Abstract

As an efficient and clean renewable energy source, wind energy plays a crucial role in optimizing the energy structure and facilitating a low-carbon transition. However, onshore and offshore wind turbines in cold regions are prone to blade icing, which not only results in a decrease in power generation efficiency and an increase in blade load but also poses the risk of equipment damage. This study employed icing wind tunnel tests and numerical simulation methods to investigate the icing patterns and variations in aerodynamic performance under different blade materials, blade airfoils, and blade angles of attack. The results indicate that with the decrease in ambient temperature, the icing amount on aluminum alloy blades is significantly higher than that on glass fiber reinforced plastic (GFRP) blades; furthermore, the lower the ambient temperature, the smaller the difference in icing distribution characteristics between the two types of blades. When the blade angle of attack changes, the icing distribution characteristics on the blade surface exhibit significant variations. Under the condition of large angles of attack, the icing amount on the lower airfoil surface of the blade increases, while that on the upper airfoil surface decreases. Icing leads to a reduction in the airfoil lift coefficient and an increase in the drag coefficient, thereby causing a decline in the lift-to-drag ratio. With the extension of icing time, the aerodynamic performance of the blade continues to deteriorate. When the icing time reaches 5 min, the maximum reduction in the airfoil lift coefficient is 60.1%, the maximum increase in the drag coefficient is 40.9%, and the maximum reduction in the lift-to-drag ratio is 67.7%. In addition, the blade lift and drag coefficients undergo significant changes with the increase in the angle of attack. For airfoils with large angles of attack, a distinct phenomenon of advanced flow separation is observed after icing. This study can provide a data foundation for research on icing characteristics of wind turbine blades in cold regions and the subsequent development of anti-icing and de-icing methods.

1. Introduction

With the increasingly prominent issues of global warming, worsening environmental conditions, and the growing depletion of fossil energy reserves, the demand for clean energy has surged worldwide [1]. Clean energy plays an increasingly crucial role in addressing climate change, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and safeguarding energy security [2,3]. As a typical clean and renewable energy source, wind energy, characterized by its non-polluting nature, renewability, wide distribution, and sustainability, has gradually become one of the cores of the global energy transition. The utilization of wind energy not only helps reduce reliance on traditional fossil energy but also effectively cuts carbon emissions, alleviating the issue of global warming [4,5]. Many countries and regions have regarded wind energy as a key component of future energy structure adjustment and have carried out large-scale development and utilization. Particularly driven by technological progress and policy support, investment in the wind power industry has continued to increase, and the utilization of wind energy has gradually broken through traditional energy limitations, becoming an indispensable part of the global energy layout [6,7].

With the rapid development of the wind power industry, wind energy has become an important component of the global energy structure [8,9]. However, in the process of the widespread application of wind energy, the wind power industry also faces numerous challenges, among which the icing problem of wind turbine blades under extreme climate conditions is particularly prominent [10,11]. Wind turbines are usually installed in areas rich in wind energy resources, such as plateaus, mountain ridges, mountain tops, and coastal zones. These areas have superior wind energy development potential due to their unique geographical conditions, but they also suffer from poor climatic conditions. Studies have shown that wind energy resources in cold regions are approximately 10% higher than those in warm regions. Although cold regions have high development value for wind power, low-temperature conditions also pose a severe test to the stable operation of wind turbines [12,13]. The wind turbine blades operating under cold climatic conditions are prone to icing, which not only affects the power generation efficiency of wind turbines but also may cause damage to the blade structure, posing significant challenges to the long-term stable operation of wind turbines [14,15].

Icing on wind turbine blades typically occurs in low-temperature and high-humidity environments. When the ambient temperature drops below the dew point, water vapor in the air begins to condense, forming supercooled water droplets. When these supercooled water droplets collide with the operating wind turbine blades, they cause a disturbance effect on the formation of ice nuclei, promoting the adhesion of supercooled water droplets to the blade surface, which then freeze rapidly to form ice accumulation [16]. Icing exerts certain negative impacts on the actual operation process of wind turbines, mainly in the following four aspects: (1) Reduced power generation efficiency: During the operation of wind turbines, blades are exposed to cold and humid environments for a long time, making them prone to icing. This leads to the adhesion of an uneven ice layer on the blade surface, forming an uneven ice structure. This icing phenomenon changes the original aerodynamic shape of the blades and exerts a negative impact on their aerodynamic performance [17,18]. (2) Altered load distribution: Icing on blades significantly changes the lift distribution of wind turbine blades, making the originally uniform lift distribution uneven. The lift in some blade areas is reduced or even completely lost, thereby altering the load distribution of the entire blade [19,20]. (3) Generation of noise pollution: Due to the change in surface irregularity of wind turbine blades after icing, significantly high-frequency noise may be generated during the operation of wind turbines [21]. (4) Occurrence of ice shedding: When the amount of ice accumulation on the blade surface is sufficient, ice blocks may fall off or be thrown away under the action of centrifugal force during rotation. The occurrence of ice shedding may have a severe impact on the operation of wind turbines and equipment safety [22].

The icing of wind turbine blades is jointly restricted by environmental factors and the blade’s own characteristics. Among them, blade material, airfoil, and angle of attack, as key parameters of the blade, have a significant impact on icing distribution and aerodynamic performance. However, existing studies still lack clarity in exploring the relevant icing laws, and the variation laws of blade aerodynamic performance after icing have not been thoroughly investigated. Therefore, it is necessary to strengthen research on the icing characteristics of wind turbine blades. Through in-depth studying of the laws of icing distribution, this research can provide references for subsequent anti-icing and de-icing technologies, improve the stability and efficiency of wind turbines under extreme climate conditions, and promote the sustainable development of the wind power industry in cold regions.

To explore the icing distribution laws of wind turbine blades under cold climatic conditions and the impact of icing on the aerodynamic performance of wind turbines, this study employs a combined method of icing wind tunnel tests and FLUENT numerical simulation to investigate the icing distribution characteristics on the surface of wind turbine blades and the variation laws of aerodynamic performance after icing. The icing distribution characteristics are quantitatively analyzed from perspectives such as ice shape, icing area, average icing thickness, and TIAR. Based on the icing distribution laws of wind turbine blades, the changes in aerodynamic parameters (including lift coefficient, drag coefficient, lift-to-drag ratio, velocity distribution, and pressure distribution) of the blade airfoil section before and after icing are compared to reveal the impact of the laws of icing on the aerodynamic performance of the two-dimensional blade airfoil section.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Icing Wind Tunnel Experimental Research Method

2.1.1. Blade Airfoil Section Icing Wind Tunnel Experimental System

The blade airfoil section icing wind tunnel system is illustrated in Figure 1. The test section has a cross-sectional dimension of 250 mm × 250 mm and a length of 1000 mm and is equipped with a test model fixing device and an observation window. The liquid water content (LWC) in this study was 1.0 g/m3, the mean diameter of supercooled droplets (MVD) was 66 μm, and the relative humidity of the icing environment was approximately 90%. In order to explore the icing process of blades in the initial stage and its influence on aerodynamic performance, the icing experiment duration used in this study is 0–5 min, which can provide data support for clarifying the icing shape, icing thickness, and lift–drag ratio changes during the icing process.

Figure 1.

Blade section icing wind tunnel test system.

2.1.2. Experimental Model

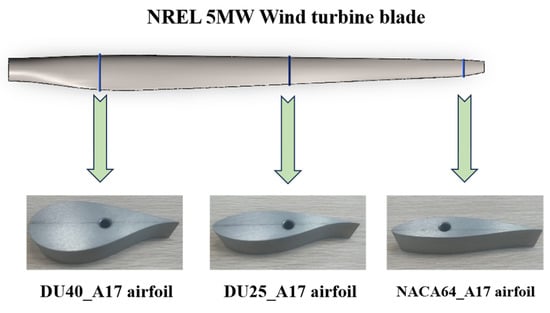

The NREL 5 MW offshore wind turbine is a key demonstration wind turbine designed by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL, USA) to promote the development of offshore wind power technology, and it has been widely used in basic research [23]. Therefore, three airfoils from the leading section, middle section, and trailing section of the NREL 5 MW offshore wind turbine blade were selected as the test models for this study, namely the NACA64_A17 airfoil, DU25_A17 airfoil, and DU40_A17 airfoil. As shown in Figure 2, the blade airfoil section has a chord length (c) of 100 mm and a spanwise thickness (r) of 20 mm, and aluminum alloy material was selected for the blade.

Figure 2.

Experimental model.

2.1.3. Evaluating Indicator

After conducting the icing test on the test airfoil section, a high-speed camera was used to record the entire experimental process. The Catia v6 software is used to process the pictures, depict the icing shapes at different icing times, and measure the icing area and average icing thickness. To further conduct a quantitative analysis of the icing distribution characteristics and their patterns on the blade surface, three evaluation parameters—namely icing area (A), average icing thickness (Hi), and Total Icing Area Ratio (TIAR)—were selected for detailed analysis in this study. Details are as follows: (1) Icing area (A) is defined as the size of the area where ice forms on the blade surface, and it is usually expressed in square millimeters (mm2). It is one of the important parameters for measuring the icing degree of the blade, as shown in Equation (1):

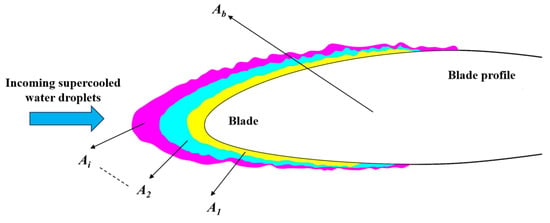

where A is the icing area, and Ai is the increased area of blade icing at the i-th time interval of each icing test, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of icing area.

