Abstract

FeCoNiCrAl and FeCoNiCrAlScY high-entropy coatings were fabricated via electron beam physical vapor deposition. The microstructure and short-term isothermal oxidation behavior of the coatings were compared. Sc and Y inhibited coating element diffusion to the superalloy substrate and formed co-precipitated phases during coating manufacturing. The Sc/Y co-doped coating exhibited accelerated phase transformation from θ- to α-Al2O3 as compared to the undoped one. The effect mechanism associated with the nucleation of α-Al2O3 was discussed. The preferential formation of Sc/Y-rich oxides promoted the nucleation of α-Al2O3 beneath them, and the θ-α phase evolution process was directly skipped, which suppressed the rapid growth of θ-Al2O3 and the initial formation of cracks in the alumina film and provided the FeCoNiCrAl high-entropy coating with an improved oxidation property in the early oxidation stage.

1. Introduction

A thermal power station equipped with heavy-duty gas turbines is an important component of the energy configuration systematic project. To match the development of efficient thermal power technology, the turbine inlet temperature of advanced J-class gas turbines has been elevated to over 1873 K [1,2]. Despite the adoption of advanced film-cooling technology, the surface temperature of key hot-section components still reaches 1473 K [3,4]. To realize high-temperature service, a thermal barrier coating (TBC) is utilized, which enables the underlying substrate to operate at temperatures higher than its melting point [5,6,7,8]. A classic TBC comprises a thermal insulating topcoat and an oxidation-resistant bond coat. In the last several decades, NiAl, as a potential bond coat material, has attracted special attention on account of its ability to generate a dense alumina scale above 1473 K [9,10]. However, sustained thickening of the scale and repeated changes in operation temperature cause rapid stress accumulation and premature scale spallation [11,12], which severely limits the service life of the NiAl bond coat. Adding a trace of reactive elements (REs) in the NiAl alloy can simultaneously reduce the growth rate of the alumina scale and enhance its interfacial adhesion [12,13,14,15,16], but this improvement effect produced by RE single-doping is limited by the doping amount [16,17,18]. Recently, the co-doping of Sc and Y was found to further decrease the alumina growth rate by more than 20% [19]. This co-doping strategy may optimize the oxidation performance of the alloy and allow the total concentration of REs to be minimized, thus reducing their adverse effect.

Plasma spraying (PS) and electron beam physical vapor deposition (EB-PVD) are two dominant techniques for TBC production [20,21]. EB-PVD coatings with a columnar crystal structure have a higher strain tolerance and thermal cycle life than PS coatings [22,23], which represents the development direction of high-performance TBC coating technology. However, the formation of columnar grain boundaries provides short-circuit diffusion channels and accelerates coating oxidation [16,24,25]. The disordered arrangement of atoms in high-entropy alloys with multi-principal elements leads to a hysteresis effect that helps to decrease the diffusion rate of alloy elements [26,27,28], and combining NiAl alloy and other alumina-forming alloys to increase the number of principal elements and achieve high-entropy transformation offers a new strategy to solve the rapid oxidation problem of EB-PVD coatings. Butler et al. found that a dense alumina scale formed on FeCoNiCrAl high-entropy alloy when the Al content was higher than 15 at.% [29]. An exciting study by Zhao et al. suggested that an effective reduction in the oxidation rate was achieved by combinations of Hf and Y in FeCoNiCrAl high-entropy alloy, and the oxidation rate constant was only 1.4 × 10−12 g2cm−4s−1 at 1473 K [30]. The entire oxidation process usually includes an initial oxidation stage and a steady oxidation stage. During the first oxidation stage, metastable θ-Al2O3 is formed on the alloy and then evolves into stable α-Al2O3 [31]. Previous studies indicated that REs, including Hf, Zr, Y, La, and Ce, retarded the θ-α phase transformation, whereas Ti accelerated the transformation [32,33]. Since monoclinic θ-Al2O3 has an evidently higher growth rate than hexagonal α-Al2O3 [34,35,36], delaying the transformation should be detrimental to the reduction in the alumina scale growth rate. In addition, the evolution of the phase structure is accompanied by 13.4% volume shrinkage [37,38], and promoting the transformation might induce crack formation in the alumina scale, which could also compromise the protection of the underlying substrate. However, these phenomena are not consistent with the actual oxidation performance of the alloy under the effect of RE-doping. The existence of the above puzzling contradiction reflects that the effect mechanism of REs on initial oxidation is not yet clarified.

In the current work, microstructure observation and short-term isothermal oxidation tests were performed. Additionally, a comparative study was conducted to explore the roles of Sc and Y in influencing the initial growth behavior of alumina on an FeCoNiCrAl high-entropy coating prepared by EB-PVD and to establish a fundamental understanding of the co-doping effect of two REs on the oxidation performance of alumina-forming high-entropy coatings.

2. Experimental Methods

A second-generation nickel-based single-crystal superalloy with the chemical composition of Ni-9Co-4.5Cr-6Al-8W-1.5Mo-0.6Ta-1.5Ti-0.4Fe (minor C, in wt. %) was utilized as a substrate material. Circular specimens (φ15 mm × 3 mm) for coating deposition were machined by spark erosion and ground to an 800-grit SiC finish. Then, the specimens were ultrasonically cleaned in acetone for 20 min and high-purity water for 10 min. Ingots of Fe-20Co-20Ni-20Cr-20Al and Fe-20Co-20Ni-20Cr-19.9Al-0.05Sc-0.05Y (all in at.%) for coating evaporation were produced by vacuum arc-melting.

