Abstract

Many industrial sectors are concerned about microbiological contamination and the associated risk of microbiologically influenced corrosion (MIC). This applies in particular to the transmission and storage of fuels in the refining industry. Exceeding a certain level of these contaminants poses a serious risk to fuel quality and can cause storage and pipeline infrastructure corrosion. This situation requires an urgent evaluation of microorganism levels in the fuel to avert such detrimental consequences. Diesel fuels containing biofuel additives are particularly susceptible to these phenomena. Traditional detection methods are limited by low sensitivity, high costs, and long turnaround times, making them unsuitable for quick, on-site, and real-time detection and monitoring. A novel approach involves the application of microwave dielectric testing to quantify microbial load in diesel fuel. Microwave dielectric spectroscopy offers a non-destructive, label-free solution, providing rapid information on microorganism presence. Combined with chemometric techniques, it effectively estimates total microorganism counts in diesel fuel. Measurement in the X-band range (8.2–12.4 GHz) takes a few seconds. Calibration with known bacterial and fungal concentrations (103 to 107 CFU/mL) and principal component analysis (PCA) of the spectroscopic data allow for clear differentiation of contamination levels, categorizing them from acceptable to hazardous. The sensitivity limit of the proposed method corresponds to a bacterial concentration of 103 CFU/mL.

1. Introduction

Numerous industrial sectors express significant concern regarding microbiologically influenced corrosion (MIC) due to its potential to cause severe damage to infrastructure, equipment, and pipelines [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12].

The refining industry is particularly vulnerable to MIC, as they often operate in environments with moisture and organic materials, providing ideal conditions for microbial growth [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. The financial implications of MIC can be substantial, including increased maintenance costs, unplanned downtime, and potential safety hazards. Additionally, the growth of microorganisms in the fuel may cause deterioration of the quality and properties of the fuel and clogging of filters.

Many companies are investing in research and development to implement more effective prevention and control strategies [5,7,13,16,18,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. This includes using biocides, advanced coatings, and regular monitoring techniques to identify and address microbial activity before it leads to significant corrosion-related issues.

Research indicates that the incorporation of biodiesel into diesel fuel exacerbates MIC [29,30,31,32]. This phenomenon occurs when microorganisms, such as bacteria and fungi, thrive in the presence of water and organic materials found in biodiesel blends. The introduction of biodiesel, which is derived from renewable sources like vegetable oils or animal fats, alters the chemical composition of the fuel, creating an environment that is more conducive to microbial growth. Biodiesel contains more dissolved oxygen and adsorbed water, providing a good habitat for microorganisms compared to fossil diesel [31,33,34,35].

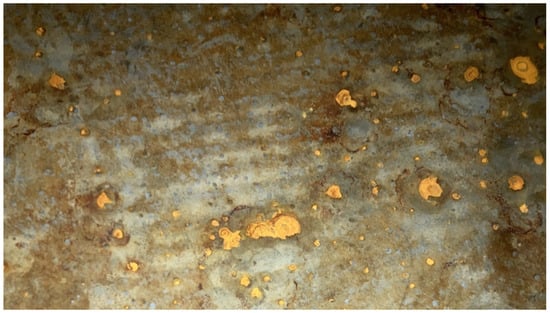

As these microorganisms proliferate, they form biofilms on the surfaces of storage tanks, pipelines, and other fuel system components. These biofilms can trap moisture and create localized areas of corrosion, leading to the deterioration of metal surfaces (Figure 1). The metabolic activities of the microorganisms can produce corrosive byproducts, such as organic acids, which further accelerate the corrosion process [29]. Moreover, the presence of biodiesel can change the solubility and stability of water in the fuel, increasing the likelihood of water accumulation at the bottom of storage tanks. This water layer serves as a breeding ground for microbes, intensifying the risk of MIC. The combination of biodiesel’s properties and the conducive environment for microbial growth can lead to significant maintenance challenges, increased operational costs, and potential failures in fuel delivery systems.

Figure 1.

An example of damage to the inner surface of a diesel storage tank in the presence of MIC. Light red areas are corrosion sites (cavities) caused by the presence of biofilm.

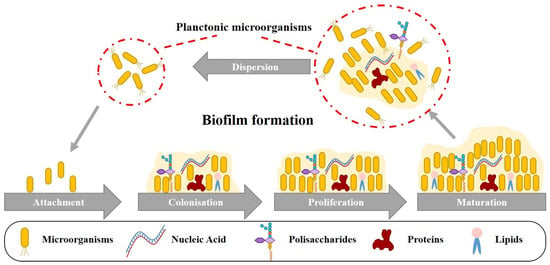

Under optimal conditions, planktonic microorganisms present in the fuel can proliferate and form biofilm-covered regions on the surfaces of the steel walls (Figure 2). These microorganisms, which are typically suspended in liquid fuel, thrive in environments that provide the right combination of nutrients, temperature, and other favorable factors. As they multiply, they begin to adhere to surfaces, including the steel walls of storage tanks or pipelines. The process of biofilm formation involves the initial attachment of these microorganisms to the surface, followed by the production of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) that create a protective matrix. This matrix not only helps to anchor the microorganisms in place but also provides a conducive environment for their growth and survival. Over time, these biofilms can develop into complex communities, consisting of various species of bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms.

Figure 2.

Stages of biofilm formation on the inner steel walls of a tank in the presence of diesel fuel and water [36].

The presence of biofilms on steel surfaces can have significant implications for the integrity and performance of fuel storage and transport systems.

