Abstract

This study prepared Copper(Cu)/Aluminum(Al) composite materials using hot-rolling technology. The influence of annealing treatment on the interfacial microstructure was systematically investigated, thereby elucidating the correlation between microstructural characteristics and thermal conductivity. The results demonstrated that annealing treatment induced the formation of a continuous intermetallic compound layer at the Cu/Al interface, with its thickness increasing proportionally to elevated temperature and prolonged duration. After spraying graphene onto the aluminum surface via ultrasonic spraying technology, followed by rolling and an annealing treatment, the intermetallic compounds at the Cu/Al interface exhibited a discontinuous distribution pattern. When annealed at 300 °C, the thermal conductivity of the Cu/Al composite plate increased progressively with prolonged duration. For instance, in the absence of graphene, the value increased from 39.288 to 61.827; when graphene was applied via ultrasonic spraying with a spraying distance of 1 mm, the value increased from 49.884 to 73.203, whereas at 400 °C annealing, it exhibited a notable decline as annealing time extended. Graphene at the interface inhibits the diffusion of Cu/Al atoms, reduces the formation of intermetallic compounds, establishes efficient thermal conduction paths, and ultimately enhances the thermal conductivity of the composite material.

1. Introduction

Aluminum has the characteristics of low density, high strength, strong ductility, good heat storage performance, good conductivity, and thermal conductivity. Copper has the characteristics of excellent conductivity and thermal conductivity, high ductility, and easy processing. Copper/aluminum composites combine the low resistance and high thermal conductivity of copper with the characteristics of light weight, corrosion resistance, and low cost of aluminum, so that copper and aluminum can complement each other in cost and performance, resulting in a great synergy effect. Therefore, copper/aluminum layered composites have been widely used in aerospace, electronics and power, communications, transportation, photovoltaic new energy, and other fields [1,2,3]. Abbasi [4] prepared copper/aluminum composites via a cold rolling composite method, and studied the growth law of intermetallic compounds. It was found that the thickness of intermetallic compounds increased with the increase in heat treatment time. After heat treatment, five layers were detected at the interface, which were Cu3Al, Cu4Al3, saturated solid solution (9~13% Al), CuAl, and CuAl2. Kim [5] adjusted the thickness and type of intermetallic compounds via short-time annealing at 400 °C. It was found that when the annealing time was less than 20 min, only AlCu and Al4Cu9 phases were formed, and the total thickness was less than 1 μm. When the annealing time was more than 30 min, a brittle AlCu phase was added, and the total thickness of intermetallic compounds increased to 3.12 μm. The copper/aluminum composites prepared by rolling need to be heat treated to improve the interface bonding strength, but the intermetallic compounds formed at the interface during heat treatment reduce the thermal conductivity, electrical conductivity, and mechanical properties, which greatly limits the application and development of copper/aluminum composites [6,7,8,9,10,11]. Graphene has recently attracted considerable attention in metal matrix composites due to its unique two-dimensional thin-layer structure and excellent properties, such as its exceptional thermal and electrical conductivity [12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Numerous studies have successfully developed high-performance copper/aluminum composites by exploiting the exceptional properties of graphene. Yang [19] studied the effect of copper-coated graphene on the microstructure and properties of 6061 aluminum matrix composites. The tensile strength and yield strength of the composites were significantly improved after adding graphene. At the same time, the conductivity and thermal conductivity of 6061Al were improved by adding graphene. Wang [20] mixed graphene powder with aluminum powder to prepare graphene/aluminum composites. The study found that when the content of graphene was 0.5 wt.%, graphene was evenly dispersed at the grain boundary of aluminum matrix, and the interface was tightly bonded. No harmful phase such as Al4C3 was found. When the content of graphene was 0.5 wt.%, the thermal conductivity was 165 W·m−1·K−1 and the conductivity was 52% IACS, which were 7.1% and 4% higher than that of pure aluminum, respectively. However, excessive graphene would lead to performance degradation.

