Abstract

Slow- or controlled-release fertilizers have been used widely to enhance fertilizer nutrient release efficiency and decrease nutrient pollution. To further evaluate the effectiveness of controlled-release fertilizers in water or soil, conventional NPK (16N-4P-8K) fertilizers were encapsulated with beeswax, and their effects on water, soil, and morphological features (root-to-shoot ratio, shoot and root weight) of maize plants were analyzed and compared with uncoated fertilizer. The results indicated that beeswax-coated fertilizer reduced the NPK dissolution rate from 30% to 50% in water within 24 h. In soil conditions, the beeswax coating resulted in a slightly but insignificantly slower release of NPK over 4–6 days. No significant differences were observed between uncoated and beeswax-coated fertilizers in maize morphological features, likely due to the limited persistence of the beeswax-coating film in water and soil. Findings from this study suggest that beeswax coating exhibits strong hydrophobic properties in reducing NPK leaching in water, with the potential for further optimization.

1. Introduction

Nitrogen (N), potassium (K), and phosphorus (P) are essential elements supplied by fertilizers to support crop growth and development. However, these macronutrients are prone to loss through crop production, erosion, and leaching. Plants primarily absorb nitrogen as inorganic compounds, specifically nitrate and ammonium. Due to the cation exchange capacity, positively charged ammonium is retained in the soil, while negatively charged nitrate remains dissolved in water and tends to move downward through the soil [1]. Potassium is soluble in water and can bind to clay particles, disperse with organic materials from agricultural wastes in runoff water, or leach into deeper soil layers [2]. The anionic forms of phosphorus are immobile in soil, typically remaining on the soil surface and being carried away by runoff water with soil particles [3]. Phosphorus is necessary for energy production and root formation in young plants, but more than 80% of P in soils is unavailable for plant uptake [4,5]. Therefore, NPK fertilizers have been widely used in agriculture to replenish nutrient losses caused by water runoff and soil erosion, promoting soil fertility and supporting agricultural sustainability. However, untreated water-soluble fertilizers have the potential to be carried away by the movement of the soil and water, resulting in ineffective nutrient contribution. The USDA announced that as much as 40% to 80% of the manufactured fertilizer is lost to the environment each year, resulting in ecosystem eutrophication [6]. The increased levels of nitrate ions (NO3−) and phosphate ions (PO43–) in water stimulate microbial growth, which reduces dissolved oxygen and adversely affects desirable aquatic species when the microbes die [7]. Ammonium (NH4+) in soil can be biologically oxidized to nitrate (NO3−) and a greenhouse gas (N2O), resulting in eutrophication and global warming [8]. The current challenge is to enhance fertilizer efficiency, allowing for a prolonged effect throughout the growing season without increasing the quantity of fertilizer while achieving the same crop and plant yields.

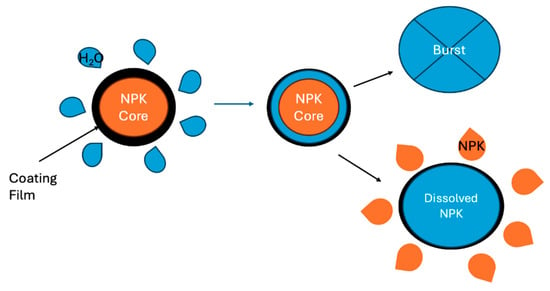

As one of the slow-released fertilizers (SRFs) or controlled-release fertilizers (CRFs), coated fertilizers delay or control the dissolution rate of commercial fertilizers in soil by coating fertilizer pellets with insoluble impervious shells [9]. Coated or encapsulated fertilizers typically exhibit three stages of release patterns (Figure 1) [10,11,12]. In the first stage, water from the soil wets the coating, allowing it to enter through the porous membrane and penetrate the granule core. This process results in vapor condensation on the fertilizer core, which dissolves a small portion of the granule. Two potential outcomes arise as the granule swells due to the buildup of internal pressure [10]. The first outcome occurs when the internal pressure exceeds the resistance of the coating film, leading to a spontaneous rupture of the granule and the release of its nutritional content—this is identified as a failure mechanism. The second outcome involves the coating film successfully resisting the internal pressure, gradually diffusing the granule content through the coating cracks. The pressure gradient drives this diffusion and represents a slower or a faster controlled-release mechanism.

Figure 1.

The diffusion mechanism of coated fertilizers (created by the authors).

Coating materials can be classified into two main types: hydrophobic organic polymer materials, such as thermoplastics and resins, and inorganic materials, including sulfur and minerals [10]. With its long hydrocarbon chains, wax acts as a barrier that prevents moisture infiltration, making it a promising coating material [13]. As the most common type of animal wax, yellow beeswax is a naturally generated honeybee biopolymer extracted from Apis mellifera and is composed of monocarboxylic acids (72 wt %), fatty acids (14 wt %), and hydrocarbons (11 wt %) [14,15]. With long-chain ester and carboxyl groups, beeswax is soluble in organic solvents including acetone and benzene but insoluble in water [16]. It is a GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe) substance as per the US Food and Drug Administration [17]. Due to its hydrophobic and biodegradable characteristics, beeswax is commonly utilized in food industries as a coating material to reduce the hygroscopicity of substances and improve their physical handling, including hardness and elasticity during transportation and storage [16,18]. Early studies have shown that beeswax coating enhances the physical barrier properties and lowers the solubilization capacity of hygroscopic biodegradable materials in water by 20%–50% [19,20]. Beeswax has been utilized in fruit coatings [21,22] and packaging [23] to prevent mold and moisture. Zhang et al. [24] also found that the hydrophobic beeswax-coated paper exhibited strong water vapor barrier properties, reducing water vapor transmission by more than 50% compared to the control. As a soil amendment, beeswax improved the photochemical efficiency of chlorophyll and catenoid content in borage (Borago officinalis), enhancing its resistance to drought stress and resulting in greater biomass production [25]. Moradi et al. [26] demonstrated that incorporating beeswax into biochar effectively improved Saffron (Crocus sativus L.) yields by immobilizing the toxic metal cadmium in the soil, leading to decreased cadmium-induced oxidative damage and reducing its partitioning into Saffron shoots. However, studies on the effects of nutrient content and the application methods of beeswax-coated fertilizers on plant growth and development are limited [20,27], with most research focusing on combined polymer coatings or the release of a single macronutrient.

