Abstract

This research systematically investigates the influence of multi-microalloying with Sn, Mn, Er, and Zr on the homogenized microstructure, aging behavior, and mechanical properties of a 6082 Al-Mg-Si alloy. The optimization of the homogenization treatment for the alloy was based on isochronal aging curves and conductivity measurements. The results show that the addition of Mn, Er, and Zr can precipitate thermally stable Al(Fe,Mn)Si dispersoids and Al(Er,Zr) dispersoids. The three-stage homogenization treatment resulted in the precipitation of more heat-resistant dispersoids, thereby achieving the best thermal stability. During direct artificial aging, the initial hardening rate of the Mn-containing alloy was slightly delayed, but its peak hardness was significantly increased. This is due to the dispersoids offering additional heterogeneous nucleation sites for the strengthening precipitates. Meanwhile, the Sn atoms release their trapped vacancies at the aging temperature, thereby promoting atomic diffusion. However, short-term natural aging before artificial aging accelerated the early-stage aging response of the Sn-containing alloy but resulted in a reduced peak hardness. Notably, the co-microalloying with Mn and Sn led to a higher peak hardness during direct artificial aging, while it caused a more significant hardness loss when a natural aging preceded artificial aging, revealing a distinct synergistic negative effect. The reason for the negative synergy effect might be related to the weakened ability of Sn to release vacancies after natural aging. This study clarifies the process dependence of microalloying effects, providing a theoretical basis for optimizing aluminum alloy properties through the synergistic design of composition and processing routes.

1. Introduction

6xxx series aluminum alloys are age-harding alloys employed in transportation, construction, and consumer goods, owing to a combination of favorable corrosion resistance and fatigue performance, supplemented by excellent weldability and formability [1,2,3]. The primary route to high strength in alloys is the T6 temper, which involves solution heat treatment, quenching, and artificial aging. When aged at temperatures between 160 and 200 °C, a high density of nano-sized needle-shaped β″ precipitates (Mg5Si6) form in the matrix. These precipitates effectively impede dislocation motion and serve as the primary strengthening phase. The generally accepted precipitation sequence in Al-Mg-Si alloys is: supersaturated solid solution (SSSS) → solute clusters → GP zones → β″ phase (Mg5Si6) → β′ phase (Mg9Si5) and its variants → equilibrium β phase (Mg2Si) [4,5,6].

In recent years, microalloying (e.g., with Mn, Cu, Zn, or rare earth elements) has emerged as an effective strategy for tailoring precipitation behavior and optimizing overall properties. The addition of Mn does not form complex precipitates but promotes Al(Mn,Fe)Si phase formation, with Si remaining present. Previous studies [7,8] et al. found that Al(Mn,Fe)Si phases begin to precipitate around 350 °C, reach an optimal state at 400 °C, and start to coarsen above 450 °C. A fine dispersion of Al(MnFe)Si compounds at high density is achievable. This microstructural feature effectively enhances high-temperature strength, inhibits grain growth during hot rolling and annealing, and increases recrystallization resistance. Simultaneously, these dispersed Al(FeMn)Si compounds [9,10,11,12] also pin dislocations, leading to an increase in the alloy’s hot deformation activation energy.

Sn has a relatively large atomic radius and exhibits very low solubility in aluminum, with a maximum solubility of only about 0.1 wt.% even at 600 °C [13]. However, it possesses a high vacancy binding energy. According to first-principles calculations, the binding energy is strongest for the Sn-vacancy pair, at 0.24 eV, which is markedly higher than the values computed for Mg-vacancy (0.01 eV) or Si-vacancy (0.06 eV) pairs. Consequently, Sn atoms strongly tend to bind with vacancies, which can markedly influence the age-hardening behavior of aluminum alloys. Research on Sn in Al-Mg-Si alloys started relatively late, initially focused on improving machinability [13,14]. Adding 0.1% Sn could suppress natural aging and enhance artificial aging response [15]. Adjusting alloy composition and solution heat treatment temperature can increase the amount of Sn dissolved in the matrix, ultimately achieving suppression of natural age-hardening in Al-Mg-Si alloys for up to six months [16,17]. And in a peak-aged Al-Mg-Si alloy containing trace Sn at 250 °C, composite β′/β″ precipitates formed instead of distinct β′ precipitates, resulting in significant morphological refinement [18]. Sn can fundamentally alter the precipitation behavior of Si/clusters in Al-Mg-Si alloys. However, subsequent studies indicated that while Sn can slow down natural aging to some extent, it may adversely affect subsequent artificial aging behavior [19,20]. Researcher further revealed that Sn microalloying could accelerate the hardening rate during artificial aging after short-term natural aging (NA < 5 days), but this positive effect diminished with longer NA times [21,22]. This is related to Sn’s influence on the concentration of free vacancies and the size/composition of clusters formed during natural aging [23,24]. Apart from that, an Al-Mg-Si-Er-Zr alloy had a higher activation energy than a 6082 alloy, attributed to the formation of Al3(Er, Zr) nanoparticles which pin dislocations and subgrain boundaries, inhibiting recrystallization [25]. The precipitation evolution and coarsening resistance of Er and Zr microalloyed Al at 400 °C were revealed [26]. The hardness from the co-addition of Zr and Er was much higher than the sum of their individual contributions. Precipitates in Al-0.06Zr-0.03Er still exhibited excellent coarsening resistance at 400 °C, with Er promoting the decomposition of Al-Zr and Zr inhibiting precipitate coarsening [27,28].

