Abstract

High-entropy alloys (HEAs), as a novel class of materials, have attracted widespread attention in the field of materials science due to their unique multi-element high-concentration mixing design. Recent research has found that this alloy mixing strategy not only exhibits excellent performance in structural properties but also shows potential in functional materials. This review summarizes the progress of research on HEAs in the magnetocaloric effect (MCE) area, first introducing the basic principles of MCE and the related concepts of HEAs. It then summarizes the research progress of rare-earth HEAs, non-rare-earth HEAs, and rare-earth-transition metal composite HEAs in MCE. Finally, this review outlines future research directions for HEAs in the MCE field, laying the groundwork for further applications of HEAs in the magnetocaloric field.

1. Introduction

Alloy design has been a key focus in metallurgy and materials science for many years. Traditional alloys (TAs) typically involve using a couple of main base elements, incorporated with trace amounts of other elements to optimize specific characteristics. For example, Inconel 718 [1] is primarily composed of Ni, with Cr, Fe, and Al added to enhance oxidation resistance and strength. Ti-6Al-4V [2] is based on titanium, with aluminum and vanadium added to improve ductility and corrosion resistance. While effective, these design approaches are limited by the number of elements and combinations that can be used. As the demand for more advanced materials grows, the design methods of TAs face limitations.

In 2004, HEAs were introduced to address these limitations [2,3]. HEAs are composed of a minimum of five elements in roughly equal atomic-scale proportions, expanding the design space and allowing for more complex compositions. The uniqueness of HEAs lies in their multi-element random solid-solution structure, stabilized by elevated configurational entropy, typically exceeding 1.5 R (where R denotes the gas constant). This elevated entropy promotes a disordered distribution of elements within the lattice interior, resulting in a stable disordered solid solution structure [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. At the same time, the different elements in HEAs can interact synergistically at the atomic scale through the “cocktail effect.” Based on this effect, researchers have developed various HEAs with distinct properties, such as the AlCoCrFeNi alloy [18,19,20,21,22,23] with high strength and high-temperature stability, the CoCrFeMnNi alloy [14,24,25,26] with high toughness and fatigue resistance, and the TiZrHfNbTa refractory HEA [27,28], which offers both high-temperature and corrosion resistance.

In recent years, with the deepening of research into the properties of HEAs, researchers have found that these alloys not only perform excellently as structural materials, but their potential as functional materials is also worth paying attention to [29,30,31]. Magnetocaloric materials, founded on the MCE, are a class of functional materials that are capable of producing reversible temperature changes by rearranging the material’s magnetic moments in response to changes in the external magnetic field, thus enabling temperature regulation and thermal management. Magnetocaloric materials are utilized in magnetic refrigeration technology [32,33], which, compared to traditional gas-compression refrigeration, offers advantages such as pollution-free operation, low noise, and high energy efficiency, with superior performance in terms of both energy efficiency and environmental friendliness. As ecological policies become more stringent, its role as a green and sustainable cooling method to replace traditional compression refrigeration has become an important research direction for future cooling technologies.

In the field of magnetocaloric materials, the unique design concept of HEAs can leverage its advantages. This concept enables HEAs to operate across different temperature and magnetic field ranges. By optimizing element selection and alloy structure, it further allows precise control of the magnetocaloric effect. In particular, the multi-principal-element design overcomes the limitations of traditional magnetocaloric materials that focus on optimizing a single property, achieving a balanced improvement in magnetism (such as Curie temperature and saturation magnetization), lattice-related strength (elevated-temperature tensile mechanical strength), and resistance to corrosion (such as resistance to low-temperature refrigerant corrosion), thus broadening their application range and making HEAs a promising research material in the realm of magnetic cooling.

Based on this, this article will review HEAs in terms of the magnetocaloric effect, material performance, properties, design strategies for magnetocaloric high-entropy alloys, and recent research progress, offering insights for their application in magnetic refrigeration and providing references arguing the use of elevated-entropy alloys as functional materials.

2. Magnetocaloric Effect in Materials

2.1. Magnetocaloric Effect

MCE describes the reversible temperature change that occurs in magnetic materials when exposed to fluctuations in an external magnetic field [34]. When a magnetic field is introduced, the dipoles within the material align with the field, causing changes in the material’s magnetic entropy. This change in entropy results in a variation in the material’s heat capacity, leading to a rise or fall in temperature.

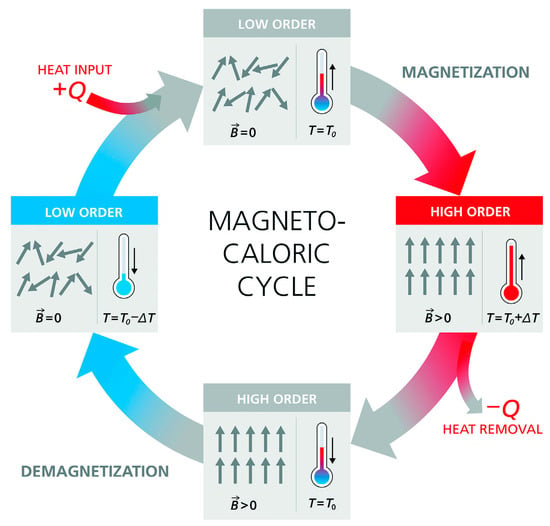

Figure 1 illustrates the magnetocaloric cycle process, which involves multiple phases. Initially, when no external magnetic field is present, the intrinsic magnetic moments within the material are randomly oriented, resulting in low magnetic order and high entropy. When an external magnetic field is applied, the magnetic moments align with the field, resulting in increased magnetic order and a decrease in entropy. This reduction in entropy causes the material’s temperature to rise, allowing it to release heat to the surrounding environment. Once the external field is eliminated, the magnetic moments revert to a random arrangement, increasing the entropy and lowering the temperature. At this point, the material absorbs heat from its surroundings. By continuously applying and removing the external magnetic field, the material alternates between the magnetization phase, during which it releases heat, and the demagnetization phase, during which it absorbs heat. By effectively utilizing the demagnetization process, a continuous cooling effect can be created.

Figure 1.

Working principle of the magnetocaloric cycle [32].

2.2. Classification of Magnetocaloric Materials

Magnetocaloric materials are divided into two types according to their phase transition characteristics: first-order phase transition materials (FOPT) and second-order phase transition materials (SOPT) [33,35]. FOPTs are typically associated with abrupt structural or magnetic changes, such as the shift from a ferromagnetic to a paramagnetic state, exhibiting significant changes in magnetic entropy and abrupt changes in heat capacity. These phase transitions are typically discontinuous and accompanied by lattice distortion, resulting in large thermal hysteresis and a narrow temperature range for adjustment, which in turn leads to lower cooling efficiency. The phase transition of first-order materials is accompanied by significant structural changes that occur rapidly within a specific temperature range, resulting in a sharp shift in magnetic entropy.

In contrast, the phase transition process of SOPT is smoother, with continuous changes in magnetism or structure, without accompanying lattice distortion. This makes second-order phase transition materials exhibit more stable performance in the magnetocaloric effect, with a broader operating temperature range, making them suitable for applications that require stable temperature control. However, materials undergoing second-order phase transitions exhibit a more minor change in magnetic entropy, leading to a less pronounced magnetocaloric effect. Therefore, to fully utilize the advantages of magnetocaloric materials in practical applications, it is essential to consider both performance requirements and specific application scenarios.

Apart from classification based on phase transition types, magnetocaloric materials can also be categorized according to their temperature ranges [36], including low temperature (below 20 K), mid-temperature (20–77 K), and high temperature (above 77 K).

2.3. Efficiency Metrics

MCE is characterized by the change in magnetic entropy, reflecting the shift in the material’s magnetic state due to variations in the external magnetic field. This change depends on the material’s magnetization properties and the field’s variation, peaking at the phase transition point. The intensity of the magnetocaloric effect can be characterized by the isothermal magnetization curve [37], with the specific mathematical relationship derived from Maxwell’s equations, as shown below [38]:

where ΔSM (H, T) is the isothermal magnetic entropy change; H is the magnetic field strength; M is the magnetization; T is the temperature. Equation (1) indicates that the magnetocaloric effect is proportional to the partial derivative of magnetization M with respect to temperature T (∂M/∂T). Thus, the material’s magnetic entropy change peaks near the Curie temperature, where the magnetization change is greatest, maximizing the effect.

In addition to ∆SM, which is an important parameter for evaluating the performance of magnetic refrigeration materials, other key parameters such as temperature-averaged magnetic entropy change (TEC), relative cooling power (RCP), and refrigerant capacity (RC) are also crucial for assessing the material’s magnetic refrigeration performance. TEC is used to measure the average cooling capacity of a material near its magnetic transition temperature. It is calculated by integrating the ∆SM over a given temperature range and averaging the values, as shown by the formula [37,38]:

where ΔTH−C represents the temperature range for cooling; Tc is the central temperature of the ΔTH−C range, typically corresponding to the material’s Curie temperature.

Both RC and RCP indicate the amount of cooling output achievable per unit mass of the material and reflect its cooling performance. The expressions for RC [39] and RCP [40] are as follows:

where T1 and T2 are the starting and ending temperatures of the temperature range δTFWHM, corresponding to the half-width temperature range around the maximum magnetic entropy change.

These parameters are important indicators to assess whether a material can meet the required refrigeration effect in practical applications. The higher the RC and RCP values, the better the magnetic refrigeration performance, higher energy efficiency, and the more effective the cooling effect. These parameters not only directly reflect the cooling efficiency during the magnetic field cycle but also reveal the material’s energy conversion efficiency and thermodynamic cycle characteristics.

