Abstract

With the growing demand for durable and corrosion-resistant materials in advanced Li-ion battery cases, super duplex stainless steels (SDSSs) have emerged as promising candidates due to their excellent mechanical and electrochemical properties. This study aims to investigate how the ferrite and austenite phase balance in SDSS EN 1.4501 affects the microstructural and electrochemical behavior of Ag coatings, tailored for next-generation battery enclosure applications. Ag coatings were deposited to PVD (to 1 μm) on SDSS EN 1.4501 substrates with varying ferrite (from 32 vol.% to 70 vol.%) and austenite ratios (from 56 vol.% to 30 vol.%) to evaluate the influence of phase balance on coating performance. Microstructural analysis was performed using field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, mag x 1000), electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD), and X-ray diffraction (XRD, from 20° to 80°), which provided insights into surface morphology, crystallographic texture, and phase distribution. Electrochemical characteristics were assessed through open circuit potential (OCP), and potentiodynamic polarization in a simulated corrosive environment. The results showed that a balanced duplex microstructure promoted superior Ag coating adhesion, grain refinement, and uniform phase distribution. Furthermore, the electrochemical analyses indicated enhanced corrosion resistance and passivation layer stability in volume fraction balanced substrates, as evidenced by more noble OCP values (form −0.06 V to −0.11 V), and potentiodynamic polarization value (higher corrosion potential (from 0.08 V to 0.10 V), and lower corrosion current densities (from 3 × 10−7 A/cm2 to 4 × 10−7 A/cm2)). These findings demonstrate that optimizing the phase balance in SDSS is critical for achieving high-performance Ag coated surfaces, offering significant potential for durable and corrosion-resistant Li ion battery casing applications.

1. Introduction

The rapid advancement of lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) for electric vehicles, grid scale energy storage, and portable electronics has intensified the demand for reliable and corrosion resistant battery casings capable of ensuring mechanical integrity and electrochemical stability under harsh service environments [1,2,3]. Battery enclosures are routinely exposed to aggressive conditions such as chloride-rich atmospheres, elevated temperatures, and cyclic mechanical loads, leading to a heightened risk of localized corrosion, which may compromise battery safety, lifespan, and performance [4,5,6].

To address the growing safety concerns associated with Li-ion battery cases and housings, the structural materials used for battery enclosures have evolved from polymers to aluminum alloys, and more recently to stainless steel (EN 1.4301). Although this transition has significantly improved mechanical and thermal safety, EN 1.4301 (an austenitic stainless steel) still exhibits limitations, including susceptibility to impact-induced embrittlement and localized corrosion. Among the various stainless steel grades, super duplex stainless steels (SDSSs) offer a promising alternative due to their superior mechanical strength, balanced duplex microstructure, and exceptional corrosion resistance. However, their application to battery case materials remains largely unexplored, necessitating comprehensive research to evaluate their electrochemical stability, surface treatment compatibility, and long-term reliability under battery operating environments.

Super duplex stainless steels (SDSSs) have emerged as promising casing materials due to their superior combination of high strength and resistance to pitting and crevice corrosion, derived from their characteristic dual-phase microstructure comprising ferrite (δ) and austenite (γ) phases in nearly balanced proportions. In particular, SDSS EN 1.4501 (UNS S32750) has garnered attention owing to its high pitting resistance equivalent number (PREN > 40), elevated mechanical performance, and improved resistance to localized corrosion compared to conventional stainless steels [7,8]. However, recent studies indicate that even SDSS is susceptible to degradation when exposed to highly aggressive chloride environments, especially under open circuit or potential carrying conditions frequently encountered in battery applications [9,10].

To mitigate such limitations, surface modification by noble metal coatings has been recognized as an effective strategy [11,12]. Among them, silver (Ag) coatings are of particular interest due to their exceptional corrosion resistance, high electrical conductivity, and electrochemical inertness, making them highly suitable for battery components where both protective and conductive functions are essential [13,14]. Ag coatings not only act as a physical barrier against chloride ingress but also stabilize passive film formation on the substrate, reduce interfacial resistance, and enhance the long-term electrochemical stability of stainless steels under severe conditions. Furthermore, Ag’s noble potential is highly advantageous for LIB casings, where the enclosure often serves as part of the grounding or current-carrying structure, demanding minimal electrochemical degradation and superior conductivity [15,16]. Despite these benefits, the adhesion, uniformity, and electrochemical performance of Ag coatings strongly depend on the substrate’s microstructural characteristics, particularly the phase balance in SDSS.

However, the influence of the ferrite and austenite ratio on the microstructural evolution and electrochemical properties of Ag coatings remains poorly understood, especially for applications requiring both mechanical robustness and electrochemical reliability [17,18]. Since the duplex phase balance critically governs grain boundary distribution, precipitation tendency, and texture evolution, its impact on coating–substrate interactions are expected to be significant but has been insufficiently investigated.

In our previous two publications, we investigated the effects of secondary phase precipitation in super duplex stainless steel (SDSS) and its influence on Ag-coating performance [19,20]. The first study examined how the formation of secondary phases affects elemental composition, surface roughness, and crystallographic characteristics of SDSS, followed by an evaluation of Ag-coating behavior using OCP and EIS measurements. The second study focused on the impact of secondary phase precipitation on the microstructure and corrosion behavior of SDSS. Together, these works confirmed the critical role of secondary phases, with one study specifically addressing their influence on Ag coatings. However, these investigations did not sufficiently address how ferritization alters the phase balance and consequently affects coating behavior, and research on the microstructural evolution of ferritized SDSS remains limited. Therefore, a comprehensive investigation linking secondary phase precipitation, ferritization, and Ag-coating performance is still required to fully understand substrate–coating interactions.

Furthermore, despite extensive studies on secondary phase formation and corrosion behavior in SDSS, a critical knowledge gap remains regarding how controlled ferrite–austenite phase ratios directly influence Ag-coating behavior, chloride penetration resistance, and galvanic interactions under battery-related environments. Therefore, the objective of this study is to establish a clear correlation between phase fraction, microstructural evolution, Ag-coating crystallography, and electrochemical performance, enabling a deeper understanding of substrate–coating interactions essential for Li-ion battery casing applications. The novelty of this research lies in systematically engineering the ferrite–austenite balance over a wide temperature range,) evaluating how these controlled microstructures govern Ag-coating conductivity, passive film stability, and galvanic corrosion, and demonstrating, for the first time, that optimizing the SDSS phase balance is a key strategy for enhancing both the protective and functional properties of Ag-coated casing materials.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Commercial super duplex stainless steel (SDSS) EN 1.4501 was employed as the substrate material [21,22]. The nominal chemical composition of the SDSS is listed in Table 1. The SDSS plates were cut into 15 × 15 × 3 mm specimens using a CNC precision cutter, followed by sequential grinding up to 2000 grit and mirror polishing using 1 μm diamond suspension. The as-cast SDSS specimens (#α) were first subjected to solution annealing (#β) at 1100 °C for 1 h to eliminate undesirable intermetallic phases and to homogenize the microstructure [23,24]. After solution treatment at 1100 °C, the samples were water-quenched at a cooling rate of approximately 50 °C/s.

