High Cavitation Resistance Performance of Al0.3CoCrFeNi Coating Reinforced by Ternary Cr2AlC Compound

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

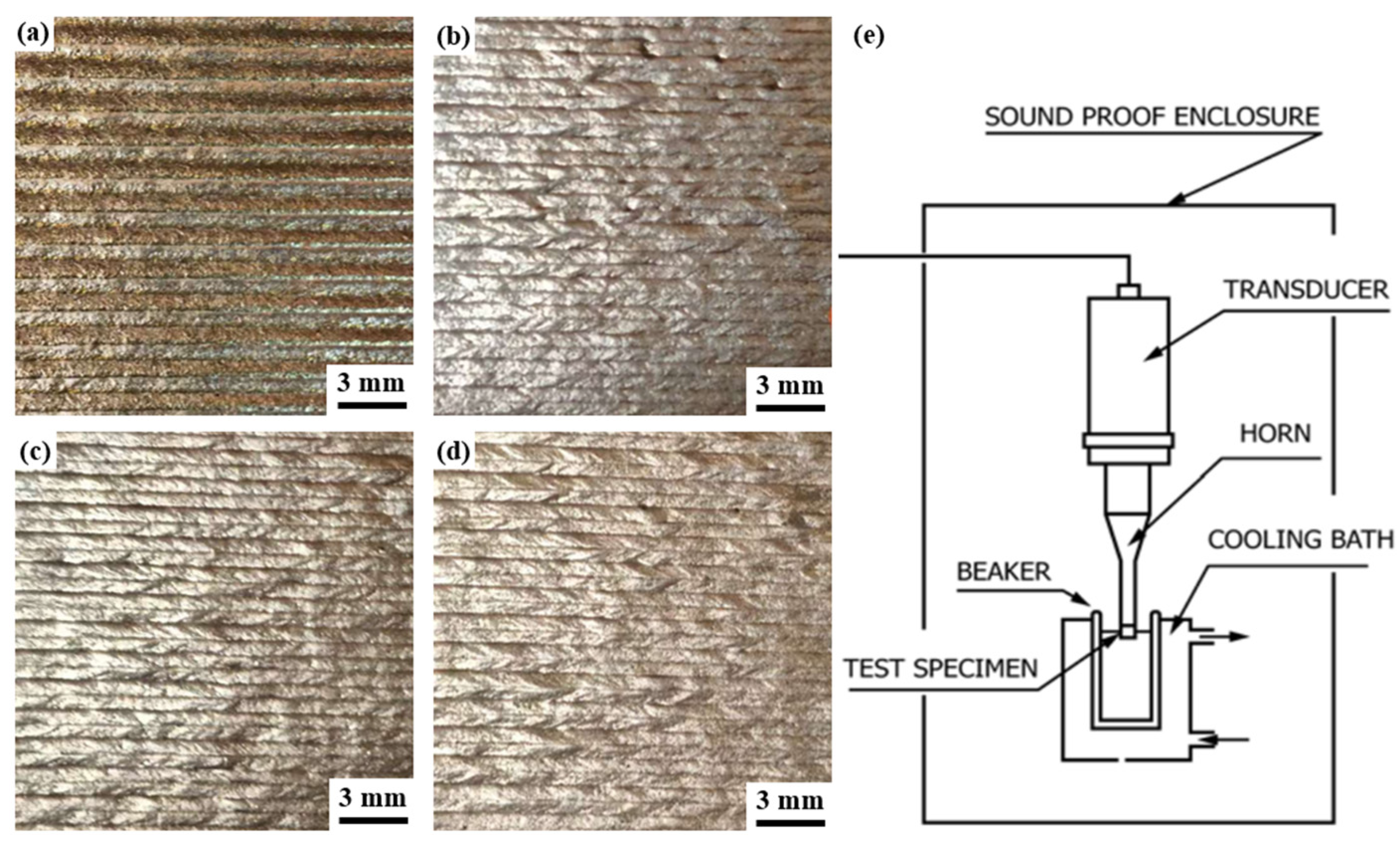

2.1. Experimental Materials and Laser Cladding Parameters

2.2. Phase and Microstructure Characterization

2.3. Microhardness and Cavitation Erosion Resistance Test

3. Results

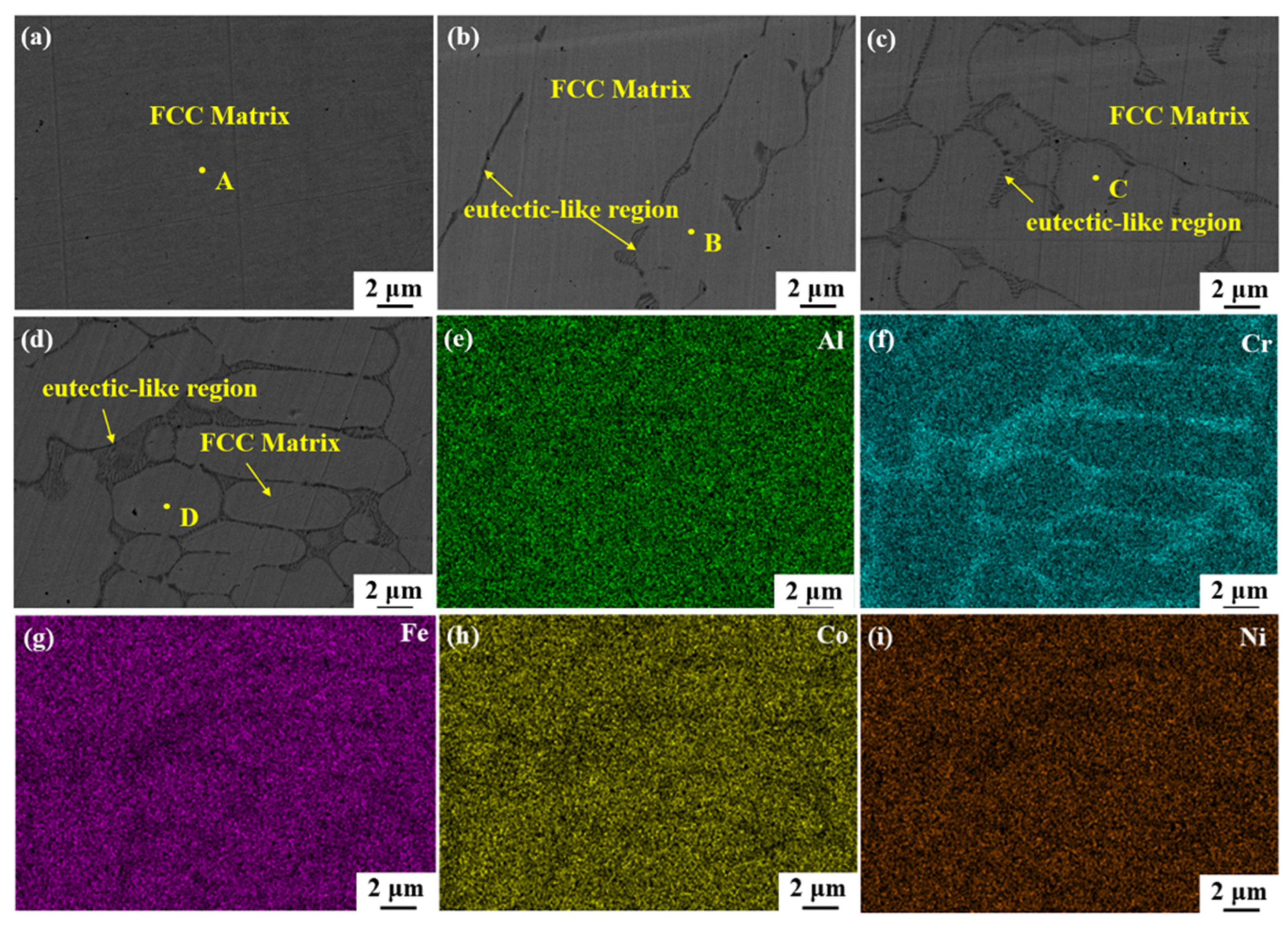

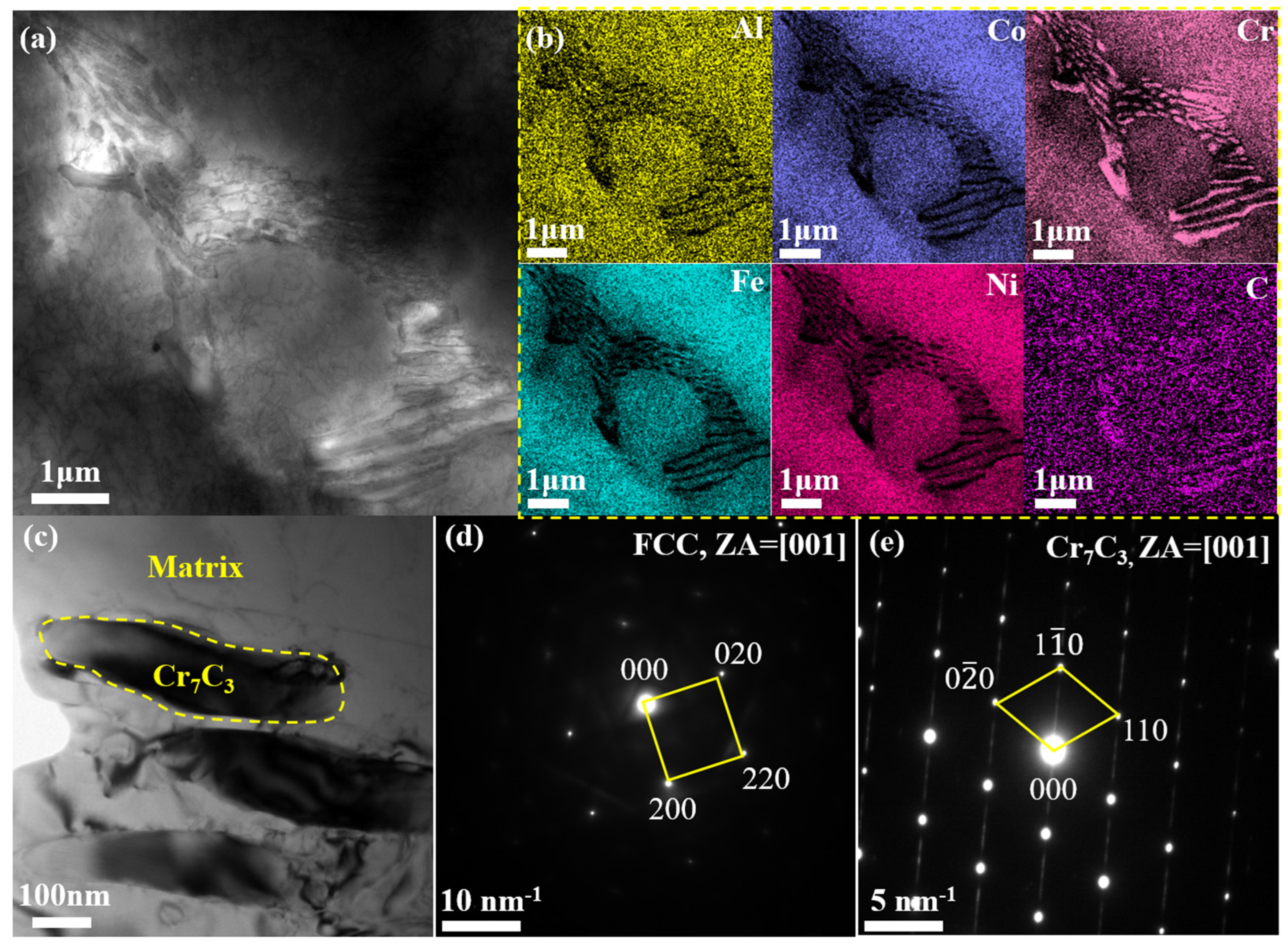

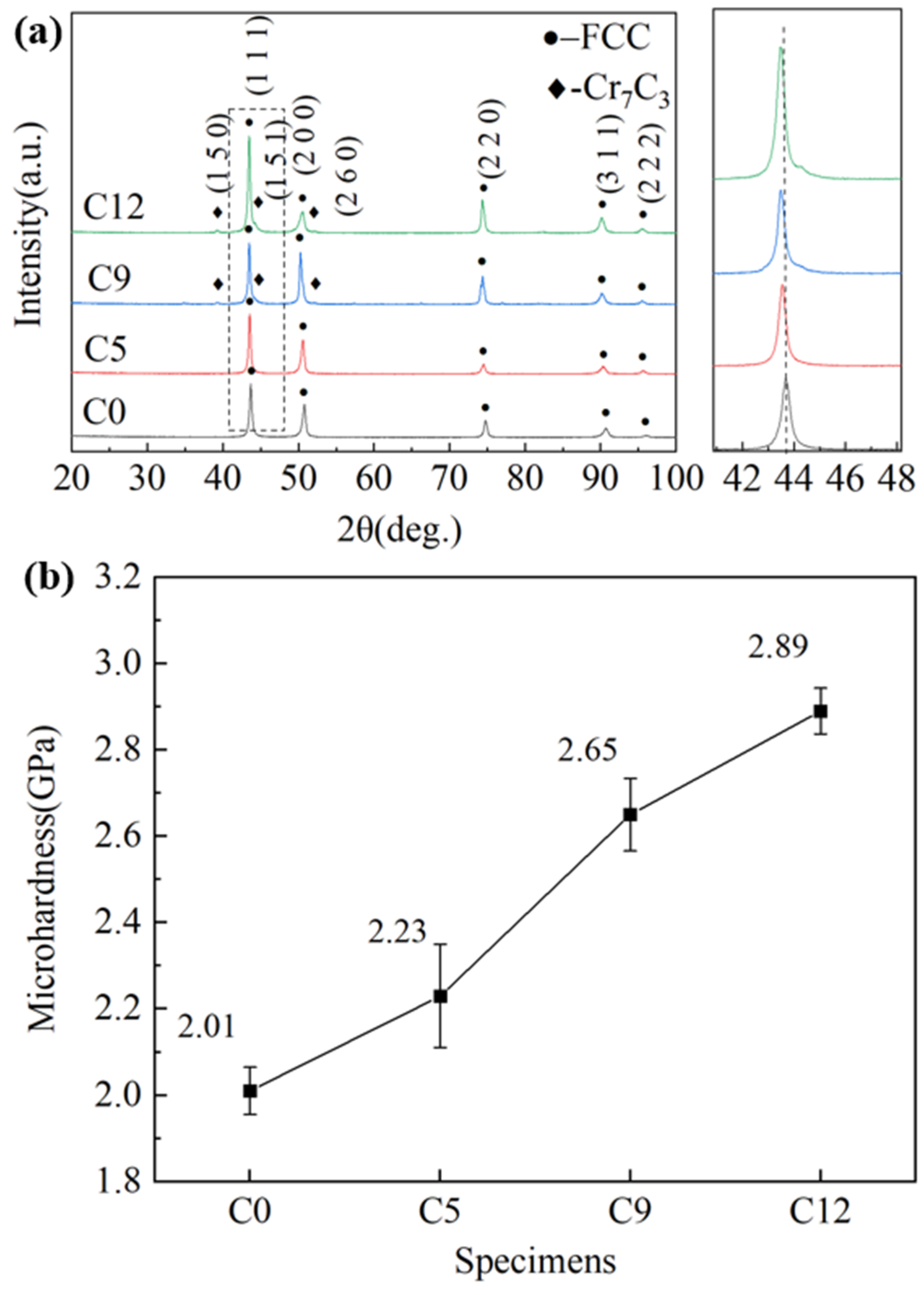

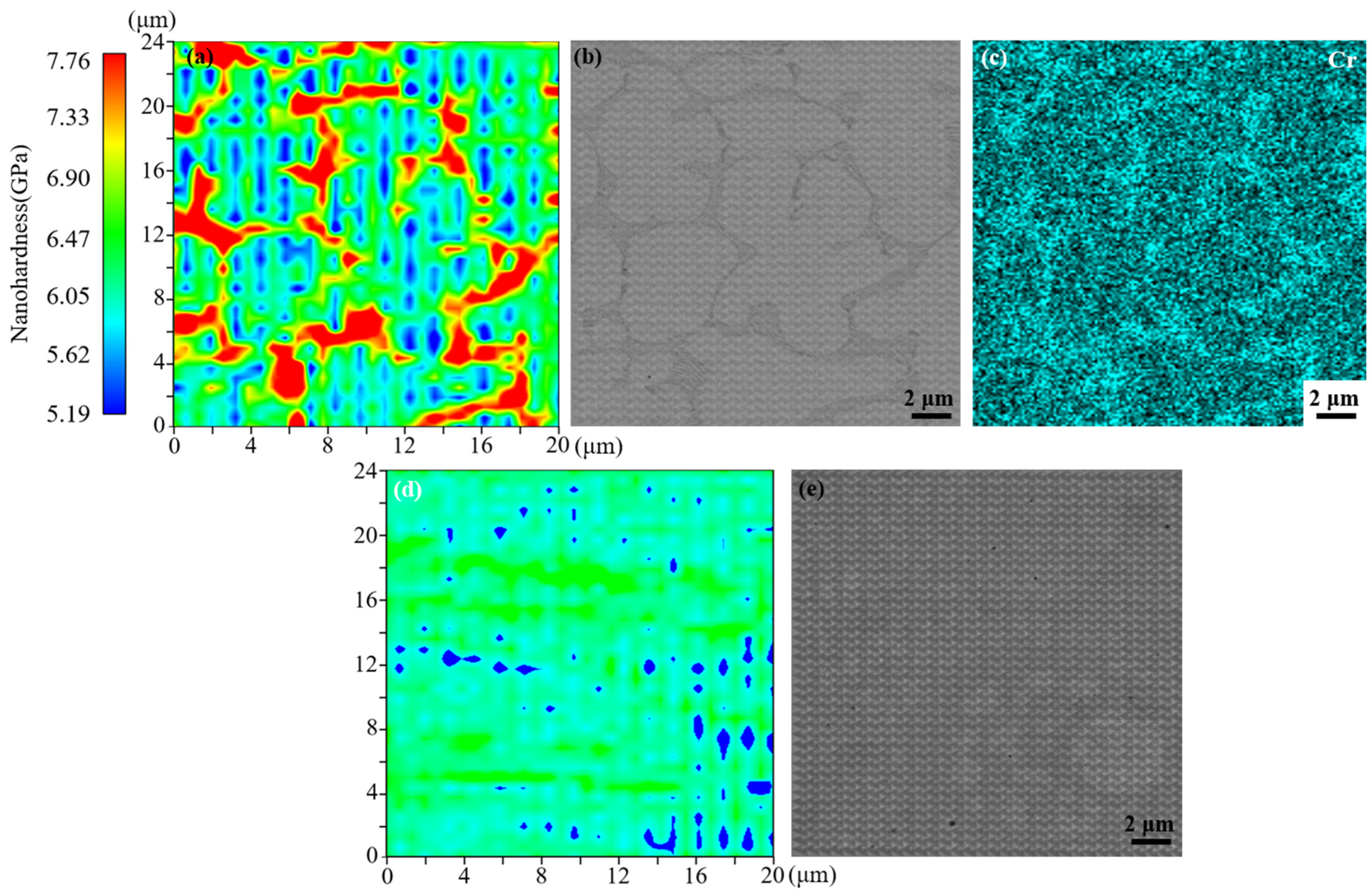

3.1. Microstructure Characterization

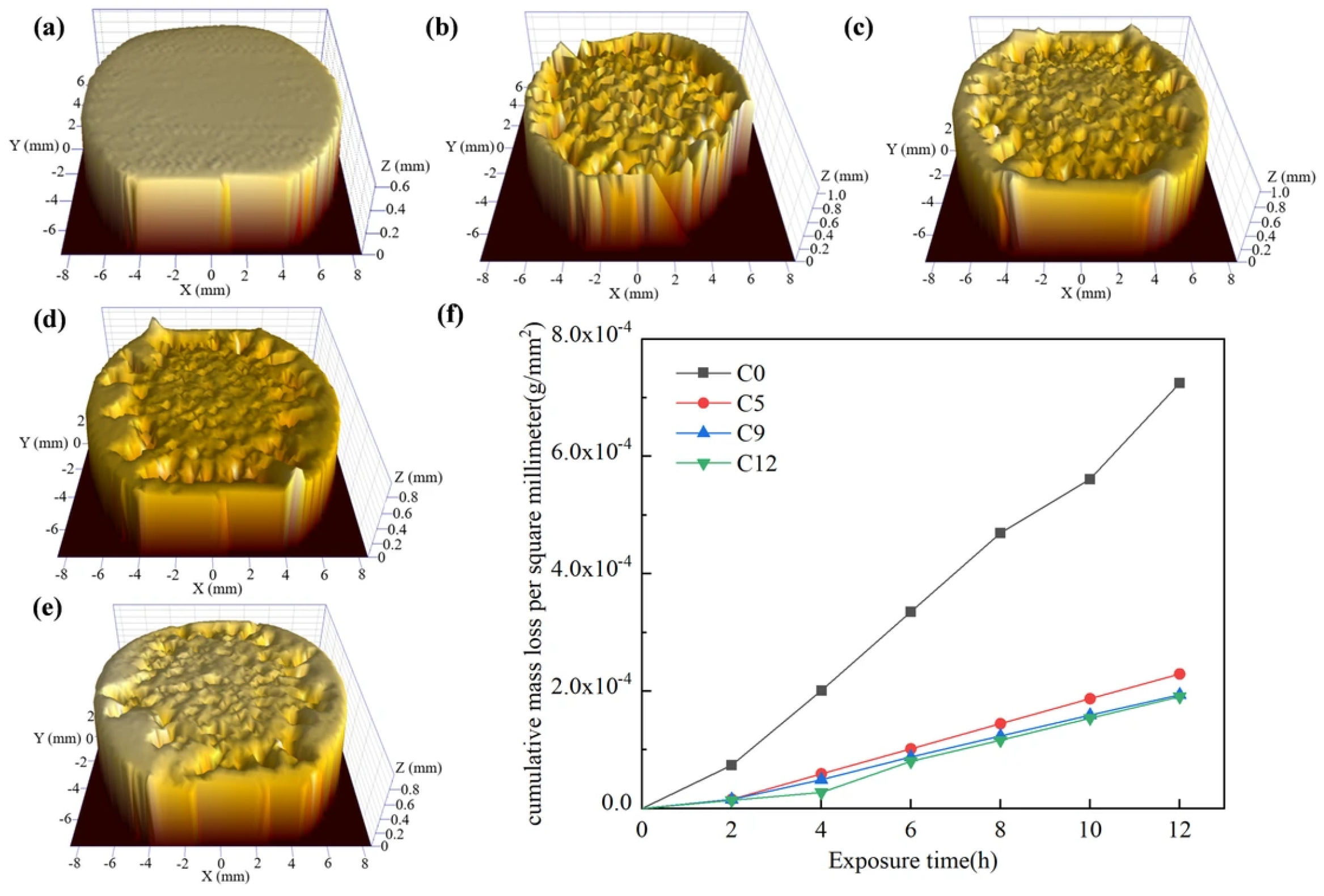

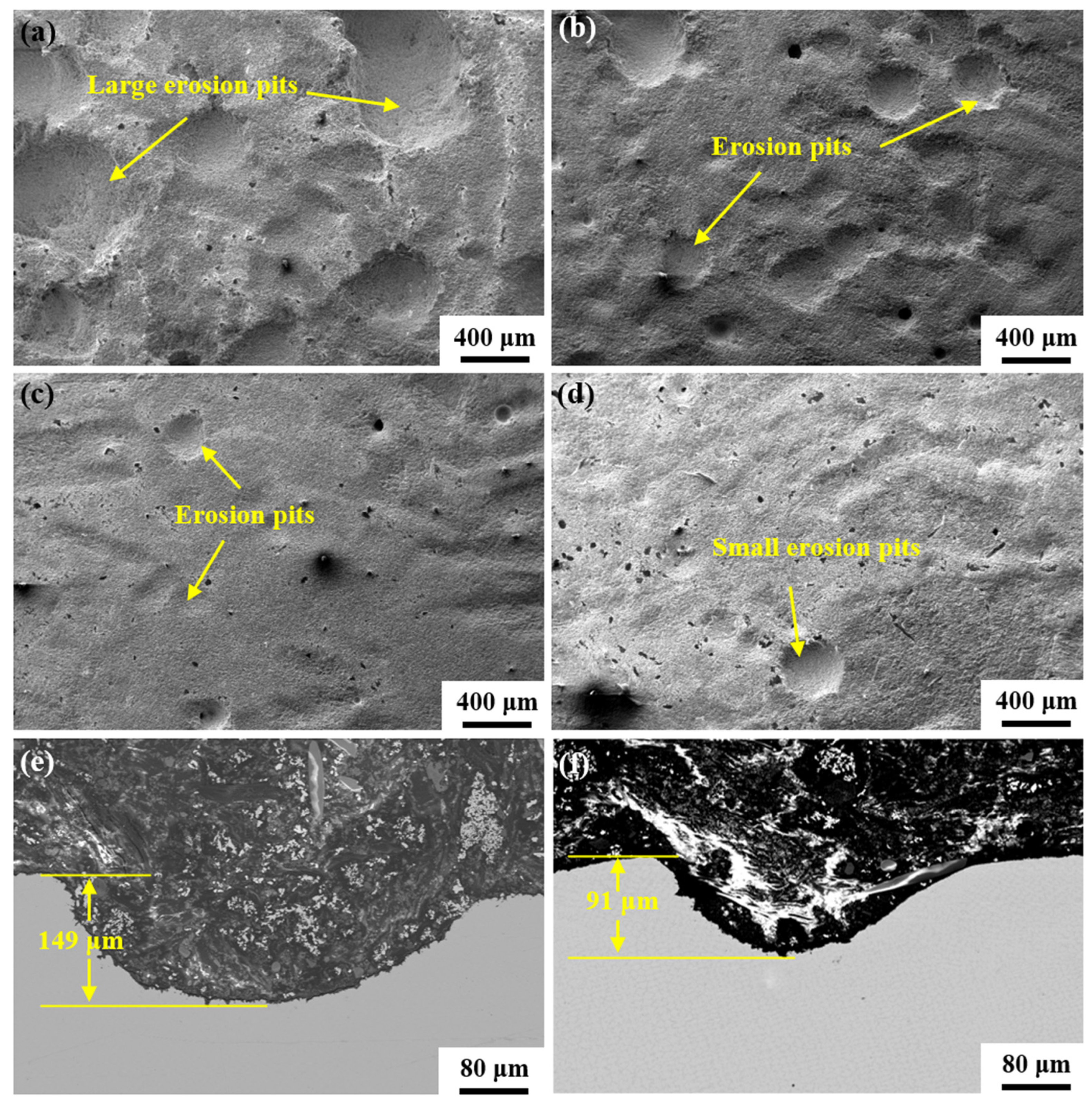

3.2. Cavitation Erosion Result

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Luo, X.; Ji, B.; Tsujimoto, Y. A Review of Cavitation in Hydraulic Machinery. J. Hydrodyn. 2016, 28, 335–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franc, J.-P.; Michel, J.-M. Cavitation Erosion Research in France: The State of the Art. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 1997, 2, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhou, H.; Wang, Y.; Song, Q.; Li, H.; Zheng, Z. Effect of Solution Treatment on Cavitation Erosion Behavior of High-Nitrogen Austenitic Stainless Steel. Wear 2019, 