This study successfully fabricated copper/graphene/aluminum composites by ultrasonically spraying graphene onto an aluminum surface at various spray distances followed by a hot-rolling process. The composites were subsequently annealed at different temperatures and durations. The research revealed that the introduction of graphene significantly altered the interfacial microstructure of the Cu/Al composite. Moreover, the thermal conductivity of the graphene-reinforced composite surpassed that of the conventional graphite-free Cu/Al laminates. Simultaneously, it was found that a shorter spray distance corresponded to higher thermal conductivity of the material. These findings demonstrate that incorporating graphene at the Cu/Al interface effectively enhances the thermal conductivity of the composite. Consequently, this work establishes a critical relationship between interfacial microstructure and thermal transport properties, providing valuable theoretical insights for developing high-thermal-conductivity Cu/Al composites.

2. Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

Copper/aluminum clad plates were fabricated using a 1.4 mm thick 1060 aluminum alloy sheet and a 0.3 mm thick T2 copper sheet. The elemental composition of Al is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of 1060Al (wt.%).

The experimental equipment primarily consisted of a heating stage and a non-reversible two-high rolling mill. The testing equipment mainly included a Sigma 360 scanning electron microscope (SEM), Sigma 360, Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany and an LFA 467 laser flash apparatus (LFA).

2.2. Experimental Methods

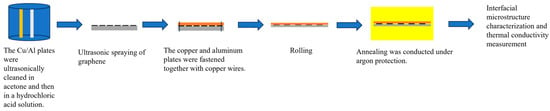

The experimental procedure of this study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic flowchart of the experimental process.

2.2.1. Pre-Rolling Treatment

After removing surface contaminants (such as oil stains) from the copper and aluminum sheets, laser surface texturing was performed on the aluminum surface. Subsequently, a uniform pre-deposition of graphene was applied to the aluminum sheet surface via ultrasonic spraying technology, with nozzle traverse spacings of 5 mm, 3 mm, 2 mm, and 1 mm. The processed copper and aluminum sheets were then assembled and secured using copper binding wires.

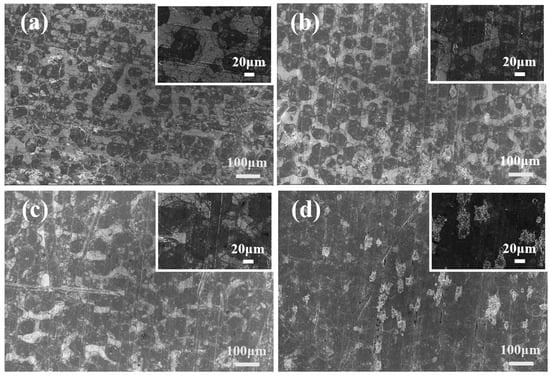

Figure 2 shows the aluminum surface after ultrasonic spray coating of graphene. Graphene coverage rates were 59.47% at 5 mm nozzle spacing, 66.56% at 3 mm, 70.69% at 2 mm, and 83.86% at 1 mm, demonstrating a decrease in coverage with increasing spray spacing.

Figure 2.

Aluminum surface after ultrasonic spraying of graphene. (a) 5 mm; (b) 3 mm; (c) 2 mm; (d) 1 mm.

2.2.2. Hot-Roll Bonding and Annealing

Prior to rolling, the copper wire-bound Cu/Al assembly was positioned aluminum-side-down on a heating stage and heated to 250 °C. This was followed by a single-pass rolling process using a unidirectional rolling mill at a speed of 0.2 m/s with a 50% reduction rate, resulting in a Cu/Al composite with a final thickness of 0.85 mm. Annealing treatments were conducted in a tubular furnace under an argon protective atmosphere at temperatures of 300 °C and 400 °C, with holding times of 0.5 h, 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, and 10 h, respectively, at a heating rate of 5 °C/min. This specific combination of time and temperature effectively promotes atomic diffusion and recrystallization at the interface, thereby enhancing the interfacial bonding. Simultaneously, the selected heating rate ensures uniform heat distribution throughout the sample, minimizing deformation or cracking induced by thermal stress.

