Abstract

The irradiation of atomic oxygen (AO) severely restricts the application of polymeric lubricating coatings in low Earth orbit (LEO). Herein, octa- and mono-amino polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxanes (POSSs) were chemically bonded onto polyimide/molybdenum disulfide (PI/MoS2) composite coatings with a gradient structure based on Si density. The gradient coatings presented better wear resistance under different loads; notably, the wear rate decreased by 83.5%. Additionally, the effects of AO exposure on the surface morphologies, chemical structure, and tribological properties of the gradient coatings were investigated in detail. The results indicated that the mass loss and wear rates under AO irradiation decreased significantly, which can be attributed to the passivated network-like SiO2 layer that covered the coating surface after AO irradiation. As a result, the addition of POSS significantly improved the tribological properties and AO resistance.

1. Introduction

Generally, spacecraft face harsh conditions in the space environment, which consists of high-vacuum, ultraviolet (UV), atomic oxygen (AO), electron, and strong radiation during service in low Earth orbit (LEO), which has led to the failure of lubricating materials and has seriously affected the service life of these spacecraft [1,2,3]. In particular, the major component of AO, playing an important role in the atmosphere, can collide with space materials at high velocities of 8 km/s, with 5 eV of kinetic energy. In addition, AO has strong oxidizability and can cause considerable erosion, degradation, and oxidation of polymeric lubrication materials, resulting in the dramatic deterioration of their mechanical and tribological properties [4,5,6].

Polyimide (Kapton (PI), with excellent mechanical properties and space radiation resistance) [7,8,9] and molybdenum disulfide (MoS2, with excellent low-friction characteristics and wear resistance) [10,11,12] have become indispensable high-performance structural or coating materials in the aerospace industry due to their excellent inherent characteristics. Nevertheless, the increasing life-duration requirements and harsh service conditions of new spacecraft (such as those used in space stations and lunar exploration projects) demand a higher performance of lubricating materials. Traditional polymeric lubricating coatings can no longer meet the ever-increasing multifunctional demands for high AO resistance, excellent tribology properties, and long life.

A general approach to producing polymeric materials with great AO resistance is copolymerization or coating with an inorganic protective layer to yield a hybrid composite material that can resist AO erosion [13,14,15,16]. In previous research, many surface-protective AO-resistant inorganic coatings were deposited on polymeric surfaces via methods such as surface silanization, ion implantation, and vapor deposition [17,18,19,20]. However, inorganic surface coatings are prone to cracking or peeling during transport and can easily develop small cracks when subjected to thermal cycling or repeated shear stress during service, leading to ‘drilling’ of the underlying polymer. In an effort to address this, internal matrix strengthening has received more attention; this strengthening is achieved by adding inorganic nanoparticles or organic compounds containing Si and P elements to a polymeric system to improve its surface protection properties [21,22,23]. Moreover, by introducing organic–inorganic hybrid materials to construct a gradient composite structure, the interfacial bonding between inorganic and organic components can be significantly enhanced, and the coating can be endowed with excellent surface-protective performance. The introduction of organic–inorganic hybrid silicon nanomaterials has especially led to excellent AO resistance and structural advantage.

Polyhedral oligomeric sesquisiloxane (POSS) has attracted widespread attention, as it has been found to act as a novel organic/inorganic hybrid nanomaterial, containing a hollow, cage-like inorganic backbone that consists of Si-O-Si bonds surrounded with different inert or functional groups [24,25,26,27]. Additionally, the POSS monomer can be chemically bonded in polymeric materials as a cross-linking agent, side group, or end-capping agent, and is enriched on the inside or surface of the polymeric system [6,28]. Many scholars have made extensive efforts to develop POSS-reinforced polymeric materials, demonstrating that the introduction of moderate POSS could improve their mechanical properties and significantly increase AO resistance [14,24,29]. Similarly, in our previous work, we systematically studied the effect of POSS on the tribological properties of lubricating coatings, and the results indicated that adding multifunctional POSS improved the cross-linking, hardness, strength, and wear resistance of the coatings [2,30]. However, the coating surface faced erosion and oxidation under AO irradiation caused by insufficient silicon on the coating surface. Therefore, it is of great significance to enhance the protective capability of coating surfaces through the construction of a gradient structure.

In this work, the octa- and mono-amino POSSs were grafted onto a PI matrix according to the molecular structure of the POSS. Then, POSS-modified PI/MoS2 composite coatings with a double-deck structure were prepared, and the effects of applied load on the friction and wear behaviors were investigated. On this basis, the effects of AO on the surface morphologies, chemical structure, elementary composition, and tribological properties were also investigated. The results suggested that the POSS-modified composite coatings with a double-deck structure exhibited excellent AO resistance and tribological properties in the LEO. Therefore, hopefully, research into the evolution mechanisms of the POSS-modified gradient structure and its tribological properties under AO irradiation could constitute an efficient direction for fabricating advanced lubricating coatings with excellent AO resistance and tribological properties in LEO.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The octa-amino and mono-amino seven-isobutyl polyhedral oligomeric sesquisiloxane (POSS) materials were purchased from the Beijing HWRK Chemical Company (Beijing, China). The pyromellitic dianhydride (PMDA) materials were obtained from the Sinopharm Group Chemical Reagent Company, whereas the 4,4-diaminodiphenyl ether (ODA) was sourced from Shanghai Kefeng Chemical Reagent Company (Shanghai, China). The MoS2 powder, with an average particle size of 2.5 μm after planetary ball milling, was supplied by Shanghai Research Institute of Synthetic Resins (Shanghai, China). Other reagents, including ethanol, hydrochloric acid, and N, N-dimethylacetamide (DMAc), were commercially provided by East Instrument Chemical Glass Company Limited (Shanghai, China). All chemicals were of analytical grade.

