Abstract

The coagulation cascade triggered by the contact between blood and the surface of implantable/interventional devices can lead to thrombosis, severely compromising the long-term safety and efficacy of medical devices. As an alternative to systemic anticoagulants, surface anticoagulant modification technology can achieve safer hemocompatibility on the device surface, holding significant potential for clinical application. This article systematically elaborates on the latest research progress in the surface anticoagulant modification of blood-contacting materials. It analyzes and discusses the main strategies and their evolution, spanning from physically inert carbon-based coatings and heparin-based drug-functionalized surfaces to hydrophilic/hydrophobic dynamic physical barriers, biologically signaling regulatory coatings, and bio-integrative/regenerative endothelium-mimicking surfaces. The advantages and limitations of the respective methods are outlined, and the potential for synergistic application of multiple strategies is explored. A special emphasis is placed on current research hotspots regarding novel anticoagulant surface technologies, such as hydrogel coatings, liquid-infused surfaces, and 3D-printed endothelialization, aiming to provide insights and references for developing long-term, safe, and hemocompatible cardiovascular implantable devices.

1. Introduction

Thrombogenesis triggered by the contact between blood and implantable/interventional materials represents a core challenge that limits the clinical application of cardiovascular implants and devices (e.g., vascular stents, artificial heart valves, extracorporeal circulation circuits). When a material surface is exposed to blood, it induces non-specific adsorption of plasma proteins. The composition and conformational changes in this protein layer can further trigger platelet adhesion, activation, and aggregation, while also activating the intrinsic coagulation cascade, ultimately leading to thrombosis and device dysfunction [1,2]. To address this challenge, systemic anticoagulants (e.g., heparin, warfarin), while effective in inhibiting coagulation, are associated with limitations such as increased bleeding risk and the need for frequent monitoring, posing significant risks, especially for long-term implant users. Surface anticoagulant coating technology is a promising solution to this problem [3]. It employs material surface modification strategies to endow the blood-contacting interface with inherent anticoagulant function, thereby reducing or even eliminating the need for systemic anticoagulants.

Current mainstream anticoagulant coating technologies primarily follow three design concepts: active anticoagulation strategies, passive anti-adhesion strategies, and endothelialization strategies [4,5]. Active anticoagulation strategies involve immobilizing anticoagulant molecules like heparin or mimicking endothelial cell signaling molecules such as nitric oxide (NO) to directly intervene in the coagulation cascade or platelet activation pathways. Passive anti-adhesion strategies, represented by hydrophilic polyethylene glycol (PEG), zwitterionic polymers, hydrogels, and hydrophobic liquid-infused surfaces, utilize surface hydration layers to create an entropy barrier, steric hindrance, or super-repellent effects, physically blocking protein adsorption. Endothelialization strategies aim to achieve long-term, self-healing anticoagulant function by modifying surfaces with cell-selective peptides or growth factors to guide the directed differentiation and growth of endothelial progenitor cells. It is noteworthy that single strategies often struggle to meet the challenges of the complex in vivo environment [6]; therefore, multifunctional synergistic coatings have become a current research focus.

This article aims to systematically review the latest research progress in anticoagulant coating technologies. It will first categorize and elaborate on the design principles and characteristics of coatings based on their different mechanisms of action. It will focus on analyzing key challenges (such as long-term stability and biosafety) and their potential solutions. Furthermore, it will discuss the paradigm shift in coating technology from physical inertness (carbon-based coatings) to drug functionalization (heparin coatings), dynamic physical barriers (hydrophilic/hydrophobic coatings), biological signal regulation (NO-release coatings), and finally to biointegration and regeneration (endothelialized surfaces). Finally, future development trends will be discussed to provide a theoretical basis and technical reference for the development of a new generation of hemocompatible materials.

2. Thrombogenesis Mechanisms on the Surface of Implantable Devices

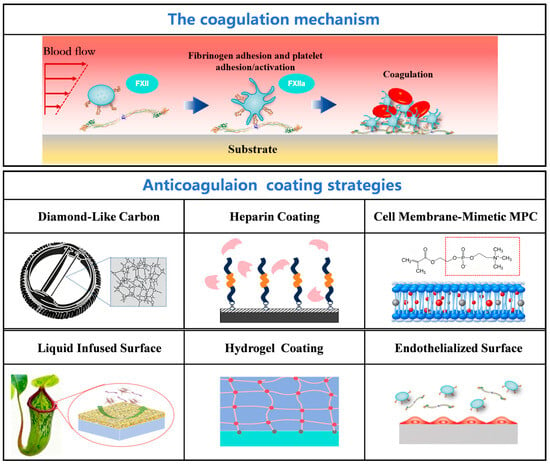

Contact between the surface of an implantable device and blood triggers a self-amplifying thrombogenic process involving protein adsorption, platelet activation, and the coagulation cascade (Figure 1). Initially, proteins in the blood form a dynamic adsorption layer on the material surface. If the surface properties (e.g., hydrophobicity, charge) induce conformational changes in procoagulant proteins such as fibrinogen and von Willebrand factor, exposing their binding sites, this initiates the specific adhesion of platelets via glycoprotein receptors [7]. The adherent platelets rapidly activate, releasing substances like ADP and thromboxane A2, which further recruit circulating platelets to aggregate. Concurrently, the material surface activates coagulation factor XII via the contact activation pathway, initiating the intrinsic coagulation cascade. This ultimately leads to the generation of the prothrombinase complex, driving the massive conversion of prothrombin to thrombin. Thrombin, acting as a central hub, not only catalyzes the formation of a stable fibrin network but also amplifies the coagulation signal dramatically through positive feedback mechanisms that activate platelets and various coagulation factors. Simultaneously, the inflammatory response triggered by implantation (e.g., complement activation, leukocyte release of tissue factor) and the coagulation process mutually reinforce each other, collectively leading to the formation and progression of thrombosis on the device surface [8]. The essence of this vicious cycle is the disruption of blood homeostasis by the material surface. Therefore, ideal anticoagulant strategies need to intervene at the source. These include immobilizing active molecules like heparin to directly inhibit coagulation factors, constructing hydrophilic/hydrophobic coatings to reduce non-specific protein adsorption, or promoting rapid endothelialization through bio-functionalized modifications to reconstruct a natural anticoagulant interface [9,10,11,12].

Figure 1.

Thrombogenic mechanisms on blood-contacting material surfaces and major antithrombotic modification strategies.

3. Anticoagulant Surface Modification Strategies, Characteristics, and Limitations

3.1. Carbon-Based Bio-Inert Coatings

3.1.1. Pyrolytic Carbon Coatings

Due to the relatively harsh working and operating conditions, the surfaces of implantable devices such as mechanical heart valves require highly reliable and fatigue-resistant anticoagulant coatings [13,14]. Among these, Low-Temperature Isotropic Pyrolytic Carbon (LTIC) is a relatively successful anticoagulant coating for clinical use in mechanical heart valves due to its favorable hemocompatibility, wear resistance, and fatigue resistance [15]. However, even after implantation, patients must undergo long-term anticoagulant therapy [16]. Furthermore, in areas subject to repeated wear, such as the hinge regions of valves, the pyrolytic carbon coating may generate wear debris in the form of carbon particles, posing a risk of blood contamination [17].

3.1.2. Diamond-like Carbon (DLC) Films

Addressing the shortcomings of pyrolytic carbon in terms of anticoagulant performance and long-term wear resistance, DLC coatings were earlier employed as improved coatings for the surface modification of medical devices [18,19,20]. Furthermore, doping DLC coatings can further enhance their hemocompatibility. T. Saito et al. used a radio-frequency plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition process to prepare both conventional DLC coatings and F-doped DLC coatings on Si substrates for a comparative study. The results indicated that incorporating F into the DLC coating effectively reduced platelet adhesion [21]. T. Hasebe et al. also used the same method to prepare F-doped DLC coatings on polycarbonate surfaces, effectively reducing platelet adhesion and activation on the coating surface [22]. Research by T.I.T. Okpalugo et al. on Si-doped DLC coatings showed that Si doping also further improved the hemocompatibility of the coating [23]. Elemental doping typically enhances the anticoagulant performance by influencing factors such as the surface energy and surface charge distribution of the DLC coating.

However, the anticoagulant mechanism of DLC coatings remains highly debated. While their anticoagulant properties are correlated with chemical composition, type of chemical bonds, surface energy, surface charge distribution, and tribological properties, a widely accepted mechanistic model for the anticoagulant behavior of DLC coatings has not yet been established, and their anticoagulant performance still requires further improvement. Additionally, medical devices generate residual stress during use. When the adhesion between the DLC coating and the substrate is insufficient, high residual stress can cause coating delamination and cracking. The resulting detached particles can have adverse effects, which is a problem that needs to be resolved [24].

