Abstract

This article presents the results of the first stage of a four-phase research program aimed at the comprehensive evaluation and enhancement in the functional properties of polymeric packaging films intended for active food packaging systems through their modification with detonative nanodiamonds (DND). Stage I involved the characterization of ten commercial single- and multi-layer films without the addition of DND, differing in structure, base material, thickness, and intended application. The scope of analyses included the assessment of biological and physicochemical properties relevant to food contact, such as surface wettability (contact angle), thermal stability (TGA, DSC), antimicrobial and antiviral activity (using E. coli and M. luteus models), as well as the quality of thermal seals examined by SEM. Biological activity was assessed in accordance with ISO 22196:2011. The results revealed significant differences among the tested samples in terms of microbiological resistance, surface properties, and thermal stability. Films with printed layers exhibited the highest antimicrobial activity, whereas some polypropylene samples showed no activity at all or even supported microbial survival. Cross-sectional analysis of welds indicated that the quality of thermal seals is strongly dependent on the surface properties of the base material. The obtained results provide a reference point for subsequent research stages, in which DND-modified films will be analyzed regarding their effects on mechanical, barrier, and biological properties. Preliminary trials with nanodiamonds confirmed their high application potential and the possibility of producing films with increased hydrophilicity or hydrophobicity and durability, which are crucial for the development of modern active food packaging systems.

1. Introduction

Detonation nanodiamonds (DNDs) are ultra-fine diamond particles, typically a few nanometers in size, composed of sp3-hybridized carbon atoms. They exhibit a very high specific surface area and contain various functional groups (e.g., oxygen- and hydrogen-containing) which facilitate strong interactions with polymers and allow for chemical surface modification [1,2]. Detonation nanodiamonds (DNDs) are synthesized by detonating carbon-rich explosives. A key advantage of DNDs is their extremely-small primary particle size—usually in the range of single-digit nanometers—combined with the ability to produce them on an industrial scale, with annual output reaching several tons. Their ultra-small size results from the rapid detonation process, which lasts only a fraction of a microsecond [3], effectively limiting particle growth time. Nanodiamonds are produced by detonating a TNT and RDX mixture, followed by collecting the resulting soot. Pure nanodiamonds can be obtained from this soot after chemical purification [4].

Polymers are among the fastest-growing classes of engineering materials on account of their multiple advantageous properties, including low weight, flexibility, resistance to weathering, barrier performance, durability, and cost-effectiveness. Polymer-based products are increasingly used across a wide range of industrial sectors and in everyday applications [5,6]. Plastics are mass-produced for use in packaging, construction, electrical and electronic components, textiles, transportation, and agriculture [7]. The broad applicability of polymers stems from their favorable processing characteristics and service properties, making them attractive substitutes for traditional materials. In recent years, significant progress has been made in the development of polymer nanocomposites, in which nanoscale fillers are dispersed within the polymer matrix. This approach enables substantial enhancement in mechanical and functional performance. Another important trend is the design of novel polymer blends, which extend the application range of conventional or engineering-grade polymers by combining them with high-performance (engineering or specialty) polymers. Such blends may also facilitate the processing of otherwise difficult-to-handle high-molecular-weight polymers [8,9]. Advances in material science have significantly influenced food packaging, driven by consumer demand for convenience and longer shelf life. Modern packaging ensures food quality and safety by providing effective barriers, while key material properties include mechanical strength, durability, thermal stability, and antimicrobial functionality. The growing occurrence of foodborne pathogens outbreaks further underscores the need for antimicrobial packaging solutions to maintain safety across the supply chain [10,11].

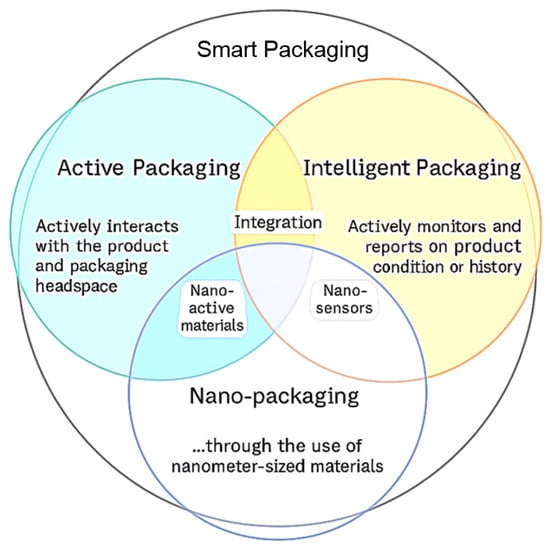

There are three main types of smart food packaging: intelligent packaging, active packaging, and nano-packaging (Figure 1). These categories represent distinct technological approaches aimed at enhancing food safety, monitoring product quality, and extending shelf life, and they are often combined to achieve synergistic effects.

Intelligent packaging, by contrast, focuses on monitoring the condition of the packaged product. It incorporates indicators or sensors that detect and communicate changes in environmental or product-related parameters such as temperature, pH, gas composition, or microbial activity. These systems do not directly affect the product, but instead provide crucial data about its status, facilitating better decision-making across the supply chain and contributing to the reduction in food waste [12]. Modern intelligent packaging combines advanced material science with innovative manufacturing technologies to redefine product preservation. These solutions promote sustainability, efficiency, and adaptability across sectors such as food, pharmaceuticals, and consumer goods. In food packaging, nanotechnology enhances barrier properties, extends shelf life, and provides antimicrobial protection [13].

Figure 1.

Relationships between the definitions of active, smart, and nano-packaging in the context of intelligent packaging systems. Reprinted with permission from [14]. Copyright 2025 Elsevier.

Nano-packaging is an emerging field that applies nanotechnology materials and structures with at least one dimension in the nanometer range (1 ÷ 100 [nm])—to enhance packaging functionality. This enhancement may involve the incorporation of nano-active materials, which provide improved barrier and antimicrobial properties, or nano-sensors, which enable highly sensitive detection of biochemical and environmental changes [15,16,17].

The overlapping areas in the diagram emphasize the potential for integrated smart-packaging solutions. For example, nano-active materials can be embedded into active packaging systems to improve their efficiency and performance, while nano-sensors can enhance intelligent packaging through increased sensitivity and specificity. At the center of the Venn diagram lies the convergence of all three approaches—active, intelligent, and nano-enabled—representing the most advanced and multifunctional packaging systems currently under development [14].

The incorporation of diamond nanoparticles into biopolymer matrices enhances mechanical and physicochemical properties, barrier efficiency, moisture resistance, flexibility, and overall durability. Furthermore, such modifications impart additional functionalities, including antimicrobial and antioxidant activity, ultraviolet protection, and effective shielding against both internal and external contaminants such as gases, moisture, organic compounds, microorganisms, dust, vibrations, mechanical shocks, and other factors [18]. Among the various carbon-based nanomaterials, nanodiamond particles [19] stand out due to their excellent biocompatibility and low cytotoxicity. Their chemically inert diamond core is surrounded by a highly accessible and modifiable surface rich in functional groups. These surface functionalities allow for precise adjustment of interactions with diverse environments and enable both covalent and non-covalent binding of drugs or biomolecules. Nanodiamond particles are also well-suited to incorporation into composites and hybrid materials, particularly in biomedical applications [20]. Diamond nanoparticles occupy a unique position due to their outstanding mechanical strength, chemical inertness, tunable surface chemistry, biocompatibility, and remarkable optical and electronic properties, particularly when doped with specific elements. These attributes make them an important platform in the ongoing development of nanoscience and nanotechnology [19,21].

Nanodiamonds are extremely-fine diamond particles which, as a result of their nanoscale size, unique physicochemical properties, and large surface-to-volume ratio—with surfaces that are readily chemically modifiable—have attracted significant interest among biologists, chemists, and physicists [22].

Detonation nanodiamonds (DND) are exceptionally hard and chemically resistant due to their diamond crystal lattice, which confers high thermal stability and resistance to oxidation and radiation [23,24]. Additionally, they are optically transparent and possess excellent thermal conductivity, which in packaging materials reduces UV light penetration and enhances thermal stability [2]. The surface of DND can be easily functionalized—using plasma treatment or chemical methods [23]—allowing for the attachment of specific groups such as bactericidal or fluorescent moieties. This significantly broadens their applicability in active materials. Surface modifications greatly influence the activity of DND, including their antimicrobial performance [23,24]. Overall, DND are biologically inert and biocompatible. They exhibit the lowest cytotoxicity compared to other carbon nanomaterials (e.g., graphene, carbon nanotubes). Their stability under harsh (e.g., corrosive) conditions and resistance to degradation make them particularly attractive for use in food-related environments [24].

A review of the available literature clearly indicates that although carbon nanomaterials—such as carbon nanotubes and graphene—have been extensively investigated with respect to their influence on the barrier and mechanical properties of polymers, detonation nanodiamonds (DND) remain a comparatively underexplored material in the context of packaging technologies [25]. Karami et al. [26] emphasize that nanodiamonds have thus far been studied far less frequently in polymer composites compared with other carbon nanofillers and carbon nanostructures, such as graphene or nanotubes, drawing attention to the absence of systematic research addressing the mechanisms governing their interactions with polymer matrices. Similar conclusions are presented by Prasad et al. [27], who point to a “significant research gap” concerning the structure, properties, and functionality of nanodiamond-modified polyurethanes.

As a consequence, the number of studies devoted directly to the incorporation of nanodiamonds (ND) into polyethylene matrices (LDPE, HDPE, LLDPE, etc.) remains very limited. At the same time, it is well known that polyethylene inherently exhibits weak barrier properties toward gases and vapors. As highlighted by Fu et al. [28], the insufficient oxygen barrier of polyethylene films significantly restricts their applicability in packaging systems. The lack of internal mechanisms enabling barrier enhancement further motivates the search for functional fillers capable of increasing gas impermeability, among which nanodiamonds may be considered a promising—though still poorly studied—candidate.

