An Integrated Experimental-Numerical Study on the Thermal History-Graded Microstructure and Properties in Laser-Clad Carburized Gear Steel

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

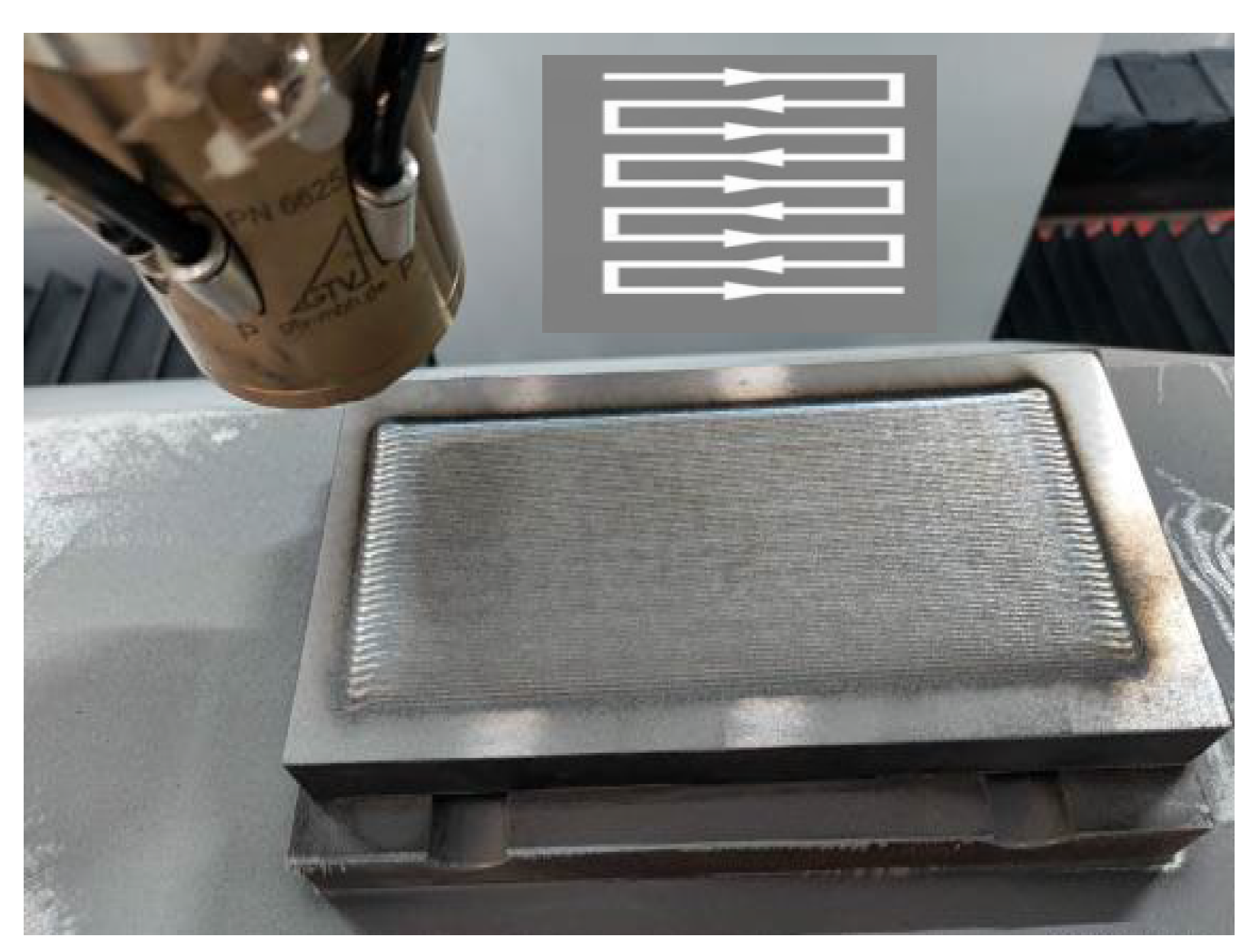

2.1. Equipment, Process and Materials

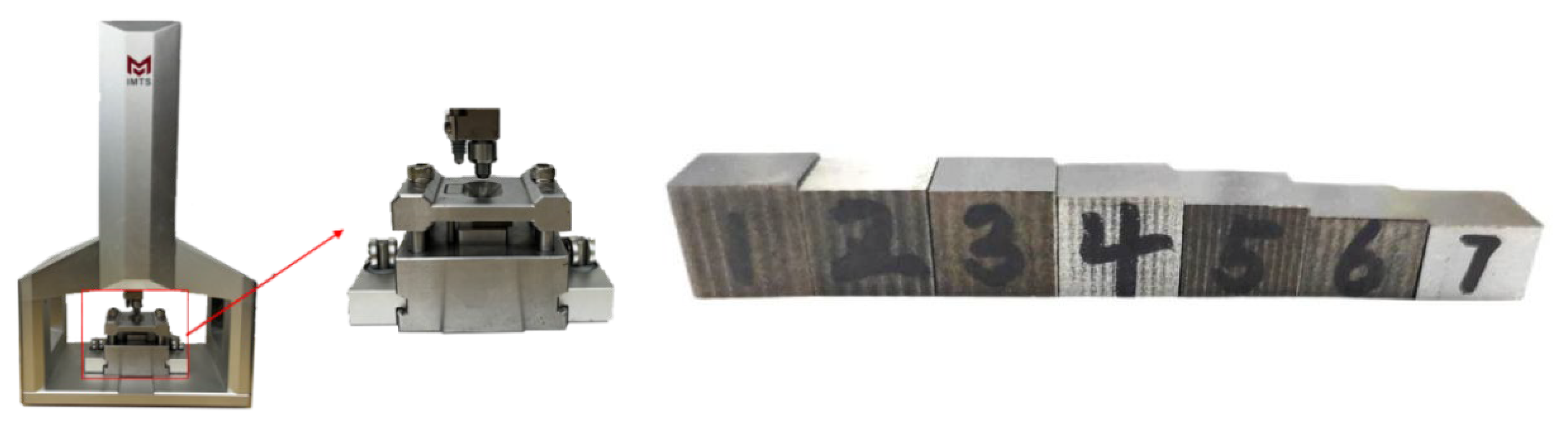

2.2. Performance Characterization

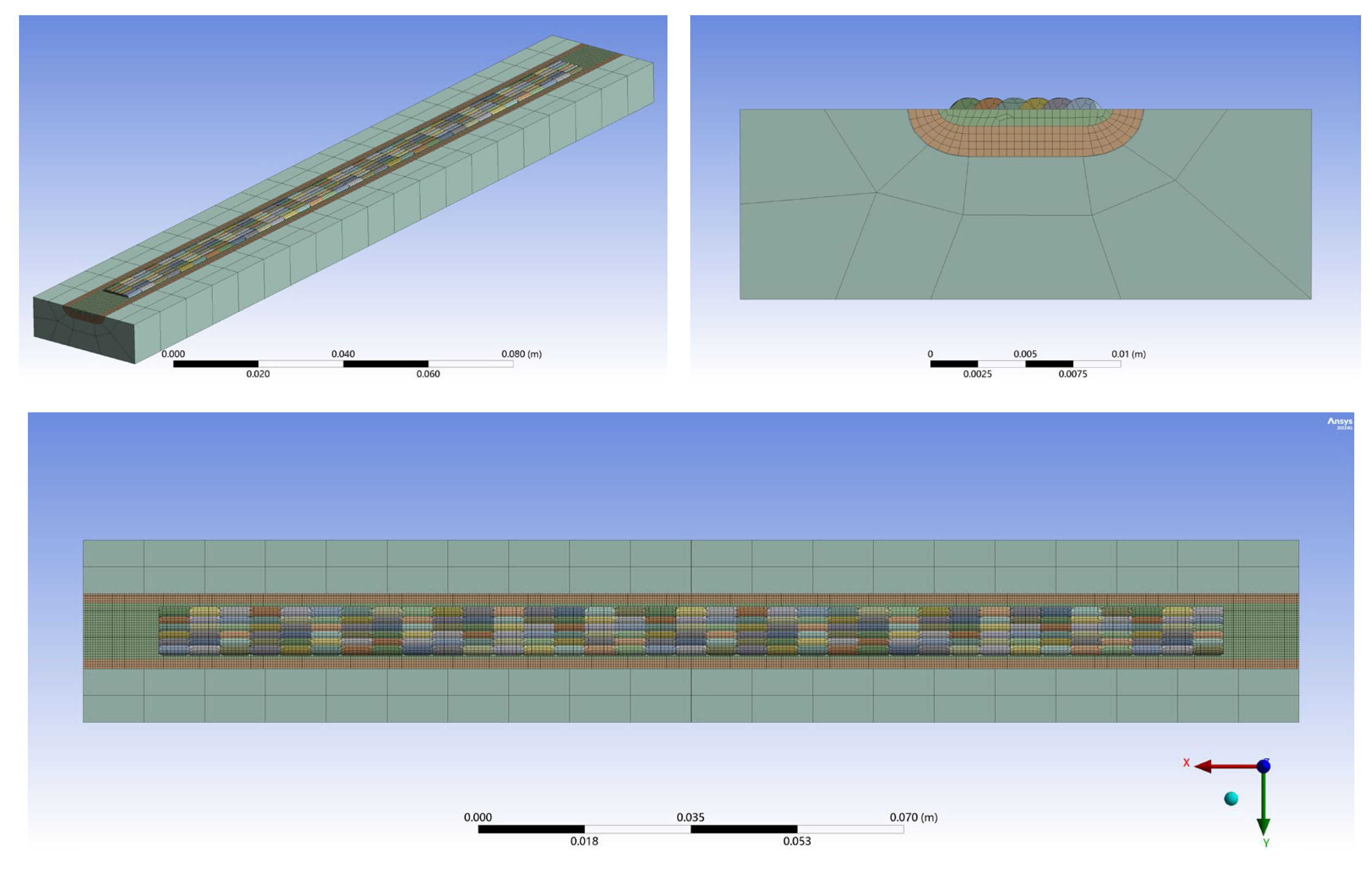

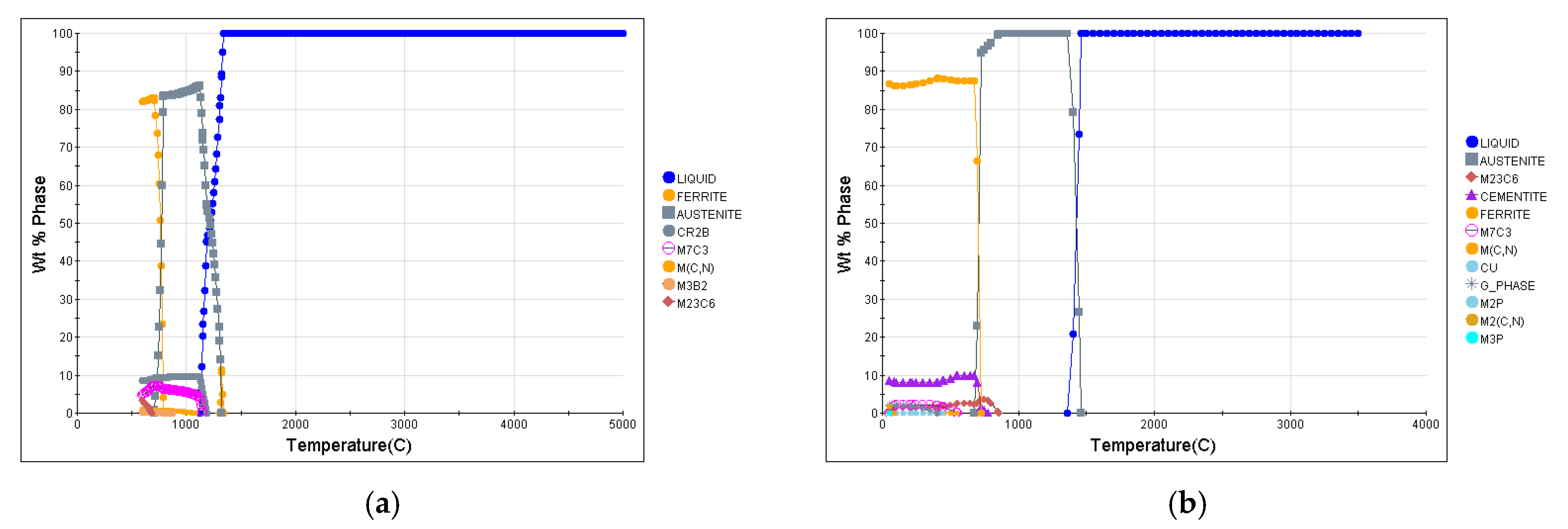

2.3. Thermal Simulation Analysis

- The fluid flow of molten pool, chemical reactions, heat loss due to evaporation, and heat transfer of unmolten powders were ignored. This may affect the residual stress predictions, but Ref. [33] states the model remains reliable for temperature evolution.

- Heat conduction between the cladding sample and the test table was neglected; only convective and radiative heat transfer between the geometric boundary and the surrounding air was considered [34]. The test bed’s large thermal mass means this neglect has a negligible impact on the cladding’s transient temperature field.

