Abstract

To address the issues of low efficiency and poor reliability associated with current manufacturing processes like welding for T-shaped tubes in aircraft, this study proposes a die-less rotary drawing forming process for T-shaped tubes. Finite element simulations combined with experiments were conducted to investigate the influence of four key process parameters-pre-hole size, preheating temperature, feed rate, and rotary drawing speed-on the rotary drawing forming of thin-walled 5A02 aluminum alloy T-shaped tubes. Variations in the effective branch height and wall thickness reduction ratio under different combinations of process parameters were explored. The optimal combination of process parameters was determined based on simulated orthogonal experiments. The optimized results were experimentally validated, and their pressure resistance limit was analyzed through pressure tests. Finally, the microstructural changes in the rotary-drawn material were analyzed using Electron Backscatter Diffraction (EBSD) tests. The results demonstrate that the proposed die-less rotary drawing forming process enables the local integrated forming of thin-walled 5A02 aluminum alloy T-shaped tubes. A branch height exceeding 3.5 mm and a maximum wall thickness reduction ratio of approximately 18% were achieved. The pressure withstand limit reaches 7 MPa, satisfying the engineering requirement of 6.4 MPa.

1. Introduction

The tube system of aerospace equipment is responsible for transporting media such as oil and gas, and is the “lifeline” of aerospace vehicles [1,2]. Due to the functional requirements and space constraints of aerospace vehicles, their tube systems are often designed with compact and complex layouts, which necessitates the use of many thin-walled tee or multi-pass tube connection components. For the forming of T-shaped tubes, the aerospace industry often adopts mechanical processing, sheet metal stamping half-tube welding [3], internal high-pressure forming [4], electromagnetic flanging forming [5,6], and drawing forming [7]. Among them, the machining process has problems such as high cost, poor surface quality, and high material loss [8]. The sheet metal stamping half-tube welding process also fails to meet today’s lightweight and high-quality production requirements due to problems such as a long manufacturing cycle, poor reliability, and increased weight from welds. The internal high-pressure forming process is complex and relies on conditions such as pressure paths, axial feed control, and tube lubrication. However, aerospace ducts are mostly made of high-strength aluminum alloys, which have limited plastic deformation capacity and are more prone to defects such as cracking and springback [9]. The electromagnetic flanging forming process is difficult to debug and has high costs for forming equipment. Finally, conventional drawing forming is plagued by inherent limitations, including the cumbersome insertion of steel balls into the manifold and unacceptably high thinning rates. Furthermore, this process is typically restricted to highly ductile materials such as copper tubes. The aforementioned deficiencies of existing processes are critical challenges that the aerospace industry strives to avoid. Therefore, this paper proposes a mold-free rotary drawing type technology for T-shaped tubes. This research paradigm—optimizing product performance by modifying manufacturing processes—has been successfully validated in other material systems. For example, Xie et al. [10] found in their study that plastic deformation can simultaneously optimize the strength and toughness of materials, which highlights the great potential and synergistic effect of plastic forming processes in improving the comprehensive performance of components.

As a digital flexible manufacturing technology, it has attracted much attention in the field of sheet metal forming due to its high flexibility. It can realize the progressive forming of branch tubes with complex three-dimensional curved surfaces, showing great potential in the rapid and economical forming of tube materials for tube systems in automobiles, aerospace and other fields. It is worth noting that its digital process characteristics not only avoid the mold development cycle, but also can flexibly adapt to the personalized needs of different batches of products through parameter adjustment, providing an innovative solution for small-batch and multi-variety production. However, the application of this technology in the field of plastic forming of tubular components is still in the exploration stage.

The rotary drawing technology of tube fittings is a type of incremental forming technology. The incremental forming technology was first proposed by Leszak [11]. As research continues to deepen, incremental forming technology has gradually been applied to the branch forming of tube fittings. Yang Chen, Kefan Liu et al. [12,13] used an optimally designed single-cone rotary head to form 316 stainless steel tube branches without molds, verifying the flexible manufacturing of tube branch forming by the incremental forming method. Gorji et al. [14] conducted an incremental forming flanging branch with AA6061-T6 alloy. The above shows that the incremental forming process can realize the branch flanging of tube fittings. However, Besong et al. [15] found that the paddle-type incremental forming branch with forming points at both ends of the circle diameter has higher flanging height and better performance than the single-point incremental forming branch with forming points at one point on the circle. The die-less rotary drawing technology proposed in this paper also has forming points at both ends of the circle diameter, and its forming effect should be better than that of single-point incremental forming. However, considering that the size of the paddle-type tool head in the paddle-type incremental forming process is larger than that of the prefabricated hole, it is impossible to insert the paddle-type tool head into long curved tubes or already formed pipe fittings, making it unable to achieve flanging from the inside to the outside of the tube. Therefore, this paper proposes a rotary drawing technology to make up for the deficiencies of existing methods, and this technology holds significant research value.

This paper outlines the rotary drawing forming process for aviation 5A02 aluminum alloy T-tubes, and conducts finite element simulation, tooling fixture design, and forming experimental research to explore the forming limit and optimal process parameters of this technology for forming T-tubes. Finally, the strength of the T-tubes formed by this technology is tested through aviation tube burst failure analysis experiments. The aim is to explore a high-quality and efficient processing technology for aviation tube branches.