In agriculture, beeswax-coated fertilizers have been shown to enhance physical handling and reduce moisture penetration [20]. Beeswax or wax formulated with ingredients such as kaolin, oil, and carbon black particles also improve soil diffusion barriers and insect control [28,29,30]. Ibrahim and Jibril [31] reported that paraffin wax-coated nitrogen and potassium-formulated fertilizers presented lower dissolution rates than uncoated fertilizers. The CRFs and SRFs were essential for plant safety and impacted plant nutrient uptake efficiency [10,32]. These fertilizers can reduce nutrient release rates, lower the local concentration of ions, alleviate osmotic stress, protect seedlings, and promote overall plant growth. However, the effects of macronutrient leaching from beeswax-only-coated fertilizers in soil on plants require further investigation for future applications.

In this study, beeswax was used to encapsulate the NPK fertilizers, and the dissolution rate of the active ingredients (ammonium, potassium, and total phosphorus) was evaluated to assess the impacts of beeswax coating on commercial fertilizers under water and soil conditions. The NPK nutrient leaching rates of uncoated and beeswax-coated fertilizers were measured to analyze the efficiency of beeswax-coating materials. The growth and development of maize applied with uncoated and beeswax-coated fertilizers were examined in a greenhouse experiment to clarify how beeswax-coated fertilizers affect the growth and quality of maize.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Wax Coating Procedure

The 16N-4P-8K fertilizer pellets were provided by Rainbow Fertilizer LLC (Americus, Georgia, GA, USA). The pellets were sieved to ensure uniform sizes, ranging from 2.00 to 2.80 mm, and weighed according to the designated weights for each experimental stage. A 10 L Stirring Water Bath (Major Science Co., Ltd., Saratoga, CA, USA) was set at 75 °C and 10 to 30 rpm to melt the beeswax. A 100 mL glass beaker filled with lab-grade beeswax (VWR International LLC, Secaucus, NJ, USA) was placed in the water bath using an iron stand. The water level in the stirring bath needed to be higher than the level of the melted wax to ensure complete melting. After the beeswax was fully melted in the glass beaker, fertilizer pellets were added and retrieved with a tweezer once the pellets were completely coated. The coated pellets were placed on the parchment paper (15.2 × 15.2 cm2) and cooled at room temperature for 24 h. After 24 h, excess wax on each pellet was trimmed off using a pocket knife. To 20 g of NPK fertilizers, 25.8 g of waxes were applied, resulting in a coating rate of 1.47 ± 0.01 (w/w).

W(g)Beeswax = W(g)Beeswax-coated NPK fertilizers − W(g)Uncoated fertilizers

2.2. Stage 1: Water Solubility Experiment

This experiment evaluated two treatments—uncoated fertilizers and beeswax-coated fertilizers—based on the method demonstrated by Huang et al. [22]. A total of 1.4 g of uncoated and beeswax-coated fertilizer pellets were placed inside one cotton tea bag (9.0 × 7.0 cm2) per replicate, and three replications were performed. Tea bags were secured and immersed in 210 mL of deionized water in a 250 mL sealed glass container with a magnetic stirrer. The jar was kept at ambient temperature and left undisturbed. A 2 mL sample was collected at specific time intervals: 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 24, and 48 h, as well as 7 and 14 days. For each sample collection, the lid was wrenched off and set aside. The tea bag containing fertilizers was removed and placed on the lid. The jar with the remaining slurry was transferred to a plate stirrer (Fisher Scientific LLC, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) and stirred at 200 rpm for one minute. After one minute, a 2 mL aqueous sample was drawn up in a 5 mL syringe and filtered through a 0.20-micron (DI) syringe filter before transferring to a 2 mL micro-centrifuge tube. The tea bag was re-immersed in the water after sample collection. To maintain a constant 210 mL of water in the jar, 2 mL of deionized water was added back. The slurry left on the lid was returned to the jar, and then the lid was resealed. Each treatment was replicated three times. Samples were stored in the freezer (−18 °C) for the subsequent NPK analysis.

The equation used to calculate the cumulative mass of NPK content released over time was as follows:

where m is the cumulative mass of NPK released from the fertilizer over time (g). Vs is the volume of each collected leachate sample (L). Ci is the measured NPK concentration in each sample (ppm or mg/L). Cn is the change in NPK concentration between two consecutive samples (ppm or mg/L). Vj is the total volume of slurry in the jar (L).

2.3. Stage 2: Leaching in Soil Columns

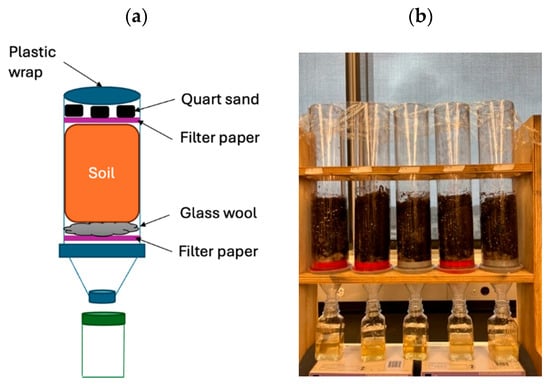

The soil leaching method was conducted according to Wang et al. [33] using 9 columns of PVC tubes (Acrux7, Shenzhen, China) (35 cm in length and 7 cm in diameter) with two wooden supports at room temperature. The lower end of the tube was securely attached to a plastic cap with small holes and a funnel (Figure 2a). A 250 mL sealed container was placed beneath the leaching apparatus to gather the leachate from the funnel. Two filter paper (94 mm in diameter) and glass wool were positioned on top of the plastic cap to minimize disturbance and soil loss during leaching. OM6 All Purpose soil (Berger Peat Moss Ltd.’s, PC, Saint-Modeste, QC, Canada) with the composition of 75%–81% sphagnum peat moss, 13%–17% perlite, 5%–9% composted peat moss, a wetting agent, and dolomitic and calcitic limestone was used for stage 2 and 3 experiments. The actual laboratory setup is presented in Figure 2b.

