Advanced Electronic Materials for Liquid Thermal Management of Lithium-Ion Batteries: Mechanisms, Materials and Future Development Directions

Abstract

1. Introduction

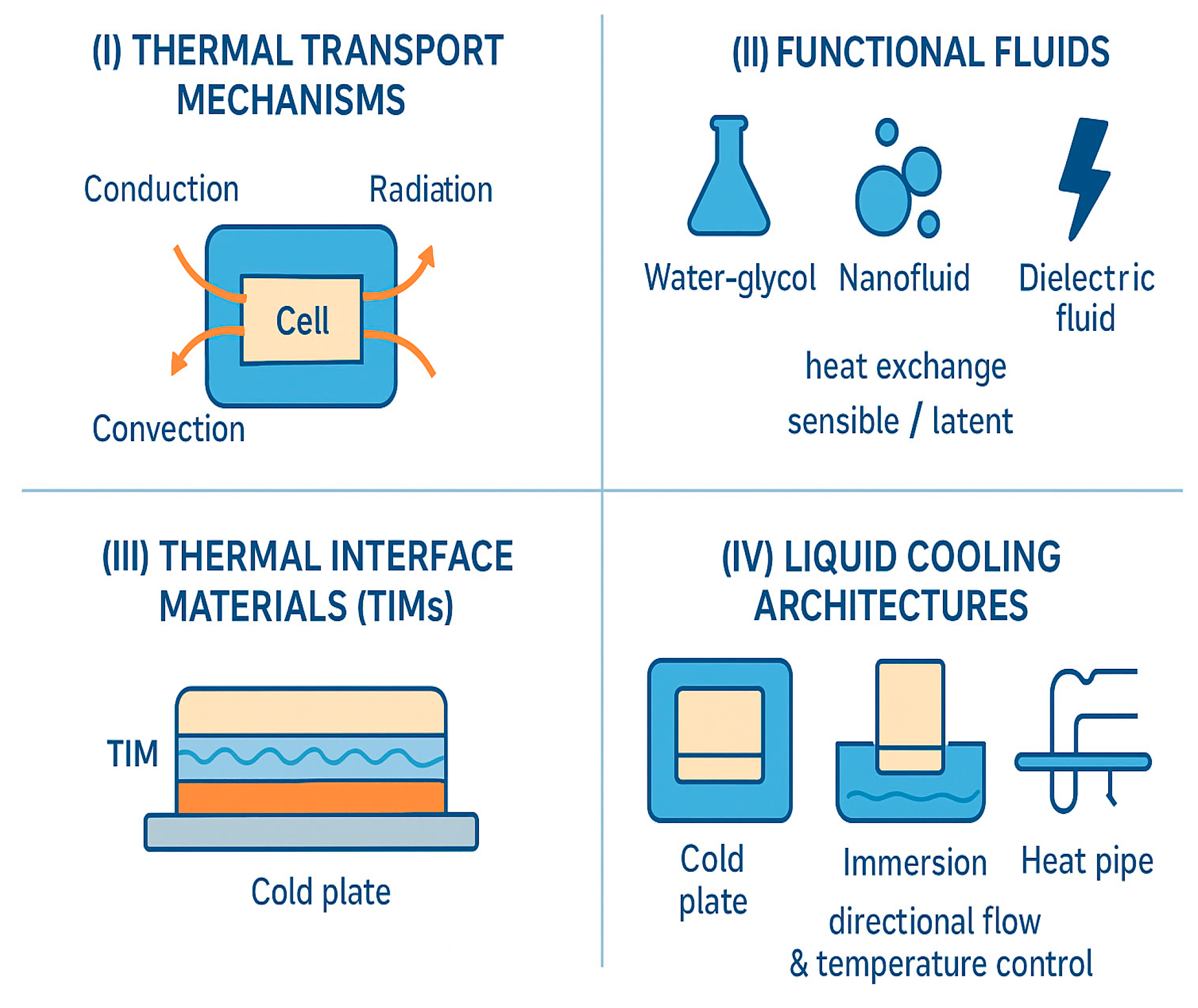

- I

- Thermal transport mechanisms: Battery work, the internal chemical reaction or electrical energy loss heat production, heat first by heat conduction (orange arrow, such as the battery shell and other solid intermolecular collision transfer) from the core to the surface diffusion; contact with the surrounding fluid, the start of thermal convection (red ripples, relying on the flow of fluid to take away the heat) to move away from the heat; at the same time, the heat radiation (in the form of electromagnetic waves, the diffusion of ripples in the figure illustrates) to the low-temperature environment of the spontaneous radiation, the three modalities Collaboration to realize the heat “move out” is the basic principle of thermal management, explaining the heat transfer path from the internal battery to the external environment.

