Abstract

This study aims to evaluate the corrosion inhibition performance of different types of inhibitors for steel reinforcement in cement paste under accelerated carbonation conditions. Electrochemical methods, including electrochemical impedance spectroscopy EIS, linear polarization resistance LPR, and open-circuit potential OCP measurements, were utilized on specimens with various inhibitor formulations during exposure to a high-CO2 environment. The results indicate that composite inhibitors provide the greatest protection, significantly outperforming single-component anodic or cathodic inhibitors. Among anodic inhibitors, sodium molybdate showed more effective corrosion inhibition than sodium chromate, and among cathodic inhibitors, BTA was more effective than DMEA, as evidenced by higher polarization resistance and more stable passivation. After 120 days of carbonation, the specimen with the optimal composite inhibitor remained passive with a low corrosion rate and a relatively noble steel potential, whereas the uninhibited specimen exhibited active corrosion.

1. Introduction

The causes of steel reinforcement corrosion are multifaceted, but numerous instances of reinforced concrete structure failures indicate that the primary sources of corrosion are chloride salts and carbonation. Moreover, a significant number of concrete structures are subjected to a corrosive environment under the dual influence of CO2 and chloride ions during service [1,2,3]. Generally, the surface of steel reinforcement within concrete is in a stable passivated state due to the presence of highly alkaline pore solutions in the concrete. However, when external CO2 and chloride ions penetrate into the concrete, the pH of the pore solution decreases, and the chloride ion content increases, leading to the breakdown of the passivation film and the initiation of corrosion. Therefore, the passivation film is the main barrier preventing steel reinforcement from corroding [4]. Currently, there are numerous types of corrosion inhibitors for steel reinforcement available on the market, each with varying corrosion inhibition effects and mechanisms of action. Since carbonation is a critical factor contributing to steel reinforcement corrosion, studying the corrosion inhibition performance of different types of inhibitors under carbonation in concrete is of great significance for exploring their mechanisms and enhancing the corrosion resistance of steel reinforcement [5]. However, relatively few studies have systematically compared different types of inhibitors under carbonation-only conditions. In this work, we systematically evaluate representative anodic, cathodic, and composite inhibitors in carbonated cementitious environments to better understand their corrosion Inhibition performance and to examine their corrosion inhibition effectiveness and mechanisms.

In recent years, there has been a substantial body of literature both domestically and internationally on the study of incorporating corrosion inhibitors into concrete to protect the passivation film on steel reinforcement. The purpose of these studies is to improve the passivating environment on the surface of the steel, preventing the destruction of the passivation film in environments with high chloride ion content or carbonation, thereby inhibiting steel corrosion. Early studies have shown that molybdate anions can competitively adsorb on steel surfaces and interfere with chloride ion adsorption, following a Freundlich-type isotherm; a minimum molybdate concentration is required relative to the chloride content for effective inhibition. Lin [6] investigated the effects of sodium molybdate on the electrochemical corrosion behavior and the performance of the surface passivation film of steel in simulated concrete solutions, discovering that sodium molybdate significantly inhibits steel corrosion. The enhanced density and stability of the passivation film on the steel surface may be related to the direct involvement of sodium molybdate in the passivation process. Zhou [7] used techniques such as XPS to explore the mechanism of sodium molybdate on the surface of rust layers. They found that sodium molybdate facilitates the transformation of active rust (γ-FeOOH) into stable rust and forms a dense protective film composed of stable iron oxides and FeMoO4 on the rust layer surface. However, due to the high cost of molybdates, many studies [8,9] have focused on combining them with organic compounds, achieving positive results. Building on recent advances, several studies have re-examined molybdate-based inhibitors using modern surface and electrochemical characterization. For example, Wu et al. [10] and Shi et al. [11] reported that sodium molybdate can markedly improve corrosion resistance of steel in alkaline/cementitious environments by participating in the formation of Mo-containing passive films, leading to higher charge-transfer resistance and delayed depassivation. More importantly, recent work has emphasized the synergistic effect of molybdate with organic cathodic components. Shahryari, Z. et al. [1] demonstrated that molybdate-containing composite systems in NaCl media provide significantly larger impedance and stronger pitting resistance than single inhibitors, because molybdate promotes a stable anodic passive layer while organic components enhance cathodic suppression. Similar synergistic enhancement for molybdate-based mixed inhibitors has also been confirmed in chloride solutions, where composite formulations outperform single-component systems in both initiation and propagation stages of localized corrosion [12]. Mechanistically, recent reviews and experimental evidence indicate that molybdate anions can adsorb on active sites of the steel surface and incorporate into the oxide matrix to form a dense Fe–Mo–O protective layer, thereby stabilizing passivity and suppressing pit nucleation under aggressive environments [13]. Corrosion inhibitors for reinforced cementitious materials generally fall into anodic, cathodic, and composite categories, each with distinct inhibition mechanisms and performance characteristics. Anodic inhibitors such as sodium molybdate can promote the formation of stable passive films but may be sensitive to dosage and environmental conditions [14]. Cathodic inhibitors (e.g., benzotriazole and amino alcohols) act primarily by suppressing the cathodic reaction, although their long-term stability in alkaline-to-carbonated systems remains under discussion. Composite formulations have attracted attention because they integrate multiple inhibition pathways, yet their behavior under carbonation-driven depassivation has not been systematically evaluated. Most existing studies focus on chloride-induced corrosion, whereas comparatively fewer works investigate how different categories of inhibitors perform under carbonation-only conditions, where the deterioration mechanism and pore solution chemistry differ significantly. To provide a more comprehensive understanding, this paper focuses on studying the corrosion inhibition effects and mechanisms of various types of corrosion inhibitors on steel in cement paste and reinforced concrete under carbonation conditions. Techniques such as electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), linear polarization resistance (LPR), and open-circuit potential (OCP) methods were used to assess the performance of the inhibitors.

2. Experimental Scheme

2.1. Raw Materials and Specimen Preparation

HPB235 plain round steel bars with a diameter of 8 mm were used in the experiment. The chemical composition of the HPB235 plain round steel bars used in this study complies with the requirements of GB/T 1499.2 [15] for hot-rolled steel reinforcement. The nominal chemical composition range of HPB235 is listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of HPB235 steel barns.

To prepare the steel bars for electrochemical testing, all specimens were subjected to a standardized cleaning and surface conditioning procedure. The bars were first soaked in a 10% ammonium citrate solution for 3–5 days to remove the surface oxide scale. After soaking, the steel bars were thoroughly rinsed with water, wiped dry with a clean towel, and placed in an oven at approximately 100 °C for 10 min. Subsequently, the steel surfaces were polished using progressively finer grades of sandpaper until a bright metallic finish was achieved. The polished surfaces were degreased with acetone, and after confirming that no visible rust remained, the bars were sealed in plastic wrap for storage until specimen casting.

The steel bars were soaked in a 10% ammonium citrate solution for 3–5 days to remove surface oxide scale. After soaking, the bars were thoroughly rinsed with water, wiped dry with a towel, and then placed in an oven at approximately 100 °C for 10 min. The steel surfaces were then polished using progressively finer sandpaper (240, 400, 800, and 1200 grit) until a bright finish was achieved. The surfaces were degreased with acetone, and after confirming that no rust remained, the bars were sealed in plastic wrap for storage.

