Abstract

Polymer composite coatings are promising for tribological protection, with stable transfer films being key to their friction-reducing and anti-wear performance, yet the mechanism by which rare-earth compounds, known to enhance polymer tribological properties, regulate transfer film growth remains unclear. In this work, the tribological performance of phenolic resin (PF)-based coatings filled with lanthanum oxide (La2O3) and lanthanum fluoride (LaF3) was systematically investigated. The results demonstrate that the friction coefficients of 5La2O3/PF and 3LaF3/PF decrease to 0.024 and 0.031, representing a 79.66% and 73.95% reduction compared to pure PF, which compensates for the inadequacy of oil lubrication. Tribochemical analyses and characterizations of tribofilm structures confirm that complex tribochemical reactions involving rare-earth compounds occur, promoting the growth of a solid-lubricating tribofilm at the boundary lubrication interface. This work provides a theoretical foundation for the design of high-performance polymer lubricating coatings.

1. Introduction

Friction and wear are widely prevalent among the components of mechanical motion systems, seriously affecting the service life and operational efficiency of mechanical equipment, and consequently leading to substantial material losses and energy wastage [1,2,3,4]. With the rapid development of modern equipment, the demands for high rotational speeds, low fuel consumption, high power output, and low emissions have resulted in many moving mechanisms frequently operating within the mixed lubrication or even boundary lubrication regimes. This, in turn, triggers rapid wear or even seizure of tribological materials, severely compromising the reliability of moving mechanisms [5,6,7]. Therefore, complex working environments pose severe challenges to the tribological design of motion systems.

Polymer composite materials, characterized by their excellent self-lubricating properties, chemical stability, and structural designability, have found widespread applications in the field of modern equipment [8,9]. For instance, spraying polymer self-lubricating coatings on the surface of the piston skirt in automotive engines can significantly reduce friction, preventing piston scuffing. Tribological properties are not inherent attributes of polymer composite materials. A stable and easily sheared transfer film generated in situ can significantly reduce the friction and wear of polymer composite materials [10]. Ye et al. [11] found that PTFE/α-Al2O3 nanocomposites exhibit extremely low wear rates. Their analysis suggested that free radicals generated from the chain-breaking of PTFE molecules can undergo chelation reactions with the metal counterpart and the released nanoparticles, forming a stable and continuous transfer film and thus reducing material wear. Kasey et al.’s research proposed that the polar carbonyl groups in polyetheretherketone can enhance the bonding strength of the transfer film [12]. Therefore, by regulating the tribochemical reactions among polymers, functional fillers, and the metal counterpart surface, and promoting the growth of high-performance transfer films, the tribological properties of polymer–metal pairs can be significantly improved.

Research has confirmed that rare-earth compounds, as solid lubricants, can significantly improve the tribological properties of polymers [13]. Gao et al. [14] investigated the influence of La2O3-modified bamboo fiber composites on the tribological performance when in friction with HT250 steel. The research revealed that the worn surface of the composite filled with La2O3 was smoother, with a significantly reduced number of pits, effectively suppressing the adhesion and spalling phenomena of the material. Xiong et al. [15] studied the tribological properties of nylon 1010 (PA1010) composites filled with different rare-earth compounds, namely La2O3, CeO2, and LaF3. The results showed that the addition of these three rare-earth compounds enhanced the tribological properties of PA1010, with the La2O3/PA1010 composite exhibiting the best tribological performance. Although previous studies have reported that rare-earth compounds can improve the tribological properties of polymer materials, the physicochemical behavior of rare-earth compounds during the friction process and their interfacial action mechanisms affecting the formation of transfer films have not been thoroughly elucidated.

In this work, La2O3 and LaF rare-earth particles were separately filled into PF. The influence of La2O3 and LaF3 on the tribological behavior of PF-based coatings under boundary lubrication conditions was comparatively investigated. Meanwhile, the nanostructure of the transfer film generated at the friction interface was deeply characterized and the interfacial tribo-chemical reactions occurring during the friction process were analyzed. This study aims to elucidate the tribological mechanisms of La2O3 and LaF3 in phenolic resin coatings and reveal their functional roles under boundary lubrication. Ultimately, this work seeks to establish a theoretical foundation for designing, preparing, and applying high-performance polymer coatings with superior friction reduction and wear resistance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Specimens’ Preparation

The liquid thermosetting phenolic resin with a purity of ~95% and chemical formula (C6H6O·CH2O)ₙ was purchased from Borun New Materials Co., Ltd. Anyang, China and its chemical structure is illustrated in Figure 1. Both La2O3 and LaF3 powders were supplied by China National Pharmaceutical Group Co., Ltd., Beijing, China. The morphology and crystal structure of the powders were characterized using field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, Merlin Compact, Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) and X-ray diffraction (XRD, Rigaku Smartlab-9kw, Tokyo, Japan), respectively. Poly-α-olefins with the 0.01558 Pa·s (PAO4, purity: 99%, melting point: 66.3 °C, boiling point: 316 °C) was purchased from ExxonMobil China Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China.

Figure 1.

The chemical structure of the liquid thermosetting phenolic resin.

