Abstract

In this work, two configurations of Ti/HAp functionally graded coatings were fabricated on Ti–6Al–4V alloy substrates using detonation spraying. The coatings differed in the number and sequence of Ti and hydroxyapatite (HAp) deposition cycles, resulting in distinct gradient architectures: Configuration 1 incorporated a sharper transition from the Ti-rich base to the HAp-rich surface, whereas Configuration 2 featured a smoother and more gradual compositional gradient. The microstructure and elemental distribution were examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). Both configurations exhibited well-defined gradient layering, with titanium concentrated near the coating–substrate interface and an increased Ca and P content toward the upper bioceramic region. Raman spectroscopy confirmed the preservation of hydroxyapatite as the main phase, showing a characteristic 961 cm−1 band. Adhesion strength measured according to ASTM C633-13 was 45.78 ± 4.4 MPa for Configuration 1 and 52.32 ± 6.7 MPa for Configuration 2, both significantly exceeding the minimum required 15 MPa. The findings demonstrate that detonation-sprayed Ti/HAp gradient coatings provide strong adhesion and stable bioceramic surfaces, making them promising for metal implant applications.

1. Introduction

Implants used in traumatology, orthopedics and maxillofacial surgery are complex and labor-intensive to manufacture. Due to the fact that the implant material must meet a number of important criteria: bending strength and fatigue resistance, flexibility, complex shape, this sharply narrows the range of available materials. Titanium and its alloys are currently widely used in load-bearing dental and orthopedic implant materials due to their suitable mechanical properties and high corrosion resistance [1,2,3,4,5]. Titanium alloys are bioinert materials, since no direct chemical bond is formed between their surface and bone tissue after implantation [6]. Currently, many research teams are developing promising methods for modifying the surface of metal implants in order to prevent the release of alloying components and simultaneously increase osseointegration. To improve the osseointegration of titanium implants, calcium phosphate coatings are used, among which hydroxyapatite (HAp) is the most popular due to its chemical and mineralogical similarity to bone tissue [7,8,9,10,11]. Despite their pronounced bioactivity, hydroxyapatite—based coatings exhibit limiting mechanical characteristics, such as brittleness and low wear resistance, which significantly limits their widespread use in medical practice [12]. In this regard, special attention is paid to the development of Ti–HAp composite systems, in which titanium (Ti) acts as an effective strengthening phase, improving performance while maintaining the bioactivity of the coating. When Ti particles are added to HAp, the mechanical properties of composite coatings are significantly improved compared to HAp coatings [13]. The addition of Ti particles to HAp can also reduce the mismatch in thermal expansion coefficients between the coatings and the metal substrates, thereby decreasing the thermal stress inside the coatings and improving the coating–substrate adhesion [14].

It should be noted that there is a problem in the field of practical materials science, since as the thickness of the calcium phosphate coating increases (up to 150 μm), its bioactivity, osteoinduction and osteoconduction capabilities increase, but its mechanical strength and adhesion to the substrate decrease. From a fundamental point of view, enhanced osseointegration of the implant reduces the risk of biomechanical failure (loosening) of the implant/bone interface. The problem of macroscopic/interphase boundaries can be solved using functionally graded materials (FGM), which provide a continuous change in mechanical, chemical, and physical properties [15,16]. Functionally graded materials are unique and promising composite materials whose composition/components and/or microstructure gradually change in coatings according to a specified profile or sequence, in one or more directions [17]. In particular, with regard to the biomedical sector, FGMs are new materials for both orthopedic and dental applications [18]. Ha and Ti can be combined to create an excellent functionally graded material. Since the surface layer consists of HAp, the resulting functionally graded coating demonstrates excellent biocompatibility and the ability to create new bone tissue. The excellent mechanical strength of functionally graded coatings is provided by the Ti phase.

