Abstract

Melamine-faced particleboards are widely used in interior applications; however, their performance is often limited by the near-surface structure, film adhesion, and edge damage that can be generated during machining and service impacts. Here, model particleboards were produced with 0%, 10%, 20%, and 40% bark content in the face layers and laminated with two melamine films (light and dark décor). Density profiles, mechanical properties (MOR, MOE, internal bond, IB), and laminate adhesion (pull-off) were determined. Edge integrity was evaluated under edge milling, quantified by cumulative tear-out length (ΣL) and the normalized damage index Li (mm/m) together with tear-out depth, and under edge impact using a 0.5 kg mass dropped from 0.20 m (damage length and indentation depth). All boards were characterized by a typical U-shaped density profile, while increasing bark share reduced surface-layer density differentiation. MOR and MOE decreased significantly only at 40% bark, whereas IB (0.54–0.74 N/mm2) remained unchanged. Bark content significantly affected adhesion (32.76% contribution), whereas film type was not a significant factor. Milling damage depended on laminate: for the dark laminate, bark-containing boards showed much higher Li (54.82–60.13 mm/m) than the reference (12.26 mm/m); for the light laminate, the lowest Li occurred at 10% bark (21.24 mm/m). Tear-out depth varied narrowly (≈0.69–1.02 mm), while impact damage length ranged from 6.96 to 8.58 mm.

1. Introduction

In the era of Industry 4.0 and 5.0, autonomous and highly automated manufacturing systems require exceptionally stable process parameters and operating conditions, as human intervention in process control is significantly reduced or eliminated. The primary objective of such advanced production environments is to ensure uninterrupted manufacturing, thereby achieving rapid economic returns on high-cost industrial investments. Among the industrial sectors that have successfully implemented numerous Industry 4.0 and 5.0 solutions is the furniture manufacturing industry [1,2,3,4]. Within this rapidly developing sector, laminated particleboards represent the most widely used material for furniture production. The scale of this industry and the sophistication of its manufacturing technologies highlight a growing need to understand the factors influencing both the processing behavior of particleboards and the performance of the applied surface coatings.

Melamine-based decorative coatings are commonly used to protect particleboards and to provide the required esthetic and functional properties. However, the integrity and durability of melamine coatings strongly depend on the mechanical support provided by the underlying substrate and its surface quality. Local heterogeneities in the surface layer of particleboards may act as stress concentrators, promoting coating cracking, chipping, or delamination during subsequent machining operations. Similar relationships between surface quality, defect formation, and coating performance have been reported for melamine-faced wood-based panels and other surface-treated composites [5,6,7].

Research in wood-based materials engineering has traditionally focused on the tool–material–quality interaction system [8]. A review of the literature indicates that extensive studies have been conducted on cutting tools and technological parameters within this framework. In contrast, the influence of material-related factors—particularly substrate heterogeneity and surface layer properties—has received considerably less attention. This research gap is particularly evident in studies addressing milling processes applied to laminated particleboards, where the integrity of coatings and the formation of defects remain insufficiently explored [5,6].

Previous investigations have identified several material-related factors that affect milling quality, including the presence of mineral contaminants such as sand in particleboards [9]. The influence of mineral content is indirect, as increased contamination accelerates tool wear, leading to reduced machining quality due to diminished cutting efficiency [10]. Other studies have demonstrated that the surface protection technology applied to particleboards significantly affects machining performance, with raw, laminated, and lacquered boards exhibiting distinct quality characteristics [11]. Furthermore, the incorporation of thermoplastics such as polypropylene or polystyrene into particleboards has been shown to extend tool life and improve machining quality [12]. In addition, density distribution and surface layer properties of particleboards have been identified as key factors influencing surface quality and defect formation during machining operations [13].

More advanced research approaches employing finite element method (FEM) simulations have demonstrated that laminate chipping defects originate from cracks initiated within the coating layer as a result of principal stresses generated by the cutting tool edge during machining. These studies indicate that the quality of machining and the integrity of the coating are primarily governed by the structural properties of the particleboard layer located directly beneath the laminate [14,15,16]. Consequently, experimental validation of these numerical findings remains an important area for further research.

