spectroscopy reveals overpainting and repair stages.

Gilding processes often follow a standard sequence of ground → bole → adhesive → gold leaf. European works use red clay bole, while Chinese methods rely on oils and animal glues [41,42]. OCT (optical coherence tomography) has been used to study gilding layers in high detail [43]. Final coatings of resin, oils, or wax serve protective and aesthetic functions, though subject to yellowing and degradation, prompting increasing research on their long-term compatibility. The multilayered crafting process of polychrome sculptures—including material choices, layer thickness, and application technique—determines their visual quality, mechanical stability, and aging behavior. Understanding this stratigraphy is essential for reconstructing technical workflows and guiding scientific conservation.

3. Analytical Techniques for Material Identification

3.1. Non-Destructive and Micro-Destructive Methods

Polychrome sculptures are often characterized by highly complex stratified structures and fragile materials, frequently housed in diverse environments and subject to strict mobility restrictions. Consequently, material identification prioritizes non-destructive testing (NDT) and micro-destructive testing (MDT) techniques. Spectroscopic analysis and imaging visualization form the foundational categories of these approaches: the former targets molecular and elemental composition, while the latter reveals structural stratigraphy and internal features across spatial scales. Combined, these methods enable comprehensive “surface-to-core” diagnostics of polychrome sculptures [3,44].

3.1.1. X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) and Related X-Ray Techniques

X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) is one of the most widely employed non-destructive techniques in the analysis of polychrome sculptures due to its in situ, rapid, and sampling-free nature. By detecting characteristic elements such as Pb, Hg, Cu, Fe, and Au, XRF facilitates qualitative and semi-quantitative identification of inorganic pigments like cinnabar, lead white, azurite, malachite, ochres, and metallic gilding [45]. For example, in the study of the red jaguar sculpture from Chichen Itza, portable XRF was used to detect hematite and cinnabar in the red coating and to identify the chemical composition of green jade inlays—enabling material sourcing without physical sampling [46].

With the development of portable XRF (pXRF) and advancements in macro XRF imaging (MA-XRF), the application of XRF has expanded significantly. While pXRF enables truly field-operable analysis suitable for archeological sites, religious spaces, and museum galleries, MA-XRF generally remains a lab-based technique due to its equipment size and operational requirements. pXRF has been effectively used to study Renaissance terracotta sculptures and Central European religious statuary, revealing overlapping materials from multiple restoration phases [44,45]. Multi-scale integration with μ-XRF and micro-XRD allows for simultaneous acquisition of crystalline structures and micro-elemental mapping in a single cross-section, thus deconstructing complex layered coatings post-restoration [3]. Recent studies have also explored the application of micro-XRF imaging on enamel and porcelain miniature portraits, suggesting its adaptability to small-scale sculptures for “elemental imaging” of surface ornamentation [47].

3.1.2. Raman Spectroscopy and Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS)

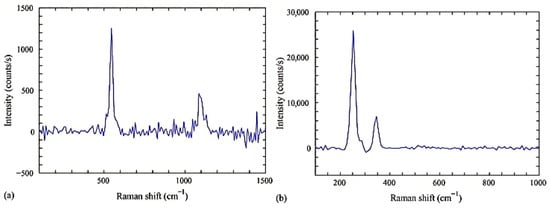

Raman spectroscopy is central to identifying inorganic pigments, offering highly selective “molecular fingerprint peaks” particularly effective for distinguishing closely related minerals. such as hematite–ochre, ultramarine–lazurite, and malachite–green pigments [48]. Micro-Raman spectroscopy enables identification at microscopic sites, distinguishing original polychromy from modern overpainting. For instance, a 14th-century polychrome wooden sculpture was found to have modern synthetic pigments in some areas, overturning the assumption of complete original paint preservation [23]. A representative example is provided by Raman spectra of original blue and red paint layers in a Renaissance polychrome sculpture, where lazurite and vermilion were unambiguously identified through their diagnostic bands (Figure 6), allowing clear differentiation between original pigment layers and later overpainting campaigns. In studies of the Lamentation of Christ in Barletta and the Spanish Annunciation ensemble, Raman spectroscopy identified pigment layering sequences involving cinnabar, lead white, azurite, and anatase-phase titanium dioxide, elucidating polychrome practices from the medieval to modern periods [24,49].

Figure 6.

Raman spectra of blue (lazurite) (a) and red (vermilion) (b) pigments from original paint layers of a Renaissance polychrome sculpture, illustrating the diagnostic fingerprint peaks used for pigment identification [49].

Raman has also been applied to identify weathering salts and secondary minerals on stone sculpture surfaces, shedding light on environmental impacts and salt-induced deterioration [50]. Combined micro-Raman and FTIR have been used to analyze stratigraphy and conservation materials in works like Blessing Christ, reconstructing repainting history and material transitions [51]. For organic dyes and trace pigments, Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) provides heightened sensitivity and selectivity, making it a key method for detecting organic colorants, such as lake pigments and dyes, as well as inks used in both painting and sculpture [52].

3.1.3. FTIR and Its Spatial Extensions (FTIR/ATR-FTIR/Nano-FTIR)

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) is essential for detecting organic binders, coatings, and some mineral materials. Early cross-sectional studies of altarpieces and sculptures employed FTIR to differentiate proteinaceous glues, oils, and waxes, contributing to the establishment of reference spectral libraries [53,54]. ATR-FTIR allows for point analysis on small, uneven surfaces without the need for ultra-thin sectioning, offering robust spectra even on complex three-dimensional forms [55].

FTIR has also been used to study the degradation of polyurethane and other synthetic resins on outdoor sculptures, informing the selection of future conservation materials [56]. On the nanoscale, nano-FTIR extends spatial resolution to sub-micrometer levels. Recent work on Central African wood carvings used this technique to identify natural resins, vegetable oils, waxes, and carbonaceous layers—revealing that many traditional “patinas” are actually multi-layered applications with smoke residues [57]. Coupling FTIR with fluorescence lifetime imaging has even supported the surface assessment of Michelangelo’s David, showcasing its utility in large-scale sculpture conservation [58].

3.1.4. Reflectance Spectroscopy (FORS and UV–Vis–NIR Reflectance)

Reflectance spectroscopy, particularly Fiber Optic Reflectance Spectroscopy (FORS), constitutes a distinct and fully non-invasive approach for the identification of pigments and colorants on polychrome surfaces. Operating typically in the UV–Vis–NIR range, FORS identifies both inorganic and organic pigments through characteristic absorption features and spectral inflection points, without requiring physical contact or sampling [59].

