Abstract

Circular concrete-filled steel tube columns prepared with 100% recycled aggregate concrete (RACFST) are of interest for sustainable, carbon-neutral construction. However, recycled aggregates typically have higher water absorption and lower stiffness, raising concerns about seismic performance. This paper investigates the low-cycle cyclic behavior and displacement ductility of circular RACFST columns. Ten short columns were tested under an axial load ratio of ≈0.20, with varying diameters of 165 and 219 mm and concrete strengths of C30, C40, and C50, along with companion natural-aggregate CFST control specimens. A three-dimensional finite element model was developed and calibrated based on the test results, and parametric simulations were conducted to study the effects of geometry and material parameters. Two distinct flexural failure modes with outward bulging at the base were observed. These two distinct flexural failure modes refer to (1) local outward bulging of the steel tube accompanied by buckling near the base (e.g., specimens RACFSTC40-165-1 and RACFSTC30-219-1) and (2) flexural yielding with extensive concrete crushing around the base region (e.g., specimens RACFSTC50-219-2 and FSTC40-219-2). The first mode was characterized by early steel local deformation and shell instability, while the second showed more distributed plasticity with crushing of recycled aggregate concrete. These modes underline the influence of D/t and concrete strength on failure progression. The results indicate that RACFST columns attain a peak strength comparable to conventional CFST, while achieving significantly greater drift ductility and energy dissipation; the equivalent viscous damping ratio was found to increase with drift at ≈0.04–0.08 for low drifts and ≈0.10–0.18 for moderate drifts, suggesting that existing CFST design provisions are applicable, with only a minor ~3–5% reduction in core concrete strength recommended for stability.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the push for carbon neutrality has driven interest in reusing construction waste materials. Recycled aggregate concrete (RAC) is produced by processing demolished concrete by crushing, washing, and grading it to re-enter the construction cycle. This approach not only conserves resources but also aligns with sustainability goals. However, recycled aggregates retain residual mortar and porosity, resulting in higher water absorption, lower elastic moduli, and greater strength variability than natural aggregates. Concrete-filled steel tube (CFST) columns are widely used in seismic design due to their composite action: the steel tube provides tri-axial confinement of the concrete core, delaying cracking and crushing, while the concrete infill supports the steel, preventing local buckling, yielding high ductility and energy dissipation [1]. Incorporating RAC into CFST columns, forming RACFST, can potentially offset the material limitations through the synergy of the composite system, improving both structural performance and environmental benefits [2]. Nevertheless, under the extreme condition of 100% recycled coarse and fine aggregate replacement, fundamental questions remain about the seismic response: Will the hysteresis loops suffer pronounced pinching? Will stiffness degrade more rapidly? Are post-peak softening and residual drifts controllable? These issues require thorough experimental and analytical investigation. From a regulatory standpoint, the presence of residual mortar in recycled aggregates introduces concerns related to long-term durability. Residual mortar tends to increase porosity and water absorption, which can accelerate chloride ingress and freeze–thaw damage—two critical durability parameters in most national building codes. Although some standards such as the Chinese GB/T 25177 and Eurocode EN 206 allow limited use of recycled aggregates, they often impose stricter testing for durability (e.g., rapid chloride permeability, drying shrinkage, and sulfate resistance). For structural safety and service life assurance, RACFST systems employing 100% recycled content may require modified mix proportions, advanced surface treatments, or supplementary cementitious materials such as fly ash or silica fume. Additional experimental verification is recommended to ensure full compliance with evolving durability criteria in global low-carbon construction codes.

Various studies have examined CFST behavior and the use of recycled concrete in structures, but full-scale evaluation of RACFST columns under cyclic loads is still limited. Feng [3] recently tested circular RACFST specimens under low-cycle loading and observed flexural-dominated failures with outward bulging at the base; notably, the RACFST columns reached similar peak strengths to conventional CFST, while exhibiting superior displacement ductility and energy dissipation. Despite these promising findings, a systematic understanding of hysteretic characteristics, such as pinching effects, stiffness degradation, and strength deterioration, and the influence of key parameters, such as section geometry, concrete strength, axial load, etc., is incomplete. In particular, calibrated numerical models are needed to generalize the behavior and support design guidance [4]. Unlike prior studies which often used partial recycled aggregate replacement, this work employs 100% recycled coarse and fine aggregate in the concrete core, addressing a gap in the literature. Few international studies have tested fully recycled CFST under seismic loads; our systematic tests extend these results by varying diameter and concrete strength for full replacement. This paper addresses these gaps by combining experimental tests and numerical simulation. First, ten low-cycle reversed-cyclic tests were conducted on short circular CFST columns with two diameters (165 mm and 219 mm), three RAC concrete strengths (C30, C40, and C50), and a constant axial load ratio (η ≈ 0.20). The axial load ratio (η ≈ 0.20) was selected to represent a moderate service-level gravity load typical of mid-rise building columns under seismic design. Companion specimens with natural aggregate concrete were tested for comparison. The experiments characterized the failure modes, hysteretic backbone, and ductility of the RACFST columns [5]. Next, a three-dimensional finite element model was established in ABAQUS and calibrated against the experimental results. This validated model was then used in a parametric study to examine the effects of section size, wall thickness, axial load, and material properties on the cyclic response. Through this combined approach, the paper provides insight into the design and analysis of RACFST columns under seismic loading. To clearly differentiate this study from previous works, we emphasize three key innovations: (1) the use of 100% recycled coarse and fine aggregates in circular CFST columns under cyclic loading; (2) the extensive parametric variation in column diameter (165–219 mm), concrete strength (C30–C50), and axial load ratio (η ≈ 0.20); and (3) the integration of both experimental and validated finite element (FE) simulation to generalize findings. Compared to prior studies, such as those of Bao Hua [1] and Feng [3], which used partial replacement or limited test matrices, our study broadens the understanding of RACFST behavior under seismic demands. Moreover, international contributions on CFST hysteretic performance and recycled concrete mechanics are incorporated to situate our findings within a global research context.