Given the high importance of biocompatible coatings, choosing the appropriate coating technology is therefore an important aspect. The most commonly used methods are thermal spraying, sol–gel synthesis, micro-arc oxidation, etc. [19,20,21], with gas-thermal methods, including plasma spraying (PS), high-velocity oxygen fuel (HVOF) spraying, and cold spraying, becoming particularly widespread [22,23,24]. However, limited adhesive strength and low crystallinity of coatings remain serious factors hindering their practical application, which necessitates the development of new technological approaches. Among gas-thermal methods, plasma spraying (PS) [25] has become the most widespread in industrial practice. It is widely used for applying hydroxyapatite coatings to implants made of titanium and its alloys, having proven itself as an effective and economically viable method of surface modification. However, HAp coatings obtained by PS are typically characterized by low crystallinity, the presence of secondary phases, and limited adhesive strength, which is associated with the extremely high temperatures of the plasma torch, causing partial melting and thermal degradation of hydroxyapatite particles [26]. As a result, such coatings demonstrate instability under cyclic loads: in tests in Ringer’s solution, they completely peeled off after ~1 million cycles [27].

In contrast, detonation spraying (DS) is a promising method for producing biocompatible coatings based on hydroxyapatite [28]. The key advantage of DS is its pulsed nature, which prevents overheating of the substrate and minimizes the destruction of the initial phases of the sprayed material [29]. Moreover, the significantly higher particle velocity (around 800–1000 m/s) compared to PS and HVOF ensures dense compaction of the coating and strong adhesion to the substrate [30]. As a result, coatings obtained by the DS method demonstrate high crystallinity, an optimal Ca/P ratio of ≈1.67 [31], and excellent fatigue resistance: they remained stable even after 10 million cycles in Ringer’s solution [27]. An additional advantage is the possibility of forming functionally graded coatings, which opens up prospects for the creation of implants with improved performance characteristics. Despite these advantages, the available literature primarily focuses on homogeneous HAp coatings, while systematic studies on Ti/HAp functionally graded coatings produced by DS—particularly with controlled transitions between metallic and bioceramic layers—are still limited. The novelty of this work lies in developing and comparing two distinct gradient architectures formed by varying the sequence and number of Ti and HAp deposition cycles, and in evaluating how these configurations influence the coating’s microstructure and adhesion behavior.

The aim of this study is to fabricate and compare two configurations of Ti/HAp functional gradient coatings produced by detonation spraying, and to evaluate their microstructure and adhesion strength.

2. Materials and Methods of Research

In this study, Ti–6Al–4V titanium alloy was used as a substrate for applying Ti/HAp-based coatings. Before coating, the titanium substrates were subjected to air abrasive treatment with electrocorundum powder with a particle size of 100–200 μm at an air pressure of 0.4–0.5 MPa. After that, the surface was cleaned by ultrasonic treatment in ethanol for 10 min to remove technological contaminants.

2.1. Characterization of Powders

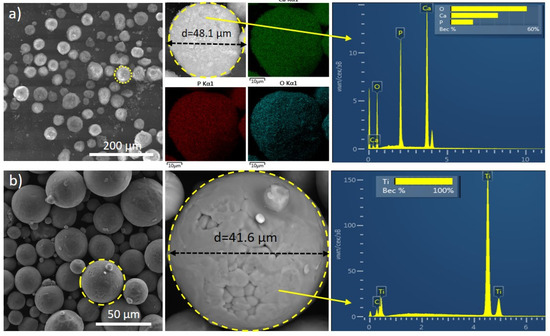

Spherical HAp powder with a particle diameter ranging from 15 to 55 micrometers, supplied by Medicoat, Mägenwil, Switzerland, was selected for the coatings. As can be seen in the image (Figure 1a), HAp powder contains three main elements: calcium (Ca), phosphorus (P) and oxygen (O). These elements are characteristic of the chemical structure of hydroxyapatite Ca5(PO4)3OH. Spherical titanium powder (CL42Ti) (ASTM F67) (Concept Laser, Lichtenfels, Germany) with a particle diameter in the range of 15–45 μm (Figure 1b) was used as the second reinforcing phase for hydroxyapatite.

Figure 1.

Morphology and EDS analysis of HAp (a) and Ti (b) powders.