2.2.3. Interfacial Microstructure Characterization and Property Analysis

The annealed Cu/Al composite samples were ground and polished to enable interfacial microstructure analysis. Thermal conductivity of the composites was measured using a laser flash apparatus (LFA467); the data were obtained from measurements conducted at 25 °C. The Cowburn model was employed for data fitting and analysis, with testing performed on three independent samples.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Interfacial Microstructural Characterization

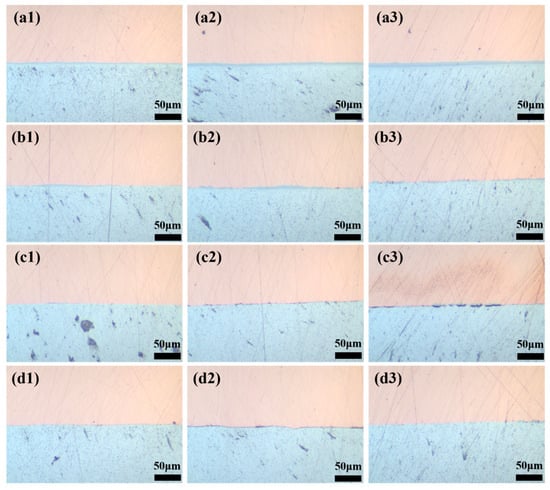

Figure 3 presents the microstructures of the composites after annealing at 400 °C. Figure 3(a1–a3) are the metallographic images of the samples annealed for 1, 4, and 10 h without graphene, respectively. As the holding time increases, the thickness of the intermetallic compound (IMC) layer increases from 4.30 μm to 19.21 μm. Figure 3(b1–b3) show the metallographic images of the copper/graphene/aluminum composites with an ultrasonic spraying distance of 5 mm after annealing for 1, 4, and 10 h, respectively. The thicknesses of the intermetallic compounds (IMCs) were 3.77, 7.82, and 13.22 μm, respectively. Figure 3(c1–c3) and Figure 3(d1–d3) present the corresponding micrographs for composites with ultrasonic spraying distances of 3 mm and 1 mm, respectively, under the same annealing durations. It can be observed that as the holding time increases, both the thickness and the amount of the intermetallic compounds (IMCs) increase. Furthermore, the thickness and quantity of the IMCs decrease with a reduction in the ultrasonic spraying distance.

Figure 3.

Metallographic images of ultrasonically sprayed graphene-modified Cu/Al composite plates after 400 °C annealing: (a1) graphene-free, 400 °C/1 h; (a2) graphene-free, 400 °C/4 h; (a3) graphene-free, 400 °C/10 h; (b1) 5 mm graphene interlayer (ultrasonic spraying), 400 °C/1 h; (b2) 5 mm graphene, 400 °C/4 h; (b3) 5 mm graphene, 400 °C/10 h; (c1) 3 mm graphene interlayer (ultrasonic spraying), 400 °C/1 h; (c2) 3 mm graphene, 400 °C/4 h; (c3) 3 mm graphene, 400 °C/10 h; (d1) 1 mm graphene interlayer (ultrasonic spraying), 400 °C/1 h; (d2) 1 mm graphene, 400 °C/4 h; (d3) 1 mm graphene, 400 °C/10 h.

