Corrosion Behavior of Cu-Mg Alloy Contact Wire in Controlled Humid Heat Environments

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Material and Sample Preparation

2.2. Electrochemical Measurements

2.3. Surface Characterization

3. Results

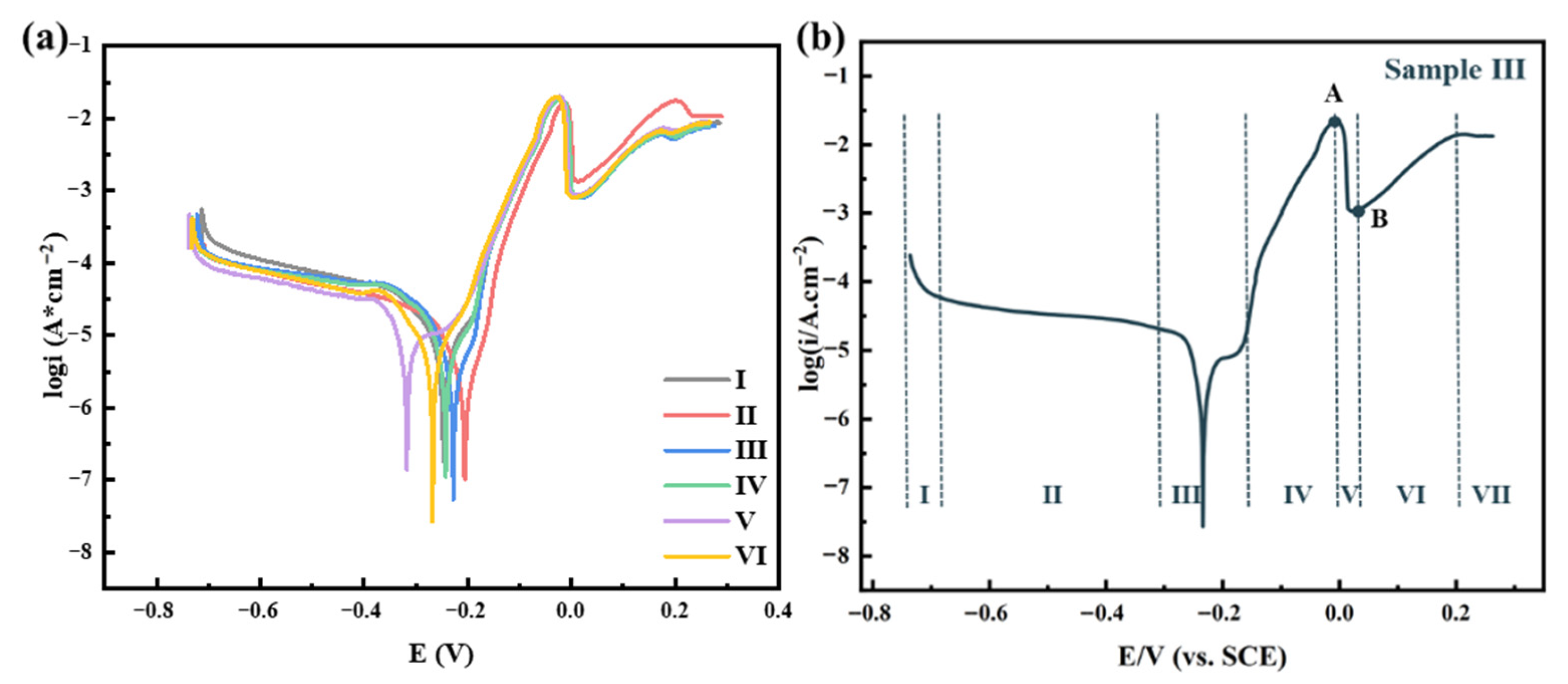

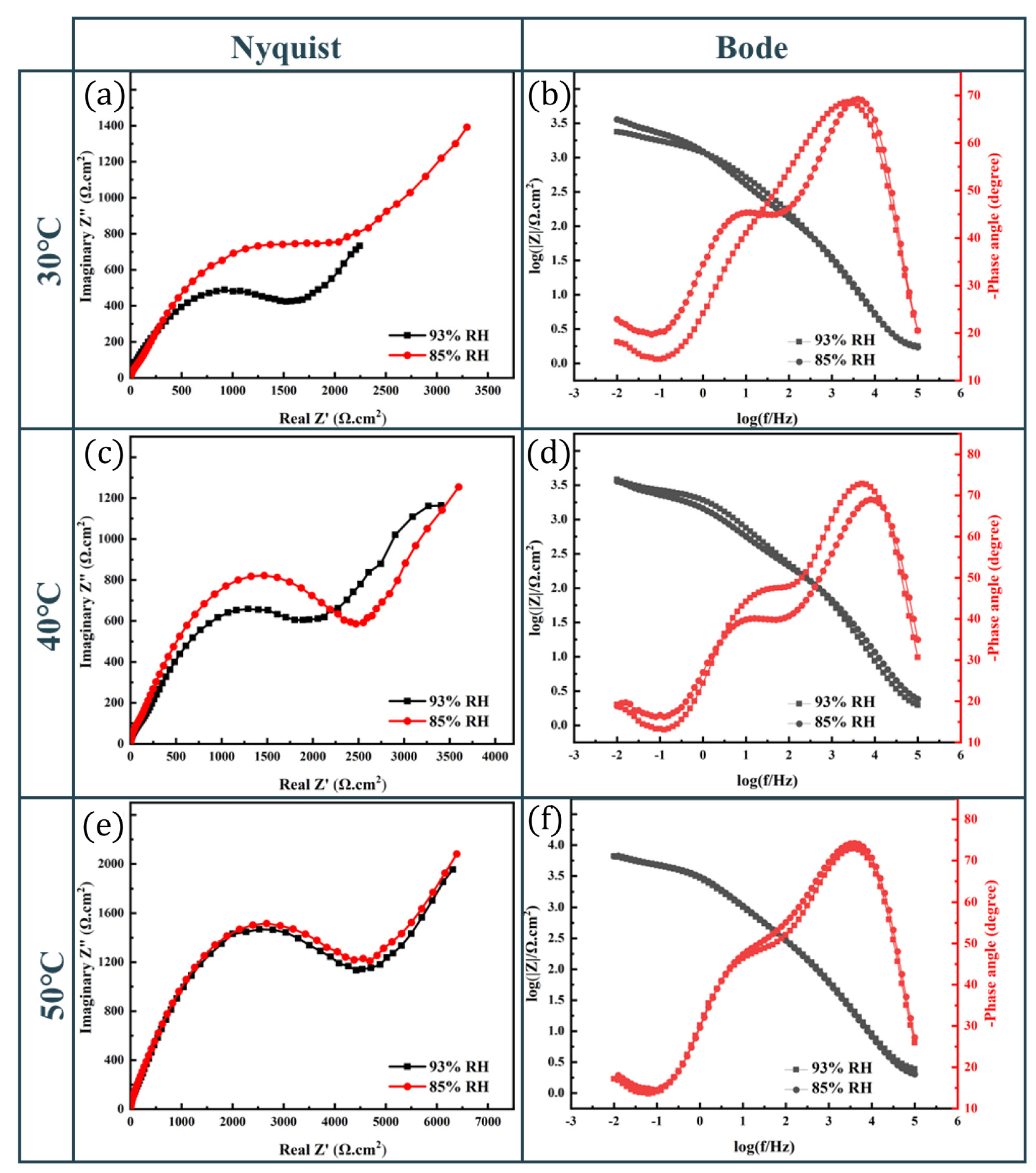

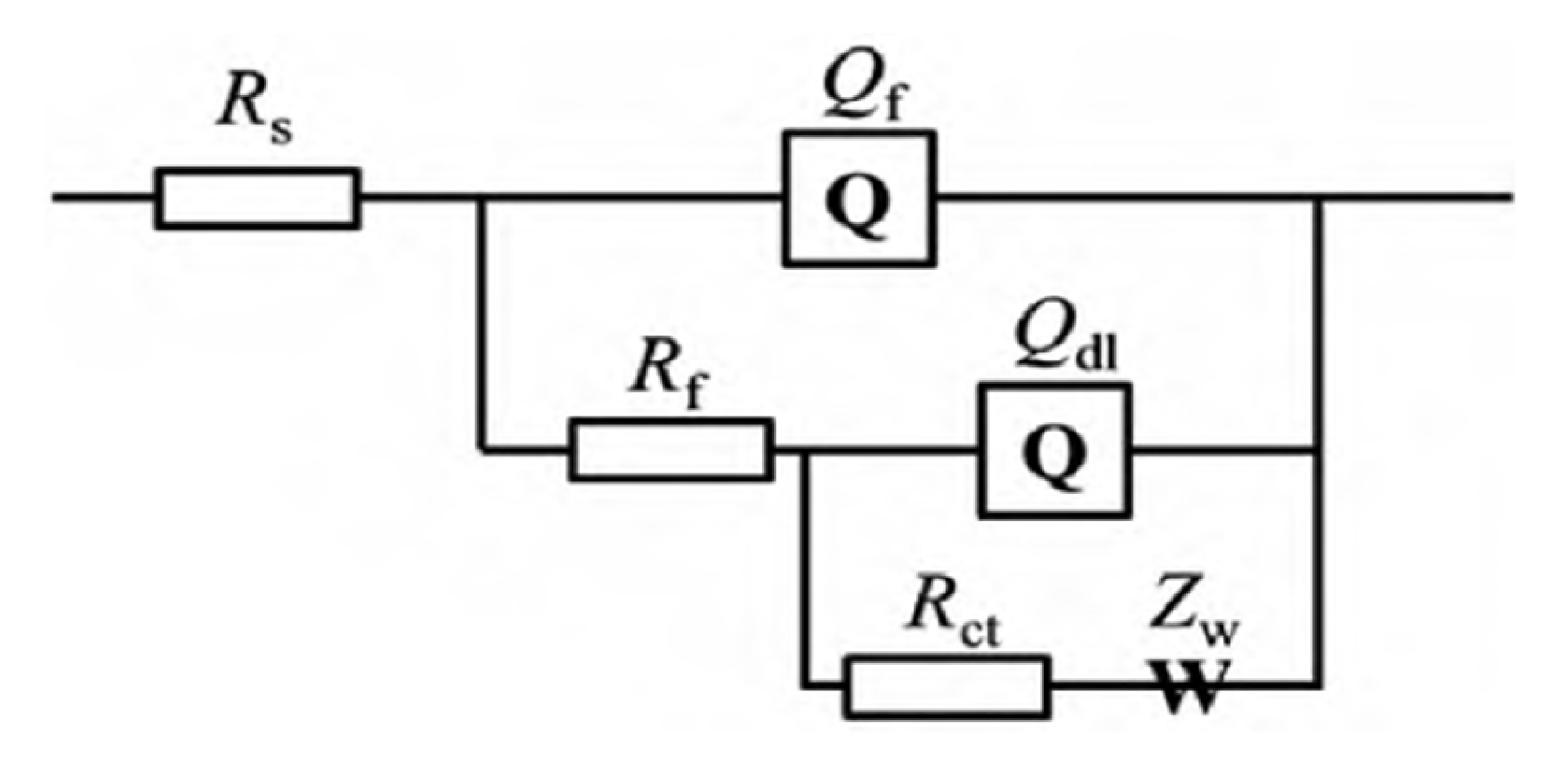

3.1. Electrochemical Properties

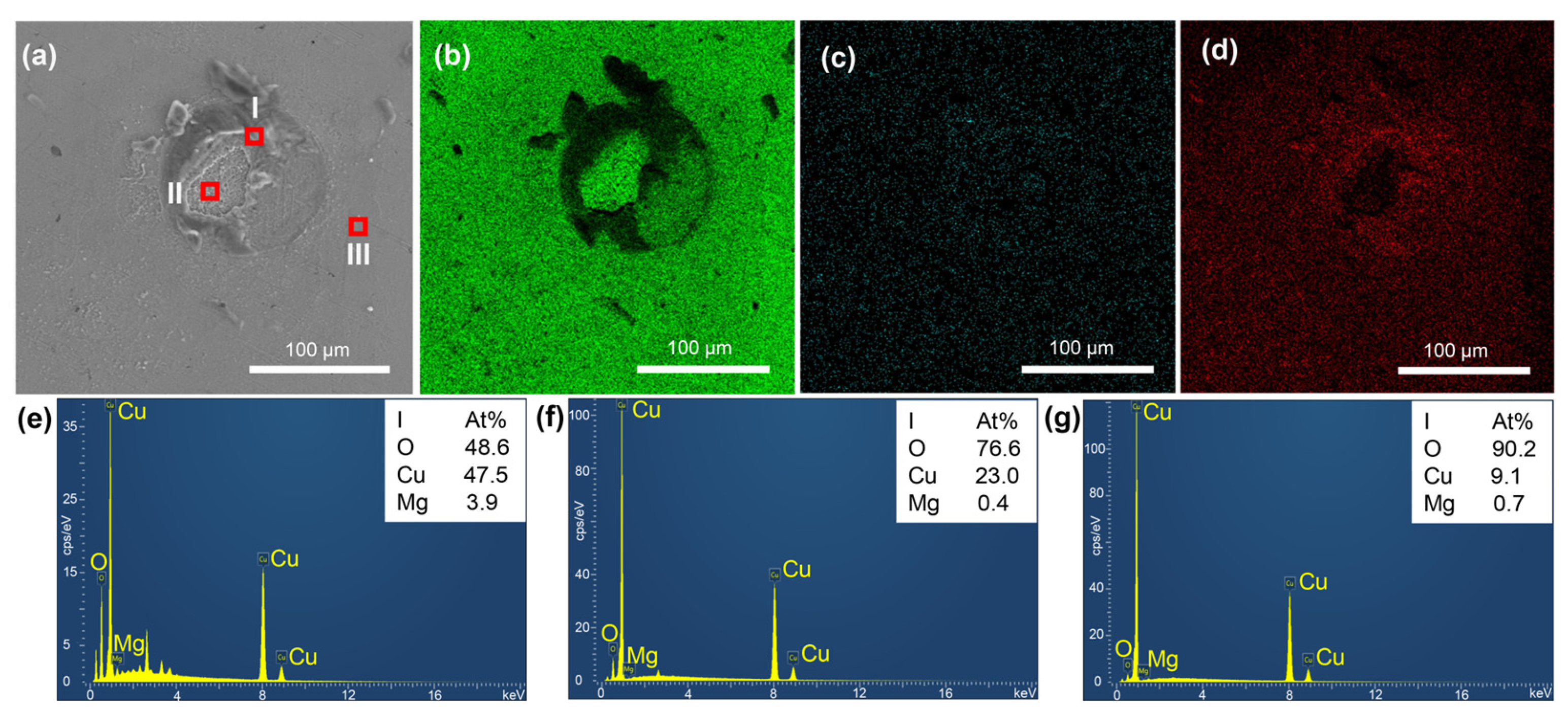

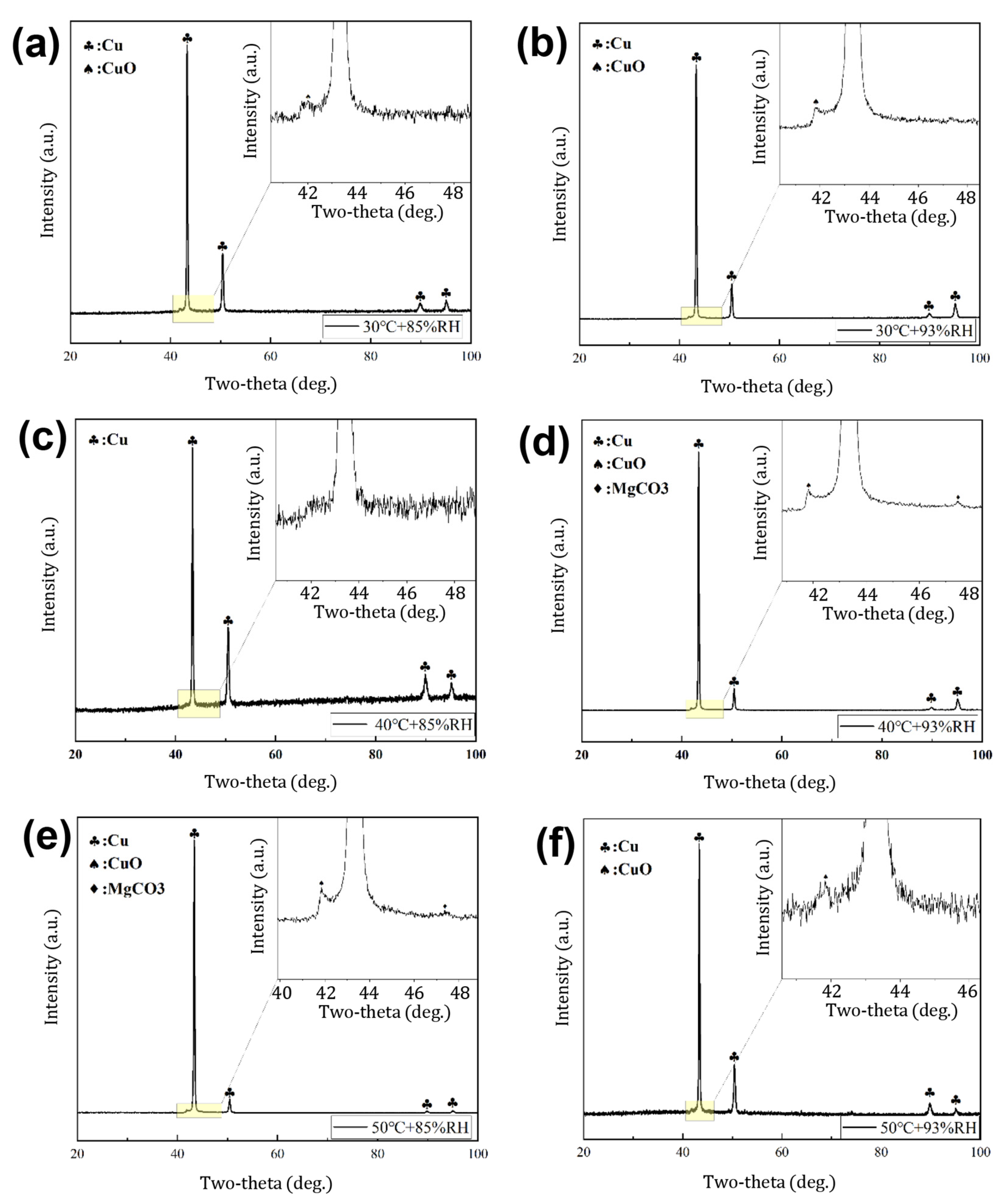