To comparatively investigate the effects of La2O3 and LaF3 on the tribological properties of PF-based composite coatings, a series of coatings with La2O3 content ranging from 0.5 to 7 vol.% and LaF3 content from 0.5 to 5 vol.% were prepared, designated as La2O3/PF and LaF3/PF, respectively (details in Table 1). The preparation process began by mixing La2O3 or LaF3 powders with phenolic resin in a vacuum high-speed mixer (Dispermat CN-10, VMA-Getzmann, Reichshof, Germany) at 10 °C and 2500 rpm for 10 min. The mixture was then transferred to a three-roll mill (ZYTR-80E, Zhongyi, China) and further dispersed at room temperature and 250 rpm for 5 min to break down agglomerates. Subsequently, a diluent, a blended solution of ethanol, xylene, and n-butanol in a mass ratio of 1:2:2, was added in equal mass to the resulting blend. The diluted resin solution was loaded into a spray gun (WIDER1, Anest Iwata, Yokohama, Japan) and uniformly applied onto aluminum alloy (GB 5052) [16] substrates. Spraying was performed at an air pressure of 0.27 MPa with a vertical spraying distance of 30 cm. After spraying, the coatings were cured at 140 °C for 1 h, and coatings with thickness of 35 ± 5 μm and surface roughness (Ra) of 0.15 ± 0.05 μm were obtained. The prepared samples were cut into 25 mm × 10 mm × 4 mm specimens for tribological testing. Adhesion strength to the aluminum alloy substrate was evaluated using the cross-cut test (ISO 2409:2020) [17]. Nanoindentation tests were performed using a nanoindenter (STeP E400, Anton Paar, Shanghai, China) to determine the coating’s nanohardness and elastic modulus.

Table 1.

The designation and compositions of PF coatings (vol.%).

2.2. Tribology Tests

Tribology tests were conducted using a high-speed ring-on-block test rig (MRH-1A, Jinan Yihua, Jinan, China). A schematic diagram of the contact configuration can be found in our previous work [18]. A SUS304 stainless steel ring with an outer diameter of 50 mm was employed as the counterpart. The ring surface was ground and polished with 1000-grit SiC sandpaper, resulting in a surface roughness (Ra) of 0.15 ± 0.05 μm, as measured by a 3D optical surface profiler (MicroXAM-800, KLA Tencor, Milpitas, CA, USA). Prior to testing, both the coating samples and the steel rings were cleaned ultrasonically 0.5 with a fixing working frequency of 40 kHz to remove surface contaminants. The experiments were conducted under two speed conditions. In constant-speed mode, a sliding speed of 0.2 m/s was applied for durations of 1 h. In variable-speed mode, the sliding speed was progressively varied, with stages of 0.03 m/s, 0.05 m/s, 0.10 m/s, 0.20 m/s, 0.40 m/s, and 0.80 m/s, each maintained for 10 min. All tests were carried under an applied load of 100 N and lubricated with PAO4 base oil. To ensure statistical reliability, each test condition was replicated at least three times for the accurate determination of the average coefficient of friction and wear rate.

According to the Hamrock-Dowson equation [19], the calculated oil film thicknesses under a load of 100 N and at speeds of 0.03 m/s, 0.05 m/s, 0.1 m/s, 0.2 m/s, 0.4 m/s, and 0.8 m/s are 0.026 μm, 0.037 μm, 0.061 μm, 0.098 μm, 0.160 μm, and 0.260 μm, respectively. Consequently, the corresponding ratio (λ) of the oil film thickness to the composite surface roughness is 0.09, 0.13, 0.21, 0.35, 0.57, and 0.92. Given that all λ values are less than 1 (λ < 1), the sliding friction under both constant and variable speed conditions occurred within the boundary lubrication regime. The specific wear rate (WS, mm3/Nm) was calculated using Equation (1) after measuring the wear scar width with an optical microscope (W, Olympus BX41, Japan):

where W and L′ represent the width and length (mm) of the wear scar, respectively, R is the radius of the steel ring (mm), L is the total sliding distance (m), and F is the applied load (N).

2.3. Characterization of Worn Surfaces and Tribofilms

The worn surfaces of the polymer composites, as well as the morphologies and chemical compositions of the corresponding stainless steel ring counterparts, were characterized using field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, Merlin Compact, Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). The wear morphology of the coatings was analyzed with a 3D profilometer (SMT-5000, USA). Chemical state changes on the surfaces of the polymer composites, worn areas, and corresponding SUS304 rings were examined by attenuated total reflectance Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR, Tensor 27, Bruker, Bremen, Germany). Additionally, cross-sectional slices of the worn SUS304 rings were prepared via focused ion beam (FIB, FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA) and characterized using high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM, FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA, 200 kV) with accompanying EDS to analyze the nanostructure and chemical composition of the transfer films.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Morphologies and Mechanical Performance

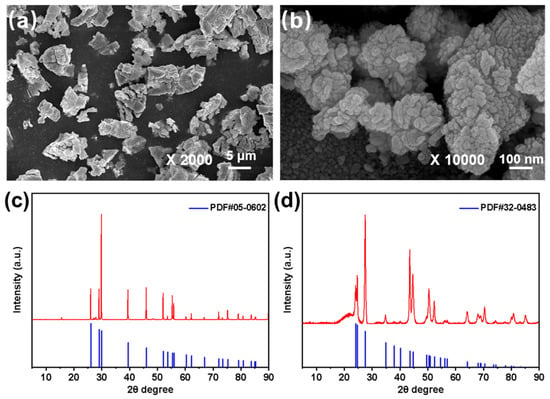

Figure 2 presents the morphologies and crystal structures of La2O3 and LaF3. As shown in Figure 2a,b, La2O3 particles exhibit a micron-scale size distribution of 3~7 μm, whereas LaF3 particles are nano-sized with a range of 200–500 nm. XRD analysis confirms the presence of the (1 0 1), (1 0 2), (1 1 0) and (1 0 3) crystal planes of La2O3 at 2θ values of 29.96°, 39.527°, 46.084° and 52.132°, respectively, which is consistent with the standard PDF card #05-0602 for La2O3. Furthermore, the (1 1 0), (1 1 1), (3 0 0) and (1 1 3) crystal planes of LaF3 are identified at 2θ values of 24.738°, 27.585°, 43.604° and 44.738°, respectively, matching the standard PDF card #32-0843 for LaF3.

