1. Introduction

Modern indirect restorations, particularly those using CAD/CAM technology, have benefited greatly from advancements in digital technology. These restorations are made by milling composite or ceramic blocks [

1]. A significant disadvantage of dental ceramics is their inherent brittleness, which makes them prone to crack initiation and catastrophic fracture under functional loading, potentially compromising their long-term clinical performance. Their high hardness may also contribute to wear of opposing natural teeth [

2,

3]. In contrast, resin composite materials offer several practical advantages, including a lower elastic modulus that provides greater flexibility and reduced brittleness, thereby improving their ability to tolerate functional stresses [

4]. CAD/CAM resin composites also exhibit lower hardness, allowing easier machining without rapid bur wear and reducing the risk of catastrophic failure or chipping during milling [

5,

6], while minimizing wear of opposing dentition [

7,

8]. Additionally, their clinical use is more cost-efficient due to simpler production processes, the absence of firing procedures for staining and crystallization, shorter milling times, reduced bur wear—which prolongs bur lifespan—and easier intraoral repair in the event of failure. These materials further offer appropriate retention with resin cements when suitable surface treatments are applied [

8].

Microstructure-based classification of CAD/CAM resin composite materials generally divides them into PICN composites and materials with fillers distributed within the resin matrix. According to Della Bona et al. (2014), PICN materials include porous ceramic networks impregnated with resin polymers, which are true hybrid materials [

9]. On the other hand, resin matrix composites with dispersed filler materials contain highly crosslinked resin matrices containing a large volume fraction of filler particles. Apart from the conventional filler-resin mixing composite materials, these composites build on improvements in resin monomer, initiators, curing method, and filler loading [

8]. There are multiple types of resin blocks, and one notable difference is in the filler loading (wt%); for example, CeraSmart 270 (GC, Tokyo, Japan), which is composed of 71 wt% silica and barium glass nanoparticles, whereas Grandio bloc (VOCO, Germany) contains a higher filler content (86 wt%).

Several studies have been conducted to determine the efficiency of resin composite restorations made with the indirect CAD/CAM technique [

10,

11,

12]. The primary cause of failure in all trials was fracture, underscoring the importance of fracture toughness in achieving suitable clinical results. Several attempts have been made to improve the mechanical properties of large composite fillings and the remaining dental hard tissues. Most manufacturing industries have utilized enhanced CAD/CAM composite blocks in recent years, and the filler technology employed has been enhanced to achieve better mechanical properties [

4]. Some of the recent advancements concern technology related to the use of resin composites, among which are short fiber-reinforced composites (SFRCs) that involve the inclusion of short glass fibers in the filler system to influence crack propagation effectively [

13]. Various types of fibers are used in clinical practice; however, the most common are S-glass and E-glass fibers, as they can be silanized effectively to the resin matrix [

14]. The EverX Flow (GC Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) consists of short E-glass fiber fillers incorporated into a resin matrix of cross-linked Bis-MEPP, TEGDMA, and UDMA monomers with linear polymer. This results in the formation of a semi-interpenetrating polymer network that improves both fracture toughness and bonding [

15]. The literature shows that the reinforcing capacity of SFRCs improves as the material’s volume increases. Numerous clinical and laboratory studies have even broadened its application beyond a bulk base for dentin restoration, using it for the reconstruction of entire cavities without surface coverage [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

There is a considerable difference between the mechanical properties of the experimental SFRC block and those achieved by direct SFRC. In clinical practice, in some clinical situations, the light tip cannot be placed in close contact with the surface of the restoration. Other factors include the type of curing unit and the method of curing, both of which affect the degree of conversion during polymerization. Restoring deep cavities with a high C-factor remains a significant challenge in clinical practice [

22,

23]. On the other hand, the fabrication of the experimental SFRC block revealed a denser and more homogeneous structure with fewer imperfections, such as voids and air bubbles. This quality cannot be achieved with the direct technique for large restorations in high stress-bearing areas.

Previous studies have demonstrated the promising mechanical properties of SFRCs with respect to direct restoration. However, there is a lack of data on two mechanical characteristics of SFRC designed specifically for indirect CAD/CAM restorations. This study aims to fabricate a novel experimental short fiber-reinforced composite CAD/CAM block and evaluate its fracture toughness and surface roughness properties as an indirect restoration in comparison with different conventional resin-based CAD/CAM blocks.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fabrication of a Custom Mold for a Novel Experimental SFRC CAD/CAM Block Preparation