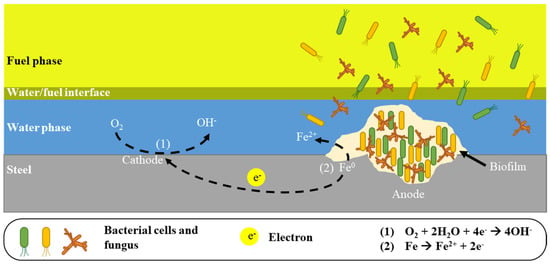

The uneven accumulation of biofilm on the steel surface limits the access of oxygen to selected fragments of the steel surface and corrosion cells are formed, causing local corrosion of the steel (Figure 1 and Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The mechanism of local corrosion damage (cavity) in the inner wall of a diesel storage tank caused by biofilm formation [36].

The development of microorganisms also causes the formation of biomass, which results in the deterioration of fuel quality and the clogging of filters in dispensers. Dead cells and metabolic products of living microorganisms fall to the bottom of the tank, forming sediment. Its formation is the most obvious and the easiest to recognize symptom of microbial activity. The point is to be able to anticipate such situations in advance and take appropriate measures in good time if such a threat arises.

Each fuel storage tank or infrastructure component may host a unique community of microorganisms, influenced by factors such as the type of diesel and biodiesel component stored, environmental conditions, and the materials of the tank or component itself. This diversity means that the corrosivity characteristics can vary widely from one location to another, making it difficult to establish a standardized approach for evaluating the risks associated with microbial growth. Given this complexity, it seems reasonable to propose that the overall quantity of microorganisms present in the fuel should be considered a key metric for assessing potential risks. By quantifying the microbial load, is it possible to gain insights into the likelihood of MIC and its associated impacts. A higher concentration of planktonic microorganisms will indicate a greater tendency to corrosion (Figure 2). And with monitoring, it is possible to observe a growing trend in the number of microorganisms. Since the presence of planktonic microorganisms precedes the biofilm formation to some extent, this gives adequate time for the appropriate response.

This paper proposes a quick method to estimate the total amount of microorganisms in diesel fuel using X-band microwave dielectric spectroscopy (8.2–12.4 GHz) [37,38,39,40,41,42]. The measurement takes several seconds and can be conducted on a sample that has been directly extracted without the need for any special preparation, such as the addition of a medium or culture. It is possible also to position the sensor within the tank for ongoing monitoring. The essence of the method is based on the measurement of the dielectric properties of a diesel fuel sample in this frequency range. It was assumed that the presence of different amounts of microorganisms in the diesel sample would be reflected in the appropriate change in the dielectric parameters of the diesel fuel. In this way, the dielectric properties of diesel fuel could be used as an indirect method to detect and estimate microorganisms’ content in fuel [43]. Any object differing in dielectric and electrical properties from diesel fuel affects the course of the obtained frequency spectrum. Bacteria distributed in a dielectric liquid medium like fuel can alter the dielectric spectrum in the microwave range, primarily through changes in permittivity and loss tangent due to their higher water content and polarizability compared to non-polar hydrocarbons. Bacterial cells introduce interfacial polarization effects and increased effective permittivity in low-loss dielectric liquids, as their hydrated structures (with relative permittivity ~50–80 from water) contrast sharply with fuel’s low values (~2–4). This leads to measurable shifts in the microwave dielectric spectrum, especially if bacteria form aggregates, enhancing scattering and absorption at microwave frequencies. In fuel-like media, microbial contamination modifies the bulk dielectric response via volume fraction effects, enabling microwave sensing for bacterial load. Live cells show distinct loss profiles from membrane-bound water relaxation, distinguishable from dead cells or pure fuel.

Principal component analysis (PCA) was employed to objectively evaluate and interpret the acquired spectra. It enabled the separation of subtle differences between the spectra obtained for model solutions with known amounts of microorganisms based on a large number of spectroscopic data and visualization in an easy-to-evaluate way. This type of measurement can be carried out in a non-contact way, which can also allow for continuous or semi-continuous monitoring of the fuel’s biological contamination.

Attempts have been made to use microwave-based sensors for the detection and quantification of water content in solid fuels [44,45,46,47,48,49], crude oil [50,51], and liquid fuels [52], particularly diesel fuel [53]. In addition, microwave-based sensor was tested to detect the presence of a water layer at the bottom of storage tank [54]. Resonance-based and reflection-based measurement techniques are most commonly employed for these purposes [55]. Attempts have also been made to apply impedance (dielectric) spectroscopy, operating at frequencies lower than the microwave range (below 1 MHz), to determine the water content in diesel fuel [56,57]. Within this low-frequency range, the presence of microorganisms can also be detected [43]. However, to date, no studies have been reported on the application of dielectric spectroscopy in the microwave frequency range for the detection and analysis of microbiological contamination in diesel fuel. However, there is extensive research on microwave dielectric detection of biological particles in other matrices (e.g., coplanar electrodes on microfluidic platforms for bioparticle detection), which suggests that microwave methods may be substantially sensitive to biological entities [58]. Microbial contamination of diesel fuel is commonly investigated using a combination of microbiological, molecular, and physicochemical methods. Classical culture-based techniques, such as plate counting and enrichment cultures, are applied to detect and quantify viable bacteria and fungi present in the fuel and associated water phases [59]. These methods allow for the preliminary identification of dominant microbial groups involved in fuel degradation. Molecular biology approaches, including polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and quantitative PCR (qPCR) are increasingly used to identify microbial communities at the species or genus level [59,60]. The latest work explores the feasibility of using the advanced MALDI-ToF-MS (Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry) technique to determine microbiological contaminants in diesel fuel [61,62]. This mass spectrometry technique relies on the protein profiles of identified microorganisms and is capable of accurately identifying microorganisms. In parallel, physicochemical analyses of diesel fuel, such as water content determination, acid number, and analysis of metabolic by-products (e.g., organic acids, sulfides, and biofilms), are conducted to assess the extent of microbial activity.