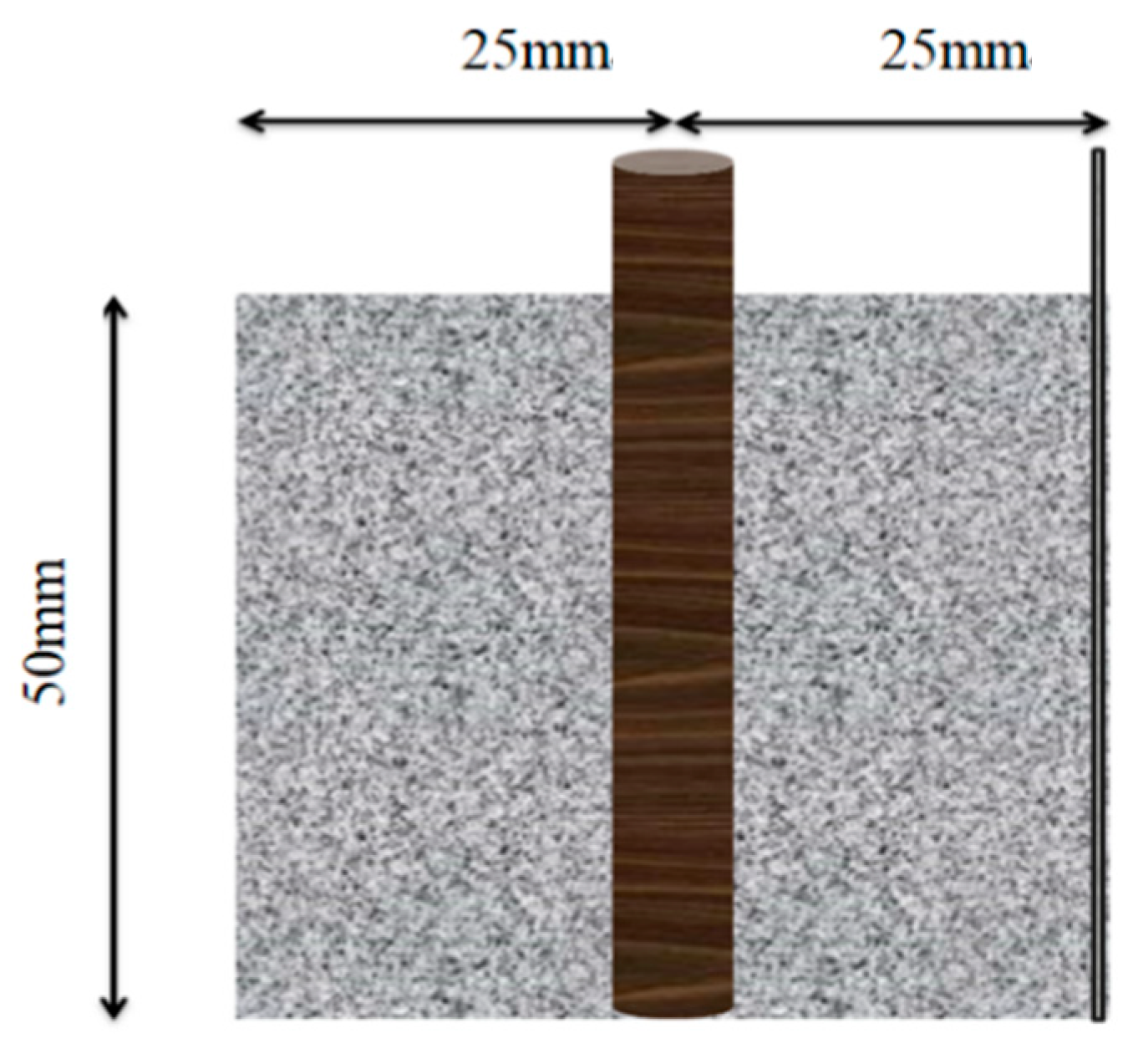

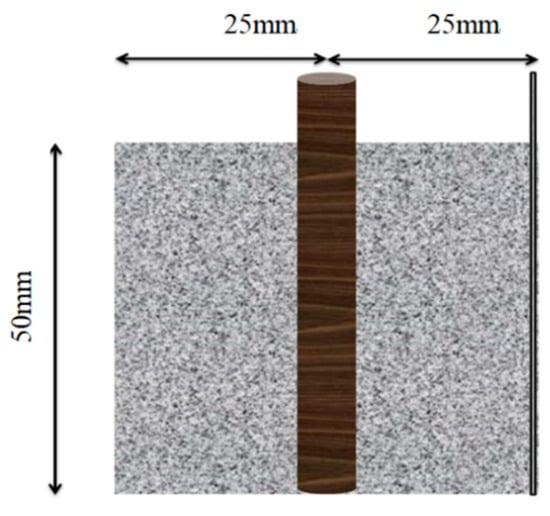

The cement paste specimens were prepared with dimensions of 50 mm × 50 mm × 50 mm, as shown in Figure 1. The specific mix proportions for the cement paste specimens are detailed in Table 2. During the preparation, a φ8 mm × 60 mm steel bar was embedded into the fresh cement paste, with 10 mm of the top end exposed to serve as the anode in the corrosion system. Additionally, a stainless steel mesh with a mesh size of 100 mesh aperture ≈ 150 μm was inserted on one side to act as the cathode in the corrosion system. A 304 stainless steel mesh was used in the experimental setup. Its nominal chemical composition (wt.%) is: C ≤ 0.08, Si ≤ 1.00, Mn ≤ 2.00, P ≤ 0.045, S ≤ 0.030, Cr 18.0–20.0, and Ni 8.0–11.0.

Figure 1.

Schematic Diagram of Cement Paste–Steel Reinforcement Specimen.

Table 2.

Mix Proportions of Cement Paste Specimens.

For each inhibitor formulation, three identical specimens were cast to ensure repeatability. All inhibitors were added by dissolving the calculated amount into the mixing water to ensure uniform distribution in the paste.

This note clarifies the specific corrosion inhibitors used in the different groups of cement paste specimens.

2.2. Carbonation Testing Method

All specimens were exposed to accelerated carbonation in a chamber with a CO2 concentration of (20 ± 1)%, relative humidity of 70%, and a temperature of (25 ± 2) °C. Starting from the day the specimens are placed in the carbonation chamber, the carbonation depth is tested every 7 days. The specimen is cut transversely, and the surface powder is blown off with a blower. Phenolphthalein reagent is then sprayed onto the cross-section, and after allowing the color to develop, the carbonation depth is measured using a vernier caliper.

The specimens were exposed to accelerated carbonation in a programmable carbonation chamber. The chamber maintained a controlled CO2 concentration of (20 ± 1)%, a relative humidity of (70 ± 5)%, and a temperature of (25 ± 2) °C throughout the exposure period. Internal air circulation ensured uniform CO2 distribution, while real-time sensors monitored CO2, temperature, and humidity to maintain stable exposure conditions. These controlled environmental parameters ensured a reproducible carbonation-induced depassivation process for all specimens.

It was found that the cement paste specimens reached full carbonation in approximately 21 days, whereas the concrete specimens required about 49 days. Therefore, we set the carbonation exposure period to 28 days for the cement paste and 56 days for the concrete specimens to ensure complete carbonation of each.

2.3. Electrochemical Testing

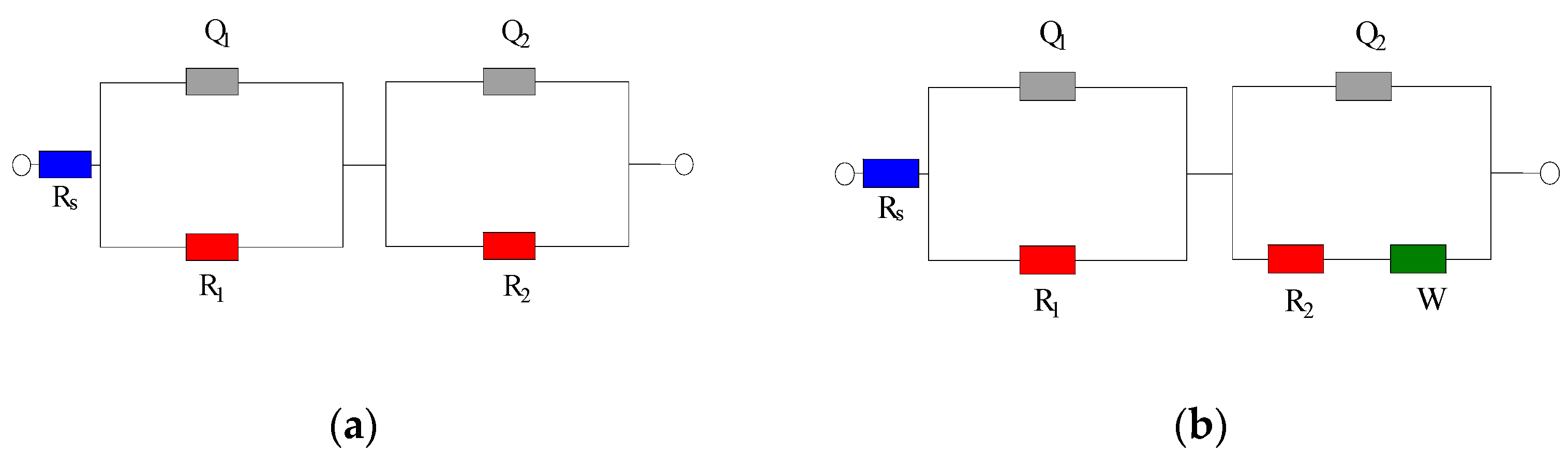

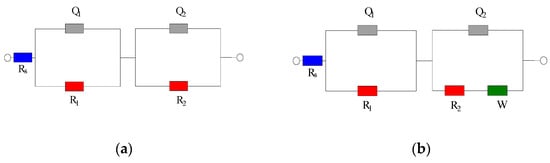

All electrochemical measurements were carried out using a Princeton PARSTAT 3000A electrochemical workstation (Princeton Applied Research, AMETEK Scientific Instruments, Oak Ridge, TN, USA). For electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, a two-electrode setup was adopted, with the embedded steel bar serving as the working electrode and the stainless steel mesh as the counter electrode. Prior to each EIS measurement, the open-circuit potential of the steel was recorded against a saturated calomel reference electrode. Linear polarization resistance tests were also performed using a three-electrode configuration steel working electrode, SCE reference, stainless steel mesh counter electrode; the steel reinforcement was polarized ±10 mV around its OCP at a scan rate of 0.1 mV/s to determine the polarization resistance. The EIS tests were conducted over a frequency range of 10 kHz down to 1 Hz, with an AC amplitude of 5 mV about the OCP. Figure 2 shows the equivalent circuits used for data fitting. In the passive-state circuit (Figure 2a), Rs represents the solution resistance; Q1 and R1 correspond to the capacitance and resistance of the cement paste cover layer on the steel; R2 represents the charge-transfer resistance of the steel; Q2 is the constant phase element of the steel interface double layer; and W is the Warburg impedance related to diffusion. For actively corroding specimens, an additional Warburg element was included as shown in Figure 2b. The EIS spectra were fitted to the appropriate equivalent circuit using a least-squares algorithm in VersaStudio (v2.60.6; Princeton Applied Research, AMETEK Scientific Instruments) to extract the component parameters including Rp.

Figure 2.

EIS Equivalent Circuit Diagram for Steel–Cement Paste Specimen. (a) Equivalent Circuit Diagram of the Specimen in Steel Passivation State. (b) Equivalent Circuit Diagram of the Specimen in Steel Depassivation State.

Figure 2 shows the equivalent circuit diagram used for fitting. In the diagram, Rs represents the resistance of the solution in the specimen; Q1 and R1 correspond to the resistance of the cement paste protective layer on the steel surface and the constant phase element (CPE), respectively; R2 represents the corrosion reaction resistance, i.e., the true polarization resistance; Q2 represents the constant phase element of the steel interface double layer, and W denotes the Warburg diffusion impedance, reflecting the finite-rate mass transport of ions in the pore solution or along the steel–cement interface.