In summary, pyrolytic carbon coatings are clinically used but require lifelong anticoagulation and risk shedding debris. Doped DLC coatings show enhanced hemocompatibility, yet their exact anticoagulant mechanism remains unclear, limiting rational optimization. A more critical barrier is mechanical; high residual stress and poor adhesion can cause catastrophic coating delamination, generating hazardous particles. These unresolved mechanical and mechanistic issues are the primary obstacles to their reliable long-term use.

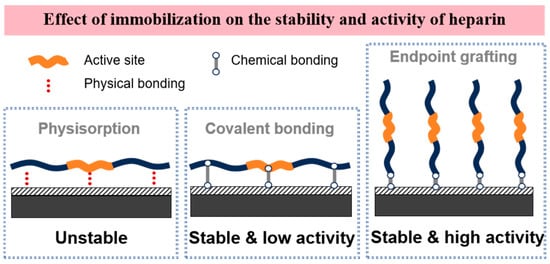

3.2. Heparin-Based Drug Coatings

Heparin is a linearly structured anionic polysaccharide containing carboxyl, sulfonic acid, and sulfonamide functional groups. It is a natural anticoagulant substance and the most extensively studied among anticoagulant drugs. Heparin exerts its anticoagulant effect by binding to antithrombin, enhancing its ability to inhibit coagulation proteases such as thrombin and factor Xa [25,26,27]. The efficiency of heparin coatings in preventing non-specific adhesion and thrombin generation depends on the stability of the heparin coating and whether the heparin molecules retain their biological activity after the modification process. Current methods for immobilizing heparin on surfaces primarily include physical adsorption, covalent bonding, and end-point immobilization (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Three typical methods for immobilizing heparin molecules on material surfaces.

Physical Adsorption Immobilization: The physical adsorption of heparin results in an unstable coating. Typically, heparin coatings applied via physical adsorption lose their anticoagulant activity shortly after use, exhibiting anticoagulant properties similar to uncoated samples, making them unsuitable for applications requiring long-term anticoagulation.

Covalent Bonding Immobilization: Covalent immobilization of heparin is a crucial method for improving its stability. Each heparin molecule possesses several free carboxyl groups that can form multiple covalent bonds with other functional amino or hydroxyl groups on the biomaterial, resulting in strongly bound, covalently fixed heparin. Although various covalent bonds can immobilize heparin more stably on the surface, this non-specific fixation impairs the free movement of the heparin molecules, thereby limiting the biological activity of the heparin coating.

End-point Immobilization: End-point immobilization of heparin involves attaching the chain end of the heparin molecule to the substrate via a single covalent bond, thereby preserving the biological activity of its natural structure. Compared to multi-covalent bonding methods, surfaces with end-point immobilized heparin significantly reduce platelet activation and adhesion, as well as the activation of the coagulation cascade. Consequently, end-point immobilization allows for compatibility between the stability of the surface heparin coating and molecular activity, resulting in optimal long-term anticoagulant efficacy [28].

The drawback of heparin coatings lies in the fact that heparin can also bind to plasma proteins other than antithrombin, such as fibronectin and growth factors. This non-specific binding can reduce the anticoagulant activity and efficiency of the heparin coating. Furthermore, under high shear stress conditions, heparin is prone to depletion and leaching from the surface, leading to a gradual loss of its anticoagulant properties.

To better utilize the anticoagulant efficacy of heparin coatings, the combined use of heparin with other components is a current research focus. For instance, various composite systems have been developed and studied, demonstrating potentially enhanced anticoagulant performance. These include heparin-phosphorylcholine coatings [29], heparin-hyaluronic acid-dopamine coatings [30,31], heparin-lysine-dopamine coatings [32], heparin-collagen coatings [33], heparin-graphene coatings [34], and core–shell structured PCL-PEG-heparin coatings [35]. Heparin coatings and their composite coatings have been extensively researched and applied in medical devices such as vascular stents [36,37], catheters [38,39], artificial blood vessels [40,41], and extracorporeal circulation systems [42].

For a short summary, heparin coatings leverage their natural antithrombin activity for hemocompatibility, but their clinical success hinges on immobilization stability. While end-point covalent attachment best preserves bioactivity, challenges persist: non-specific plasma protein binding diminishes local efficacy, and shear-induced leaching can deplete the coating. Research increasingly focuses on composite systems to improve durability, yet creating a stable, fully functional heparinized surface that mimics endogenous performance remains a key unmet challenge.

3.3. Hydrophilic Coatings

Hydrophilic coatings tightly bind water molecules through polar groups on their molecular chains, forming a dense hydration layer. This layer creates a high-energy barrier via an entropic shield, significantly reducing non-specific adsorption of plasma proteins through the “excluded volume effect” and “steric hindrance effect”, thereby inhibiting platelet adhesion and activation and imparting anticoagulant function.

3.3.1. Phosphorylcholine (MPC) Polymers

The development of zwitterionic materials like MPC with chemical structure of (H2C=C(CH3)-C(=O)-O-CH2-CH2-O-P(O−)(O−)-O-CH2-CH2-N+(CH3)3) was inspired by the natural bio-inertness of the outer surface of cell membranes, which are rich in phospholipids with zwitterionic head groups, granting them inherent antifouling and anticoagulant properties [43,44,45]. Among zwitterionic structural materials for blood contact, polymers containing the phosphorylcholine (PC) group are the most promising. The low yield and purity of the first-generation synthetic PC polymers led to the development of a novel compound, 2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine (MPC). A simplified synthesis process enabled the production of MPC in large quantities with high purity, facilitating considerable progress in developing various MPC polymers for blood-contact applications and establishing MPC coatings as a commercial system comparable to heparin coatings. MPC polymers possess an equal number of cationic and anionic groups on their polymer chains. This unique characteristic makes them highly hydrophilic and resistant to non-specific adhesion [46,47]. Furthermore, as MPC is a biomimetic cell membrane coating, it exhibits good bio-inertness, causes minimal irritation to human tissues, and is less likely to induce inflammatory or toxic reactions.

MPC coatings have been extensively studied for use in hemodialyzers [48], vascular stents [49,50], medical catheters [51,52], extracorporeal circulation systems [53,54], and artificial hearts [55]. For vascular stents, MPC coatings can selectively promote the adhesion and proliferation of vascular endothelial cells, facilitating the rapid formation of a functional cell layer (endothelialization) on the implant surface, achieving “bio-integrated healing”, while simultaneously inhibiting the excessive proliferation of smooth muscle cells, helping to reduce the risk of in-stent restenosis. Researchers are enhancing coating-substrate adhesion by using intermediate bonding layers, such as polydopamine [56,57,58], or developing MPC-polymer interpenetrating network structures to improve coating stability [59,60,61].

MPC coatings have achieved large-scale commercial application [45,46,47]. For example, companies such as Japan’s NOF have established mature MPC polymer synthesis systems and have commercialized products through technological routes like surface grafting and blending modification. Companies like JMedtech have successfully applied phosphorylcholine anticoagulant coatings (jHemo PC®) to various implantable and interventional medical devices, including covered stents, introducer sheaths, artificial blood vessels, neurointerventional catheters/guidewires, and hemodialysis tubes. Existing clinical data on MPC anticoagulant coatings primarily focus on the fields of blood purification, cardiovascular interventional devices, and extracorporeal circulation systems. In short-term blood-contact devices, MPC coatings have established their important position. However, their expansion into long-term implantation still requires addressing issues of interfacial stability and functional durability, such as the need to improve wear resistance in high-shear environments (e.g., heart valves).

As a brief summary, MPC polymers are established biomimetic coatings that reduce protein fouling. Their primary challenge for long-term implants is durability: mechanical wear, oxidative degradation, and biofouling eventually compromise coating integrity. Enhancing interfacial adhesion and stability via crosslinking or composite materials is the current research focus. Ultimately, evolving from passive antifouling to an actively bioactive interface is key to unlocking their use in durable devices.