2. Experimental Scheme

2.1. Experimental Introduction

Ten short circular columns were fabricated as test specimens. The specimens had outer diameters of either 165 or 219 mm and a uniform wall thickness of 4 mm, giving shear–span ratios (L/D) of about 5.5–7.3. This L/D range reflects typical proportions in short-to-medium columns of mid-rise buildings. However, we acknowledge that generalization to taller columns (L/D > 8) may require further study, as slenderness effects and second-order behavior could alter the failure modes and hysteretic response. Future work will extend testing to taller specimens. The steel tubes were composed of Q235B seamless steel with a yield strength ≈ 235 MPa and an elastic modulus ≈ 200 GPa, welded with an anti-corrosion coating. The concrete core in the RACFST columns was composed of 100% recycled coarse and fine aggregates obtained from crushed waste concrete; nominal strengths of C30, C40, or C50 were targeted. The relevant mechanical properties and mix proportions of the materials are detailed in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5.

Table 1.

Physical and mechanical properties of cement.

Table 2.

Physical and mechanical properties of recycled fine aggregate.

Table 3.

Physical and mechanical properties of recycled coarse aggregate.

Table 4.

Representative mix proportions and aggregate replacement strategy.

Table 5.

Compressive strength of concrete test blocks.

Table 5 shows the compressive strengths measured from the companion concrete specimens corresponding to each test column. All measured values met the experimental requirements. Steel coupon tests on Q235B tubes yielded a mean yield strength of 235 MPa and an ultimate tensile strength of approximately 360 MPa, with an elastic modulus of ~200 GPa. These values were used for numerical model calibration and to compute design axial load capacities, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Specimen design parameters and sectional properties.

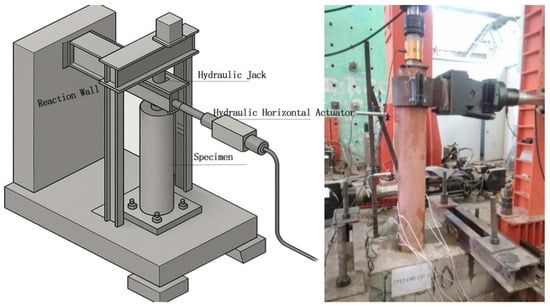

A hydraulic jack applied a constant axial force through a load cell to maintain η ≈ 0.20 of the design capacity, while a horizontal servo-actuator mounted on a reaction wall imposed lateral cyclic displacements at the column top (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Loading device and reaction system diagram.

Displacement transducers (LVDTs) measured the lateral displacements at the base and top, and strain gauges were attached to the steel tube at heights of 30, 80, 150, and 220 mm above the base to capture local buckling strains [6].

2.2. Experimental Design and Procedure

Table 6 summarizes the test matrix. In total, ten columns were tested: eight RACFST specimens and two conventional CFST control specimens (natural aggregate concrete, D = 219 mm, C40 strength).

Standard cylinder tests confirmed 28-day compressive strengths of approximately 30.5, 40.2, and 52.7 MPa for the RAC mixes labeled C30, C40, and C50, respectively. Steel tube coupons (Q235B) tested in tension yielded at ≈235 MPa, with an ultimate breaking point at ≈360 MPa, consistent with the material specifications. This provides the measured concrete and steel properties.

The main variables were column diameter and concrete strength. All tests followed a displacement-controlled cyclic protocol. First, a small preload of ±5 kN was applied to set the system. Then the constant axial load η ≈ 0.20 was applied. Lateral loading proceeded in a four-stage sequence: (1) force-controlled increments of 5 kN were applied up to near 3 cycles per step; (2) displacement control was then used through target drift levels corresponding to top displacements (Δ = 4, 8, 12, 16, 24, 32, and 40 mm, 3 cycles at each level); (3) the test was terminated when the lateral load dropped to 85% of the maximum Fmax or the drift angle reached 1/30 ≈ 3.3%. This loading regimen conforms to standard seismic test guidelines. During each test, the axial force was held constant, and the lateral force and displacement were recorded cycle-by-cycle to construct hysteresis plots [7,8].