3. Experimental Results and Analysis

3.1. Results Without Corrosion Inhibitors

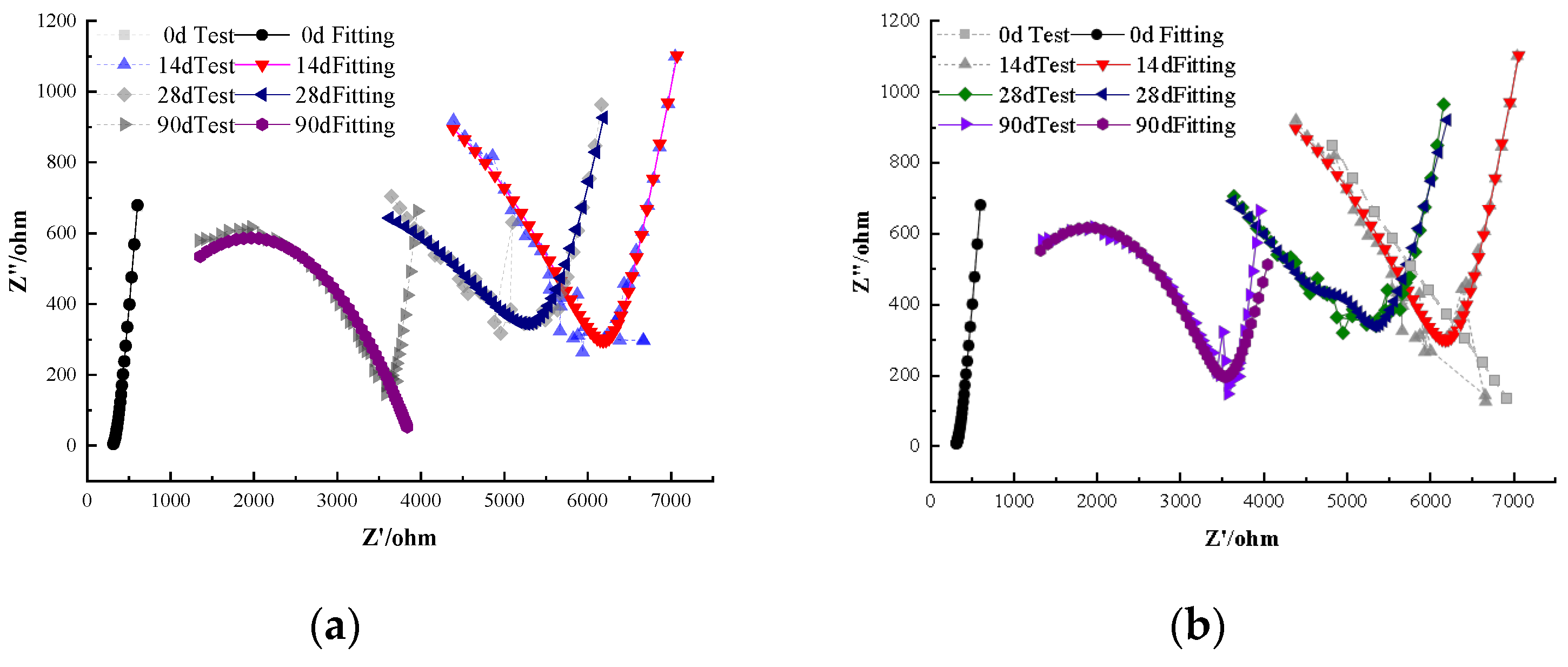

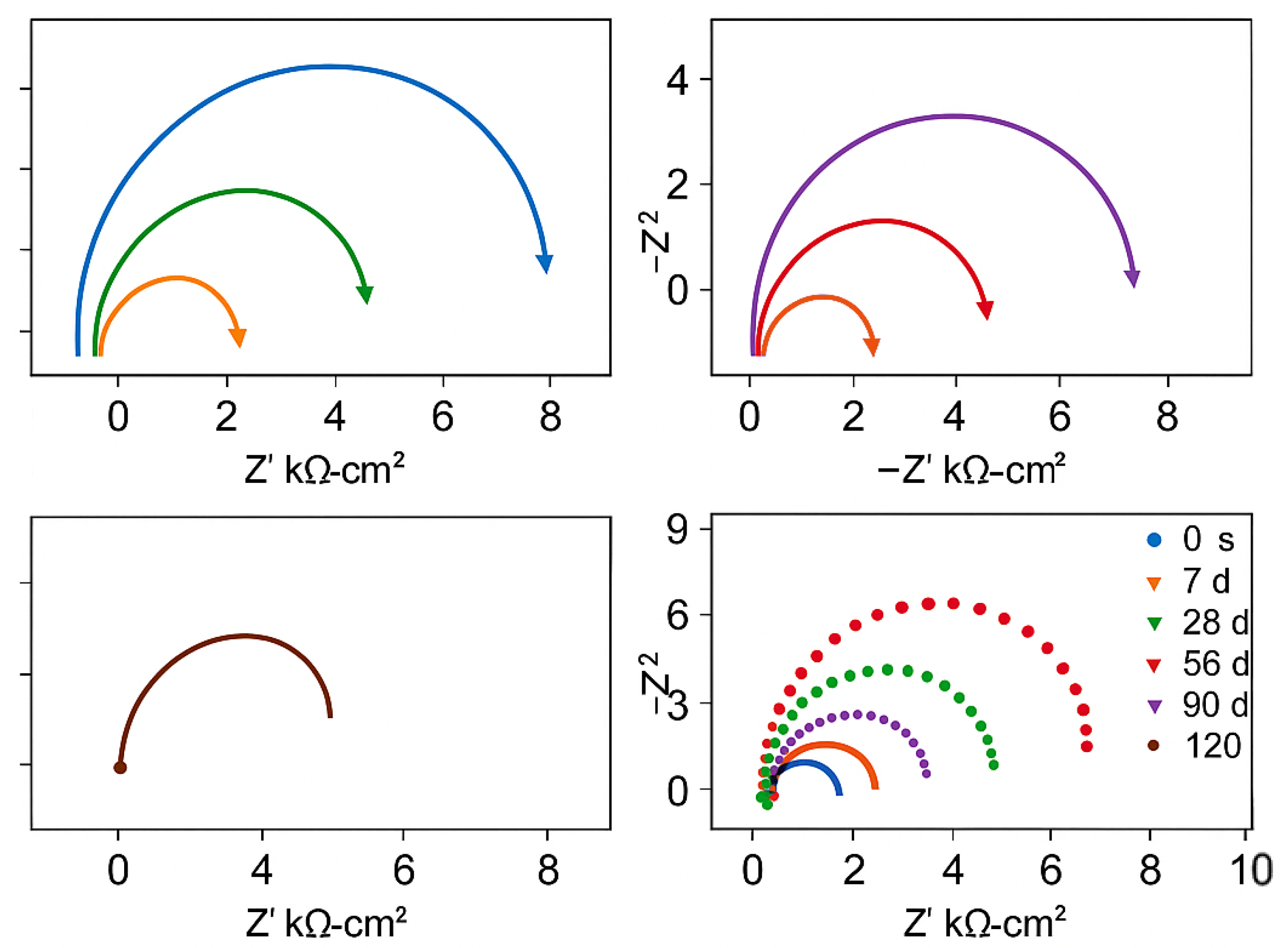

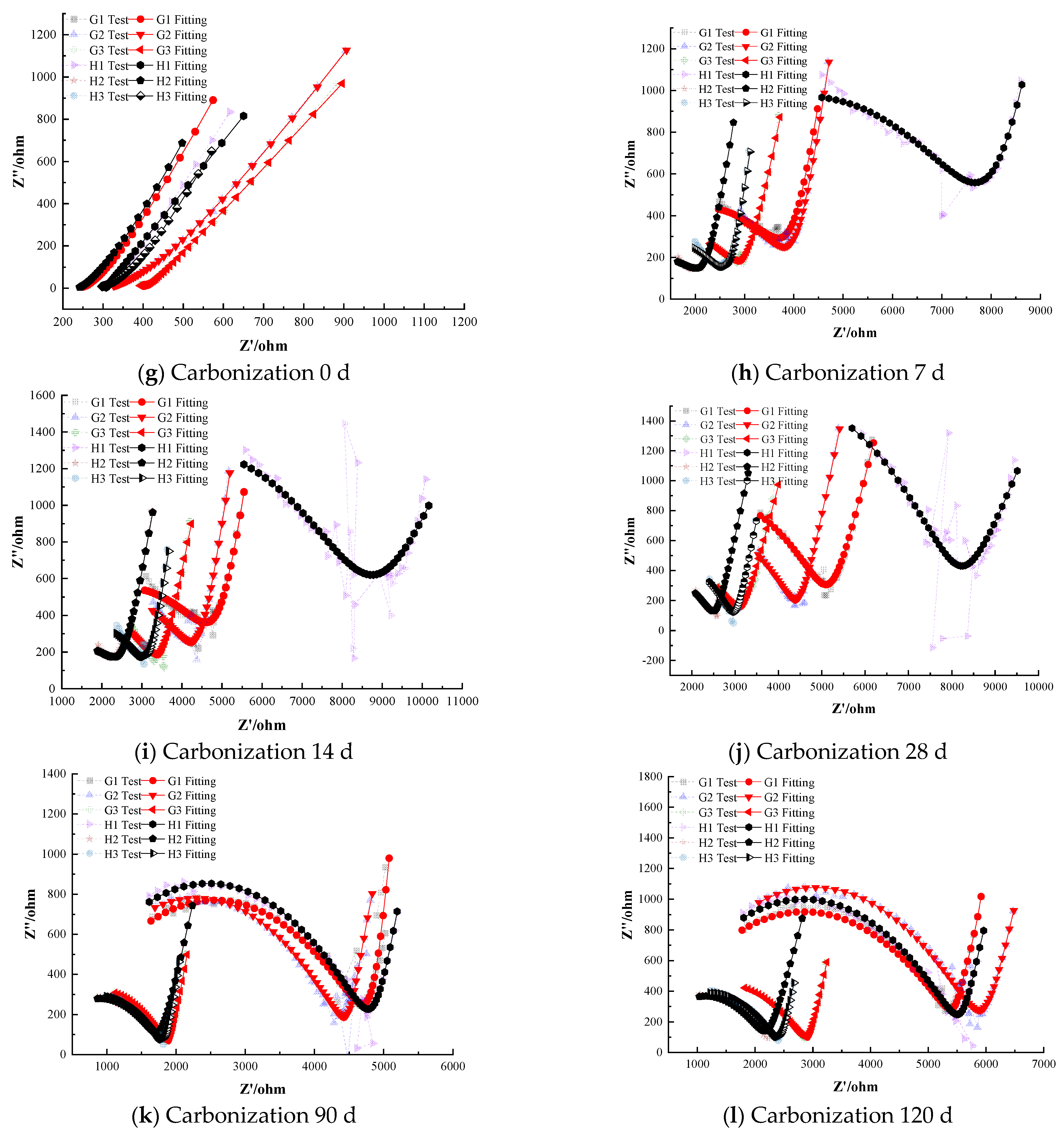

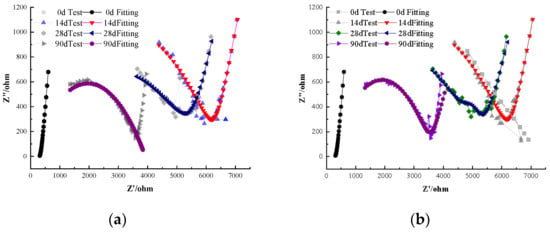

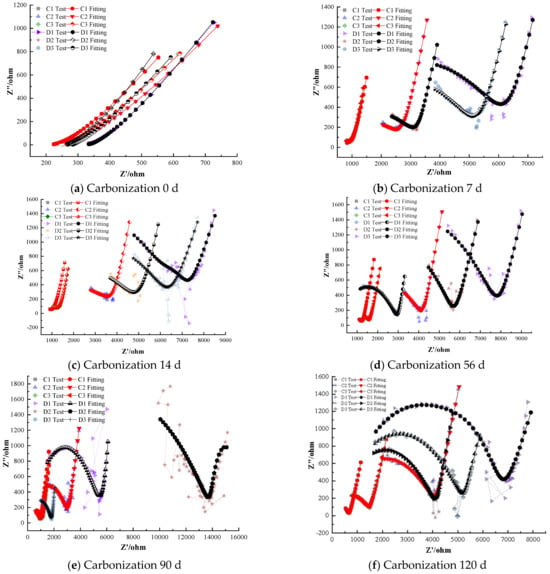

This group contained no corrosion inhibitors and served as the control for comparison with the BTA, DMEA, and other inhibitor groups. Figure 3 shows the electrochemical characteristics of steel–cement paste specimens without corrosion inhibitors under carbonation conditions at different ages. As observed in the Nyquist plot, when carbonation has not yet begun (0 days), there are two semicircles in the high-frequency and low-frequency regions, respectively. The first semicircle appears in the high-frequency region and represents the charge-transfer resistance at the steel–cement interface. The second semicircle, located in the low-frequency region, corresponds to diffusion-related impedance, reflecting the mass transport of ionic species in the pore solution. In the high-frequency region, the data points are very dense, and in the low-frequency region, there is a nearly vertical line with a slope close to 90°. This is a typical characteristic of steel in a passivated state within the cement paste [16,17]. Accordingly, the initial polarization resistance Rp was on the order of 104 Ω·cm2, and the open-circuit potential was around −0.10 V vs. SCE, confirming that the steel was in a passive state prior to carbonation.

Figure 3.

Electrochemical Characteristics of Specimens Without Corrosion Inhibitors. (a) Nyquist Plot under the Equivalent Circuit of Steel Passivation. (b) Nyquist Plot under the Equivalent Circuit of Steel Depassivation.