The existing studies on ND–polyethylene composites focus primarily on mechanical and thermal properties, whereas barrier characteristics remain almost completely unexplored. For example, Morimune-Moriya et al. [29] demonstrated that small additions of nanodiamonds in LLDPE composites led to increases in Young’s modulus, tensile strength, elongation at break, and impact resistance. However, none of these studies investigated the effect of nanodiamonds on oxygen transmission rate (OTR), water vapor transmission rate (WVTR), or other parameters relevant to evaluating barrier performance.

It is known that nanodiamonds may significantly influence the barrier properties of packaging materials, particularly with respect to oxygen permeability and antimicrobial activity. Mitura and Zarzycki [30] note that the incorporation of functionalized nanodiamonds into polymeric packaging layers may result in substantial modifications in barrier performance; however, the authors do not provide systematic experimental evidence. Likewise, Amini et al. [31] describe only a single instance of reduced oxygen permeability in EVA films containing nanodiamonds, which further underscores the fragmentary and incidental nature of existing reports.

Taken together, these findings clearly demonstrate the presence of a pronounced research gap. While on the other hand, polyethylene clearly requires substantial improvements in barrier performance to be effectively applied in advanced packaging systems [26]. To date, no consensus—and more importantly, no sufficiently extensive empirical data—exists that would allow for a reliable assessment of how nanodiamond incorporation affects the barrier properties of polyethylene. The lack of systematic studies on oxygen and moisture permeability in PE/ND composites highlights the need for comprehensive, well-controlled investigations.

Currently available data describing the influence of nanodiamonds on OTR and WVTR in polyethylene-based films are scarce, fragmentary, and inconsistent, which prevents the formulation of robust conclusions. For this reason, the reviewed literature provides strong justification for undertaking broader and more systematic research on the barrier properties of polyethylene films modified with nanodiamonds.

Collectively, these observations indicate a clear lack of comprehensive, structured studies addressing the influence of detonation nanodiamonds on the fundamental barrier properties of polymer films—particularly water vapor transmission rate, oxygen permeability, and surface characteristics such as hydrophobicity or hydrophilicity. The vast majority of published works focus on the mechanical or thermal stabilization of engineering polymers (e.g., PET, PS, epoxy resins), whereas materials relevant to food-packaging applications—such as LDPE, PP, or PLA—remain far less explored. Importantly, only a limited number of studies provide reliable baseline data for reference films, which are essential for assessing the direction and magnitude of DND-induced changes.

As a consequence, the fundamental mechanisms by which DND affect barrier properties, biological behavior, and thermal stability of thin polymer films intended for food-contact applications remain insufficiently understood. This knowledge gap restricts the rational design of advanced, biocompatible, and antimicrobial next-generation packaging materials. The present study constitutes Part I of a multi-stage research program aimed at systematically elucidating the role of detonation nanodiamonds in active polymer packaging systems. This initial stage focuses on the baseline characterization of reference polymer films and the assessment of the direct effects of DND incorporation on biological activity, surface hydrophobicity or hydrophilicity, and thermal stability, thus providing the essential scientific foundation for the development of optimized DND-modified active films.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Samples

Ten types of polymer-based packaging films (Plastmoroz, Białogard, Poland) were used in the experimental investigations. They differed in terms of the number of layers, thickness, and intended application. The set included both monolayer (monolithic) films and multilayer laminated structures. The samples differed in their layer architecture, total thickness, and types of base materials (e.g., polypropylene (PP), low-density polyethylene (LDPE), poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET)). Some films also contained additives or coatings dedicated to specific applications (e.g., food, technical, or pharmaceutical packaging). A detailed specification of the films tested, including their physical and technological parameters, is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of selected packaging polymer films used in material and barrier property studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of selected packaging polymer films used in material and barrier property studies.

| No. | Sample Code | Description of Packaging Film Structures | Standardized Abbreviation | Thickness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [μm] | ||||

| 1 | A | Monolayer film consisting of non-oriented poly(ethylene terephthalate) | PET | 9 |

| 2 | B | Monolayer film consisting of non-oriented polypropylene | PP | 23 |

| 3 | C | Monolayer film consisting of non-oriented low-density polyethylene | LDPE | 55 |

| 4 | D | Monolayer film composed of polypropylene mechanically oriented in one direction | PP_MO (Cast) | 18 |

| 5 | E | Monolayer film composed of low-density polyethylene mechanically oriented in one direction | LDPE_MO (Cast) | 32 |

| 6 | F | Monolayer film consisting of non-oriented poly(ethylene terephthalate), with aluminum surface metallized | PET-met (Al) | 21 |

| 7 | G | Monolayer film consisting of non-oriented poly(ethylene terephthalate), with surface printed | PET-print | 19 |

| 8 | H | Multilayer film consisting of non-oriented poly(ethylene terephthalate) and non-oriented low-density polyethylene. | PET/LDPE | 83 |

| 9 | I | Multilayer film consisting of non-oriented poly(ethylene terephthalate), non-oriented polyethylene low-density, and non-oriented poly(ethylene terephthalate) with surface printed | PET/LDPE/PET-print | 190 |

| 10 | J | Multilayer film consisting of metallized non-oriented poly(ethylene terephthalate and non-oriented polyethylene low-density, with surface printed | met (Al)-PET/LDPE-print | 156 |

| 11 | K | Control sample; a reference film coated with a thin layer of silica (SiO2) | SiO2 | - |

Table 1 presents a set of eleven types of polymer-based packaging films, labeled with letters A through K, selected for their representativeness of the packaging materials currently used. The selection includes both monolayer and multilayer films, varying in chemical composition, thickness, functional surface layers (e.g., printing, metallization), and manufacturing technology (orientation, lamination, coating).

The diversity of the tested samples was designed to allow for a comprehensive evaluation of how material structure affects physicochemical, mechanical, and microbiological properties. These films are commonly used in the packaging industry, from simple base layers to advanced multilayer laminates with enhanced barrier performance.

- Film A (PET)—a thin, monolayer film made of polyethylene terephthalate (PET), g = 9 µm thick, characterized by high transparency and chemical stability; used as a reference material.

- Film B (PP—cast polypropylene)—a g = 23 µm thick, non-oriented cast polypropylene film, often used as an inner sealing layer in multilayer laminates on account of its good sealing properties.

- Film C (LDPE)—a standard, monolayer, low-density polyethylene (LDPE) film, g = 55 µm thick, offering flexibility and moisture resistance; widely applied in flexible packaging.

- Film D (PP_MO)—a monoaxially oriented polypropylene film (g = 18 µm), commonly used as an external layer in packaging due to increased stiffness and mechanical resistance.

- Film E (LDPE_MO)—a machine-direction-oriented LDPE film (g = 32 µm), offering improved mechanical properties, while maintaining good flexibility.

- Film F (PET-met)—a g = 21 µm thick metallized PET film with an aluminum layer, valued for its excellent barrier properties against oxygen, carbon dioxide, and light.

- Film G (PET-print)—a g = 19 µm thick PET film with surface printing, serving decorative or informational purposes in multilayer structures.

- Film H (PET/LDPE)—a standard two-layer laminate (g = 83 µm) composed of non-oriented PET and LDPE, combining barrier performance with heat sealability.

- Film I (PET/LDPE/PET-print)—a printed variant of film H, with a total thickness of g = 190 µm, typically used in consumer packaging for visual appeal and product information.

- Film J (met(Al)-PET/LDPE-print)—a complex multilayer laminate (g = 156 µm) containing aluminum metallization and surface printing, widely used in packaging requiring high barrier performance (e.g., coffee, spices, pharmaceuticals).

- Film K (SiO2)—a reference film coated with a thin layer of silica (SiO2), known for its high transparency and exceptional barrier properties; used for comparison with traditional and nanocomposite barrier solutions.

Three of the films tested, and indeed the base material, contained printed layers, indicating their intended applications. These were: PET-met/LDPE-print, PET-print, and PET/LDPE-print. The PET, PP, PP_MO, and LDPE_MO films consisted of a single type of material. The remaining films were either laminates, which is typical, as monomaterial films are often used as components in laminates or more complex packaging structures. The film with the highest number of layers was PET-met/LDPE-print, containing both a metallized and a printed layer—indicating its direct use as final packaging. This film is used for packaging protein supplements for athletes. The PET-print film is used for pet food packaging, and the PET/PE-print is used for refill packaging of liquid soap. The multilayer PET/PE film is widely used in vacuum and MAP (Modified Atmosphere Packaging) systems for food products such as cheese, meat, cold cuts, fish, and ready-to-eat meals. PET-met is used for packaging snacks, sweets, coffee, tea, chips, instant products, and powders, as well as for decorative purposes due to its glossy finish and enhanced barrier properties. PP film is used for packaging bread, cookies, confectionery products, labels, and printed wrappers. LDPE_MO is used in stretch packaging, as an easy-peel layer, in bulk packaging, and for producing ice bags. LDPE film is commonly used for packaging fresh and frozen foods, bakery products, and fruits and vegetables, and serves as a sealing layer in multilayer laminates. PP_MO is used for packaging dry foods, bakery and confectionery products, cosmetics, and hygiene articles. PET is used for collective packaging, for products requiring high aesthetic and mechanical standards, for labels, and—after lamination or metallization—for barrier applications.