3.3.2. PEG Coatings

PEG (H-(-O-CH2-CH2-)n-OH) molecular chains contain a large number of ether bonds (-C-O-C-), which form a dense hydration layer through hydrogen bonding. Its flexible long chains adopt a random coil conformation, creating a thermodynamic repulsion via steric hindrance effects. Simultaneously, the high mobility of the chain segments induces an excluded volume effect, collectively preventing the adsorption of proteins and other molecules. Furthermore, its low interfacial free energy significantly reduces the driving force for the adhesion of proteins and platelets. Even minimal protein adsorption can maintain the natural conformation, avoiding the exposure of platelet-binding sites, thereby effectively blocking platelet adhesion, activation, and aggregation [62,63,64].

Methods for constructing PEG coatings primarily include surface graft polymerization, chemical conjugation, and blending with block copolymers [65,66]. Additionally, researchers have combined it with peptides [67,68], heparin [69], collagen [70], protease inhibitors [71], or formed block copolymers [72,73] to further enhance its anticoagulant efficacy.

PEG coatings still exhibit significant limitations. Firstly, the chemical stability of PEG chains is relatively poor, as the ether bonds within them are susceptible to attack by reactive oxygen species (ROS) in vivo, leading to oxidative degradation, structural damage, and functional failure of the coating. Secondly, the anticoagulant efficacy is highly dependent on parameters such as chain length [74,75] and grafting density [76,77]. Low density or short chains cannot form a complete barrier, while excessively dense grafting restricts the flexibility of the molecular chains, making precise control of this balance challenging. Additionally, the binding strength between the coating and the substrate is often insufficient, making it prone to detachment under the shear stress of blood flow. The primary obstacle lies in the inability to resolve the long-term degradation issue. In terms of clinical validation, PEG coatings currently meet the requirements only for short-term devices (such as intravenous catheters, interventional guidewires, and sensors), with application cases primarily focused on usage scenarios ranging from several hours to a few weeks. For long-term implants like vascular stents, there is a lack of large-scale clinical data supporting their efficacy and safety beyond one year.

For a short summary, PEG coatings, a classic anticoagulant strategy, function by forming a dense, flexible hydration layer that resists protein and platelet adhesion. However, they face significant challenges for long-term applications. Their ether bonds are vulnerable to oxidative degradation in vivo, and their performance is highly sensitive to difficult-to-optimize parameters like chain length and grafting density. Crucially, coating stability under shear stress is often insufficient. While suitable for short-term devices (e.g., catheters), the unresolved issue of long-term durability, coupled with a lack of robust clinical data for implants, limits their broader application.

3.3.3. Hydrogel Coatings

Hydrogel coatings are hydrophilic polymer materials with a three-dimensional network structure that mimics biological soft tissues through their high water content, effectively reducing interactions between the material surface and blood components. When a hydrogel coating contacts blood, the large amount of water molecules bound within its network structure forms a dynamic hydration layer, inhibiting the non-specific adsorption of plasma proteins [78].

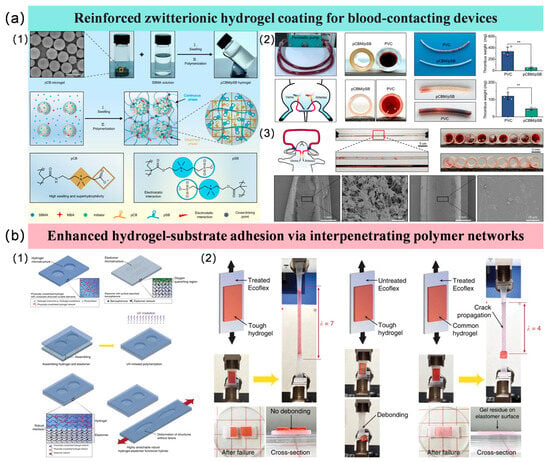

Li et al. reported a poly (carboxybetaine) microgel-reinforced poly (sulfobetaine) (pCBM/pSB) zwitterionic hydrogel coating [79]. Figure 3(a1) illustrates the construction and microstructure of the pCBM microgel-reinforced hydrogel. The microgels form a uniformly dispersed phase within the pSB network, creating a unique two-phase structure together with the sparsely cross-linked, continuous pSB phase. This architecture enables effective “locking” of the entire matrix and efficient energy dissipation, which is key to conferring the hydrogel with superior mechanical robustness and anti-swelling properties. The antithrombotic properties of the pCBM/pSB hydrogel coating were systematically evaluated through animal experiments. In dynamic in vitro circulation and ex vivo rat perfusion models, as shown in Figure 3(a2), the coating reduced thrombus weight and significantly decreased platelet adhesion and activation. Further evaluation in a New Zealand white rabbit arteriovenous shunt model (Figure 3(a3)), which more closely mimics clinical conditions, showed that the coating dramatically reduced the occlusion rate, with only a small number of non-activated blood cells observed on the surface. These consistent results demonstrate that the hydrogel coating effectively inhibits thrombus formation, exhibiting excellent anticoagulant performance and promising potential for clinical translation.

Appel et al., through screening 11 different pairwise combinations of acrylamide monomers [80], selected the hydroxyethyl acrylamide/diethyl acrylamide copolymer combination, which exhibited minimal non-specific protein adsorption, as the preferred system and prepared a combinatorial hydrogel coating on a biosensor surface. This hydrogel coating showed good anti-thrombus contamination performance in both in vitro and in vivo experiments. Compared to a PEG coating, it resulted in a significantly smaller deviation from the original signal due to enhanced anti-thrombus contamination performance, indicating promising application prospects for hydrogel coatings in improving sensor performance by resisting thrombus formation. Furthermore, by combining hydrogel coatings with heparin [81], nitric oxide-releasing coatings [82], peptides [83,84], etc., composite hydrogel coatings with improved anticoagulant properties can be constructed. Currently, hydrogel coatings have shown potential in medical devices such as extracorporeal circulation systems [85,86], artificial blood vessels [87], and artificial heart valves [88]. The stability of anticoagulant hydrogel coatings requires good adhesion to the substrate.

Strategies for bonding the coating to the substrate can be broadly categorized as follows [89,90,91,92,93,94]: (1) Physical interlocking utilizing surface topography or porous structures. (2) Forming chemical bonds between the hydrogel polymer and the substrate material using agents like silane coupling agents. (3) Creating an interpenetrating network connection between the hydrogel polymer and the substrate polymer.

As shown in Figure 3(b1), researchers propose a general method to construct elastomer-hydrogel hybrids that feature robust interfaces and functional microstructures [94]. The key steps are: firstly, a physically crosslinked hydrogel that can maintain its pre-shaped form is prepared, with infiltrated monomer solution for a subsequent stretchable network; the elastomer surface is treated via swelling to absorb benzophenone, which overcomes oxygen inhibition and serves as a UV-assisted grafting agent; finally, the pre-formed hydrogel and elastomer are assembled and subjected to UV light to initiate grafting and crosslinking, forming a strong interface. This method is not material-specific and is applicable to a variety of common elastomer and tough hydrogel systems. The high interfacial strength of the fabricated hydrogel-substrate material was verified, as shown in Figure 3(b2). The composite of PAAm-alginate hydrogel and Ecoflex elastomer substrate could be stretched up to seven times its original length without delamination, with the interface remaining intact even after bulk fracture. In contrast, the untreated control group detached under minimal deformation. Even for a brittle conventional PAAm hydrogel, this method enabled interfacial stretchability up to four times.

Additionally, introducing energy dissipation phases into the hydrogel, such as uniformly dispersed gel microspheres or dispersed phase long-chain molecular networks, can increase energy dissipation under external force, endowing the hydrogel coating with better mechanical properties and stability. Hydrogel coatings also face some drawbacks.

The primary failure mechanisms of hydrogel coatings under physiological shear conditions are hydration layer erosion and interface instability [78,79,80]. Under continuous blood flow shear stress, bound water molecules on the coating surface are progressively stripped away, leading to the degradation of the integrity and stability of the dynamic hydration barrier. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced in regions of turbulent flow or rapid changes in shear direction, where localized weakening of the hydration barrier creates footholds for the adsorption of plasma proteins. This initial protein adsorption serves as the critical first step toward platelet adhesion and thrombus formation. Simultaneously, the swelling behavior of hydrogels in physiological environments poses another significant risk. As hydrogels absorb water and expand, significant swelling stress is generated. If the adhesion strength between the hydrogel and the substrate material is insufficient to counteract this stress, it can result in coating delamination, wrinkling, or the formation of microcracks. The loss of coating integrity exposes the underlying pro-thrombogenic substrate, leading to a complete failure of the anticoagulant function. Surface degradation and molecular chain scission represent another major failure pathway. Hydrolysable bonds, such as ester linkages within the polymer network, are susceptible to cleavage in the physiological environment. Furthermore, reactive oxygen species and enzymes released by inflammatory cells can oxidize or enzymatically degrade the polymer chains, particularly in polyesters or hydrogels containing oxidizable functional groups.