2.2. Coating by Detonation Spraying

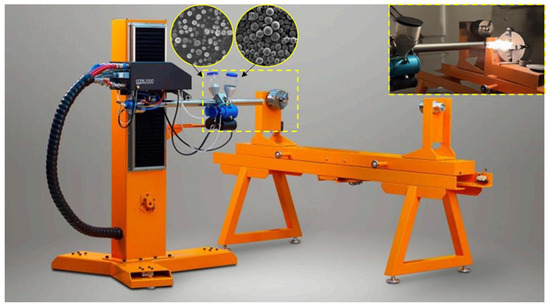

A computer-controlled CCDS-2000 detonation spraying (Siberian Technologies of Protective Coatings LTD, Novosibirsk, Russia) unit equipped with two automatic dispensers loaded with hydroxyapatite and titanium powders was used for coating application (Figure 2). The use of an automated control system ensured the stability of the process parameters, a process which is especially important when forming gradient coatings with specified properties. During the detonation spraying process, a mixture of combustible gases (acetylene C2H2 as fuel and oxygen O2 as oxidizer) was fed into the combustion chamber and ignited by a spark plug. The resulting detonation wave accelerated the powder particles to supersonic speeds, ensuring their deep penetration into the substrate surface and the formation of a dense, low-porosity layer. At the same time, the substrate temperature remained relatively low, which prevented its thermal deformation or structural change, which is especially important when processing precision parts. Technical parameters of the installation: barrel length—450 mm, inner diameter—26 mm; powder purging and transport were carried out using nitrogen (N2); the volume fraction of the gas mixture was 65% with a molar ratio of O2/C2H2 = 2.61; distance from the nozzle to the substrate—150 mm; detonation frequency—4 Hz (4 shots per second).

Figure 2.

General view of the CCDS2000 detonation unit [11].

Two types of Ti/HAp gradient coatings were produced on the Ti–6Al–4V alloy using detonation spraying. In Regime No. 1, the number of titanium (Ti) spraying cycles gradually decreased from 8 to 2 in subsequent layers, while the number of hydroxyapatite (HAp) cycles increased from 4 to 12. This approach created a progressively enriched HAp layer and a well-defined gradient structure. In Regime No. 2, the number of Ti cycles decreased from 6 to 2, and the number of HAp cycles increased from 2 to 10. The exact sequence of Ti and HAp deposition cycles for each regime is summarized in Table 1. Each cycle consisted of the deposition of one material followed by purging and chamber preparation for the next component.

Table 1.

Technological parameters of detonation spraying of Ti/HAp gradient coatings.

All detonation spraying procedures were carried out in a certified explosion-proof chamber equipped with forced ventilation and acoustic shielding. The handling of combustible gases (C2H2 and O2) followed industrial safety regulations, including leak testing and automatic shut-off systems. Operators used protective clothing, face shields, heat-resistant gloves and hearing protection. The CCDS2000 unit is equipped with interlock mechanisms preventing accidental ignition. These measures ensured safe operation during all experiments.

3. Coating Characterizations

The surface morphology and microstructure of the cross-section of the coatings were analyzed using a scanning electron microscope with field emission (SEM, TESCAN MIRA3 LMH, Brno, Czech Republic) equipped with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS). Structural characterization was performed by Raman spectroscopy using an AFM-Raman Solver spectrometer (NT-MDT, Russia) in the range of 100–2500 cm−1, more information can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

The adhesive strength of the gradient coatings was determined in accordance with ASTM C633 [32]. For testing, coated samples were bonded to similar uncoated samples that had been sandblasted beforehand to ensure uniform surface roughness and improve adhesion. 3M Scotch-Weld 2214 epoxy adhesive, which has high strength and heat resistance, was used as the adhesive. The adhesive was cured at 120 °C for 60 min at a contact pressure of 70 N/cm2, which ensured a reliable bond between the test samples. Adhesion tests were performed by tearing the bonded sets on an Instron 8801 universal testing machine (Instron, Norwood, MA, USA) at a cross-sectional speed of 0.015 mm/s. During the tests, the maximum load at which the joint failed was recorded. The adhesive strength (σ, MPa) was calculated using the standard formula:

where: σ—adhesive strength of the coating, MPa;

σ = F/A

F—maximum breaking force during testing, N;

A—area of the bonded surface, mm2.