For the purposes of microbiological surface characterization and assessment of antibacterial and antiviral activity, each sample was assigned a unique laboratory code—presented in Table 2. The aim of the test was to evaluate the interaction between the ten types of film samples and bacterial cells; i.e., to determine their antimicrobial activity. The surfaces of the samples tested were cleaned with ethanol (except for the PET-print sample, when cleaning caused surface damage), and subsequently sterilized using UV irradiation for 30 min.

Table 2.

Labeling of tested samples used in microbiological characterization.

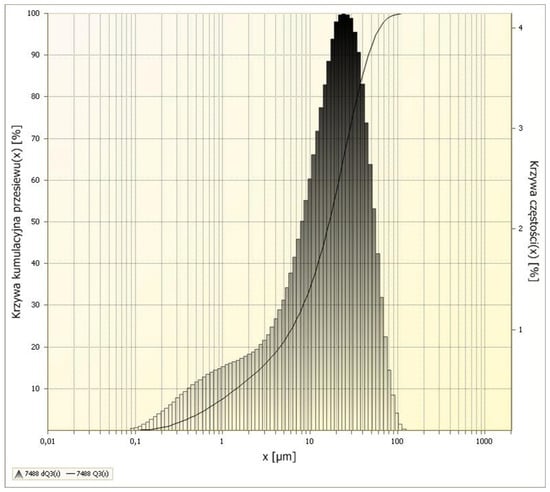

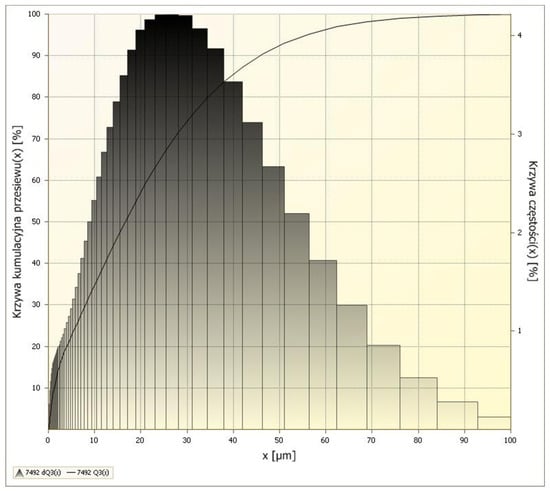

Additionally, a preliminary morphological and granulometric analysis was conducted on detonation-synthesized nanodiamond (DND) (Adamas Nanotechnologies, Raleigh, NC, United States of America) powder of an average particle size of approximately 30 nm, which is intended for use as a functional additive for modifying the properties of selected films in the subsequent stages of the project.

2.2. Sample Preparation

The polymer film samples were prepared appropriately for each type of analysis. The portion of the samples intended for thermal, microscopic, and surface characterization was previously subjected to linear thermal sealing, carried out under the conditions specified in Section 3.3.

For TGA and DSC analyses, the samples were cut into circular disks of a diameter of 4 mm. For SEM observations and contact angle measurements, rectangular specimens were prepared with dimensions of 10 mm × 40 mm.

The samples designated for scanning electron microscopy (SEM) were first reinforced by coating both sides with a thin layer of a mixture of LH 288 epoxy resin and H 508 hardener. This procedure ensured the structural stability of the films and enabled the preparation of cross-sectional cuts suitable for microscopic observation.

2.3. Thermal Sealing of Samples

All films tested, as listed in Table 1, were subjected to linear thermal sealing. The sealing of samples of dimensions of 5 cm × 20 cm was performed using a PSF-200 type laboratory-grade impulse sealer (Zenter, Sandomierz, Poland). The sealing workstation was equipped with additional components that enabled precise control and monitoring of the process, including: a voltage regulator (for controlling heating power), a dynamometer (for measuring the pressure exerted by the sealing arm), and a time controller (for accurately setting the duration of the heat pulse).

The sealing process was based on the principle of localized heating of the material via the flow of an electric pulse through a resistance wire, which heated up and directly transferred heat to the film surface located in the sealing zone. After the heat pulse ended, the pressure was maintained for a short time, allowing for the joint to stabilize through controlled cooling under compression.

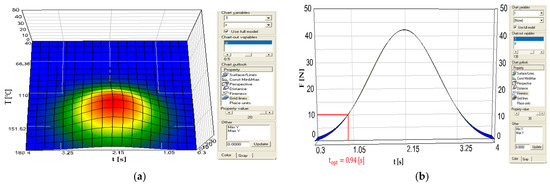

The initial parameter ranges—sealing time t ∈ [0.3; 4.0] s, sealing jaw temperature T ∈ [40; 180] °C, and sealing pressure p ∈ [0.2; 0.8] MPa—were preliminarily estimated using a numerical approach implemented in a proprietary application developed in the APDL (ANSYS Parametric Design Language) environment within ANSYS software (ANSYS Multiphysics/LS-Dyna program version 16.2, 2015 SAS IP, Inc., Cary, NC, USA) are [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. This allowed for a significant reduction in the number of experimental trials by predicting process behavior and accounting for nonlinear dependencies between the sealing parameters and joint performance.

Precise, optimal values for each type of polymer film were then determined experimentally using a multi-criteria optimization method, supported by a custom-developed tool—EPLANNER program [46], designed to assist in the technological design of material engineering processes. The software enabled the modeling of a response surface F = F (T, t) in three-dimensional parameter space, with the fixed sealing pressure of p = 0.5 MPa, which—based on preliminary tests—ensured maximum joint strength.

The example shown in Figure 2a,b illustrates the response surface characteristic F = F(T, t) for a thin, printed PET film (Foil G, PET-print, g = 19 µm). A cross-section at a constant temperature T = 135 °C (Figure 2b) showed that a basic sealing time of t = 0.94 s ensures the minimum acceptable joint strength of F = 10 N. An increase in the sealing time to t = 2.15 s led to the maximum observed value of F = 43 N; however, further extension of the thermal pulse is not industrially justified due to the significant extension of the cycle time and increase in production costs. The adopted conditions (T = 135 °C) represent a compromise between the mechanical efficiency of the joint and the need to maintain the integrity of the print layer.

Figure 2.

Subsequent stages of determining the optimal technological parameters for printed PET film (foil G, PET-print, g = 19 µm) sealing using the chart module in the EPLANNER program. (a) three-dimensional response surface illustrating the combined effect of sealing temperature and sealing time on seal strength; (b) identification of the optimal sealing time at a fixed sealing temperature based on the seal strength response curve.

Based on the analysis of the graph shown in Figure 2a, it can be observed that the maximum joint strength, reaching F = 43 N, is achieved at a welding time of t = 2.15 s. While longer process duration makes it possible to maximize the joint strength, extending the welding time beyond a certain point results in a disproportionate increase in the production cycle time and unit costs. From the perspective of industrial applications, where both mechanical performance and economic efficiency must be balanced, such a prolonged welding time might not be economically justified. In practice, therefore, an optimum compromise is sought between joint strength and production efficiency, which requires the identification of process parameters that ensure sufficient mechanical quality at acceptable manufacturing costs.

Table 3 summarizes the optimal welding parameters—T, t, and p—determined for all tested films, taking into account their varying thicknesses (range g = 9–190 µm) and layer structures (monolayers, oriented films, and two- and three-layer laminates). Analysis of the results confirms the significant effect of film thickness and structure on thermal conductivity and the required welding energy level. Thin PET (g = 9 µm) and PP (g = 23 µm) monolayers achieved the required strength at the lowest temperatures and times, while complex, thick laminates—particularly PET/LDPE/PET-print (g = 190 µm) and met(Al)-PET/LDPE-print (g = 156 µm) structures—required higher temperatures and longer pulses, which is directly related to the limited thermal conductivity of the polyethylene layers and the presence of metallized barrier layers.

Table 3.

Summary of optimal welding temperature Topt, time topt, and pressure popt values for the studied single-layer and multilayer polymer films of varying thicknesses.

Taking into account parameters individually selected for each type of foil not only improved the quality of the formed welds, but also enabled further mechanical analyses to be carried out under conditions guaranteeing full repeatability and comparability of the obtained results.

The contact angle was measured using the sessile drop method with a device equipped with dedicated analysis software. The instrument was fitted with a high-resolution camera and backlighting, enabling precise recording of the droplet profile on the sample surface. Prior to measurements, the surfaces of the tested films and DND were thoroughly cleaned to remove any organic contaminants and dust, using ethanol and demineralized water, followed by drying in a nitrogen stream. Each sample was then placed on a horizontal stage. Measurements were carried out under controlled conditions, typically at a temperature of 23 °C ± 1 °C and relative humidity of 50% ± 5%.

A single droplet of demineralized water with a volume of 3 µL was deposited on the sample surface using an automatic pipette, ensuring that the pipette tip was positioned as close as possible to the surface to avoid deforming the droplet upon contact. After deposition, the sample was left for a few seconds until the droplet shape stabilized under the influence of adhesion forces and surface tension. A side-view image of the droplet was then recorded, and the captured profiles were analyzed using the software. The contact angle was calculated using a profile-fitting algorithm based on the Young–Laplace equation, which provides the most reliable angle determination for droplets with volumes of a few microliters, where gravity significantly affects the curvature of the liquid surface.

For each sample, five independent measurements were performed at different locations on the surface (n = 5), according to the statistical procedure described in Section 2.5, ensuring the representativeness and reliability of the results, after which the mean value and standard deviation were calculated. In the case of porous materials, such as compressed nanodiamonds, the change in contact angle over time was additionally monitored by recording successive images at 1-s intervals over a period of one minute. This allowed for assessment of the effect of liquid absorption into the pores and confirmation of wetting stability.