However, existing research has predominantly focused on the mechanisms of individual microalloying elements. When multiple elements (e.g., Sn, Mn, Er, Zr) are present concurrently, complex interactions may arise, and their combined effects across critical stages—such as homogenization, natural aging, and artificial aging after natural aging—remain unclear. Specifically, the key mechanisms—through which the multi-component alloying influences dispersoid precipitation in the homogenization process, alters aging kinetics, and synergistically controls the resultant mechanical behavior—remain elusive. Accordingly, this study is designed to elucidate the synergistic influences and fundamental principles behind the Sn, Mn, Er, and Zr multi-microalloying, focusing on their impact on microstructural evolution throughout homogenization and aging treatments, and the consequent effects on the alloy’s mechanical properties.

2. Materials and Methods

The experimental alloys used in this study were prepared by conventional melting and casting. High-purity aluminum (99.9%), tin (99.9%), and magnesium (99.9%), along with Al-10Mn, Al-20Si, Al-6Er, and Al-10Zr master alloys, were melted in a crucible at 780 ± 10 °C. After reaching the target temperature, the melt was held for 2 h. Magnesium was added 10 min prior to casting. To compensate for burning loss during melting, an extra 10% of the calculated Mg weight was added. The melt was thoroughly stirred and then poured into a steel mold to produce an ingot with dimensions of 180 mm × 80 mm × 30 mm and a weight of approximately 1500 g. The chemical compositions of alloys were determined by means of inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES) and are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Chemical compositions of experimental alloys (wt.%).

Vickers hardness was measured using an HDX-1000TM/LCD microhardness tester (Shanghai Guangmi Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) with a load of 100 g and a dwell time of 10 s. Prior to testing, the sample surface was ground smooth with 2000-grit sandpaper to ensure flat and parallel surfaces. A diamond indenter was pressed into the surface, and the hardness value was derived from the diagonal length of the resulting impression. Eight random measurements were taken on each sample, and the average value was reported.

Electrical conductivity was evaluated using a Sigmatest 2.039 portable conductivity meter. Measurements were performed at frequencies of 60, 120, 240, 480, and 960 Hz, with an accuracy of ±0.5% and a detection range of 1%–112% IACS (International Annealed Copper Standard). The sample surface was polished with 2000-grit sandpaper, and tests were conducted at room temperature. Five measurements were taken per specimen and averaged.

A Gemini SEM 300 scanning electron microscope was employed to examine the microstructure of the alloys after homogenization heat treatment. Sample preparation involved sequential grinding with 400-, 800-, and 2000-grit sandpaper, followed by mechanical polishing until a scratch-free surface was obtained. Microstructural observations were carried out using backscattered electron imaging.

TEM analysis was performed using FEI Talos F200X-G2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Titan-Themis microscopes, operating at accelerating voltages up to 200 kV. Specimen preparation began by grinding 0.5 mm-thick slices to approximately 100 μm on 800-grit sandpaper, followed by punching into 3 mm diameter disks. These disks were further ground to 50–60 μm and subsequently thinned by twin-jet electropolishing. The electrolyte consisted of 30 vol% HNO3 and 70 vol% CH3OH. Electropolishing was conducted at a current of 80–90 mA and a voltage of about 12 V, with liquid nitrogen continuously supplied to maintain the electrolyte temperature between −25 °C and −30 °C. The final specimens contained electron-transparent regions with thicknesses ranging from 50 to 100 nm, suitable for TEM observation.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Investigation of the Homogenization Treatment for the Alloys

