Abstract

Chromium nitride (Cr-N) coatings fabricated by physical vapor deposition (PVD) have gained significant interest in the field of surface protection with the exceptional hardness, robust adhesion to substrates, and superior wear resistance. The mechanical properties of Cr-N coatings are predominantly determined by their chemical composition, phase structure, and microstructure. The selection of deposition technique and regulation of process parameters, such as N2 flow rate, play a crucial role in optimizing coating performance. This review systematically summarizes recent research advancements in PVD-fabricated Cr-N coatings with a specific focus on both monolayer and multilayer architectures. It explores the impact of process parameters on the hardness, adhesion strength, and tribological properties. Furthermore, it outlines the design strategies and fabrication methodologies for high-performance Cr-N coatings. Results indicate that the mechanical properties of monolayer Cr-N coating are primarily governed by the process parameters. As for multilayer coatings, the incorporation of ductile Cr layers can enhance the coating-substrate adhesion strength and wear resistance while preserving a relatively high hardness. This study aims to provide a theoretical foundation and technical reference for future research and applications of the Cr-N coating material system.

1. Introduction

Depositing high-performance protective coatings on the surfaces of specialized mechanical components and cutting tools and optimizing their mechanical properties through advanced fabrication processes have emerged as pivotal strategies for enhancing the service life and reliability of workpieces under challenging operating conditions, such as high temperature, high load, and severe wear [1,2,3,4]. Among the various protective coatings, nitride-based coatings are regarded as one of the most promising surface protection technologies because of their strong adhesion to substrates, excellent wear resistance, and outstanding corrosion resistance [5,6]. Transition metal nitrides, characterized by high melting points, high hardness, good chemical stability, and superior tribological properties, have been extensively studied and applied in the domains of hard, wear-resistant, and corrosion-resistant coatings [7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Chromium (Cr), a significant transition metal, exhibits excellent mechanical properties. Historically, electroplated chromium coatings have played a crucial role in the aerospace, defense, and mechanical manufacturing industries [14,15,16]. However, traditional electroplating processes generate toxic wastewater and exhaust gases containing Cr6+, posing serious threats to the environment and human health. Furthermore, electroplated Cr coatings typically exhibit poor adhesion to substrates and are prone to spalling under stress, thereby limiting their application in high-end equipment. Consequently, there is an urgent need to develop environmentally friendly, high-performance alternative technologies.

Physical Vapor Deposition (PVD) technology, characterized by its low deposition temperature, high process controllability, and environmental sustainability, is considered as a promising alternative to electroplating and has emerged as a pivotal technological platform for preparing high-performance nitride coatings. Among various PVD techniques, High-Power Impulse Magnetron Sputtering (HiPIMS) is an innovative technology that offers exceptionally high peak power and plasma densities, facilitating the generation of highly ionized particle fluxes (ionization rates of up to 50%–90%), thereby providing unprecedented control over coating growth [17]. Compared to conventional Direct Current Magnetron Sputtering (DCMS) and Cathodic Arc Evaporation (CAE), HiPIMS effectively suppresses the formation of micro-scale droplets commonly associated with CAE, resulting in smoother and denser coating surfaces. Furthermore, by precisely controlling the ion energy and flux, HiPIMS allows the fine-tuning of microstructural features, such as grain size, texture, and stress state, thereby significantly enhancing the coating hardness, adhesion strength, and tribological performance. Studies have demonstrated that preparation by HiPIMS exhibits superior hardness, density, and overall mechanical properties compared to production by DCMS. In particular, Cr-N coatings deposited via surface plating demonstrate excellent corrosion resistance and mechanical performance [18,19,20]. Despite challenges related to the deposition rate and process stability [19], the significant potential of HiPIMS for fabricating high-performance protective coatings is widely acknowledged.

In recent years, to further enhance the performance of coatings under extreme service conditions, researchers have begun investigating hybrid processes that integrate HiPIMS with other PVD technologies, such as DCMS. For instance, Bobzin et al. [21] successfully deposited self-lubricating gradient coatings on 16MnCr5E gear steel at low temperatures (T ≤ 300 °C) using a DCMS/HiPIMS hybrid process at low temperatures. By tailoring the content and distribution of Mo and S, a friction-induced surface layer rich in solid lubricants such as MoS2 and MoO3 was formed, significantly reducing the friction coefficient and wear under dry sliding conditions. This exemplifies the frontier advancements of hybrid PVD technologies in developing “friction-adaptive” or “tribo-active” smart coatings [21]. These coatings not only exhibit high hardness and excellent coating-substrate adhesion but also form lubricious coatings in situ during friction, significantly expanding the application potential of Cr-N coatings in harsh environments, such as oil-free lubrication and high-load gears.

Cr-N coatings (including CrN, Cr2N, and their multicomponent or multilayer structures) prepared by PVD not only eliminate the generation of Cr6+, thereby meeting the requirements of green manufacturing, but also exhibit dense microstructures, controllable architectures, and excellent mechanical properties. In particular, they demonstrate significantly superior hardness, coating-substrate adhesion, and wear resistance compared with traditional electroplated chromium coatings. Consequently, they have garnered extensive attention from researchers across the globe [22,23].

In particular, during the service life of electric vehicles, reducing friction can significantly enhance overall driving range and decrease energy loss, as case-hardened steel fails to meet the requirements for high efficiency and reliability. Bobzin et al. [24] discovered that applying Cr-N coatings to AISI 5115 case-hardened gear steel can form anti-friction chemical reaction layers with low-viscosity lubricants, thereby reducing the coefficient of friction. Furthermore, Cr-N coatings are also utilized in high-speed cutting and the processing of difficult-to-machine materials, addressing critical challenges such as insufficient high-temperature resistance, fatigue resistance, and hardness of the substrate materials [25,26]. Lightweight titanium alloys exhibit good biocompatibility, making them the preferred material for biomedical applications. However, their substrate tribological performance is relatively poor. PVD-deposited high-hardness Cr-N coatings can effectively improve their applicability and service life [27]. However, current studies continue to face challenges and opportunities for optimization to further enhance the comprehensive performance and service life of Cr-N coatings under complex operating conditions through multi-process synergy, precise microstructural design, and control of friction chemical behavior.

This study systematically reviews recent advancements in the research on key mechanical properties, including hardness, adhesion strength, and tribological behavior, of monolayer and multilayer Cr-N coatings fabricated via PVD. In addition, the mechanisms by which process parameters affect the final performance are explored, the strengthening mechanisms and performance optimization strategies are summarized, and an outlook on future development trends in this domain is offered, with the aim of providing insights for material design and engineering applications.

2. Physical Vapor Deposition Technology

PVD is a surface-modification technique in which raw materials are transformed into gaseous atoms, molecules, or ions under high vacuum through processes such as evaporation, sputtering, or ionization, and are subsequently deposited onto a substrate to form a functional coating. Compared to conventional surface treatment methods such as chemical vapor deposition (CVD) and electroplating, PVD offers a denser coating, stronger adhesion between the coating and substrate, a clean and pollution-free process environment, and precise control over the coating architecture and properties. Consequently, it has garnered significant attention in modern high-end equipment and precision manufacturing industries. The three primary PVD techniques are vacuum evaporation, sputter deposition, and ion plating. Vacuum evaporation, the earliest PVD method, provides high deposition rates and coating purity; however, the coatings typically exhibit poor adhesion and limited throwing power. Sputter deposition involves bombarding a target with energetic particles that eject target atoms that condense on the substrate. This method accommodates a wide range of target materials and produces uniform, well-adherent coatings. However, conventional sputtering is characterized by relatively low deposition rates and low ionization efficiency. To address these limitations, ion plating was developed. By combining the advantages of evaporation and sputtering and introducing plasma-assisted bombardment during deposition, it significantly enhances the coating density and interfacial strength [28,29].

