Abstract

With continuous breakthroughs in electrochromic technology, tungsten trioxide (WO3) thin films, as a core material in this field, are rapidly expanding their applications in smart windows, anti-glare automotive rearview mirrors, and adaptive optical lenses. Owing to its excellent electrochromic properties—including high optical modulation, short switching times, and high coloration efficiency—WO3 has become a research focus in the field of electrochromic devices. This review takes WO3 thin films as the research subject. It begins by introducing the crystal structure of WO3 and the ion/electron co-intercalation-based electrochromic mechanism and explains two key performance parameters for evaluating electrochromic properties: optical modulation amplitude and coloration efficiency. Subsequently, it provides a detailed review of recent advances in the preparation of WO3 thin films via physical methods (including sputtering deposition, evaporative deposition, and pulsed laser deposition) and chemical methods (including hydrothermal, sol–gel, and electrodeposition methods). A systematic comparison is made of the microstructure and electrochromic performance (optical modulation amplitude and coloration efficiency) of films prepared by different methods, and the interaction between WO3 film morphology and device structure is analyzed. Finally, the advantages and challenges of physical and chemical methods in tuning film properties are summarized, and the outlook of their application prospects in high-performance electrochromic devices is given. This review aims to provide guidance for the selection and process optimization of WO3 thin films with enhanced performance for applications such as smart windows, anti-glare rearview mirrors, and adaptive optical systems.

1. Introduction

With the continuous development of human society, energy demand continues to grow, leading to a rise in carbon dioxide emissions, which in turn releases approximately 10 billion tons of carbon into the atmosphere globally each year [1]. Buildings consume 30%–40% of the world’s primary energy; in absolute terms, building-related greenhouse gas emissions may reach around 15.6 million metric tons of CO2 equivalents by 2030 [2]. Most of this energy is used for lighting, cooling, heating, and electrical appliances, with roughly 30% of it being lost through windows [3]. Therefore, the rational use of resources and the research and development of technologies related to low energy consumption have become extremely urgent. To achieve reduced energy consumption and improved energy utilization efficiency, electrochromic technology—capable of adjusting visible light transmittance according to human needs—has provided a brand-new solution for energy conservation in modern buildings [4].

The electrochromic phenomenon is one of great research value. Electrochromic devices that achieve light modulation and charge storage using this effect have attracted significant attention, with their application fields covering smart building windows [5,6], low-power displays [7], anti-glare automotive rearview mirrors [8], military camouflage [9,10], and more. In the commercial sector, examples such as anti-glare rearview mirrors, electrochromic portholes in the Boeing 787 Dreamliner [11], and Ambilight Inc. providing large-area electrochromic sunroofs for electric vehicles [12] demonstrate that electrochromic devices have broad application prospects and significant market demand.

Electrochromism refers to the phenomenon where a material undergoes reversible and stable changes in its optical properties under the action of an external voltage [13]. Electrochromic materials are mainly classified into two categories: organic and inorganic. Organic materials such as polyaniline (PANI) [14] and poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) [15] typically feature fast response times and a wide range of color changes, but they often exhibit poor long-term stability and durability. By contrast, inorganic materials are more favored due to their excellent stability, ease of processing, and mature preparation techniques, especially transition metal oxides like vanadium pentoxide (V2O5) [16], titanium dioxide (TiO2) [17], nickel oxide (NiO) [18], and tungsten trioxide (WO3) [19]. Compared with other transition metal oxides, WO3 demonstrates superior stability and optical modulation performance.WO3 has attracted significant attention in the electrochromic field due to its advantages, such as high coloration efficiency, excellent optical modulation performance, and good chemical stability [20,21,22,23]. Meanwhile, WO3 is characterized by abundant raw materials and environmental friendliness; its preparation processes are highly compatible with modern industrial technologies, enabling the low-cost fabrication of large-area uniform thin films. This perfect integration of performance and practicality has allowed it to be successfully applied in several key fields: in the field of energy-efficient buildings, WO3 is integrated into smart window systems, realizing intelligent temperature control and daylight management for buildings by adjusting the transmittance of visible light and near-infrared light; in the transportation sector, it is used to manufacture anti-glare rearview mirrors and portholes for automobiles and aircraft, enhancing the safety and comfort of driving and flight; in the field of information display, as a core material for low-power displays, it is applied in scenarios such as electronic price tags and smart labels; furthermore, it also demonstrates unique value in cutting-edge fields including adaptive optical lenses and military camouflage devices, fully highlighting its broad application potential as a core electrochromic material.

Furthermore, WO3 demonstrates significant potential as a highly effective additive for enhancing the performance of various materials and devices. This capability stems from its diverse crystal structures, mechanical compatibility (e.g., facilitating grain refinement via grinding), and stable chemical properties. Its application prospects extend far beyond the field of electrochromism. For instance, in 2024, Alua K. Alina et al. [24] investigated the functionality of WO3-based composite ceramics, revealing their application potential in areas such as photocatalysis, ceramic fabrication, and optical regulation. In 2024, Odeilson Morais Pinto et al. [25], through a review of WO3 nanostructures prepared by various synthesis methods, highlighted their applications in gas sensing, photocatalysis, energy storage, and biomedicine. This versatility as a functional enhancer further solidifies the core status of WO3 in the field of advanced functional materials. We have listed some characteristics of WO3 materials, all of which are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

WO3 Material Properties.

This paper focuses on the electrochromic properties of WO3 thin films and takes WO3 as the research object, introduces its structure and electrochromic mechanism, reviews the research progress in the preparation of WO3 thin films via physical methods (including sputtering deposition, evaporation deposition, and pulsed laser deposition) and chemical methods (including hydrothermal method, sol–gel method, and electrodeposition method) in recent years, and analyzes the effects of different preparation methods under physical methods, as well as those under chemical methods on the electrochromic properties of WO3 thin films, while further providing clear reference bases and directional guidance for subsequent research on the optimization of WO3 thin film preparation processes, the regulation of electrochromic properties, and industrial applications: on the one hand, it helps researchers efficiently select suitable preparation technologies based on the performance requirements of target application scenarios (e.g., smart windows need to balance light transmittance adjustment range and response speed, while photodetectors need to focus on thin film uniformity and stability)—for instance, sputtering deposition can be preferred for preparing highly dense thin films, and the sol–gel method can be emphasized for low-cost large-scale production; on the other hand, it lays a systematic research foundation for further exploring the intrinsic structure–activity relationship between “preparation process-microstructure-electrochromic property” and developing new modification strategies (such as multi-method composite preparation and hetero-element doping), thereby facilitating the advancement of WO3-based functional materials towards a breakthrough in practical application with higher performance, lower cost, and greater stability and durability.

Several excellent reviews have summarized the progress in WO3 electrochromic films. For instance, the comprehensive work by [29] detailed various performance enhancement strategies up to 2022. Similarly, the review by [30] provided a valuable overview of the properties and applications of WO3 nanostructures. However, the field of WO3 electrochromism continues to advance rapidly, with significant developments emerging after the coverage of these prior reviews. This review distinguishes itself and provides a timely update by focusing on the following aspects:

- Unprecedented Timeliness;

We have included the latest research breakthroughs up to 2025, including novel doping strategies (e.g., Zn-doped and Nb-doped WO3) and advanced physical preparation methods such as glancing angle deposition (GLAD), which were not covered in earlier comprehensive reviews.

- 2.

- Method-Centric Performance Analysis;

While previous reviews often cover preparation methods, this work provides a more structured and comparative analysis of how specific process parameters in both physical and chemical methods (e.g., doping power in sputtering, precursor concentration in hydrothermal synthesis) directly influence the two core performance metrics: optical modulation amplitude (ΔT) and coloration efficiency (CE). This is systematically presented in comparative tables for each method.

- 3.

- Bridging Film Fabrication with Device Integration;

We have clearly analyzed the interaction between the morphology of WO3 thin films (resulting from different preparation methods) and the structure/performance of the final electrochromic devices. This provides key guidance for applied research and device engineering.

Based on the above points, this paper is not only an update on the latest materials and technologies but also a practical guide for selecting and optimizing preparation methods according to specific application requirements to achieve target electrochromic performance.