3. Definition and Characteristics of HEAs

3.1. Component Definition

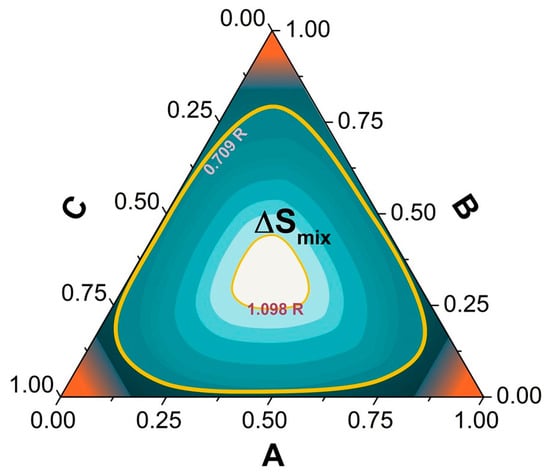

HEAs differ from traditional alloy design methods in that they employ a multi-principal-element design concept, where multiple principal elements are combined at high concentrations to form the alloy [30,41]. TAs typically depend on a limited number of principal constituents to define the alloy composition, whereas HEAs enhance the alloy’s configurational entropy (ΔSmix) by combining multiple elements [42]. Figure 2 displays the contour map of ΔSmix for a ternary alloy system [43], from which it is evident that when the alloy composition approaches the center equiatomic region, ΔSmix is maximized, indicating that the multi-element design stabilizes the free energy of the alloy system.

Figure 2.

Contour graph of ΔSmix for a model ternary alloy [44].

The original definition of HEAs specified that they consist of five or more principal elements in equal proportions, creating a single-phase disordered structure [45]. With ongoing advances in understanding these new materials, the component definition of HEAs has expanded in multiple dimensions: on one hand, the composition range has extended from the equiatomic region to the non-equiatomic region, allowing for optimization of properties by adjusting the element ratios; on the other hand, the phase structure requirement is no longer limited to a single-phase solid solution, further expanding the scope of research. Current research on HEAs has expanded to include systems with four principal elements: intermetallic compounds, ceramic compounds, and various multiphase microstructures [46,47,48,49,50], providing more possibilities for future performance exploration and application development.

3.2. Configurational Entropy in HEAs

HEAs increase configurational entropy by mixing multiple principal elements in high concentrations, thereby enhancing the system’s disorder, improving alloy stability, and suppressing phase separation. The formula for ΔSmix is as follows:

where R is the gas constant, this formula allows for the quantitative evaluation of the alloy’s configurational entropy. The high ΔSmix enables the elements to randomly distribute within the lattice randomly, forming a stable solid solution, unlike the ordered intermetallic compounds that tend to form when multiple components are mixed in traditional alloys. If the elements are distributed in an equiatomic ratio, theΔSmix of a five-component high-entropy alloy can reach a maximum of 1.61 R. It is currently widely accepted that ΔSmix ≥ 1.5 R is the threshold for considering HEAs [49,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61].

3.3. Design Strategies

The core design strategies of HEAs aim to achieve the target performance through the entropy stabilization mechanism and multi-principal-element synergistic effect within a combined system of composition, structure, and process control [47,62,63,64,65]. In the design process, the selection of components, optimization of proportions, phase structure control, appropriate process parameters, and the use of computational tools are all essential means to ensure that the performance of HEAs meets the expected requirements [66,67,68]. For magnetic HEAs [69,70,71], the primary design goal is to create functional alloys that exhibit significant temperature changes under an applied magnetic field, while also incorporating certain structural properties such as strength and oxidation resistance, depending on the application scenario.

Therefore, the composition design of magnetic HEAs is typically based on equiatomic or near-equiatomic atomic compositions, selecting elements with magnetic characteristics, such as rare-earth elements like Dy and Gd [72,73,74,75], and transition metal magnetic elements like Fe, Ni, and Co [76,77,78,79]. To achieve high entropy and form a stable structure, elements with similar atomic radii and small differences in electronegativity are chosen to maximize the contribution of entropy, thus controlling the elemental ratio and ensuring the alloy’s thermodynamic stability [80,81,82,83]. In addition, the influence of processing on the alloy’s performance, such as melting temperature, cooling rate, and other thermophysical parameters, is also considered to achieve the desired alloy performance. Currently, existing research mainly revolves around three types of element combination strategies: rare-earth HEAs, non-rare-earth HEAs, and rare-earth-transition metal element alloys. The subsequent chapters will review the current research status based on this classification method.

4. Magnetic HEAs Research Status

4.1. Rare-Earth HEAs

Rare-earth elements, as lanthanide elements in the periodic table, possess significant magnetic characteristics due to their unique 4f electron shell structure. The unpaired electrons in the 4f orbitals can form intense magnetic moments in response to an external magnetic field. Additionally, due to the strong spin–orbit coupling effect, the magnetic moments align or adjust rapidly, resulting in significant magnetic entropy changes and exhibiting strong magnetocaloric effects [84,85,86]. Building on these characteristics, research into fully rare-earth HEAs for magnetocaloric applications has gradually expanded. Their multi-element design not only enhances the configurational entropy that ensures structural stability but also enables flexible control of magnetic phases. Benefiting from the strong spin–orbit coupling of rare-earth atoms, these HEAs exhibit adjustable magnetic moments under external field conditions, can operate into a broader temperature range, and thus hold the potential to achieve large magnetic entropy changes.

Y. Yuan et al. [87] studied the structure and magnetocaloric properties of a five-element rare-earth HEA consisting of Gd, Dy, Er, Ho, and Tb. The Gd20Dy20Er20Ho20Tb20 HEA has an HCP structure, with all elements randomly solid-solved in the lattice, and no second phase precipitation. The alloy exhibits a Neel temperature (TN) of 186 K, characterized by a field-induced antiferromagnetic-to-ferromagnetic transition under high magnetic fields. In a 5 T magnetic field, ΔSM values are 8.6 J·kg−1·K−1, and RC is 627 J·kg−1, with a magnetic hysteresis loss of approximately 7 J·kg−1, giving an effective RC of about 620 J·kg−1. Specific heat tests show a λ-type peak at 186 K, consistent with the magnetization results. The alloy’s yield strength is approximately 250 MPa, with a plastic strain of over 20%. Compared with magnetocaloric alloys such as quaternary Gd25Er25Ho25Tb25 and Dy25Er25Ho25Tb25 alloys and ternary Er33.33Ho33.33Tb33.34 alloys in the same system, the latter two have HCP plus trigonal dual-phase structures. Under a 3 T, their ΔSM values are only 0.65 to 4.8 J·kg−1·K−1 and 3 J·kg−1·K−1, with RC values of 27.3 to 137 J·kg−1 and 150 J·kg−1, which are far lower than those of the quinary HEA.

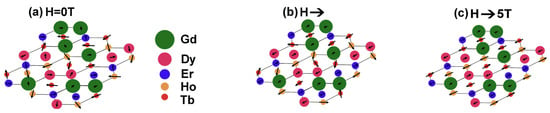

Figure 3 is a schematic representation of the alloy’s magnetic moment orientation, illustrating an HCP structure of rare-earth elements, represented by circles of varying sizes, with the arrow length indicating the magnitude of the magnetic moment. When there is no magnetic field present, due to the random local pinning potential caused by high configurational entropy, the magnetic moments of all elements are completely disordered. At low magnetic fields, elements with smaller magnetic moments (such as Er and Ho) preferentially align. In comparison, elements with larger magnetic moments (such as Gd and Tb) remain partially disordered. At high magnetic fields, the field strength is sufficient to overcome the local pinning potential, and the magnetic moments of all elements align almost wholly with the external magnetic field direction. This indicates that the core mechanism of the alloy’s “sluggish magnetic phase transition” is that, due to the different magnetic field thresholds required for the orientation of magnetic moments of the five elements, the magnetic moment orientation process progresses gradually with magnetic field and temperature, resulting in a wider temperature variation range. Meanwhile, it also explains that multiple rare-earth elements form the basis for large magnetic entropy changes and high RC.

Figure 3.

The schematic of the alloy’s magnetic moment orientation (a) Ion magnetic moments randomly oriented in zero magnetic field; (b) With increasing magnetic field, partial magnetic moments start to align; (c) Under high magnetic field, all magnetic moments align [87].

Wang et al. studied [88] quaternary rare-earth HEAs. The (GdTbDyHo)100−xScx HEAs (x = 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5 at%) all exhibited a single-phase HCP (space group P63/mmc). As Sc has a smaller atomic radius than the host rare-earth elements, the XRD diffraction peaks shifted gradually towards higher angles with increasing Sc content. Furthermore, the mixing enthalpy between Sc and Gd, Tb, Dy, and Ho was close to zero, preventing the formation of secondary phases. The TN of these alloys decreased from 198 K to 181 K with increasing Sc content. During cooling, a second-order phase transition from PM to AFM occurred, and below TN, a field-induced first-order transition from AFM to FM was observed. The inverse magnetic susceptibility curve above TN followed the Curie-Weiss law.

Under a 5 T, the maximum ΔSM value of the alloy ranged from 7.4 to 8.6 J·kg−1·K−1. When 0.3 at% SC was added, the magnetic entropy change curve had a full width at half-maximum of 108 K, and the RC reached 802.4 J·kg−1, which is nearly a 30% increase over the base GdTbDyHo alloy. The study used a temperature interval of ΔT = 10 K to calculate TEC. Under a 5 T magnetic field, the TEC(10) values for the (GdTbDyHo)100−xScx (x = 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5 at%) HEAs were 8.11, 7.61, 7.31, 7.19, 8.33, and 7.91 J·kg−1·K−1, respectively. TEC was more sensitive to magnetic field variation than ΔSM.

Table 1 shows the parameter comparison between the rare-earth high-entropy alloys (HEAs) introduced in this section and other typical magnetocaloric materials. For the Gd20Dy20Er20Ho20Tb20 HEA, its ΔSM value is 8.6 J·kg−1·K−1 and RC is 627 J·kg−1, which is higher than the ΔSM (7 J·kg−1·K−1) and RC (360 J·kg−1) of Gd5Si2Ge1.9Fe0.1 from the Gd-Si-Ge system, but lower than the ΔSM and RC of Gd5Si2Ge2 (ΔSM = 18.6 J·kg−1·K−1, RC = 306 J·kg−1). In contrast, the NiMn Heusler alloy Ni49Mn39Sb12 has a ΔSM of 5.21 J·kg−1·K−1, which is much lower than the Gd20Dy20Er20Ho20Tb20 HEA.