2.2. Preparation of POSS/PI/MoS2 Coatings

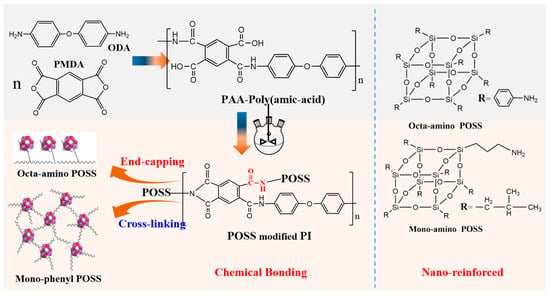

First, 1.5 g of ODA was dissolved in 30 mL of DMAc under stirring for 30 min. After the ODA was fully dissolved, the reaction setup was transferred to an ice-water bath in a three-necked flask, and 1.65 g of PMDA was added slowly within 5 min. As the reaction proceeded, the viscosity of the solution gradually increased, and its appearance changed from transparent to pale yellow. This mixture was stirred continuously for 6 h, ultimately yielding a poly(amic acid) (PAA) solution. Then, the octa-amino POSSs (5 wt% of the system) were added into the solution, and stirring was continued 10 min. And the mono-amino POSSs (5 wt% of the system) were added and stirred for another 20 min to ensure thorough reaction. POSS nanomaterials can be incorporated into the main chain of the polyimide (PI) resin or as a side or end-group, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Preparation procedure of the composite coatings.

The octa- and mono-amino POSS-PI composites and MoS2 were mechanically mixed with a certain proportion, as shown in Table 1. The lubricating coatings were fabricated by sequentially spraying the composite slurries onto steel substrates. First, a layer of octa-amino POSS-PI/MoS2 slurry was sprayed onto a steel substrate with a thickness of approximately 25 ± 3 μm, followed by a layer of octa- and mono-amino POSS-PI/MoS2 at about 10 ± 2 μm. The as-sprayed gradient coatings were then pre-dried at 150 °C for 1 h in an electric oven and subsequently cured at 280 °C for 1 h, resulting in a final coating thickness of 35 ± 3 μm.

Table 1.

Weight compositions of the POSS-PI/MoS2 composite coatings.

2.3. AO Exposure Experiment

The AO exposure experiments were performed using a space environment ground simulation device (purchased from Yanfei Electrical Technology Company Limited, Hefei, China) under vacuum (<1.5 × 10−2 Pa). In these experiments, AO with an average kinetic energy of approximately 5 eV struck the lubricating coatings, and the AO flux was approximately 1.23 × 1016 AO/cm2·s. The AO erosion experiment was conducted from 5 h to 20 h.

The effective AO flux can be calculated by Equation (1).

where ρ is the density of Kapton, A is the exposed surface area, t is the exposure time, and AORC is the AO reactivity coefficient of Kapton with an AO reactivity of 3.0 × 10−24 cm3/atom. Additionally, ΔM is the mass loss of Kapton after AO irradiation [2,24].

2.4. Structural Characterizations of the Coatings

The microhardness of these composite lubricating coatings was investigated using a microhardness tester (HXS-1000, Caikon, Shanghai, China) under an applied load of 10 g and a loading time of 5 s. To evaluate the interfacial bonding strength, adhesion tests were performed at least in triplicate on each specimen using a QFZ-II tester according to the standard cross-hatch method (GB/T 4893.4-85 [31]).

To analyze the chemical structure evolution induced by AO irradiation, the coatings were examined using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR-ATR, Nexus 870, Thermo Nicolet Corporation, Madison, WI, USA), X-ray diffraction (XRD, Bruker D8 Discover 25, Karlsruhe, Germany), and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, ESCA-LAB 250Xi, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Portland, OR, USA). To investigate the morphological and compositional changes on the surface and within wear tracks, scanning electron microscopy (SEM, JSM-5600LV, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) coupled with energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) was employed. Furthermore, micro-Raman spectroscopy (HORIBA Jobin LabRAM HR Evolution, Paris, France) was utilized to probe the chemical structures of the worn surfaces across the 100–1100 cm−1 spectral range.

2.5. Friction and Wear Behavior

The tribological properties of the POSS-PI/MoS2 composite coatings, both before and after AO irradiation, were comparatively evaluated using a ball-on-disk vacuum tribo-meter (CSM, Anton Paar, Graz, Austria) at room temperature. The vacuum degree was less than 5 × 10−5 mbar, and a GCr15 steel ball (diameter: 6 mm; hardness: 58–62 HRC) served as the counterpart. Prior to AO irradiation, the counter balls slid against the coatings at a speed of 10 cm/s (amplitude: 2.5 mm) with the applied load ranging from 5 N to 20 N, and the friction distance was 100 m. After AO erosion, the friction tests were conducted under 5 N at a speed of 10 cm/s (amplitude: 2.5 mm), with 100 m distance. In addition, the lifetime was tested under 5 N at a speed of 1000 rpm, with a distance 6.5 × 105 r. The wear volume of each track was measured using a Micro-XAM-3D non-contact surface profiler (AEP, R-tec instruments, San Jose, CA, USA) to calculate the wear rate, thereby evaluating the anti-wear performance. A specific wear rate (W) was calculated according to the following formula:

where V, F, and D represent the wear volume (mm3), normal load (N), and wear distance (m), respectively. All experiments were repeated three times to ensure reproducibility.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Tribological Properties of the Lubricating Coatings Under Different Loads

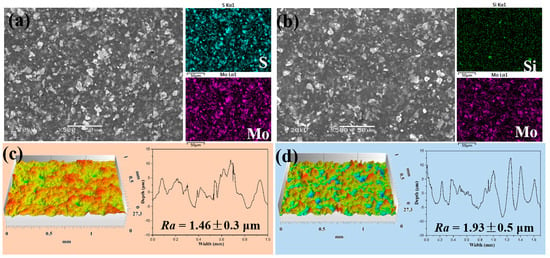

Figure 2 shows the SEM morphology and element mapping of the composite coatings. As can be observed from the figure, the surfaces of both PI/MoS2 and POSS-PI/MoS2 composite coatings exhibited a relatively uniform surface (Figure 2a,b). The surface roughness of the PI/MoS2 coating was relatively low; however, the POSS-modified composite coating exhibited greater roughness compared to the original PI/MoS2 coating. The low surface energy of POSS resulted in a surface migration effect, and the mono-amino POSS acted as the side or end group, leading to an increase in surface roughness [27]. This observation is supported by the three-dimensional morphology and the surface roughness measured from the two-dimensional cross-sectional profiles (Figure 2c,d), and our previous work could confirm the formation of a gradient structure based on Si density [24]. Additionally, the distribution of Mo and Si elements indicated that molybdenum disulfide and POSS were uniformly dispersed within the coating.

Figure 2.

SEM micrographs (a,b), three-dimensional and sectional profiles (c,d) of the (a,c) PI/MoS2, and (b,d) POSS-PI/MoS2 lubricating coating surfaces.