2. Structure of WO3

In general, electrochromic materials can be classified into three categories: organic electrochromic materials, inorganic electrochromic materials, and hybrid electrochromic materials [31,32,33,34]. In the research of electrochromic smart windows, WO3, as an n-type semiconductor material with a band gap of 2.5–2.7 eV, has become a research hotspot due to its excellent electrochromic properties [35,36]. These properties include high optical modulation amplitude, high coloration efficiency (CE), fast switching speed (short coloring/bleaching time), and excellent cyclic stability.

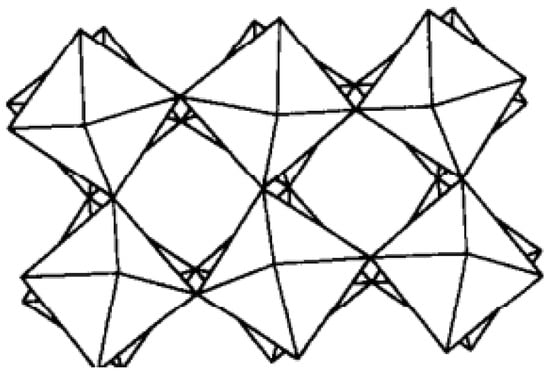

In terms of stoichiometry, WO3 is a simple compound, but its variations in phase transitions and structure are relatively complex. The ideal structure of WO3 is a cubic structure similar to that of rhenium trioxide (ReO3). However, WO3 is reported [37,38,39,40,41] to be tetragonal above 720 °C, orthorhombic from 320 °C to 720 °C, monoclinic from 17 °C to 320 °C, and triclinic below 17 °C. Another phase transition for WO3 apparently occurs at about −40 °C. As shown in Figure 1 [42], the structure is the monoclinic phase of WO3.

Figure 1.

The monoclinic phase of WO3 (adapted from [42], with permission).

The crystal structure of WO3 is a distorted form of the cubic structure of ReO3 [43]: Tungsten atoms are located at the corners of the cube, while oxygen atoms are situated along the edges of the cube. Each tungsten atom is surrounded by six oxygen atoms, forming an octahedral structure. The slight relative rotation between these octahedra, as well as the unequal bond lengths in octahedral coordination, leads to lattice distortion and a reduction in crystal symmetry [43,44]; meanwhile, the displacement of tungsten atoms inside the octahedra can be stabilized by an increase in the degree of covalent bonding between tungsten and oxygen atoms [45]. It should be noted that although these octahedra do not undergo severe distortion, the off-center displacement of tungsten atoms and the rotation of octahedra collectively form rhombohedral cages, as illustrated in Figure 2 [46]. In tungsten bronzes, these cages serve as occupation sites for small cations such as H, Li, or Na; they also form channels that facilitate the rapid diffusion of these small cations.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the monoclinic WO3 structure. Oxygen atoms are shown in black, and the corner-sharing WO6 octahedra are shaded (adapted from [46], with permission).

3. Electrochromic Properties of WO3

3.1. The Mechanism of the Electrochromic Effect

WO3 has attracted much attention in the field of electrochromism due to its excellent electrochromic properties and material stability. At present, the most common explanatory theory regarding the electrochromic mechanism is the dual injection model of cations and electrons proposed by Brian W. Faughnan [47]. The specific reaction formula is as follows:

WO3 + xM+ +xe− ↔ MxWO3

In the above formula, M+ represents small-radius cations such as H+, Li+, Na+, etc.

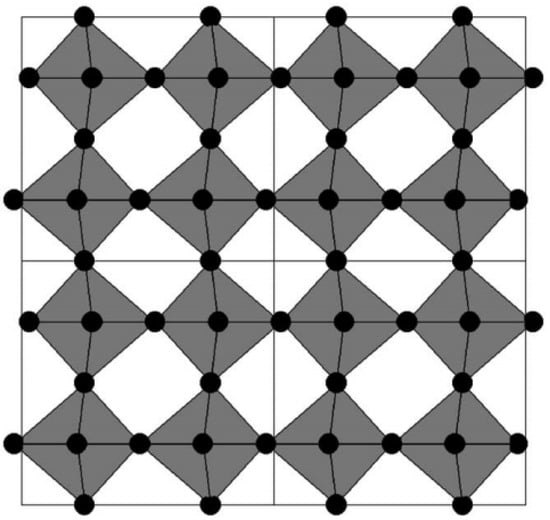

When a negative voltage is applied to the electrochromic layer, as shown in Figure 3a, cations and electrons enter the thin film simultaneously to undergo a redox reaction, generating a tungsten bronze structure, and the thin film changes from colorless to blue [48]; when a positive voltage is applied to the electrochromic layer, as shown in Figure 3b, cations and electrons are extracted from the thin film, W5+ is oxidized toW6+, and the thin film returns to its original colorless and transparent state.

Figure 3.

(a) Coloring process of WO3 film; (b) fading process of WO3 film.

3.2. Electrochromic Properties

The evaluation of the electrochromic properties of WO3 covers various indicators such as optical modulation amplitude, coloration efficiency, cyclic stability, and response time. In this paper, the performance of WO3 is mainly evaluated by optical modulation amplitude and coloration efficiency. At the end of this section, the reason why only the optical modulation amplitude and coloration efficiency are selected as the evaluation indicators for electrochromic properties will be explained.

- •

- Optical Modulation Amplitude

The visible light wavelength range is between 380 and 780 nm, and light of different wavelengths exhibits different colors. Optical Modulation Amplitude is the fundamental parameter for characterizing the color-switching capability of electrochromic materials or devices [49]. It refers to the difference in optical transmittance between the bleaching state and coloration state of an electrochromic film at a certain wavelength. The spectral variation values at wavelengths of 632.8 nm or 550 nm are often used as the electrochromic optical modulation range. The better the electrochromic performance of a material, the larger its optical modulation range. The general calculation formula for optical modulation amplitude is as follows:

ΔT (%) = Tb − Tc

In the formula, Tb represents the transmittance in the bleaching state, with the unit of %; Tc represents the transmittance in the coloration state, with the unit of %. This property can be measured using a UV-vis spectrophotometer under an applied voltage [50]. The transmittance in the colored and bleached states is recorded, and ΔT is calculated from these values using Equation (2).

- •

- Coloration Efficiency

The coloration efficiency (CE) reflects the change in the optical absorption intensity (A) brought about by the unit intercalated charge (Q) of the electrochromic material. It quantifies the relationship between the optical modulation amplitude achieved at a specific absorption wavelength and the amount of charge injected into the device, with this relationship normalized by the active area of the electrochromic material [51]. According to the Beer–Lambert law, there is the following formula:

CE (cm2/C) = ΔOD/Q = log(Tb/Tc)/Q

In the formula, ΔOD is the change in optical density; Q represents the amount of charge changed per unit area, while Tc and Tb correspond to the transmittances of the electrochromic film or device in the colored and bleached states at a specific wavelength, respectively. The calculated coloration efficiency (CE) has a unit of cm2/C. This property can be evaluated by performing electrochemical and optical measurements using an electrochemical workstation and a UV-vis spectrophotometer [52]. The current–time curve is recorded during the entire coloring process, and the total injected charge (Q) is obtained by integrating this curve. The optical density (OD) is then calculated from the transmittance measured at 633 nm in both bleached and colored states, enabling the determination of the coloration efficiency (CE) using Equation (3). A higher coloration efficiency indicates that less charge is required to achieve the same optical modulation amplitude.

This review selects the optical modulation amplitude (ΔT) and coloration efficiency (CE) as the core performance metrics for systematic comparison, based on the following considerations:

- Fundamental and Universal

ΔT and CE are the two most fundamental and core parameters for evaluating all electrochromic materials. ΔT directly reflects the strength of a device’s ability to regulate light and serves as the primary objective for applications such as smart windows; CE, on the other hand, reflects the level of a device’s energy utilization efficiency and is a key factor in measuring its energy-saving benefits and economic performance. Nearly all relevant studies report these two parameters, which makes horizontal comparison possible between studies with different preparation methods and different doping strategies.

- 2.

- Accessibility and Consistency

Other important parameters, such as response time and cyclic durability, have vastly different testing standards and reporting methods across various studies. The measurement of response time depends on specific current density or switching threshold values, while the testing conditions and cycle counts for cyclic durability also vary from case to case. By contrast, the definitions and calculation methods of ΔT and CE are relatively consistent, and their data are more commonly reported and standardized in the literature, facilitating extraction and compilation.

