Effect of Different Acid Treatments on the Properties of NiCoOx for CO-Catalyzed Oxidation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Method

2.1. Catalyst Preparation and Acidic Modification Treatment

2.2. Catalyst Activity Test

2.3. Characterization of Catalysts

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. XRD Characterization Results for Catalysts

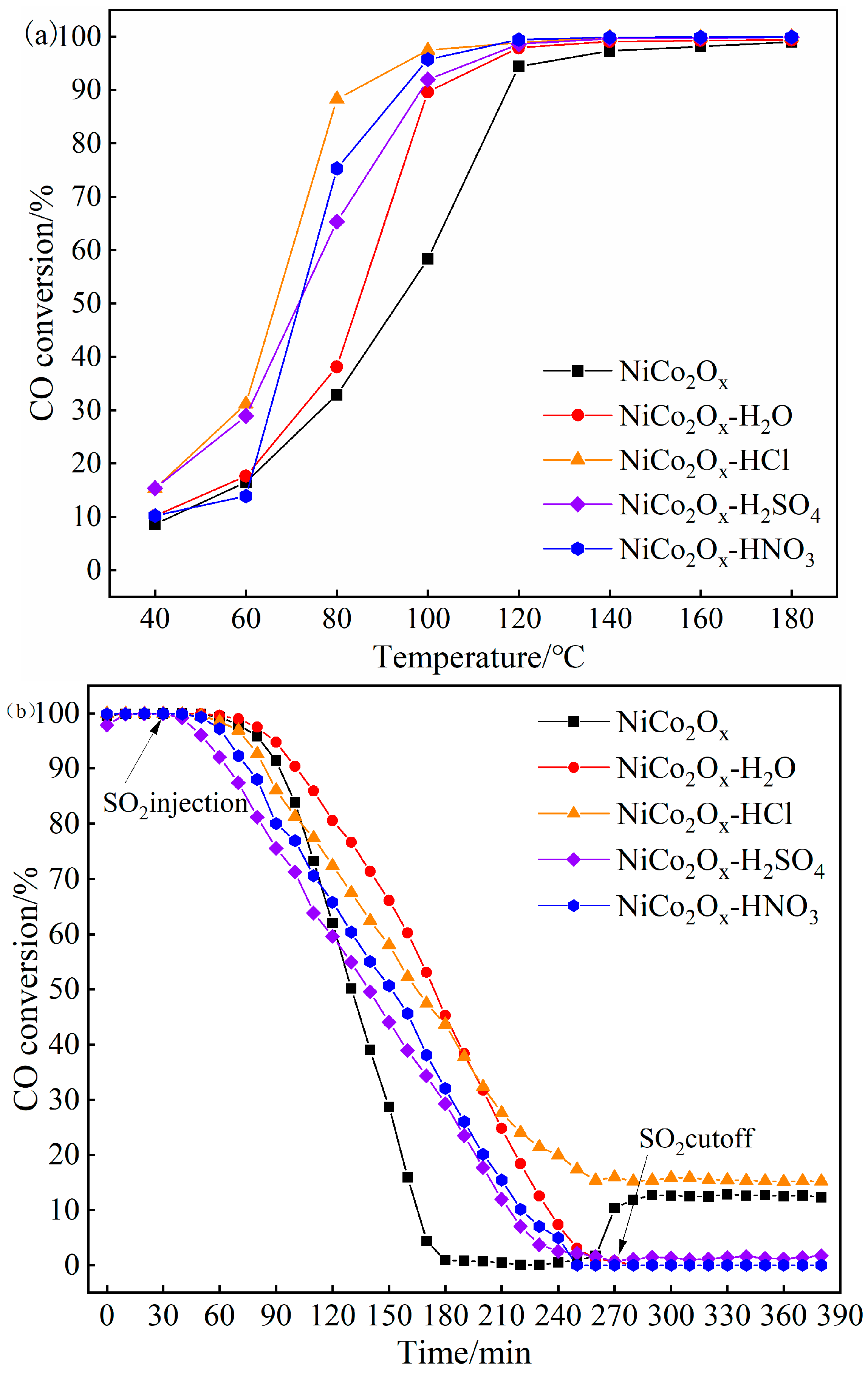

3.2. Catalytic Performance and Sulfur Tolerance of Modified NiCo2O4

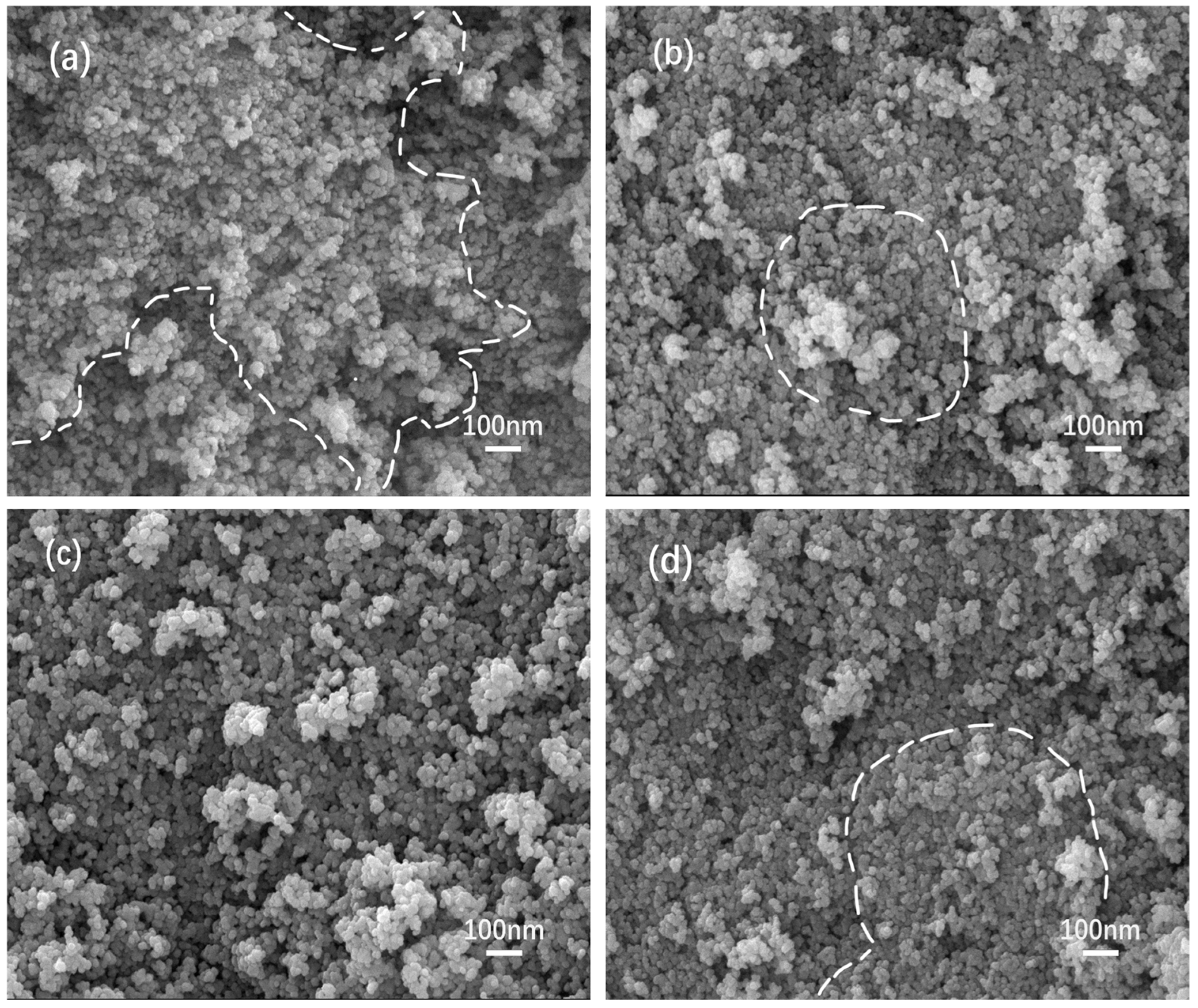

3.3. SEM Analysis

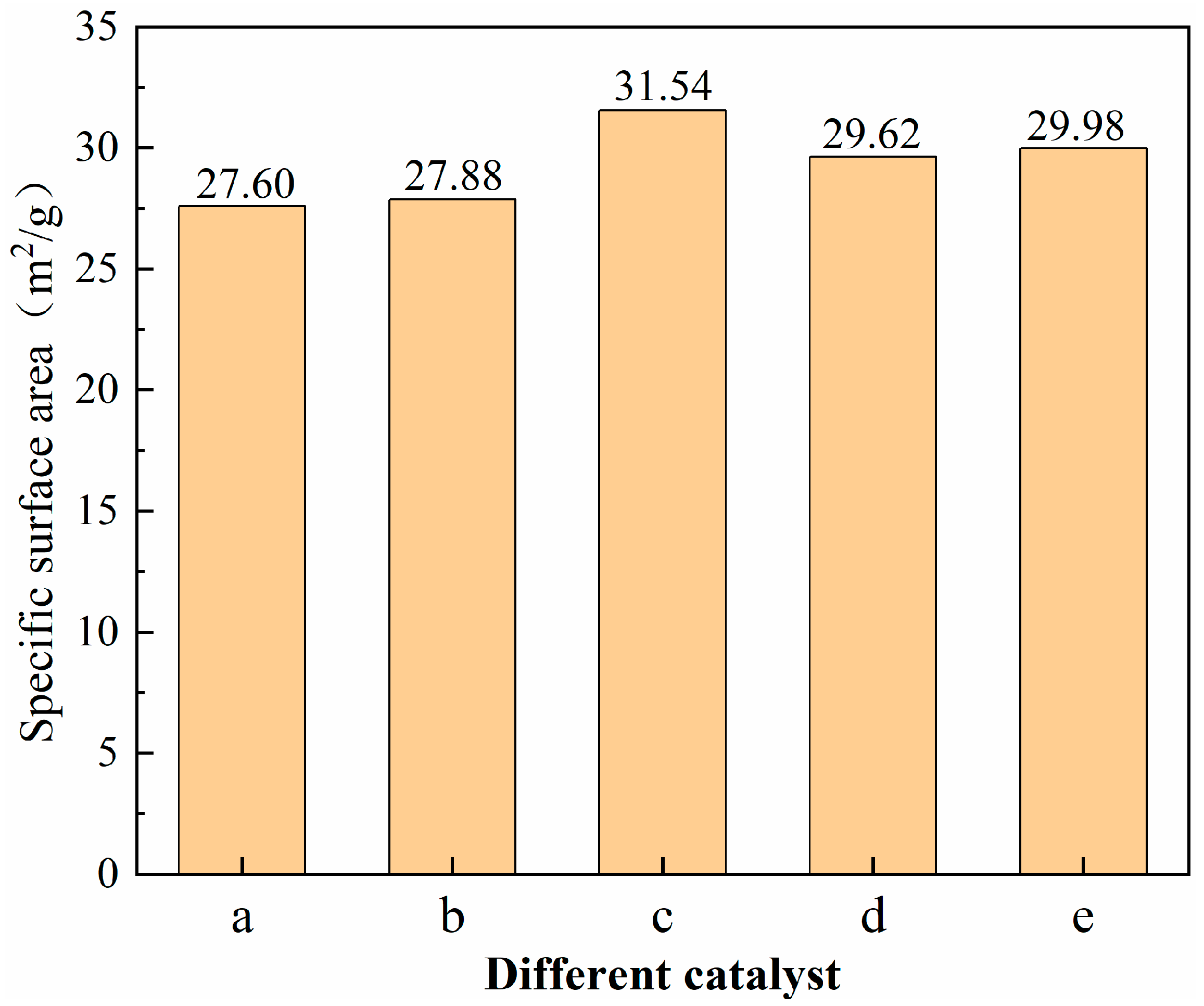

3.4. BET Characterization of Catalysts

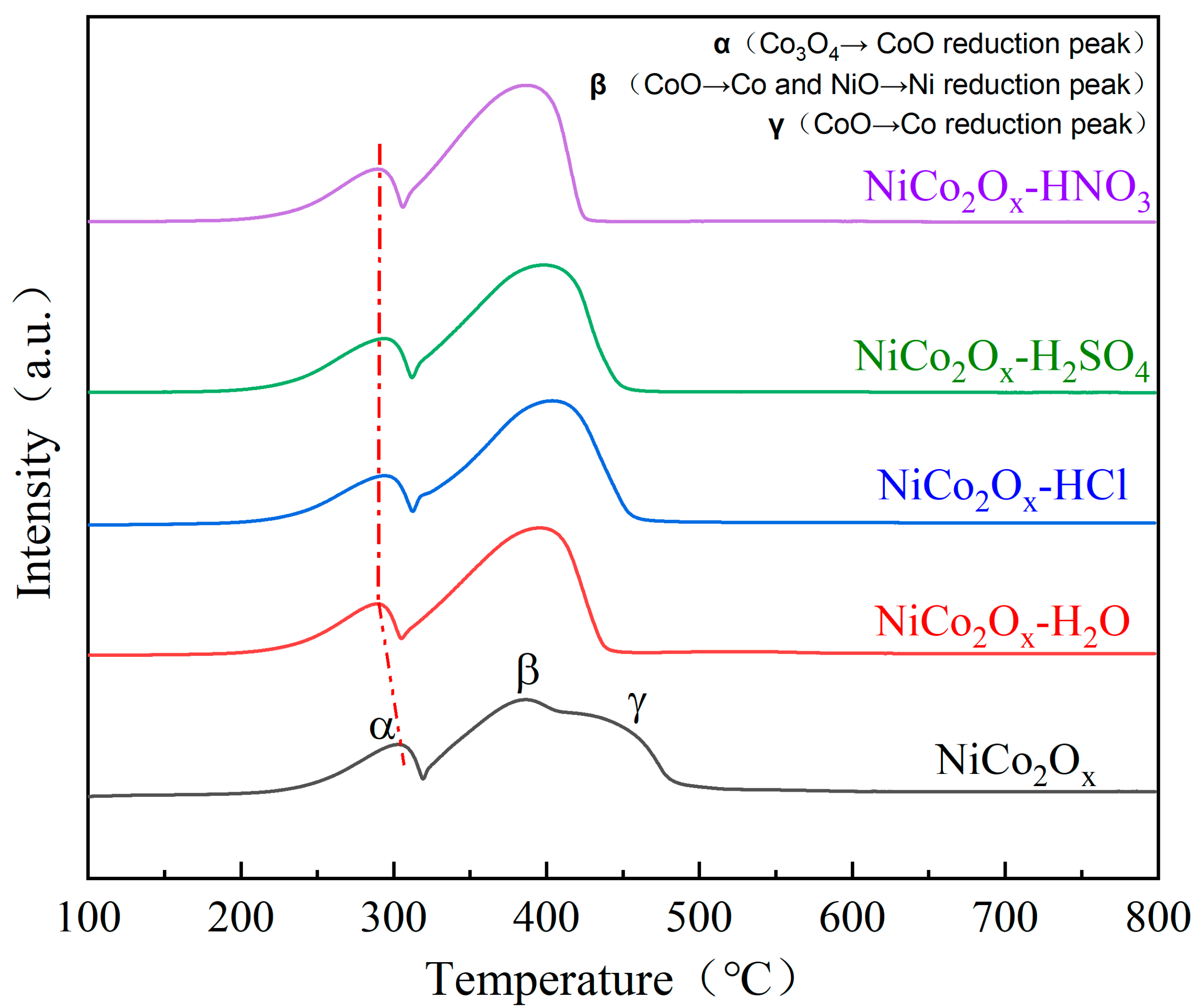

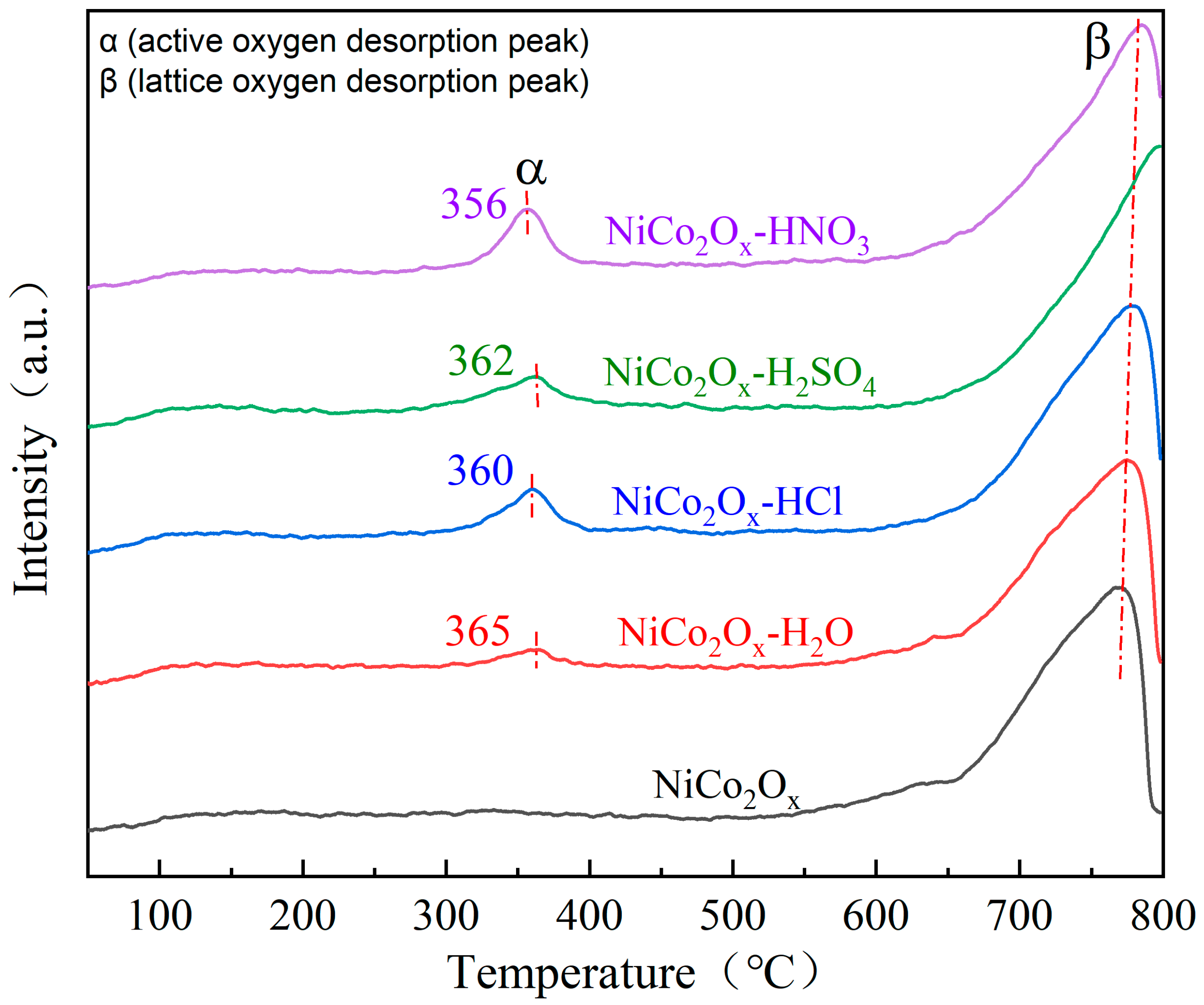