Figure 2.

FESEM images of (a) La2O3 and (b) LaF3, and XRD pattens of (c) La2O3 and (d) LaF3.

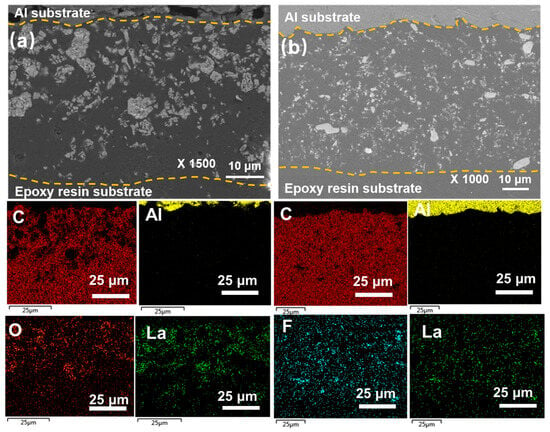

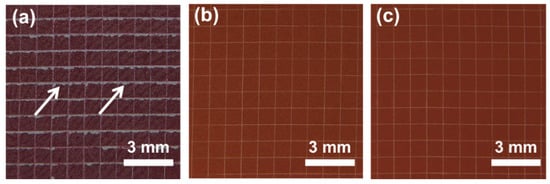

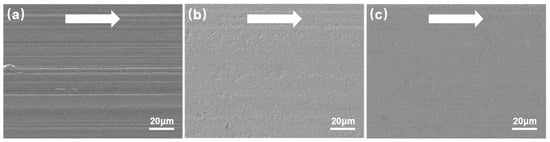

Figure 3 shows the cross-sectional SEM images and elemental distribution mappings of the polymer coatings. The coating samples were embedded in epoxy resin to observe their cross-sectional morphology. As shown in Figure 3a, the thicknesses of the 5La2O3/PF and 3LaF3/PF coatings are approximately 40 μm. EDS mapping of La elements indicates that both La2O3 and LaF3 are uniformly distributed within the coatings without obvious agglomeration. The adhesion strength of the coatings was evaluated using the cross-cut test according to ISO 2409:2020. Figure 4a–c present the optical micrographs of the scored surfaces for the pure PF coating, 5La2O3/PF, and 3LaF3/PF composite coatings, respectively. The results reveal that, as indicated by the arrows in Figure 4a, significant coating detachment occurs at the cross-cut intersections of the pure PF coating, corresponding to an adhesion classification of Grade 5. In contrast, the addition of La2O3 and LaF3 markedly improves the adhesion strength. As shown in Figure 4b,c, coating detachment is significantly reduced, and the adhesion classification improves to Grade 0. This enhancement is attributed to the incorporation of rare earth particles, which increases the specific surface area of the coating, helping to better disperse stress, inhibit crack propagation, and thereby improve the coating’s adhesion strength.

Figure 3.

SEM images and the elemental mapping of (a) 5La2O3/PF and (b) 3LaF3/PF coatings.

Figure 4.

Optical images of (a) the PF, (b) 5La2O3/PF, and (c) 3LaF3/PF coating surfaces after the cross-cut test.

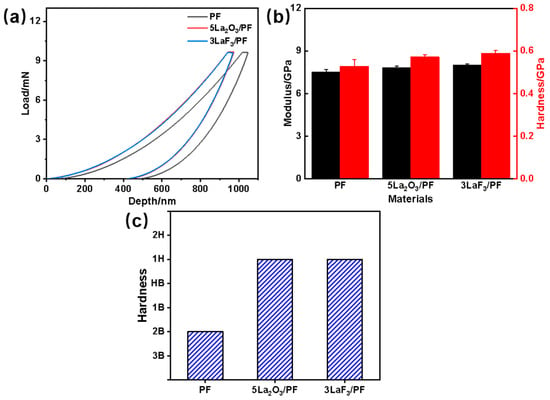

Figure 5 shows the nanoindentation results of PF, 5La2O3/PF, and 3LaF3/PF under an indentation load of 10 mN. As shown in Figure 5a, the indentation depths of 5La2O3/PF and 3LaF3/PF are significantly smaller than that of PF. This indicates that the hardness of both the 5La2O3/PF and 3LaF3/PF composite coatings is higher than that of the pure PF coating. It can also be observed from Figure 5b that the hardness and modulus of the phenolic composites with La2O3 or LaF3 additives are markedly higher than those of pure PF. Specifically, the hardness and modulus of 5La2O3/PF are 0.57 GPa and 7.83 GPa, respectively, while those of 3LaF3/PF are 0.59 GPa and 8.01 GPa. Furthermore, as seen in Figure 5c, the addition of both La2O3 and LaF3 enhances the Martens hardness of the phenolic composites.

Figure 5.

Nanoindentation tests of PF, 5La2O3/PF, and 3LaF3/PF coatings: (a) Load-depth curves, (b) hardness and modulus, and (c) Martens hardness.