- 3.

- Correlation and Causation

ΔT and CE are largely determined by the microstructure of the thin film and its electronic/ionic transport properties. Analyzing the impact of different preparation processes on these two parameters can effectively reveal the intrinsic correlation between “process-structure-property”, which lays a solid foundation for the selection of preparation methods in subsequent studies.

It is evident that the core electrochromic properties of WO3 thin films, such as optical modulation amplitude and coloration efficiency, are influenced by factors such as crystallinity, porosity, and specific surface area. With the widespread application of WO3 thin films in electrochromic devices, there is an increasing demand for their excellent electrochromic performance. Notably, the electrochromic performance of WO3 thin films is closely related to their preparation methods. For this reason, numerous researchers have conducted in-depth studies on preparation methods, and while significant progress has been made, many issues remain unresolved. Further research is therefore still required.

3.3. Key Testing Factors for ΔT and CE

When evaluating and comparing the electrochromic properties of WO3 thin films, it must be recognized that the values of optical modulation amplitude (ΔT) and coloration efficiency (CE) strongly depend on the testing conditions. Ignoring these conditions may lead to distorted performance rankings or misleading comparisons. The following are the key testing parameters that have the greatest impact on ΔT and CE:

- •

- Measurement Wavelength

Both ΔT and CE are wavelength-dependent. Consequently, the same thin film can exhibit significantly different values for these parameters at distinct wavelengths.

- •

- Electrolyte

The type of electrolyte determines the kinetics of ion insertion/extraction, charge balance, and interface stability and thus directly affects the values of ΔT and CE.

- •

- Potential Window

The applied voltage range for coloring and bleaching governs the driving force of the electrochemical reaction. An overly narrow window may result in incomplete coloring/bleaching, leading to an underestimated ΔT; conversely, an excessively wide window can induce side reactions (e.g., electrolyte decomposition), which compromise the calculated CE.

- •

- Film Thickness

The thickness of the thin film directly affects the sufficiency of coloration and ion migration paths. A film that is too thin has insufficient active material, resulting in low ΔT, while an excessively thick film exhibits high ion migration resistance, which may lead to incomplete internal coloration and similarly limit ΔT and reduce CE.

- •

- Number of Cycles

Whether performance data are measured at initial cycles or after hundreds or thousands of cycles is of crucial importance. The performance of electrochromic materials tends to degrade as the number of cycles increases. Specifying the number of cycles during testing is a key factor in evaluating the stability and practical performance of the materials.

In addition, the performance and structure of WO3 thin films are closely related to their preparation methods. For this reason, numerous researchers have conducted in-depth studies on preparation methods, and while significant progress has been made, many issues remain unresolved. Further research is therefore still required.

4. Research Progress on WO3 Thin Films

Thin film manufacturing technology is crucial for modern functional devices, as thin film materials can be integrated into complex structures to meet diverse application requirements. Among these materials, WO3 thin films, as an important type of electrochromic material, have been extensively studied and have demonstrated great potential in fields such as smart windows and energy-saving displays. The electrochromic performance of WO3 thin films is highly sensitive to preparation methods. Over the past few decades, WO3 thin films with excellent electrochromic performance have been successfully prepared via various physical and chemical methods. Therefore, in this paper, we will systematically review the different physical and chemical methods used for preparing WO3 thin films and discuss the relationship between these methods and the electrochromic performance of WO3 thin films.

4.1. Research Progress on WO3 Thin Films Prepared by Physical Methods

A physical method is a technique where the raw material itself does not undergo chemical changes; instead, it only undergoes a process of transitioning from solid to gas and then back to solid, with no complex chemical reactions involved in the film-forming process. The physical method encompasses a variety of preparation approaches, and this section focuses on discussing the research progress of three physical methods—sputtering deposition, evaporation deposition, and pulsed laser deposition—for preparing WO3 thin films.

4.1.1. Sputtering Deposition

First of all, it is necessary to point out that research on the equipment and principles of magnetron sputtering is rooted in the development of the sputtering process—the history of this process can be traced back to 1852, when sputtering was first used to prepare metallic films with the assistance of advancements in vacuum technology. Although early sputtering processes already had certain practical value, they had significant limitations, the most prominent of which included low deposition rates, low ionization efficiency, and excessive heating of substrates [53]. The invention of the planar magnetron cathode in 1974 successfully addressed these specific challenges, thereby driving the rapid development of magnetron sputtering technology. Today, this technology has been widely used in the preparation of various high-functionality industrial films [54].

Sputter deposition is a type of physical method that achieves thin film deposition through a sputtering process. Conventional sputtering methods can be used to prepare various materials such as metals, semiconductors, and insulators and have advantages including simple equipment, easy control, large coating area, and strong adhesion. In contrast, the magnetron sputtering method, developed in the 1970s, enables high-speed, low-temperature, and low-damage thin film deposition. By adding a closed magnetic field parallel to the target surface in a diode sputtering system, and utilizing the orthogonal electromagnetic field formed on the target surface to confine secondary electrons to specific regions on the target surface, it improves ionization efficiency, increases ion density and energy, and ultimately achieves high-rate sputtering. The above description defines the concept of magnetron sputtering clearly.

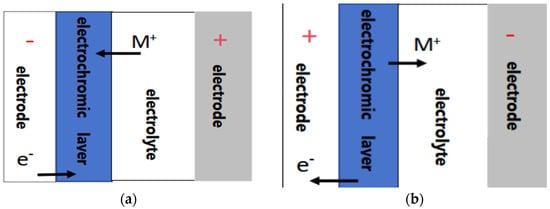

Magnetron sputtering is a type of sputter deposition, as it enables the mass production of thin films with relatively high purity and low cost. The core process of this technology involves ejecting material from the “target” (which serves as the material source) and depositing it onto the “substrate” (e.g., a silicon wafer), as specifically shown in Figure 4 [55].

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of magnetron sputtering (adapted from [55], with permission).

In 2016, M. Meenakshi et al. [56] prepared tungsten-vanadium mixed oxide thin films via radio frequency (RF) magnetron sputtering and conducted a systematic study to investigate the effect of doping concentration on the electrochromic performance of the films. Among all the samples, the tungsten oxide film doped with 2% V2O5 was confirmed to exhibit the optimal electrochromic response performance, with an optical modulation amplitude of 49.0% and a coloration efficiency of 66.75 cm2/C, making it highly suitable for smart window applications. However, the charge reversibility was limited to 59%, indicating incomplete ion extraction during bleaching.

In 2017, MD Peng et al. [57] prepared pure WO3 thin films, 5% Ti-doped WO3 thin films, and 10% Ti-doped WO3 thin films via radio frequency (RF) magnetron sputtering. The research results showed that at the initial stage of cycling, Ti doping had almost no interference with the optical transmittance of WO3 thin films in both the bleached state and the colored state, and the optical modulation amplitudes were nearly consistent. However, after 200 cycles, the optical modulation amplitude of the pure WO3 thin film was 9%, while that of the 5% Ti-doped WO3 thin film reached 20%. However, even the optimal Ti-doped film still suffered from significant performance decay over cycling.

In 2018, Yi Yin et al. [58] prepared gadolinium (Gd)-doped WO3 thin films via the radio frequency (RF) magnetron sputtering method. By combining thin film structural characterization and electrochemical analysis, they confirmed that the improvement in coloration efficiency could be attributed to the monoclinic Gd2O3 nanoislands formed on the surface of WO3: these nanoislands not only enhanced the charge capacity of the thin films but also accelerated their reaction kinetics. The research results showed that the WO3 thin films with moderate Gd doping (0.9%) exhibited excellent performance: the transmittance modulation amplitude reached as high as 76% at a wavelength of 800 nm, and the coloration efficiency achieved 68.3 cm2/C at a wavelength of 633 nm. However, excess Gd doping (>1%) lowers coloration efficiency, and the study does not investigate long-term cycling stability of the films.

In 2020, Y Ayauchi et al. [59] deposited WO3 thin films on indium tin oxide (ITO) thin films with different sheet resistances using a radio frequency (RF) magnetron sputtering system, and investigated their electrochromic properties in the visible and near-infrared regions. The experimental results showed that in the near-infrared region, the WO3 thin films on the high sheet-resistance ITO substrates exhibited superior electrochromic performance compared to those on the low sheet-resistance ITO substrates, with an optical modulation amplitude of 55%. However, the high sheet resistance may compromise the device’s electrical response speed and uniformity.