Table 1.

ΔSM, RC, and Other Properties of Materials, including Yield Strength (YS) and Plasticity (PL).

For pure Gd, Gd5Si2Ge2, LaFe11.5Si1.5, and MnFePSi system Mn0.95FeP0.5Si0.5, their ΔSM values are higher than that of the Gd20Dy20Er20Ho20Tb20 HEA, but they do not have an advantage in RC. The RC of Gd20Dy20Er20Ho20Tb20 HEA (627 J·kg−1) stands out in magnetocaloric materials. Additionally, the yield strength of the Gd20Dy20Er20Ho20Tb20 HEA is approximately 250 MPa, and its plastic strain exceeds 20%, showing an advantage in mechanical properties.

For the (GdTbDyHo)100−xScx alloy, as the Sc content increases, its ΔSm value varies between 7.4 and 8.6 J·kg−1·K−1. Its ΔSM is higher than that of Gd5Si2Ge1.9Fe0.1, but still lower than Gd5Si2Ge2. For pure Gd, Gd5Si2Ge2, LaFe11.5Si1.5, and MnFePSi system Mn0.95FeP0.5Si0.5, their ΔSM values are higher than those of the (GdTbDyHo)100−xScx alloy, but the RC value of (GdTbDyHo)100−xScx is much higher, reaching 802.4 J·kg−1, showing excellent cooling performance.

Table 2 presents the raw material costs and estimated sample costs for various alloys.

Table 2.

Material costs and estimated prices of samples.

The cost of each element is based on information provided by the Shanghai Metal Market (SMM), and the sample cost is estimated according to the atomic percentages of the elements in the alloy. For the rare-earth high-entropy alloy, the raw material cost of Gd20Dy20Er20Ho20Tb20 is approximately $264.6/kg, and that of GdTbDyHo is $319.0/kg. In comparison to Gd5Si2Ge2, which contains Ge (priced at $1662.6/kg), its raw material cost is similar to that of the rare-earth high-entropy alloys. Moreover, alloys with transition metals as the primary raw materials, such as Mn1.32Fe0.71P0.5Si0.56, have a much lower raw material cost of only $1.14/kg, which is lower than that of rare-earth high-entropy alloys.

In summary, rare-earth HEAs exhibit excellent magnetocaloric effects, providing large ΔSm and RC values. Additionally, the addition of rare-earth elements enhances the thermal stability of the alloys, making them suitable for high-temperature applications. Furthermore, the Gd20Dy20Er20Ho20Tb20 HEA also exhibits mechanical advantages, particularly in terms of yield strength and plastic strain, making it ideal for various applications. However, the high price of rare-earth elements results in higher overall costs for these alloys, which limits their widespread industrial use. Therefore, despite the significant performance advantages of rare-earth HEAs, their high cost may become a major factor determining their promotion and application.

4.2. Non-Rare Earth HEAs

Non-rare-earth magnetic HEAs are typically composed of various transition metal elements, without relying on rare-earth elements for their magnetic properties. By selecting compositions and ratios, adjusting lattice structures, regulating inter-element interactions, and optimizing preparation processes, large magnetic anisotropies and certain magnetocaloric effects are exhibited under specific magnetic field conditions. Research primarily classifies non-rare-earth magnetic HEAs into the following categories: transition metal-based HEAs, HEAs containing Ga and Ge elements, and other types of HEAs.

4.2.1. Transition Metal-Based HEAs

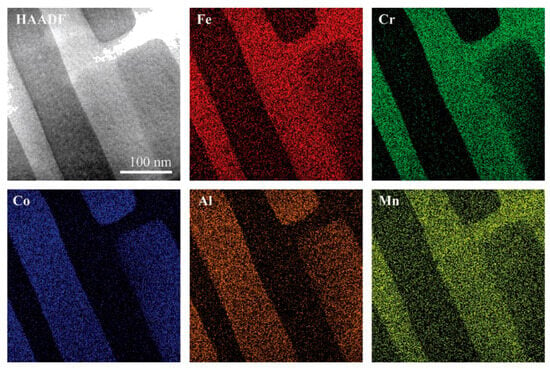

Transition metal-based HEAs, the most extensively studied type of HEAs, have been explored by researchers for their potential in magnetocaloric applications through composition tuning and process control. Jelen et al. [99] studied the single-crystal nanocomposite FeCoCrMnAl HEA, made by arc melting and directional solidification. The alloy consists of a chemically disordered bcc matrix (Fe28Co7Cr34Mn25Al6) and ordered B2 nanolayers (Fe14Co39Cr7Mn17Al23), with a nanolayer thickness of about 65 nm and coherent interfaces without grain boundaries. Figure 4 demonstrates the structural characteristics of HEA with a spinodally decomposed structure; the B2 nanolayers, rich in Al and Co, exhibit ferromagnetism, while the bcc matrix, primarily composed of Fe, Cr, and Mn, remains chemically disordered. The strong exchange coupling between the B2 nanolayers and the bcc matrix can lead the entire material to form a collective ferromagnetic state.

Figure 4.

TEM image and composition analysis of the HEA [99].

Magnetization tests showed that the alloy exhibited different magnetic behaviors at two different magnetic transition temperatures: the bcc matrix underwent a ferromagnetic-to-paramagnetic transition (Tc1) at 425 K. In contrast, the B2 nanolayers transitioned to ferromagnetic at 370 K (Tc2). As the temperature decreased, the coercivity (μ0Hc) increased from 0.5 mT at 300 K to 4.3 mT at 2 K. The AC susceptibility exhibited a peak at 425 K, shifting to higher values with increasing frequency. Below 200 K, the system maintained a stable ferromagnetic order, showing negative magnetoresistance above 200 K and positive below. The study confirms that in transition metal-based HEAs, the strong exchange coupling between the disordered bcc and the ordered B2 nanolayers causes the material to shift from a disordered magnetic state to a collective ferromagnetic state.

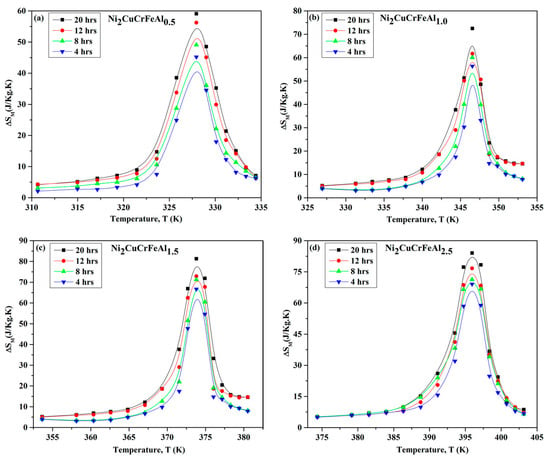

In terms of process performance tuning, C. Lav Kush et al. [100] prepared Ni2CuCrFeAlx (x = 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.5) HEAs via mechanical ball milling and sintering. The samples consisted of both FCC and BCC, with the proportion of the BCC increasing with the Al content. The alloys undergo an austenite-to-martensite phase transition between 384 and 490 K, accompanied by an L21→B2→A2 structural order-disorder transformation. The analysis of temperature-dependent magnetization reveals that all the alloys exhibit magnetic irreversibility, with the Ni2CuCrFeAl1.5 and Ni2CuCrFeAl2.5 alloys displaying the strongest irreversibility. The blocking temperature (Tb) is positively correlated with aluminum content, with Ni2CuCrFeAl2.5 exhibiting the highest Tb of 339.9 K. Alloys with higher aluminum content display stronger magnetic irreversibility, which is attributed to the presence of a spin-glass structure, resulting in superparamagnetic-like behavior at low temperatures. In the zero-field cooling mode, as the temperature decreases, the magnetization of each sample increases and reaches its maximum value at the critical temperature (Tc). In contrast, alloys with lower aluminum content show simpler magnetic fluctuations.

Figure 5 shows the temperature-dependent magnetization M(H) and ΔSM relationship of Ni2CuCrFeAlx HEAs with different milling times under a 10 kOe magnetic field. Table 3 lists the ΔSM values for different milling durations. The increase in milling time can enhance the ΔSM of Ni2CuCrFeAlx HEAs. For the low-aluminum-content Ni2CuCrFeAl0.5 HEA, the ΔSM value after 4 h of milling is 42.23 J·kg−1·K−1, while after 20 h of milling, it increases to 59.07 J·kg−1·K−1. For the high aluminum content Ni2CuCrFeAl2.5 HEA, the ΔSM value after 4 h of milling is 69.90 J·kg−1·K−1, and after 20 h of milling, it increases to 84.03 J·kg−1·K−1. The increase in aluminum content also improves the ΔSM. After 4 h of milling, the ΔSM of Ni2CuCrFeAl2.5 is 1.66 times higher than that of Ni2CuCrFeAl0.5. Similarly, after 20 h of milling, the ΔSM of Ni2CuCrFeAl2.5 is 1.42 times higher than that of Ni2CuCrFeAl0.5. Extended milling time and increased aluminum content enhanced the lattice disorder and strain in Ni2CuCrFeAlx alloys, resulting in higher entropy values and thus increasing ΔSM. It can be seen that changes in the alloy structure induced by processing conditions can affect the magnetic entropy change.

Figure 5.

M(H) and ΔSM relationship of Ni2CuCrFeAlx HEAs with different milling times under a 10 kOe magnetic field. (a) ΔNi2CuCrFeAl0.5 (b) Ni2CuCrFeAl (c) Ni2CuCrFeAl.5 (d) Ni2CuCrFeAl2.5 [100].

Table 3.

The ΔSM values for varying milling durations [100].

It is worth mentioning that the ΔSM values of Ni2CuCrFeAlx HEAs are significantly higher than the ΔSm values of the materials listed in Table 1. The research team did not compare this result with traditional magnetic materials, nor did it explain the significantly higher ΔSM. Further exploration of the mechanisms related to this phenomenon is still needed in future studies.