An EB-PVD facility equipped with three EB guns and three crucibles was utilized for fabricating the high-entropy coatings. Two EB guns were employed during coating preparation, one of which was used for heating and evaporating the ingots and the other for heating the substrate specimens. FeCoNiCrAl and FeCoNiCrAlScY high-entropy coatings were manufactured using the same processing parameters. The EB current for evaporating the ingots was maintained at 1.30 A, and that for heating the substrate specimens was maintained at 0.2 A; the substrate temperature was ~1073 K, determined by thermocouples fastened to the specimen holder. During deposition, the deposition rate of the coatings was kept at 1.5 μm/min, the rotation rate of the holder was kept at 13 r/min, and the vacuum degree of the evaporation chamber was kept at 10−4 Pa. All the specimen surfaces, including the side surfaces, were covered with the coatings, and both of the coatings were deposited with the same thickness of ~50 μm. The as-deposited specimens were then heat-treated at 1323 K for 2 h with a chamber pressure level of 10−4 Pa. The actual chemical compositions of the as-annealed coatings are listed in Table 1. The contents of coating elements are basically consistent with those designed.

Table 1.

Actual chemical compositions of the as-annealed FeCoNiCrAl and FeCoNiCrAlScY high-entropy coatings determined by inductively coupled plasma analysis (in at.%).

Short-term isothermal oxidation tests at 1473 K were carried out in a tube-type air furnace equipped with an automation system that enabled the specimens to be moved in and out of the chamber automatically. Each specimen was hung in a pre-annealed alumina crucible to avoid direct contact with the furnace walls. After the required oxidation time, the specimens were taken out of the chamber and cooled in air for oxide-phase identification and morphology observation.

The surface and cross-sectional morphologies of the as-annealed coatings and the oxide films were obtained by a field emission-scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM, Quanta 650, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Brno, Czech) equipped with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectrum (EDXS). For cross-sectional observation, the specimens were embedded in epoxy and finely polished. The phases of the oxide films were determined by luminescence spectra stimulated by a probing argon-ion laser (RM2000, Renishaw, Woodchester, UK), in accordance with a report stating that the spectral peaks of θ-Al2O3 occurred at frequencies of 14,575 and 14,645 cm−1 and that those of α-Al2O3 occurred at frequencies of 14,402 and 14,432 cm−1 [39]. Bright-field (BF) images, high-angle annular dark field (HAADF) images, selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns, element mappings, and high-resolution images of the as-annealed coatings and the film/coating interface were acquired by a field-emission–transmission electron microscope (FE-TEM, JEM-F200, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) at 200 kV. The specimens used for TEM observation were prepared using a focused ion beam cutting device.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Coating Microstructure Characterization

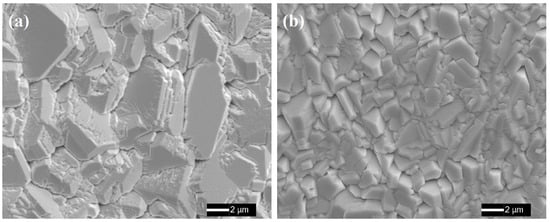

Figure 1 shows the surface morphologies of the as-annealed FeCoNiCrAl and FeCoNiCrAlScY high-entropy coatings. Both of the coatings exhibit a classic domain structure. The undoped coating displays coarse grains with an average size of (4.7 ± 1.0) μm, while finer grains are achieved in the co-doped coating, of which the average grain size is (1.9 ± 0.5) μm. This indicates that Sc and Y co-doping leads to grain refinement. Due to the low solid solubility in the coating lattice, excessive REs preferred to precipitate, thereby forming intermetallics accompanied by coating elements. These phases prevented grain boundary migration, which is regarded as a “solute drag effect” [40], thus hindering grain growth and causing grain refinement during coating preparation. Previous work by Pint et al. suggested that finer grains promoted protective alumina scale formation by enhancing the diffusion rate of Al because smaller grains provided more short-circuit diffusion channels [41].

Figure 1.

SEM plane-view images of the as-annealed high-entropy coatings: (a) FeCoNiCrAl (×5000), (b) FeCoNiCrAlScY (×5000).

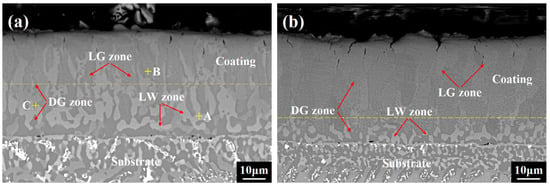

Figure 2 shows the corresponding cross-sectional morphologies of the as-annealed coatings. Three zones with distinct contrasts are observed in the undoped coating, namely, a light white (LW) zone, light gray (LG) zone, and dark gray (DG) zone. The EDXS results given in Table 2 demonstrate that the first two zones are rich in Fe and Cr, and the DG zone contains more Ni and Al. Note that all the LW zones with slightly lower contents of Fe and Cr than the LG zones are primarily distributed near the coating/superalloy interface. This is because the Fe and Cr in the coating inevitably diffused to the superalloy substrate, driven by the concentration gradient, and element loss consequently occurred in the LW zones; additionally, the interdiffusion depth in the coating developed to (23.2 ± 2.7) μm after coating fabrication (marked by a yellow dashed line in Figure 2a). For the co-doped coating, the interdiffusion depth is only (11.1 ± 1.9) μm, and the coating mainly comprises LG and DG zones (marked by a yellow dashed line in Figure 2b), revealing that the existence of Sc and Y impeded the inward diffusion of Fe and Cr in the coating, thereby guaranteeing the stability of coating phases and avoiding probable performance degradation. In addition, these zones in the undoped coating exhibit a strip-like or bulk-like morphology. While in the co-doped coating, the sizes of the DG zones decrease, but their quantity increases. Therefore, it seems that high-density NiAl-rich particles are dispersed in the FeCr-rich substrate.

Figure 2.

SEM cross-sectional images of the as-annealed high-entropy coatings: (a) FeCoNiCrAl (×2000), (b) FeCoNiCrAlScY (×2000).

Table 2.

Chemical compositions of the corresponding zones in Figure 2a determined by EDXS (in at.%).