2.3.1. Governing Equations for Heat Transfer and Metallurgical Phase Transformation

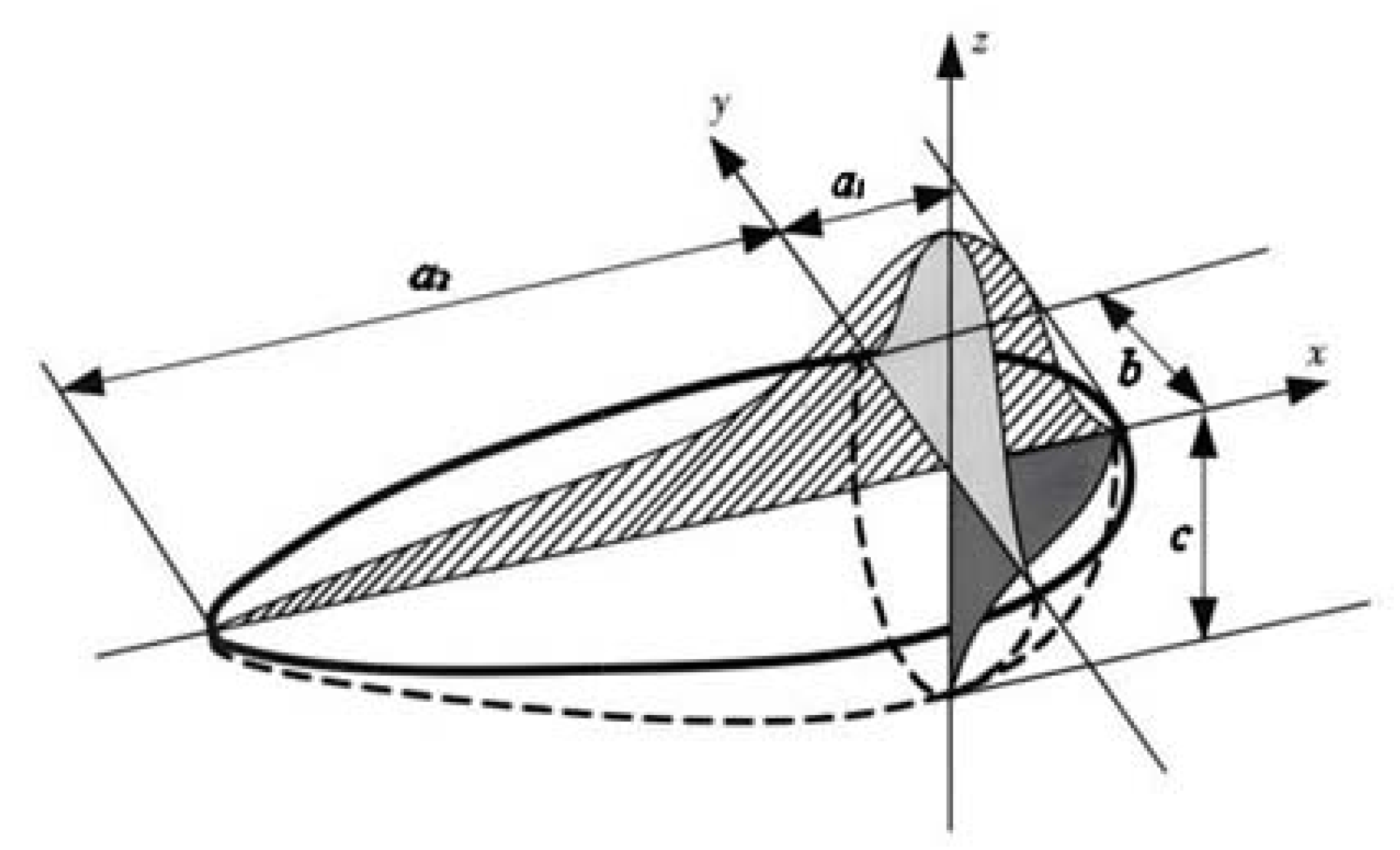

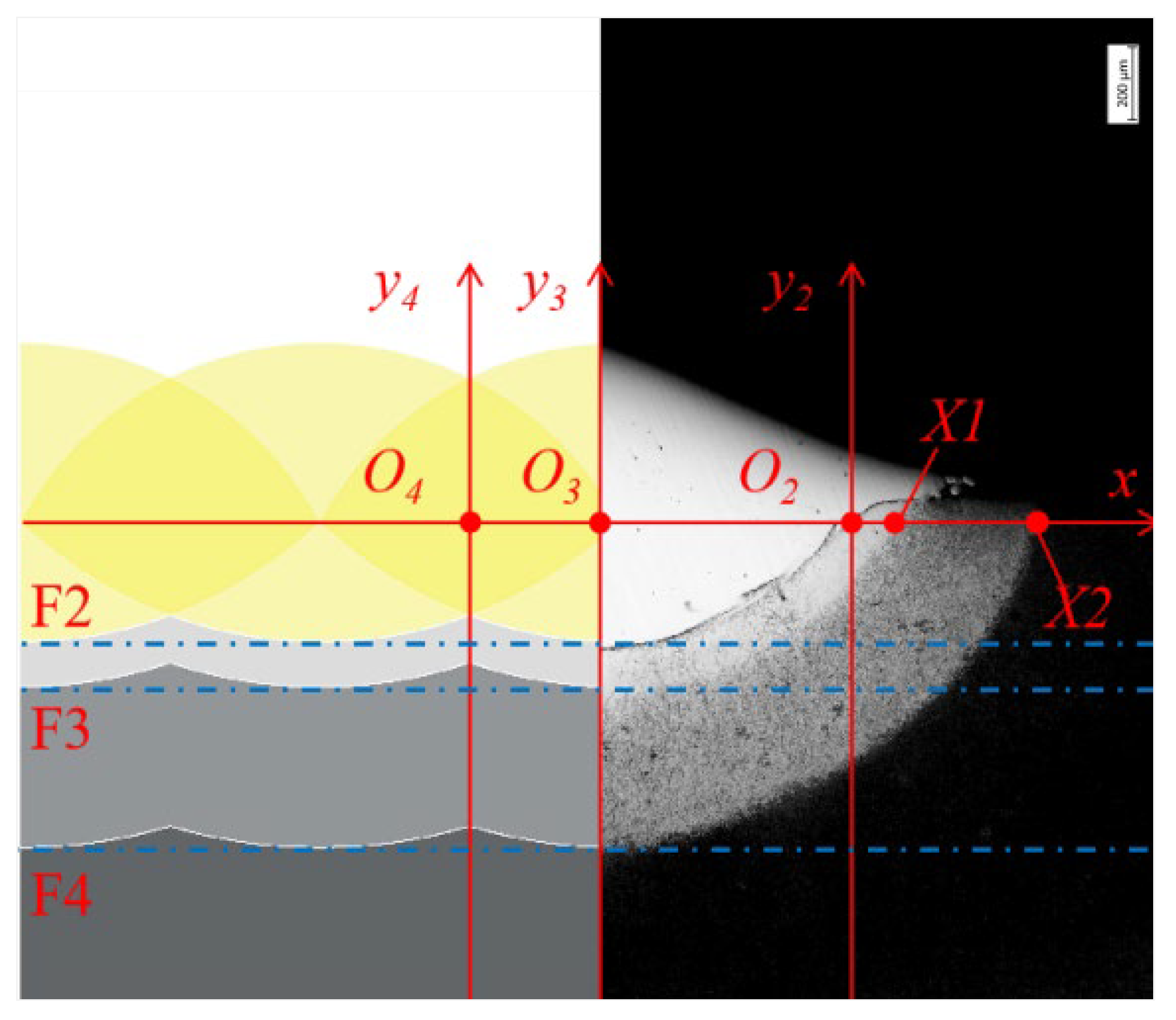

2.3.2. Heat Source Model

2.3.3. Initial and Boundary Conditions

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Surface Morphology

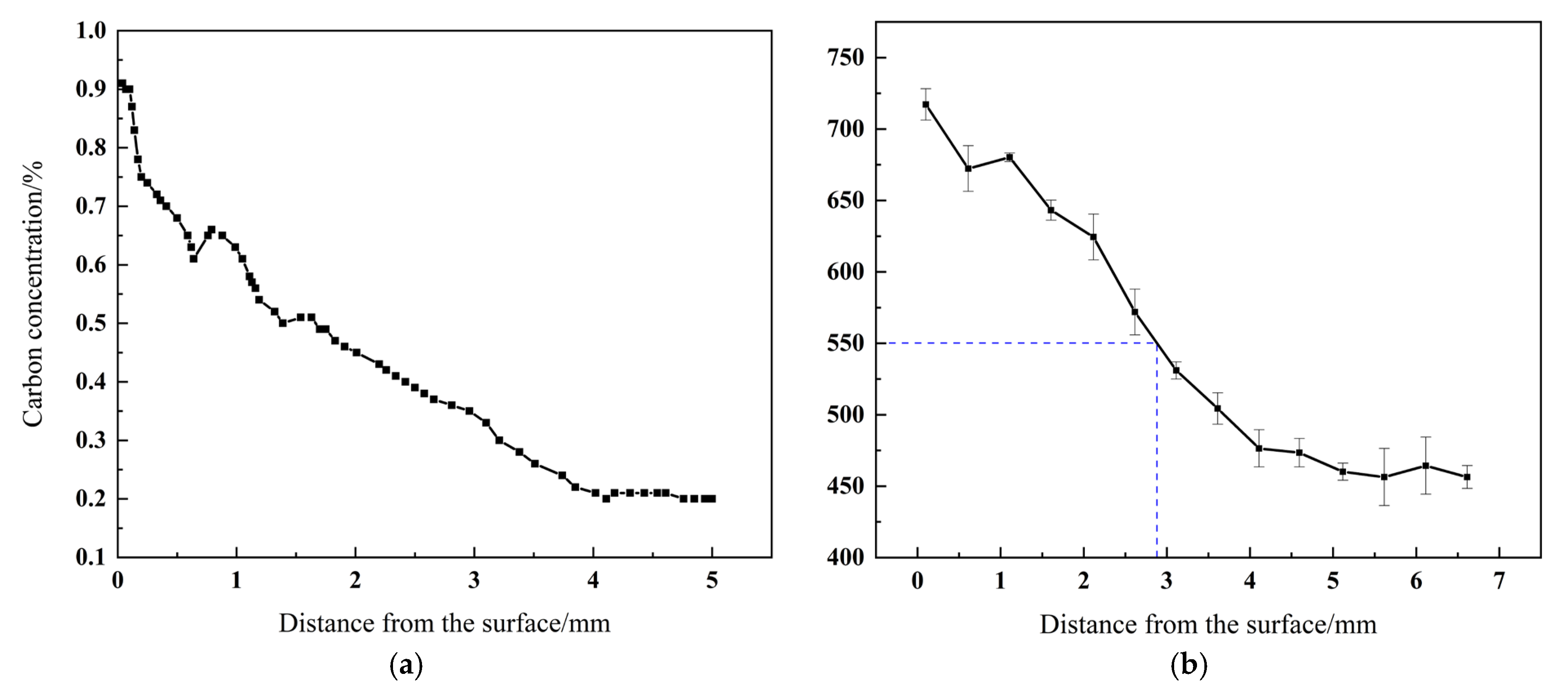

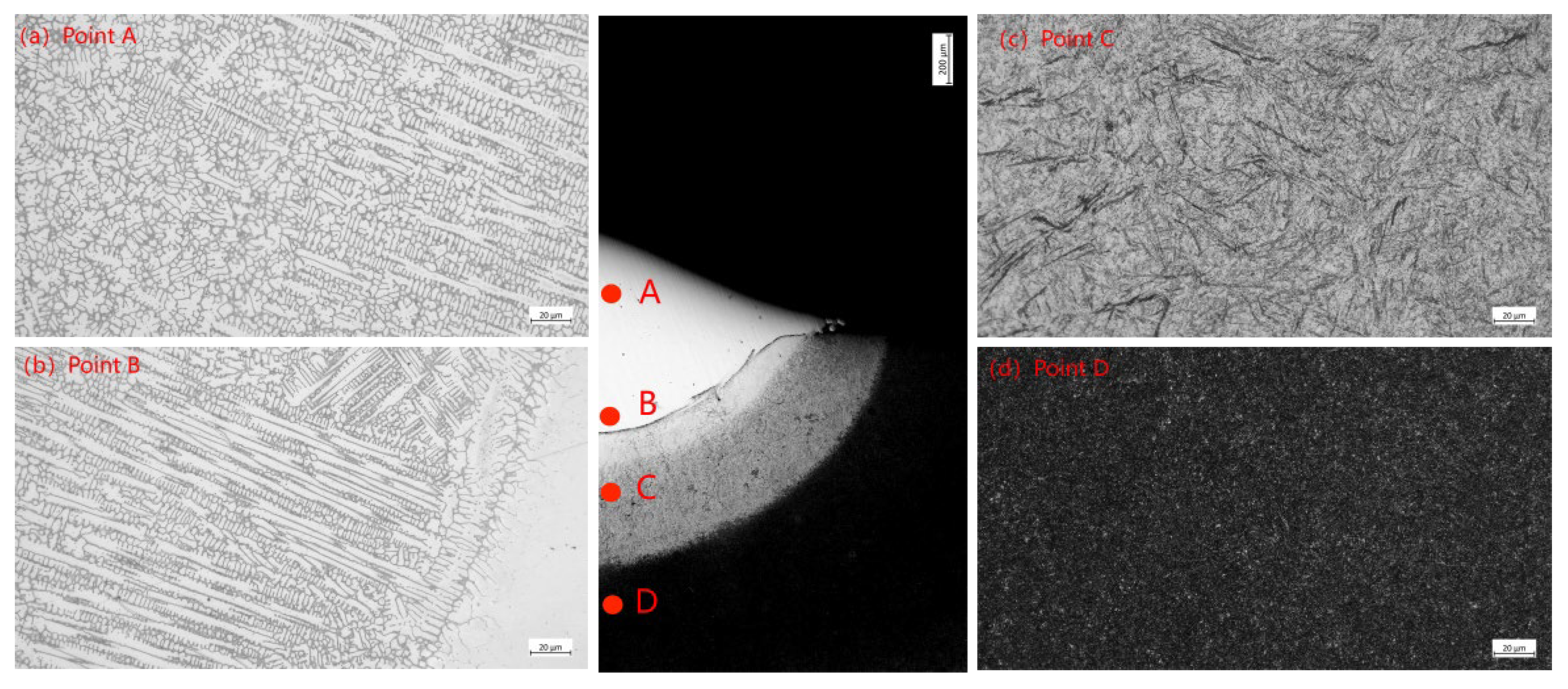

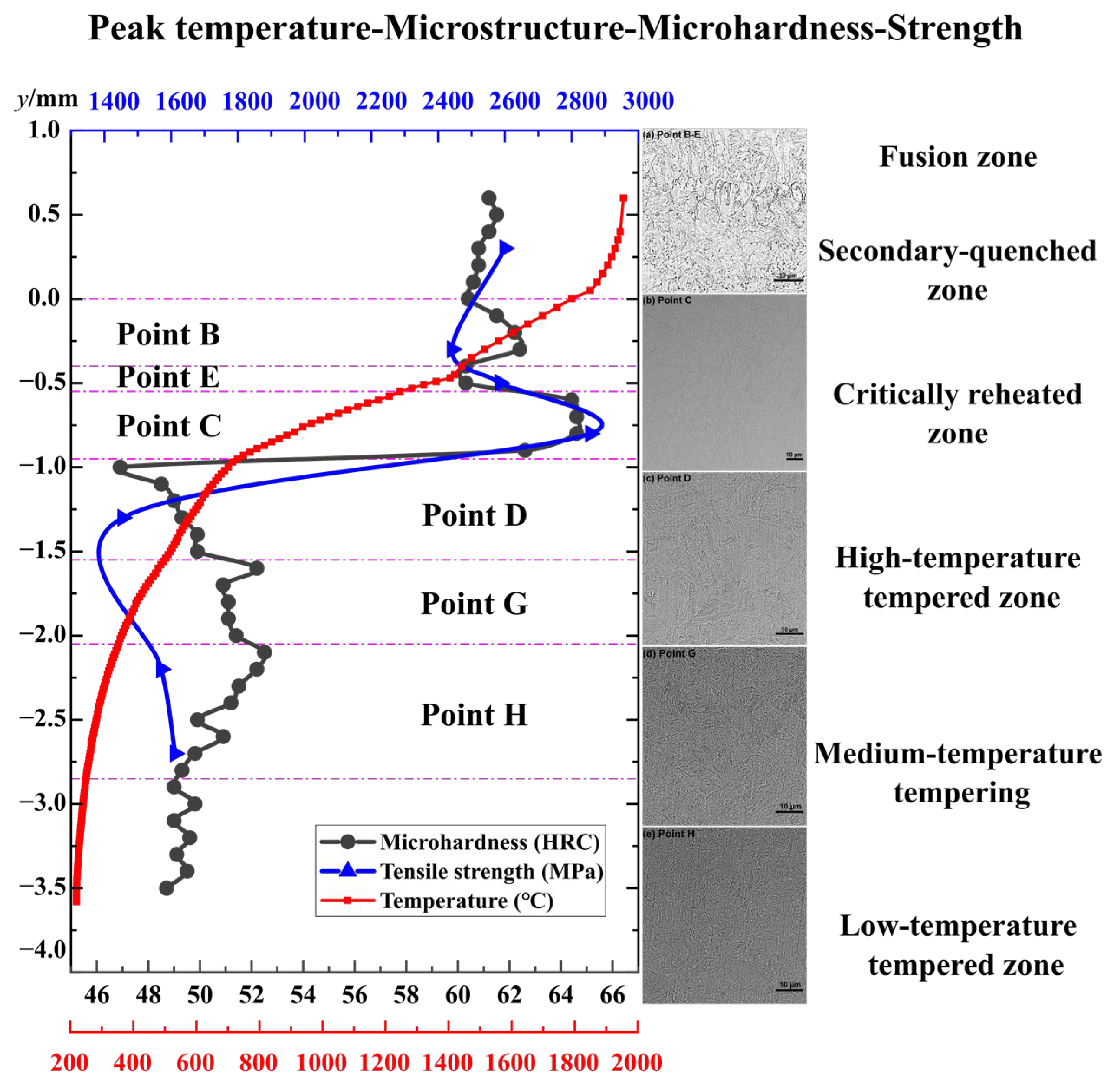

3.2. Microstructures Evolution

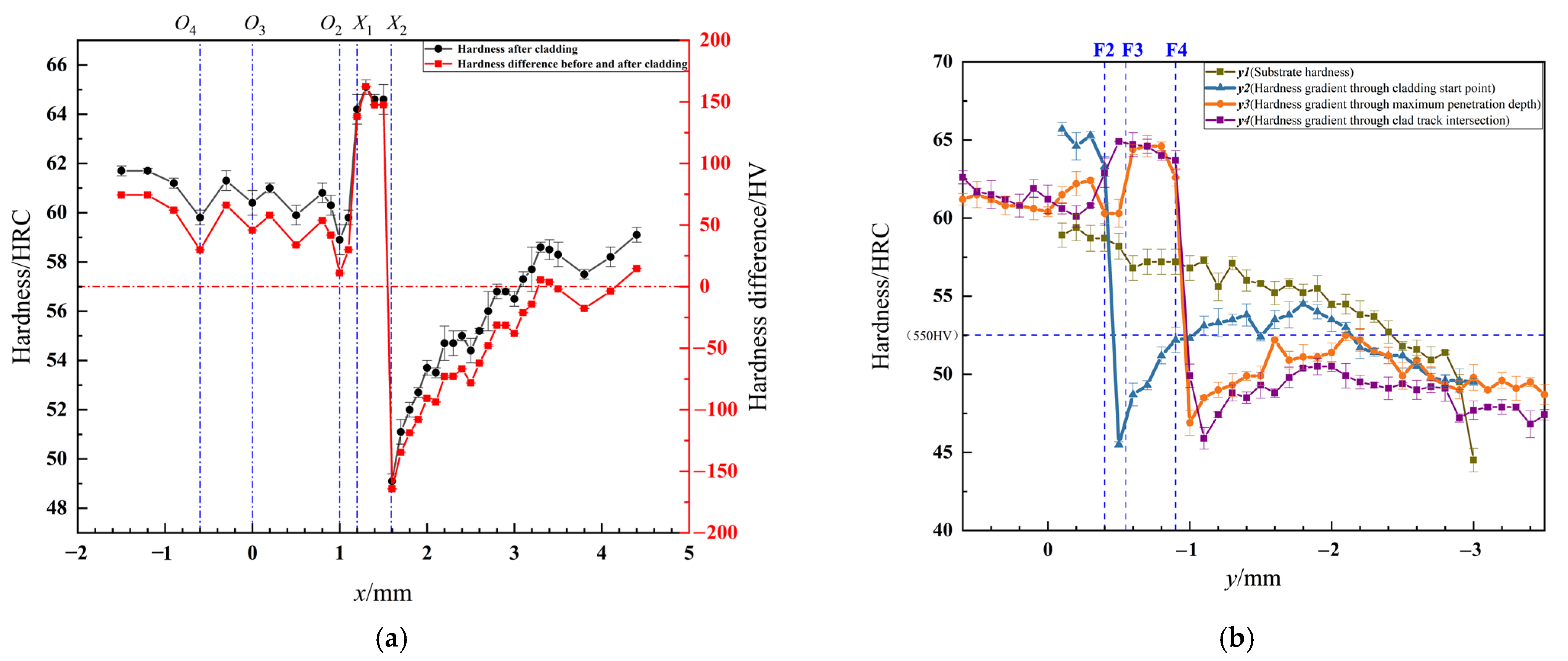