2. Overview of Process Method

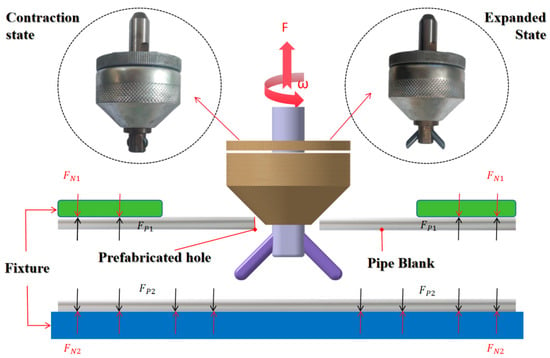

2.1. Characteristics of Die-Less Rotary Drawing Forming

The die-less rotary drawing forming process can be divided into two main stages: drilling a prefabricated hole and rotary drawing the branch tube. The process of rotary drawing the branch tube is shown in Figure 1. The tube blank is fixed with a fixture, and the forming area of the rotary head is placed inside the tube blank through the prefabricated hole using a contracted rotary head. Then the rotary head expands to the predetermined inner diameter of the branch tube for rotary drawing, and the forming area gradually fits the tube wall to complete the forming of the branch tube. In the figure,

and

denote the acting forces exerted by the fixture on the tube blank;

and

denote the reaction forces exerted by the tube blank on the fixture;

represents the direction of vertical movement of the rotary head; and

represents the rotational motion of the rotary head.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of mold-free rotational pull-forming of T-shaped tubes.

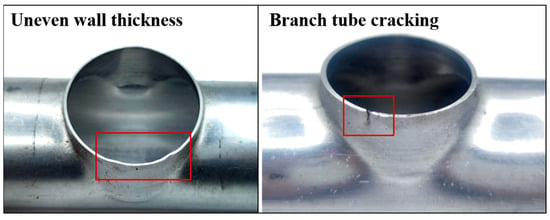

Although this method does not require molds, the quality of the formed T-shaped tubes varies depending on process parameters such as prefabricated hole size, preprocessing temperature of the tube blank, vertical feed rate, and rotary drawing speed. Common forming defects of T-shaped tubes processed by this method include uneven wall thickness and cracks, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Common defects of T-tube formed by rotary drawing type without mold.

2.2. Calculation of Prefabricated Hole

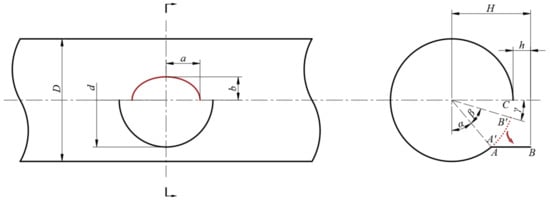

When shell hole drawing is performed, a prefabricated hole must first be made, which is generally an elliptical hole. The size of the prefabricated hole is a crucial factor for successful hole flanging and directly affects the hole flanging quality [16]. Since the rotary drawing process does not require feeding at both ends and only involves local forming of the tube material, the size of the prefabricated hole is particularly important. When the branch tube height is not high, the rotary drawing height is approximately calculated by the unfolded length of material bending.

According to the equal line length method [13], the shape of the prefabricated hole is elliptical, with the major axis located in the circumferential direction of the ring and the minor axis located in the circumferential direction of the tube blank [17]. As shown in Figure 3. Since the size of the inner diameter generatrix in the deformation zone of the tube blank remains unchanged before and after the rotary drawing process, and flanging forming is achieved only through material thinning, the preformed hole size can be calculated based on the geometric relationship of the central plane of the tube before and after deformation. By performing geometric analysis on the model according to the equal line length theory, Equations (1)–(4) are obtained; Equation (5) is then derived through mathematical solution.

Figure 3.

The geometric relationship between prefabricated hole dimensions and tube neutral surface.

In the formula, a is the major axis of the elliptical prefabricated hole, b is the minor axis, d is the diameter of the neutral surface of the branch tube, D is the diameter of the neutral surface of the mother tube, and h is the forming height of the branch tube. When the predetermined parameters D, d, and h are designed, the size of the prefabricated hole can be determined. However, the branch pipe height and wall thickness of T-shaped tubes are influenced by multiple factors, such as pre-drilled hole size and feed rate. Therefore, it is necessary to explore the optimal combination of the forming height and wall thickness of the branch tube, and the specific size of the prefabricated hole needs further experimental investigation.

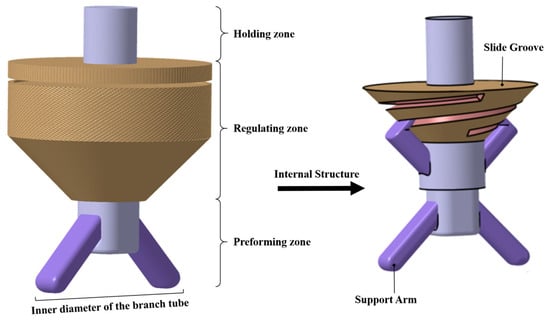

2.3. Experimental Equipment

Branch pipe rotary drawing requires the use of a telescopic rotary drawing tool, as shown in Figure 4. This rotary drawing tool consists of three parts: clamping area, adjustment area, and forming area. Its forming area is a telescopic double support arm. By rotating the adjustment area to drive the rotation of the slide groove, the support arms are extended or retracted to achieve the setting of the rotary drawing inner diameter.