2.3. Experimental Results

All specimens exhibited flexural bending behavior. In the early cycles, minor concrete cracking and low steel yielding occurred without strength loss. As the drift increased, a plastic hinge formed near the base, and the steel tube showed outward bulging (Figure 2). Smaller columns such as the D = 165 mm specimens typically showed the first failure mode with localized bulging, while larger columns (D = 219) mm often exhibited the second failure mode with distributed flexural yielding and dual hinge formation (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Outward bulging and buckling failure mode at the column base.

No sudden shear or brittle failure was observed. Compared to the control columns, the RACFST specimens developed slightly larger local bulging and more complete concrete crushing, which introduced mild pinching of the hysteresis loops at the largest drifts.

Although the observed pinching was mild and did not compromise energy dissipation, it may signal moderate localized damage such as concrete crushing and partial debonding near the plastic hinge zone. From a repairability standpoint, such behavior suggests that while global column integrity is retained, some cosmetic and localized structural repairs may be required after major seismic events. Further study is warranted to quantify repair costs and residual drift implications. However, the strong confinement of the steel prevented severe degradation; the hysteresis loops remained full and robust, indicating substantial energy dissipation. Larger-diameter columns (D = 219 mm) showed less pronounced bulging and slower stiffness degradation than the smaller 165 mm columns. Similarly, using higher-strength RAC C50 raised the peak load but marginally reduced the yield displacement. These trends suggest that greater geometric confinement can mitigate the weaker RAC material, while higher-strength RAC improves capacity at a modest cost in ductility. Damage was concentrated near the base, and an effective plastic hinge length (

) was used in the analysis employing Equation (1) [9], derived from the observations shown in Figure 2.

In the equation, Lp denotes the equivalent length of the plastic zone at the column base; α1 and α2 are regression coefficients. Lp reflects the extent of the equivalent plastic hinge region under bending-dominated failure. The value range of Equation (1) is consistent with the experimental observations within the tested specimen dimensions and axial load levels.

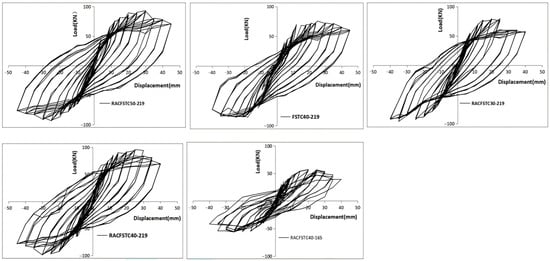

Figure 3 shows typical hysteresis loops. All loops were nearly symmetric and spindle -shaped—i.e., with gradually widening widths in mid-drift cycles, followed by narrowing at extreme drifts—around the origin. This qualitative descriptor corresponds to the smooth degradation in stiffness and energy dissipation observed in RACFST specimens. In general, the RACFST specimens had larger loop areas than the NAC controls, implying better energy dissipation.

Figure 3.

Hysteresis curves.

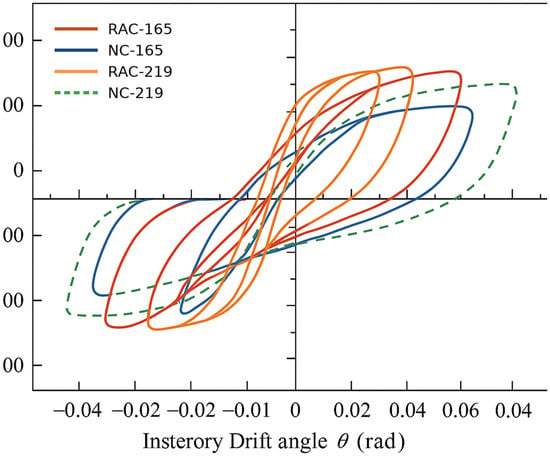

Figure 4 compares the backbone envelope of an RACFST versus a control specimen: the RACFST backbone is fuller with less pinching. Mechanistically, the fuller loops in RACFST columns are attributed to the lower stiffness and more gradual cracking of recycled concrete, which causes smoother unloading/reloading and less sudden strength loss. The steel tube in RACFST also yields more progressively under bending, distributing strain more uniformly. These factors combine to maintain loop width and reduce pinching compared to NAC cores. Figure 4 overlays representative hysteresis curves for RACFST and NAC specimens to illustrate the improved loop shape and reduced pinching. Increasing the diameter from 165 to 219 mm produced fuller loops and a flatter post-peak decay; higher RAC strength increased the peak load but slightly reduced the yield drift.

Figure 4.

Comparison of hysteresis curves between recycled and natural aggregate concrete.

