Abstract

Reliable bonding between zirconia and PEEK surfaces is crucial for ensuring the long-term success of hybrid prosthetic restorations. This study aimed to evaluate the tensile bond strength of zirconia–PEEK specimens prepared using different primer strategies to determine the most effective adhesive protocol. One hundred bonded specimens were divided into four groups (n = 25): control (no primer), zirconia primer (MKZ Primer), PEEK primer (Visio.link), and dual primer application. Specimens underwent sandblasting with 110 µm Al2O3 particles at 2 bar pressure for 15 s, and the PEEK primer was light-cured using a Valo Grand LED curing unit (1000 mW/cm2, 90 s). All samples were bonded using the same universal adhesive and resin cement, and tensile bond strength was measured with a micro-tensile testing device. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD test (α = 0.05). The mean bond strengths were 12.83 MPa (control), 15.05 MPa (zirconia primer), 90.50 MPa (PEEK primer), and 102.09 MPa (dual primer). Application of PEEK primer significantly enhanced adhesion compared to zirconia primer or control (p < 0.001), while dual primer use yielded the highest values, indicating a synergistic effect. These findings suggest that surface-specific priming of both zirconia and PEEK surfaces effectively improves polymer–ceramic bonding performance and may contribute to the clinical durability of hybrid prosthetic restorations.

1. Introduction

Implantology represents one of the most commonly adopted therapeutic approaches for the restoration of missing dentition in modern dentistry. Over time, the focus of implantology has shifted from primarily surgical approaches to prosthetic-driven planning, and more recently, to biologically oriented strategies that prioritize esthetic outcomes [1]. With the increasing demand for esthetics, significant changes have also occurred in the materials used for implant suprastructures.

In conventional implant systems, titanium abutments covered with all-ceramic crowns have been widely used; however, these restorations may cause a gray discoloration of the peri-implant mucosa, referred to as the “titanium hue,” and recession of the soft tissues may lead to exposure of metal surfaces, thereby compromising esthetics [2,3]. Consequently, the demand for metal-free, tooth-colored alternative abutment materials has increased, leading to the development of zirconia abutments, which, owing to their translucency, provide favorable esthetic outcomes. In clinical applications, zirconia has been shown to enhance the natural appearance of peri-implant tissues, producing highly satisfactory esthetic results [4].

Recent studies have explored hybrid prosthetic designs that integrate zirconia and PEEK to combine the superior esthetics and hardness of ceramics with the favorable biomechanical properties of high-performance polymers. This zirconia–PEEK combination has been proposed as a promising alternative for implant-supported bars and suprastructures, reducing stress transmission to peri-implant tissues while maintaining high esthetic quality. Moreover, PEEK frameworks veneered with zirconia or ceramic layers have been shown to provide superior shock absorption, favorable stress distribution, and improved marginal adaptation compared with monolithic ceramic restorations [5,6]. Consequently, the zirconia–PEEK hybrid approach represents a contemporary strategy aimed at achieving a balance between mechanical resilience and esthetic performance in fixed implant prosthodontics.

Zirconia stands out as a material due to its high mechanical strength, biocompatibility, and long-term clinical success [7,8]. Nevertheless, its high cost and brittleness limit its use [9]. To overcome these drawbacks, the need for more economical and easily processable materials has brought polyetheretherketone (PEEK) into prominence as an alternative in implant prosthodontics.

Beyond its established use in biomedical and dental applications, zirconia (ZrO2) has increasingly been recognized as a technologically critical advanced ceramic across diverse research fields due to its phase-dependent mechanical behavior, high thermal stability, and complex surface chemistry. Recent investigations have demonstrated that zirconia exhibits pronounced sensitivity to external stimuli such as temperature and irradiation, which can induce polymorphic transformations and alter its microstructural stability and surface reactivity [10]. These transformation-related phenomena are closely associated with variations in surface energy, defect formation, and interfacial characteristics, all of which are key parameters influencing material–material interactions.

In parallel, contemporary studies on doped and irradiated zirconia ceramics have revealed that modifications at the lattice and defect level can significantly affect the electronic and physicochemical structure of zirconia surfaces. Collectively, these findings indicate that zirconia cannot be regarded as a chemically inert substrate in practical applications; rather, its interfacial behavior is highly surface-sensitive and strongly dependent on processing history and surface condition [11]. From an adhesion science perspective, this intrinsic complexity poses a fundamental challenge when zirconia is combined with polymeric materials, thereby emphasizing the necessity for carefully designed surface-conditioning and primer-based strategies to achieve reliable and durable bonding at polymer-ceramic interfaces.

On the other hand, PEEK, a high-performance polymer, has gained increasing attention as an implant abutment material due to its low density, biocompatibility, and elastic modulus which closely resembles that of alveolar bone [12]. In addition, its compatibility with CAD/CAM systems allows for easy adaptation to various implant platforms. However, PEEK’s low surface energy makes it difficult to achieve a strong and durable adhesive bond with resin-based cements [13].

