Preparation of Ni-Based Composite Coatings on the Inner Surfaces of Tubes via Cylindrical Electro-Spark Powder Deposition

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

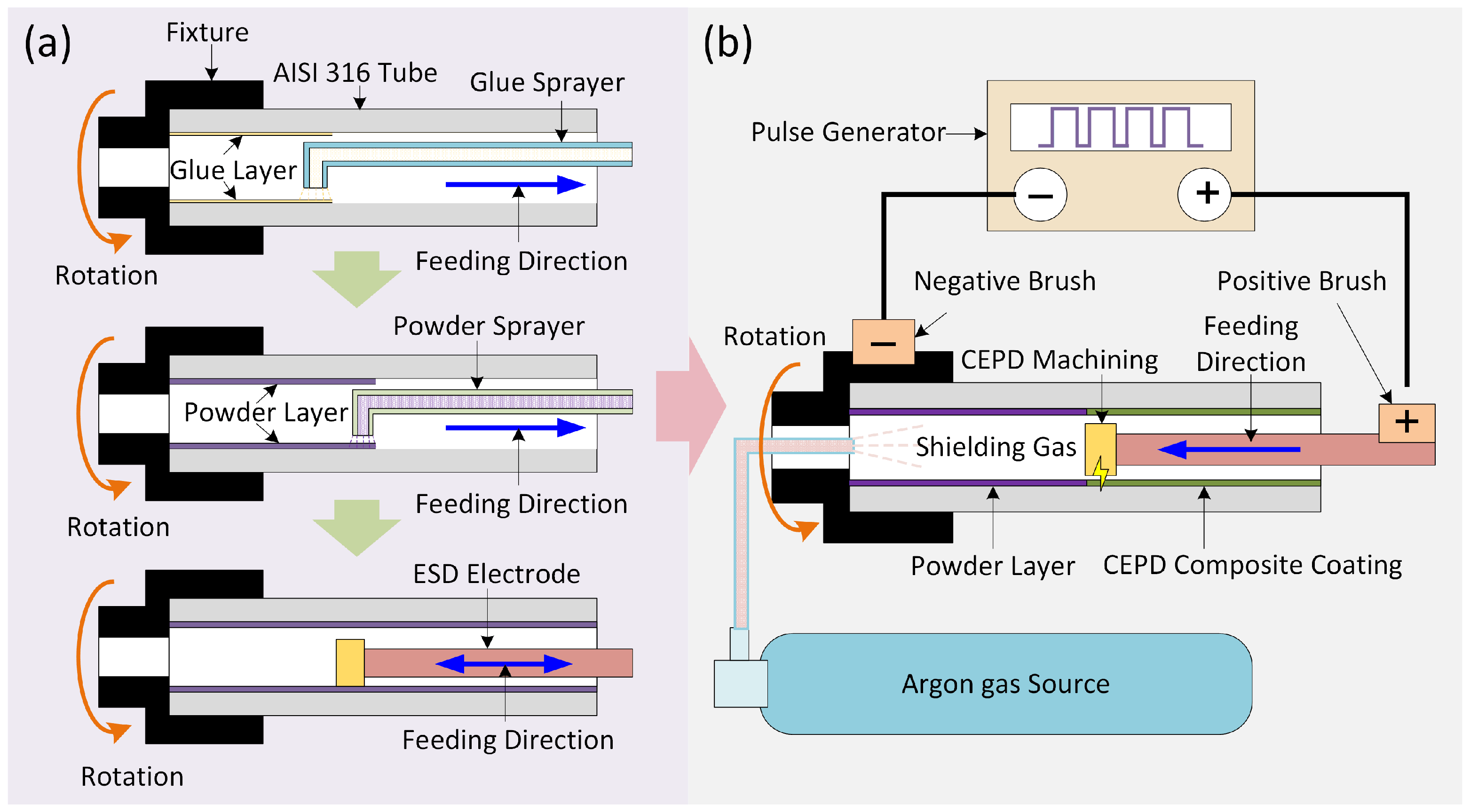

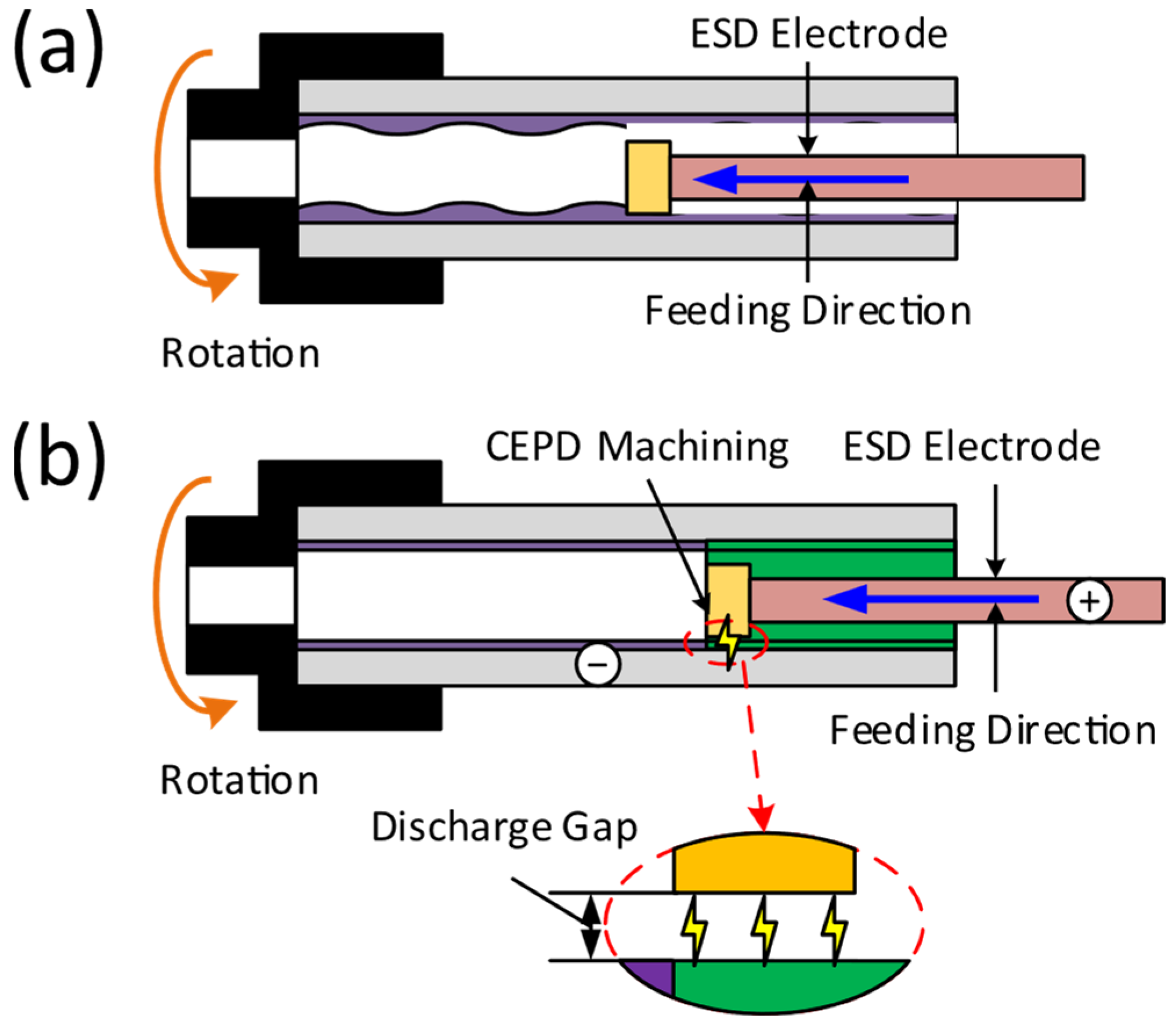

2.2. Methods

2.3. Characteristic Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