After 14 days of carbonation, the radius of the Nyquist semicircle decreases progressively compared with the initial (0-day) state, indicating a reduction in polarization resistance as carbonation proceeds. This change also indicates the appearance of a Warburg diffusion impedance associated with the mass transport of ionic species mainly carbonate/bicarbonate ions and dissolved oxygen within the pore solution. As the carbonation time increases, the steel–cement paste specimen begins to experience carbonation-induced degradation, with the steel passivation film becoming unstable and starting to depassivate and crack, either partially or fully. The structure at the steel–cement paste interface becomes more complex as the passivation film deteriorates [18,19,20,21]. In this study, we consider the steel to be “depassivated” once the Nyquist response changes from a near-vertical line at low frequency to a pronounced semicircle signifying the need for a diffusion element in the fitting circuit, Figure 2b. This transition typically corresponds to an abrupt decrease in Rp and a shift in OCP to less than approximately −0.35 V, indicating the onset of active corrosion.

By the 28th day of carbonation, the Warburg impedance becomes more pronounced. This is evidenced by an increased radius of the semicircle in the Nyquist plot, indicating greater diffusion resistance as carbonation continues and suggesting that corrosion has initiated and is accelerating. The Nyquist plot indicates greater diffusion resistance as carbonation continues, suggesting that corrosion of the steel has initiated and is accelerating. After 90 days of carbonation, the electrochemical impedance of the steel is only half of what it was at 14 days, indicating a significant reduction in corrosion resistance. Figure 3b illustrates the large semicircle in the low-frequency region indicating the appearance of Warburg impedance, which reflects diffusion-related processes as the steel begins to depassivate. Quantitatively, the fitted Rp of the steel drops by roughly 50% between 14 and 90 days of carbonation, and the OCP of the steel shifts from around −0.20 V at 14 days to about −0.50 V by 90 days, corroborating the loss of passivity. Overall, the polarization resistance of the depassivated steel decreases gradually as carbonation progresses, with a slowing rate of decrease. Simultaneously, the corrosion resistance of the specimen weakens, the passivation film on the steel deteriorates, and the rate of steel corrosion slows as carbonation progresses, likely due to the formation of a stable passive film on the steel surface, which limits further corrosion [22,23,24].

3.2. Corrosion Inhibition Performance of Anodic Inhibitors

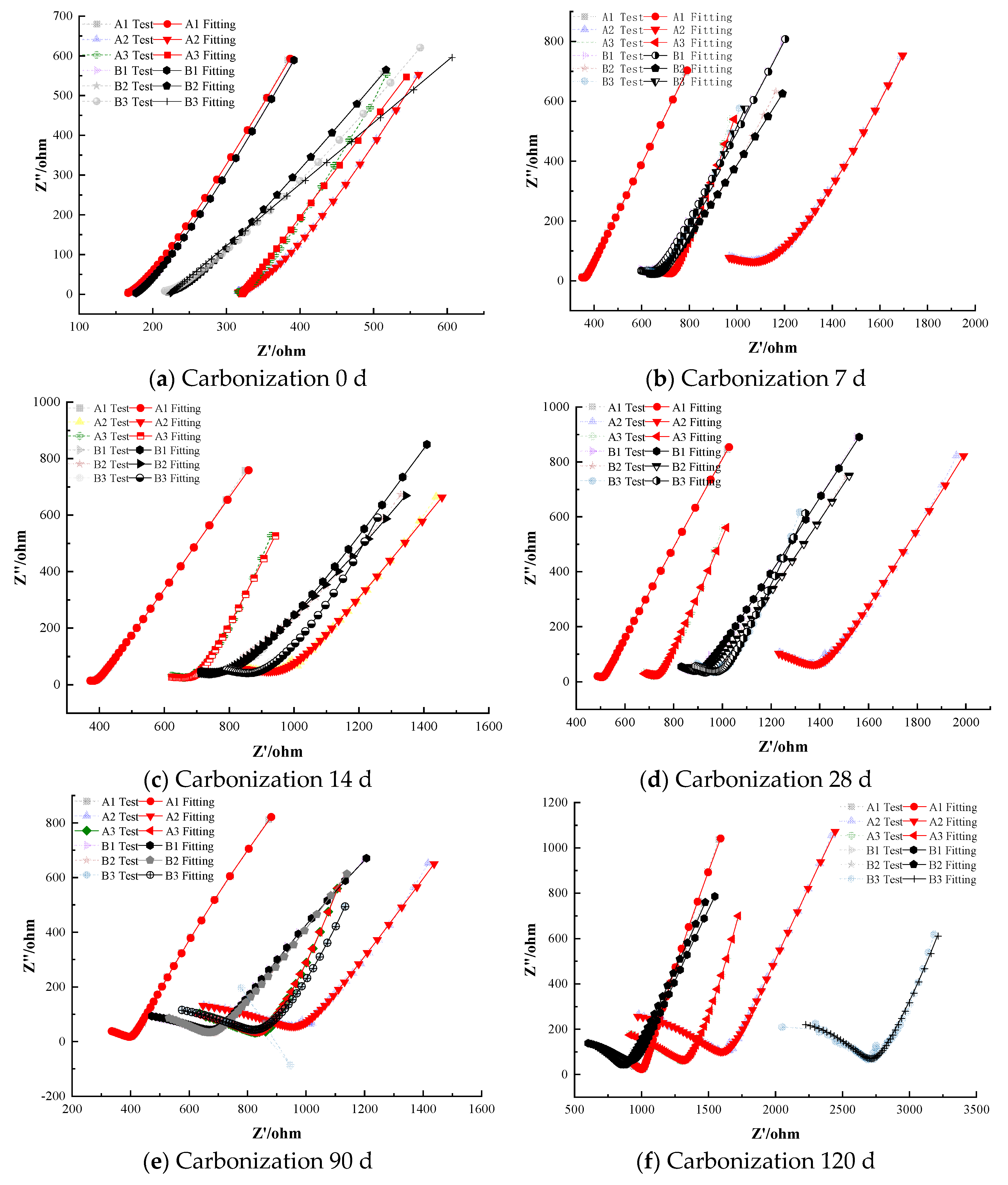

As shown in Figure 3a, at the onset of carbonation (0 days), the steel in the specimens containing sodium chromate and sodium molybdate remains in a passivated state. At the start of carbonation, the specimens exhibit high electrochemical impedance, indicating that the steel is stable, with a dense passivation film and an intact cement paste protective layer. Figure 3 shows the Nyquist plot which demonstrates the charge-transfer resistance represented by the high-frequency semicircle. The radius of this semicircle corresponds to the polarization resistance (Rp) of the steel, indicating enhanced corrosion resistance. Comparing the impedance curves of Group A and Group B, at the beginning of carbonation, no corrosion occurred in the steel of the specimens containing anodic inhibitors, with sodium chromate showing slightly better corrosion inhibition than sodium molybdate, though the difference is not significant The term no corrosion refers to the absence of noticeable corrosion at the initial stage of carbonation, where the steel remained in a passivated state. The observed better corrosion inhibition means that the inhibitors, particularly sodium chromate, contributed to the stability and effectiveness of the passivation film, thus delaying the onset of corrosion [25,26]. In all cases, the initial Rp values were on the order of 104 Ω·cm2 and the OCP around –0.10 V, indicating a robust passive state at 0 days for all inhibitor-containing specimens.

After 7 days of carbonation, the steel in A2 and B1 has started to depassivate, with surface cracking and a transition from a stable passivated state to an active, corrosion-prone state. However, the impedance values in other groups remain high, suggesting the formation of a thick passivation film that effectively protects the steel and provides strong corrosion resistance. By 28 days, the steel in A1 and B2 begins to depassivate, with lower impedance values, indicating a weakened protective effect of the passivation film, and the onset of pitting on the steel surface [27].