Figure 3.

Anticoagulant applications of hydrogel coatings and their enhancement methods. (a1) The construction of the pCBM microgel-reinforced hydrogel; (a2) Animal experiments in dynamic in vitro circulation and ex vivo rat perfusion models; (a3) Animal experiments in a New Zealand white rabbit arteriovenous shunt model [79]; (b1) A general method to construct elastomer-hydrogel hybrids that feature robust interfaces; (b2) High interfacial strength of the fabricated hydrogel-substrate material [94].

In summary, hydrogel coatings leverage a hydrated barrier to resist thrombosis, but their clinical use is limited by poor mechanical durability. They are prone to wear and delamination under blood flow shear, which can expose the underlying material and trigger clotting. Current research focuses on strengthening adhesion and toughness, yet achieving reliable long-term stability in demanding applications like stents or heart valves remains a major challenge.

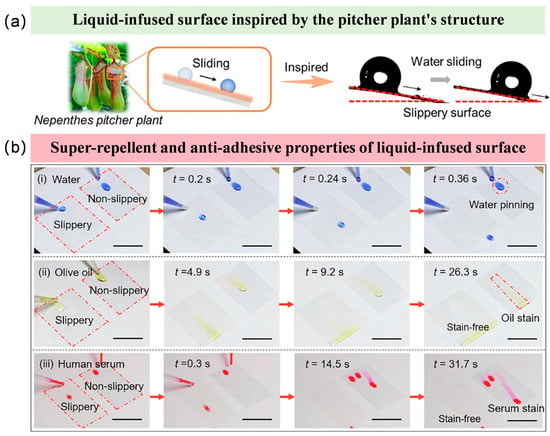

3.4. Hydrophobic Liquid-Infused Surfaces

Inspired by the lubricated interface of the pitcher plant’s trapping zone (Figure 4a), a liquid-infused surface can be constructed [95,96,97]. The mechanism involves impregnating a low-surface-energy modified porous substrate with a lubricant that exhibits affinity to the substrate and is immiscible with the surrounding medium, thereby forming a molecularly smooth, physically self-healing, and stable interfacial layer. This interface can significantly reduce droplet adhesion and sliding angles, achieve an ultralow friction coefficient, and impart self-cleaning functionality, demonstrating significant potential in applications such as anti-biofouling and microfluidic manipulation.

The liquid-infused surface exhibits efficient repellency against various media such as water, olive oil, and human serum, with droplets sliding off rapidly without leaving residues, as shown in Figure 4b. In contrast, the control surface shows significant droplet pinning and contaminant adhesion. These results demonstrate that the liquid-infused surface effectively inhibits contamination retention, possessing excellent anti-fouling and self-cleaning properties, showing significant potential for anticoagulant applications by resisting the adhesion of blood components [98].

The anticoagulant design of liquid-infused surfaces creates an interface with extremely weak interactions, effectively reducing fibrinogen adsorption and platelet activation on the surface of implantable materials, thereby minimizing thrombus formation [99,100]. Polymer catheters utilizing liquid-infused surfaces have demonstrated excellent anticoagulant performance in both in vitro and in vivo experiments. C. Leslie Daniel et al. created a lubricant (PFD) infused surface on polymer catheter materials (polyurethane cannulae, polycarbonate connectors, and PVC perfusion tubes) [101]. An 8 h in vivo (porcine) evaluation without heparin showed that the experimental catheters had higher patency rates and less thrombus formation compared to the control group. Teryn R. Roberts et al. developed liquid-infused surfaces for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) circuits [102,103,104] and conducted 6 h and 72 h in vivo evaluations in pigs under higher flow rate conditions (1 L/min). In the 6 h in vivo experiment, the experimental group showed better anticoagulant properties than the control group (heparin-coated catheters), indicating the potential of liquid-infused surfaces for short-term blood-contact applications. However, in the 72 h experiment, the liquid-infused surfaces exhibited insufficient stability, leading to anticoagulant properties inferior to the control group (heparin-coated catheters with continuous heparin infusion). The stability issue of liquid-infused surfaces under prolonged blood flow shear stress poses a challenge for their clinical application.

Liquid-infused surfaces rely on a low-surface-energy infusion liquid phase locked within micro/nanostructured surfaces to form a defect-free, dynamically sliding anti-adhesion interface [95]. The core of their failure lies in the loss of the infusion liquid phase and physical damage to the surface structure. Under physiological shear conditions, the viscous shear force exerted by blood flow continuously drags on the infusion liquid layer, causing the liquid to be gradually “washed away” [101]. When the surface comes into contact with complex biological fluids such as blood, surfactants in the blood (e.g., phospholipids, proteins) may partially displace the infusion liquid phase, reducing its sliding performance. Additionally, clogging of the LIS surface topography is a significant cause of failure, as blood-derived debris such as cell fragments, lipoproteins, and fibrin clots can invade and block these pores, disrupting the capillary mechanism for infusion liquid replenishment and self-repair. Once the pores are clogged, the infusion liquid cannot be replenished after loss in that region, directly exposing the structured substrate. This localized exposure drastically promotes massive protein adsorption and platelet activation, becoming a nucleation site for thrombus formation. Moreover, certain components of the infusion liquid phase may be slowly degraded by lipases or reactive oxygen species in the plasma, altering their rheological properties and surface energy.

Caitlin Howell et al. investigated the stability and failure mechanisms of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)-based liquid-infused surfaces interacting with fluid (water) in microfluidic channels [105], focusing primarily on two aspects: (1) The failure characteristics under different substrate surface structures, such as the failure of lubricant infused on flat versus nanostructured surfaces under different fluid shear rates. It was concluded that nanostructured surfaces can more effectively retain the lubricant and reduce its loss. (2) The impact of introducing a gas phase into the shear fluid on lubricant loss and failure. When the shear fluid is a single-phase medium (water), lubricant failure manifests as its stripping under shear stress. When a gas phase appears in the shear fluid and the gas/liquid interface contacts the lubricant surface, due to the three-phase interfacial tension relationship, the lubricant (Krytox 103) aggregates at the liquid/gas interface and is carried away into the shear fluid as the interface moves. This implies that for certain lubricant components, changes in the composition of the shear fluid can cause a significant shift in the dominant failure mode of the lubricant—from mechanical stripping mediated by shear stress to interfacial aggregation and loss determined by surface energy relationships. Research analysis indicates that the latter failure mode can drastically accelerate lubricant depletion. Enhancing the stability of liquid-infused surfaces under complex shear flow conditions is key to promoting their clinical application [106,107,108].

Figure 4.

Biomimetic liquid-infused surface and its anti-adhesion characteristics. (a) Liquid-infused surface mimicking the slippery surface of the pitcher plant [107]; (b) Super-repellent and anti-adhesive properties of the liquid-infused surface against (i) water; (ii) olive oil and (iii) human serum. [108].

For a brief summary, liquid-infused surfaces form a lubricated interface that effectively prevents thrombosis in the short term. However, their long-term functionality is critically limited by lubricant loss under physiological shear. Lubricant depletion, accelerated in multiphase flow, causes the coating to fail. While nanostructured substrates can improve retention, achieving durable lubricant stability in complex blood flow remains the key barrier to clinical use.

3.5. Endothelium-Mimetic Nitric Oxide-Releasing Coatings

Nitric oxide (NO) is a key endogenous signaling molecule secreted by vascular endothelial cells and plays a central role in maintaining vascular homeostasis and blood fluidity. NO inhibits platelet adhesion, activation, and aggregation primarily by activating guanylyl cyclase within platelets, leading to increased cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) levels [109]. Furthermore, NO can inhibit the excessive proliferation of smooth muscle cells, thereby helping to prevent restenosis after vascular stent implantation [110]. The primary goal of nitric oxide-releasing coatings is to achieve controlled and sustained release of NO from the material surface, mimicking the function of the natural vascular endothelium. Current main construction strategies can be classified into three categories:

Physical doping or embedding of NO donors [111,112]: Small-molecule NO donors are physically blended/loaded into a biocompatible polymer matrix. When the coating contacts blood, water penetrates the matrix, triggering the hydrolysis or thermolysis of the NO donors, thereby releasing NO. This strategy offers simple preparation, high NO loading capacity, and a fast initial release rate. However, sustained long-term NO release is challenging, and stability can be insufficient.