In previous simulation-based studies, bark inclusions have been identified as a critical factor contributing to the insufficient mechanical support of the laminate layer. Bark represents a realistic contaminant introduced into industrial particleboard production due to the wood raw material used and may remain present in surface layers despite standard processing controls. The presence of bark has been shown to affect the mechanical performance and structural uniformity of particleboards, particularly when located near the surface [17]. Bark contains higher amounts of extractive substances that may migrate toward the surface during the hot-pressing process. These substances reduce the surface energy of the particleboard, thereby limiting the wettability and penetration of melamine resins and leading to the formation of a weaker bonding layer between the substrate and the coating [18]. While earlier research has predominantly focused on cutting processes, this study emphasizes milling operations, which play a crucial role in contemporary furniture manufacturing. In particular, preliminary milling operations performed on edge-banding machines prepare the raw edges of laminated particleboards for adhesive bonding with furniture edging materials. The quality of this process directly affects the final esthetic appearance and durability of the edge joint, which remains visible along the entire perimeter of the furniture panel and ultimately determines the overall quality of laminated particleboards.

The aim of this study was to experimentally evaluate the integrity of melamine coatings applied to particleboards containing surface bark inclusions, with particular emphasis on coating defects occurring during milling operations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Particleboards Preparation

As part of the research, three-layer particleboards were produced with a density of 650 kg/m3. The boards had dimensions of 320 × 320 mm and thicknesses of 16 mm. The adhesive content of the face layers was 10%, and for the core layer, it was 8%. The face layers constituted 35% of the board. Both the core and the surface layers were prepared from industrial wood particles; however, the surface layers differed in that varying amounts of bark particles, purchased specifically for the experiment, were added and subsequently mixed with the industrial wood particles in a laboratory mixer. The content of bark particles in the face layers of the boards was 10%, 20%, and 40%. The board pressing process was carried out on a single-shelf laboratory press (AB AK Eriksson, Mariannelund, Sweden) at 180 °C and with a maximum unit pressure of 2.5 MPa, a pressing factor of 18 s/mm (time of pressing 4.48 min). After manufacture, the boards were conditioned under laboratory conditions, specifically at 20 ± 2 °C and 65 ± 5% relative humidity, for a minimum of 7 days. A digital thermohygrometer THCA (Radiance Instruments Limited, Hong Kong, China) was used to control temperature and relative humidity.

The particleboard was coated on both sides with melamine films; two laminate variants were used, namely light and dark. These surface layers consisted of melamine films, defined as thin, paper-based materials impregnated with melamine–formaldehyde resin, which is formed by the reaction of melamine (2,4,6-triamino-1,3,5-triazine) with formaldehyde, producing methylol melamines that subsequently condense into a thermosetting polymer. The resin is synthesized under controlled alkaline conditions and elevated temperature, remaining water-soluble at an intermediate stage to enable impregnation of decorative papers prior to final curing. During hot pressing onto wood-based panels, the resin undergoes complete crosslinking, resulting in a hard, chemically resistant, and durable surface layer referred to as a melamine film [19]. The pressing of the melamine films was carried out under industrial conditions using the following technological parameters: a pressing time of 60 s, a temperature of 200 °C, and a unit pressure of 1.0 MPa. After pressing, the melamine-film-coated particleboards were conditioned under laboratory conditions, i.e., 20 ± 2 °C and 65 ± 5% relative humidity, for at least 7 days.

2.2. Mechanical and Physical Properties

Mechanical properties were evaluated using an INSTRON 3369 universal testing machine (Instron, Nortwood, MA, USA). For each panel type, each property was measured in at least 10 replicates. The modulus of rupture (MOR) and modulus of elasticity (MOE) in static bending were determined in accordance with EN 310 [20]. Due to the dimensions of the manufactured boards, the test configuration was modified relative to the standard: the support span was set to 280 mm and the specimen length to 300 mm (instead of 320 mm). The crosshead speed (loading rate) was adjusted so that failure occurred within 60 ± 30 s from the start of the test.

Tensile strength perpendicular to the plane of the board (IB) was estimated following the EN 319 [21] standard. The load increase was the same as in the MOR and MOE tests.

Board density was determined in accordance with EN 323 [22]. In addition, the density profile was measured in triplicate. Specimens (50 × 50 mm) were analyzed using a GreCon DA-X X-ray density profiler (Alfeld, Germany) with a scanning step of 0.02 mm.