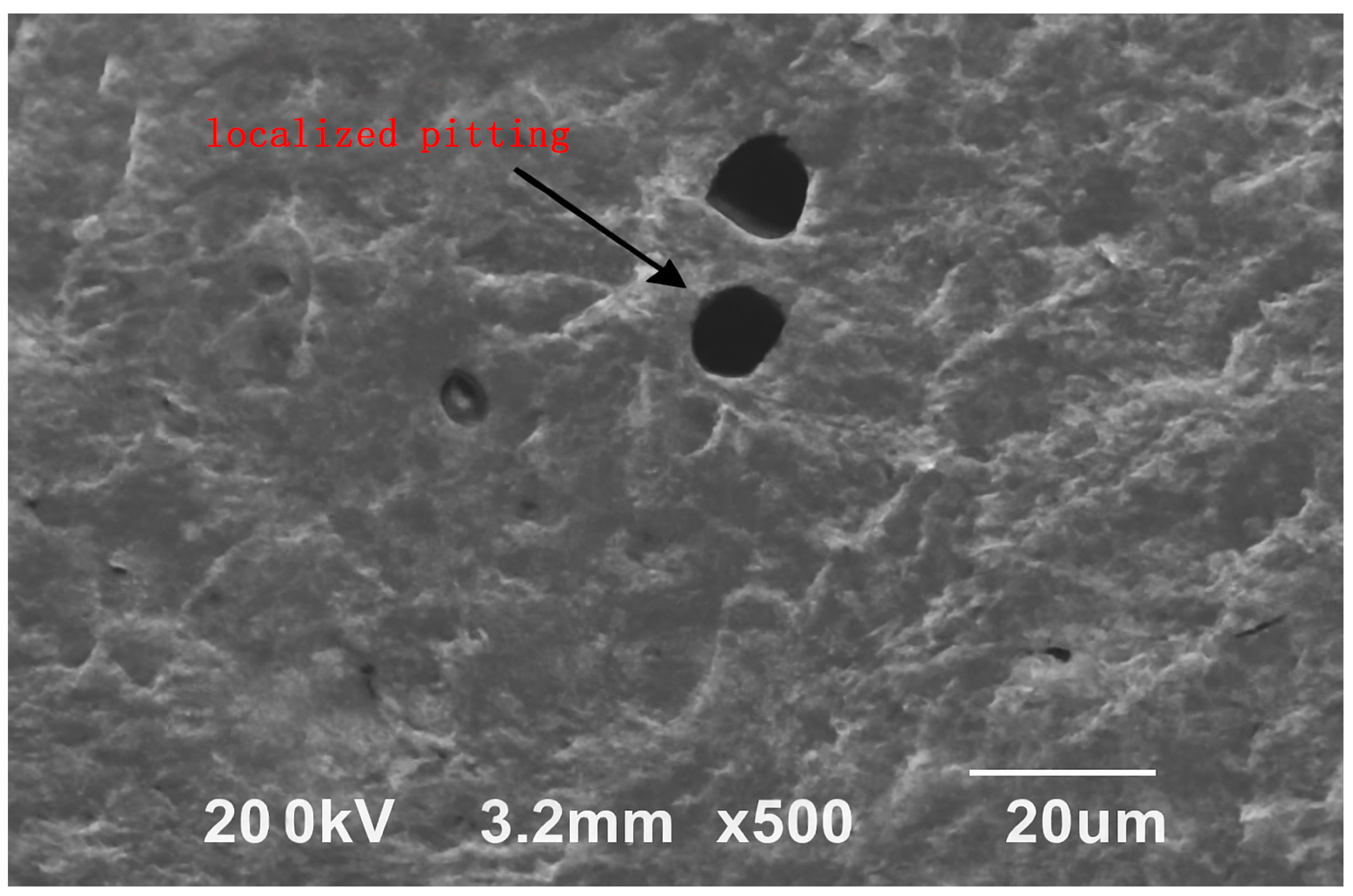

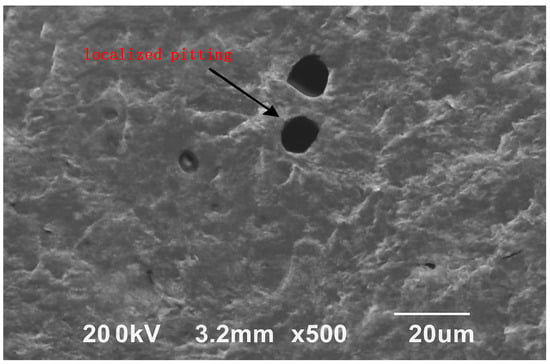

To further verify the occurrence of localized pitting induced by anodic inhibitors at inappropriate concentrations, the steel surface was examined by SEM. As shown in Figure 4, distinct hemispherical pitting cavities approximately 10–20 μm in diameter were observed, confirming that destabilization of the passive film occurred during carbonation when anodic inhibitor dosage exceeded the optimal range.

Figure 4.

SEM image of the steel surface showing localized pitting after exposure to anodic inhibitor at high dosage.

Comparing the non-depassivated specimens at 28 days, sodium molybdate shows slightly better corrosion inhibition than sodium chromate [28,29]. Specifically, by 7 days the Rp of specimens A2 and B1 had dropped by roughly an order of magnitude, whereas other inhibitor-treated specimens still exhibited Rp on the order of 104 Ω·cm2. Notably, the specimen with 1.0% sodium molybdate (B2) remained passive at 28 days while the specimen with 1.0% sodium chromate (A2) had already shown signs of depassivation by that time, indicating that molybdate provided more prolonged protection at equal dosage.

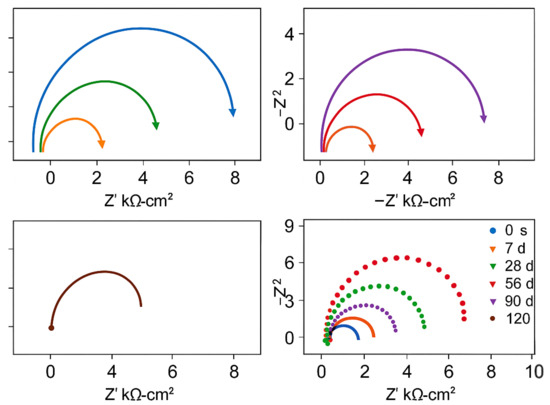

At 120 days of carbonation, the specimens A3 containing 2.0% sodium chromate and B3 containing 2.0% sodium molybdate remain in a passivated state, providing good corrosion inhibition. The impedance of B3 is higher than that of A3, suggesting that, at equal dosages, sodium molybdate offers slightly better corrosion inhibition than sodium chromate. For the depassivated specimens, the impedance difference between Groups A and B is minimal, and the impedance decreases with time, as localized pitting corrosion evolves into more extensive corrosion. For the depassivated specimens, impedance values were recorded across carbonation periods (0, 7, 28, 56, 90, and 120 days), and the electrochemical response showed a continuous decrease in the Nyquist arc radius and polarization resistance (Rp). For example, in Group A2 (1.0% sodium chromate), the fitted Rp dropped from approximately 1.2 × 104 Ω·cm2 at 7 days to 3.8 × 103 Ω·cm2 at 120 days. Similarly, Group B2 (1.0% sodium molybdate) showed a decline from 1.4 × 104 Ω·cm2 to 4.2 × 103 Ω·cm2 over the same period. These impedance reductions correlate with visible corrosion features, including localized pitting observed via SEM after 90 days. The corresponding Nyquist plots for depassivated specimens at each time point are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Electrochemical impedance evolution of depassivated specimens (Groups A2 and B2) under carbonation conditions at various aging times.

Once external moisture and oxygen penetrate, complete corrosion of the steel can occur [30]. By 120 days, both the 2.0% chromate (A3) and 2.0% molybdate (B3) specimens remained passive; the polarization resistance of B3 was roughly 10% higher than that of A3, reinforcing the slightly superior efficacy of molybdate at the same concentration. In the depassivated specimens from Groups A and B, the impedance values were uniformly low, indicating that once corrosion initiated, its progression was similarly rapid regardless of inhibitor type.

Compared to the blank control group (0-0), the addition of anodic inhibitors has a certain inhibitory effect on steel corrosion under carbonation conditions, with the corrosion inhibition effect increasing with the dosage. However, within a certain concentration range, anodic inhibitors may cause pitting corrosion on the steel, accelerating the onset of corrosion (Figure 6).

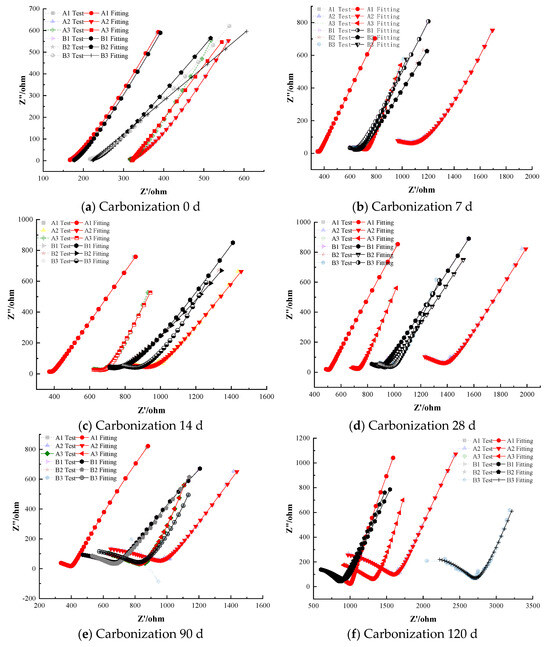

Figure 6.

Electrochemical Characteristics of Specimens with Anodic Corrosion Inhibitors under Carbonation Conditions.

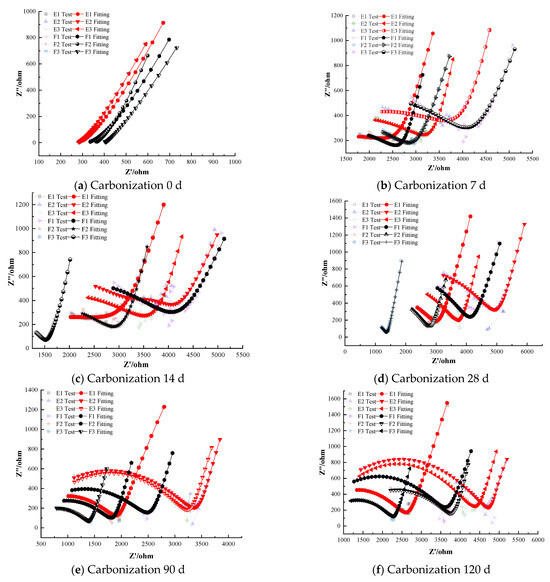

3.3. Corrosion Inhibition Performance of Cathodic Inhibitors

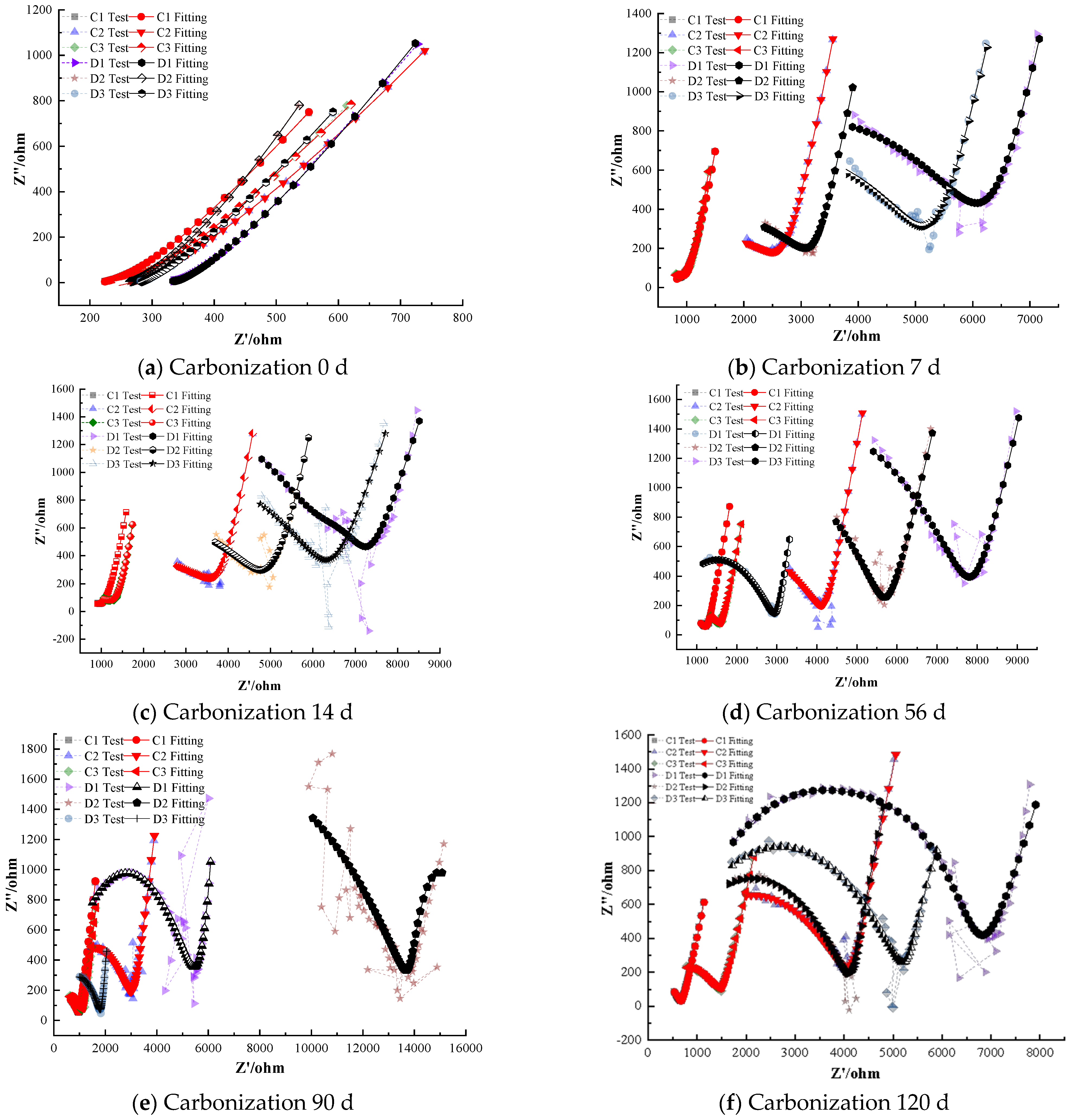

Figure 7 shows the electrochemical impedance spectra of steel–cement paste specimens with cathodic corrosion inhibitors under carbonation conditions. As shown in Figure 7, as curing age increases, the impedance of the passivation film on the steel surface in the specimens with cathodic inhibitors decreases gradually, indicating that the protective effect of the passivation film diminishes over time [31,32].