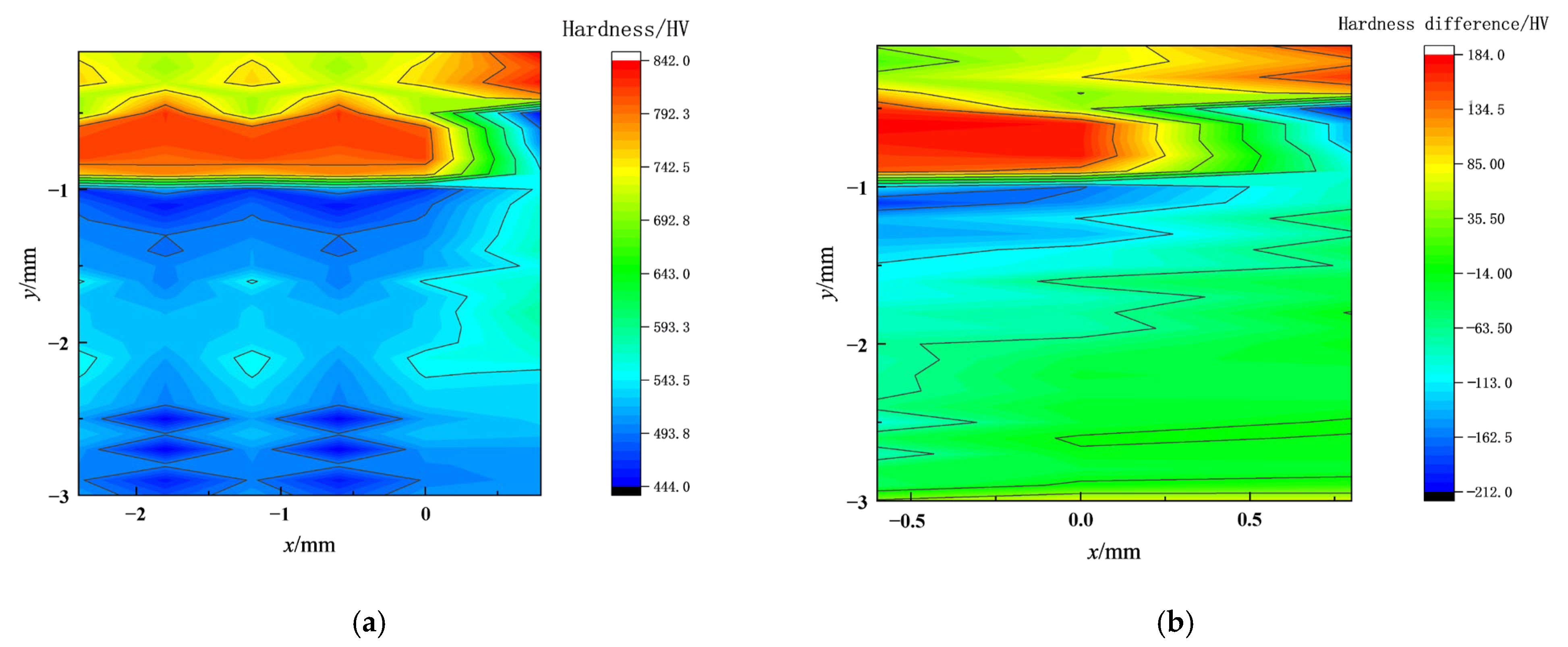

3.3. Microhardness Evolution

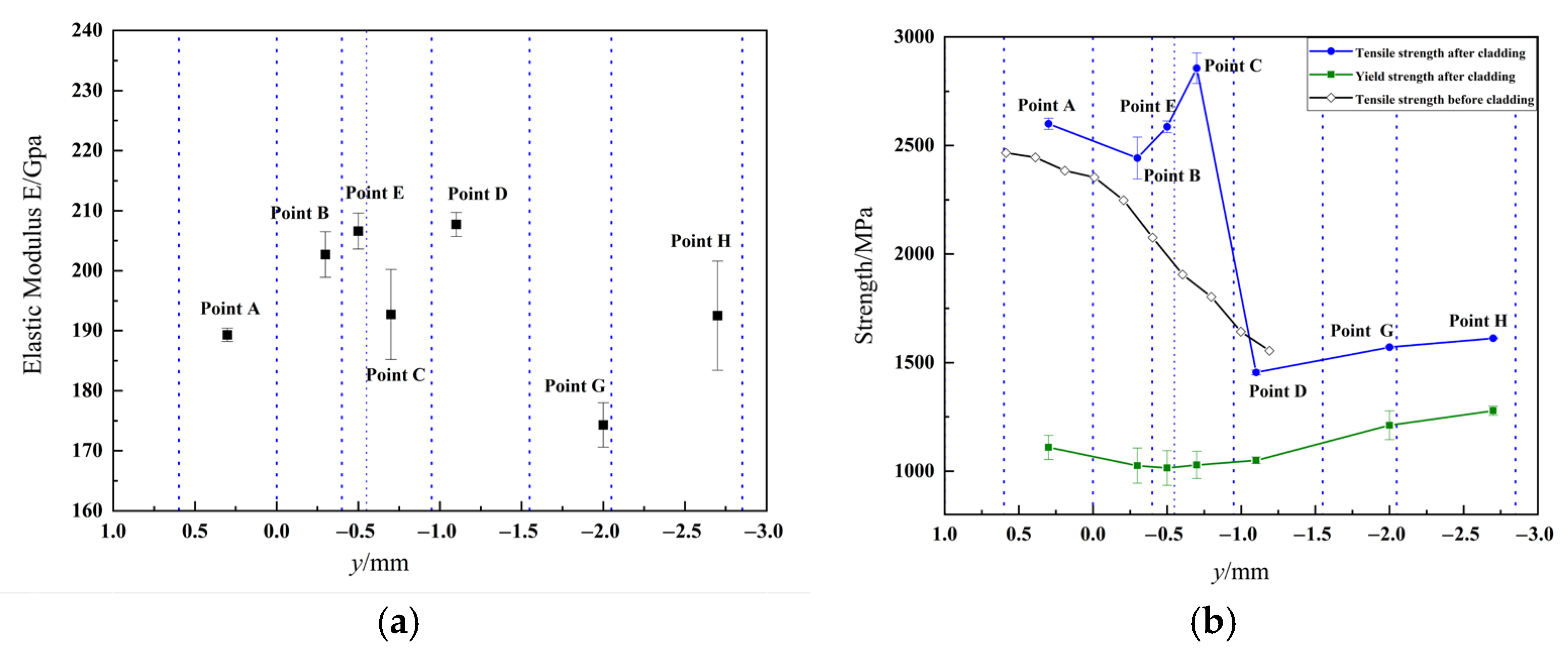

3.4. Mechanical Properties Evolution

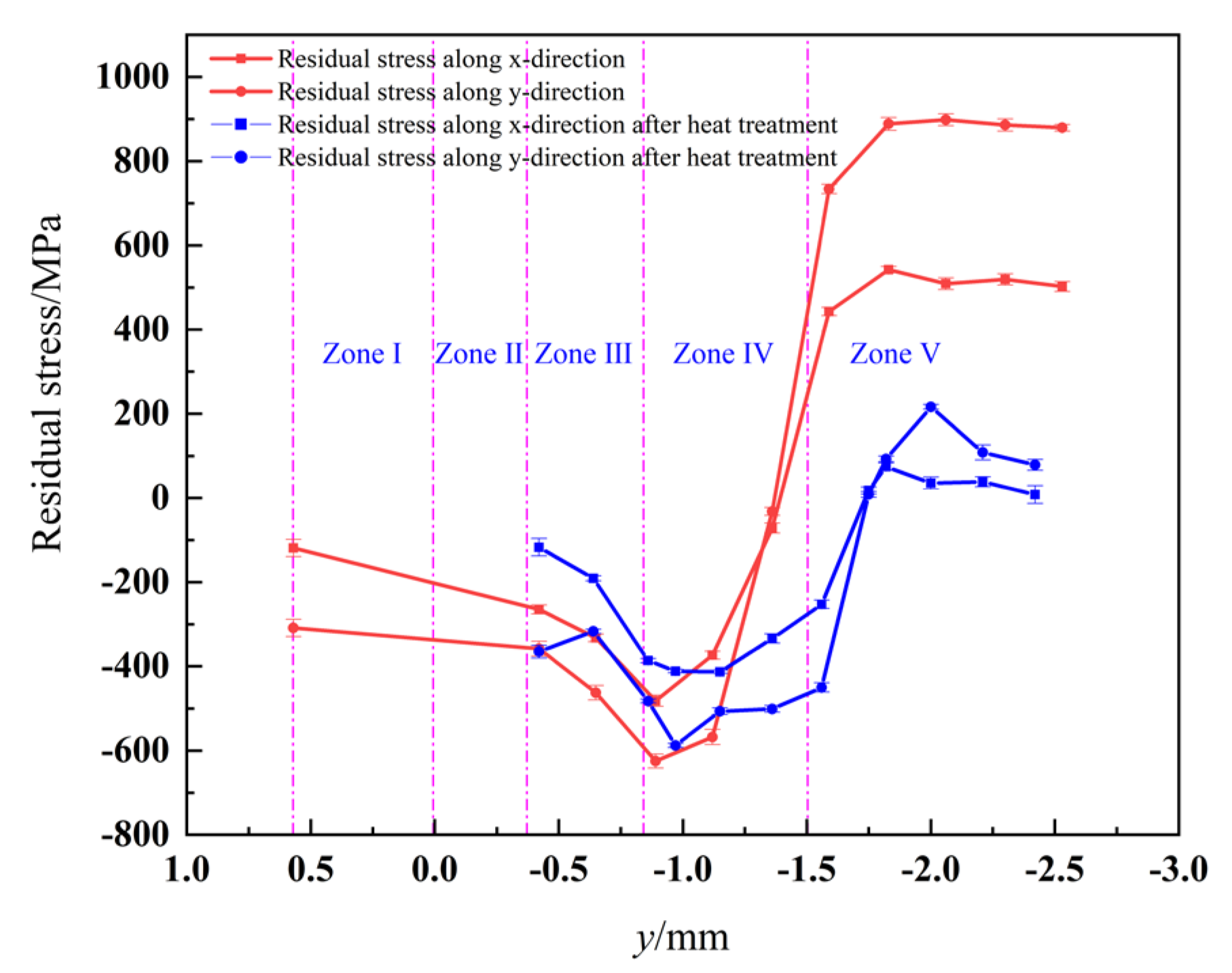

3.5. Residual Stress Testing

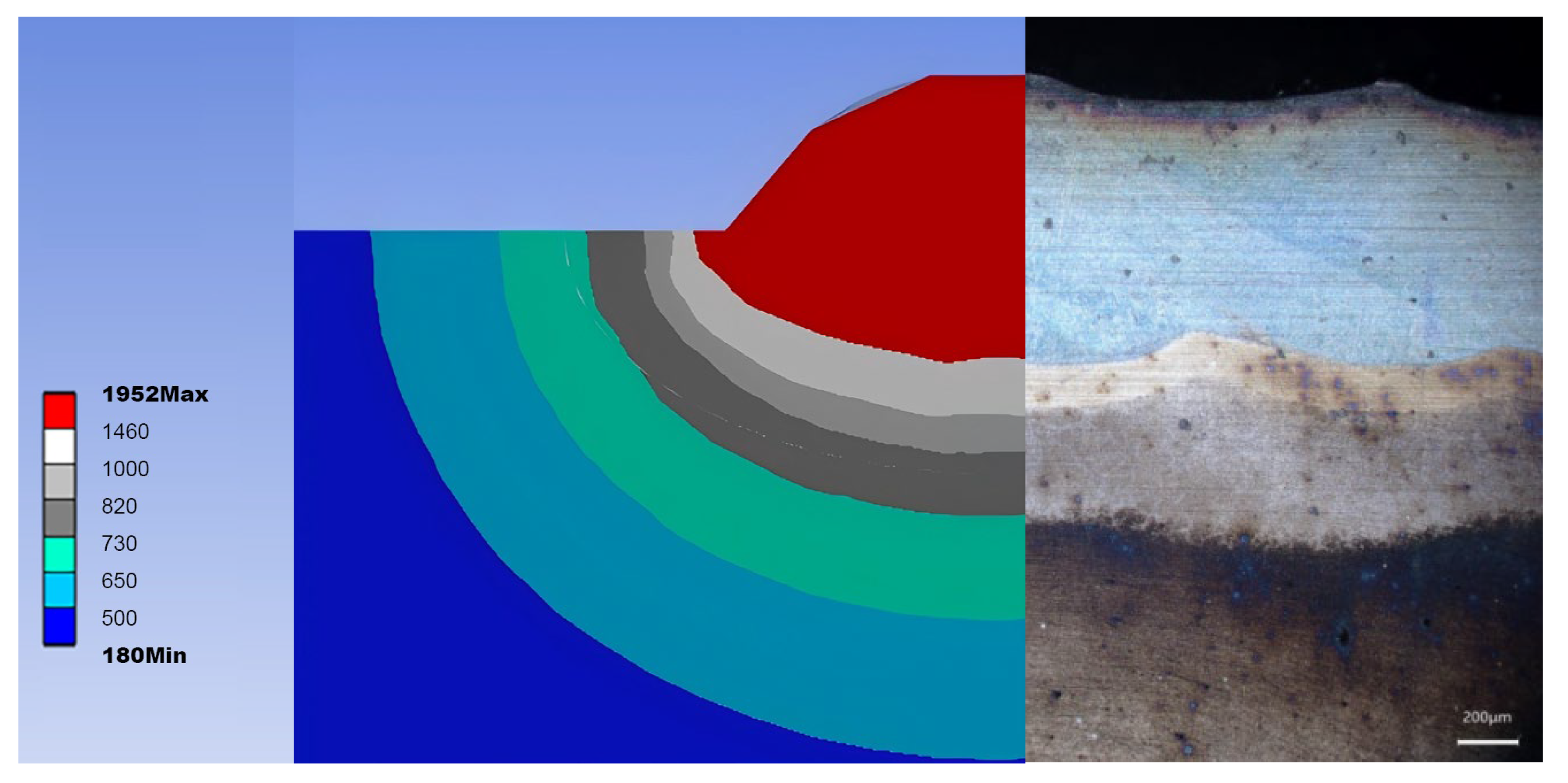

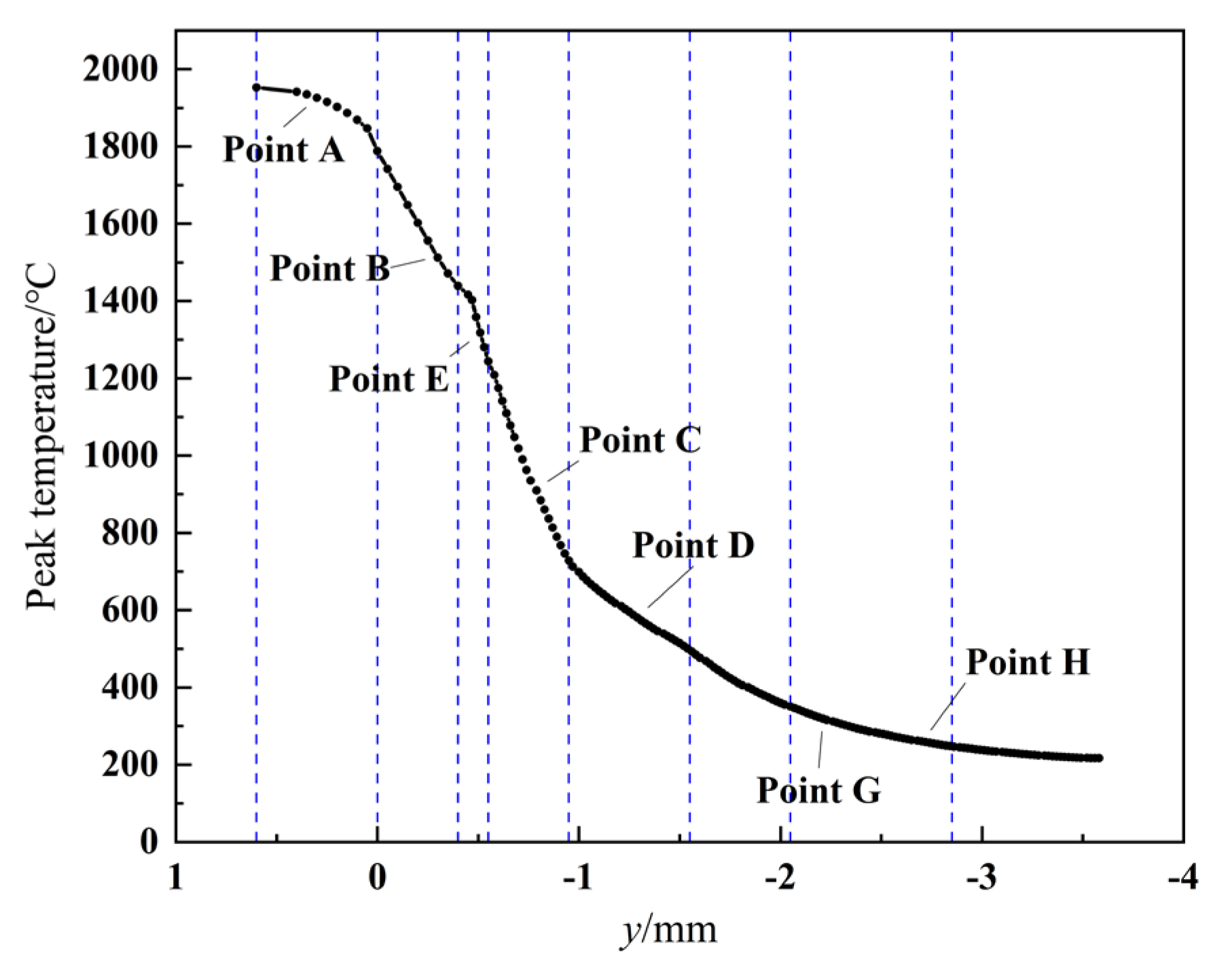

3.6. Thermal Simulation Results

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Laser cladding with an Fe-based alloy produces a gradient hardened layer on carburized gear steel, thereby enhancing the performance of highly loaded gears. This layer comprises two distinct zones: a critically reheated zone exhibiting superior hardness, attributed to its refined acicular martensite, and a secondary-quenched zone consisting of fresh lath martensite. The repaired region consequently achieved hardness and tensile strength surpassing those of the original carburized substrate and outperformed Ni-based repair systems Ref. [10], demonstrating the efficacy of this laser-cladding repair strategy.

- (2)

- We developed and validated a coupled numerical–experimental framework that combines a double-ellipsoidal heat source with phase-transformation kinetics. The model explicitly links the thermal history to the spatial extent of the microstructural zones and achieves high predictive accuracy. It also captures the key temperature regimes responsible for secondary quenching, thereby providing insight into transient thermal phenomena that are difficult to access experimentally.

- (3)

- This work uniquely combined finite-element simulations, microstructural characterization, and flat indentation testing to establish a quantitative causal chain among the local thermal history, phase transformations, microstructure, and mechanical properties. The measured gradients in elastic modulus and hardness across the heat-affected zone agreed with the simulated thermal fields and predicted phase distributions, confirming the link between the thermal simulations and the localized mechanical response.

- (4)