To overcome this bonding challenge, various surface modification techniques and primers have been developed. The literature reports that surface treatments such as sandblasting, acid etching, plasma treatment, laser roughening, and primers containing methyl methacrylate (MMA) can enhance adhesive bonding to PEEK [14,15]. Luo et al. emphasized that although PEEK is inherently bio-inert, its bond strength can be improved through sandblasting, acid etching, plasma application, and adhesive systems [16]. In some cases, particularly when MMA-based adhesive systems are used, direct chemical bonds can be established on PEEK surfaces, eliminating the need for additional primers [17].

Similarly, zirconia surfaces are chemically inert and do not respond well to conventional silane-based bonding strategies. Therefore, the combination of primers containing phosphate groups (e.g., 10-MDP (10-methacryloyloxydecyl dihydrogen phosphate)) with mechanical pre-treatments such as sandblasting has been recommended. A study demonstrated that, in the absence of primer application, bond strength between zirconia and self-adhesive resin cements remained low, whereas MDP-containing primers and adhesives significantly improved adhesion [18]. Likewise, combining sandblasting with primer application is considered a reliable method for achieving strong and durable adhesive bonds at the zirconia–resin interface.

From a clinical perspective, one important issue regarding PEEK surfaces is their susceptibility to contamination after primer application. Contact of the primed surface with saliva or blood can negatively influence bonding performance [19]. Therefore, it is recommended that primer application be performed immediately before cementation. Additionally, certain PEEK primers require polymerization using specialized light-curing units with a wavelength of 375–400 nm, which introduces additional clinical costs [20].

In summary, zirconia–PEEK hybrid prostheses present a high potential to combine esthetics and durability. However, enhancing the bond strength of these materials requires appropriate surface treatments (e.g., sandblasting) and primer selection (e.g., MDP-containing primers or system-specific adhesives such as Visio.link).

Although numerous studies have examined adhesion protocols for zirconia or PEEK individually, comparative evaluations of surface-specific priming strategies on zirconia–PEEK hybrid assemblies remain limited. To date, no study has systematically assessed four primer configurations including MKZ Primer, Visio.link, and their combined application; within a unified micro-tensile testing framework. The present work therefore provides a structured, side-by-side assessment of primer-dependent adhesive behavior on both substrates, offering new insights into polymer–ceramic interface optimization. The aim of this study was to compare the tensile bond strength of zirconia–PEEK blocks with and without primer application and to determine the most effective surface treatment protocol for maximizing bond strength in these hybrid systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This in vitro experimental study was designed to evaluate the bond strength between polyetheretherketone (PEEK) and zirconia surfaces. The null hypothesis of this study predicted that applying primer to zirconia and/or PEEK surfaces would not produce a statistically significant increase in tensile bond strength compared to a control group using only universal adhesive and resin cement. As this was an in vitro study using no human or animal subjects, ethical approval was not required. The effects of surface primer applications and adhesive protocols on bond performance were investigated in this context. The study consisted of four experimental groups, each with 25 specimens (n = 25; sample size was determined based on a power analysis (α = 0.05, power = 0.80) referring to previous studies reporting similar group sizes), and a total of 100 bonded specimens were evaluated.

2.2. Materials

The materials employed in the study are summarized in Table 1 with brand names, manufacturers, and countries of origin.

Table 1.

Materials and equipment used in the study.

2.3. Specimen Preparation

Each material block (PEEK and zirconia) was sectioned into 3 × 3 × 2 mm prisms using CNC milling systems. The surfaces were polished sequentially with 600, 800, and 1200-grit silicon carbide papers, cleaned in distilled water using an ultrasonic bath for 5 min, and air-dried. The dimensions of the zirconia and PEEK blocks (3 × 3 × 2 mm) were selected to ensure compatibility with the micro-tensile testing device and to maintain uniform stress distribution across the bonded interface, in accordance with previous studies using small, standardized loading surfaces. A standardized polishing sequence (600-, 800-, and 1200-grit SiC papers) was performed to remove machining irregularities and create a consistent baseline surface prior to sandblasting and primer application. This protocol minimized variability between specimens and ensured that the observed differences in bond strength were attributable to the experimental treatments rather than inconsistencies in surface preparation.

2.4. Experimental Groups

Specimens were randomly divided into four groups:

- Group A (Control group):

No primer application or sandblasting.

Bonding performed using 3M RelyX Ultimate resin cement followed by the application of RelyX Ultimate resin cement (3M ESPE, Seefeld, Germany), according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

- Group B (Zirconia primer group):

Zirconia surface sandblasted with 110 µm Al2O3 particles at 2 bar for 15 s.

MKZ Primer applied to the zirconia surface.

No primer applied to PEEK.

Bonding completed with Signum Universal Bond(Kulzer GmbH, Hanau, Germany) followed by the application of RelyX Ultimate resin cement (3M ESPE, Seefeld, Germany), according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

- Group C (PEEK primer group):

PEEK surface sandblasted under the same conditions.

Visio.link applied to the PEEK surface.

No primer applied to zirconia.