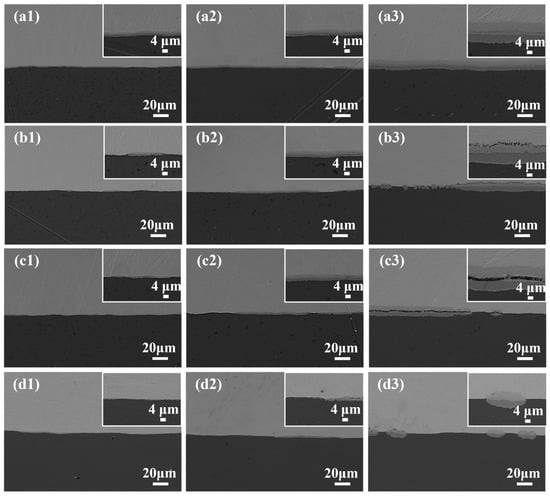

Figure 4(a1) shows the interface of the Cu/Al composite annealed at 300 °C for 4 h. Under this annealing condition, the intermetallic compound (IMC) layer at the Cu/Al interface exhibited a thickness of 2.27 μm. As observed in Figure 4(a2), thickening of intermetallic compounds (IMCs) began at the Cu/Al composite interface after 10 h annealing at 300 °C, with an average thickness of approximately 3.57 μm. Figure 4(a3) shows that the intermetallic compound (IMC) layer at the Cu/Al composite interface exhibited substantial thickening after annealing at 400 °C for 10 h, reaching an average thickness of approximately 19.21 μm. This phenomenon arises from enhanced diffusion kinetics at elevated temperatures and extended durations: increased thermal activation energy promotes atomic migration, thereby elevating diffusion coefficients and accelerating intermetallic compound (IMC) layer growth.

Figure 4.

SEM micrographs of Cu/Al composite plates under varied conditions: (a1) graphene-free, 300 °C/4 h; (a2) graphene-free, 300 °C/10 h; (a3) graphene-free, 400 °C/10 h; (b1) 5 mm graphene interlayer (ultrasonic spraying), 300 °C/4 h; (b2) 5 mm graphene, 300 °C/10 h; (b3) 5 mm graphene, 400 °C/10 h; (c1) 3 mm graphene interlayer (ultrasonic spraying), 300 °C/4 h; (c2) 3 mm graphene, 300 °C/10 h; (c3) 3 mm graphene, 400 °C/10 h; (d1) 1 mm graphene interlayer (ultrasonic spraying), 300 °C/4 h; (d2) 1 mm graphene, 300 °C/10 h; (d3) 1 mm graphene, 400 °C/10 h.

Figure 4(b1–b3) presents the interfacial microstructure of a Cu/Al composite with 5 mm ultrasonically sprayed graphene after annealing at 300 °C for 4 h, exhibiting an intermetallic compound (IMC) thickness of 2.04 μm. Following 10 h annealing at 300 °C, the intermetallic compound (IMC) thickness increased to 3.30 μm. After 400 °C/10 h annealing, substantial IMC growth yielded a thickness of 13.22 μm.

Figure 4(c1) displays the interfacial microstructure of the 3 mm ultrasonically sprayed graphene-coated Cu/Al composite after 300 °C/4 h annealing, exhibiting a 1.5 μm thick intermetallic compound (IMC) layer. Upon extending the holding time to 10 h at 300 °C (Figure 4(c2)), IMC thickness increased to 3.05 μm. Further elevated annealing at 400 °C for 10 h (Figure 4(c3)) resulted in substantial IMC growth to 11.97 μm.

Figure 4(d1) demonstrates a 0.62 μm intermetallic compound (IMC) layer at the interface after annealing at 300 °C for 4 h with ultrasonically sprayed graphene (1 mm nozzle spacing). Figure 4(d2) reveals increased IMC thickness (2.91 μm) following extended 10 h annealing at 300 °C, while Figure 4(d3) shows substantial IMC growth to 8.69 μm under 400 °C/10 h annealing. Despite progressive thickening of the intermetallic compounds (IMCs) with increasing annealing temperature and holding time, the IMC layers maintained a discontinuous morphology.

As shown in Figure 4, the introduction of graphene significantly suppresses the formation of a continuous intermetallic compound (IMC) layer, promoting its transformation into isolated islands. This morphological change indicates a substantial reduction in both the total volume and phase fraction of the IMCs, suggesting that the two-dimensional layered structure of graphene forms an effective physical diffusion barrier at the Cu/Al interface. This barrier markedly hinders the mutual diffusion of Cu and Al atoms. Furthermore, this inhibitory effect intensifies as the ultrasonic spraying distance decreases.