Figure 2.

The soil column experimental design and setup: (a) a schematic design of the soil column; (b) the actual laboratory setup used in the experiment (created by the authors).

As shown in Wang et al. [33] and considering the limited stability of beeswax, the leaching experiment lasted 14 days and included three treatments (a soil column without fertilizers, with uncoated fertilizers, and with beeswax-coated fertilizers). Three replications were performed for each treatment. Each PVC tube was packed with Berger OM6 soil with a bulk density of 160 kg m−3 to a depth of 150 mm. The soil column was initially added with approximately 380 mL of tap water to saturate each soil column. Then, 8 g each of uncoated fertilizer and beeswax-coated fertilizer were added to the soil surface. Subsequently, 200 mL of deionized water was added slowly to each column and allowed to drain for 48 h. This process was repeated six times in two weeks, resulting in a total of 1200 mL of added water. The PVC top columns were sealed with plastic film to avoid water evaporation after each water addition. The leachate was collected every 48 h before adding water and stored at 4 °C. Leachates were filtered before conducting the NPK analysis.

2.4. Stage 3: Leaching in the Greenhouse

This study applied a completely randomized block design with three treatments and five replicates for a total of 15 pots: soil without fertilizers, with uncoated fertilizers, and beeswax-coated fertilizers. The greenhouse was set at 22 °C and 24 h of artificial lighting. The polyethylene-lined plastic pots were 23 cm in height and 25 cm in diameter. Each pot was 12 cm apart from the other. Berger OM6 soil was sieved and weighed, and 1.5 kg of it was added in each pot. The soil in each pot was initially saturated with tempered water to optimize germination during the winter.

Maize seeds (cultivar P1185YHR) provided by Corteva AgriscienceTM (Johnston, IA, USA) were treated with fungicide, and three seeds were planted per pot. Seeds were buried 50 mm deep below the surface of Berger OM6 soil (pH = 5.5–6.5). At V1 (one true leave), plants were thinned to one plant per pot. Each fertilizer pot received 5.3 g of uncoated or beeswax-coated fertilizers. Pellets were evenly spread on the soil surface to mimic field conditions with water added every two to three days. Plant height was measured every week. Six weeks after planting (V7), all plants were cut at the stem base, close to the soil surface. Roots were rinsed with tap water to remove soil. Maize shoots and roots were dried separately in an oven at 68 °C for 72 h. Dried samples were ground and weighed before sending to the Midwest Laboratory (Omaha, NE, USA) for the N, P, and K content tests.

2.5. Evaluation of NPK Nutrient Content

2.5.1. Ammonium Testing

Ammonium ions were measured by the Ammonium Ion-selective Electrode (Cole-Parmer LLC, Vernon Hills, IL, USA). Calibration was performed before testing by serial dilution of a 1000 ppm ammonium standard solution. A 2 mL Ionic Strength Adjuster (ISA) solution (5 M NaCl) was added to each 100 mL sample to ensure a stable background ionic strength. For testing, 0.5 mL of the aqueous sample was diluted with 10 mL of deionized water in a 50 mL centrifuge testing tube. Then, 0.02 mL of the ISA solution was added, and the mixture was manually shaken for one minute. The ammonium electrode tip was immersed in the diluted sample until the concentration reading stabilized.

2.5.2. Potassium Testing

Potassium ions were measured by the Potassium Ion-selective Electrode (Cole-Parmer LLC., Vernon Hills, IL, USA). Calibration was performed before testing by serial dilution of a 1000 ppm potassium standard solution. A 2 mL Ionic Strength Adjuster (ISA) solution (5 M NaCl) was added to each 100 mL sample for a stable ionic strength. For testing, 0.5 mL aqueous sample was diluted with 10 mL of deionized water in a 50 mL testing tube. Then, 0.02 mL of the ISA solution was added, and the mixture was manually shaken for one minute. The potassium electrode tip was immersed in the diluted sample until the concentration reading stabilized.

2.5.3. Phosphorus Testing

The total amount of phosphorus released was quantified using the standard EPA Method 365: Phosphorous, All Forms (Colorimetric, Ascorbic Acid, Two Reagent) [34]. The measurement of total phosphorus encompasses all forms of phosphorus present in the sample, including total orthophosphate, total condensed phosphorus, and total organic phosphorus. A 0.25 mL aliquot was diluted with 50 mL deionized water in a 100 mL glass beaker. Then, 11 N sulfuric acid was added to the sample and heated until a volume of 40 mL was reached. This process was performed to convert any other types of phosphorus present into total orthophosphate. The resulting orthophosphate was then measured using the ascorbic acid method. A blue hue was produced by combining the sample with potassium antimonyl tartrate, ammonium molybdate, and ascorbic acid. The intensification of the blue color was examined using a UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (Azzota Scientific, Claymont, DE, USA) at a wavelength of 650 nm, corresponding to the phosphorus concentration in the aqueous samples.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The results were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) separately for each experimental stage. The effects of fertilizer coating were evaluated independently at each sampling time, and a one-way ANOVA was performed with fertilizer treatment as a single fixed factor to compare nutrient leaching, plant height, ash content, and root-to-shoot ratio, followed by Tukey’s test. The main effects were considered significant at 5% probability using JMP, version 17 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The figures were prepared using Microsoft Excel 2021 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Stage 1: Water Solubility Experiment