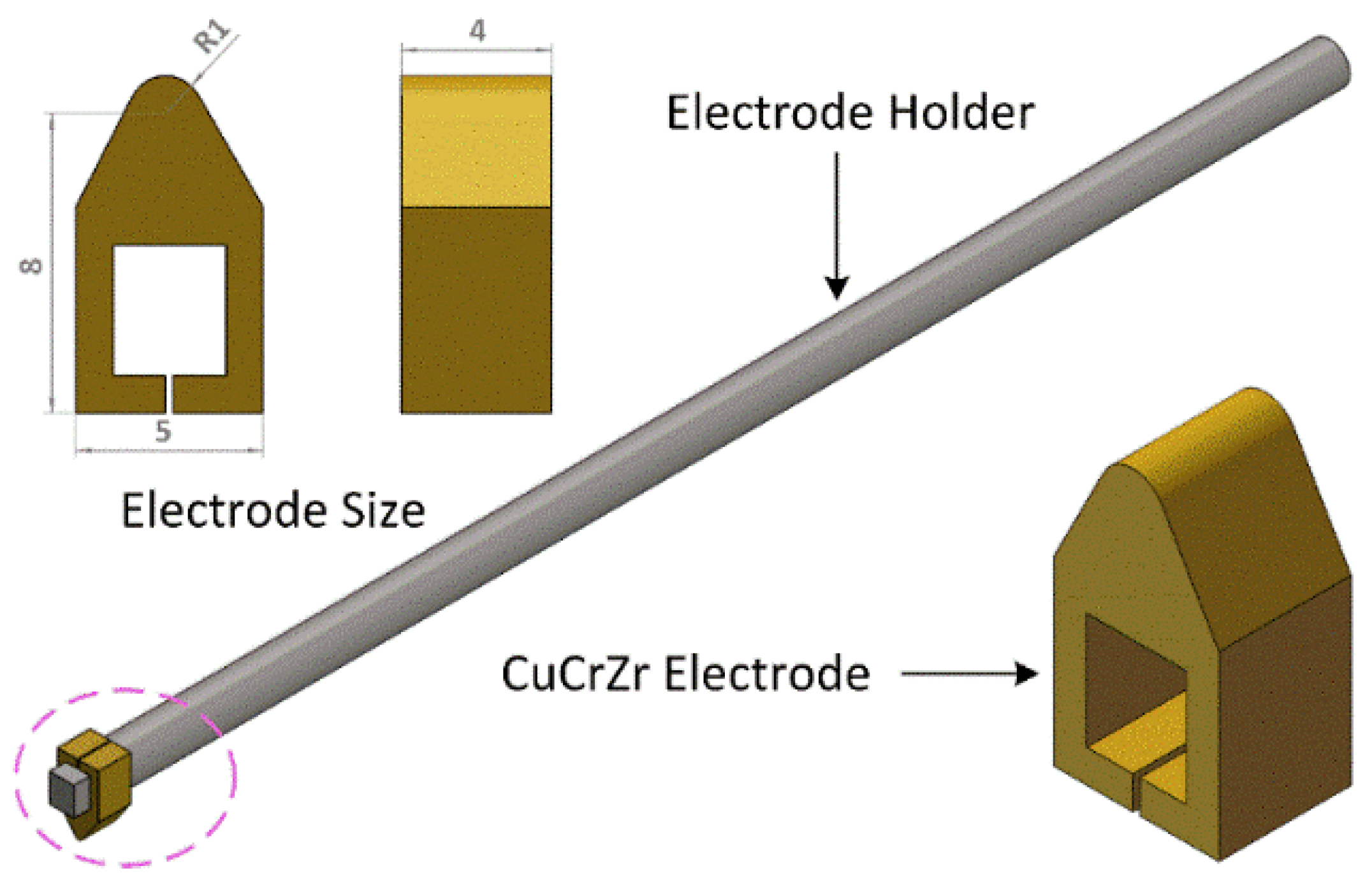

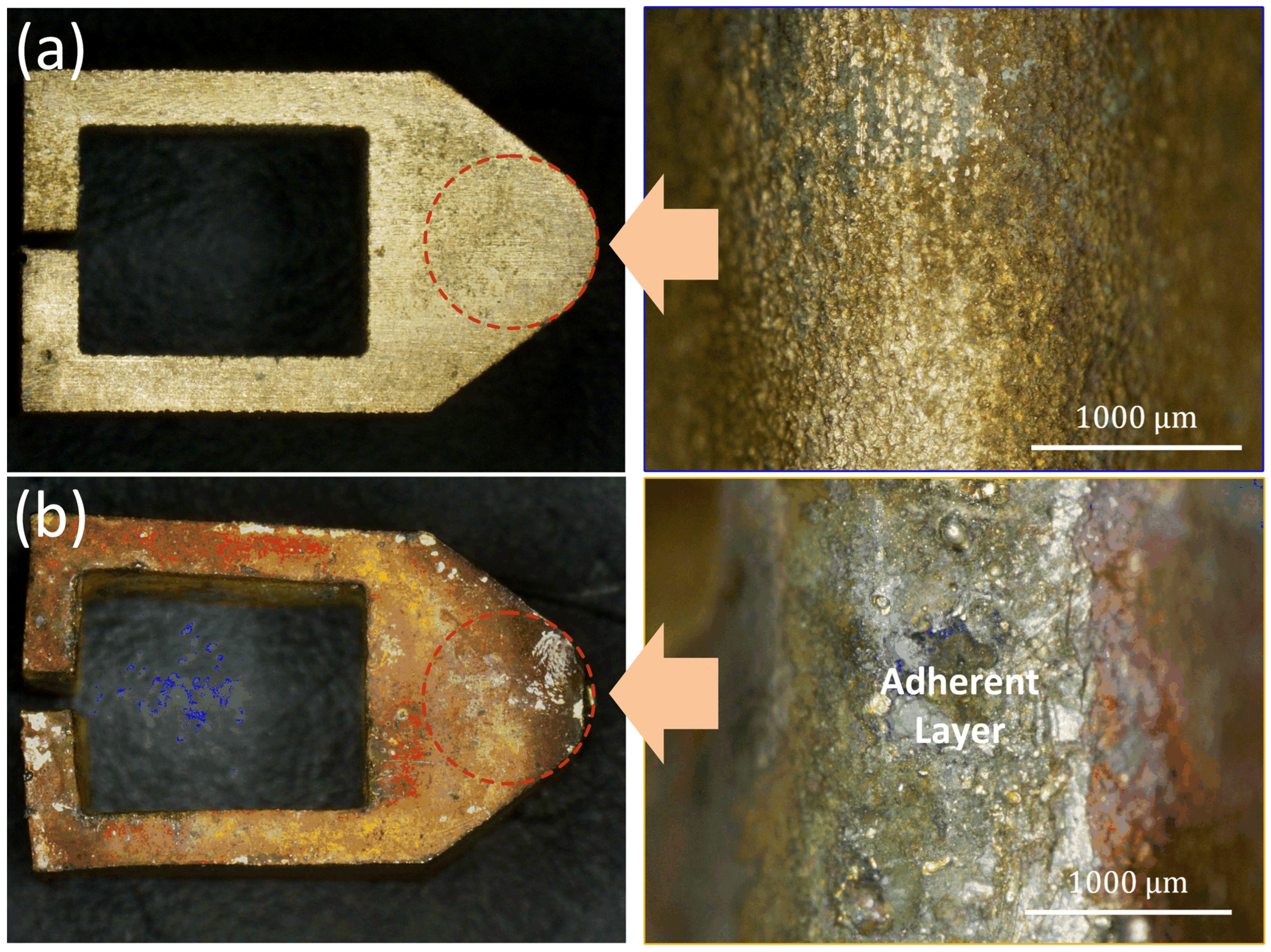

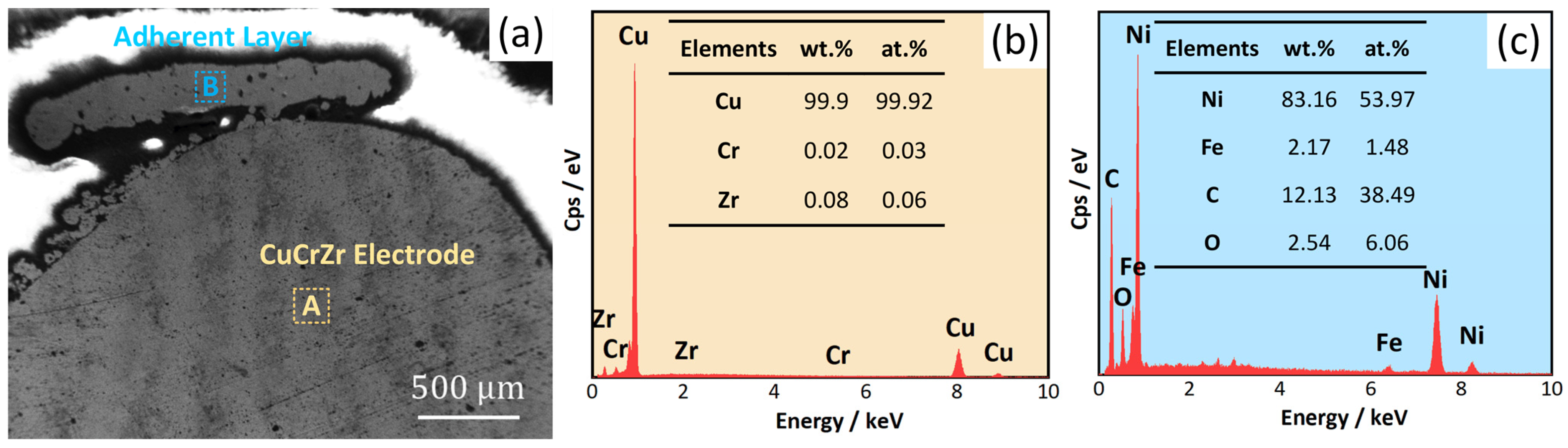

3.1. Morphology of CEPD Electrode