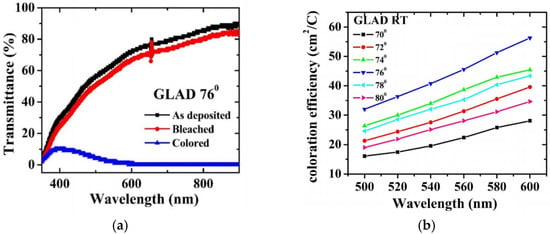

In 2023, KN Kumar et al. [60] prepared WO3 thin films using the glancing angle deposition (GLAD) direct current (DC) magnetron sputtering technique (GDMS), with the substrate tilt angle controlled between 70° and 80°. The experimental results showed that compared with the samples annealed at 400 °C, the sample prepared at a GLAD angle of 76° under room temperature exhibited higher coloration efficiency and optical modulation amplitude—specifically, the optical modulation amplitude was 85% and the coloration efficiency was 54.5 cm2/C. However, the highly porous amorphous structure may compromise the film’s mechanical durability and long-term stability. Relevant data are shown in Figure 5 [60].

Figure 5.

(a) Transmittance spectra of bleached, as-deposited, and colored states of WO3 thin films deposited at 76°; (b) CE of WO3 samples for room temperature (adapted from [60], with permission).

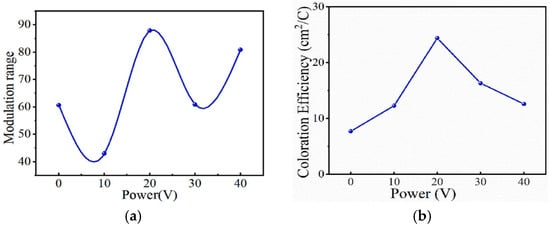

In 2025, Lan Zhang et al. [61] fabricated ZnO-doped WO3 thin films using the magnetron sputtering method. The experimental results show that with the increase in the doping power, the crystallinity, grain size, and surface roughness of the WO3 films increase, while the film thickness decreases. That is, ZnO doping significantly affects the surface morphology and structural properties of the WO3 films. Among them, the WO3 film with a doping power of 20 W exhibits the optimal electrochromic performance. Within the visible light spectrum (400–700 nm), the light modulation amplitude reaches 87.9% and the coloration efficiency is 24.4 cm2/C, showing a significant improvement compared to the undoped film. However, at high doping powers (e.g., 40 W), crystallinity and modulation amplitude decrease, and the flexible substrate curls at 50 W due to overheating, limiting further performance optimization. The relevant data are shown in Figure 6 [61].

Figure 6.

(a) Optical modulation range of thin films under different doping powers; (b) coloring efficiency of thin films under different doping powers (adapted from [61], with permission).

In 2025, Mak, Ali Kemal et al. [62] deposited pure WO3 thin films and doped WO3 thin films with doping ratios ranging from 2.0% to 3.9% via radio-frequency (RF) magnetron sputtering, and controlled the thickness of the thin films between 130 and 145 nanometers. Electrochromic characterization showed that the 3.9-doped WO3 thin film exhibited a maximum optical modulation value of 54.9% at 630 nm, with a coloration efficiency of 52.6 cm2/C. However, in the long-term stability test, the sample with the lowest doping amount (2.0%) showed better stability. However, samples with higher doping ratios (e.g., 3.9%) exhibited significantly reduced stability in long-term cycling tests, maintaining only about 150 cycles, which limits their practical application.

This section mainly introduces the research progress of preparing WO3 thin films by sputtering deposition, a physical fabrication method. We have compared and analyzed the electrochromic properties of WO3 thin films prepared via sputtering deposition, with specific details shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of optical modulation amplitude and coloration efficiency of WO3 thin films prepared by sputtering deposition under different conditions.

In summary, sputter deposition offers strong controllability over process parameters. For instance, in 2025, Lan Zhang et al. [61] systematically optimized the surface morphology and electrochromic properties of thin films by controlling the doping power of ZnO. This high level of controllability ensures good repeatability of experimental results, making it easy for industrial promotion. Meanwhile, this method exhibits broad material and substrate compatibility. For example, it has been successfully used to prepare WO3 thin films with various doping elements (including V, Mo, Ti, Gd, Nb, Zn) and different substrates (such as ITO conductive glass and FTO conductive glass).

4.1.2. Evaporation Deposition

Evaporative deposition is one of the core technologies in physical methods. It involves heating the material to be deposited to evaporate or sublimate it into gaseous particles, which then migrate to the substrate surface in a vacuum environment and condense to form a thin film after cooling. Its process can be divided into four key stages:

- (1)

- Heating and evaporation of the source material

- (2)

- Migration of gaseous particles

- (3)

- Condensation on the substrate surface

- (4)

- Thin film growth

Evaporative deposition is carried out in a high-vacuum environment (typically ≥ 10−3 Pa), which can effectively avoid the contact and reaction between air molecules and the WO3 source material, and greatly reduce the contamination of the thin film by impurity molecules. Meanwhile, the equipment for evaporative deposition is relatively low-cost, giving it an advantage in scenarios where high requirements are placed on the surface flatness of the thin film.

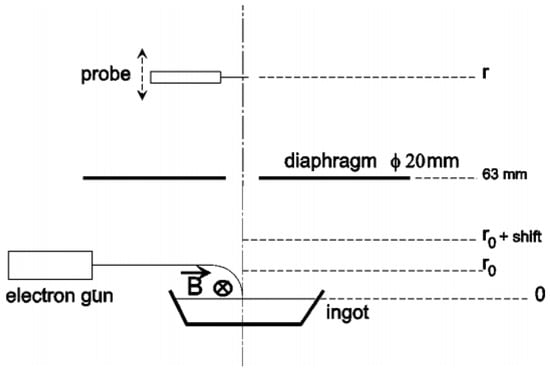

The device for electron beam evaporation, which belongs to evaporative deposition, is shown in Figure 7 [63].

Figure 7.

Schematic view of the experimental setup for a spot-sized electron beam evaporator (adapted from [63], with permission).

In 2018, KV Madhuri et al. [64] prepared WO3 thin films using the electron beam evaporation (EBE) technique under a vacuum of 2 × 10−5 mbar, with substrate temperatures (Ts) varying from room temperature to 450 °C. They also investigated the effect of substrate temperature on the growth and properties of the thin films. The results showed that the WO3 thin film prepared at RT exhibited a high coloration efficiency (CE) of 30.63 cm2/C and an optical modulation amplitude of 34% at a wavelength of 550 nm. As the substrate temperature increased, both the surface roughness and grain size of the thin films gradually increased. When the substrate temperature exceeded 250 °C, the coloration efficiency of the thin films decreased. However, when the substrate temperature exceeded 250 °C, the increased crystallinity of the films blocked ion insertion channels, leading to a significant drop in coloration efficiency to 17.20 cm2/C.

In 2019, Jui-Yang Chang et al. [65] mixed xLi2O-(1 − x)WO3 powders with WO3 and Li2O, pressed them into target pellets, and fabricated electrochromic films on indium tin oxide (ITO) glasses via electron beam evaporation at room temperature, with the film thickness being approximately 530 nm. When the doping ratio of Li2O was 1.58 wt.% (sample named LW2), the film exhibited the optimal ECD characteristics at a wavelength of 550 nm: an optical modulation amplitude of 53.1% and a coloration efficiency of 41.6 cm2/C. These results indicate that lithium oxide doping can effectively improve the colorability and electrochromic properties of tungsten trioxide electrochromic films. However, excessive Li2O doping (e.g., in the LW3 sample) leads to film densification, reduced ion mobility, and consequently a decrease in coloration efficiency and cyclic voltammetry area.

In 2020, MB Babu et al. [66] prepared WO3 thin films using the electron beam evaporation technique under an oxygen partial pressure of 2 × 10−4 mbar. During the experiment, the substrates were maintained at 6–8 °C and room temperature, respectively, and the as-prepared films were subsequently annealed at 400 °C in air for approximately 2 h. The study showed that all the prepared WO3 thin films had a monoclinic structure with different orientations. Moreover, the films deposited at 6–8 °C and then annealed exhibited a higher coloration efficiency (72.60 cm2/C) and a larger optical modulation amplitude (33.8%) compared to those deposited at room temperature. However, the low-temperature deposited films exhibited higher surface roughness (3.35 nm) and a larger optical band gap (2.965 eV), which may limit their performance in certain optoelectronic applications.