2. Materials and Methods

The challenge of selecting an appropriate testing environment arises from the unique characteristics of real fuel systems, coupled with the extensive diversity of microorganisms and the varying physical conditions encountered in practical applications. For this purpose, the ASTM E 1259-18 “Standard Practice for Evaluation of Antimicrobials in Liquid Fuels Boiling Below 390 °C” [63] was used as a basic experimental approach. It concerns the assessment of the effectiveness of biocides used to prevent the deterioration of fuels due to microbial activity. According to this standard, it is permissible to assess the effectiveness of biocides according to various schemes and with the use of various microorganisms, while the microorganisms selected for testing should be from cultures for which the possibility of development in fuel and the ability to use fuel as the only carbon source has been confirmed.

Additional sources were used in the formulation of the research assumptions [13,22].

In Poland, the current formulation of diesel fuel comprises a blend that includes 7% biodiesel, referred to as B7, and the evaluations were conducted using this specific type of fuel blend.

The bacterial and fungal strains used for these studies were isolated from diesel fuel. Four types of microorganisms that are frequently found in B7 diesel fuel tanks were selected to establish the relationship between the microwave spectrum and initial bacterial and fungi loads (log (CFU/mL)). The measurement system was calibrated using four microorganisms: Pseudomonas sp., Bacillus megaterium, Candida lipolytica and Exophiala spinifera. Bacterial strains were cultured on Luria broth and agar, and fungal on Sabourad liquid media and agar. First, dilutions of bacterial (at the same concentration of 107 CFU/mL) and fungal culture at the concentration of 106 CFU/mL were prepared separately. Then, equal amounts of each solution were mixed. The resulting suspension was named 7 due to the logarithm of the bacterial concentration. Serial dilutions (1 in 10) for a concentration range of 106–103 CFU/mL were prepared using 900 mL of water and 100 mL of a given diluted solution (at a known concentration) obtained from the mixture. The solution marked as “6” was obtained first. From it, by further dilution, the solution marked as “5” was obtained, and so on. The last solution obtained in this way was solution “3”. The solution marked as “0” without microorganisms containing an equal amount of Luria broth and Sabourad liquid media was applied as a control.

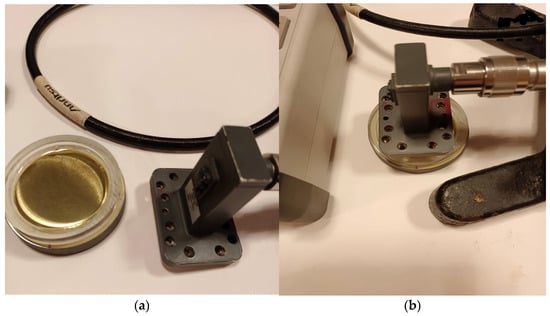

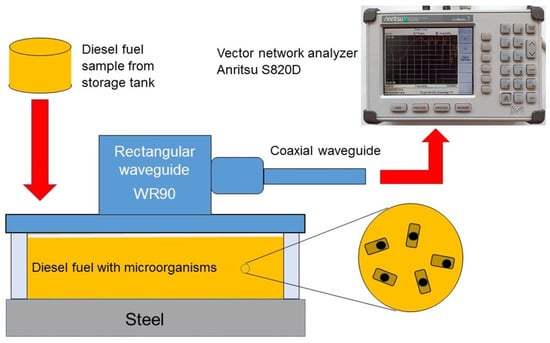

This means that six dilutions with a defined amount of microorganisms were prepared, as shown in Table 1. Then, 2 mL of suspension with the appropriate amount of microorganisms per 1 dm3 of fuel was added to the diesel fuel B7 and stirred vigorously for 30 s. 2 mL of control solution (without microorganisms) was added to the sample marked as “0”. After approximately one hour, 15 mL of fuel containing the appropriate amount of microorganisms was withdrawn from the bottle using a syringe and poured into a horizontally positioned cylindrical vessel, obtaining an 8 mm thick layer (Figure 4). The vessel’s bottom was made of polished steel. The vessel walls were 9 mm high, so the waveguide front was 1 mm from the fuel layer surface. The tests were conducted in a laboratory at 22 (±1) °C. The fuel samples tested were also stored at this temperature prior to measurement.

Table 1.

Designation and composition of suspensions intended for measurements.

Figure 4.

View of the measuring vessel with the fuel sample, and waveguide before measurement (a) and during measurement (b).

The measurement system is shown in Figure 5. It consists of a single-port vector network analyzer Site Master™ S820D (Anritsu, Atsugi, Kanagawa, Japan) and an open-ended WR90 rectangular waveguide connected to the device by a coaxial waveguide APC-7 mm from the same manufacturer.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of a cell in a measuring system.

The reflection loss RL spectra were determined. The measurement is performed in such a way that the device sends a short pulse of a single frequency, immediately registers the power of the reflected wave and then goes to the next frequency point. The signal power was only 50 mW. The analysis was performed at frequencies ranging from 8.2 to 12.4 GHz with 156 frequency points. The whole measurement time of 156 frequency points takes about 3 s. The selected range of frequencies guarantees the best accuracy determined by employing the adjusted load. The Anritsu S820D device was calibrated before the measurement using three reference loads.