- The validated thermal–metallurgical model serves as a predictive tool for process and performance optimization. It enables accurate prediction of hardened-layer characteristics and identifies the high-temperature tempering–softening zone as the critical region for potential property degradation, providing a basis for tailoring cladding parameters and assessing the service life of repaired gears. Future work will include fatigue testing and further process optimization to evaluate how these relationships translate into long-term service performance.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Cheng, G.; Tao, Q. Low-Temperature Tempering to Tailor Microstructure, Mechanical and Contact Fatigue Performance in the Carburized Layer of an Alloy Steel for Heavy-Duty Gears. Metals 2025, 15, 934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, T.; Kubota, M.; Yoshida, S. Effect of Si concentration on carbon concentration in surface layer after gas carburizing. ISIJ Int. 2016, 56, 1638–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohrbacher, H. Metallurgical concepts for optimized processing and properties of carburizing steel. Adv. Manuf. 2016, 4, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, H.; Zhu, C.; Tang, J.; Jiang, C. Evaluation of contact fatigue risk of a carburized gear considering gradients of mechanical properties. Friction 2020, 8, 1039–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedr, M.; Hamada, A.; Järvenpää, A.; Elkatatny, S.; Abd-Elaziem, W. Review on the solid-state welding of steels: Diffusion bonding and friction stir welding processes. Metals 2022, 13, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Wang, K.; Fu, H. Laser cladding in situ carbide-reinforced iron-based alloy coating: A review. Metals 2024, 14, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.; Zhou, K.; Chen, Z.; Gao, Y. Research progress on laser cladding alloying and composite processing of steel materials. Metals 2022, 12, 2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, T.; Huang, F.; Qian, X.; Zhan, W. The microstructure and properties of laser-cladded Ni-based and co-based alloys on 316L stainless steel. Metals 2024, 14, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Suo, X.; Liu, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, H. Study on tribological performances of in situ -boriding laser cladding FeCoCrNiMn layers and its implementation in gear repair. Tribol. Int. 2024, 194, 109503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Mi, J.; Shi, L.; Chen, C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, W.; Ding, H. Laser Cladding on Surface of 18CrNiMo7-6 Gear Steel and Its Scuffing Resistance Capacity. Surf. Technol. 2023, 52, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, H.; Qin, H. 35CrMo steel surface by laser cladding Fe-based WC composite coating performance analysis. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Optoelectronic Technology and Application 2014: Laser Materials Processing; and Micro/Nano Technologies, Beijing, China, 13–15 May 2014; p. 92950C. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauss, G. Quench and tempered martensitic steels: Microstructures and performance. Compr. Mater. Process. 2014, 12, 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Kang, N.; Kang, M.; Kim, C. Assessment of heat-affected zone softening of hot-press-formed steel over 2.0 GPa tensile strength with bead-on-plate laser welding. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Hu, Q.; Zeng, X.; Meng, L.; Liu, X.; Xu, G. Effect of intrinsic thermal cycles on the microstructure and mechanical properties of heat affect zones in laser cladding coatings on full-scale rails. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 473, 130032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Shu, X.; Xu, H.; Xu, S.; Zhang, S. Study on the Effect of Laser Power on the Microstructure and Properties of Cladding Stellite 12 Coatings on H13 Steel. Materials 2024, 17, 6098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.-L.; Sun, A.-D.; Zhai, W.-Z.; Wang, G.-L.; Yan, C.-P. Finite Element Simulation Analysis of Flow Heat Transfer Behavior and Molten Pool Characteristics during 0Cr16Ni5Mo1 Laser Cladding. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, 2186–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Lyu, F.; Zhan, X. Crack Defects and Formation Mechanism of FeCoCrNi High Entropy Alloy Coating on TC4 Titanium Alloy Prepared by Laser Cladding. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 903, 163905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Long, H.; Qiu, C.; Wang, M.; Li, D.; Dong, Z.; Gui, Y. Multi-Objective Optimization of Process Parameters of 45 Steel Laser Cladding Ni60PTA Alloy Powder. Coatings 2022, 12, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Gao, H.; Chen, X.; Liu, Z.; Han, X. Study on Multi-Field Coupled Evolution Mechanism of Laser Irradiated 40Cr Steel Quenching Process Based on Phase Change Induced Plasticity. Met. Mater. Int. 2022, 28, 1919–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, K.; Zhong, C.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Nie, B.; Xue, Y.; Gui, W.; Luan, B. Effect of multiple thermal cycling on the microstructure and microhardness of Inconel 625 by high-speed laser cladding. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 1093–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Qian, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, P.; Bian, S.; Zhang, W.; Ke, K.; Zhang, B.; Zheng, X.; Yuan, Q. Synergistic enhancement of microstructure and properties in 304/TC4 cold metal transfer joints via laser pre-melting of FeCoNiCr medium-entropy alloys. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 37, 2554–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Liu, Z.; Gong, Y.; Liang, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, X. Analysis of the sequentially coupled thermal–mechanical and cladding geometry of a Ni60A-25%WC laser cladding composite coating. Opt. Laser Technol. 2023, 167, 109595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yu, Z.; Gao, J.; Zhao, J.; Han, X. Numerical Simulation and Experimental Study of Cladding Fe60 on an ASTM 1045 Substrate by Laser Cladding. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 357, 965–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Kovacevic, R. A Thermo-Mechanical Model for Simulating the Temperature and Stress Distribution During Laser Cladding Process. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 102, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anghel, I.-M.; Pascu, A.; Hulka, I.; Woelk, D.H.; Uțu, I.-D.; Mărginean, G. Characterization of Cobalt-Based Composite Multilayer Laser-Cladded Coatings. Crystals 2025, 15, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Wang, C.; Li, C. Microstructures and High-Temperature Mechanical Properties of Inconel 718 Superalloy Fabricated via Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Materials 2024, 17, 3735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aliye, A.; Xiao, Z.; Gao, C.; Shi, W.; Huang, J. Preparation of WC + NbC Particle-Reinforced Ni60-Based Composite Coating by Laser Cladding on Q235 Steel. Coatings 2025, 15, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, X.; Wu, Y.; Liu, H.; Dong, Z.; Hui, X. Effect of Ti Content on Microstructure and Properties of Laser-Clad Fe-Cr-Ni-Nb-Ti Multi-Principal Element Alloy Coatings. Materials 2025, 18, 3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Ding, S.; Xue, X.; Li, M.; Yan, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, D.; Zhang, X.; Chen, S.; Yang, L.; et al. Comparative Study on the Microstructure and Simulation of High-Speed and Conventional Fe-Based Laser-Cladding Coatings. Crystals 2025, 15, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, M.; Hohe, J.; Siegele, D. Numerical Investigations on the Residual Stress Field in a Cladded Plate Due to the Cladding Process. Weld. World 2012, 56, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, A.; Schimmel, J.; Bosman, M.; Goulas, C.; Popovich, V.; Hermans, M.J.M. Fabrication of Low Thermal Expansion Fe–Ni Alloys by in-Situ Alloying Using Twin-Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing. Mater. Des. 2024, 240, 112837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, P.; Liu, Z.-M. Numerical Studies on the Parameter Effect and Controlling Method of the Residual Stress in the Remanufactured 17CrNiMo6 Heavy-Duty Gear by the Laser Cladding Deposition. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 130, 887–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wu, C.; Hao, Y.; Xu, X.; Guo, L. Numerical Simulation and Experimental Investigation on Three-Dimensional Modelling of Single-Track Geometry and Temperature Evolution by Laser Cladding. Opt. Laser Technol. 2020, 129, 106287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Wang, C.; Zhou, Q.; Shao, X.; Shu, L.; Li, X. Optimization of laser welding process parameters of stainless steel 316L using FEM, kriging and NSGA-II. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2016, 99, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kik, T. Heat source models in numerical simulations of laser welding. Materials 2020, 13, 2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kik, T.; Moravec, J.; Novakova, I. New method of processing heat treatment experiments with numerical simulation support. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 227, 12069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Li, C.; Guo, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, X.; Feng, X. Modeling of temperature distribution and clad geometry of the molten pool during laser cladding of TiAlSi alloys. Opt. Laser Technol. 2021, 142, 107277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Liu, M.; Li, Z.; Li, H.; Shen, J. Influence of Different Heat Source Models on Calculated Temperature Field in Selective Laser Melting of 18Ni300. Chin. J. Lasers 2021, 48, 52–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hocine, S.; Van Swygenhoven, H.; Van Petegem, S. Verification of selective laser melting heat source models with operando X-ray diffraction data. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 37, 101747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Zhu, G.; Li, J.; Xie, G.; Wang, L.; Shi, S. Research Progress in Numerical Simulation of Temperature Field and Flow Field in Laser Cladding Molten Pool. Surf. Technol. 2023, 52, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Yu, G.; He, X.; Li, S.; Chen, R.; Zhao, Y. Grain size evolution under different cooling rate in laser additive manufacturing of superalloy. Opt. Laser Technol. 2019, 119, 105662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Xie, C.; Liu, J.; Guo, S.; Cui, L. Mechanical and corrosion resistance analysis of laser cladding layer. Sci. Eng. Compos. Mater. 2022, 29, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Kim, Y.-C.; Cho, J.-E.; Yim, C.-H.; Yun, D.-S.; Lee, T.-G.; Park, N.-K.; Chung, R.-H.; Hong, D.-G. Microstructural evolution, hardness and wear resistance of WC-Co-Ni composite coatings fabricated by laser cladding. Materials 2024, 17, 2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Huang, Y.; Zeng, X.; Hu, Q. Microstructure characteristics of Ni-based WC composite coatings by laser induction hybrid rapid cladding. Mater Sci. Eng. A 2008, 480, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlock, D.K.; Bräutigam, V.E.; Speer, J.G. Application of the quenching and partitioning (Q&P) process to a medium-carbon, high-Si microalloyed bar steel. Mater. Sci. Forum 2003, 426–432, 1089–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Hao, M.; Qiao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhao, M. Characterization of elastic-plastic properties of surface-modified layers introduced by carburizing. Mech. Mater. 2020, 144, 103364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Laser Power (W) | Scanning Speed (mm/s) | Powder Feed Rate (mg/s) | Spot Diameter (mm) | Overlap Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4500 | 75 | 500 | 3 | 60% |

| Material | C | Cr | Ni | Mo | Mn | Si | p | S | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18CrNiMo7-6 | Varied with depth (see Figure 3a) | 1.8 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 0.76 | 0.29 | 0.0072 | <0.002 | Balance |

| Material | C | B | Cr | Ni | Mo | Mn | Si | V | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHT.22.A01 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 15.5 | 1.7 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 1.2 | Balance |

| Location | Peak Temperature (°C) | Corresponding Microstructural Zone | Zone Temperature Range (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Point A | 1926 | Clad Zone | 1950–1780 |

| Point B | 1512 | Fusion Zone | 1780–1460 |

| Point E | 1358 | Secondary-quenched zone | 1460–1240 |

| Point C | 1018 | Critically reheated zone | 1240–730 |

| Point D | 650 | High-Temperature Tempering zone | 730–500 |

| Point G | 360 | Medium-Temperature Tempering zone | 500–350 |

| Point H | 260 | Low-Temperature Tempering zone | 350–150 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, Y.; Zheng, P.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, L.; Zhang, H.; Du, L. An Integrated Experimental-Numerical Study on the Thermal History-Graded Microstructure and Properties in Laser-Clad Carburized Gear Steel. Coatings 2025, 15, 1467. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121467

Xu Y, Zheng P, Liu Z, Zhang Z, Shi L, Zhang H, Du L. An Integrated Experimental-Numerical Study on the Thermal History-Graded Microstructure and Properties in Laser-Clad Carburized Gear Steel. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1467. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121467

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Yingjie, Peng Zheng, Zhongming Liu, Zhihong Zhang, Lubing Shi, Heng Zhang, and Linfan Du. 2025. "An Integrated Experimental-Numerical Study on the Thermal History-Graded Microstructure and Properties in Laser-Clad Carburized Gear Steel" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1467. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121467

APA StyleXu, Y., Zheng, P., Liu, Z., Zhang, Z., Shi, L., Zhang, H., & Du, L. (2025). An Integrated Experimental-Numerical Study on the Thermal History-Graded Microstructure and Properties in Laser-Clad Carburized Gear Steel. Coatings, 15(12), 1467. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121467