Laminate adhesion to the particleboard surface was evaluated using a perpendicular pull-off test. The laminate surface at the bonding location was cleaned and, if required, lightly abraded to improve bonding repeatability. Steel dollies of diameter d (e.g., 20 mm) were bonded to the laminate using a structural adhesive and left to cure fully. To minimize shear effects and promote predominantly normal tensile loading, the bonded area was isolated by a circular scribe cut around the dolly to the laminate/substrate interface (according to the adopted procedure). Pull-off loading was then applied perpendicular to the surface using an adhesion tester (manufacturer/model), with a controlled loading rate, until failure occurred.

At least ten replicates were tested for each board variant and laminate type, and the failure mode (adhesive at the laminate–board interface, cohesive within the laminate or substrate, or mixed) was documented after testing.

2.3. SEM Observations

The joint’s quality between the manufactured three-layer particleboards and the laminate was observed using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) method. The scanning electron microscope Zeiss EVO (Oberkochen, Germany), equipped with an MA10 scanning system and a secondary electron (SE or SED) type detector, was used in the investigations. The magnification used ranged from 50× to 1000×. The higher magnification values were not possible due to the relatively low depth of field of the method and the significant roughness of the observed material surface. The electron accelerating voltage was 20 kV. The observations were made with a relatively low beam current (I Probe = 120 pA, Spot Size = 400), due to the possibility of damaging the surface of the observed material.

The surfaces of the cross-sections of the prepared samples of the manufactured three-layer particleboards were coated with a gold layer approximately 5 nm thick before observation, using a Q150R ES rotary pumped coating system by Quorum Technologies Ltd. (Laughton, UK), to improve their poor electrical conductivity.

The general view of the prepared samples on the microscopy sample holder is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The general view of the prepared samples on the microscopy sample holder.

2.4. Machining

The manufactured model boards were subjected to machining to evaluate the quality of the machined edge. Machining was performed on a three-axis CNC machining center (Busellato Jet 100, Thiene, Italy) using an end mill equipped with replaceable straight inserts (29.5 × 12 × 1.5 mm, KCR08, Germany). The spindle speed was set to 18,000 rpm, and the feed per tooth was 0.15 mm. For each machining variant, a new cutting insert was used to eliminate the influence of tool wear. The total cutting length for each variant was 3 m.

2.5. Edge Quality

The quality of machining was assessed based on laminate tear-out occurring along the machined edge. Laminate damage was evaluated by identifying defects observed along the edge after each tool pass. Each laminate defect was characterized by two parameters: defect length, measured along the cutting edge, and defect depth, measured perpendicular to the surface. Multiple defects could occur within a single tool pass; therefore, each pass was represented by a variable number of length–depth pairs. Tools that passed without visible chipping were recorded as zero defects.

For each variant, the following indicators were calculated as damage intensity: the average and total defect length (ΣL, mm), as well as the average and maximum defect depth (D_max, mm). To account for the constant assessed edge length, the following were also computed: W_L = ΣL/3. The analysis was performed for boards differing only in the bark content in the surface layers (0%, 10%, 20%, and 40%).

2.6. Impact Test Method for Laminate Edge Resistance

An original (proprietary) method was used to evaluate the resistance of laminated furniture board edges to mechanical damage. The method involves placing a rectangular laminated particleboard specimen in the test device holder at a 45° angle relative to the impact line. A steel ball with a diameter of 10 mm is positioned against the edge of the specimen. Subsequently, a mass of 500 g is released from a predetermined height, allowing it to accelerate under the influence of gravity and strike the steel ball fixed in the device. The impact transmitted through the ball produces an indentation in the edge of the tested specimen. The result of the impact test is the generated indentation, which is then subjected to further evaluation after the test is completed.