Figure 4.

Telescopic rotary drawing tool.

After the rotary drawing process, to facilitate subsequent industrial applications such as welding of the branch tube, the end face of the branch tube needs to be flattened. However, this paper aims to study the influence of various process parameters on the rotary drawing height and wall thickness of the branch tube under this process. Additionally, since milling the formed port flat is an experimental step, no further milling operations are required after the rotary drawing forming of the branch tube. The die-less drawing experiment was conducted on a three-axis CNC milling machine, as shown in Figure 5. The equipment is equipped with high-precision positioning and stable processing capabilities, which can ensure the controllability of parameters during the rotary drawing process. Additionally, this equipment serves only as a driving platform for the rotary drawing forming tool rather than a subtractive tool. Figure 6 shows the experimental fixture, which is designed to ensure the tube is firmly fixed and prevent displacement during rotary drawing.

Figure 5.

Three-axis CNC milling machine.

Figure 6.

Die-less rotary pulling fixture.

During the experiment, the feed rate of the rotary drawing tool and the spindle speed were adjusted via the CNC programming program, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Rotary drawing processing control platform.

3. Finite Element Simulation Analysis of T-Shaped Tube Rotary Drawing Forming

3.1. Abaqus Finite Element Modeling

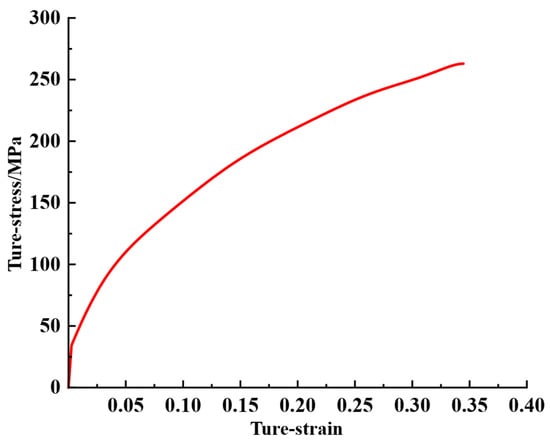

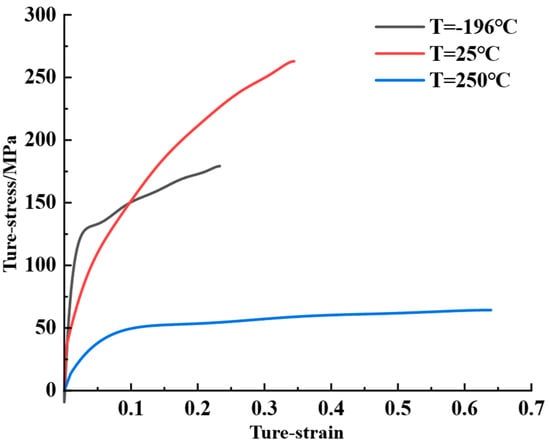

This study uses 5A02 aluminum alloy O-state thin-walled tubes for aviation with an inner diameter of Φ 40 mm and a wall thickness of 1 mm as the research object. To ensure the accuracy of the finite element simulation, the engineering stress–strain curve of 5A02 aluminum alloy material was obtained through uniaxial tension. The true stress–strain curve obtained after calculation is shown in Figure 8. The tensile rate is 0.005 mm/s. The material parameters are shown in Table 1.

Figure 8.

True stress–strain curve of 5A02 aluminum alloy.

Table 1.

Material parameters of 5A02 aluminum alloy.

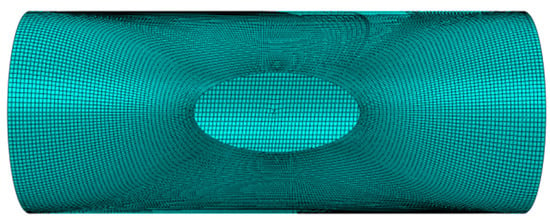

The approximate models of the tube blank and the rotary head were modeled and assembled using CATIA V5R20, then imported into ABAQUS 2021 in IGS format for finite element simulation analysis, converting solid elements into shell elements to simulate the rotary drawing process. Figure 9 shows the model and mesh division of the tube blank, with quadrilateral elements used for the overall division of the tube blank. Local mesh refinement was performed on the edge of the prefabricated hole using edge seeding to ensure calculation accuracy. The finite element approximate model of the rotary head is shown in Figure 10. Dynamic explicit analysis was adopted, and the simulation time was adjusted synchronously with the feed rate. The mass scaling factor is 10,000, and the boundary conditions of this model are as follows: both ends of the tube blank are fully fixed; the spinning head is subject to displacement/rotation constraints to control the vertical drawing movement of its RP reference point and its rotational motion around the vertical axis. Penalty contact is applied between the rotary head and the inner wall of the tube blank, with a friction coefficient of 0.1. The approximate model of the rotary head was divided into elements using triangular meshes with a mesh size of 0.2. The rotary head was defined as a rigid body, and the tube blank was defined as a deformable body. The element types of each component of the model are shown in Table 2.

Figure 9.