Table 1.

Chemical composition (wt.%) of the as-cast SDSS EN 1.4501 substrate analyzed by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

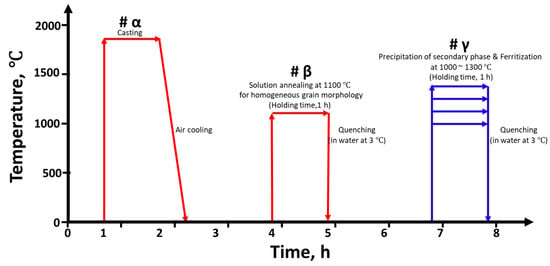

A schematic illustration of the heat treatment procedures and conditions is presented in Figure 1. EN 1.4501, with a melting point of approximately 1350 °C, forms δ-ferrite at elevated temperatures due to its high alloying content of Cr, Ni, Mo, followed by the transformation to austenite during subsequent cooling. The resulting phase volume fractions are highly dependent on the applied heat-treatment conditions, and variations in this phase balance directly influence the corrosion resistance of the alloy. To systematically control the ferrite-to-austenite (δ/γ) phase ratio, additional heat treatments were conducted at various temperatures ranging from 1000 °C to 1300 °C for 1 h (#γ), followed by water quenching at the same cooling rate (50 °C/s) [20,25]. This controlled thermal treatment enabled the adjustment of the duplex phase balance while minimizing the formation of deleterious secondary phases such as sigma (σ) phase and chromium nitrides.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the heat treatment schedule employed to adjust the ferrite–austenite phase balance in super duplex stainless steel EN 1.4501.

The SDSS plates were cut into 15 × 15 × 3 mm specimens using a CNC precision cutter, followed by sequential grinding up to 2000 grit and mirror polishing using 1 μm diamond suspension. Prior to Ag coating, all SDSS samples were mechanically ground using SiC abrasive papers up to #2000 grit and polished to achieve a surface roughness (Ra) below 50 nm, as confirmed by atomic force microscopy (AFM, Park system, Suwon, Republic of Korea) [26,27]. This surface preparation was essential to ensure uniform Ag coating morphology and strong interfacial adhesion.

Silver (Ag) coatings by physical vapor deposition (PVD, Laon Tech, Anseong-si, Republic of Korea) were deposited onto the prepared SDSS substrates via thermal evaporation under a high vacuum (<10−5 Torr). The deposition was conducted at a controlled rate of 0.1 nm/s to achieve a uniform coating thickness. After deposition, the coated specimens were stored in a desiccator prior to microstructural and electrochemical characterizations.

2.2. Microstructural Characterization

The surface morphology and cross-sectional microstructure of the Ag-coated SDSS specimens were characterized using field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, JSM-7610F, Oberkochen, Germany) [28,29]. Surface and cross-sectional images were obtained at magnifications of ×1000 to observe both the coating morphology and microstructural features in detail.

The crystallographic texture and phase distribution were analyzed via electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD, JSM-7610F, Oberkochen, Germany) with a step size of 0.2 μm. EBSD measurements were performed at a magnification of ×1000 to ensure sufficient resolution for phase mapping and grain orientation analysis [28,30]. To measure the phase fractions, five repeated analyses by EBSD were performed, and the average value was used.

Phase identification and residual stress analysis were further conducted using X-ray diffraction (XRD, Bruker D8 Advance, Karlsruhe, Germany) with Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) operated at 40 kV and 40 mA [31,32]. XRD patterns were collected over a 2θ range of 20° to 80° with a step size of 0.01°. The ferrite-austenite phase ratio was quantitatively determined from EBSD phase maps and further validated by XRD Rietveld refinement.

Electrical conductivity after Ag coating with volume fraction of SDSS was evaluated using AFM, and five repeated measurements were performed to verify the reproducibility of the results.

2.3. Electrochemical Measurements

Electrochemical tests were carried out using a conventional three-electrode system connected to a potentio-stat (VersaSTAT 4.0, AMETEK, Inc., Berwyn, PA, USA) to evaluate the corrosion behavior of the Ag-coated SDSS samples [33,34]. The coated specimen served as the working electrode, a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) as the reference electrode, and a platinum mesh as the counter electrode. The purpose of this experiment is to evaluate the corrosion behavior of materials used for battery cases and housings. Because the focus of this study is on external—rather than internal—corrosion, 3.5 wt.% NaCl was selected as the test environment to simulate chloride-induced degradation under external service conditions [35].

The open circuit potential (OCP) was recorded for 1 h to monitor the potential evolution of the Ag-coated SDSS in relation to its position in the electrochemical series (EMF series) and to evaluate the thermodynamic nobility and spontaneous passivation behavior of the coatings [36,37]. OCP measurement provides essential information regarding the tendency of the coated specimen to undergo spontaneous corrosion or passivation under immersion without external polarization.

Subsequently, potentiodynamic polarization tests were performed from −0.6 V to +1.2 V vs. OCP at a scan rate of 0.167 mV/s [35,38]. This test was aimed at investigating both the anodic and cathodic polarization behavior of the Ag-coated SDSS samples, particularly focusing on the activation-controlled anodic region to assess the kinetics of initial metal dissolution and the subsequent passive film formation. From the polarization curves, critical electrochemical parameters such as corrosion potential (Ecorr), corrosion current density (Icorr), and passivation behavior were derived.