FORS has been widely applied to polychrome sculptures, wall paintings, and painted architectural surfaces, especially in cases where sampling is prohibited. For example, the construction of a FORS spectral database of 54 historical pigments demonstrates the effectiveness of FORS for non-invasive pigment identification across diverse media and binder types, facilitating in situ analysis of complex painted surfaces [60]. Unlike point-based UV–Vis absorption measurements, reflectance spectroscopy allows in situ analysis of curved and textured surfaces, making it particularly suitable for sculptural polychromy.

3.1.5. LIBS and UV–Vis Spectroscopy

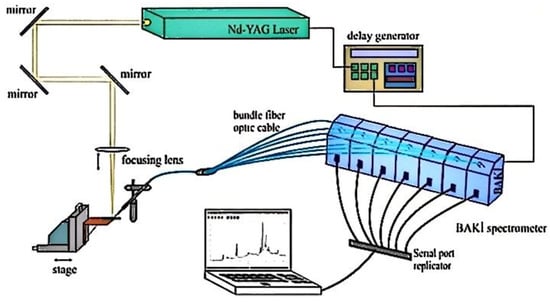

Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) is a micro-destructive technique that enables simultaneous multi-element detection and depth profiling. It is particularly effective on irregular surfaces and composite painted layers. The basic configuration of a LIBS system—comprising a pulsed laser source, focusing optics, plasma emission collection, and multi-channel spectrometers—allows rapid in situ elemental analysis with minimal material loss (Figure 7) [61]. LIBS can distinguish between original and overpainted layers and reveal elemental gradients across polychrome strata [62]. Combined with spectral databases and multivariate analysis, it helps trace painting techniques and deterioration mechanisms.

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of a typical LIBS experimental system, illustrating laser excitation, plasma generation, and emission signal collection for elemental analysis of cultural heritage materials.

UV–Vis spectroscopy identifies organic dyes, varnishes, and aging products through their optical absorption profiles and is especially useful for evaluating yellowing, oxidation, and the presence of modern restoration materials. Its results are often corroborated with FTIR and GC–MS analyses to achieve a comprehensive characterization of both inorganic and organic components within polychrome surfaces [53,54].

3.1.6. Multispectral Imaging, CT, and 3D Scanning

Multispectral imaging (MSI) and hyperspectral imaging (HSI) have become essential tools for the non-invasive investigation of polychrome surfaces, particularly when physical sampling is not possible. MSI captures reflectance data in discrete spectral bands (UV, VIS, NIR), enabling visualization of underdrawings, overpainting, and surface alteration patterns. HSI acquires continuous spectral information across hundreds of narrow bands, allowing precise discrimination and mapping of pigments based on diagnostic spectral signatures [63,64].

Recent applications of MSI and HSI to polychrome sculptures and painted reliefs have demonstrated their effectiveness in identifying restoration phases, pigment heterogeneity, and stratigraphic complexity, particularly when combined with reference spectral libraries and multivariate classification methods. Although augmented reality (AR) techniques have been explored for visualization and communication purposes in conservation workflows [63], they are not directly involved in material identification and are therefore not further discussed here.

Three-dimensional imaging technologies—such as structured light scanning, photogrammetry, and laser triangulation—enable high-resolution surface documentation, capturing tool marks, ornamentation, and deformation. These datasets provide geometric frameworks for co-registering spectral and chemical imaging results [65]. Computed tomography (CT and μ-CT) further allows internal examination of sculptures, revealing wood grain, joints, cavities, and insect damage without physical intrusion. In particular, automated texture analysis of CT datasets has been successfully applied to identify wood species used in traditional Japanese sculptures, demonstrating the potential of CT-based approaches for structural and material characterization of organic-core polychrome artifacts [66]. Recent studies combining CT imaging with machine learning have further expanded the applicability of internal imaging techniques in heritage science [66].

3.1.7. Microscopy and Multi-Modal Microanalysis

Optical microscopy and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) remain foundational tools for analyzing layer stratigraphy and pigment morphology. Studies of sculpture cross-sections have used SEM-EDS to characterize pigment grain shape, size distribution, and elemental composition, aiding in understanding pigment mixing and application techniques [56,67]. In studies of murals and sculptures from Liao dynasty temples, micro-regional observation and elemental mapping revealed relationships between ground layer degradation, salt crystal precipitation, and surface encrustation—providing evidence for the coupling of material pathology with environmental conditions [68].

3.2. Chemical and Biomolecular Approaches

Organic components in polychrome sculpture materials—such as animal glue, plant gum, oils, resins, waxes, and their degradation products—play crucial yet often overlooked roles. They influence pigment adhesion, mechanical behavior, surface gloss, and deterioration processes. Given their susceptibility to environmental degradation, conventional non-destructive spectroscopy may not yield definitive identifications. Therefore, high-sensitivity molecular-level techniques such as GC-MS, Py-GC-MS, LC-MS, and proteomics are increasingly indispensable [54,69].

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) remains a classic method for analyzing fatty acids, terpenoids, and long-chain hydrocarbons in organic coatings and binders. Characteristic molecular markers—such as palmitic/stearic acid ratios, azelaic acid generation, or abietic acid derivatives—help distinguish between drying oils, natural resins, and waxes [53,54]. While not always definitive, GC-MS can contribute to hypotheses about the relative sequence of application for wax layers, varnishes, and resin coatings in multi-material sculptures, particularly when supported by stratigraphic or imaging data [68].

Pyrolysis GC-MS (Py-GC-MS) complements traditional GC-MS by thermally breaking down cross-linked and insoluble organic materials, allowing the detection of aged, degraded, or synthetic polymers that resist solvent extraction. It is particularly effective for differentiating complex mixtures in restoration varnishes and historical coating layers [69]. Unlike GC-MS, which requires sample pre-treatment and is limited to soluble compounds, Py-GC-MS provides a more holistic profile but is destructive and often harder to interpret due to thermal artifacts.

For example, in studies of Liao-dynasty murals, Py-GC-MS detected plant oils and animal glue coexisting in the ground and varnish layers, aiding comparative analysis across similar-period sculptures [68]. More recently, Py-GC-MS was used to differentiate between insect-derived dyes such as lac and cochineal in ancient Greek polychromy [70], demonstrating its potential for dye and pigment identification in sculpture contexts.

To strengthen the comprehensiveness of this review, we have expanded the bibliography related to mass spectrometry, including recent works that analyze lac, shellac, and proteinaceous binders. In addition, immunoassays—such as ELISA—are increasingly used to detect specific proteins (e.g., collagen, casein) and may complement MS approaches in identifying binding media at the molecular level, particularly in extremely limited or degraded samples.

Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) is better suited to identifying polar, thermally unstable, or high-molecular-weight organics such as plant-based dyes and polysaccharide gums. Though less common in sculpture analysis, LC-MS has seen widespread use in paintings and textiles and holds promise for future applications in characterizing organic colorants and adhesives embedded in polychrome statuary [53,69].

Proteomics, utilizing enzymatic digestion followed by LC–MS/MS, has emerged as a transformative tool for identifying species-specific proteins in binders. It enables the differentiation between hide glue, bone glue, fish glue, and even individual animal origins [71]. Proteomic studies have, for instance, identified bovine collagen in 3500-year-old wooden artifacts from the Xiaohe Tomb (Xinjiang) [72], and successfully distinguished egg yolk, egg white, and mixed glue–oil systems in medieval European sculptures. Combined with FTIR or GC-MS, proteomics provides high-resolution insight into the chemical-biological composition of paint systems and helps differentiate sacrificial coatings from modern restorations, as shown in African wood carvings [73].

In addition to identifying materials, advanced analytical techniques aid in tracing material provenance. Although rare in sculpture literature, stable isotope analysis—including Pb, Sr, and Nd isotopes—has proven effective in sourcing pigments, clay, and stone, offering potential for future application [46,74]. Meanwhile, elemental mapping via SEM–EDS, µ-XRF, and MA-XRF is widely applied to visualize gilding sequences (e.g., ground → bole → gold leaf → varnish) and localize restoration interventions across sculpture surfaces [3,47].

Finally, many of these techniques provide not just identification but also insight into aging and degradation processes. GC-MS and Py-GC-MS can detect oxidation and polymerization in resins and oils; proteomics reveals the breakdown of collagen due to humidity and biological activity; and FTIR or Raman spectroscopy identifies salt efflorescence, crusts, and pollutant-induced alteration layers [48,69]. These molecular-level insights are crucial for diagnosing deterioration mechanisms and guiding conservation strategies grounded in material behavior.

3.3. Integrated and Multimodal Analysis

Given the multilayered and heterogeneous nature of polychrome sculptures—often composed of inorganic pigments, organic binders, metallic gilding, and composite substrates—no single analytical method can offer a complete picture of their material composition or deterioration processes. As a result, recent advances in heritage science emphasize integrated, multimodal approaches that combine chemical, physical, molecular, and spatial techniques. These integrated strategies allow researchers to not only identify materials more comprehensively but also understand how different layers interact, degrade, or respond to conservation interventions [1].

The strength of multimodal analysis lies in methodological complementarity. Each technique provides a distinct type of information with its own strengths and limitations, as summarized in Table 1. For example, XRF provides rapid elemental identification for heavy metals such as Pb, Hg, and Cu, but cannot detect organic components. Raman spectroscopy, with its high spatial resolution, adds molecular specificity, enabling distinction between similar mineral pigments like cinnabar and red lead. FTIR bridges the gap by detecting organic functional groups in binders and coatings, though its surface sensitivity is limited. GC-MS and Py-GC-MS are essential for identifying lipids, waxes, and natural resins at the molecular level [67], while proteomics offers species-level resolution of proteinaceous materials, such as animal glues and egg binders [25]. Techniques like LIBS and MSI/HSI expand the toolkit by providing depth profiling and pigment mapping capabilities, albeit with certain constraints such as surface ablation or lower resolution. Therefore, when used in combination—such as FTIR with GC-MS, or nano-FTIR with proteomics—these techniques can jointly reconstruct complex media systems in stratified polychrome layers [3].

Table 1.

Overview of major analytical techniques used in polychrome sculpture analysis, summarizing each method’s primary detection targets, spatial resolution, invasiveness, and key limitations.

In addition to cross-method complementarity, multimodal integration also spans analytical scales. On the micro-scale, cross-sectional microscopy, SEM–EDS, and micro-Raman imaging enable visualization of pigment particles, layering sequences, and localized defects. On the meso-scale, methods such as MA-XRF, hyperspectral imaging (HSI), and fluorescence lifetime imaging allow for mapping material distribution and surface treatments across entire sculpture faces or bodies. On the macro-scale, 3D scanning, CT imaging, and structural modeling reveal internal voids, hidden joints, and previous repairs—essential for understanding load-bearing integrity and hidden construction strategies. When these datasets are co-registered, they create a spatially layered “information map” that links internal structure with material identity and degradation features [26].

Beyond diagnostics, multimodal analysis has also facilitated the creation of knowledge infrastructures. Spectral libraries (e.g., Raman, FTIR), chromatographic databases (e.g., GC-MS profiles of oils and resins), and peptide repositories (e.g., proteomic signatures of glues and gums) are increasingly used to support automated material identification and comparative studies. Meanwhile, statistical tools such as principal component analysis (PCA), hierarchical clustering, and machine learning are now applied to large-scale datasets from MSI and MA-XRF, helping to segment original, overpainted, and deteriorated zones with minimal subjectivity [6]. These computational strategies accelerate interpretation, reduce human error, and improve reproducibility in heritage science.

Ultimately, multimodal integration marks a paradigm shift—from isolated, technique-specific analysis to holistic, systemic diagnostics. It supports three core research objectives: (1) reconstructing full crafting sequences from substrate preparation to final coatings; (2) tracing material origins for provenance and cross-cultural comparisons; and (3) diagnosing deterioration mechanisms by correlating material changes with structural and environmental stressors. Looking ahead, the fusion of spectral big data, AI-assisted interpretation, and 3D visualization technologies is poised to establish a new generation of intelligent, interoperable workflows in the conservation of polychrome sculptures.

4. Case Studies

This section presents three representative case studies conducted between 2021 and 2024, highlighting polychrome artifacts from Brazil, China, and Central Africa. These cases illustrate how scientific techniques can be adapted to different cultural materials, including wooden religious sculptures, stratified mural paintings, and ritual objects with complex organic coatings. Non-invasive and minimally invasive methods—such as XRF, digital radiography (DR), CT, LIBS, FTIR, GC-MS, and proteomics—were employed to analyze pigment composition, structural integrity, and organic residues. Together, these studies demonstrate how cross-scale, multi-modal approaches enable a deeper understanding of fabrication methods, restoration history, and cultural significance, offering a robust framework for both documentation and conservation in heritage science.