3. Results

3.1. Density Profile Results

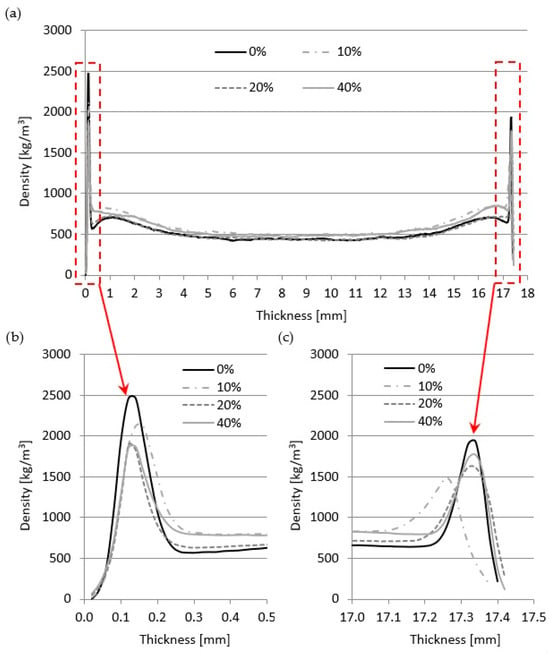

The density profile is a key indicator of the structural composition of particleboards and largely determines their suitability for specific applications. In the case of conventional particleboards, it represents a fundamental factor governing their mechanical and physical properties [23,24,25,26,27]. The manufactured model particleboards exhibited a typical U-shaped density profile (Figure 2a). Wong et al. [25] reported that the density profile is strongly correlated with the fundamental properties of particleboards, such as modulus of rupture (MOR), modulus of elasticity (MOE), and internal bond strength (IB).

Figure 2.

(a–c) Density profiles of the tested boards.

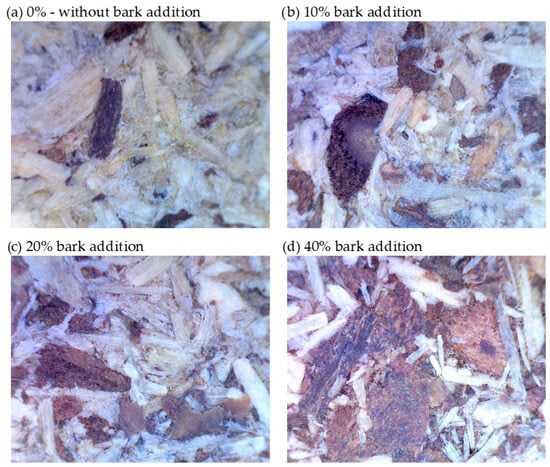

The investigated particleboards exhibited differentiated densities in the surface layers, which were covered with melamine films featuring light (Figure 2b) and dark (Figure 2c) decorative patterns. The maximum density difference of 500 kg/m3 was recorded between the boards produced with 0% and 10% bark content. An increase in the proportion of bark particles in the outer layers of the particleboards (Figure 3) resulted in a reduction in density differentiation within the surface layers of boards laminated with melamine films. This effect is associated with the lower density, higher porosity, and more irregular shape of bark particles compared to wood particles (Forest Products Laboratory 2021) [28].

Figure 3.

Surface of particleboards before pressing of melamine films (40× magnification).

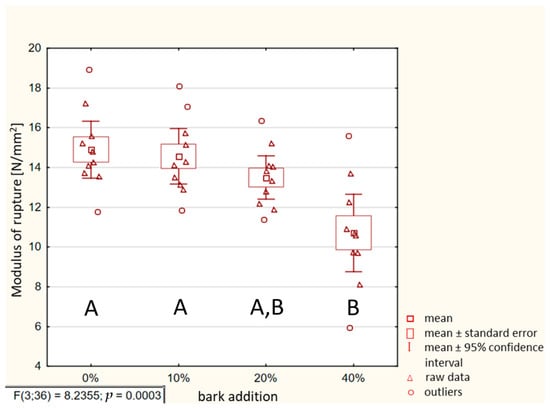

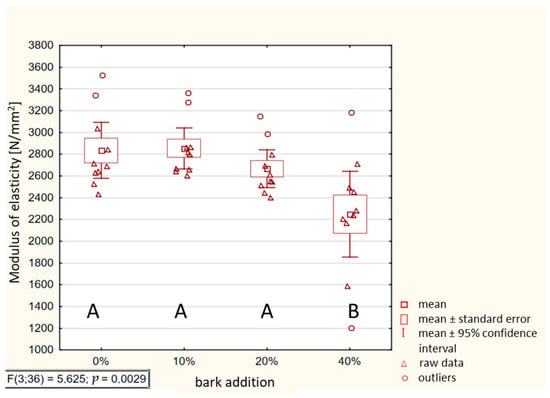

The effect of adding bark particles to the outer layers on the mechanical properties of particleboards is presented in Figure 4 and Figure 5. It can be observed that a statistically significant decrease in the modulus of rupture (MOR) and modulus of elasticity (MOE) was recorded only for boards containing 40% bark particles in the surface layers, as indicated by different homogeneous groups. For bark contents up to 20%, although a reduction in MOR and MOE values was noticeable, the differences were not statistically significant and fell within the same homogeneous group.

Figure 4.