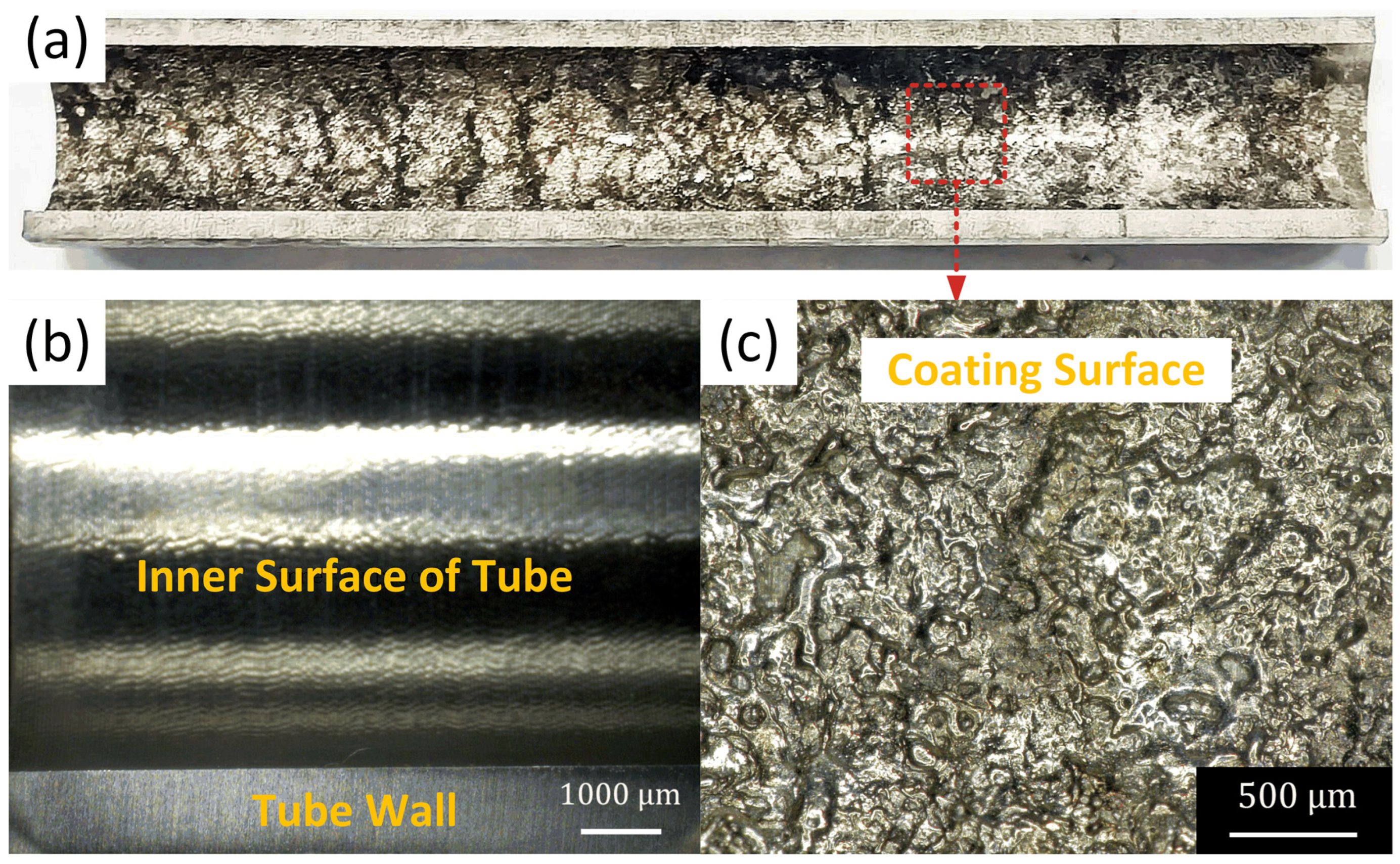

3.2. Morphology of the CEPD Coating

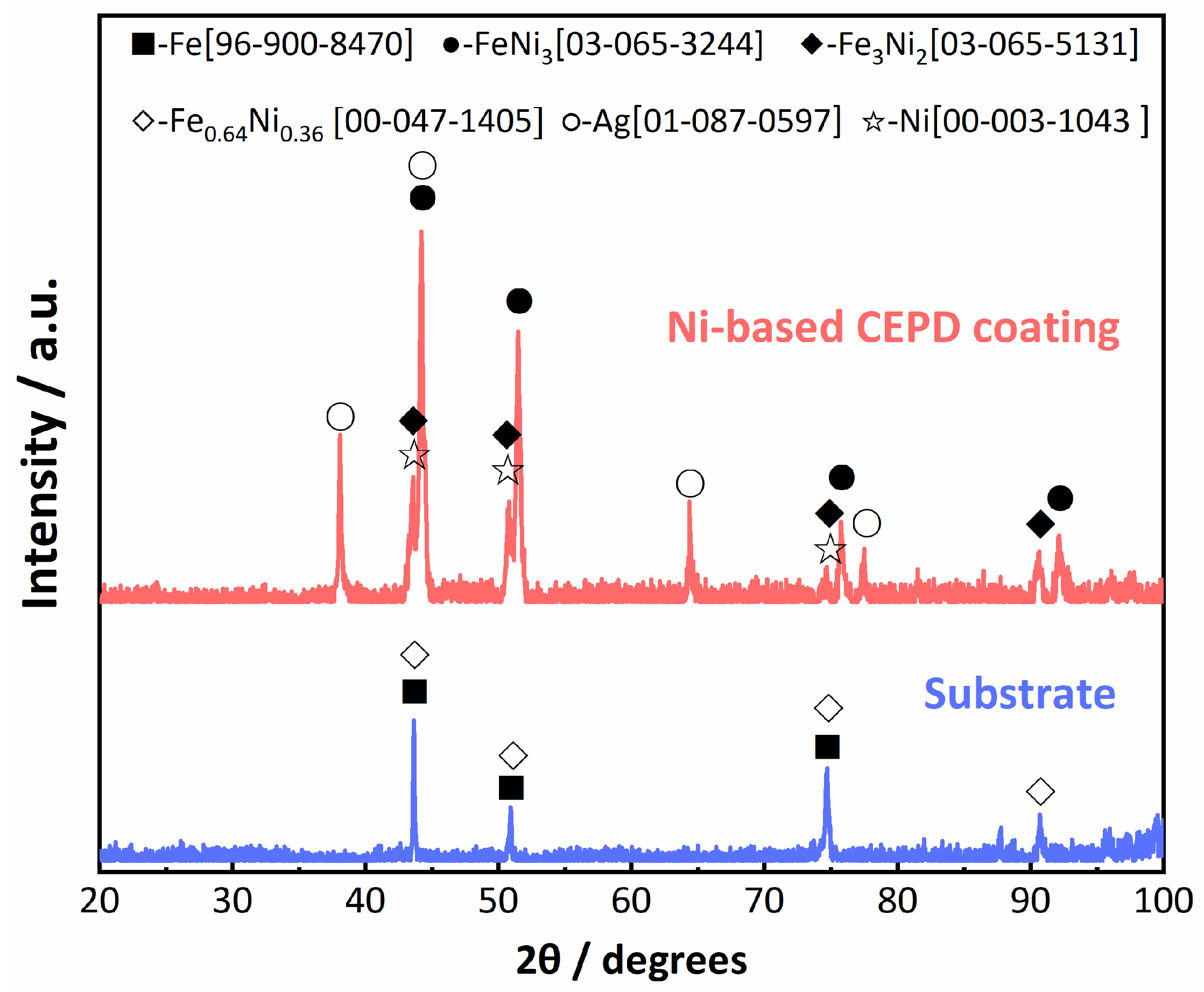

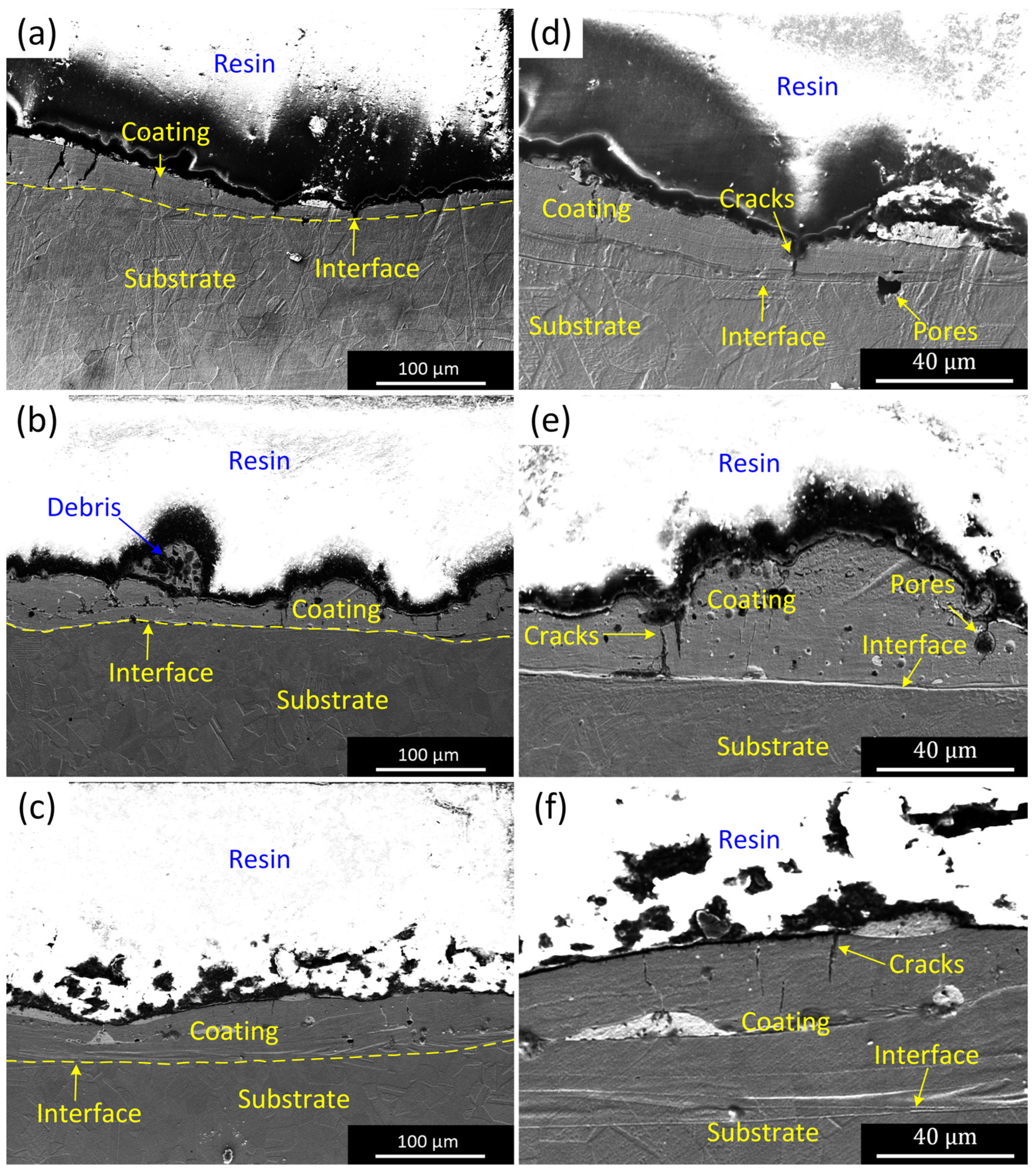