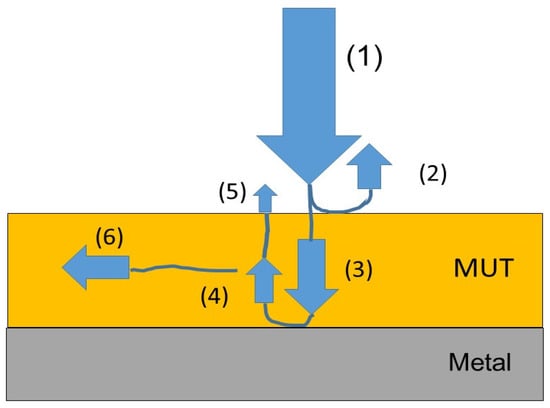

Figure 6 depicts the idea of measuring the dielectric properties of a material under test (MUT) using an electromagnetic wave. According to microwave absorption theory, incident power can be divided into three parts when the electromagnetic waves strike the absorbing materials: reflection, absorption, and transmission. The transmitted wave is reflected on the surface of the conductive layer (metal), which generates internal reflections. The reflection of the microwave consists of surface reflectance and numerous reflections. Depending on the dielectric parameters of the tested material, a different dependence of the reflection loss coefficient is obtained.

Figure 6.

The idea of measuring the dielectric properties of a material under test (MUT) using an electromagnetic wave. (1) incident wave, (2) first reflection wave, (3) transmission wave, (4) second reflection wave, (5) third reflection wave, (6) absorbing wave.

Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using the PAST statistics software package (v 4.17) [64].

3. Results

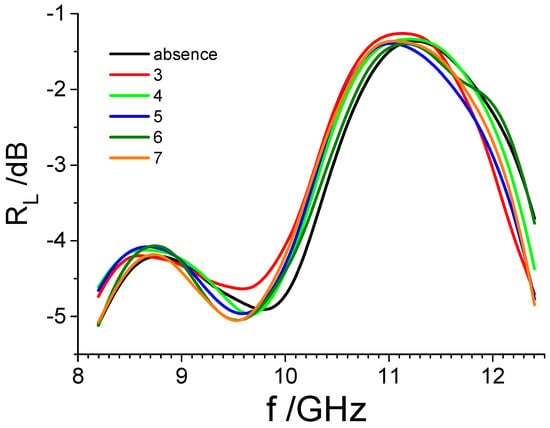

As a result of the measurement, a complex reflection loss RL was obtained. Figure 7 shows the magnitude of the reflection loss RL as a function of frequency f. Error bars are not marked on the graphs. They are typically not drawn on spectroscopic data plots because the data represent raw spectra with high point density, where uncertainty is low and does not vary significantly between points. Adding bars to data points would make the plot unreadable. In spectroscopy methods, the dominant error is relatively small and further processing using PCA significantly reduces potential errors.

Figure 7.

Reflection loss (RL) curves of seven different diesel samples with a known number of microorganisms are described in Table 1.

It can be seen that the obtained spectra are similar to each other but not identical. The only difference between the tested samples was the different amounts of microorganisms in the fuel. It follows that the differences in the course of the spectra result from the presence of different amounts of microorganisms. Microorganisms have a quite complicated structure, but at the same time, their electrical parameters are different from the parameters of the fuel in which they are found [43]. This makes it possible to detect them using dielectric methods.

Looking at Figure 7, it would be difficult to directly use the obtained graphs to estimate the content of microorganisms in a fuel sample with an unknown number of microorganisms. To facilitate this, it was decided to use PCA.

PCA is a powerful statistical technique widely used in data analysis and machine learning for dimensionality reduction. The primary goal of PCA is to simplify complex datasets while preserving as much information as possible. This is particularly useful when dealing with high-dimensional data (e.g., spectroscopic as in this case), where the number of variables (or features) can be very large, making it challenging to visualize, interpret, and analyze the data effectively.

PCA converts a set of correlated features in the high-dimensional space into a few dimensions of uncorrelated features in the low-dimensional space [65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73]. These uncorrelated features are called principal components (PC). They describe the independent features of the tested object. In this way, PCA is used to extract important information from a multivariate data table and to express this information as a set of a few new variables.

The use of this method is effective when the obtained measurement data contain information in multidimensional correlated data [68]. Due to the spectroscopic nature of the data obtained, this is the case. At 156 frequency measurement points have data containing partially correlated information.

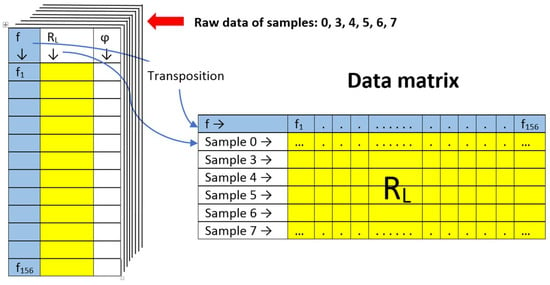

The analysis was performed on 6 individuals (diesel samples with different amounts of microorganisms) described by 156 variables (frequency points). These data are usually arranged in a matrix, with the number of rows equal to the number of samples and the number of columns equal to the number of variables measured. Using the raw spectroscopic data obtained for each sample in the form of a matrix containing three columns: microwave signal frequency f, reflection loss magnitude RL, and reflection loss phase angle φ (reflection loss is a complex quantity), the reflection loss magnitude RL was extracted in the form of a row in the data matrix by transposition (Figure 8). The phase angle φ was omitted. Thus, each row of the data matrix corresponds to the entire spectrum of a given sample, and each column represents the reflection loss (magnitude) RL of all samples at a given frequency.

Figure 8.

Schematic illustration of the creation of the data matrix used to perform PCA from raw spectroscopic data.