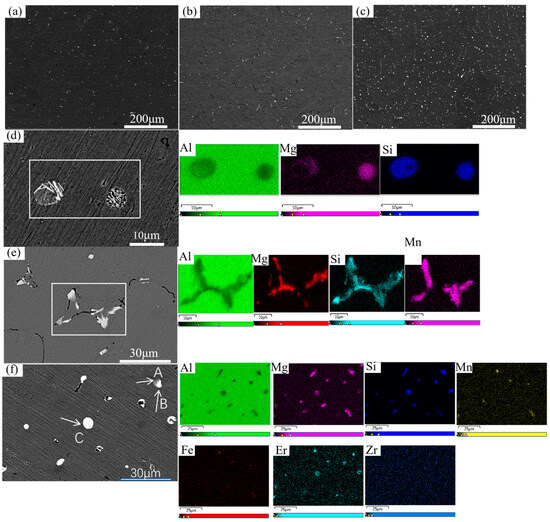

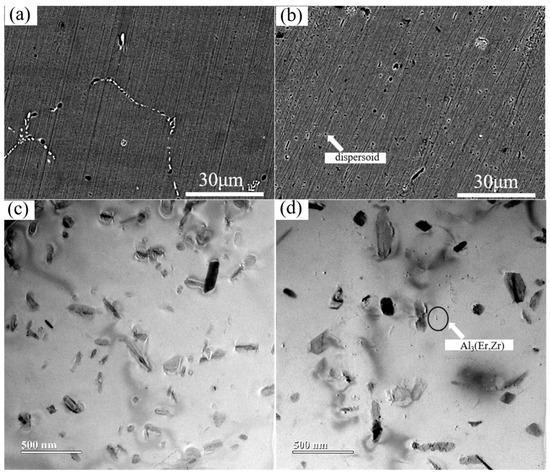

Figure 1 presents the as-cast SEM microstructures of the three alloys with varying compositions. In the base Al-Mg-Si alloy (Figure 1a), the microstructure is characterized by an α-Al matrix with a minor fraction of primary phases segregated in the interdendritic regions. These phases are identified as primary Mg2Si along with a small amount of bright white Fe-containing constituents. Upon the addition of 0.5% Mn (Figure 1b), a significant microstructural evolution is observed: the population of primary phases increases substantially, and their morphology evolves from a skeletal/needle-like form into fine, uniformly dispersed particles. These particles are predominantly identified as the α-Al(Fe,Mn)Si phase. This transformation demonstrates that Mn addition effectively enhances the nucleation of Fe-containing phases and facilitates the conversion of the detrimental needle-like β-AlFeSi phase into a more globular α-phase morphology. With the further incorporation of both Er and Zr (Figure 1c), additional refinement of the as-cast microstructure is achieved, as evidenced by the corresponding SEM images along with elemental mapping and point analysis presented in Table 2. The rare earth element Er and Zr exhibit a strong tendency for cooperative segregation, leading to their co-enrichment in specific microstructural regions.

Figure 1.

SEM images of as-cast alloys 1# (a,d) 3# (b,e) 5# (c,f).

Table 2.

Chemical composition (at.%) of secondary phases in the as-cast microstructure.

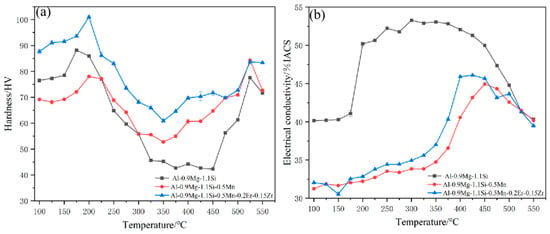

Figure 2a,b present the isochronal hardness and electrical conductivity curves for the three as-cast alloys: #1 (base), #3 (Mn-containing), and #5 (containing Mn, Er, and Zr). In the low-temperature range (100–200 °C), the hardness of all alloys initially increases. This trend reflects the typical low-temperature aging behavior of Al-Mg-Si alloys, where in Mg and Si atoms precipitate from the supersaturated solid solution to form Guinier-Preston (GP) zones and subsequently the metastable β″-Mg5Si6 phase. This coherent precipitate provides significant precipitation strengthening, accounting for the observed hardness increase. As the isochronal annealing temperature exceeds 250 °C, however, this metastable phase rapidly coarsens and transforms into stable phases, diminishing its strengthening contribution. Consequently, the hardness curves peak and then begin to decline. In contrast, alloys #3 and #5, containing additions of Mn, Er, and Zr, retain higher hardness levels at elevated temperatures. This enhancement is primarily ascribed to the precipitation of thermally stable second phases during heating [26,27,28]. Specifically, Mn promotes the formation of α-Al(Mn,Fe)Si phases. These finely dispersed particles effectively pin dislocations, thereby conferring improved high-temperature strength and thermal stability. The initial increase in electrical conductivity with temperature is attributed to a substantial decrease in solute concentration within the aluminum matrix. Beyond a critical temperature, however, conductivity decreases, coinciding with abnormal grain growth and the extensive dissolution of primary interdendritic phases such as Mg2Si. The addition of Mn elevates this critical transition temperature significantly, primarily through the formation of thermally stable nanoscale dispersoids (e.g., Al6Mn). These dispersoids influence conductivity via a dual mechanism: firstly, by acting as additional electron scattering centers; secondly, and more critically, by strongly pinning grain boundaries and dislocations, which suppresses recovery and inhibits grain boundary migration.

Figure 2.

Isochronal Hardness and Electrical Conductivity Curves for various alloys (a) the isochronal hardness (b) electrical conductivity curves.