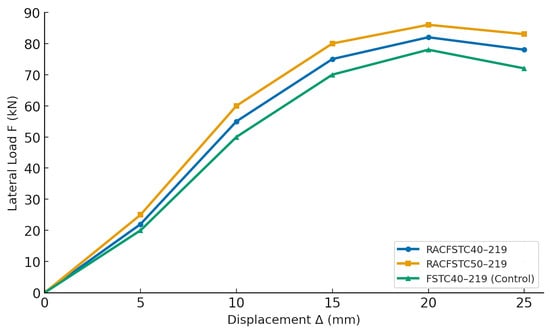

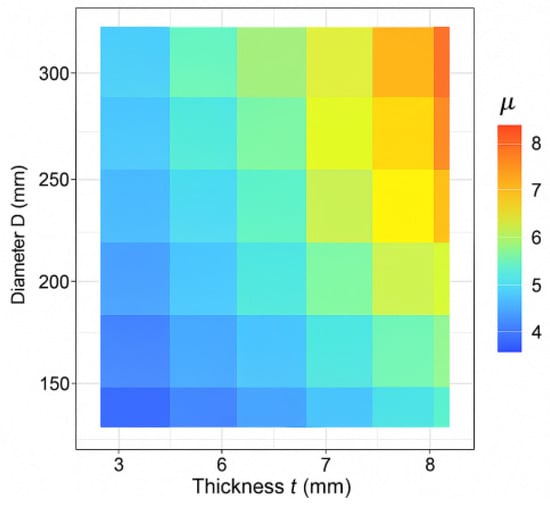

For example, the 219 × 4–C50 specimens exhibited the highest Fmax and gentle post-peak degradation, whereas the 165 × 4–C40 specimens with the smallest D/t showed more pinching and rapid stiffness loss. Backbone envelope curves were extracted by connecting peak points and fitted to a tri-linear elastic–yield–peak softening model. From these fits it was found that increasing fc by one class raised Fmax by ~10–15% but slightly decreased the displacement ductility (μ), while decreasing the D/t ratio significantly increased μ and reduced the softening slope (see Figure 5). A parametric plot of μ versus D/t and fc (Figure 6) confirmed that ductility increases as D/t decreases.

Figure 5.

Comparison of skeleton envelope curves.

Figure 6.

Heat map of displacement ductility (μ) parameter.

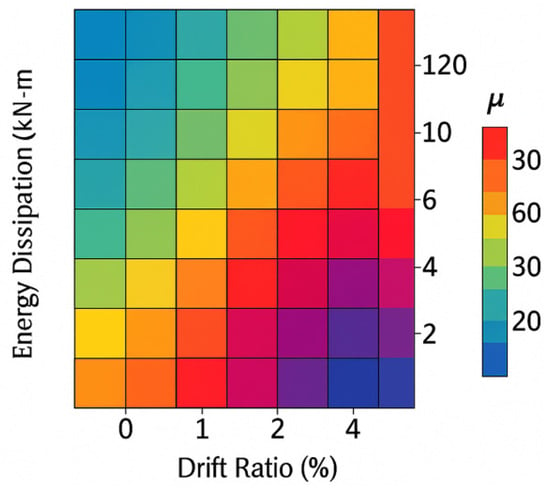

The energy dissipation and damping were also quantified. Cumulative hysteretic energy sum of loop areas grew monotonically with drift (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Variation in cumulative hysteretic energy with drift ratio.

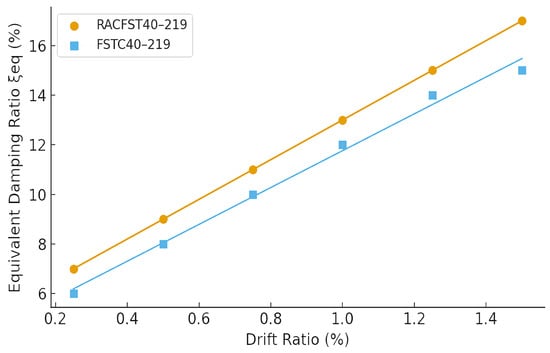

The equivalent viscous damping ratio (ξeq), classically defined using the loop area (Equation (2)) [10], increased steadily with drift (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Variation in equivalent viscous damping ratio (ξeq) with drift ratio.

In the equation,

is the equivalent viscous damping at the (i)-th displacement level;

is the area of a single hysteresis loop energy dissipation at the (i)-th displacement level; and

is the equivalent (secant) stiffness at the (i)-th displacement level.