Meshing of the tube blank model.

Figure 10.

Meshing for the simplified rotary head model. The yellow RP is the reference point of the model.

Table 2.

Element type of the model.

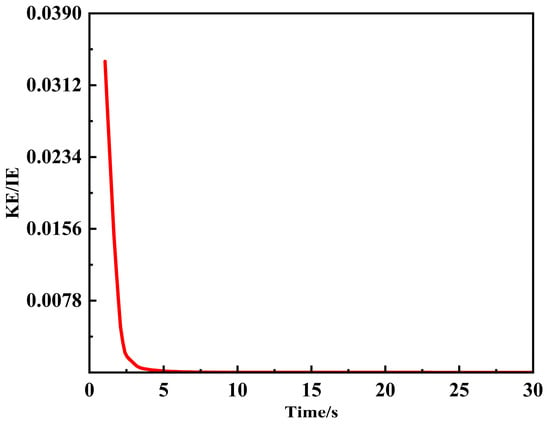

3.2. Simulation Reliability Verification

To verify the reliability of the finite element simulation, this study conducted corresponding die-less rotary drawing experiments. The experiment used a 29 × 13 mm elliptical prefabricated hole and was carried out at room temperature with a rotary drawing speed of 30 r/min and a feed rate of 60 mm/min. The test parameters were consistent with the simulation. The ratio of kinetic energy to internal energy of the model is less than 5%. As shown in Figure 11, the kinetic energy remains negligible compared to the internal energy, indicating that the model satisfies the quasi-static approximation. By comparing the experimental and simulation results, the accuracy of the finite element model was further verified.

Figure 11.

KE/IE ratio curve.

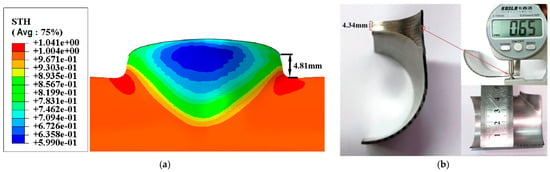

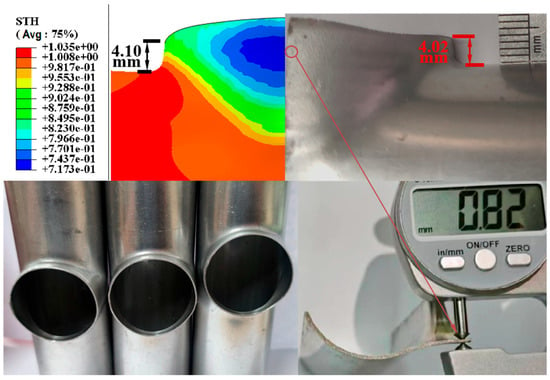

The simulation results of T-tube spin-drawing forming are shown in Figure 12a,b shows the experimental results (The “STH” is shell thickness). To facilitate wall thickness measurement, the T-tube was cut along the thinnest part of the wall thickness. The effective height measured in the T-tube test was 4.34 mm, and the minimum wall thickness was 0.65 mm. The effective height measured in the simulation results was 4.81 mm, and the minimum wall thickness was 0.599 mm. The results indicate that the relative error between the finite element simulation results and the experimental results is 11%; the errors are mainly due to machining errors caused by aging and wear of the driving equipment, mesh division accuracy errors, and measurement errors. Despite the above-mentioned errors, the two results are in good overall agreement, which confirms the reliability of the numerical simulation method.

Figure 12.

Simulation credibility validation. (a) simulation results; (b) experimental results.

4. Results and Analysis of Finite Element Simulation Orthogonal Experiment

The quality of branch tubes formed by die-less rotary drawing of T-shaped tubes is affected by multiple process parameters, mainly including: prefabricated hole size, rotary drawing speed, vertical feed rate, and tube blank pretreatment temperature. Therefore, this paper selects prefabricated hole size (A), tube blank pretreatment temperature (B), vertical feed rate (C), and rotary drawing speed (D) as test factors, with the maximum thinning rate (T) of T-shaped tubes and the effective height (H) of branch tubes as quality indicators. Three levels are selected for each test factor, and an orthogonal test with four factors and three levels is designed. The test factors and levels are shown in Table 3. In this paper, targeting a branch tube inner diameter of 38 mm and, in accordance with current industrial production requirements, the main tube has an inner diameter of 40 mm and a wall thickness of 1 mm, while the branch tube has an inner diameter of 38 mm with a minimum height requirement of 3 mm (including the transition filet). Therefore, we calculated according to Formula (5), by setting d as 39 mm and D as 41 mm, and considering that the end face requires shaping after rotary drawing (thus, the branch tube needs to leave a certain margin, so h is set as 4 mm), the size of the elliptical prefabricated hole is calculated to be 31 mm for the major axis and 15 mm for the minor axis. Hence, the three levels of factor A should be selected around this size. The levels of factors C and D are determined based on the total rotary drawing stroke calculated from the main tube diameter and the expected branch tube height, combined with the processing efficiency in actual experiments. The pretreatment temperature has a certain impact on the processing performance of 5A02 aluminum alloy. In the research by Jia Xiangdong et al. [18], it was found that when the deformation temperature is higher than 250 °C, the uniform elongation of 5A02 aluminum alloy exceeds 100%, while when exceeding 350 °C, the elongation tends to decrease. Meanwhile, studies have shown that aluminum alloys can significantly enhance plastic deformation and machinability in the cryogenic state, while generating a large number of substructures and high-density dislocations, leading to significant strengthening of the alloy [19]. Therefore, the three levels of factor B are selected as 250 °C, 25 °C, and −196 °C for pretreatment, and the treatments at different temperatures are carried out after completing the prefabricated hole processing step. The true stress–strain curves of 5A02 aluminum alloy under different temperature treatments are shown in Figure 13. Among them, the material plasticity decreases significantly after cryogenic pretreatment, which is not conducive to plastic forming. However, on the premise of ensuring the height of the T-shaped tube, different from processing in the cryogenic state, the material strength after cryogenic pretreatment is higher. Notably, the process adopted in this study is room temperature tensile testing after cryogenic pretreatment (the specimens were soaked in liquid nitrogen for 12 h, then removed and allowed to return to room temperature before mechanical property testing), which has an essential process difference from the cryogenic-state processing reported by Huang et al. [19]. This is the core reason for the distinct trends in material performance responses. Under the medium temperature condition of 250 °C, the material plasticity is significantly improved and the stress peak is the lowest, which is beneficial to the plastic processing of the material but has poor strength. The specific performance needs further experimental verification.