Chemically bound NO-releasing coatings [113,114]: NO donor molecules are covalently anchored to the material surface or polymer backbone via chemical means. This strategy significantly improves the stability of the NO-releasing layer, resulting in more stable and prolonged NO release. However, the preparation process is relatively complex, and the limited available grafting sites often result in relatively low total NO loading capacity and flux.

Catalytic NO-generating coatings [115,116]: These coatings immobilize a catalyst that functions similarly to nitric oxide synthase (NOS) in endothelial cells. After implantation, these catalysts utilize endogenous NO precursors naturally present in the blood to catalyze their decomposition, generating NO in situ. The greatest potential of this strategy lies in its ability to achieve “on-demand” and long-term NO release by leveraging the continuous supply of endogenous precursors. However, the long-term maintenance of catalytic activity and biosafety is a critical issue requiring thorough evaluation.

Table 1 shows a comparison between different NO-releasing strategies. Physically doped/embedded NO donors can achieve a high initial NO flux (typically > 1.0 × 10−10 mol·cm−2·min−1), but the release profile is often burst-like, with a short duration (ranging from hours to days) [111], making it difficult to meet the requirements for long-term implantation. Chemically bound NO-releasing coatings exhibit a relatively lower but more stable NO flux (approximately 0.5–1.0 × 10−10 mol·cm−2·min−1), enabling more sustained release (from days to weeks) and significantly improved stability. Catalytic NO-generating coatings hold potential for “on-demand” release, where the flux depends on the concentration of endogenous precursors (such as nitrite) in the blood. The goal is to match the NO flux of healthy endothelial cells (approximately 0.5–4.0 × 10−10 mol·cm−2·min−1) to achieve long-term, physiologically relevant anticoagulant effects [116].

Table 1.

The NO flux and some characteristics of different NO-releasing strategies.

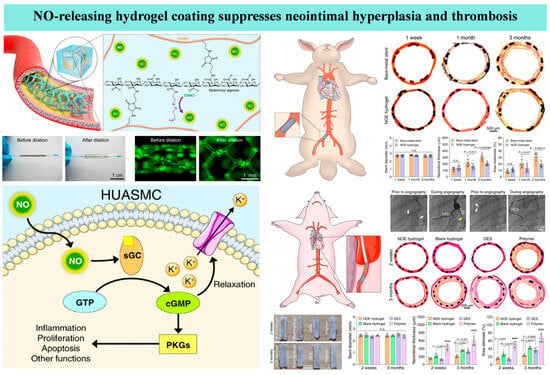

Furthermore, researchers have combined NO-releasing coatings with other anticoagulant strategies such as heparin and hydrogels [117,118,119], creating synergistic effects for improved overall anticoagulant function (Figure 5). Currently, NO-releasing coatings show significant application potential for the anticoagulant modification of medical devices, including extracorporeal circulation systems [120,121], stents [122,123], and catheters [124].

Figure 5.

A hydrogel coating with nitric oxide (NO)-releasing functionality applied to a vascular stent surface can inhibit thrombosis and in-stent restenosis [119].

For a summary, Nitric oxide (NO)-releasing coatings mimic the endothelium to locally inhibit thrombosis. The core challenge is achieving a sustained, controlled release. While physical doping provides a high initial burst and covalent bonding improves stability, catalytic generation from blood precursors offers the most promising route for long-term, on-demand release. However, maintaining catalytic activity and ensuring biosafety over time are unresolved. The key translational hurdle is balancing sufficient NO flux with long-term coating stability.

3.6. Endothelialized Surfaces

Vascular endothelial cells (ECs), located between the plasma and vascular tissue, not only facilitate metabolic exchange but also synthesize and secrete various bioactive substances to maintain normal vascular contraction and relaxation, regulate vascular tone and blood pressure, and balance coagulation and anticoagulation. They act as a physical barrier, isolating blood from the highly thrombogenic subendothelial matrix. Furthermore, they secrete nitric oxide (NO) and prostacyclin, effectively inhibiting platelet activation and aggregation. Their surface expression of thrombomodulin activates the potent protein C anticoagulant pathway, while membrane-bound heparan sulfate proteoglycans significantly enhance antithrombin activity, inactivating key coagulation factors [125,126,127]. Therefore, establishing a healthy and confluent endothelial layer on newly implanted vascular grafts, stents, and heart valves is crucial for preventing thrombosis and other complications.

The realization of endothelialization primarily relies on two major strategies: surface biofunctionalization and cell capture/seeding techniques. Surface biofunctionalization focuses on creating a biomimetic microenvironment on the material surface that actively guides endothelial cell behavior. This includes:

Immobilizing cell adhesion peptides (e.g., YIGSR [128,129] and REDV peptide [130,131], which show high selectivity for endothelial cells) to mediate specific cell adhesion. Immobilizing biosignaling molecules like Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) [132] to promote cell migration and proliferation. Constructing biofunctional interfaces using natural extracellular matrix (ECM) components (e.g., collagen, fibronectin) [133] to provide endothelial cells with a microenvironment containing specific adhesion ligands and mechanical cues, thereby precisely regulating their adhesion, spreading, and functional expression. Building on this, endothelialization can be achieved through in vitro pre-seeding or in situ capture [134]. In vitro pre-seeding involves culturing autologous or allogeneic endothelial cells into a confluent layer on the material surface before implantation. This method is reliable but faces challenges related to cell source, long culture periods, and potential cell detachment during surgery. The in situ capture strategy uses surface-immobilized antibodies (e.g., anti-CD34 antibodies) or aptamers to specifically capture endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) directly from the circulating blood, enabling their attachment at the implantation site and differentiation into functional endothelial cells, representing a more intelligent form of “in vivo tissue engineering.”

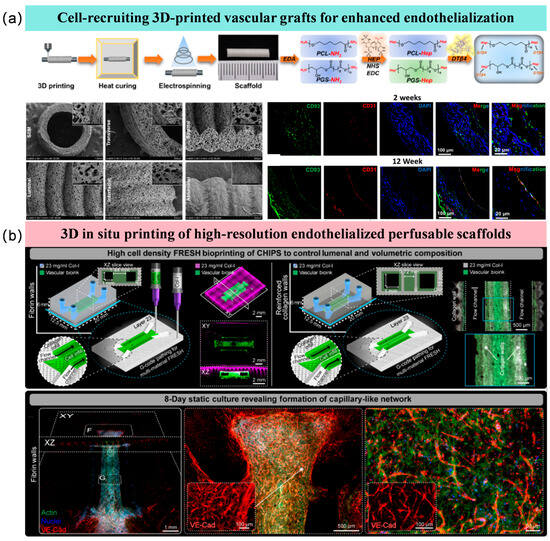

Furthermore, the combination of endothelialization technology and 3D printing has been a research hotspot in recent years. Three-dimensional bioprinting is a promising method in vascular tissue engineering, enabling the construction of continuous hollow fibers and complex interconnected 3D networks usable as vascular channels. Methods for achieving endothelialization within these channels primarily include (Figure 6a,b): post-printing cell recruitment for endothelialization and in situ endothelialization by loading endothelial cells within the bioink [135,136]. For instance, 3D printing technology can create high-precision, perfusable scaffolds. By co-depositing endothelial cells mixed with biomaterials as “bioink” during the printing process, in situ endothelialization can be achieved [137]. However, in situ 3D bioprinting of endothelium faces dual challenges of printing precision and mechanical strength. High cell density increases light scattering, significantly reducing printing resolution, making precision control critical [138]. Additionally, the printed structure requires sufficient mechanical strength to maintain its shape and withstand external pressures, making the selection of bioinks loaded with endothelial cells crucial [139].

Figure 6.

Three-dimensional printing endothelialization strategies using different approaches. (a) Endothelialization via cell recruitment after 3D printing [135]; (b) In situ endothelialization by loading endothelial cells within the bioink [137].

A functionally intact and stable endothelial cell layer on a material surface requires endothelial cells to form a continuous, gapless monolayer structure, achieving mechanical coupling through tight junction proteins and adhesion junction proteins [125,126]. The cells should align their long axis parallel to the direction of blood flow, with a well-organized intracellular actin cytoskeleton to avoid pathological contraction morphology. The cells must consistently express classic endothelial markers (such as CD31, vWF, and eNOS) and anticoagulant-related molecules, where active eNOS expression is critical for maintaining steady-state nitric oxide (NO) release [129]. In dynamic flow systems, the endothelial layer must withstand physiological-level shear stress and remain adherent without detachment over extended periods. The cell–matrix anchoring strength can be evaluated by assessing the binding strength between integrins and surface-immobilized peptides to prevent delamination under high shear stress. Regarding long-term functional performance, a functional endothelial layer should sustainably release NO and prostacyclin, while demonstrating minimal platelet adhesion density in whole blood perfusion experiments. Additionally, it must exhibit damage repair capabilities and the ability to suppress smooth muscle cell hyperplasia.

