Recent Advances in pH-Responsive Coatings for Orthopedic and Dental Implants: Tackling Infection and Inflammation and Enhancing Bone Regeneration

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. pH-Sensitive Materials

2.1. Bio-Polymers

2.1.1. Chitosan

2.1.2. Silk Fibrin

2.1.3. ECM-Based Composites

2.1.4. Other Bio-Polymers

2.2. Synthetic Polymers

2.2.1. pH-Sensitive Cationic Polymers

2.2.2. pH-Sensitive Anionic Polymers

2.2.3. pH-Sensitive Polyphenols

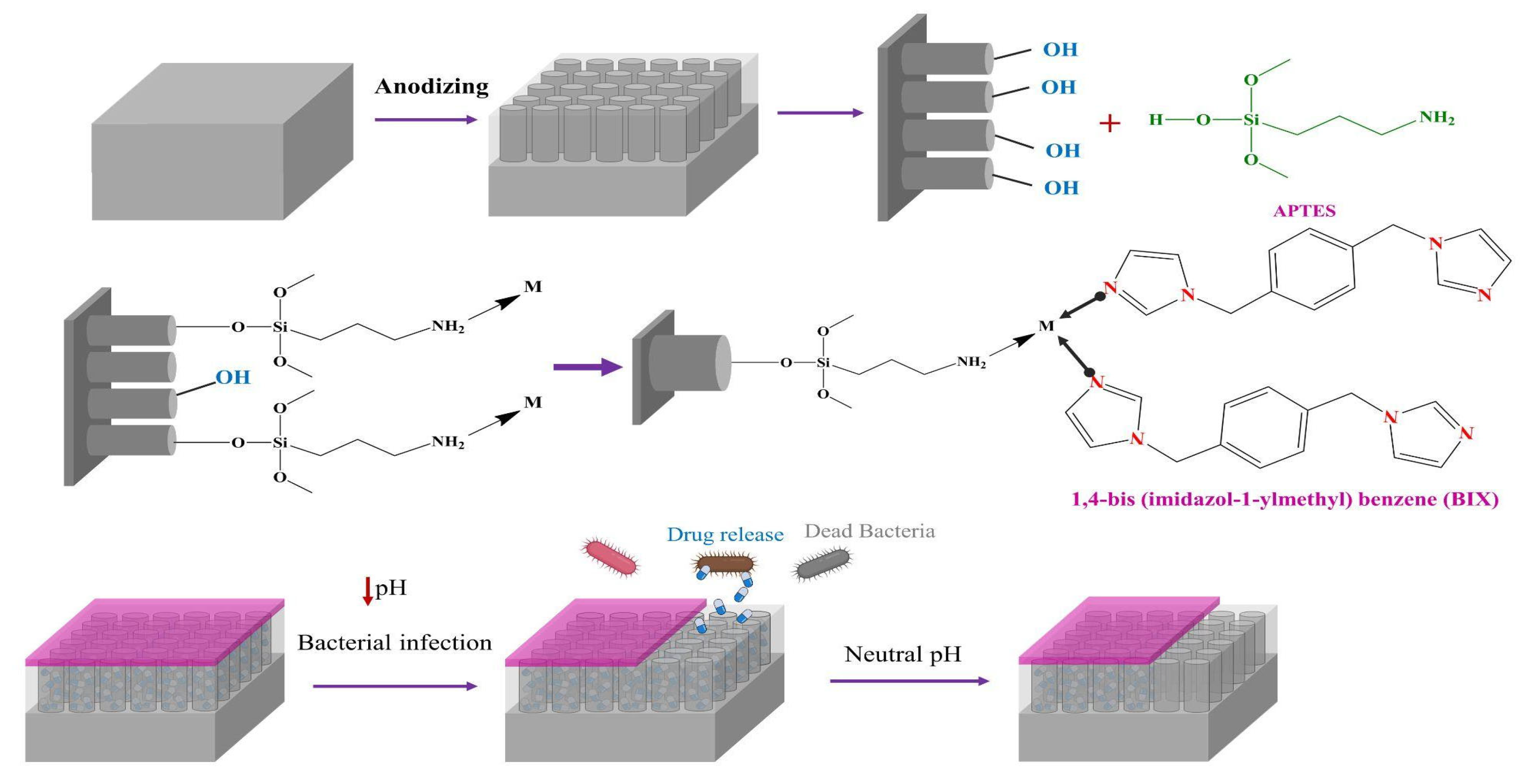

2.3. Porous Coatings

2.3.1. Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles

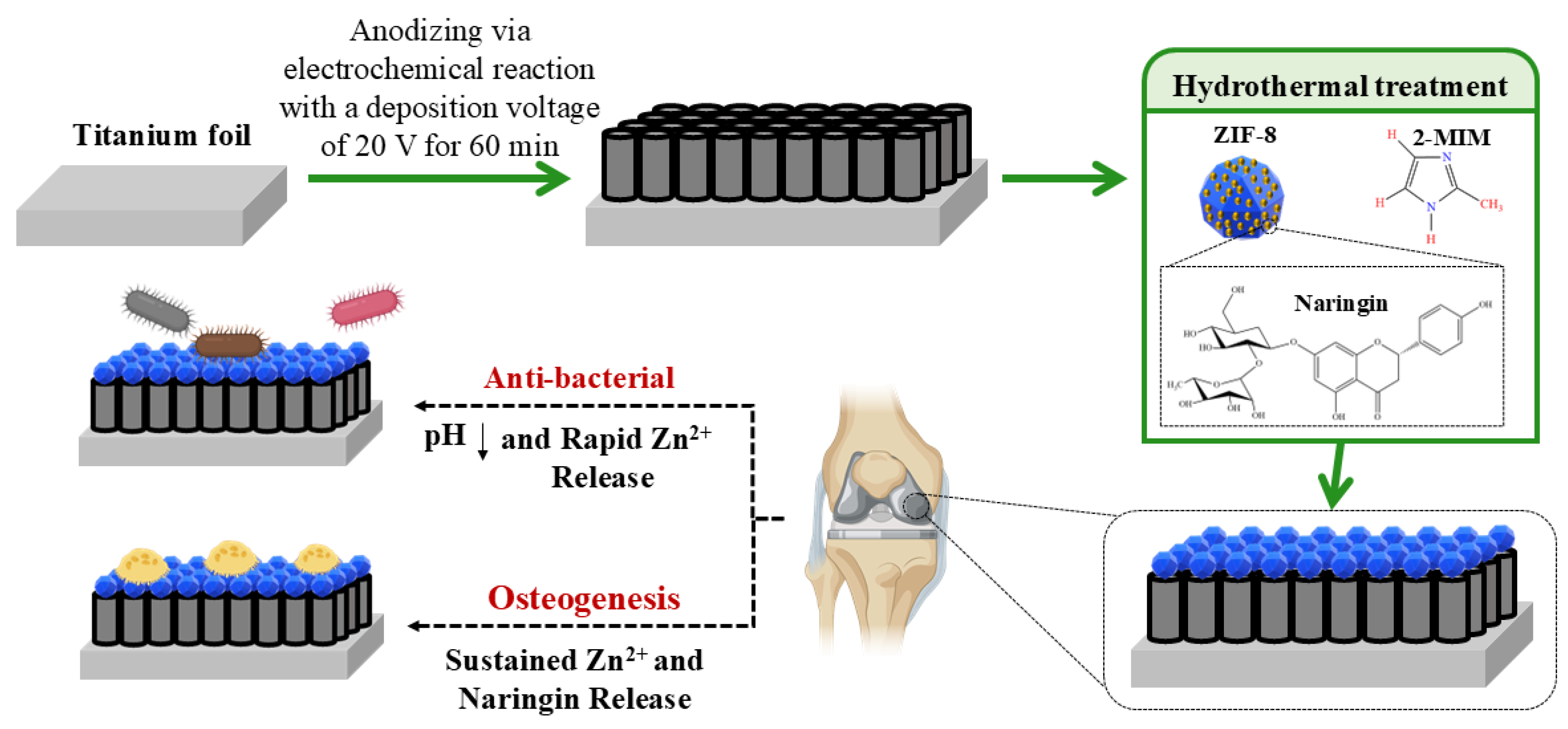

2.3.2. Metal-Organic-Frameworks

2.4. pH-Sensitive Linkers

3. Current Challenges and Future Outlook

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| PLGA | poly-lactic-co-glycolic acid |

| MSN | mesoporous silica nanoparticle |

| ALP | alkaline phosphatase |

| PDA | polydopamine |

| LbL | layer-by-layer |

| PEEK | sulfonated polyether-ether-ketone |

| DOX | doxorubicin hydrochloride |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| BMP-2 | Bone Morphogenetic Protein 2 |

| OPN | Osteopontin |

| TNT | titania nanotube |

| siRNA | small interfering RNA |

| AgNP | silver nanoparticle |

| SF | silk fibroin |

| Col I | Collagen 1 |

| OCN | osteocalcin |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| PEI | polyethyleneimine |

| PDMAEMA | Poly(N, N-dimethylaminoethyl methacrylate) |

| P(NIPAM-co-MAA) | Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide-co-methacrylic acid) |