To fabricate each experimental block, a custom glass mold was designed to replicate the dimensions of a standard C14 block (18 mm in length, 14 mm in width, and 12 mm in height). The base of the mold consisted of a transparent square glass plate with dimensions of (60 mm× 60 mm). On this basis, two parallel plastic holders with exact dimensions were positioned. These holders were custom-designed with dish-like recesses to securely accommodate the placement of four separate vertical glass walls, each with dimensions of 25 mm × 20 mm × 3 mm (length, width, and thickness, respectively), which serve as the boundaries of the mold cavity. Intentionally, a small clearance space was left between the external securing holder and the vertical glass pieces to allow for smooth removal during the demolding process. Each of the four vertical glass pieces was placed into the recesses of the plastic holder and secured in position using wedges to prevent any displacement during composite injection and curing. The mold was designed so that during the injection, the composite came into contact only with the internal glass surfaces, ensuring a uniform and smooth finish. The entire setup, consisting of the bottom glass plate and the two plastic holders, was stabilized by applying adhesive tape on both sides to ensure structural integrity throughout the process.

2.2. Preparation of a Novel Experimental SFRC CAD/CAM Block

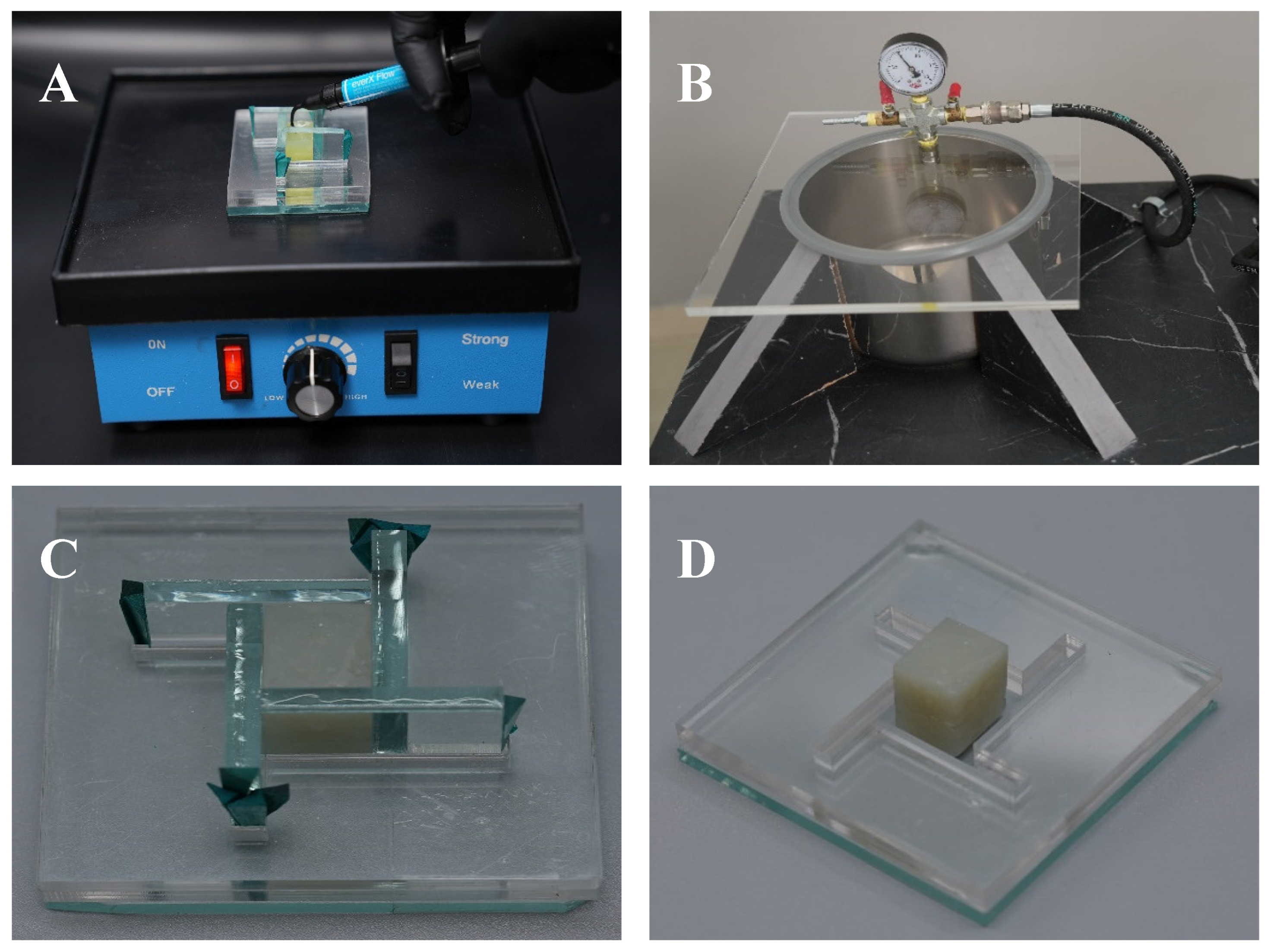

The EverX Flow composite (bulk shade) from GC Corporation, Tokyo, Japan, was utilized in this study. Before injection, the custom-made mold was preheated in an oven at 70 °C for 5 min to minimize thermal stress and improve flowability. Simultaneously, the composite syringes were placed in a composite warmer set to 70 °C to optimize their viscosity for injection. Immediately after removal from the oven, the mold was positioned on a vibrating platform to facilitate uniform flow and minimize air entrapment (