Bonding completed with Signum Universal Bond (Kulzer GmbH, Hanau, Germany) followed by the application of RelyX Ultimate resin cement (3M ESPE, Seefeld, Germany), according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

- Group D (Dual primer group):

Both zirconia and PEEK surfaces sandblasted.

MKZ Primer applied to zirconia, Visio.link applied to PEEK.

Bonding completed with Signum Universal Bond (Kulzer GmbH, Hanau, Germany) followed by the application of RelyX Ultimate resin cement (3M ESPE, Seefeld, Germany), according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

2.5. Surface Treatments

2.5.1. Sandblasting

Specimens were sandblasted with 110 µm Al2O3 particles from a 10 mm distance at 2 bar pressure for 15 s, ultrasonically cleaned in distilled water for 3 min, and air-dried. Airborne-particle abrasion was applied only in primer-treated groups, as sandblasting is specified as a mandatory surface-conditioning step in the manufacturers’ instructions for use (IFU) for both MKZ Primer and Visio.link, whereas it is not defined as a required prerequisite for bonding when using the universal adhesive system alone.

2.5.2. Primer Application

- MKZ Primer: Applied to the sandblasted zirconia surface with a microbrush, left for 60 s, and gently air-dried.

- Visio.link: Applied to the sandblasted PEEK surface in a thin layer, then polymerized with a Valo Grand LED curing light (1000 mW/cm2, 90 s), which provides a spectral output of approximately 385–515 nm. This spectral range overlaps with the wavelength window specified in the Visio.link manufacturer’s instructions for use (370–400 nm), and the exposure time of 90 s was applied strictly in accordance with the IFU.

2.5.3. Universal Adhesive Protocol

In all groups, Signum Universal Bond was applied to both zirconia and PEEK surfaces according to manufacturer instructions and light-cured for 20 s. RelyX Ultimate resin cement was then applied and light-cured.

2.6. Bonding and Polymerization

PEEK blocks were bonded to zirconia blocks using resin cement under constant pressure (1 N). The constant pressure of 1 N was applied using a custom-fabricated vertical loading device consisting of a fixed base and a weighted lever system, designed to deliver uniform compressive force during bonding. This setup ensured consistent cement film thickness and eliminated manual variability between specimens. Cement layers were polymerized with both light-curing (40 s) and chemical polymerization in accordance with manufacturer instructions. Following cementation and removal of excess cement, the bonded interfaces were visually inspected under magnification to confirm uniformity of the bonding area across all specimens. No variation in bonded interface area was observed. Cement thickness was controlled by applying a constant seating force during bonding; however, cement film thickness was not measured individually.

All bonding and curing procedures were performed under controlled laboratory conditions. The ambient temperature was maintained at 22–24 °C, with a relative humidity of 45–55% throughout the specimen preparation process. To ensure consistent polymerization, all light-curing steps were carried out in a closed workstation without airflow interference, using a single LED curing unit (Valo Grand, 1000 mW/cm2). These standardized environmental conditions minimized variability and ensured uniform adhesive curing across all experimental groups. The experimental workflow consisted of sequential surface preparation, bonding, and polymerization procedures. Following completion of bonding and polymerization, all specimens were stored under controlled laboratory conditions (22–24 °C, relative humidity 45–55%) for 24 h prior to tensile bond strength testing. No water storage or artificial aging protocol was applied, as the experimental design focused on the evaluation of initial bond strength.

2.7. Tensile Strength Testing

Bond strength was measured using a Dillon Quantrol Micro Tensile Tester (Dillon/Qualitest Inc., Largo, FL, USA). Specimens were fixed to the tensile unit using special jigs, and load was applied at 1 mm/min until bond failure occurred. Maximum load was recorded in Newtons. Tensile bond strength (MPa) was calculated by dividing the maximum load at failure (N) by the bonded interface area (mm2). The bonded interface area was standardized to 3 × 2 mm (6 mm2) for all specimens.

2.8. Failure Mode Analysis

After tensile testing, the debonded interfaces of all fractured specimens were examined under a stereomicroscope (Leica MZ12, Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany) at 16× magnification to determine the failure modes. Each specimen surface was carefully inspected and categorized as adhesive, cohesive, or mixed according to the fracture pattern observed.

Adhesive failure was defined as separation occurring strictly at the interface between the zirconia and PEEK substrates, indicating insufficient interfacial bonding. Cohesive failure was identified when fracture occurred within the resin cement layer or within one of the substrate materials, indicating higher interfacial adhesion strength than internal material cohesion. Mixed failure represented a combination of adhesive and cohesive characteristics, suggesting partial continuity of the bonded interface. All specimens were analyzed under standardized illumination conditions, and representative micrographs were captured to document typical failure appearances within each experimental group.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS v25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Normal distribution was assessed with the Shapiro–Wilk test. Group comparisons were performed with one-way ANOVA, and post hoc Tukey HSD tests were applied for pairwise comparisons. Significance level was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

In this study, the effects of different primer applications on the bond strength between zirconia and PEEK surfaces were evaluated. Four experimental groups, each containing 25 samples, were established: Group A (control, primer-free), Group B (primer applied only to the zirconia surface), Group C (primer applied only to the PEEK surface), and Group D (dual primer application). Bond strength measurements were analyzed using SPSS v25.0. Distribution characteristics were evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test to confirm normal distribution, and parametric methods such as one-way ANOVA and Tukey HSD post hoc tests were preferred. The significance level was set at α = 0.05. The power of the test exceeded 0.80 for all comparisons, confirming the adequacy of the sample size (n = 25 per group).