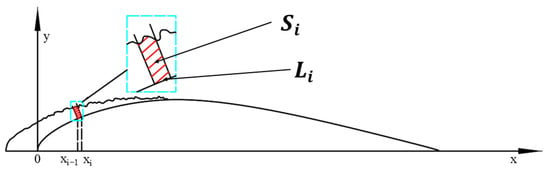

(2) Average icing thickness (Hi) is obtained by measuring and calculating the thickness of the ice layer at different positions within the icing area. Specifically, Hi refers to the average thickness of the ice layer in the normal direction to the blade airfoil surface within the chord length interval xi−1~xi (i = 1, 2, 3…) of the blade airfoil section. It is usually expressed in millimeters (mm). The average icing thickness can intuitively describe the icing distribution of the blade airfoil section and is of great significance for measuring the icing degree of the blade. The specific calculation method is shown in Equation (2):

where Hi is the average thickness of the ice layer in the normal direction of the surface in the corresponding area of the chord xi−1~xi (i = 1, 2, 3…) of the blade section; Si is the ice area in the normal direction of the airfoil surface in the corresponding area of the chord xi−1~xi (i = 1, 2, 3…) of the blade section; and Li is the curve length of the airfoil surface in the corresponding area of the chord xi−1~xi (i = 1, 2, 3…) of the blade airfoil, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Schematic of average ice thickness.

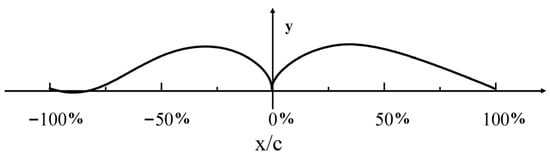

In this study, the chord length of the blade is subjected to nondimensionalization, and its position is labeled. Taking the DU25_A17 airfoil as an example, the positive direction of the horizontal axis in the Figure 5 represents the upper airfoil surface of the blade, while the negative direction represents the lower airfoil surface. The symbol c denotes the chord length of the blade, and x/c represents the relative position along the blade chord length, as shown in the schematic diagram in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of relative position of chord length of DU25_A17 airfoil blade.

(3) The TIAR is a key parameter used to evaluate the icing severity on the surface of wind turbine blades. It represents the ratio of the icing area on the blade surface to the blade cross-sectional area under specific test conditions and is typically expressed as a percentage. Its specific calculation method is given by Equation (3):

where Ai is the increased area of blade icing at the i-th time interval of each icing test; Ab is the cross-sectional area of the blade, as shown in Figure 3.

- (1)

- Blade material

Within the temperature range of icing environments, this study selected −5 °C, −10 °C, and −15 °C as the test temperatures, with the test wind speed set to 10 m/s. Icing wind tunnel tests were conducted on the NACA64_A17, DU25_A17, and DU40_A17 test airfoil blade sections made of GFRP and aluminum alloy. The specific test scheme is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Experimental scheme for the effect of blade material on icing distribution.

- (2)

- Blade Airfoils

This study selected four airfoils—NACA64_A17, DU25_A17, DU40_A17, and NACA0018—as research objects to investigate the influence of different blade airfoils on icing distribution. Among them, NACA64_A17, DU25_A17, and DU40_A17 are asymmetric airfoils used on the blades of the NREL 5 MW offshore wind turbine, while the NACA0018 airfoil is a symmetric airfoil mostly used in basic research. Icing wind tunnel tests were conducted on the above four airfoils under the conditions of a test wind speed of 10 m/s and a test temperature of −10 °C. The specific test scheme is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Experimental program on the effect of blade airfoil shape on icing distribution.

- (3)

- Angle of attack

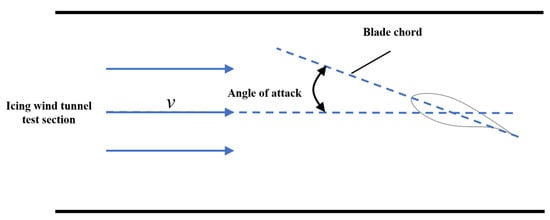

The angle of attack (AoA) refers to the angle between the chord line of the wind turbine blade and the direction of the incoming wind speed, as shown in Figure 6. Variations in the angle of attack directly affect the properties of the airflow around the blade, thereby further influencing the icing process. In this study, an icing wind tunnel was employed to investigate the effect of the blade angle of attack on the icing distribution law, and the test scheme is presented in Table 3.

Figure 6.

Diagram of angle of attack.

Table 3.

Experimental program on the effect of blade angle of attack on icing distribution.

2.2. Numerical Simulation Method of Aerodynamic Performance

2.2.1. Geometric Model and Boundary Conditions

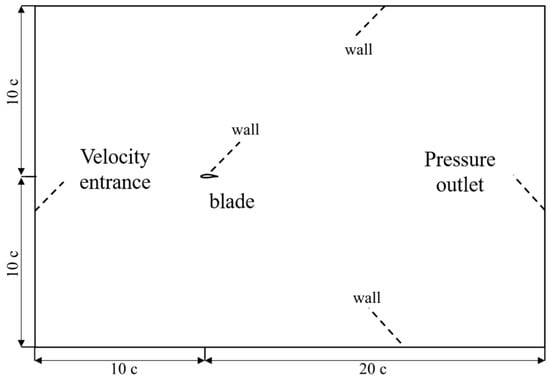

Computational Domain

A two-dimensional rectangular computational domain was adopted in this study. The blade is positioned at the central area of the front 1/3 of the computational domain, with a chord length of c. The computational domain has a length of 30c and a width of 20c. The inlet of the computational domain is set as a velocity inlet, and the outlet is set as a pressure outlet. The airfoil surface, as well as the upper and lower walls of the domain, are configured as no-slip solid wall boundaries (wall). The schematic diagram of the two-dimensional airfoil computational domain is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Schematic of the airfoil calculation domain.

2.2.2. Grid Division and Independence Verification

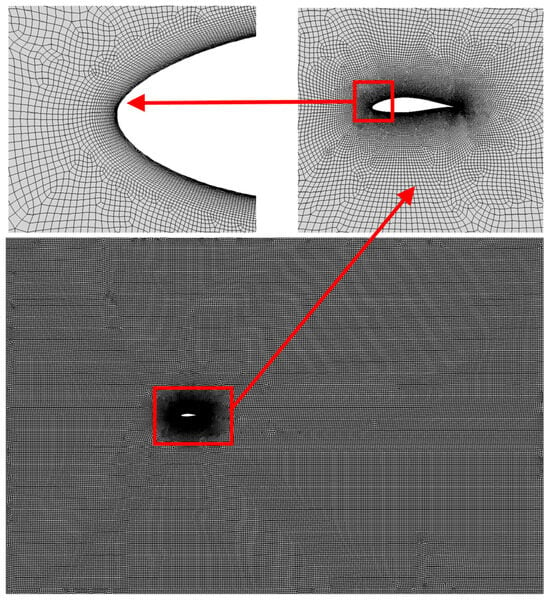

Mesh Generation and Independence Verification

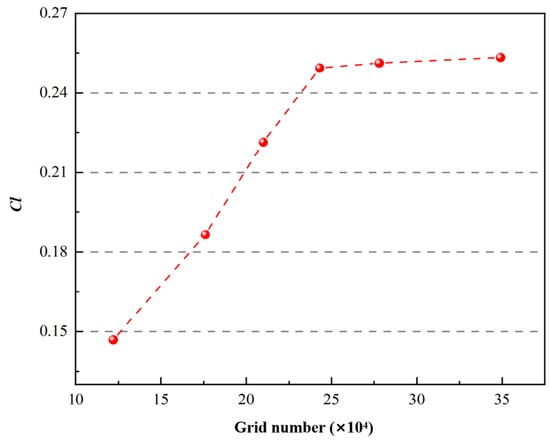

The ICEM was used to mesh the two-dimensional airfoil computational domain; the version of Fluent 6.3 is adopted for numerical solutions and the turbulence model using the SST k-ω model. The airfoil chord length c is 100 mm, and the schematic diagram of the two-dimensional airfoil mesh is shown in Figure 8. The grid independence verification is presented in Figure 9. Taking the mesh generation of the NACA64_A17 airfoil at a wind speed of 10 m/s as an example, under the premise of ensuring that the y+ value is approximately 1, the lift coefficients were compared when the number of meshes was 120,000, 170,000, 210,000, 240,000, 270,000, and 340,000. It was found that the computational results tended to stabilize when the number of meshes exceeded 240,000. Considering both computational accuracy and time cost, the number of meshes was finally determined to be 243,621.

Figure 8.

Schematic of two-dimensional airfoil grid.

Figure 9.