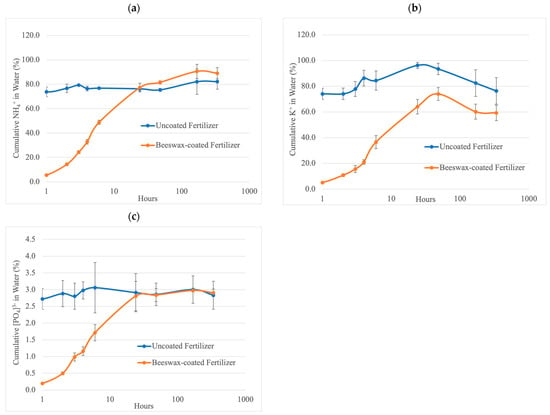

The nutrients released from uncoated and beeswax-coated fertilizers in water over two weeks were expressed as a percentage of the total nutrient content in the samples (Figure 3), calculated by dividing the total amount of nutrients released during dissolution by the total nutrient content of fertilizers. There was a significant difference in ammonium (N), potassium (K), and phosphorus (P) released within the first 24 h, and the release rates were lower for beeswax-coated fertilizers than uncoated fertilizers. There is no significant difference in N- and P-releasing patterns after 24 h between uncoated and beeswax-coated fertilizers. Both uncoated and beeswax-coated fertilizers released approximately 80% of ammonium and 3% of total phosphorus after 24 h. Beeswax-coated NPK fertilizers released approximately 60% potassium after 24 h, and uncoated fertilizers released 95%.

Figure 3.

Cumulative release of (a) ammonium, (b) potassium, and (c) total phosphorus from uncoated fertilizers (blue) and beeswax-coated fertilizers (orange) in a water solubility experiment within two weeks. Hours were log-transformed (log10) to normalize the distribution of the data. Error bars show the standard deviation of the mean (n = 3).

The uncoated fertilizers exhibited the highest NPK release within 0–1 h, whereas beeswax-coated fertilizers took 24 h. The difference demonstrated that granules with beeswax coating reduced the release rate of ammonium, potassium, and total phosphorus. This decrease in the release rate could be explained by the barrier effect of long-chain aliphatic hydrocarbons and non-polar carbon–hydrogen bonds from beeswax, which reduces the contact area between water and granule surfaces [35,36]. Ammonium, potassium, and phosphorus nutrient release patterns from uncoated and coated fertilizers increased during the first 24 h, followed by a steady-releasing rate between 24 and 336 h. Several studies have demonstrated a two-stage release pattern for encapsulated fertilizers with a transient state followed by a burst state [37,38,39,40]. In the transient state, water penetrated the granule core through cracks in the coating. This initiated fertilizer diffusion, driven by a higher water potential inside the granule compared to the outside environment. As the inside pressure increased and exceeded the coating’s tolerance threshold, the coating ruptured, leading to the rapid release of the remaining granule content. This mechanism resulted in a steady nutrient release pattern. With the hydrophobic properties of the beeswax coating, beeswax-coated fertilizers demonstrated a longer resistance to water penetration. Experimental results showed that the beeswax coating could withstand water exposure for approximately 24 h.

Currently, there are no comparative studies on the release of NPK macronutrients from beeswax-only-coated fertilizers in water solubility experiments. Baird et al. [20] reported that both uncoated and 1.5% candelilla wax-coated potassium fertilizers released 98% of the total potassium after 14 h, and the greatest difference in the two releasing patterns was observed in the first 2–3 h of dissolution, which was tested by pumping demineralized water through a polyethylene tube containing fertilizers. El Assimi et al. [29] observed that the chitosan-coated granules released phosphorus within 7 h and uncoated granules in 2 h in distilled water, whereas the double-coating approach (chitosan inside and paraffin wax outside) delayed the P release by 16 h. Candelilla wax is a renewable plant wax, while paraffin wax is a petroleum wax from crude soil, which shares similar components and hydrocarbon structures with beeswax [41,42]. Huang et al. [30] demonstrated that beeswax-coated thiamethoxam required approximately 1000 h to completely release its content in water, compared to 200 h for the uncoated control. This study also found that the release rate slowed down when 10% of beeswax was formulated with polyethylene or microcrystalline wax. These studies indicate that beeswax exhibits a strong water repellency among natural biodegradable polymers. A double-coating approach or formulations combined with beeswax may enhance barrier properties and reduce water vapor transmission.

3.2. Stage 2: Leaching in Soil Column Experiment

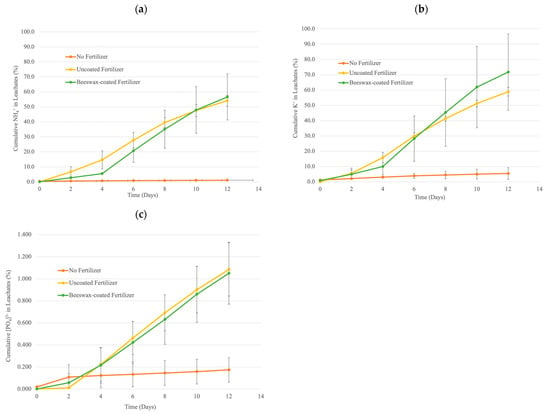

Beeswax-coated fertilizers indicated strong hydrophobicity characteristics from stage 1, delaying the N and P release for 24 h. During stage 2, fertilizers were placed on soil columns to further test the beeswax performance as a barrier against nutrient content leaching within the soil condition. Figure 4 shows the cumulative releases of NKP, expressed as percentages of the total nutrient content in the samples and calculated by dividing the cumulative ammonium (N), potassium (K), and phosphorus (P) released over time by the total nutrient content of the fertilizers. The total nutrient content of fertilizers is the sum of NPK nutrient content in soil and fertilizers. After two weeks, the soil column with no fertilizers exhibited a cumulative release of 1% ammonium, 5% potassium, and 0.2% total phosphorus. Soil columns treated with uncoated and beeswax-coated fertilizer exhibited a cumulative release of approximately 55% ammonium, 60%–65% potassium, and 1.1% total phosphorus after two weeks. The ammonium release rates at 0–4 days were significantly lower for beeswax-coated NPK fertilizers as compared to uncoated fertilizers. The soil column experiment found no significant effect of the beeswax coating on potassium and phosphorus nutrient releases.

Figure 4.