| MWCNT | multi-walled carbon nanotubes |

| PLL | Poly-L-lysine |

| QA | quaternary ammonium |

| PLH | Poly L-Histidine |

| PMAA | poly(methacrylic acid) |

| OGP | osteogenic growth peptide |

References

- Ackerman, I.N.; Bohensky, M.A.; de Steiger, R.; Brand, C.A.; Eskelinen, A.; Fenstad, A.M.; Furnes, O.; Garellick, G.; Graves, S.E.; Haapakoski, J.; et al. Substantial rise in the lifetime risk of primary total knee replacement surgery for osteoarthritis from 2003 to 2013: An international, population-level analysis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2017, 25, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LROI. Online LROI Annual Report 2022; Dutch Arthroplasty Register (LROI): s-Hertogenbosch, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Arciola, C.R.; Campoccia, D.; Montanaro, L. Implant infections: Adhesion, biofilm formation and immune evasion. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciofu, O.; Moser, C.; Jensen, P.Ø.; Høiby, N. Tolerance and resistance of microbial biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 621–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayana, S.V.V.S.; Srihari, P.S.V.V. Biofilm Resistant Surfaces and Coatings on Implants: A Review. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 18, 4847–4853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Chu, P.K.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Z. Antibacterial coatings on titanium implants. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2009, 91B, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.D.; Buckle, C.L. How does aseptic loosening occur and how can we prevent it? Orthop. Trauma 2020, 34, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, N.A.; Sussman, E.M.; Stegemann, J.P. Aseptic and septic prosthetic joint loosening: Impact of biomaterial wear on immune cell function, inflammation, and infection. Biomaterials 2021, 278, 121127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.D.R.; Barreto Arantes, M.; Menezes de Faria Pereira, S.; Leandro da Cruz, L.; de Souza Passos, M.; Pereira de Moraes, L.; Vieira, I.J.C.; Barros de Oliveira, D. Plants as Sources of Anti-Inflammatory Agents. Molecules 2020, 25, 3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnicer-Lombarte, A.; Chen, S.-T.; Malliaras, G.G.; Barone, D.G. Foreign Body Reaction to Implanted Biomaterials and Its Impact in Nerve Neuroprosthetics. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 622524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziats, N.P.; Miller, K.M.; Anderson, J.M. In vitro and in vivo interactions of cells with biomaterials. Biomaterials 1988, 9, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebaudy, E.; Fournel, S.; Lavalle, P.; Vrana, N.E.; Gribova, V. Recent Advances in Antiinflammatory Material Design. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2021, 10, 2001373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Ao, H.Y.; Yang, S.B.; Wang, Y.G.; Lin, W.T.; Yu, Z.F.; Tang, T.T. In vivo evaluation of the anti-infection potential of gentamicin-loaded nanotubes on titania implants. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016, 11, 2223–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Zhou, P.; Wang, L.; Xiong, X.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, Y.; Wei, S. Antibiotic-decorated titanium with enhanced antibacterial activity through adhesive polydopamine for dental/bone implant. J. R. Soc. Interface 2014, 11, 20140169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zhou, J.; Qian, Y.; Zhao, L. Antibacterial coatings on orthopedic implants. Mater. Today Bio 2023, 19, 100586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croes, M.; Boot, W.; Kruyt, M.C.; Weinans, H.; Pouran, B.; van der Helm, Y.J.M.; Gawlitta, D.; Vogely, H.C.; Alblas, J.; Dhert, W.J.A.; et al. Inflammation-Induced Osteogenesis in a Rabbit Tibia Model. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2017, 23, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roupie, C.; Labat, B.; Morin-Grognet, S.; Echalard, A.; Ladam, G.; Thébault, P. Dual-functional antibacterial and osteogenic nisin-based layer-by-layer coatings. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 131, 112479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, B.; Lin, C.; He, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Chen, M.; Xu, K.; Li, K.; Guo, A.; Cai, K.; Chen, L. Osteoimmunomodulation mediating improved osteointegration by OGP-loaded cobalt-metal organic framework on titanium implants with antibacterial property. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 423, 130176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djošić, M.; Janković, A.; Mišković-Stanković, V. Electrophoretic Deposition of Biocompatible and Bioactive Hydroxyapatite-Based Coatings on Titanium. Materials 2021, 14, 5391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.; Lammers, T.; ten Hagen, T.L.M. Temperature-sensitive polymers to promote heat-triggered drug release from liposomes: Towards bypassing EPR. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2022, 189, 114503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Zeng, B.; Yang, W. Light responsive hydrogels for controlled drug delivery. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 1075670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.F.; Jang, B.; Issadore, D.; Tsourkas, A. Use of magnetic fields and nanoparticles to trigger drug release and improve tumor targeting. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2019, 11, e1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin Low, S.; Nong Lim, C.; Yew, M.; Siong Chai, W.; Low, L.E.; Manickam, S.; Ti Tey, B.; Show, P.L. Recent ultrasound advancements for the manipulation of nanobiomaterials and nanoformulations for drug delivery. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 80, 105805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.J.; Björnmalm, M.; Caruso, F. Technology-driven layer-by-layer assembly of nanofilms. Science 2015, 348, aaa2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizwan, M.; Yahya, R.; Hassan, A.; Yar, M.; Azzahari, A.D.; Selvanathan, V.; Sonsudin, F.; Abouloula, C.N. pH Sensitive Hydrogels in Drug Delivery: Brief History, Properties, Swelling, and Release Mechanism, Material Selection and Applications. Polymers 2017, 9, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmaljohann, D. Thermo- and pH-responsive polymers in drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2006, 58, 1655–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiraide, S.; Nishimoto, K.; Watanabe, S. Controlling the steepness of gate-opening behavior on elastic layer-structured metal–organic framework-11 via solvent-mediated phase transformation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 18193–18203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialas, F.; Reichinger, D.; Becker, C.F.W. Biomimetic and biopolymer-based enzyme encapsulation. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2021, 150, 109864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Han, H.; Ye, T.T.; Li, F.X.; Wang, X.L.; Yu, J.Y.; Wu, D.Q. Biodegradable and pH Sensitive Peptide Based Hydrogel as Controlled Release System for Antibacterial Wound Dressing Application. Molecules 2018, 23, 3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakides, T.R.; Cheung, C.Y.; Murthy, N.; Bornstein, P.; Stayton, P.S.; Hoffman, A.S. pH-sensitive polymers that enhance intracellular drug delivery in vivo. J Control Release 2002, 78, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Nayak, P. pH-responsive polymers for drug delivery: Trends and opportunities. J. Polym. Sci. 2023, 61, 2828–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, J.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, H.; Bian, H.; Pan, Y.; Sun, J.; Han, W. Application of Protein-Based Films and Coatings for Food Packaging: A Review. Polymers 2019, 11, 2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, B.; Chatha, S.A.S.; Hussain, A.I.; Zia, K.M.; Akhtar, N. Recent advances on polysaccharides, lipids and protein based edible films and coatings: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 109, 1095–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaewprachu, P.; Osako, K.; Benjakul, S.; Tongdeesoontorn, W.; Rawdkuen, S. Biodegradable Protein-based Films and Their Properties: A Comparative Study. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2016, 29, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, N.; Rana, D.; Salave, S.; Gupta, R.; Patel, P.; Karunakaran, B.; Sharma, A.; Giri, J.; Benival, D.; Kommineni, N. Chitosan: A Potential Biopolymer in Drug Delivery and Biomedical Applications. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalliola, S.; Repo, E.; Srivastava, V.; Zhao, F.; Heiskanen, J.P.; Sirviö, J.A.; Liimatainen, H.; Sillanpää, M. Carboxymethyl Chitosan and Its Hydrophobically Modified Derivative as pH-Switchable Emulsifiers. Langmuir 2018, 34, 2800–2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Tachibana, T.; Wadamori, H.; Yamana, K.; Kawasaki, R.; Kawamura, S.; Isozaki, H.; Sakuragi, M.; Akiba, I.; Yabuki, A. Drug-Loaded Biocompatible Chitosan Polymeric Films with Both Stretchability and Controlled Release for Drug Delivery. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 1282–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Gómez, C.P.; Cecilia, J.A. Chitosan: A Natural Biopolymer with a Wide and Varied Range of Applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghattas, M.; Dwivedi, G.; Chevrier, A.; Horn-Bourque, D.; Alameh, M.G.; Lavertu, M. Chitosan immunomodulation: Insights into mechanisms of action on immune cells and signaling pathways. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 896–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Jiang, F.; Cheng, K.; Qi, Z.; Yadavalli, V.K.; Lu, S. Synthesis of pH and Glucose Responsive Silk Fibroin Hydrogels. Int J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makadia, H.K.; Siegel, S.J. Poly Lactic-co-Glycolic Acid (PLGA) as Biodegradable Controlled Drug Delivery Carrier. Polymers 2011, 3, 1377–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porgham Daryasari, M.; Dusti Telgerd, M.; Hossein Karami, M.; Zandi-Karimi, A.; Akbarijavar, H.; Khoobi, M.; Seyedjafari, E.; Birhanu, G.; Khosravian, P.; SadatMahdavi, F. Poly-l-lactic acid scaffold incorporated chitosan-coated mesoporous silica nanoparticles as pH-sensitive composite for enhanced osteogenic differentiation of human adipose tissue stem cells by dexamethasone delivery. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2019, 47, 4020–4029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Neoh, K.G.; Kang, E.-T. Bifunctional coating based on carboxymethyl chitosan with stable conjugated alkaline phosphatase for inhibiting bacterial adhesion and promoting osteogenic differentiation on titanium. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 360, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, Í.; Faria, J.; Marques, A.; Ribeiro, I.A.C.; Baleizão, C.; Bettencourt, A.; Ferreira, I.M.M.; Baptista, A.C. Drug Delivery from PCL/Chitosan Multilayer Coatings for Metallic Implants. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 23096–23106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, M.; Zhu, C.; Sun, D.; Liu, Z.; Du, M.; Huang, Y.; Huang, L.; Wang, J.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.; et al. Layer-by-layer assembled black phosphorus/chitosan composite coating for multi-functional PEEK bone scaffold. Compos. Part B Eng. 2022, 246, 110266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Q.; Zhu, J.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, H.; Qian, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, C. A dual-delivery system of pH-responsive chitosan-functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles bearing BMP-2 and dexamethasone for enhanced bone regeneration. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3, 2056–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Shen, P.; Gao, B.; Liu, X.; Kong, X.; Zhang, S.; Wu, J. Fabrication and in vitro biological activity of functional pH-sensitive double-layered nanoparticles for dental implant application. J. Biomater. Appl. 2020, 34, 1409–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, B.; Deng, Y.; Song, L.; Ma, W.; Qian, Y.; Lin, C.; Yuan, Z.; Lu, L.; Chen, M.; Yang, X.; et al. BMP2-loaded titania nanotubes coating with pH-responsive multilayers for bacterial infections inhibition and osteogenic activity improvement. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2019, 177, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Zhao, L.; Fang, K.; Chang, B.; Zhang, Y. Biofunctionalization of titanium implant with chitosan/siRNA complex through loading-controllable and time-saving cathodic electrodeposition. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3, 8567–8576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Li, Y.; Yan, J.; Xiong, P.; Li, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Zheng, Y. Construction of Self-defensive Antibacterial and Osteogenic AgNPs/Gentamicin Coatings with Chitosan as Nanovalves for Controlled release. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Yan, R.; Chen, S.; Hao, X.; Dou, W.; Liu, H.; Guo, Z.; Kilula, D.; Seok, I. Narrow pH response multilayer films with controlled release of ibuprofen on magnesium alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2021, 118, 111414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, C.; Jiajia, J.; Meng, L.; Hongfei, Q.; Xianglong, W.; Tingli, L. Electrophoretic deposition of GHK-Cu loaded MSN-chitosan coatings with pH-responsive release of copper and its bioactivity. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 104, 109746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawłowski, Ł.; Bartmański, M.; Strugała, G.; Mielewczyk-Gryń, A.; Jażdżewska, M.; Zieliński, A. Electrophoretic Deposition and Characterization of Chitosan/Eudragit E 100 Coatings on Titanium Substrate. Coatings 2020, 10, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerdelmann, G.; Kozlova, D.; Epple, M. A pH-sensitive poly(methyl methacrylate) copolymer for efficient drug and gene delivery across the cell membrane. J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 7123–7131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leopold, C.S.; Eikeler, D. Eudragit E as coating material for the pH-controlled drug release in the topical treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). J. Drug Target. 1998, 6, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Xia, D.; Zhou, W.; Li, Y.; Xiong, P.; Li, Q.; Wang, P.; Li, M.; Zheng, Y.; Cheng, Y. pH-responsive silk fibroin-based CuO/Ag micro/nano coating endows polyetheretherketone with synergistic antibacterial ability, osteogenesis, and angiogenesis. Acta Biomater. 2020, 115, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, P.; Yan, J.; Wang, P.; Jia, Z.; Zhou, W.; Yuan, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, D.; et al. A pH-sensitive self-healing coating for biodegradable magnesium implants. Acta Biomater. 2019, 98, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Bai, T.; Wang, L.; Cheng, Y.; Xia, D.; Yu, S.; Zheng, Y. Biomimetic AgNPs@antimicrobial peptide/silk fibroin coating for infection-trigger antibacterial capability and enhanced osseointegration. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 20, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Xue, Y.; Zhou, J.; Han, Y. pH-Responsive ECM Coating on Ti Implants for Antibiosis in Reinfected Models. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2022, 5, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, B.; Qiu, P.; Xia, C.; Cai, D.; Zhao, C.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, S.; Cheng, H.; Tang, Z.; et al. Extracellular matrix scaffold crosslinked with vancomycin for multifunctional antibacterial bone infection therapy. Biomaterials 2021, 268, 120603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Xu, F. A composite coating of calcium alginate and gelatin particles on Ti6Al4V implant for the delivery of water soluble drug. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2009, 89, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farshbaf, M.; Davaran, S.; Zarebkohan, A.; Annabi, N.; Akbarzadeh, A.; Salehi, R. Significant role of cationic polymers in drug delivery systems. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018, 46, 1872–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Ribeiro, A.M.; de Melo Carrasco, L.D. Cationic antimicrobial polymers and their assemblies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 9906–9946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deen, G.R.; Loh, X.J. Stimuli-Responsive Cationic Hydrogels in Drug Delivery Applications. Gels 2018, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawant, R.R.; Sriraman, S.K.; Navarro, G.; Biswas, S.; Dalvi, R.A.; Torchilin, V.P. Polyethyleneimine-lipid conjugate-based pH-sensitive micellar carrier for gene delivery. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 3942–3951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlsson, J.; Rhodes, K.R.; Green, J.J.; Tzeng, S.Y. Poly(beta-amino ester)s as gene delivery vehicles: Challenges and opportunities. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2020, 17, 1395–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stawski, D. Poly(N,N-dimethylaminoethyl methacrylate) as a bioactive polyelectrolyte-production and properties. R Soc. Open Sci. 2023, 10, 230188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, A.J.T.; Mishra, A.; Park, I.; Kim, Y.-J.; Park, W.-T.; Yoon, Y.-J. Polymeric Biomaterials for Medical Implants and Devices. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 2, 454–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Moro, M.; Jenczyk, J.; Giussi, J.M.; Jurga, S.; Moya, S.E. Kinetics of the thermal response of poly(N-isopropylacrylamide co methacrylic acid) hydrogel microparticles under different environmental stimuli: A time-lapse NMR study. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 580, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geuli, O.; Metoki-Shlubsky, N.; Eliaz, N.; Mandler, D. Electrochemically Driven Hydroxyapatite Nanoparticles Coating of Medical Implants. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 8003–8010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Loh, K.J. Noncontact Electrical Permittivity Mapping and pH-Sensitive Films for Osseointegrated Prosthesis and Infection Monitoring. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2017, 36, 2193–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Avila, E.D.; Castro, A.G.B.; Tagit, O.; Krom, B.P.; Löwik, D.; van Well, A.A.; Bannenberg, L.J.; Vergani, C.E.; van den Beucken, J.J.J.P. Anti-bacterial efficacy via drug-delivery system from layer-by-layer coating for percutaneous dental implant components. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 488, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, C.M.; Lambrechts, P.; Quirynen, M. Comparison of surface roughness of oral hard materials to the threshold surface roughness for bacterial plaque retention: A review of the literature. Dent. Mater. 1997, 13, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollen, C.M.; Papaioanno, W.; Van Eldere, J.; Schepers, E.; Quirynen, M.; van Steenberghe, D. The influence of abutment surface roughness on plaque accumulation and peri-implant mucositis. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 1996, 7, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.; Chen, X.; Chen, T.; Ding, C.; Wu, W.; Li, J. Substrate-anchored and degradation-sensitive anti-inflammatory coatings for implant materials. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmatpour, H.; Haddadi-Asl, V.; Roghani-Mamaqani, H. Synthesis of pH-sensitive poly (N,N-dimethylaminoethyl methacrylate)-grafted halloysite nanotubes for adsorption and controlled release of DPH and DS drugs. Polymer 2015, 65, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Hu, Q.; Wei, Y.; Meng, W.; Wang, R.; Liu, J.; Nie, Y.; Luo, R.; Wang, Y.; Shen, B. Surface modification of titanium implants by pH-Responsive coating designed for Self-Adaptive antibacterial and promoted osseointegration. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 435, 134802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smetana, K., Jr.; Vacík, J. Anionic polymers for implantation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1997, 831, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Ito, S.; Fujiwara, M.; Komatsu, N. Probing the Role of Charged Functional Groups on Nanoparticles Grafted with Polyglycerol in Protein Adsorption and Cellular Uptake. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2111077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvi, C.; Lyu, X.; Peterson, A.M. Effect of Assembly pH on Polyelectrolyte Multilayer Surface Properties and BMP-2 Release. Biomacromolecules 2016, 17, 1949–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, A.M.; Möhwald, H.; Shchukin, D.G. pH-controlled release of proteins from polyelectrolyte-modified anodized titanium surfaces for implant applications. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 3120–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onat, B.; Bütün, V.; Banerjee, S.; Erel-Goktepe, I. Bacterial anti-adhesive and pH-induced antibacterial agent releasing ultra-thin films of zwitterionic copolymer micelles. Acta Biomater. 2016, 40, 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Q.; Du, Y.; Bai, Y.; Xing, D.; Wu, C.; Li, K.; Lang, S.; Liu, X.; Liu, G. Smart zwitterionic coatings with precise pH-responsive antibacterial functions for bone implants to combat bacterial infections. Biomater. Sci. 2024, 12, 4471–4482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ejima, H.; Richardson, J.J.; Liang, K.; Best, J.P.; van Koeverden, M.P.; Such, G.K.; Cui, J.; Caruso, F. One-step assembly of coordination complexes for versatile film and particle engineering. Science 2013, 341, 154–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Lin, Z.; Ju, Y.; Rahim, M.A.; Richardson, J.J.; Caruso, F. Polyphenol-Mediated Assembly for Particle Engineering. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 1269–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, I.; Pangule, R.C.; Kane, R.S. Antifouling coatings: Recent developments in the design of surfaces that prevent fouling by proteins, bacteria, and marine organisms. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 690–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ai, K.; Lu, L. Polydopamine and its derivative materials: Synthesis and promising applications in energy, environmental, and biomedical fields. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 5057–5115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullotti, E.; Park, J.; Yeo, Y. Polydopamine-based surface modification for the development of peritumorally activatable nanoparticles. Pharm. Res. 2013, 30, 1956–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.S.; Hlady, V. The desorption of ribonuclease A from charge density gradient surfaces studied by spatially-resolved total internal reflection fluorescence. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 1995, 4, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Deng, Y.; Shi, X.; Chen, Y.; Yang, W.; Ma, Y.; Shi, X.-L.; Song, P.; Dargusch, M.S.; Chen, Z.-G. Bacteria-Triggered pH-Responsive Osteopotentiating Coating on 3D-Printed Polyetheretherketone Scaffolds for Infective Bone Defect Repair. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 12123–12135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Chai, Y.; Huang, K.; Wei, X.; Mei, Z.; Wu, X.; Dai, H. Vancomycin Hydrochloride Loaded Hydroxyapatite Mesoporous Microspheres with Micro/Nano Surface Structure to Increase Osteogenic Differentiation and Antibacterial Ability. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2021, 17, 1668–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, H.Y.; Kim, K.R.; Lee, J.B.; Le Kim, T.H.; Jang, J.; Kim, S.J.; Yoon, M.S.; Kim, J.W.; Nam, Y.S. Bioinspired Synthesis of Mesoporous Gold-silica Hybrid Microspheres as Recyclable Colloidal SERS Substrates. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.N.; Zhang, C.Q.; Wang, W.; Wang, P.C.; Zhou, J.P.; Liang, X.J. pH-responsive mesoporous silica nanoparticles employed in controlled drug delivery systems for cancer treatment. Cancer Biol. Med. 2014, 11, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutthavas, P.; Tahmasebi Birgani, Z.; Habibovic, P.; van Rijt, S. Calcium Phosphate-Coated and Strontium-Incorporated Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles Can Effectively Induce Osteogenic Stem Cell Differentiation. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2022, 11, 2101588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Zhu, Y.-J.; Zheng, J.-Q.; Chen, F.; Wu, J. Microwave-assisted hydrothermal preparation using adenosine 5′-triphosphate disodium salt as a phosphate source and characterization of zinc-doped amorphous calcium phosphate mesoporous microspheres. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2013, 180, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neufeld, B.; Neufeld, M.; Lutzke, A.; Schweickart, S.; Reynolds, M. Metal–Organic Framework Material Inhibits Biofilm Formation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1702255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, D.; Hu, F.; Kenry; Ji, S.; Wu, W.; Ding, D.; Kong, D.; Liu, B. Metal-Organic-Framework-Assisted In Vivo Bacterial Metabolic Labeling and Precise Antibacterial Therapy. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, e1706831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyszogrodzka, G.; Marszałek, B.; Gil, B.; Dorożyński, P. Metal-organic frameworks: Mechanisms of antibacterial action and potential applications. Drug Discov. Today 2016, 21, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.H.R.; Chen, K.; Lugtu-Pe, J.A.; AL-Mousawi, N.; Zhang, X.; Bar-Shalom, D.; Kane, A.; Wu, X.Y. Design and Optimization of a Nanoparticulate Pore Former as a Multifunctional Coating Excipient for pH Transition-Independent Controlled Release of Weakly Basic Drugs for Oral Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, I.; Bourguignon, T.; Li, X.; Patriarche, G.; Serre, C.; Marlière, C.; Gref, R. Degradation Mechanism of Porous Metal-Organic Frameworks by In Situ Atomic Force Microscopy. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Tan, P.; Fu, S.; Tian, X.; Zhang, H.; Ma, X.; Gu, Z.; Luo, K. Preparation and application of pH-responsive drug delivery systems. J. Control. Release 2022, 348, 206–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettlinger, R.; Lächelt, U.; Gref, R.; Horcajada, P.; Lammers, T.; Serre, C.; Couvreur, P.; Morris, R.E.; Wuttke, S. Toxicity of metal–organic framework nanoparticles: From essential analyses to potential applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 464–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X.; Hu, Y.; Xu, G.; Chen, W.; Xu, K.; Ran, Q.; Ma, P.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Cai, K. Regulation of the biological functions of osteoblasts and bone formation by Zn-incorporated coating on microrough titanium. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 16426–16440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, T.; Xu, H.; Wang, C.; Qin, H.; An, Z. Magnesium enhances the chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells by inhibiting activated macrophage-induced inflammation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, P.; Sutrisno, L.; Luo, Z.; Hu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Tao, B.; Li, C.; Cai, K. Fabrication of magnesium/zinc-metal organic framework on titanium implants to inhibit bacterial infection and promote bone regeneration. Biomaterials 2019, 212, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Liu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Cui, Z.D.; Yang, X.J.; Pan, H.; Yeung, K.W.K.; Wu, S. Metal Ion Coordination Polymer-Capped pH-Triggered Drug Release System on Titania Nanotubes for Enhancing Self-antibacterial Capability of Ti Implants. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 3, 816–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Dai, F.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework-8 with Encapsulated Naringin Synergistically Improves Antibacterial and Osteogenic Properties of Ti Implants for Osseointegration. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 8, 3797–3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatua, C.; Mukherjee, E.; Gurjeet Singh, T.; Chauhan, S.; Roy, P.; Lahiri, D. A pH-modulated polymeric drug-release system simultaneously combats biofilms and planktonic bacteria to eliminate bacterial biofilm. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 499, 156223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Pan, Z.; Choudhury, M.R.; Yuan, Z.; Anifowose, A.; Yu, B.; Wang, W.; Wang, B. Making smart drugs smarter: The importance of linker chemistry in targeted drug delivery. Med. Res. Rev. 2020, 40, 2682–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Ye, H.; Liu, Y.; Xu, L.; Wu, Z.; Hu, X.; Ma, J.; Pathak, J.L.; Liu, J.; Wu, G. pH dependent silver nanoparticles releasing titanium implant: A novel therapeutic approach to control peri-implant infection. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2017, 158, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, L.; Li, H.; Wang, T.; Ren, X.; Cheng, Y.; Li, Y.; Huang, Q. Layer-by-Layer Assembled Smart Antibacterial Coatings via Mussel-Inspired Polymerization and Dynamic Covalent Chemistry. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2022, 11, 2200112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothe, R.; Hauser, S.; Neuber, C.; Laube, M.; Schulze, S.; Rammelt, S.; Pietzsch, J. Adjuvant Drug-Assisted Bone Healing: Advances and Challenges in Drug Delivery Approaches. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eliaz, N. Corrosion of Metallic Biomaterials: A Review. Materials 2019, 12, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, J.; Wu, B.; Guo, X.W.; Wang, Y.J.; Chen, D.; Zhang, Y.C.; Du, K.; Oguzie, E.E.; Ma, X.L. Unmasking chloride attack on the passive film of metals. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, L.; Li, X.; Liang, H.; Zhang, J.; Lu, Q.; Zhou, G.; Tang, J.; Li, X. Navigating oxidative stress in oral bone regeneration: Mechanisms and reactive oxygen species-regulating biomaterial strategies. Regen. Biomater. 2025, 12, rbaf091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berbel, L.O.; Banczek, E.d.P.; Karousis, I.K.; Kotsakis, G.A.; Costa, I. Determinants of corrosion resistance of Ti-6Al-4V alloy dental implants in an In Vitro model of peri-implant inflammation. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandracci, P.; Mussano, F.; Rivolo, P.; Carossa, S. Surface Treatments and Functional Coatings for Biocompatibility Improvement and Bacterial Adhesion Reduction in Dental Implantology. Coatings 2016, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, C.; Nagaich, U.; Pal, A.K.; Gulati, N. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles in target drug delivery system: A review. Int. J. Pharm. Investig. 2015, 5, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodaei, T.; Schmitzer, E.; Suresh, A.P.; Acharya, A.P. Immune response differences in degradable and non-degradable alloy implants. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 24, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horprasertkij, K.; Dwivedi, A.; Riansuwan, K.; Kiratisin, P.; Nasongkla, N. Spray coating of dual antibiotic-loaded nanospheres on orthopedic implant for prolonged release and enhanced antibacterial activity. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 101102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.Q.; Yang, H.Y.; Luo, T.; Huang, C.; Tay, F.R.; Niu, L.N. Hollow mesoporous zirconia delivery system for biomineralization precursors. Acta Biomater. 2018, 67, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Liu, X.; Mao, C.; Liu, X.; Cui, Z.; Yang, X.; Yeung, K.W.K.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, S. Infection-prevention on Ti implants by controlled drug release from folic acid/ZnO quantum dots sealed titania nanotubes. Mater Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2018, 85, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echezarreta-López, M.M.; De Miguel, T.; Quintero, F.; Pou, J.; Landin, M. Antibacterial properties of laser spinning glass nanofibers. Int. J. Pharm. 2014, 477, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| pH-Sensitive Material | pH-Sensitive Release Data | Antibacterial Performance | Osseointegration Performance | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alginate dialdehyde-gentamicin and chitosan | Short-term release (24 h), 17 µg of gentamicin at pH = 7.4, 38.1 µg at pH = 5.8. Long-term (10 days) release, 44 µg at pH = 7.4 and 130.3 µg at pH = 5.8 | Lower adhered bacteria to this coating after 72 h (less than half of pristine Ti or even TNT). | The highest osteoblast viability, ECM mineralization, and expression of Runx2 are in TNT-BMP2, TNT-BMP2-LBL, and TNT-BMP2-LBLg. Increased cell adhesion and proliferation | [48] |