Figure 1A). The warmed composite was then slowly injected into the mold to a height of 5.5 mm, as marked externally on the mold surface. Then, the partially filled mold was placed back into the oven at 70 °C for 15 min to eliminate voids within the material during the filling process. Afterward, the mold was transferred to a vacuum chamber at a pressure of −80 kPa for 5 min, allowing for effective degassing. Following this, the pressure was gradually released to prevent material disruption and bubble formation (

Figure 1B). After pressure was applied, the composite was light cured using a LED light cure device at 1200 Mw/cm

2 light intensity (Eliper DeepCure-S, 3M ESPE, USA), and the identical sequences of steps were repeated until the mold was filled. For the final layer, a Mylar strip was carefully placed over the surface in contact with the composite to prevent the oxygen inhibition layer and ensure a smooth finish. The entire mold was then placed in a Solidilite V light-curing unit (Shofu Dental GmbH, Ratingen, Germany) for 5 min; this device operates within a broad wavelength spectrum ranging from 400 to 550 nm, which is ideal to facilitate deep and thorough polymerization throughout the block. Upon curing completion, the wedges securing the mold walls were gently removed. Subsequently, each glass piece was detached one by one, allowing for easy demolding without adherence to the block, resulting in a clean and well-formed block (

Figure 1C,D).

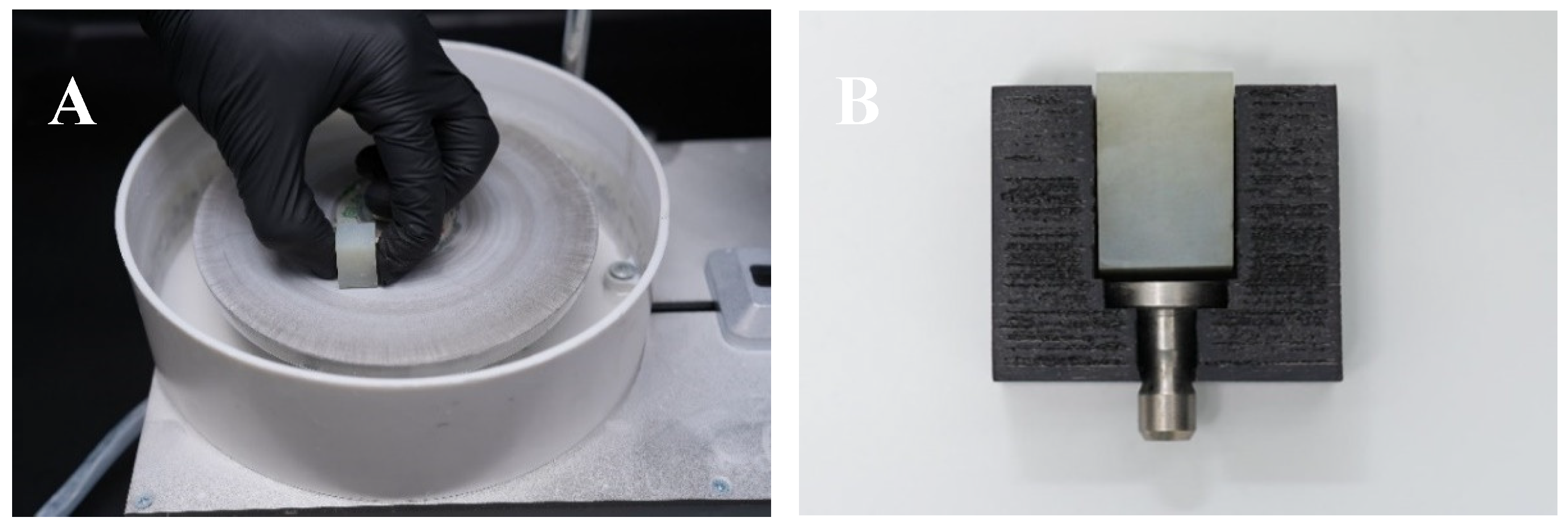

2.3. Post-Curing Finishing and Spru Attachment

After the polymerization of the block was finished, it was smoothed using a high-precision cutting machine to remove any surface irregularities and ensure the dimensional accuracy of a standard-size C14 block. Then, a sprue attachment was securely bonded to the block. To ensure accurate alignment of the block with the spru attachment, the block was placed in a custom-fabricated plastic holder designed based on a prefabricated commercial C14-size CAD/CAM block. This allowed for the precise identification of the spru attachment’s location, enabling exact central positioning. Adhesive was then applied to securely bond the spru attachment to the block (

Figure 2A,B).