The cumulative release of (a) ammonium, (b) potassium, and (c) total phosphorus in a soil column experiment with no fertilizers (red), uncoated fertilizers (yellow), and beeswax-coated fertilizers (green) over a two-week period. Error bars show the standard deviation of the mean (n = 3).

Similar studies conducted by El Assimi et al. [29] on double-coated phosphate fertilizers (chitosan as the inner layer and paraffin wax as the outer layer) revealed that coated fertilizers released 20% of their phosphorus content after 25 days, whereas the uncoated fully dissolved after 24 days in the soil column experiment. Huang et al. [30] demonstrated the effectiveness of beeswax–kaolin coating over thiamethoxam (insecticide), observing that uncoated thiamethoxam (insecticide) released 100% of its content between 60 and 80 h in a soil column experiment, while beeswax–kaolin-coated thiamethoxan released approximately 40% of its content. Consistent with our results, the nutrient release pattern exhibits a linear trend in soil and a sigmoidal trend in water. Under the same conditions, beeswax–kaolin releases nutrients faster in water than in soil due to individual water content. The coating absorbs water and swells, but the relatively low water content in the soil slows water absorption and nutrient release. The release pattern observed by El Assimi et al. [29] showed a sigmoidal rather than a linear trend, likely due to the longer release period. In soil, the nutrient release pattern follows three phases: lag, linear release, and decay [12,43]. The sigmoidal release pattern emerges when coated fertilizers remain in the soil for an extended period, absorbing excessive water, releasing most nutrients from fertilizer granules, bursting the coating materials, and onsetting the decay phase [12,32,44].

The water repellency of beeswax is attributed to its hydrophobic substances including alkanes, esters, fatty acids, and alcohols, which can be biodegraded by soil microorganisms such as Pseudomonas and Bacillus species [45,46]. As these hydrophobic substances are degraded, the wax becomes more permeable allowing water to penetrate fertilizers. Additionally, beeswax composed of non-polar lipids is biodegradable, and soil conditions could accelerate the beeswax coating decomposition [45,47]. The beeswax coating influenced the ammonium release performance of coated NPK fertilizers, as shown in Figure 4. Our results may be slightly influenced by Berger OM6 soil, which contains 20 ppm ammonium, 100 ppm potassium, and 20 ppm phosphorus.