Figure 7.

Electrochemical Characteristics of Specimens with Cathodic Corrosion Inhibitors.

When the dosage of cathodic inhibitors is low, with increasing curing age, the radius of the semicircle in the high-frequency region of the Nyquist plot decreases, reflecting a weakening of the corrosion resistance of the depassivated steel. Meanwhile, a large semicircle appears in the low-frequency region, indicating that the depassivated steel has started to corrode and is in an active state. For example, specimens with 0.5% BTA corrosion inhibitor show depassivation after 90 days of carbonation, specimens with 0.5% DMEA depassivate after 28 days, and specimens with 1.0% DMEA depassivate after 90 days. The polarization resistance of the depassivated steel decreases gradually with time, and the rate of decrease slows, suggesting that as the curing age increases, the steel gradually corrodes with a decreasing corrosion rate [33,34]. This comparison indicates that at a low inhibitor level of 0.5%, BTA prolonged the passive state up to 90 days, whereas DMEA provided protection for only about 28 days before depassivation occurred.

Specimens with 2.0% cathodic inhibitors maintain good corrosion inhibition performance even after 120 days of carbonation, indicating that a 2.0% dosage of cathodic inhibitors can effectively inhibit corrosion under carbonation conditions and significantly slow down the corrosion rate of the steel [35]. Even at 120 days, the specimens with 2.0% BTA or 2.0% DMEA showed no evidence of depassivation; their Nyquist plots retained the characteristic high impedance of passive steel, confirming that a sufficiently high concentration of cathodic inhibitor can nearly completely prevent carbonation-induced corrosion.

To quantitatively compare the inhibition performance of all formulations, the impedance values at different carbonation ages were extracted from the EIS fitting results. These values are summarized in Table 3, which clearly illustrates the evolution of impedance with time for each inhibitor type. The data confirm the significantly higher impedance of specimens containing anodic and composite inhibitors compared with the control and cathodic-inhibitor groups, consistent with the electrochemical trends shown in Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Table 3.

Impedance values (Rp, Ω·cm2) of specimens with different inhibitors at various curing ages.

Comparing the corrosion inhibition performance of BTA and DMEA cathodic inhibitors, BTA performs better than DMEA at lower dosages. For instance, steel in specimens with 1.0% BTA remains passivated even after 120 days of carbonation, while steel in specimens with DMEA has depassivated after 90 days. However, at higher dosages, DMEA shows slightly better corrosion inhibition than BTA [36].

Cathodic inhibitors primarily function by suppressing the cathodic oxygen-reduction reaction through surface adsorption or by forming weakly protective organic films. Under carbonation conditions, the alkalinity of the pore solution decreases, and the steel surface transitions from Fe(OH)2/Fe(OH)3-dominated passive films toward more unstable iron carbonate phases. These conditions reduce the stability and adhesion strength of organic adsorption layers, making cathodic inhibitors less effective.

In contrast, anodic inhibitors such as sodium molybdate participate directly in the formation and repair of the passive film by incorporating MoO42− into the oxide layer. This produces a dense Fe–MoO4/Fe2O3 composite film that remains chemically stable even when the pore solution is partially carbonated. Because the anodic reaction Fe → Fe2+ is the rate-determining step during depassivation, stabilization of the anodic passive film yields significantly better corrosion resistance than the cathodic inhibition mechanism alone. This mechanistic difference explains why the performance of cathodic inhibitors is generally lower than that of anodic inhibitors under carbonation-induced depassivation.

This difference may be attributed to the fact that cathodic inhibitors primarily inhibit the cathodic reaction process of steel corrosion by delaying the transport of substances such as O2. BTA, in addition to inhibiting corrosion through chemical adsorption or bonding on the steel surface, also enhances the density of the cement paste [37]. On the other hand, DMEA is a liquid, and its distribution in the specimens might not be uniform during the test, potentially leading to uneven concentration around the steel, which could reduce its corrosion inhibition performance [38].

As shown in Figure 7, the Nyquist curves of the specimens containing cathodic inhibitors (BTA and DMEA) exhibit clear and progressive changes in shape as the carbonation age increases. At 0 days, all specimens display two distinct and well-developed capacitive semicircles corresponding to a stable passive film, with high polarization resistance values on the order of 104 Ω·cm2, indicating an initially intact and protective passive layer.

However, between 0 and 7 days, the impedance decreases sharply, and the high-frequency semicircle radius contracts significantly—especially for the 0.5% DMEA specimens. This drastic change is primarily attributed to the rapid early-stage carbonation, during which CO2 penetrates the pore structure quickly and reduces the pH around the steel surface. Cathodic inhibitors rely mainly on surface adsorption rather than passive-film regeneration, and therefore they cannot effectively counteract the steep loss of alkalinity during the first few days. As a result, the passive film becomes thinner, less stable, and more prone to dissolution, leading to a sudden reduction in impedance from 0 to 7 days.

From 7 to 28 days, the curve shapes evolve differently for the two cathodic inhibitors. The DMEA-containing specimens show a further depressed semicircle and the appearance of a tilted diffusion line at low frequencies, indicating the onset of unstable surface conditions and active corrosion processes. In contrast, the BTA-containing specimens retain a more rounded semicircle, and the radius decreases more gradually. This demonstrates that BTA better stabilizes the passive film under decreasing alkalinity, delaying depassivation.

At later ages (90–120 days), both inhibitors at high concentration (2.0%) still show relatively large semicircles, but the 2.0% BTA specimens maintain a larger semicircle radius and a more vertical low-frequency region, indicating stronger diffusion resistance and higher long-term impedance. Meanwhile, the 2.0% DMEA group exhibits a slightly compressed semicircle at 120 days, reflecting partial film degradation.

Overall, the combined evolution of semicircle radius, curve depression, and low-frequency diffusion response clearly demonstrates the superior stability of BTA over DMEA during carbonation exposure and explains both the curve-shape changes and the drastic drop in impedance in the early stages.

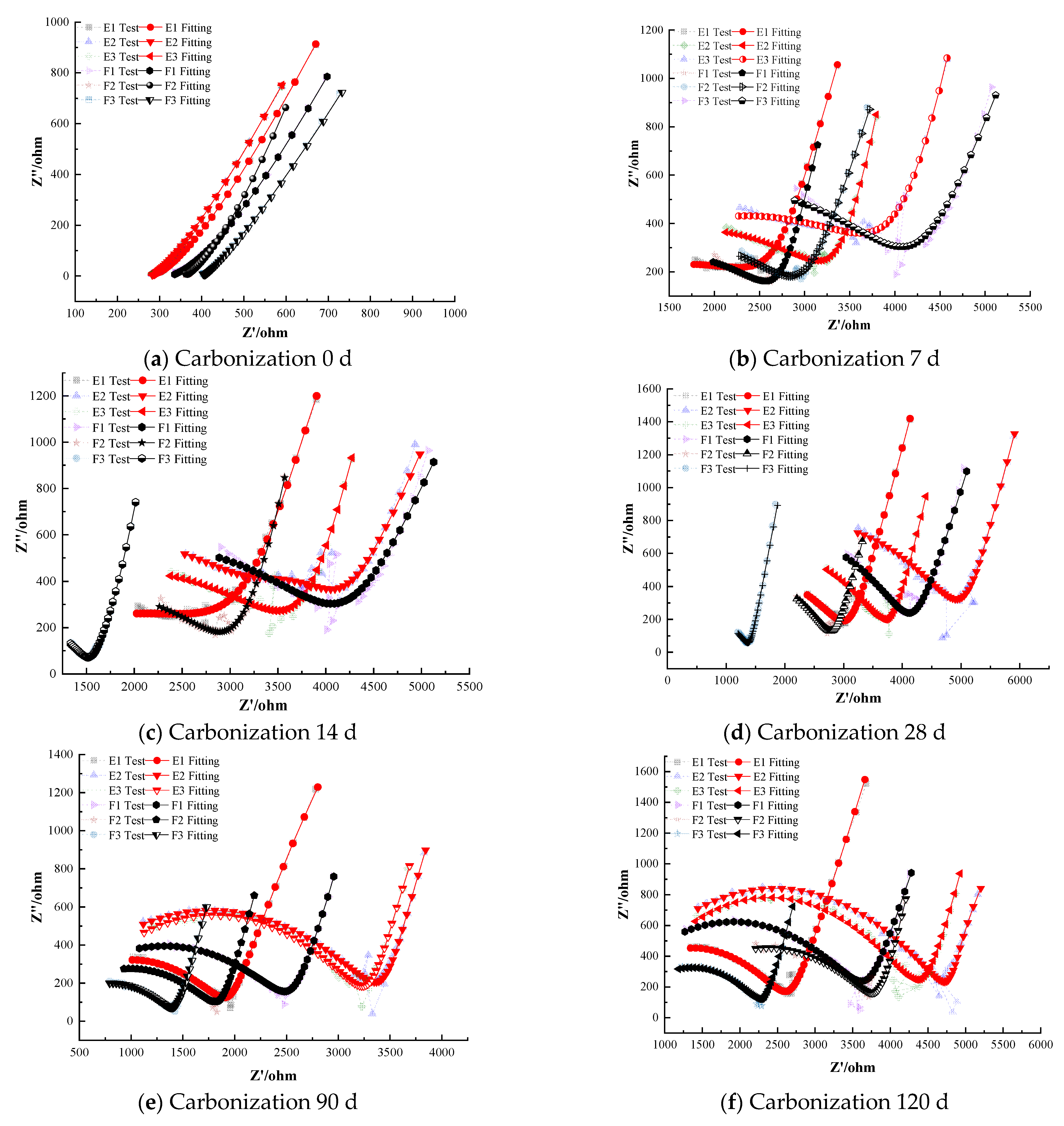

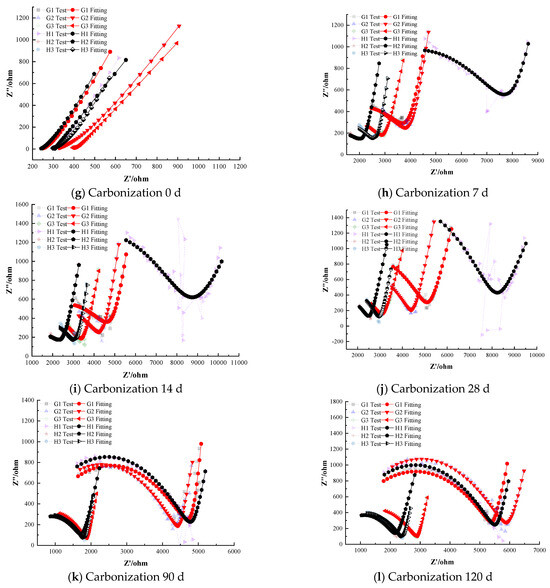

3.4. Corrosion Inhibition Performance of Composite Inhibitors

Figure 8 illustrates the electrochemical impedance spectra of steel–cement paste specimens with composite corrosion inhibitors under carbonation conditions. The figure shows that as the curing age increases, the impedance of the passivation film on the steel surface in specimens with composite inhibitors gradually decreases, indicating a deterioration in the protective effect of the passivation film. However, overall, the impedance values remain higher compared to those with anodic and cathodic inhibitors [39,40]. For instance, even after prolonged carbonation exposure, the composite inhibitor specimens retained noticeably larger Nyquist arc radii than any of the specimens with only anodic or only cathodic inhibitors.