Grid independence verification.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Surface Icing Distribution of Blade Airfoil Sections

3.1.1. Influence of Blade Material

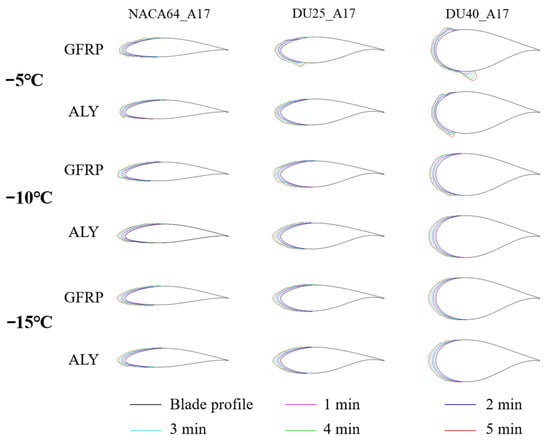

Studying the influence of different blade materials on the surface icing distribution of blades enables a better understanding of the adaptability of wind turbine blades made of different materials to icing environments, which holds guiding significance for the selection of wind turbine materials under different climatic conditions. The icing distribution processes of different blade materials at different ambient temperatures are shown in Figure 10. As can be seen from the figure, the icing areas of the blades at different ambient temperatures are concentrated at the leading edge of the blade, and with the increase in icing time, the icing amount on the blade surface increases significantly. When the ambient temperature is −5 °C, ice runback appears on the lower airfoil surface of the three airfoil blades made of GFRP; however, for aluminum alloy blades, ice runback only appears on the lower airfoil surface of the DU40_A17 airfoil, and the area of ice runback is significantly smaller than that of GFRP blades. Ice runback is formed when supercooled water droplets in the incoming flow impact the surface of the blade airfoil section but cannot freeze completely; the unfrozen supercooled water droplets then move along the lower airfoil surface under the action of gravity and gradually freeze and accumulate during the movement. When the ambient temperature decreases to −10 °C and −15 °C, the thermal conductivity rate on the surface of the blade airfoil section increases significantly, which eliminates the phenomenon of ice runback. At an ambient temperature of −10 °C, the icing profile of aluminum alloy blades is sharper than that of GFRP blades. However, when the temperature drops to −15 °C, there is no significant difference in the icing profile between the two material blades. The main reason for this phenomenon is attributed to the difference in thermal conductivity between the two materials.

Figure 10.

Influence of blade material on the distribution of icing on the surface of blade airfoil segments.

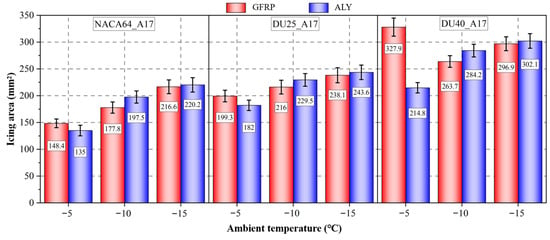

When the icing time is 5 min, the icing areas of the two blade materials at different ambient temperatures are shown in Figure 11. It can be observed from the figure that at an ambient temperature of −5 °C, the icing areas of the GFRP blades with NACA64_A17, DU25_A17, and DU40_A17 airfoils are 148.4 mm2, 199.3 mm2, and 327.9 mm2, respectively, while the icing areas of the aluminum alloy blades with the three airfoils are 135 mm2, 182 mm2, and 214.8 mm2, respectively. At this time, the icing area of GFRP blades is significantly larger than that of aluminum alloy blades. This is mainly because the thermal conductivity of GFRP is lower than that of aluminum alloy, preventing supercooled water droplets from condensing rapidly on the blade surface and thus forming ice runback. The presence of ice runback increases the windward area of the blade, allowing the surface of the blade airfoil section and the ice runback area to capture more supercooled water droplets, thereby increasing the icing area. At ambient temperatures of −10 °C and −15 °C, the icing area on the blade surface shows an increasing trend as the temperature decreases. At this time, the icing area of aluminum alloy blades is generally larger than that of GFRP blades, and the gap in icing area between the two materials gradually narrows as the temperature decreases. This is because the low-temperature environment accelerates the icing process, and more water droplets freeze on the blade surface, increasing the icing area. Meanwhile, as the ambient temperature decreases, the difference in thermal conductivity between the two materials becomes less significant at low temperatures, leading to a gradual reduction in the difference in icing area between the two material blades.

Figure 11.

Effect of blade material on icing area.

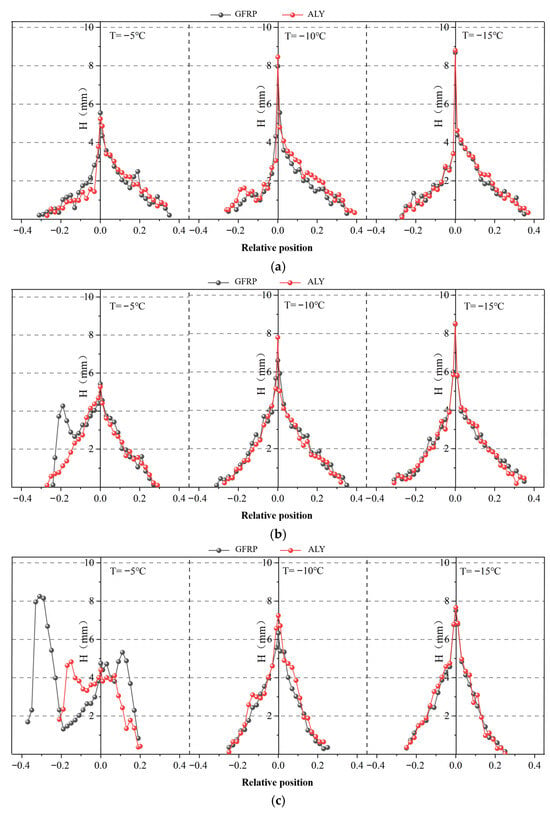

Figure 12 illustrates the influence of different blade materials on the average icing thickness. As shown in Figure 12a, at −5 °C, the maximum icing thickness at the leading edge of the NACA64_A17 airfoil GFRP blade is 5.51 mm, and ice runback is formed within the range of −19% to −15% on the lower airfoil surface. In contrast, the maximum icing thickness at the leading edge of the aluminum alloy blade is 5.22 mm, with no ice runback observed. At −10 °C, the maximum icing thicknesses at the leading edges of the GFRP and aluminum alloy blades are 7.93 mm and 8.46 mm, respectively. As the temperature further decreases to −15 °C, the maximum icing thicknesses at the leading edges of the GFRP and aluminum alloy blades increase to 8.76 mm and 8.81 mm, respectively.

Figure 12.

Effect of blade material on mean icing thickness. (a) NACA64_A17. (b) DU25_A17. (c) DU40_A17.

As shown in Figure 12b, for the DU25_A17 airfoil, at an ambient temperature of −5 °C, the maximum icing thickness at the leading edge of the GFRP blade is 5.42 mm, with ice runback formed within the range of −22% to −9% on the lower airfoil surface. In contrast, the maximum icing thickness at the leading edge of the aluminum alloy blade is 4.62 mm, and no ice runback is observed. Under the condition of −10 °C, the maximum icing thicknesses at the leading edges of the GFRP and aluminum alloy blades are 6.65 mm and 7.89 mm, respectively, and the ice runback phenomenon does not occur. When the ambient temperature is −15 °C, the maximum icing thicknesses at the leading edges of the GFRP and aluminum alloy blades are 8.42 mm and 8.53 mm, respectively, with no ice runback observed either. As shown in Figure 12c, for the DU40_A17 airfoil, when the ambient temperature is −5 °C, both GFRP and aluminum alloy blades exhibit the ice runback phenomenon. The ice runback on the GFRP blade is distributed within the range of −35% to −21% on the lower airfoil surface, while that on the aluminum alloy blade is within the range of −17% to −11% on the lower airfoil surface; notably, the range of ice runback on the GFRP blade is larger than that on the aluminum alloy blade. At lower temperatures, the icing behavior of the DU40_A17 airfoil is consistent with that of the NACA64_A17 and DU25_A17 airfoils, with no ice runback observed anymore. At an ambient temperature of −5 °C, the maximum icing thickness at the leading edge of GFRP blades is consistently greater than that of aluminum alloy blades across all three airfoils. The reason for this is that at relatively high ambient temperatures, aluminum alloy blades can more rapidly conduct the heat of supercooled water droplets impinging on the blade surface to the interior, maintaining a relatively low temperature on the blade surface—which facilitates the rapid formation of the ice layer.

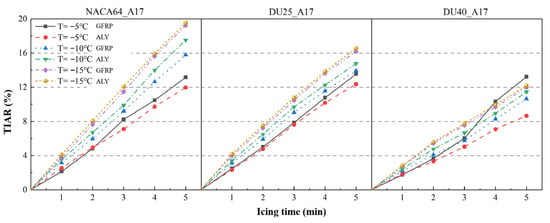

The influence of different blade materials on the TIAR of blade airfoil sections is shown in Figure 13. It can be seen from the figure that in the absence of ice runback, the TIAR of blade airfoil sections increases approximately linearly with the extension of icing time. When the icing time is 5 min and the ambient temperature is −5 °C, the TIAR of GFRP blades is higher than that of aluminum alloy blades. This is mainly due to the formation of ice runback, which increases the contact area between the blade and supercooled water droplets, thereby enhancing the blade’s icing capacity. At ambient temperatures of −10 °C and −15 °C, the TIAR of GFRP blades is lower than that of aluminum alloy blades; moreover, the lower the temperature, the closer the TIARs of the two materials become.

Figure 13.

Effect of blade material on the total icing area rate.