3.5. Characterization of Catalyst H2 Temperature Programmed Reduction (H2-TPR)

3.6. Characterization of Catalyst with CO Temperature-Programmed Desorption (CO-TPD)

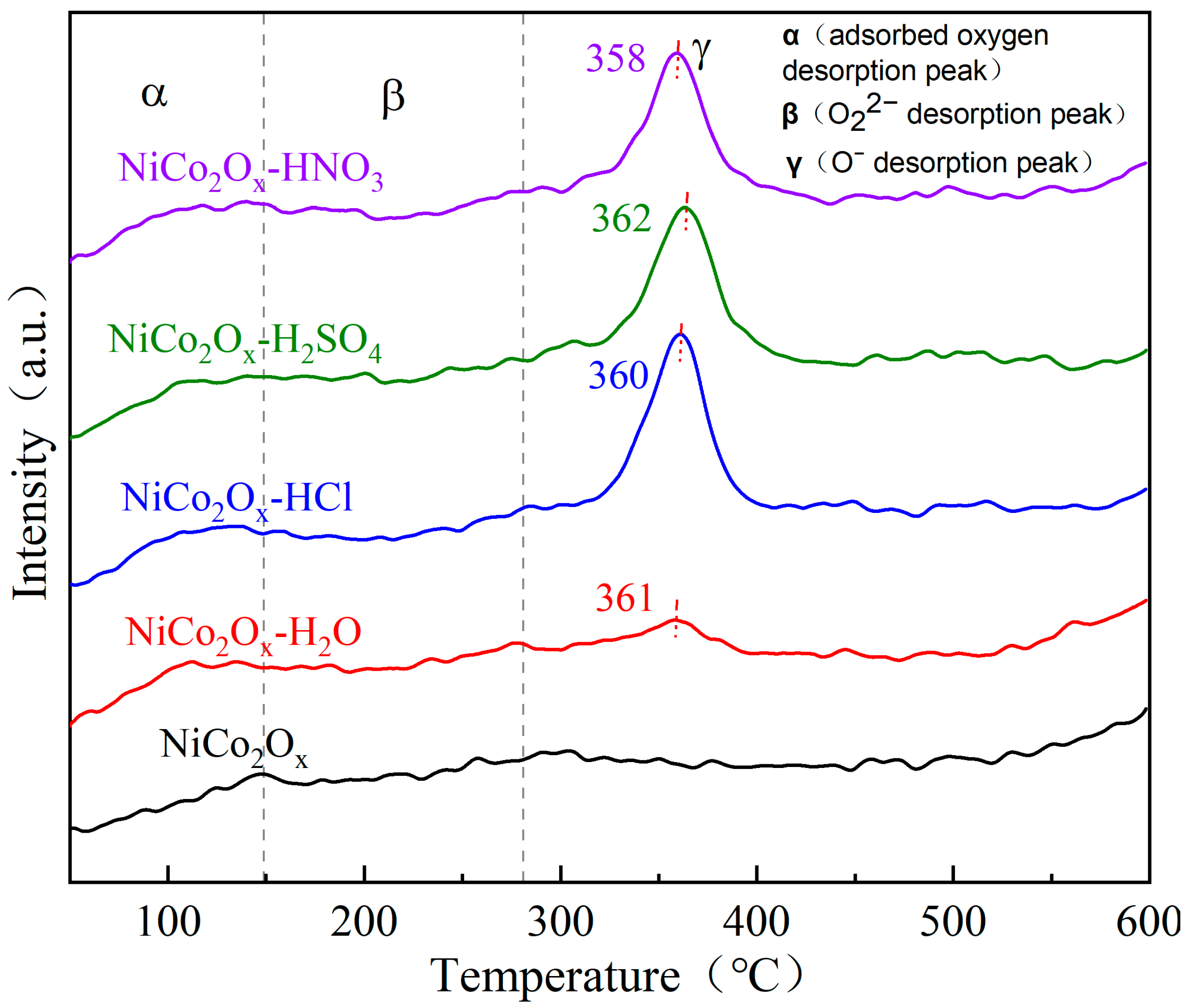

3.7. Characterization of Oxygen Temperature-Programmed Desorption (O2-TPD)

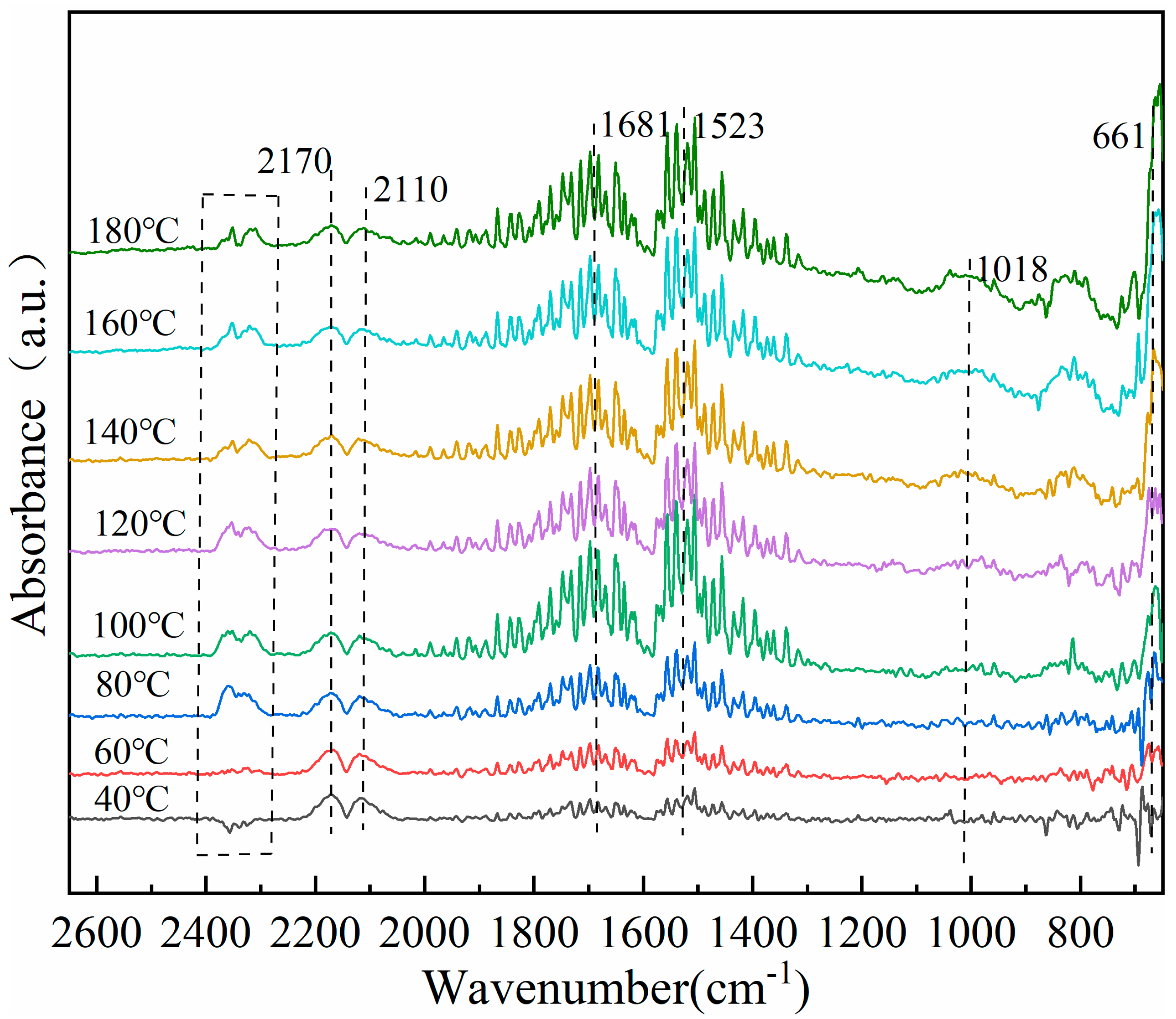

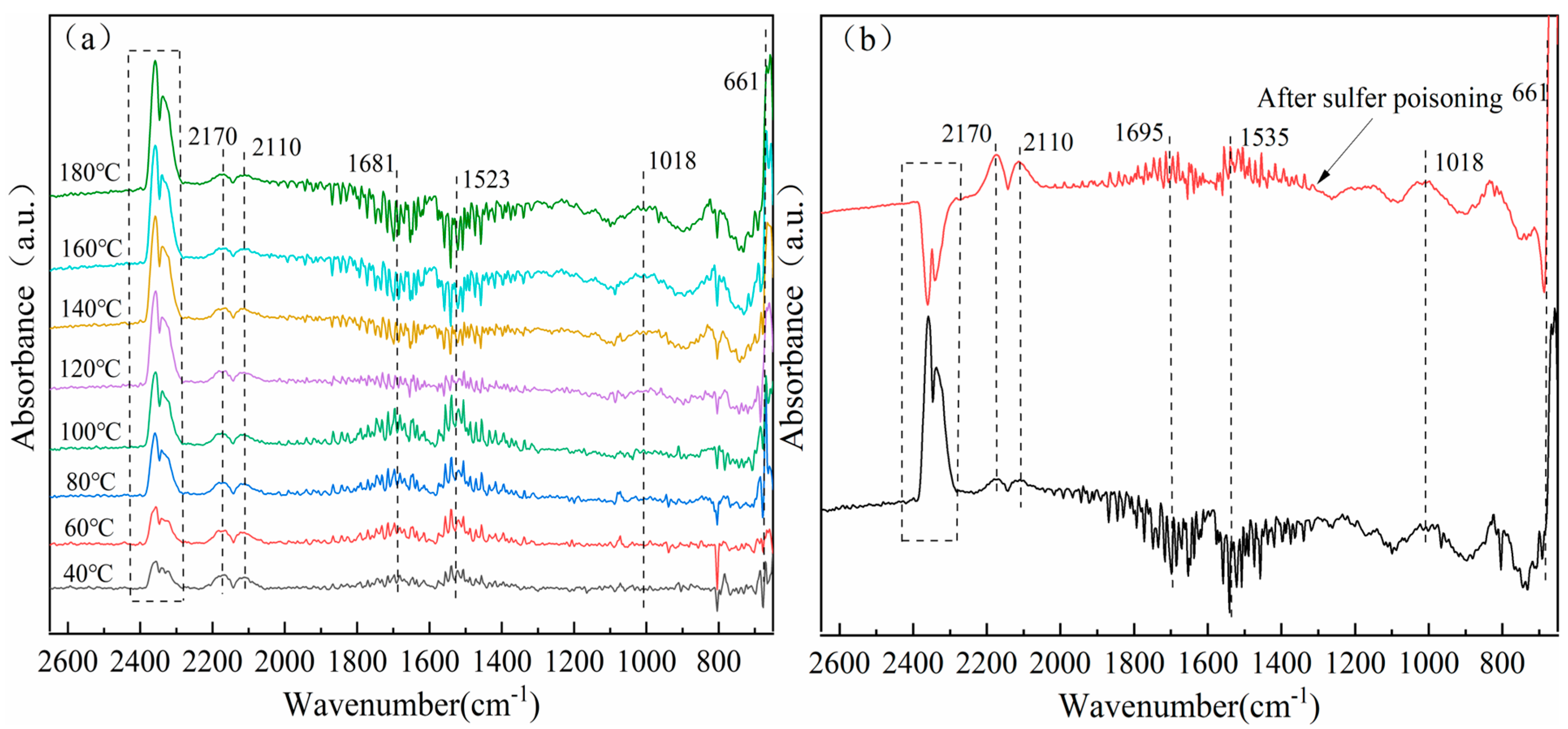