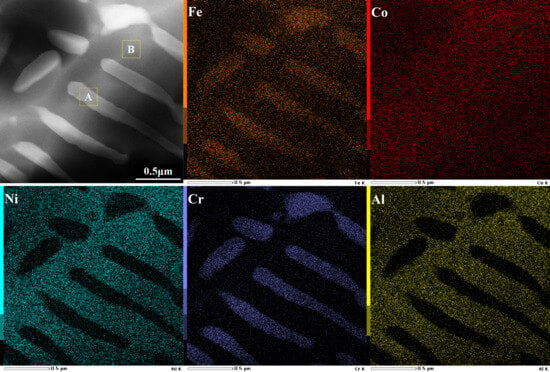

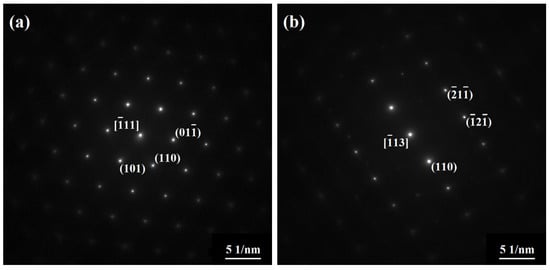

Figure 3 shows an HAADF image and corresponding element mappings of two classic phases in the as-annealed FeCoNiCrAl high-entropy coating. It is clear that these phases display an alternating interpenetration characteristic. The light phase primarily consists of Fe and Cr, and the dark one is enriched in Ni and Al, which is consistent with the EDXS results from the LG and DG zones in Figure 2a. Figure 4 shows the SAED patterns of the corresponding phases. The light phase is oriented with a beam direction along [-111], and the dark one is oriented with a beam direction along [-113]. The results indicate that both phases have a BCC structure. According to previous reports, the light phase is identified as an FeCr intermetallic phase with an A2 structure, and the dark one is believed to be a NiAl intermetallic phase with a B2 structure [30].

Figure 3.

TEM high-angle annular dark field image (×100,000) and element mappings of the as-annealed FeCoNiCrAl high-entropy coating.

Figure 4.

Electron diffraction patterns of the corresponding zones in Figure 3: (a) Zone A, (b) Zone B.

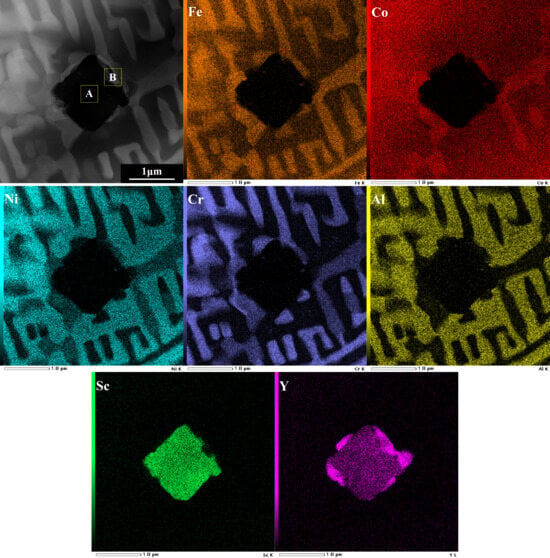

Figure 5 shows an HAADF image of a classic precipitate in the as-annealed FeCoNiCrAlScY high-entropy coating. The square-like precipitate is distributed along the grain boundaries and surrounded by some light zones. The EDXS results indicate that the precipitate contains both Sc and Y (as shown in Table 3). The corresponding element mappings of the precipitate are also shown to enable further analysis of its chemical composition. Sc and Y simultaneously precipitated from the coating to form two kinds of phases. The one located at the center is high in Sc content, and the others surrounding it have a relatively larger amount of Y. It is suggested that the co-precipitation of REs should be associated with their chemical nature. Because of the low solid solubilities of Sc and Y in the FeCr and NiAl lattices [42], excessive Sc and Y atoms tend to precipitate, forming intermetallics along with coating elements during coating manufacturing. Since Sc and Y have the same outermost electron arrangement and steady-state valence, as both of them are Group IIIB elements, their atoms were substituted mutually during precipitation. From another point of view, Sc and Y atoms combined with each other and formed an entire atomic cluster. Therefore, it is proposed that Sc and Y first co-segregated at their preferential sites and then formed co-precipitated phases. In reality, the co-precipitation of RE atoms has already been observed in alumina-forming alloys such as NiAl and FeAl [17,19]. This atomic cluster has a larger action radius than the two individual Sc and Y atoms, which could have a more profound impact on the initial oxidation of the coating.

Figure 5.

TEM high-angle annular dark field image (×50,000) and element mappings of the as-annealed FeCoNiCrAlScY high-entropy coating.

Table 3.

Chemical compositions of the corresponding zones in Figure 5 determined by EDXS (in at.%).

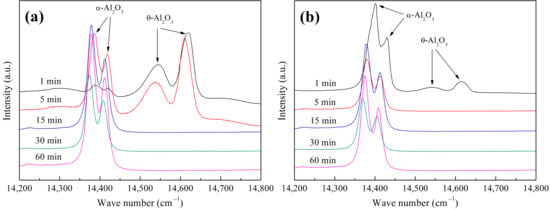

3.2. Oxide Phase Identification

After short-term isothermal oxidation testing, the crystal forms of the oxide films grown on the FeCoNiCrAl and FeCoNiCrAlScY high-entropy coatings were carefully identified. Figure 6 shows the luminescence spectra excited from the oxide films after the required oxidation times. Metastable θ-Al2O3 and stable α-Al2O3 peaks were simultaneously detected on both of the coating surfaces after 1 min of exposure, indicating that the phase transformation from θ-to α-Al2O3 was in progress. In comparison with this, Sc and Y co-doping substantially promoted the transformation, as the volume fraction of θ-Al2O3 on the Sc/Y co-doped coating was lower than that on the undoped one, as deduced from the lower peak intensity ratio of θ-and α-Al2O3. The peaks of metastable θ-Al2O3 completely disappeared on the undoped coating surface when the exposure time reached 15 min. For the co-doped coating, α-Al2O3 peaks were the unique fluctuation on the curve just after 5 min of oxidation, implying that transformation occurred within 5 min. To intuitively compare the progress of the θ-α phase transformation in these alumina films, the area enclosed by the characteristic peak curve and the baseline in Figure 6 was computed, and the proportion of the θ-Al2O3 peak area in the gross area of the θ-Al2O3 and α-Al2O3 peaks at each oxidation time point was determined (as shown in Table 4). Since the luminescence spectral peak area could reflect the amount of the corresponding phase, the variation tendency of the amount of the θ-Al2O3 phase in the alumina film with an increased oxidation time was also obtained. Based on the luminescence spectrum and peak area ratio results, it could be deduced that the combined addition of Sc and Y had a significant effect on accelerating the θ-α phase transformation.