3.1.2. Influence of Blade Airfoil

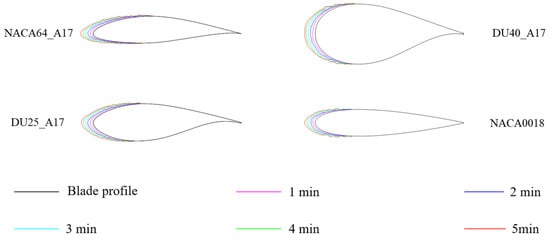

The influence of different blade airfoils on the surface icing distribution of blade airfoil sections is shown in Figure 14. As can be seen from the figure, the icing profiles at the leading edges of the NACA64_A17 and NACA0018 airfoil blades are relatively sharp, while those of the DU25_A17 and DU40_A17 airfoil blades are more rounded. Additionally, the icing profiles on the upper and lower airfoil surfaces of the NACA64_A17 and DU25_A17 airfoils exhibit obvious asymmetry; in contrast, the icing profiles of the DU40_A17 and NACA0018 airfoils show better symmetry. This indicates that the symmetry of the icing profile does not depend entirely on whether the airfoil itself is a symmetric airfoil but is related to the geometric parameters of the airfoil.

Figure 14.

Effect of blade airfoil shape on the distribution of icing on the surface of blade airfoil segments.

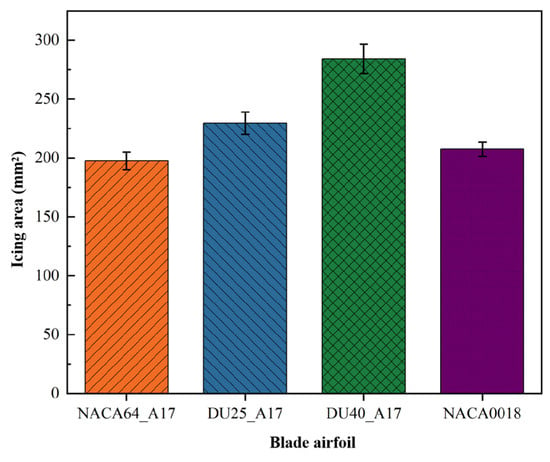

Figure 15 illustrates the influence of blade airfoils on icing area. As can be seen from the figure, the icing areas of different airfoils differ significantly under the same icing environment. At 5 min of icing, the icing areas of the NACA64_A17, DU25_A17, DU40_A17, and NACA0018 airfoils are 197.5 mm2, 229.6 mm2, 284.2 mm2, and 207.5 mm2, respectively. By comparing the geometric parameters of the four airfoils, it can be observed that the icing area exhibits a positive correlation with the maximum relative thickness of the airfoil: the larger the maximum relative thickness of the airfoil, the larger the icing area. The main reason for this phenomenon is that a larger maximum relative thickness of the airfoil results in a larger contact area with supercooled water droplets in the incoming flow, thereby increasing the probability of water droplets impinging on the airfoil surface. This increases the chances of supercooled water droplets adhering to and freezing on the airfoil surface, ultimately expanding the icing area on the blade surface.

Figure 15.

Effect of blade airfoil shape on icing area.

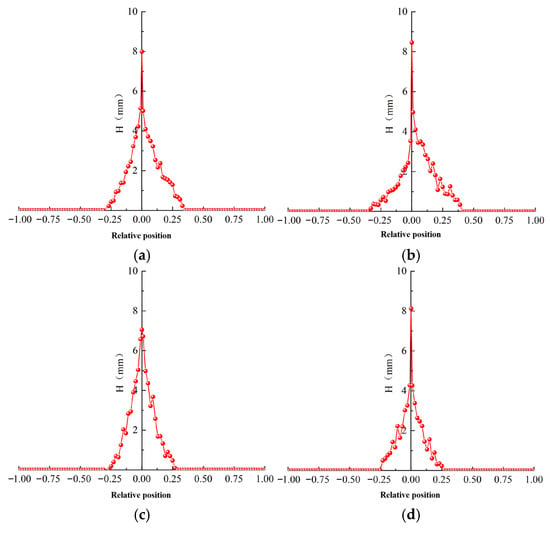

Figure 16 shows the effect of blade airfoil on average icing thickness. The maximum icing thickness at the leading edge of the four airfoils, in descending order, is as follows: NACA64_A17, NACA0018, DU25_A17, and DU40_A17. Meanwhile, their icing ranges, in descending order, are as follows: NACA64_A17, DU25_A17, NACA0018, and DU40_A17. By combining the geometric parameters of the airfoils, it can be observed that the larger the maximum relative thickness of the airfoil, the smaller the maximum icing thickness at its leading edge; simultaneously, the more rearward the position of the airfoil’s maximum relative thickness, the wider the icing range on the blade surface.

Figure 16.

Effect of blade airfoil shape on mean icing thickness. (a) NACA64_A17. (b) DU25_A17. (c) DU40_A17. (d) NACA0018.

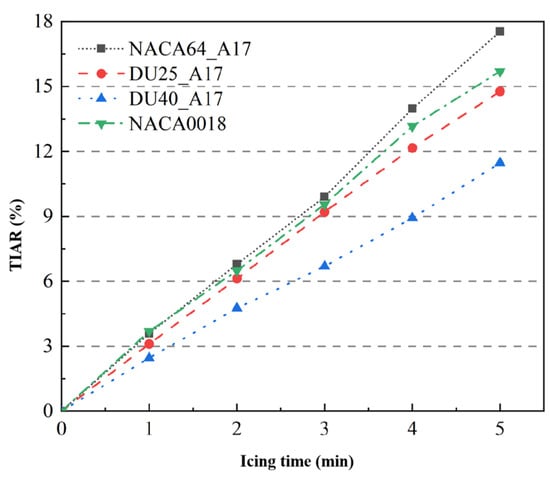

The influence of blade airfoils on TIAR is shown in Figure 17. As can be seen from the figure, when the icing time is 5 min, the TIARs of the NACA64_A17, DU25_A17, DU40_A17, and NACA0018 airfoils are 17.5%, 14.7%, 11.4%, and 15.6%, respectively. From the data, the DU40_A17 airfoil has the lowest TIAR and exhibits the strongest ice resistance capability, followed by the DU25_A17 airfoil, whose TIAR is slightly higher but still maintains good ice resistance performance; the NACA0018 airfoil ranks third in TIAR with moderate ice resistance, while the NACA64_A17 airfoil has the highest TIAR and the weakest ice resistance. It can thus be concluded that the ice resistance capability of the four airfoils, in descending order, is as follows: DU40_A17, DU25_A17, NACA0018, and NACA64_A17. By combining the geometric parameters of the airfoils and the above experimental results, it is found that the ice resistance capability of an airfoil is related to its maximum relative thickness and the relative position of this thickness. Specifically, the larger the maximum relative thickness and the closer its relative position is to the blade leading edge, the stronger the airfoil’s ice resistance capability; conversely, the weaker the ice resistance.

Figure 17.

Effect of blade airfoil shape on the total icing area rate.

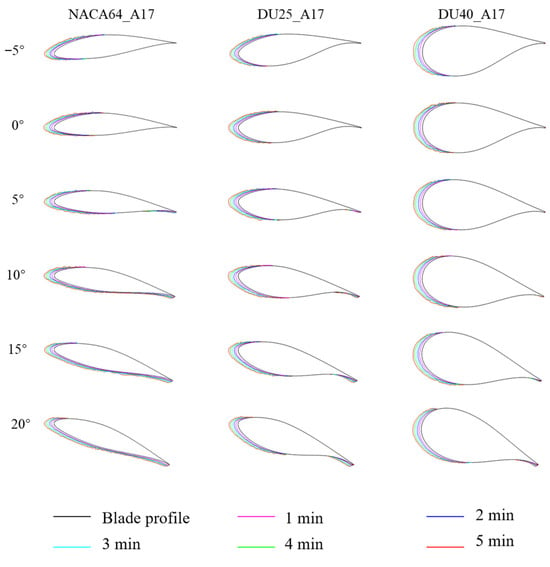

3.1.3. Influence of Angle of Attack

A change in the blade angle of attack causes the impact position of supercooled water droplets on the blade to change, thereby affecting the surface icing distribution of the blade. The icing distributions of the blade airfoil sections for the NACA64_A17, DU25_A17, and DU40_A17 airfoils under different angles of attack are shown in Figure 18. As can be seen from the figure, the change in angle of attack significantly affects the blade surface icing distribution. With the increase in the blade angle of attack, the icing areas of the three airfoils gradually move from the upper airfoil surface to the lower airfoil surface, and icing occurs at the blade trailing edge. For the NACA64_A17 airfoil, icing begins to appear at the trailing edge when the angle of attack is 5°. When the angle of attack increases to greater than 10°, the icing range expands significantly, and the lower airfoil surface is completely covered by the ice layer at this point. For the DU25_A17 airfoil, icing starts to form at the trailing edge at an angle of attack of 5°; as the angle of attack increases, the icing area at the trailing edge gradually expands, and its coverage range continues to increase. As for the DU40_A17 airfoil, icing begins to occur at the trailing edge when the angle of attack is 10°, and the icing area also increases with the increase in the angle of attack. From the icing profiles of the blades, it can be observed that under high angle of attack operating conditions, the NACA64_A17 airfoil has the most severe icing coverage, followed by the DU25_A17 airfoil, while the DU40_A17 airfoil has the smallest icing coverage.

Figure 18.

Effect of blade angle of attack on the distribution of icing on the surface of blade airfoil segments.