Table 3.

Factors and levels in orthogonal experiments.

Figure 13.

True stress–strain curves of 5A02 aluminum alloy under different thermal treatment conditions.

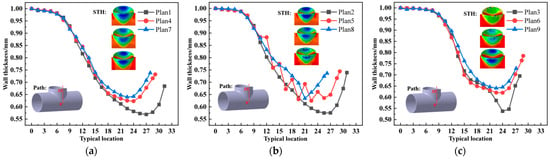

The orthogonal test scheme and results are shown in Table 4. The simulation results are divided into three groups: Groups 1, 4, and 7 are the medium temperature (250 °C) group; Groups 2, 5, and 8 are the normal temperature group (25 °C); Groups 3, 6, and 9 are the cryogenic group (−196 °C). The simulated wall thickness cloud diagram and the wall thickness distribution curve at typical positions of the T-shaped tube are shown in Figure 14. The simulation results show that the medium temperature group has the most uniform wall thickness distribution and the best surface quality of the T-shaped tube; although the normal temperature group has large fluctuations in wall thickness and obvious machining tool marks, there is no cracking; the end of Group 3 (cryogenic group) has obvious cracks, indicating that cryogenic treatment significantly affects material toughness, leading to stress concentration.

Table 4.

Results of simulated orthogonal experiments.

Figure 14.

Wall thickness distribution curve at the critical position under different temperature environments. (a) 250 °C temperature environment; (b) 25 °C temperature environment; (c) −196 °C temperature environment.

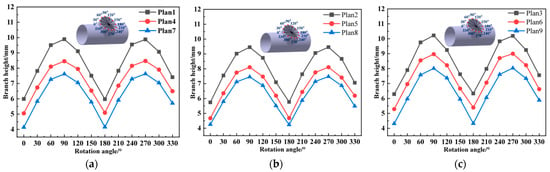

Figure 15 shows the height variation in T-shaped tubes under different temperature groups. The simulation results indicate that the wall thickness of the branch tube is the highest at the axial position of the tube blank and the lowest at the circumferential position. Through comparison, it is found that the effective height of the T-shaped tube largely depends on the size of the prefabricated hole, and its variation with temperature is relatively small. To further investigate the influencing factors of T-tube forming, this study performs range analysis and analysis of variance on the test results in Table 4 to clarify the degree of influence of various process parameters on the evaluation indicators and to identify the optimal combination of process parameters. The range analysis results are shown in Table 5, and the results of the analysis of variance are shown in Table 6.

Figure 15.

Height distribution curve of the T-shaped tube under different temperature environments. (a) 250 °C temperature environment; (b) 25 °C temperature environment; (c) −196 °C temperature environment.

Table 5.

Range analysis results.

Table 6.

Analysis of variance results.

As shown in Table 5, different factors have the same degree of influence on the wall thickness thinning rate T and the minimum height H; however, different levels of the same factor have a greater impact on the results. The two indicators are most affected by the size of the prefabricated hole, followed by the pretreatment temperature, then the rotary drawing speed, and finally the rotary drawing feed rate.

The experiment employed a saturated L9(34) orthogonal array, where all columns were occupied by factors, resulting in zero degrees of freedom for error, which precludes standard ANOVA. To evaluate the statistical significance of each factor, this study merges the sum of squares and degrees of freedom of the factor with the smallest sum of squares and uses them as an estimate of the error term to perform an approximate F-test. The ANOVA results for the thinning percentage (T%) indicate that none of the factors are statistically significant at the

= 0.05 level (all F-values are less than the critical value of 19.0). This may be due to an overestimation of the error term after pooling factor C. However, from a practical engineering perspective, both the range analysis and the contribution rate analysis suggest that Factor A (contribution rate 33.4%) and Factor B (contribution rate 27.7%) have substantial practical influence and should be prioritized in the optimization process. For the height (H), Factor A, with an F-value of 54.97, which far exceeds the critical value, demonstrates high statistical significance. Its contribution rate of 92.9% confirms it as the decisive parameter affecting the height.