2.4. Specimens Preparation

Various sizes and geometries (bar and rectangular shapes) of the samples for different tests were designed using CAD software (Chitubox; V1.9.5). The generated STL file was sent to the CAD machine (CORiTEC 350 i PRO, imes-icore, GmbH, Eiterfeld, Germany, Serial No. 2021-S3-418). in a wet grinding process. All milling instruments and tools were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All specimens were cleaned ultrasonically using distilled water for 1 min and dried. Finally, all samples were inspected for defects under a stereo light microscope and measured using a digital caliper to ensure comparable dimensions and thickness for each test. The chemical structure of the Experimental SFRC group was analyzed using a Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) spectrometer (Thermo Electron Nicolet 5700 IR 1800). The microstructure of specimens from each group was examined using Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FESEM; Inspect F50, FEI). Prior to imaging, the specimen surfaces were inspected for defects or irregularities and subsequently polished with diamond paste to achieve a smooth and reflective finish.

2.5. Fracture Toughness Test

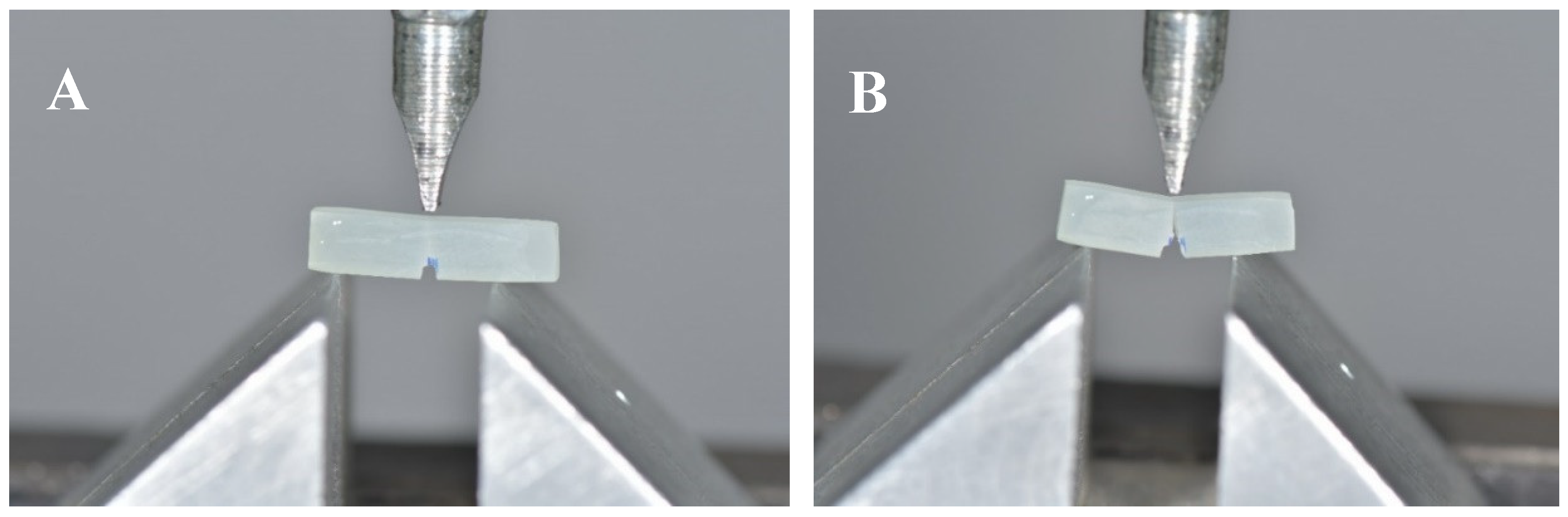

The fracture toughness of the milled specimens was measured according to the ISO 6872:2023 standard using the same 3-point bending fixture [

24]. Fifteen beam-shaped specimens from each group (Grandio blocs, Cerasmart 270, Experimental SFRC) were selected with dimensions of 16 mm length × 4.2 mm width × 2.1 mm thickness (

Figure 3). A notch was created in each specimen using a single-edged V-notch beam (SEVNB) methodology, following the method described in ISO 23146:2016 [

25]. The specimens were firmly fixed in metal holders with the 3 mm surface oriented upward. A 0.6 mm diamond disk attached to a slow-speed handpiece on a positioning device was then used to create a sharp central notch in each beam. The notch had a depth within the range of 0.8 to 1.2 mm. A razor blade was placed at the notch base to generate a microcrack extending to a depth of approximately 0.1 to 0.2 mm.