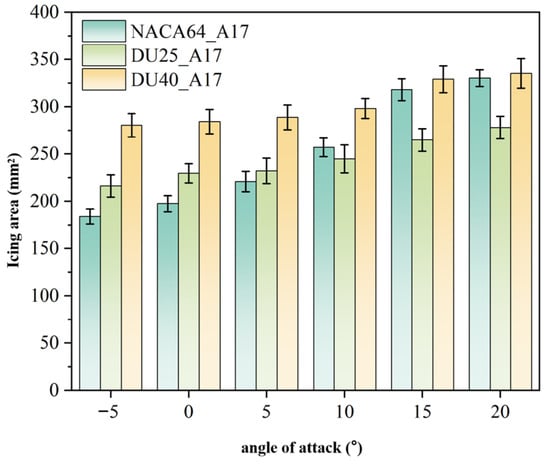

Figure 19 presents the variation in icing area with angle of attack for the three airfoils after 5 min of icing. As can be seen from the figure, the icing area of the blade airfoil sections increases significantly with the increase in the blade angle of attack. When the angle of attack increases from −5° to 20°, the icing areas of the NACA64_A17, DU25_A17, and DU40_A17 airfoils all show a gradual increase. The reason for this phenomenon is that the increase in the angle of attack results in an expanded contact area between the surface of the blade airfoil section and supercooled water droplets. Meanwhile, the air flow over the surface of the blade airfoil section undergoes changes; under the action of pressure difference, the contact between the blade airfoil section surface and supercooled water droplets is enhanced, ultimately leading to more severe icing.

Figure 19.

Effect of blade angle of attack on icing area.

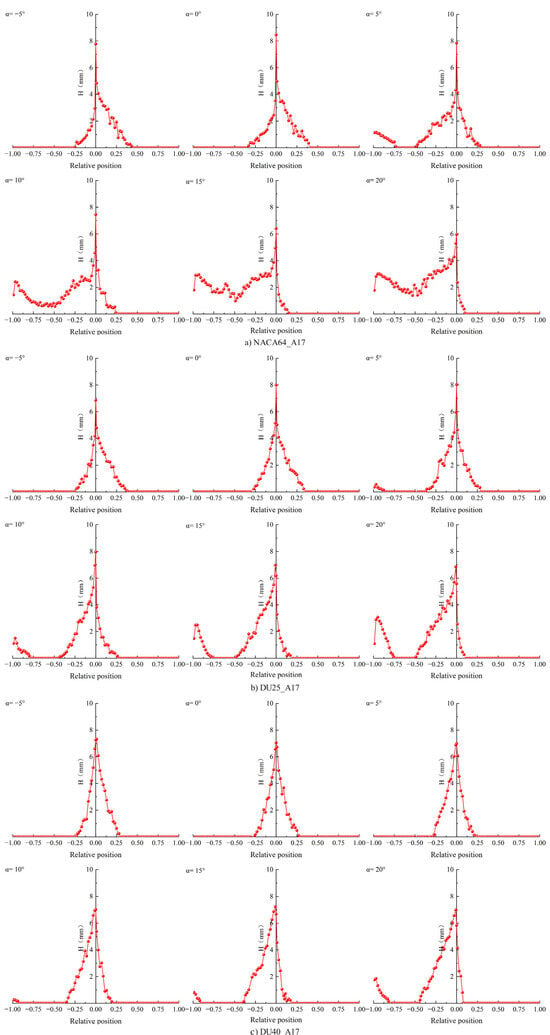

Figure 20 illustrates the variation in average icing thickness with angle of attack for the three airfoils after 5 min of icing. As shown in Figure 20a, when the angle of attack increases from −5° to 20°, the icing area of the NACA64_A17 airfoil undergoes a significant change: its icing range shifts from the original −27% to 43% to −100% to 10%. Meanwhile, the maximum icing thickness at the blade leading edge also changes accordingly, decreasing from 7.78 mm to 5.96 mm. As presented in Figure 20b, when the angle of attack increases from −5° to 20°, the icing range of the DU25_A17 airfoil changes from −23% to 38% to two separate ranges: −100% to −76% and −49% to 9%. At this point, the lower airfoil surface of the DU25_A17 airfoil is not completely covered by the ice layer, resulting in discontinuous icing. Additionally, the maximum icing thickness at the blade leading edge changes from 6.85 mm to 5.57 mm. Z. Xu et al. found that as the angle of attack increases, the maximum thickness of the ice layer decreases for the DU25 airfoil, which is consistent with the pattern observed in this study [24].

Figure 20.

Effect of blade angle of attack on mean icing thickness. (a) NACA64_A17. (b) DU25_A17. (c) DU40_A17.

As shown in Figure 20c, the DU40_A17 airfoil exhibits a similar variation pattern to the DU25_A17 airfoil. As the angle of attack changes, its icing range shifts from −22% to 28% to two distinct ranges, −100% to −82% and −44% to 8%, and the maximum icing thickness at the blade leading edge decreases from 7.25 mm to 5.83 mm. Additionally, there are some differences between the DU25_A17 and DU40_A17 airfoils: for the DU25_A17 airfoil, icing begins to appear at the blade trailing edge at an angle of attack of 5°, whereas for the DU40_A17 airfoil, icing at the trailing edge only starts to occur when the angle of attack reaches 10°. From the above analysis, it can be concluded that as the angle of attack increases, the icing area on the surface of the blade airfoil section gradually moves from the upper airfoil surface to the lower airfoil surface, and the maximum icing thickness at the blade leading edge decreases. When the angle of attack is positive, the position of the maximum icing thickness on the airfoil surface deviates from the stagnation point and moves downward along the airfoil surface; when the angle of attack is negative, this position deviates from the stagnation point and moves upward along the airfoil surface.

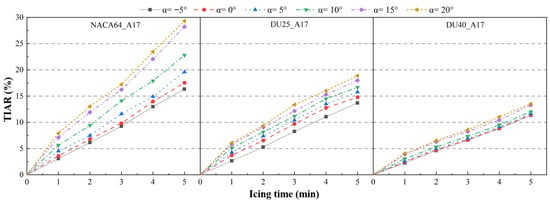

Figure 21 presents the influence law of different angles of attack on the TIAR. As can be seen from the figure, in the early stage of icing, the TIAR under high angle of attack conditions increases rapidly and then shows an approximately linear growth trend as the icing time extends. The three airfoils exhibit the same law regarding TIAR under different angles of attack. Taking the NACA64_A17 airfoil at 5 min of icing as an example, the TIARs of the blade at angles of attack ranging from −5° to 20° are 16.3%, 17.5%, 19.5%, 22.7%, 28.2%, and 29.3% in sequence. The angle of attack and TIAR show a positive correlation—i.e., as the angle of attack increases, the TIAR of the blade increases accordingly. This is mainly because blades under high angle of attack conditions have a stronger ability to capture supercooled water droplets, which increases the probability of supercooled water droplet condensation and accelerates the icing process on the blade surface.

Figure 21.

Effect of blade angle of attack on the total icing area rate.

3.2. The Impact of Icing on the Aerodynamic Performance of Wind Turbine Blades

3.2.1. Effect of Icing Time

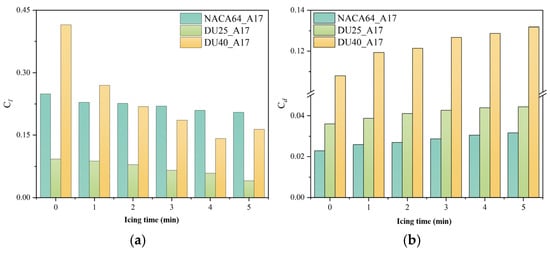

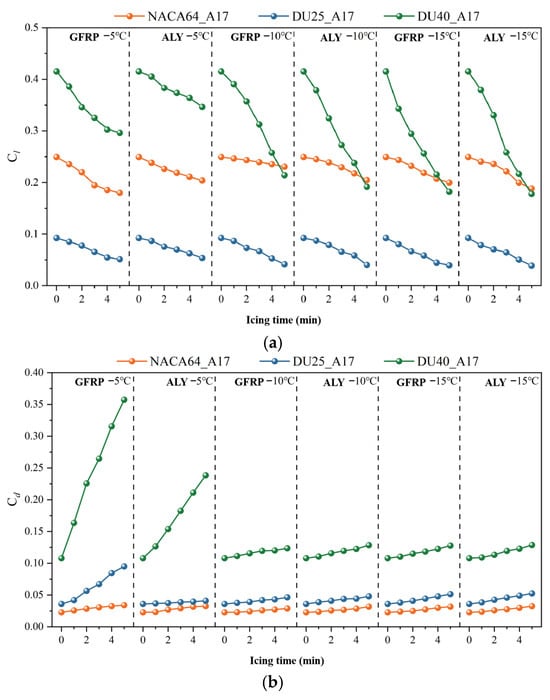

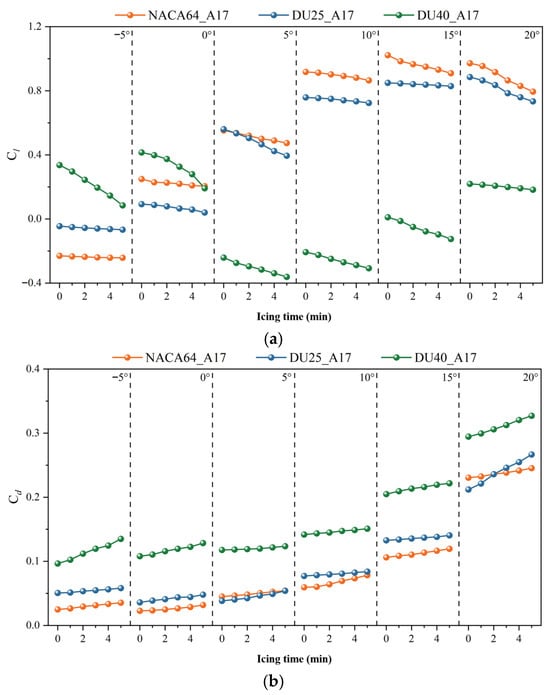

Figure 22 shows the variation in lift and drag coefficients of blade airfoil sections under different icing durations. As can be seen from the figure, when the blades are ice-free, the lift coefficients of the NACA64_A17, DU25_A17, and DU40_A17 airfoils are 0.249, 0.092, and 0.415, respectively; the drag coefficients are 0.022, 0.036, and 0.108, respectively. At this stage, the three airfoils exhibit the highest lift coefficients, the lowest drag coefficients, and the optimal aerodynamic performance. With the increase in icing duration, the lift coefficients of the three airfoils all show a gradual downward trend, while the drag coefficients exhibit a gradual upward trend. When the icing duration reaches 5 min, the lift coefficients of the NACA64_A17, DU25_A17, and DU40_A17 airfoils decrease by 18%, 56.3%, and 60.1%, respectively; the drag coefficients increase by 40.9%, 22.2%, and 12%, respectively. This change indicates that icing leads to a decrease in the blade’s lift coefficient and an increase in its drag coefficient. Moreover, as the icing duration extends, the icing severity of the blades gradually intensifies, resulting in a gradual increase in the magnitude of the decrease in lift coefficient and the increase in drag coefficient.