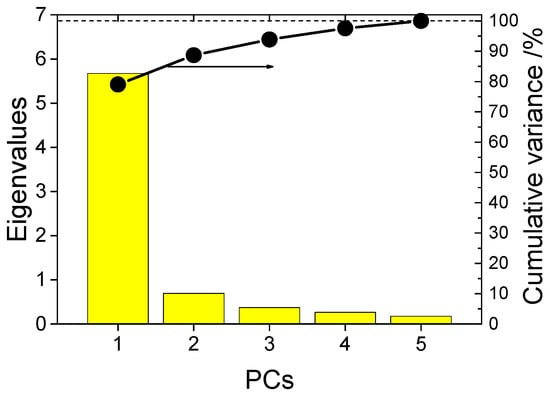

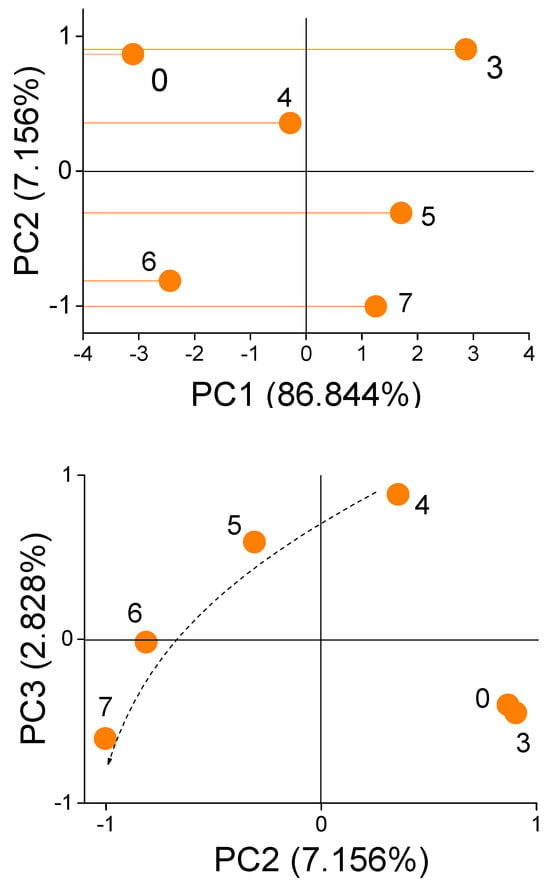

The calculation results show that the cumulative contribution rate of the first three eigenvalues is more than 96.8% (Figure 9). So the first three principal components can replace original variables. Figure 10 illustrates score plots of the first three PCs.

Figure 9.

Eigenvalues and cumulative variance showing the results of principal component analysis.

Figure 10.

Score plots of the first three principal components.

It is easy to see that both PC2 and PC3 are directly related to the microorganism concentrations. To determine the total content of microorganisms in the sample after performing a microwave measurement of a diesel fuel sample containing an unknown amount of microorganisms, we determine the values of the PC2 and PC3 coordinates and plot a point on the plane defined by the measurements of the calibration solutions. The location of the obtained point on the plane indicates the estimated content of microorganisms in the tested fuel sample.

The (Euclidean) distances between the points characterize the similarity between the samples (in this case, it refers to the total concentration of microorganisms in the diesel sample). The smaller the distances, the more similar the compared samples are in terms of the total concentration of microorganisms. Therefore, we search for the closest point with a known content of microorganisms for the measured point. On this basis, the total concentration of microorganisms in the tested sample is estimated.

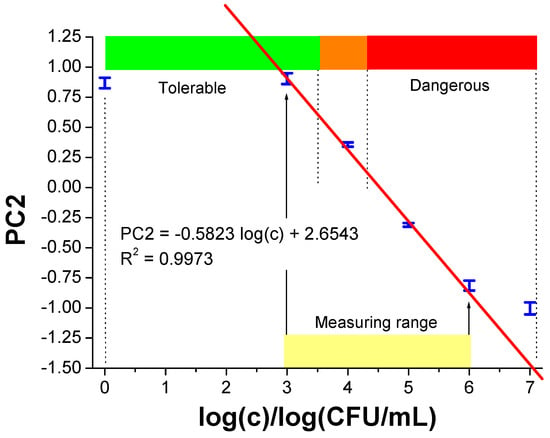

The sensitivity of the method was determined using the dependence of PC2 on the logarithm of the microorganism concentration in diesel fuel (Figure 10). It is easy to see that the extreme points (with concentrations 0 and 7) do not align along the straight line defined by the remaining points. Therefore, a straight line equation describing these four points was determined by linear regression, along with the degree of fit expressed as R2, as follows:

PC2= −0.5823 log(c) + 2.6543 (R2 = 0.9973)

The method sensitivity, defined as the slope of this calibration curve, was −0.5823 (log(CFU/mL)−1 over the range of the concentration logarithm from 3 to 6 (highlighted in yellow in Figure 11). By transforming Equation (1) we obtain the logarithm of the concentration of microorganisms as a function of the PC2 value, within the logarithm of the microorganism concentration range from 3 to 6:

log(c) = 4.5583 − (PC2/0.5823)

Figure 11.

The value of the coordinates on the PC2 axis depends on the total concentration of microorganisms. The tolerable range is marked in green, disturbing in orange, and dangerous in red. Measurement points (in blue) have error bars marked. Within the measurement range marked in yellow, it is possible to quantitatively determine the microorganism concentration according to Formula (2). The two upward arrows indicate the linear range of the calibration curve.

Equation (2) allows for determining the concentration of microorganisms in diesel fuel based on the PC2 value obtained from a single microwave measurement and PCA processing within the above-mentioned concentration range. Outside this range, the result is also useful, as it will qualitatively signal no hazard (PC2 > 0.86) or very high hazard (PC2 < −0.81), Figure 10.

The maximum error in determining PC2 was estimated for the points in Figure 10 as 5%, including the 2% typical error of the one-port vector network analyzer used for the tested frequency range, based on the results presented in [74]. The remaining error results from the imperfectly flat metal substrate of the measuring vessel (surface roughness) or non-parallel metal substrate and waveguide face, different sample positioning and repeatability, multiple reflections from the vessel side walls and so on.