The one-way ANOVA analysis revealed statistically significant differences between the groups whose bond strengths were measured (F = 572.44, p < 0.001). Post hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test further clarified these differences. No statistically significant difference was observed between the control group (Group A) and the group with primer applied to the zirconia surface (Group B) (p = 0.861). This indicates that the application of primer to the zirconia surface alone does not significantly increase adhesion. In contrast, both the group treated with a single primer on the PEEK surface (Group C) and the group treated with a dual primer (Group D) exhibited higher bond strength values compared to Groups A and B (p < 0.001 for all pairwise comparisons). Furthermore, Group D showed a significantly higher average bond strength than Group C (p < 0.001). This confirms that although the application of primer on the PEEK surface significantly increased adhesion, the combination of primer applied on both substrates on the double surface yielded the superior bonding performance.

The mean tensile bond strength values for each group are presented in Table 2. In Group A (control group), the average tensile bond strength was measured as 12.83 ± 4.63 MPa, and this group showed the lowest performance among all groups. In Group B, where primer was applied only to the zirconia surface, the average bond strength was measured as 15.05 ± 4.79 MPa, showing a slight increase; however, this difference was not statistically significant compared to the control group (p = 0.861). This result indicates that the primer applied to the zirconia surface alone does not effectively increase adhesion. In contrast, Group C, where primer (Visio.link) was applied only to the PEEK surface, showed significantly higher bond strength with an average value of 90.50 ± 12.16 MPa, representing a statistically significant increase compared to both Group A and Group B (p < 0.001). The highest bond strength values were measured in Group D, where primer was applied to both surfaces (102.09 ± 14.37 MPa). The significantly better performance of this group compared to all other groups (p < 0.001 in all pairwise comparisons) confirms that the combined use of primers on zirconia and PEEK surfaces creates a synergistic effect.

Table 2.

Mean Tensile Bond Strength Values for Each Experimental Group.

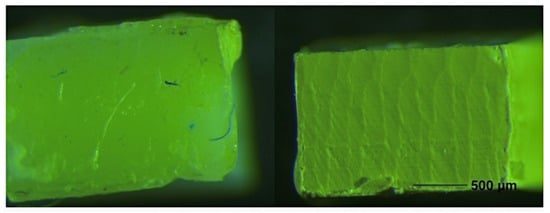

The stereomicroscopic evaluation of fractured specimens revealed a clear correlation between the applied surface treatment protocols and the observed failure modes. The distribution of failure types observed in each experimental group is listed in Table 3. Groups A and B predominantly exhibited adhesive failures, indicating insufficient chemical bonding at the zirconia–PEEK interface. Representative adhesive failures are illustrated in Figure 1. Specifically, in Group B, failures were classified as 76% adhesive, showing that zirconia primer application alone provided only a limited improvement in interfacial bonding.

Table 3.

Distribution of Failure Modes Among Experimental Groups.

Figure 1.

Representative stereomicroscopic image showing adhesive failure mode of debonded zirconia–PEEK specimens (Leica MZ12, 16× magnification; scale bar = 500 µm).

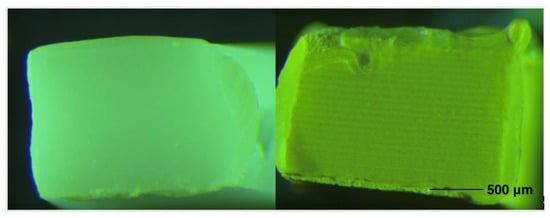

In contrast, the PEEK primer group (Group C) demonstrated a significant shift toward internal failures, with 52% cohesive, reflecting the superior chemical interaction achieved through the application of Visio.link on the PEEK surface. Cohesive failure patterns are shown in Figure 2. The dual primer group (Group D) exhibited the most favorable distribution pattern, dominated by cohesive and mixed failures and minimal adhesive separation, confirming that simultaneous priming of both zirconia and PEEK surfaces effectively enhanced interfacial integrity and bond durability. Mixed failure characteristics are presented in Figure 3. These findings are consistent with the high tensile bond strength values obtained in Groups C and D, supporting the synergistic effect of dual primer application.

Figure 2.

Representative stereomicroscopic image showing cohesive failure mode of debonded zirconia–PEEK specimens (Leica MZ12, 16× magnification; scale bar = 500 µm).

Figure 3.

Representative stereomicroscopic image showing mixed failure mode of debonded zirconia–PEEK specimens (Leica MZ12, 16× magnification; scale bar = 500 µm).