Figure 22.

Lift–drag coefficients of blade airfoil segments after icing at different icing times. (a) Lift coefficients. (b) drag coefficients.

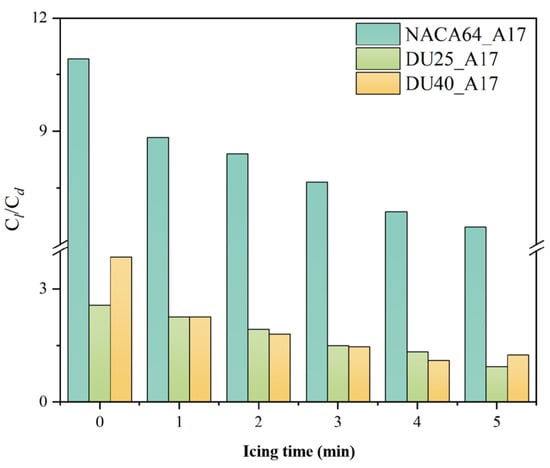

Figure 23 presents the variation law of the lift-to-drag ratio of blade airfoil sections under different icing durations. It can be observed from the figure that in the ice-free state, the lift-to-drag ratios of the NACA64_A17, DU25_A17, and DU40_A17 airfoils are 10.91, 2.56, and 3.84, respectively, representing the strongest aerodynamic performance. However, with the increase in icing duration, the lift-to-drag ratio gradually decreases. When the icing duration is 5 min, the lift-to-drag ratios of the three airfoils decrease to 6.45, 0.94, and 1.24, respectively. Compared with the ice-free state, the lift-to-drag ratios decrease by 40.8%, 63.2%, and 67.7%, respectively. Furthermore, the longer the icing duration, the more severe the decrease in lift-to-drag ratio and the worse the aerodynamic performance.

Figure 23.

Lift–drag ratio of blade airfoil segments after icing at different icing times.

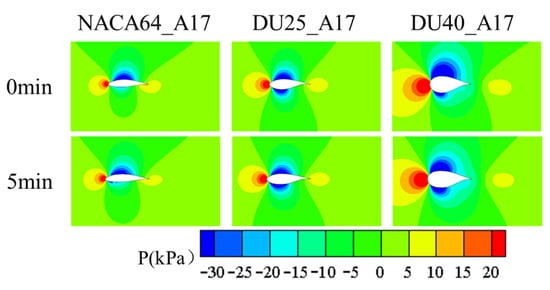

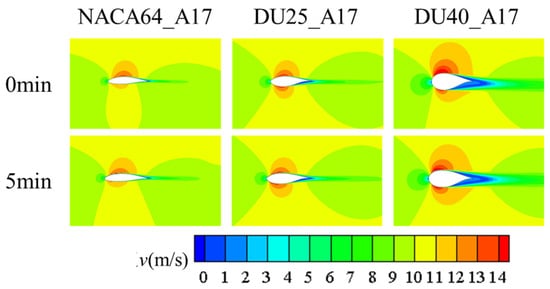

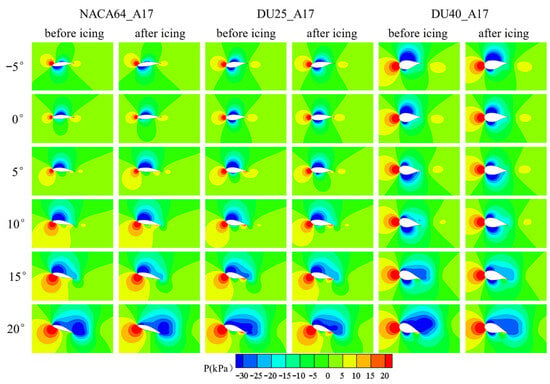

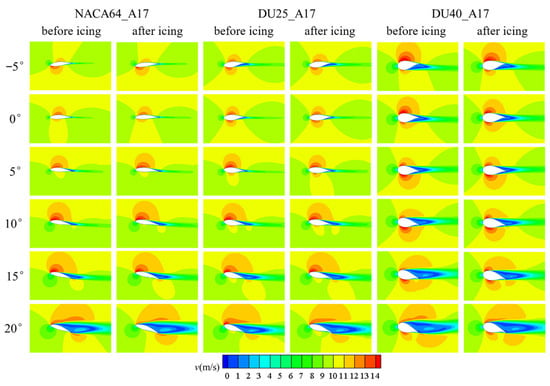

Figure 24 and Figure 25, respectively, show the pressure distribution and velocity distribution of the blade airfoil sections after icing for the NACA64_A17, DU25_A17, and DU40_A17 airfoils under different icing durations. From the pressure distribution, it can be observed that in the ice-free state, the surface pressure distribution of the three airfoils is relatively smooth: the pressure in the leading edge region is relatively high, while that in the trailing edge region is relatively low, and there are large-area negative pressure regions on the upper and lower airfoil surfaces—this is consistent with conventional aerodynamic characteristics. However, with the extension of icing duration, the gradual accumulation of ice layers results in significant changes in the aerodynamic characteristics of the blade surface. The continuous increase in ice layer thickness causes the surface pressure distribution of the blade to gradually deteriorate, especially the significant reduction in the pressure difference between the upper and lower airfoil surfaces. As can be seen from the velocity field distribution diagrams, under icing conditions, the irregular shape caused by icing changes the flow state of the surrounding airflow, increasing the frictional resistance of the airflow adhering to the airfoil surface and reducing the airflow velocity close to the icing area. Additionally, the irregularity of the ice formation creates small protrusions on the blade surface, which further disrupts the smooth flow of air and reduces the aerodynamic performance of the blades. This finding aligns with the conclusions of J. Revstedt et al., who discovered that ice formation significantly affects the lift and drag characteristics of airfoils [25].

Figure 24.

Pressure distributions in blade airfoil segments at different icing times.

Figure 25.

Velocity distributions of blade airfoil segments at different icing times.

3.2.2. Influence of Blade Material

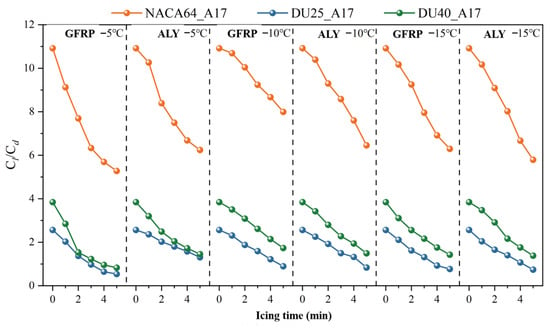

Figure 26 illustrates the variation law of lift and drag coefficients of blade airfoil sections after icing under different blade materials. As shown in Figure 26a, at ambient temperatures of −10 °C and −15 °C, the variation range of the lift coefficient of aluminum alloy blades is consistently higher than that of GFRP blades, and this gap gradually narrows as the temperature decreases. This indicates that at −10 °C and −15 °C, icing has a more severe impact on the aerodynamic performance of aluminum alloy blades; however, as the temperature further decreases, the influence of blade materials on the aerodynamic performance under icing conditions tends to weaken. It is noteworthy that at an ambient temperature of −5 °C, the lift coefficient of GFRP blades is significantly lower than that of aluminum alloy blades. This is mainly because at relatively high ambient temperatures, ice runback is prone to form on GFRP blades during icing. The presence of ice runback may cause flow separation, disrupting the originally stable lift-generation mechanism and leading to a decrease in the lift coefficient. As presented in Figure 26b, at ambient temperatures of −10 °C and −15 °C, the increase in amplitude of the drag coefficient of aluminum alloy blades is significantly larger than that of GFRP blades. However, at an ambient temperature of −5 °C, the presence of ice runback disrupts the smooth airflow streamline over the blade, preventing airflow from flowing stably across the blade surface and causing strong turbulence and separation phenomena. Taking the DU40_A17 airfoil as an example, the drag coefficient of the GFRP blade increased by 227%, while that of the aluminum alloy blade increased by 141%. This demonstrates that ice runback exerts a significant impact on the airfoil’s drag coefficient; when ice runback occurs on the blade surface during icing, the aerodynamic performance loss is substantial.

Figure 26.