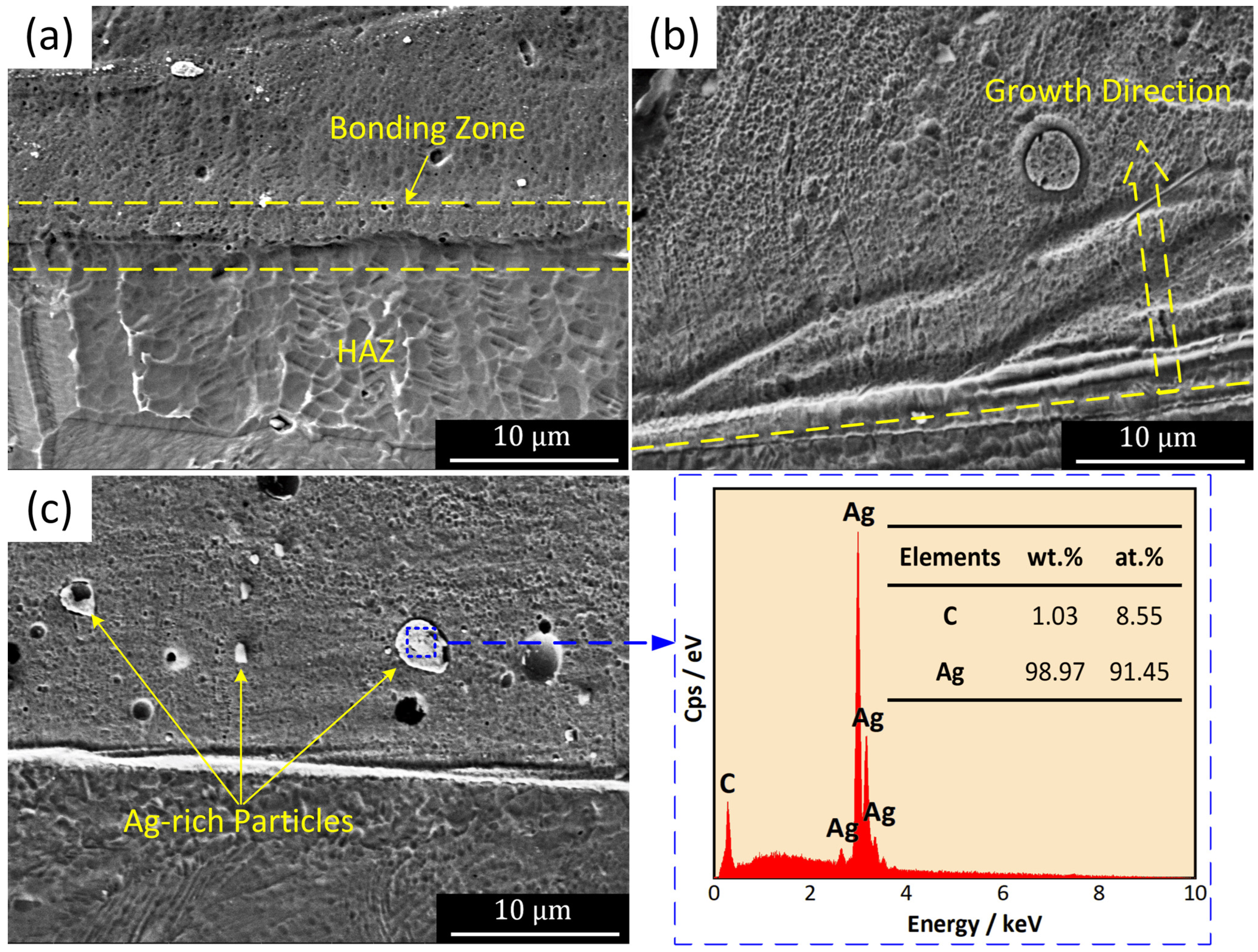

3.3. Microstructure of the CEPD Coating

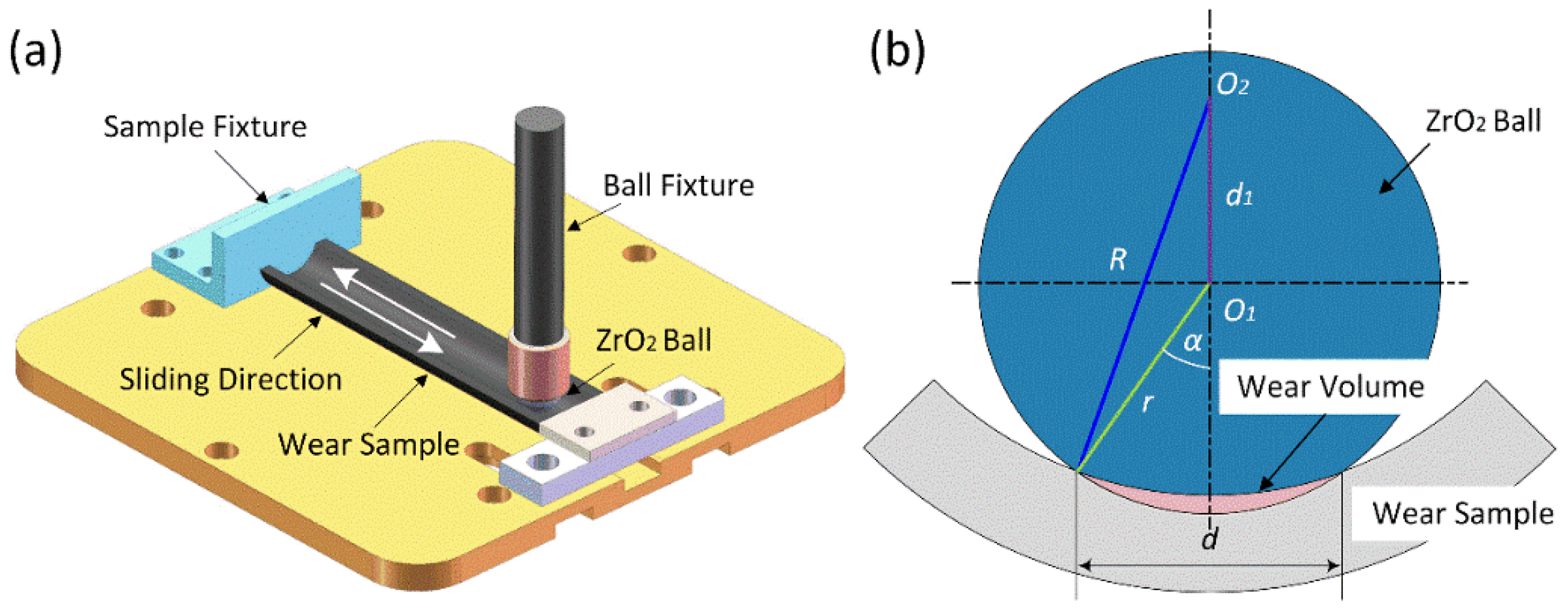

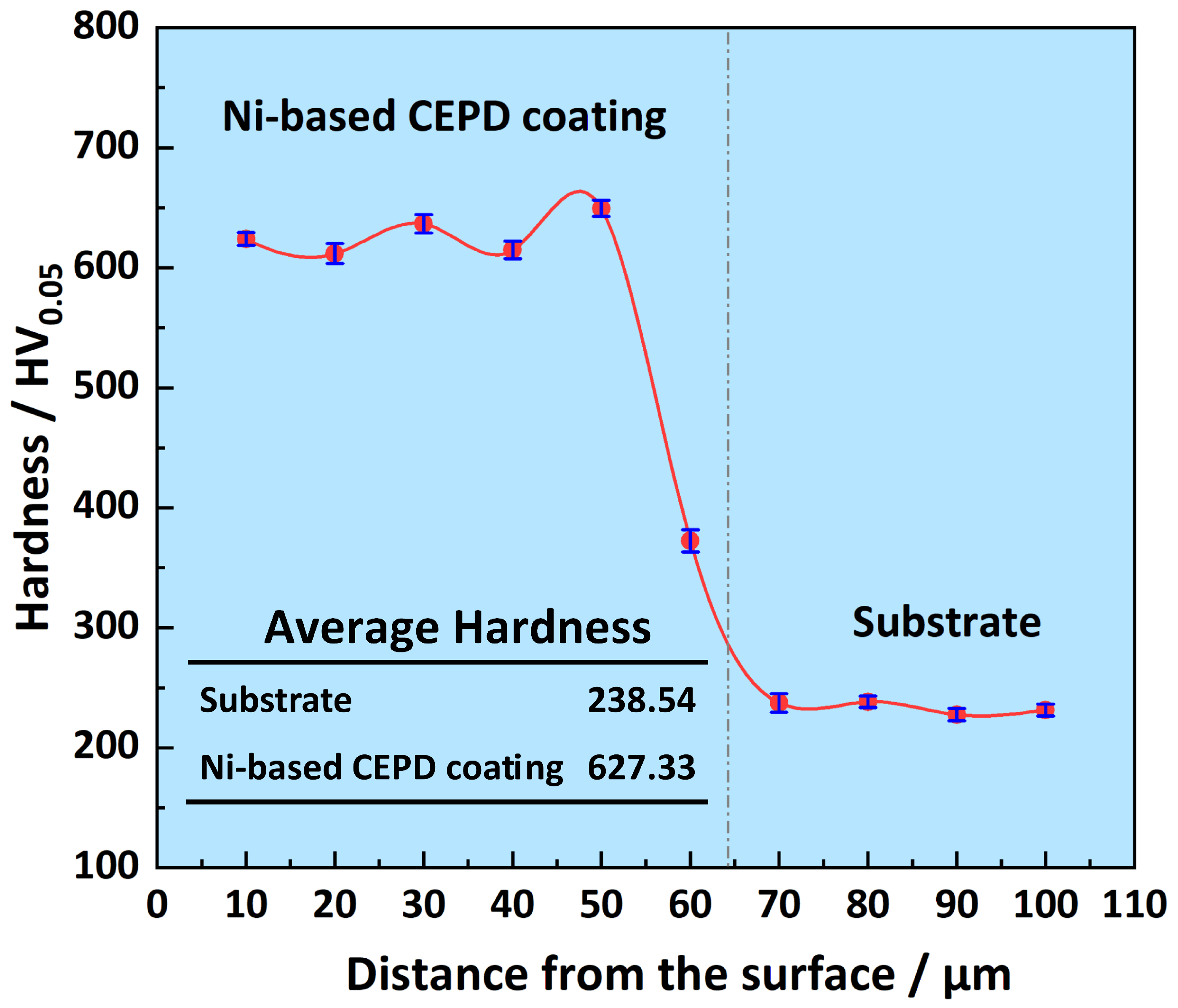

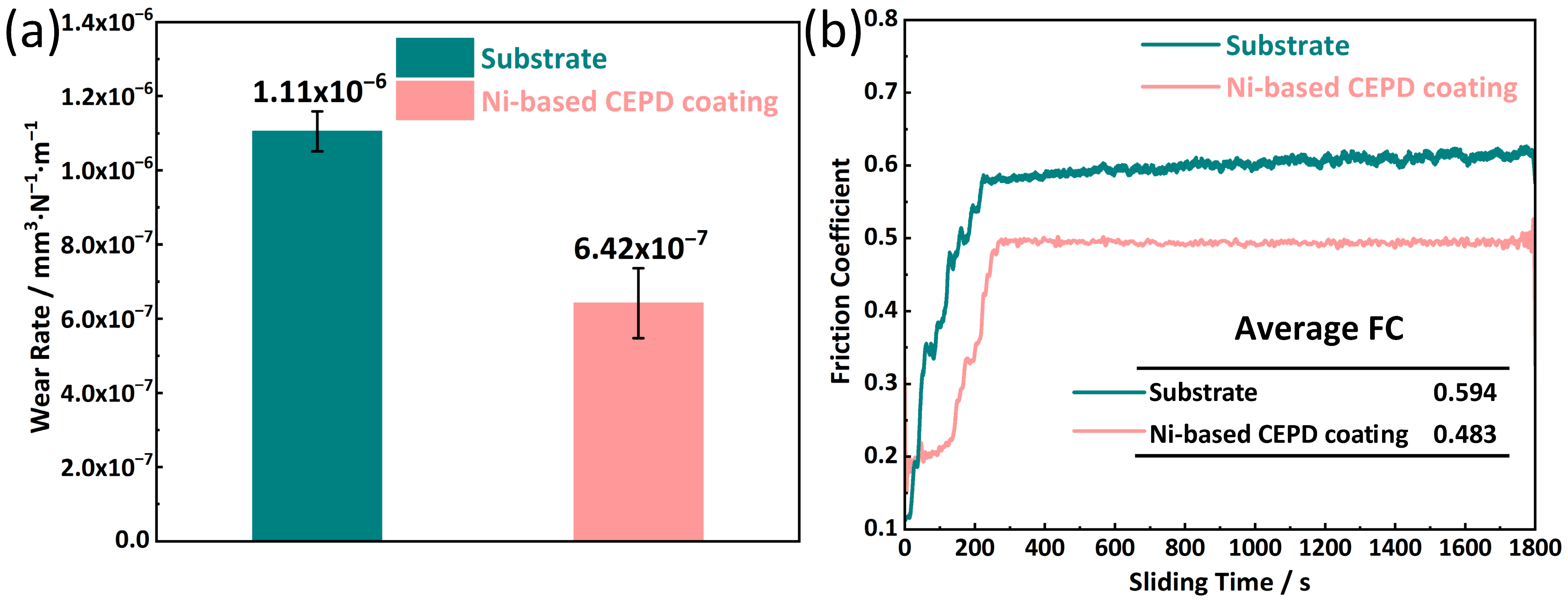