4. Results and Discussion

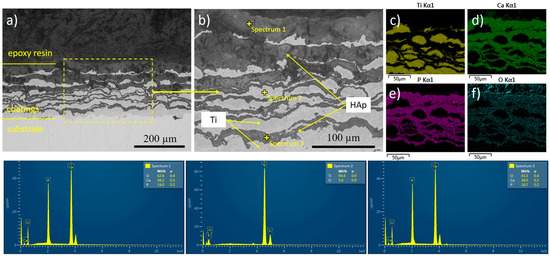

The morphology and microstructure of the gradient Ti/HAp coatings were examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Cross-sectional SEM images (Figure 3) reveal a layered architecture with alternating contrast, indicative of compositional heterogeneity across the coating thickness. In the general view (Figure 3a), the coating appears continuous and well-adhered to the substrate, without visible defects such as pores or delamination at the interface. The magnified fragment (Figure 3b) demonstrates two distinct regions: dark areas enriched in hydroxyapatite (Ca, O, and P) and grey regions with a higher titanium (Ti) content. Energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) analysis supports these observations, showing that spectra 1 and 3 are dominated by Ca and P, while spectrum 2 indicates a predominance of Ti. These results confirm the formation of a functional gradient structure, where the coating gradually transitions from Ti-rich layers at the substrate to Ca/P-rich layers at the surface.

Figure 3.

SEM images showing the cross-sectional morphology No. 1 sample: (a,b) BSE image; (c–f) elemental maps of Ti, Ca, P, O, respectively.

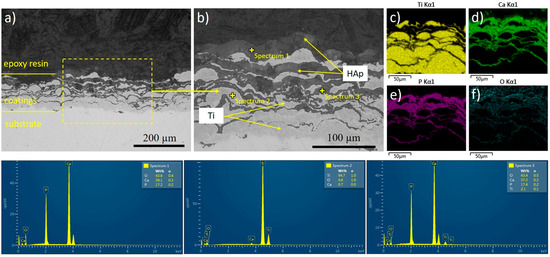

The cross-sectional microstructure of the coating produced by detonation spraying under regime No. 2 is presented in Figure 4. The enlarged fragment (Figure 4b) clearly shows light areas enriched with titanium and dark areas containing hydroxyapatite (Ca, O and P), which confirms the composite and functionally graded nature of the coating. Regime No. 2 was formed by reducing the number of titanium shots (from 6 to 2) and moderately increasing the number of hydroxyapatite shots (from 2 to 10). This scheme allowed for a smoother transition from the metal base to the bioceramic layer. Unlike regime No. 1, where there is a more abrupt transition to an HAp-enriched structure, regime No. 2 ensures that a significant concentration of titanium is maintained throughout the thickness of the coating, which contributes to its mechanical strength and stability.

Figure 4.

SEM images showing the cross-sectional morphology No. 2 sample: (a,b) BSE image; (c–f) elemental maps of Ti, Ca, P, O, respectively.

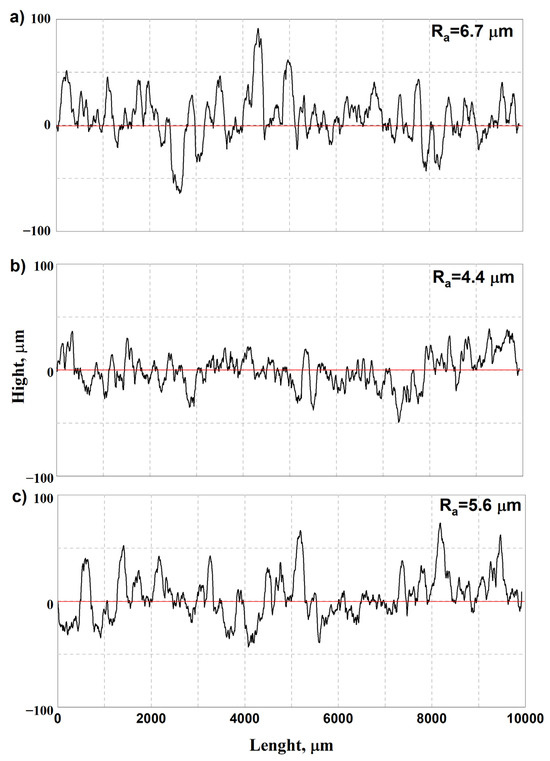

Figure 5 shows the surface roughness profiles for the substrate after shot blasting and for the coatings produced in modes No. 1 and No. 2. The shot-blasted substrate (a) exhibits a highly developed relief with Ra = 6.7 µm, resulting from the formation of numerous peaks and valleys that enhance mechanical interlocking and, consequently, adhesion to subsequently applied layers. In contrast, the coating obtained in mode No. 1 (b) demonstrates a significantly smoother topography with reduced roughness (Ra = 4.4 µm), which is attributed to the deposition sequence of Ti and HAp layers that effectively fill surface irregularities and form a more uniform upper surface. The coating produced in mode No. 2 (c) has an intermediate roughness level (Ra = 5.6 µm), indicating partial preservation of the underlying surface features due to differences in the thermal and structural formation mechanisms during spraying. Overall, both coating modes reduce surface roughness compared to the initial substrate, while mode No. 1 provides the smoothest surface among the studied variants [33].