Relationship between MOR and bark content; A, B—homogeneous groups.

Figure 5.

Relationship between MOE and bark content; A, B—homogeneous groups.

It is also worth noting that the addition of bark particles in the outer layers accounted for only 40.70% of the variation in MOR values and 31.91% in MOE values (Table 1). In both cases, the dominant influence on MOR and MOE originated from other factors not analyzed in the present study (Error), which accounted for 59.30% and 68.09% of the total variability, respectively.

Table 1.

Statistical analysis of the effect of bark content on mechanical properties.

With respect to internal bond strength (IB), ranging from 0.54 to 0.74 N/mm2, it can generally be stated that the addition of bark particles to the outer layers did not affect the strength of the particleboards. This observation is linked to the fact that all board variants showed similar density values in the core layer (Figure 2a). Consequently, the variability of IB values among the individual board variants was statistically insignificant, as indicated by the same homogeneous group classification (Table 1). The absence of a significant effect of bark particle addition was further confirmed by ANOVA results, which showed that 82.74% of the variation in IB values was attributable to other factors not considered in this study.

The primary focus of the investigation was on the adhesion of melamine films to the surface of particleboards. Pull-off tests revealed a statistically significant influence of bark presence in the outer layers on the adhesion strength of melamine films. The presence of bark particles promoted the formation of weakly densified surface zones, often containing voids and microcracks. These structural discontinuities limit the mechanical anchoring of the melamine film, which is crucial for achieving high adhesion strength. In contrast, the conducted tests did not reveal any significant influence of the type of melamine film on its adhesion to the particleboard surface.

It should be emphasized that the percentage contribution of bark content to the variation in film adhesion was 32.76%. In contrast, the type of melamine film accounted for only 0.01% of the observed variability. Additionally, the influence of other factors not included in the present study (Error) was dominant, reaching 63.20% (Table 2).

Table 2.

Statistical analysis of the pull-off test.

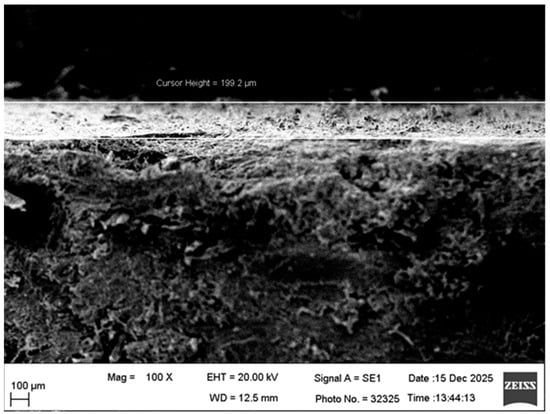

3.2. SEM Observation Results

Figure 6 presents the typical image for all observed joints between the manufactured three-layer particleboards and the laminate, for a magnification of 100×. We can observe a good joint between the surface and the laminate, without any visible defects.

Figure 6.

The observation results of the joints between the manufactured three-layer particleboards and the laminate.

Additionally, the results of the measurements on the final thickness of the used laminate were presented in the image of the investigated material’s microstructure. The measured thickness, marked by two parallel horizontal lines, is about 200 µm.

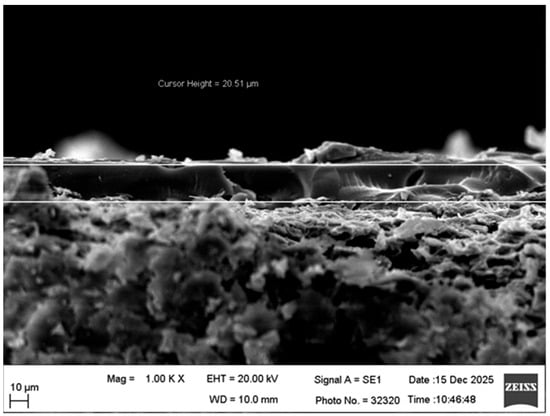

Figure 7 shows a photograph of a thin layer of the resin used in particleboard manufacturing, obtained at a magnification of 1000× and an acceleration voltage of 20 kV. This layer is observed on the laminate surface. Their thickness is about 20 µm. This layer is also without visible defects.

Figure 7.

The observation results of the resin layer on the laminate surface.