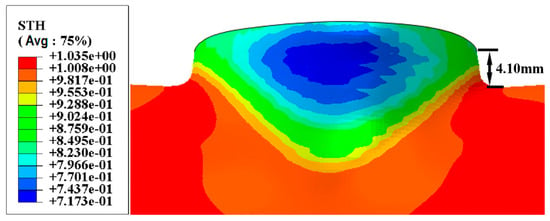

In engineering applications, the required height for branch tubes with a diameter of 38–50 mm is only 2.8–3.6 mm, while the minimum height in the above experiments is 4.14 mm, which fully meets the engineering application requirements. On the premise of meeting the branch tube height requirement, the wall thickness thinning rate should be reduced as much as possible. Therefore, by integrating the findings from range analysis, ANOVA, and practical engineering significance, the optimization scheme with the greatest impact on the thinning rate is selected as the optimal combination of process parameters, namely A3B2C2D1 prefabricated hole size of 31 × 15 mm, pretreatment temperature of 25 °C, feed rate of 30 mm/min, and rotary drawing speed of 10 r/min. Finite element simulation calculations were performed on the optimal parameter combination for rotary drawing of branch tubes from 5A02 aluminum alloy tubes with an inner diameter of Φ 40 mm and a wall thickness of 1 mm. The results of wall thickness and height are shown in Figure 16.

Figure 16.

Simulated wall thickness contour plots after parameter optimization.

The results show that under this parameter combination, the branch tube achieves a height of 4.10 mm with a wall thickness thinning rate of 28.3%, and no excessive thinning or cracking occurs, indicating that the optimal process parameter combination is accurate and reliable.

5. Experimental Validation and Microstructural Analysis

5.1. Experimental Validation

Experimental verification was conducted based on the optimal process parameter combination derived from the finite element simulation of 5A02 aluminum alloy tubes with an inner diameter of Φ 40 mm and a wall thickness of 1 mm. Figure 17 shows the T-shaped tube component obtained after the experiment. The measurement results indicate that the wall thickness thinning rate of the branch tube is 18%, and the minimum height is 4.02 mm. During the validation of the optimized scheme, the numerical model demonstrated reliable predictive capability. The error between the simulated and experimental values was only 2.0% for the branch height and 12.6% for the wall thickness, with discrepancies primarily attributable to factors such as mesh resolution and measurement inaccuracies. It is noteworthy that the relative error for the thinning rate reached 57.2%. This amplification stems from the calculation formula (Thinning Rate = (Initial Wall Thickness − Final Wall Thickness)/Initial Wall Thickness), where the fixed initial wall thickness magnifies the small absolute error in the final wall thickness. However, the true measure of the simulation’s validity lies in its predictive accuracy for key geometrical parameters—the errors for both the wall thickness and height of the branch are within acceptable limits (12.6% and 2%, respectively). Furthermore, the thinning region of the branch predicted by the simulation showed excellent agreement with the experimental results, providing further validation of the model’s reliability.

Figure 17.

T-tube test specimen after parameter optimization.

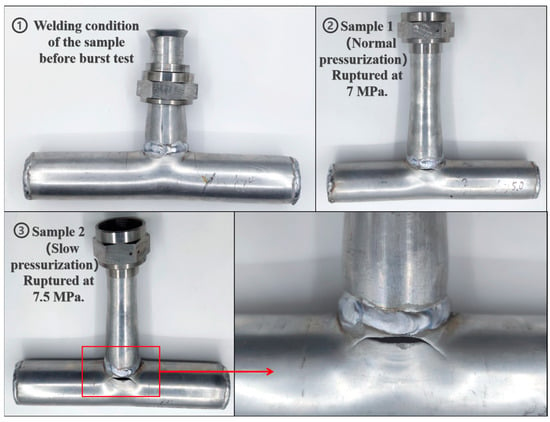

To verify the pressure resistance performance of the rotary drawn branch tube of this specification, a burst pressure test was conducted on a T-shaped tube test piece with a wall thickness of 1 mm and a main tube outer diameter of 42 mm. The burst test piece is shown in Figure 18. Both ends of the rotary drawn T-shaped tube were welded and sealed, and an extension pipe was welded at the branch pipe to facilitate connection with a high-pressure hydraulic pump. For Specimen 1, the normal pressurization scheme was adopted: YH-15 aviation hydraulic oil was used for pressurization at a rate of 5 MPa/min. For Specimen 2, the same pressurization medium was applied for slow pressurization at a rate of 2.5 MPa/min. The test results show that the pressure resistance limit of the rotary-drawn branch tube component of this specification is 7 MPa, which exceeds the engineering application requirement of 6.4 MPa for the minimum pressure resistance of 1.5 mm thick aviation tube materials [20].

Figure 18.

Burst Pressure Test.