Additionally, the basic physical properties of the composite coatings before and after POSS modification were measured and are listed in Table 2. As can be seen, both the original PI/MoS2 and the POSS-modified lubricating coatings demonstrate an adhesion grade of 0, a flexibility grade of 1 mm, and an impact resistance of 50 cm, indicating that the prepared coatings possessed excellent fundamental properties and met national standards. Furthermore, the microhardness of the POSS-modified coating was improved. This improved hardness can be attributed to the incorporation of the inorganic, cage-like siloxane framework from POSS and the increased cross-linking density caused from multiple amino groups and the PI matrix [23,32]. Additionally, the mono-amino POSSs were introduced as an end-capping agent that is mainly distributed on the composite surface due to surface migration, which resulted in the gradient structure. Therefore, the synergistic effect of octa- and mono-amino POSS collectively enhanced the coating’s load-bearing capacity and hardness.

Table 2.

Basic physical properties of the composite coatings.

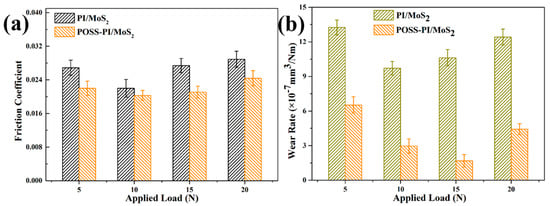

The influence of different loads on the vacuum tribological performance of the POSS-modified coating was investigated, as shown in Figure 3. It is possible to observe that both the original and POSS-modified coatings maintained relatively good lubricating properties, with friction coefficients below 0.03. However, compared to the PI/MoS2 coating, the modified coating exhibited a decrease in friction coefficient (Figure 3a), although this reduction is not significant. However, the coatings exhibited significant differences in wear rates, with the modified coatings showing a remarkable reduction in wear. The wear rate of the PI/MoS2 composite coating exceeded 9 × 10−7 mm3·N−1·m−1 under both low (5 N) and high (20 N) loads. By contrast, the POSS-modified coating demonstrated a notably lower wear rate, which further decreases as the load increased. At a load of 15 N, the POSS-modified coating exhibits optimal wear resistance, with a wear rate as low as 2.7 × 10−7 mm3·N−1·m−1, which decreased by 83.5% compared with that of the original coating. This improvement is attributed to the incorporation of the abundant inorganic siloxane cage-like frameworks in the POSS, which enhanced the coating’s hardness and load-bearing capacity. Additionally, multiple amino groups in POSS underwent cross-linking reactions with the resin, which increased the cross-linking density and thereby further improved the wear resistance of the composite coating.

Figure 3.

Average friction coefficient (a) and wear rates (b) of the composite coatings under different applied loads.

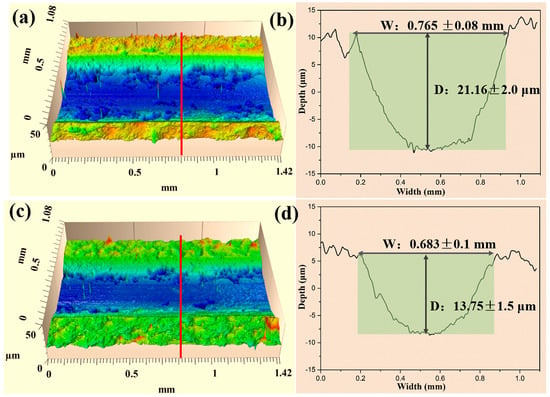

The three-dimensional (3D) topographies and cross-sectional (2D) curves of the wear tracks were also measured to further explore their wear mechanisms, and the results of these measurements are shown in Figure 4. It can be seen that the PI/MoS2 coating experienced severe wear, with a relatively wide and deep wear scar profile measuring approximately 0.765 ± 0.08 mm in width and 21.16 ± 2 μm in depth (Figure 4a). By contrast, the POSS-modified PI/MoS2 coating exhibited significantly reduced wear track dimensions (Figure 4b), with a width and depth measuring 0.68 ± 0.1 mm and 13.75 ± 1.5 μm, respectively. Furthermore, the surface roughness of the worn area decreased markedly, which is likely attributable to a change in the wear mechanism. Thus, the incorporation of inorganic cage-like frameworks and high cross-linking density caused by multiple functional groups into the coating imparted excellent load-bearing capacity, thereby enhancing wear resistance as confirmed by the results above.

Figure 4.

Three-dimensional surface morphologies (a,c) and sectional profiles (b,d) of the wear tracks of (a,b) PI/MoS2 and (c,d) POSS-PI/MoS2 coatings under 10 N.

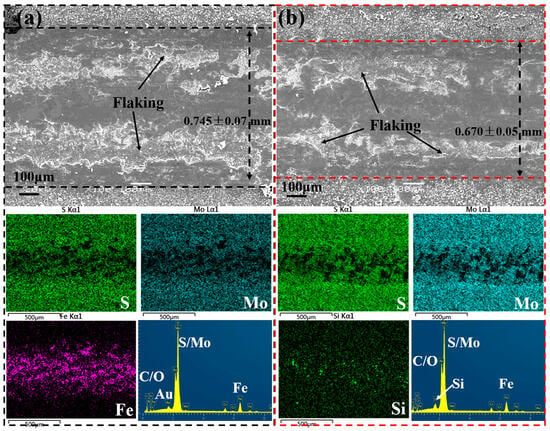

The SEM morphologies and corresponding elemental mapping distributions of S, Mo, and Si on the worn surfaces are presented in Figure 5. As shown in Figure 5a, the worn surface of the PI/MoS2 coating exhibits severe flaking, with Fe from the substrate exposed. This indicates that the coating experienced severe wear during the friction process. In addition, slight peeling appears on the worn surface, which results from the fatigue wear. However, the addition of POSS exhibits an obvious effect on the wear mechanism of the composite coating. The spalling phenomena in the wear scar morphology are significantly reduced (Figure 5b), and some scratch grooves appear on the worn surface, which can be attributed to the abrasive wear. Apart from this, the Si and Mo elements of the POSS-modified coating are uniformly distributed on the wear scar surface. This result further confirms that POSS was uniformly dispersed within the composite coating.

Figure 5.

SEM micrographs and EDS mapping of the wear tracks of (a) PI/MoS2 and (b) POSS-PI/MoS2 coatings under 10 N.