Among the various strategies, endothelialized surfaces are regarded as the most promising direction for long-term (exceeding several years) implants [134]. Their fundamental advantage lies in their aim to transcend mere “interference resistance” or “drug release,” ultimately seeking to reconstruct a living, functionally normal vascular endothelium on the surface of the implant. This natural layer of endothelial cells can dynamically secrete active substances such as nitric oxide (NO) and prostacyclin, while also expressing thrombomodulin, among other molecules. This physiologically maintains blood fluidity, achieving true “biointegration” and “self-healing.” Theoretically, this approach holds the potential to provide lifelong anti-thrombotic functionality. In contrast, the functionality of other strategies, such as physically inert coatings (carbon-based, hydrogels) or active release coatings (heparin, NO donors), relies entirely on the chemical or physical integrity of the coating material. Under the cyclic loading and complex biological environment over years or even longer periods, these coatings face risks of degradation, wear, or depletion of active components. Once they fail, the underlying pro-thrombotic substrate is exposed. However, if the endothelialization strategy is successful, the living tissue layer it forms can continuously renew itself, thereby overcoming the limited lifespan inherent to synthetic materials.

For a brief summary, endothelialized surfaces, though ideal for blood compatibility, face clinical hurdles: ensuring endothelial cell stability and function under shear stress, and overcoming technical limitations in 3D bioprinting (e.g., balancing cell density with precision). Aggressive endothelialization risks intimal hyperplasia or detachment, potentially increasing thrombosis. Future efforts should prioritize intelligent interfaces that dynamically regulate cell behavior, moving beyond static mimicry of structures.

3.7. Discussion and Comparison of Different Anticoagulation Strategies

3.7.1. Technical Maturity of Anticoagulation Strategies

Of the existing strategies, carbon-based coatings, heparin coatings, and certain hydrophilic coatings are already in clinical use. Hydrogels, NO-releasing coatings, and endothelialized surfaces are currently in the preclinical research stage, while liquid-infused surfaces and 3D-printed endothelialization technologies remain in the experimental phase. All approaches require further advancements to address challenges related to long-term stability, biosafety, and clinical translation.

3.7.2. Analytical Comparison Between Anticoagulation Technologies

Different anticoagulation strategies exhibit significant differences in inhibiting protein adsorption and resisting shear stress, as shown in Table 2. Passive anti-adsorption strategies (e.g., hydrogels, liquid-infused surfaces) are highly effective at inhibiting protein adsorption (fibrinogen adsorption < 5 ng/cm2), but their critical stable shear stress is low or variable, making them prone to failure due to mechanical wear or lubricant depletion [85,86,96,102]. Bioactive strategies (e.g., heparinized coatings), while less effective at inhibiting protein adsorption, achieve moderate-to-high shear stability through covalent bonding, making them more suitable for medium- to long-term implantation environments. Biointegrative strategies (e.g., endothelialized surfaces) enable functional protein management by forming a natural endothelial layer and exhibit high shear stability after tissue integration, representing an ideal long-term solution [125].

Table 2.

Comparison of protein adsorption and shear stability among different anticoagulation technologies.

To better understand current hot anticoagulation strategies, we analytically compared the hydrophilic coating, liquid-infused surface and endothelialization surfaces approaches, on core mechanism, technology readiness level, key advantages, major limitations and challenges and long-term application prospect, which were shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Analytical comparison between the hydrophilic coatings, liquid-infused surface and endothelialization surfaces approaches.

Hydrophilic coatings, such as those based on PEG or zwitterionic polymers, are the most technologically mature, having achieved clinical use in short-term devices like catheters. Their core mechanism relies on forming a hydration layer that acts as a passive physical and thermodynamic barrier to minimize protein adsorption [64]. They offer good initial hemocompatibility, their long-term stability is limited by susceptibility to hydrolysis, oxidative degradation, and mechanical wear, making their prospect only moderate for permanent implants without significant material improvements. In contrast, liquid-infused surfaces represent a more recent biomimetic approach. They function by creating a slippery, dynamic liquid interface that provides exceptional, broad-spectrum anti-adhesion properties against blood components. However, their technology readiness level remains low-to-medium, as the primary challenge of lubricant depletion under shear stress must be solved [102]. Their long-term application prospect is therefore uncertain and entirely contingent on achieving lubricant stability. Endothelialization stands as the ultimate goal, aiming to create a living, functional endothelial layer that actively secretes anticoagulant factors, offering a truly biological, self-healing solution. This strategy has a medium readiness level, being explored in preclinical and early clinical studies. Its success, however, is hampered by the difficulty in obtaining sufficient functional endothelial cells and risks like hyperplasia leading to restenosis. If these biological challenges can be overcome, it holds the highest potential as the “gold standard” for long-term implants.

3.7.3. Analysis of Integrated Anticoagulation Strategies

When integrating different strategies, additive effects, synergistic effects, or interference effects may occur. For example, in the physical blending of a hydrogel coating with heparin, the hydrogel forms a three-dimensional network structure that acts as a physical barrier to reduce protein adsorption, while heparin inhibits coagulation factors through antithrombin III. Although both coexist in the same coating, their mechanisms of action do not interfere with each other. Similarly, in the combined use of MPC polymer and PEG, both achieve anti-protein adsorption through hydration layers, and their combined effect is merely additive, equivalent to the superposition of two hydrophilic coatings, without surpassing the physical limits of passive anti-adhesion.

Synergistic effects refer to the performance breakthrough achieved through functional complementarity or cascade amplification, where “1 + 1 > 2.” A typical example is the integration of a nitric oxide (NO)-releasing coating with a hydrogel [118,119]. The high-water-content network of the hydrogel can serve as a stable carrier for NO donors, delaying their hydrolysis rate and enabling long-term controlled release of NO. Simultaneously, the antiplatelet function of NO compensates for the hydrogel’s limitations in chemical signaling regulation.

Certain combinations may sometimes exhibit incompatibility. For example, in the integration of heparin with cell-mimetic coatings, heparin must be exposed to the bloodstream and bind to antithrombin III to exert its catalytic effect, whereas cell-mimetic coatings are designed to emulate cell membrane structures to “hide” the material surface, reducing the adsorption of all plasma proteins, including antithrombin III. In the combined application of heparin-based drug coatings and endothelialization strategies, if both heparin and endothelial cell-selective peptides (such as REDV) are immobilized on the surface, heparin may competitively bind to plasma fibronectin or growth factors, reducing the effective enrichment of these proteins on the peptides, thereby delaying endothelial cell migration and functional expression. Moreover, the sustained release of heparin may locally inhibit thrombin activity, whereas an appropriate level of thrombin actually serves as a potential promoter of endothelial cell proliferation and barrier maturation. This interference may result in incomplete endothelial layer morphology or functional immaturity. In the combination of nitric oxide (NO)-releasing coatings and passive anti-adhesion coatings, for instance, when NO donors are doped into high-density polyethylene glycol (PEG) coatings, the steric hindrance of PEG chains may limit the diffusion efficiency of NO molecules into the bloodstream, reducing their bioavailability.

Therefore, synergistic combinations with good compatibility typically adopt a multi-level defense mechanism as the design framework. For example, surface physicochemical modifications (such as zwitterionic polymer brushes) can serve as a primary barrier to non-specifically inhibit uncontrolled plasma protein adsorption. On this basis, bioactive molecule release systems (such as nitric oxide and heparin) can be integrated to construct a secondary defense line for specific anticoagulation and anti-platelet activation. Finally, pro-endothelialization signals (such as cell-selective peptides) can be incorporated to achieve tertiary biological functional re-endothelialization.

3.7.4. Impact of Inter-Individual Biological Variability on the Performance of Anticoagulation Strategies

Individual biological variability is a key factor that cannot be overlooked in determining the clinical efficacy of anticoagulant surface technologies. Passive anti-adhesion strategies, represented by phosphorylcholine polymers, polyethylene glycol, and hydrogels, exhibit relatively high stability and are less influenced by individual differences. Their primary anticoagulant mechanism relies on forming a physical barrier to inhibit non-specific protein adsorption. The performance of these technologies depends more on the physicochemical properties of the materials themselves, such as the integrity of the hydration layer and surface energy. As a result, their performance remains relatively stable despite variations in protein composition, concentration, or coagulation factor levels in the blood of different patients.