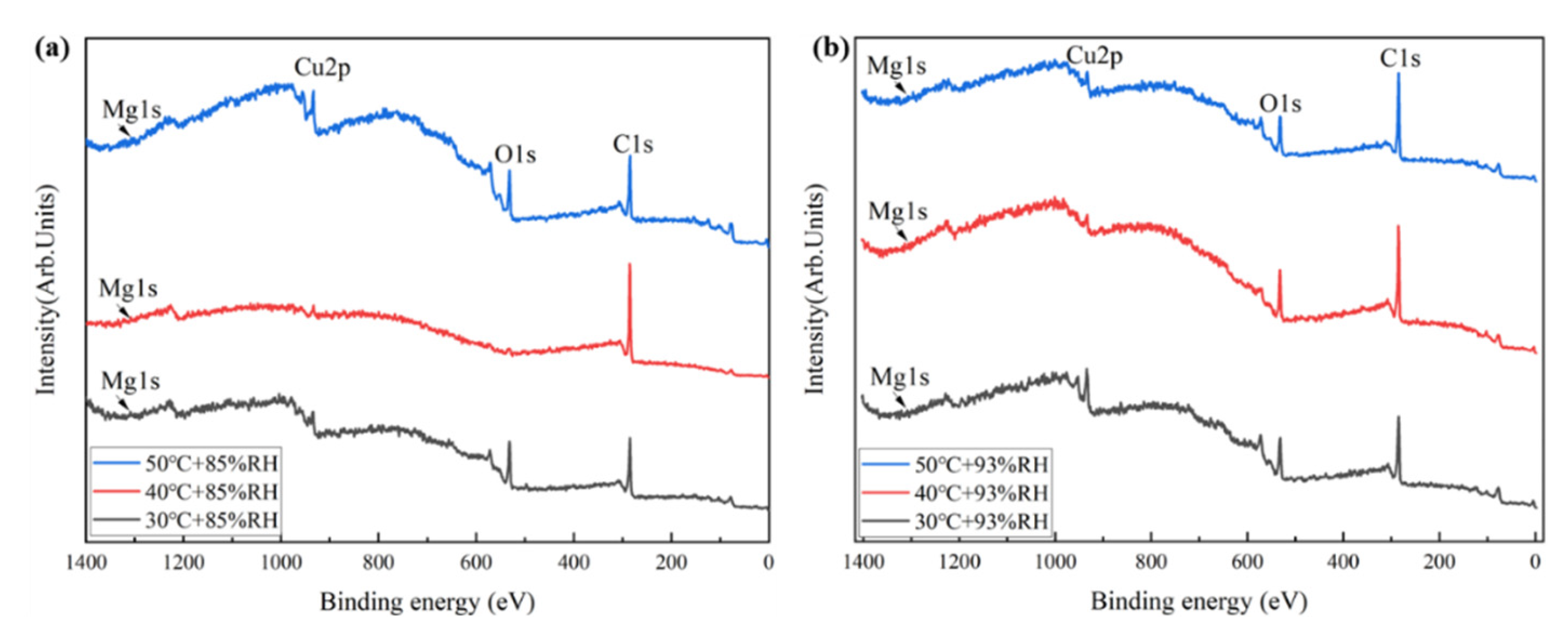

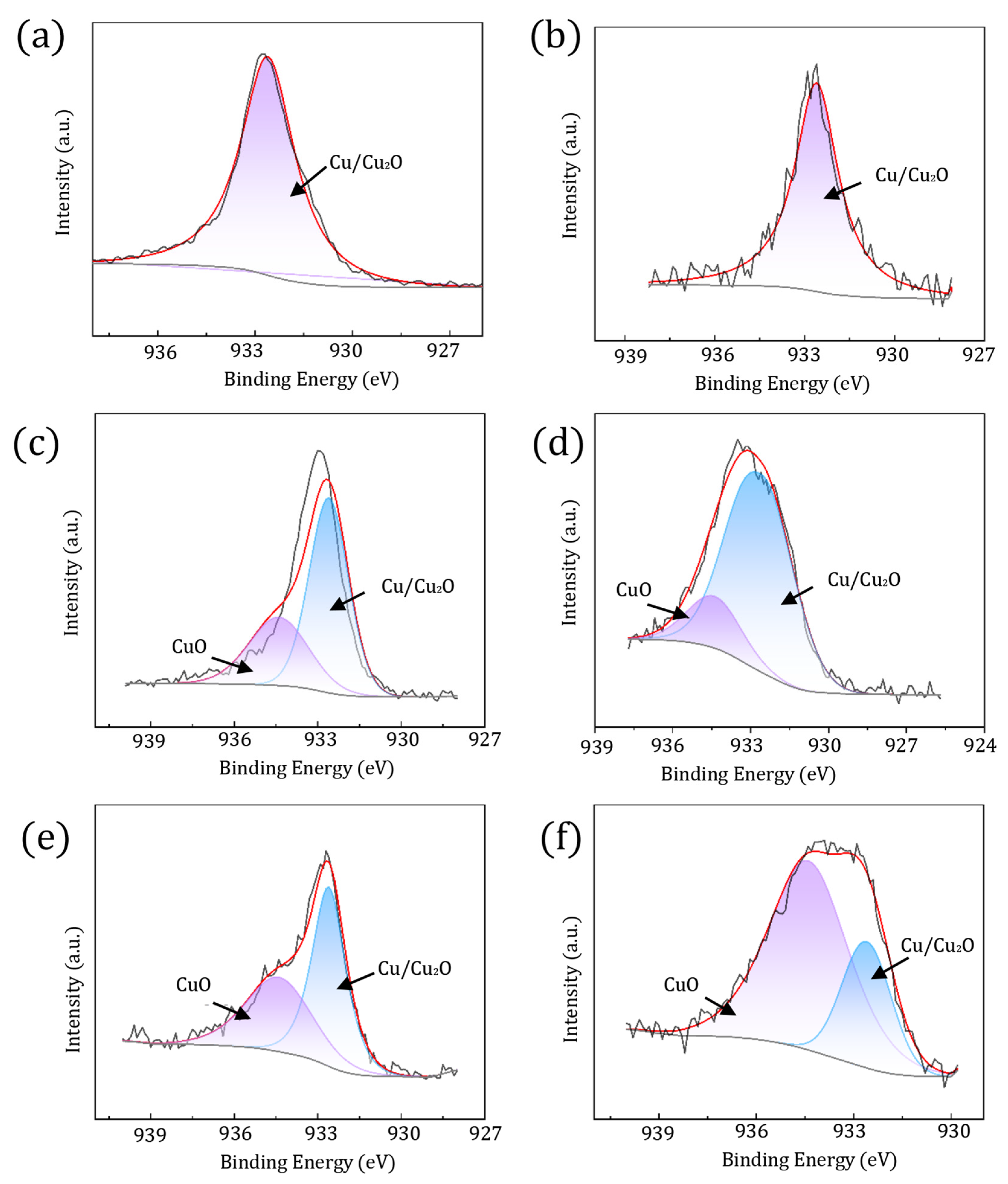

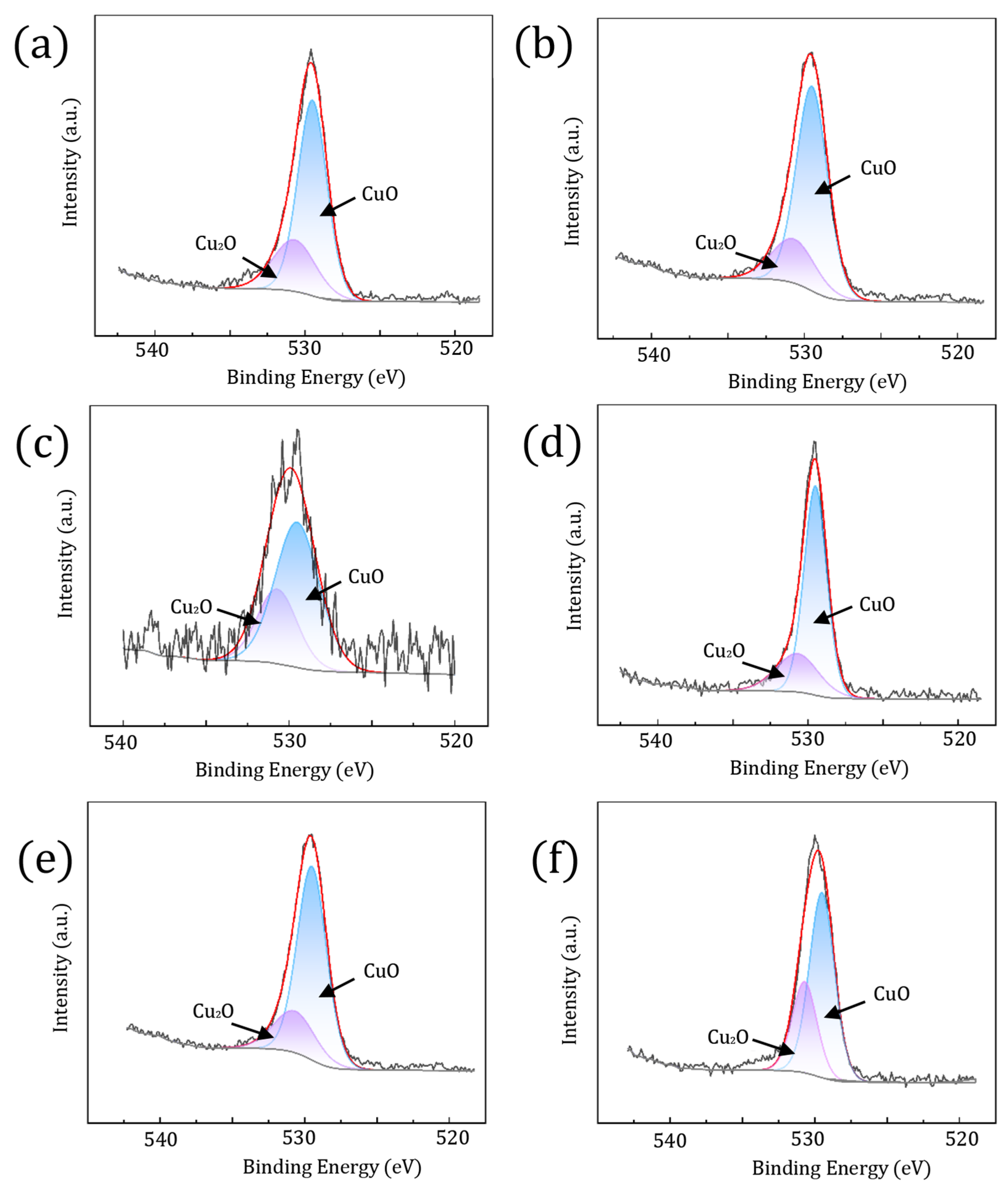

3.2. Corrosion Film Characterization

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Cu-Mg alloys exhibit significantly better corrosion resistance after exposure to higher-temperature (50 °C) and lower-relative humidity (85% RH) conditions compared to lower temperature (30 °C) and higher humidity (93% RH). This is demonstrated by lower corrosion current densities, as well as the higher corrosion film and charge transfer resistances.

- (2)

- Temperature and humidity exert distinct influences on corrosion film formation. Elevated temperatures accelerate the kinetics of film growth and promote the formation of denser, more continuous, and adherent protective layers. High relative humidity accelerates the overall corrosion rate by providing a more substantial electrolyte layer but tends to result in less compact, potentially cracked or discontinuous films, especially at lower temperatures.