3.2. Tribological Behaviors

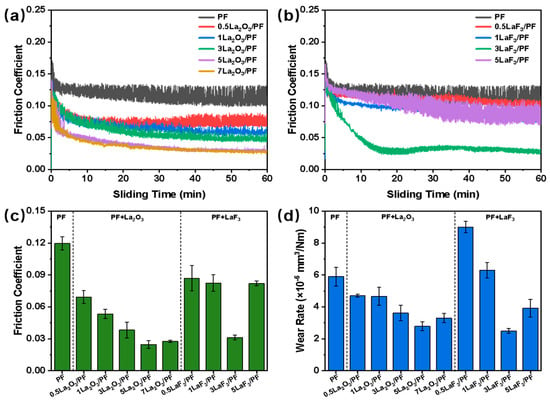

Figure 6a shows the friction coefficients evolution of PF, 0.5La2O3/PF, 1La2O3/PF, 3La2O3/PF, 5La2O3/PF, and 7La2O3/PF coatings under a load of 100 N and a sliding speed of 0.2 m/s. The results indicate that all coatings exhibited a high friction coefficient at the initial run-in stage. As sliding progressed, the gradual formation of a transfer film led to a decreasing trend in the friction coefficient [20]. The pure PF coating showed the highest friction coefficient with significant fluctuations. With the addition of La2O3, the friction coefficient of the composite coatings decreased, and its fluctuation was significantly suppressed. As the La2O3 content increased, the friction coefficient of the composites coating continued to decrease. 5La2O3/PF achieved the lowest friction coefficient of 0.024, representing a 79.66% reduction compared to pure PF. Figure 6b presents the friction coefficients evolution of PF, 0.5LaF3/PF, 1LaF3/PF, 3LaF3/PF, and 5LaF3/PF coatings. The results reveal that a small amount of LaF3 had little effect on the friction coefficient of the PF coating. When 3 vol.% LaF3 was added, the friction coefficient reached its minimum value of approximately 0.031. However, further increasing the LaF3 content resulted in a higher friction coefficient, which may be attributed to the agglomeration of excessive LaF3 in the composite coating, increasing the shear force at the friction interface.

Figure 6.

(a) Evolutions of friction coefficients of PF, 0.5La2O3/PF, 1La2O3/PF, 3La2O3/PF, 5La2O3/PF and 7La2O3/PF coatings, and (b) PF, 0.5LaF3/PF, 1LaF3/PF, 3LaF3/PF and 5LaF3/PF coatings as a function of sliding time after rubbing 1 h; (c) average friction coefficients and (d) wear rates of PF and its composites coatings filled with La2O3 and LaF3. Load: 100 N, speed: 0.2 m/s.

Figure 6c,d present the average friction coefficient and wear rate of the PF-based composite coatings. As seen in Figure 6c, the lowest friction coefficient of 0.024 was achieved with 5 vol.% La2O3. However, a further increase in the La2O3 content led to a higher friction coefficient. This indicates that an appropriate amount of La2O3 can effectively reduce the friction coefficient of PF coatings. Similarly, the incorporation of LaF3 at various concentrations also reduced the friction coefficient compared to pure PF. Among them, the 3LaF3/PF composite exhibited the lowest value of 0.031, which is a 73.95% reduction compared to the pure PF coating. Figure 6d shows the average wear rates of the composite coatings. Different amounts of La2O3 all contributed to a lower wear rate, with the 5La2O3/PF coating exhibiting the minimum value of 2.79 × 10−6 mm3/N·m. In contrast, a small amount of LaF3 initially increased the wear rate of the PF coating. As the LaF3 content increased, the wear rate of the LaF3/PF composites gradually decreased, reaching a minimum of 2.49 × 10−6 mm3/N·m for the 3LaF3/PF coating.

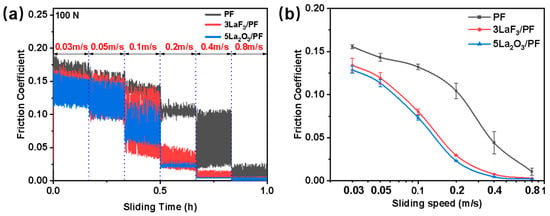

To further investigate the influence of La2O3 and LaF3 on the tribological properties of PF coatings, the tribological behaviors of PF, 5La2O3/PF, and 3LaF3/PF coatings under dynamic operating conditions were examined. The variations in the friction coefficient with time and sliding speed are shown in Figure 7. As can be seen from Figure 7a, the friction coefficients of the PF, 5La2O3/PF, and 3LaF3/PF coatings all decreased with increasing sliding speed. In the speed range from 0.03 to 0.8 m/s, the friction coefficients of both 5La2O3/PF and 3LaF3/PF were lower than that of pure PF, indicating the remarkable friction-reducing effect of La2O3 and LaF3. Notably, at sliding speeds of 0.1 m/s and 0.2 m/s, the friction coefficient of 5La2O3/PF was reduced by 44.55% and 77.85%, respectively, compared to pure PF. Similarly, the friction coefficient of 3LaF3/PF was reduced by 39.18% and 71.64%, respectively. It is believed that the addition of La2O3 and LaF3 may promote the formation of a transfer film at the friction interface which compensated for the insufficiency of the lubricating oil film [21], shifting the interfacial friction into a mixed lubrication regime (Figure 7b).

Figure 7.

(a) Friction coefficient evolutions of PF, 5La2O3/PF and 3LaF3/PF as a function of sliding speed and time; (b) average friction coefficients of PF, 5La2O3/PF and 3LaF3/PF at different sliding speed. Load: 100 N.