3. Results

3.1. Microstructure After Casting and Annealing of EN 1.4501

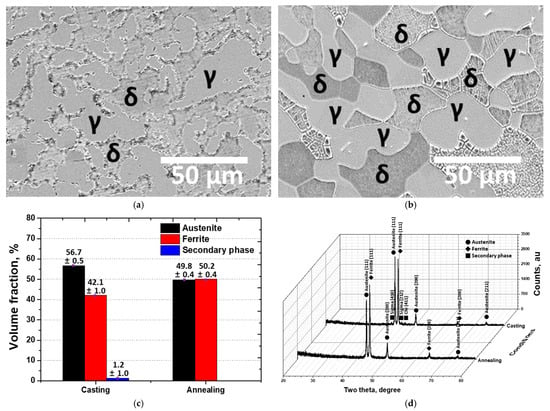

Since super duplex stainless steel (SDSS) consists of both austenite and ferrite phases, the morphology of the grains is an important factor that significantly affects its corrosion resistance [39,40]. In this study, the SDSS EN 1.4501 material was directly cast in our laboratory, and its microstructure was characterized using FE-SEM, EBSD-based volume fraction measurements, and XRD analysis, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

(a) FE-SEM micrographs of as-casted SDSS EN 1.4501 specimens, (b) FE-SEM micrographs of annealed SDSS EN 1.4501 specimens, (c) Phase volume fractions of casting and annealing specimens, (d) XRD patterns with indexed peaks corresponding to austenite, ferrite, and secondary phases.

After casting, the austenite phase of SDSS exhibited a non-uniform morphology. The austenite grains showed no specific growth orientation, and their volume fraction was measured to be 56 vol.%. The irregular morphology of the austenite phase reduced the ferrite fraction and caused local segregation, leading to the precipitation of secondary phases such as sigma (410), sigma (212), and chi (411). However, after solution heat treatment, a uniform austenite morphology was observed, and the secondary phases were completely dissolved into both the austenite and ferrite phases [41,42]. In addition, the volume fractions of austenite and ferrite were found to be equal (5:5) [43,44]. These results are consistent with previously reported findings, indicating that the manufacturing condition of the SDSS was appropriate.

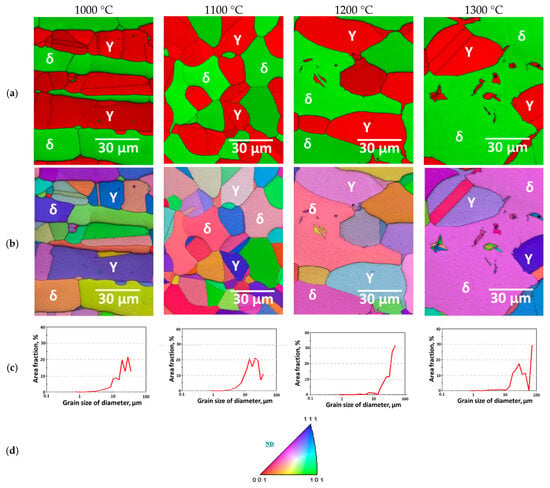

3.2. Effect of Heat Treatment Temperature

To investigate the effect of the SDSS matrix microstructure on the electrical conductivity of Ag coatings, the base microstructure of SDSS EN 1.4501 was controlled through four types of heat treatments. The controlled microstructures after heat treatment with volume fraction of specimens were classified as secondary-phase precipitation (Figure 3a), solution annealing (Figure 3b), and ferritization (Figure 3c,d), as shown in Figure 3 [45,46]. In the Phase–IQ map, the secondary phases were not clearly distinguishable between ferrite (Sigma is BCT structure, not distinguished from BCC in EBSD) and austenite (Chi is cubic structure, not distinguished from FCC in EBSD) [41,47]. In the IPF–IQ map, most of the grains were found to grow along the (111) orientation. However, when secondary phases precipitated, the grains exhibited orientations close to (111) and (001), while those in the solution annealing and ferritization condition showed orientations close to (111) and (101). This indicates that the grain orientation changes during secondary-phase precipitation. Grain coarsening was also observed in the ferritization microstructure. Before solution heat treatment, the grains had a size below 30 μm with a volume fraction of less than 10 vol.%, whereas during ferritization, the fraction of coarse grains (>30 μm) increased. After heat treatment at 1200 °C, the ferrite grain boundaries became indistinct, and the austenite grains were coarsened. A similar trend was observed after heat treatment at 1300 °C, where the degree of grain coarsening further increased, as shown in Figure 3c.

Figure 3.

(a) Phase-IQ maps; (b) Inverse pole figure (IPF)-IQ maps; (c) Area fraction as a function of equivalent grain diameter; (d) Stereographic triangle indicating the color key used in the IPF maps.

The crystallographic morphology and orientation of austenite and ferrite in SDSS were examined, and the structural evolution with heat treatment temperature was compared. The precipitation of secondary phases is known to occur when the austenite fraction exceeds approximately 56 vol.%, caused by the segregation of Cr and Mo during austenite growth [30,47]. This behavior was observed in the specimen heat-treated at 1000 °C. However, among the secondary phases, sigma exhibits the same lattice structure as ferrite and is therefore indistinguishable, while chi has the same lattice structure as austenite and cannot be separately identified. Consequently, although the morphologies of austenite and ferrite appear altered by the presence of secondary phases, these changes are attributed to secondary-phase precipitation.

By controlling the heat treatment conditions of SDSS, the precipitation of secondary phases was found to occur preferentially at the austenite–ferrite interfaces; however, the distinction of these phases by EBSD was not straightforward [48,49]. Ferritization exhibited temperature-dependent differences between the austenitic and ferritic regions. Above 1200 °C, the ferritization microstructure appeared as a single-phase structure. Austenite grains also coarsened, and the amount of fine austenite decreased. The coarsened austenite grains exhibited sizes exceeding 40 μm, and this distinction became more pronounced as the heat-treatment temperature increased.

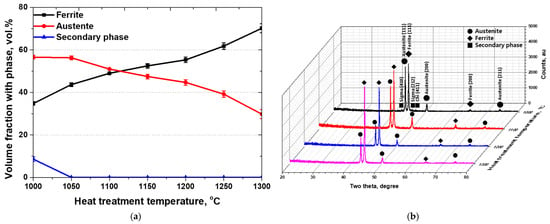

Based on the EBSD results, the phase fractions after heat treatment were quantified, and the corresponding phases were analyzed using X-ray diffraction (XRD) [50,51]. The variation in phase fraction with heat treatment temperature exhibited a trend consistent with those reported in previous studies. At 1000 °C, more than 8 vol.% of secondary phases precipitated and were subsequently dissolved into the austenite and ferrite matrices [31,32]. As the temperature increased, the volume fraction of ferrite gradually increased while that of austenite decreased, reaching an equal ratio between the austenite and ferrite at 1100 °C. With further progression of ferritization, the ferrite fraction increased up to 70 vol.%.