3.4. Performance of CEPD Coating

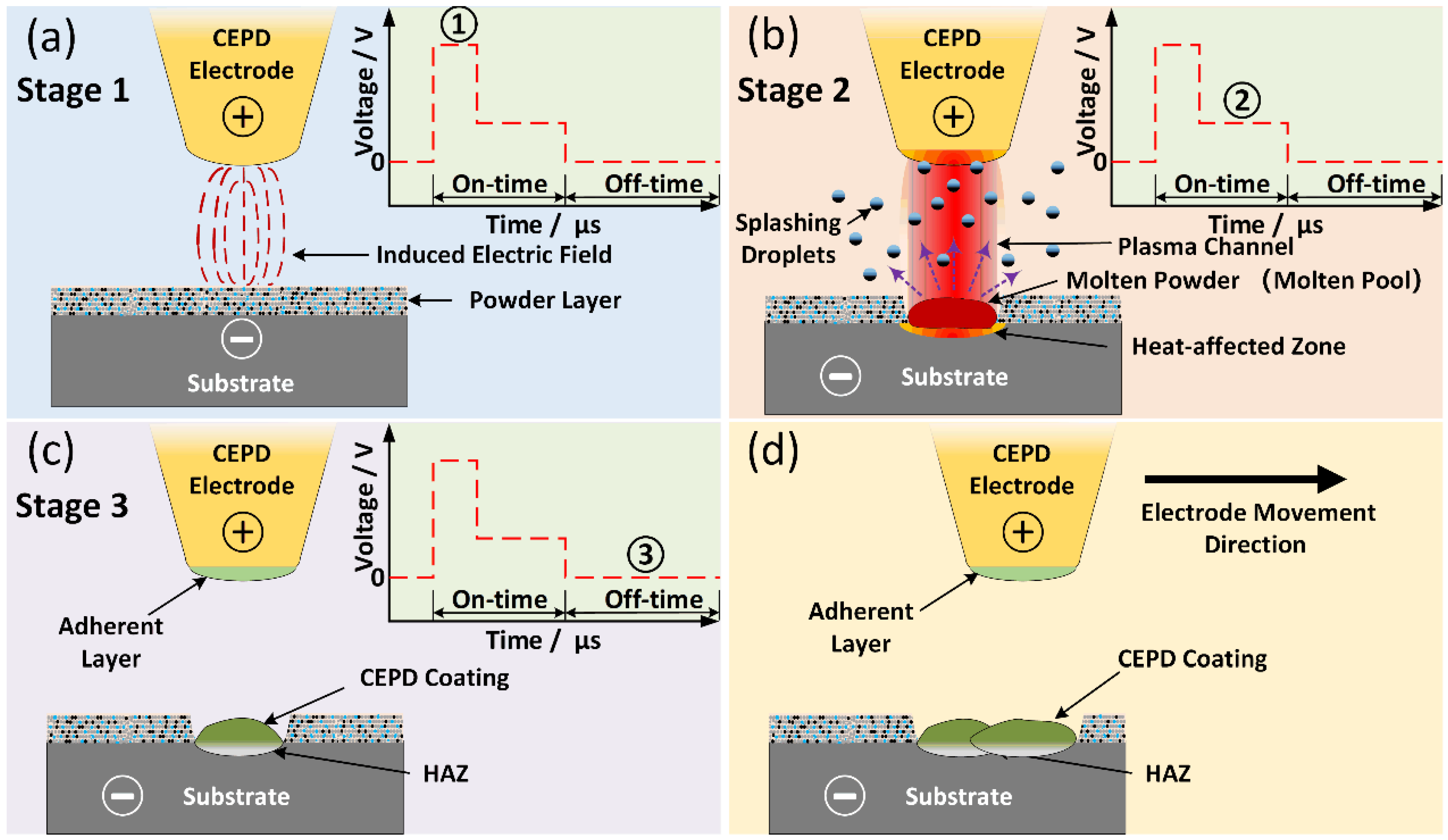

3.5. Formation Process and Mechanism of the CEPD Coating

4. Conclusions

- (1)