For FeCoCrMnAl HEA, the study does not provide its ΔSM, RC, or TEC data; however, it highlights that the material exhibits significant changes in magnetization over a large temperature range, from 425 K to 300 K, particularly in the vicinity of room temperature, demonstrating potential as a magnetocaloric material. Furthermore, based on Table 2, the estimated cost of the alloy is approximately $7.7/kg. Compared to rare-earth high-entropy alloy Gd20Dy20Er20Ho20Tb20 and traditional refrigerant materials like pure Gd and Gd5Si2Ge2, FeCoCrMnAl HEA offers a significant cost advantage. Further quantification of the specific magnetic effects of this alloy is necessary as a prerequisite for practical applications.

For Ni2CuCrFeAlx HEAs, the ΔSM is significantly higher than that of the materials listed in Table 1, with an estimated raw material cost of $8.7/kg (Ni2CuCrFeAl). However, the key mechanisms behind the enhancement of this magnetocaloric effect remain unclear and require further investigation.

4.2.2. HEAs Containing Ga and Ge Elements

Unlike the selection of elements to control mechanical properties, corrosion resistance, and high-temperature oxidation, researchers have chosen to add main-group elements such as Ga and Ge to regulate the magnetic properties of HEAs. Zheng et al. [101] optimized MnNiSi-based HEAs by adjusting the addition of FeCoGe and Ge elements. Table 4 shows the various parameters of the alloys. For (MnNiSi)1−xx(FeCoGe)x alloys, at x = 0.4, the ΔSM change under a 5 T reached 44.9 J·kg−1·K−1, exhibiting strong magnetocaloric effects. However, as x increased to 0.42, ΔSM change decreased to 29.2 J·kg−1·K−1, and further increases in x (x = 0.45, 0.47) caused a drop in the magnetic entropy change, down to 1.9 J·kg−1·K−1 and 2.4 J·kg−1·K−1. The Vickers hardness increased with the FeCoGe content, from 522.7 HV2 (x = 0.4) to 708.7 HV2 (x = 0.47), while the compressive strength decreased from 383 MPa (x = 0.4) to 267 MPa (x = 0.47). For (MnNi)0.6Si1−y(FeCo)0.4Gey alloys, ΔSM changed gradually and weakened as the Ge content increased (from y = 0.36 to 0.42). At y = 0.36, ΔSM change reached 55.3 J·kg−1·K−1, but decreased to 41.5 J·kg−1·K−1 at y = 0.42. The increase in Ge content also improved the mechanical properties, with a hardness of 580.6 HV2 and compressive strength of 267 MPa at y = 0.38.

Table 4.

ΔSM, RC, and Other Properties of Materials.

The study provides the mechanism by which Ge affects the properties of MnNiSi-based HEAs. Ge content influences the relationship between the structural transformation temperature and the Curie temperature, thereby affecting the strength of the magnetocaloric effect. Additionally, the addition of Ge alters the molar fraction of alloy elements, which in turn affects the configurational entropy. An appropriate amount of Ge helps promote phase transformation and enhances the ΔSM. At the same time, excessive configurational entropy stabilizes the single-phase structure and hinders phase transformation, causing a sharp decrease in ΔSM. At the same time, Ge modifies the electronic density and bond lengths of Mn and Fe, thereby indirectly regulating their magnetism and the total magnetic moment, which improves both the magnetocaloric effect and the mechanical properties. The study also confirmed that adjusting the Si/Ge ratio is possible to achieve a synergistic enhancement of both the magnetocaloric effect and mechanical properties.

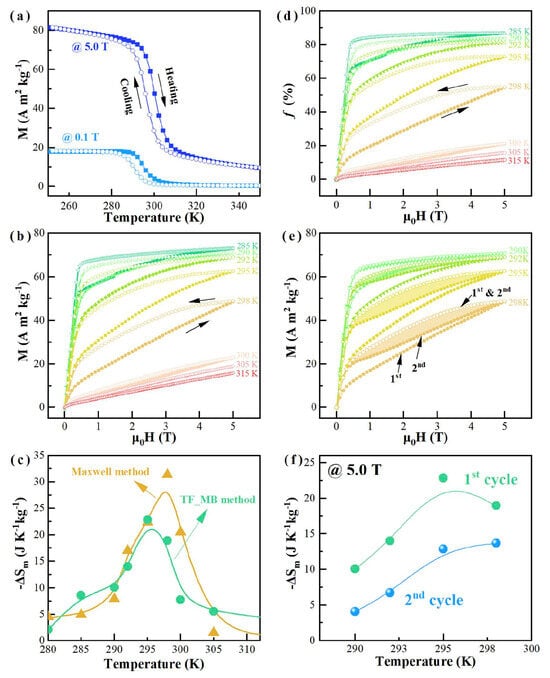

Guo et al. [102] proposed a design strategy for high-entropy magnetocaloric materials based on “configurational entropy control for single-phase transitions and element synergy for hysteresis regulation.” They designed a six-component MnFeCoNiGeSi HEA system, which demonstrated a heating and cooling hysteresis of only 4.3 K, lower than the 10–25 K observed in traditional MnMX alloys, indicating excellent phase transition reversibility and energy conversion efficiency. Figure 6 presents the magnetic behavior of Mn1.75Fe0.25CoNiGe1.6Si0.4 HEA. Figure 6a shows that as the magnetic field increases from 0.1 T to 5 T, the magnetization as a function of temperature shifts, with the magnetic structural transition temperature rising, indicating that the magnetic field can induce the transformation. The M-B curves in Figure 6b reveal apparent magnetic hysteresis near the transition temperature, suggesting a typical characteristic of a magnetic-field-induced first-order phase transition. The ΔSM calculated using the Maxwell relation is shown in Figure 6c, with a peak value of 31.37 J·kg−1·K−1 at 298 K under the 0–5 T field change. Figure 6d shows the ΔSM calculated by the TF_MB method, with a peak value of 22.83 J kg−1 K−1. Figure 6e displays the M-B curves of the second field cycle, where the magnetic hysteresis is smaller compared to the first cycle, indicating that the magnetic-field-induced magnetostructural transformation is partially reversible. Figure 6f shows the maximum reversible ΔSM, which peaks at 13.67 J·kg−1·K−1 at 298 K. Overall, the material exhibits magnetocaloric effects with partial reversibility in its magnetic transition.

Figure 6.

Magnetic behavior of Mn1.75Fe0.25CoNiGe1.6Si0.4 alloy (a) M-T lines at 0.1 T and 5 T; (b) Isothermal M-B lines; (c) The change in ΔSM under a 5 T field change, calculated using the Maxwell and the TF_MB method. (d) Orthorhombic phase mass fraction’s dependence; (e) Comparison of M-B curves in two cycles; (f) Magnetic entropy change calculated from the TF_MB method during two continuous magnetic cycles [102].

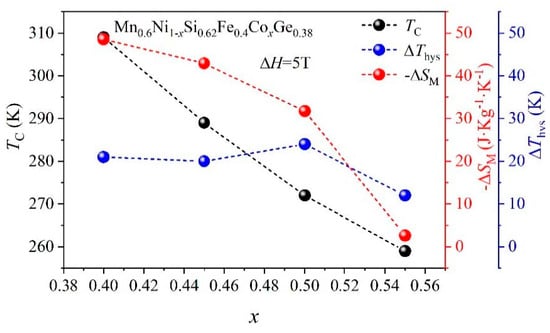

Zheng et al. [103] studied MnNiSi-based HEAs. The study showed that the Mn0.6Ni1−xSi0.62Fe0.4CoxGe0.38 (x = 0.4, 0.45, 0.5, 0.55) HEAs exhibited a Ni2In-type hexagonal structure (P63/mmc) at high temperatures, which transformed into a TiNiSi-type orthorhombic structure at low temperatures. The x = 0.4 alloy displayed a structural transition between the Ni2In-type and TiNiSi-type phases. As the Co content increased, the alloy’s structural stability improved, but the magnetocaloric effect gradually decreased. In terms of magnetocaloric performance, the x = 0.4 alloy exhibited a huge isothermal ΔSM of 48.5 J·kg−1·K−1 under a 5 T, indicating excellent magnetocaloric effects. Figure 7 illustrates the variations in Tc, ΔSM, and ΔThys in MnNiSi-based HEAs with varying Co doping levels. As the Co content increases, Tc gradually decreases from 309 K for x = 0.4 to 259 K for x = 0.55. At the same time, ΔSM decreases progressively, from 48.5 J·kg−1·K−1 for x = 0.4 to 2.6 J·kg−1·K−1 for x = 0.55. ΔThys also decreases with increasing Co content, from 21 K for x = 0.4 to 12 K for x = 0.55. These changes indicate that Co doping alters the order of the magnetic phase transition, weakening the MCE and making the phase transition smoother. The hardness and compressive strength of Mn0.6Ni1−xSi0.62Fe0.4CoxGe0.38 alloys with different Co-doping levels were investigated, showing an increase in hardness from 552 HV2 to 758 HV2 and in compressive strength from 78 MPa to 267 MPa as the Co content increased.

Figure 7.

The variation of Tc, ΔSM, and ΔThys for Mn0.6Ni1−xSi0.62Fe0.4CoxGe0.38 HEAs [103].

Sarlar’s team studied the structure and magnetocaloric properties of two high-entropy alloys: Fe26.7Ni26.7Ga15.6Mn20Si11 [104] and Fe30.7Ni25.7Ga14.6Mn19Si10 [105]. In the first alloy, the structure is BCC, with lattice constants of 2.878 Å, which decreased to 2.873 Å after annealing. Both as-cast and annealed samples showed soft magnetic properties with a saturation magnetization of 43 emu·g−1. The as-cast sample had ΔSM of 1.0 J·kg−1·K−1 and RC of 29.04 J·kg−1, while the annealed sample showed improved ΔSM of 1.59 J·kg−1·K−1 and RC of 75.68 J·kg−1, indicating enhanced magnetocaloric response.