Among the various PVD technologies, magnetron sputtering and arc ion plating (AIP) have emerged as predominant methods for the preparation of Cr-N coatings, owing to their superior comprehensive performance. They are primarily applied in large-scale continuous production fields such as precision bearings, plastic molds, and high-end decorative coatings, where requirements include low friction, aesthetic appeal, and avoidance of surface contamination.

Magnetron sputtering employs an orthogonal electromagnetic field on the cathode target surface, which confines the trajectory of the secondary electrons and extends their path within the plasma. This process enhances the likelihood of gas ionization, thereby facilitating the generation of a high-density plasma. This technology is characterized by a low deposition temperature, excellent coating uniformity and a wide range of usable target materials, rendering it suitable for coating large areas and substrates with complex geometries. Nevertheless, its ionization rate is generally low, and the efficiency of target material utilization requires further improvement.

To enhance the ionization rate, current research primarily focuses on improvements in magnetic field distribution, power supply, ion source coupling, and cathode design. By directly modifying the power supply, HiPIMS can achieve a higher ionization rate. Liu et al. [30] utilized this approach to form Cr-N anti-corrosion coatings on brass substrates. Through optimization of process parameters (pulse frequency, pulse width, and N2 flow rate) and structural design, high film density and excellent corrosion resistance were obtained. During the preparation of high-quality Cr-N coatings, nitrogen gas acts as the reactive gas, forming nitride coatings with metal atoms on the substrate. However, variations in N2 flow rate can lead to fluctuations in the deposition rate of nitride on the target surface and deterioration of film quality, exhibiting a noticeable hysteresis effect.

Additionally, applying bias voltage to the substrate can also enhance the performance of coatings. Building upon HiPIMS, Wu et al. [31] applied high-pulse bias voltage to the substrate at the same frequency or integer multiples of the frequency, modulating pulse width and phase through a matching circuit. Compared to those prepared by conventional magnetron sputtering and HiPIMS, the Cr-N coatings produced with this setup exhibited higher thermal stability and oxidation resistance, 300 °C higher than conventional Cr-N coatings, while also achieving a higher deposition rate.

AIP, also referred to as CAE, generates high-temperature and high-density arc spots on the cathode target surface through arc discharge. This causes the charged target material to rapidly evaporate and become highly ionized, accelerating toward the substrate under the influence of the substrate’s negative bias voltage. The resulting coatings demonstrate excellent adhesion to the substrate, superior throwing power, and high deposition rate. It has become a crucial technique for preparing wear-resistant coatings on tools and molds. However, the AIP process is susceptible to the formation of micro-sized droplets, which can result in surface defects and increased roughness in the coatings, thereby affecting their density and mechanical properties. Currently, the generation of droplets is mitigated to a certain extent by optimizing the stability of the power supply, the microstructure of the target material, compositional uniformity, and optimal magnetic field distribution, thereby improving coating quality [32,33].

Heo et al. [34] investigated the effect of bias voltage on phase transformation and coating microstructure evolution. It was found that within the 0 to −400 V bias range, the coating primarily consisted of the CrN phase. A maximum hardness of approximately 30 GPa was achieved at a bias voltage of −200 V, accompanied by the formation of a Cr-Mo-N coating, which contributed to a reduction in the coefficient of friction.

Additionally, the N2 flow rate is a critical parameter for controlling the composition and properties of the coatings. Its interaction with plasma dynamics under the influence of magnetic fields involves a nonlinear and complex dynamic process, resulting in a hysteresis effect in the coating properties as the flow rate varies.

In summary, both magnetron sputtering and AIP have unique characteristics and play crucial roles in the preparation of Cr-N coatings. The rational selection and control of the process parameters have a decisive impact on the final mechanical properties of the coatings.

3. Structural Evolution and Mechanical Properties of Monolayer Cr-N Coating

3.1. Mechanism of Structural Evolution in Monolayer Cr-N Coating

Cr-N coatings are deposited by exciting high-energy active nitrogen particles from a target onto the substrate, making N2 partial pressure a critical process parameter. It influences the nitrogen content in the coating and governs the structural evolution of Cr-N coatings. Specifically, lower N2 partial pressure tends to form the sub-nitride phase Cr2N. As N2 partial pressure increases, a mixed-phase structure of Cr2N and CrN develops. Further elevation to high N2 partial pressure promotes the formation of the nitrogen-rich CrN phase [35,36]. Additionally, the thermodynamic stability of different coating structures varies. The Cr2N phase is relatively stable, while CrN is prone to decomposition into Cr2N at elevated temperatures. Higher N2 partial pressure can suppress this decomposition reaction. Notably, variations in N2 partial pressure also affect the growth orientation of deposited grains. The CrN phase possesses a face-centered cubic (FCC) structure and exhibits a preferred (111) close-packed orientation under nitrogen-rich conditions [36]. Consequently, the structural evolution of Cr-N coatings dictates their hardness, adhesion strength, and tribological properties.

3.2. Hardness of Monolayer Cr-N Coating

The hardness of Cr-N coatings is a key indicator for evaluating their performance as protective coatings. It is mainly influenced by factors such as the chemical composition, crystal structure, microstructure, and process parameters (e.g., N2 partial pressure or flow rate) [37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. Therefore, precise control of the deposition conditions is crucial for achieving coatings with the desired hardness values. Various researchers have conducted systematic studies on these factors. Table 1 summarizes the hardness range of monolayer Cr-N coating under different process conditions, with values ranging from 15.3 to 29 GPa. Among these, MPP and DOMS stand for Modulated Pulsed Power and Deep Oscillation Magnetron Sputtering, respectively.

Table 1.

Hardness of monolayer Cr-N coating with different process conditions.

In terms of hardness analysis, it is important to determine its correlation with grain size and residual stress. Residual stress typically inhibits plastic deformation of materials, exhibiting a positive correlation with hardness. When grain size is refined to the nanoscale, its relationship with hardness follows the Hall-Petch effect. Meanwhile, finer coating grain size can further increase residual stress [56,57]. Gelfi et al. [58] deposited a CrN single crystal on an H11 tool steel substrate, achieving an ultra-high hardness coating with compressive residual stress on the coating surface exceeding −2 GPa. Mayrhofer et al. [59] found that the maximum hardness of the CrN phase can reach 38.4 GPa, closely related to ultrafine grain size and high residual stress. Wiecinski et al. [60] prepared high-quality Cr-N coatings on the surface of Ti6Al4V titanium alloy, featuring a uniform nanocrystalline structure free of pores and cracks, leading to significant improvements in hardness and Young’s modulus.

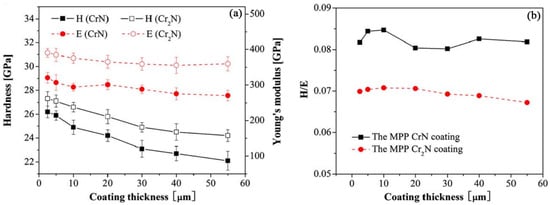

Lin et al. [50] investigated the mechanical properties of Cr-N and Cr2N coatings, which were prepared using MPP magnetron sputtering, with a focus on the influence of thickness. By varying the N2 flow (Ar/N2 ratios of 1:1 and 3:1), distinct phases of cubic Cr-N and hexagonal Cr2N coatings were obtained. At equivalent thicknesses, the Cr2N coating demonstrated superior hardness and Young’s modulus, attributed to its finer grain structure and reduced surface roughness. In contrast, the Cr-N coating exhibited a higher H/E ratio (Figure 1), indicating enhanced toughness and elastic strain tolerance, which facilitated load redistribution and delayed coating failure. Overall, the N2 flow determined the phase composition, which subsequently influenced the grain structure, stress state, and toughness.

Figure 1.

(a) Hardness and Young’s modulus, and (b) the H/E ratios of the MPP sputtered CrN and Cr2N coatings with different coating thicknesses [50].