All measurements were performed using identical droplet volumes and under the same environmental conditions to ensure comparability of the results. The obtained contact angle values were used to evaluate surface hydrophilicity or hydrophobicity and the quality of interfacial interactions in polymer–nanodiamond systems.

2.4. Applied Measurement Methods

2.4.1. Static Contact Angle Measurement

Wettability was measured using a See System E device (Advex Instruments, Brno-Komín, Czech Republic). Water was used as the testing liquid. Samples were placed at an appropriate height on the stage to ensure accurate contact angle measurements. Then, 3 μL droplets were applied to the film surfaces, and photographs were taken under properly adjusted lighting conditions. The contact angle was calculated by selecting three points on each droplet using dedicated software, which then determined the contact angle of the studied packaging film. For laminates, the side intended for direct contact with the product or located on the inside of the packaging was used for wettability measurements and antimicrobial activity testing.

To enable contact angle measurements on detonation nanodiamond (DND) powder, the material was compacted into solid pellets by cold pressing, without the use of any binders or additives. An amount of 150 mg of purified DND powder, with an average particle size of below 30 nm, was weighed. Prior to compaction, the powder was cleaned by acid treatment (HNO3/H2SO4 mixture) and subsequently dried at 80 °C for 12 h. The dry powder was then directly loaded into a stainless-steel cylindrical die with an internal diameter of 13 mm. The powder surface was gently leveled using a glass spatula, avoiding any pre-compaction. The die was placed in a uniaxial hydraulic press, and a stainless-steel piston was used to apply pressure. The powder was compacted under a uniaxial load of 10 tons, corresponding to an approximate pressure of 75 MPa based on the die cross-section, for a duration of 5 min. The process was carried out at ambient temperature, without heating, to avoid any thermal or chemical alteration in the nanodiamond surface. After releasing the pressure, the compact was carefully removed from the die to avoid mechanical damage. The resulting pellet had a cylindrical shape of a diameter of 13 mm and a thickness of approximately 1.2 mm. The top surface was smooth and uniform, suitable for reliable contact angle measurements.

Prior to testing, the pellets were stored in a desiccator containing activated carbon for 24 h to eliminate surface moisture and ensure consistent measurement conditions. Surface topography analysis was performed before the wettability test. It was found that the compacted surface exhibited low porosity and moderate micro-roughness (Sa = 0.25 µm), as typical for cold-pressed compacts formed from nanopowders.

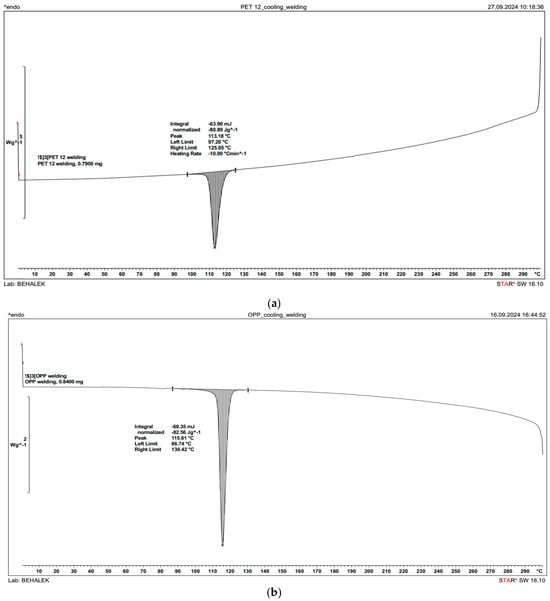

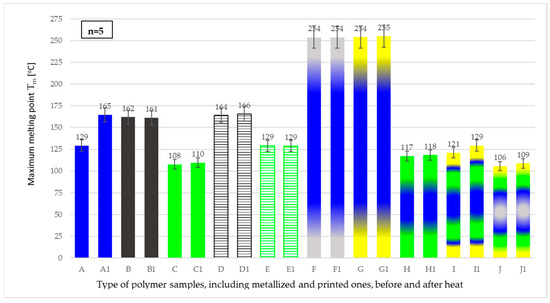

2.4.2. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) tests were performed with a Mettler Toledo DSC instrument. Samples were cut to fit the crucible, and their weight was determined by subtracting the mass of the empty crucible from the mass of the crucible with the sample. After weighing, the crucible was sealed using a press and placed into the device to record the DSC curve. Samples were labeled according to their material composition. Detailed results are included in the Appendix A.

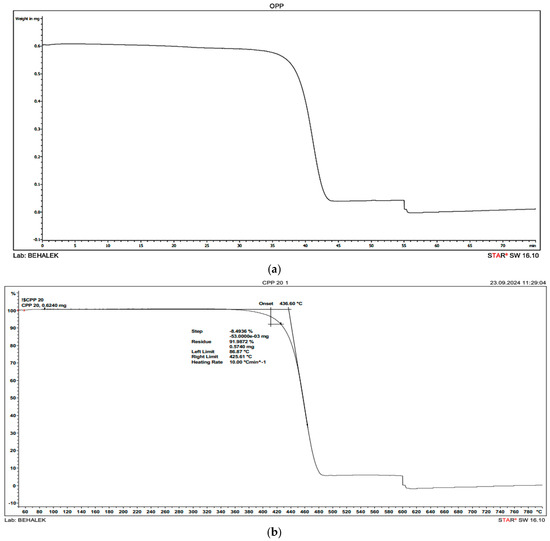

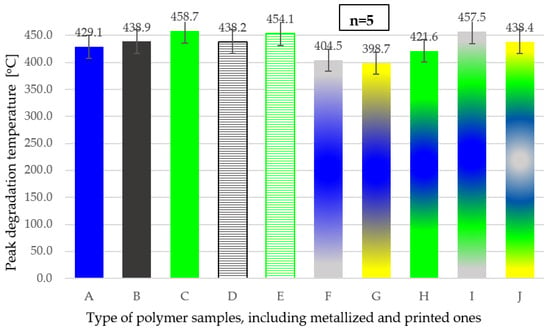

2.4.3. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

TGA analyses were conducted using a Mettler Toledo TGA instrument. Samples were prepared similarly to the DSC tests, but placed in ceramic crucibles that did not require pressing. The TGA device includes an internal scale; so, additional weighing was unnecessary. Samples were labeled in the same manner as for DSC. Detailed results are included in the Appendix B.

2.4.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

The cross-sectional morphology of the polymer films was examined using a Tescan scanning electron microscope (SEM). Prior to imaging, the film samples were carefully cut to appropriate dimensions and embedded in epoxy resin on both sides to provide mechanical support and facilitate precise cross-sectional observation. After the resin had fully cured, the embedded samples were trimmed using precision pliers to expose the cross-section of interest. In order to minimize charging effects during SEM imaging, the samples were mounted on to SEM stubs using conductive carbon tape. This not only ensured effective dissipation of electrostatic charges from the sample surface, thereby improving image clarity, but also minimized the generation of secondary signals during SEM analysis, an important factor for subsequent chemical composition studies using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS).

SEM observations were conducted under high vacuum conditions at an accelerating voltage of 5÷10 kV, using secondary electron (SE) detection mode. Representative micrographs were acquired at various magnifications (e.g., 200× to 5000×), allowing for the assessment of layer continuity, internal structure, interfacial adhesion between layers (in multilayer films), and the presence of structural defects such as voids, delaminations, or microcracks.

2.4.5. Tested Bacterial Strains

Two bacterial strains were selected for microbiological testing:

- Escherichia coli (EC, strain CCM No. 3954, Czech Collection of Microorganisms), a Gram-negative bacterium commonly used as a model organism in medical and biotechnological bioassays. Cultures were grown in a 30 mL soybean-based medium (Casei Digest Medium, HiMedia) and incubated at 37 °C in an Incucell incubator (BMT Medical Technology). After incubation, inoculum was applied to agar plates and used for testing after 24 h.

- Micrococcus luteus (ML), a Gram-positive bacterium naturally present on human skin (hands), characterized by yellow colonies. Bacteria were obtained by fingerprinting on Blood Agar, cultured for 48 h at 37 °C, and applied to agar plates for testing after 48 h.

2.4.6. Evaluation of Antibacterial Activity According to ISO Standards

Antibacterial tests followed the ISO 22196:2011 standard [47] for measuring antibacterial activity on plastics and other non-porous surfaces. Bacterial inocula were prepared with defined concentrations of E. coli (3.0 × 109 CFU/mL) and M. luteus (2.2 × 109 CFU/mL). A volume of 20 µL inoculum was applied on to each sample surface and covered with a sterile coverslip to evenly distribute the bacteria and ensure direct contact with the sample. Samples were incubated for 24 h at 35 °C and ≥90% relative humidity. After incubation, samples and coverslips were transferred to sterile tubes containing 10 mL saline and shaken vigorously at 1300 rpm for 3 min at 25 °C.

For each film, five independent biological replicates were performed, each consisting of three technical replicates (n = 5 biological × 3 technical). The limit of detection was 10 CFU/mL, and values below this threshold were reported as <10 CFU/mL.

Images of the plates with colonies were captured using a digital camera and analyzed with a MATLAB (R2024a) script that automatically identified and counted colonies based on pixel intensity thresholds. These thresholds were established through calibration tests using known CFU concentrations and were compared with manual colony counts, which allowed for validation of the script’s effectiveness and accuracy. This procedure ensured consistency of the results and minimized errors associated with variations in illumination and image contrast.

Mean values from the five biological replicates and the corresponding standard deviations are presented in the tables, providing complete information on data variability.

2.4.7. Evaluation of Bacterial Colonies on Agar Plates

The viability of bacteria in eluates was assessed by plating 200 µL of the suspension on Brain Heart Infusion Agar plates. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h (E. coli) and 48 h (M. luteus). Measurements were conducted in triplicate (labeled A, B, C). A control sample of SiO2 (microscope slide) was analyzed to verify test accuracy. The results were documented photographically; colonies were visually evaluated, and antimicrobial activity values were calculated as described below.