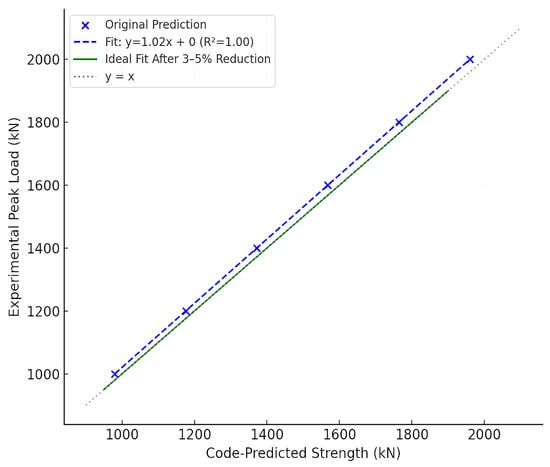

For the RACFST group, ξeq was about 0.04–0.08 at drift ≤ 1% and about 0.10–0.18 at 2–3% drift [11]. These values, comparable to highly ductile systems, indicate substantial energy capacity. Based on this, we recommend using ξeq ≈ 0.04–0.08 for service-level drifts and ≈0.10–0.18 for stronger drifts of ~2–3% in seismic design [12]. Meanwhile, the measured stiffness and strength degradation followed expected patterns and were well fitted by empirical models [13]. A test-to-code comparison plot of experimental versus code-predicted strength yielded a slope ≈ 1.00 and R2 ≈ 0.98, suggesting that existing CFST design formulas apply to RACFST columns in the tested range, provided that the core concrete design strength is reduced by ~3–5% to ensure post-peak stability [14]. For strength prediction, we applied Eurocode 4 (EN1994-1-1 [15]) and the Chinese code GB 50936-2014 [16] for circular CFST columns. The regression of experimental versus code strengths (Figure 9) yielded a slope of 1.02 (R2 = 0.99) for the control mix. Introducing a 3–5% reduction in f′c yielded an improved mean ratio of unity, justifying our recommendation. We note this calibration applies to short columns (L/D ≤ 7.3) at η ≈ 0.20.

Figure 9.

Axial load versus lateral drift: comparison of experimental peak strengths and design code predictions.

Figure 9 presents the scatter plot comparing tested and code-predicted strengths. This demonstrates the applicability of EC4 and GB formulas to RACFST when adjusted conservatively. The 3–5% strength reduction was iteratively calibrated to ensure that predicted strengths conservatively bounded all test results, thus improving alignment with experimental peak loads while accounting for RAC variability.

3. Numerical Model

3.1. Definition of Numerical Model

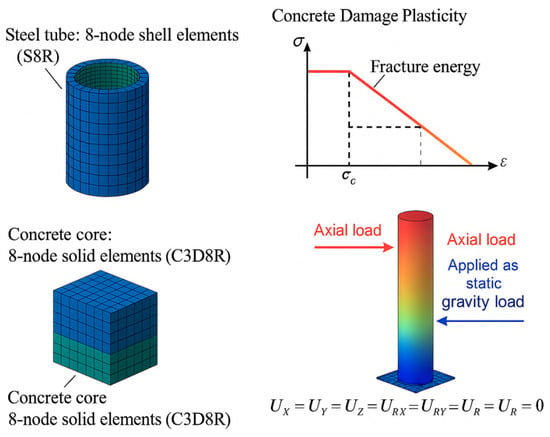

A 3D finite element model was developed in ABAQUS to simulate the RACFST columns under cyclic loading. The steel tube was modeled with eight-node shell elements (S8R) and the concrete core with eight-node solid elements (C3D8R) [17]. A perfect bond tie constraint was assumed between the steel and concrete. This idealized bond is justified by the continuous welds and intact interface of the column: previous studies (e.g., Ma et al.’s [17]) have shown minimal slip at the steel–concrete interface for welded CFST columns, so perfect adhesion is a reasonable assumption here. Future work could introduce cohesive surfaces to assess any interface slip effects. Specifically, the CDP parameters were set as follows: dilation angle = 30°, eccentricity = 0.10, σb0/σc0 ratio (Kc) = 2/3, and viscosity = 0.001, with default damage-evolution softening based on cracking energy [18]. These values are standard for concrete in ABAQUS. The steel material was defined as elastic–plastic with isotropic hardening: Young’s modulus (E) = 200 GPa, Poisson’s ratio (ν) = 0.3, yield strength (fy) = 235 MPa, and ultimate strength ≈ 360 MPa. The concrete core used the Concrete Damage Plasticity model: compressive behavior followed a stress–strain curve calibrated to the measured f′c, e.g., C40 had an f′c ≈ 40 MPa, with the elastic modulus (Ec) calculated from

[19]. Tensile behavior was modeled with a fracture energy approach. Default CDP parameters were used: dilation angle = ~30°, flow rule non-associative, viscosity = 0.001. Boundary conditions replicated the test: the column base was fixed in all degrees of freedom; the top was free except for the applied axial and lateral loads. Axial load was applied as a static gravity load (η ≈ 0.20), and lateral load was applied via displacement control matching the experimental protocol [20].

Figure 10 illustrates the 3D finite element modeling framework of RACFST columns, including the meshing strategy, material constitutive relationships, and boundary conditions used in ABAQUS.

Figure 10.

Three-dimensional finite element model of RACFST columns under cyclic loading.

Figure 10 illustrates the 3D finite element modeling framework of RACFST columns, including the meshing strategy, material constitutive relationships, and boundary conditions used in ABAQUS. The steel tube was modeled with eight-node shell elements (S8R), the concrete core with eight-node solid elements (C3D8R), and the CDP model was adopted for concrete behavior.