3.8. In Situ Infrared Diffuse Reflection Characterization of Catalysts

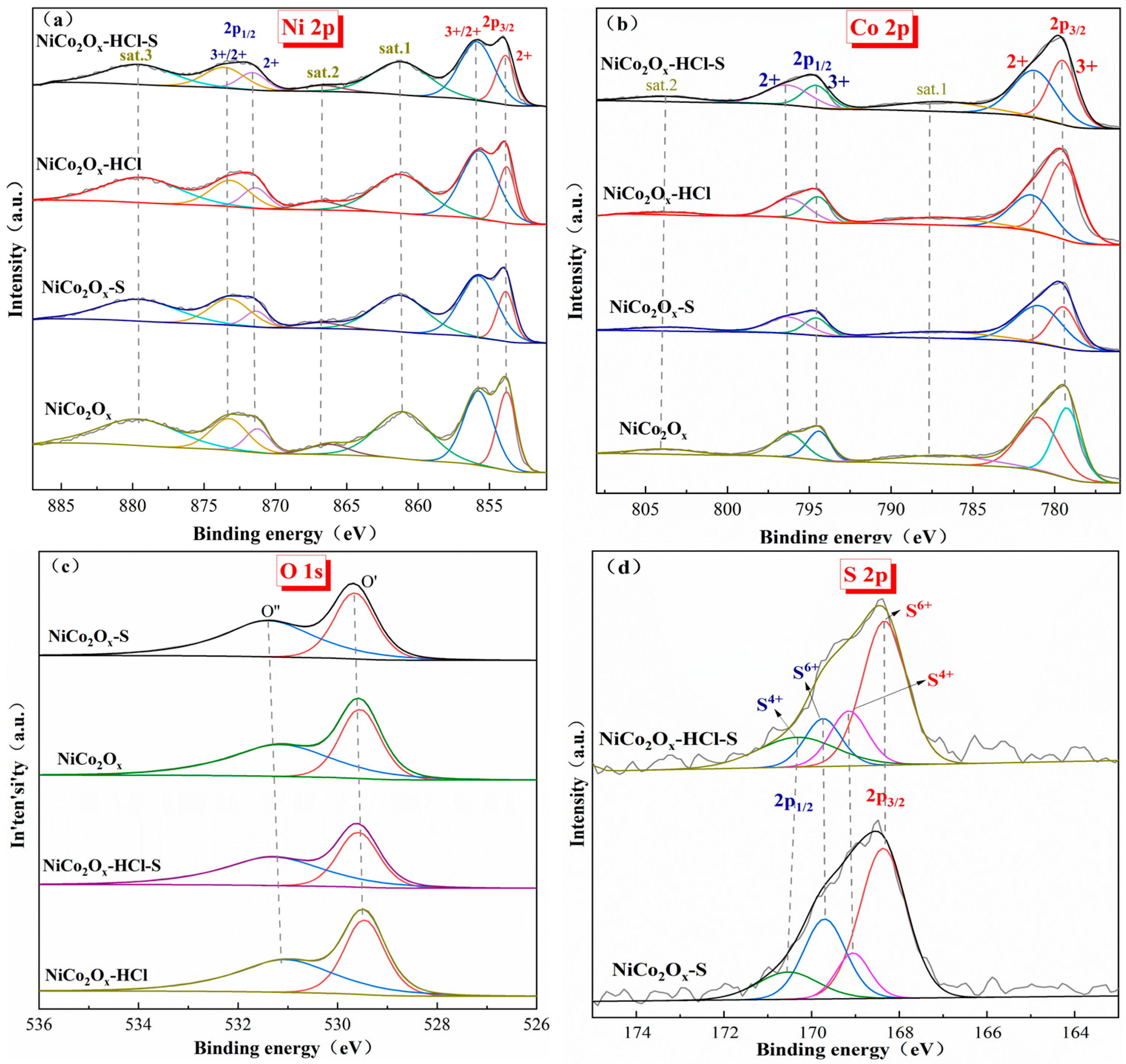

3.9. XPS Characterization Results for Catalysts

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mahajan, S.; Jagtap, S. Metal-oxide semiconductors for carbon monoxide (CO) gas sensing: A review. Appl. Mater. Today 2020, 18, 100483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngorot Kembo, J.P.; Wang, J.; Luo, N.; Gao, F.; Yi, H.; Zhao, S.; Zhou, Y.; Tang, X. A review of catalytic oxidation of carbon monoxide over different catalysts with an emphasis on hopcalite catalysts. New J. Chem. 2023, 47, 20222–20247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Zhang, W.-B.; Su, W.; Wen, W.; Zhao, X.-J.; Yu, J.-X. Research of ultra-low emission technologies of the iron and steel industry in China. Chin. J. Eng. 2021, 43, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Royer, S.; Duprez, D. Catalytic oxidation of carbon monoxide over transition metal oxides. ChemCatChem 2011, 3, 24–65. [Google Scholar]