Based on earlier works on microbiological hazards in Polish diesel fuel tanks [36], ranges of the total concentration of microorganisms in the fuel were distinguished, which can be tolerated (green), disturbing (orange) and dangerous (red), as shown in Figure 10. This allows for monitoring the microbiological threat in tanks and distribution systems (pipelines) on an ongoing basis and to take appropriate measures.

The studies described in [59] confirm these criteria, as they recognize that a bacterial load of 105 CFU/mL indicates very high microbiological contamination in diesel fuel, and under these conditions, after 60 days the number of microorganisms changes and grows ‘dramatically’. The London Energy Institute has published similar limits for microbiological contamination of fuels, including diesel, for long-term storage [22,36].

4. Conclusions

We have demonstrated a microwave spectroscopic sensor for the fast detection of the total concentration of microorganisms in diesel fuel using principal component analysis (PCA). This can serve as an indicator of the risk of MIC in the diesel fuel storage tank. It seems that the presented approach is currently the only option feasible in practice. The variety of microorganisms found in tanks, as well as the chemical composition of fossil diesel and biodiesel and the physical conditions of storage, does not allow for a precise determination of the corrosion risk. Periodic measurement of the dielectric parameters of the fuel in the tank allows for the observation of possible changes in the number of microorganisms present in the fuel due to changes in the dielectric parameters, which are transformed using PCA into a form that is easy to assess visually (qualitatively) and/or numerically (quantitatively). This approach also allows for the automation of threat control. Based on the historical data obtained, it can be concluded whether the tested amount of organisms in the diesel fuel is tolerated, disturbing or dangerous due to fuel contamination and corrosion risk of the fuel storage tank walls.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, analysis, investigation, visualization, A.M. and M.K.; Writing—original draft M.K.; Writing—review and editing, supervision, A.M.; Methodology, resources, editing, A.B.-D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper originated within a thesis developed in the “Industry Doctorate” program co-financed from the funds of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Poland and ORLEN S.A. at the Department of Corrosion and Electrochemistry of the Gdansk University of Technology (M.K.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Michał Kuna was employed by ORLEN S.A. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Flemming, H.C. Biofouling and Microbiologically Influenced Corrosion (MIC)—An Economic and Technical Overview; Heitz, E., Sand, W., Flemming, H.C., Eds.; Microbial Deterioration of Materials; Springer: Berlin, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Little, B.J.; Lee, J.S.; Ray, R.I. Diagnosing Microbiologically Influenced Corrosion: A State-of-the-Art Review. Corrosion 2006, 62, 1006–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starosvetsky, J.; Starosvetsky, D.; Armon, R. Identification of microbiologically influenced corrosion (MIC) in industrial equipment failures. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2007, 14, 1500–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, B.J.; Lee, J.S. Microbiologically influenced corrosion: An update. Int. Mater. Rev. 2014, 59, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaherdashti, R. Microbiologically Influenced Corrosion: An Engineering Insight; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vigneron, A.; Head, I.M.; Tsesmetzis, N. Damage to offshore production facilities by corrosive microbial biofilms. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 2525–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, R.; Unsal, T.; Xu, D.; Lekbach, Y.; Gu, T. Microbiologically influenced corrosion and current mitigation strategies: A state of the art review. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2019, 137, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, B.J.; Blackwood, D.J.; Hinks, J.; Lauro, F.M.; Marsili, E.; Okamoto, A.; Rice, S.A.; Wade, S.A.; Flemming, H.-C. Microbially influenced corrosion—Any progress? Corros. Sci. 2020, 170, 108641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, R.B.; Skovhus, T.L. (Eds.) Failure Analysis of Microbiologically Influenced Corrosion, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Puentes-Cala, E.; Tapia-Perdomo, V.; Espinosa-Valbuena, D.; Reyes-Reyes, M.; Quintero-Santander, D.; Vasquez-Dallos, S.; Salazar, H.; Santamaría-Galvis, P.; Silva-Rodríguez, R.; Castillo-Villamizar, G. Microbiologically influenced corrosion: The gap in the field. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 924842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Wang, C.; Liu, J.; Sand, W.; Nabuk Etim, I.-I.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, A.; Duan, J.; Zhang, R. The Microbiologically Influenced Corrosion and Protection of Pipelines: A Detailed Review. Materials 2024, 17, 4996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, D.; Li, Y.; Zhang, R.; Cui, N.; Duan, J. How Often Should Microbial Contamination Be Detected in Aircraft Fuel Systems? An Experimental Test of Aluminum Alloy Corrosion Induced by Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria. Materials 2024, 17, 3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passman, F.J. (Ed.) Fuel and Fuel System Microbiology: Fundamentals, Diagnosis and Contamination Control; ASTM Manual Series: MNL 47; ASTM International: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, E.C.; Hill, G.C. Microbial Contamination and Associated Corrosion in Fuels, during Storage, Distribution and Use. Adv. Mater. Res. 2008, 38, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enning, D.; Lee, J.S.; Skovhus, T.L. (Eds.) Microbiologically Influenced Corrosion in the Upstream Oil Gas Industry; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Skovhus, T.L.; Eckert, R.B.; Rodrigues, E. Management and control of microbiologically influenced corrosion (MIC) in the oil and gas industry—Overview and a North Sea case study. J. Biotechnol. 2017, 256, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.; Hawboldt, K.; Bottaro, C.; Khan, F. Review and analysis of microbiologically influenced corrosion: The chemical environment in oil and gas facilities. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2018, 53, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleb-Berrouane, M.; Khan, F.; Hawboldt, K.; Eckert, R.; Skovhus, T.L. Model for microbiologically influenced corrosion potential assessment for the oil and gas industry. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2018, 53, 378–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kermani, B.; Harrop, D. Corrosion and Materials in Hydrocarbon Production: A Compendium of Operational and Engineering Aspects; Wiley-Asme Press Series; ASME Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mand, J.; D Enning, D. Oil field microorganisms cause highly localized corrosion on chemically inhibited carbon steel. Microb. Biotechnol. 2020, 14, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y. Review of microbial corrosion prevention and control technology in the petroleum industry. Eng. Res. Express 2024, 6, 022401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Energy Institute. Guidelines for the Investigation of the Microbial Content of Petroleum Fuels and for the Implementation of Avoidance and Remedial Strategies, 2nd ed.; Energy Institute: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Geissler, B.; De Paula, R.; Keller-Schultz, C.; Lilley, J.; Keasler, V. Data mining to prevent microbiologically influenced corrosion? In NACE—International Corrosion Conference Series, Proceedings of the NACE Corrosion Conference 2014-4080, San Antonio, Texas, USA, 9–13 March 2014; NACE International: Houston, TX, USA, 2014; Paper Number NACE-2014-4080. [Google Scholar]