In terms of microstructure, Bai et al. [49] compared Cr-N coatings produced using HiPIMS and DCMS. The increased plasma ionization in HiPIMS significantly refined the Cr-N grains, resulting in a nanocrystalline structure that substantially enhanced the hardness.

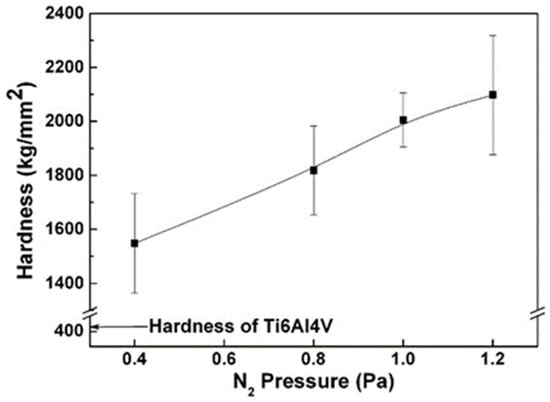

The N2 supply is another critical parameter. As shown in Figure 2, Chang et al. [45] deposited Cr-N on Ti6Al4V using CAE and observed that increasing the N2 pressure from 0.4 Pa to 1.2 Pa progressively augmented nitrogen content, optimized the structure, and elevated microhardness from approximately 1540 kg mm−2 to 2080 kg mm−2. Gui et al. [61] examined the impact of N2 flow on Cr-N coatings prepared by modulated pulsed-power magnetron sputtering; hardness increased with flow up to 100 sccm, then decreased. The initial increase was attributed to the higher density and grain refinement, while excessive N2 reduces the coating density.

Figure 2.

Hardness changes of CrN coating deposited on TI6Al4V substrate by AIP under different N2 pressure [45].

3.3. Adhesion Strength of Monolayer Cr-N Coating

The adhesion strength of a coating is a measure of its resistance or stability when exposed to external forces and is typically defined by the adhesive force and critical load. The adhesive force is the minimum stress required to delaminate a unit-area coating from its substrate, whereas the critical load is the smallest external force at which the coating begins to fail. Several factors influence the coating adhesion strength, including the deposition process, substrate hardness, coating thickness, and interfacial reactions [50,51]. Table 2 presents the adhesion strengths of the monolayer Cr-N coating under various processing conditions. For Cr-N coatings deposited via the MMP method, the critical load generally ranged from 55 to 100 N; similarly, for Cr-N coatings deposited by the CAE method, the range was 50–100 N. An increase in N2 pressure from 0.5 to 3.0 Pa resulted in a significant increase in the critical load of the Cr-N coating from 50–65 to 90–100 N, comparable to the MMP process. In contrast, Cr-N coatings deposited by DCMS exhibited a critical load of approximately 30 N, which is notably lower than that of the former two methods; specific values are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Adhesion strength of monolayer Cr-N coating with different process conditions.

Kim et al. [62] controlled the hardness-to-elastic modulus ratio of the Cr-N interlayer to achieve an optimal combination between the Cr-N interlayer and the WC-6 wt.% Co substrate. Employing the optimal H/E gradient ratio significantly improved the coating adhesion strength. Renzelli et al. [63] investigated the influence of residual stress distribution at different thicknesses on coating adhesion based on an AISI 304 stainless steel substrate. It was found that compressive residual stress can inhibit crack nucleation and propagation, thereby enhancing the coating’s adhesion and service toughness.

Jeong et al. [34] found that owing to their high hardness and elastic modulus, CrN coatings exhibit good load-bearing capacity on steel substrates, with the critical load increasing with the coating thickness. In comparison, Cr2N coatings, which are more brittle, generally have lower critical loads than Cr-N coatings of the same thickness on various substrates. Zhang et al. [51] employed DCMS to deposit Cr-N coatings on 304 stainless steel and observed that the relatively low substrate hardness led to coating cracking or even delamination, indicating that substrate hardness plays a crucial role in adhesion performance. Ou et al. [64] reported that the critical load increases with rising coating hardness, further confirming the dependence of coating adhesion on substrate hardness. Zhang et al. [65] also noted that CrN coatings deposited on soft substrates suffer from lower adhesion strength owing to the larger plastic deformation capacity and poorer support of the substrate, whereas hard substrates facilitate improved coating–substrate bonding.

Ding et al. [66] investigated the substrate compatibility of Cr-based protective coatings by depositing Cr/Cr2N layers on various pretreated substrates using DCMS and HiPIMS. They discovered that nitrogen pretreatment significantly enhanced the coating performance: the adhesive force increased from 49 N to 76 N (a 55% increase), grain refinement raised the hardness by 14%, and the fracture toughness improved by 48%.

Warcholinski et al. [52] employed CAE to deposit Cr-N coatings on both sides of steel substrates, finding that higher N2 flow rates raise the critical load of the front-side coating; the back-side coating, due to a lower deposition rate and fewer defects, also exhibited relatively high critical loads. Ji et al. [67] used AIP to produce Cr-N coatings on valve seats and demonstrated that the adhesive force initially increased and then decreased with increasing arc current. Excessively high arc currents generate larger particles in the vacuum chamber, which adhere to the coating, increasing surface roughness and degrading adhesion.

Zhong et al. [68] conducted a study on (Ti, Cr) N coatings with varying Ti/Cr ratios, fabricated through multi-AIP, to systematically investigate the influence of target composition on the properties of the coatings. Their findings indicated that the actual composition of the coatings was significantly influenced by the ionization rates of the individual metals, deviating from the target composition. Utilizing an alloy target with a Ti:Cr weight ratio of 4:1, they achieved Ti0.6Cr0.2N coating exhibited the highest microhardness, which markedly exceeded that of the pure TiN and pure CrN coatings. This improvement was attributed to solid-solution strengthening and lattice distortion resulting from the dissolution of Cr atoms in the TiN lattice.

3.4. Tribological Performance of Monolayer Cr-N Coating

The tribological performance of Cr-N coatings directly determines their service life and effectiveness under actual friction-wear conditions. Generally, high hardness combined with a low coefficient of friction (COF) indicates excellent wear resistance. The key factors influencing the tribological behavior include coating thickness, surface roughness, microstructure, coating-substrate adhesion, and process parameters (e.g., N2 flow rate).

In addition, specific tribological testing conditions such as counterbody, temperature, and lubrication also influence friction and wear performance. Among them, the counterbody determines the combined characteristics of the Cr-N coating system; temperature can alter its hardness, lubricant viscosity, and chemical reactions; and lubricants play a central role in reducing friction and isolating wear. Together, these three factors modify the adhesion and shear forces at the contact interface, thereby significantly affecting the magnitude and stability of the friction coefficient [69].

Superior wear resistance can markedly extend the component lifespan, improve operational efficiency, and reduce maintenance costs. Table 3 summarizes the COF values of monolayer Cr-N coatings prepared under various conditions, ranging from 0.13 to 0.72; the COF of Cr2N coatings is approximately 0.5.

Table 3.

Friction coefficients of monolayer Cr-N coating with different preparation conditions.

Ji et al. [67] employed multi-AIP to deposit CrN coatings on the surface of ductile cast iron valve seats and systematically investigated how the arc current regulated the coating structure and frictional properties. The experimental conditions were set at 25 °C, with friction and wear tests conducted using a GCr15 ball with a diameter of 3 mm. They found that increasing the arc current from 55 A to 70 A raised the content of the hard Cr2N phase, with optimal overall performance achieved at 65 A: the nanohardness reached 18.84 GPa, the adhesive force was 49.2 N, the substrate COF was reduced from 0.62 to 0.48, and the self-removal of Cr2N during wear further enhanced the resistance to abrasive wear.

Jasempoor et al. [55] studied the tribological behavior of monolayer Cr-N coating deposited by CAE on AISI 304 stainless steel. The layered structure of CrN effectively suppressed dislocation motion and micro crack propagation, lowering the COF from 0.57 to 0.38 and significantly improving the wear resistance of the substrate. Vicen et al. [46] prepared CrN coatings on high- and medium-carbon C55 steel by DCMS and observed a pronounced COF reduction and excellent wear performance.