3.3. Worn Surfaces and Tribofilms

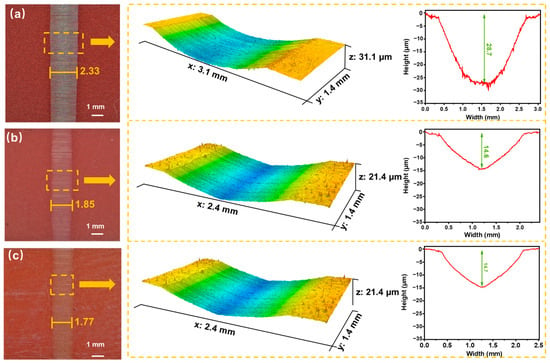

Figure 8 shows the worn surfaces and wear profiles of the PF, 5La2O3/PF, and 3LaF3/PF coatings after testing under a load of 100 N and a sliding speed of 0.2 m/s. As seen in Figure 8, the pure PF coating exhibits the poorest wear resistance, with the largest wear scar width of approximately 2.33 mm and the greatest wear scar depth of about 28.7 µm. With the addition of 5 vol.% La2O3, the wear resistance of the coating is improved. The 5La2O3/PF coating shows a reduced wear scar width and depth of 1.85 mm and 14.6 µm, respectively. Similarly, upon incorporating 3 vol.% LaF3, the wear performance is enhanced. Compared to the pure PF coating, the 3LaF3/PF composite demonstrates a 24.03% reduction in wear scar width and a 48.78% decrease in wear scar depth.

Figure 8.

Worn morphologies, 3D images and cross-sectional images of worn surfaces of (a) PF, (b) 5La2O3/PF, and (c) 3LaF3/PF at 100 N and 0.2 m/s, respectively.

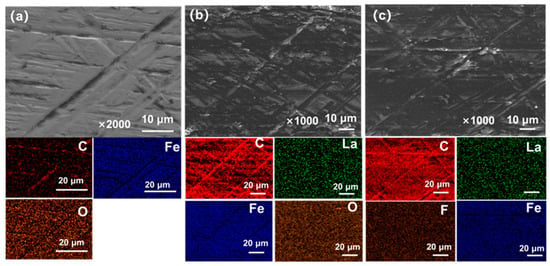

To investigate the effects of La2O3 and LaF3 particles on the wear mechanism of PF coating, the worn surfaces of the polymer coatings were analyzed using SEM. As shown in Figure 9a, the worn surface of the PF coating exhibits significant plow grooves, predominantly aligned parallel to the sliding direction. This is attributed to the relatively low load-bearing capacity of the pure PF coating, which resulted in abrasive wear caused by debris generated during the friction process [21]. After the addition of 5 vol.% La2O3, the worn surface of the 5La2O3/PF coating appears very smooth, with almost no obvious wear observed (Figure 9b). This improvement is due to the enhanced load-bearing capacity at the friction interface provided by the incorporation of La2O3 particles [22]. With the addition of 3 vol.% LaF3, slight scratches can be observed on the worn surface of the 3LaF3/PF coating (Figure 9c). The addition of LaF3 also contributes to some extent to the interface load-bearing capacity; however, its friction-reducing effect is less pronounced than that of La2O3.

Figure 9.

SEM micrographs of worn surfaces of (a) PF, (b) 5La2O3/PF, and (c) 3LaF3/PF at 100 N, 0.2 m/s. Insert: the sliding direction indicated by arrows.

Figure 10 shows SEM images and EDS analysis of the tribofilms formed on stainless steel rings after sliding against PF, 5La2O3/PF, and 3LaF3/PF coatings. As shown in Figure 10a, after sliding against pure PF, a large portion of the metal substrate remains exposed at the friction interface. Transferred debris has accumulated only in some grooves of the counterpart surface, resulting in a non-uniform tribofilm structure [23]. EDS mapping reveals that only small amounts of carbon are present in these grooves, while the worn counterpart surface is predominantly composed of iron. This indicates direct contact at the friction interface during sliding [24], leading to the high friction coefficient and wear rate. After sliding against 5La2O3/PF (Figure 10b), the tribofilm is uniformly distributed. Most grooves on the counterpart surface are filled with transferred debris, and the flat areas are largely covered by the transfer film. EDS mapping confirms that this tribofilm is primarily composed of C and La, indicating the presence of both carbon and La2O3 in the film, which contributes to the reduction in the friction coefficient of PF. After sliding against 3LaF3/PF (Figure 10c), the counterpart surface is almost completely covered by transferred debris, and the tribofilm exhibits an even more uniform structure, effectively preventing direct contact between the friction interfaces during sliding [25]. Consequently, 3LaF3/PF demonstrates a low friction coefficient. EDS mapping further reveals that the tribofilm on the metal surface consists mainly of C and La, with a particularly high C content. This further confirms the excellent lubricity and load-bearing capacity of the transfer film.

Figure 10.

FESEM graphs of worn surfaces of the steel counterfaces rubbed against (a) PF, (b) 5La2O3/PF, and (c) 3LaF3/PF coatings, respectively.

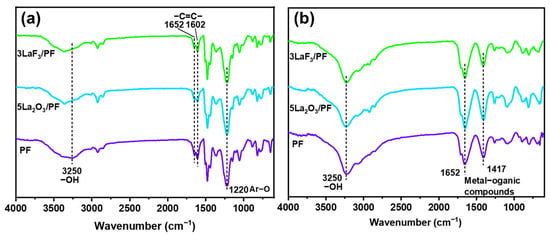

To further investigate potential tribochemical reactions during the sliding process, ATR-FTIR is employed to analyze the chemical states of the worn surfaces of the steel rings after sliding against PF coatings. The results are compared with the chemical structure of unworn PF coatings. As shown in Figure 11a, the characteristic peaks of PF are observed on the unworn surfaces of both pure PF and PF composite coatings. These include the –OH group absorption peak at 3250 cm−1, the aromatic –C=C– stretching vibration peak at 1602 cm−1, and the phenoxy group stretching vibration peak at 1220 cm−1 [26]. The absorption peaks of the steel ring’s worn surface after sliding against the PF composite coatings show distinct changes (Figure 11b). New absorption peaks emerge at 1652 cm−1 and 1417 cm−1, corresponding to the metal–organic compound, and this finding provides evidence for a chelation reaction between decomposed PF products and the steel counterpart [27].