These changes in volume fraction of austenite and ferrite were attributed to the influence of heat treatment temperature, and the corresponding variations were confirmed by XRD analysis [40,41]. The XRD results and phase fraction analysis are presented in Figure 4. The peak intensity trends observed in XRD were consistent with the volume fraction results obtained from FE-SEM. The secondary phases were identified as sigma and chi; the sigma phase grew along the (410) and (212) planes, while the chi phase developed along the (411) plane. The major diffraction peaks of austenite and ferrite were observed at (111), with lower intensities detected at (200) and (211). These results demonstrate that the heat treatment of SDSS EN 1.4501 produces four distinct microstructure conditions, which serve as key factors influencing both the physical and electrochemical properties of the material. Therefore, to utilize EN 1.4501 as a battery case material, it is essential to analyze the Ag coating behavior in relation to these microstructural characteristics.

Figure 4.

(a) Volume fraction with phase, and (b) X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of SDSS EN 1.4501 specimens’ specimens solution-annealed at temperatures ranging from 1000 °C to 1300 °C, collected over a 2θ range of 20° to 80°.

3.3. Ag-Coated Super Duplex Stainless Steel Surface

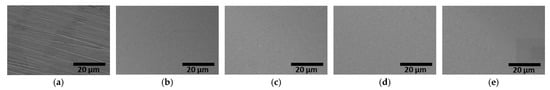

To evaluate the effect of phase fraction on the Ag coating behavior, the surface morphology and condition were analyzed [11,52]. The surface morphology was examined using FE-SEM, and the results are presented in Figure 5. No significant differences were observed in the surface images depending on the matrix microstructure [12,53]. The PVD evaporation process appeared to be unaffected by the underlying microstructure. To further examine the surface condition, surface composition, phase, and electrical conductivity were analyzed using glow discharge spectroscopy (GDS), X-ray diffraction (XRD), and a four-point probe method, respectively.

Figure 5.

FE-SEM image of Ag coated surface with volume fraction of austenite and ferrite on super duplex stainless steel EN 1.4501 (a) before ag coating, (b) with secondary phase (c) solution annealing condition, (d) volume fraction of ferrite over 60 vol.%, and (e) volume fraction of ferrite over 70 vol.%.

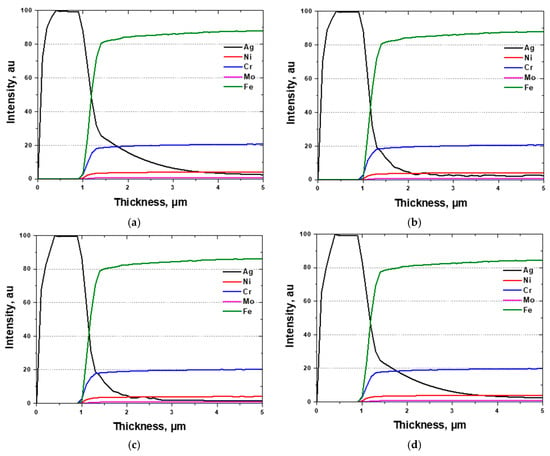

Since GDS enables compositional analysis from the surface toward the depth direction, it is an appropriate technique for investigating the elemental distribution of coated or plated surfaces [14,53]. Therefore, compositional analysis after Ag coating was performed using GDS, and the results are shown in Figure 6 The depth profile revealed an Ag coating thickness of approximately 0.96 μm and a mixed interfacial layer within 0.4 μm from the surface. The behavior of the Ag coating was found to be independent of the phase fraction of SDSS, which is consistent with the surface morphology observations. These results confirm that the phase fraction of SDSS EN 1.4501 does not influence the PVD evaporation process used for Ag coating. Moreover, GDS analysis verified that a uniform Ag coating layer was successfully formed on the SDSS surface.

Figure 6.

Glow discharge spectroscopy (GDS) results with volume fraction of austenite and ferrite on super duplex stainless steel EN 1.4501. (a) with secondary phase (b) solution annealing condition, (c) volume fraction of ferrite over 60 vol.%, and (d) volume fraction of ferrite over 70 vol.%.

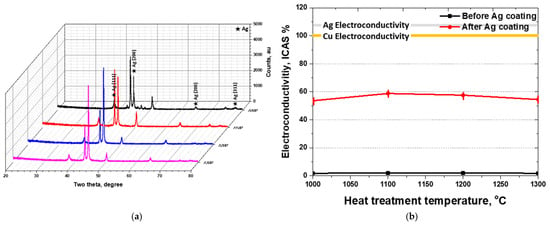

To investigate the effect of Ag coating on the properties of SDSS, X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis and electrical conductivity measurements were conducted. The results of XRD and electrical conductivity after Ag coating are presented in Figure 7 [31,54]. In the XRD patterns, characteristic diffraction peaks of Ag were observed at 38° (111), 44° (200), 65° (220), and 77° (311). The XRD results of the Ag-coated samples displayed both SDSS and Ag peaks, indicating that the coating layer retained the distinct crystal structures of each material. This combination of peaks was consistent with the results obtained from FE-SEM and GDS analyses. No formation of new compounds between Ag and SDSS was detected, and both materials maintained their intrinsic crystallographic features.

Figure 7.

(a) X-ray diffraction pattern (XRD), and (b) Electrical conductivity with volume fraction of austenite and ferrite on super duplex stainless steel EN 1.4501.

Although the Ag coating layer was uniformly formed, variations in electrical conductivity were observed. The electrical conductivity of uncoated SDSS was 1.9 IACS %, which increased to 59 IACS % after deposition of a 1 μm thick Ag layer. This value is lower than that of pure Cu (100 IACS %) and Ag (108 IACS %). Moreover, differences in substrate microstructure led to variations in electrical conductivity, with both secondary phases and ferrite identified as major factors reducing conductivity. As the ferrite fraction increased from 50 vol.% to 70 vol.%, the electrical conductivity decreased from 59 IACS % to 54 IACS %. Additionally, when 8.6 vol.% of secondary phases precipitated, the conductivity further decreased to 54 IACS %. These results indicate that variations in phase fraction—specifically the proportions of austenite, ferrite, and secondary phases—significantly influence the electrical conductivity of SDSS after Ag coating.