Figure 6.

Luminescence spectra excited from the oxide films on the high-entropy coatings after short-term isothermal oxidation at 1473 K: (a) FeCoNiCrAl, (b) FeCoNiCrAlScY.

Table 4.

Proportions of θ-Al2O3 peak area in gross area of θ-Al2O3 and α-Al2O3 peaks under different oxidation times acquired from Figure 6 (in %).

A classic theory put forward by Burtin et al. highlights that the proliferation of anion vacancies is required to promote the evolution of θ-Al2O3, which is realized by a dehydroxylation mechanism, as the metastable Al2O3 lattice usually contains water in the form of hydroxyl species [43]. These anion vacancies annihilate with cation vacancies, which are intrinsic defects in the metastable Al2O3 lattice and eventually lead to the destruction of the original lattice and the reconstitution of a new lattice. During the initial oxidation, the Sc and Y cations incorporated into the open lattice of growing θ-Al2O3 either replaced Al cations or occupied vacancy sites [43,44]. Since Sc and Y cations have the same valence as Al cations (+3), the quantity of anion vacancies was not influenced by the replacement of Al cations, as O atoms did not adopt excessive electrons. In contrast to this, occupying vacancy sites directly induced a decrease in the quantity of anion vacancies based on the charge compensation principle, thus retarding the transformation by disrupting the triggering condition. Additionally, Sc and Y cations with a larger size than Al cations entering the θ-Al2O3 lattice resulted in distortion of the surrounding lattice, thereby further delaying the transformation by overcoming the higher energy barrier [43]. Here, a puzzling contradiction is presented by the theoretical analysis and experimental results. On the one hand, Sc and Y with a larger size than Al should effectively decelerate the θ-α phase evolution process through mechanisms similar to those of other REs including Hf, Zr, La, and Ce did supported by Burtin’s theory. On the other hand, the addition of Sc and Y obviously accelerated the θ-α phase transformation, as indicated by the luminescence spectral curves. These conflicting results suggest that an intrinsic factor affecting the evolution process must be involved.

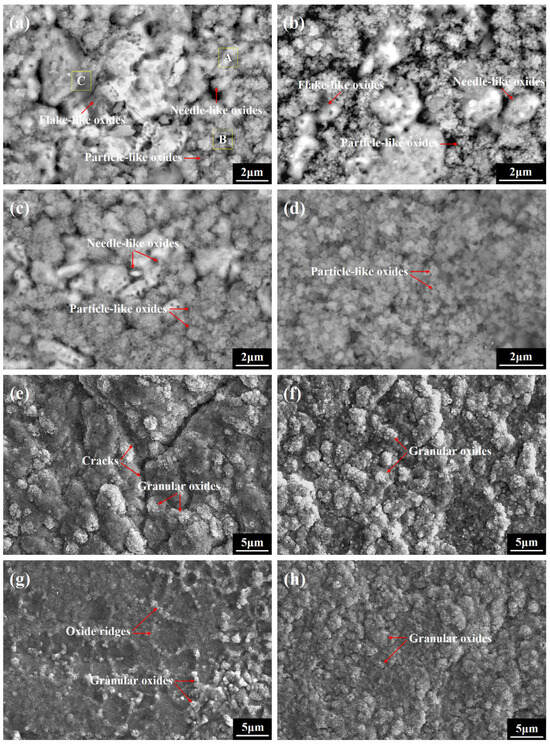

3.3. Oxide Morphology Observation

To further ascertain the initial growth process of alumina and investigate the difference in phase evolution between the FeCoNiCrAl and FeCoNiCrAlScY high-entropy coatings, classic surface morphologies of the oxide films after the required oxidation times were thoroughly inspected, and the results are shown in Figure 7. After 1 min of oxidation, only partial zones of the coating surfaces are covered with discrete oxides, indicating that continuous oxide films had not been yet formed at this time. For the undoped coating, the spires of coating grains are decorated with needle- and particle-like oxides, and several flake-like oxides are scattered adjacent to them. The EDXS results given in Table 5 indicate that these needle- and particle-like oxides are Al2O3, and the flake-like ones should be spinel oxides. The needle-like oxides are linked to θ-Al2O3, and the particle-like oxides are believed to be α-Al2O3, as described elsewhere [33,45,46]. The coexistence of θ- and α-Al2O3 indicates an ongoing transformation in the initial oxidation stage. For the co-doped coating, the particle-like oxides occupy most of the coating surface, and only a few needle-like oxides are observed on the spires of the coating grains. When the exposure time is 5 min, most zones of the undoped and co-doped coating surfaces are covered by numerous particle-like oxides, and the only distinction is that several visible needle-like oxides are also interspersed among the particle-like oxide clusters on the undoped coating surface. The obvious difference in the quantity of θ- and α-Al2O3 between these coatings suggests that an accelerated θ-α phase transformation substantially occurred on the co-doped coating surface.

Figure 7.

SEM plane-view images of the oxide films on the high-entropy coatings after short-term isothermal oxidation at 1473 K: (a) FeCoNiCrAl after 1 min (×8000), (b) FeCoNiCrAlScY after 1 min (×10,000), (c) FeCoNiCrAl after 5 min (×8000), (d) FeCoNiCrAlScY after 5 min (×10,000), (e) FeCoNiCrAl after 15 min (×3000), (f) FeCoNiCrAlScY after 15 min (×3000), (g) FeCoNiCrAl after 60 min (×3000), (h) FeCoNiCrAlScY after 60 min (×3000).