Figure 5.

Profilometric roughness profiles: (a) shot-blasted substrate Ti–6Al–4V, (b) coating deposited in mode No. 1, and (c) coating deposited in mode No. 2.

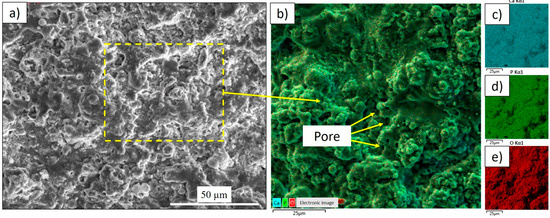

The surface morphology of the coating produced by detonation spraying under regime No. 1 was investigated, and the corresponding results are presented in Figure 6. The coating exhibits a distinctly developed microrelief with pronounced roughness and the presence of micropores in the micrometer range, as evidenced by the SEM images (Figure 6a,b). Such a topography substantially increases the effective surface area and is considered a critical factor for osteointegration, as it provides favorable conditions for the initial adhesion, subsequent spreading, and proliferation of osteogenic cells [34]. Elemental mapping (Figure 6c–e) further confirms the uniform distribution of calcium, phosphorus, and oxygen across the coating surface, indicating the formation of a hydroxyapatite-rich layer. The chemical composition of this layer closely resembles the mineral phase of natural bone tissue, thereby ensuring high bioactivity and biocompatibility of the coating.

Figure 6.

SEM images showing the morphology of the surface of sample No. 1: (a,b) and BSE images; (c–e) maps of the elements Ca, P, O, respectively.

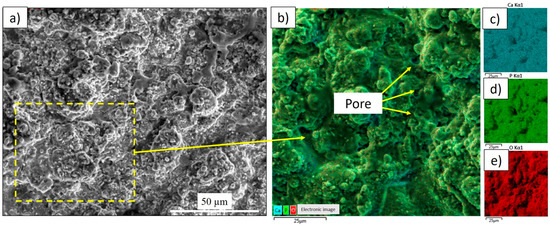

Representative SEM micrographs (Figure 7a,b) and elemental mapping results (Figure 7c–e) illustrate the surface microstructure of the gradient coating obtained under regime No. 2. The general SEM view (Figure 7a) reveals a well-developed rough surface with uniformly distributed micropores in the micrometer range, while the magnified image (Figure 7b) provides detailed visualization of the microrelief and clearly identifies individual pores that enlarge the effective contact area, thereby enhancing the potential for biological cell adhesion. The combination of this micro-rough architecture with the homogeneous distribution of calcium, phosphorus, and oxygen across the surface (Figure 7c–e) contributes to increased wettability and surface energy, which in turn establishes favorable conditions for the attachment, proliferation, and subsequent differentiation of osteogenic cells.

Figure 7.

SEM images showing the morphology of the surface of sample No. 2: (a,b) and BSE images; (c–e) maps of the elements Ca, P, O, respectively.