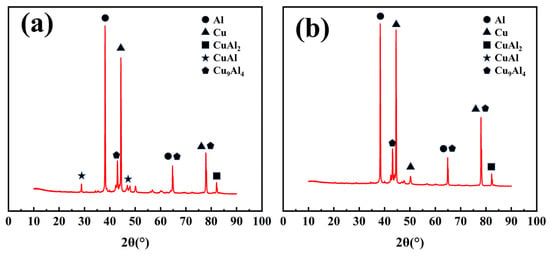

Figure 5 shows the XRD pattern of the graphene-free Cu/Al composite annealed at 400 °C for 10 h. The presence of diffraction peaks for Cu9Al4, CuAl, and CuAl2 confirms the formation of brittle intermetallic compounds (IMCs) at the interface during annealing.

Figure 5.

XRD pattern of the copper/aluminum composite without graphene after annealing at 400 °C for 10 h. (a) Al side; (b) Cu side.

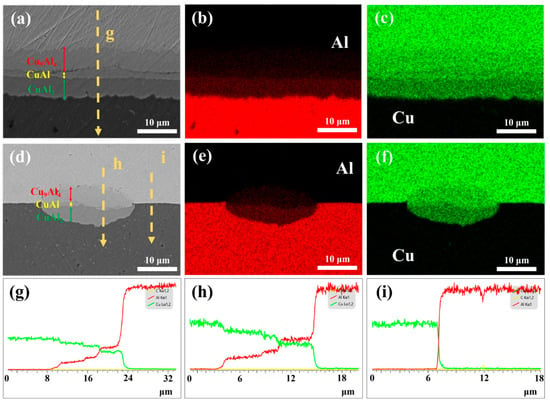

Figure 6 presents the interfacial microstructure and elemental distribution in the Cu/Al composite. As shown in Figure 6a–c, continuous tri-layer intermetallic compounds (IMCs) formed at the Cu/Al interface in the graphene-free composite due to atomic interdiffusion, with these interfacial IMCs composed exclusively of aluminum (Al) and copper (Cu) elements. As shown in Figure 6d–f, localized diffusion of copper and aluminum atoms occurred in the 1 mm ultrasonically sprayed graphene-coated composite after 400 °C/10 h annealing, forming island-like intermetallic compounds (IMCs) exclusively composed of Al and Cu elements. At graphene-covered locations, no diffusion of copper or aluminum atoms occurred, confirming that graphene effectively prevents the formation of intermetallic compounds (IMCs).

Figure 6.

Elemental distribution and phase layer analysis at the Cu/Al composite interface after 400 °C/10 h annealing treatment. (a) Interface microstructure, (b) Al and (c) Cu elements distribution without graphene addition after holding at 400 °C for 10 h; (d) Interface (e) Al and (f) Cu elements distribution with graphene sprayed at 1 mm spacing after holding at 400 °C for 10 h; (g) Line scanning curve without graphene addition after holding at 400°C for 10 h; (h,i) Line scanning curve with graphene sprayed at 1 mm spacing after holding at 400 °C for 10 h.

Figure 6g presents the interfacial microstructure and corresponding EDS line scanning profile of the graphene-free Cu/Al composite after annealing at 400 °C for 10 h. Figure 6h,i present line-scan profiles at distinct locations of the ultrasonically sprayed graphene-reinforced Cu/Al composite plate with a 1 mm spray pitch. The results demonstrate the absence of intermetallic compound (IMC) formation at specific regions after 400 °C/10 h annealing treatment. Based on EDS line and point scanning analyses, the interfacial intermetallic compounds were identified as three distinct layers progressing from the Cu side to the Al side: Cu9Al4, CuAl, and CuAl2 respectively.