Image analysis was performed using an automated MATLAB script (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA.). Images were processed to display colonies in white or yellow on a black background. Colony-forming units (CFU) were quantified, where each colony corresponds to proliferation from a single bacterial cell. Means and standard deviations were calculated for all parameters.

2.4.8. Calculation of the Value of Antimicrobial Activity (R)

Antimicrobial activity (R value) was determined based on the ISO 22196:2011 standard [47], which defines R as the logarithmic reduction in the number of viable bacteria after 24 h of contact with the tested surface:

where:

R—the value of antimicrobial activity,

A—the average number of Colony-forming units (CFU) after contact with the untreated (control) sample (immediately).

B—the average number of CFU after contact with the untreated (control) sample after 24 h,

C—the average number of CFU on the tested (antimicrobial) sample surface after 24 h.

2.5. Statistical Calculation Methodology

In accordance with the classical theory of sampling and the principles of statistical analysis of measurement data, the sample size was determined independently for each type of measurement using a formula derived from the theory of random sampling. The calculations accounted for the assumed confidence level α = 0.05, the permissible estimation error, and the variance in the results. The applied formula is as follows [46]:

where tcr(α; df) is the critical value of Student’s t-test at the significance level α and degrees of freedom df.

For the analyzed parameters: static contact angle, maximum melting temperature, degradation temperature and bacterial colony count (CFU), the following minimum number of repetitions was obtained: n = 5 (

). Each of these parameters was characterized by a different variance and required a different estimation accuracy, therefore the sample size was calculated separately for each type of measurement. The calculated minimum number of repetitions allows for obtaining results that are statistically significant and representative of the population.

To assess the quality of the experimental data and eliminate potential outliers (gross errors), the following statistical tests were applied:

- Grubbs’ test—used to identify single outlying observations in small samples, assuming normal distribution;

- and , and and tests—based on extreme values within the dataset, applied in the context of data stability and conformity analysis, as recommended by European standards and commonly used industrial data evaluation procedures.

The following were calculated for each investigated parameter:

- Arithmetic mean value as a measure of central tendency;

- Unbiased standard deviation s, calculated according to the following formula:which ensures an unbiased estimate of sample variance relative to population variance.

The results of the statistical analysis were presented as mean values with corresponding standard deviations, allowing for an assessment of measurement repeatability and precision. The statistical methodology adopted complies with current standards for experimental data analysis in materials science and engineering research.

2.6. Acceptance Criteria for Evaluating the Effectiveness of DND-Induced Film Modification

To enable an objective evaluation of the effectiveness of polymer film modification following the incorporation of detonative nanodiamonds (DND), a set of quantitative acceptance criteria has been established. These criteria allow for the identification of changes that are technologically significant and serve as the basis for validating subsequent research stages. Detailed results about deagglomeration are included in the Appendix B. The criteria encompass four key domains:

- •

- Surface wettability modification

A minimum change of ±20% in the static contact angle relative to the reference material is required. An increase in contact angle is expected for hydrophobic nanodiamonds (DND-HB), whereas a decrease is expected for hydrophilic variants (DND-HL). This threshold corresponds to values widely recognized in the literature as technologically relevant and statistically verifiable in thin polymer films.

- Thermal stability

This criterion includes: a reduction in the onset degradation temperature (Tonset) by at least 10 °C, or an increase in thermal stability manifested by a higher residual mass after decomposition in TGA analysis. These requirements enable the assessment of whether DND improve thermal resistance and mitigate the typical LDPE tendency to form volatile degradation products.

- Antimicrobial and antiviral activity

Films modified with DND must demonstrate measurable biological activity, defined as: a minimum 1-log (≥90%) reduction in bacterial CFU counts for E. coli or M. luteus after standardized exposure, or a statistically significant reduction (p < 0.05) in viral particle activity, as evaluated using ISO-compliant antimicrobial and antiviral test methods.

These thresholds correspond to internationally recognized benchmarks for classifying materials as exhibiting functional antimicrobial activity.

- Oxygen Transmission Rate (OTR)

The introduction of detonating nanodiamonds (DND), both DND-HL and DND-HB fractions, modifies the gas diffusion pathway in the polymer matrix. Nanoparticles, acting as oxygen-impermeable dispersed inclusions, increase the diffusion path’s tortuosity, extending the effective permeation path length and limiting the oxygen transport rate. This effect is more pronounced with better nanodiamond dispersion and higher nanodiamond effective number blocking the diffusion-convection mixture in the polymer. A reduction in OTR of 25%–35% is expected, depending on the film type and additive level.

- Surface morphology and structural integrity

SEM imaging must confirm the absence of undesired defects such as pores, microcracks, discontinuities in the base layer, or macro-aggregates of nanodiamond particles. This criterion reflects the well-established sensitivity of thin polymer films to structural imperfections that can significantly impair their barrier and mechanical properties.

- Mechanical performance

A minimum 20% increase in tear resistance relative to the reference samples is required. This threshold corresponds to typical values recognized as functionally meaningful improvements in polymeric materials modified with nanoscale fillers.

The proposed criteria constitute a preliminary but structured framework that will be further refined in subsequent research phases, particularly in light of data concerning DND deagglomeration efficiency, particle distribution homogeneity, and the detailed mechanisms of interaction with the polymer matrix. Stage I therefore serves as an essential starting point, providing a clearly defined baseline for the systematic evaluation of the functional effectiveness of DND-induced film modification.

3. Results

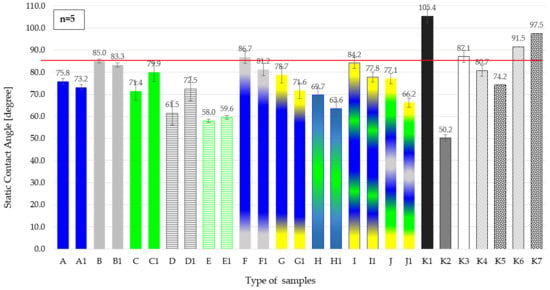

3.1. Static Contact Angle Measurement

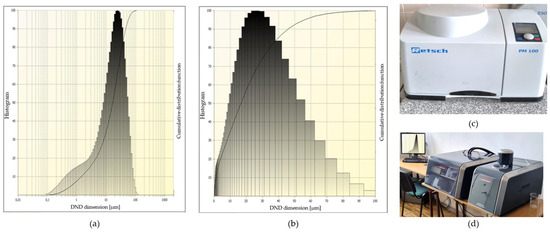

Figure 3 presents a comparison of the static contact angles for the ten analyzed polymer films, measured both before and after linear thermal sealing. For each film, two values are shown: one corresponding to the material in its original state and the second after thermal sealing. This presentation enables an assessment of the influence of the sealing process on the wettability of the tested materials. The data are shown as a bar chart, with sample identifiers on the horizontal axis and contact angle values (in degrees) on the vertical axis. Error bars indicate the variability and repeatability of the measurements. For comparison, the contact angles of compressed hydrophobic (DND-HB) and hydrophilic (DND-HL) nanodiamond powders were also measured and included in the figure, highlighting their distinctly different wetting properties compared with the polymer films. Additionally, the contact angles of LLDPE films doped with DND powders of different surface characteristics were determined.

Figure 3.

Static contact angle of individual polymer films before and after linear thermal sealing, and of compressed nanodiamond powder with hydrophobic (DND-HB) and hydrophilic (DND-HL) properties and four films with added nanodiamonds, for comparison. Film designations are consistent with those presented in Table 1: a single letter refers to the film before sealing, while the same letter with subscript ‘1’ indicates the corresponding film after sealing: A—PET; B—PP; C—LDPE; D—PP_MO; E—LDPE_MO; F—PET-met (Al); G—PET-print; H—PET/LDPE; I—PET/LDPE/PET-print; J—met (Al)-PET/LDPE-print; K1DND_HB—compressed hydrofobial nanodiamond DND; K2—DND_HF—compressed hydrofobial nanodiamond DND K1—LLDPE; K2—film LLDPE with the addition of 0.01% by weight DND; K3—film LLDPE with the addition of 0.05% by weight DND. K4—film LLDPE with the addition of 0.02% by weight DND_HF; K5—film LLDPE with the addition of 0.05% by weight DND_HF; K6—film LLDPE with the addition of 0.02% by weight DND_HB; K7—film LLDPE with the addition of 0.05% by weight DND_HB.

Figure 4 therefore presents the measured static contact angles of selected polymer films, their thermally sealed counterparts, compressed DND powders with different surface properties, and four LLDPE films containing DND additives. The vertical axis shows the contact angle (in degrees), while the horizontal axis lists the sample identifiers. The results indicate that most thermally sealed polymer films exhibit contact angles in the range of approximately 62° to 81°, suggesting that the thermal sealing process does not significantly affect the wettability of these materials. This range is typical for polymer surfaces with moderate hydrophobicity. In contrast, the compressed hydrophobic nanodiamond powder (DND-HB) shows a much higher contact angle—approximately 105.4°—indicating pronounced hydrophobicity and consequently much lower wettability compared with the polymer films, while the compressed hydrophilic nanodiamond powder (DND-HL) shows a contact angle of 50.2°, indicating clearly hydrophilic behavior. The red horizontal line in the graph indicates the reference contact angle value, exceeded only by nanodiamond, highlighting its exceptional hydrophobic properties and the DND-HB-doped films. The presence of error bars in the graph reflects experimental variability and measurement repeatability; the relatively low dispersion in the welded film group confirms the reliability of the results.