3.2. Evolution of Morphology and Microstructure Under AO Irradiation

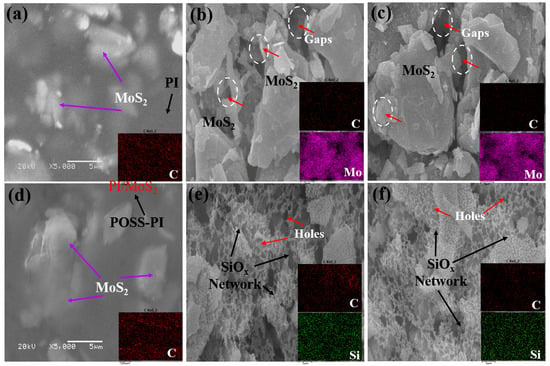

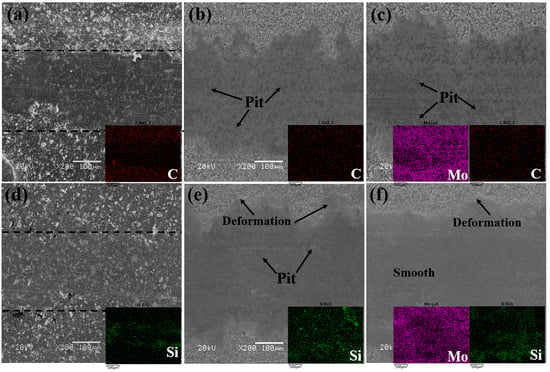

The SEM micrographs of the PI/MoS2 and POSS-PI/MoS2 composite coatings before and after different AO exposure times are shown in Figure 6. The composite coating surfaces were relatively smooth and continuous prior to atomic oxygen (AO) irradiation (Figure 6a,d), with some MoS2 sheets distributed both within and on the surface of the PI matrix. However, the coating surfaces became significantly roughened and developed numerous pores after AO irradiation (Figure 6e,f). Compared to the unexposed samples, all exposed coatings exhibited uneven and bumpy morphologies. This change can be attributed to severe erosion and oxidative degradation of the coating surfaces caused by AO irradiation. On the surface of the pristine PI/MoS2 coating, molybdenum disulfide is stacked. It is noteworthy that the POSS-PI/MoS2 composite coating developed a distinct, network-like cross-linked structure on its surface after AO exposure (Figure 6e,f). The PI resin exposed on the coating surface underwent significant oxidation and degradation upon AO exposure, which led to the surface becoming covered with Si, O, S, and Mo elements. The network-like structure observed on the modified coating surface can be attributed to the formation of SiO2 and SiOx residues originating from the oxidation of POSS molecules. For the specific conditions of our AO exposure experiment, this protective layer is estimated to be on the order of 100 nm [33]. Notably, due to the presence of the protective layer, the gaps between molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) sheets (Figure 6b,c) have become significantly smaller and fewer. Additionally, the POSS-modified coatings exhibited a regular network structure, and the holes in the network (Figure 6e,f) feature sizes from 200 to 400 nm [34]. Although only partially continuous, this network-like residue can protect the underlying organic material from further AO irradiation. These morphological observations align with the measured changes in coating thickness and mass loss. Consequently, the POSS-PI/MoS2 composite coating demonstrated strong AO resistance, which can be ascribed to the formation of a protective SiOx network layer on its surface [2,4,35].

Figure 6.

SEM micrographs and EDS mapping of the coating surfaces of (a–c) PI/MoS2 and (d–f) POSS-PI/MoS2 after AO irradiation: (a,d) 0 h; (b,e) 10 h; (c,f) 20 h.

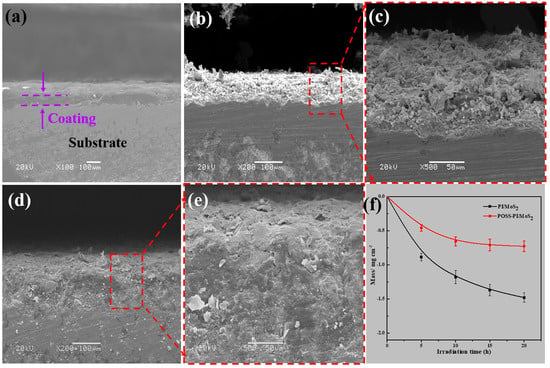

The cross-sectional SEM morphologies of the original and POSS-modified composite coatings before and after atomic oxygen (AO) exposure are shown in Figure 7. As can be observed from the figure (Figure 7a), the coating structure before AO irradiation was relatively continuous and smooth. However, after AO irradiation, the thickness of the original PI/MoS2 coating decreased significantly and exhibited flocculent accumulation (Figure 7b,c). By contrast, the POSS-modified coating retains a relatively intact structure and a smooth cross-section after AO irradiation (Figure 7d,e).

Figure 7.

Cross-sectional SEM images of the (b,c) PI/MoS2 and (d,e) POSS-PI/MoS2 lubricating coatings before (a) and after (b–e) AO irradiation for 20 h; (f) average mass loss of the composite coatings varies from the irradiation time.

Figure 7f presents relationship curves between mass loss per unit surface area and atomic oxygen (AO) irradiation time. In the initial irradiation stage (within 5 h), the mass loss of all coatings increases rapidly due to the degradation and breakdown of the surface PI resin. Notably, the mass loss of the POSS-modified coating during this period was only 50% of that of the unmodified one. When AO irradiation exceeded 10 h, the incorporation of POSS further altered the mass loss trend in the PI-based coatings, leading to a significant reduction in mass loss. Specifically, at the same irradiation duration, the POSS-modified coating exhibited substantially lower mass loss compared to the unmodified coating. These results indicate that mass loss primarily occurred during the early stages of AO exposure, which is mainly attributed to the oxidation and degradation of surface PI resin and the organic functional groups in POSS. As irradiation continued, the mass loss rate of the composite coating gradually slowed, which can be attributed to the protective surface layer formed by MoS2 and SiOx.