424–425, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krella, A.K. The Resistance of S235JR Steel to Cavitation Erosion. Wear 2020, 452, 203295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E, M.; Hu, H.X.; Guo, X.M.; Zheng, Y.G. Comparison of the Cavitation Erosion and Slurry Erosion Behavior of Cobalt-Based and Nickel-Based Coatings. Wear 2019, 428–429, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Wang, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, C.H.; Sun, X.Y.; Chen, H.T.; Bai, X.L.; Wu, C.L. Effect of Synergistic Cavitation Erosion-Corrosion on Cavitation Damage of CoCrFeNiMn High Entropy Alloy Layer by Laser Cladding. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 472, 129940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krella, A. The Influence of TiN Coatings Properties on Cavitation Erosion Resistance. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2009, 204, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Tian, Y.; Liu, X.; Yang, R.; Li, H.; Chen, X. Microstructure Evolution of the Laser Surface Melted WC-Ni Coatings Exposed to Cavitation Erosion. Tribol. Int. 2022, 173, 107615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Shi, W.; Huang, J. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of TiC/WC-Reinforced AlCoCrFeNi High-Entropy Alloys Prepared by Laser Cladding. Crystals 2024, 14, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Wu, Y.; Hong, S.; Cheng, J.; Qiao, L.; Cheng, J.; Zhu, S. Effect of WC-10Co on Cavitation Erosion Behaviors of AlCoCrFeNi Coatings Prepared by HVOF Spraying. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 15121–15128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.; Chang, J.; Wang, Y.; Ma, N.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, H.; Wang, M. Effect of ZrO2 Particles on the Microstructure and Ultrasonic Cavitation Properties of CoCrFeMnNi High-Entropy Alloy Composite Coatings. Coatings 2024, 14, 1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J. Friction–Wear Performances and Oxidation Behaviors of Ti3AlC2 Reinforced Co–Based Alloy Coatings by Laser Cladding. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 408, 126816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Fu, T.; Wang, P.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, W.; Su, F.; Li, G.; Xing, Z.; Ma, G. Microstructure and Properties of Plasma Sprayed Copper-Matrix Composite Coatings with Ti3SiC2 Addition. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 460, 129434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieseler, R.; Camargo, M.K.; Hopfeld, M.; Schmidt, U.; Bund, A.; Schaaf, P. Copper-MAX-Phase Composite Coatings Obtained by Electro-Co-Deposition: A Promising Material for Electrical Contacts. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2017, 321, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonov, D.; Gupta, S.; Palanisamy, T.; Barsoum, M.W. Effect of Applied Load and Surface Roughness on the Tribological Properties of Ni-Based Superalloys Versus Ta2AlC/Ag or Cr2AlC/Ag Composites. Tribol. Lett. 2009, 33, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W. A Review of Novel Ternary Nano-Layered MAX Phases Reinforced AZ91D Magnesium Composite. J. Magnes. Alloys 2022, 10, 1457–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C. Atomic Level Out-Diffusion and Interfacial Reactions of MAX Phases in Contact with Metals and Air. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 44, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W. Effects of A-Site Atoms in Ti2AlC and Ti3SiC2 MAX Phases Reinforced Mg Composites: Interfacial Structure and Mechanical Properties. Mater. Sci. 2021, 826, 141961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Li, D.Y. Effect of 211 MAX Phase Ti2AlC in Situ Formed TiCx on Properties of High Chromium White Iron. Mater. Lett. 2023, 352, 135112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Huang, Z.; Hu, W.; Li, X.; Yu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Dastan, D. In-Situ Hybrid Cr3C2 and Γ′-Ni3(Al, Cr) Strengthened Ni Matrix Composites: Microstructure and Enhanced Properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 820, 141524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Liu, J.; Xue, M.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Y.; Geng, K.; Dong, Y.; Yang, Y. Structure and Corrosion Behavior of FeCoCrNiMo High-Entropy Alloy Coatings Prepared by Mechanical Alloying and Plasma Spraying. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2024, 31, 2692–2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Hou, J.; Yang, H.; Tan, Y.; Wang, X.; Shi, X.; Guo, R.; Qiao, J. Tensile Strength Prediction of Dual-Phase Al0.6CoCrFeNi High-Entropy Alloys. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2020, 27, 1341–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Huang, K.; Zhang, B.; Xia, J.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, Y. Corrosion Engineering on AlCoCrFeNi High-Entropy Alloys toward Highly Efficient Electrocatalysts for the Oxygen Evolution of Alkaline Seawater. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2023, 30, 1922–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.; Stanford, N.; Hodgson, P.; Fabijanic, D.M. Tension/Compression Asymmetry in Additive Manufactured Face Centered Cubic High Entropy Alloy. Scr. Mater. 2017, 129, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Jing, C.; Feng, Y.; Wu, Z.; Lin, T.; Zhao, J. Phase Evolution and Properties of AlxCoCrFeNi High-Entropy Alloys Coatings by Laser Cladding. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 35, 105800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, Q.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Xu, S.; Yuan, Q.; Wen, H.; Xiao, T.; Liu, J. Phase Evolution and Mechanical Properties of AlxCoCrFeNi High-Entropy Alloys by Directed Energy Deposition. Mater. Charact. 2023, 204, 113217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, P.; Li, R.; Fan, Z.; Cao, P.; Zheng, D.; Wang, M.; Deng, C.; Yuan, T. Inhibiting Cracking and Improving Strength for Additive Manufactured Al CoCrFeNi High Entropy Alloy via Changing Crystal Structure from BCC-to-FCC. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 71, 103584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Z.; Liu, C.; Xie, D.; Feng, R.; Yu, D.; Chen, Y.; An, K.; Gao, Y.; Wang, H.; Liaw, P.K. Low Cycle Fatigue Performances of