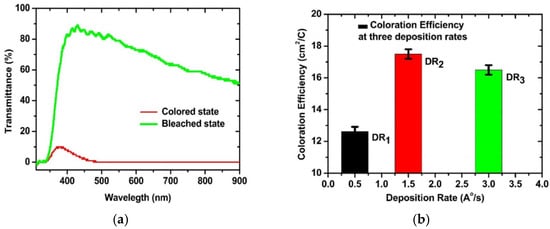

In 2022, J Gupta et al. [67] prepared WO3 thin films on substrates using the electron beam evaporation technique at three different deposition rates: 0.5 Å/s (angstroms per second), 1.5 Å/s, and 3 Å/s. The research results showed that all as-deposited WO3 thin films were amorphous. Among them, the film fabricated at a deposition rate of 1.5 Å/s achieved the highest coloration efficiency and diffusion coefficient, which were 17.50 cm2/C and 3.26 × 10−4 cm2/s, respectively. Additionally, this film exhibited an optical modulation amplitude of 79%. However, the film prepared at the optimal deposition rate (1.5 Å/s) exhibited a relatively limited optical modulation amplitude (79%) and an overall low coloration efficiency (17.50 cm2/C), which may restrict its application in high-performance electrochromic devices. Relevant data are shown in Figure 8 [67].

Figure 8.

(a) The transmittance of the coloured state and bleached state of the WO3 thin film prepared at a deposition rate of 1.5 Å/s; (b) values of coloration efficiency at different deposition rates (adapted from [67], with permission).

This section mainly introduces the research progress of preparing WO3 thin films by evaporative deposition, a physical fabrication method. We have compared and analyzed the electrochromic properties of WO3 thin films prepared via evaporative deposition, with specific details shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of Optical Modulation Amplitude and Coloration Efficiency of WO3 Thin Films Prepared by Evaporative Deposition Under Different Conditions.

Table 3.

Comparison of Optical Modulation Amplitude and Coloration Efficiency of WO3 Thin Films Prepared by Evaporative Deposition Under Different Conditions.

| Thin Film Type | Substrate | Optical Modulation Amplitude (ΔT%)/Wavelength | Coloration Efficiency (cm2/C)/Wavelength | Electrolyte | Potential Window | Thickness | Cycles | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WO3 | ITO-Coated Glass | 34.0%/550 nm | 30.63 cm2/C/550 nm | 0.1 M H2SO4 | –1.0 V to +1.0 V | 200 nm | Initial (within ~10 cycles) | 2018 [64] |

| Li-doped WO3 | ITO-Coated Glass | 53.1%/550 nm | 41.6 cm2/C/550 nm | 1 M LiClO4 in PC | −3.5 V to +3.5 V | 530 nm | Initial (within ~10 cycles) | 2019 [65] |

| WO3 | ITO-Coated Glass | 33.8%/550 nm | 72.6 cm2/C/550 nm | N/A | –1.0 V to +1.0 V | 200 nm | Initial (within ~10 cycles) | 2020 [66] |

| WO3 | FTO-Coated Glass | 79.0%/550 nm | 17.5 cm2/C/550 nm | 0.5 M H2SO4 | –0.7 V to +1.0 V | 400 nm | Initial (within ~10 cycles) | 2022 [67] |

In summary, since the evaporative deposition process needs to be carried out in a high-vacuum environment, the contamination of thin films by impurity molecules is greatly reduced. Therefore, the prepared WO3 thin films have high purity and excellent compactness. The WO3 thin films prepared by evaporative deposition are more conducive to improving the electrochromic properties of WO3 thin films under low-temperature deposition conditions, for example, according to the research results of Madhuri et al. in 2018 [64]. Evaporative deposition can also significantly optimize the electrochromic properties of WO3 thin films by combining doping elements and post-annealing processes.

4.1.3. Pulsed Laser Deposition

Pulsed laser deposition (PLD) is a technique that utilizes high-energy pulsed lasers as an external energy source to ablate source materials (or targets) [68,69]. The interaction between the laser and the target is brief yet intense, triggering target ablation through a series of complex processes. Theoretical and experimental studies of this phenomenon have remained a focus of academic interest and have given rise to new directions in laser applications. Among these, pulsed laser deposition technology was first demonstrated by Turner and Smith nearly three decades ago [70] and has since evolved into a widely recognized technique.

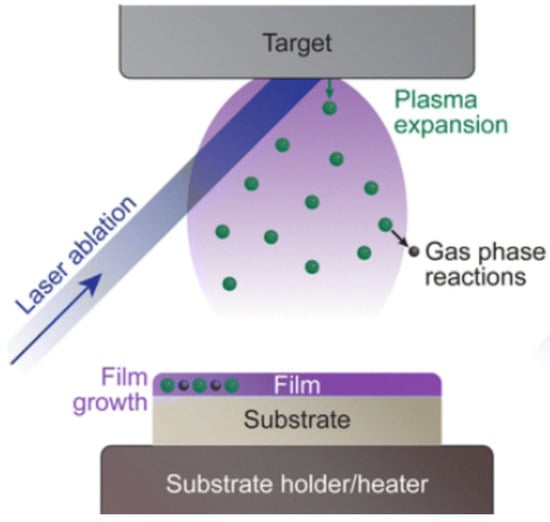

PLD is a technique that utilizes pulsed laser irradiation to vaporize/ablate a solid target, causing the material to leave the target surface in the form of vapor or plasma and deposit as a thin film on a substrate [71]. Its core lies in the laser–target interaction, which involves the conversion of energy from photons to electrons, and then into thermal and mechanical energy, ultimately leading to material vaporization, ablation, excitation, and plasma formation. However, the beam–solid interaction that leads to vaporization/ablation is an extremely complex physical phenomenon. The theoretical description of its mechanism is interdisciplinary, combining both equilibrium and non-equilibrium processes. When a laser beam irradiates the surface of a solid material, electromagnetic energy is first converted into electronic excitation energy and then into thermal, chemical, and even mechanical energy, thereby causing vaporization, ablation, excitation, and plasma formation. The vaporized material leaves the surface in a hydrodynamic flow, during which a large number of molecular collisions occur. Figure 9 [72] shows a schematic diagram of a PLD.

Figure 9.

Schematic cross-section of Morey autoclaves (adapted from [72], with permission).

Although PLD technology was introduced early and its principles were validated long ago, its development progressed slowly. This was primarily due to two reasons: firstly, the technology lacked unique application scenarios that could compete with more mature thin-film growth processes; secondly, there was a shortage of stable and cost-effective high-energy laser sources at the time. For nearly two decades, it remained a niche research tool. It was not until the successful preparation of high-quality superconducting YBa2Cu3O7−x thin films using PLD [73] that the technology experienced its first explosive breakthrough.

In 2019, BP Dhonge et al. [74] successfully fabricated nanocrystalline a-tungsten trioxide (a-WO3) thin films with different thicknesses on quartz substrates using the PLD technique. Their study revealed that the optical band gap of the a-WO3 thin films decreased with increasing film thickness, with the corresponding values being 3.47, 3.28, 3.08, and 3.06 eV, respectively. Additionally, the resistivity of the thin films increased as the thickness increased, while it decreased with the rise in temperature.

In 2021, Y Liu et al. [75] prepared WO3 thin films on ITO substrates using the PLD technique, with the laser power density adjusted in the range of 4.0–5.5 W/cm2 as a variable parameter. The analysis showed that when the laser power density decreased, the photoelectron peak positions corresponding to the W 4f orbital and O 1s orbital shifted slightly toward lower binding energy due to the difference in oxygen vacancy content. As the laser power density decreased, W6+ gradually replaced the positions of O2− in the lattice, leading to an increase in the number of oxygen vacancies in the lattice. At a wavelength of 830 nm, the transmittance modulation amplitude of the thin films reached 44.4% with a coloration efficiency of 58 cm2/C. These results demonstrate that the WO3 thin films prepared by the PLD technique possess excellent electrochromic properties. However, the study did not examine long-term cycling stability, and the narrow power density range (4.0–5.5 W/cm2) limits comprehensive evaluation for practical applications.