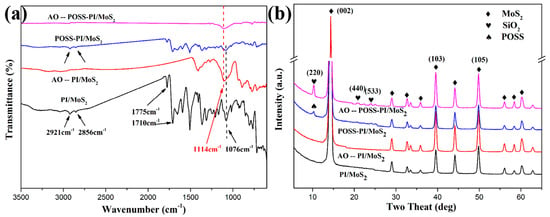

The FTIR-ATR spectra of the PI/MoS2 and POSS-modified composite coatings before and after atomic oxygen (AO) exposure are shown in Figure 8a. As can be observed, the irradiation of AO exposure led to significant changes in the characteristic absorption peak intensity on the coating surfaces. After AO irradiation, the absorption peaks at 1525 cm−1 (C=C) and 1710 cm−1 (C=O) and in the coatings were significantly weakened, and the intensity of the absorption peaks at 1076 cm−1 (C–O–C) and 2921 cm−1 (–NH) also decreased. The decrease in these peak intensities indicates that most of the PI resin exposed on the coating surface was subsequently oxidized and degraded. As a result, these FTIR-ATR results indicate that complex chemical reactions and degradation of the PI resin and the other organic components occurred in the PI/MoS2 coatings after AO irradiation [2,5]. Nonetheless, the surface infrared peak intensities of the POSS-modified coating also decreased significantly, confirming that severe oxidative degradation of the organic surface components still took place.

Figure 8.

FTIR-ATR (a) and XRD (b) spectra of the composite coatings before and after 20 h of AO irradiation.

Additionally, the surface XRD spectra of the composite coatings, both before and after AO irradiation, are shown in Figure 8b. Compared to the pristine coating, the POSS-modified coating exhibited distinct silica peaks after AO irradiation, indicating that the POSS in the modified coating was oxidized, forming silica on the surface. This phenomenon confirms that the network structure observed on the coating surface in Figure 6 consists of silica residues.

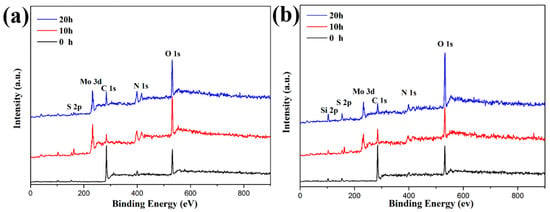

To investigate the changes in the surface element chemical composition of the PI-based composite coatings before and after AO irradiation, XPS spectra were further employed, and the results are presented in Figure 9. It is possible to observe that the PI/MoS2 coating displays XPS peaks for S2p, Mo3d, C1s, N1s, and O1s, whereas the POSS-modified coating exhibits an additional Si2p peak. In addition, it is worth noting that the element composition on the coating surface changed significantly, particularly with a notable decrease in C 1s element content. The changes in the element contents were mainly caused by the oxidative degradation of the PI resin on the surface, which led to the reduction in carbon content. However, the intensity of the sulfur (S) and molybdenum (Mo) elements on the coating surface increased significantly, due to the exposure of molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) from within the coating to the surface. Additionally, the intensities of the Si2p and O1s peaks in the POSS-modified coating tended to increase after AO exposure (Figure 9b). The surface element composition of the PI-based and POSS-modified coatings before and after AO exposure derived from the XPS spectra are listed in Table 3.

Figure 9.

XPS spectra of the composite coatings (a) PI/MoS2 and (b) POSS-PI/MoS2 before and after AO irradiation.

Table 3.

Surface composition (at. %) of the composite coatings before and after AO exposure: (a) PI/MoS2 and (b) POSS-PI/MoS2.

It was found that the atomic oxygen (AO) could react with the PI resin and other organic components exposed on the coating surface, thus producing some volatile gases and escaping afterward. The results in Table 3 indicate that after AO irradiation, the carbon content on the coating surface significantly decreased with prolonged irradiation time, which decreased from 72.34% and 64.97% to 28.05% and 21.91%, respectively. Furthermore, due to the formation of non-volatile silica and other oxides during AO exposure, the contents of silicon and oxygen elements in the composite coatings increased markedly after AO irradiation [36]. For the POSS-PI/MoS2 coatings, the O1s and Si2p contents increased from 21.56% and 5.5% to 39.83% and 16.2%, respectively. These results are in accordance with the surface and cross-sectional morphologies of the coating, as shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7.

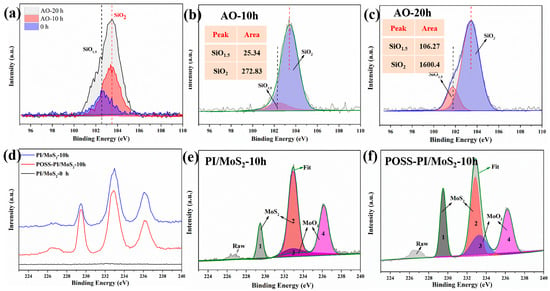

Figure 10 shows high-resolution Si 2p and Mo 3d XPS spectra of the composite coating before and after AO irradiation, along with the corresponding Gaussian fitting results. As shown in Figure 10a, the intensity of the Si peak in the XPS spectra increased with the extended irradiation time. In addition, compared to the unirradiated coating, the Si 2p peak of the coating after AO exposure shifted toward a higher binding energy (Figure 10b,c), which indicated the oxidation of Si8O12 to SiO2 after AO exposure [4,24]. Furthermore, the Mo 3d XPS peaks of the PI/MoS2 composite coating correspond to MoS2 before exposure and transformed to MoO3 after AO irradiation (Figure 10d–f), confirming the oxidation of MoS2 under AO irradiation [37,38,39].

Figure 10.

High-resolution Si 2p (a–c) and Mo 3d (d–f) XPS spectra of the coatings after AO irradiation.

Additionally, after AO irradiation, the ratio of SiO1.5 to SiO2 in the POSS-PI/MoS2 composite coating after 10 h of AO exposure was about 1:10.8, whereas it was 1:15.1 after 20 h of AO irradiation. The significantly increased proportion of silica on the coating surface further demonstrated the formation of surface silicon oxide. At the same time, the molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) on the surface also oxidized to molybdenum oxide, with the valence state of molybdenum changing accordingly, and the content of molybdenum oxide increased with prolonged irradiation time.

As a result, the organic components on the coating surface were preferentially attacked by AO at the beginning of the exposure test, producing volatile gases such as CO and CO2 that escaped from the surface. With the extended AO irradiation time, the exposed MoS2 and POSS on the coating surface were oxidized and formed MoO3 and SiO2, which created an oxidized passivation layer that could protect the underlying organic material from further erosion and degradation.