4.1. Saint Eligius Polychrome Sculpture, Brazil

The polychrome sculpture of Saint Eligius, housed in the Church of Santa Luzia in Rio de Janeiro, is believed to be an 18th-century piece of Portuguese origin, based on stylistic and formal analysis. This case exemplifies the integration of non-invasive diagnostic techniques in the study of religious sculpture, combining X-ray fluorescence (XRF), digital radiography (DR), and computed tomography (CT) to investigate both material composition and structural integrity [75,76].

XRF analysis revealed the presence of several key elements, notably lead (Pb), iron (Fe), barium (Ba), and zinc (Zn), which are consistent with the use of lead white, iron-based earth pigments, and modern white pigments. Although mercury (Hg) was detected at selected measurement points, its occurrence was limited and context-dependent, and does not allow a systematic attribution of cinnabar (HgS) across the examined areas [75]. Lead signals confirmed the presence of lead white (PbCO3·Pb(OH)2), commonly used as a ground or mixing pigment, while iron was associated with ochre-based pigments. The detection of barium and zinc indicates the presence of lithopone (BaSO4 + ZnS), a pigment introduced in the late 19th century, together with synthetic blue pigments such as phthalocyanine blue, providing clear evidence of modern restoration interventions [12].

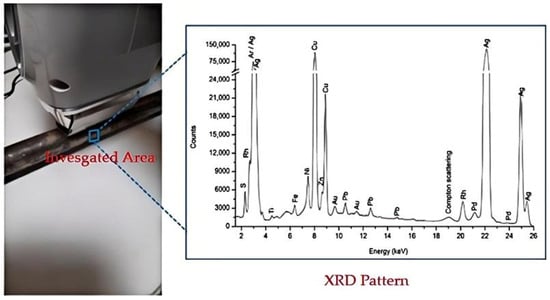

Elemental distributions related to original and restored areas are visualized in Figure 8, which illustrates Pb- and Fe-rich zones rather than providing direct mineralogical evidence for cinnabar. Accordingly, Figure 8 should be interpreted as documenting elemental contrast between historical paint layers and modern retouchings, not as definitive proof of HgS-based red pigments [75].

Figure 8.

Crosier (detail) with analyzed points marked, and the corresponding spectra indicating the presence of cinnabar [75].

Structural investigation using DR and CT revealed critical internal features such as wear-related damage, old joints, hidden fractures, and reinforcement elements. CT imaging provided three-dimensional visualization of insect-related cavities, metallic nails securing the sculpture to its base, and internal construction features including joinery and decorative fixings [76]. These findings contributed to the assessment of the sculpture’s mechanical stability, which is essential for conservation planning.

The combined application of elemental analysis (XRF) and imaging-based diagnostics (DR and CT) demonstrates a state-of-the-art, non-invasive analytical framework for polychrome sculpture research. This integrated approach enables the differentiation between original materials and later interventions while supporting historically informed conservation strategies. As such, the Saint Eligius case exemplifies a cross-scale, contact-free methodology that is increasingly foundational in European and transatlantic sculpture studies [12,77,78].

4.2. Terracotta Warriors, China

The Terracotta Warriors of Qin Shihuang’s mausoleum represent one of the most iconic examples of ancient polychrome sculpture. Although most pigments have deteriorated, traces of polychromy remain on armor plates, robes, and facial features. Identifying the binding media used in these sculptures is crucial for understanding original painting practices and for guiding conservation treatments. Early instrumental studies based on GC–MS and amino acid analysis suggested the possible use of egg-based binders, while also highlighting the difficulty of distinguishing proteinaceous materials in severely aged samples [79,80,81].

In a more recent study, researchers applied immunofluorescence microscopy (IFM) to detect and localize specific proteinaceous binders at the microscopic level [79]. The study employed anti-ovalbumin antibodies to determine whether egg white—a common ancient binder—was used in the painted layers. When applied to sample cross-sections, these antibodies produced bright red-orange fluorescence, indicating a positive immuno-reaction and confirming the presence of egg white protein. This interpretation was further strengthened by negative immunodetection results for collagen, effectively excluding animal glue as the primary binder [82,83].

By combining IFM with earlier GC–MS investigations of Qin and Han dynasty polychrome terracotta, the study demonstrated how molecular-level and immunological approaches can be integrated to clarify historical material practices even in heavily degraded contexts [82,83]. Beyond historical interpretation, this analytical strategy provides a scientific basis for the development of bio-compatible conservation materials that respect the chemistry of the original paint system. Immunofluorescence imaging highlights the egg white layer in red-orange under fluorescence microscopy, offering direct visual confirmation of its presence and spatial distribution within the polychrome stratigraphy.

4.3. Traditional African Wooden Sculptures

yATR-FTIR spectra revealed the presence of typical markers for aged natural organics, including carbonyl groups (~1700 cm−1) from oxidized resins, long-chain methylene bands (720–730 cm−1) from waxes or fats, and aromatic C=C ring vibrations (~1600 cm−1) indicative of soot or charred organic residues. These spectral features helped differentiate original ritual coatings from more recent conservation materials. GC-MS further detected diterpenoid resin components (e.g., abietic-acid derivatives) together with saturated fatty acids such as palmitic and stearic acids, which are consistent with waxy or oily substances. In addition, synthetic compounds such as poly (vinyl acetate) (PVAc) degradation products were identified, indicating the presence of modern conservation adhesives applied during post-collection interventions [73,84].

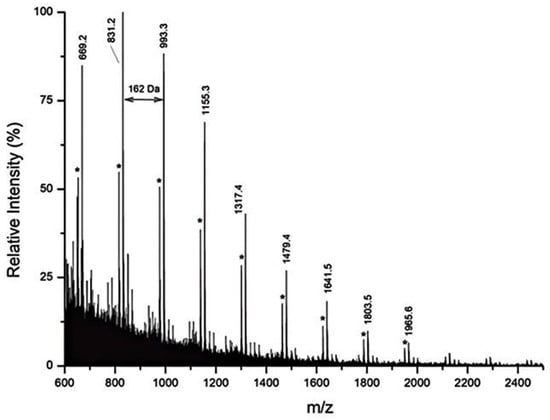

MALDI-MS analysis, rather than directly identifying a specific plant species, provided molecular-level evidence for the presence and compositional nature of polysaccharide materials. The mass spectrum shown in Figure 9 displays ion series in the m/z 600–2500 Da range with dominant 162 Da mass intervals, characteristic of hexose-based polysaccharides, together with less intense 132 Da intervals attributable to pentose units [85]. The predominance of hexose repeats indicates materials such as starch or starch-rich mixtures, while the subordinate pentose signals suggest the possible presence of plant gums. Importantly, Figure 9 does not provide a definitive botanical identification, but instead constrains the polysaccharide class based on repeating monosaccharide mass patterns [86].