4. Discussion

The results of this study show that different primer application strategies have marked effects on the bond strength between zirconia and PEEK surfaces. While the primer applied to the zirconia surface alone increased the bond strength to a limited extent, the primer applied to the PEEK surface significantly improved adhesion. The highest values were observed when primer was applied to both surfaces, proving a synergistic effect.

The similarity between Group A (control) and Group B (primer application only on the zirconia surface) indicates that zirconia primers alone do not provide a sharp increase in chemical bonding. This is consistent with the literature highlighting zirconia’s inert surface structure and low surface energy as limiting factors [15]. In contrast, the striking improvement in Group C emphasizes the positive effect of Visio.link on adhesion to PEEK surfaces. This result is parallel to findings from various in vitro studies analyzing adhesive performance on bio-inert polymer surfaces, which indicate that combining mechanical surface roughening with chemical surface treatments significantly increases the bondability of PEEK [16]. The significantly increased bond strength performance in Group D indicates the synergistic benefit of dual primer use, reinforcing the view that primer use on both zirconia and PEEK surfaces directly impacts maximum clinical success [21].

The PEEK polymer structure is known for its weak bonding to other material surfaces due to its material properties stemming from low surface energy and chemical inertness [11]. Standard restorative adhesive application methods are often insufficient when applied to bio-inert substrates such as PEEK, requiring the use of combined surface adhesion improvement approaches, including mechanical methods (e.g., air particle abrasion) in addition to chemical primer agents. Visio.link, used in this study, contains methacrylate groups that chemically bond with the polymer matrix and enhance resin cement interaction. These results are consistent with previous studies confirming the efficacy of Visio.link [17].

Previous studies have confirmed that primers containing MDP improve zirconia surface adhesion. However, meta-analyses emphasize that the effectiveness of these primers may decrease with long-term aging [15,22].

The results of Group B, which did not show a significant improvement in bond strength compared to the control group, support these findings and indicate that zirconia primers should be used in combination with adhesives and resin cements. The most notable finding was the superior performance of the dual primer application in Group D, which combined mechanical roughening, chemical modification, and adhesive protocols. This synergistic effect is critical for the goal of increasing long-term stability in hybrid prostheses [18]. Sandblasting enhances micromechanical retention by creating micro-retentive asperities and increasing surface energy, thereby improving adhesive wetting and resin infiltration. However, mechanical interlocking alone is insufficient to ensure durable and moisture-resistant bonds on chemically inert substrates such as PEEK and tetragonal zirconia polycrystals. As detailed in Table 4, Visio.link contains methacrylate-based monomers including methyl methacrylate (MMA) and pentaerythritol triacrylate (PETIA), along with photoinitiators enabling free-radical polymerization. This composition facilitates the formation of an interpenetrating polymer network and covalent linkage to the PEEK matrix through carbon–carbon double-bond conversion during curing. In contrast, MKZ Primer incorporates phosphate-based functional monomers, which rely on chemisorption mechanisms forming stable phosphate–oxide (P–O–Zr) bonds at zirconia surfaces, contributing to improved interfacial durability and resistance to hydrolysis under thermal and moisture stress. When these chemical mechanisms operate in combination, as achieved with dual-primer application, the synergy between micromechanical retention, methacrylate-mediated copolymerization on PEEK and phosphate-based chemisorption on zirconia reinforces the adhesive interface, bilaterally providing a mechanistic explanation for the superior bond strength observed in the dual-primer group compared with single-surface treatment [15,17].

Table 4.

Chemical composition and primary functional mechanism of primers used.

Beyond the individual chemical pathways activated by each primer, the dual-primer protocol enables the formation of a multilayered interfacial architecture that cannot be achieved through single-surface conditioning. Sequential activation of PEEK and zirconia generates two chemically distinct yet mechanically compatible adhesion zones that converge within the resin cement layer. On the PEEK side, the methacrylate-rich network produced by Visio.link promotes deeper monomer diffusion and increased crosslink density, resulting in a compliant, energy-dissipating polymer interface [15,17]. On the zirconia side, phosphate-based functional monomers in MKZ Primer establish rigid and hydrolytically stable P–O–Zr chemisorption bonds reinforcing interfacial durability under moisture and thermal stress [23,24]. When these two interfacial regions develop concurrently, a graded transition zone is created that enables more homogeneous stress distribution across the polymer–ceramic assembly, reducing localized stress concentrations and suppressing crack initiation at either substrate [17,23]. This multilayered surface-specific activation provides a continuous interfacial pathway that integrates micromechanical retention, covalent copolymerization and phosphate-oxide chemisorption thereby enhancing the load-bearing capacity of the assembly. Such cooperative interfacial behavior offers a higher-order mechanistic explanation for the synergistic improvement in tensile performance observed in the dual-primer group, extending beyond the additive contributions of the individual primers [15,24].