3.3. Tribological Properties of the Composite Coatings Under AO Irradiation

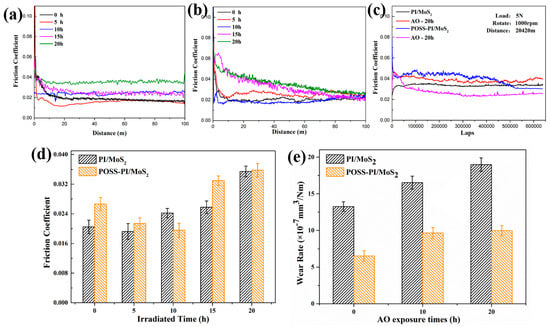

According to the results above, atomic oxygen (AO) exposure led to severe oxidative degradation of the organic materials and molybdenum disulfide (MoS2), thereby affecting the tribological properties of the composite coatings. The influence of AO irradiation on the friction and wear behaviors of POSS-modified composite coatings before and after AO exposure is shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Friction coefficient curves (a–c), average CoF (d), and wear rates (e) of the composite coatings (a) PI/MoS2 and (b) POSS-PI/MoS2 before and after AO irradiation; (c) the standard lifetime in the space environment.

The friction coefficient (CoF) curves of the original and POSS-modified coatings under different exposure times are presented in Figure 11a,b. It can be seen that the friction coefficient decreases in the initial stage during the friction process, which was caused by the rapid formation of a transfer film composed of MoS2 on the counterpart ball. Additionally, most of the CoFs after AO irradiation were slightly higher than those before irradiation, as shown in Figure 11c, which can be attributed to the oxidative degradation of the lubricant exposed on the surface, as shown in Figure 6, as well as the formation of a hard oxide layer consisting of SiO2 and MoO3.

The wear rates after AO exposure were calculated and are shown in Figure 11e. It can be seen that after AO exposure, the wear rates of the original PI/MoS2 coatings increased with the prolonged exposure times compared with those before AO irradiation. The result was caused by the loosened and stacked molybdenum disulfide on the coating surface after AO exposure. However, it is worth noting that the POSS-modified coating after AO erosion presented a slightly higher wear rate than that before AO, which can be attributed to the AO-induced passivating layer on the coating surface. The hard SiO2 protective layer provided a high load-bearing capacity, and prevented the inner polymeric materials from further erosion caused by AO exposure, thereby improving the wear resistance under AO irradiation.

Meanwhile, rotational friction experiments were also performed and the CoFs of the original and modified PI/MoS2 coatings are shown in Figure 11d, both before and after AO exposure. All the composite coatings exhibit excellent wear resistance during the friction process within 6 × 105 laps. It is worth noting that the POSS-modified coating after 20 h of AO exposure presents a lower friction coefficient compared to the coating before irradiation, which confirmed the protecting and strengthening effect under AO irradiation.

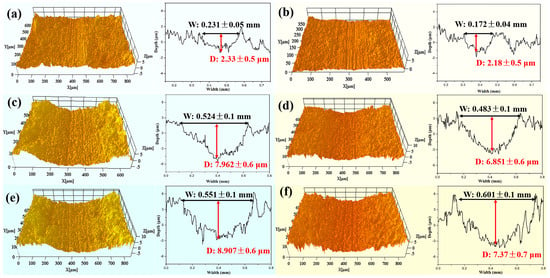

The three-dimensional (3D) topographies and 2D cross-sectional profiles of the wear tracks under different irradiation times were further investigated to explore the wear mechanisms, as shown in Figure 12. Before AO irradiation, the wear tracks of both the original and POSS-modified coatings were relatively narrow and shallow (Figure 12a,b), with a depth of only 2.28 μm and 2.33 μm. However, both the depth and width of the wear tracks increased significantly after AO irradiation. This result is primarily attributed to the oxidative decomposition of the PI resin, which acted as the supporting phase in the coating. Secondly, the accumulation of MoS2 on the surface resulted in a softer and less cohesive coating surface that notably exacerbated the wear track. In addition, the POSS-modified coating exhibited a relatively lower wear track depth and width compared to the original PI/MoS2 coating. This improvement can be attributed to the introduction of POSS, which enhanced the cross-linking density and the AO resistance caused by the protective layer consisting of SiO2. Additionally, the amount of the Si-O-Si inorganic framework in the POSS afforded the coating an excellent load-carrying capacity, which led to increases in wear resistance, and this result corresponds to the 3D topographies above.

Figure 12.

Three-dimensional surface morphologies and cross-sectional profiles of the composite coatings (a,c,e) PI/MoS2 and (b,d,f) POSS-PI/MoS2 before (a,b) and after 10 h (c,d), and 20 h (e,f) of AO irradiation.

The SEM morphologies and EDS elemental distribution mapping of the worn surfaces before and after AO irradiation were investigated, and the results are shown in Figure 13. It can be seen that the composite coatings exhibited relatively narrow wear tracks before AO irradiation, which is consistent with the 3D topographies shown in Figure 12. In particular, compared to the PI/MoS2 coating, the POSS-PI/MoS2 coating exhibits smaller and slighter wear tracks with minor surface pits, which is consistent with the aforementioned wear morphology data. Moreover, after AO irradiation, the oxidation of surface MoS2 generated hard MoO3 particles, leading to some pitting and slight abrasive grooves on the worn surface (Figure 13e,f).

Figure 13.

SEM micrographs and EDS spectra of the worn surfaces (a–c) PI/MoS2 and (d–f) POSS-PI/MoS2 before (a,d) and after 10 h (b,e) and 20 h (c,f) of AO irradiation.

Furthermore, the elemental distributions of the worn surface were further explored through EDS analysis, as shown in the figure. Both before and after AO irradiation, the Mo element remained uniformly dispersed on the coating surface and within the worn track, although its content within the wear track itself was relatively lower than that on the coating surface. This result was caused by the transfer of MoS2 during the friction process, which promoted the formation of a lubricating film on the counterpart balls, thereby leading to the decrease in Mo element on the worn surface. In addition, after AO irradiation, the C content on the worn surface decreased significantly, whereas the Si content increased markedly. These changes can be attributed to the oxidation and degradation of the PI matrix, along with the surface oxidation of POSS to form a passivation layer, which have been confirmed by the results above. As a result, the incorporation of POSS enhanced both the tribological performance and AO resistance of the PI-based composite coatings. This incorporation also altered the wear mechanism, as the coating exhibited plastic deformation and fatigue wear prior to AO irradiation, whereas under AO erosion, it transitioned to mild abrasive wear.