In the second alloy, both quenched and annealed samples retained a stable body-centered cubic (bcc) structure. The annealed sample had a saturation magnetization of 72.6 emu·g−1 and a coercivity of 2 Oe. Tc increased from 442 K to 462 K with annealing, improving the magnetic exchange interactions. The ΔSM was 0.75 J·kg−1·K−1 for the quenched sample and 0.90 J·kg−1·K−1 for the annealed sample, with RC of 76.1 J·kg−1 and 178.4 J·kg−1. These results show that annealing optimizes the lattice and magnetic interactions, enhancing the magnetocaloric effect.

For (MnNi)0.6Si0.62(FeCo)0.4Ge0.38 HEAs, the ΔSm reaches 48.5 J·kg−1·K−1, which is significantly higher than the ΔSM values of the alloys listed in Table 1, approximately five times that of the pure Gd (ΔSM = 9.8 J·kg−1·K−1). The material also exhibits excellent mechanical properties, with a hardness of 580.6 HV0.2 and a compressive strength of 267 MPa. Considering the material cost, due to the inclusion of Ge ($1662.6/kg), the raw material cost of (MnNi)0.6Si0.62(FeCo)0.4Ge0.38 is estimated to be $321.0/kg, which is comparable to the cost of rare-earth HEAs. Given the high ΔSM of (MnNi)0.6Si0.62(FeCo)0.4Ge0.38 HEA, further investigation into the mechanism behind its enhanced magnetocaloric effect is required for potential practical applications.

The Mn1.75Fe0.25CoNiGe1.6Si0.4 HEA containing Ge exhibits a ΔSM of 22.83 J·kg−1·K−1, with a raw material cost of $449.85/kg. Its advantages and disadvantages are similar to those of the (MnNi)0.6Si0.62(FeCo)0.4Ge0.38 alloy. For the Fe26.7Ni26.7Ga15.6Mn20Si11 alloy, the estimated cost is $36.68/kg, which offers a cost advantage compared to HEAs containing Ge. Future research could focus on enhancing the ΔSM to improve the magnetocaloric performance further.

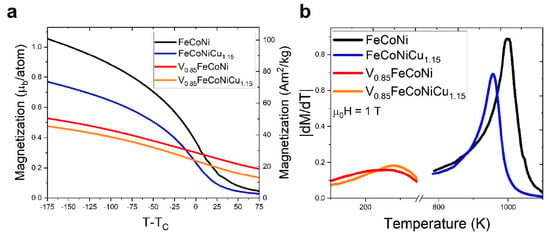

4.2.3. Other HEAs

To broaden the scope of magnetocaloric effect research in HEAs, researchers have started exploring more elemental combinations, including the introduction of high-melting-point elements and precious metals. Eggert et al. [106] studied the magnetic transition behavior and electronic structure mechanisms of V-Fe-Co-Ni-Cu-based HEAs. The study found that the FeCoNi parent alloy exhibited a single phase, with a Tc of 997 K, showing typical ferromagnetic characteristics. When the high-entropy element V was introduced, the V0.85FeCoNi alloy formed with approximately 21 at.% V, accompanied by the formation of the σ phase, resulting in a decrease of Tc to 245 K and a reduction in magnetization to 0.58 μB/atom, indicating that the chemical disorder and electronic localization effects introduced by high entropy weakened the ferromagnetic exchange. Further addition of Cu led to the formation of a FeCoNiCu1.15 alloy, with TC increasing to 957 K and magnetization rising to 1.16 μB/atom, thereby restoring some of the magnetic properties. Especially after the combined addition of V and Cu, the Tc of V0.85FeCoNiCu1.15 alloy increased to 278 K, and saturation magnetization increased to 0.54 μB/atom, broadening the magnetic transition range.

Figure 8 shows the relationship between magnetization and temperature, as well as the absolute derivative of magnetization for the four alloys in a 1 T. The FeCoNi alloy exhibits a typical second-order phase transition from ferromagnetic to paramagnetic behavior near its Curie temperature, characterized by a strong magnetocaloric effect. With the introduction of Cu, the magnetization slightly decreases, but the magnetic behavior remains stable. In contrast, the alloys containing V show changes, with a drastic reduction in magnetization and a broadening of the transition temperature, along with a notable decrease in the Curie temperature, indicating that the introduction of V negatively affects the magnetocaloric effect. The dM/dT curve shows that the FeCoNi alloy has a higher derivative value near its Curie temperature. At the same time, the addition of V significantly lowers dM/dT, further suppressing the magnetocaloric effect.

Figure 8.

Magnetic transition characteristics of FeCoNi-based high entropy alloys under a μ0H = 1 T. (a) Magnetization-temperature curve. (b) Absolute derivative of magnetization with respect to temperature curve [106].

Rocha et al. [107] studied CoCrxFeNiQy (Q = Pd, Cu, Au, Ag) HEAs. The results showed that all samples exhibited an FCC structure, with Pd and Cu forming solid solutions. At the same time, Au and Ag remained as unalloyed phases at lower concentrations—the Curie temperatures of CoCr0.75FeNiPd0.2, CoCr0.9FeNiPd0.4, and CoCr1.05FeNiPd0.6 were 347 K, 310 K, and 284 K, respectively, which decreased to 329 K, 273 K, and 261 K after annealing. As the Cr increased, the Curie temperature decreased, and as the Pd increased, the lattice constant increased from 3.60 Å to 3.64 Å, strengthening the exchange interaction and slightly raising Tc. The CoCr0.75FeNiCu0.3 exhibited a single-phase structure, while a two-phase structure appeared when Cu content reached 16%, with a Tc of 378 K. In gold-silver alloys, CoCr0.9FeNiAu0.3 and CoCr0.9FeNiAg0.2 had Tc of 341 K and 209 K, which decreased to 330 K and 295 K after annealing. The doping of different elements had a significant effect on magnetic control: Cr’s antiferromagnetic properties lowered the Tc, while larger atomic radius elements, such as Pd and Cu, enhanced exchange interactions through lattice expansion. ΔSM ranged from 0.11 to 0.64 J·kg−1·K−1, and the maximum RCP was about 18 J·kg−1. The study indicated that lattice distortion and magnetic exchange coupling, caused by Q element doping, are key mechanisms for controlling magnetism and the Curie temperature.

4.3. Transition Metal and Rare-Earth Composite HEAs

By combining transition metal elements with rare-earth elements, the synergistic effect of these two types of elements can be utilized to achieve alloy performance tuning. This approach has become a significant direction in recent research on magnetic HEAs. Zhang et al. [38] studied the five-element Er20Ho20Gd20Ni20Co20 HEA, showing that the alloy exhibited a fully amorphous structure. The glass transition temperature (Tg) of the alloy was 510 K, the crystallization temperature (Tx) was 582 K, and the supercooled liquid region width (ΔTx) was 72 K. The alloy reached a ΔSM of 17.84 J·kg−1·K−1 in a 0–7 T, and 13.73 J·kg−1·K−1 in a 0–5 T. The hysteresis width was approximately 70.1 K, and RC reached 1030 J·kg−1 within the 0–7 T range, with negligible hysteresis loss. In the 0–5 T range, RC was 759 J·kg−1. All results are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

ΔSM, RC, and Other Properties of transition metal and rare-earth composite HEAs.

The study indicates that the enhancement of the material’s magnetocaloric effect is closely related to its magnetic field-dependent second-order magnetic phase transition. When the external magnetic field changes, the material’s magnetism gradually transitions from FM to PM, and this transition is relatively smooth, which helps improve the material’s temperature regulation ability. Additionally, the complex magnetic interactions between the rare-earth elements (Er, Ho, Gd) and transition metal elements (Ni, Co) play a crucial role. The interaction between the f-orbitals of the rare-earth elements and the d-orbitals of the transition metals forms a unique magnetic coupling, which enables the material to exhibit a more stable and continuous magnetic transition in response to external magnetic field changes, thereby further enhancing the magnetocaloric effect.

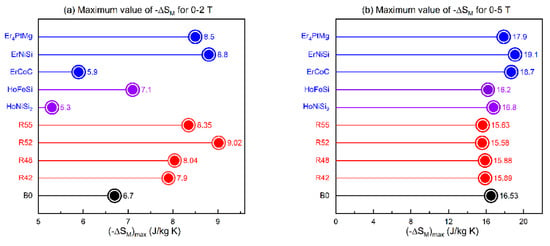

Pan et al. [108] studied the Er2Tm2Al4CuNiGa HEAs under the influence of amorphization engineering. They used vacuum arc melting to prepare the polycrystalline bulk sample B0 and melt-spinning technology to fabricate the amorphous ribbon samples R42, R48, R52, and R55. The copper wheel linear velocities for these samples were 42 m/s, 48 m/s, 52 m/s, and 55 m/s, respectively, to control the degree of amorphization by adjusting the linear velocity. The results showed that amorphization significantly altered the magnetic properties of the material, notably reducing Tc from 4.5 K for the B0 to 3.0 K for the amorphous ribbon sample R52. This reduction in Tc indicated that amorphization weakened long-range magnetic order and adjusted the magnetic phase transition temperature range. All samples underwent an FM-to-PM transition as the temperature increased. The amorphous ribbon samples exhibited lower Tc and better thermal reversibility, with R52 showing a Tc of 3.0 K, lower than B0′s 4.5 K.

Additionally, the ΔSM of the amorphous samples was enhanced at low magnetic fields. The ΔSM increased from 2.7/6.7 J·kg−1·K−1 (0–1/0–2 T) for the bulk to 4.3/9.0 J·kg−1·K−1 for the amorphous ribbons, showing a 59% and 34% improvement, respectively. The ΔSM of the amorphous ribbons remained high (15.6 J·kg−1·K−1) at high fields (0–5 T). The magnetic phase transition of the amorphous samples was second-order, exhibiting excellent magnetic thermal reversibility and low hysteresis. The results are shown in Table 5.

Figure 9 compares the MCE of Er2Tm2Al4CuNiGa amorphous ribbon samples with typical rare-earth intermetallic compounds, such as Ho-NiSi2 and ErNiSi. Figure 9a shows the magnetic entropy change under low-field variations (0–2 T), where the Er2Tm2Al4CuNiGa amorphous ribbon samples exhibit excellent performance, surpassing some typical rare-earth intermetallic compounds. Figure 9b displays the ΔSM under high-field variations (0–5 T), where the amorphous ribbon samples show slightly lower performance compared to other materials.