Similar findings were reported by Pavanan et al. [23], who evaluated the bond strength of zirconia crowns bonded to PEEK abutments using different resin cements with and without primer application. This study published results supporting that bond strength measurements were quite low when no primer was used, while methyl methacrylate-based primers significantly improved adhesion. Similarly, studies demonstrated that the combined use of mechanical roughening and dual primer systems enhances the interface stability between zirconia and high-performance polymers, specifically under thermomechanical stress [23]. Conversely, Shen et al. reported that zirconia surfaces treated with only a single chemical primer exhibited substantially lower bond strength and reduced aging stability, while the combination of mechanical roughening and MDP-containing primers produced markedly stronger and more durable adhesive interfaces [25].

Some findings from studies conducted by Luo et al. [16] confirmed that the surface energy and microstructure of PEEK are key determinants of bonding performance and that methacrylate-containing primers enhance surface wettability, thereby facilitating polymer interlocking. The classic study by Kern and Wegner [26] highlighted the role of phosphate monomers in supporting durable zirconia–resin bonding years ago, shedding light on current studies related to the subject; this finding parallels the observation of improved adhesion when MDP-based zirconia primers are used in combination with PEEK primers. All of these studies emphasize that simultaneous surface primer application on both zirconia and PEEK substrates produces a synergistic effect, optimizes the chemical and micromechanical integrity of the adhesive interface, and supports the long-term clinical survival rates of hybrid prosthetic restorations.

The present failure mode findings are consistent with contemporary literature. Studies have reported that, in the absence of surface pretreatment or primer application, PEEK substrates typically exhibit predominantly adhesive failures accompanied by low bond strength values [15]. Conversely, when methacrylate-containing primers such as Visio.link are combined with airborne-particle abrasion, chemical interaction at the PEEK interface is significantly reinforced, shifting the failure pattern toward mixed/cohesive modes and yielding markedly higher tensile and shear bond strength values [15]. On the zirconia side, the use of 10-MDP–based primers has been shown to convert predominantly adhesive fractures in untreated control groups into mixed or cohesive failures, indicating improved interfacial integrity despite zirconia’s inherent surface inertness [15,18].

It should nevertheless be noted that recent literature consistently reports enhanced zirconia bonding when airborne-particle abrasion is combined with MDP-containing primers; however, the present study did not demonstrate a significant improvement in the zirconia-only primer group. This outcome may be attributed to the high sensitivity of MDP-mediated chemisorption to surface hydroxylation and energy changes, along with variations in monomer concentration and solvent composition among commercial primers, all of which can influence phosphate–zirconia interaction strength [23,26]. Evidence further indicates that the principal contribution of MDP is associated with improved long-term hydrothermal stability rather than immediate tensile performance, with differences becoming more pronounced after artificial aging procedures such as thermocycling [22,25]. Because no aging simulation or spectroscopic verification was included in the present study, the full functional effect of MDP may not have been reflected in the initial tensile bond strength values. Additionally, the functional monomers present in the universal adhesive applied to all groups may have partially masked the incremental benefit of the zirconia primer. Collectively, these factors provide a plausible explanation for the limited improvement observed in the zirconia-only primer group and underscore the importance of integrating surface chemistry analysis and aging protocols when evaluating zirconia bonding effectiveness [24].

From a complementary mechanistic perspective, the absence of a statistically significant increase in bond strength in the zirconia-only primer group may also be explained by a saturation or ceiling effect at the zirconia surface. Phosphate-based functional monomers, particularly 10-methacryloyloxydecyl dihydrogen phosphate (MDP), are known to chemically interact with a finite number of reactive zirconium oxide sites through the formation of stable phosphate–oxide bonding mechanisms [27]. Once these available surface sites are occupied, the subsequent application of chemically similar phosphate-containing agents does not necessarily result in proportional improvements in immediate bond strength. Systematic analyses and experimental studies have demonstrated that, although MDP-based primers are highly effective in promoting zirconia adhesion, the simultaneous or sequential use of chemically similar phosphate-functional materials may lead to overlapping chemical interaction pathways, thereby limiting the measurable incremental benefit of additional priming steps [28]. This phenomenon, commonly described as a ceiling effect or saturation of bonding sites, has been consistently reported in zirconia bonding literature and indicates that the absence of further bond strength enhancement should not be interpreted as primer inefficacy, but rather as a consequence of surface chemistry saturation [29].

Furthermore, recent reports have demonstrated that, in PEEK-based and zirconia-composite hybrid systems, the distribution of adhesive, cohesive, and mixed failures observed under stereomicroscopy correlates directly with the measured bond strength; an increase in cohesive or mixed failures parallels enhanced adhesive performance [24]. These observations fully align with the present study’s Group C and D results, confirming that dual-primer application promotes chemical compatibility and ensures a mechanically durable adhesive interface between zirconia and PEEK substrates. Although relatively high tensile bond strength values were obtained in Groups C and D, these values should not be interpreted as direct representations of clinical intraoral stress conditions. Rather, they reflect the maximum interfacial strength achieved under controlled in vitro testing conditions with a small and well-defined bonded area and uniaxial tensile loading.