Figure 11.

ATR-FTIR spectra of (a) the unworn PF coatings and (b) the worn surfaces of the steel rings rubbed against PF coatings.

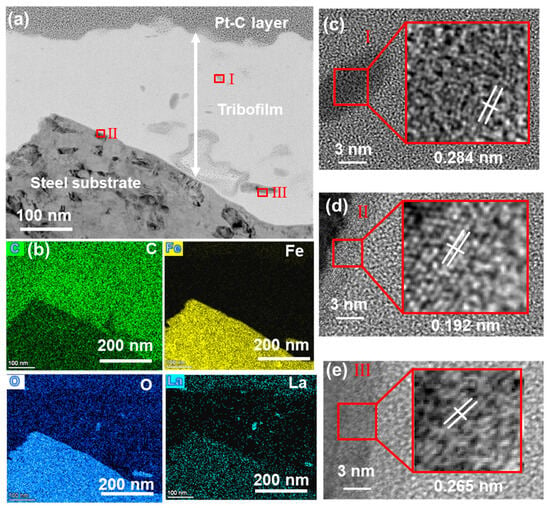

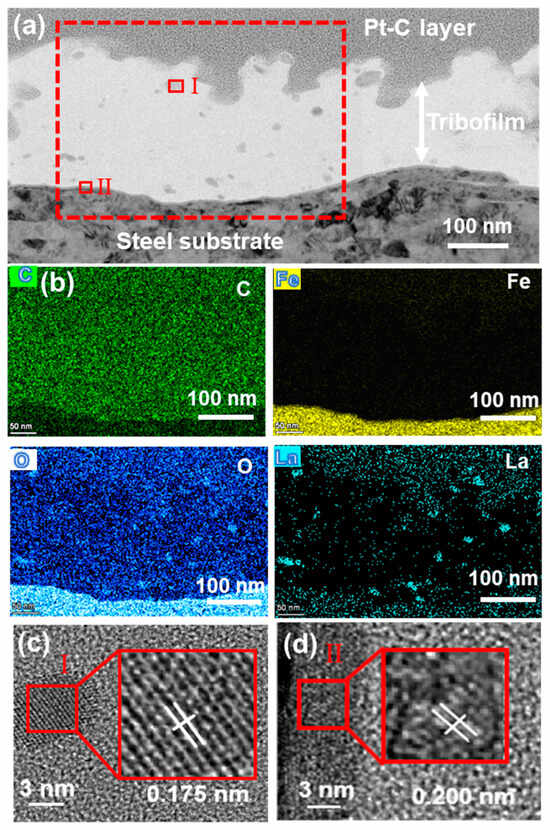

To gain deeper insight into the nanostructure of the transfer film, the surface of the steel ring that had slid against 5La2O3/PF was subjected to FIB milling. The nanostructure and composition of the tribofilm were subsequently analyzed using HR-TEM and EDS mapping. As shown in Figure 12a, a tribofilm with a thickness of approximately 150–300 nm covers the counterpart surface. This film is composed of irregular crystalline structures embedded within a substantial amount of amorphous carbon. EDS mapping results revealed a thin underlying layer within the transfer film exhibiting lattice fringes of 0.192 nm (JCPDS no. 47-1409), which corresponds to an iron oxide layer (Figure 12d). This indicates that tribo-oxidation occurred during the initial sliding stage. The top layer of the tribofilm consists primarily of carbon, with additional Fe, O, and La present (Figure 12b). HR-TEM analysis further identified nanocrystals within the tribofilm exhibiting lattice spacings of 0.284 nm and 0.265 nm, corresponding to La2O3 (JCPDS no. 22-0369) and Fe2O3 (JCPDS no. 40-1139) [28], respectively (Figure 12c,d). These results confirm the occurrence of material transfer and tribo-oxidation during sliding [29]. It is proposed that under mechanical shear forces, the transferred debris and tribo-chemical products were mixed and compacted into a stable transfer film.

Figure 12.

(a) TEM image of the tribofilm of 5La2O3/PF formed on the steel ring surface, (b) elemental mapping of the area shown in (a), and (c–e) HR-TEM images of regions I-III marked in (a).

Figure 13 shows the tribofilm formed on the steel surface after sliding against the 3LaF3/PF coating. As shown in Figure 13a, the counterpart surface is covered by a transfer film with a thickness of approximately 100–200 nm. EDS mapping results revealed a thin underlying layer in the transfer film exhibiting lattice fringes of 0.200 nm (JCPDS no. 21-0920), corresponding to an iron oxide layer (Figure 13d), indicating that tribo-oxidation occurred during the initial sliding stage [30]. The top layer of the transfer film consists primarily of carbon, along with O and La (Figure 13b). The elemental distribution confirms that the irregular crystalline structures are transferred to La2O3. This is attributed to the oxidation of LaF3 into La2O3 induced by frictional heat and mechanical shear [13]. This finding is further supported by the HR-TEM results in Figure 13c, which identify nanocrystals with lattice spacings of 0.284 nm (JCPDS no. 05-0602) corresponding to La2O3 within the transfer film.

Figure 13.

(a) TEM image of the tribofilm of 3LaF3/PF formed on the steel ring surface, (b) elemental mapping of the area shown in (a), (c,d) HR-TEM images of regions I-II marked in (a).