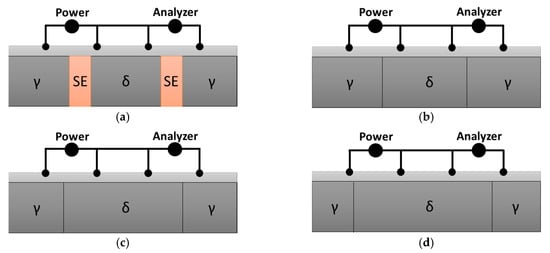

A schematic illustration of the effect of the Ag coating layer on electrical conductivity is presented in Figure 8. The SDSS sample coated with a 1 μm thick Ag layer exhibited a uniform coating surface and improved electrical conductivity; however, its conductivity was still influenced by the underlying matrix microstructure [55,56]. The Ag coating layer enhances the overall conductivity, but the electrical performance of the battery case is ultimately affected by the microstructural characteristics of the SDSS substrate. Therefore, it was confirmed that controlling both the microstructure and electrical conductivity of the base metal is essential for optimizing the conductivity of battery case materials.

Figure 8.

Schematic illustration of electrical conductivity measurement of super duplex stainless steel using the four-point probe method under different microstructural conditions: (a) secondary-phase precipitation, (b) solution annealing, (c) ferritization to 60 vol.% ferrite, and (d) ferritization to 70 vol.% ferrite.

Since the SDSS-based battery case is influenced by both the surface coating layer and the matrix microstructure, microstructural control of the base metal is necessary. Among the matrix components, secondary phases increase electrical resistance due to their high grain-boundary density and crystallographic mismatch, thereby reducing conductivity. Additionally, ferrite, which has a body-centered cubic (BCC) crystal structure, exhibits lower electrical conductivity than the face-centered cubic (FCC) austenite phase, further decreasing the overall conductivity. Thus, both the secondary phases and ferrite act as detrimental factors to electrical conductivity in SDSS. Consequently, maximizing the fraction of austenite while minimizing the fraction of ferrite is expected to be an effective approach for optimizing the electrical conductivity of SDSS used in Ag-coated battery case applications.

3.4. Effect of Ag-Coating on Electrochemical Behavior

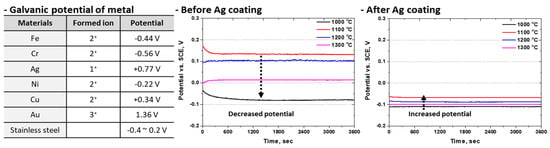

To evaluate the electrochemical performance of Ag-coated SDSS surfaces, open-circuit potential (OCP), and potentiodynamic polarization were conducted. The reactivity of metallic materials can be estimated using galvanic potential; however, for alloys, it is not directly calculable. Nevertheless, the galvanic potential can be approximated by applying the Nernst equation to the measured electrochemical parameters. Therefore, OCP measurements were used to compare electrochemical reactivity. The effect of Ag coating on OCP was analyzed, and the results, along with the corresponding galvanic potentials, are shown in Figure 9 [38,57]. Stainless steels typically form mixed passive films composed of chromium oxide (Cr2O3) and iron oxide (Fe2O3), and a more uniform chromium-rich oxide film results in a higher potential.

Figure 9.

Galvanic potential of major alloys and open circuit potential results with or without Ag coating on super duplex stainless steel EN 1.4501 in 3.5 wt.% NaCl electrolyte solution.

The potential of uncoated SDSS was found within the typical range for stainless steels, from −0.1 V to 0.2 V. Variations in the potential were observed depending on the phase fraction of the SDSS, indicating that galvanic interactions between the austenite and ferrite phases influence the overall electrochemical response. After Ag coating, the OCP values showed noticeable changes. Although the potential differences associated with the phase fraction decreased after coating, all potentials shifted toward more negative values. This shift suggests that the Ag coating alters the intrinsic reactivity of the material. According to previous studies, such behavior is commonly attributed to the pinhole effect, in which micro-defects within the coating allow the electrolyte to interact with the underlying substrate [58].

The electrochemical reactivity of SDSS varied depending on the phase fraction, as changes in microstructure acted as galvanic corrosion sites and altered the potential. After solution heat treatment, the potential decreased, while an increased ferrite fraction and secondary phase precipitation further reduced the potential. The variation trend in potential before and after Ag coating was similar. The Ag coating layer appeared to enhance galvanic coupling effects, making the less noble phases more susceptible to corrosion.

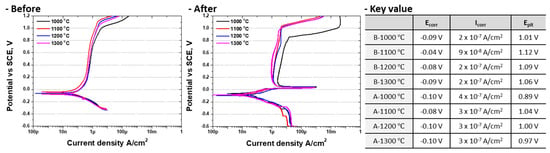

Potentiodynamic polarization tests were conducted to evaluate corrosion behavior by measuring current response as a function of applied potential. The polarization behaviors before and after Ag coating are shown in Figure 10. The corrosion behavior of EN 1.4501 varied with the heat treatment induced microstructural changes. In the active polarization region (red box in Figure 10 diagrams), the corrosion potential (Ecorr) followed the same trend as OCP and exhibited a corrosion current density below 2 × 10−7 A/cm2. In the passive region (blue box in Figure 10 diagrams), excellent corrosion resistance was observed with a current density below 4 × 10−5 A/cm2. After passivation, the transpassive (pitting) potential appeared near 1.12 V, beyond which the current density increased rapidly. This behavior is consistent with that of conventional SDSS; however, notable changes were observed after Ag coating.

Figure 10.

Potentiodynamic polarization curve and Major value before or after 1 μm Ag coating on super duplex stainless steel EN 1.4501 in 3.5 wt.% NaCl electrolyte solution.

For Ag-coated SDSS, the active polarization behavior remained similar to that of uncoated SDSS but showed a decrease in Ecorr and an increase in Icorr. No stable passivation occurred after activation, and the current density continued to rise. At 0.01 V, the current density increased to 1 × 10−3 A/cm2, then decreased to 1 × 10−6 A/cm2 at 0.05 V. The onset of passivation was observed around 1 × 10−4 A/cm2, while the pitting potential (Epit) decreased to 0.89 V. In the presence of secondary phases (major value indicated by the red dashed line in Figure 9), the corrosion rate increased significantly, and the electrochemical potential decreased sharply, indicating that secondary phases were more susceptible to galvanic corrosion induced by the Ag coating. Similarly, ferritized microstructures exhibited reduced corrosion resistance due to galvanic coupling between Ag and the substrate.

These results demonstrate that Ag acts as a galvanic corrosion promoter, accelerating corrosion when coupled with SDSS microstructures. The potentiodynamic polarization results further confirm that both Ag coating and the phase fraction of SDSS influence the corrosion behavior. The occurrence of galvanic corrosion after Ag deposition indicates that the Ag coating layer functions as a corrosion-promoting element rather than a protective barrier. Chloride ions are able to diffuse through intrinsic micro-defects in the Ag coating, including pores, grain boundaries, and pinholes formed during PVD deposition. These pathways facilitate Cl− migration toward the interface, potentially leading to AgCl formation and localized galvanic reactions [58]. Furthermore, this behavior suggests that the Ag coating layer cannot effectively prevent Cl−-induced corrosion in NaCl environments. Therefore, even with a uniform Ag coating, additional strategies are required to inhibit Cl− penetration and mitigate galvanic corrosion for practical applications in battery case materials.