Then, each specimen was placed on a fixture with a support span of 12 mm and a displacement rate of 1 mm/min (

Figure 4). The (KIc) was measured in (MPa·√m) using the following formula:

F is the maximum load to fracture (N); L is the support span distance (mm); B is the width of the specimen (mm); W is the height of the specimen (mm); and Y is a geometrical function calculated by the following equation where

a is the crack length (mm) and w is the height (mm).

After the fracture testing, the surfaces of all specimens were sputter-coated with a platinum–palladium alloy for examination of the fracture surface using a SME (Field emission scanning electron microscopy, Inspect F50, FEI company, Netherlands) at various magnifications.

2.6. Surface Roughness Test

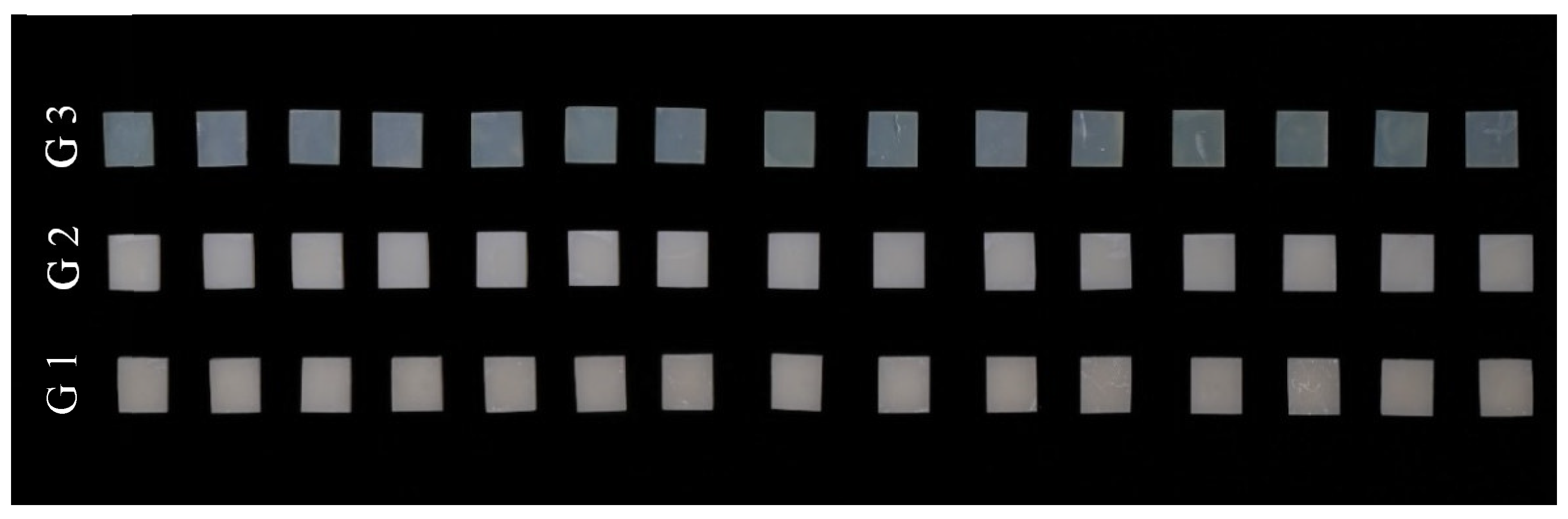

Fifteen square-shaped specimens from each group with dimensions of 10 mm length × 10 mm width × 2 mm thickness were selected (Grandio blocs, Cerasmart 270, Experimental SFRC) (

Figure 5), and they were polished using two-step DIACOMP PLUS TWIST diamond-impregnated polishing wheels (EVE ERNST VETTER). All specimens were polished with water irrigation at 8000 rpm for 20 s using pre-polishing and high-shine polishing wheels, then cleaned in an ultrasonic bath with distilled water to remove any surface debris. After the polishing procedure, the specimens from each group were prepared for SEM study to assess the finishing of each material [

26]. A light profilometer (TIME3200, Beijing Time High Technology, Ltd., Beijing, China) was used to evaluate the roughness of each specimen by measuring the average surface roughness (Ra value) under standardized conditions using Data View TIME3202 software. During the procedure, the measuring tip was positioned at a right angle to the polished surface. Three measurements were conducted in different areas, using a tracing length of 0.5 mm, a scanning speed of 0.5 mm/s, and a resolution of 0.01 μm. The average roughness was then calculated [

27].