In contrast, active biological signaling modulation strategies, such as heparin coatings and nitric oxide-releasing coatings, are highly sensitive to individual physiological states. Their effectiveness is directly influenced by the patient’s physiological microenvironment. The efficacy of heparin coatings depends on the patient’s endogenous antithrombin III levels. In patients with congenital or acquired antithrombin III deficiency, the coating’s effectiveness may be significantly diminished or even trigger heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Similarly, the performance of nitric oxide-releasing coatings is modulated by factors such as patient platelet reactivity and endogenous oxidative stress levels. These variations can affect the effective concentration and duration of NO in the local microenvironment, thereby influencing its practical ability to inhibit platelet aggregation.

For biointegration and endothelialization strategies, individual regenerative capacity is the decisive factor. The success of endothelialization strategies almost entirely depends on the patient’s own repair potential. Future ideal coating designs should evolve toward “dynamic intelligent responsiveness”—capable of sensing changes in the local blood environment and adjusting their function in real time. This approach will enable personalized and precise anticoagulation tailored to different patients, representing the inevitable path to maximizing clinical benefits.

3.7.5. The Key Molecular and Mechanical Thresholds for Anticoagulant Materials

The design of future high-performance anticoagulant materials is centered on achieving a series of well-defined molecular and mechanical performance thresholds, aiming for precise interaction with the physiological environment and long-term biological stability. At the molecular level, a core objective is to accurately mimic the nitric oxide release function of healthy vascular endothelium, maintaining a physiological flux of approximately 0.5 to 4.0 × 10−10 mol·cm−2·min−1 [140,141]. This effectively inhibits platelet activation and smooth muscle cell proliferation, establishing a critical chemical signaling benchmark for long-term anticoagulation and suppression of intimal hyperplasia. At the same time, for surfaces modified with heparin, their bioactivity must be demonstrated through efficient catalysis of antithrombin III, typically targeting a coagulation factor Xa inhibition rate higher than 1.0 pmol/cm2 [142,143,144]. This aims to construct a locally stable and potent anticoagulant microenvironment. In terms of mechanical performance, materials must meet mechanical conditions compatible with soft tissues, particularly with elastic moduli approaching the mechanical range of natural blood vessels (approximately 0.1–1 MPa) [145]. This reduces tissue damage and abnormal remodeling caused by mechanical mismatch between implants and surrounding tissues, thereby promoting functional integration. Additionally, the interfacial bonding strength between the coating and substrate must be sufficient to withstand long-term hemodynamic shear forces. Its adhesive performance should meet standards such as the 4B or 5B ratings in the ASTM D3359 tape test and maintain structural integrity in simulated physiological flow environments. This ensures that no coating delamination or peeling occurs throughout the intended service life, guaranteeing material reliability and durability.

3.7.6. The Translational Challenges of Anticoagulation Strategies

A variety of anticoagulation strategies have already been translated into commercially available clinical products [3]. For instance, diamond-like carbon (DLC) coatings are utilized in products such as the VentrAssist™ and EVAHEART® for ventricular assist devices, and the Carbofilm™ for artificial heart valves [146,147,148]. Phosphorylcholine-based zwitterionic coatingsare applied on vascular stents like BiodivYsio and TriMaxx™. Heparinized surfaces are employed in medical devices such as the Trillium® coating for medical catheters and the DuraHeart™ and InCOR® for ventricular assist devices [25,149]. Furthermore, endothelialization strategieshave been realized in stent products like Genous™ [150]. The clinical translation of other strategies is still ongoing.

Long-term stability of materials in complex physiological environments is the primary obstacle to clinical translation. For instance, the three-dimensional network structure of hydrogel coatings undergoes swelling and mechanical fatigue under continuous blood flow shear stress, leading to microcrack formation or interfacial delamination, thereby exposing the underlying pro-thrombogenic substrate. Active coatings, such as heparin coatings and nitric oxide (NO)-releasing coatings, face challenges related to the loss or inactivation of active components. Heparin gradually leaches out under blood flow erosion, while the degradation rate of NO donors is difficult to control, making sustained and controlled release unattainable. These stability issues must be thoroughly validated in rigorous long-term animal models.

Scalable manufacturing reproducibility and cost control present another major challenge in transitioning from laboratory prototypes to industrial products. For example, the fabrication of liquid-infused surfaces requires the stable entrapment of lubricant within their micro-nanostructures—a process whose precision and uniformity are exceedingly difficult to maintain during scaled-up production. 3D-printed endothelialization technology is constrained by bioink performance, which must simultaneously satisfy requirements for printing accuracy, mechanical strength, and cell viability, alongside high printing costs and slow production speeds. For all coating technologies, regulatory authorities mandate the establishment of stringent quality management systems to ensure high uniformity in the composition, thickness, and performance of coatings across every production batch, necessitating significant time and financial investments.

Regarding regulatory approval challenges, biocompatibility and long-term biosafety are fundamental prerequisites for authorization. While endothelialization strategies aim to achieve “biointegrated healing,” they face risks associated with cell sourcing, functional maturity, and potential intimal hyperplasia. Overly aggressive endothelialization may lead to restenosis. For novel technologies such as liquid-infused surfaces, the long-term fate of the infused liquid or its degradation products in vivo—including risks of embolism or inflammatory reactions—must be rigorously evaluated. Furthermore, disruptive technologies like 3D-printed tissue-implant composites fall under the category of “combination products.” Their regulatory pathways are complex, with review standards still evolving, requiring extensive preliminary communication between companies and regulatory agencies, thereby increasing approval uncertainty.

3.7.7. Analysis of Production Stability and Costs for Anticoagulation Strategies

Carbon-based coatings, represented by pyrolytic carbon and diamond-like carbon, rely on high-temperature vacuum processes such as chemical vapor deposition. While such processes are well-established in industries like semiconductors, their application in the medical field demands extremely high precision in process parameter control and exceptional cleanliness of the production environment. This ensures the chemical purity, structural consistency, and defect-free nature of the coatings. Consequently, the primary cost drivers for these coatings include substantial equipment investment, stringent process monitoring, and rigorous quality testing.

The core challenge in the large-scale production of heparin coatings lies in maintaining consistent biological activity of the heparin molecules and achieving reproducible immobilization processes. While physical adsorption is simple and low-cost, the resulting coatings are unstable and essentially unsuitable for long-term implants. Covalent bonding and end-point immobilization methods involve complex surface chemical reactions, requiring the introduction of specific reactive groups onto the substrate. During production, parameters such as the pH, temperature, concentration of the reaction solution, and reaction time must be precisely controlled. These factors constitute the production expenses for high-performance heparin coatings.

The synthesis of MPC polymers, PEG, and hydrogels involves polymerization and cross-linking reactions. High-purity specialty monomers, such as MPC, are relatively expensive. The thickness and swelling behavior of hydrogel coatings are critical to their performance, yet achieving a uniform coating on the complex geometries of implants during large-scale production is highly challenging. Poor wear resistance of the coatings may lead to damage during device delivery, increasing scrap rates and thereby elevating costs.

In the large-scale manufacturing of liquid-infused surfaces, ensuring consistent and defect-free microstructures across all product surfaces presents significant difficulty and high costs. Issues such as the evaporation or migration of the infused liquid during long-term storage, sterilization, and use pose stability challenges that manufacturers must address.

Endothelialized surfaces and 3D printing represent the most complex and costly category among all strategies. The functionalization of endothelialized surfaces, such as immobilizing specific peptides or antibodies, requires the use of high-purity bioactive molecules, which are costly. The entire production process must be conducted under stringent aseptic conditions, significantly increasing manufacturing complexity and cost. For 3D-bioprinted endothelialization, specialized bioinks must not only support cell viability but also possess printability and sufficient mechanical strength, making their development highly challenging. The printing process demands precise control of parameters such as temperature and pressure to preserve cell viability. The post-printing culture phase requires complex bioreactors to provide nutrients and mechanical stimulation. The entire workflow is time-consuming, lacks standardization, and results in exorbitant costs.

3.7.8. Experimental Conditions Capable of Simulating the Real Hemodynamic Environment for Anti-Coagulation Strategies

To accurately simulate and evaluate the performance of anticoagulant coatings in a hemodynamic environment close to the real physiological conditions, an extracorporeal circulation experimental setup serves as the core tool for mimicking the systemic circulation at the macroscopic level. This type of apparatus utilizes a precision pump control system to simulate physiological pulsatile blood flow, generating precisely controlled shear forces on the surface of coated devices. Its key advantage lies in the ability to conduct long-term tests lasting from several hours to weeks using fresh whole blood, thereby fully preserving the interactions among platelets, coagulation factors, and inflammatory cells. It effectively reflects the impact of hemodynamic parameters on the performance of anticoagulant coatings.