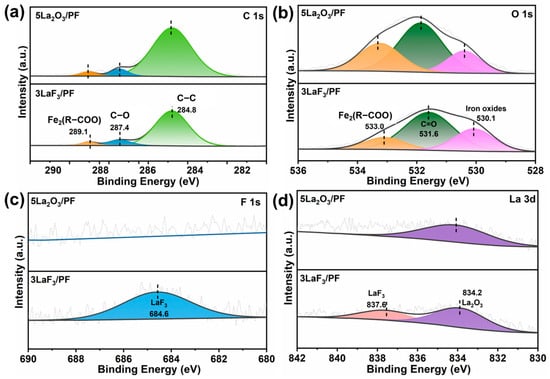

To further confirm the chemical state of the tribofilm, Figure 14 presents the XPS spectra of the tribofilms formed on the metal counterface after sliding against 3LaF3/PF and 5La2O3/PF composites, respectively. As shown in Figure 14a, the C 1s spectrum exhibits peak at 284.8 eV and 287.4 eV, corresponding to C–C and C–O in PF, respectively, confirming the transfer of PF material during sliding [27]. Furthermore, the binding energy of 289.1 eV in the C 1s spectrum, combined with that of 533.0 eV in the O 1s spectrum, verifies the formation of Fe2(R–COO)ₙ (Figure 14b), further supporting the tribochemical reaction between the transferred PF and the counterpart [31]. As shown in Figure 14c, the peak at 684.6 eV in the F 1s spectrum, combined with the peak at 837.6 eV in the La 3d spectrum (Figure 14d), confirms the transfer of LaF3 [13]. Furthermore, the presence of an O–La bond at 834.2 eV further indicates the oxidation of LaF3 to La2O3. This observation is consistent with the TEM characterization results of the tribofilm. From a thermodynamic perspective, La2O3 exhibits a lower standard Gibbs free energy of formation than LaF3 making it far more thermodynamically stable. La2O3 possesses a high lattice energy that is indicative of a highly stable crystal structure and the transformation from LaF3 to La2O3 thus represents a transition from a metastable state to a thermodynamically stable state with the frictional process supplying the activation energy required [32].

Figure 14.

XPS spectrum of (a) C 1s, (b) O 1s, (c) F 1s, and (d) La 3d of the steel surface rubbed with 3LaF3/PF and 5La2O3/PF composites.

4. Conclusions

In this work, a series of La2O3 and LaF3-filled PF composite coatings were fabricated. The effects of La2O3 and LaF3 on the tribological performance of the composite coatings under boundary lubrication conditions were systematically investigated. Based on the nanostructure and composition of the tribofilms, the lubrication mechanisms of La2O3 and LaF3 in the PF coatings were elucidated. The key conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- The incorporation of La2O3 and LaF3 significantly reduces the friction coefficient of the PF coating. Specifically, with the addition of 5 vol.% La2O3 and 3 vol.% LaF3, the friction coefficient of the PF coating is decreased by 80.0% and 73.95% compared to that of pure PF, respectively.

- (2)

- Analysis of the EDS results reveals that uniform tribofilms form on the respective counterpart surfaces following sliding against the 5La2O3/PF and 3LaF3/PF coatings, indicating that the rare-earth compounds facilitate tribofilm growth.

- (3)

- Under the combined action of frictional heat and mechanical shear, LaF3 undergoes oxidation to form La2O3, which distributes uniformly within the tribofilms, thereby enhancing the load-bearing capacity and solid lubrication properties of the tribofilms.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, G.L.; Validation, G.L.; Software, G.L.; Methodology, G.L. and D.W.; Investigation, G.L. and D.W.; Formal analysis, G.L.; Conceptualization, G.L.; Writing-review & editing, D.W., H.Q. and G.Z.; Conceptualization, H.Q. and G.Z.; Supervision, G.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors greatly appreciate the financial supports from the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. XDB0470201), International Partnership Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. 121B62KYSB20210030), Key R&D Program of Shandong Province, China (2023CXPT060), and the Taishan Industrial Experts Program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Li, Q.; Li, W. Recent development in surface/interface friction of two-dimensional black phosphorus: A review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 340, 103464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Shen, H.; Zhou, C.; Du, C.; Song, Y.; Yang, S.; Yin, X. Temperature-triggered self-lubricating behaviour via bioinspired multifunctional rigid polymer for adaptive friction control. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 522, 167439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Lamim, T.; Martinez, D.M.; Pigosso, T.; Klein, A.N.; Bendo, T.; Binder, C. Structural evolution of a carbon nanotube film under sliding wear: From a forest to a self-lubricating nanocomposite tribofilm. Carbon 2025, 238, 120224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Shi, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, R.; Ma, X.; Yang, Y.; Cui, C.; Wang, W.; Li, J. Phytic Acid-Modified Black Phosphorus Nanosheets Achieve Ultrahigh Load Bearing and Rapid Superlubrication on Engineered Steel Surfaces. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2500057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Gao, C.; Duan, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Z. Achieving oil-based superlubricity with near-zero wear via synergistic effect between PEEK-PTFE and PAO40 containing DDP-Cu nanoparticles. Tribol. Int. 2025, 208, 110645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, X.; Tong, L. Boosting thermal conductivity and tribological performance of polyarylene ether nitrile synergistically by fabricating SiCws-BNNS multidimensional networks. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2025, 194, 108888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, S.; Vishwakarma, J.; Nema, S.; Ohlan, A.; Ashiq, M.; Dhand, C.; Dwivedi, N. Slippery and wear-resistant shape memory polymers enabled by the reinforcement of double transition metal-based MAX phase (Mo2TiAlC2). Carbon 2025, 244, 120635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Zhang, L.; Xie, G.; Guo, Y.; Si, L.; Luo, J. Friction and wear behavior of PTFE coatings modified with poly (methyl methacrylate). Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 172, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Song, W. Friction Behavior of Molybdenum Disulfide/Polytetrafluoroethylene-Coated Cemented Carbide Fabricated with a Spray Technique in Dry Friction Conditions. Coatings 2025, 15, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Qi, X.; Dong, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Fan, B.; Yang, Y. Transfer film formation mechanism and tribochemistry evolution of a low-wear polyimide/mesoporous silica nanocomposite in dry sliding against bearing steel. Tribol. Int. 2018, 120, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Burris, D.; Xie, T. A Review of Transfer Films and Their Role in Ultra-Low-Wear Sliding of Polymers. Lubricants 2016, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.L.; Sidebottom, M.A.; Atkinson, C.C.; Babuska, T.F.; Kolanovic, C.A.; Boulden, B.J.; Junk, C.P.; Krick, B.A. Ultralow Wear PTFE-Based Polymer Composites—The Role of Water and Tribochemistry. Macromolecules 2019, 52, 5268–5277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Wan, H.; Chen, L.; Zhou, H.; Chen, J. Effects of nano-LaF3 on the friction and wear behaviors of PTFE-based bonded solid lubricating coatings under different lubrication conditions. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 382, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Gao, C.; He, F.; Lin, Y. The Role of Rare Earth Lanthanum Oxide in Polymeric Matrix Brake Composites to Replace Copper. Polymers 2018, 10, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, D.; Chen, L.; Zhang, D. Tribological Properties of PA1010 Composites Filled with Rare Earth Compounds. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 2001, 30, 5. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 3880-2012; Wrought Aluminium and Aluminium Alloy Plates, Sheets and Strips for General Engineering. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2012.