3.3. Edge Quality After Milling

In Table 3 and Table 4, the results of laminate defect measurements obtained after milling of the particleboard edges are summarized. For the dark laminate, boards containing bark exhibited a markedly higher defect intensity (54.82–60.13 mm/m) than the reference board produced from industrial wood particles (12.26 mm/m). However, increasing the bark share in the face layers did not lead to a clear monotonic trend in defect intensity along the machined edge. For the light laminate, the lowest intensity of laminate damage was observed for boards with a 10% bark addition (21.24 mm/m), indicating that the effect of bark incorporation may depend on both the laminate variant and the specific bark content.

Table 3.

Length of laminate defects generated during milling.

Table 4.

Depth of laminate defects generated during milling.

The obtained results confirm that the assessment of edge quality in laminated panels after machining should rely on more than a single indicator, because one metric (e.g., the mean defect length) does not fully reflect perceived quality nor the risk of critical, reject-driving defects. The literature on the machining of laminated wood-based panels consistently highlights that process quality is typically described using a set of parameters—commonly related to delamination and chipping, as well as surface roughness—and that “quality” should be interpreted as a multidimensional concept [5,10].

The effect of bark addition (0%–40%) on the damage pattern can be discussed in the context of studies on bark-containing particleboards, where increasing bark content is often associated with changes in mechanical performance, including internal bond strength, and the magnitude of the effect depends on particle fraction/geometry and pressing conditions [29]. From the perspective of edge machining, internal cohesion is particularly relevant because the near-edge zone is prone to crack initiation and subsequent debonding of the decorative layer under locally concentrated stresses [29].

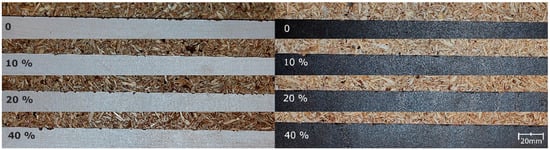

The differences observed between the “light” and “dark” laminates may also be interpreted in light of reports showing that the quality and continuity of melamine laminates, as well as their susceptibility to damage, depend on manufacturing-related variables (paper characteristics, impregnation level and resin distribution, and pressing conditions). These factors directly affect the resistance of the laminate–substrate system to crack initiation and delamination during machining. Moreover, studies focused on machining of melamine-faced boards clearly indicate that cutting parameters and tool wear significantly influence damage-related metrics (variously defined delamination/chipping indices), implying that—even for the same material—changes in cutting conditions may shift the distribution of outcomes (including maxima) toward more critical damage [10,30]. Figure 8 illustrates representative laminate damage patterns for each panel variant observed over the last 20 cm of the milling path.

Figure 8.

Representative examples of laminate damage after edge milling of the investigated particleboard variants (‘light’ laminate on the left and ‘dark’ laminate on the right).

Table 5 presents the results of edge impact resistance measured under a drop-weight configuration with a 0.5 kg load released from a height of 20 cm. The mean laminate damage length ranged from 6.96 to 8.58 mm; overall, lower damage values were generally recorded for the dark laminate. For edge damage length, both laminates showed reduced crack propagation along the edge for bark shares of 0%–20%, whereas at 40% bark, the trend reversed (longer damage lengths). A similar non-monotonic behavior was also visible for the dark laminate in terms of damage depth. Taken together, these results indicate that, under the applied test conditions, the laminate variant is a key factor governing the extent of impact-induced damage. At the same time, the effect of bark content in the face layers remains ambiguous and likely depends on competing mechanisms in the near-edge zone.

Table 5.

Mean length and depth of edge damage in laminated particleboards after impact for the investigated panel variants.

Across all bark contents (0%–40%), the dark laminate shows lower mean defect depths than the light laminate (Table 5), indicating a higher resistance of the surface layer to localized deformation. The differences between laminates may be attributed to the characteristics of resin-impregnated paper laminates (including MF-based systems), which depend on manufacturing-related variables such as paper type, impregnation and pressing conditions, and the distribution and continuity of the resin phase. According to the literature, these factors translate into layer defects and inhomogeneities that can promote the initiation of microcracks under load [31]. Consequently, the observed differences between the “light” and “dark” laminates do not necessarily arise from pigment alone, but rather from the combined effect of production parameters controlling hardness, brittleness, and energy-dissipation capability in the contact zone.