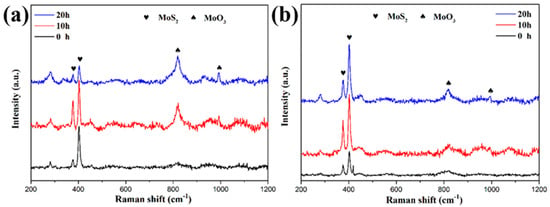

Figure 14 shows the Raman spectra of both original and POSS-modified PI/MoS2 composite coatings before and after AO exposure. For the PI/MoS2 coating prior to irradiation, two strong bands are observed at 385 cm−1 and 408 cm−1 (Figure 14a), corresponding to the characteristic peaks of MoS2 [2]. However, the intensity of these MoS2 signals markedly decreased after AO exposure, and two new weak peaks ascribed to MoO3 emerge at 818 and 995 cm−1. Moreover, the intensity of the MoO3 peaks increases with prolonged irradiation time, indicating the partial oxidation of MoS2.

Figure 14.

Raman spectra of the worn surfaces of the (a) PI/MoS2 and (b) POSS-PI/MoS2 composite coatings before and after AO irradiation.

In contrast, the POSS-modified coating shows little change in the MoS2 peak intensity after AO irradiation (Figure 14b). This indicates that the incorporation of POSS effectively suppressed the oxidation of MoS2, which can be attributed to the protective SiO2 protective layer formed on the coating surface confirmed by the XPS spectra.

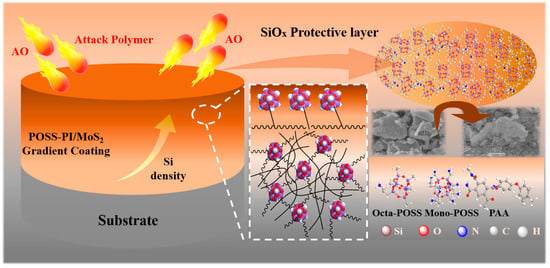

The structural evolution schematic of the original and POSS-modified coatings before and after AO exposure are shown in Figure 15. It can be seen that the incorporation of POSS enhances the cross-linking and hardness of the PI/MoS2 composite coatings before AO irradiation and jointly improves their wear resistance. After AO exposure, the POSS-containing coatings were oxidized and a SiO2 passivating layer was formed on the surface, which protected the underlying PI and MoS2 from further oxidation and degradation. Compared with the original coating, the content of Si on the surface is relatively high, which results from the surface migration and enrichment of OMPOSS on the coating surface. Thus, only MoS2 on the most superficial surface was oxidized, which corresponds to the results of Raman and XPS.

Figure 15.

Schematic diagram of the structural evolution of the OMPOSS-modified PI/MoS2 composite coatings under AO irradiation.

4. Conclusions

In this work, the mono- and octa-amino POSSs were introduced into PI/MoS2 coatings via chemical grafting, fabricating a gradient composite structure with varying silicon content. The effect of POSS on the wear resistance of PI/MoS2 coatings before and after AO exposure was systematically investigated. The results indicated that the incorporation of multifunctional POSS provided an inorganic framework composed of Si-O-Si bonds and enhanced the cross-linking density of the PI-based composite coating, thereby enhancing both the load-bearing capacity and tribological properties of the coating. Furthermore, for the POSS-PI/MoS2 coating, the network-like SiO2 layer formed on its surface after AO irradiation compared with the PI/MoS2 coating. This passivated SiO2 layer protected the underlying organic material from further erosion and degradation, while also significantly suppressing the oxidation of the MoS2 lubricant, as confirmed by the XPS and Raman spectra. Therefore, it is possible to conclude that the addition of multifunctional POSS endows the PI-based modified coatings with excellent AO resistance and superior tribological properties under AO irradiation. The excellent AO resistance of POSS-PI/MoS2 coatings and their presumed mechanical and tribological properties would make them ideal as a protective coating in space environments.

Author Contributions

C.Y.: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing—Review and Editing, Supervision. P.Z.: Formal Analysis. M.W.: Methodology, Writing—Original Draft Preparation. Q.W.: Resources, Funding Acquisition. W.Z.: Formal Analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation, grant number 2022A1515110306.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, Y.; Yuan, H.; Yan, W.; Chen, S.; Qiu, M.; Liao, B. Atomic-Oxygen-Durable and Antistatic α-AlxTiyO/γ-NiCr Coating on Kapton for Aerospace Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 58179–58192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Ju, P.; Wan, H.; Chen, L.; Li, H.; Zhou, H.; Chen, J. POSS-Grafted PAI/MoS2 Coatings for Simultaneously Improved Tribological Properties and Atomic Oxygen Resistance. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 17027–17037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Ma, J.; Li, P.; Fan, L.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, C.; Jiang, L. Flexible Hard Coatings with Self-Evolution Behavior in a Low Earth Orbit Environment. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 46003–46014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Leng, X.; Bai, B.; Zhao, R.; Cai, Z.; He, J.; Li, J.; Chen, H. Effect of Coating Thickness on the Atomic Oxygen Resistance of Siloxane Coatings Synthesized by Plasma Polymerization Deposition Technique. Coatings 2023, 13, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Ju, P.; Wan, H.; Chen, L.; Li, H.; Zhou, H.; Chen, J. Enhanced atomic oxygen resistance and tribological properties of PAI/PTFE composites reinforced by POSS. Prog. Org. Coat. 2020, 139, 105427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minton, T.K.; Schwartzentruber, T.E.; Xu, C. On the Utility of Coated POSS-Polyimides for Vehicles in Very Low Earth Orbit (VLEO). ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 51673–51684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Dai, X.; Wu, Y.; Ba, X. Emerging Photo-Initiating Systems in Coatings from Molecular Engineering Perspectives. Coatings 2025, 15, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Li, S.; Fan, H.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, Y.; Luo, J.; Yang, L. One-Step Fabrication of Composite Hydrophobic Electrically Heated Graphene Surface. Coatings 2023, 14, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Zhang, B.; Wang, J.; Cao, C.; Yan, F. MWCNT–Polyimide Fiber-Reinforced Composite for High-Temperature Tribological Applications. Coatings 2024, 14, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Li, Q.Y.; Kalb, W.; Liu, X.Z.; Berger, H.; Carpick, R.W.; Hone, J. Frictional Characteristics of Atomically Thin Sheets. Science 2010, 328, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellore, A.; Romero Garcia, S.; Walters, N.; Johnson, D.A.; Kennett, A.; Heverly, M.; Martini, A. Ni-Doped MoS2 Dry Film Lubricant Life. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 7, 2001109. [Google Scholar]