5.2. Microstructural Analysis

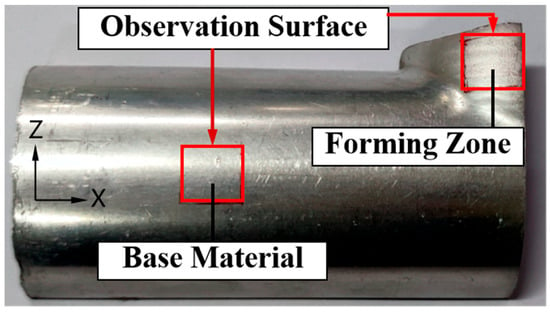

As shown in Figure 19, one sample was taken from each of the base material area of the tube blank and the formed area for Electron Backscatter Diffraction (EBSD) analysis to investigate the microstructural changes in the aluminum alloy in the processed area after rotary drawing forming.

Figure 19.

Sampling area and observation surface.

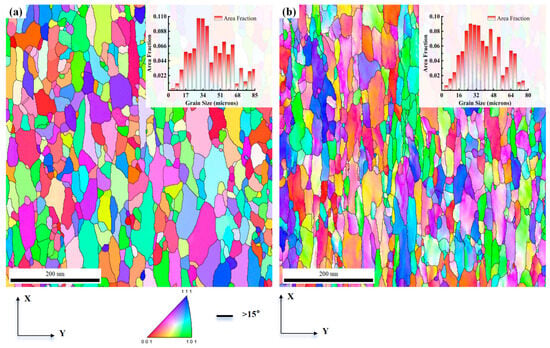

The grain morphologies of the undeformed and deformed regions of the tube blank are shown in Figure 20. Different colors represent the corresponding crystallographic orientations in the Inverse Pole Figure (IPF). It can be observed that the grains in the undeformed region are mainly equiaxed with distinct grain boundaries; the grain size is mainly distributed between 30 and 65 μm, with an average grain size of 43 μm. During the rotary drawing forming process, the grain morphology undergoes significant deformation; the grains become lath-like, with the grain size mainly distributed between 25 and 55 μm and an average grain size of 38 μm.

Figure 20.

Inverse pole figure. (a) Undeformed region. (b) Deformed region.

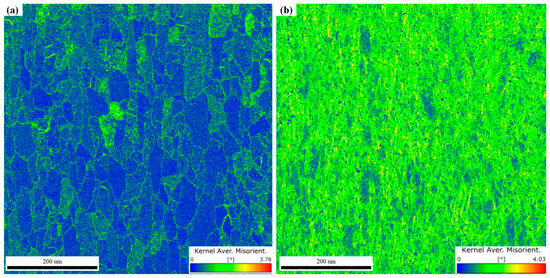

Figure 21 shows the Kernel Average Misorientation (KAM) maps of the undeformed and deformed regions of the tube blank. As shown in Figure 21a, the undeformed region exhibits low KAM values, indicating less dislocation accumulation. In contrast, Figure 21b reveals that the KAM values in the deformed region have undergone significant changes—they are uniformly distributed and have high values—indicating a large number of dislocations are generated in the deformed region after rotary drawing forming.

Figure 21.

Kernel average misorientation figure. (a) Undeformed region. (b) Deformed region.

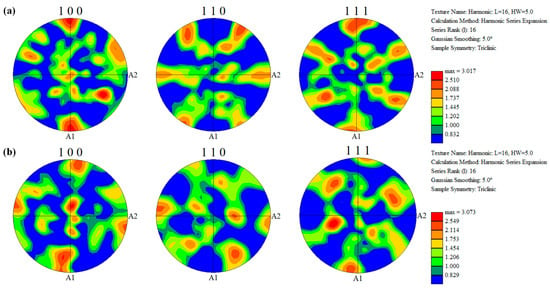

Figure 22 shows the pole figures of the undeformed and deformed regions of the tube blank. By comparison, it can be found that the texture intensity of the deformed region increases after rotary drawing forming. The texture type of the undeformed region of the tube blank is a typical cubic texture ({001}<100>), which is common in annealed aluminum alloys. However, the orientation of the deformed region has a certain deviation after rotary drawing forming, but it still belongs to the cubic texture overall, except that the texture intensity is slightly weaker (the peak orientation density decreases from 1.78 to 1.51), indicating a slight reduction in the degree of preferred orientation.

Figure 22.

Pole figure. (a) Undeformed Region. (b) Deformed region.

This plastic deformation-induced microstructural evolution aligns with the observation by Fu et al. [21]. In their study on thermomechanical processing of Al 6082 alloy—via high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (TEM)—that crystalline defects (e.g., dislocations and twins) introduced by plastic deformation provide fast channels for atomic diffusion and phase transformation, and dominate subsequent microstructural evolution. Drawing on this mechanism, it can be inferred that in the present study, high-density dislocations generated during the rotary drawing process not only directly cause work hardening but also offer nucleation sites for possible subsequent dynamic recovery, thus explaining the observed grain refinement and texture modification.

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- A mold-free rotary drawing forming method for T-shaped tubes is proposed, which enables the integrated manufacturing of further local branch tubes for already formed tube components.

- (2)

- A calculation formula for the size of the prefabricated hole for drawing/rotary drawing branch tubes is provided. Through the design of simulated orthogonal experiments, four process parameters—prefabricated hole size, tube blank pretreatment temperature, feed rate, and rotary drawing speed—were studied. The wall thickness thinning rate and minimum height at typical positions of the branch tube were analyzed, and the optimal process parameters were determined as follows: prefabricated hole size of 31 × 15 mm, pretreatment temperature of 25 °C, feed rate of 30 mm/min, and rotary drawing speed of 10 r/min.