3.3. Stage 3: Greenhouse Experiment

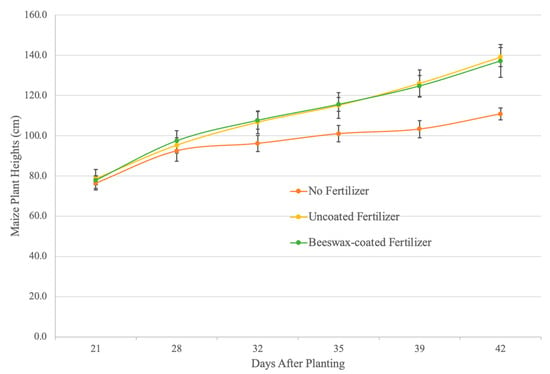

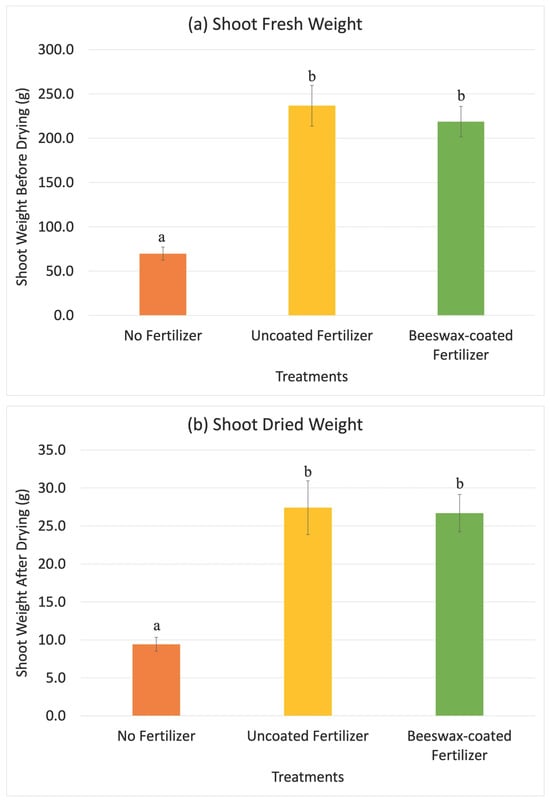

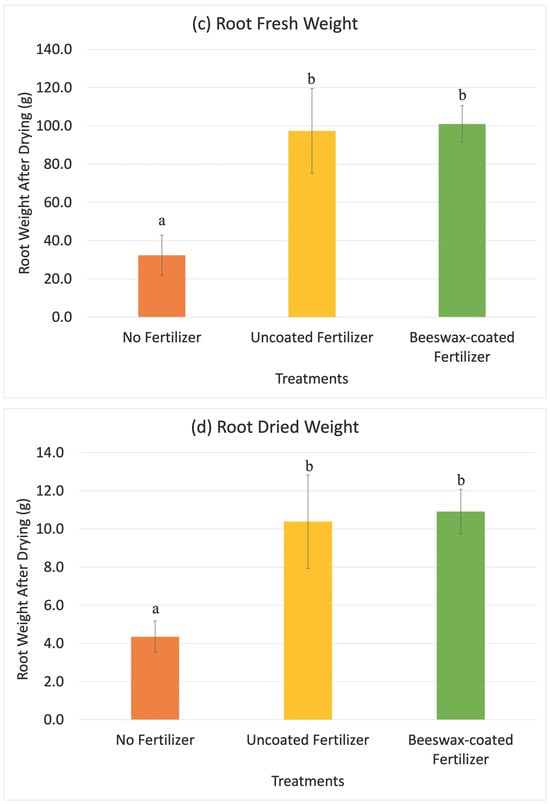

Maize was harvested after six weeks (V7 to V9 growth stages), when plants require large nutrient inputs and nutrient deficiencies become visually apparent [48]. Maize cultivated with both uncoated and beeswax-coated fertilizers were 139.1 cm ± 4.7 cm and 137.2 cm ± 8.1 cm in height compared to 110.8 cm ± 3.0 cm for the control group without fertilizers (Figure 5). Fertilizer application increased the maize height by approximately 27%, with no significant difference observed between the coated and uncoated fertilizers over the six weeks. Similar for shoot and root weights, fresh root weight was 32.3 g ± 11.7 g for maize grown without fertilizers, 97.4 g ± 24.7 g for uncoated fertilizers, and 101.0 g ± 10.7 g for coated fertilizers (Figure 6). After drying, root weights were 4.4 g ± 0.9 g for the control, 10.4 g ± 2.7 g for uncoated fertilizers, and 10.9 g ± 1.3 g for beeswax-coated fertilizers. Fresh shoot weights were 69.7 g ± 8.2 g for the control, 236.6 g ± 4.0 g for uncoated fertilizers, and 218.7 g ± 19.2 g for beeswax-coated fertilizers, while dried shoot weights were 9.4 g ± 1.0 g for the control, 27.4 g ± 4.0 g for uncoated fertilizer, and 26.7 g ± 2.8 g for beeswax-coated fertilizer treatments. There were significant differences in fresh and dried shoot weights between maize grown with and without fertilizers after six weeks, while no differences were observed between the uncoated and beeswax-coated NPK fertilizers for both root and shoot weights in fresh or dried states.

Figure 5.

The maize (cv. P1185 YHR) height when grown without fertilizers (red) and with uncoated fertilizers (yellow) and beeswax-coated fertilizers (green) during a six-week growth period. Error bars show the standard deviation of the mean (n = 5).

Figure 6.

The results of maize shoot fresh weight (a), shoot dried weight (b), root fresh weight (c), and root dried weight (d) 6 weeks after planting in the greenhouse experiment. Error bars show the standard deviation of the mean (n = 5). Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments (p < 0.05).

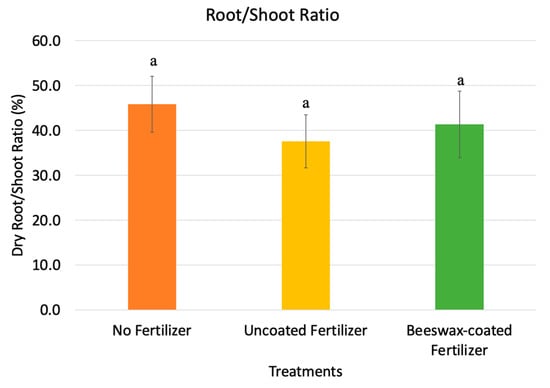

The dried root-to-shoot ratio of maize was 45% for no fertilizers, 40% for uncoated NPK fertilizers, and 42% for beeswax-coated fertilizers (Figure 7). Nutrient deficiencies in the soil can increase the root-to-shoot ratio, as plants develop extensive root systems to explore water and nutrients to support shoot growth [49]. The relatively higher root-to-shoot ratio observed in maize grown without fertilizers reflects the elongation of root hairs in response to nutrient shortages [50,51]. No significant differences were observed between maize grown with uncoated and beeswax-coated fertilizers, suggesting efficient nutrient release from both types. This indicates that the beeswax coating had a limited impact on nutrient release during the six-week experiment. In the previous laboratory soil column experiment, the beeswax coating ruptured after day six in Berger OM6 soil. This short coating duration was likely insufficient to cause significant differences in plant height, shoot weight, or root weight over the six-week period.

Figure 7.

Root-to-shoot ratio of maize grown with no fertilizers, with commercial NPK fertilizers, and with beeswax-coated fertilizers after drying. Error bars show the standard deviation of the mean (n = 5). Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments (p < 0.05).

Nitrogen, potassium, and phosphorus are essential nutrient components for leaf biomass and cell development in young plants [52]. Table 1 presents the NPK percentages on a dry matter basis tested by the Midwest Laboratory, showing the influence of fertilizer dissolution on plant biomass. Due to limited sample collection, no replication was performed for these results. The nitrogen percentage on a dry matter basis was 0.58% for maize grown without fertilizers, 1.04% for uncoated fertilizers, and 1.00% for beeswax-coated fertilizers. Phosphorus percentages were similar across treatments, ranging from 0.33% to 0.34%. Potassium percentages on a dry matter basis were 3.08% for the control, 2.58% for uncoated fertilizers, and 2.77% for beeswax-coated fertilizers. The nutrient percentages on a dry matter basis may have been influenced by the initial nutrient content of Berger OM6 soil used in experiments 2 and 3. Comparing the NPK content of maize plants, the effectiveness of the beeswax coating in limiting nutrient uptake was found to be minimal. This may be attributed to the limited persistence of the beeswax coating under soil conditions, which likely accelerated its degradation compared to water conditions.

Table 1.

Nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium content in maize roots and shoots (combined) on a dry matter basis from no fertilizer, uncoated fertilizer, and beeswax-coated fertilizer treatments.

Based on the water and soil results, the long hydrocarbon chains in beeswax provide strong water repellency for the fertilizer granules, effectively reducing NPK leaching during the first 24 h. This suggests that the persistence of the beeswax coating in the water system is approximately 24 h. In contrast, the performance of the beeswax coating in soil is influenced by multiple environmental factors, including diverse microbial communities, organic matter, fluctuating moisture, temperature, pH, and UV exposure [53,54]. These factors weaken the integrity of the beeswax coating through biological or chemical degradation of its hydrophobic components. Once water penetrates the coating, surface cracking occurs, allowing increased water infiltration until the coating ultimately fails. Dahal et al. [55] also demonstrated that beeswax degradation in soil is affected by coating thickness and material dimensions. This study blended soy wax with beeswax to create a thicker wax layer with a lower surface-area-to-mass ratio, which extended the degradation period by reducing exposure to soil microbes.