2.7. Study Design and Testing Materials

Table 1 presents a list of the three resin-based composite blocks included in this study. This study divided the specimens into three groups—Group 1: Grandio blocs; Group 2: Cerasmart 270; Group 3: Experimental SFRC—with 30 specimens for each; then, each group was subdivided into sub-groups for different tests. The sample size was 15 for each group.

The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 27. Descriptive statistics were first calculated to summarize the main characteristics of the data. A one-way ANOVA was then used to assess differences among the study groups. When significant effects were detected, Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise comparisons were conducted to determine which groups differed from one another.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization Results

The provided FTIR spectrum exhibits several distinct peaks indicative of different functional groups and molecular vibrations, providing valuable insights into the composition and structure of the experimental SFRC CAD/CAM block after polymerization (

Figure 6).

Silica–SiO2 Peak (447–470 cm−1): This range corresponds to the stretching vibrations of Si–O–Si bonds in silica, an inorganic filler commonly used to enhance mechanical strength. The presence of this peak in both pre- and post-polymerization spectra indicates that the inorganic filler remains stable during the polymerization process.

Si–O Bonds (617–621 cm−1): These peaks represent the stretching of Si–O bonds, which are significant for forming the filler–matrix network. Slight shifts suggest changes in the chemical environment after polymerization.

C–O–C Stretching (1174 cm−1): This peak appears only after polymerization and indicates the formation of new ether bonds, likely resulting from the reaction of monomers containing epoxy or methacrylate groups.

H–O–H Bending (1490 cm−1): This peak represents the bending vibrations of water molecules or hydroxyl groups, indicating the presence of moisture or OH group incorporation into the polymer network.

C=C—Aromatic or Unsaturated Double Bonds (1564–1618 cm−1): These peaks are associated with unreacted double bonds in methacrylate monomers. A decrease or shift post-polymerization indicates the consumption of C=C bonds during curing.

C=C Stretching (1656–1627 cm−1): A characteristic feature of unpolymerized monomers. The reduction in this signal post-polymerization confirms the formation of a polymer network.

C=O Stretching (1722 cm−1): This carbonyl stretch is typical for methacrylate groups. Disappearance or shift post-polymerization suggests a reaction of carbonyl-containing monomers during curing.

C=O Bending or Specific Mode (2195 cm−1): This is an uncommon band and may correspond to unique vibrational modes or residual monomers with conjugated systems.

C–H Stretching (2796–2956 cm−1): These peaks correspond to aliphatic and aromatic C–H stretching. Variations may reflect changes in bond distribution or monomer types after curing.

O–H Stretching (3138–3531 cm−1): This broad region reflects the presence of hydroxyl (OH) groups, which may be due to water, alcohols, or polymer backbones. An increase and shift in this region post-polymerization suggest enhanced hydrogen bonding or exposure of OH groups due to the formation of an open polymer network.

The SEM (scanning electron microscope) images revealed the dual-phase composite material consisting of a polymeric matrix and reinforcing fibers. The distribution of the reinforcing fibers within the matrix appeared to be homogeneous, indicating good dispersion during the preparation process. These fibers were oriented and distributed randomly in multiple directions. The SEM image revealed fibers well embedded within the resin matrix, suggesting intimate morphological contact at the fiber-matrix interface, which was crucial for effective stress transfer and overall durability (

Figure 7A,B). These fibers exhibited diameters of approximately 7 µm and lengths exceeding 300 µm, consistent with the specifications of short or chopped fiber reinforcements commonly used in dental composites. Furthermore, there were indications of the presence of nanoparticles, likely nano-silica or alumina, with estimated grain sizes below 100 nm.

The SEM analysis demonstrates distinct microstructural features of the other two CAD/CAM blocks. The Grandio Bloc exhibits a densely packed nanohybrid structure with irregular, closely clustered inorganic fillers embedded within the resin phase, resulting in a compact, granular morphology with minimal inter-particle spacing (

Figure 7C). In contrast, Cerasmart 270 shows a more homogeneous microstructure with uniformly dispersed nano-sized spherical fillers within the resin matrix, producing a smoother and more uniform surface (

Figure 7D).

3.2. Fracture Toughness Result

Table 2 shows the test results for the fracture toughness characteristics of the Experimental and commercially available resin-based block materials. A higher fracture toughness was observed in the Experimental SFRC when compared to the Grandio blocs and Cerasmart 270 groups. One-way ANOVA and Bonferroni tests (

p ≤ 0.05) showed a significant difference among groups, as shown in the table. The Experimental SFRC group showed the highest mean value (2.758) compared to Grandio blocs (2.390) and Cerasmart 270 (2.572), and the pairwise comparison test results showed a statistically significant mean difference among all three groups.