Figure 8.

Electrochemical Characteristics of Specimens with Composite Corrosion Inhibitors.

At the onset of carbonation (0 days), the radius of the high-frequency semicircle for all specimens containing composite inhibitors corresponds to similar polarization resistance values in the range of (1.0–1.1) × 104 Ω·cm2, with differences in less than 5% among the three formulations. This confirms that the initial passive state provided by composite inhibitors is essentially equivalent across all dosages. And the low-frequency region exhibits a nearly vertical Warburg-type line, with the fitted slope measured as 88.7° (±0.5°), indicating highly restricted diffusion, indicating that the steel is in a passivated state with a dense and complete passivation film providing good protection. As carbonation progresses, the corrosion resistance of the steel in the cement paste specimens gradually weakens. Some specimens exhibit significantly reduced semicircle radii in the low-frequency region, indicating a decrease in charge-transfer resistance. This reduction demonstrates that the steel has left the passive state and entered an active corrosion state. For instance, Group G specimens (0.25% sodium molybdate + 0.25% BTA) depassivate after 28 days of carbonation, whereas Group H specimens (0.25% sodium molybdate + 0.25% DMEA) depassivate after 14 days. The polarization resistance of the depassivated steel decreases with curing age, and the rate of decrease slows, indicating gradual corrosion with a decreasing rate over time. Notably, the composite containing BTA resisted depassivation for about twice as long as the corresponding composite containing DMEA.

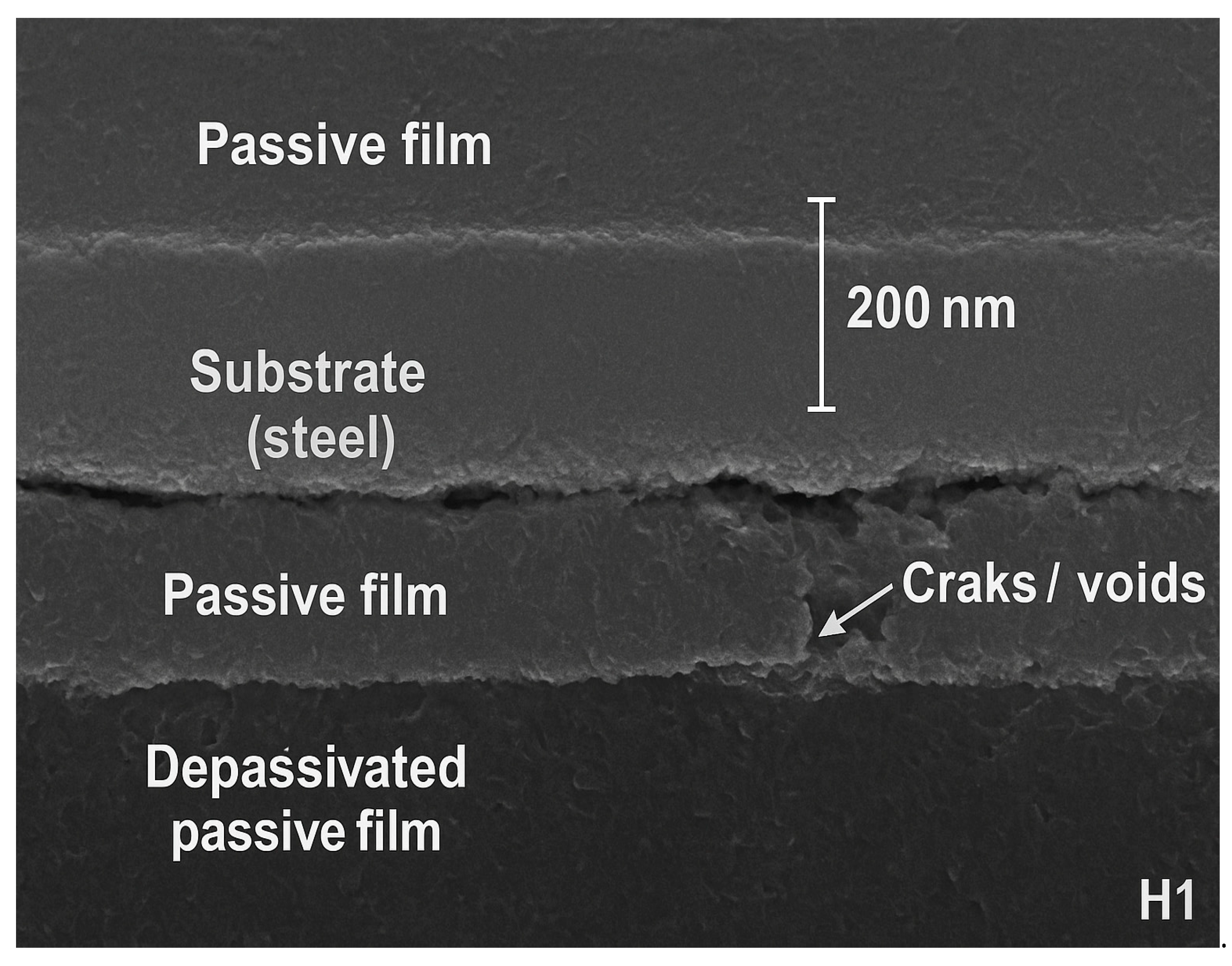

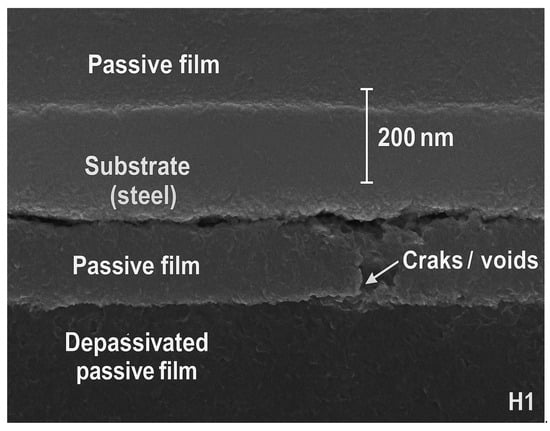

To directly verify the passive-film stability inferred from EIS, cross-sectional SEM images of the steel surface were examined for the best-performing composite (G3) and the weakest composite (H1), as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Cross-sectional SEM images of steel passive films after carbonation.

Specimens with composite inhibitors maintain good corrosion inhibition performance even after 120 days of carbonation. The quality of the EIS fitting further confirms the stability of the passive film. Specifically, the equivalent circuit fitting yields R2 values in the range of 0.985–0.996 for the BTA-containing composite inhibitors and 0.972–0.985 for the DMEA-containing composites, indicating that the passive-state model describes the electrochemical behavior with consistently lower fitting residuals for the BTA groups. This quantitative difference in fitting accuracy is consistent with their higher impedance values and delayed depassivation, demonstrating that the BTA-based composite inhibitors provide superior long-term protection. This is supported by the quantitative EIS results, where the high-frequency semicircle radius corresponds to polarization resistance values in the range of (5.5–6.0) × 103 Ω·cm2 for the BTA-based composite inhibitors, compared with ~5.0 × 103 Ω·cm2 for the DMEA-based composite inhibitors and ~1.2 × 103 Ω·cm2 for the uninhibited control. Thus, both the impedance magnitude and semicircle radius clearly distinguish the superior inhibition performance of the composite–BTA system, indicating effective corrosion inhibition and significant delay in the corrosion rate. For example, at 120 days the specimen with 2.0% MoO42− + BTA (Group G3) had an impedance magnitude roughly 20% higher than that of the specimen with 2.0% MoO42− + DMEA Group H3, reflecting BTA’s greater effectiveness in the composite formulation.

Comparing the two anodic components, sodium chromate and sodium molybdate, at lower dosages (0.5%), composite inhibitors with sodium chromate show slightly higher electrochemical impedance compared to those with sodium molybdate, without any depassivation. This behavior can be attributed to the different passivation mechanisms of molybdate and chromate ions. Under carbonation conditions, the alkalinity of the pore solution decreases and the steel surface becomes more susceptible to passive film destabilization. Chromate (CrO42−) inhibits corrosion primarily through strong anodic polarization, which is highly effective but relies on maintaining a sufficiently alkaline environment to stabilize the Cr(III)-rich passive layer. As carbonation progresses, the reduced pH weakens the chromate-derived film, making it more vulnerable to localized breakdown at higher dosages.

In contrast, molybdate (MoO42−) contributes directly to the regeneration and strengthening of the passive film by forming a Fe–MoO4 and Fe2O3 composite layer. Molybdate ions are more resistant to pH reduction and can intercalate into the oxide matrix, improving the film’s density and its ability to block ionic transport. This leads to higher charge-transfer resistance and delayed depassivation at elevated dosages, explaining why sodium molybdate provides slightly better corrosion inhibition than sodium chromate at higher concentrations. To further confirm the formation mechanism of the Mo-based passive film, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy was performed on the steel surface after 120 days of carbonation. As shown in Table 4, the passive film mainly consists of Fe, Mo, and O, which supports the presence of a Fe–MoO4/Fe2O3 composite oxide layer. This composition verifies that sodium molybdate participates directly in the generation and stabilization of the passive film, thereby explaining its superior corrosion inhibition performance compared with sodium chromate.

Table 4.

EDS elemental composition of the Mo-containing passive film.

Overall, among the tested groups, H1 shows the worst corrosion inhibition performance, while G3 exhibits the best. It is evident that composite inhibitors, which combine both anodic and cathodic components, are more efficient than single-type inhibitors, providing better protection without causing localized corrosion at certain concentrations.