- Yadava, R.N.; Bhatt, V. Carbon monoxide: Risk assessment, environmental, and health hazard. In Hazardous Gases; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, C.; Liu, X.; Zhu, T.; Tian, M. Catalytic oxidation of CO on noble metal-based catalysts. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 24847–24871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, V.P.; Carabineiro, S.A.C.; Tavares, P.B.; Pereira, M.F.R.; Órfão, J.J.M.; Figueiredo, J.L. Oxidation of CO, ethanol and toluene over TiO2 supported noble metal catalysts. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2010, 99, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Dai, H.; Deng, J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, H.; Jiang, Y.; Tan, W.; Ao, A.; Guo, G. Au/3DOM Co3O4: Highly active nanocatalysts for the oxidation of carbon monoxide and toluene. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 11207–11219. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.-G.; Yang, X.-F.; Li, J. Theoretical studies of CO oxidation with lattice oxygen on Co3O4 surfaces. Chin. J. Catal. 2016, 37, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Jia, C.-J.; Weidenthaler, C.; Bongard, H.-J.; Spliethoff, B.; Schmidt, W.; Schüth, F. Highly ordered mesoporous cobalt-containing oxides: Structure, catalytic properties, and active sites in oxidation of carbon monoxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 11407–11418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.W.; Kim, D.H.; Jeong, M.-G.; Park, K.J.; Kim, Y.D. CO oxidation catalyzed by NiO supported on mesoporous Al2O3 at room temperature. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 283, 992–998. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, S.; Mehta, N.S. Oxidation of carbon monoxide over various nickel oxide catalysts in different conditions: A review. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2020, 1, 100008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Fu, K.; Pang, C.; Zheng, Y.; Song, C.; Ji, N.; Ma, D.; Lu, X.; Liu, C.; Han, R. Recent advances of chlorinated volatile organic compounds’ oxidation catalyzed by multiple catalysts: Reasonable adjustment of acidity and redox properties. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 9854–9871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, H.; Zhao, W.; Wu, R.; Yue, L.; Wang, Y.; Ren, Z.; Zhao, Y. Effect of acid treatment on the catalytic performance of CuO/Cryptomelane catalyst for CO preferential oxidation in H2-rich streams. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 27619–27630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Li, J.; Wang, D.; Peng, Y.; Ma, Y. Activity improvement of acid treatment on LaFeO3 catalyst for CO oxidation. Catal. Today 2021, 376, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Song, H.; Cui, Y.; Xue, Y.; Wu, C.-E.; Pan, C.; Xu, J.; Qiu, J.; Xu, L.; et al. Transition Metal (Fe2O3, Co3O4 and NiO)-Promoted CuO-Based α-MnO2 Nanowire Catalysts for Low-Temperature CO Oxidation. Catalysts 2023, 13, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, Z.; Cao, T.; Yang, J.; Kuang, Y.; Kang, J. The Effect of Adding Different Elements (Mg, Fe, Cu, and Ce) on the Properties of NiCo2OX for CO-Catalyzed Oxidation. Materials 2025, 18, 2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenhofer, M.F.; Shi, H.; Gutiérrez, O.Y.; Jentys, A.; Lercher, J.A. Enhancing hydrogenation activity of Ni-Mo sulfide hydrodesulfurization catalysts. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaax5331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, M.T.; Nguyen, P.A.; Tran, T.T.H.; Chu, T.H.N.; Wang, Y.; Arandiyan, H. Catalytic performance of spinel-type Ni-Co Oxides for Oxidation of Carbon Monoxide and Toluene. Top. Catal. 2023, 66, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, M.T.; Nguyen, T.T.; Pham, P.T.M.; Bruneel, E.; Van Driessche, I. Activated MnO2-Co3O4-CeO2 catalysts for the treatment of CO at room temperature. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2014, 480, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, J.; Kang, J.; Liu, W.; Kuang, Y.; Tan, H.; Yu, Z.; Yang, L.; Yang, X.; Yu, K. Preparation of Ce-MnOx composite oxides via coprecipitation and their catalytic performance for CO oxidation. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, M.; Groot, I.M.N.; Shaikhutdinov, S.; Freund, H.J. Scanning tunneling microscopy evidence for the Mars-van Krevelen type mechanism of low temperature CO oxidation on an FeO(111) film on Pt(111). Catal. Today 2012, 181, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, M.I.; Hasan, M.A.; Pasupulety, L. Influence of CuOx additives on CO oxidation activity and related surface and bulk behaviours of Mn2O3, Cr2O3 and WO3 catalysts. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2000, 198, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Gu, B.; Tang, Q.; Cao, Q.; Wei, K.; Fang, W. Synergy in magnetic NixCo1Oy oxides enables base-free selective oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural on loaded Au nanoparticles. J. Energy Chem. 2023, 78, 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Zhang, P.; Qin, Z.; Yu, C.; Li, W.; Qin, Q.; Li, B.; Fan, M.; Liang, X.; Dong, L. Low temperature CO oxidation catalysed by flower-like Ni–Co–O: How physicochemical properties influence catalytic performance. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 7110–7122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, J. Interpretation of Infrared Spectra, A Practical Approach. In Encyclopedia of Analytical Chemistry; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios, E.G.; Juárez-López, G.; Monhemius, A.J. Infrared spectroscopy of metal carboxylates: II. Analysis of Fe(III), Ni and Zn carboxylate solutions. Hydrometallurgy 2004, 72, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.R.; Oliver, B.G. A vibrational-spectroscopic study of the species present in the CO2−H2O system. J. Solut. Chem. 1972, 1, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, A.; Yu, Y.; Ji, J.; Guo, K.; Wan, H.; Tang, C.; Dong, L. Unravelling the structure sensitivity of CuO/SiO2 catalysts in the NO+ CO reaction. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2020, 10, 3848–3856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, D. Interfacial effects promote the catalytic performance of CuCoO2-CeO2 metal oxides for the selective reduction of NO by CO. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 465, 142856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-Z.; Zhao, Y.-X.; Gao, C.-G.; Liu, D.-S. Preparation and catalytic performance of Co3O4 catalysts for low-temperature CO oxidation. Catal. Lett. 2007, 116, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbitt, H.W.; Legrand, D.; Bancroft, G.M. Interpretation of Ni2p XPS spectra of Ni conductors and Ni insulators. Phys. Chem. Miner. 2000, 27, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesinger, M.C.; Payne, B.P.; Lau, L.W.M.; Gerson, A.; Smart, R.S.C. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopic chemical state quantification of mixed nickel metal, oxide and hydroxide systems. Surf. Interface Anal. 2009, 41, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, S.; Wang, S. Nanoneedle-forest NiCo2O4@nitrogen-doped Carbon-Mo2C/CC as Double Functional Electrocatalysts for Water Hydrolysis and Zn-air Batteries. Res. Sq. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.G.; Pugmire, D.L.; Battaglia, D.; Langell, M.A. Analysis of the NiCo2O4 spinel surface with Auger and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2000, 165, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, R. CeO2 nanorods supported M–Co bimetallic oxides (M = Fe, Ni, Cu) for catalytic CO and C3H8 oxidation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 560, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Cai, L.; Bajdich, M.; García-Melchor, M.; Li, H.; He, J.; Wilcox, J.; Wu, W.; Vojvodic, A.; Zheng, X. Enhancing catalytic CO oxidation over Co3O4 nanowires by substituting Co2+ with Cu2+. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 4485–4491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solsona, B.; Concepción, P.; Hernández, S.; Demicol, B.; Nieto, J.M.L. Oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane over NiO–CeO2 mixed oxides catalysts. Catal. Today 2012, 180, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teymoori, S.M.; Alavi, S.M.; Rezaei, M. Catalytic oxidation of CO over the MOx—Co3O4 (M:Fe, Mn, Cu, Ni, Cr, and Zn) mixed oxide nanocatalysts at low temperatures. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Yang, H.; Qiu, F.; Zhang, X. Promotional effects of carbon nanotubes on V2O5/TiO2 for NOX removal. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 192, 915–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Xiu, J.; Williams, C.T.; Liang, C. Synthesis and characterization of ferromagnetic nickel–cobalt silicide catalysts with good sulfur tolerance in hydrodesulfurization of dibenzothiophene. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 24968–24976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, K.J.; Raj Kumar, T.; Yoo, D.J.; Phang, S.-M.; Gnana Kumar, G. Electrodeposited nickel cobalt sulfide flowerlike architectures on disposable cellulose filter paper for enzyme-free glucose sensor applications. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 16982–16989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Ding, Y.; Luo, J.; Yu, Z. Nickel cobalt thiospinel nanoparticles as hydrodesulfurization catalysts: Importance of cation position, structural stability, and sulfur vacancy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 19673–19681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Raw Materials | Chemical Formula | Specification | Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen | N2 | 99.99% | Fanggang Changsha, China |