4. Conclusions

The beeswax-coated NPK fertilizer demonstrated a significant difference in ammonium, potassium, and phosphorus release during the water solubility experiment within the first 24 h. Compared to uncoated fertilizers, the beeswax coating effectively extended nutrient dissolution to approximately 24 h under water conditions. In the soil column analysis, the beeswax-coated fertilizer (14.7%) exhibited a significantly different ammonium release pattern compared to uncoated fertilizers (5.5%) during the first four days. However, potassium and phosphorus release patterns showed no significant differences between the two treatments. Furthermore, greenhouse experiments revealed no significant differences in maize plant height, nitrogen, potassium, and phosphorus content in shoots and roots, or root and shoot weights between plants treated with coated and uncoated fertilizers. These findings indicate that the effectiveness of the beeswax coating was limited to approximately 24 h in water and less than four days under soil conditions. This study demonstrates that beeswax coating, an environmentally friendly material with strong water barrier properties, can effectively extend NPK release periods, particularly in water.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, Z.P.; Writing—review & editing, S.F. and L.L.; Supervision, S.F. and L.L.; Funding acquisition, L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported, in part, by the farm families of Minnesota and their corn checkoff investment. This work was also supported by the State of Iowa Biosciences Initiative.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

I sincerely thank D. Raj Raman and Matt Helmers for their insightful ideas, assistance with calculations, and extensive guidance. I would also like to thank Hoa M. Chi for his help in designing and constructing the soil leaching column setups, as well as Peter A Lawlor for his guidance in greenhouse planting.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Keena, M.; Meehan, M.; Scherer, T. Nitrogen Behavior in the Environment; NDSU Agriculture: Fargo, ND, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Goulding, K.; Murrell, T.S.; Mikkelsen, R.L.; Rosolem, C.; Johnston, J.; Wang, H.; Alfaro, M.A. Outputs: Potassium Losses from Agricultural Systems. In Improving Potassium Recommendations for Agricultural Crops; Murrell, T.S., Mikkelsen, R.L., Sulewski, G., Norton, R., Thompson, M.L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lory, J.A. Agricultural Phosphorus and Water Quality|MU Extension; MU Extension: Columbia, MO, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Holford, I.C.R. Soil phosphorus: Its measurement, and its uptake by plants. Soil Res. 1997, 35, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachtman, D.P.; Reid, R.J.; Ayling, S.M. Phosphorus Uptake by Plants: From Soil to Cell. Plant Physiol. 1998, 116, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crosby, G. The Nutrient Challenge of Sustainable Fertilizer Management|USDA; U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2016.

- South Dakota State University Extension. Corn. S-0003-31, 2019. South Dakota State University Extension. Available online: https://extension.sdstate.edu/sites/default/files/2019-09/S-0003-31-Corn.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Wang, Y.; Yao, Z.; Zheng, X.; Subramaniam, L.; Butterbach-Bahl, K. A synthesis of nitric oxide emissions across global fertilized croplands from crop-specific emission factors. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 4395–4408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blouin, G.M.; Rindt, D.W. Method of Making Sulfur-Coated Fertilizer Pellet Having a Controlled Dissolution Rate. United. States Patent US3295950A, 3 January 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Shaviv, A. Advances in Controlled-Release Fertilizers. In Advances in Agronomy; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001; Volume 71, pp. 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Kost, J.; Fishman, M.L.; Hicks, K.B. A Review: Controlled Release Systems for Agricultural and Food Applications. In New Delivery Systems for Controlled Drug Release from Naturally Occurring Materials; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; Volume 992, pp. 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrencia, D.; Wong, S.K.; Low, D.Y.S.; Goh, B.H.; Goh, J.K.; Ruktanonchai, U.R.; Soottitantawat, A.; Lee, L.H.; Tang, S.Y. Controlled Release Fertilizers: A Review on Coating Materials and Mechanism of Release. Plants 2021, 10, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijaljica, D.; Townley, J.P.; Spada, F.; Harrison, I.P. The heterogeneity and complexity of skin surface lipids in human skin health and disease. Prog. Lipid Res. 2024, 93, 101264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulloch, A.P. The composition of beeswax and other waxes secreted by insects. Lipids 1970, 5, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulloch, A.P. Beeswax—Composition and Analysis. Bee World 1980, 61, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, J.; Athmaselvi, K.A. Chapter 5—Report on Edible Films and Coatings. In Food Packaging and Preservation; Grumezescu, A.M., Holban, A.M., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 177–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Service. Substances Added to Food; U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2025.

- Navarro-Tarazaga, M.L.; Massa, A.; Pérez-Gago, M.B. Effect of beeswax content on hydroxypropyl methylcellulose-based edible film properties and postharvest quality of coated plums (Cv. Angeleno). LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 44, 2328–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, M.O.; Olivato, J.B.; Bilck, A.P.; Zanela, J.; Grossmann, M.V.E.; Yamashita, F. Biodegradable trays of thermoplastic starch/poly (lactic acid) coated with beeswax. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 112, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, R.J.; Kabiri, S.; Degryse, F.; da Silva, R.C.; Andelkovic, I.; McLaughlin, M.J. Hydrophobic coatings for granular fertilizers to improve physical handling and nutrient delivery. Powder Technol. 2023, 424, 118521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrin, T.A.A.; Arfin, M.S.; Rahman Md, A.; Molla, M.M.; Sabuz, A.A.; Matin, M.A. Influence of novel coconut oil and beeswax edible coating and MAP on postharvest shelf life and quality attributes of lemon at low temperature. Meas. Food 2023, 10, 100084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eda, R. Influence of organic manures and fruit coatings on biochemical parameters of papaya cv. Arka Prabhat. Int. J. Minor Fruits Med. Aromat. Plants 2023, 9, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaireh, S.; Ngasatool, P.; Kaewtatip, K. Novel composite foam made from starch and water hyacinth with beeswax coating for food packaging applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 165, 1382–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Xiao, H.; Qian, L. Enhanced water vapour barrier and grease resistance of paper bilayer-coated with chitosan and beeswax. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 101, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourghasemia, N.; Moradi, R. Potential of using beeswax waste as the substrate for borage (Borago officinalis) planting in different irrigation regimes. J. Plant Process Funct. 2018, 7, 163–178. [Google Scholar]