Alam et al. [73] revealed the mechanism by which substrate bias influences the magnetic properties of Fe/CrN bilayers. The bias-induced interfacial modification strengthens the antiferromagnetic exchange coupling between the Fe and CrN layers. For a structure comprising 151 nm CrN and 53 nm Fe, this coupling manifests at low temperature as a macroscopic exchange bias field and exchange-spring behavior, with a blocking temperature close to the Néel temperature of CrN. The bias primarily alters the interfacial defects and stress, enhancing spin pinning at the interface, which shifts the hysteresis loop and stabilizes planar domain walls under non-easy-axis magnetic fields.

However, researchers still hold differing views on the influence of substrate bias on coating properties. Warcholinski et al. [74] found that coatings deposited under low bias voltage exhibited a dense polycrystalline structure with columnar grains, whereas a uniform and fine morphology was obtained at high bias voltage. At higher bias voltages, the compressive residual stress significantly decreased. The maximum hardness of CrN coatings deposited at −150 V bias reached 25 GPa. In contrast, Lomello et al. [75] observed that as the negative substrate bias increased from 0 to −150 V, the grain size was significantly refined, while the compressive residual stress first decreased and then increased, and the hardness first rose and then declined. Notably, the sample deposited at −100 V showed the highest hardness (50 ± 2 GPa).

Liu et al. [47] conducted a study in which Cr-N coatings were deposited via AIP on substrates of AISI 1045 steel, H13 steel, and H2205 duplex stainless steel. This study focused on the corrosion-wear behavior of these coatings in a 3.5% NaCl solution. The findings indicate that Cr-N coatings significantly decrease the friction corrosion rate of carbon steel. In contrast, the application of Cr-N coatings to stainless steel resulted in a negative synergistic effect, suggesting that the properties of the substrate play a crucial role in influencing the friction-corrosion mechanism. Under varying N2 flow rates, the COF for the Cr-N coatings ranged from 0.5 to 0.75, thereby confirming their superior wear resistance. Ji et al. [67] observed that when Cr-N coatings are applied to valve seats using AIP, an increase in arc current enhances the evaporation of Cr particles. In an adequate N2 atmosphere, this resulted in the formation of more CrN and Cr2N, leading to thicker coatings and a reduction in the COF from 0.55 to 0.45. This demonstrates that process parameters can be adjusted to optimize the tribological performance by modifying the phase composition and structure of the coating.

4. Structural Design and Mechanical Properties of Multilayer Cr-N Coatings

4.1. Structural Design of Multilayer Cr-N Coatings

As the demand for comprehensive performance of Cr-N coatings in industrial applications continues to grow, the design concept of multilayer deposited coatings has been proposed, which extends beyond simple stacking of Cr-N systems to include the combination of multiple nitrides. Multilayer Cr-N coatings are composite coating systems formed by alternately depositing two or three different chemical compositions or structures of Cr-N coatings (such as CrN, Cr2N, Cr, etc.), with individual layer thickness typically ranging from several nanometers to tens of nanometers. Compared with monolayer coating, this multilayer structure introduces a high density of interfaces, which can effectively hinder dislocation motion, suppress crack propagation, and modulate internal stress distribution, thereby significantly improving the overall mechanical properties of the coating. Extensive studies have shown that multilayer coatings often exhibit superior characteristics over single-material coatings in terms of hardness, toughness, adhesion strength, and tribological performance [76].

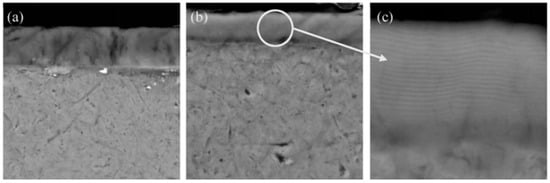

Figure 3 presents cross-sectional micro-morphologies of typical monolayer and multilayer Cr-N coatings, clearly showing a much denser structure in the multilayer coatings. Among the design parameters, material combination, bilayer period, and layer thickness ratio significantly influence the final coating properties. For example, Wu et al. [77] prepared multilayer CrSiN/TiAlN coatings to achieve an optimal balance of hardness, toughness, and tribological performance. They found that when the layer thickness ratio was 1:1 and the bilayer period was 10 nm, the multilayer coating reached its maximum hardness. Moreover, increasing the thickness of the TiAlN layers could enhance both hardness and toughness.

Figure 3.

AISI 304 stainless steel (a) Monolayer CrN coating cross-section, (b) Multilayer Cr/CrN coating cross-section, (c) Multilayer coating cross-section under localized magnification [55].

In addition, Kot et al. [78] deposited multilayer Cr/CrN coatings on AISI 301 steel using pulsed laser deposition and demonstrated that the mechanical properties of the multilayer coating were primarily governed by the bilayer period. Compared with monolayer Cr-N coating, the multilayer coatings significantly improved both the critical load and the Young’s modulus.

As reviewed by Cong et al. [79], employing TiCrN as the top layer in conjunction with TiCrAlN to create TiCrAlN/TiCrN composite coatings, or incorporating a CrN interlayer, can significantly enhance the adhesion between the coating and substrate, as well as the overall tribological performance. This approach presents a novel strategy for designing multilayers with high hardness, robust adhesion, and superior wear resistance.

4.2. Hardness of Multilayer Cr-N Coatings

The hardness of multilayer coatings is influenced not only by the intrinsic hardness of each constituent layer but also by the synergistic effects of the modulation period (individual layer thickness), interface density, interface structure, and compositional ratios of the components. Owing to mechanisms such as interface strengthening, dislocation blocking, and the Hall-Petch effect, multilayer architectures often exhibit hardness enhancements that surpass the average level of the individual constituent materials. Table 4 summarizes the hardness values of the multilayer Cr-N coatings prepared under various processing conditions, ranging from 16.8 to 31.6 GPa.

Table 4.

Hardness of multilayer Cr-N coatings with different process conditions.

Shan et al. [82] fabricated Cr/Cr2N/CrN multilayer coatings and monolayer CrN coating on 316L stainless steel substrates using AIP. They observed that the multilayer coatings exhibited slightly lower hardness than the monolayer CrN coating but were marginally higher than the expected value for a conventional mixture of Cr, Cr2N, and CrN. The authors attributed this to the introduction of a ductile Cr layer, which, while reducing the overall hardness to some extent, contributed to a relatively high hardness through plastic deformation and interface-induced dislocation hindrance.

Song et al. [80] deposited multilayer Cr/CrN coatings with varying numbers of bilayer periods on 304 stainless steel substrates. Their study found that as the number of periods increased, both the hardness and elastic modulus of the coatings increased slightly; however, they remained lower than those of monolayer Cr-N coating. A higher volume fraction of the softer Cr layers in the multilayer stack led to a reduction in the overall hardness.

Jasempoor et al. [55] pointed out that the abundant interfaces in multilayer Cr/CrN coatings effectively impede dislocation motion, causing strain hardening; consequently, the average hardness of the multilayer exceeds that of monolayer Cr, and the elastic modulus is correspondingly enhanced. The research indicates that the hardness of multilayer coatings is closely related to the volume fraction of the ductile component; generally, the hardness decreases as the proportion of Cr layers increases [83].

4.3. Adhesion Strength of Multilayer Cr-N Coatings

The adhesion strength between multilayer Cr-N coatings and substrates is typically evaluated using the critical load. Studies have shown that the critical load of multilayer coatings is slightly lower than that of monolayer Cr-N coating and tends to decrease as the number of bilayer periods increases [66,80]. Additionally, factors such as the chemical composition of the interlayers, interfacial bonding state, coating thickness, and hardness significantly influence adhesion strength [60,84,85,86,87,88,89]. Table 5 lists the critical load range (15.2–80 N) of the multilayer Cr-N coatings under different preparation conditions. It can be observed that the interlayer elements, substrate materials, and deposition processes have a notable impact on adhesion performance.