The variation in hardness for the alloys during isothermal annealing at 375 °C is plotted in Figure 3, subsequent to a stepwise pretreatment at 250 °C/3 h + 300 °C/12 h. The plot reveals that alloy #3 (with Mn)retains elevated hardness relative to the base alloy (#1) for the entire duration, indicating its enhanced stability at high temperature. During isothermal treatment at 375 °C, the base alloy #1 shows a continuous hardness drop, primarily as a result of the dissolution and coarsening of the metastable β′-Mg2Si phase that precipitated in the prior 300 °C pretreatment. Consequently, the strengthening contribution from this phase gradually diminishes. In contrast, the hardness curve of alloy #3 shows a relatively flat plateau. This is due to the addition of Mn, which introduces thermally stable α-Al(Fe,Mn)Si dispersoids. At 375 °C, these dispersoids not only remain stable but may also continue to precipitate, thereby effectively compensating for the strength loss caused by the degradation of the β′-Mg2Si phase and maintaining the overall hardness. Alloy#5 exhibits a different characteristic: its hardness first increases to a peak and then decreases slowly. This behavior is explained by the enhanced diffusivity of Er and Zr atoms at this temperature, leading to the formation of a high density of coherent nano-scale Al3(Er,Zr) precipitates.

Figure 3.

Following 250 °C/3 h + 300 °C/3 h Pretreatment (a) Isothermal hardness curve at 375 °C (b) Isothermal electrical conductivity curve at 375 °C.

The evolution of electrical conductivity provides corroborating evidence for the aforementioned microstructural differences. Throughout the isothermal process, the base alloy #1 consistently exhibited the highest electrical conductivity. This indicates that its aluminum matrix is the purest. The primary reason is that during the 300 °C pretreatment and the initial stage at 375 °C, its main solute atoms (Mg, Si) have already precipitated extensively to form metastable strengthening phases (such as the β″ phase). As the isothermal treatment proceeds, these phases coarsen or transform rather than dissolve back into the matrix in large quantities. Consequently, the solute concentration in the matrix remains at a low level, resulting in weak electron scattering and, thus, high electrical conductivity. Alloy #3 (with Mn addition) showed relatively lower electrical conductivity, indicating that its matrix purity is inferior to that of alloy #1. This is attributed to the formation of α-Al(Fe,Mn)Si dispersoids induced by the Mn addition. This phase has a complex composition and is semi-coherent with the matrix. Its formation process may require additional solute atoms (such as Si) to segregate at the interfaces to reduce the interfacial energy. This interfacial solute segregation effect prevents the solute concentration in the matrix, particularly in regions near the phase boundaries, from reaching the minimum level, thereby enhancing electron scattering. A key finding is that alloy #5 (with Mn, Er, and Zr additions) exhibited higher electrical conductivity than alloy #3. This reveals the unique precipitation behavior of the coherent Al3(Er,Zr) nanoprecipitates. This phase has a well-defined stoichiometry and extremely low coherent interfacial energy. Its formation efficiently and specifically “traps” and immobilizes Zr and Er atoms in the matrix, while causing almost no additional solute segregation at the interfaces. This “clean” and efficient precipitation mechanism results in a more thorough purification of the aluminum matrix compared to alloy #3, leading to the observed higher electrical conductivity. Based on these findings, a homogenization treatment of 250 °C/3 h + 300 °C/12 h + 375 °C/12 h was ultimately selected for this study. This three-stage process is designed to promote the sufficient precipitation of both the α-Al(Mn,Fe)Si and Al3(Er,Zr) phases.

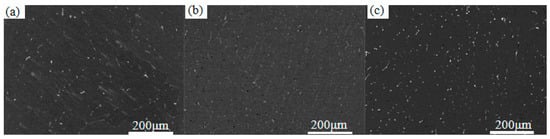

Figure 4 presents comparative SEM backscattered electron (BSE) images of the three experimental alloys after the stepwise homogenization treatment. Following the stepwise homogenization treatment at 250 °C/3 h + 300 °C/12 h + 375 °C/12 h (Figure 4a–c), the dendritic segregation is essentially eliminated, leading to a significant improvement in microstructural homogeneity. In the absence of Mn addition, no dispersoids are formed. Only a small amount of coarse Mg2Si, which may form during heating and holding, is distributed within the matrix.

Figure 4.

SEM images of homogenized state alloys (a–c) SEM of alloys #1, #3, and #5, respectively, after three steps homogenization treatment.