Axial load was applied as a static gravity load, and the column base was fully fixed to replicate experimental boundary conditions [21].

3.2. Model Parameters and Calibration

Material properties for concrete and steel were initially taken from the experiments and the literature [22]. To calibrate the model, parameters of the concrete stress–strain curve, such as the concrete ascending/descending branch and damage evolution, were fine-tuned so that the predicted backbone envelope matched the test for a chosen specimen, e.g., the 219 × 4–C40 column. The steel stress–strain curve was taken from Q235B coupon data (yield = 235 MPa, ultimate = 360 MPa, with 5% strain). Mesh convergence studies verified that element sizes of ~20 mm for concrete and ~10 mm for steel gave mesh-independent results. The tie constraint effectively assumed no slip at the steel–concrete interface, consistent with full filling [23]. The key parameters (peak stresses and stiffnesses) were iteratively adjusted so that the initial stiffness, yield point, and ultimate strength of the FE model closely matched the experimental curves within ~5% [24].

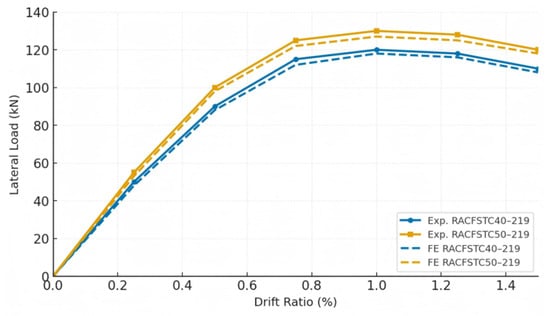

3.3. Model Validation

After calibration, the finite element (FE) model was validated against the experimental results of several RACFST column specimens. Figure 11 compares the experimental and simulated load–drift responses, including the backbone curves for the representative specimens RACFSTC40–219 and RACFSTC50–219. The numerical results show excellent agreement with the experimental data, with deviations in peak load, yield point, and post-peak softening within approximately 10%. The FE simulations successfully reproduced the characteristic pinching effect and stiffness degradation observed in the experiments, indicating that the model can accurately capture the cyclic behavior of RACFST columns. This good consistency between the experimental and numerical results provides strong confidence in the model’s reliability and applicability for subsequent parametric analyses and design-oriented studies. While this study primarily employs conventional finite element modeling calibrated to physical tests, recent computational trends have explored data-driven and hybrid methods. For example, DEM-driven investigation and AutoML-enhanced prediction techniques have demonstrated the ability to capture complex damage evolution and parameter interdependence in composite columns. Incorporating such approaches in future studies may enrich prediction accuracy and support real-time structural assessment.

Figure 11.

Comparison of experimental and finite element backbone curves for specimens RACFSTC40–219 and RACFSTC50–219.

3.4. Simulation Cases and Procedures

Using the validated model, a parametric study was conducted. A series of simulations were run to assess the influence of key factors: (1) section geometry: diameters 100–300 mm and wall thicknesses 3–8 mm (varying D/t); (2) axial load ratio: η from 0 (no axial load) to 0.4; (3) concrete strength: C30, C40, and C50; (4) material properties, e.g., using Q345 steel (fy ≈ 345 MPa) in place of Q235 to test the effect of stronger steel. Each simulation used the same cyclic displacement protocol as in the tests force-controlled to yield, then displacement-controlled increments with three cycles each until either F ≤ 0.85Fmax or drift ≥ 1/30. In total, dozens of cases were analyzed. The outputs hysteresis loops, envelope curves, ductility, damping, and degradation rates were recorded for each case to quantify trends. For example, some simulations explored the effect of varying only D/t by holding axial load and concrete strength fixed [25].

3.5. Analysis of Simulation Results

The numerical results confirmed and extended the experimental trends. Increasing D or thickness, i.e., lowering D/t, significantly increased both strength and ductility [26]. For example, doubling D while keeping t fixed raised Fmax by ~25% and increased ductility μ by ~50%. Conversely, increasing the axial load ratio (η) reduced ductility and resulted in earlier yielding and faster softening, though it also slightly increased initial strength. The higher-strength concrete, C50 vs. C30, increased peak load ~10–15% per strength level but reduced the yield drift and μ similarly to test observations. Using higher-grade steel (Q345) raised both yield and ultimate capacities but had a negligible effect on drift demands. The simulations also allowed evaluation of design code predictions: back-calculated strengths from EC4/GB specifications matched the FE results closely, confirming that standard CFST formulas apply to RACFST if f′c is reduced by a few percent. In terms of damping, the FE models reproduced the increase in ξeq with drift, corroborating the recommended values (Section 2.3). Overall, the numerical study provided a comprehensive dataset linking geometry and material parameters to key response quantities (strength, ductility, and degradation rates), which can inform design guidelines for RACFST columns.