Figure 9.

Comparison of maximum ΔSM for Er2Tm2Al4CuNiGa ribbons, bulk, and low-temperature MCE materials. (a) 0–2 T (b) 0–5 T [108].

Additionally, Wang et al. [109] studied the MCE of GdErHoCoM (M = Cr and Mn) rare-earth HEAs. The results showed that under a 5 T field, the ΔSM of GdErHoCoCr and GdErHoCoMn alloys were 12.29 J/(kg·K) and 10.13 J/(kg·K), respectively, with RCPs of 746 J/kg and 606 J/kg, demonstrating excellent MCE performance and potential for commercial applications. Lei et al. [110] studied the Gd20Dy20Er20Al20Co20 amorphous alloy. They found that its ΔSM under a 5 T was 9.59 J/(kg·K) with an RCP of 613 J/kg, indicating its potential for low-temperature refrigeration applications. Wei et al. [111] prepared Sm20Gd20Dy20Co20Al20 alloy fibers using solvent extraction and drawing processes. Under a 5 T, theΔSM was 6.34 J/(kg·K) with an RCP of 422.09 J/kg.

For the Er20Ho20Gd20Ni20Co20 HEA, ΔSM reaches 13.7 J·kg−1·K−1, which is higher than that of pure Gd and LaFe11.5Si1.5 alloys. The RC is 759 J/kg, surpassing most of the compounds listed in Table 1. The raw material cost is approximately $32.32/kg, which is lower than that of the fully rare-earth Gd20Dy20Er20Ho20Tb20 HEA ($264.60/kg) by incorporating transition metals such as Ni and Co, thereby reducing the overall cost.

For the Er2Tm2Al4CuNiGa alloy, the optimal process yields a ΔSM of 16.5 J·kg−1·K−1, with an estimated cost of $63.26/kg. This shows that for transition metal and rare-earth composite HEAs, a rational combination of rare-earth elements and transition metals can balance performance and cost. With further research and optimization, these materials are expected to demonstrate practical application value in fields that require high cooling performance and are relatively less sensitive to cost.

5. Summary and Outlook

This article reviews the progress of HEAs in the field of MCE and summarizes the key findings of the current research. In the case of rare-earth HEAs, the unique 4f electronic configuration of rare-earth elements enables them to form strong magnetic moments. The multi-element design enhances configurational entropy, forming disordered solid solutions that allow for performance tuning. For example, Gd18Dy18Er18Ho18Tb18 HEA exhibits a ΔSM of 8.6 J·kg−1·K−1 and an RC of 627 J·kg−1, while also demonstrating excellent mechanical properties with YS > 250 MPa and PL > 20%. This makes it highly competitive compared to traditional magnetocaloric materials.

Transition metal-based high-entropy alloys mainly rely on elements such as Fe, Co, and Ni, which offer a lower material cost compared to rare-earth high-entropy alloys. By optimizing the composition and phase structure, these alloys can also exhibit significant magnetocaloric effects. For example, Ni2CuCrFeAl0.5 achieves a ΔSm of 42.23 J·kg−1·K−1. The addition of elements like Ge and Ga can strike a good balance between magnetocaloric and mechanical properties. (MnNi)0.6Si0.62(FeCo)0.4Ge0.38 HEA achieves a ΔSM of 48.5 J·kg−1·K−1, with a hardness of 552 HV0.2 and a CS of 78 MPa. By selecting and optimizing the elemental composition, HEAs can be tailored for specific cooling applications, achieving a reasonable balance between cost and performance.

Furthermore, composite HEAs that combine transition metals and rare-earth elements have also shown excellent magnetocaloric effects. For instance, the Er20Ho20Gd20Ni20Co20 five-element rare-earth HEA demonstrated a magnetic entropy change of 17.84 J·kg−1·K−1 and a refrigeration capacity of up to 1030 J·kg−1 under an external magnetic field. The addition of transition metals such as Ni and Co not only enhances the magnetocaloric performance of the alloy but also reduces the overall cost compared to fully rare-earth HEAs. This makes transition metal and rare-earth composite HEAs more promising for commercial and industrial applications.

Despite the progress in HEAs’ magnetocaloric effects, several challenges remain. Future research should focus on the following aspects:

- Further optimization of alloy composition and design.

The multi-element design of HEAs offers considerable flexibility for tailoring properties. Future research can further optimize alloy compositions, ratios, and types of elements to enhance the strength of their magnetocaloric effects. In particular, in the design of non-rare-earth HEAs, introducing more magnetic elements or innovative alloy combinations will not only improve their magnetocaloric effects and thermal response but also help reduce material costs, making them more economical for broader applications.

- 2.

- Improving stability and cyclic performance.

The stability and cyclic performance of HEAs under long-term variations in magnetic fields remain a bottleneck in current research. Solving issues such as magnetic hysteresis losses, improving long-term stability in real-world working environments, and maintaining performance under high-frequency cycles and magnetic field variations will be key to improving the practical applicability of these materials.

- 3.

- Promoting industrial applications and reducing costs.

Although HEAs have demonstrated magnetocaloric effects in the laboratory, their high cost and complex production processes limit their commercialization. Future research should focus on reducing production costs, improving processability, and enhancing the stability of HEAs in real-world environments. This will help drive the application of HEAs in magnetic refrigeration technologies, energy storage, and other high-performance functional materials.

- 4.

- In-depth research combining theory and experiments.

Although theoretical models have been established, the mechanisms of magnetocaloric effects in HEAs remain unclear, particularly regarding phase transition behaviors and the regulation of magnetic properties in complex alloy systems. Future research can combine more first-principles calculations with experimental data to explore the intrinsic mechanisms of HEAs, particularly in optimizing magnetocaloric effects through multi-element synergistic interactions, thereby providing theoretical support for alloy design.