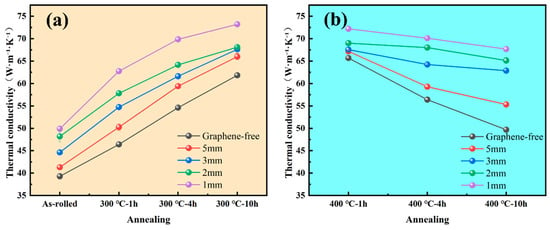

3.2. Thermal Conductivity of Cu/Al Composite Plate

Figure 7 presents the thermal conductivity of the Cu/Al composite. As indicated in the figure, the graphene-free composite exhibits a thermal conductivity of 39.288 W·m−1·K−1. Thermal conductivity measurements of Cu/graphene/Al composites fabricated with ultrasonically sprayed graphene at 1, 2, 3, and 5 mm nozzle spacings yielded values of 49.884, 48.186, 44.632, and 41.300 W·m−1·K−1, respectively, demonstrating an inverse correlation between spray spacing and interfacial heat transfer efficiency. Thus, the thermal conductivity of Cu/graphene/Al composites increases proportionally with graphene coverage on the aluminum surface, as demonstrated by enhanced interfacial thermal transport at higher coverage percentages. Figure 7a demonstrates the thermal conductivity of the Cu/Al composite plate after 300 °C annealing, revealing a dual enhancement trend: conductivity increases with both prolonged holding time and elevated graphene coverage. After 300 °C/10 h annealing, the graphene-free Cu/Al composite exhibited a thermal conductivity of 61.827 W·m−1·K−1. The Cu/graphene/Al composite with 1 mm ultrasonically sprayed graphene exhibited a thermal conductivity of 73.203 W·m−1·K−1 after 300 °C/10 h annealing. The Cu/graphene/Al composites with 2 mm, 3 mm, and 5 mm ultrasonically sprayed graphene exhibited thermal conductivities of 68.092 W·m−1·K−1, 67.611 W·m−1·K−1, and 65.997 W·m−1·K−1, respectively, after 300 °C/10 h annealing. Figure 7b presents the thermal conductivity of the Cu/Al composite plate after 400 °C annealing, demonstrating a decrease in thermal conductivity with prolonged holding time under these conditions. The graphene-free Cu/Al composite exhibited a thermal conductivity of 65.682 W·m−1·K−1 after 1 h annealing at 400 °C. The Cu/graphene/Al composite with 1 mm ultrasonically sprayed graphene exhibited a thermal conductivity of 72.182 W·m−1·K−1 after 400 °C annealing, while composites with 2 mm, 3 mm, and 5 mm spraying yielded conductivities of 68.993 W·m−1·K−1, 67.541 W·m−1·K−1, and 67.164 W·m−1·K−1, respectively. After 400 °C annealing, the thermal conductivity of the Cu/Al composite plate further decreased; however, Cu/graphene/Al composites with ultrasonically sprayed graphene still exhibited superior thermal conductivity compared to the graphene-free Cu/Al composite plate.

Figure 7.

Thermal conductivity of the graphene-modified Cu/Al composite plate under different annealing regimes: (a) 300 °C, (b) 400 °C.