- Moradi, R.; Pourghasemian, N.; Naghizadeh, M. Effect of beeswax waste biochar on growth, physiology and cadmium uptake in saffron. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 1251–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoenchai, M.; Prompinit, P.; Kangwansupamonkon, W.; Vayachuta, L. Bio-inspired Surface Structure for Slow-release of Urea Fertilizer. J. Bionic Eng. 2020, 17, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, D.; Prasad, R.; Brantley, E. Phosphorus Basics: Understanding Pathways of Soil Phosphorus Loss; Alabama Cooperative Extension System: Anniston, AL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- El Assimi, T.; Lakbita, O.; El Meziane, A.; Khouloud, M.; Dahchour, A.; Beniazza, R.; Boulif, R.; Raihane, M.; Lahcini, M. Sustainable coating material based on chitosan-clay composite and paraffin wax for slow-release DAP fertilizer. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 161, 492–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Hu, Q.; Cui, G.; Guo, X.; Wei, B.; Gan, C.; Li, W.; Mo, D.; Lu, R.; Cui, J. Release-controlled microcapsules of thiamethoxam encapsulated in beeswax and their application in field. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part B 2020, 55, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.A.; Jibril, B.Y. Controlled Release of Paraffin Wax/Rosin-Coated Fertilizers. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2005, 44, 2288–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sempeho, S.I.; Kim, H.T.; Mubofu, E.; Hilonga, A. Meticulous Overview on the Controlled Release Fertilizers. Adv. Chem. 2014, 2014, 363071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liang, T.; Chong, Z.; Zhang, C. Effects of soil type on leaching and runoff transport of rare earth elements and phosphorous in laboratory experiments. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2011, 18, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Phosphorous, All Forms (Colorimetric, Ascorbic Acid, Two-Reagent): Method 365.3. EPA. 1978. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-08/documents/method_365-3_1978.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Shellhammer, T.H.; Rumsey, T.R.; Krochta, J.M. Viscoelastic properties of edible lipids. J. Food Eng. 1997, 33, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Diak, O.A.; Andrews, G.P.; Jones, D.S. Hydrophobic Polymers of Pharmaceutical Significance. In Fundamentals and Applications of Controlled Release Drug Delivery; Siepmann, J., Siegel, R.A., Rathbone, M.J., Eds.; Springer US: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 47–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beig, B.; Niazi, M.B.K.; Jahan, Z.; Kakar, S.J.; Shah, G.A.; Shahid, M.; Zia, M.; Haq, M.U.; Rashid, M.I. Biodegradable Polymer Coated Granular Urea Slows Down N Release Kinetics and Improves Spinach Productivity. Polymers 2020, 12, 2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Du, C.; Li, T.; Shen, Y.; Zhou, J. Thermal post-treatment alters nutrient release from a controlled-release fertilizer coated with a waterborne polymer. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 13820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanafi, M.M.; Eltaib, S.M.; Ahmad, M.B.; Syed Omar, S.R. Evaluation of controlled-release compound fertilizers in soil. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2002, 33, 1139–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yolles, S. Controlled Release of Biologically Active Agents. In Polymers in Medicine and Surgery; Kronenthal, R.L., Oser, Z., Martin, E., Eds.; Springer US: New York, NY, USA, 1975; pp. 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, H.L. Significance of Tests for Petroleum Products 9th Edition; ASTM International: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saji, V.S. Wax-based artificial superhydrophobic surfaces and coatings. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2020, 602, 125132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaviv, A.; Raban, S.; Zaidel, E. Modeling Controlled Nutrient Release from Polymer Coated Fertilizers: Diffusion Release from Single Granules. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 2251–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenkel, M.E. Slow- and Controlled-Release and Stabilized Fertilizers: An Option for Enhancing Nutrient Use Efficiency in Agriculture, 2nd ed.; IFA (International Fertilizer Industry Association): Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hanstveit, A.O. Biodegradability of petroleum waxes and beeswax in an adapted CO2 evolution test. Chemosphere 1992, 25, 605–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthuvelu, V. Studies on Wax Degrading Microorganisms and Its Effect on Decomposition of Sugarcane Bagasse. 2008. Available online: https://share.google/XcppLsuE4IrkRiHop (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Bílková, L.; Bartl, B.; Zapletal, M. Resistance of Beeswax to Organic Solvents from a Conservator’s Perspective. Stud. Conserv. 2024, 70, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransom, J.; Endres, G. Corn Growth and Management Quick Guide; NDSU Agriculture: Fargo, ND, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer, R. Nutritive influences on the distribution of dry matter in the plant. Neth. J. Agric. Sci. 1962, 10, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giehl, R.F.H.; von Wirén, N. Root Nutrient Foraging1. Plant Physiol. 2014, 166, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigas, S.; Debrosses, G.; Haralampidis, K.; Vicente-Agullo, F.; Feldmann, K.A.; Grabov, A.; Dolan, L.; Hatzopoulos, P. TRH1 Encodes a Potassium Transporter Required for Tip Growth in Arabidopsis Root Hairs. Plant Cell 2001, 13, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardans, J.; Peñuelas, J. Potassium Control of Plant Functions: Ecological and Agricultural Implications. Plants 2021, 10, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Zotarelli, L.; Li, Y.; Dinkins, D.; Wang, Q.; Ozores-Hampton, M. Controlled-Release and Slow-Release Fertilizers as Nutrient Management Tools: HS1255/HS1255, 10/2014. EDIS 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Y.; Timar, M.C.; Varodi, A.M. A comparative study on the artificial UV and natural ageing of beeswax and Chinese wax and influence of wax finishing on the ageing of Chinese Ash (Fraxinus mandshurica) wood surfaces. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2019, 201, 111607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahal, S.; Yilma, W.; Sui, Y.; Atreya, M.; Bryan, S.; Davis, V.; Whiting, G.L.; Khosla, R. Degradability of Biodegradable Soil Moisture Sensor Components and Their Effect on Maize (Zea mays L.) Growth. Sensors 2020, 20, 6154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).