Lift–drag coefficients of blade airfoil segments after icing for different blade materials. (a) Lift coefficients. (b) Drag coefficients.

Figure 27 shows the variation in the lift-to-drag ratio of airfoil sections after icing for different blade materials. As shown in the figure, at an ambient temperature of −5 °C and an icing duration of 5 min, the lift-to-drag ratios of GFRP blades for the NACA64_A17, DU25_A17, and DU40_A17 airfoils decreased by 51.6%, 79.2%, and 78.6%, respectively, while those of aluminum alloy blades decreased by 42.8%, 49.2%, and 62.2%, respectively. This difference indicates that at relatively high ambient temperatures, the aerodynamic performance of GFRP blades is more severely affected by icing. This is mainly attributed to the fact that irregular ice runback structures are more likely to form on the surface of GFRP blades; the protrusions of ice runback increase surface roughness and flow disturbance, advancing flow separation, which in turn reduces lift, significantly increases drag, and ultimately leads to a sharp decrease in the lift-to-drag ratio. However, when the ambient temperature decreases to −10 °C and −15 °C, the ice runback phenomenon no longer occurs, and the ice layer on the blade surface is more uniform and similar to the airfoil’s geometric shape. Although this streamlined icing still affects aerodynamic performance, its impact is relatively smaller compared to the turbulence and flow separation caused by ice runback. At this point, the decrease in amplitude of the lift-to-drag ratio of aluminum alloy blades exceeds that of GFRP blades, which is due to the high thermal conductivity of aluminum alloy. In low-temperature environments, aluminum alloy blades can transfer the heat of supercooled water droplets to the blade surface more quickly, promoting faster accumulation of the ice layer and resulting in a significant increase in icing amount—thus leading to more severe degradation of aerodynamic performance. To summarize, under different ambient temperatures, blade materials exert a significant influence on the aerodynamic performance of blades after icing. At relatively high temperatures, the lift-to-drag ratio of GFRP blades decreases more significantly due to the formation of ice runback, whereas at relatively low temperatures, aluminum alloy blades exhibit a larger decrease in amplitude in lift-to-drag ratio, which is attributed to their more severe icing condition.

Figure 27.

Lift–drag ratio of blade airfoil segments after icing with different blade materials.

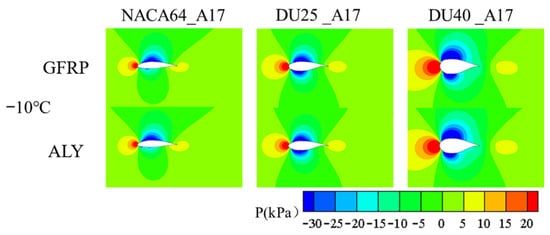

Figure 28 and Figure 29, respectively, show the pressure distribution and velocity distribution of the NACA64_A17, DU25_A17, and DU40_A17 airfoils under different blade materials after 5 min of icing. As can be seen from the pressure distribution diagrams, at an ambient temperature of −10 °C, the icing characteristics on the blade surface change and the ice layer tends to distribute uniformly. Compared to clean, ice-free blades, the pressure difference between the upper and lower airfoil surfaces of all three airfoils increases. However, at relatively low ambient temperatures, the area of the negative pressure region of aluminum alloy blades is larger than that of GFRP blades, which further confirms that aluminum alloy blades are more severely affected by icing in low-temperature environments. The velocity distribution diagram reveals the significant impact of ice runback on the flow field. After icing, large-area, low-velocity regions form on the lower airfoil surface and trailing edge region of the airfoil. At this point, the icing severity of aluminum alloy blades is more significant, the flow separation point is closer to the blade leading edge, and the aerodynamic performance deteriorates more noticeably.

Figure 28.

Pressure distribution of blade material on blade airfoil segments after icing.

Figure 29.

Velocity distribution of blade material on blade airfoil segments after icing.

3.2.3. Influence of Blade Angle of Attack

Figure 30 shows the variation in lift and drag coefficients of blade airfoil sections after icing under different blade angles of attack. Taking the NACA64_A17 airfoil as an example, at angles of attack ranging from −5° to 20°, the lift coefficients of the clean airfoil are −0.229, 0.249, 0.552, 0.917, 1.021, and 0.972, respectively; the corresponding drag coefficients are 0.024, 0.022, 0.045, 0.059, 0.106, and 0.230, respectively. After 5 min of icing, the lift coefficients of the NACA64_A17 airfoil decrease by 0.013, 0.045, 0.079, 0.052, 0.112, and 0.178, respectively, while the drag coefficients increase by 0.011, 0.009, 0.009, 0.019, 0.013, and 0.015, respectively. This change indicates that icing increases the surface roughness of the blade, significantly impairs the lift performance of the blade, and simultaneously increases drag—thereby undermining the aerodynamic performance of the airfoil. From the figure, it can be observed that the lift coefficients of the NACA64_A17 and DU25_A17 airfoils exhibit a typical trend of first increasing and then decreasing as the angle of attack increases. With the increase in the angle of attack, the lift coefficient gradually increases. Z. Maleksabet et al. found that the lift of iced airfoils decreased significantly, and the ice layer substantially increased drag, leading to a deterioration in aerodynamic performance, consistent with their research findings [26].

Figure 30.

Lift–drag coefficients of blade airfoil segments after icing at different angles of attack. (a) Lift coefficients. (b) Drag coefficients.

However, the variation trend of the lift coefficient of the DU40_A17 airfoil differs from that of the two aforementioned airfoils, exhibiting an atypical characteristic of first decreasing and then increasing. This phenomenon is highly consistent with previous research findings on the DU40 airfoil [27], which verifies the accuracy of the data in this study. The main reason for this phenomenon lies in the change in Reynolds number [28]. For thicker airfoils such as the DU40_A17, a change in Reynolds number induces negative effects, namely a decrease in lift coefficient and a reduction in stall angle. Therefore, the aerodynamic performance of the DU40_A17 airfoil exhibits a trend different from that of conventional airfoils, resulting in a lift coefficient that first decreases and then increases. Furthermore, the drag coefficients of all three airfoils increase with the increase in the angle of attack.

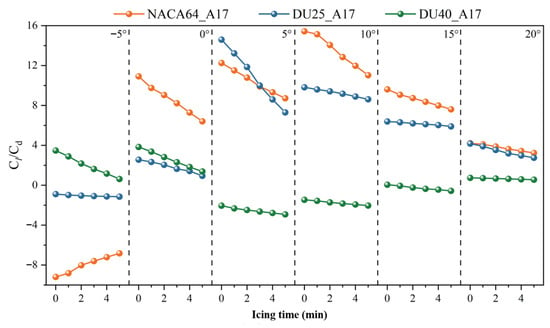

Figure 31 presents the variation in the lift-to-drag ratio of blade airfoil sections after icing for the three airfoils under different blade angles of attack. As shown in the figure, the lift-to-drag ratios of the NACA64_A17 and DU25_A17 airfoils exhibit a trend of first increasing and then decreasing with the increase in the angle of attack, while the lift-to-drag ratio of the DU40_A17 airfoil shows an atypical trend of first decreasing and then increasing as the angle of attack increases. At angles of attack ranging from 0° to 20°, the lift-to-drag ratios of the three airfoils demonstrate a downward trend with the extension of icing duration. However, at an angle of attack of −5°, the lift-to-drag ratio of the NACA64_A17 airfoil exhibits an upward trend, which deviates from the variation law observed at other angles of attack. The main reason for this abnormal phenomenon lies in the relative changes between the lift coefficient and the drag coefficient. At an angle of attack of −5°, the lift coefficient of the NACA64_A17 airfoil is negative, indicating that the blade generates a downward force at this condition while the drag coefficient remains positive. The icing process leads to a reduction in the absolute value of the negative lift coefficient, accompanied by an increase in the drag coefficient. Nevertheless, due to the small initial value of the negative lift coefficient, the change in lift caused by icing is relatively limited, and the magnitude of the drag increase fails to fully offset the effect of lift reduction. Therefore, the lift-to-drag ratio exhibits an upward trend instead under this specific angle of attack. This phenomenon underscores the complex impact of icing on aerodynamic performance under non-standard angles of attack and special aerodynamic conditions.

Figure 31.

Lift–drag ratio of blade airfoil segments after icing at different blade angles of attack.