Al0.3CoCrFeNi High Entropy Alloys: In Situ Neutron Diffraction Studies on the Precipitation Effects. Intermetallics 2024, 168, 108241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM G32-16; Standard Test Method for Cavitation Erosion Using Vibratory Apparatus. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- Franc, J.-P.; Michel, J.-M. Fundamentals of Cavitation; Fluid Mechanics and Its Applications; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2005; Volume 76, ISBN 978-1-4020-2232-6. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Yang, R.; Gu, Z.; Zhao, H.; Wu, X.; Dehaghani, S.T.; Chen, H.; Liu, X.; Xiao, T.; McDonald, A.; et al. Ultrahigh Cavitation Erosion Resistant Metal-Matrix Composites with Biomimetic Hierarchical Structure. Compos. Part B Eng. 2022, 234, 109730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.-T.; Wang, R.-Q.; Ke, L.-C.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Z.-M.; Zhang, C.-W.; Yu, Y. Morphology Distribution and Corrosion Resistance of In-Situ TiC/CoCrFeNi High-Entropy Alloy Coating. Mater. Charact. 2025, 224, 115078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Wt.% | Al | Co | Cr | Fe | Ni | Mo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 00Cr13Ni4Mo | 0 | 0 | 13.5 | Bal. | 4.5 | 2.0 |