- II

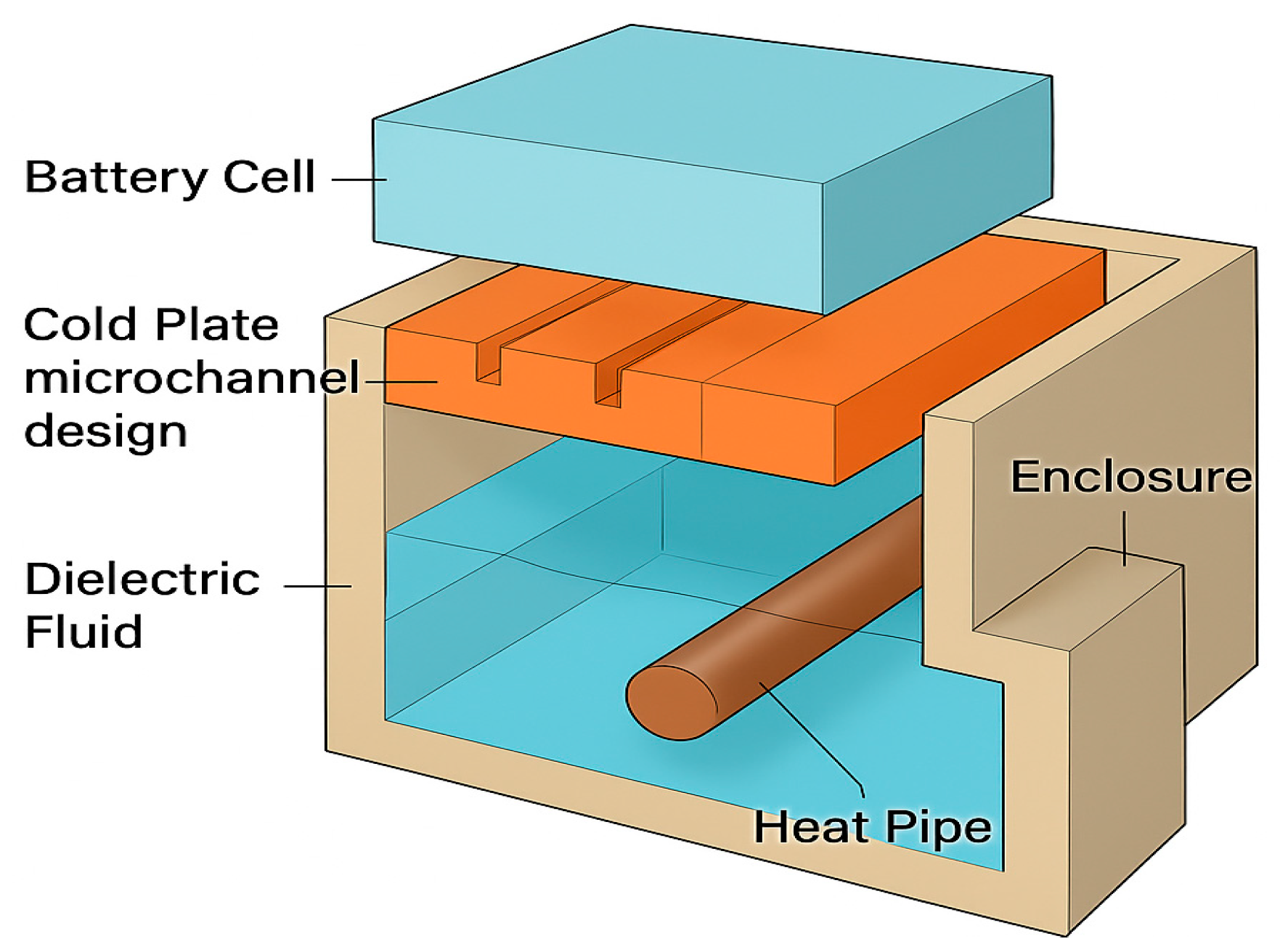

- Functional fluids: Used in scenarios where there is a need for insulation (e.g., coolant for electronic equipment) and transferring heat and at the same time avoiding short-circuiting by means of chemical properties (stable molecular structure, non-conducting) to safeguard heat dissipation and safety. Typical examples are submerged coolants; coolant takes away heat by means of a phase change (evaporation/condensation) or sensible heat (change in temperature), such as water-glycol and refrigerant, commonly used in automobile tanks and computer water-cooling. The model implies that the chemical composition can be adjusted to adapt to the scene; the liquid cooling system heat transfer is the “carrier”.

- III

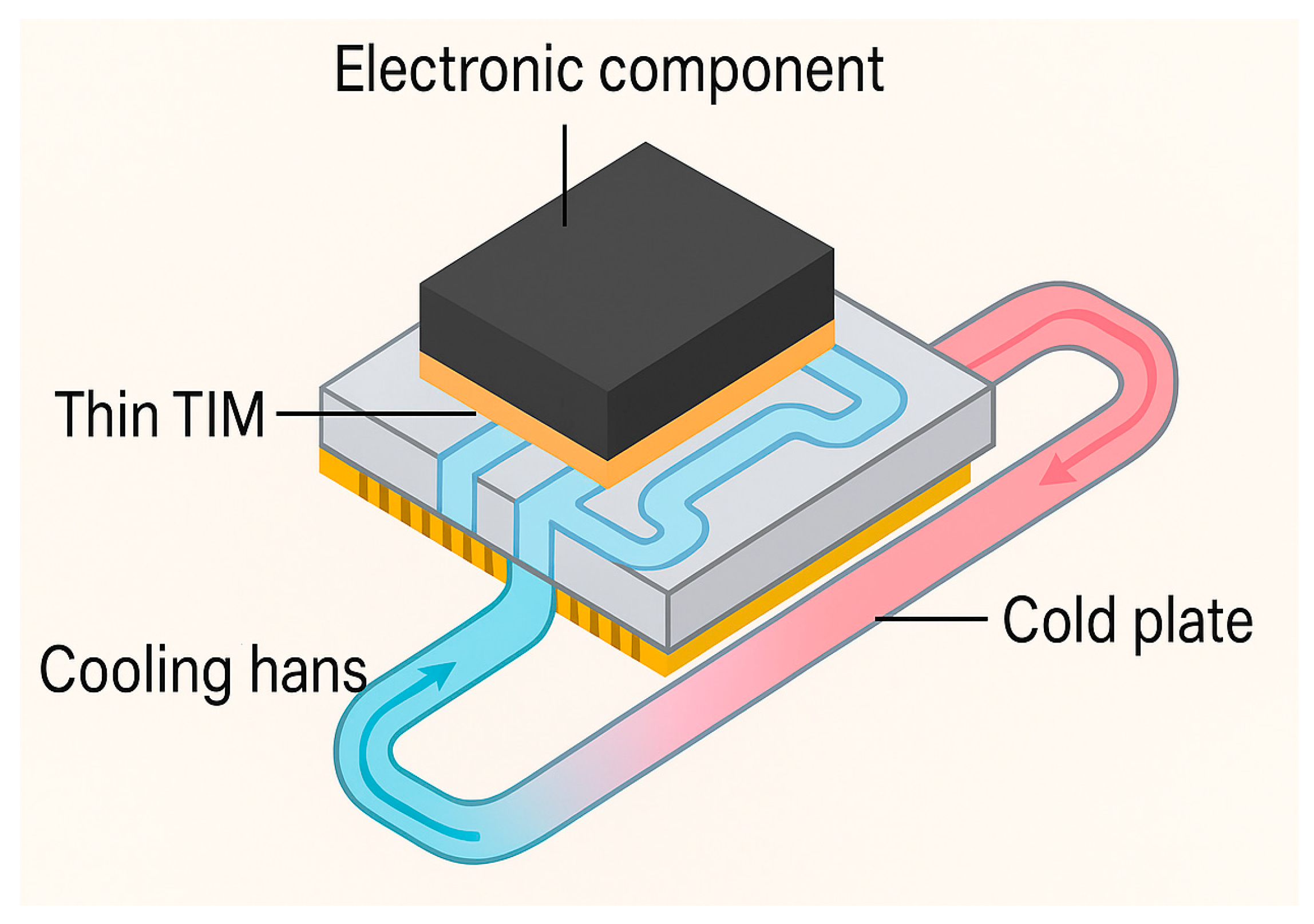

- Interface materials: Fill the gap between the battery and the heat dissipation structure, changing “point contact” to “surface contact”, reducing the interface thermal resistance (the obstruction to heat transfer when two solids are in contact), and making the heat conduction smoother.