Figure 9.

Mass spectrum (m/z range 600–2500 Da) from MALDI-MS analysis of sample S4 from the female figure, enzymatically digested with exo-β-1,3-galactanase [73]. The asterisk (*) indicates the corresponding sodium cation adducts.

Proteomic analysis represented the decisive step for biological identification, enabling the detection of blood-derived proteins at the species level. LC-MS/MS results confirmed the presence of serum albumin, hemoglobin, and fibrinogen, allowing attribution to specific animal sources including chicken (Gallus gallus), goat (Capra hircus), sheep (Ovis aries), and dog (Canis lupus familiaris). This level of identification cannot be achieved by FTIR or MALDI-MS alone and is critical for distinguishing intentional ritual applications from incidental contamination [87]. Figure 9 should be understood as documenting the molecular fingerprint of polysaccharide materials through MALDI-MS, rather than as a conclusive identification of a specific plant gum or starch source. When integrated with FTIR, Py-GC-MS, and proteomics, these data allow reconstruction of the complex, multi-component ritual surfaces characteristic of traditional African wooden sculptures, while clearly separating original use-related materials from later conservation interventions [87,88].

5. Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant advancements in analytical capabilities, the study of polychrome sculpture materials continues to face several persistent challenges—both technical and methodological. One of the most pressing issues remains the identification of organic binders, such as animal glues, plant gums, oils, and resins. These components are highly susceptible to degradation, often present in trace amounts, and exhibit significant chemical variability. While molecular-level techniques like GC-MS and proteomics offer enhanced detection capabilities, their effectiveness is limited by the current lack of comprehensive spectral libraries and standardized interpretation protocols. Moreover, the reliability of these results is further complicated by contamination risks and overlapping restoration materials. Thus, there is an urgent need not only for better instrumentation but also for stronger interpretive frameworks that critically assess the quality and reproducibility of molecular data.

A second major challenge lies in the integration of multimodal data. Although the combination of spectroscopic, microscopic, and imaging techniques is frequently advocated, in practice, the interoperability of such datasets remains limited. Co-registration between scales—from nanostructural features to CT-based internal imaging—is rarely achieved in a consistent or repeatable manner. This fragmentation of data pipelines weakens the interpretive power of cross-method comparisons and restricts the construction of comprehensive material biographies. While AI and machine learning show potential in automating segmentation and classification of pigments or binders, their adoption has been slow due to the scarcity of validated training datasets and the risk of algorithmic overfitting in culturally sensitive contexts.

Critically, many of the current studies tend to overemphasize instrumental performance while underrepresenting limitations such as detection thresholds, interpretive ambiguity, or methodological inconsistency. This imbalance reduces the reproducibility and comparability of findings across different research groups. To move beyond this, the field must adopt a more critical and reflexive stance—acknowledging not only what has been achieved, but also where data gaps, contested interpretations, and unresolved technical debates persist.

Future research must prioritize the development of standardized analytical workflows, shared spectral databases, and accessible open-science tools that support reproducibility across regions and institutions. The creation of interoperable digital platforms will be essential in linking multimodal datasets, while AI-assisted analysis should be implemented cautiously, with transparency in data provenance and validation protocols. Ultimately, the goal is not only to increase technical accuracy but also to ensure that material studies meaningfully support sustainable, culturally-informed conservation decisions.

6. Conclusions

Over the past two decades, the field of material identification in polychrome sculpture studies has evolved into a highly interdisciplinary and technically dynamic domain. It brings together conservation science, analytical chemistry, art history, and increasingly, digital technologies. This expansion has significantly improved our ability to investigate the layered structures, pigment-binder interactions, and historical interventions embedded within polychrome sculptures. Techniques such as XRF, Raman, FTIR, LIBS, GC-MS, and proteomics now form the backbone of analytical toolkits, while case studies from Brazil, China, and Central Africa highlight the contextual flexibility and diagnostic depth that multimodal approaches can achieve.

However, despite these successes, the field remains at a crossroads. Persistent difficulties in identifying degraded organics, inconsistencies in non-invasive workflows, and the limited integration of structural and chemical imaging data constrain both research potential and conservation practice. Moreover, interpretive overconfidence in instrumental data—particularly in studies lacking cross-validation—risks masking underlying uncertainties or cultural biases. Addressing these limitations requires more than new tools; it demands a shift toward critical evaluation, collaborative standard-setting, and ethical reflection on heritage science methodologies.

Looking forward, the integration of AI-assisted analysis, open-access data platforms, and minimally invasive diagnostics will likely define the next frontier. Yet these innovations must be guided by clear epistemological frameworks and cross-disciplinary dialogue. Polychrome sculpture studies are not merely exercises in material deconstruction—they are gateways to reconstructing historical knowledge systems, artistic intention, and cultural meaning. By embracing both technological precision and interpretive humility, future research can deepen our understanding of these layered cultural objects while supporting their preservation for generations to come.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Z. and L.X.; methodology, W.Z.; software, W.Z.; validation, W.Z., X.L. and L.X.; formal analysis, W.Z.; investigation, W.Z.; resources, X.L.; data curation, W.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, W.Z.; writing—review and editing, L.X.; visualization, W.Z.; supervision, L.X.; project administration, L.X.; funding acquisition, X.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lluveras-Tenorio, A.; Andreotti, A.; Talarico, F.; Legnaioli, S.; Olivieri, L.M.; Colombini, M.P.; Bonaduce, I.; Pannuzi, S. An Insight into Gandharan Art: Materials and Techniques of Polychrome Decoration. Heritage 2022, 5, 488–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinna, D.; Conti, C.; Mazurek, J. Polychrome Sculptures of Medieval Italian Monuments: Study of the Binding Media and Pigments. Microchem. J. 2020, 158, 105100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franquelo, M.L.; Duran, A.; Castaing, J.; Arquillo, D.; Perez-Rodriguez, J.L. XRF, μ-XRD and μ-Spectroscopic Techniques for Revealing the Composition and Structure of Paint Layers on Polychrome Sculptures after Multiple Restorations. Talanta 2012, 89, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, E.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, F.; Wang, C. Pigments and Binding Media of Polychrome Relics from the Central Hall of Longju Temple in Sichuan, China. Herit. Sci. 2019, 7, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccato, A.; Moens, L.; Vandenabeele, P. On the Stability of Mediaeval Inorganic Pigments: A Literature Review of the Effect of Climate, Material Selection, Biological Activity, Analysis and Conservation Treatments. Herit. Sci. 2017, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harth, A. The Study of Pigments in Cultural Heritage: A Review Using Machine Learning. Heritage 2024, 7, 3664–3695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; An, J.; Zhou, T.; Li, Y. Analysis of Proteinaceous Binding Media Used in Tang Dynasty Polychrome Pottery by MALDI-TOF-MS. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2013, 58, 2932–2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberis, E.; Baiocco, S.; Conte, E.; Gosetti, F.; Rava, A.; Zilberstein, G.; Righetti, P.G.; Marengo, E.; Manfredi, M. Towards the Non-Invasive Proteomic Analysis of Cultural Heritage Objects. Microchem. J. 2018, 139, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lluveras-Tenorio, A.; Vinciguerra, R.; Galano, E.; Blaensdorf, C.; Emmerling, E.; Colombini, M.P.; Birolo, L.; Bonaduce, I. GC/MS and Proteomics to Unravel the Painting History of the Lost Giant Buddhas of Bāmiyān (Afghanistan). PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172990. [Google Scholar]