At the microscopic level, microfluidic chip technology enables precise manipulation of local blood flow environments through micron-scale channel structures [151,152,153]. These chips can be designed with bifurcated, curved, or constricted biomimetic channels to simulate turbulent flow effects at vascular branches or high shear stress concentrations at atherosclerotic lesions within millimeter-scale regions. They are capable of integrating real-time monitoring functions, such as platelet adhesion dynamics, or utilizing fluorescence labeling for quantitative analysis of fibrin network formation processes. More advanced models also pre-seed vascular endothelial cells within the channels to construct “vessel-on-a-chip” systems for studying the effects of coatings on endothelial barrier function.

The current technological frontier is dedicated to correlating data between macroscopic and microscopic models: obtaining system-level parameters through extracorporeal circulation setups while using microfluidic chips to analyze the initial molecular events of thrombus formation. This multi-scale validation strategy not only reveals the anticoagulation mechanisms of coatings but also establishes quantitative models to predict clinical risks, providing precise guidance for coating optimization.

4. Conclusions and Outlook

This article has systematically reviewed the main anticoagulant surface modification strategies for blood-contacting materials. While these strategies have achieved considerable success in reducing surface-induced thrombosis, individual strategies possess limitations and face distinct challenges in long-term applications. Among the current research hotspots for novel surface modifications, the three-dimensional network structure and high water content of hydrogel coatings provide an excellent foundation for inhibiting protein and non-specific cell adhesion. However, their mechanical strength, adhesion to the substrate, and swelling/degradation behavior under in vivo circulatory conditions remain key constraints for their long-term application. The “slippery” effect of liquid-infused surfaces grants them exceptional anti-adhesion properties, but the loss and replenishment mechanisms of the liquid film are critical issues that must be resolved prior to clinical translation. Endothelialized surfaces represent the ultimate goal of anticoagulant surface engineering; however, overly aggressive endothelialization may be accompanied by intimal hyperplasia, while functional immaturity of the endothelial cells could lead to their detachment under high shear stress or a switch to a pro-coagulant phenotype.

In the field of anticoagulant surface modification research, contradictory conclusions often arise in the literature regarding the same technology, primarily due to multidimensional variables such as material properties, experimental conditions, and evaluation systems. For instance, the controversy over the anticoagulant efficacy of diamond-like carbon (DLC) coatings may stem from the sensitivity of surface energy parameters—such as the sp3/sp2 carbon bond ratio, hydrogen content, and the influence of dopants (e.g., fluorine or silicon) on hydrophobicity—as well as residual stress changes caused by the rigidity of the substrate material. The debate over the activity retention of heparin immobilization methods is related to limitations in detection techniques: in vitro experiments use purified antithrombin III to evaluate activity, whereas the in vivo environment involves competitive binding proteins like vitronectin. Moreover, in dynamic blood flow, the chain segment oscillation of end-point immobilized heparin may obscure active sites, while multivalent covalent immobilization offers greater stability under shear stress but lower activity.

The divergence in the long-term stability of liquid-infused surfaces (LIS) is closely tied to the design of the substrate microstructure. Although nanopores can effectively trap lubricants, protein deposition may lead to clogging. Additionally, perfluoropolyether lubricants may be degraded by phospholipases, and vortices in the hemodynamic environment can accelerate lubricant loss. The controversy over the functional maturity of endothelialization strategies involves cellular functional heterogeneity. These contradictions highlight the necessity of a standardized evaluation system, which requires multicenter validation combining material characterization parameters, dynamic blood flow models, and functional indicators to accurately assess anticoagulant performance.

For an outlook, the core challenge in the clinical translation for different strategies is as follows:

Heparin coatings and carbon-based coatings face obstacles related to activity retention and mechanism clarification, respectively. For heparin coatings, their bioactivity tends to degrade under high shear stress, and issues of non-specific protein adsorption persist. For carbon-based coatings such as diamond-like carbon, although partially applied, their exact anticoagulation mechanism remains unclear, and the risk of particle generation from coating delamination also warrants vigilance.

The challenge in the clinical translation of hydrogel coatings lies in their mechanical stability and adhesion to the substrate. Under continuous blood flow shear stress, coatings are prone to swelling, degradation, or the formation of microcracks, leading to functional failure. In the long term, issues such as hydrolysis and oxidation of polymer chains in the physiological environment must also be addressed. The introduction of interpenetrating networks or microgel reinforcement phases is a pathway to enhance toughness, but the process stability for large-scale production remains an unresolved challenge.

The main obstacle for liquid-infused surfaces is the long-term stability of the lubricating film. Under conditions of blood flow shear or the presence of gas–liquid interfaces, the lubricant gradually depletes, leading to a significant decline in its superior anti-adhesive performance over time. Developing micro-nanostructures capable of retaining the lubricant and establishing effective in situ replenishment mechanisms are essential thresholds to overcome for clinical application. Additionally, the biocompatibility of the lubricant itself requires systematic assessment.

Nitric oxide-releasing coatings require precise control over their release kinetics. The ideal coating should mimic the vascular endothelium, releasing nitric oxide “on demand” according to physiological needs. Existing technological approaches, whether physical doping, chemical bonding, or catalytic generation, each have limitations in terms of release durability, flux control, and dynamic responsiveness to the physiological environment. Balancing loading capacity, release rate, and biocompatibility is the core design dilemma.

The key to endothelialization strategies lies in achieving functional maturity and long-term stability of endothelial cells. The implanted cells must stably adhere under high shear stress conditions and maintain their anti-thrombotic phenotype, avoiding conversion to a pro-thrombotic state or excessive proliferation leading to restenosis. Precision regulation of cellular behavior through biomaterial approaches, such as immobilizing specific peptides or growth factors, is a current research focus. However, achieving uniform and efficient endothelialization on large-scale, complex implant surfaces remains a significant challenge.

Looking ahead, the paradigm of anticoagulant surface modification is poised for transformation, with future development trends exhibiting the following characteristics: (1) A shift from “static” to “dynamically intelligent responsive” systems: The ideal surface will no longer be an inert coating but rather an “intelligent interface” capable of sensing changes in the blood environment and providing real-time feedback; (2) A progression from “single-function” to “multifunctional integration”: For instance, combining the ability of hydrogels to stably incorporate liquid phases, the anti-adhesive properties of liquid-infused surfaces, and the bio-integrative capacity of endothelialization to construct multifunctional coatings that form a synergistic system.

Author Contributions

Investigation, S.Z., Z.D. and C.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Z., Z.D. and Y.W.; writing—survey and editing, Z.D., Y.W. and C.Z.; supervision, S.Z., Y.W. and C.Z.; funding acquisition, S.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.52205208), Changzhou Type D Program for the Introduction and Cultivation of Leading Innovative Talents (Basic Research Innovation Category) (Grant No.CQ20240138), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos.52205207 and 52405435), the Shanxi Province Key Research and Development Program Project (CN) (No.202202050201018), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. B250201113).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are included in the article and the corresponding references.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jaffer, I.H.; Weitz, J.I. The blood compatibility challenge. Part 1: Blood-contacting medical devices: The scope of the problem. Acta Biomater. 2019, 94, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radke, D.; Jia, W.; Sharma, D.; Fena, K.; Wang, G.; Goldman, J.; Zhao, F. Tissue engineering at the blood-contacting surface: A review of challenges and strategies in vascular graft development. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2018, 7, 1701461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchinka, J.; Willems, C.; Telyshev, D.V.; Groth, T. Control of Blood Coagulation by Hemocompatible Material Surfaces—A Review. Bioengineering 2021, 8, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luu, C.H.; Nguyen, N.T.; Ta, H.T. Unravelling surface modification strategies for preventing medical device-induced thrombosis. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2024, 13, 2301039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredenburgh, J.C.; Gross, P.L.; Weitz, J.I. Emerging anticoagulant strategies. Blood 2017, 129, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashcraft, M.; Douglass, M.; Chen, Y.; Handa, H. Combination strategies for antithrombotic biomaterials: An emerging trend towards hemocompatibility. Biomater. Sci. 2021, 9, 2413–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, J.; Huang, N. The structure, formation, and effect of plasma protein layer on the blood contact materials: A review. Biosurf. Biotribol. 2022, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]