- IV

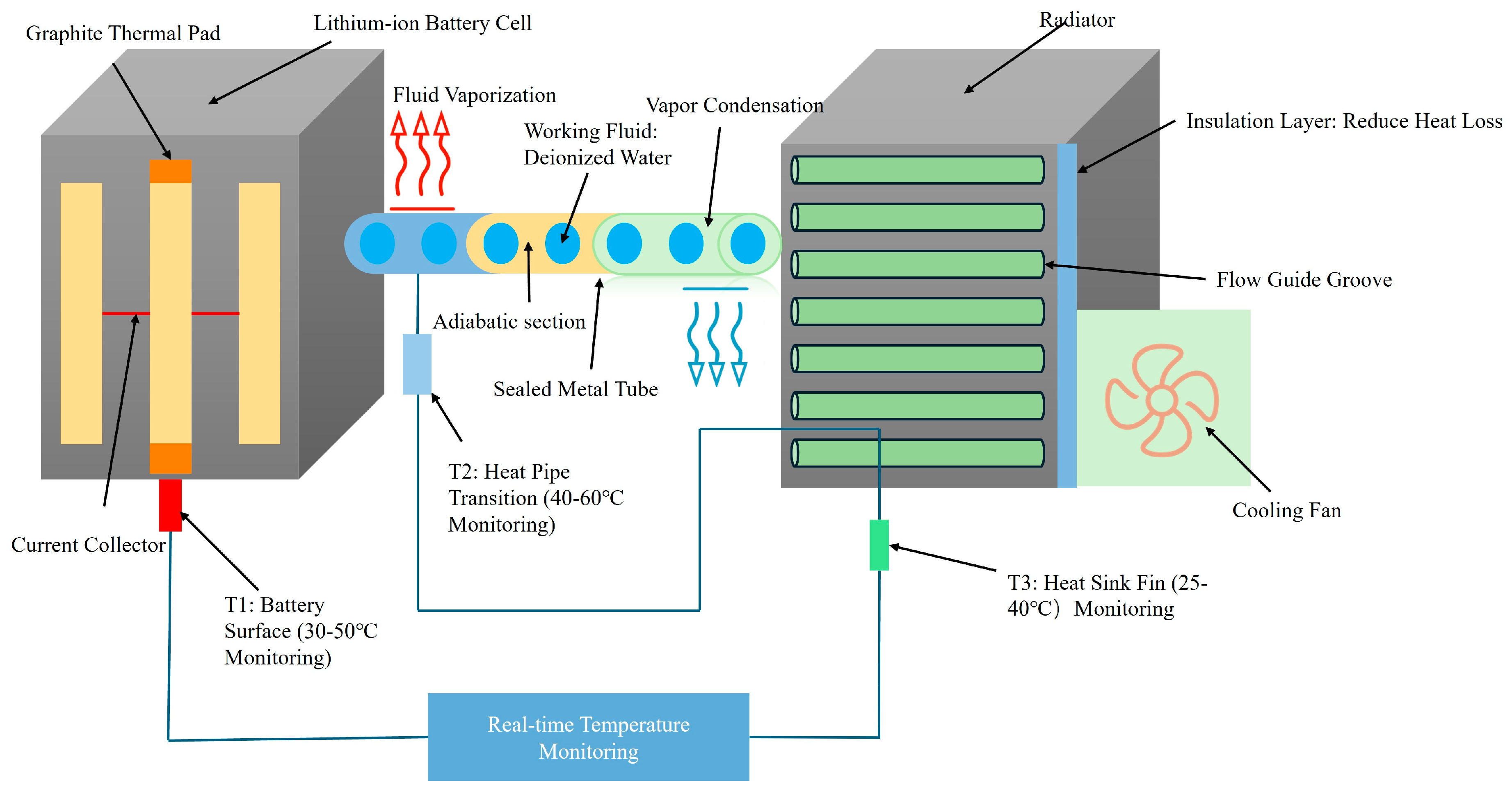

- Liquid cooling systems: A cold plate, with flow channels machined inside (the orange lines represent the coolant channels), is directly pressed onto the surface of the heat-generating component. The coolant circulates to absorb heat. Immersion, by immersing the heat-generating component directly into the coolant, achieves 360° heat exchange without any dead zones, enhancing the heat dissipation efficiency. Heat pipes, relying on the “phase change magic”, transfer heat remotely. The working medium (water, ammonia, etc.) in the pipe evaporates at the heated end to absorb heat, releases heat at the condensation end and liquefies, and the liquid flows back through the capillary structure. It can “instantly transfer” heat to a distant location.