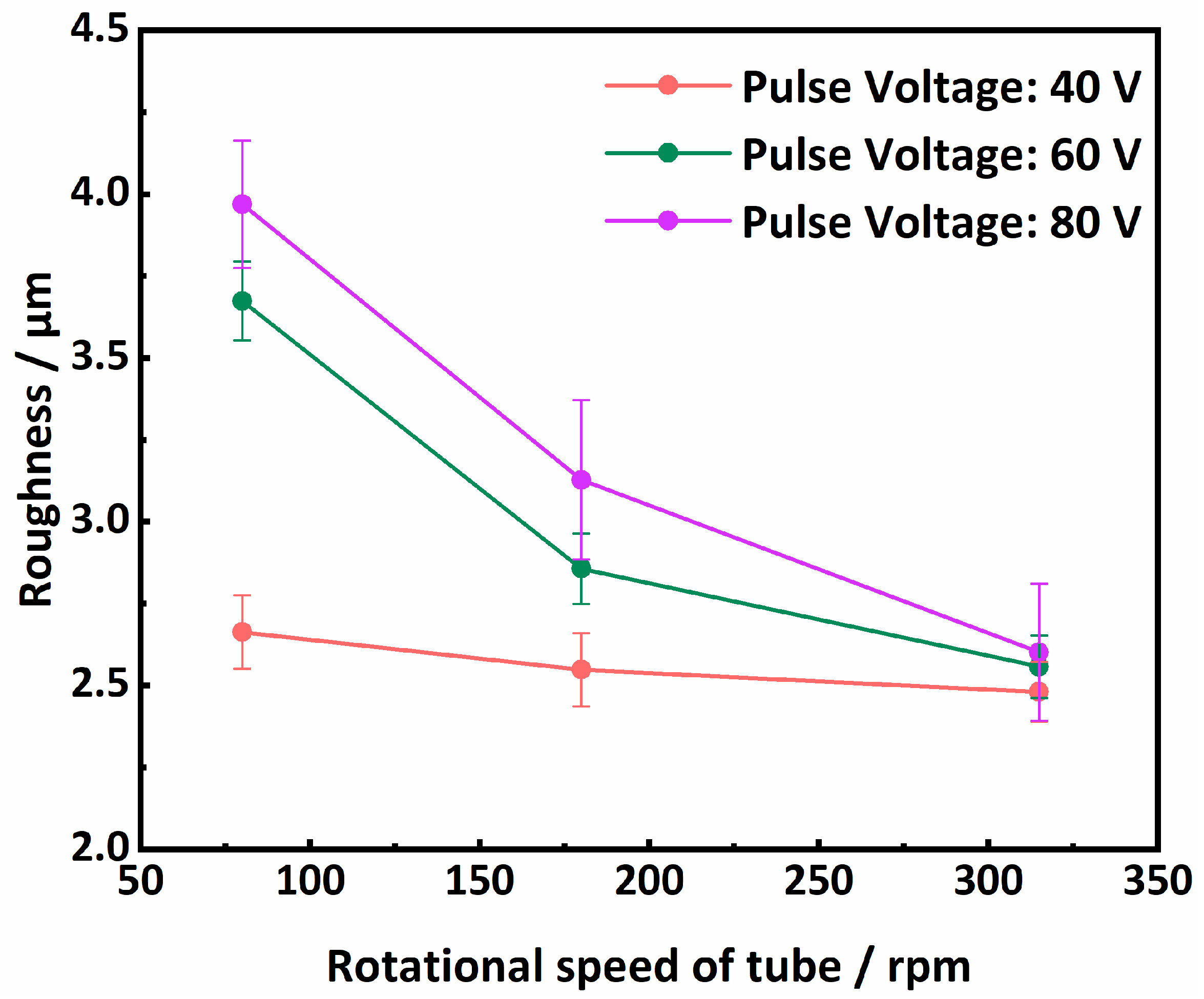

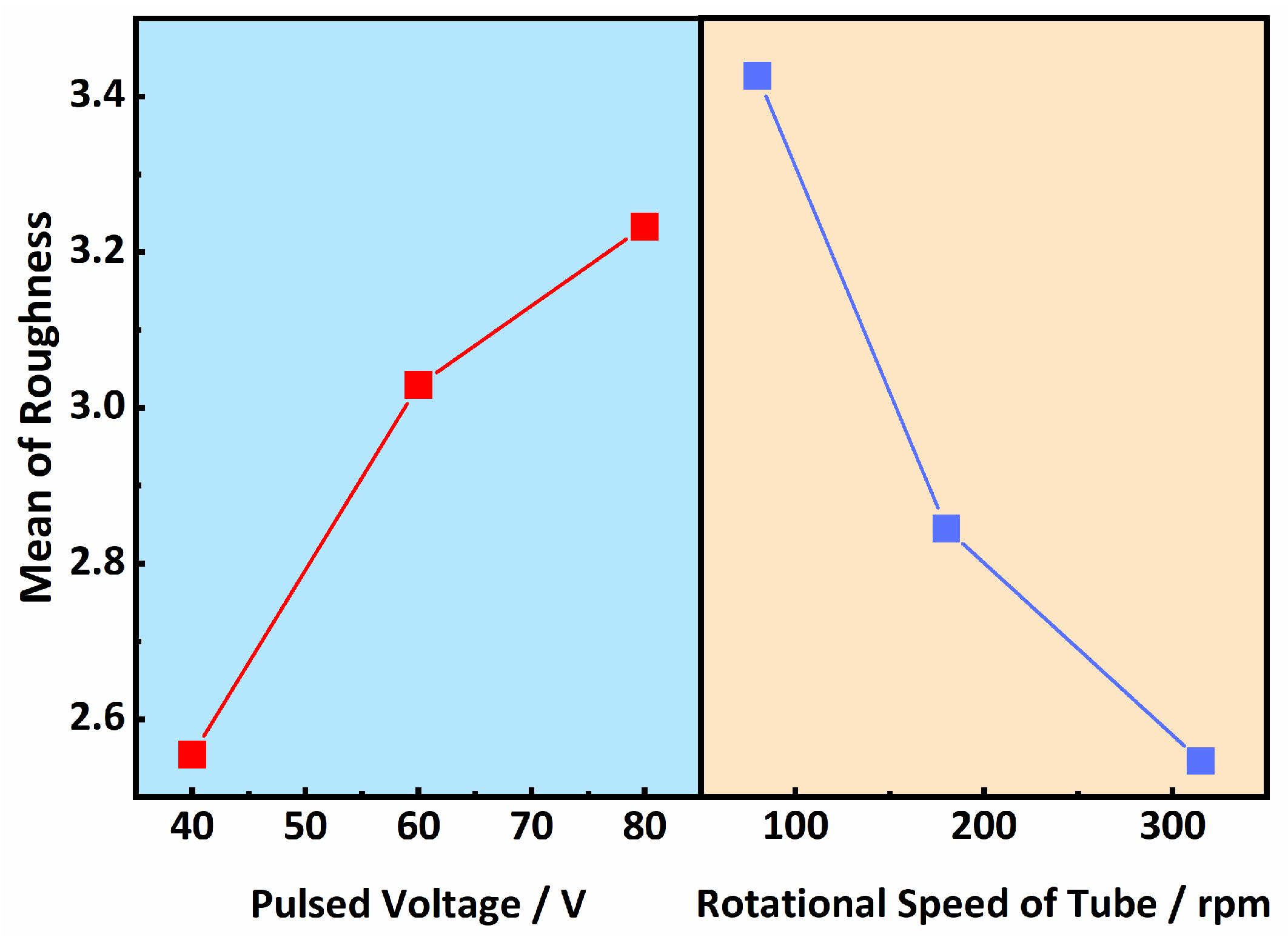

- The Ni-based composite coating achieved uniform coverage of the tube inner surface and formed a robust metallurgical bond with the substrate. The coating roughness exhibited a direct relationship with the pulse voltage and an inverse relationship with the tube’s rotational speed, with the latter exerting the most pronounced influence. The coating’s microstructure consisted of submicron dendrites oriented perpendicularly to the substrate surface, primarily composed of Ni and intermetallic compounds such as FeNi3 and Fe3Ni2. Additionally, a minor presence of Ag-rich particles was detected within the coating, predominantly originating from the Ag powder in the conductive adhesive.

- (2)

- The fine grains and intermetallic compounds within the coating significantly enhanced its hardness and tribological performance. The coating’s average hardness reached 673.33 HV, which is approximately 2.82 times higher than that of the substrate. This elevated hardness markedly improved the coating’s wear resistance, nearly doubling that of the substrate. Furthermore, the coating demonstrated superior friction-reducing capabilities, with an average friction coefficient of approximately 0.483, significantly lower than that of the substrate.

- (3)

- During the CEPD process, a plasma discharge channel was established between the electrode and the powder layer on the substrate surface. Under the high-temperature effect of the plasma channel, the powder layer and the substrate’s surface layer rapidly melted to form a mixed molten pool, which subsequently solidified into a flake-like CEPD coating. The CEPD electrode traversed and discharged along the predefined processing trajectory, with each flake-like coating overlapping adjacent sections to form a continuous coating that covered the inner tube surface.