- (3)

- The corrosion films formed on the Cu-Mg alloy under the tested humid heat conditions are primarily composed of copper oxides, specifically Cu2O and CuO. The proportion of CuO increases significantly with increasing exposure temperature. Despite Mg’s presence in the alloy, its contribution to the composition of the mature surface film is minimal, with only trace amounts of Mg-containing species detected.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kalhor, A.; Rodak, K.; Tkocz, M.; Myalska-Głowacka, H.; Schindler, I.; Poloczek, Ł.; Radwański, K.; Mirzadeh, H.; Grzenik, M.; Kubiczek, K.; et al. Tailoring the microstructure, mechanical properties, and electrical conductivity of Cu–0.7Mg alloy via Ca addition, heat treatment, and severe plastic deformation. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2024, 24, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Li, Z.; Qiu, W.; Xiao, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Jiang, Y. Microstructure and properties of Cu–Mg-Ca alloy processed by equal channel angular pressing. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 788, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Han, J.-N.; Zhou, B.-W.; Xue, Y.-Y.; Jia, F.; Zhang, X.-G. Effects of rolling and annealing on microstructures and properties of Cu–Mg–Te–Y alloy. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2014, 24, 1046–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Wang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, B.; Volinsky, A.A.; Liu, Y.; Wang, G. Mechanical and electrical properties and phase analysis of aged Cu-Mg-Ce alloy. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2020, 29, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, B.; An, J.; Volinsky, A.A.; Sun, H.; Liu, Y.; Song, K. Effects of Ce addition on the Cu-Mg-Fe alloy hot deformation behavior. Vacuum 2018, 155, 594–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, B.; Yakubov, V.; An, J.; Volinsky, A.A.; Liu, Y.; Song, K.; Li, L.; Fu, M. Effects of Ce and Y addition on microstructure evolution and precipitation of Cu-Mg alloy hot deformation. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 781, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhou, Y.; Song, K.; Wang, X.; Liang, S. Microstructure and properties of Cu–Mg alloy treated by internal oxidation. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2018, 34, 648–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, A.; Zhu, C.; Chen, J.; Jiang, J.; Song, D.; Ni, S.; He, Q. Grain refinement and high-performance of equal-channel angular pressed Cu-Mg alloy for electrical contact wire. Metals 2014, 4, 586–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, Y.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, L.; Tang, Z.; Zuo, T.; Xue, J.; Xiao, L.; Li, X. Microstructure and properties of high strength and high conductivity Cu-0.4Mg alloy processed by upward continuous casting and multi-pass drawing. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2024, 33, 5041–5048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Wei, H.; Kou, J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, D. Mechanical properties test of butt welds of corroded Q690 high strength steel under the coupling of damp-heat cycle dipping. Appl. Ocean Res. 2021, 111, 102677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Tian, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, G.; Deng, J. Study on the erosion-corrosion behavior of copper-nickel alloys in high temperature and high humidity marine environment. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2025, 2951, 012103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzarti, Z.; Arrousse, N.; Serra, R.; Cruz, S.; Bastos, A.; Tedim, J.; Salgueiro, R.; Cavaleiro, A.; Carvalho, S. Copper corrosion mechanisms, influencing factors, and mitigation strategies for water circuits of heat exchangers: Critical review and current advances. Corros. Rev. 2025, 43, 429–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattendorf, H. A 48% Ni–Fe alloy of low coercivity and improved corrosion resistance in a cyclic damp heat test. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2001, 231, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.J.; Pehkonen, S.O. Surface characterization and corrosion behavior of 70/30 Cu–Ni alloy in pristine and sulfide-containing simulated seawater. Corros. Sci. 2007, 49, 1276–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Xing, H.; Du, M.; Sun, M.; Ma, L. Accelerated corrosion of 70/30 copper-nickel alloys in sulfide-polluted seawater environment by sulfide. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, 8620–8634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Li, L.; Yin, W.; Chu, G.; Guan, Y. Investigation of corrosion behavior and film formation on 90Cu-10Ni alloys immersed in simulated seawater. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2023, 18, 100244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhu, A.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhu, Y. Surface characterization and corrosion behavior of a novel gold-imitation copper alloy with high tarnish resistance in salt spray environment. Corros. Sci. 2013, 76, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yao, J.; Xu, M. Corrosion analysis for the effect on products in alternating salt fog test and damp heat test. In Proceedings of the 2011 9th International Conference on Reliability, Maintainability and Safety, Guiyang, China, 12–15 June 2011; pp. 1116–1120. [Google Scholar]

| Sample No. | Temperature (°C) | Relative Humidity (RH%) |

|---|---|---|

| I | 30 ± 2 | 85 ± 3 |

| II | 30 ± 2 | 93 ± 3 |

| III | 40 ± 2 | 85 ± 3 |

| IV | 40 ± 2 | 93 ± 3 |

| V | 50 ± 2 | 85 ± 3 |

| VI | 50 ± 2 | 93 ± 3 |

| Sample No. | ba (mV/Dec) | bc (mV/Dec) | Ec (V) | ic (μA/cm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 54 | −71 | −0.264 | 3.55 |