2. The Working Principle and Thermal Characteristics of Lithium-Ion Batteries

2.1. Working Principle of Lithium-Ion Battery

2.2. Thermal Characteristics of Batteries

3. Overview of Liquid Thermal Management Techniques

3.1. Function of Liquid Thermal Management Technology

3.2. Classification of Liquid Thermal Management Techniques

3.3. Comparative Performance of Different Liquid Cooling Techniques

4. Structural Materials for Liquid Cooling Systems

4.1. Indirect Contact Liquid Cooling

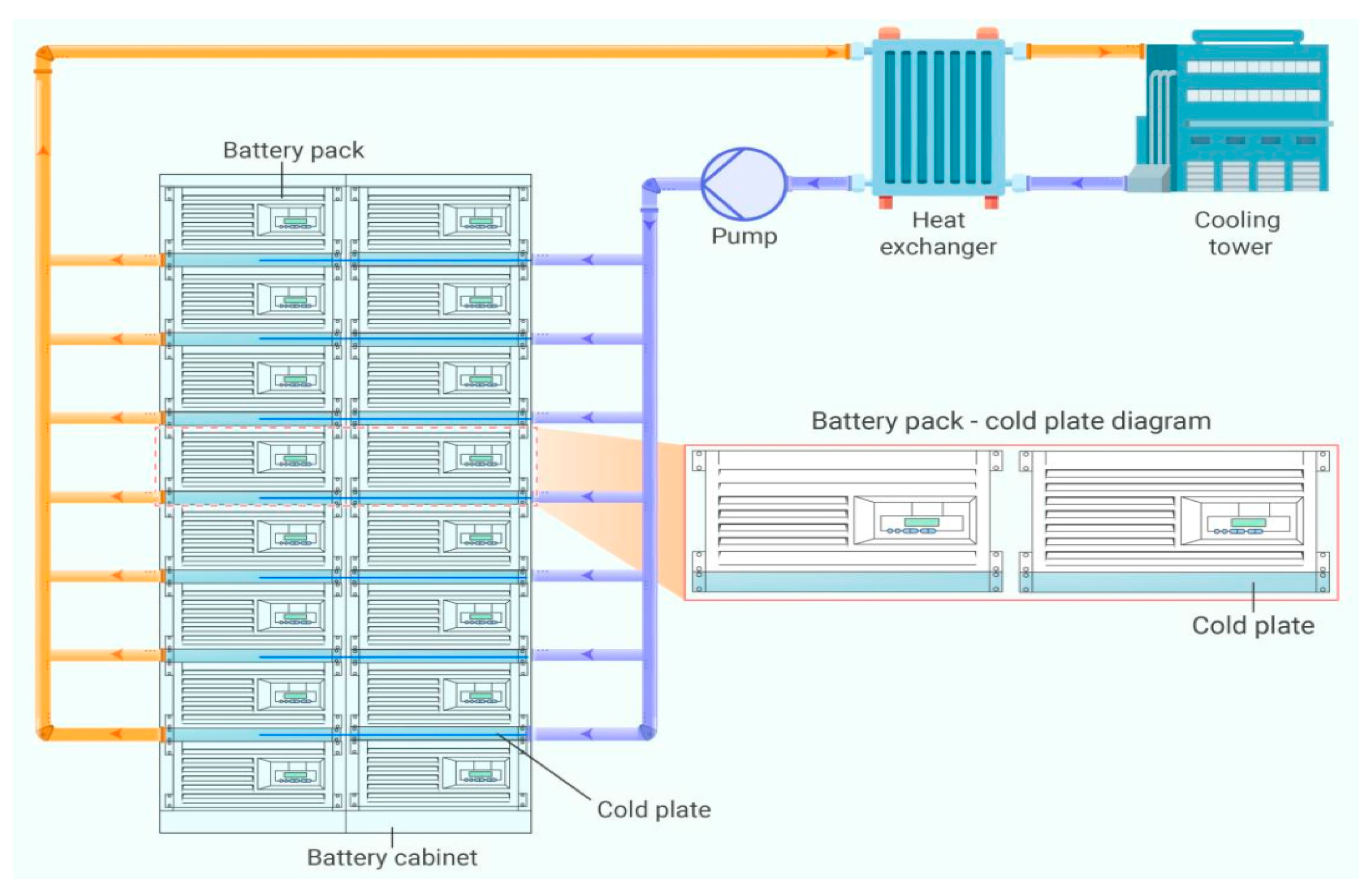

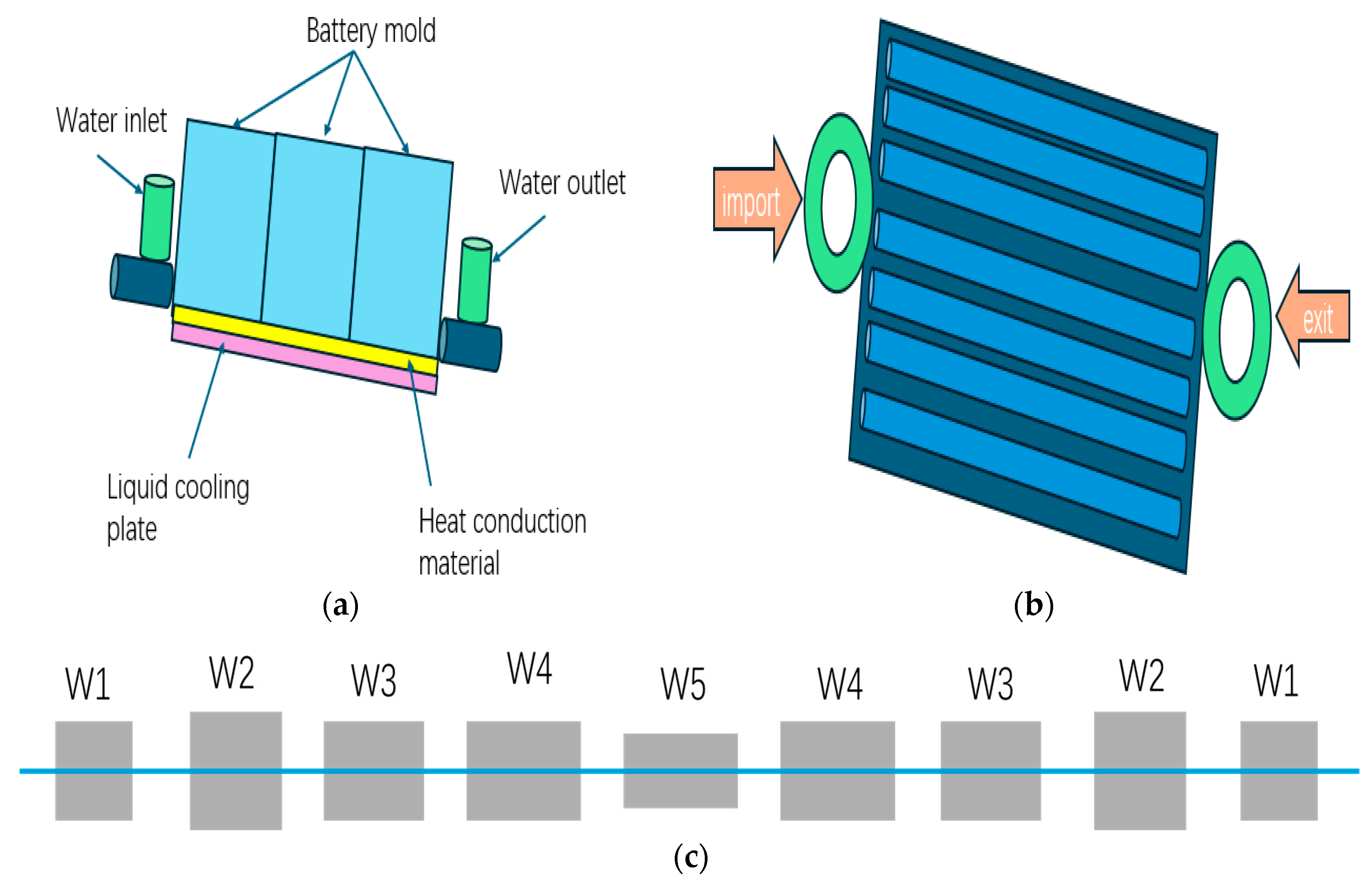

4.1.1. Liquid Cooled Plate

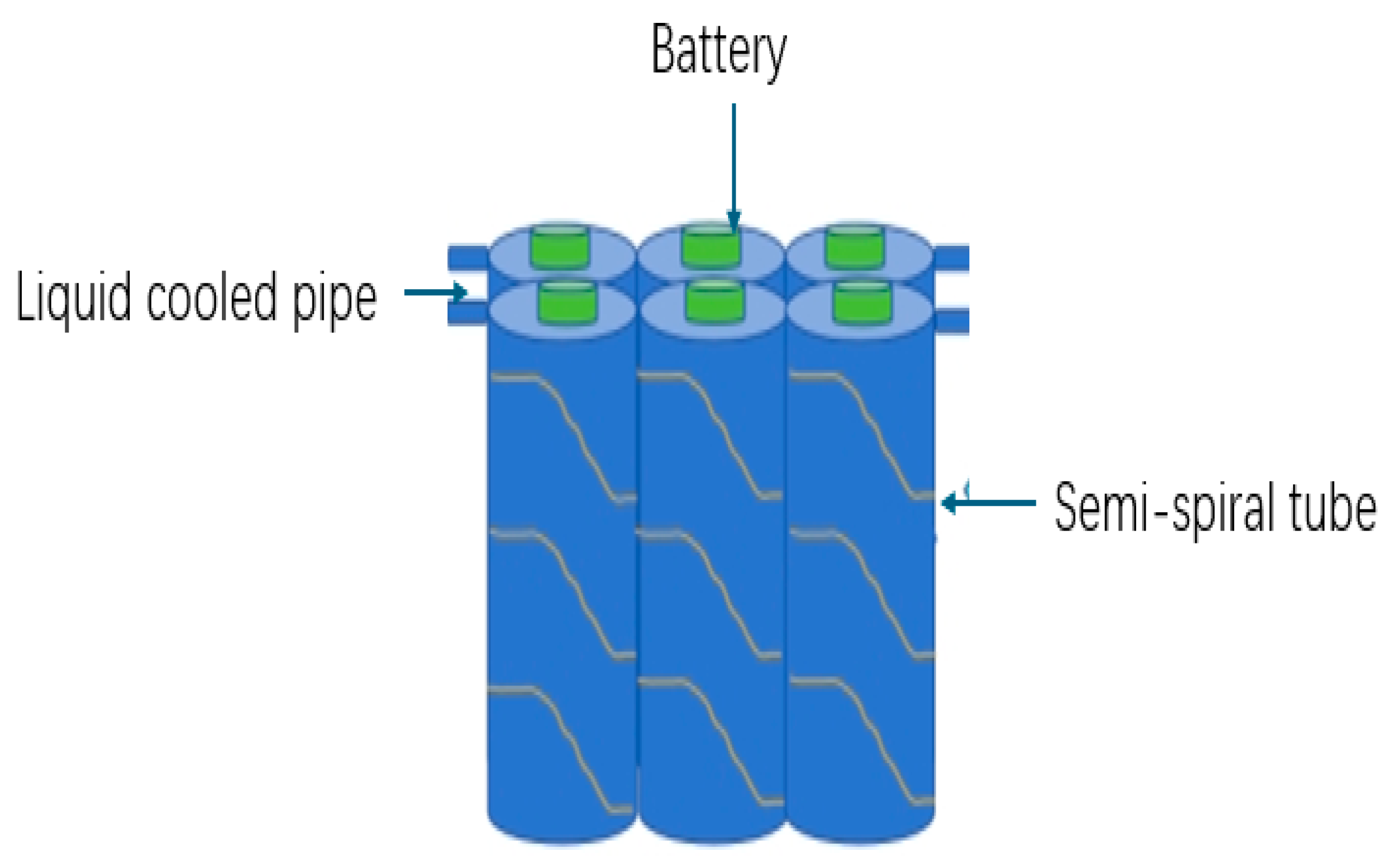

4.1.2. Liquid Cooled Pipe Type

4.2. Direct Contact Liquid Cooling

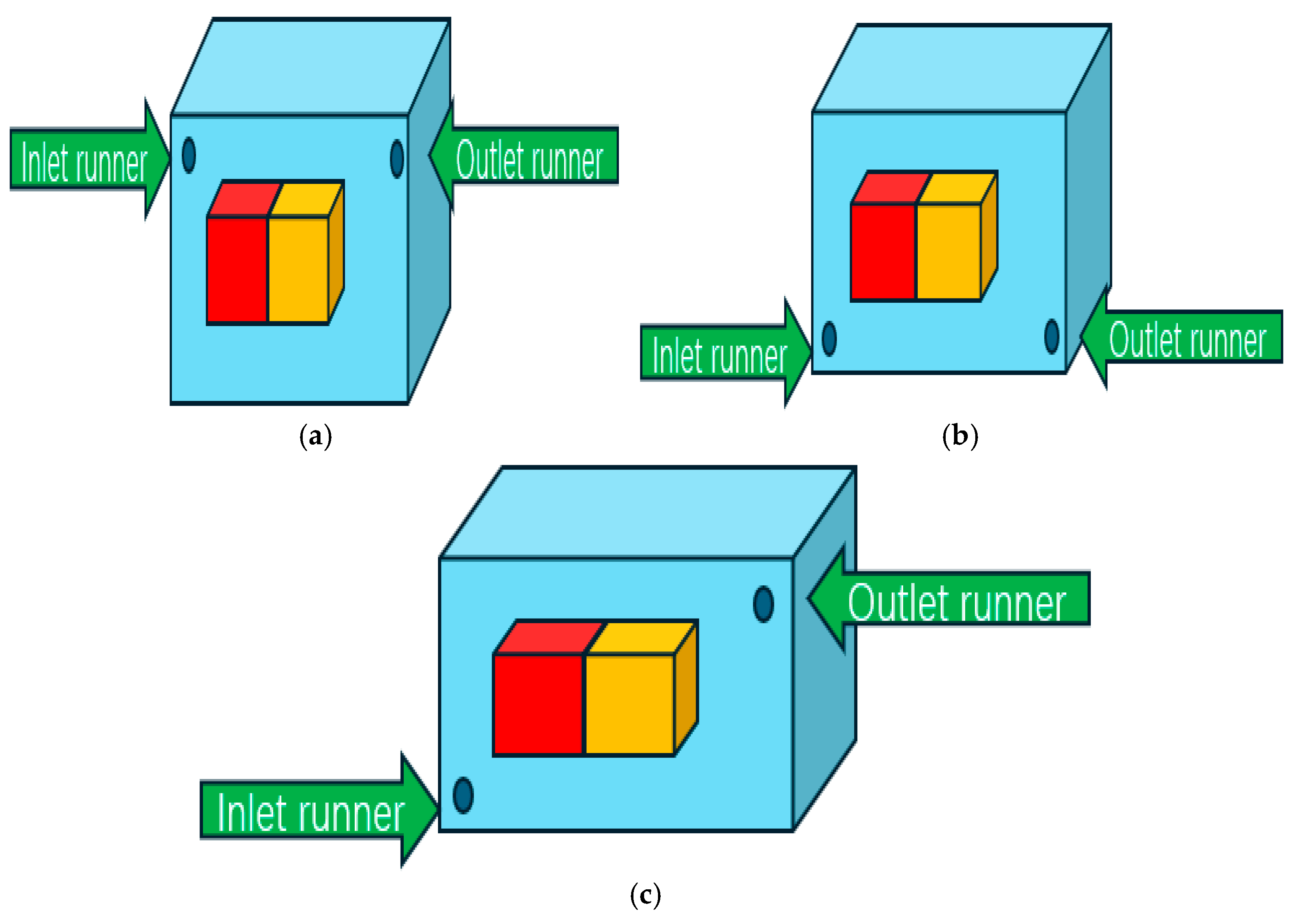

4.2.1. Immersion Type

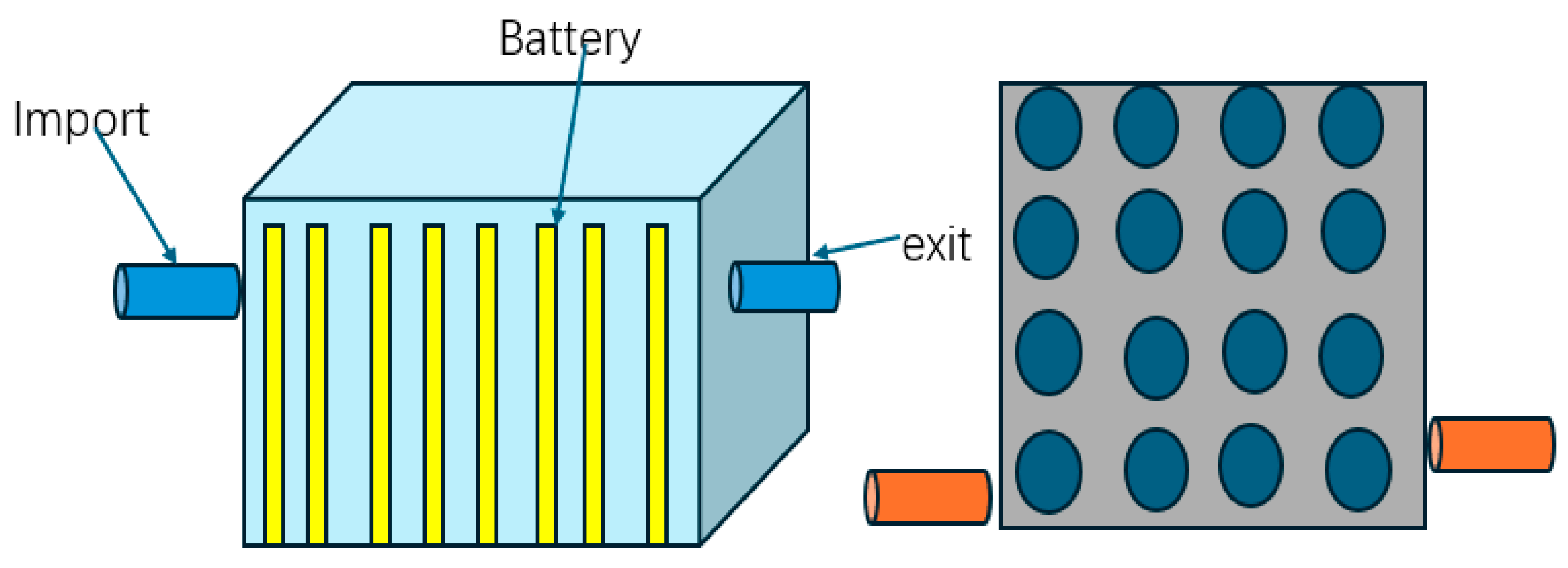

4.2.2. Non-Submerged Type

5. Simulation Research

5.1. Research Status

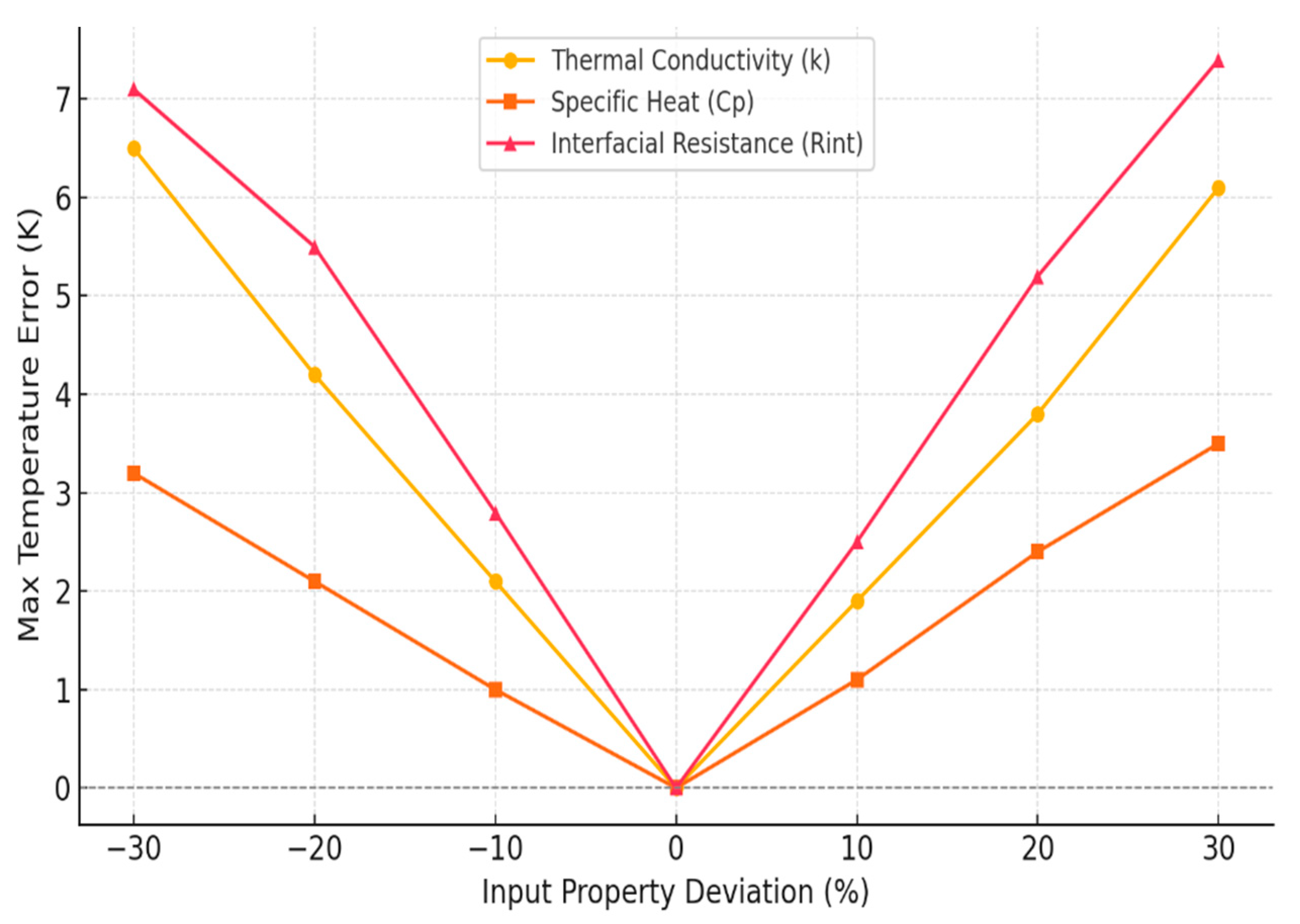

5.2. Influence of Material Parameters on Numerical Thermal Simulations

5.3. Challenges

6. Summary and Prospect

6.1. Summary

6.2. Prospect

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, L.; Jin, X.; Chun, E.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J. Thermal behavior and failure mechanisms of lithium-ion battery under high discharging rate. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 278, 127043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Wang, J.; Guo, R.; Wang, J.; Song, J.; Wang, K. Electrode Materials and Prediction of Cycle Stability and Remaining Service Life of Supercapacitors. Coatings 2026, 16, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Guo, F.; Wei, Z.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, Y. Highly hygroscopic nee dle-punche d carbon fiber felt with high evaporative cooling efficiency and fire resistance for safe operation of ultrahigh-rate lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 220, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Xu, K.; Chen, Z.; Wang, K. Advanced Techniques for Internal Temperature Monitoring in Lithium-Ion Batteries: A Review of Recent Developments. Coatings 2025, 15, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattia, L.; Beiranvand, H.; Zamboni, W.; Liserre, M. Lithium-ion battery thermal modelling and characterisation: A comprehensive review. J. Energy Storage 2025, 129, 117114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yang, T.; Chen, L.; Shi, J.; Zhang, T.; Zeng, C.; Liu, R.; Tang, S. Thermal management study of cylindrical battery using novel thermally conductive anisotropic flexible phase change material. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 73, 106508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, P.; Ma, F.; Li, Y.; Gu, L.; Wang, G.; Shen, R.; Wang, J.; Zhao, J. Investigation on topology optimization of cold plate for battery thermal management based on phase change slurry. Innov. Energy Учредители Innov. Press Co. Ltd. 2025, 2, 100061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, Z.; Li, M.; Ren, F.; Feng, Y. A manifold channel liquid cooling system with low-cost and high temperature uniformity for lithium-ion battery pack thermal management. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2023, 41, 101857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Guo, X.; Tan, P.; Yan, B.; Lin, M.; Cai, J.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, W.; Zhang, X.-A. A graphene aerogel with reversibly tunable thermal resistance for battery thermal management. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11, 17779–17786. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Pan, Y.; Liu, X.; Cao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Mao, Y.; Liu, B. Criteria and design guidance for lithium-ion battery safety from a material perspective. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 6538–6550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadim, H.B.; Godin, A.; Veillere, A.; Duquesne, M.; Haillot, D. Review of thermal management of electronics and phase change materials. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 208, 115039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganeshkumar, P.; Kumar, G.P.; Sivalingam, V.; Divya, S.; Oh, T.H. Revolutionizing microelectronics cooling: Thermal management with nano-enhanced PCMs, hybrid cooling, conductive foams, and porous structures. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 222, 115954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Du, H.; Lu, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, S.; Du, X. Interface synergistic stabilization of zinc anodes via polyacrylic acid doped polyvinyl alcohol ultra-thin coating. J. Energy Storage 2024, 87, 111444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, M.M.; Shouman, M.A.; Salem, M.S.; Kannan, A.M.; Hamed, A.M. Advances in thermal management systems for Li-Ion batteries: A review. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2024, 53, 102714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thawkar, V.; Dhoble, A.S. A review of thermal management methods for electric vehicle batteries based on heat pipes and PCM. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2023, 45, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Jiang, B.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, J.; Wang, K. Source-Load Coordinated Optimization Framework for Distributed Energy Systems Using Quasi-Potential Game Method. Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst. 2025, 10, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhou, Y.; Gao, Y.; Feng, X.; Zhang, F.; Li, W.; Zhu, B.; Tian, Z.; Fan, P.; Zhong, M.; et al. Large-scale assembly of isotropic nanofiber aerogels based on columnar-equiaxed crystal transition. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Hu, Y.; Du, X.; Lu, J.; Li, Z.; Cao, N.; Zhang, S.; Du, H. Movable SiO2 reinforced polymethyl methacrylate dual network coating for highly stable zinc anodes. J. Energy Storage 2025, 132, 117752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Lu, R. Physics-Informed Neural Networks for Advanced Thermal Management in Electronics and Battery Systems: A Review of Recent Developments and Future Prospects. Batteries 2025, 11, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Hu, J.; Xia, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Shen, J.; Wei, F. Grouping optimization of dual-system mixed lithium-ion battery pack considering thermal characteristics. J. Energy Storage 2025, 118, 116281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xu, W.; Tian, H.; Cao, Y.; Gu, J.; Zhou, H.; Jin, Y. Review on Lithium-Ion Battery Heat Dissipation Based on Microchannel-PCM Coupling Technology. Energies 2025, 18, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Feng, X.; Pang, Q.; Fowler, M.; Lian, Y.; Ouyang, M.; Burke, A.F. Battery safety: Machine learning-based prognostics. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2024, 102, 101142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Yuan, N.; Kong, B.; Zou, Y.; Shi, H. Simulation of hybrid air-cooled and liquid-cooled systems for optimal lithium-ion battery performance and condensation prevention in high-humidity environments. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 257, 124455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cai, J.; Sheng, D. Recent advances in polymerized lithium-ion battery separators. Eng. Plast. Appl. 2024, 52, 154–164. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Guo, Y.; Ren, Y.; Yeboah, S.; Wang, J.; Long, F.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, R. Investigation of the thermal management potential of phase change material for lithium-ion battery. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 236, 121590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkateswarlu, B.; Kim, S.C.; Joo, S.W.; Chavan, S. Numerical Investigation of Nanofluid as a Coolant in a Prismatic Battery for Thermal Management Systems. J. Therm. Sci. Eng. Appl. 2024, 16, 031003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamy, K.A.; Verma, S. Experimental and Numerical Investigation for Optimization of a Hybrid Battery Thermal Management System Based on Phase Change Material and Air Convection. J. Therm. Sci. Eng. Appl. 2024, 16, 121004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorshakoor, E.; Darab, M. Advancements in the development of nanomaterials for lithium-ion batteries: A scientometric review. J. Energy Storage 2024, 75, 109638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Yuan, W.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, X. A pourable, thermally conductive and electronic insulated phase change material for thermal management of lithium-ion battery. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 489, 151310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehra, M.; Dilbaghi, N.; Kumar, R.; Srivastava, S.; Tankeshwar, K.; Kim, K.-H.; Kumar, S. Catalytic applications of phosphorene: Computational design and experimental performance assessment. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 54, 185–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhin, S. Recovery of Ni-Co-Mn Oxides from End-of-Life Lithium-Ion Batteries for the Application of a Negative Temperature Coefficient Sensor. Inorganics 2024, 12, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Cong, J.; Ding, Y.; Yang, Y.; Huang, K.; Ge, X.; Chen, K.; Zeng, T.; Huang, Z.; Fang, C.; et al. Strategies for Intelligent Detection and Fire Suppression of Lithium-Ion Batteries. Electrochem. Energy Rev. 2024, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, P.; Samadder, S.R. Urban mining for graphite recovery from retired lithium-ion batteries and its valorization to valuable graphene materials: A comprehensive characterization study. J. Energy Storage 2024, 102, 113873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.R.U.; Iqbal, N.; Noor, T.; Ali, M.; Khan, A.; Nazar, M.W. Thermal management of Li-ion battery by using eutectic mixture of phase-change materials. J. Energy Storage 2024, 90, 111858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Li, Y.; Liang, Q.; Niu, Y.; Zheng, S.; Zhuo, Z.; Luo, Y.; Liang, B.; Yang, D.; Yin, J. Uncovering the Critical Role of Ni on Surface Lattice Stability in Anionic Redox Active Li1.2Ni0.2Mn0.6O2. Carbon Energy 2025, 7, e699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xu, X.; Shen, J.; Wen, N.; Qian, J.; Su, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhou, F. Performance of flexible composite phase change material with hydrophobic surface for battery thermal management. J. Energy Storage 2024, 103, 114273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhosale, A.; Deshmukh, V.; Chaudhari, M. A comprehensive assessment of emerging trends in battery thermal management systems. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2024, 46, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, P.; Wang, M.; Chen, C.; Yan, L.; Gao, Y.; Yang, S.; Chen, M.; Zhao, C.; Mao, J. Research progress of thermal management technology for lithium-ion batteries. Chin. J. Process Eng. 2023, 23, 1102–1117. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Ranneberg, M.; Fischlschweiger, M. High-Temperature Phase Behavior of Li2O-MnO with a Focus on the Liquid-to-Solid Transition. JOM 2023, 75, 5796–5807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; An, Y.; Zhang, L.; Mai, L.; Ma, T.; An, Q.; Wang, Q. Shape-stabilized phase change material based on MOF-derived oriented carbon nanotubes for thermal management of lithium-ion battery. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, B.Z. Understanding Failure Mechanisms using Multi-Scale Analyses to Improve the Performance of Zinc Metal and Lithium-ion Batteries. Ph.D. Thesis, The City College of New York, New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dobo, Z.; Dinh, T.; Kulcsar, T. A review on recycling of spent lithium-ion batteries. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 6362–6395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coskun, T.; Cetkin, E. Cold plate enabling air and liquid cooling simultaneously: Experimental study for battery pack thermal management and electronic cooling. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 217, 124702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, C.; Wu, C.-W.; Zhou, W.-X.; Xie, G.; Zhang, G. Thermal transport in lithium-ion battery: A micro perspective for thermal management. Front. Phys. 2022, 17, 13202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Zhang, Y.; Yi, J.; Dong, F.; Chen, P. Overview of Surface Modification Techniques for Titanium Alloys in Modern Material Science: A Comprehensive Analysis. Coatings 2024, 14, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Yu, F. Cascade phase change based on hydrate salt/carbon hybrid aerogel for intelligent battery thermal management. J. Energy Storage 2022, 45, 103771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrisi, A.; Tabarelli, F.; Brunelli, D. Battery Thermal Dissipation Characterization with External Coating Comparison. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Industry 40 & Iot (IEEE Metroind40&Iot), Rome, Italy, 10–12 June 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 190–194. [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta, J.; Hussain, C.M. Graphene-Induced Performance Enhancement of Batteries, Touch Screens, Transparent Memory, and Integrated Circuits: A Critical Review on a Decade of Developments. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghi, G. Energy storage on demand: Thermal energy storage development, materials, design, and integration challenges. Energy Storage Mater. 