4.1. Study Limitations and Future Directions

Despite these promising results, the primary limitation of this study is its in vitro design, which does not adequately reproduce the dynamic oral environment. Thermal cycling and artificial aging simulations were not performed; thus, any clinical extrapolation of the present findings should be made with caution. In vivo, adhesive interfaces are continually exposed to variable pH, enzymatic activity, and cyclic occlusal loading, all of which may accelerate bond degradation [30]. Furthermore, only two primer systems were examined, which restricts the generalizability of the results across the broad spectrum of available adhesive strategies. Future studies should integrate aging regimens and broader material comparisons in multicenter clinical settings to confirm and extend these findings.

Although the mechanical findings demonstrate the influence of different primer application strategies on the zirconia–PEEK adhesive interface, no complementary surface analytical characterization was included. Techniques such as FTIR or XPS could provide direct evidence of interfacial chemical interactions and therefore represent a limitation of the present study. Nevertheless, the bonding mechanisms discussed were inferred based on the functional monomer compositions reported by the manufacturers and supported by previously published studies. Future investigations should integrate spectroscopic analyses to better correlate surface chemistry with adhesive durability and aging performance.

On the other hand, the present study did not include quantitative surface roughness measurements following airborne-particle abrasion, such as profilometric Ra/Rz data or SEM-based topographical analysis. Although sandblasting parameters were standardized across all primer-treated groups to ensure uniform micromechanical conditioning, the absence of roughness metrics limits the ability to distinguish the mechanical contribution of surface texturing from the chemical effects of primer application. Previous studies have shown that micromechanical retention alone is insufficient for durable bonding on zirconia or PEEK, and chemical priming remains essential for stable adhesion [12,14,17,23]. Future investigations should incorporate profilometry or SEM evaluation to better correlate surface morphology with adhesive performance.

4.2. Clinical Implications

Our findings highlight the critical role of PEEK primer application in hybrid prostheses. PEEK’s biocompatibility, dentin-like elastic modulus, and shock absorption properties make it attractive for clinical use. Moreover, the combined use of two primer systems may provide a synergistic effect, thereby improving the long-term clinical performance of restorations subjected to high occlusal stresses.

5. Conclusions

This in vitro study systematically evaluated the effects of different strategies on the bond strength between zirconia and PEEK surfaces. The results of this study rejected the null hypothesis, indicating that primer application—particularly on PEEK surfaces—significantly enhanced tensile bond strength compared with the control group.

From a clinical perspective, zirconia–PEEK combinations can provide both functional and esthetic advantages. However, long-term success depends on establishing reliable adhesive interfaces. The present results strongly suggest that dual primer application offers the most reliable strategy for maximizing bond strength, thus extending the clinical longevity of restorations, reducing complications, and enhancing patient satisfaction.

This study demonstrates the critical importance of PEEK surface modification, the limited but complementary role of zirconia primers and the superior outcomes achievable through their combined application. These findings highlight that the integration of material science and adhesive technologies constitutes a critical prerequisite for achieving predictable long-term outcomes in contemporary prosthetic dentistry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.A. and E.S.S.; Methodology, E.S.S.; Software, E.S.S.; Validation, B.A., F.G. and M.A.K.; Formal analysis, E.S.S.; Investigation, E.S.S.; Resources, B.A. and F.G.; Data curation, E.S.S.; Writing—original draft preparation, E.S.S.; Writing—review and editing, B.A., F.G. and M.A.K.; Visualization, E.S.S.; Supervision, B.A.; Project administration, B.A. and F.G.; Funding acquisition, none. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the Department of Prosthodontics, Ankara University, for providing laboratory facilities and technical support throughout the study. Special thanks are extended to Mustafa Yeşil for his valuable guidance during the experimental phase. The authors also acknowledge Bredent GmbH for generously supplying the experimental blocks and primers, particularly Kerem İbrahim Yuka and Deniz Karaağaç for facilitating communication with the company.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that this study received in-kind support (materials) from Bredent GmbH. The company was not involved in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the article, or the decision to submit it for publication. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zembic, A.; Kim, S.; Zwahlen, M.; Kelly, J.R. Systematic review of the survival rate and incidence of biologic, technical, and esthetic complications of single implant abutments supporting fixed prostheses. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Implant. 2014, 29, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Kanno, T.; Milleding, P.; Ortengren, U. Zirconia as a dental implant abutment material: A systematic review. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2010, 23, 299–309. [Google Scholar]

- Linkevicius, T.; Apse, P. Influence of abutment material on stability of peri-implant tissues: A systematic review. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Implant. 2008, 23, 449–456. [Google Scholar]