For edge damage length, the dark laminate showed reduced crack propagation along the edge at bark contents of 0%–20%; however, at 40% bark, the trend reversed, with longer damage lengths recorded for the dark laminate. This outcome suggests that at high bark shares, the failure mechanism may be governed more strongly by the properties of the near-edge zone of the board (material heterogeneity, local weakening of bonding, and fracture morphology) than by laminate behavior alone. Studies on bark-containing particleboards support this interpretation, showing that increasing bark content often adversely affects selected mechanical properties, with the magnitude and direction of the effect depending on particle geometry and distribution, as well as parameters governing the formation of the layered structure. Importantly, it has also been demonstrated that bark fraction morphology (e.g., the proportion of fibrous constituents versus outer-bark particles) can substantially modify internal bonding and mechanical response, which is particularly relevant in the edge region where stress concentrations and local structural defects facilitate crack initiation and delamination [29].

4. Conclusions

The model particleboards exhibited a typical U-shaped density profile, but increasing the bark share in the face layers progressively reduced surface-layer density differentiation, indicating a less effectively densified near-surface zone. This structural change had a limited impact on bulk mechanical performance: MOR and MOE declined significantly only at a 40% bark content, whereas internal bond strength remained unchanged, consistent with comparable core densities across variants. In contrast, the laminate–substrate interface emerged as the primary performance bottleneck. Pull-off testing revealed that the presence of bark significantly reduced film adhesion. In contrast, the melamine film variant showed no significant difference, supporting the notion that voids/microcracks and weakly densified surface regions hinder the mechanical anchorage of the film. These adhesion-controlled effects were directly reflected in edge integrity. During milling, damage assessment based on cumulative indicators (ΣL and Li) revealed laminate-dependent, non-monotonic trends: for the dark laminate, bark-containing boards showed a four- to five-fold higher damage intensity than the reference (≈54.82–60.13 vs. 12.26 mm/m), while for the light laminate, the lowest damage intensity occurred at 10% bark (21.24 mm/m). The depth of laminate defects varied within a narrow range, indicating that the occurrence and propagation of defects primarily drove differences. Under impact loading, damage lengths were generally lower for the dark laminate. In contrast, the effects of bark remained ambiguous, suggesting the presence of competing failure mechanisms in the near-edge zone at higher bark contents.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ł.A. and P.B.; methodology, Ł.A., P.B., R.A., M.B. and J.Z.; software, Ł.A. and R.A.; validation, Ł.A. and P.B.; formal analysis, Ł.A., P.B. and R.A.; investigation, Ł.A., P.B., R.A., K.S., M.B. and J.Z.; resources, P.B.; data curation, Ł.A. and P.B.; writing—original draft preparation, Ł.A., P.B., I.B., R.A. and M.B.; writing—review and editing, Ł.A., P.B., I.B. and R.A.; visualization, Ł.A. and P.B.; supervision, P.B. and R.A.; project administration, P.B.; funding acquisition, Ł.A., P.B. and M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The presented research was financed under the “Implementation Doctorate I, Grant No. DWD/7/0048/2023”. The funding institution was the Ministry of Science and Higher Education.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Łukasz Adamik was employed by the company Nowy Styl sp. z o.o. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Červený, L.; Sloup, R.; Červená, T.; Riedl, M.; Palátová, P. Industry 4.0 as an Opportunity and Challenge for the Furniture Industry—A Case Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimino, A.; Gnoni, M.G.; Longo, F.; Solina, V. Integrating multiple industry 4.0 approaches and tools in an interoperable platform for manufacturing SMEs. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 186, 109732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, J. Advancing wooden furniture manufacturing through intelligent manufacturing: The past, recent research activities and future perspectives. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamik, Ł.; Wilkowski, J. Charakterystyka rozwiązań Przemysłu 4.0 stosowanych w polskim przemyśle meblarskim na przykładzie Fabryki Mebli Biurowych Nowy Styl w Jaśle Characteristics of Industry 4.0 solutions used in the Polish furniture industry on example of the Nowy Styl Office Furniture Factory in Jasło. Biul. Inf. 2023, 3–4, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamik, Ł.; Auriga, R.; Borysiuk, P. Influence of Process and Material Factors on the Quality of Machine Processing of Laminated Particleboard. Materials 2025, 18, 3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, C.A.; Aguilera, C.; Sappa, A.D. Melamine faced panels defect classification beyond the visible spectrum. Sensors 2018, 18, 3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slabejová, G.; Vidholdová, Z.; Iždinský, J. Evaluation of Resistance Properties of Selected Surface Treatments on Medium Density Fibreboards. Coatings 2023, 13, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowaluk, G.; Szymanski, W.; Beer, P.; Sinn, G.; Gindl, M. Influence of Tools Stage on Particleboards Milling. Wood Res. 2007, 52, 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Porankiewicz, B.; Chiaki, T. The Workability of Melamine Coated Particle Boards. Bull. Fac. Agric. Shimane Univ. 1993, 27, 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Szwajka, K.; Trzepieciński, T. The influence of machining parameters and tool wear on the delamination process during milling of melamine-faced chipboard. Drewno 2017, 60, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanowski, K.; Szymona, K.; Morek, R.; Górski, J.; Podziewski, P.; Cyrankowski, M. Influence of coatings on edge milling quality. Ann. Wars. Univ. Life Sci. 2015, 92, 444–447. [Google Scholar]