Figure 4.

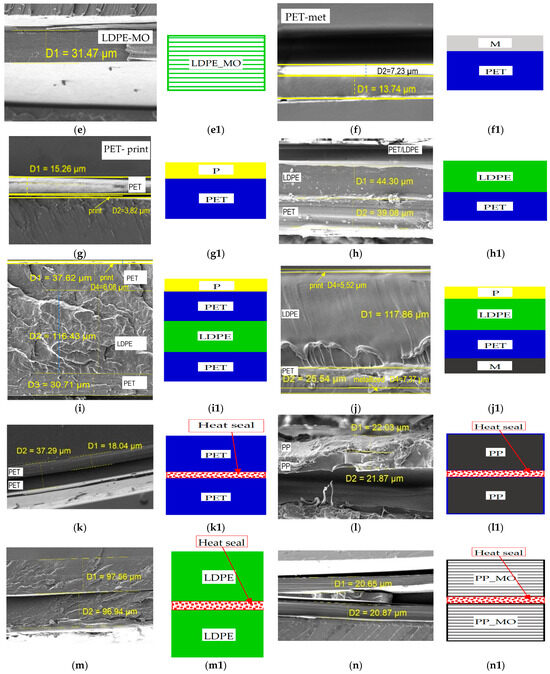

Cross-sectional surfaces of the examined polymer packaging films and their sealed joints, as determined by SEM imaging: (a) Monolayer film consisting of non-oriented poly(ethylene terephthalate); (b) Monolayer film consisting of non-oriented polypropylene; (c) Monolayer film consisting of non-oriented low-density polyethylene; (d) Monolayer film composed of polypropylene mechanically oriented in one direction; (e) Monolayer film composed of low-density polyethylene mechanically oriented in one direction; (f) Monolayer film consisting of non-oriented poly(ethylene terephthalate), with aluminum surface metallized; (g) Monolayer film consisting of non-oriented poly(ethylene terephthalate), with surface printed; (h) Multilayer film consisting of non-oriented poly(ethylene terephthalate) and non-oriented low-density polyethylene; (i) Multilayer film consisting of non-oriented poly(ethylene terephthalate), non-oriented polyethylene low-density and non-oriented poly(ethylene terephthalate), with surface printed; (j) Multilayer film consisting of metallized non-oriented poly(ethylene terephthalate) and non-oriented polyethylene low-density, with surface printed; (k) Heat-sealed joint of a monolayer film composed of non-oriented poly(ethylene terephthalate); (l) Heat-sealed joint of a monolayer film composed of non-oriented polypropylene; (m) Heat-sealed joint of a monolayer film composed of non-oriented low-density polyethylene; (n) Heat-sealed joint of a monolayer film composed of uniaxial oriented polypropylene; (o) Heat-sealed joint of a monolayer film composed of low-density polyethylene mechanically oriented in one direction; (p) Heat-sealed joint of a monolayer film composed of non-oriented poly(ethylene terephthalate) with a metallized surface; (q) Heat-sealed joint of a monolayer film composed of non-oriented poly(ethylene terephthalate) with a printed surface; (r) Multilayer film composed of non-oriented poly(ethylene terephthalate) and non-oriented low-density polyethylene; (s) Multilayer film composed of non-oriented poly(ethylene terephthalate) and non-oriented low-density polyethylene with a printed surface; (t) Heat-sealed joint of a multilayer film composed of non-oriented poly(ethylene terephthalate) and non-oriented low-density polyethylene with a metallized and printed surface; (a) ÷ (t) and (a1) ÷ (t1) Proposed structural schematics of the investigated mono- and multilayer films before and after heat sealing, respectively; applied notations; P—printed; M—metallized.

The differences in static contact angle values observed between the samples arise primarily from variations in surface free energy, micro- and nanoscale roughness, and the chemical composition of the outermost surface layer. These parameters govern the interactions at the solid–liquid interface in accordance with classical wetting theories (Young, Wenzel, Cassie–Baxter). The thermal sealing process, although involving elevated temperature and short-term softening of the material, does not induce substantial modifications in these characteristics; any potential changes in topography (microscale smoothing or local reflow) or surface chemistry (e.g., slight oxidation) remain too minor to significantly influence the macroscopic wetting behaviour.

In contrast, nanodiamond powders exhibit markedly different characteristics. The hydrophobic nanodiamond powder shows an exceptionally high contact angle, which reflects low surface energy and limited adhesive interactions with polar liquids. Its high roughness and hierarchical agglomerate structure favour a wetting regime consistent with the Cassie–Baxter model, where air entrapment within microcavities further increases the apparent contact angle. Such wetting behaviour is particularly relevant for applications requiring reduced adhesion, limited wettability, enhanced dirt-repellence, or controlled interfacial interactions, including protective coatings, anti-adhesive materials, and composite interfaces where hydrophobic additives can reduce moisture migration.

In contrast, the hydrophilic nanodiamond powder exhibits a markedly lower contact angle, indicating strong affinity for polar liquids. This behaviour results from the presence of oxygen-containing functional groups—such as –OH and –COOH—which increase surface energy and promote hydrogen bonding with water. Under conditions of high surface roughness, this behaviour conforms to a Wenzel-type regime, which amplifies the intrinsic hydrophilicity of the material.

These properties have important implications for applications, particularly in:

- Polymer composites, where hydrophilic nanodiamonds can enhance compatibility with polar matrices (e.g., some copolymers or biodegradable polymers), improve dispersion, strengthen interfacial adhesion, and modify thermal transport;

- Adsorptive materials and membranes, where improved wettability supports water transport and facilitates chemical functionalization;

- Bioactive coatings and biomaterials, where hydrophilicity can enhance biocompatibility, enable immobilization of bioactive molecules, and improve aqueous stability;

- Antibacterial and antiviral systems, in which strong wetting supports controlled moisture sorption and sustained contact with microorganisms, influencing inactivation efficiency.

In summary, the comparison of nanodiamonds with distinct surface chemistries clearly demonstrates that surface functionalization decisively governs their interfacial behaviour and thereby determines their suitability for specific applications. This makes the engineered surface properties of nanodiamonds a critical factor in designing advanced nanodiamond-based composites and coatings.

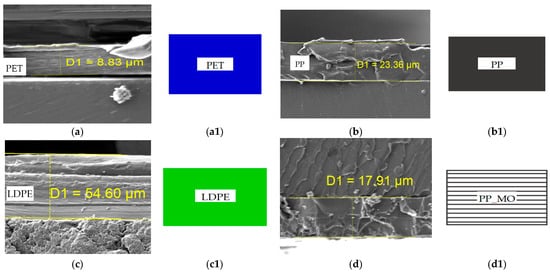

3.2. SEM Analysis of Cross-Sections of Selected Polymer Packaging Films

Figure 4 presents scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of cross-sections of packaging films before and after heat sealing, performed to assess changes in layer structure and the integrity of sealed joints.

Cross-sectional images obtained via SEM microscopy (Figure 4a–t) provide essential insights into the layer morphology and interfacial quality of twenty different polymer films, including monolayers, composites, and heat-sealed regions. Samples of pure PET (Figure 4a,k) and LDPE (Figure 4c,m) exhibit smooth, defect-free cross-sections with thicknesses of approximately g = 9–55 µm and g = 55–195 µm, respectively, indicating a stable extrusion process. Non-oriented PP (Figure 4b,l) shows a slightly rougher fracture surface, characteristic of unmodified polyolefins.

Oriented films such as LDPE_MO (Figure 4e,o) and PP_MO (Figure 4d,n) display parallel fibrillar structures aligned in the stretching direction. Orientation leads to a reduction in film thickness by approximately 15%–25% compared to non-oriented samples, enhancing tensile strength along the orientation axis at the expense of transverse strength.

In PET/LDPE samples (Figure 4h,r) and multilayer heat-sealed laminates (Figure 4p–s), the sealing zones exhibit localized flattening (g = 5–15 µm thick) and interpenetration of polymer chains. This smoothed morphology indicates effective polymer diffusion and strong interfacial bonding without signs of interfacial cracking, confirming the appropriate selection of sealing temperature and pressure.

Aluminum-coated films (Figure 4f,j,p,t) contain a metallic layer of a thickness of g = 0.1–0.2 µm, which partially delaminates and cracks in the sealing zones. This can negatively impact the film’s barrier properties against gases and moisture. To mitigate such defects, adjustments to sealing temperature or the use of adhesive tie layers are recommended.

Samples with toner-printed layers (Figure 4g–j,q–t) display irregular surface coatings of up to ~g = 5 µm in thickness. Increased flattening and localized cracking of the toner layer are observed in areas where the print overlaps with the sealing zone (Figure 4s,t). This suggests that printed regions should be excluded from critical sealing paths.

The thickest laminates are found in metallized and multilayer samples (I: g = 190 µm and J: g = 156 µm), while the thinnest are monolayer PET (Figure 4a: g = 9 µm), PP, and LDPE films (Figure 4b,c: ~g = 23–55 µm). Clear and well-defined interfaces between polymer layers indicate minimal migration of additives and high compositional stability, which is crucial for maintaining barrier and mechanical properties over time.

Mechanical orientation improves tensile strength in the longitudinal direction, but requires precise thickness control. Thermal sealing provides robust interfacial bonding, but must be optimized to avoid delamination of metallic layers. Printed graphics do not compromise the integrity of base layers, but should be positioned away from the sealing zones to ensure consistent sealing performance.

Microstructural analysis offers a solid foundation for optimizing processing parameters and material formulations in the advanced production of multilayer polymer films.