The homogenization treatment plays a pivotal role in microstructural engineering for the Mn-containing alloy #3, effectively inducing the precipitation of a high number density of thermally stable dispersoids. A significant microstructural evolution is observed, as illustrated in Figure 5b. The coarse and continuously networked α-Al(Fe,Mn)Si phase, characteristic of the as-cast condition, undergoes substantial fragmentation and spheroidization during heat treatment, transforming into a uniform distribution of fine, discrete particles. This refined and isolated particulate morphology, directly evidenced in Figure 5a, serves as definitive microstructural proof of the successful conversion of the detrimental intermetallic network into beneficial, thermally stable dispersoids. The efficacy of this refinement process is further confirmed at higher resolution, with the finely dispersed particles being distinctly resolvable in both scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Figure 5b) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Figure 5c,d) images. These refined α-Al(Fe,Mn)Si dispersoids act as potent obstacles to microstructural degradation at elevated temperatures. They strongly pin grain boundaries, thereby effectively inhibiting grain growth during prolonged thermal exposure. Simultaneously, they interact with dislocations, obstructing their motion and providing significant strengthening through the Orowan bypass mechanism. This dual pinning effect on both grain boundaries and dislocations constitutes the fundamental micro-mechanism responsible for the alloy’s enhanced thermal stability and resistance to softening. This stands in sharp contrast to the base alloy #1 (Figure 4a), which lacks such a dispersion of stable second-phase particles. The absence of effective pinning sites in alloy #1 results in weaker resistance to grain boundary migration and dislocation glide at high temperatures, which directly correlates with its inferior hardness retention, as observed in the isothermal annealing curves. Furthermore, the synergistic microalloying with Er and Zr introduces an additional category of strengthening particles. These elements precipitate to form nano-scale, coherent L12-ordered Al3(Er,Zr) dispersoids. These precipitates, which can be observed in Figure 5b, are exceptionally stable against coarsening due to their low interfacial energy and slow diffusion kinetics of the solute atoms. Their fine and homogeneous distribution within the matrix provides a potent source of strengthening, efficiently pinning dislocations and sub-grain boundaries. The concurrent presence of both α-Al(Fe,Mn)Si and Al3(Er,Zr) dispersoids creates a multi-scale barrier against microstructural instability, collectively imparting the alloy with excellent high-temperature strength and superior thermal stability, outperforming alloys modified with only a single microalloying addition [29,30].

Figure 5.

(a,b) SEM and (c) TEM of Alloy #3 after stepwise homogenization treatment. (d) TEM image of Alloy #5 after stepwise homogenization treatment.

3.2. Aging

3.2.1. Evolution of Hardness During Natural Aging

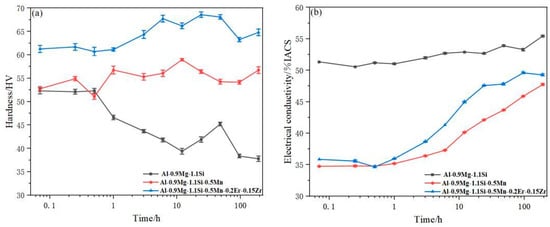

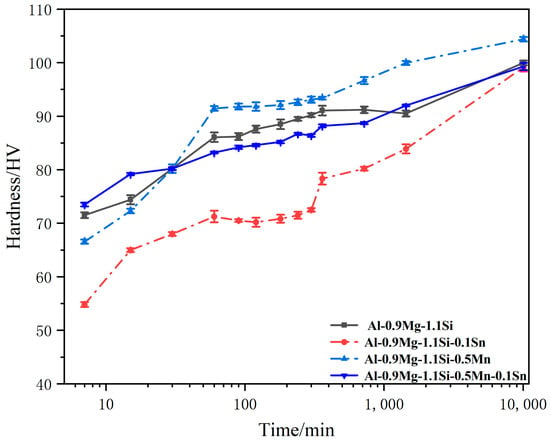

Figure 6 compares the natural aging hardness evolution of four alloys—base (#1), Sn-added (#2), Mn-added (#3), and Mn-Sn co-added (#4)—after they underwent solution treatment at 540 °C for 30 min. The curves are plotted using data points and error bars from repeated experimental tests.

Figure 6.

Evolution of hardness for the alloys during NA.

The natural aging kinetics differ markedly among the various alloys. The hardness curve of the Al-Mg-Si-Mn alloy demonstrates the strong accelerating effect of Mn, exhibiting both the highest initial hardness (66.56 HV at 7 min) and the highest final hardness (104.4 HV at 10,080 min). In contrast, the curve for the Al-Mg-Si-Sn alloy confirms the retarding effect of Sn, showing the lowest initial hardness (54.83 HV), a sluggish aging response, and a final hardness of 99.15 HV. The final hardness of the base alloy is 99.98 HV. It is noteworthy that the Al-Mg-Si-Mn-Sn alloy displays a relatively high initial hardness (73.5 HV), second only to the Mn-containing alloy, but its subsequent hardening rate slows down, resulting in a final hardness of 99.3 HV. This suggests that the coexistence of Mn and Sn may alter the singular clustering pathway.

In summary, Mn significantly promotes natural aging hardening [31], whereas Sn primarily exerts an inhibitory effect. When added in combination, their interaction likely complicates the hardening behavior, yielding a higher initial hardness at the expense of part of the rapid hardening capability provided by Mn alone.