Table 5.

Chemical compositions of the corresponding zones in Figure 7a determined by EDXS (in at.%).

When the oxidation time was prolonged to 15 min, both of the coating surfaces were fully covered with granular oxides, and virtually no needle-like oxides were detected, revealing that θ-Al2O3 completely evolved into α-Al2O3. Apart from this, three cracks were formed in the oxide film on the undoped coating surface, and they intersected at one point and divided the entire film into several separate zones. It is accepted that the rapid θ-α phase transformation caused large tensile stress and crack formation in the film, originating from rapid volume shrinkage [39]. These cracks provided short-circuit diffusion channels for oxygen and triggered the rapid growth of new oxides on the cracking surface, which is detrimental to the oxidation resistance of the coating. In contrast to this, no cracks formed in the oxide film on the co-doped coating surface, even though its θ-α phase transformation rate was higher than that of the undoped one.

When the exposure time reached 60 min, several film ridges were found on the undoped coating surface, which is a classic morphology of α-Al2O3 on alumina-forming alloys. These film ridges can be divided into “intrinsic” ridges and “extrinsic” ridges. The former grew along the alumina grain boundaries, and the latter generated closely related to the θ-α phase transformation [47]. Upon detailed examination, it was found that the size of the raised ridges was visibly larger than the alumina grain size. On the basis of the present work, these coarse ridges were believed to grow in zones where the film cracked as a result of volume shrinkage during the θ-α phase transformation and were identified as “extrinsic” ridges. In contrast to this, the oxide film on the co-doped coating surface only showed a granular structure, which was attributed to the segregation of Sc and Y on the alumina grain boundaries [48]. During high-temperature oxidation, Sc and Y ions slowly migrated to the film/gas interface along the alumina grain boundaries under the oxygen potential gradient and blocked the rapid transport of Al ions, which diffused along the same channels to accomplish the oxidation reaction, and the inward migration of oxygen governed the alumina film growth [49]. Under this mechanism, the alumina film developed a granular structure. However, since the alumina film, except for the ridge zones on the undoped coating surface, also exhibited an apparent granular structure, this structure formation could not be credited solely to the addition of Sc and Y and should be more related to the intrinsic diffusion hysteresis effect produced by the disorderly arranged multi-principal element atoms in the high-entropy coatings. Based on this effect, the outward migration of Al ions was decelerated, which changed the growth mechanism of the alumina film from the reverse transport of Al and oxygen to the dominant inward transport of oxygen; hence, a granular structure was also achieved.

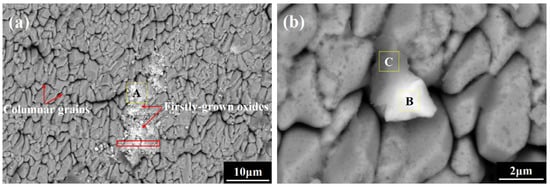

3.4. Intrinsic Factor Affecting the “Accelerating Effect”

To clarify the intrinsic factor affecting the “accelerating effect”, the process where Sc and Y ions enter the θ-Al2O3 lattice is brought into consideration. The above conflicting results have a precondition, namely, the incorporation of Sc and Y ions into the lattice of growing θ-Al2O3. Actually, because of the intrinsic diffusion hysteresis effect caused by multiple principal elements in the high-entropy coatings, Sc and Y ions migrated more slowly and did not have enough time to squeeze into the constructing lattice, as θ-Al2O3 had a rapid growth rate. Under this condition, the exploration of the intrinsic factor affecting the “accelerating effect” should begin by confirming the existing form of Sc and Y in the initial oxidation stage. Figure 8 shows the surface morphologies of a classic oxide growth zone on the co-doped coating surface after only 0.5 min of exposure. Some loose oxides are sparsely distributed on the coating surface, and they display a similar granular structure to α-Al2O3. The EDXS results listed in Table 6 suggest that this preferentially oxidized zone mainly comprises Sc/Y-rich oxides. In addition, it is surprising that one Sc/Y-rich oxide directly grew together with alumina to form a whole. Since Sc and Y possessed a higher oxygen affinity than Al and did not have sufficient time to enter the growing θ-Al2O3 lattice, they firstly oxidized to form Sc/Y-rich oxides on the coating surface instead of occupying vacancy sites and distorting the lattice during the initial oxidation, and then these first-grown oxides acted as heterogeneous nuclei to promote the Al surrounding them to form alumina.

Figure 8.

SEM plane-view images of the oxide film on the FeCoNiCrAlScY high-entropy coating after 0.5 min isothermal oxidation at 1473 K: (a) low magnification (×2000), (b) high magnification (×10,000).

Table 6.

Chemical compositions of the corresponding zones in Figure 8 determined by EDXS (in at.%).