4. Discussion

Super duplex stainless steel (SDSS) EN 1.4501 possesses excellent mechanical strength and corrosion resistance, making it a suitable candidate for use as casing and housing material in energy storage systems (ESS) [59]. The solution heat treatment after casting stabilized the microstructure of SDSS. However, subsequent variations in phase fraction during manufacturing processes altered the proportions of austenite and ferrite, which acted as factors that reduced corrosion resistance.

During the physical vapor deposition (PVD) process, no significant difference in coating ability was observed depending on the phase fraction of SDSS [60]; therefore, the deposition of a 1 μm thick Ag coating layer proceeded uniformly [11,13]. A uniform surface morphology was confirmed by FE-SEM, and the Ag coating thickness was verified by GDS analysis. A homogeneous Ag coating layer was obtained regardless of the SDSS phase fraction [61,62]. However, electrical conductivity measurements using the four-point probe method revealed a strong dependence on the SDSS matrix microstructure, which significantly affected the electrode’s electrical conductivity. In particular, increases in the fractions of secondary phases and ferrite acted as factors that decreased electrical conductivity, suggesting a potential influence on battery performance. Therefore, when fabricating SDSS-based battery cases, the phase fraction of SDSS must be carefully controlled.

The electrochemical behavior of Ag-coated SDSS as a function of phase fraction was analyzed using OCP and potentiodynamic polarization tests [29,57]. The OCP results showed that after Ag coating, the potential decreased from 0.15 V to –0.05 V in the solution-annealed specimen. This trend was consistent with the corrosion potential (Ecorr) observed in the activation region of the polarization curves, and the corrosion current density (Icorr) increased from 9 × 10−8 to 3 × 10−7 A/cm2 [17,21]. Such corrosion behavior corresponds to that of stainless steel and is attributed to galvanic corrosion induced by the Ag layer. Therefore, Ag coating on SDSS promotes galvanic corrosion, which in turn decreases corrosion resistance.

Although Ag coating enhances the electrical conductivity of SDSS, the phase fraction of the substrate remains a critical factor influencing conductivity and must be precisely controlled. Furthermore, the electrochemical behavior of SDSS is affected by the presence of Ag, which accelerates galvanic corrosion. Consequently, when applying conductive coatings or plating to improve electrical conductivity, surface control measures are required to prevent galvanic corrosion.

5. Conclusions

To assess the suitability of SDSS EN 1.4501 for battery case applications, the alloy was heat treated, coated with Ag, and evaluated through microstructural and electrochemical analyses. The key findings are summarized as follows.

(1) Solution heat treatment at 1100 °C effectively removed secondary phases and produced a balanced austenite–ferrite microstructure. This controlled phase fraction resulted in more stable electrochemical behavior compared to the as-cast condition.

(2) The phase fraction of SDSS was strongly dependent on heat treatment temperature. Higher temperatures promoted grain coarsening and increased ferrite content. These changes indicate that thermal processing can be used to control the crystallographic structure of SDSS.

(3) The Ag coating preferentially oriented along the (111) plane. Although the coating itself was not influenced by the SDSS microstructure, electrical conductivity was reduced when secondary phases and high ferrite content were present. Maintaining austenite above 50 vol.% is recommended to ensure stable conductivity.

(4) The Ag coating did not prevent Cl penetration. Galvanic corrosion occurred within the SDSS matrix and was further promoted by the Ag layer. The OCP values of Ag-coated SDSS shifted to more negative potentials after heat treatment, and corrosion resistance decreased when the ferrite fraction was high.