Table 5.

Adhesion strength of multilayer Cr-N coatings with different process conditions.

Hu et al. [90] adjusted the modulation period by varying the deposition time of the Cr layer and employed AIP to fabricate three dense, uniform, and thick multilayer Cr/CrN coatings on stainless-steel substrates. Their findings indicated that an increase in the Cr layer thickness resulted in a gradual decrease in the in-plane residual stress within the coating, thereby mitigating the adverse impact of stress on adhesion strength. Cai et al. [93] highlighted that the introduction of a ductile Cr layer as an interlayer within a multilayer architecture effectively suppresses brittle fracture and impedes crack propagation, thus enhancing the overall adhesion strength of the multilayer coating. Shan et al. [82] further emphasized that the incorporation of a ductile Cr layer contributes to improved adhesion of the multilayer coating. Additionally, the thickness ratio between the ductile Cr layer and the brittle Cr-N layer is crucial for the overall plasticity of the multilayer system. Under external loading, the plastic deformation of the ductile Cr layer may cause the Cr-N layer to reach a critical deformation state during fatigue loading, thereby influencing the adhesion performance of multilayer Cr-N coatings. Jasempoor et al. [55] demonstrated that depositing an initial Cr layer at the onset of the multilayer deposition process significantly enhances the coating’s adhesion strength. This Cr layer forms strong metal-covalent bonds with the transition layer (Cr2N), effectively suppressing the migration of the transition layer toward the substrate. Furthermore, the Cr layer can establish metallic bonds with the substrate, providing robust attachment while allowing the substrate to undergo plastic deformation and grain refinement without compromising adhesion. Renzelli et al. [63] discovered that the adhesion strength of the coating is primarily correlated with its average residual stress, while the stress gradient through the thickness has a relatively minor effect. Reducing compressive stress at the interface and minimizing the through-thickness stress gradient can further enhance the coating’s adhesion strength.

4.4. Tribological Properties of Multilayer Cr-N Coatings

Compared with monolayer coating, multilayer Cr-N coatings exhibit superior wear resistance under sliding friction. In monolayer systems, the high local contact pressure between the counterpart and the coating readily induces plastic deformation and adhesive wear, leading to coating spallation or delamination [92]. Introducing a ductile Cr interlayer into the multilayer stack enables efficient stress absorption and redistribution, allowing the coating to sustain larger plastic strains; consequently, multilayer Cr-N coatings containing Cr interlayers usually display better tribological performance [94,95]. Table 6 summarizes the friction coefficients measured for various multilayer Cr-N coatings deposited by different techniques and tested against several counterface materials. The coefficients range from 0.13 to 0.62, and both the absolute values and the wear resistance depend strongly on the deposition conditions.

Table 6.

Friction coefficients of multilayer Cr-N coatings with different preparation conditions.

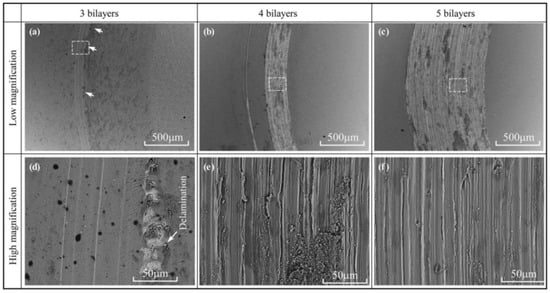

Yonekura et al. [91] prepared multilayer Cr/CrN coatings on Ti6Al4V substrates using AIP technology and investigated the effect of bilayer number on fatigue and wear performance. The wear tests were performed using a pin-on-disk type wear tester (CSEM, Tribometer, Neuchatel, Switzerland) under a vertical load of 1 N, sliding speed of 10 mm/s, wear track radius of 3.0 mm and sliding distance of 100 m. The study found that multilayer coatings improved fatigue strength. However, samples with a higher number of bilayers exhibited poorer wear resistance. This is attributed to the fact that the thinner CrN layers, with a hardness approximately 2.5 times that of the Cr layers, acted as abrasive particles during sliding, forming sharp grooves on the wear track. These grooves were prone to cracking and delamination from the underlying layers during the friction process. The specific morphology is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Wear morphology of multilayer Cr/CrN coatings with different number of bilayers deposited on Ti6Al4V alloy. (a) 3 bilayers with low magnification, (b) 4 bilayers with low magnification, (c) 5 bilayers with low magnification, (d) 3 bilayers with high magnification, (e) 4 bilayers with high magnification, (f) 5 bilayers with high magnification, [91].

Arias et al. [96] deposited multilayer Cr/Cr-N coatings on Si wafers by magnetron sputtering with various modulation periods and systematically evaluated their wear behavior. The wear rate decreased progressively as the number of bilayers increased, whereas the friction coefficient remained essentially constant. Hu et al. [90] observed that higher CrN content in multilayer Cr/CrN coatings led to lower friction coefficients. In addition, an appropriate thickness of ductile Cr can alleviate stress concentration at CrN/Cr interfaces by deflecting cracks or promoting plastic deformation, thereby enhancing overall wear resistance [92]. Wang et al. [97] investigated the high-temperature tribological response of multilayer Cr-N coatings and found that the friction coefficient decreased with increasing temperature, while the wear rate rose markedly. This is attributed to softening of the Cr layers at elevated temperature, which reduces the overall hardness of the multilayer and makes it more susceptible to wear.

In summary, monolayer Cr-N coating are mature and widely applied as hard coatings for room-temperature applications. Through the tailored design of multilayer Cr-N coatings, even higher hardness, adhesion strength, and tribological performance have been achieved. However, with the increasing demand for high-speed, high-efficiency, and high-temperature material processing, new challenges have emerged regarding the thermal stability and oxidation resistance of coatings. To expand the application of novel coatings, researchers have designed and developed new multicomponent Cr-N coatings. For example, the Cr-Al-N system significantly enhances coating hardness and thermal stability through the formation of strong co-valent Al-N bonds [98]. The quaternary Cr-Al-Si-N system has been proposed, where the addition of Si pro-motes spinodal decomposition, forming high-temperature-resistant amorphous SiNx phases, further improving thermal stability [99].

5. Conclusions and Outlook

Physical vapor deposition technology enables precise control of process parameters to effectively adjust the microstructure of Cr-N coatings, thereby achieving coating systems with superior mechanical properties. This review systematically encapsulates the research advancements on the mechanical properties of PVD-fabricated Cr-N coatings, with the principal conclusions outlined as follows:

- (1)

- The mechanical properties of monolayer Cr-N coating are primarily determined by the deposition process. The optimization of critical parameters such as bias voltage, arc current, and N2 flow rate directly modulates the coating’s microstructure, thereby significantly affecting the hardness, adhesion strength, and wear resistance.

- (2)

- In multilayer architectures, the inclusion of a ductile Cr layer substantially impacts the hardness and adhesion strength of multilayer Cr-N coatings. As the number of bilayer periods decreases or the volume fraction of the ductile Cr phase increases, the coating hardness generally exhibits a declining trend. Conversely, pre-depositing a Cr transition layer on the substrate or increasing the thickness of the interlayer Cr enhances the adhesion strength of multilayer Cr-N coatings.

- (3)

- The tribological performance of multilayer Cr-N coatings is primarily determined by the CrN phase content and the modulation period (number of bilayers). A higher CrN content in multilayer Cr/CrN coatings generally results in a lower coefficient of friction. Meanwhile, the wear rate decreases as the number of bilayers increases, indicating that the nanoscale multilayer structure can effectively mitigate material loss through interfacial effects.

- (4)

- Monolayer Cr-N coatings benefit from a mature process and cost-effectiveness, making them suitable for applications such as injection molds and general machining/cutting tools. In contrast, multilayer Cr-N coatings exhibit superior overall performance and hold broader application prospects in areas such as biomedical protection, processing of difficult-to-machine materials, and service under extreme working conditions.