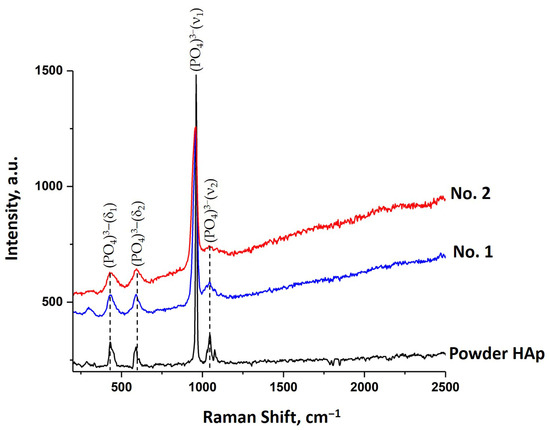

The Raman scattering spectra of the Ti/HAp gradient coatings produced by detonation spraying in regimes No. 1 and No. 2, along with that of the initial hydroxyapatite powder, are presented in Figure 8. All samples show a distinct intense band in the 961 cm−1 region, corresponding to the symmetric P–O stretching vibration mode (ν1) in the PO43− tetrahedron, which is characteristic of hydroxyapatite and indicates that it remains the main phase in the coatings. The narrow shape and high intensity of this line indicate that the crystallinity of hydroxyapatite is preserved after spraying, which is consistent with the literature data [35]. Additionally, the spectra show vibrational modes ν2 and ν4, as well as asymmetric stretching ν3 in the region of 1045–1033 cm−1; the recorded shift of the ν3 band compared to the original powder indicates structural distortions and partial carbonization of the apatite lattice caused by high-energy exposure during coating formation. It is important to note that variations in the intensity and position of the bands in coatings obtained under different sputtering conditions reflect changes in the growth morphology and size of crystallites: an increase in the degree of atomic disorder leads to a decrease in their average size (nanometer range), which is expressed in the broadening and partial shift of spectral lines. Thus, Raman spectroscopy confirms that despite local structural modifications, the coatings retain hydroxyapatite as the dominant phase with a satisfactory degree of crystallinity, which is an important factor in ensuring their biological activity and biocompatibility when used as functional layers of medical implants.

Figure 8.

Spectrogram of gradient coating combination scattering.

The results of the adhesion strength evaluation demonstrate a marked enhancement in the adhesion strength of the coating in sample No. 2 compared with sample No. 1. The adhesive strength of the coating in sample No. 1 was 45.78 ± 4.4 MPa, which indicates stable adhesion to the substrate, but with some variability due to the spraying method used. In turn, sample No. 2 demonstrated an adhesive strength of 52.32 ± 6.7 MPa, which is 6.54 MPa higher than that of sample No. 1, indicating better adhesion of the coating to the substrate. This is due to a smoother transition from titanium to hydroxyapatite and improved interlayer adhesion. The adhesion strength values obtained in this study exceed the standard value of 15 MPa established in accordance with ISO 13779-2 [36]. This confirms that coatings obtained by detonation spraying with a gradient structure have high adhesive strength, which indicates good adhesion to the substrate and stability of the coating when operated under mechanical loads.