| Chitosan | In an 8-day study, zero weight loss at pH = 7.0 and total release at pH = 5.0 from chitosan/Eudragit E 100 coating | Not studied | Not studied | [53] |

| Chitosan | The final concentration of the released antibiotic is 90% at acidic pH and 70% at neutral pH. | Not studied | siRNA release provided appropriate cell viability. | [49] |

| Chitosan | Release of 20, 30, and 60.2% in 100 min, 600 min, and eight days at pH = 7.4, and 33, 45, 81.4% for pH = 6.8 | Decreased growth of E. coli and S. aureus by 76.1% and 71.8%, respectively. | Not studied | [51] |

| Chitosan and poly-capri-lactan | Daptomycin-encapsulated coating: 90% release at pH = 5.5 after 2 h. Vancomycin-encapsulated coatings also reacted to pH = 5.5 after 20 h. | Not studied | Not studied | [44] |

| Chitosan and pH-sensitive hydrazone bond | Initial fast-release, slow-release for 30 days, pH drop increased the release significantly. | Not studied | Improved osteogenesis by inhibiting osteoclasts and driving bone stem cells, ALP optical density = 0.8 | [47] |

| Chitosan | Not studied | 89% bacterial adhesion reduction | Cell proliferation and calcium deposition were improved by up to 44%, and no significant gene expression | [43] |

| Chitosan | Cu2+ release gradually increased to a maximum level at day 20 for pH levels 5.8 and 7.4. | The highest antibacterial strength against E. coli was less than 1 × 106 adhered cells, and against S. aureus, around 2 × 108 adhered cells | Not studied | [52] |

| Chitosan | Ag ion release in 14 days of exposure was less than 30% at pH = 7.5, around 55% at pH = 5.5, and around 75% at pH = 3.5 | Reduction of dead bacteria by 66.1% for uncoated, 95.4% for dip-coated, and 98.6% for spin-coated | Controlled release improved the adhesion and proliferation of preosteoblast cells. | [50] |

| Chitosan | Release at pH = 6.0 (90% in 80 min) and at pH = 7.4 (5% in 80 min) | Not studied | Bone volume increase of as much as 100% in 4 weeks | [46] |

| Chitosan | In 30 h, the release was not different for pH = 7.4 and pH = 5.5. At a lower pH, the release concentration was higher by 5–7 µg | Not studied | Higher bone regeneration in DOX-loaded coatings than in chitosan control groups, increased bone and mineral formation, good osteogenesis in chitosan-based coatings | [45] |

| Chitosan | 10% release in the first 0.5 h and pH-sensitive release in the next 10 days. Release at pH = 7.4 and pH = 5 only differed through 12 h to 144 h exposure and only as much as 5–20 wt%. | Initial bacteria count of 1.51 × 106 t decreases to 1370 for after 18 h = antibacterial rate of 99.97% | Complete coverage of implant surface with needle-shaped and spherical particles of calcium and phosphate in 21 days | [61] |

| Silk fibroin | Ion release = 1.6 µg/mL at pH = 5.0, = 0.4 µg/mL at pH = 7.4, low Ag release = less side effects | Antibacterial rate of around 99% for all the test duration at pH = 5, ROS production, complete bacterial eradication within 4 h | Highest osteoblast-related gene expression, osteogenic proteins expression, bone regeneration, and osseointegration on Ag@AP/SF than native Ti and complete coverage of the surface in 8 weeks | [58] |

| Silk fibroin | Controlled and higher release of Cu2+ (40 µg to nearly 0 at pH = 7.4) and Ag2+ (4.5 to 2.5 µg at pH = 7.4) at pH = 5.0 in over 30 days | Antibacterial activity scores of 2 and 1.5 for PEEK at pH = 7.4 and 5.0, respectively | High expression of ALP and cell growth, and OCN. No negative effect from Ag full covering of implant with new bone in 12 weeks in vivo. | [56] |

| Collagen I crosslinked with antimicrobial peptide | Long-term pH-response for 30 days at pH = 6.0. The highest release = 90% for pH = 6.0 and 50% for pH = 7.4 | Antibacterial efficiency = close to 100% at day 1 and 4 and 90% at day 8 | Increased mitochondrial activity and cell proliferation | [59] |

| Silk fibroin &K3PO4 | When corrosion occurred, Mg2+ was released from the surface pH increased. Alkaline pH caused release, which reacted with Mg2+ and formed a stable salt. This formed a passive film and helped the surface to heal. | Not studied | Higher ALP activity in the silk-KP group. Higher mineralization in both silk and silk-kp groups. Enhanced cell attachment over both silk and silk-KP | [57] |

| Polyethyleneimine | pH drop and deionization of carboxyl group: Release of QAs | Bacterial activity at pH = 5.0: less than 5% no antibacterial effect at pH = 7.4 | Better bone binding and growth, and less inflammatory response. Higher hydrophilicity & reduced cell adhesion | [77] |

| PDMAEMA-grafted HNTs | pH-sensitivity differs depending on the loaded compound. For DPH, release was slightly higher at pH = 1.2 than at pH = 7.4 in the 25-h test. Meanwhile, release was much higher for DS at pH = 7.4 than pH = 1.2 in 25 h. | Not studied | Not studied | [76] |