| II | 66 | −40 | −0.313 | 3.74 |

| III | 52 | −33 | −0.244 | 2.43 |

| IV | 51 | −56 | −0.22 | 2.30 |

| V | 36 | −58 | −0.205 | 2.01 |

| VI | 34 | −38 | −0.244 | 2.24 |

| No. | Rs (Ω cm−2) | 105 × Qf (Scm−2sn) | n1 | Rf (Ω cm−2) | 105 × Qdl (Scm−2sn) | n2 | Rct (Ω cm−2) | 103 × (Scm−2s0.5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 1.5 | 1.27 | 0.88 | 13 | 15.0 | 0.54 | 256 | 3.8 | 2.69 |

| II | 1.4 | 0.84 | 0.91 | 9.4 | 18.4 | 0.61 | 167 | 2.8 | 3.35 |

| III | 1.5 | 0.43 | 0.92 | 163 | 7.24 | 0.65 | 2516 | 3.1 | 2.03 |

| IV | 1.6 | 0.44 | 0.89 | 129 | 1.39 | 0.59 | 2324 | 2.5 | 6.19 |

| V | 1.6 | 0.44 | 0.92 | 240 | 6.8 | 0.61 | 5050 | 2.1 | 2.46 |

| VI | 2.0 | 0.55 | 0.92 | 223 | 6.3 | 0.63 | 4893 | 2.0 | 2.48 |

| Sample No. | Cu | Mg | O |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | 82.4 | 0.4 | 17.2 |

| II | 80.7 | 0.7 | 18.6 |

| III | 74.5 | 0.7 | 24.8 |

| IV | 74.5 | 0.5 | 25.0 |

| V | 53.7 | 0.5 | 45.8 |

| VI | 60.1 | 1.0 | 38.9 |

| Valence State | Sample | Proposed Compounds | Binding Energy (eV) | FWHM (eV) | Relative Quantity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu2p3 | I | Cu/Cu2O | 932.6 | 2.0 | 100 |

| II | Cu/Cu2O | 932.6 | 1.7 | 100 | |

| III | Cu/Cu2O | 932.6 | 1.7 | 65.3 | |

| CuO | 934.4 | 2.6 | 34.7 | ||

| IV | Cu/Cu2O | 932.6 | 2.8 | 82.2 | |

| CuO | 934.4 | 2.5 | 17.8 | ||

| V | Cu/Cu2O | 932.6 | 1.5 | 55.0 | |

| CuO | 934.4 | 2.9 | 45.0 | ||

| VI | Cu/Cu2O | 932.6 | 1.8 | 27.8 | |

| CuO | 934.4 | 3.0 | 72.2 |

| Valence State | Sample | Proposed Compounds | Binding Energy (eV) | FWHM (eV) | Relative Quantity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mg1s | I | Mg | 1303.2 | 0.5 | 32.1 |

| MgO | 1303.9 | 0.6 | 67.9 | ||

| II | Mg | 1303.2 | 1.3 | 80.5 | |

| MgO | 1303.9 | 0.7 | 19.5 | ||

| III | Mg | 1303.2 | 0.6 | 48.6 | |

| MgO | 1303.9 | 0.7 | 51.4 | ||

| IV | Mg | 1303.2 | 1.0 | 68.3 | |

| MgO | 1303.9 | 0.5 | 31.7 | ||

| V | Mg | 1303.2 | 0.5 | 83.7 | |

| MgO | 1303.9 | 0.5 | 16.3 | ||

| VI | Mg | 1303.2 | 1.7 | 49.7 | |

| MgO | 1303.9 | 1.3 | 50.3 |

| Valence State | Sample | Proposed Compounds | Binding Energy (eV) | FWHM (eV) | Relative Quantity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O1s | I | CuO | 529.5 | 2.4 | 72.0 |

| Cu2O | 530.7 | 3.5 | 28.0 | ||

| II | CuO | 529.5 | 2.3 | 76.1 | |

| Cu2O | 530.7 | 3.3 | 23.9 | ||

| III | CuO | 529.5 | 3.2 | 68.2 | |

| Cu2O | 530.7 | 3.0 | 31.8 | ||

| IV | CuO | 529.5 | 1.8 | 74.3 | |

| Cu2O | 530.7 | 3.5 | 25.7 | ||

| V | CuO | 529.5 | 2.5 | 76.7 | |

| Cu2O | 530.7 | 3.5 | 23.3 | ||

| VI | CuO | 529.5 | 2.1 | 67.5 | |

| Cu2O | 530.7 | 2.1 | 32.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yuan, Y.; Jiang, X.; Pan, L.; Pang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, Z. Corrosion Behavior of Cu-Mg Alloy Contact Wire in Controlled Humid Heat Environments. Coatings 2025, 15, 1435. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121435

Yuan Y, Jiang X, Pan L, Pang Y, Wang Z, Xiao Z. Corrosion Behavior of Cu-Mg Alloy Contact Wire in Controlled Humid Heat Environments. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1435. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121435

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuan, Yuan, Xinyao Jiang, Like Pan, Yong Pang, Zejun Wang, and Zhu Xiao. 2025. "Corrosion Behavior of Cu-Mg Alloy Contact Wire in Controlled Humid Heat Environments" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1435. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121435

APA StyleYuan, Y., Jiang, X., Pan, L., Pang, Y., Wang, Z., & Xiao, Z. (2025). Corrosion Behavior of Cu-Mg Alloy Contact Wire in Controlled Humid Heat Environments. Coatings, 15(12), 1435. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121435