| Carbon Monoxide | CO + N2 | 1.98% | Fanggang Changsha, China |

| Oxygen | O2 | 99.99% | Fanggang Changsha, China |

| Sulfur Dioxide | SO2 + N2 | 2.03% | Fanggang Changsha, China |

| H2 Standard Gas | H2 + Ar | 10% | Gaoke Changsha, China |

| CO Standard Gas | CO + He | 9.99% | Chuangwei Shanghai, China |

| O2 Standard Gas | O2 + He | 5.01% | Chuangwei Shanghai, China |

| Catalysts | Attribution and Temperature of Reduction Peak | H2 Consumption (mmol/g) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α | β | γ | ||

| Co3O4→CoO | CoO→Co | CoO→Co | ||

| NiO→Ni | ||||

| NiCo2O4 | 303 | 386 | 450 | 11.53 |

| NiCo2O4-HCl | 293 | 403 | / | 12.92 |

| NiCo2O4-H2SO4 | 294 | 400 | / | 12.86 |

| NiCo2O4-HNO3 | 288 | 389 | / | 12.78 |

| Samples | Atomic Concentration (at%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni | Co | O | S | Cl | |

| NiCo2Ox | 12.44 | 22.70 | 64.86 | 0 | 0 |

| NiCo2Ox-S | 11.94 | 20.10 | 64.27 | 3.69 | 0 |

| NiCo2Ox-HCl | 11.12 | 23.22 | 65.38 | 0 | 0.27 |

| NiCo2Ox-HCl-S | 8.55 | 22.93 | 64.90 | 3.32 | 0.30 |

| Samples | Atomic Concentration (at%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S6+/(S6+ + S4+) | Ni2+/Nix+ | Co3+/Cox+ | O″/(O″ + O′) | |

| NiCo2Ox | 0 | 59.19 | 43.15 | 53.66 |

| NiCo2Ox-S | 80.79 | 57.30 | 30.66 | 58.94 |

| NiCo2Ox-HCl | 0 | 59.05 | 50.96 | 55.91 |

| NiCo2Ox-HCl-S | 67.42 | 59.70 | 36.33 | 57.84 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Chen, Z.; Cao, T.; Yang, J.; Tan, H. Effect of Different Acid Treatments on the Properties of NiCoOx for CO-Catalyzed Oxidation. Coatings 2025, 15, 1463. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121463

Li X, Chen Z, Cao T, Yang J, Tan H. Effect of Different Acid Treatments on the Properties of NiCoOx for CO-Catalyzed Oxidation. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1463. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121463

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xianghu, Zhili Chen, Tianqi Cao, Junsheng Yang, and Hua Tan. 2025. "Effect of Different Acid Treatments on the Properties of NiCoOx for CO-Catalyzed Oxidation" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1463. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121463

APA StyleLi, X., Chen, Z., Cao, T., Yang, J., & Tan, H. (2025). Effect of Different Acid Treatments on the Properties of NiCoOx for CO-Catalyzed Oxidation. Coatings, 15(12), 1463. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121463