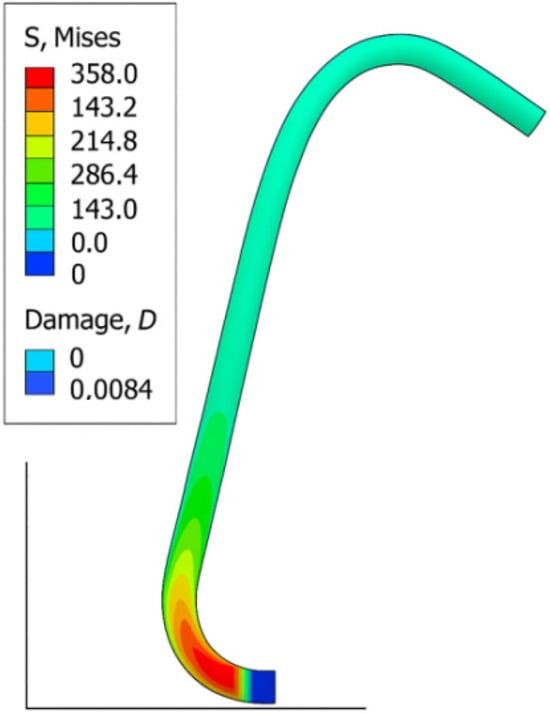

Figure 12 presents the von Mises stress and concrete damage contours at peak drift, highlighting the stress concentration zones and the formation of the plastic hinge near the column base.

Figure 12.

Von Mises stress and concrete damage distribution at peak drift for RACFST column.

Figure 12 shows the distribution of von Mises stress and concrete damage at the peak drift. The stress concentration near the column base indicates the formation of a plastic hinge zone, while the damage contour demonstrates the initial crushing of the concrete core. The FE model successfully reproduces the flexural-dominated behavior and stress transfer between steel and concrete.

4. Conclusions

In this paper, a combined experimental and numerical investigation was performed on circular CFST columns with 100% recycled concrete infill under low-cycle loading. The main findings are summarized as follows:

- RACFST columns failed in bending, with local outward bulging at the base, exhibiting full “spindle-shaped” hysteresis loops with no brittle shear failure.

- The peak bearing capacity of RACFST columns was comparable to that of conventional CFST of the same dimensions, while the RACFST specimens showed significantly higher displacement ductility and energy dissipation.

- Increasing the section diameter, reducing D/t, markedly improved ductility and delayed post-peak stiffness degradation, whereas higher concrete strength (C50) raised the peak load by roughly 10–15% per strength class but slightly reduced the yield displacement, thus causing only a marginal change in overall ductility.

- The equivalent viscous damping ratio (ξeq) increased monotonically with drift: at service-level drifts ≤ 1%, ξeq ≈ 0.04–0.08, and at larger drifts of ~2–3%, ξeq reached 0.10–0.18. These values support using stage-dependent damping ≈ 5–8% for service levels and ≈10–18% for strong-motion drifts in seismic design.

- The validated finite element model accurately captured the cyclic response. Parametric simulations indicate that existing CFST design codes can be applied to RACFST columns with only a modest ~3–5% reduction in the core concrete design strength to ensure post-peak stability. While this study demonstrates promising mechanical performance for 100% recycled aggregate CFST columns, future research should assess economic feasibility at scale. Large-scale adoption may face challenges related to consistent supply of high-quality recycled aggregates and potential cost variations due to processing and transportation. A lifecycle cost analysis and regional supply chain evaluation would help clarify the practical implementation potential of this sustainable construction approach.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L., R.C., and Y.M.; methodology, X.L., R.C., and Y.M.; formal analysis, X.L., R.C., and Y.M.; investigation, X.L., R.C., and Y.M.; resources, X.L. and R.C.; data curation, X.L. and R.C.; writing—original draft preparation, X.L. and R.C.; writing—review and editing, X.L. and R.C.; visualization, X.L. and R.C.; supervision, X.L. and R.C.; project administration, X.L. and R.C.; funding acquisition, X.L. and R.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 12072107); the Education Department of Henan Province: (No. 25A580009); Transportation Engineering (Henan Provincial Key Discipline), Huanghe Jiaotong University (No. 20238ZDXK318); and Young Talent of Lifting Engineering for Science and Technology in Shandong of China (SDAST2024QTA073).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank the members of the research group for their careful guidance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hua, B. Research on the Improvement of Seismic Toughness of Underground Station Structures Using Steel Tube Concrete Composite Columns. Civ. Eng. Manag. News 2025, 42, 18–29. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Zhao, X.-Y.; Wu, B.; Chen, G.-M. Cyclic behavior of recycled-lump-concrete-filled GFRP tubular columns: Experimental investigation and numerical modeling. Structures 2023, 53, 1489–1505. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Feng, D. Low-cycle reversed loading test study on circular concrete-filled steel tube columns. Water Transport Eng. 2019, 2019, 132–137+176. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Zhao, P.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Lu, Y. Experimental research on seismic performance of steel fiber-reinforced recycled concrete-filled circular steel tube columns. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 54, 104683. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Mo, L.; Xu, D. Seismic performance of concrete-filled steel tube column-reinforced concrete beam frame using 100% recycled coarse aggregate. Struct. Concr. 2024, 25, 5024–5036. [Google Scholar]