| Polyaniline (PANI-pH-sensitive bond) | Not studied | pH-sensitivity as a tool to diagnose bacterial infection at the prosthesis interface. | Not studied | [71] |

| Star-poly [2-(dimethylamino) ethyl methacrylate] | Higher drug release at a lower pH of 6.0. initial fast release and then slowed-down release | Not studied | Controlled local inflammation for 8 weeks | [75] |

| Poly-L-lysine | Initial burst release of the drug for pH of 7.4 and 4.5, with almost double values for pH = 4.5. Then, constant release from day 3 to 15. | antibacterial activity: 0 Log/CFU/mL for compared to 6 Log/CFU/mL for uncoated Ti | [72] | |

| PLH and poly(methacrylic acid) | Initial burst release and then gradual increase or decrease over time. The highest release: at pH = 4.0, around 1700 ng/cm2 over 25 days, at pH = 7.0, around 500 ng/cm2 | Not studied | Not studied | [80] |

| PLH and poly(methacrylic acid) | Lower molecular weight poly(methacrylic acid) causes a lower initial burst and higher sustained release. The order of coating PH/MAA bilayers and PL-FITC affected the release rate. The highest release: around 10 µg at pH = 5.0 and 4 µg at pH = 7.4 | Not studied | Improves osseointegration due to the presence of BMP-2 | [81] |

| Polydopamine | The highest release was around 2.5 and 10 µg, respectively, after 30 days at pH = 4.5 and pH = 7.4. | 99% antibacterial efficiency after 4 h—local release of Ag+ | Higher ALP activity and calcium-based ECM production, Col I expression hierarchical structure and better osteogenesis. higher bone growth in vivo | [90] |

| Catechol borate bonds and imine bonds | Drug release was over 80% at pH = 5 and around 10% at pH = 7.4 after 120 h of long experiments. | Around 0 antibacterial activity compared to 2–14 CFU × 104/mL bacteria count for uncoated surfaces. | Not studied | [111] |

| MOF-74 | The final concentration of 2,5-dihydroxyterephthalic acid (DHTA), Mg2+, and Zn2+ after 168 h of release test was almost the same for pH = 7.4 and 6.5, but the initial slope was steeper for pH = 6.5. | 80% antibacterial efficiency over 6 h still antibacterial after 21 days | Upregulation of osteogenic genes | [105] |

| ZIF-67 | Fast response to acidic environment differentiation. | Enhanced antibacterial activity by over 90% by inducing an alkaline environment. around 95% antibacterial efficiency | Suppressed possible inflammatory response. Improved osseointegration by helping mesenchymal stromal cells. Improved osteodifferentiation. Higher ALP expression. high bone formation after 4 weeks | [18] |

| ZIF8 | Higher release-time rate at pH = 5.5 compared to pH = 7.4. maximum Release in 4 days and perseverance until day 21. | Enhanced antibacterial activity by 93.6% and 88.3% for samples without naringin and with naringin (Nar) | ALP activity, high collagen secretion, higher ECM mineralization, and high expression of Runx2, Col I, OPN. new bone formation to total bone volume = 39.4, trabecular thickness = 0.23, trabecular number = 6.58. | [107] |

| Zn/Ag-MOF (The coordination bond between the CPs and TNTs by the Zn2+ metal ion) | After 22 days, Ag+ release grew from 1250 µg/mL at pH = 7.4 to around 2000 µg/mL at pH = 5.4—similarly, Zn2+ release changed from 200 µg/mL at pH = 7.4 to around 900 µg/mL at pH = 5.4 | Ag+ helped antibacterial performance. an efficiency of over 99% against both E. coli and S. aureus | Zn2+ promoted osteogenesis. (Cell proliferation decreases if Zn2+ release is higher than a range). Higher ALP expression. Higher mitosis in osteoblasts | [106] |

| CaP or CaZnP | Stable in a lower pH of 5.0—100% release after a maximum of 150 h of the experiment under pH = 5.0 | Not studied | Increase in ALP activity (3.5-fold), BMP2 and Runx2 expression, OCN and Col I expression. The highest calcium deposition | [94] |

| Zn/ACP mesoporous microspheres | Almost 100% release of zinc after 120 h in pH = 4.0, around 20% for pH = 7.0. | 91.93% antibacterial efficiency against E. coli and 99.71% efficiency against S. aureus | Not studied | [95] |

| 2-(diisopropylamine)ethyl methacrylate] (PDPA) | The mono-layer was covered with 28% more bacteria than the 3-layer coating. The normalized (by 100) number of bacteria colonies was around 15 fewer in pH = 5.5 compared to pH = 7.5 in the 3-layer. | Not studied | [82] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gholami, R.; Valipour Motlagh, N.; Yousefi, Z.; Gholami, F.; Richardson, J.J.; Akhavan, B.; Adibnia, V.; Truong, V.K. Recent Advances in pH-Responsive Coatings for Orthopedic and Dental Implants: Tackling Infection and Inflammation and Enhancing Bone Regeneration. Coatings 2025, 15, 1471. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121471

Gholami R, Valipour Motlagh N, Yousefi Z, Gholami F, Richardson JJ, Akhavan B, Adibnia V, Truong VK. Recent Advances in pH-Responsive Coatings for Orthopedic and Dental Implants: Tackling Infection and Inflammation and Enhancing Bone Regeneration. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1471. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121471

Chicago/Turabian StyleGholami, Reyhaneh, Naser Valipour Motlagh, Zahra Yousefi, Fahimeh Gholami, Joseph J. Richardson, Behnam Akhavan, Vahid Adibnia, and Vi Khanh Truong. 2025. "Recent Advances in pH-Responsive Coatings for Orthopedic and Dental Implants: Tackling Infection and Inflammation and Enhancing Bone Regeneration" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1471. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121471

APA StyleGholami, R., Valipour Motlagh, N., Yousefi, Z., Gholami, F., Richardson, J. J., Akhavan, B., Adibnia, V., & Truong, V. K. (2025). Recent Advances in pH-Responsive Coatings for Orthopedic and Dental Implants: Tackling Infection and Inflammation and Enhancing Bone Regeneration. Coatings, 15(12), 1471. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121471