4. Conclusions

- Carbonation Effects on Cement Paste Materials: Under carbonation conditions, the Nyquist plot of cement paste materials exhibits a dual capacitive arc, characterized by a smaller capacitive arc radius in the high-frequency region and a larger capacitive arc radius in the low-frequency region. The Bode plot shows two distinct phase angle changes, indicating two time constants. The two time constants observed in the Bode plot represent two distinct electrochemical processes. The first time constant corresponds to the charge-transfer resistance at the steel–cement interface, indicating the passivation behavior of the steel. The second time constant is associated with the diffusion of ions in the pore solution, reflecting the mass transport processes that occur as carbonation progresses. In the absence of corrosion inhibitors, specimens begin to corrode early during carbonation, and the impedance of passivated steel decreases with increasing age.

- Performance of Anodic Corrosion Inhibitors: Anodic corrosion inhibitors provide effective corrosion protection under carbonation conditions, with performance improving as the concentration of the inhibitor increases. However, at certain concentrations, anodic inhibitors can lead to localized pitting and accelerate corrosion. Among the tested anodic inhibitors, sodium molybdate shows slightly better corrosion inhibition compared to sodium chromate. Sodium molybdate forms a passivation film on the steel surface with components mainly including Fe-MoO4 and Fe2O3, effectively slowing down the corrosion process.Performance of Cathodic Corrosion Inhibitors: Cathodic corrosion inhibitors also offer corrosion protection under carbonation conditions, with effectiveness increasing with the concentration of the inhibitor. However, their performance is generally lower than that of anodic inhibitors. Among cathodic inhibitors, BTA shows significantly better performance than DMEA.

- Performance of Composite Corrosion Inhibitors: Composite corrosion inhibitors provide the best corrosion protection under carbonation conditions. Their performance improves with increasing concentrations of the cathodic inhibitor. Specifically, the combination of sodium molybdate and BTA delivered the most effective corrosion protection, with the steel remaining passive, exhibiting a high corrosion potential and low corrosion current throughout the carbonation period. These results suggest that composite inhibitors are highly promising for practical applications; however, further long-term studies under realistic conditions are needed to confirm their effectiveness and reliability in engineering practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L., R.C. and Y.M.; methodology, X.L., R.C. and Y.M.; formal analysis, X.L., R.C. and Y.M.; investigation, X.L., R.C. and Y.M.; resources, X.L. and R.C.; data curation, X.L. and R.C.; writing—original draft preparation, X.L. and R.C.; writing—review and editing, X.L. and R.C.; visualization, X.L. and R.C.; supervision, X.L. and R.C.; project administration, X.L. and R.C.; funding acquisition, X.L. and R.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 12072107), The Education Department of Henan Province: (No. 25A580009), Transportation Engineering (Henan Provincial Key Discipline), Huanghe Jiaotong University (No. 2023SZDXK318).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author sincerely thanks the members of the research group for their careful guidance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shahryari, Z.; Gheisari, K.; Yeganeh, M.; Ramezanzadeh, B. MoO42−-doped oxidative polymerized pyrrole-graphene oxide core-shell structure synthesis and application for dual-barrier & active functional epoxy-coating construction. Prog. Org. Coat. 2022, 167, 106845. [Google Scholar]

- Song, C.; Jiang, C.; Gu, X.L. Modeling capillary water absorption behavior of concrete with carbonated surface layers. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 93, 109880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, I.W.; Ammar, S.; Kumar, S.S.; Ramesh, K.; Ramesh, S. A concise review on corrosion inhibitors: Types, mechanisms and electrochemical evaluation studies. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2022, 19, 241–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Li, R.; Yang, Z.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, H.; Cui, X.; Nong, Z. Research Progress on the Preparation and Tribological Properties of Self-Lubricating Coatings Fabricated on Light Alloys. Coatings 2025, 15, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; Zhou, Z.; Nie, X.; Chen, Y.; Cao, H.; Liu, B.; Zhang, N.; Said, Z.; et al. Cutting fluid corrosion inhibitors from inorganic to organic: Progress and applications. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2022, 39, 1107–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Zuo, Y. Inhibition of Q235 Carbon Steel by Calcium Lignosulfonate and Sodium Molybdate in Carbonated Concrete Pore Solution. Molecules 2019, 24, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Zuo, Y.; Lin, B. The compounded inhibition of sodium molybdate and benzotriazole on pitting corrosion of Q235 steel in NaCl + NaHCO3 solution. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2017, 192, 86–93. [Google Scholar]

- Petričević, A.; Gojgić, J.; Bernäcker, C.I.; Rauscher, T.; Bele, M.; Smiljanić, M.; Hodnik, N.; Elezović, N.; Jović, V.D.; Krstajić Pajić, M.N. Ni-MoO2 Composite Coatings Electrodeposited at Porous Ni Substrate as Efficient Alkaline Water Splitting Cathodes. Coatings 2024, 14, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Shu, J.; Jing, H.; Su, C.; Peng, X.; Li, T.; Xu, C.; Xia, M.; Wang, J.; Yang, J.; et al. Enhanced corrosion resistance of zinc-rich epoxy anti-corrosion coatings using graphene-Fe2O3 and HEDP. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2025, 149, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Ma, H.; Shi, J. Enhanced corrosion resistance of reinforcing steels in simulated concrete pore solution with low molybdate to chloride ratios. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 110, 103589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Wu, M.; Ming, J. In-depth insight into the role of molybdate in corrosion resistance of reinforcing steel in chloride-contaminated mortars. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 132, 104628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.X.; Li, C.Q.; Luo, Y.J.; He, B.; Yang, B.; Jin, P.J. XPS Depth Profile Analysis of Sodium Molybdate-Based Conversion Film on Bronze Surface. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2025, 45, 1979–1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M.A.; Amin, S.; Mohamed, A.A. Current and emerging trends of inorganic, organic and eco-friendly corrosion inhibitors. Rsc Adv. 2024, 14, 31877–31920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, J.; Lu, Z.; Zhu, Q.; Li, L.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Song, G.; Zhang, L. Study on the corrosion inhibition performance of composite inhibitor on carbon steel in stone processing wastewater. Asia-Pac. J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 19, e2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 1499.2-2024; Steel for the Reinforcement of Concrete—Part 2: Hot Rolled Ribbed Bars. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2024.

- Zomorodian, A.; Behnood, A. Review of Corrosion Inhibitors in Reinforced Concrete: Conventional and Green Materials. Buildings 2023, 13, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, D.; Rao, S.A.; Gaonkar, S.L.; Kumari P, P. Hybrid metal matrix composite: A comprehensive review on its fabrication, corrosion behaviour and inhibition. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsa, A.; Barker, R.; Hua, Y.; Barmatov, E.; Hughes, T.L.; Neville, A. Impact of corrosion products on performance of imidazoline corrosion inhibitor on X65 carbon steel in CO2 environments. Corros. Sci. 2021, 185, 109423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singla, K.; Brown, B.; Nešić, S. Importance of Location for Addition of Surfactant Inhibitors in Corrosion Experiments. Corrosion 2024, 80, 603–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Guan, X.; Shi, J. Synergistic inhibition mechanism of phosphate and phytic acid on carbon steel in carbonated concrete pore solutions containing chlorides. Corros. Sci. 2022, 208, 110637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolzoni, F.; Ormellese, M.; Pedeferri, M.; Proverbio, E. Big milestones in the study of steel corrosion in concrete. Struct. Concr. 2023, 24, 115–126. [Google Scholar]

- Dacio, L.J.; Troconis de Rincon, O.M.; Alvarez, L.X.; Castaneda, H.; Quesada Román, L.; Rincon Troconis, B.C. Evaluating 1-Benzyl-4-Phenyl-1H-1,2,3-Triazole as a Green Corrosion Inhibitor in a Synthetic Pore Solution to Protect Steel Rebars. Corrosion 2023, 79, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purnima; Goyal, S.; Luxami, V. Corrosion inhibition mechanism of aromatic amino acids for steel in alkaline pore solution simulating carbonated concrete environment. Mater. Corros. 2024, 75, 39–60. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Lai, Y.; Hu, J. A surface molecular assembly-based composite inhibitor for mitigating corrosion in dynamic supercritical CO2 aqueous environment. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 495, 153193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Li, G.; Zeng, J.; Gao, G. Molybdate-Doped Copolymer Coatings for Corrosion Prevention of Stainless Steel. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2014, 131, 40602. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Choi, J.K. Electrochemical and Gravimetric Assessment of Steel Rebar Corrosion in Chloride- and Carbonation-Induced Environments. Buildings 2025, 15, 3647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhang, Z.; Sukhbat, B.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Yan, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; et al. Smart inhibitor systems towards anti-corrosion: Design and applications. Rsc Appl. Polym. 2025, 3, 532–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Li, C.; Li, D.; Chen, R.; Chen, J. Modelling chloride diffusion in concrete with carbonated surface layer. Mag. Concr. Res. 2024, 76, 1048–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harilal, M.; George, R.; Albert, S.; Philip, J. A new ternary composite steel rebar coating for enhanced corrosion resistance in chloride environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 320, 126307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Li, X.; Liu, J. Effect of Rust Inhibitor on Passive Film of Rebar in Cement Paste Under Carbonation. Rev. Romana Mater. 2022, 52, 278–283. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Wang, X.; Peng, J.; Li, D. Chloride penetration and material characterisation of carbonated concrete under various simulated marine environment exposure conditions. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 429, 135885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, F.; Wang, Z.; Ma, H.; Wu, Y.C. Advances in polymer corrosion inhibitors: Mechanisms, challenges, and prospects. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 46, 112759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnima; Goyal, S.; Luxami, V. Exploring the corrosion inhibition mechanism of Serine (Ser) and Cysteine (Cys) in alkaline concrete pore solution simulating carbonated environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 384, 131433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnima; Tiwari, A.K.; Goyal, S.; Luxami, V. Developing the inhibition mechanism for amide-based amino acids in carbonated concrete environment and assessing the migration ability in concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 76, 107048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, D.E.A.; Meira, G.R.; Quattrone, M.; John, V.M. A review on reinforcement corrosion propagation in carbonated concrete-Influence of material and environmental characteristics. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 140, 105085. [Google Scholar]

- Song, C.; Jiang, C.; Gu, X.-L.; Fang, J. Modeling electrochemical chloride extraction in surface carbonated concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 460, 142591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Bi, X.; Zhao, X.; Bai, Z.; Li, Z.; Chu, H.; Jiang, L.; Shi, J. Modified passivity and pitting corrosion resistance of a corrosion-resistant rebar in carbonated concrete pore solutions with different contents of carbonate/bicarbonate ions. J. Sustain. Cem.-Based Mater. 2025, 14, 338–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmora, G.P.V.; Filho, E.P.B.; Conterato, A.A.M.; Roso, W.S.; Pereira, C.E.; Dettmer, A. Methods of corrosion prevention for steel in marine environments: A review. Results Surf. Interfaces 2025, 18, 100430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, P.; Li, A.; Zhang, J.; Chen, R.; Luo, X.; Wen, L.; Wang, C.; Lv, X. Research Status and Development Trend of Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing Technology for Aluminum Alloys. Coatings 2024, 14, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Ye, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Yu, H.; Seibou, A.-O. Ethanolamines corrosion inhibition effect on steel rebar in simulated realkalized concrete environments. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2023, 22, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).