5. Conclusions

Our results showed that the gradient layer plays a key role in improving the adhesive properties of Ti/HAp composite coatings on Ti–6Al–4V titanium alloy. The coatings have a pronounced gradient structure, where titanium is localised in the lower layers, providing mechanical strength and adhesion, while hydroxyapatite in the upper layers forms a biocompatible layer that promotes osseointegration. The Raman scattering spectra showed an intense band at 961 cm−1, corresponding to the P–O stretching mode (ν1) in PO43−, which confirms the preservation of hydroxyapatite as the main phase of the coating. The coating obtained in regime No. 1 has a more pronounced gradient structure, while the coating in regime No. 2 shows a smoother transition between the titanium and hydroxyapatite layers. Adhesion strength assessment according to ASTM C633-13 showed values of 45.78 ± 4.4 MPa for coating No. 1 and 52.32 ± 6.7 MPa for coating No. 2, which significantly exceeds the minimum required 15 MPa. These results confirm that coatings with a functional gradient structure obtained by detonation spraying have high adhesion strength to the substrate, which makes them promising for use in medical implants. Further research will focus on evaluating long-term in vitro and in vivo performance, optimizing gradient architecture for enhanced bioactivity, and studying the influence of detonation spraying parameters on coating stability and degradation behavior.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/coatings15121418/s1, Table S1: Deposition sequence—Regime No. 1 Layer No; Table S2: Deposition sequence—Regime No. 2: Layer No.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K. and D.B. (Daryn Baizhan); methodology, D.B. (Dastan Buitkenov); software, N.M.; validation, D.B. (Daryn Baizhan) and D.B. (Dastan Buitkenov); formal analysis, N.M.; investigation, D.B. (Dastan Buitkenov); resources, A.K.; data curation, N.M.; writing—original draft preparation, D.B. (Daryn Baizhan); writing—review and editing, A.K.; visualization, D.B. (Dastan Buitkenov); supervision, D.B. (Daryn Baizhan); project administration, A.K.; funding acquisition, A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been funded by the Committee of Science of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan. (Grant No. BR24992862).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Aidar Kengesbekov and Nazerke Muktanova were employed by the company PlasmaScience LLP. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Deram, V.; Minichiello, C.; Vannier, R.-N.; Le Maguer, A.; Pawlowski, L.; Murano, D. Microstructural characterizations of plasma sprayed hydroxyapatite coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2003, 166, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Komasa, S.; Hashimoto, Y.; Hontsu, S.; Okazaki, J. In vitro and in vivo osteogenic activity of titanium implants coated by pulsed laser deposition with a thin film of fluoridated hydroxyapatite. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cizek, J.; Khor, K.A.; Prochazka, Z. Influence of spraying conditions on thermal and velocity properties of plasma sprayed hydroxyapatite. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2007, 27, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Ma, W.; Li, D.; Wang, T.; Liu, B. Enhanced osseointegration of titanium implants in a rat model of osteoporosis using multilayer bone mesenchymal stem cell sheets. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017, 14, 5717–5726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohseni, E.; Zalnezhad, E.; Bushroa, A.R. Comparative investigation on the adhesion of hydroxyapatite coating on Ti–6Al–4V implant: A review paper. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2014, 48, 238–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, B.; Asadi, E.; Lewis, G. Deposition methods for microstructured and nanostructured coatings on metallic bone implants: A review. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 2017, 5812907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, A.A.; Yakovlev, V.I.; Legostaeva, E.V.; Sitnikov, A.A.; Sharkeev, Y.P. The effect of the granulometric composition of a hydroxyapatite powder on the structure and phase composition of coatings deposited by the detonation gas spraying technique. Russ. Phys. J. 2013, 55, 1284–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kweh, S.W.K.; Khor, K.A.; Cheang, P. High temperature in-situ XRD of plasma sprayed HA coatings. Biomaterials 2002, 23, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, S. Coatings on orthopedic implants to overcome present problems and challenges: A focused review. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 45, 5269–5276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Thouas, G.A. Metallic Implant Biomaterials. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2015, 87, 1–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagdoldina, Z.; Kot, M.; Baizhan, D.; Buitkenov, D.; Sulyubayeva, L. Influence of Detonation Spraying Parameters on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Hydroxyapatite Coatings. Materials 2024, 17, 5390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, S.; Gonciarz, W.; Belka, R.; Góral, A.; Chmiela, M.; Lechowicz, Ł.; Kaca, W.; Żórawski, W. Plasma-Sprayed Hydroxyapatite Coatings and Their Biological Properties. Coatings 2022, 12, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Xia, L.; Zhong, B.; Wen, G.; Song, L.; Wang, X. Effect of milling conditions on the properties of HA/Ti feedstock powders and plasma-sprayed coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2014, 251, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali Bidakhavidi, M.; Omidvar, H.; Zamani, A.; Aghazadeh Mohandesi, J.; Jalali, H. Characterization, wear behavior and biocompatibility of HA/Ti composite and functionally graded coatings deposited on Ti−6Al−4V substrate by mechanical coating technique. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2024, 34, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholamzadeh, M.; Karimi, F.; Gholamzadeh, N.; Sadrnezhaad, S.K.; Yousefi, H. The effect of heat treatment on the microstructure and mechanical properties of plasma-sprayed functionally graded hydroxyapatite/titanium coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 513, 132495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khor, K.A.; Gu, Y.W.; Quek, C.H.; Cheang, P. Plasma spraying of functionally graded hydroxyapatite/Ti–6Al–4V coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2003, 168, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, Y.; Kaysser, W.A.; Rabin, B.H.; Kawasaki, A.; Ford, R.G. Functionally Graded Materials: Design, Processing, and Applications; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Luginina, M.; Angioni, D.; Montinaro, S.; Orrù, R.; Cao, G.; Sergi, R.; Bellucci, D.; Cannillo, V. Hydroxyapatite/bioactive glass functionally graded materials (FGM) for bone tissue engineering. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2020, 40, 4623–4634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.H.; Tsao, S.Y.; Cheng, T.C.; Shieh, J.; Yang, J.Y. Effect of morphologies of hydroxyapatite powders on thermal sprayed hydroxyapatite coatings. Surf. Interfaces 2025, 60, 105948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.-M.; Troczynski, T.; Tseng, W.J. Water-based sol–gel synthesis of hydroxyapatite: Process development. Biomaterials 2001, 22, 1721–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaid, T.H.; Ramesh, S.; Yusof, F.; Basirun, W.J.; Ching, Y.C.; Chandran, H.; Ramesh, S.; Krishnasamy, S. Micro-arc oxidation of bioceramic coatings containing eggshell-derived hydroxyapatite on titanium substrate. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 18371–18381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, Y.C.; Doyle, C.; Clyne, T.W. Plasma sprayed hydroxyapatite coatings on titanium substrates Part 1: Mechanical properties and residual stress levels. Biomaterials 1998, 19, 2015–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardali, M.; SalimiJazi, H.R.; Karimzadeh, F.; Luthringer, B.; Blawert, C.; Labbaf, S. Comparative study on microstructure and corrosion behavior of nanostructured hydroxyapatite coatings deposited by high velocity oxygen fuel and flame spraying on AZ61 magnesium based substrates. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 465, 614–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henao, J.; Giraldo-Betancur, A.L.; Poblano-Salas, C.A.; Forero-Sossa, P.A.; Espinosa-Arbelaez, D.G.; Gonzalez, J.V.; Corona-Castuera, J. On the deposition of cold-sprayed hydroxyapatite coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 476, 130289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levingstone, T.J.; Ardhaoui, M.; Benyounis, K.; Looney, L.; Stokes, J.T. Plasma sprayed hydroxyapatite coatings: Understanding process relationships using design of experiment analysis. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2015, 283, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Marquis, P.M. Effect of heat treatment on the microstructure of plasma-sprayed hydroxyapatite coating. Biomaterials 1993, 14, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gledhill, H.; Turner, I.G.; Doyle, C. In vitro fatigue behaviour of vacuum plasma and detonation gun sprayed hydroxyapatite coatings. Biomaterials 2001, 22, 1233–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klyui, N.I.; Chornyi, V.S.; Zatovsky, I.V.; Tsabiy, L.I.; Buryanov, A.A.; Protsenko, V.V.; Gryshkov, O. Properties of gas detonation ceramic coatings and their effect on the osseointegration of titanium implants for bone defect replacement. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 25425–25439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baizhan, D.; Sagdoldina, Z.; Buitkenov, D.; Kambarov, Y.; Nabioldina, A.; Zhumabekova, V.; Bektasova, G. Study of the Structural-Phase State of Hydroxyapatite Coatings Obtained by Detonation Spraying at Different O2/C2H2 Ratios. Crystals 2023, 13, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kengesbekov, A.; Sagdoldina, Z.; Torebek, K.; Baizhan, D.; Kambarov, Y.; Yermolenko, M.; Abdulina, S.; Maulet, M. Synthesis and Formation Mechanism of Metal Oxide Compounds. Coatings 2022, 12, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khvostov, M.V.; Bulina, N.V.; Zhukova, N.A.; Morenkova, E.G.; Rybin, D.K.; Makarova, S.V.; Leonov, S.V.; Gorodov, V.S.; Ulianitsky, V.Y.; Tolstikova, T.G. A study on biological properties of titanium implants coated with multisubstituted hydroxyapatite. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 34780–34792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C633-13; Standard Test Method for Adhesive Strength of Thermal Spray Coatings. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2013.

- Gao, C.; Wang, Z.; Jiao, Z.; Wu, Z.; Guo, M.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, P. Enhancing antibacterial capability and osseointegration of polyetheretherketone (PEEK) implants by dual-functional surface modification. Mater. Des. 2021, 205, 109733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakimzhanov, D.; Rakhadilov, B.; Sulyubayeva, L.; Dautbekov, M. Influence of Pulse-Plasma Treatment Distance on Structure and Properties of Cr3C2-NiCr-Based Detonation Coatings. Coatings 2023, 13, 1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, L.F., Jr.; Tronco, M.C.; Escobar, C.F.; Rocha, A.S.; Santos, L.A.L. Painting method for hydroxyapatite coating on titanium substrate. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 14806–14815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 13779-2:2018; Implants for Surgery—Hydroxyapatite—Part 2: Thermally Sprayed Coatings of Hydroxyapatite. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).