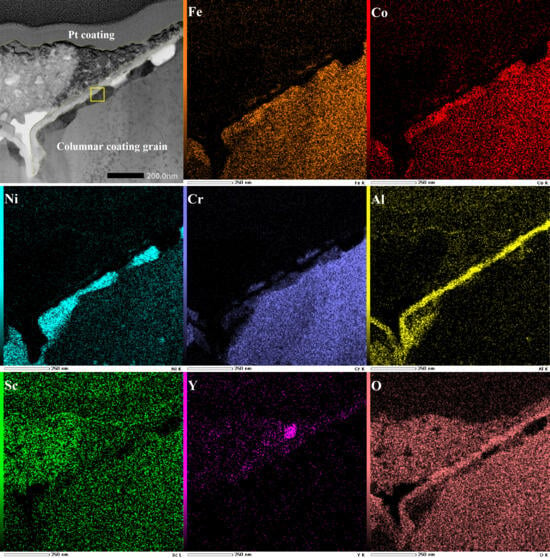

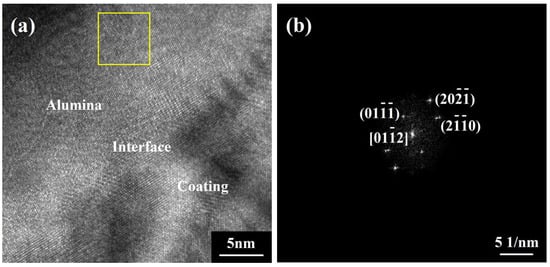

To further examine the initial growth process of alumina under the influence of Sc/Y-rich oxides, the preferentially oxidized zone (marked by a red box) was sliced along the direction perpendicular to the coating surface by a focused ion beam to expose the film/coating interface. Figure 9 shows the structure details and element information of the corresponding film/coating interface. A double-layer structure consisting of loose oxide particles and a dense oxide film beneath them is formed on the coating surface. The element mapping results show that the loose particles of the outer layer are Sc/Y-rich oxides and that the dense film of the inner layer is composed of alumina. Figure 10 shows a high-resolution image and fast Fourier transform diffraction pattern of the corresponding zone in Figure 9 (marked by a yellow box). The alumina film beneath the Sc/Y-rich oxide layer exhibits a clear HCP structure and is identified as α-Al2O3. From the above results, it can be deduced that, in the initial oxidation stage, Sc and Y preferentially oxidized on the coating surface to form Sc/Y-rich oxides, and, subsequently, Al began to directly oxidize to α-Al2O3 beneath the Sc/Y-rich oxides. In other words, the Sc/Y-rich oxides, as nucleation substrates, promoted the growth of α-Al2O3. Hence, the θ-α phase transformation was accelerated without crack initiation and ridge formation because the evolution process was directly skipped.

Figure 9.

TEM bright-field image (×200,000) and element mappings of the film/coating interface in the corresponding zone in Figure 8a.

Figure 10.

TEM high-resolution image (×1,500,000) (a) and fast Fourier transform diffraction pattern (b) of the corresponding zone in Figure 9.

Previous studies proposed that RE-rich oxides such as Y2O3 had a specific crystallographic orientation relationship with α-Al2O3. The (111) plane of Y2O3 and the (0001) plane of α-Al2O3 formed a low-mismatched structural interface, and α-Al2O3 could epitaxially grow on the (111) plane of Y2O3. However, since Sc/Y-rich oxides, including Sc2O3 and Y2O3, display a BCC structure while α-Al2O3 exhibits an HCP structure, the structure-mismatch condition still exists, and the direct growth of α-Al2O3 on the Sc/Y-rich oxide surface still needs to overcome the high energy barrier to meet the requirement of increased interface energy [50,51,52]. In combination with the growth location of α-Al2O3, which is beneath the Sc/Y-rich oxides instead of adjacent to them, the promotion of α-Al2O3 nucleation by Sc/Y-rich oxides could be explained as follows: The Sc/Y-rich oxides preferentially growing on the coating surface had a high concentration of oxygen vacancies and rapid diffusivity for oxygen due to the vacancy diffusion mechanism, which provided rapid diffusion channels for oxygen penetration [53,54]. Since the formation of α-Al2O3 depended on an inward growth mechanism [55,56], the existence of an outer Sc/Y-rich oxide layer and the inward diffusion of oxygen provided the essential environmental conditions for Al distributed in the surface layer of the coating to react with the penetrated oxygen and form an inner α-Al2O3 layer. Additionally, it should be noted that the refined grains of the co-doped coating further accelerated the nucleation of α-Al2O3, as its growth is mainly driven by grain boundary diffusion [41]. The stimulation of α-Al2O3 nucleation by Sc/Y-rich oxides is expected to have a positive impact on the oxidation resistance of the FeCoNiCrAl high-entropy coating during the early, and even subsequent, oxidation process. With the direct growth of α-Al2O3 and the decreasing fraction of θ-Al2O3 on the coating surface in the initial oxidation stage, the contribution of θ-Al2O3 growth to the fast oxidation of the coating is reduced, the probability of crack formation in the film due to drastic volume shrinkage is eliminated, the integrity of the alumina film is maintained, and, consequently, the oxidation property of the coating is moderately improved.

4. Conclusions

The microstructure and short-term isothermal oxidation behavior of undoped and Sc/Y co-doped FeCoNiCrAl high-entropy coatings produced by EB-PVD were investigated at 1473 K. Conclusions can be drawn as follows:

- During coating preparation, Sc and Y refined the coating grains and stabilized the coating phases owing to the obstruction of grain growth and element diffusion to the superalloy substrate, and they eventually formed co-precipitated phases, as Sc and Y are congeners and have the same outermost electron arrangement and steady-state valence, which allowed them to combine with each other.

- In the initial oxidation stage, the θ- to α-Al2O3 phase transformation was rapidly achieved on the undoped coating, while the evolution process was further accelerated on the co-doped coating with no crack initiation or ridge formation. The preferential formation of Sc/Y-rich oxides provided rapid diffusion channels for oxygen inward penetration, and the refined coating grains provided more grain boundaries for Al outward migration, thus promoting the nucleation of α-Al2O3 beneath the Sc/Y-rich oxides and visually expediting the θ-α phase transformation, as the evolution process was directly skipped.

- The direct formation of α-Al2O3 on the co-doped coating surface stimulated by the preferentially grown Sc/Y-rich oxides decreased the growth fraction of θ-Al2O3 and eliminated the initial formation of cracks originating from the θ-α phase transformation, hence reducing the contribution of θ-Al2O3 growth to the rapid oxidation of the coating and maintaining the integrity of the alumina film, which could improve the oxidation resistance of the FeCoNiCrAl high-entropy coating during the early oxidation process.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.L.; Data curation, D.L.; Formal analysis, S.Z.; Investigation, J.G.; Methodology, J.G.; Resources, J.S.; Validation, J.S.; Writing—original draft, D.L.; Writing—review and editing, S.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by Beijing Natural Science Foundation (2232070).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Dongqing Li, Shuhui Zheng, Jian Gu and Jiajun Si were employed by the company State Grid Electric Power Engineering Research Institute Co., Ltd.