3.2.2. Artificial Aging After Natural Aging

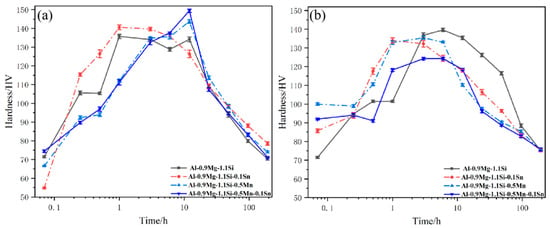

As depicted in Figure 7a, the alloys undergo direct artificial aging at 175 °C. The early-stage aging is characterized by a rapid hardness increase for all alloys, culminating in a peak near 12 h, followed by pronounced softening. This trend is a direct manifestation of the standard precipitation sequence in Al-Mg-Si alloys. The initial hardening is attributed to the rapid diffusion and clustering of Mg and Si solutes from the supersaturated solid solution, leading to the formation of GP zones. These zones serve as intermediates for the nucleation of the needle-shaped β″ phase. Peak hardness is reached when the β″ phase attains its optimal density and size for strengthening. The sharp decline thereafter signals over-aging, a process fundamentally driven by the loss of coherency in the β″ precipitates as they transform into the β′ (Mg9Si5) or the incoherent equilibrium β-Mg2Si phase. This microstructural change, alongside considerable precipitate coarsening, severely compromises their effectiveness as barriers to dislocation motion.

Figure 7.

Hardness curves of the alloys during aging at 175 °C (a) NA0d (b) NA1d.

For the Mn-added alloy, the initial hardening rate was slightly slower; however, its peak hardness was significantly increased. The dispersoids provide additional heterogeneous nucleation sites for the β″ phase. Heterogeneous nucleation effectively lowers the nucleation energy barrier for the β″ phase, resulting in a higher nucleation density and more uniform distribution within the matrix. This not only enhances the peak strength but may also lead to a more focused precipitate size distribution, thereby optimizing the strengthening effect.

The Sn-added alloy also exhibited an increase in peak hardness, but its mechanism differs from that of Mn, primarily based on vacancy control. Sn atoms possess an extremely high binding energy with vacancies. After solution treatment and quenching, Sn atoms rapidly capture a large number of excess vacancies, forming stable Sn-vacancy complexes. At the aging temperature of 175 °C, these complexes gradually decompose, releasing vacancies in a sustained and controlled manner. Vacancies are the primary medium for the diffusion of solute atoms (Mg, Si), significantly promoting the nucleation and early growth kinetics of the β″ phase. This leads to faster precipitation response and increased peak hardness.

Figure 7b shows the hardness evolution curves of the alloys during artificial aging following different durations of natural aging (NA1d). The results indicate that the Sn-added alloy #2 exhibited a faster initial hardening response during artificial aging but achieved a lower peak hardness compared to the base alloy without Sn #1. The accelerated initial response may be related to the release of vacancies by Sn atoms, promoting solute diffusion. The Mn-added alloy #3 showed a similar trend, with its peak hardness also lower than that of the base alloy, and the reduction was more pronounced compared to the direct aging path. Combined Addition Effect: The alloy with combined additions of Mn and Sn #4 experienced the most significant reduction in peak hardness during artificial aging after natural aging.

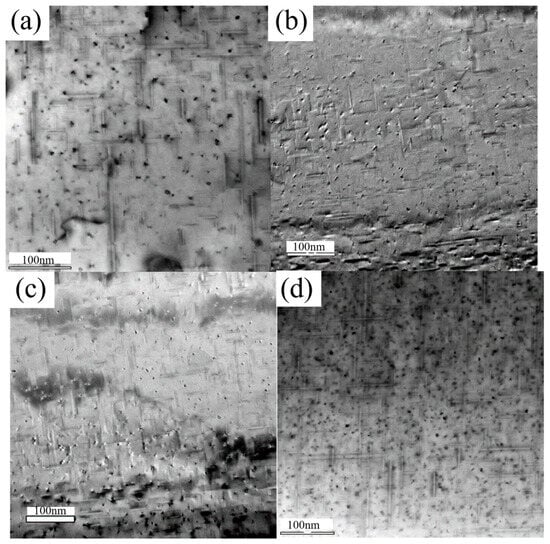

3.2.3. TEM Bright-Field Images of Peak-Aged Alloys

Figure 8a–d present a systematic comparison of the bright-field transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images for alloys #1 to #4 in their peak-aged condition(NA0d), elucidating the influence of different microalloying additions on the morphology, size, and distribution of the strengthening precipitates. A high density of nano-scale precipitates was uniformly formed in all alloys. These precipitates, aligned along the <001> Al directions of the matrix, exhibited the characteristic fine needle- or rod-like morphology of the predominant β″ phase; depending on the specific observation direction (e.g., B//[001]Al), their projections could appear as near-circular dots or short needles. The monoclinic β″ phase is established as the core strengthening precipitate in peak-aged Al-Mg-Si alloys.

Figure 8.

TEM bright-field images of alloys (a–d) in the peak-aged condition(NA0d).