3.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Images of Detonation Nanodiamond Powder

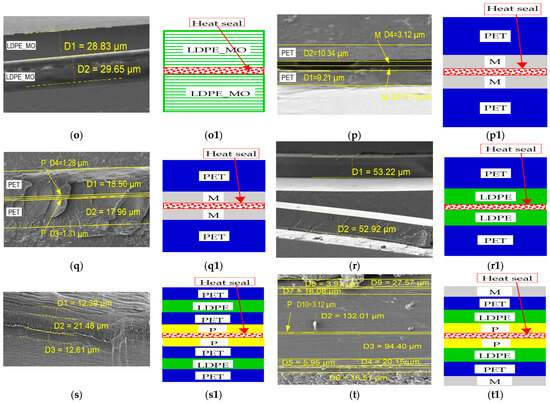

Figure 5 presents Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) images of detonation nanodiamond (DND) powder. The SEM analysis was performed to evaluate the morphological characteristics of the nanodiamond particles, including their size distribution, agglomeration behavior, and surface roughness. Understanding these parameters is essential for explaining potential interactions between nanodiamonds and polymer matrices when used as functional additives.

Figure 5.

SEM images of nanodiamond powder at magnifications of (a) 20,000× and (b) 100,000×.

The microstructural analysis reveals that DND particles are typically quasi-spherical and tend to form clusters as a result of strong van der Waals forces and surface energy effects. Their primary particle size is within the nanometer range (typically <10 nm), but visible aggregates can range up to several hundred nanometers in diameter. The high surface area and surface activity of DNDs may play a critical role in modifying the surface energy and wettability of polymer films, which correlates with the changes in contact angle observed in this study.

Moreover, surface roughness at nanoscale, as seen in the SEM images, may contribute to increased hydrophobicity of the films, consistent with wetting models such as the Cassie–Baxter theory. These features suggest that DNDs can enhance barrier properties and influence the interfacial behavior of multilayer structures or surface-modified packaging films.

The presence of agglomerates is disadvantageous because when nanodiamonds are added to the polymer matrix, these clusters can cause structural defects and damage the base film. Therefore, the SEM results will be utilized to develop effective deagglomeration methods aimed at obtaining a uniform powder composed of well-dispersed, individual particles. Such a homogeneous nanodiamond powder is expected to have a beneficial impact on the mechanical, physicochemical, and barrier properties of polymer materials.

Thus, SEM characterization of nanodiamond powder provides fundamental insights into their structure–property relationships, supporting their proposed role as multifunctional additives in high-performance polymeric packaging materials.

Two SEM images are presented, illustrating the microstructure of nanodiamond powder. Both images reveal surface structural details of diamond nanoparticles at high magnifications (left: 20,000×; right: 100,000×). The scale bars are intentionally labeled in micrometers for the first image and nanometers for the second to demonstrate that the nanodiamond powder, while meeting the definition of a nanomaterial (individual grain size: 30 nm), forms smaller or larger agglomerates. This agglomeration arises from the 3D diamond structure, the presence of free bonds on its surface, and the resulting exceptionally high surface area of the nanodiamond.

The agglomerates visible in the images exhibit an irregular, characteristic structure that influences their physical and chemical properties, such as thermal conductivity, hardness, and interactions with other materials. The SEM images further highlight the diversity and complexity of the surface morphology of the nanoparticles. The pronounced density and irregularity of shapes suggest that nanodiamonds possess a large specific surface area, making them highly effective in applications that require elevated surface reactivity. Additionally, nanodiamonds exhibit unique mechanical and chemical properties—they are extremely hard and wear-resistant.

3.4. Evaluation of Antimicrobial Properties Against Escherichia coli

This section presents the results of an antimicrobial activity test conducted using Escherichia coli (EC) as the model Gram-negative bacterium. The experiment was carried out in accordance with ISO 22196:2011 [47], which sets out a standard method for evaluating the antibacterial activity of plastic and non-porous surfaces.

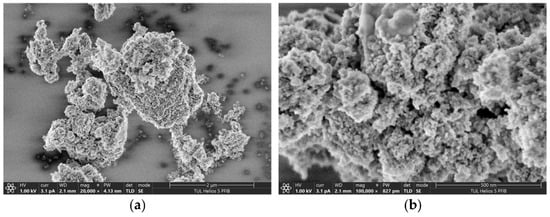

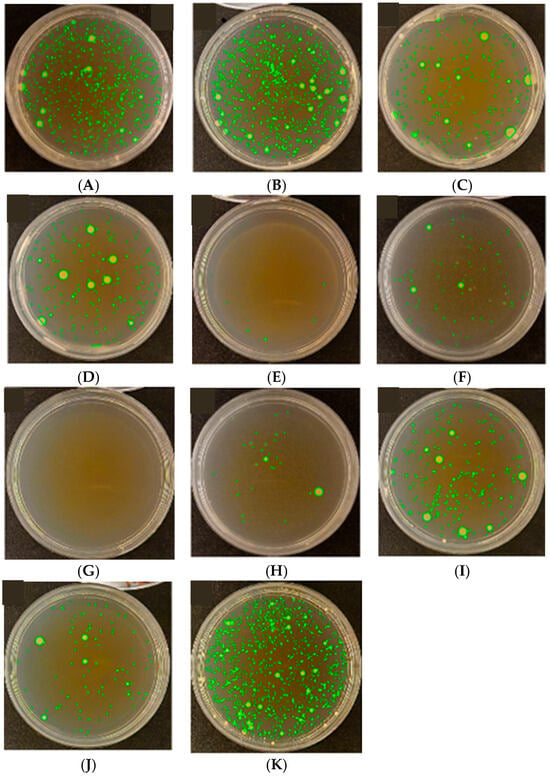

The test aimed to assess the ability of selected mono- and multilayer polymer films to inhibit bacterial growth after direct contact. Figure 6 provides photographic documentation of the resulting colony-forming units (CFU) that developed on Petri dishes after incubation. The number and distribution of bacterial colonies reflect the antimicrobial performance of the tested surfaces and allow for a comparative evaluation of samples.

Figure 6.

Results of antibacterial activity assessment against E. coli based on colony-forming unit (CFU) counts on Petri dishes, according to ISO 22196:2011 [47]. (A) PET; (B) PP; (C) LDPE; (D) PP_MO (Cast); (E) LDPE_MO (Cast); (F) PET-met (Al); (G) PET-print; (H) PET/LDPE; (I) PET/LDPE/PET-print; (J) met (Al)-PET/LDPE-print; (K) SiO2.

Petri dishes labeled A through K present the results of Escherichia coli cultivation following the incubation of samples made from various packaging materials. The green fluorescence observed in the form of colonies (CFU—colony-forming units) indicates bacterial presence and metabolic activity. The number and distribution of colonies enable both quantitative and qualitative assessment of the antimicrobial properties of the tested surfaces.

A high number of bacterial colonies was observed in the samples labeled B, D, and A, indicating a lack of significant antibacterial activity. These materials did not effectively reduce the survival or proliferation of microorganisms, which may be due to the low surface energy, absence of active coatings, or lack of biocidal substances.

Conversely, dishes C, J, E, and H showed a noticeably lower number of colonies, suggesting moderate antimicrobial effectiveness. This effect might result from the presence of functional layers such as printed surfaces, barrier additives, or differences in surface structure that can to some extent limit bacterial adhesion and growth.

The lowest CFU values were recorded for samples G, F, and I, indicating the high effectiveness of these materials in inhibiting the growth of E. coli. Such an outcome might be linked to the use of printed layers, biocidal additives, or specific physicochemical surface properties—such as increased hydrophobicity or nanoscale roughness—which hinder bacterial attachment and colonization.

The control sample labeled K, which contains a silicon dioxide (SiO2) coating, exhibited intermediate antimicrobial activity—the number of colonies was lower than in the non-active samples, but higher than in the most effective ones. This might be due to the presence of a physical barrier that limits microbial access to the surface while lacking intrinsic chemical antimicrobial activity.

In conclusion, the analysis of colony-forming units (CFU) facilitates an evaluation of the antimicrobial efficacy of the materials tested. The results indicate that some of the films—particularly those with printed or functional surface layers—might exhibit inhibitory effects on E. coli growth, making them promising candidates for use in active packaging systems designed for microbiologically sensitive products. Further research should focus on elucidating the mechanisms of action of these materials and assessing their effectiveness against other pathogenic microorganisms.

3.5. Evaluation of Antimicrobial Properties Against Micrococcus luteus

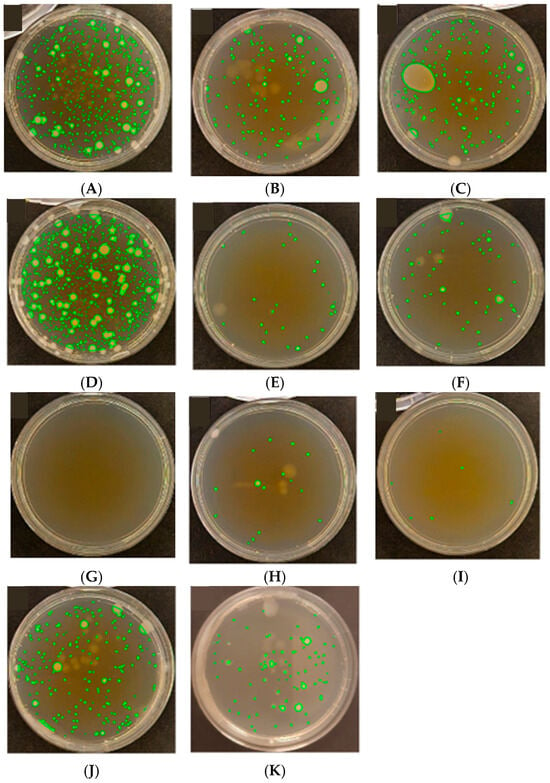

Antimicrobial activity was evaluated according to the methodology described in Chapter 3, Materials and Methods. Basic statistical analyses were performed, including the calculation of mean values and standard deviations. Figure 7 presents photographic documentation of Petri dishes, illustrating colony-forming units (CFU) obtained as a result of an antimicrobial test conducted according to the ISO standard, using Micrococcus luteus (ML) bacterial cells.