- Bautista, L.F.; Vargas, C.; González, N.; Molina, M.C.; Simarro, R.; Salmerón, A.; Murillo, Y. Assessment of biocides and ultrasound treatment to avoid bacterial growth in diesel fuel. Fuel Process. Technol. 2016, 152, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, A.; Cazarolli, J.C.; Cavalcanti, E.; Ferrao, M.F.; Gerbase, A.E.; Ferrão, M.F.; Piatnicki, C.M.S.; Bento, F.M. Monitoring of efficacy of biocides during storage simulation of diesel (B0), biodiesel (B100) and blends (B7 and B10). Fuel 2013, 112, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telegdi, J. Multifunctional Inhibitors: Additives to Control Corrosive Degradation and Microbial Adhesion. Coatings 2024, 14, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saadi, S.; Raman, R.K.S. Silane Coatings for Corrosion and Microbiologically Influenced Corrosion Resistance of Mild Steel: A Review. Materials 2022, 15, 7809. [Google Scholar]

- Rasheed, P.A.; Pandey, R.P.; Jabbar, K.A.; Samara, A.; Abdullah, A.M.; Mahmoud, K.A. Chitosan/Lignosulfonate Nanospheres as “Green” Biocide for Controlling the Microbiologically Influenced Corrosion of Carbon Steel. Materials 2020, 13, 2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamps, B.W.; Bojanowski, C.L.; Drake, C.A.; Nunn, H.S.; Lloyd, P.F.; Floyd, J.G.; Emmerich, K.A.; Neal, A.R.; Crookes-Goodson, W.J.; Stevenson, B.S. In situ Linkage of Fungal and Bacterial Proliferation to Microbiologically Influenced Corrosion in B20 Biodiesel Storage Tanks. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knisz, J.; Eckert, R.; Gieg, L.M.; Koerdt, A.; Lee, J.S.; Silva, E.R.; Skovhus, T.L.; Stepec, B.A.A.; Wade, S.A. Microbiologically influenced corrosion—More than just microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2023, 47, fuad041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ai, W.; Cho, H.M.; Mahmud, M.I. The Impact of Various Factors on Long-Term Storage of Biodiesel and Its Prevention: A Review. Energies 2024, 17, 3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borecki, M.; Geca, M.; Zan, L.; Prus, P.; Korwin-Pawlowski, M.L. Multiparametric Methods for Rapid Classification of Diesel Fuel Quality Used in Automotive Engine Systems. Energies 2024, 17, 4189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, A.; Luiz, F.; Martins, L.F.; Ventura, E.S.d.A.; de Landa, F.H.T.G.; Valoni, É.d.A.; Faria, F.R.D.; Ferreira, R.F.; Faller, M.C.K.; Valério, R.R.; et al. Microbiological aspects of biodiesel and biodiesel/diesel blends biodeterioration. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2015, 99, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passman, F.J. Microbial contamination and its control in fuels and fuel systems since 1980-a review. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2013, 81, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, Y.S.; Reddy, C.O.; Subhadra, M.; Rajagopal, K. Long-term storage effect on molecular interactions of biodiesels and blends. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2024, 46, 9404–9418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuna, M.; Miszczyk, A. Risks caused by microbiologically influenced corrosion in diesel fuel storage tanks. Ochr. Przed Koroz. 2024, 67, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miszczyk, A.; Darowicki, K. Inspection of protective linings using microwave spectroscopy combined with chemometric methods. Corros. Sci. 2012, 64, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russel, M.; Sophocleous, M.; JiaJia, S.; Xu, W.; Xiao, L.; Maskow, T.; Alam, M.; Georgiou, J. High-frequency, dielectric spectroscopy for the detection of electrophysiological/biophysical differences in different bacteria types and concentrations. Anal. Chim. Acta 2018, 1028, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Teruel, J.D.; Jones, S.B.; Robinson, D.A.; Giménez-Gallego, J.; Zornoza, R.; Torres-Sánchez, R. Measurement of the broadband complex permittivity of soils in the frequency domain with a low-cost Vector Network Analyzer and an Open-Ended coaxial probe. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 195, 106847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, W.; Schultz, J.W. Wideband Microwave Materials Characterization; Artech House: Boston, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Adair, R.K. Vibrational Resonances in Biological Systems at Microwave Frequencies. Biophys. J. 2002, 82, 1147–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Omer, A.E.; Shaker, G.; Safavi-Naeini, S. Rapid Viral Detection Using Microwave Sensors. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Symposium on Antennas and Propagation and USNC-URSI Radio Science Meeting, Denver, CO, USA, 10–15 July 2022; pp. 1336–1337. [Google Scholar]