A direct comparison reveals a significant microstructural refinement induced by Sn addition. The Sn-containing alloys (Figure 8c,d) exhibited a markedly higher number density of β″ precipitates compared to their Sn-free counterparts (Figure 8a,b). Furthermore, the precipitates in the Sn-modified alloys demonstrated a more uniform spatial distribution and a refined average size. This distinct microstructural characteristic provides a direct correlation with the macroscopic hardness measurements: a higher density of finer nano-precipitates creates more effective obstacles to dislocation glide, thereby generating a stronger precipitation strengthening effect. This microstructure–property relationship conclusively explains the superior peak hardness achieved in the Sn-containing alloys.

Therefore, the TEM analysis substantiates that the addition of Sn enhances the alloy’s strength primarily by refining the β″ precipitate microstructure—specifically by increasing its number density and improving its distribution uniformity. This constitutes the key micro-mechanism underlying the optimized strengthening response in the Sn-microalloyed alloys.

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- In Al-Mg-Si alloys, the addition of Mn Er, and Zr in combination with an optimized stepwise homogenization treatment (250 °C/3 h + 300 °C/12 h + 375 °C/12 h) effectively promotes the formation of thermally stable α-Al(Fe,Mn)Si and Al(Er,Zr) dispersoids. These phases might effectively pin dislocations and grain boundaries, significantly inhibiting microstructural softening at elevated temperatures.

- (2)

- The presence of Sn and Mn has distinct effects on the natural aging and artificial aging behavior of the alloys. Alloys containing Sn maintained a lower hardness compared to their Sn-free counterparts during natural aging, indicating that Sn slows down the initial hardening process. On the other hand, the addition of Mn had a positive impact on increasing hardness in the naturally aged condition.

- (3)

- Artificial Aging Progress: After undergoing natural aging, the Sn-added alloy #2 exhibited an accelerated initial response during subsequent artificial aging, but achieved a lower peak hardness. The alloy with combined addition of Mn and Sn showed that their combination exacerbates the suppressive effect of natural aging on peak strengthening.