The SEM images of the fractured surfaces of different groups reveal differences in resin matrix and inorganic filler content within each group after fracturing. Differences in the mechanical properties of each group were influenced by the microstructure shown in the fractured surface topography. In the Grandio blocs and Cerasmart 270 groups, a smoother fracture surface was observed (

Figure 8C,D), while the fracture surface in the Experimental SFRC group showed that, in some areas, fibers were completely pulled out from the matrix during the failure process. In contrast, other fibers appeared broken at their ends, indicating that these fibers fractured in situ due to strong bonding with the matrix that carried the load (

Figure 8A,B).

3.3. Surface Roughness Result

The descriptive analysis, including mean values and standard deviations, as well as the 95% confidence interval values of the average surface roughness (Ra) data of the experimental groups, is shown in

Table 3. The Cerasmart groups had a lower Ra value (0.135) compared to that of the Grandio blocs (0.168) and the Experimental SFRC (0.182) groups. One-way ANOVA was used to analyze the data, and it revealed a statistically significant difference between groups (

p-value = 0.000, i.e., less than 0.05). When comparing the surface roughness of each group, a statistically significant difference was observed only between all three observed groups.

The SEM revealed that the fibers were chopped and acted as filler particles, which were then embedded within the resin matrix. They are not easily observed on the surface of the samples via SEM, since protruding these fibers leads to a rough surface that affects the polishability of these materials (

Figure 9E,F).

4. Discussion

Fracture remains the most frequently reported failure mode in resin composite restorations, regardless of whether they are fabricated using direct or CAD/CAM techniques [

11,

28]. This underscores the central role of fracture toughness in ensuring the clinical longevity of polymer-based restorations. Resin-based composites (RBCs) often exhibit insufficient toughness under high occlusal loads, which limits their reliability in stress-bearing applications such as posterior overlay or extensive MOD restorations. The improved mechanical properties of resin-based composites are generally attributed to modified microstructural features, including the polymer matrix, type and loading of fillers, and the quality of the filler-matrix interface [

29].

This study aimed to fabricate and characterize a novel Experimental SFRC block in terms of mechanical properties, and to compare them with different commercial CAD/CAM resin composite blocks (Grandio blocs, Cerasmart 270). The Experimental SFRC block consists of the same quantity of discontinuous short e-glass fibers with a diameter of 6 μm and a length between 200 and 300 μm that had been used for the fabrication of commercial flowable SFRC (ever X flow) from GC Corporation, Tokyo, Japan. It is made of an inorganic silanated particle filler (45 wt%), a resin matrix (30 wt%), and randomly oriented glass microfibers (25 wt%) [

30]. Aspect ratio, critical fiber length, fiber loading, and fiber orientation are the main factors that could improve or impair the mechanical properties of SFRC [

31]. Aspect ratio refers to the fiber length-to-fiber diameter ratio. It impacts the reinforcing capacity of SFRC. The microfibers used in this study had an aspect ratio of more than 30, which is reported to be the minimum optimal aspect ratio for effective reinforcement [

32]. This material is reinforced and transformed into a milled block suitable for CAD/CAM by compressing and heat-curing under a tightly controlled environment, thereby increasing the degree of conversion of the material. This method yields a highly homogeneous and dense internal structure, significantly reducing the presence of unreacted monomers. The chemical structure of the Experimental SFRC group was analyzed using the Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) spectrometer. The FTIR findings provided valuable insight into the chemical integrity, reactivity, and potential performance of the Experimental SFRC block (

Figure 6). According to the results, the presence of intense C=C and C=O peaks before polymerization, followed by their reduction or spectral shift thereafter, confirms that successful chemical reactions and polymer network formation occurred. The prominent O–H bands indicate a significant number of polar groups, which may enhance moisture compatibility and adhesion. SiO

2 and Si–O peaks remain stable, indicating inorganic filler integrity, which supports mechanical durability.

The fracture toughness of a material is a measure of how well that material resists the propagation of a crack and the flow of energy under load. The single-edged V-notch beam (SEVNB) methodology was used to evaluate the fracture toughness, as it has been widely recognized and utilized in previous studies [

33,

34]. In this study, crack propagation was induced by introducing a small (0.1 to 0.2 mm) pre-crack, as described in ISO 23146:2016. Based on the results of this study, the Experimental SFRC block exhibits higher fracture toughness than Cerasmart 270 and Grandio blocs. The beam specimens of Cerasmart 270 and Grandio blocs fractured catastrophically at comparatively lower loads than the beam specimens of experimental short fiber-reinforced composites, as the specimens in this group prevented the complete separation of the fractured beam (

Figure 4B). This could be attributed to the higher filler loading in Grandio blocs (86 wt%) and Cerasmart 270 (71 wt%), which makes these blocks more brittle than the Experimental SFRC block, which confirms that the microstructure composition of CAD/CAM blocks affects their mechanical properties because the impact of filler loading on the brittleness of resin-based CAD/CAM blocks is well documented [

27,

35]. Incorporating fibers into a resin-based restoration helps absorb applied loads, thereby reducing stress on the resin matrix. This not only improves the materials’ longevity but also lowers the risk of cracking and restoration failure.