2022, 46, 192–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman-Ramirez, L.A.; Marco, J. Design of experiments applied to lithium-ion batteries: A literature review. Appl. Energy 2022, 320, 119305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozafari, M.; Lee, A.; Cheng, S. Improvement on the cyclic thermal shock resistance of the electronics heat sinks using two-objective optimization. J. Energy Storage 2022, 46, 103923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, P. Physics-informed machine learning for battery pack thermal management. In Proceedings of the 2025 Annual Reliability and Maintainability Symposium (RAMS), Miramar Beach, FL, USA, 27–30 January 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Zhai, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Di, Y.; Chen, X. Physics-informed neural network for lithium-ion battery degradation stable modeling and prognosis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhao, H.-W.; Wang, X.-R.; Zhao, J.-Q.; Kong, H.-R.; Wang, T.; Liang, C.; Li, J.-H.; Xu, W.Q. A hierarchically encapsulated phase-change film with multi-stage heat management properties and conformable self-interfacing contacts for enhanced interface heat dissipation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 23617–23629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zheng, R.; Li, J. High latent heat phase change materials (PCMs) with low melting temperature for thermal management and storage of electronic devices and power batteries: Critical review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 168, 112783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Cen, J.; Jiang, F. A Lightweight Compact Lithium-Ion Battery Thermal Management System Integratable Directly with EV Air Conditioning Systems. J. Therm. Sci. 2022, 31, 2363–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Held, M.; Tuchschmid, M.; Zennegg, M.; Figi, R.; Schreiner, C.; Mellert, L.D.; Welte, U.; Kompatscher, M.; Hermann, M.; Nachef, L. Thermal runaway and fire of electric vehicle lithium-ion battery and contamination of infrastructure facility. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 165, 112474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afaynou, I.; Faraji, H.; Choukairy, K.; Djebali, R.; Rezk, H. Comprehensive Analysis and Thermo-Economic Optimization of a Hybrid Phase Change Material-Based Heat Sink for Electronics Cooling. Heat Transf. 2025, 54, 3754–3774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Dai, J.; Zhai, C.; Wang, J.; Tian, Y.; Sun, W. A review on lithium-ion battery modeling from mechanism-based and data-driven perspectives. Processes 2024, 12, 1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Wang, X.; Negnevitsky, M.; Zhang, H. A review of air-cooling battery thermal management systems for electric and hybrid electric vehicles. J. Power Sources 2021, 501, 230001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, Y. Thermal performance enhancement of phase change material heat sinks for thermal management of electronic devices under constant and intermittent power loads. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2021, 181, 121899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Yuan, W.; Chen, X.; Liao, H. Flexible, nonflammable, highly conductive and high-safety double cross-linked poly(ionic liquid) as quasi-solid electrolyte for high performance lithium-ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 421, 130000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Liang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Jiao, S.; Zhuo, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J.N.; Yu, X. Unveiling the high-valence oxygen degradation across the delithiated cathode surface. Angew. Chem. 2023, 135, e202215131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Hou, D.; Jiang, J.; Fan, Y.; Li, X.; Li, T.; Ma, Z.; Ben, H.; Xiong, H. Elucidating the synergic effect in nanoscale MoS2/TiO2 heterointerface for Na-ion storage. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2204837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spampinato, C.; Valastro, S.; Calogero, G.; Smecca, E.; Mannino, G.; Arena, V.; Balestrini, R.; Sillo, F.; Ciná, L.; La Magna, A.; et al. Improved radicchio seedling growth under CsPbI3 perovskite rooftop in a laboratory-scale greenhouse for Agrivoltaics application. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Type of Work Material | Specific Heat Capacity (J kg−1 K−1) | Thermal Conductivity (W m−1 K−1) | Applicable Scenarios | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water—Glycol solution | Approximately 3400–4200 | Approximately 0.5–0.6 | Electric vehicles, low temperature environment | [8] |