(5) For battery case applications, controlling the SDSS phase balance is essential. A fully solution-treated microstructure with a near-equal austenite–ferrite ratio improves both electrical conductivity and corrosion resistance. With appropriate phase fraction control, SDSS EN 1.4501 can serve as a reliable battery case material.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.P., S.K., B.-H.S. and Y.K.; methodology, S.H.L. and S.L.; software, S.H.L. and S.L.; validation, S.-B.H.; formal analysis, B.-H.S.; investigation, S.K.; resources, S.K.; data curation, B.-H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.P.; writing—review and editing, Y.P.; visualization, S.-B.H.; supervision, B.-H.S.; project administration, Y.K.; funding acquisition, Y.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Korea Evaluation Institute of Industrial Technology (KEIT) (grant number K_G012002335503).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sutopo, W.; Astuti, R.W.; Purwanto, A.; Nizam, M. Commercialization Model of New Technology Lithium Ion Battery: A Case Study for Smart Electrical Vehicle. In Proceedings of the 2013 Joint International Conference on Rural Information & Communication Technology and Electric-Vehicle Technology (rICT & ICeV-T), Bandung, Bali, Indonesia, 26–28 November 2013; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Tudoroiu, R.-E.; Zaheeruddin, M.; Tudoroiu, N.; Radu, S.M.; Chammas, H. Investigations of Different Approaches for Controlling the Speed of an Electric Motor with Nonlinear Dynamics Powered by a Li-Ion Battery-Case Study. In Electric Vehicles-Design, Modelling and Simulation; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tudoroiu, N.; Zaheeruddin, M.; Tudoroiu, R.-E.; Radu, M.S.; Chammas, H. Investigations on Using Intelligent Learning Techniques for Anomaly Detection and Diagnosis in Sensors Signals in Li-Ion Battery—Case Study. Inventions 2023, 8, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, L.N.; Lee, D. The Characteristics of Laser Welding of a Thin Aluminum Tab and Steel Battery Case for Lithium-Ion Battery. Metals 2020, 10, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koleva, M.; Shi, Y.; McKenna, K.; Craig, M.; Nagarajan, A. Optimal Strategies for Hybrid Battery Storage Systems Design. Energy Technol. 2023, 11, 2300115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, L.; Li, L.; Yang, J.; Tan, R.; Shu, W.; Low, C.J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Li, C.; Zhang, Y. Industrial-Scale Nonmetal Current Collectors Designed to Regulate Heat Transfer and Enhance Battery Safety. Preprint 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valeriano, L.d.C.; Correa, E.O.; Mariano, N.A.; Robin, A.L.M.; Machado, M.A.G. Influence of the Solution-Treatment Temperature and Short Aging Times on the Electrochemical Corrosion Behaviour of Uns S32520 Super Duplex Stainless Steel. Mater. Res. 2019, 22, e20180774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Vargas, G.; Ruiz, A.; López-Morelos, V.H.; Kim, J.-Y.; González-Sánchez, J.; Medina-Flores, A. Evaluation of 475 C Embrittlement in UNS S32750 Super Duplex Stainless Steel Using Four-Point Electric Conductivity Measurements. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2021, 53, 2982–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, A.R.; Shanmugam, N.S.; Rajkumar, V.; Vishnukumar, M. Insight into the Microstructural Features and Corrosion Properties of Wire Arc Additive Manufactured Super Duplex Stainless Steel (ER2594). Mater. Lett. 2020, 270, 127680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, A.K.; Pandey, C.; Chhibber, R. Effect of Filler Metal Composition on Microstructural and Mechanical Characterization of Dissimilar Welded Joint of Nitronic Steel and Super Duplex Stainless Steel. Arch. Civil. Mech. Eng. 2022, 22, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, D.; Grosu, I.-G.; Filip, C. How Thick, Uniform and Smooth Are the Polydopamine Coating Layers Obtained under Different Oxidation Conditions? An in-Depth AFM Study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 597, 153680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, E.P.; Hwang, B.; Lee, S.; Kim, N.J.; Ahn, J. Correlation of Microstructure with Hardness and Wear Resistance of Stainless Steel Blend Coatings Fabricated by Atmospheric Plasma Spraying. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2006, 429, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Xu, J.; Chen, Z.; Guo, R.; Miao, D.; Peng, L.; Wang, Y.; Shang, S. Enhanced Electro-Conductivity and Multi-Shielding Performance with Copper, Stainless Steel and Titanium Coating onto PVA Impregnated Cotton Fabric. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2018, 29, 5624–5633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasana, E.; Westbroek, P.; Hakuzimana, J.; De Clerck, K.; Priniotakis, G.; Kiekens, P.; Tseles, D. Electroconductive Textile Structures through Electroless Deposition of Polypyrrole and Copper at Polyaramide Surfaces. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2006, 201, 3547–3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Dong, W.; Guo, Y.; Wang, K.; Shah, S.P. Advances in Multifunctional Cementitious Composites with Conductive Carbon Nanomaterials for Smart Infrastructure. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 128, 104454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhilyaev, A.P.; Shakhova, I.; Belyakov, A.; Kaibyshev, R.; Langdon, T.G. Wear Resistance and Electroconductivity in Copper Processed by Severe Plastic Deformation. Wear 2013, 305, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybalka, K.V.; Beketaeva, L.A.; Davydov, A.D. Electrochemical Behavior of Stainless Steel in Aerated NaCl Solutions by Electrochemical Impedance and Rotating Disk Electrode Methods. Russ. J. Electrochem. 2006, 42, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrini, E.; Cristiani, P.; Grattieri, M.; Santoro, C.; Li, B.; Trasatti, S. Electrochemical Behavior of Stainless Steel Anodes in Membraneless Microbial Fuel Cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2013, 161, H62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.; Ok, J.-W.; Lee, Y.-S.; Lee, S.; Je, Y.; Kim, S.; Kim, S.; Park, J.; Hong, J.; Lee, T. Impact of Ag Coating Thickness on the Electrochemical Behavior of Super Duplex Stainless Steel SAF2507 for Enhanced Li-Ion Battery Cases. Crystals 2025, 15, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, B.-H.; Kim, D.; Park, S.; Hwang, M.; Park, J.; Chung, W. Precipitation Condition and Effect of Volume Fraction on Corrosion Properties of Secondary Phase on Casted Super-Duplex Stainless Steel UNS S32750. Anti-Corros. Methods Mater. 2018, 66, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, J.-O. Super Duplex Stainless Steels. Mater. Sci. Technol. 1992, 8, 685–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, B.-H.; Kim, D.; Yoon, J.-H. Crystallization of Secondary Phase on Super-Duplex Stainless Steel SAF2507: Advanced Li-Ion Battery Case Materials. Crystals 2024, 14, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiente Bermejo, M.A.; Thalavai Pandian, K.; Axelsson, B.; Harati, E.; Kisielewicz, A.; Karlsson, L. Microstructure of Laser Metal Deposited Duplex Stainless Steel: Influence of Shielding Gas and Heat Treatment. Weld. World 2021, 65, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köse, C. Effect of Heat Input and Post Weld Heat Treatment on the Texture, Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Laser Beam Welded AISI 317L Austenitic Stainless Steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 855, 143966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Chung, W.; Shin, B.-H. Effects of the Volume Fraction of the Secondary Phase after Solution Annealing on Electrochemical Properties of Super Duplex Stainless Steel UNS S32750. Metals 2023, 13, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.; Lee, W.G.; Kim, Y.H.; Jang, H. Surface Roughness and the Corrosion Resistance of 21Cr Ferritic Stainless Steel. Corros. Sci. 2012, 63, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, B.; Lee, S.; Ahn, J. Effect of Oxides on Wear Resistance and Surface Roughness of Ferrous Coated Layers Fabricated by Atmospheric Plasma Spraying. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2002, 335, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friel, J.J. ASTM Standards in Microscopy and Microanalysis. In Proceedings of the Conference Series-Institute of Physics, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000; Institute of Physics: London, UK, 1999; Volume 165, pp. 399–400. [Google Scholar]

- Makhdoom, M.A.; Ahmad, A.; Kamran, M.; Abid, K.; Haider, W. Microstructural and Electrochemical Behavior of 2205 Duplex Stainless Steel Weldments. Surf. Interfaces 2017, 9, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Voort, G.F. Measuring Inclusion Content by ASTM E 1245. Clean Steel 1997, 5, 58–67. [Google Scholar]