The SEM showed that the number of pulled-out versus fractured fibers appears comparable, suggesting a balance between fiber–matrix adhesion and mechanical failure behavior (

Figure 8A,B). The observation of broken fibers implies strong interfacial adhesion between the matrix and the reinforcing fibers, which is typically associated with enhanced mechanical performance (subject to confirmation via mechanical testing). This is due to the random arrangement of these fibers, which prevented the complete separation of all fibers, so they could not be fully separated during the test. This arrangement helped to prevent catastrophic failure. In the Experimental SFRC block, optimal aspect ratio (OAR) technology was employed. This technique allows for the random distribution of shorter, narrower fibers within the resin matrix, thereby increasing the fiber load and enhancing its toughness by resisting crack propagation. There is interfacial adhesion between the fiber and resin matrix, enhanced by a saline coupling agent using full-coverage silane coating (FSC) technology, which improves the bond between the fiber and matrix by creating a chemical bridge between them. This could indicate the better performance of SFRC in high-stress-bearing application areas.

The Cerasmart 270 exhibited the lowest Ra among the groups, and the Experimental SFRC showed slightly higher Ra than the Grandio bloc. The Ra for the polished specimens of all groups was below the clinically acceptable maximum of 0.2 μm. Roughness above 0.2 μm has been associated with increased plaque and oral biofilm formation [

27]. The difference in surface roughness parameters among various groups is attributed to variations in their filler size, geometry, and composition. The lowest values of Ra were observed in the Cerasmart 270 group, which is likely due to the microstructure, filler particle size, and shape, resulting in a smoother surface that may explain the significantly lower roughness value (

Figure 9A,B). The surprising result was that the Experimental SFRC showed higher surface roughness before polishing; however, it was drastically decreased after polishing, and the final Ra value fell within the clinically acceptable maximum range, indicating that it could be well polished for clinical use after milling (

Figure 9E,F). A possible explanation for this is the strong interfacial adhesion between the fiber and the polymer matrix, as well as the filler’s use of FSC technology. Similar findings have been reported in the literature [

36,

37,

38] when comparing flowable SFRC to other conventional and bulk-fill PFCs; these studies revealed flowable SFRC’s good wear resistance and surface characteristics. They mentioned that the microfibers of the flowable SFRC did not protrude; instead, they were polished in the resin matrix, resulting in a uniformly smooth surface. Further studies by Lassila et al. (2020) and Uctasli et al. (2023) demonstrated that flowable SFRC had surface gloss values and color stability comparable to those of other tested conventional PFCs [

30,

39].

A study by Attik et al. (2022) found that EverX Flow, a short-fiber reinforced composite (SFRC), had a less negative impact on primary gingival fibroblast (hGF) viability, especially on day 3, and this pattern continued through day 5, with cells showing increased metabolic activity when exposed to SFRC [

40]. This result highlights the favorable biological response of SFRCs. It supports the safe use of SFRCs in restorative dental procedures when exposed to oral environments, which may contribute to reduced cytotoxicity and improved compatibility. The findings of this in vitro study indicate that the Experimental SFRC CAD/CAM block exhibits improved mechanical performance, suggesting its suitability for posterior application. Moreover, in terms of fracture behavior, SFRCs display favorable performance by halting or deflecting crack propagation. The energy-absorbing and stress-dissipating fibers redirect crack progression toward the periphery, resulting in more favorable, non-catastrophic fracture patterns, especially in high-stress-bearing areas [

41]. However, complete reliance on the results of an in vitro study is not advisable, and it is recommended to perform in vivo studies to confirm the in vitro results and produce data with a higher level of evidence to support clinical application. The limitation of this study is that the Experimental SFRC block was fabricated using a custom glass mold and a laboratory curing unit, which does not fully replicate the industrial high-pressure, high-temperature polymerization process used for commercial resin-based CAD/CAM blocks. Generally, the manufacturer does not disclose the exact fabrication process of the commercial resin-based CAD/CAM blocks since it is protected as proprietary. This lack of transparency limits our ability to fully interpret variations in material properties, making it difficult to replicate the exact industrial fabrication conditions in a laboratory. This may influence the polymer cross-linking and final mechanical and physical properties of this material.