| mineral oil | Approximately 1600–2000 | Approximately 0.15–0.25 | Scenarios with high security requirements | [9] |

| Fluoride | Approximately 1000–1500 | Approximately 0.1–0.15 | Immersion cooling systems | [10] |

| Category | Cooling Principle |

|---|---|

| Single-phase liquid cooling | Heat is transferred by the sensible heat of the liquid without phase change; coolant circulates through channels or cold plates to remove heat. |

| Two-phase liquid cooling | Utilizes liquid–vapor phase change to transfer latent heat efficiently under high heat flux. |

| Indirect-contact liquid cooling | Heat is conducted from the cell to an intermediate solid, then convected to the circulating liquid coolant. |

| Direct-contact liquid cooling | Coolant directly contacts the battery surface, dissipating heat through convection; includes immersion and spray cooling. |

| Hybrid cooling | Combines multiple mechanisms to enhance transient control and thermal uniformity. |

| Microchannel cooling | Employs forced convection in micro- or mini-channels to increase heat transfer area and improve local temperature control. |

| Cooling Technology | Coolant Type | Max Temperature (°C) | ΔT (°C) | Energy Consumption (W) | Cooling Efficiency (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air Cooling | Air | 55 | 10 | 30 | 60 | [13] |

| PCM Hybrid | PCM + Air | 48 | 7 | 25 | 72 | [14] |

| Liquid Cooling | Water-Glycol | 42 | 5 | 20 | 80 | [15] |

| Nanofluid Cooling | Al2O3/EG | 38 | 3 | 18 | 85 | [16] |

| Direct Immersion | Dielectric fluid | 37 | 3.5 | 15 | 88 | [17] |

| Cooling Strategy | Coolant/Material | Max Temperature (°C) | ΔT (°C) | Energy Consumption (W) | Cooling Efficiency (%) | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air Cooling | Forced Air | 55 | 10 | 30 | 60 | Simple structure, low cost |

| Single-Phase Liquid Cooling | Water–Glycol | 42 | 5 | 20 | 80 | High thermal conductivity, good uniformity |

| PCM + Nanofluid | PCM + Al2O3/EG nanofluid | 36 | 2 | 18–20 | 90–92 | Lower peak temperature, enhanced stability, transient buffering |

| Nanofluid HFE-7000 | Dielectric fluid + nanoparticles | 35 | ≤3 | 15–18 | >92 | Excellent safety, fast transient cooling |

| Type | Advantage | Shortcoming | Scope of Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid cooling plate | Cooling effect is good, various forms, low cost | The structure of the system is complex and the mass is large | All applicable |

| Liquid cooling pipe | Low system mass | T system structure is not compact enough | Cylindrical cell |

| Type | Advantage | Shortcoming | Scope of Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| submerged | Good cooling effect, simple structure, high heat transfer efficiency | High system mass | All applicable |

| Non-submerged | The cooling effect is good, the heat transfer is sufficient, and the system mass is small | More complex system | Cylindrical cell |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jiang, W.; Tan, C.; Su, E.; Lu, J.; Shi, H.; Wang, Y.; Song, J.; Wang, K. Advanced Electronic Materials for Liquid Thermal Management of Lithium-Ion Batteries: Mechanisms, Materials and Future Development Directions. Coatings 2026, 16, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010059

Jiang W, Tan C, Su E, Lu J, Shi H, Wang Y, Song J, Wang K. Advanced Electronic Materials for Liquid Thermal Management of Lithium-Ion Batteries: Mechanisms, Materials and Future Development Directions. Coatings. 2026; 16(1):59. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010059

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Wen, Chengcong Tan, Enqian Su, Jinye Lu, Honglei Shi, Yue Wang, Jilong Song, and Kai Wang. 2026. "Advanced Electronic Materials for Liquid Thermal Management of Lithium-Ion Batteries: Mechanisms, Materials and Future Development Directions" Coatings 16, no. 1: 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010059

APA StyleJiang, W., Tan, C., Su, E., Lu, J., Shi, H., Wang, Y., Song, J., & Wang, K. (2026). Advanced Electronic Materials for Liquid Thermal Management of Lithium-Ion Batteries: Mechanisms, Materials and Future Development Directions. Coatings, 16(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings16010059