Figure 7.

Results of assessment of antibacterial activity against Micrococcus luteus based on colony-forming unit (CFU) counts according to ISO 22196:2011. (A) PET; (B) PP; (C) LDPE; (D) PP_MO (Cast); (E) LDPE_MO (Cast); (F) PET-met (Al); (G) PET-print; (H) PET/LDPE; (I) PET/LDPE/PET-print; (J) met (Al)-PET/LDPE-print; (K) SiO2.

Petri dishes labeled A to K represent various tested surfaces of materials intended for different types of packaging films. Based on the observation of green fluorescence, the resulting bacterial colonies (CFU—colony-forming units) can be clearly identified and quantitatively assessed. The number and spatial distribution of colonies serve as an indicator of the antimicrobial effectiveness of the tested samples.

Dishes D, A, B, and K showed a high level of bacterial colonization, implying that the tested surfaces showed low or no antibacterial activity. The presence of numerous colonies indicates that these materials did not significantly inhibit bacterial growth and survival, which might be due to low surface energy, a lack of active biocidal coatings, or an absence of antimicrobial substances.

The samples labeled G, F, H, and E exhibited a minimal number of bacterial colonies, indicating high antimicrobial efficacy. This effect might result from the use of functional coatings or additives with biocidal activity, as well as physicochemical surface properties that hinder microbial adhesion and proliferation.

Dishes I, C, and J showed a moderate level of colonization, suggesting partial inhibition of bacterial growth and indicating the medium antimicrobial effectiveness of these materials. This outcome might be due to the limited activity of growth inhibitors, differences in surface microstructure, or presence of barrier layers with restricted efficiency.

The variability in colony-forming unit (CFU) counts among the tested samples highlights the diversity of antimicrobial properties in the materials studied. This analysis provides essential information about the potential applications of these surfaces in active packaging systems, medicine, or other fields where microbial growth control is critical.

The antimicrobial studies conducted are crucial for evaluating the functionality of packaging materials, particularly in the context of active food-packaging systems and other areas requiring microbiological control, such as the food industry, medicine, or pharmaceuticals. Precise determination of bacterial growth inhibition effectiveness makes it possible to select suitable antimicrobial materials, directly impacting on product safety and shelf life.

As for research on films modified with detonation nanodiamonds (DND), the data obtained serve as a reference for comparing the biological properties of base materials and their modified counterparts. Nanodiamonds, due to their unique physicochemical properties, such as high specific surface area, elevated surface activity, and the ability to form biocidal layers, can significantly enhance the antimicrobial properties of films.

A comparative analysis of CFU counts makes it possible to evaluate the effectiveness of nanodiamonds as a modifying additive, indicating potential mechanisms of bacterial-growth inhibition such as increased hydrophobicity, mechanical nanoscale action, or possible release of active ions. This facilitates the optimization of the modification process and the selection of optimal technological parameters to ensure effective microbiological protection and preservation of the mechanical and barrier properties of the films.

Using DND-enhanced films in active-packaging production might help extend the shelf life of food products, reduce the use of chemical preservatives, and improve microbiological safety. Moreover, the results of these studies can be used as a base for further experiments about the effects of nanodiamonds on other pathogenic microorganisms and for the development of new packaging materials with advanced functional properties.

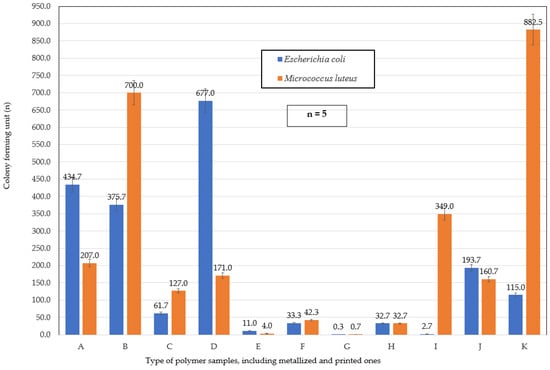

Figure 8 presents the quantitative results of an assessment of colony-forming units (CFU) for two bacterial species—Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Micrococcus luteus (M. luteus)—following their exposure to various tested surfaces. The evaluation was conducted in accordance with the standardized ISO methodology, which ensures the reproducibility and reliability of measurements of antimicrobial activity. The figure illustrates differences in bacterial survival and growth inhibition among the tested materials, providing insights into their antimicrobial effectiveness. This data is crucial for identifying materials with potential applications in active-packaging systems and other areas in which microbial control is essential.

Figure 8.

Results of bacterial colony-forming unit (CFU) counts in agar determined using the ISO method for Escherichia coli (EC) and Micrococcus luteus (ML) bacterial cells.

The CFU results obtained following bacterial contact with various packaging-material surfaces reveal significant differences in antimicrobial effectiveness among the analyzed samples. This study was conducted according to the ISO methodology, ensuring the high comparability and reliability of the data.

The highest CFU values—both for Escherichia coli and Micrococcus luteus—were recorded on PP, PP_MO, and SiO2 surfaces, indicating the complete lack of antimicrobial activity of these materials. In particular, the control film coated with a silicon dioxide (SiO2) layer exhibited the highest total number of M. luteus colonies, suggesting that despite the potential physical barrier, this surface demonstrated no bactericidal or bacteriostatic effects. It can be assumed that the lack of chemical interactions with bacterial cells and the relatively smooth surface topography might promote adhesion and microbial proliferation.

A markedly different activity profile was observed for the LDPE_MO material, which almost completely inhibited the presence of both tested bacterial strains. Such high effectiveness might be associated with the unique physicochemical properties of this surface, including low surface energy, the possible presence of antimicrobial additives, or a microstructural texture that is unfavorable for bacterial colonization.

The PET and PET-printed surfaces exhibited moderate antimicrobial activity. For E. coli, the colony count was relatively low, whereas M. luteus showed a higher survival rate. This could indicate differences in the susceptibility of these bacterial species to surface characteristics—M. luteus, being a Gram-positive bacterium, might be more resistant to the environmental conditions presented by the films tested than the Gram-negative E. coli.

The surface configuration of met(Al)-PET/LDPE-printed exhibited a medium level of antimicrobial activity—CFU values were lower than those of inactive surfaces, but did not reach the levels observed for highly effective materials. It can be speculated that the presence of metallic layers might partially reduce bacterial growth, although not to a degree sufficient to classify the materials as biologically active.

Of all the samples tested—LDPE_MO aside—the highest antimicrobial effectiveness was demonstrated by PET-met(Al), PET/LDPE, and PET/LDPE/PET-printed films. In these cases, minimal colony formation was observed for both E. coli and M. luteus. This might be attributed to the use of functional printed coatings, differences in surface morphology, or the presence of biocidal compounds not explicitly disclosed in the layer composition.

It is noteworthy that M. luteus generally exhibited greater resistance to the materials tested than E. coli, suggesting its potential suitability as a reference strain for evaluating materials with enhanced antimicrobial properties.

The findings presented here provide valuable insights into the baseline properties of unmodified packaging materials and serve as a robust reference point for future studies on polymer modification, particularly studies involving detonation nanodiamonds (DND). Comparing CFU counts before and after modification will allow for precise determination of the impact of DNDs on antimicrobial performance, essential for the development of advanced active food-packaging systems and next-generation medical materials.

4. Discussion

To summarize, printed PET-based materials—particularly PET-print and PET/LDPE/PET-print—exhibited the highest antimicrobial activity against both bacterial strains. In contrast, surfaces such as SiO2, PP, and PP_MO proved ineffective and, in some cases, even promoted bacterial survival or proliferation, especially in E. coli. The findings clearly confirm that the incorporation of nanodiamonds (ND) into polymer film structures can substantially modify their physicochemical, mechanical, and microbiological characteristics.

Of particular relevance are the observations concerning variations in the contact angle, which serve as indicators of surface hydrophobicity or hydrophilicity. The obtained results indicate that the incorporation of detonational nanodiamonds (DND) can lead to diverse effects on the surface and functional properties of polymer films. These observations constitute a valuable starting point for further analyses on the use of nanodiamonds as functional additives capable of modifying the barrier, surface, and processing-related characteristics of advanced packaging films. Of particular importance are the differences observed between the DND-HB and DND-HL fractions, which exhibit distinct wetting behaviors that clearly confirm their divergent surface characteristics.

The compressed DND-HB powder exhibited a very high contact angle (105.4°), classifying it as a strongly hydrophobic material. This pronounced increase in the contact angle can be interpreted as the outcome of a synergy between two factors: (i) the specific surface chemistry of nanodiamonds, which limits their ability to form hydrogen bonds with water, and (ii) nanoscale roughness leading to a wetting regime described by the Cassie–Baxter model, where trapped air pockets enhance the apparent hydrophobicity of the material.

This behavior may directly translate into functional improvements in film performance. Introducing a highly hydrophobic phase may increase resistance to water vapor and gas diffusion, which is particularly desirable in applications involving packaging for products sensitive to moisture, oxidation, or the migration of volatile compounds. Preliminary observations related to oxygen permeability and barrier properties suggest that such additives may effectively increase the tortuosity of diffusion pathways, although this requires comprehensive confirmation through detailed studies that consider the effects of dispersion, filler loading, and multilayer film architecture.