In conclusion, with a deeper understanding of the mechanisms behind the magnetocaloric effects in HEAs, these materials are expected to find widespread applications in magnetic refrigeration and other functional material fields, offering innovative solutions for green, low-energy refrigeration technologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L.; methodology, Y.L.; validation, Z.G.; formal analysis, Z.G.; investigation, Y.L. and X.Z.; resources, Y.L.; data curation, F.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Z.; writing—review and editing, X.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Research Project of the Scientific Research and Industry Department, Jilin Provincial Department of Education (Grant No. JJKH20241129KJ). 2024 Anhui Provincial University Scientific Research Project (Natural Science Category, Key Project, No. 2024AH052003); 2024 Provincial Department of Education Science and Engineering Teachers’ Internship Program in Enterprises (No. 2024jsqygz76).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ajay, P.; Dabhade, V.V. Heat treatments of Inconel 718 nickel-based superalloy: A review. Met. Mater. Int. 2025, 31, 1204–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, J.W.; Chen, S.K.; Lin, S.J.; Gan, J.Y.; Chin, T.S.; Shun, T.T.; Tsau, C.H.; Chang, S.-Y. Nanostructured high-entropy alloys with multiple principal elements: Novel alloy design concepts and outcomes. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2004, 6, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, B.; Chang, I.T.H.; Knight, P.; Vincent, A.J.B. Microstructural development in equiatomic multicomponent alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2004, 375–377, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Zhao, S.; Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Guo, E. Effect of annealing temperature on the microstructure and mechanical properties of CoCrFeNiNb0.2Mo0.2 high entropy alloy. Materials 2023, 16, 3987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufanets, M.; Sklyarchuk, V.; Plevachuk, Y.; Kulyk, Y.; Mudry, S. The structural and thermodynamic analysis of phase formation processes in equiatomic AlCoCuFeNiCr high-entropy alloys. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2020, 29, 7321–7327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Bai, S.; Chong, K.; Liu, C.; Cao, Y.; Zou, Y. Machine learning accelerated design of non-equiatomic refractory high entropy alloys based on first principles calculation. Vacuum 2023, 207, 111608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.J.; Won, Y.J.; Cho, K.S. Thermodynamic evaluation of the phase stability in mechanically alloyed AlCuxNiCoTi high-entropy alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 948, 169772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, U.S.; Hung, U.D.; Yeh, J.W.; Chen, S.K.; Huang, Y.S.; Yang, C.C. Alloying behavior of iron, gold and silver in AlCoCrCuNi-based equimolar high-entropy alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2007, 460–461, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Qin, G.; Yang, X.; Ren, H.; Chen, R. Influence of aging heat treatment on the microstructure and mechanical properties of Co29Cr31Cu4Mn15Ni21 high-entropy alloys strengthened by nano-precipitates. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2025, 920, 147508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, H.; Li, X. Architecture design and strengthening-toughening mechanisms in heterogeneous-structured medium/high entropy alloys. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2024, 69, 3864–3886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yang, W.; Lin, S.; Liu, C.; Qin, J.; Qu, P.; Zhang, J.; Liu, L. A novel L12-strengthened single crystal high entropy alloy with excellent high-temperature mechanical properties. Mater. Charact. 2024, 212, 113958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.X.; Kang, K.W.; Yu, S.B.; Zhang, J.S.; Xu, M.K.; Huang, D.; Che, C.N.; Liu, S.K.; Jiang, Y.T.; Li, G. Heterogeneous structure and dual precipitates induced excellent strength-ductility combination in CoCrNiTi0.1 medium entropy alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 912, 146992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Q.; Yang, G.; Xu, M.; Xu, W.; Tang, C.; Yi, J. An excellent synergy in yield strength and plasticity of NbTiZrTa0.25Cr0.4 refractory high entropy alloy through the regulation of cooling rates. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2023, 117, 106409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Huang, Y.; Sun, J.; Lu, Y. The relationship between thermo-mechanical history, microstructure and mechanical properties in additively manufactured CoCrFeMnNi high entropy alloy. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 77, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Guo, E.; Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Zhao, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Cui, B. Multi-scale microstructure strengthening strategy in CoCrFeNiNb0.1Mo0.3 high entropy alloy overcoming strength-ductility trade-off. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 882, 145446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Rao, Y.; Liu, C.; Xie, X.; Yu, D.; Chen, Y.; Ghazisaeidi, M.; Ungar, T.; Wang, H.; An, K.; et al. Enhancing fatigue life by ductile-transformable multicomponent B2 precipitates in a high-entropy alloy. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xue, J.; Lin, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, D.; Liu, J.; Zhang, G.; Jiang, H.; et al. The Mo-14Re alloy, a promising candidate material for bioresorbable vascular scaffolds. Acta Biomater. 2025, 204, 657–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, M.; Mohd Najib, A.S.; Fadil, N.A.; Abu Bakar, T.A. Microstructure and phase chemistry of vacuum induction melting fabricated-equimolar AlCoCrFeNi HEA during spinodal dissolution annealing. Int. J. Integr. Eng. 2024, 16, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajilou, N.; Javaheri, M.; Ebadzadeh, T.; Farvizi, M. Investigation of the electrochemical behavior of AlCoCrFeNi–ZrO2 high entropy alloy composites prepared with mechanical alloying and spark plasma sintering. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2024, 54, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da, Q.; Kang, J.; Ma, G.; Zhou, Y.; Fu, Z.; Zhu, L.; She, D.; Wang, H. Research on microstructure, mechanical property and wear mechanism of AlCoCrFeNi/WC composite coating fabricated by HVOF. Tribol. Int. 2024, 200, 110149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charkhchian, J.; Zarei-Hanzaki, A.; Schwarz, T.M.; Lawitzki, R.; Schmitz, G.; Schell, N.; Shen, J.; Oliveira, J.P.; Waryoba, D.; Abedi, H.R. Unleashing the microstructural evolutions during hot deformation of as-cast AlCoCrFeNi2.1 eutectic high entropy alloy. Intermetallics 2024, 168, 108253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemanate, A.M.; Jorge Júnior, A.M.; Andreani, G.F.D.L.; Roche, V.; Cardoso, K.R. Corrosion behavior of AlCoCrFeNix high entropy alloys. Electrochim. Acta 2023, 441, 141844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Zhao, W.; Li, Z.; Guo, N.; Xiao, G.; Zhang, H. High-temperature oxidation behavior and corrosion resistance of in-situ TiC and Mo reinforced AlCoCrFeNi-based high entropy alloy coatings by laser cladding. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 10151–10164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Choi, Y.T.; Yang, J.; He, J.; Zeng, Z.; Zhou, N.; Baptista, A.C.; Kim, H.S.; Oliveira, J.P. Fabrication of spatially-variable heterostructured CoCrFeMnNi high entropy alloy by laser processing. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 896, 146272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Han, Y.; Li, H.-B.; Tian, Y.-Z.; Zhu, H.-C.; Jiang, Z.-H.; He, T.; Zhou, G. Enhancement in impact toughness of CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloy via nitrogen addition. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 932, 167615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Gonçalves, R.; Choi, Y.T.; Lopes, J.G.; Yang, J.; Schell, N.; Kim, H.S.; Oliveira, J.P. Microstructure and mechanical properties of gas metal arc welded CoCrFeMnNi joints using a 410 stainless steel filler metal. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 857, 144025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangguan, Z.; Ma, S.; Li, J.; Liu, P.; Wang, Z. Study on high-temperature oxidation of TiZrHfNbTaV high-entropy alloy. Mater. Lett. 2024, 360, 135907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wu, M.; Shu, D.; Zhu, G.; Wang, D.; Sun, B. Mechanical instability and tensile properties of TiZrHfNbTa high entropy alloy at cryogenic temperatures. Acta Mater. 2020, 201, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yu, Q.; Tang, Y.T.; Xu, M.; Wang, H.; Zhu, C.; Ell, J.; Zhao, S.; MacDonald, B.E.; Cao, P.; et al. Strong and ductile FeNiCoAl-based high-entropy alloys for cryogenic to elevated temperature multifunctional applications. Acta Mater. 2023, 242, 118449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Dong, H.; Sun, W.; Lv, L.; Yang, C.; Xiao, Y.; Wu, F.; Wang, Y.; et al. Progress and perspective of high-entropy strategy applied in layered transition metal oxide cathode materials for high-energy and long cycle life sodium-ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2417258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, M.; Jiang, M.; Gao, L.; Ma, Z.; Cao, M. High entropy ceramics for electromagnetic functional materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2416673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Miao, X.; Van Dijk, N.; Brück, E.; Ren, Y. Advanced magnetocaloric materials for energy conversion: Recent progress, opportunities, and perspective. Adv. Energy Mater. 2024, 14, 2400369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, V.; Blázquez, J.S.; Ipus, J.J.; Law, J.Y.; Moreno-Ramírez, L.M.; Conde, A. Magnetocaloric effect: From materials research to refrigeration devices. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2018, 93, 112–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.-Y.; Han, Y.-Q.; Cheng, J.; Gao, L.; Jin, X.; Sun, Z.-B.; Huang, J.-H. Effect of Al doping on magnetocaloric effect and mechanical properties of La(FeSi)13-based alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 990, 174398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarkevich, N.A.; Zverev, V.I. Viable materials with a giant magnetocaloric effect. Crystals 2020, 10, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.-Q.; Shen, J.; Hu, F.-X.; Sun, J.-R.; Shen, B.-G. Research progress in magnetocaloric effect materials. Acta Phys. Sin. 2016, 65, 217502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheibel, F.; Gottschall, T.; Taubel, A.; Fries, M.; Skokov, K.P.; Terwey, A.; Keune, W.; Ollefs, K.; Wende, H.; Farle, M.; et al. Hysteresis design of magnetocaloric materials—From basic mechanisms to applications. Energy Technol. 2018, 6, 1397–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Li, S.; Wang, J.; Ren, Z. Achievement of giant cryogenic refrigerant capacity in quinary rare-earths based high-entropy amorphous alloy. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 102, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.-W. Review of magnetic properties and magnetocaloric effect in the intermetallic compounds of rare earth with low boiling point metals. Chin. Phys. B 2016, 25, 37502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Review of the structural, magnetic and magnetocaloric properties in ternary rare earth RE2T2X type intermetallic compounds. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 787, 1173–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Man, J.; Wang, Q.; Liu, G.; Xiao, S.; Dong, N. Effect of nano WC on wear and corrosion resistances of CoCrFeNiTi high entropy alloy coating. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025, 34, 1078–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Liang, H.; Li, Y. Effect of Si content on phase structure, microstructure, and corrosion resistance of FeCrNiAl0.7Cu0.3Six high-entropy alloys in 3.5% NaCl solution. Coatings 2025, 15, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.K.; Shahi, R.R.; Singh, A.R.; Sahay, P.P. Synthesis, characterizations, and magnetic properties of FeCoNiTi-based high-entropy alloys. Emergent Mater. 2020, 3, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, J.Y.; Franco, V. Review on magnetocaloric high-entropy alloys: Design and analysis methods. J. Mater. Res. 2023, 38, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, B. Multicomponent and high entropy alloys. Entropy 2014, 16, 4749–4768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, R.; Li, Y. Influence of Si content on the microstructure, wear resistance, and corrosion resistance of FeCoNiCrAl0.7Cu0.3Six high entropy alloy. Coatings 2024, 14, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shi, Y.; Lin, H.; Ji, X. Corrosion behavior of as-cladding Al0.8CrFeCoNiCu0.5Six high entropy alloys in 3.5% NaCl solution. Mater. Res. 2024, 27, e20230221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Zhang, J.; Fu, H.; Xiong, Y.; Ma, S.; Xiang, X.; Xu, B.; Lu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Weber, W.J.; et al. Irradiation performance of high entropy ceramics: A comprehensive comparison with conventional ceramics and high entropy alloys. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2024, 143, 101250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALMisned, G.; Güler, Ö.; Özkul, İ.; Sen Baykal, D.; Alkarrani, H.; Kilic, G.; Mesbahi, A.; Tekin, H.O. Exploring thermodynamic, physical and radiative interaction properties of quinary FeNiCoCr high entropy alloys (HEAs): A multi-directional characterization study. Phys. Scr. 2024, 99, 115303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhao, Q.; Zhan, Z.; Liu, J.; Liao, X.; Deng, J.; Wei, L.; Li, X. Effect of Al addition on the corrosion behavior of Al CoCrFeNi high entropy alloys in supercritical water. Corros. Sci. 2023, 216, 111089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-T.; Liu, S.