Author Contributions

J.Z.: Methodology, Conceptualization, Validation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. Y.L.: Methodology, Conceptualization, Formal analysis. S.W.: Methodology, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing—review and editing, Resources. X.W.: Formal analysis, Methodology, Conceptualization. K.G.: Formal analysis, Methodology, Conceptualization. L.R.: Formal analysis, Methodology, Conceptualization. W.W.: Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Resource. H.H.: Formal analysis, Resource, Conceptualization. Z.N.: Formal analysis, Resource, Conceptualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China [2021YFB3700902]; the National Natural Science Foundation of China [52494943]; the Beijing Lab Project for Modern Transportation Metallic Materials and Processing Technology.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, H.; Qingzhong, M.; Wang, Z.; Miao, F.; Fang, B.; Song, R.; Zheng, Z. Simultaneously enhancing the tensile properties and intergranular corrosion resistance of Al–Mg–Si–Cu alloys by a thermo-mechanical treatment. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2014, 617, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Goel, S.; Jayaganthan, R.; Brokmeier, H.-G. Effect of grain boundary misorientaton, deformation temperature and AlFeMnSi-phase on fatigue life of 6082 Al alloy. Mater. Charact. 2017, 124, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Du, J.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhuang, L. Influence of Zn contents on precipitation and corrosion of Al-Mg-Si-Cu-Zn alloys for automotive applications. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 778, 256–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, S.; Marioara, C.; Vissers, R.; Frøseth, A.; Zandbergen, H. The structural relation between precipitates in Al–Mg–Si alloys, the Al-matrix and diamond silicon, with emphasis on the trigonal phase U1-MgAl2Si2. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2007, 444, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Čížek, J.; Chang, C.S.; Banhart, J.J.A.M. Early stages of solute clustering in an Al–Mg–Si alloy. Acta Mater. 2015, 91, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wang, M.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Q.; Sheng, X. The diffraction patterns from β ″precipitates in 12 orientations in Al–Mg–Si alloy. Scr. Mater. 2010, 62, 705–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, K.; Chen, X.-G. Improvement of elevated-temperature strength and recrystallization resistance via Mn-containing dispersoid strengthening in Al-Mg-Si 6082 alloys. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2020, 39, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Nagaumi, H.; Han, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zhai, T.J.M. The deformation behavior and microstructure evolution of a Mn-and Cr-containing Al-Mg-Si-Cu alloy during hot compression and subsequent heat treatment. Met. Mater. Trans. A 2017, 48, 1355–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muggerud, A.M.F.; Mørtsell, E.A.; Li, Y.; Holmestad, R.J.M.S. Dispersoid strengthening in AA3xxx alloys with varying Mn and Si content during annealing at low temperatures. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2013, 567, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.; Poole, W.; Wells, M.; Parson, N.J.A.M. Microstructure evolution during homogenization of Al–Mn–Fe–Si alloys: Modeling and experimental results. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2013, 61, 4961–4973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Lu, J.; Tan, S.; Jiang, F.; Sun, J. Effects of Pre-Deformation on Precipitation Behaviors and Properties in Cu-Ni-Si-Cr Alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 742, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, F.; Jin, S.; Sha, G.; Li, Y. Enhanced Dispersoid Precipitation and Dispersion Strengthening in an Al Alloy by Microalloying with Cd. Acta Mater. 2018, 157, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sircar, S. Machineable Aluminum Alloys Containing In and Sn and Process for Producing the Same. U.S. Patent No. 5,587,029, 24 December 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.Q.; Yin, Z.M. Effects of Aging on Microstructure and Properties of a Novel Lead-Free Free-Cutting Al-Mg-Si Alloy Microalloyed with Sn and Bi. China Molybdenum Ind. 2007, 31, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogatscher, S.; Antrekowitsch, H.; Leitner, H.; Sologubenko, A.S.; Uggowitzer, P.J. Influence of the thermal route on the peak-aged microstructures in an Al–Mg–Si aluminum alloy. Scr. Mater. 2013, 68, 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werinos, M.; Antrekowitsch, H.; Ebner, T.; Prillhofer, R.; Curtin, W.A.; Uggowitzer, P.J.; Pogatscher, S. Design strategy for controlled natural aging in Al–Mg–Si alloys. Acta Mater. 2016, 118, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werinos, M.; Antrekowitsch, H.; Ebner, T.; Prillhofer, R.; Uggowitzer, P.J.; Pogatscher, S. Hardening of Al–Mg–Si alloys: Effect of trace elements and prolonged natural aging. Mater. Des. 2016, 107, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Ma, P.; Zhan, L.; Huang, M.; Li, J. Solute Sn-induced formation of composite β′/β″ precipitates in Al-Mg-Si alloy. Scr. Mater. 2018, 155, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.; Jia, Z.; Weng, Y.; Hao, L.; Liu, Q. Effects of Sn/In additions on natural and artificial ageing of Al–Mg–Si alloys. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2018, 34, 2136–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, M.; Sun, H.; Banhart, J. Influence of Sn on the age hardening behavior of Al–Mg–Si alloys at different temperatures. Materialia 2019, 8, 100441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, W.; Tang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, L.; Ma, L.; Zhu, Q.; Liu, S. Influence of Sn on the precipitation and hardening response of natural aged Al-0.4Mg-1.0Si alloy artificial aged at different temperatures. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 765, 138250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, W.; Tang, J.; Ye, L.; Cao, L.; Zeng, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Yang, B. Effect of the natural aging time on the age-hardening response and precipitation behavior of the Al-0.4Mg-1.0Si-(Sn) alloy. Mater. Des. 2021, 198, 109307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Li, J.; Wei, B.; Liang, T.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wang, S. Sn–Sc microalloying-induced property improvement and micromechanisms of an Al–Mg–Si alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 27, 472–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Chen, X.J.; Liao, G.Z.; Ali, A.; Wang, S.B. Developing a high-performance Al–Mg–Si–Sn–Sc alloy for essential room-temperature storage after quenching: Aging regime design and micromechanisms. Rare Met. 2023, 42, 3814–3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wei, W.; Shi, W.; Zhou, X.; Wen, S.; Wu, X.; Nie, Z. Synergistic effect of Al3(Er, Zr) precipitation and hot extrusion on the microstructural evolution of a novel Al–Mg–Si–Er–Zr alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 22, 947–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, P.; Mo, W.; Ouyang, Z.; Ling, K.; Luo, B.; Bai, Z. Microstructural evolution and corrosion mechanism of micro-alloyed 2024 (Zr, Sc, Ag) aluminum alloys. Corros. Sci. 2023, 224, 111476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, W.; Zhao, Y.; Kai, X.; Gao, X.; Huang, L.; Miao, C. Characteristics of microstructural and mechanical evolution in 6111Al alloy containing Al3 (Er, Zr) nanoprecipitates. Mater. Charact. 2021, 178, 111310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Bin, J.; Liu, J.; Gao, Z.; Lu, X. Precipitation evolution and coarsening resistance at 400 °C of Al microalloyed with Zr and Er. Scr. Mater. 2012, 67, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Ogura, T.; Tezuka, H.; Sato, T.; Liu, Q. Dispersoid formation and recrystallization behavior in an Al-Mg-Si-Mn alloy. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2010, 26, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milkereit, B.; Starink, M.J.; Rometsch, P.A.; Schick, C.; Kessler, O. Review of the Quench Sensitivity of Aluminium Alloys: Analysis of the Kinetics and Nature of Quench-Induced Precipitation. Materials 2019, 12, 4083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.J.; Jiang, H.C.; Zhang, D.; Song, Y.Y.; Yan, D.S.; Rong, L.J. Influence of Mn on the negative natural aging effect in 6082 Al alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 793, 139874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.