In conclusion, Cr-N coatings fabricated through PVD present notable advantages, including process flexibility and adjustable performance, indicating extensive potential applications in the surface protection of advanced equipment. Future research may further explore the following areas: For various substrates and service environments, it is essential to integrate high-throughput preparation and artificial intelligence technologies to establish correlations among process parameters, microstructure, and performance, thereby facilitating the intelligent optimization of Cr-N coating design and processes. A systematic investigation into the mechanical behavior and evolution mechanisms at the coating-substrate and interlayer interfaces is necessary to elucidate the mechanisms of strengthening, toughening, and wear resistance under multi-interface synergy, providing theoretical guidance for the design of high-performance multilayer Cr-N coatings. Furthermore, it is imperative to address strategic national demands in the aerospace, defense equipment, and new energy sectors by developing multilayer Cr-N coating systems that combine superior mechanical properties, corrosion resistance, and erosion resistance, thereby promoting the engineering application and industrial adoption under extreme operating conditions.

Author Contributions

G.W.: Conceptualization, Writing and Editing; X.W.: Validation and Editing; Y.J.: Validation and Editing; C.G.: Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded the Liaoning Province Central Guidance for Local Science and Technology Development Special Project (2024JH6/100900007), and Liaoning Provincial Doctoral Research Start-up Foundation Project (2025-BS-0356).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, A.; Deng, J.; Cui, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, J. Friction and wear properties of TiN, TiAlN, AlTiN and CrAlN PVD nitride coatings. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2012, 31, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.P.; Sun, Y.; Bell, T. Friction behaviour of TiN, CrN and (TiAl)N coatings. Wear 1994, 173, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, R.J.; García, J.A.; Medrano, A.; Rico, M.; Sánchez, R.; Martínez, R.; Labrugère, C.; Lahaye, M.; Guette, A. Tribological behaviour of hard coatings deposited by arc-evaporation PVD. Vacuum 2002, 67, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanno, Y.; Azushima, A. Effect of counter materials on coefficients of friction of TiN coatings with preferred grain orientations. Wear 2009, 266, 1178–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Liu, A. Dry sliding wear behavior of PVD TiN, Ti55Al45N, and Ti35Al65N coatings at temperatures up to 600 °C. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2013, 41, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Wu, F.; Lian, Y.; Xing, Y.; Li, S. Erosion wear of CrN, TiN, CrAlN, and TiAlN PVD nitride coatings. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2012, 35, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelleg, J.; Zevin, L.Z.; Lungo, S.; Croitoru, N. Reactive-sputter-deposited TiN films on glass substrates. Thin Solid Films 1991, 197, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeyama, M.B.; Noya, A.; Sakanishi, K. Diffusion barrier properties of ZrN films in the Cu/Si contact systems. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 2000, 18, 1333–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.L.; Cheng, G.A.; Zheng, R.T.; Liu, H.P. Fabrication and performance of TiN/TiAlN nanometer modulated coatings. Thin Solid Films 2011, 520, 813–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalnezhad, E.; Sarhan, A.A.D.M.; Hamdi, M. Surface hardness prediction of CrN thin film coating on AL7075-T6 alloy using fuzzy logic system. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Man. 2013, 14, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalnezhad, E.; Sarhan, A.A.D. Multilayer thin film CrN coating on aerospace AL7075-T6 alloy for surface integrity enhancement. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Tech. 2014, 72, 1491–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalnezhad, E.; Sarhan, A.A.D.; Hamdi, M. Fretting fatigue life evaluation of multilayer Cr–CrN-coated Al7075-T6 with higher adhesion strength—Fuzzy logic approach. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Tech. 2013, 69, 1153–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.C.; Feng, H.; Li, H.B.; Ling, M.H.; Wang, H.J.; Zhu, H.C.; Zhang, S.C.; Ni, Z.W.; Liu, Z.Q.; Jiang, Z.H. A strategy to overcome the negative effect of Mg treatment on localized corrosion and enhance the performance of high-nitrogen martensitic stainless steel by Mg&Ce composite treatment. Corros. Sci. 2025, 249, 112852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Song, P.; Zhang, R.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Du, P.; Lu, J. Oxidation behavior and Cr-Zr diffusion of Cr coatings prepared by atmospheric plasma spraying on zircaloy-4 cladding in steam at 1300 °C. Corros. Sci. 2022, 203, 110378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P.; Awasthi, S.; Ramkumar, J.; Balani, K. Protective trivalent Cr-based electrochemical coatings for gun barrels. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 768, 1039–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayón, R.; Igartua, A.; Fernández, X.; Martínez, R.; Rodríguez, R.J.; García, J.A.; de Frutos, A.; Arenas, M.A.; de Damborenea, J. Corrosion-wear behaviour of PVD Cr/CrN multilayer coatings for gear applications. Tribol. Int. 2009, 42, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Cherng, J.S.; Chen, Q. Recent progress on high power impulse magnetron sputtering (HiPIMS): The challenges and applications in fabricating VO2 thin film. AIP Adv. 2019, 9, 35242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhafian, M.R.; Chemin, J.B.; Fleming, Y.; Bourgeois, L.; Penoy, M.; Useldinger, R.; Soldera, F.; Mücklich, F.; Choquet, P. Comparison on the structural, mechanical and tribological properties of TiAlN coatings deposited by HiPIMS and Cathodic Arc Evaporation. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 423, 127529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, E.; Loch, D.; Montagne, A.; Ehiasarian, A.P.; Patscheider, J. Comparison of Al–Si–N nanocomposite coatings deposited by HIPIMS and DC magnetron sputtering. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2013, 232, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, N.; Rebelo de Figueiredo, M.; Franz, R.; Sánchez-López, J.C.; Rojas, T.C.; Fernández de los Reyes, D.; Colominas, C.; Abad, M.D. Microstructure and mechanical properties of TiN/CrN multilayer coatings deposited in an industrial-scale HiPIMS system. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 515, 132581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobzin, K.; Brögelmann, T.; Kalscheuer, C.; Thiex, M. Self-lubricating triboactive (Cr,Al)N+Mo:S coatings for fluid-free applications. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 15040–15060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Bharagava, R.N. Toxic and genotoxic effects of hexavalent chromium in environment and its bioremediation strategies. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part C 2016, 34, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, R.; Nandi, R.; Saha, B. Sources and toxicity of hexavalent chromium. J. Coord. Chem. 2011, 64, 1782–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobzin, K.; Brögelmann, T.; Kalscheuer, C. Arc PVD (Cr,Al,Mo)N and (Cr,Al,Cu)N coatings for mobility applications. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 384, 125046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Martin, C.; Ajayi, O.; Erdemir, A.; Fenske, G.R.; Wei, R. Effect of microstructure and thickness on the friction and wear behavior of CrN coatings. Wear 2013, 302, 963–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalk, N.; Tkadletz, M.; Mitterer, C. Hard coatings for cutting applications: Physical vs. chemical vapor deposition and future challenges for the coatings community. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2022, 429, 127949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, E.; Offoiach, R.; Regis, M.; Fusi, S.; Lanzutti, A.; Fedrizzi, L. Diffusive thermal treatments combined with PVD coatings for tribological protection of titanium alloys. Mater. Des. 2016, 89, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchette, F.; Ducros, C.; Schmitt, T.; Steyer, P.; Billard, A. Nanostructured hard coatings deposited by cathodic arc deposition: From concepts to applications. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2011, 205, 5444–5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehran, Q.M.; Fazal, M.A.; Bushroa, A.R.; Rubaiee, S. A critical review on physical vapor deposition coatings applied on different engine components. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2018, 43, 158–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.C.; Hsiao, S.N.; Chen, Y.H.; Hsieh, P.Y.; He, J.L. High-power impulse magnetron sputter-deposited chromium-based coatings for corrosion protection. Coatings 2023, 13, 2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Tian, X.; Xiao, S.; Gong, C.; Pan, F.; Chu, P.K. High temperature oxidation of Cr–N coatings prepared by high power pulsed magnetron sputtering—Plasma immersion ion implantation & deposition. Vacuum 2014, 108, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, W.C.; Xiao, J.Q.; Gong, J.; Sun, C.; Huang, R.F.; Wen, L.S. Study on cathode spot motion and macroparticles reduction in axisymmetric magnetic field-enhanced vacuum arc deposition. Vacuum 2010, 84, 1111–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oks, E.M.; Savkin, K.P.; Yushkov, G.Y.; Nikolaev, A.G.; Anders, A.; Brown, I.G. Measurement of total ion current from vacuum arc plasma sources. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2006, 77, 3B504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong Heo, S.; Kim, S.W.; Yeo, I.W.; Park, S.J.; Oh, Y.S. Effect of bias voltage on microstructure and phase evolution of Cr–Mo–N coatings by an arc bonded sputter system. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 5231–5237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.S.; Zhao, S.S.; Yang, Y.; Gong, J.; Sun, C. Effects of nitrogen pressure and pulse bias voltage on the properties of Cr–N coatings deposited by arc ion plating. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2010, 204, 1800–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Tian, J.; Lai, Q.; Yu, X.; Li, G. Effect of N2 partial pressure on the microstructure and mechanical properties of magnetron sputtered CrNix films. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2003, 162, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tian, X.; Gong, C.; Liu, X.; Li, J.; Zhu, J.; Lin, H. Effect of plasma nitriding ion current density on tribological properties of composite CrAlN coatings. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 3954–3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Ji, L.; Liu, X.; Li, H.; Zhou, H.; Chen, J. Influence of substrate bias voltage on structure and properties of the CrAlN films deposited by unbalanced magnetron sputtering. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012, 258, 3864–3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffmann, F.; Ji, B.; Dehm, G.; Gao, H.; Arzt, E. A quantitative study of the hardness of a superhard nanocrystalline titanium nitride/silicon nitride coating. Scr. Mater. 2005, 52, 1269–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zauner, L.; Hahn, R.; Aschauer, E.; Wojcik, T.; Davydok, A.; Hunold, O.; Polcik, P.; Riedl, H. Assessing the fracture and fatigue resistance of nanostructured thin films. Acta Mater. 2022, 239, 118260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Ruan, Q.; Xiao, S.; Meng, X.; Huang, C.; Wu, Y.; Fu, R.K.Y.; Chu, P.K. Fabrication and hydrogen permeation resistance of dense CrN coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2022, 437, 128326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigax, J.G.; El-Atwani, O.; McCulloch, Q.; Aytuna, B.; Efe, M.; Fensin, S.; Maloy, S.A.; Li, N. Micro- and mesoscale mechanical properties of an ultra-fine grained CrFeMnNi high entropy alloy produced by large strain machining. Scr. Mater. 2020, 178, 508–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Peng, J.; He, Z.; Xu, Z.; Li, W.; Wang, C. A novel fabrication strategy of single-phase and dense CrN ceramics and its tribological behavior. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 25613–25620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Lin, G.; Wu, B.; Shao, Z. Composition optimization of arc ion plated CrNx films on 316L stainless steel as bipolar plates for polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2012, 205, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.K.; Wan, X.S.; Pei, Z.L.; Gong, J.; Sun, C. Microstructure and mechanical properties of CrN coating deposited by arc ion plating on Ti6Al4V substrate. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2011, 205, 4690–4696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicen, M.; Kajánek, D.; Bokůvka, O.; Nikolić, R.; Medvecká, D. Resistance of the CrN coating to wear and corrosion. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 74, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, S. Tribocorrosion of CrN coatings on different steel substrates. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 484, 130829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Kuo, Y.C.; Wang, C.J.; Chang, L.C.; Liu, K.T. Effects of substrate bias frequencies on the characteristics of chromium nitride coatings deposited by pulsed DC reactive magnetron sputtering. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2008, 203, 721–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; Li, J.; Gao, J.; Ni, J.; Bai, Y.; Jian, J.; Zhao, L.; Bai, B.; Cai, Z.; He, J.; et al. Comparison of CrN coatings prepared using High-Power Impulse Magnetron Sputtering and direct current magnetron sputtering. Materials 2023, 16, 6303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Sproul, W.D.; Moore, J.J.; Lee, S.; Myers, S. High rate deposition of thick CrN and Cr2N coatings using modulated pulse power (MPP) magnetron sputtering. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2011, 205, 3226–3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.G.; Rapaud, O.; Bonasso, N.; Mercs, D.; Dong, C.; Coddet, C. Control of microstructures and properties of dc magnetron sputtering deposited chromium nitride films. Vacuum 2008, 82, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warcholinski, B.; Gilewicz, A.; Kuprin, A.S.; Kolodiy, I.V. Structure and properties of CrN coatings formed using cathodic arc evaporation in stationary system. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2019, 29, 799–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, F.; Oliveira, J.C.; Cavaleiro, A. CrN thin films deposited by HiPIMS in DOMS mode. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2016, 291, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S.J.; Huang, S.Q.; Guo, C.Q.; Dai, M.j.; Lin, S.s.; Shi, Q.; Su, Y.F.; Wei, C.B.; Yang, Z.; Chekan, N.M. Chromium arc plasma characterization, structure and properties of CrN coatings prepared by vacuum arc evaporation. Vacuum 2023, 209, 111796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasempoor, F.; Elmkhah, H.; Imantalab, O.; Fattah-alhosseini, A. Improving the mechanical, tribological, and electrochemical behavior of AISI 304 stainless steel by applying CrN single layer and Cr/CrN multilayer coatings. Wear 2022, 504–505, 204425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobzin, K.; Kalscheuer, C.; Möbius, M.P.; Aghdam, P.H. Residual stress analysis in high-speed physical vapor deposition coatings. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2024, 26, 2401095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tlili, B.; Nouveau, C.; Guillemot, G.; Besnard, A.; Barkaoui, A. Investigation of the effect of residual stress gradient on the wear behavior of PVD thin films. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2018, 27, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfi, M.; La Vecchia, G.M.; Lecis, N.; Troglio, S. Relationship between through-thickness residual stress of CrN-PVD coatings and fatigue nucleation sites. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2005, 192, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayrhofer, P.H.; Tischler, G.; Mitterer, C. Microstructure and mechanical/thermal properties of Cr-N coatings deposited by reactive unbalanced magnetron sputtering. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2001, 142, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiecinski, P.; Smolik, J.; Garbacz, H.; Kurzydlowski, K.J. Microstructure and mechanical properties of nanostructure multilayer CrN/Cr coatings on titanium alloy. Thin Solid Films 2011, 519, 4069–4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, B.; Zhou, H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, K.; Hu, H.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y. Influence of N2 flow rate on microstructure and properties of CrNx ceramic films prepared by MPP technique at low temperature. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 20875–20884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.K.; La, J.H.; Kim, K.S.; Lee, S.Y. The effects of the H/E ratio of various Cr-N interlayers on the adhesion strength of CrZrN coatings on tungsten carbide substrates. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2015, 284, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzelli, M.; Mughal, M.Z.; Sebastiani, M.; Bemporad, E. Design, fabrication and characterization of multilayer Cr-CrN thin coatings with tailored residual stress profiles. Mater. Des. 2016, 112, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y.X.; Lin, J.; Tong, S.; Sproul, W.D.; Lei, M.K. Structure, adhesion and corrosion behavior of CrN/TiN superlattice coatings deposited by the combined deep oscillation magnetron sputtering and pulsed dc magnetron sputtering. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2016, 293, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tian, X.B.; Zhao, Z.W.; Gao, J.B.; Zhou, Y.W.; Gao, P.; Guo, Y.Y.; Lv, Z. Evaluation of the adhesion and failure mechanism of the hard CrN coatings on different substrates. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 364, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.Y. Cr and Ta Based Coatings for Gun Barrel Protection via Physical Vapor Deposition: Preparation, Structure and Properties. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Science and Technology Beijing, Beijing, China, 2025. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Ji, C.; Guo, Q.; Li, J.; Guo, Y.; Yang, Z.; Yang, W.; Xu, D.; Yang, B. Microstructure and properties of CrN coating via multi-arc ion plating on the valve seat material surface. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 891, 161966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Shen, L.R.; Chen, M.y.; Liu, T.; Dan, M.; Jin, F.Y. Study on tribological properties of (Ti, Cr) N films. Vacuum 2020, 57, 27–32. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Pattnayak, M.R.; Ganai, P.; Pandey, R.K.; Dutt, J.K.; Fillon, M. An overview and assessment on aerodynamic journal bearings with important findings and scope for explorations. Tribol. Int. 2022, 174, 107778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R.; Carvalho, Ó.; Sobral, L.; Carvalho, S.; Silva, F. Influence of morphology and microstructure on the tribological behavior of arc deposited CrN coatings for the automotive industry. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 397, 126047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. Performance Study on TiN, CrN,TiAlN and TiAlN/Nitriding Composite Coating Preparated by PVD. Master’s Thesis, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China, 2015. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Guo, Q.; Qi, C.; Zhang, D.; Sun, H.; Wan, Y. Current-carrying friction behavior of CrN coatings under the influence of DC electric current discharge. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 494, 131356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, K.; Meng, K.Y.; Ponce-Pérez, R.; Cocoletzi, G.H.; Takeuchi, N.; Foley, A.; Yang, F.; Smith, A.R. Exchange bias and exchange spring effects in Fe/CrN bilayers. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2020, 53, 125001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warcholinski, B.; Gilewicz, A. Effect of substrate bias voltage on the properties of CrCN and CrN coatings deposited by cathodic arc evaporation. Vacuum 2013, 90, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomello, F.; Sanchette, F.; Schuster, F.; Tabarant, M.; Billard, A. Influence of bias voltage on properties of AlCrN coatings prepared by cathodic arc deposition. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2013, 224, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilewicz, A.; Warcholinski, B. Tribological properties of CrCN/CrN multilayer coatings. Tribol. Int. 2014, 80, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.K.; Lee, J.W.; Chan, Y.C.; Chen, H.W.; Duh, J.G. Influence of bilayer period and thickness ratio on the mechanical and tribological properties of CrSiN/TiAlN multilayer coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2011, 206, 1886–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kot, M.; Rakowski, W.A.; Major, Ł.; Major, R.; Morgiel, J. Effect of bilayer period on properties of Cr/CrN multilayer coatings produced by laser ablation. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2008, 202, 3501–3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, R.; Li, N. Research progress of (Ti, Al, Cr) N hard film system. Mater. Prot. 2021, 54, 131–136. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Song, G.H.; Luo, Z.; Li, F.; Chen, L.J.; He, C.L. Microstructure and indentation toughness of Cr/CrN multilayer coatings by arc ion plating. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2015, 25, 811–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Lin, S.S.; Tian, T.; Liu, M.X.; Chang, G.R.; Dong, D.; Shi, J.; Dai, M.J.; Jiang, B.L.; Zhou, K.S. Sand erosion and crack propagation mechanism of Cr/CrN/Cr/CrAlN multilayer coating. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 24638–24648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, L.; Wang, Y.X.; Li, J.L.; Li, H.; Lu, X.; Chen, J.-M. Structure and mechanical properties of thick Cr/Cr2N/CrN multilayer coating deposited by multi-arc ion plating. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2015, 25, 1135–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieciński, P.; Smolik, J.; Garbacz, H.; Kurzydłowski, K.J. Failure and deformation mechanisms during indentation in nanostructured Cr/CrN multilayer coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2014, 240, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falsafein, M.; Ashrafizadeh, F.; Kheirandish, A. Influence of thickness on adhesion of nanostructured multilayer CrN/CrAlN coatings to stainless steel substrate. Surf. Interfaces 2018, 13, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wu, B.; Lin, G.; Shao, Z.; Hou, M.; Yi, B. Arc ion plated Cr/CrN/Cr multilayers on 316L stainless steel as bipolar plates for polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 3249–3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Kim, K.H.; Xu, F.; Yang, X. Structure and oxidation behavior of compositionally gradient CrNx coatings prepared using arc ion plating. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2013, 228, S529–S533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Guo, Y.-Y.; Zhang, M.; Yang, Y.-J.; Huang, Z.; Zhou, Y.-W.; Wu, F.-Y.; Liang, Y.-S. Effect of Cr/CrNx transition layer on mechanical properties of CrN coatings deposited on plasma nitrided austenitic stainless steel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 367, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Cui, M.; Jiao, J.; Lian, Y.; Yang, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, Y.; Tian, X.; Gong, C. Surface feature of the substrate via key factor on adhesion of Cr/Cr2N multilayer and alloy substrate. Vacuum 2025, 233, 113991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Cui, M.; Lian, Y.; Jiao, J.; Yang, J.; Wu, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Tian, X.; Gong, C. The Cr/Cr2N multilayer coating with high load-bearing capacity and thermal shock resistance. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 41, 110927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Qiu, L.; Pan, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, S.; Dong, C. Nitrogen diffusion mechanism, microstructure and mechanical properties of thick Cr/CrN multilayer prepared by arc deposition system. Vacuum 2022, 199, 110902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonekura, D.; Fujita, J.; Miki, K. Fatigue and wear properties of Ti–6Al–4V alloy with Cr/CrN multilayer coating. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2015, 275, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beliardouh, N.E.; Bouzid, K.; Nouveau, C.; Tlili, B.; Walock, M.J. Tribological and electrochemical performances of Cr/CrN and Cr/CrN/CrAlN multilayer coatings deposited by RF magnetron sputtering. Tribol. Int. 2015, 82, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, F.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Zheng, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, S. Improved adhesion and erosion wear performance of CrSiN/Cr multi-layer coatings on Ti alloy by inserting ductile Cr layers. Tribol. Int. 2021, 153, 106657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.F.; Chang, Y.C.; Chang, S.H.; Ma, J.L.; Lin, H.C. Improving the corrosion and wear resistance of CoCrNiSi0.3 Medium-Entropy Alloy by magnetron sputtered (CrN/Cr)x multilayer films. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 478, 130407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.W.; Zhou, Q.; Liao, B.; Hua, Q.S.; Ou, Y.X.; Wang, H.Q.; Chen, S.N.; Yan, W.Q.; Huang, H.Z.; Zhao, G.Q.; et al. Structure, mechanical and tribological properties of thick CrNx coatings deposited by HiPIMS. Vacuum 2022, 203, 111253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, D.F.; Gómez, A.; Vélez, J.M.; Souza, R.M.; Olaya, J.J. A mechanical and tribological study of Cr/CrN multilayer coatings. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2015, 160, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Lin, S.S.; Lu, J.D.; Huang, S.Q.; Yin, Z.F.; Yang, H.Z.; Bian, P.Y.; Zhang, Y.L.; Dai, M.J.; Zhou, K.S. Research on high temperature wear resistance mechanism of CrN/CrAlN multilayer coatings. Tribol. Int. 2023, 180, 108184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zheng, L.; Li, W.; Liu, Z.; Li, L.; Wang, B.; Cai, Y.; Ren, X.; Liang, X. Effects of PVD CrAlN/(CrAlB)N/CrAlN coating on pin–disc friction properties of Ti2AlNb alloys compared to WC/Co carbide at evaluated temperatures. Metals 2024, 14, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, W.Y.; Hsu, C.H.; Chen, C.W.; Wang, D.Y. Characteristics of PVD-CrAlSiN films after post-coat heat treatments in nitrogen atmosphere. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2011, 257, 3770–3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.