-W.; Zheng, H.-L.; Huang, W.-J.; Zhao, W.; Liao, W.-B. Effects of transient thermal shock on the microstructure and mechanical properties of CoCrFeNiMn high-entropy alloy coatings. Front. Mater. 2021, 8, 805296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, M.; Wang, X.; Wang, T.; Li, T.; Lu, Y. A novel Co-free high-entropy alloy with excellent antimicrobial and mechanical properties. Rare Met. 2025, 44, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizenshtein, M.; Ungarish, Z.; Woller, K.B.; Hayun, S.; Short, M.P. Mechanical and microstructural response of the Al0.5CoCrFeNi high entropy alloy to Si and Ni ion irradiation. Nucl. Mater. Energy 2020, 25, 100813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Qiao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, T.-W.; Li, T.; Wang, H.-Y.; Dai, L.-H. A high-entropy alloy syntactic foam with exceptional cryogenic and dynamic properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 876, 145146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusenko, K.V.; Riva, S.; Crichton, W.A.; Spektor, K.; Bykova, E.; Pakhomova, A.; Tudball, A.; Kupenko, I.; Rohrbach, A.; Klemme, S.; et al. High-pressure high-temperature tailoring of high entropy alloys for extreme environments. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 738, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonal, S.; Lee, J. Recent advances in additive manufacturing of high entropy alloys and their nuclear and wear-resistant applications. Metals 2021, 11, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Inoue, A.; Wang, F.; Chang, C. The influence of boron and carbon addition on the glass formation and mechanical properties of high entropy (Fe, Co, Ni, Cr, Mo)-(B, C) glassy alloys. Coatings 2024, 14, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sfikas, A.K.; Kamnis, S.; Tse, M.C.H.; Christofidou, K.A.; Gonzalez, S.; Karantzalis, A.E.; Georgatis, E. Microstructural evaluation of thermal-sprayed CoCrFeMnNi0.8V high-entropy alloy coatings. Coatings 2023, 13, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Li, R.; Lei, Z. Influences of synthetic parameters on morphology and growth of high entropy oxide nanotube arrays. Coatings 2022, 13, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ni, X.; Tian, F. Ab initio predicted alloying effects on the elastic properties of AlxHf1−xNbTaTiZr high entropy alloys. Coatings 2015, 5, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, K.; Zhang, Y. High-entropy alloy films. Coatings 2023, 13, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Liu, C.T. Phase stability in high entropy alloys: Formation of solid-solution phase or amorphous phase. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2011, 21, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaladurgam, N.R.; Lozinko, A.; Guo, S.; Harjo, S.; Colliander, M.H. Load redistribution in eutectic high entropy alloy AlCoCrFeNi2.1 during high temperature deformation. Materialia 2022, 22, 101392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Lü, S.; Wu, S.; Chen, X.; Guo, W. Development of MoNbVTax refractory high entropy alloy with high strength at elevated temperature. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 850, 143554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, D.; Jiang, W.; Wang, X.; Ma, T.; Zhu, D.; Wang, Y.; Huo, J. Enhanced mechanical properties of high pressure solidified CoCrFeNiMo0.3 high entropy alloy via nano-precipitated phase. Intermetallics 2024, 166, 108192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Ren, Y.; Sun, D.; Wang, B.; Wu, H.; Bian, H.; Cao, J.; Cao, X.; Ding, F.; Lu, J.; et al. High entropy alloy nanoparticles dual-decorated with nitrogen-doped carbon and carbon nanotubes as promising electrocatalysts for lithium–sulfur batteries. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 188, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, T.Z.; Wilkerson, R.P.; Musicó, B.L.; Foley, A.; Brahlek, M.; Weber, W.J.; Sickafus, K.E.; Mazza, A.R. High entropy ceramics for applications in extreme environments. J. Phys. Mater. 2024, 7, 21001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Hua, K.; Cao, Y.; Song, Y.; Li, X.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, H. Microstructures and properties of FeCrAlMoSi high entropy alloy coatings prepared by laser cladding on a titanium alloy substrate. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 478, 130437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Kruk, R.; Hahn, H. Magnetic properties of high entropy oxides. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 1973–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Wen, Z.; Ma, B.; Wu, Z.; Yu, J.; Tang, L.; Lu, T.; Zhao, Y. Effect of A-site rare-earth ions on structure and magnetic properties of novel (Ln0.2Gd0.2La0.2Nd0.2Sm0.2)MnO3 (Ln = Eu, Ho, Yb) high-entropy perovskite ceramics. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 26040–26048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, P.; Kiran Kumar Yadav Nartu, M.S. Additive manufacturing of soft magnetic high entropy alloys: A review. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2025, 627, 173148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhong, Z.; Liang, Z.; Wang, S.; Du, Y.; Yan, C. High-entropy rare earth materials: Synthesis, application and outlook. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 2211–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, P.; Gupta, A.K.; Mishra, R.K.; Ahmad, M.S.; Shahi, R.R. A comprehensive review: Recent progress on magnetic high entropy alloys and oxides. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2022, 554, 169142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.C.; Miracle, D.B.; Maurice, D.; Yan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Hawk, J.A. High-entropy functional materials. J. Mater. Res. 2018, 33, 3138–3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yayla, N.; Güler, Ö. A short review of structural, mechanical and magnetic properties of high and medium entropy alloys added rare earth elements. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 47, 113264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Gong, M.; Zhang, D.; Sun, W.; Liu, F.; Bai, J.; Gao, Q.; Zhao, X. Effect of heat treatment time on the microstructure and properties of FeCoNiCuTi high-entropy alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 4510–4516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, A.; Eivani, A.R.; Abbasi, S.M.; Jafarian, H.R.; Ghosh, M.; Anijdan, S.H.M. Al-Co-Cr-Fe-Ni-Ti high entropy alloys: A review of microstructural and mechanical properties at elevated temperatures. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 178216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, M.; Qu, H.; Xu, C.; Guo, W.; Wang, K.; Liu, F.; Bai, J.; Gao, Q.; Zhao, X.; Li, S. Effect of heat treatment temperature on microstructure and properties of FeCoNiCuTi high–entropy alloy. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2022, 75, 1951–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, H.; Li, K.; Shi, L.; Zhao, W.; Bu, H.; Gong, P.; Yao, K.-F. Recent progress in high-entropy metallic glasses. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 161, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shi, Y. Microhardness, wear resistance, and corrosion resistance of AlxCrFeCoNiCu high-entropy alloy coatings on aluminum by laser cladding. Opt. Laser Technol. 2021, 134, 106632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, W.-L.; Tsai, C.-W.; Yeh, A.-C.; Yeh, J.-W. Clarifying the four core effects of high-entropy materials. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2024, 8, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, W.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, C.; Liu, H.; Qiu, H.; Cheng, X. Effect of volumetric energy density on the mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of laser-additive-manufactured AlCoCrFeNi2.1 high-entropy alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 178032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Zhang, Q.; Yao, K. Composition design strategy for high entropy amorphous alloys. Materials 2024, 17, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fruhling, K.; Yao, X.; Streeter, A.; Tafti, F. Characterization of the magnetocaloric effect in RMn6Sn6 including high-entropy forms. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024, 319, 129230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirayama, Y.; Nakagawa, T.; Kusunose, T.; Yamamoto, T.A. Magnetocaloric effect of rare earth nitrides. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2008, 44, 2997–3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Shen, B.G.; Li, D.X.; Gao, Z.X. New magnetic refrigeration materials for temperature range from 165 K to 235 K. J. Alloys Compd. 2000, 311, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Wu, Y.; Tong, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Liu, X.J.; Ma, L.; Suo, H.L.; Lu, Z.P. Rare-earth high-entropy alloys with giant magnetocaloric effect. Acta Mater. 2017, 125, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, R.; Jiang, S.; Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Ma, D.; Lu, Z. Effect of Sc addition on magnetocaloric properties of GdTbDyHo high-entropy alloys. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2024, 26, 2300616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.V. Magnetic heat pumping near room temperature. J. Appl. Phys. 1976, 47, 3673–3680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecharsky, V.K.; Gschneidner, K.A., Jr. Giant magnetocaloric effect in Gd5(Si2Ge2). Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 78, 4494–4497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provenzano, V.; Shapiro, A.J.; Shull, R.D. Reduction of hysteresis losses in the magnetic refrigerant Gd5Ge2Si2 by the addition of iron. Nature 2004, 429, 853–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, L.; Hui, X.; Wu, Y.; Chen, G.L. Large magnetocaloric effect in Gd36Y20Al24Co20 bulk metallic glass. J. Alloys Compd. 2008, 457, 541–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Liu, C.; Lu, W.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, W.; Nie, X.; Sang, X.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, Q. Effect of Gd doping on the microstructure and magnetocaloric properties of LaFe11.5Si1.5 alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 910, 164858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fries, M.; Pfeuffer, L.; Bruder, E.; Gottschall, T.; Ener, S.; Diop, L.V.B.; Gröb, T.; Skokov, K.P.; Gutfleisch, O. Microstructural and magnetic properties of Mn-Fe-P-Si (Fe2P-type) magnetocaloric compounds. Acta Mater. 2017, 132, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.F.; Ma, Y.Y.; Tan, X. Structural and magnetic properties of Mn1.25Fe0.7P0.5Si0.5 alloys prepared by spark plasma sintering using raw materials milled with different lengths of time. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1007, 176378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.G.; Huang, P.Y.; Wang, H.Y.; Qiu, Z.G.; Zeng, D.C. Physical mechanisms of large magnetocaloric effects in Mn1.95-FeP0.5Si0.5 alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1026, 180345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.H.; Lee, A.-Y.; Ahn, H.; Lee, W.; Kim, J.-W. Multi-phase transition behavior over a wide temperature range in magnetocaloric (Mn, Fe, Ni)2(P, Si) alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1005, 176140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, L.Q.; Li, B.; Du, J.; Deng, Y.F.; Zhang, Z.D. Large reversible high-temperature magnetocaloric effect in alloys. Solid State Commun. 2010, 150, 949–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelen, A.; Koželj, P.; Gačnik, D.; Vrtnik, S.; Krnel, M.; Dražić, G.; Wencka, M.; Jagličić, Z.; Feuerbacher, M.; Dolinšek, J. Collective magnetism of a single-crystalline nanocomposite FeCoCrMnAl high-entropy alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 864, 158115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kush, L.; Srivastava, S. Effect of mechanical milling and sintering on magnetic entropy of Ni-based Ni2CuCrFeAlx (x = 0.5, 1.0, 1.5 and 2.5) high entropy alloys. Phase Transit. 2022, 95, 406–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.G.; Chen, X.L.; Wang, H.Y.; Da, S.; Wang, G.; Qiu, Z.G.; Zeng, D.C.; Xia, Q.B. Giant magnetocaloric effects of MnNiSi-based high-entropy alloys near room temperature. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 966, 171483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, B.; Guo, W.; Pan, S.; Gong, Y.; Bai, Y.; Gong, Y.; Liu, J.; et al. Large reversible magnetocaloric effect in high-entropy MnFeCoNiGeSi system with low-hysteresis magnetostructural transformation. APL Mater. 2022, 10, 91107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Huang, P.; Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Da, S.; Wang, G.; Qiu, Z.; Zeng, D. Enhanced magnetocaloric properties of the (MnNi)0.6Si0.62(FeCo)0.4Ge0.38 high-entropy alloy obtained by Co substitution. Entropy 2024, 26, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarlar, K.; Tekgül, A.; Kucuk, I. Magnetocaloric properties in a FeNiGaMnSi high entropy alloy. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2020, 20, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarlar, K.; Tekgül, A.; Küçük, N.; Etemoğlu, A.B. Structural and magnetocaloric properties of FeNi high entropy alloys. Phys. Scr. 2021, 96, 125847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]