- Ljaljević Grbić, M.; Dimkić, I.; Janakiev, T.; Kosel, J.; Tavzes, Č.; Popović, S.; Knežević, A.; Legan, L.; Retko, K.; Ropret, P.; et al. Uncovering the Role of Autochthonous Deteriogenic Biofilm Community: Rožanec Mithraeum Monument (Slovenia). Microb. Ecol. 2024, 87, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Kang, Y.; Li, Q. Analytical Study of Polychrome Clay Sculptures in the Five-Dragon Taoist Palace of Wudang, China. Coatings 2024, 14, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calza, C.; Oliveira, D.F.; Freitas, R.P.; Rocha, H.S.; Nascimento, J.R.; Lopes, R.T. Analysis of Sculptures Using XRF and X-ray Radiography. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2015, 116, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, H. Saint John at Calvary: Technical and Material Study of a Polychrome Wood Sculpture. CeROArt 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platania, E.; Streeton, N.L.W.; Lluveras-Tenorio, A.; Vila, A.; Buti, D.; Caruso, F.; Kutzke, H.; Karlsson, A.; Colombini, M.P.; Uggerud, E. Identification of Green Pigments and Binders in Late Medieval Painted Wings from Norwegian Churches. Microchem. J. 2020, 156, 104811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, M. Three Polychrome Japanese Buddhist Sculptures from the Kamakura Period: The Scientific Examination of Layer Structures, Ground Materials, Pigments, Metal Leafs, and Powders. In Scientific Research on the Pictorial Arts of Asia—Proceedings of the Second Forbes Symposium at the Freer Gallery of Art; Archetype Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2005; pp. 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Tamburini, D.; Kotonski, V.; Lluveras-Tenorio, A.; Colombini, M.P.; Green, A. The Evolution of the Materials Used in the Yun Technique for the Decoration of Burmese Objects: Lacquer, Binding Media and Pigments. Herit. Sci. 2019, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.H.; Lee, H.H.; Song, Y.N.; Min, K.J.; Chung, Y.J. An Analytical Investigation on the Dancheong Pigments by Hyperspectral Technique: Focusing on Green Colors. J. Conserv. Sci. 2019, 35, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Han, K.; Teri, G.; Cheng, C.; Qi, Y.; Li, Y. Material and Microstructure Analysis of Wood Color Paintings from Shaanxi Cangjie Temple, China. Molecules 2024, 29, 2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggelakopoulou, E.; Bakolas, A. Investigating Polychromy on the Parthenon’s West Metopes. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2024, 16, 96. [Google Scholar]

- Basso, E.; Carò, F.; Abramitis, D.H. Polychromy in Ancient Greek Sculpture: New Scientific Research on an Attic Funerary Stele at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getty Conservation Institute (GCI). Conservation Institute—About and Scientific Research. Getty 2025. Available online: https://www.getty.edu/conservation-institute/ (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- Tomasini, E.P.; Gómez, B.; Halac, E.B.; Reinoso, M.; Di Liscia, E.J.; Siracusano, G.; Maier, M.S. Identification of Carbon-Based Black Pigments in Four South American Polychrome Wooden Sculptures by Raman Microscopy. Herit. Sci. 2015, 3, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franquelo, M.L.; Duran, A.; Arquillo, D.; Perez-Rodriguez, J.L. Old and Modern Pigments Identification from a 14th Century Sculpture by Micro-Raman. Spectrosc. Lett. 2011, 44, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosano, D.; Esquivel, D.; Costa, C.M.; Jimenez-Sanchidrian, C.; Ruiz, J.R. Identification of Pigments in the Annunciation Sculptural Group (Cordoba, Spain) by Micro-Raman Spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta A 2019, 214, 139–145. [Google Scholar]

- Kuckova, S.; Sandu, I.C.A.; Crhova, M.; Hynek, R.; Fogas, I.; Schafer, S. Protein Identification and Localization Using Mass Spectrometry and Staining Tests in Cross-Sections of Polychrome Samples. J. Cult. Herit. 2013, 14, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Li, L.; Zhang, D.; Dong, S.; Xiang, J.; Xu, N. A Multi-Analytical Approach to Investigate the Polychrome Clay Sculpture in Qinglian Temple of Jincheng, China. Materials 2022, 15, 5470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guglielmi, V.; Lombardi, C.A.; Fiocco, G.; Comite, V.; Bergomi, A.; Borelli, M.; Azzarone, M.; Malagodi, M.; Colella, M.; Fermo, P. Multi-Analytical Investigation on a Renaissance Polychrome Earthenware Attributed to Giovanni Antonio Amadeo. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Monaco, A.; Agresti, G.; Serusi, G.; Taddei, A.R.; Pelosi, C. History and Techniques of a Polychrome Wooden Statue: How an Integrated Approach Contributes to Resolving Iconographic Inconsistencies. Heritage 2022, 5, 2488–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Han, K.; Teri, G.; Tian, Y.; Cui, M.; Qi, Y.; Li, Y. A Study on the Materials Used in Ancient Wooden Architectural Paintings at DaZhong Gate in Confucius Temple, Qufu, Shandong, China. Materials 2024, 17, 2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.; Murta, E.; Candeias, A.; Cardoso, A.; Dias, L.; Ferreira, T.; Mirao, J.; Dias, C. Estofado Materials and Techniques: Contribution for the Characterisation of Regional Production of Baroque Polychrome Sculptures. In Proceedings of the Polychrome Sculpture: Decorative Practice and Artistic Tradition (ICOM-CC Interim Meeting, Working Group Sculpture, Polychromy, and Architectural Decoration), Tomar, Portugal, 28–29 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, T.G.; Kremer, K.; Richter, F.A.; de Campos Júnior, F.A.; Furini, L.N. Material Analysis of 18th Century Polychrome Sacred Sculpture of Our Lady: Iconographic Impact and the Conservation and Restoration Process. Colorants 2025, 4, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sá, S.; Hendriks, L.; Cardoso, I.P.; Hajdas, I. Radiocarbon Dating of Lead White: Novel Application in the Study of Polychrome Sculpture. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leona, M. Microanalysis of Organic Pigments and Glazes in Polychrome Works of Art by Surface-Enhanced Resonance Raman Scattering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 14757–14762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, L.; Head, K.; Thomas, P.; Stuart, B. FTIR and Raman Microscopy of Organic Binders and Extraneous Organic Materials on Painted Ceremonial Objects from the Highlands of Papua New Guinea. Microchem. J. 2017, 134, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bellaigue, D.; Chloros, J.; Troalen, L.; Hendriks, L.; Lenglet, J.; Castel, J.; Dectot, X.; Haghipour, N. Two Sculptures, One Master? A Technical Study of Two Rare Examples of Polychrome Sculptures Associated with “the Master of Saint Catherine of Gualino”, Italy, Fourteenth Century. J. Am. Inst. Conserv. 2024, 63, 28–51. [Google Scholar]