References

- Pi, Y.H.; Park, J.S. Effect of the thermal barrier coating set up and modeling in numerical analysis for prediction gas turbine blade temperature and film cooling effectiveness. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2025, 164, 108860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Choi, M.; Choi, G. Thermodynamic performance study of large-scale industrial gas turbine with methane/ammonia/hydrogen blended fuels. Energy 2023, 282, 128731. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Qin, Z.; Luo, J.; Bai, M.; Liu, J.; Yu, D. Research on active modulation of gas turbine cooling air flow. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 230 Pt B, 120874. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Peng, X.; Lü, W.; Yang, S.; Li, H.; Guo, H.; Wang, J. Ultra-high temperature oxidation resistant refractory high entropy alloys fabricated by laser melting deposition: Al concentration regulation and oxidation mechanism. Corros. Sci. 2023, 224, 111537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, W.; Wang, J.; Li, K.; Li, H.; Liu, P.; Yang, S.; Zhang, C. Micro-nano dual-scale coatings prepared by suspension precursor plasma spraying for resisting molten silicate deposit. Coatings 2024, 14, 1123. [Google Scholar]

- Gudivada, G.; Pandey, A.K. Recent developments in nickel-based superalloys for gas turbine applications: Review. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 963, 171128. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.Q.; Liu, Z.Y.; Zhu, W.; Peng, X.M. Reliability assessment and lifetime prediction of TBCs on gas turbine blades considering thermal mismatch and interfacial oxidation. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 423, 127572. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Yang, G. Understanding of degradation-resistant behavior of nanostructured thermal barrier coatings with bimodal structure. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2019, 35, 231–238. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, F.; Wei, X.; Cao, J.; Ma, Y.; Su, H.; Zhao, T.; You, J.; Lv, Y. Thermal corrosion properties of composite ceramic coating prepared by multi-arc ion plating. Coatings 2024, 14, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.F.; He, L.M.; Guo, Y.; Shan, X.; Li, J.H.; Guo, F.W.; Zhao, X.F.; Ni, N.; Xiao, P. Effects of reactive element oxides on the isothermal oxidation of β-NiAl coatings fabricated by spark plasma sintering. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 357, 322–331. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, G.H.; Li, S.S.; Wang, Y.N.; Gui, P.P.; Zhang, M.Y.; Guo, K.Y.; Liu, M.J.; Yang, G.J. Unraveling β-NiAldegradation in aluminide coatings: A comparative study of isothermal oxidation and vacuum heat treatment. Corros. Sci. 2025, 251, 112946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.Z.; He, J.; Chen, H.; Zhou, B.Y.; Liu, L.; Guo, H.B. Theformation mechanisms of HfO2 located in different positions of oxide scales on Ni-Al alloys. Corros. Sci. 2020, 167, 108481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Li, W.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, S.; Gong, J.; Sun, C. The effect of Re and Hf interaction on the oxidation performance in ReHf co-doped NiAl coating. Corros. Sci. 2024, 240, 112447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; He, J.; Liu, L.; Wang, S.; Sun, J.; Wei, L.; Guo, H. The interaction between Dy, Pt and Mo during the short-time oxidation of (γ’ plus β) two-phase Ni-Al coating on single crystal superalloy with high Mo content. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2022, 430, 127999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.; Weaver, M. Microstructural investigation of the thermally grown oxide on grain-refined overdoped NiAl-Zr. Oxid. Met. 2019, 92, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.Q.; Guo, H.B.; Wang, D.; Zhang, T.; Gong, S.K.; Xu, H.B. Cyclic oxidation ofβ-NiAl with various reactive element dopants at 1200 °C. Corros. Sci. 2013, 66, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xu, M.M.; Zhang, C.Y.; Niu, Y.S.; Bao, Z.B.; Zhu, S.L.; Wang, F.H. Co-doping effect of Hf and Y on improving cyclic oxidation behavior of (Ni,Pt)Al coating at 1150 °C. Corros. Sci. 2021, 178, 109093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adharapurapu, R.R.; Zhu, J.; Dheeradhada, V.S.; Lipkin, D.M.; Pollock, T.M. Effective Hf-Pd Co-doped β-NiAl(Cr) coatings for single-crystal superalloys. Acta Mater. 2014, 76, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.Q.; Zhou, L.X.; Zhu, K.J.; Gu, J.; Zheng, S.H. Isothermal oxidation behavior of scandium and yttrium co-doped B2-type iron-aluminum intermetallics at elevated temperature. Rare Met. 2018, 37, 690–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, C.R.; Crespo, V.; Nin, J.; Clavé, G.; Dosta, S. Adhesion of thermal barrier coatings: Influence of the bond coat application technique. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 503, 132031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, W.; Li, Q.; Feng, W.; Yang, L.; Zhou, Y. Performance and failure modes of thermal barrier coatings deposited by EB-PVD on blades under real service conditions in gas turbine. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1008, 176889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xiong, K.; Li, D.; Hou, C.; Fan, X. A thermal mechanical coupled damage accumulation model for rare earth-doped EB-PVD TBCs under isothermal oxidation, cyclic oxidation and creep conditions. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 505, 132088. [Google Scholar]

- Ozgurluk, Y.; Doleker, K.M.; Karaoglanli, A.C. Hot corrosion behavior of YSZ, Gd2Zr2O7 and YSZ/Gd2Zr2O7 thermal barrier coatings exposed to molten sulfate and vanadate salt. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 438, 96–113. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.S.; Wang, Y.Q.; Chen, M.H.; Yang, L.L.; Wang, J.L.; Zhu, S.L.; Wang, F.H. Oxidation behavior of Al/Y co-modified nanocrystalline coatings with different Al content on a nickel-based single-crystal superalloy. Corros. Sci. 2020, 170, 108700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.Q.; Guo, H.B.; Peng, H.; Gong, S.K.; Xu, H.B. Improved alumina scale adhesion of electron beamphysical vapor deposited Dy/Hf-doped β-NiAl coatings. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2013, 283, 513–520. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, R.; Li, Y. Recent advances in the performance and mechanisms of high-entropy alloys under low- and high-temperature conditions. Coatings 2025, 15, 92. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Zhao, S.; Ritchie, R.O.; Meyers, M.A. Mechanical properties of high-entropy alloys with emphasis on face-centered cubic alloys. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2019, 102, 296–345. [Google Scholar]