- ISO 2409:2020; Paints and Varnishes-Cross-Cut Test. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Guo, L.; Zhang, G.; Wang, D.; Zhao, F.; Wang, T.; Wang, Q. Significance of combined functional nanoparticles for enhancing tribological performance of PEEK reinforced with carbon fibers. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2017, 102, 400–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.; Björling, M.; Matta, C.; Meeuwenoord, R.; Jantel, U.; Larsson, R. An investigation of film formation and pressure-viscosity relationship of water-based lubricants in elastohydrodynamic contacts. Tribol. Int. 2025, 208, 110654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Zhang, G.; Zheng, Z.; Yu, J.; Hu, C. Tribological properties of polyimide composites reinforced with fibers rubbing against Al2O3. Friction 2020, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baş, H.; Özen, O.; Beşirbeyoğlu, M.A. Tribological properties of MoS2 and CaF2 particles as grease additives on the performance of block-on-ring surface contact. Tribol. Int. 2022, 168, 107433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Kumara, C.; Luo, H.; Meyer, H.M.; He, X.; Ngo, D.; Kim, S.H.; Qu, J. Ultralow Boundary Lubrication Friction by Three-Way Synergistic Interactions among Ionic Liquid, Friction Modifier, and Dispersant. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 17077–17090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Xie, S.; Ye, W.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, P. Sandwich-like tribofilm induced highly effective lubrication for MoDTP coupled with hydroxy-magnesium silicate (MSH). Tribol. Int. 2024, 198, 109902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yu, H.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Wang, H.; Song, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Guo, Z.; Algadi, H. Dual-phase enhanced polytetrafluoroethylene composites with friction-trigged self-healing interfaces: Role of antigorite and graphene in tribofilm evolution. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 725, 137733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Li, D.; Gu, J.; Gao, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, P.; Xu, J.; Wang, C.; Wang, T.; Wang, Q. Smart polymer self-lubricating material: Optimal structure of porous polyimide with base oils for super-low friction and wear. Friction 2025, 13, 9441007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; He, R.; Li, H.; Pei, X.; Zhang, G. Ultra-low Friction and Wear of Phenolic Composites Reinforced with Halloysite Nanotubes. Tribol. Int. 2025, 204, 110419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Li, G.; Qi, H.; Zhang, G. Extraordinary solid lubrication performance achieved via the growth of multi-layered tribofilms facilitated by halloysite nanotubes. Wear 2025, 582–583, 206332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, N.; Bonoldi, L.; Assanelli, G.; Notari, M.; Lucotti, A.; Tommasini, M.; Cuppen, H.M.; Galimberti, D.R. Digging into the friction reduction mechanism of organic friction modifiers on steel surfaces: Chains packing vs. molecule–metal interactions. Tribol. Int. 2024, 195, 109649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhowalla, M.; Amaratunga, G.A. Thin films of fullerene-like MoS2 nanoparticles with ultra-low friction and wear. Nature 2000, 407, 164–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Chang, Q.; Gao, K.; Wang, B.; Gao, R.; Yan, Q. Octadecyltrimethoxysilane modified freeze-drying magnesium silicate hydroxide towards high-performance wear-resistance: Synthesis, characterization, and tribological evaluation. Wear 2023, 523, 204768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanes, J.; Avil´es, M.-D.; Saurín, N.; Espinosa, T.; Carrion´, F.-J.; Bermúdez, M.-D. Synergy between graphene and ionic liquid lubricant additives. Tribol. Int. 2017, 116, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeu, J.G.F.; Dixon, D.A. Energetic and Electronic Properties of AcX and LaX (X = O and F). J. Phys. Chem. A 2025, 129, 1396–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).