- Han, K.; Teri, G.; Cheng, C.; Tian, Y.; Huang, D.; Ge, M.; Fu, P.; Luo, Y.; Li, Y. Evaluation of Commonly Used Reinforcement Materials for Color Paintings on Ancient Wooden Architecture in China. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigante, E.C.; Calvano, C.D.; Ventura, G.; Cataldi, T.R. Look but Don’t Touch: Non-Invasive Chemical Analysis of Organic Paint Binders—A Review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2025, 1335, 343251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šefců, R.; Pitthard, V.; Dáňová, H.; Třeštíková, A. An Analytical Investigation of a Unique Medieval Wood Sculpture and Its Monochrome Surface Layer. Wood Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 541–554. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.; Xia, H.; Wang, R.; Fan, W.; Shi, M.; Liu, Q.; Xie, Y. Study on the Painted Clay Sculptures of Ming Dynasty in Jingyin Temple of Taiyuan, China. Research Square 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, M.J.; Saiz Mauleón, M.B.; Curiel-Esparza, J.; Llinares, J.; Soriano, M. Polychromy of Late Gothic Civil Architecture: A World Heritage Monument Case in Spain. Mediterr. Archaeol. Archaeom. 2013, 13, 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Sandu, I.C.A.; De Sá, M.H.; Pereira, M.C. Ancient ‘Gilded’ Art Objects from European Cultural Heritage: A Review on Different Scales of Characterization. Surf. Interface Anal. 2011, 43, 1134–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Lu, T.; Shen, L. Investigation of Gold Gilding Materials and Techniques Applied in the Murals of Kizil Grottoes, Xinjiang, China. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocchieri, J.; Scialla, E.; Manzone, A.; Graziano, G.O.; D’Onofrio, A.; Sabbarese, C. An Analytical Characterization of Different Gilding Techniques on Artworks from the Royal Palace (Caserta, Italy). J. Cult. Herit. 2022, 57, 213–225. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, C.; Bracci, S.; Conti, C.; Greco, M.; Realini, M. Non-Invasive Approach in the Study of Polychrome Terracotta Sculptures: Employment of X-Ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy to Investigate Complex Stratigraphy. X-Ray Spectrom. 2011, 40, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, J.L.; Roldán, C.; Juanes, D.; Rollano, E.; Morera, C. Analysis of Pigments from Spanish Works of Art Using a Portable EDXRF Spectrometer. X-Ray Spectrom. 2002, 31, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez-Rodríguez, O.; Argote-Espino, D.; Santos-Ramírez, M.; López-García, P. Portable XRF analysis for the identification of raw materials of the Red Jaguar sculpture in Chichen Itza, Mexico. Quatern. Int. 2018, 483, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colomban, P.; Gerken, M.; Gironda, M.; Mesqui, V. On-Site Micro-XRF Mapping of Enameled Porcelain Paintings: An Archaeometric Demonstration. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2025, 45, 116849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marszałek, M. Identification of secondary salts and their sources in deteriorated stone monuments using micro-Raman spectroscopy, SEM-EDS and XRD. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2016, 47, 1473–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marano, D.; Catalano, I.M.; Monno, A. Pigment identification on “Pietà” of Barletta, example of Renaissance Apulian sculpture: A Raman microscopy study. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2006, 64, 1147–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bersani, D.; Lottici, P.P. Raman Spectroscopy of Minerals and Mineral Pigments in Archaeometry. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2016, 47, 499–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordignon, F.; Postorino, P.; Dore, P.; Tabasso, M.L. The Formation of Metal Oxalates in the Painted Layers of a Medieval Polychrome on Stone, as Revealed by Micro-Raman Spectroscopy. Stud. Conserv. 2008, 53, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Analytical Methods Committee AMCTB No 80. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) in cultural heritage. Anal. Methods 2017, 9, 4338–4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, A.; Pérez-Alonso, M.; Olivares, M.; Castro, K.; Martínez-Arkarazo, I.; Fernández, L.A.; Madariaga, J.M. Classification and identification of organic binding media in artworks by means of Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and principal component analysis. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011, 399, 3601–3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaduce, I.; Colombini, M.P. Characterisation of Beeswax in Works of Art by Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry and Gas Chromatography–Combustion–Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2004, 1028, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Defeyt, C.; Langenbacher, J.; Rivenc, R. Polyurethane Coatings Used in Twentieth Century Outdoor Painted Sculptures. Part I: Comparative Study of Various Systems by Means of ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy. Herit. Sci. 2017, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catelli, E.; Sciutto, G.; Prati, S.; Jia, Y.; Mazzeo, R. Characterization of Outdoor Bronze Monument Patinas: The Potentialities of Near-Infrared Spectroscopic Analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 24379–24393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz-Granados, K.; Price, R.; McBride, J.R.; Moffett, D.; Kavich, G. Identification of Surface Coatings on Central African Wooden Sculptures Using Nano-FTIR Spectroscopy. ACS Photonics 2024, 11, 3131–3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comelli, D.; Valentini, G.; Cubeddu, R.; Toniolo, L. Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging and Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy for the Analysis of Michelangelo’s David. Appl. Spectrosc. 2005, 59, 1174–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceto, M.; Agostino, A.; Fenoglio, G.; Idone, A.; Gulmini, M.; Picollo, M.; Ricciardi, P.; Delaney, J.K. Characterisation of Colourants on Illuminated Manuscripts by Portable Fibre Optic UV-Visible-NIR Reflectance Spectrophotometry. Anal. Methods 2014, 6, 1488–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosentino, A. FORS Spectral Database of Historical Pigments in Different Binders. e-Conserv. J. 2014, 2, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genc Oztoprak, B.; Sinmaz, M.A.; Tülek, F. Composition Analysis of Medieval Ceramics by Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS). Appl. Phys. A 2016, 122, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giakoumaki, A.; Melessanaki, K.; Anglos, D. Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) in Archaeological Research. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2007, 387, 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haladová, Z.B.; Szemzö, R.; Kovačovský, T.; Žižka, J. Utilizing multispectral scanning and augmented reality for enhancement and visualization of the wooden sculpture restoration process. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 67, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucci, C.; Delaney, J.K.; Picollo, M. Reflectance Hyperspectral Imaging for Investigation of Works of Art: Old Master Paintings and Illuminated Manuscripts. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 2070–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remondino, F.; Campana, S. 3D Recording and Modelling in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage; British Archaeological Reports: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, K.; Akada, M.; Torigoe, T.; Imazu, S.; Sugiyama, J. Automated recognition of wood used in traditional Japanese sculptures by texture analysis of their low-resolution computed tomography data. J. Wood Sci. 2015, 61, 630–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casoli, A.; Cremonesi, P.; Palla, G.; Vizzari, M. Application of Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry to the Study of Works of Art: Paint Media Identification in Polychrome Multi-Material Sculptures. Ann. Chim. 2001, 91, 727–739. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zhen, G.; Hao, X.; Zhou, P.; Wang, Z.; Jia, J.; Tong, H. Micro-Raman, XRD and THM-Py-GC/MS analysis to characterize the materials used in the Eleven-Faced Guanyin of the Du Le Temple of the Liao Dynasty, China. Microchem. J. 2021, 171, 106828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, K.; Schwarzinger, C.; Price, B.A. The application of pyrolysis gas chromatography mass spectrometry for the identification of degraded early plastics in a sculpture by Naum Gabo. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2012, 94, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, J.; Tamburini, D.; Sotiropoulou, S. The identification of lac as a pigment in ancient Greek polychromy—The case of a Hellenistic oinochoe from Canosa di Puglia. Dye. Pigment. 2018, 149, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckova, S.; Baumer, U.; Dietemann, P. Proteomic distinguishing between egg white, yolk and whole egg tempera binders in cross-sections and samples of Italian medieval and renaissance paintings. Microchem. J. 2025, 216, 114697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, H.Y.; Yang, Y.M.; Abuduresule, I.; Li, W.Y.; Hu, X.J.; Wang, C.S. Proteomic identification of adhesive on a bone sculpture-inlaid wooden artifact from the Xiaohe Cemetery, Xinjiang, China. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2015, 53, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granzotto, C.; Sutherland, K.; Goo, Y.A.; Aksamija, A. Characterization of surface materials on African sculptures: New insights from a multi-analytical study including proteomics. Analyst 2021, 146, 3305–3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müskens, S.; Braekmans, D.; Versluys, M.J.; Degryse, P. Egyptian sculptures from Imperial Rome. Non-destructive characterization of granitoid statues through macroscopic methodologies and in situ XRF analysis. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2018, 10, 1303–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzi, I.V.N.S.; de Paula, A.G.; Cavalcante, J.E.; Borges, R.M.; Gomes, R.; Gonçalves, F.; Coutinho, M.; Oliveira, D.F.; Lopes, R.T. Non-Invasive Analysis of the Sculpture of Saint Eligius: Application of X-Ray Fluorescence, Digital Radiography, and Computed Tomography. X-Ray Spectrom. 2025, 55, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R.; de Paula, A.; Gonçalves, F.; Bueno, R.; Calgam, T.; Azeredo, S.; Araújo, O.; Machado, A.; Anjos, M.; Lopes, R.; et al. Development and characterization of a portable CT system for wooden sculptures analysis. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2022, 200, 110409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Chen, Y.; Peng, L.; Yang, X.; Bai, Y. Application of spectroscopy technique in cultural heritage: Systematic review and bibliometric analysis. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitossi, G.; Giorgi, R.; Mauro, M.; Salvadori, B.; Dei, L. Spectroscopic Techniques in Cultural Heritage Conservation: A Survey. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2005, 40, 187–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, B.; Rong, B. Analysis of Polychromy Binder on Qin Shihuang’s Terracotta Warriors by Immunofluorescence Microscopy. J. Cult. Herit. 2015, 16, 244–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Ma, Q.; Schreiner, M. Scientific Investigation of the Paint and Adhesive Materials Used in the Western Han Dynasty Polychromy Terracotta Army, Qingzhou, China. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2012, 39, 1628–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaduce, I.; Blaensdorf, C.; Dietemann, P.; Colombini, M.P. The binding media of the polychromy of Qin Shihuang’s Terracotta Army. J. Cult. Herit. 2008, 9, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagnini, M.; Pitzurra, L.; Cartechini, L.; Miliani, C.; Brunetti, B.G.; Sgamellotti, A. Identification of proteins in painting cross-sections by immunofluorescence microscopy. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2008, 392, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandu, I.C.A.; Schäfer, S.; Magrini, D.; Bracci, S.; Roque, C.A. Cross-section and staining-based techniques for investigating organic materials in painted and polychrome works of art: A review. Microsc. Microanal. 2012, 18, 860–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlstein, E. Fatty bloom on wood sculpture from Mali. Stud. Conserv. 1986, 31, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granzotto, C.; Arslanoglu, J.; Rolando, C.; Tokarski, C. Plant gum identification in historic artworks. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granzotto, C.; Sutherland, K.; Arslanoglu, J.; Ferguson, G.A. Discrimination of Acacia gums by MALDI-TOF MS: Applications to micro-samples from works of art. Microchem. J. 2019, 144, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazel, V.; Richardin, P.; Debois, D.; Touboul, D.; Cotte, M.; Brunelle, A.; Laprévote, O. Identification of ritual blood in African artifacts using TOF-SIMS and synchrotron radiation microspectroscopies. Anal. Chem. 2007, 79, 9253–9260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaduce, I.; Ribechini, E.; Modugno, F.; Colombini, M.P. Analytical Approaches Based on Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS) to Study Organic Materials in Artworks and Archaeological Objects. In Analytical Chemistry for Cultural Heritage; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 291–327. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.