In 2025, S Tyagi et al. [76] prepared WO3 thin films on ITO substrates using the PLD technique. With the laser repetition frequency fixed at 10 Hz, different thin films were obtained by adjusting the number of laser pulses (2000, 4000, and 6000 pulses). The study showed that the thin film fabricated with 2000 laser pulses exhibited the optimal electrochromic performance, with an optical modulation amplitude of 14.39% and a coloration efficiency of 10.4 cm2/C. However, the film exhibits extremely low bleached-state transmittance (only 5.27%), and its coloration efficiency is much lower than that of other advanced studies, limiting its practical application in smart windows.

This section mainly introduces the research progress of preparing WO3 thin films by PLD, a physical fabrication method. We have compared and analyzed the electrochromic properties of WO3 thin films prepared via pulsed laser deposition, with specific details shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparison of Optical Modulation Amplitude and Coloration Efficiency of WO3 Thin Films Prepared by Pulsed Laser Deposition Under Different Conditions.

Table 4.

Comparison of Optical Modulation Amplitude and Coloration Efficiency of WO3 Thin Films Prepared by Pulsed Laser Deposition Under Different Conditions.

| Thin Film Type | Substrate | Optical Modulation Amplitude (ΔT%)/Wavelength | Coloration Efficiency (cm2/C)/Wavelength | Electrolyte | Potential Window | Thickness | Cycles | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WO3 | ITO-Coated Glass | 44.4%/830 nm | 58 cm2/C/830 nm | 2 wt% LiClO4 in PC | –2.5 V to +2.5 V | N/A | Initial (within ~10 cycles) | 2021 [75] |

| WO3 | ITO-Coated Glass | 14.39%/550 nm | 10.4 cm2/C/550 nm | N/A | −1.0 V to +1.0 V | 249 nm | Initial (within ~10 cycles) | 2025 [76] |

In summary, PLD can form WO3 thin films with a uniform structure using a relatively low number of pulses, thereby improving their electrochromic performance and stability. The thickness of the thin film affects its electrical and optical properties by regulating the crystal phase and band gap; thinner thin films are more suitable for electrochromic devices. A high power density is conducive to preparing WO3 thin films with fast response and high coloring efficiency, while a low power density enables the preparation of WO3 thin films with a higher optical modulation amplitude.

4.2. Research Progress on WO3 Thin Films Prepared by Chemical Methods

Chemical methods involve the use of metal salt precursors in solution that undergo chemical reactions (such as hydrolysis, polymerization, precipitation, etc.) to form solid thin films or nanostructures on substrate surfaces or within the liquid phase. The core principle lies in controlling reaction conditions (e.g., temperature, pH, concentration) to drive the reorganization and nucleation growth of ions or molecules at the atomic/molecular scale, ultimately yielding materials with specific composition, morphology, and functionality. This section focuses on discussing the research progress in preparing WO3 thin films using three chemical methods: hydrothermal method, sol–gel method, and electrodeposition method.

4.2.1. Hydrothermal Method

The term “hydrothermal” originates purely from the field of geology. Sir Roderick Murchison, a British geologist, was the first to use this term to describe the process in which water under high temperature and pressure acts on the Earth’s crust, thereby promoting the formation of various rocks and minerals. It is well-known that both the largest single crystals formed in nature and the large quantities of single crystals produced by humans in a single experimental run (such as quartz crystals weighing several kilograms) are formed through hydrothermal processes [77].

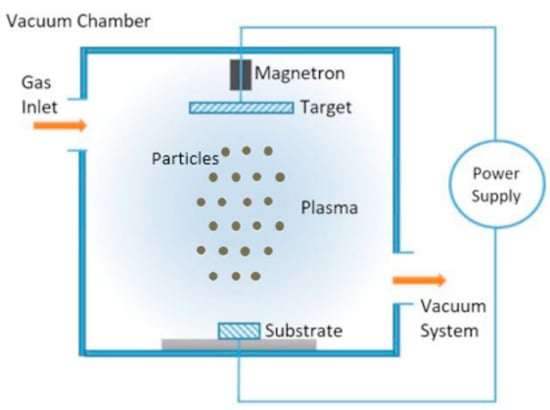

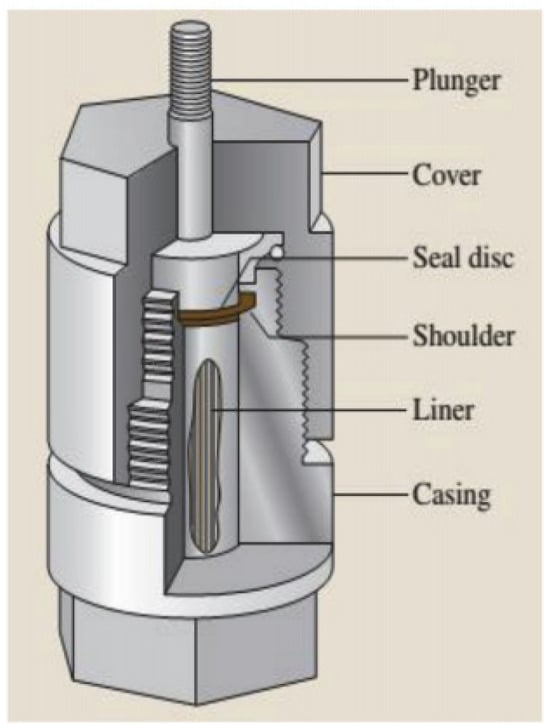

The essence of hydrothermal synthesis lies in regulating temperature (typically 100–1000 °C) and pressure (typically 1–100 MPa) to alter the physicochemical properties of water (or other solvents), thereby driving the dissolution of reactants, ion migration, and crystal growth. In 1914, the advent of Morey’s vessel further advanced the development of hydrothermal synthesis equipment. This vessel is an autoclave lined with a noble metal, which can be used across the entire pH range and adopts a flat plunger system to seal the reactants, as shown in Figure 10 [78]. Despite undergoing partial modifications, this design remains the fundamental structure of autoclaves used in hydrothermal synthesis today. However, in recent years (especially since the 1990s), hydrothermal technology has gained significant attention, attracting the research interest of scientists and technologists from various disciplines [79].

Figure 10.

Schematic cross-section of Morey autoclaves (adapted from [78], with permission).

In 2017, NY Bhosale et al. [80] prepared WO3 thin films on ITO substrates via a template-free hydrothermal method, where the etching process could assist WO3 in forming an adhesive thin film layer. Research results showed that compared with the WO3 thin film before etching, the etched WO3 thin film exhibited excellent electrochromic performance, with an optical modulation amplitude of 49.3% and a coloration efficiency (CE) of approximately 178.7 cm2/C. The etched WO3 thin film holds extremely high prospects for potential applications in energy-saving smart windows. However, the study did not evaluate the optical degradation under long-term cycling, and the etching process may compromise the conductivity and mechanical strength of the ITO substrate.

In 2020, A Khan et al. [52] deposited WO3 nanorods (NRs) on a conductive indium-doped tin oxide (ITO) glass substrate via a hydrothermal method, and subsequently coated a reduced graphene oxide (rGO) thin film on the surface of the WO3 thin film using an improved Hummers method. Studies showed that the WO3 nanorods maintain close contact with the rGO support, which is crucial for enhancing the electrochromic performance of the WO3/rGO composite. The WO3/rGO thin film exhibited a coloration efficiency of 181.5 cm2/C and an optical modulation amplitude of 58.8% at a wavelength of 633 nm, both of which are higher than the electrochromic performance of pure WO3 thin films. However, the response time of the composite film is slower than that of pure WO3 and rGO.

In 2022, Y Meng et al. [81] prepared WO3/PB inorganic–organic core–shell composite films via a hydrothermal method with controlled sintering temperature. Through comparative experiments, they explored the influence of the WO3/PB core–shell structure on the electrochromic properties of the films and its mechanism of action. The results showed that the lithium ion (Li+) diffusion coefficient of the WO3/PB composite film was 35% and 720% higher than that of the WO3 film and PB film, respectively, while its electrochromic response time was 22% and 76% shorter than that of the latter two films. The WO3/PB composite film exhibited superior electrochromic performance, which fully indicated that the rod-like core–shell structure in the composite film increased the contact area between the film and the electrolyte solution, thereby expanding the region involved in electrochemical reactions. Meanwhile, the electron pair donor–acceptor system formed by WO3 and PB enabled more electrons to participate in the reaction, further contributing to the film’s excellent electrochromic performance. The study did not clearly evaluate the device’s long-term cycling stability, and the composite film’s bleaching time remains relatively long, limiting its practical application.