- Zbieć, M.; Borysiuk, P.; Mazurek, A. Thermoplastic Bonded Composite Chipboard Part 2-Machining Tests. Trieskové A Beztrieskové Obrábanie Dreva 2012, 8, 399–405. [Google Scholar]

- Onat, S.M.; Kelleci, O. Particleboard Density and Surface Quality AS-PROCEEDINGS. 2023. Available online: https://as-proceeding.com/index.php/iccar (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Pałubicki, B.; Beer, P.; Sinn, G.; Stanzl-Tschegg, S. Finite Element Analysis of Tool Indentation into Melamine Coated Particleboard, 2004. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/255978917 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Pałubicki, B. Badania nad Jakością Obróbki Elementów Meblowych z płyt Wiórowych Laminowanych, Poznań. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Life Sciences, Poznań, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pałubicki, B.; Kowaluk, G.; Beer, P. FEM analysis of stress distribution during cutting in laminated particleboard. Ann. Wars. Univ. Life Sci. For. Wood Technol. 2008, 64, 158–161. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, A.J.; Jeremias, T.D.; Gonzalez, A.R.; Amorim, H.J. Assessment of melamine-coated MDF surface finish after peripheral milling under different cutting conditions. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2019, 77, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fengel, D.; Wegener, G. Wood: Chemistry, Ultrastructure, Reactions; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, P.; Kemp, M.F. Decorative Laminates. In PLASTICS: Surface and Finish, 2nd ed.; Simpson, W.G., Ed.; The Royal Society of Chemistry: North Yorkshire, UK, 1995; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- EN 310:1996; Wood-Based Panels—Determination of Modulus of Elasticity in Bending and of Bending Strength. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 1996.

- EN 319:1993; Particleboards and Fibreboards—Determination of Tensile Strength Perpendicular to the Plane of the Board. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 1993.

- EN 323:1996; Wood-Based Panels—Determination of Density. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 1996.

- Niemz, P. Physik des Holzes und Holzwerkstoffe; DRW-Verlag: Leinfelden-Echterdingen, Germany, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, E.D.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Q.; Kawai, S.E.M.; Kawai, W.Z.S.; Wang, Q. Effects of mat moisture content and press closing speed on the formation of density profile and properties of particleboard. Springer J. Wood Sci. 1998, 44, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, E.; Zhang, M.; Han, G.; Kawai, S.; Wang, Q. Formation of the density profile and its effects on the properties of fiberboard. J. Wood Sci. 2000, 46, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, E.-D.; Yang, P.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Q.; Nakao, T.; Li, K.-F.; Kawai, S. Analysis of the effects of density profile on the bending properties of particleboard using finite element method (FEM). Holz Als Roh—Und Werkst. 2003, 61, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treusch, O.; Tröger, F.; Wegener, G. Einfluss von Rohdichte und Bindemittelmenge auf das Rohdichteprofil von einschichtigen Spanplatten. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2004, 62, 474–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, R. Wood Handbook—Wood as an Engineering Material; General Technical Report FPL-GTR-282; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory: Madison, WI, USA, 2021.

- Claude, M.; Yemele, N.; Blanchet, P.; Cloutier, A.; Koubaa, A. Effects of bark content and particle geometry on the physical and mechanical properties of particleboard made from black spruce and trembling aspen bark. For. Prod. J. 2008, 58, 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Szwajka, K.; Trzepieciński, T. Effect of tool material on tool wear and delamination during machining of particleboard. J. Wood Sci. 2016, 62, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R.J.; Evans, P.D. Effects of manufacturing variables on surface quality and distribution of melamine formaldehyde resin in paper laminates. Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2005, 36, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.