- (4)

- Compared with other existing inner surface coating techniques, the CEPD process is not only simpler and more cost-effective but also makes it possible to fabricate functional composite coatings with complex compositions. The prepared coatings exhibit considerable potential for development and may offer a novel approach for the advancement of coating techniques on non-line-of-sight surfaces.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhang, M.; Leng, H.; Sun, B. Optimization of plating process on inner wall of metal pipe and research on coating performance. Materials 2023, 16, 2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.K.; Al Naib, U.M.B. Recent developments in graphene based metal matrix composite coatings for corrosion protection application: A review. J. Met. Mater. Miner. 2019, 29, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Zheng, X.; Hu, X.; Yin, Y.; Lei, T. Preparation of the electroless Ni-P and Ni-Cu-P coatings on engine cylinder and their tribological behaviors under bio-oil lubricated conditions. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2014, 258, 790–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michau, A.; Maury, F.; Schuster, F.; Lomello, F.; Brachet, J.C.; Rouesne, E.; Le Saux, M.; Boichot, R.; Pons, M. High-temperature oxidation resistance of chromium-based coatings deposited by DLI-MOCVD for enhanced protection of the inner surface of long tubes. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2018, 349, 1048–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, L.H.; Chu, P.K. Deposition of diamond-like carbon films on interior surface of long and slender quartz glass tube by enhanced glow discharge plasma immersion ion implantation. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2015, 265, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.F.; Nie, X.; Hu, H.; Tjong, J. Friction and counterface wear influenced by surface profiles of plasma electrolytic oxidation coatings on an aluminum A356 alloy. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2012, 30, 061402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowotny, S.; Spatzier, J.; Kubisch, F.; Scharek, S.; Ortner, J.; Beyer, E. Repair of erosion defects in gun barrels by direct Laser deposition. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2012, 21, 1173–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeß, J.; Anasenzl, M.; Ossenbrink, R.; Michailov, V.; Singh, R.; Kondas, J. Cold gas spray Inner diameter coatings and their properties. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2022, 31, 1712–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, B.; Xu, S.; Si, C. Microstructure and sliding wear properties of WC-10Co-4Cr coatings on the inner surface of TC4 slender tube by HVOF. Mater. Lett. 2022, 328, 133203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Gao, C.; Wu, X.; Xu, B.; Lu, Y.; Zhu, L. A novel method to fabricate composite coatings via ultrasonic-assisted electro-spark powder deposition. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 22528–22537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, M.; Dai, S.; Zhu, L. Research progress in electrospark deposition coatings on titanium alloy surfaces: A short review. Coatings 2023, 13, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barile, C.; Casavola, C.; Pappalettera, G.; Renna, G. Advancements in electrospark deposition (ESD) technique: A short review. Coatings 2022, 12, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.X.; Guo, C.A.; Lu, F.S.; Zhang, X.Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z.J.; Xu, Z.Y.; Zhu, G.L. Influence of deposition voltage on tribological properties of W-WS2 coatings deposited by electrospark deposition. Chalcogenide Lett. 2023, 20, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, D.; Deng, C.; Huo, L.; Wang, L.; Fang, R. Novel method to fabricate Ti-Al intermetallic compound coatings on Ti-6Al-4V alloy by combined ultrasonic impact treatment and electrospark deposition. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 628, 208–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheveyko, A.N.; Kuptsov, K.A.; Antonyuk, M.N.; Bazlov, A.I.; Shtansky, D.V. Electro-spark deposition of amorphous Fe-based coatings in vacuum and in argon controlled by surface wettability. Mater. Lett. 2022, 318, 132195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Lopes, J.G.; Chan, K.; Scotchmer, N.; Oliveira, J.P.; Zhou, Y.N.; Peng, P. Microstructure characterization of AlCrFeCoNi high-entropy alloy coating on Inconel 718 by electrospark deposition. Mater. Charact. 2025, 225, 115139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkov, A.A.; Pyachin, S.A. Formation of WC-Co coating by a novel technique of electrospark granules deposition. Mater. Des. 2015, 80, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkov, A.A.; Chigrin, P.G.; Dvornik, M.I. Electrospark Cu Ti coatings on titanium alloy Ti6Al4V: Corrosion and wear properties. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 469, 129796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkov, A.A.; Chigrin, P.G.; Kulik, M.A. Effect of TaC content on microstructure and wear behavior of PRMMC Fe-TaC coating manufactured by electrospark deposition on AISI304 stainless steel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 494, 131446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihailov, V.; Kazak, N.; Ivashcu, S.; Ovchinnikov, E.; Baciu, C.; Ianachevici, A.; Rukuiza, R.; Zunda, A. Synthesis of multicomponent coatings by electrospark alloying with powder materials. Coatings 2023, 13, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Zhang, K.; Zhou, N.Y.; Peng, P. In-situ CrFeCoNi medium entropy alloying coating via electrospark powder deposition. Surf. Eng. 2024, 40, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Gao, C.; Guo, C.; Xu, B.; Wu, X.-Y.; Lei, J.-G. In-situ TiC-reinforced Ni-based composite coatings fabricated by ultrasonic-assisted electrospark powder deposition. J. Asian Ceram. Soc. 2023, 11, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Niu, W.; Lei, Y.W.; Zheng, Y. Microstructure and wear performance of ex/in-situ TiC reinforced CoCrFeNiW0.4Si0.2 high-entropy alloy coatings by laser cladding. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1002, 175458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Gao, C.; Wu, X.; Xu, B.; Lei, J. Microstructure and tribological properties of WC-Ni cermet coatings prepared by ultrasonic-assisted electro-spark powder deposition. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2021, 57, 252–261. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, B.; Wu, H.; Lei, J.; Shen, H.; Xu, B.; Zhao, H.; Zhu, L.; Wu, X. Experimental study on electrode wear during the EDM of microgrooves with laminated electrodes consisting of various material foils. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 29, 4191–4199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmaliyan, M.; Malek Ghaeni, F.; Ebrahimnia, M. Effect of electro spark deposition process parameters on WC-Co coating on H13 steel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2017, 321, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghababaei, R.; Zhao, K. Micromechanics of material detachment during adhesive wear: A numerical assessment of Archard’s wear model. Wear 2021, 476, 203739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, B.; Singh, A.D.; Sengupta, S.; Nadakuduru, V.N.; Mundotiya, B.M. Enhancement of wear resistance in electrodeposited Ni-Ag self-lubricated alloy coatings via in-situ formation of solid lubricating phases for high-temperature tribological applications. Wear 2025, 578–579, 206177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algodi, S.J.; Murray, J.W.; Fay, M.W.; Clare, A.T.; Brown, P.D. Electrical discharge coating of nanostructured TiC-Fe cermets on 304 stainless steel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2016, 307, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahmand, P.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Kovacevic, R. Laser cladding assisted by induction heating of Ni-WC composite enhanced by nano-WC and La2O3. Ceram. Int. 2014, 40, 15421–15438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Zeng, X.; Hu, Q.; Huang, Y. Analysis of crack behavior for Ni-based WC composite coatings by laser cladding and crack-free realization. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2008, 255, 1646–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chemical Elements | C | P | Cr | Si | Mn | Mo | Ni | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contents | ≤0.08 | ≤0.045 | 16~18 | ≤1 | ≤2 | 2~3 | 10~14 | Bal. |

| Chemical Elements | B | C | Cr | Fe | Si | Ni |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contents | 0.4~0.9 | 14~17 | 3.5~4.5 | 2.5~3.0 | 5 | Bal. |

| Chemical Elements | P | Cr | Zr | Fe | Mg | Zn | AI | Cu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contents | 0.1 | 0.1–0.8 | 0.1–0.6 | ≤0.5 | 0.1–0.25 | 0.003 | ≤0.5 | Bal. |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Axial feed ratio of the electrode | 0.05 mm/r |

| Rotational speed of the tube | 80 rpm, 180 rpm, 315 rpm |

| Argon flow | 4 L/min |

| Pulse voltage | 40 V, 60 V, 80 V |

| Pulse width | 90 us |

| Pulse frequencies | 300 Hz |

| Factor | DF | Adj SS | Adj MS | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PV | 2 | 0.7285 | 0.3642 | ≤0.01 |

| RST | 2 | 1.2006 | 0.6003 | ≤0.01 |

| Interaction (PV × RST) | 4 | 0.4332 | 0.1083 | ≤0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, H.; Yu, G.; Guo, X.; Luo, F.; Zhu, F.; Lei, Y. Preparation of Ni-Based Composite Coatings on the Inner Surfaces of Tubes via Cylindrical Electro-Spark Powder Deposition. Coatings 2025, 15, 1426. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121426

Zhao H, Yu G, Guo X, Luo F, Zhu F, Lei Y. Preparation of Ni-Based Composite Coatings on the Inner Surfaces of Tubes via Cylindrical Electro-Spark Powder Deposition. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1426. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121426

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Hang, Gaowei Yu, Xinwen Guo, Fei Luo, Fengbo Zhu, and Yaohu Lei. 2025. "Preparation of Ni-Based Composite Coatings on the Inner Surfaces of Tubes via Cylindrical Electro-Spark Powder Deposition" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1426. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121426

APA StyleZhao, H., Yu, G., Guo, X., Luo, F., Zhu, F., & Lei, Y. (2025). Preparation of Ni-Based Composite Coatings on the Inner Surfaces of Tubes via Cylindrical Electro-Spark Powder Deposition. Coatings, 15(12), 1426. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121426