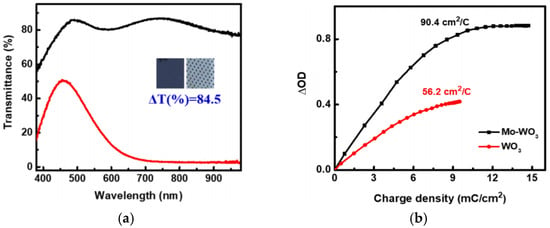

In 2024, HR Liu et al. [82] prepared molybdenum-doped tungsten trioxide (Mo-WO3) thin films via a one-step hydrothermal method. The research results showed that the 2 atomic percentage (2 at.%) Mo-WO3 thin film exhibited the optimal electrochromic performance, with an optical modulation amplitude of 61.7% and a coloration efficiency of 51.5 cm2/C. However, the study did not investigate optical modulation decay over long-term cycles.

In 2025, Jun Wu et al. [83] prepared WO3 nanorod thin films via a hydrothermal method and investigated the effects of precursor solution concentration (C1: 0.02 mol/L peroxytungstic acid solution, C2: 0.03 mol/L peroxytungstic acid solution, C3: 0.06 mol/L peroxytungstic acid solution) and annealing temperature (200, 300, 400 °C) on their electrochromic properties. The results showed that the annealing temperature had a minor effect, while the precursor solution concentration directly influenced the electrochromic properties of the WO3 thin films. With the increase in precursor solution concentration, the optical modulation of the WO3 thin films decreased gradually, reaching 51.1%, 43.8%, and 35.1%, respectively; in contrast, the coloration efficiency increased gradually but with a relatively small increment, attaining 41.8, 44.4, and 44.8 cm2/C, respectively. The prepared WO3 films exhibited poor cycling stability, with optical modulation decaying by over 65% after 150 cycles.

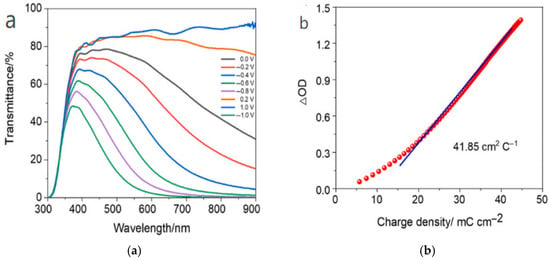

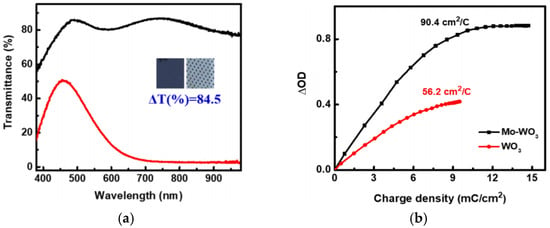

In 2025, Yi Wang et al. [84] developed a facile one-pot hydrothermal synthesis approach to fabricate hexagonal-phase WO3 microflower nanostructures. By optimizing the synthesis process—including self-seeding in the precursor solution and controlling the capping agent dosage—the morphology, crystalline structure, and electrochromic properties of the WO3 thin films were systematically enhanced. The as-prepared WO3 thin films demonstrated exceptional electrochromic performance, characterized by a high optical modulation amplitude of up to 86.8% at 610 nm and a high coloration efficiency of 41.85 cm2/C. However, the device exhibits a low areal capacitance and limited energy storage capability. The relevant data are shown in Figure 11 [84].

Figure 11.

(a) Transmittance spectra of WO3-CS0.15 film at different voltages; (b) Variation in the change in optical density (ΔOD) vs. charge density for WO3-CS0.15 film (adapted from [84], with permission).

This section mainly introduces the research progress of preparing WO3 thin films by the hydrothermal method, a chemical fabrication approach. The electrochromic properties of WO3 thin films prepared via the hydrothermal method have been compared and analyzed in this paper, with specific details shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Comparison of Optical Modulation Amplitude and Coloration Efficiency of WO3 Thin Films Prepared by Hydrothermal Method Under Different Conditions.

In summary, the hydrothermal method enables the growth of diverse nanostructures on substrates, thereby providing more channels for the rapid transport of ions and electrons. In terms of electrochromic performance, it significantly enhances the optical modulation amplitude and coloration efficiency. Additionally, the hydrothermal method facilitates the realization of element doping and the preparation of composite thin films, making it suitable for a variety of preparation requirements and scenarios.

4.2.2. Sol–Gel Method

As early as the mid-19th century, Ébelmann and Graham conducted research on silica gels, marking the beginning of scientific interest in the sol–gel preparation process for inorganic ceramic and glass materials. These early investigators discovered that the hydrolysis of tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS, chemical formula Si (OC2H5)4) under acidic conditions produced silica (SiO2) in the form of a “glassy substance”. By 1971, it had been established that any type of multicomponent oxide could be synthesized via the sol–gel process using alkoxides of different elements [85]. The resulting products could include glasses, glass-ceramics, or crystalline materials.

There are three main methods for preparing sol–gel monoliths [86]: Method 1: gelation of a solution of colloidal powders; Method 2: after hydrolysis and polycondensation reactions of alkoxide or nitrate precursors, hypercritical drying of the gel; Method 3: after hydrolysis and polycondensation reactions of alkoxide precursors, aging and drying under ambient atmospheres.

A sol is a dispersion of colloidal particles in a liquid. Colloids are solid particles with diameters ranging from 1 to 100 nanometers (nm). A gel is an interconnected rigid network with submicron-scale pores, where the average length of polymer chains exceeds 1 micrometer. The term “gel” encompasses various combinations of substances and can be classified into four categories [86]: (1) ordered lamellar structures; (2) completely disordered covalent polymer networks; (3) polymer networks formed through physical aggregation; (4) particular disordered structures.

The final material structure of the sol–gel process is highly dependent on reaction parameters, including pH, temperature, precursor concentration, and reaction time. For example, hydrolysis under acidic conditions typically forms linear polymer chains, resulting in gels with lower density, whereas alkaline conditions tend to produce highly branched colloidal particles, leading to denser structures. This ability to tailor the microstructure of materials through chemical pathways is one of the core advantages of the sol–gel method compared to other synthesis techniques.

It has also been known for a long time that the advantages of the sol–gel method mainly lie in higher purity, better homogeneity, and lower processing temperature. However, prior to this, little was known about the details of each step in the process. It is not until now that significant cognitive breakthroughs have been achieved in this field.

In 2017, P Jittiarporn et al. [87] deposited molybdenum trioxide-tungsten trioxide (MoO3-WO3) composite thin films on indium tin oxide (ITO) substrates via the sol–gel dip-coating technique and systematically investigated the effects of annealing temperature (200–500 °C) and MoO3 concentration (0–10%) on the properties of the thin films. The results showed that the 10% MoO3-90% WO3 composite thin film prepared by annealing at 200 °C exhibited excellent electrochromic performance, with an optical modulation amplitude of 48.27% and a coloration efficiency of 166.56 cm2/C. The film remained largely amorphous after annealing at 200 °C, its long-term cycling stability was not thoroughly investigated, and the high MoO3 content (10%) may slow the response time.

In 2018, C Ge et al. [88] prepared WO3 thin films via a facile sol–gel technique and investigated the influence of crystallization on the electron transport properties and electrochromic performance of the WO3 thin films. The study found that at a wavelength of 700 nm, the optical modulation amplitudes (∆T700) of the amorphous and crystalline WO3 were 44% and 27%, respectively. The coloration efficiencies of the amorphous and crystalline WO3 were 45.3 cm2/C and 27.4 cm2/C, respectively. Consequently, the electrochromic performance of the amorphous WO3 thin films was superior to that of the crystalline WO3 thin films. However, it should be noted that this conclusion is only based on charge injection at the same potential; at the same charge amount, crystalline WO3 has better ∆T700 (41%) and CE (45.0 cm2/C), and long-term cycling stability is not studied.