- Rajesh, D.; Sunandana, C.S. XRD, Optical and AFM Studies on Pristine and Partially Iodized Ag Thin Film. Results Phys. 2012, 2, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.K.; Paul, T.C.; Dutta, S.; Hossain, M.N.; Mia, M.N.H. XRD Peak Profile and Optical Properties Analysis of Ag-Doped h-MoO 3 Nanorods Synthesized via Hydrothermal Method. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2020, 31, 1768–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharyya, S.G.; Khandelwal, A.; Kain, V.; Kumar, A.; Samajdar, I. Surface Working of 304L Stainless Steel: Impact on Microstructure, Electrochemical Behavior and SCC Resistance. Mater. Charact. 2012, 72, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimoto, M.; Muto, I.; Sugawara, Y. Review―Understanding and Controlling the Electrochemical Properties of Sulfide Inclusions for Improving the Pitting Corrosion Resistance of Stainless Steels. Mater. Trans. 2023, 64, 2051–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standard, A. Standard Test Method for Conducting Cyclic Potentiodynamic Polarization Measurements to Determine the Corrosion Susceptibility of Small Implant Devices; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Soria, L.; Herrera, E.J. A Reliable Technique to Determine Pitting Potentials of Austenitic Stainless Steels by Potentiodynamic Methods. Weld. Int. 1992, 6, 959–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, M.H.F.; Rocha, F.C.; Medeiros-Junior, R.A.; Helene, P. Corrosion Potential: Influence of Moisture, Water-Cement Ratio, Chloride Content and Concrete Cover. Rev. IBRACON Estrut. E Mater. 2017, 10, 864–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacs, H.S.; Ishikawa, Y. Current and Potential Transients during Localized Corrosion of Stainless Steel. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1985, 132, 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, C.A.; Sokolowski, A. Development of UNS S 32760 Super-Duplex Stainless Steel Produced in Large Diameter Rolled Bars. Rem Rev. Esc. Minas 2013, 66, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Topolska, S.; Łabanowski, J. Effect of Microstructure on Impact Toughness of Duplex and Superduplex Stainless Steels. J. Achiev. Mater. Manuf. Eng. 2009, 36, 142–149. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Paulraj, P.; Garg, R. Effect of Intermetallic Phases on Corrosion Behavior and Mechanical Properties of Duplex Stainless Steel and Super-Duplex Stainless Steel. Adv. Sci. Technol. Res. J. 2015, 9, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehovnik, F.; Arzensek, B.; Arh, B.; Skobir, D.; Pirnar, B.; Zuzek, B. Microstructure Evolution in SAF 2507 Super Duplex Stainless Steel. Mater. Technol 2011, 45, 339–345. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, M.; Casteletti, L.C. Sigma Phase Morphologies in Cast and Aged Super Duplex Stainless Steel. Mater. Charact. 2009, 60, 792–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amatsuka, S.; Nishimoto, M.; Muto, I.; Kawamori, M.; Takara, Y.; Sugawara, Y. Micro-Electrochemical Insights into Pit Initiation Site on Aged UNS S32750 Super Duplex Stainless Steel. NPJ Mater. Degrad. 2023, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, J.O.; Wilson, A. Influence of Isothermal Phase Transformations on Toughness and Pitting Corrosion of Super Duplex Stainless Steel SAF 2507. Mater. Sci. Technol. 1993, 9, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linton, V.M.; Laycock, N.J.; Thomsen, S.J.; Klumpers, A. Failure of a Super Duplex Stainless Steel Reaction Vessel. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2004, 11, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H.-Y.; Jang, M.-H.; Lee, T.-H.; Moon, J. Interpretation of the Relation between Ferrite Fraction and Pitting Corrosion Resistance of Commercial 2205 Duplex Stainless Steel. Corros. Sci. 2014, 89, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzadeh, H.; Cabrera, J.M.; Najafizadeh, A.; Calvillo, P.R. EBSD Study of a Hot Deformed Austenitic Stainless Steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2012, 538, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeid, T.; Abdollah-Zadeh, A.; Shibayanagi, T.; Ikeuchi, K.; Assadi, H. EBSD Investigation of Friction Stir Welded Duplex Stainless Steel. World Acad. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2010, 61, 376–379. [Google Scholar]

- Michalska, J.; Chmiela, B. Phase Analysis in Duplex Stainless Steel: Comparison of EBSD and Quantitative Metallography Methods. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2014; Volume 55, p. 012010. [Google Scholar]

- Fréchard, S.; Martin, F.; Clément, C.; Cousty, J. AFM and EBSD Combined Studies of Plastic Deformation in a Duplex Stainless Steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2006, 418, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, F.; Liu, M.; Zhang, W.; Yu, X.; Da, W. Effect of Nanodiamond Content in the Plating Solution on the Corrosion Resistance of Nickel–Nanodiamond Composite Coatings Prepared on Annealed 45 Carbon Steel. Coatings 2022, 12, 1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.K.; Grover, A.K.; Dey, G.K.; Totlani, M.K. Nanocrystalline Ni–Cu Alloy Plating by Pulse Electrolysis. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2000, 126, 48–63. [Google Scholar]

- Pettersson, N.; Pettersson, R.F.A.; Wessman, S. Precipitation of Chromium Nitrides in the Super Duplex Stainless Steel 2507. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2015, 46, 1062–1072. [Google Scholar]

- Köse, C.; Topal, C. Dissimilar Laser Beam Welding of AISI 2507 Super Duplex Stainless to AISI 317L Austenitic Stainless Steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 862, 144476. [Google Scholar]

- Fande, A.W.; Taiwade, R. V Welding of Super Duplex Stainless Steel and Austenitic Stainless Steel:# Xd; Influence and Role of Bicomponent Fluxes. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2023, 38, 434–448. [Google Scholar]

- Vignal, V.; Delrue, O.; Heintz, O.; Peultier, J. Influence of the Passive Film Properties and Residual Stresses on the Micro-Electrochemical Behavior of Duplex Stainless Steels. Electrochim. Acta 2010, 55, 7118–7125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.H.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, H.G.; Kim, J.G. A Study on the Quantitative Determination of Through-Coating Porosity in PVD-Grown Coatings. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2004, 233, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, M.; Lu, Y.; Akbar, M.; Lei, L.; Jing, S.; Tao, Y. Advances in Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Technologies: Lowering the Operating Temperatures through Material Innovations. Mater. Today Energy 2024, 44, 101633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, T.; Ischia, G.; Naclerio, F.; Ipek, R.; Bandini, M.; Molinari, A.; Benedetti, M. Unveiling the Impact of Nitriding and PVD Coating on the Fatigue Properties of L-PBF Maraging Steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2025, 935, 148365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, S.P.; Abrão, A.M.; da Silva, E.R.; Câmara, M.A. Enhanced Wear Resistance and Frictional Behavior of AISI H13 Tool Steel through In-Situ Urea-Assisted EDM Nitriding and TiAlN PVD Coating. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 138, 2459–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanini, M.; Searle, S.; Vanmunster, L.; Vanmeensel, K.; Vrancken, B. Local Microstructure Engineering of Super Duplex Stainless Steel via Dual Laser Powder Bed Fusion–an Analytical Modeling and Experimental Approach. Addit. Manuf. 2025, 112, 104994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).