| Al0.3CoCrFeNi | 3.48 | 25.34 | 22.36 | 24.02 | 25.24 | 0 |

| Wt.% | Al | Co | Cr | Fe | Ni |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point A | 3.20 | 24.3 | 22.80 | 24.80 | 24.90 |

| Point B | 3.50 | 22.19 | 22.64 | 25.13 | 26.54 |

| Point C | 3.87 | 19.45 | 25.76 | 25.62 | 25.30 |

| Point D | 4.15 | 19.13 | 31.10 | 26.76 | 18.88 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, L.; Ma, Y.; Yu, W.; Liu, J.; Du, B.; Ao, X. High Cavitation Resistance Performance of Al0.3CoCrFeNi Coating Reinforced by Ternary Cr2AlC Compound. Coatings 2025, 15, 1469. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121469

Zhang L, Ma Y, Yu W, Liu J, Du B, Ao X. High Cavitation Resistance Performance of Al0.3CoCrFeNi Coating Reinforced by Ternary Cr2AlC Compound. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1469. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121469

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Lin, Yihu Ma, Wenbo Yu, Jianhua Liu, Bing Du, and Xiaohui Ao. 2025. "High Cavitation Resistance Performance of Al0.3CoCrFeNi Coating Reinforced by Ternary Cr2AlC Compound" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1469. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121469

APA StyleZhang, L., Ma, Y., Yu, W., Liu, J., Du, B., & Ao, X. (2025). High Cavitation Resistance Performance of Al0.3CoCrFeNi Coating Reinforced by Ternary Cr2AlC Compound. Coatings, 15(12), 1469. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121469