- Furst, A.L.; Francis, M.B. Impedance-Based Detection of Bacteria. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 700–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuelsson, R.; Burvall, J.; Jirjis, R. Comparison of different methods for the determination of moisture content in biomass. Biomass Bioenergy 2006, 30, 929–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeown, M.S.; Trabelsi, S.; Nelson, S.O.; Tollner, E.W. Microwave sensing of moisture in flowing biomass pellets. Biosyst. Eng. 2017, 155, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjeldsen, H.; Østergaard, P.F.; Strauss, H.; Nielsen, J.; Tallawi, B.; Georgin, E.; Sabouroux, P.; Nielsen, J.G.; Hougaard, J.O. Calibration Techniques for Water Content Measurements in Solid Biofuels. Energies 2024, 17, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olkkonen, M.-K. Online Moisture Measurements of Biofuel at a Paper Mill Employing a Microwave Resonator. Sensors 2018, 18, 3844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julrat, S.; Trabelsi, S. In-line microwave reflection measurement technique for determining moisture content of biomass material. Biosyst. Eng. 2019, 188, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aro, R.; Ayoub, M.W.B.; Leito, I.; Georgin, É.; Savanier, B. Calibration and Uncertainty Estimation for Water Content Measurement in Solids. Int. J. Thermophys. 2020, 42, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, S.; Joshi, M.S. Design and Analysis of Shielded Vertically Stacked Ring Resonator as Complex Permittivity Sensor for Petroleum Oils. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2015, 63, 2411–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Q.; Tang, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Duan, X. Contactless and Simultaneous Measurement of Water and Acid contaminations in Oil Using a Flexible Microstrip Sensor. ACS Sens. 2020, 5, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Andria, G.; Attivissimo, F.; Di Nisio, A.; Trotta, A.; Camporeale, S.M.; Pappalardi, P. Design of a microwave sensor for measurement of water in fuel contamination. Measurement 2019, 136, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loconsole, A.M.; Francione, V.V.; Portosi, V.; Losito, O.; Catalano, M.; Di Nisio, A.; Attivissimo, F.; Prudenzano, F. Substrate-Integrated Waveguide Microwave Sensor for Water-in-Diesel Fuel Applications. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, K.; Grozescu, I.V.; Tiong, L.K.; Sim, L.T.; Mohd, R. Water detection in fuel tanks using the microwave reflection technique. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2003, 14, 1905–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozar, D. Microwave Engineering; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Delfino, J.R.; Pereira, T.C.; Costa Viegas, H.D.; Marques, E.P.; Pupim Ferreira, A.A.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Brandes Marques, A.L. A simple and fast method to determine water content in biodiesel by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. Talanta 2018, 179, 753–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macioszek, Ł.; Sobczyński, D. Moisture Content Assessment of Commercially Available Diesel Fuel Using Impedance Spectroscopy. Energies 2024, 17, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, C.P.; Jofre, M.; Jofre, L.; Romeu, J.; Jofre-Roca, L. Superheterodyne Microwave System for the Detection of Bioparticles with Coplanar Electrodes on a Microfluidic Platform. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 8002910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komariah, L.N.; Arita, S.; Rendana, M.; Ramayanti, C.; Suriani, N.L.; Erisna, D. Microbial contamination of diesel-biodiesel blends in storage tank; an analysis of colony morphology. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Sanchez, P.M.; Gorbushina, A.A.; Toepel, J. Quantification of microbial load in diesel storage tanks using culture- and qPCR-based approaches. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2018, 126, 216–223. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, S.; Martinez-Chapa, S.O. Principles and Mechanism of MALDI-ToF-MS Analysis. In Fundamentals of MALDI-ToF-MS Analysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwiczak, A.; Zieliński, T.; Sibińska, E.; Czeszewska-Rosiak, G.; Złoch, M.; Rudnicka, J.; Tretyn, A.; Pomastowski, P. Comparative analysis of microbial contamination in diesel fuels using MALDI-TOF MS. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E 1259-18; Standard Practice for Evaluation of Antimicrobials in Liquid Fuels Boiling Below 390 °C. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.T.; Ryan, P.D. PAST: Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001, 4, 9. Available online: http://palaeo-electronica.org/2001_1/past/issue1_01.htm (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Jackson, J.E. A User’s Guide to Principal Components; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Brereton, R.G. Applied Chemometrics for Scientists; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe, I.T. Principal Component Analysis, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Luciano, G.; Traverso, P.; Letardi, P. Applications of chemometric tools in corrosion studies. Corros. Sci. 2010, 52, 2750–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miszczyk, A.; Darowicki, K. Multispectral impedance quality testing of coil-coating system using principal component analysis. Prog. Org. Coat. 2010, 69, 330–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bro, R.; Smilde, A.K. Principal component analysis. Anal. Methods 2014, 6, 2812–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miszczyk, A.; Darowicki, K. Multivariate analysis of impedance data obtained for coating systems of varying thickness applied on steel. Prog. Org. Coat. 2014, 77, 2000–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deisenroth, M.P.; Faisal, A.A.; Ong, C.S. Mathematics for Machine Learning; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Drozda, M.; Miszczyk, A. Selection of organic coating systems for corrosion protection of industrial equipment. Coatings 2022, 12, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EURAMET. Guidelines on the Evaluation of Vector Network Analysers, EURAMET Calibration Guide No. 12, Version 3.0, 03/2018. Available online: https://www.euramet.org/publications-media-centre/calibration-guidelines (accessed on 8 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.