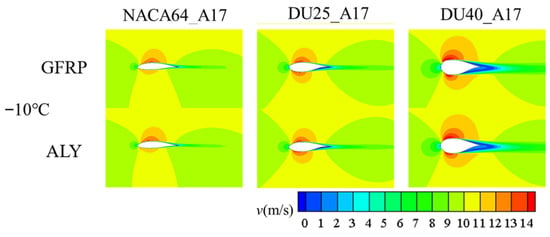

Figure 32 and Figure 33, respectively, show the pressure distribution and velocity distribution of the three airfoils before and after icing under different angles of attack. From the pressure distribution diagrams, it can be observed that the variation in the blade angle of attack significantly affects the position and distribution of positive and negative pressure regions on the blade surface. As the angle of attack gradually increases, the area of the positive pressure region on the lower airfoil surface expands continuously; in contrast, the negative pressure region on the upper airfoil surface gradually extends from being distributed only near the leading edge to covering the entire airfoil surface. Such changes in positive and negative pressure regions directly affect the lift and drag characteristics of the blade. At small angles of attack, the local negative pressure at the leading edge is the main source of lift; as the angle of attack increases, the negative pressure region extends backward, further increasing the lift. However, when the angle of attack continues to increase, flow separation may occur on the upper airfoil surface, leading to irregular expansion of the negative pressure region and a slowdown or even decrease in lift growth. L. Gao et al. demonstrated that ice layer structures at different attack angles can cause severe airflow separation, thereby affecting blade aerodynamic performance, which is identical to the findings of this study [29]. Meanwhile, the increase in positive pressure on the lower airfoil surface may cause an increase in drag, disrupting the aerodynamic balance of the blade. When icing occurs on the blade, ice protrusions alter the airflow attachment state. On the upper airfoil surface, icing expands the coverage of the negative pressure region, but the intensity of the negative pressure is significantly reduced—this means that although the range of the negative pressure region increases, the actual lift-generating effect decreases. On the lower airfoil surface, icing forms local high-pressure regions, particularly at the ice protrusions. These high-pressure regions increase pressure drag, further deteriorating the blade’s aerodynamic performance. From the velocity distribution diagrams, it can be seen that at small angles of attack, the airflow distribution around the blade airfoil is relatively stable, with no obvious flow separation; the low-velocity region on the blade surface is relatively small. As the angle of attack increases, the airflow at the blade trailing edge gradually detaches from the surface, forming obvious flow separation. This leads to an expansion of the low-velocity region at the airfoil trailing edge and a decline in aerodynamic performance. When icing occurs, the ice layer on the blade surface destroys the original smooth aerodynamic profile, forming irregular protrusions and rough surfaces. These irregular structures cause airflow to separate earlier on the blade surface, especially near the leading edge and mid-airfoil section. The presence of the ice layer not only significantly expands the range of flow separation but also extends the low-velocity region toward the front of the airfoil, resulting in a further decrease in lift and a significant increase in drag. In summary, icing significantly intensifies the flow separation effect caused by increasing angles of attack, leading to more severe deterioration of the blade’s aerodynamic performance.

Figure 32.

Pressure distribution of blade airfoil segments after icing at different angles of attack.

Figure 33.

Velocity distribution of blade airfoil segments after icing at different angles of attack.

4. Conclusions

By combining icing wind tunnel tests and numerical simulations, this study investigates the icing distribution characteristics on wind turbine blade surfaces and the variation law of aerodynamic performance after icing. Results show that at relatively high ambient temperatures, GFRP blades are more prone to ice runback formation during icing, and the severity of icing is significantly higher than that of aluminum alloy blades. Under the same icing environment, variations in airfoil type lead to differences in icing severity—this indicates that the ice resistance capability of a blade airfoil is related to its own geometric parameters. Specifically, the larger the maximum relative thickness of the airfoil and the closer its relative position to the blade leading edge, the stronger the airfoil’s ice resistance; conversely, the weaker the ice resistance. With the increase in icing duration, the aerodynamic performance of the blade decreases continuously. When the icing duration is 5 min, the maximum decrease in lift coefficient of the airfoil reaches 60.1%, the maximum increase in drag coefficient is 40.9%, and the maximum decrease in lift-to-drag ratio amounts to 67.7%. At relatively high ambient temperatures, the aerodynamic performance of aluminum alloy blades after icing is better than that of GFRP blades; however, at relatively low ambient temperatures, the aerodynamic performance of GFRP blades after icing is superior to that of aluminum alloy blades. Moreover, the lower the ambient temperature, the smaller the gap in aerodynamic performance between blades of different materials. This study can provide a basis for improving the stability and efficiency of wind turbines under extreme climate conditions and promoting the sustainable development of the wind power industry in cold regions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.W., R.Z., Z.L. and Y.L.; Methodology, T.W., D.L. and Y.L.; Validation, C.W., C.J. and T.W.; Formal analysis, D.L.; Investigation, R.Z. and Z.L.; Resources, C.J., T.W. and R.Z.; Data curation, Y.L.; Writing—original draft, C.W., Z.L. and Y.L.; Visualization, C.J. and D.L.; Funding acquisition, C.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Huaneng Group Science and Technology Project “Research on Health Prediction and Life Assessment Technology for Long-Flexible Blades of Large-MW Wind Turbine Units Based on Multi-Section Dynamic Loads and Audio-Video Information” (HNKJ23-H29).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jung, C.; Schindler, D. Efficiency and effectiveness of global onshore wind energy utilization. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 280, 116788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukenmez, N.; Yuksel, Y.E.; Ozturk, M. Design and thermodynamic analysis of a solar-wind energy-based combined system for cleaner production of hydrogen with power, heating, hot water and clean water. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 94, 256–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitassa, B.; Yenlide, T. Does homeownership promote households’ consumption of clean energy in Togo? Energy Build. 2025, 346, 116240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadorsky, P. Wind energy for sustainable development: Driving factors and future outlook. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 289, 125779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.; Schindler, D. Global future onshore wind energy droughts intensify under climate change. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 523, 146391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desalegn, B.; Gebeyehu, D.; Tamrat, B.; Tadiwose, T.; Lata, A. Onshore versus offshore wind power trends and recent study practices in modeling of wind turbines’ life-cycle impact assessments. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2023, 17, 100691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Z.; Caglar, A.E.; Pinzon, S. Pathways to decarbonization: Assessing the influence of government effectiveness, economic dynamics, and wind and solar energy adoption on CO2 emissions. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 394, 127413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Luo, Y.; Li, P.; Chang, R.; Liao, Z.; Huang, L. Systematic evaluation of transformer-based time series forecasting models for post-processing WRF-simulated wind speed and predicting short-term power output. Appl. Energy 2026, 403, 127070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Li, C.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, L.; Zhang, M. A novel framework for temporal super-resolution of wind in urban energy applications. Renew. Energy 2026, 256, 124336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Guo, S.; Chen, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H. Icing diagnosis method of wind turbine blade based on mechanism and data driving. Renew. Energy 2025, 255, 123820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Hu, Q.; Jiang, X.L. A Review of Wind Turbine Icing and Anti/De-Icing Technologies. Energies 2024, 17, 2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yao, F.; Tu, H.; Peng, S.; Huang, M.; Liu, M.; Mei, J.; Wang, J. One-piece insulating superhydrophobic photothermal coating for suppression of icing and thermal aging of wind turbine blades. Prog. Org. Coat. 2025, 209, 109630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quayson-Sackey, E.; Nyantekyi-Kwakye, B.; Ayetor, G.K. Technological advancements for anti-icing and de-icing offshore wind turbine blades. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2025, 231, 104400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, M.C.; Ahsbahs, T.; Langreder, W.; Thøgersen, M.L. On the modelling chain for production loss assessment for wind turbines in cold climates. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2023, 216, 103989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Song, X.; Tang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Li, Y.; Jia, Y.; Cai, C.; Li, Q.A. Fault diagnosis of wind turbine blade icing based on feature engineering and the PSO-ConvLSTM-transformer. Ocean Eng. 2024, 302, 117726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamraoui, F.; Fortin, G.; Benoit, R.; Perron, J.; Masson, C. Atmospheric icing impact on wind turbine production. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2014, 100, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ye, H. Multifunctional wearable protective fabrics for wind turbine blades: Triple-functional co-design of electrothermal de-icing/anti-icing, pressure sensing, and environmental protection. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 520, 165690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Yao, F.; Huang, H.; Tang, Q.; Tu, H.; Wang, J. Low-light/low-power de-icing composite coatings with thermal insulation and tunable optical radiation absorption for all-weather anti-icing of wind turbine blades. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 512, 162061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Xiao, F.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, J. An expert features enhanced temporal and contextual contrasting learning model for detecting wind turbine blade icing. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 160, 111745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Zhang, S.P.; Shen, G.Q.; Zhou, L. Acoustic emission-based wind turbine blade icing monitoring using deep learning technology. Renew. Energy 2025, 247, 122980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germeshausen, R.; Heim, S.; Wagner, U.J. Support for renewable energy: The case of wind power. J. Public Econ. 2025, 250, 105468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Zhang, F.; Li, Y.; Guo, W.; Feng, F. An experimental study on icing distribution and adhesion characteristics of wind turbine blades in saltwater Condition. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2026, 170, 111575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resor, B.R. Definition of a 5Mw/61.5M Wind Turbine Blade Reference Model; U.S. Department of EnergyOffice of Scientific and Technical Information: Washington, DC, USA, 2013.

- Xu, Z.; Na, P.Y.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Z.X. Ice Distribution Characteristics on the DU25 and NACA63-215 Airfoil Surfaces of Wind Turbines as Affected by Ambient Temperature and Angle of Attack. Coatings 2024, 14, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revstedt, J.; Szasz, R.; Ivanell, S. LES and DES of flow and ice accretion on wind turbine blades. In Proceedings of the Conference on Modelling Fluid Flow (CMFF’25), the 19th International Conference on Fluid Flow Technologies, Budapest, Hungary, 26–29 August 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Maleksabet, Z.; Kozinski, J.; Tarokh, A. Impact of ice accretion on the aerodynamic characteristics of Wind turbine airfoil at low Reynolds numbers. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2025, 239, 104618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.H.; Chen, J.Z.; Lo, Y.L.; Fu, C.L. Numerical and Experimental Studies on the Aerodynamics of NACA64 and DU40 Airfoils at Low Reynolds Numbers. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.X.; Yang, K.; Zhang, L.; Bai, J.Y. Experimental study of Reynolds number effects on performance of thick CAS wind turbine airfoils. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2017, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, W.; Hu, H. An experimental study on the aerodynamic performance degradation of a wind turbine blade model induced by ice accretion process. Renew. Energy 2019, 133, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).