- (3)

- Based on the optimal process parameter combination obtained from the simulated orthogonal experiments, the fabrication and measurement of test pieces were completed, verifying the reliability of the process parameters. Additionally, a pressure resistance test revealed that the pressure resistance limit of the rotary-drawn branch tube under this specification is 7 MPa, which can meet engineering application requirements.

Author Contributions

L.W.: writing, experiment, software. X.X.: conceptualization, methodology. J.X.: writing—review, validation. W.Z.: revision, validation. X.Z.: data processing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52575395).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be provided when required.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zeng, Y.S. Aircraft Sheet Metal Forming Technology; Aviation Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hyung-Rim, L.; Myoung-Gyu, L.; Namsu, P. Incremental tube forming process with a novel free rotating bearing tool tip: Experiment and FE modeling with anisotropic plasticity model. Met. Mater. Int. 2022, 28, 2356–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhou, J.P.; Liang, C.H.; Tan, J.P.; Lv, Z.P. Design of control system for automatic welding machine of T-shaped pipes. Mod. Manuf. Eng. 2007, 122–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.M.; Zhong, L.X.; Zhang, W.L.; Xue, X.F.; Li, Y.F.; Xie, J. Simulation and experimental research on internal high-pressure forming of T-shaped tube. J. Plast. Eng. 2024, 31, 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Sow, C.T.; Bazin, G.; Heuzé, T.; Racineux, G. Electromagnetic flanging: From elementary geometries to aeronautical components. Int. J. Mater. Form. 2020, 13, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.Y.; Yang, S.; Li, C.F.; Yu, H.P. Experimental study on electromagnetic pulse flanging of equal-diameter holes in aluminum alloy tube. Forg. Stamp. Technol. 2021, 46, 191–198. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, S.H.; Chen, M.; Song, H.W.; Deng, Q.W.; Huang, X.Y.; Wang, S.C. Research on flanging forming process of 6061 aluminum alloy T-shaped tube for aviation. Aeronaut. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 65, 61–67+88. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Q.S.; Wang, C.; LI, H.G.; He, X.T.; Ding, Y.X.; Zhao, Y. Simulation research on internal high-pressure forming of 5083 aluminum alloy T-junction. Forg. Stamp. Technol. 2012, 37, 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.S.; Yin, Y.G.; Zhao, T.Z. Electromagnetic forming of flanging on 5A02 aluminum alloy T-junction tube for aviation. J. Plast. Eng. 2021, 28, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Dong, C.; Liu, Z.; Yi, Y.; Zhou, Y. The Influence of Rolling Reduction on the Mechanical, Corrosion, Osteogenic, and Antibacterial Properties of Zn-Mg Alloys. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 37141–37153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edward, L. Apparatus and Process for Incremental Dieless Forming. U.S. Patent US3342051A, 19 September 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Wen, T.; Liu, L.T.; Zhang, S.; Wang, H. Dieless incremental hole-flanging of thin-walled tube for producing branched tubing. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2014, 214, 2461–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.F.; Wen, T.; Hong, Y.F.; Huo, X.C.; Du, K.K. Profiled tube wall progressive hole-flanging and its deformation characteristics analysis. Forg. Stamp. Technol. 2021, 46, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyyed, E.S.; Gorji, H.; Bakhshi-Jooybari, M.; Mirnia, M.J. Comparison between conventional press-working and incremental forming in hole-flanging of AA6061-T6 sheets using a ductile fracture model. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2023, 270, 112225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besong, L.I.; Buhl, J.; Bambach, M. Investigations on hole-flanging by paddle forming and a comparison with single point incremental forming. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2019, 164, 105143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, M.H.; Li, Y.F.; Shao, M.Y.; Wang, Y.T.; Zhang, M.Y.; Zhao, K.; Li, S.L.; Xiao, H.X.; Zhao, S.N.; Liu, C.C. Formation causes of microcracks in hole-extruding of aluminum shell. Phys. Test. Chem. Anal. (Part A Phys. Test.) 2023, 59, 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.T. Flanging forming circular hole from prefabricated elliptical hole on stainless steel bent pipe. J. Rocket Propuls. 2009, 35, 50–53. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, X.D.; Yuan, R.J.; He, L.Y.; Cao, M.Y.; Wang, R.; Zhao, C.C. Plastic forming performance of 5A02 aluminum alloy under high-temperature deformation conditions. Rare Met. Mater. Eng. 2020, 49, 2189–2197. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.W.; Yi, Y.P.; Huang, S.P.; Guo, W.F. Effect of cryogenic deformation on grain structure and properties of 2219 aluminum alloy ring workpiece. Mater. Rep. 2020, 34, 14129–14133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Yang, P.C.; Yang, J.C.; Li, G.J.; Men, X.N.; Duan, X.Y.; Ren, L.S.; Fang, S.P.; Pu, R.S.; Cao, Y. Research and verification of process parameters for cold push-bending forming of thin-walled aluminum tubes with large diameter-thickness ratio. J. Plast. Eng. 2025, 32, 28–37. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y.; Mehr, V.Y.; Toroghinejad, M.R.; Chen, X.; Jie, J.; Zhu, S. Twinning and stacking fault-induced precipitation in an aluminum alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 34, 2127–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).