- Miracle, D.B.; Senkov, O.N. A critical review of high entropy alloys and related concepts. Acta Mater. 2017, 122, 448–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, T.M.; Weaver, M.L. Oxidation behavior of arc melted AlCoCrFeNimulti-component high-entropy alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 674, 229–244. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, L.; Huang, A.; Liu, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Guo, F.; Zhao, X. Y-Hf co-doped Al1.1CoCr0.8FeNi high-entropy alloy with excellent oxidation resistance and nanostructure stability at 1200 °C. Scr. Mater. 2021, 203, 114105. [Google Scholar]

- Janda, D.; Fietzek, H.; Galetz, M.; Heilmaier, M. The effect of micro-alloying with Zr and Nb on the oxidation behavior of Fe3Al and FeAl alloys. Intermetallics 2013, 41, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Ullah, I.; Shah, S.S.A.; Aziz, T.; Zhang, S.H.; Song, G.S. Effect of Cr nanoparticle dispersions with various contents on the oxidation and phase transformation of alumina scale formation on Ni2Al3 coating. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2022, 438, 128397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhou, L.; Xi, Y.; Liu, L.; Liu, Z.; Si, J.; Zhu, K. Phase transformation behavior of alumina grown on FeAl alloys with reactive element dopants at 1273 K. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 692, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, T.L.; Marquis, E.A. Effects of minor alloying elements on alumina transformation during the transient oxidation of β-NiAl. Oxid. Met. 2021, 95, 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, K.; Kupka, M. High-temperature oxidation behaviour of B2 FeAl based alloy with Cr, Zr and B additions. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2012, 132, 902–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pint, B.A.; Hobbs, L.W. Limitations on the use of ion implantation for the study of the reactive element effect in β-NiAl. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1994, 141, 2443–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Wang, X.W. Modeling of θ→α alumina lateral phase transformation with applications to oxidation kinetics of NiAl-based alloys. Mater. Des. 2016, 112, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybichi, G.C.; Smialek, J.L. Effect of the θ-α-Al2O3 transformation on the oxidation behavior of β-NiAl+Zr. Oxid. Met. 1989, 31, 275–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Li, T.; Pan, W. Oxidation of a La2O3-modified aluminide coating. Scr. Mater. 2001, 44, 1033–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandee, P.; Gourlay, C.; Belyakov, S.; Patakham, U.; Zeng, G.; Limmaneevichitr, C. AlSi2Sc2 intermetallic formation in Al-7Si-0.3Mg-xSc alloys and their effects on as-cast properties. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 731, 1159–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pint, B.A. Progress in understanding the reactive element effect since the Whittle and Stringer literature review. In John Stringer Symposium on High Temperature Corrosion; ASM International: Novelty, OH, USA, 2003; pp. 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Li, L.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhao, X.; Guo, F.; Xiao, P. Y-Hf co-doped AlCoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy coating with superior oxidation and spallation resistance at 1100 °C. Corros. Sci. 2021, 182, 109267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burtin, P.; Brunelle, J.; Pijolat, M.; Soustelle, M. Influence of surface area and additives on the thermal stability of transition alumina catalyst supports. II: Kinetic model and interpretation. Appl. Catal. 1987, 34, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buban, J.P.; Matsunaga, K.; Chen, J.; Shibata, N.; Ching, W.Y.; Yamamoto, T.; Ikuhara, Y. Grain boundary strengthening in alumina by rare earth impurities. Science 2006, 311, 212–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.T.; Xu, C.M. Effect of NiAl microcrystalline coating on the high-temperature oxidation behavior of NiAl-28Cr-5Mo-1Hf. Oxid. Met. 2002, 58, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, P.; Priimak, K. Interfacial segregation, pore formation, and scale adhesion on NiAl alloys. Oxid. Met. 2005, 63, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pint, B.A.; Treska, M.; Hobbs, L.W. The effect of various oxide dispersions on the phase composition and morphology of Al2O3 scales grown on β-NiAl. Oxid. Met. 1997, 47, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pint, B.A. Experimental observations in support of the dynamic-segregation theory to explain the reactive-element effect. Oxid. Met. 1996, 45, 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, X.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Wang, S. Microstructure evolution and oxidation resistance properties of oxide dispersion strengthened FeCrAl alloys at 1100 °C. Vacuum 2024, 227, 113371. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya, M.; Bojarczuk, N.A.; Guha, S.; Ramanathan, S. Transmission electron microscopy studies on structure and defects in crystalline yttria and lanthanum oxide thin films grown on single crystal sapphire by molecular beam synthesis. Philos. Mag. 2010, 90, 1123–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmester, P.; Huber, G.; Kurfiss, M.; Schilling, M. Crystalline growth of cubic (Eu, Nd):Y2O3 thin films on α-Al2O3 by pulsed laser deposition. Appl. Phys. A 2005, 80, 627–630. [Google Scholar]

- Heffelfinger, J.R.; Carter, C.B. The effect of surface structure on the growth of ceramic thin films. Philos. Mag. Lett. 1997, 76, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pint, B.A. Optimization of reactive-element additions to improve oxidation performance of alumina-forming alloys. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2003, 86, 686–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittle, D.P.; Stringer, J. Improvements in high temperature oxidation resistance by additions of reactive elements or oxide dispersions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1980, 295, 309–329. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, H.; Chen, D.; Gao, X.; Liu, T.; Qin, G.; Chen, R.; Wu, S.; Guo, J.; Fu, H. Contribution of Sc doping to the growth and adhesion of alumina scale on AlCoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy. Scr. Mater. 2024, 252, 116272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Peng, X.; Tan, X.; Wang, F. The reactive element effect of ceria particle dispersion on alumina growth: A model based on microstructural observations. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).