- Han, L.-H.; Hou, C.; Xu, C.-Y. Behaviour of recycled aggregate concrete-filled stainless steel tubular columns subjected to lateral monotonic and cyclic loading. Eng. Struct. 2023, 293, 116663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Wang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Geng, Y. Seismic behaviour of concrete-filled steel tubular columns with 100% recycled coarse and fine aggregates: Experiments and modeling. Eng. Struct. 2025, 344, 121294. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhao, H.; Wang, W.-D.; Chen, M.-T. Cyclic response of tapered recycled aggregate concrete-filled high-strength double-skin steel tube column. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2026, 236, 109948. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Wang, H.; Cheng, Y.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, L. Experimental and numerical investigation on strengthening mechanism of rib-reinforced round-over-round RCFDST column jointed with steel beam under cyclic loading. Thin-Walled Struct. 2023, 192, 111049. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Mohammed, A.; Chen, Z.; Huang, J. Research on Seismic Behavior of CFT-Frame-Buckling Restrained Steel Plate ShearWall Structures Using Recycled Aggregate Concrete. In Proceedings of the 17th East Asian-Pacific Conference on Structural Engineering and Construction (EASEC), Singapore, 27–30 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Meng, E.; Zhang, X.; Su, Y. Restoring force model of steel-recycled concrete composite frame with infilled recycled block wall. Struct. Des. Tall Spec. Build. 2022, 31, e1944. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Meng, E.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, S.; Su, Y. Study on Restoring Force Model of RACFST Frame Infilled with RHB Masonry Wall. Int. J. Steel Struct. 2022, 22, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Ma, H.; Xin, A.; Bai, H. Hysteretic behaviors and calculation model of steel reinforced recycled concrete filled circular steel tube columns. Struct. Eng. Mech. 2022, 83, 305–326. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R.; Ma, H.; Yang, L.; Du, B.; Liu, F. Numerical Analysis and Bearing Capacity Calculation of Steel-Reinforced Recycled Aggregate Concrete-Filled Square Steel Tube Columns Under Low Cyclic Loading. Struct. Des. Tall Spec. Build. 2025, 34, e70060. [Google Scholar]

- EN 1994-1-1; Eurocode 4—Design of Composite Steel and Concrete Structures—Part 1-1: General Rules and Rules for Buildings. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2004.

- GB 50936-2014; Technical Code for Concrete-Filled Steel Tubular Structures. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2014.

- Qiang, J.; Ma, H.; Xi, J.; Zhao, Y. Cyclic loading tests and horizontal bearing capacity of recycled concrete filled circular steel tube and profile steel composite columns. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2022, 199, 107572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ma, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Y. Seismic damage evaluation of steel reinforced recycled concrete filled circular steel tube composite columns. Earthq. Struct. 2022, 23, 445–462. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Ma, H.; Fang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Gan, X. Cyclic loading tests and seismic behaviors of steel-reinforced recycled aggregate concrete filled square steel tube composite columns. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2024, 212, 108270. [Google Scholar]

- Elzeadani, M.; Bompa, D.V.; Elghazouli, A.Y. Seismic Performance of Steel Tubes Infilled with Rubberised AAC Materials. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on the Behaviour of Steel Structures in Seismic Areas (STESSA), Salerno, Italy, 8–18 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Amer, M.; Du, Y.; Chen, Z.; Al-Haaj, M.; Huang, J. Seismic behaviors of CFT-column frame-four-corner bolted connected buckling-restrained steel plate shear walls using ALC/RAC panels. Thin-Walled Struct. 2024, 195, 111365. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhan, L. Seismic behaviors of tailings and recycled aggregate concrete-filled steel tube columns. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 365, 130115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Amer, M.; Du, Y.; Mashrah, W.A.H.; Zhang, W. Experimental and numerical investigations on cyclic performance of L-shaped-CFT column frame-buckling restrained and unrestrained steel plate shear walls with partial double-side/four corner connections. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 78, 107568. [Google Scholar]

- Amer, M.; Du, Y.S.; Chen, Z.H.; Laqsum, S.A.; Zhang, Y.T. Seismic behavior of concrete-filled steel tubes column frame-buckling restrained steel plate shear walls connected with bolt/weld. Thin-Walled Struct. 2023, 189, 110911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zong, S.; Ma, W.; Liu, Z.; Li, P. Research on eccentric-compressive behaviour of steel-fiber-reinforced recycled concrete-filled square steel tube short columns. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2023, 206, 107910. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, G.-Y.; Chen, S.-D.; Xu, L.; Zhang, P.-Q.; Liu, R.-Y. Flexural behavior of recycled brick aggregate geopolymer concrete-filled steel tube members. Structures 2025, 76, 108888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).