- Sailer, I.; Philipp, A.; Zembic, A.; Pjetursson, B.E.; Hämmerle, C.H.F.; Zwahlen, M. A systematic review of the performance of ceramic and metal implant abutments supporting fixed implant reconstructions. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2009, 20, 4–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwitalla, A.D.; Müller, W.D. PEEK dental implants: A review of the literature. J. Oral Implant. 2017, 39, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldatovic, D.M.; Liebermann, A.; Huth, K.C.; Stawarczyk, B. Fracture load of different veneered and implant-supported 4-unit cantilever PEEK fixed dental prostheses. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2022, 129, 105173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manicone, P.F.; Rossi Iommetti, P.; Raffaelli, L. An overview of zirconia ceramics: Basic properties and clinical applications. J. Dent. 2007, 35, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreiotelli, M.; Wenz, H.J.; Kohal, R.J. Are ceramic implants a viable alternative to titanium implants? A systematic literature review. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2009, 20, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denry, I.; Kelly, J.R. State of the art of zirconia for dental applications. Dent. Mater. 2008, 24, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlovskiy, A.L.; Konuhova, M.; Borgekov, D.B.; Anatoli, I.P. Study of irradiation temperature effect on radiation-induced polymorphic transformation mechanisms in ZrO2 ceramics. Opt. Mater. 2024, 156, 115994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauletbekova, A.; Zvonarev, S.; Nikiforov, S.; Akilbekov, A.; Shtang, T.; Karavannova, N.; Akylbekova, A.; Ishchenko, A.; Akhmetova-Abdik, G.; Baymukhanov, Z.; et al. Luminescence Properties of ZrO2: Ti Ceramics Irradiated with Electrons and High-Energy Xe Ions. Materials 2024, 17, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stawarczyk, B.; Keul, C.; Beuer, F.; Roos, M.; Schmidlin, P.R. Tensile bond strength of veneering resins to PEEK: Impact of different adhesives. Dent. Mater. J. 2013, 32, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidlin, P.R.; Stawarczyk, B.; Wieland, M.; Attin, T.; Hämmerle, C.H.F.; Fischer, J. Effect of different surface pre-treatments and luting materials on shear bond strength to PEEK. Dent. Mater. 2010, 26, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallmann, L.; Mehl, A.; Sereno, N.; Hämmerle, C.H.F. The improvement of adhesive properties of PEEK through different pre-treatments. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012, 258, 7213–7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hata, K.; Komagata, Y.; Nagamatsu, Y.; Masaki, C.; Hosokawa, R.; Ikeda, H. Bond strength of sandblasted PEEK with dental methyl methacrylate–based cement or composite–based resin cement. Polymers 2023, 15, 1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Liu, Y.; Peng, B.; Wang, Y.; Guo, L.; Zhang, Y. Recent advances in mechanical and adhesive properties of PEEK for dental applications. Polymers 2023, 15, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stawarczyk, B.; Taufall, S.; Roos, M.; Schmidlin, P.R.; Lümkemann, N. Bonding of composite resins to PEEK: Influence of adhesive systems and air-abrasion parameters. Clin. Oral Investig. 2018, 22, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, E.J.; Shin, Y.; Park, J.W. Evaluation of the microshear bond strength of MDP-containing and non–MDP-containing self-adhesive resin cement on zirconia restoration. Oper. Dent. 2019, 44, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.C.; Yang, M.H.; Zhong, W.Y.; Zheng, Y.X.; Hong, G.; Yu, H. Optimizing resin bonding to saliva-contaminated polyetheretherketone: Comparative efficacy of cleaning methods. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, S.M. PEEK Biomaterials Handbook, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sloan, R.; Hollis, W.; Selecman, A.; Jain, V.; Versluis, A. Bond strength of lithium disilicate to polyetheretherketone. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 128, 1351–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharafeddin, F.; Shoale, S. Effects of universal and conventional MDP primers on the shear bond strength of zirconia ceramic and nanofilled composite resin. J. Dent. 2018, 19, 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Pavanan, M.; Ayyadanveettil, P.; Thavakkara, V.; Latha, N.; Saraswathy, A.; Kuruniyan, M.S. Retention strength of zirconia crowns cemented onto PEEK abutments using two different types of resin cement with or without primer application-an in vitro study. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2022, 35, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erjavec, A.K.; Črešnar, K.P.; Švab, I.; Vuherer, T.; Žigon, M.; Brunčko, M. Determination of shear bond strength between PEEK composites and veneering composites for the production of dental restorations. Materials 2023, 16, 3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, D.; Wang, H.; Shi, Y.; Su, Z.; Hannig, M.; Fu, B. The effect of surface treatments on zirconia bond strength and durability. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kern, M.; Wegner, S.M. Bonding to zirconia ceramic: Adhesion methods and their durability. Dent. Mater. 1998, 14, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, K.; Tsuo, Y.; Atsuta, M. Bonding of dual-cured resin cement to zirconia ceramic using phosphate acid ester monomer and zirconate coupler. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2006, 77, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inokoshi, M.; De Munck, J.; Minakuchi, S.; Van Meerbeek, B. Meta-analysis of bonding effectiveness to zirconia ceramics. J. Dent. Res. 2014, 93, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, M. Bonding to oxide ceramics—Laboratory testing versus clinical outcome. Dent. Mater. 2015, 31, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guess, P.C.; Att, W.; Strub, J.R. Zirconia in fixed implant prosthodontics. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2012, 14, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.