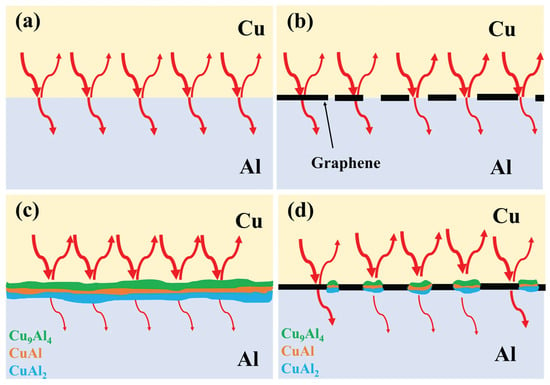

Figure 8 illustrates the relationship between thermal conductivity and interfacial microstructure. Figure 8a depicts the interface prior to annealing, where bonding is predominantly mechanical bonding. Interfaces between dissimilar materials in this state cause strong phonon/electron scattering, resulting in low thermal conductivity. Figure 8b illustrates the thermal conduction schematic at the Cu/Al composite interface with graphene addition. Due to graphene’s extremely high thermal conductivity, it provides high-speed pathways for heat transfer at the interface, resulting in superior thermal conductivity of the graphene-sprayed Cu/Al composite plate compared to the pure Cu/Al composite plate. Figure 8c depicts a continuous tri-layer intermetallic compound formed at the Cu/Al interface. Due to the relatively low thermal conductivity of intermetallic compounds, heat transfer is hindered, resulting in reduced thermal conductivity. Figure 8d illustrates the heat transfer mechanism at the interface of the ultrasonically sprayed graphene-coated Cu/Al composite plate. Although intermetallic compounds form, graphene’s barrier effect restricts them to a discontinuous morphology with reduced thickness compared to graphene-free composites. Simultaneously, graphene provides high-speed pathways for heat transfer, resulting in higher thermal conductivity than the pure Cu/Al composite plate. After annealing at 300 °C, material recovery and recrystallization occur, restoring material properties and consequently increasing thermal conductivity. Under 400 °C annealing, progressive thickening of intermetallic compounds at the Cu/Al interface significantly impacts thermal conduction, resulting in a declining trend in the thermal performance of the Cu/Al composite plate.

Figure 8.

Correlation between interfacial microstructure and thermal conductivity in graphene-modified Cu/Al composite plate. (a) Heat transfer process without graphene addition before heat treatment; (b) Heat transfer process with graphene addition after heat treatment; (c) Heat transfer process without graphene before heat treatment; (d) Heat transfer process with graphene after heat treatment.

4. Conclusions

- After heat treatment of the Cu/Al composite, intermetallic compounds (IMCs) form at the interface. With increasing temperature and holding time, IMC thickness progressively increases, with the primary phases sequenced from the Cu side to the Al side as: Cu9Al4, CuAl, and CuAl2.

- Annealing after graphene addition reveals that while intermetallic compound (IMC) thickness increases with elevated temperature/time, these IMCs exhibit a discontinuous morphology. This discontinuity arises from non-uniform graphene distribution induced by rolling deformation, leading to IMC growth exclusively within gaps of the graphene coating. Both the quantity and thickness of IMCs decrease proportionally with increasing graphene coverage percentage.

- During 300 °C annealing, the thermal conductivity of the Cu/Al composite plate increases with prolonged holding time, whereas at 400 °C annealing, conductivity decreases with extended holding time. Graphene-modified Cu/Al composite plate exhibit superior thermal conductivity compared to their graphene-free counterparts, with conductivity increasing proportionally to graphene coverage percentage. This enhancement primarily stems from graphene’s interfacial optimization: it restructures the interface morphology, suppresses intermetallic compound (IMC) formation, and provides high-speed thermal pathways, collectively elevating thermal conductivity beyond unmodified composites.

- Although the ultrasonic spraying parameters (e.g., distance, concentration) used in this study were optimized, their systematic effects across a wider range remain to be further investigated. Additionally, while the current work primarily evaluated performance through microstructure and thermal conductivity, other characterization methods could be employed in the future to enable a more in-depth analysis of the properties.