- Vellore, A.; Garcia, S.R.; Johnson, D.A.; Martini, A. Ambient and Nitrogen Environment Friction Data for Various Materials & Surface Treatments for Space Applications. Tribol. Lett. 2021, 69, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Ma, G.; Han, C.; Li, G.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Q. Tribological properties and bearing application of Mo-based films in space environment. Vacuum 2021, 188, 110217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, A.; Jorge, P.D.; Xu, C.; Gouzman, I.; Minton, T.K. Atomic-Oxygen Effects on a Siloxane-Polyimide Block-Chain Copolymer. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2025, 7, 13125–13138. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, M.; Gu, H.; Tang, D.; Zeng, B.; Sun, R.; Sun, Y.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Song, L. Graphene-wrapped Mg-Al layered double hydroxides nanosheet coating with simultaneous atomic oxygen protection and electrostatic discharge resistance on polyimide. Compos. Part A 2025, 190, 108707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Q.; Wang, W.; Fu, Q.; Dong, D. Atomic Oxygen Irradiation Resistance of Transparent Conductive Oxide Thin Films. Thin Solid Films 2017, 623, 31−39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Qian, Y.; Xu, J.; Zuo, J.; Li, M. An AZ31 Magnesium Alloy Coating for Protecting Polyimide from Erosion-Corrosion by Atomic Oxygen. Corros. Sci. 2018, 138, 170−177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, M.; Li, H.; Ma, J.; Song, L. Property of Protection against Simultaneous Action between Atomic Oxygen Erosion and Ultraviolet Irradiation by MIL-53(Al) Coating. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 47324–47331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, C.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Tong, H.; Ye, X.; Wang, K.; Yuan, X.; Liu, C.; Li, H. Growth and atomic oxygen erosion resistance of Al2O3-doped TiO2 thin film formed on polyimide by atomic layer deposition. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 34833–34842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.M. Atomic Layer Deposition: An Overview. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 111−131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R.; Upadhyaya, H.P.; Minton, T.K.; Berman, M.R.; Du, X.; George, S.M. Protection of polymer from atomic-oxygen erosion using Al2O3 atomic layer deposition coatings. Thin Solid Films 2008, 516, 4036–4039. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Pei, X.; Wang, Q.; Sun, X.; Wang, T. Effects of atomic oxygen irradiation on structural and tribological properties of polyimide/Al2O3 composite. Surf. Interface Anal. 2012, 44, 372–376. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.; Wan, H.; Chen, L.; Li, H.; Cui, H.; Ju, P.; Zhou, H.; Chen, J. Marvelous abilities for polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane to improve tribological properties of polyamide-imide/polytetrafluoroethylene coatings. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 12616–12627. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Tang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Gu, J.; Kong, J. Advanced aromatic polymers with excellent antiatomic oxygen performance derived from molecular precursor strategy and copolymerization of Polyhedraloligomeric silsesquioxane. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 20144. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, C.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yang, W.; Yu, B.; Yu, Q.; Cai, M.; Zhou, F.; et al. Modification of POSS and their tribological properties and resistant to space atomic oxygen irradiation as lubricant additive of multi-alkylated cyclopentanes. Friction 2024, 12, 884–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Qin, W.; Wu, X. Improvement of the atomic oxygen resistance of carbon fiber-reinforced cyanate ester composites modified by POSS-graphene-TiO2. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2016, 133, 211−218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.S.; Jones, A.; Farmer, B.; Rodman, D.L.; Minton, T.K. POSS-Enhanced Colorless Organic/Inorganic Nanocomposite (CORIN) for Atomic Oxygen Resistance in Low Earth Orbit. CEAS Space J. 2021, 13, 399. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Hu, Z.; Wu, Z.; Wu, G.; Ma, L.; Zhang, C.; Huang, Y. POSS-bound ZnO nanowires as interphase for enhancing interfacial strength and hydrothermal aging resistance of PBO fiber/epoxy resin composites. Compos. Part A 2017, 96, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, M.; Wang, W.; Men, X.; Liu, W. POSS grafted hybrid-fabric composites with a biomimic middle layer for simultaneously improved UV resistance and tribological properties. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2018, 160, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Zhang, P.; Wei, M.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, W. Amino-POSS grafted polyimide-based self-stratifying composite coatings for simultaneously improved mechanical and tribological properties. Polymers 2026, 18, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TB 10099-2017; Code for Design of Railway Station and Terminal. China Railway Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2017.

- Liao, W.; Huang, X.; Ye, L.; Lan, S.; Fan, H. Synthesis of composite latexes of polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane and fluorine containing poly(styrene–acrylate) by emulsion copolymerization. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2016, 133, 43455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minton, T.K.; Wright, M.E.; Tomczak, S.J.; Marquez, S.A.; Shen, L.; Brunsvold, A.L.; Cooper, R.; Zhang, J.; Vij, V.; Guenthner, A.J.; et al. Atomic-Oxygen Effects on POSS Polyimides in Low Earth Orbit. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 492–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, M.; Murray, V.J.; Wei, W.; Marshall, B.C.; Minton, T.K. Resistance of POSS Polyimide Blends to Hyperthermal Atomic Oxygen Attack. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 33982−33992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, S.; Jiang, H.; Zhai, R.; Liu, Y.; Li, T.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, L. Study on the Effects and Mechanism of Temperature and AO Flux Density in the AO Interaction with Upilex-S Using the ReaxFF Method. Coatings 2023, 13, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.; Kim, Y.; Sathish Kumar, S.K.; Kim, C.-G. Enhanced resistance to atomic oxygen of OG POSS/epoxy nanocomposites. Compos. Struct. 2018, 202, 959−966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Shi, Y.; Cui, M.; Ren, S.; Wang, H.; Pu, J. MoS2/WS2 Nanosheet-Based Composite Films Irradiated by Atomic Oxygen: Implications for Lubrication in Space. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 10307−10320. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, J.; Chai, L.; He, T.; Yu, F.; Wang, P. Carbon and Nitrogen Co-Doping Self-Assembled MoS2 Multilayer Films. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 406, 30−38. [Google Scholar]

- Diskus, M.; Nilsen, O.; Fjellvag, H.; Diplas, S.; Beato, P.; Harvey, C.; van Schrojenstein Lantman, E.; Weckhuysen, B.M. Combination of Characterization Techniques for Atomic Layer Deposition MoO3 Coatings: From the Amorphous to the Orthorhombic Alpha-MoO3 Crystalline Phase. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 2012, 30, 01A107. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.