Author Contributions

Y.L., Z.Y. and Y.S. conceived and directed the experiments. Y.L., R.W., and L.W. co-wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and helped with the preparation of the final manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52401017) and (92160201).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study are not publicly available due to the ongoing work.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to ceshihui (www.ceshihui.cn) for the SEM testing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Madhusudan, S.; Sarcar, M.M.M.; Bhargava, N. Sliding Wear Studies on Aluminium–Copper Composites. Compos. Interfaces 2011, 18, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.W.; Ke, W.B.; Wang, R.Y.; Wang, I.S.; Chiu, Y.T.; Lu, K.C.; Lin, K.L.; Lai, Y.S. The influence of Pd on the interfacial reactions between the Pd-plated Cu ball bond and Al pad. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2013, 231, 599–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapanathan, T.; Khoddam, S.; Zahiri, S.H.; Zarei-Hanzaki, A. Strength changes and bonded interface investigations in a spiral extruded aluminum/copper composite. Mater. Des. 2014, 57, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, M.; Taheri, A.K.; Salehi, M.T. Growth rate of intermetallic compounds in Al/Cu bimetal produced by cold roll welding process. J. Alloys Compd. 2001, 319, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Lee, K.S.; Han, S.H.; Hong, S.I. Interface strengthening of a roll-bonded two-ply Al/Cu sheet by short annealing. Mater. Charact. 2021, 174, 111021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslami, P.; Karimi Taheri, A.; Zebardast, M. A comparison between cold-welded and diffusion-bonded Al/Cu bimetallic rods produced by ECAE process. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2013, 22, 3014–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hug, E.; Bellido, N. Brittleness study of intermetallic (Cu, Al) layers in copper-clad aluminium thin wires. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2011, 528, 7103–7106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Lee, Y.J.; Park, K.T.; Jeong, H.G.; Lee, J.H. Mechanical and asymmetrical thermal properties of Al/Cu composite fabricated by repeated hydrostatic extrusion process. Met. Mater. Int. 2015, 21, 402–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Wang, X.; Liu, M.; Ma, K.; Wang, L.; Liu, Q.; Wang, C.; Jiang, X.; Li, H.; Tang, Y.; et al. PCTS-controlled synthesis of L10/L12-typed Pt-Mn intermetallics for electrocatalytic oxygen reduction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2310487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Fu, G.; Li, Y.; Liang, L.; Grundish, N.S.; Tang, Y.; Goodenough, J.B.; Cui, Z. General strategy for synthesis of ordered Pt3M intermetallics with ultrasmall particle size. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 7857–7863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, N.; Friedrich, S.; Friedrich, B. Purification of the Al2Cu intermetallic compound via zone melting crystallization technique. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 26, 973–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbayachi, V.B.; Ndayiragije, E.; Sammani, T.; Taj, S.; Mbuta, E.R. Graphene synthesis, characterization and its applications: A review. Results Chem. 2021, 3, 100163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.K.; Sahoo, S.; Wang, N.; Huczko, A. Graphene research and their outputs: Status and prospect. J. Sci. Adv. Mater. Devices 2020, 5, 10–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Chai, Z.; Shi, Q.; Liu, Y.; Wang, W. Graphene superlubricity: A review. Friction 2023, 11, 1953–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.K.; Sharma, B.; Saju, B.R.; Shukla, A.; Saxena, A.; Maurya, N.K. Effect of Graphene nanoparticles on microstructural and mechanical properties of aluminum based nanocomposites fabricated by stir casting. World J. Eng. 2020, 17, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoselov, K.S.; Geim, A.K.; Morozov, S.V.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Dubonos, S.V.; Grigorieva, I.V.; Firsov, A.A. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science 2004, 306, 666–669.8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tjong, S.C. Recent progress in the development and properties of novel metal matrix nanocomposites reinforced with carbon nanotubes and graphene nanosheets. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2013, 74, 281–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, A.; Bisht, A.; Lahiri, D.; Zhang, C.; Agarwal, A. Graphene reinforced metal and ceramic matrix composites: A review. Int. Mater. Rev. 2017, 62, 241–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yang, L.; Zhu, D.; Wang, H.; Chen, T.; Chu, C.; Jiang, Z. Effect of graphene sheet diameter on the microstructure and properties of copper-plated graphene-reinforced 6061-aluminum matrix composites. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 28, 3286–3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Guo, L.; Lin, W.; Chen, J.; Liu, C.; Chen, S.; Zhang, S.; Zhen, T. Effect of the graphene content on the microstructures and properties of graphene/aluminum composites. New Carbon Mater. 2019, 34, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).