In 2019, BWC Au et al. [89] fabricated WO3 films on indium tin oxide (ITO)-coated glass via the sol–gel spin-coating method, and elucidated the effect of film thickness on their electrochromic properties. The thickness of the prepared WO3 films ranged from 41 nm to 750 nm. Experiments showed that at a wavelength of 338 nm, the film exhibited a maximum coloration efficiency of 34.8 cm2/C and an optical modulation amplitude of 40%. However, the study noted that for thicknesses exceeding 338 nm, coloration efficiency decreased due to reduced optical modulation, and thicker films developed cracks, compromising electrochromic stability.

In 2021, KK Purushothaman et al. [90] prepared WO3 thin films via the sol–gel dip coating method and systematically investigated their optical, structural, morphological, electrochemical, and electrochromic properties. The results showed that the WO3 thin films exhibited an optical modulation amplitude change of 55.37% at a wavelength of 550 nm, demonstrating excellent electrochromic performance. However, the study only explored a single film thickness (260 nm), lacking a systematic investigation into the effect of thickness variation on electrochromic performance, which limits its optimization potential.

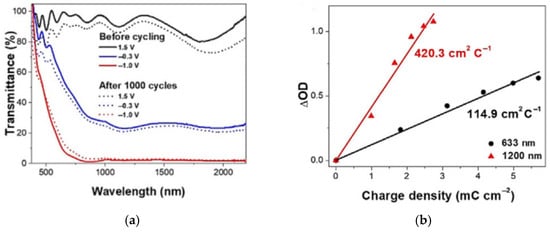

In 2023, Qiancheng Meng et al. [91] proposed a facile and efficient sol–gel strategy to fabricate porous Ti-doped WO3 thin films by introducing a foaming agent, aiming to realize the development of high-performance dual-band electrochromic smart windows (DESWs). Experimental results showed that the optimized thin films exhibited excellent dual-band electrochromic properties, including high optical modulation amplitudes (73.9% at a wavelength of 633 nm and 86.8% at 1200 nm) and high coloration efficiencies (114.9 cm2/C at 633 nm and 420.3 cm2/C at 1200 nm). However, the device did not utilize an ion storage layer, which may impact its energy consumption and integration convenience in practical applications. The relevant data are shown in Figure 12 [91].

Figure 12.

(a) Optical transmittance spectra of the WO3 thin film at 1.5 V, −0.3 V, and −1.0 V before and after 1000 cycles; (b) Coloration efficiency at 633 nm and 1200 nm (adapted from [91], with permission).

In 2024, Zheng, Jin et al. [92] fabricated amorphous WO3 thin films co-doped with graphene oxide (GO) and bismuth (Bi) via the sol–gel spin-coating method. The study showed that under the regulatory effect of GO, the GBW-2 thin film—prepared by adding 200 μL of GO dispersion to 10 mL of precursor solution—exhibited excellent electrochromic properties: it achieved an optical modulation amplitude of 85% and a coloration efficiency of 65.9 cm2/C at a wavelength of 630 nm, along with good cycling stability—after 10,200 cycles, the transmittance modulation amplitude only suffered a loss of 13.6%. However, the study did not investigate the effect of GO doping on the film’s mechanical properties and long-term environmental stability.

This section mainly introduces the research progress of the sol–gel method, a chemical fabrication approach in the field of WO3 thin film preparation. In this paper, the electrochromic properties of WO3 thin films prepared by the sol–gel method are compared and analyzed, with specific details shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Comparison of Optical Modulation Amplitude and Coloration Efficiency of WO3 Thin Films Prepared by Sol–Gel Method Under Different Conditions.

In summary, in terms of flexible microstructure design, the sol–gel method enables the fabrication of high-performance, multifunctional WO3 electrochromic thin films through crystal phase regulation and porous structure engineering. For example, research by C Ge et al. in 2018 [88] clearly demonstrated that amorphous WO3 thin films exhibit superior electrochromic performance compared to crystalline WO3 thin films. In 2023, Qiancheng Meng et al. [91] introduced a foaming agent to prepare porous Ti-doped WO3 thin films, which significantly increased the contact area between the electrolyte and the film, thereby achieving ultra-high optical modulation amplitude and ultra-high coloration efficiency. In terms of chemical composition, the sol–gel method facilitates the preparation of WO3 thin films with high coloration efficiency and high cycling stability by incorporating ion doping and multi-component composite structures. For instance, in 2017, P Jittiarporn et al. [87] prepared MoO3-WO3 composite thin films, achieving a high coloration efficiency of 166.56 cm2/C. In 2024, Zheng, Jin et al. [92] developed GO-Bi-WO3 composite structured thin films that not only exhibit high optical modulation amplitude but also possess excellent cycling stability.

4.2.3. Electrodeposition Method

The electrodeposition method is a preparation technology featuring simple equipment, low cost, easy control of the deposition process, and scalable production. Having evolved from theoretical exploration in the 19th century, it has now become a core preparation technology across multiple fields, with its core competitiveness lying in the flexibility of electrochemical regulation and the low-cost advantage in industrialization.

The essence of electrodeposition is the cathodic reduction reaction in an electrolytic cell, which enables the reduction and deposition of metal ions or ion clusters in the solution to form solid thin films, coatings, or powder materials through redox reactions occurring on the electrode surface. It has been widely applied in fields such as metal processing, electronic information, new energy, and biomedical engineering. In the future, with the improvement of green processes, the breakthrough in nanostructure regulation technology, and the in-depth integration with emerging fields (such as flexible electronics and new energy), the electrodeposition method will continue to play an irreplaceable role in the field of low-cost preparation of high-performance materials and become one of the key technologies supporting high-end manufacturing and sustainable development.

In the specific technology of electrodeposition coating, a branch of the electrodeposition method, the process can be further divided into anodic electrodeposition and cathodic electrodeposition based on the charge of the film-forming substances. Anodic electrodeposition uses polyelectrolytes containing carboxyl groups, which form ammonium or amine salts in water. At the anode, water electrolysis produces H+, lowering the local pH and causing the polyelectrolyte to deposit in the form of a polyacid. Cathodic electrodeposition uses polyelectrolytes containing amino groups, neutralized with acid to form salts. At the cathode, water electrolysis produces OH−, raising the local pH and causing the polyelectrolyte to deposit as free amine [93].

In 2017, S Poongodi et al. [94] synthesized vertically oriented WO3 nanoflake array films at room temperature via a template-free and facile electrodeposition method. This WO3 nanoflake array was used as an efficient cathode material in the structure of electrochemical devices and exhibited excellent electrochromic performance. Research results showed that the WO3 thin films achieved an optical modulation amplitude of 68.89% at a wavelength of 550 nm and a coloration efficiency of approximately 154.93 cm2/C. Moreover, it maintained no performance degradation even after 2000 cycles, demonstrating broad prospects in potential multifunctional application fields such as smart windows, gas sensors, and optical sensors. However, the electrolyte used for electrochromic measurements was not clearly specified, and the gas sensing required high operating temperatures, limiting its practical application scenarios.

In 2018, Z Xie et al. [95] prepared WO3 thin films with a two-dimensional (2D) grid structure via electrodeposition. The surface of the WO3 thin films formed grooves due to the removal of polystyrene (PS) nanofibers, thereby presenting a grid-like structure. The research results showed that at a wavelength of 550 nm, the optical modulation amplitude of the grid-structured WO3 thin films was 77%, while that of the planar WO3 thin films was 36%. The coloration efficiency (CE) of the grid-structured WO3 thin films reached 71.8 cm2/C, which was higher than that of the planar WO3 thin films (58.8 cm2/C). The grid-structured WO3 thin films prepared in this study show potential application value in the construction of high-performance and fast-responsive electrochromic devices. However, the fabrication of the grid structure relied on a PS nanofiber template, making the process relatively complex and potentially hindering its feasibility and cost-effectiveness for large-scale production.

In 2019, Y Song et al. [96] prepared a novel Ti-doped hierarchically mesoporous silica microsphere/tungsten trioxide (THMS/WO3) hybrid film by simultaneously electrodepositing Ti-doped hierarchically mesoporous silica microspheres (THMSs) and WO3 nanocrystals onto a fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO)-coated glass substrate. The research showed that the hybrid film achieved an optical modulation amplitude of 52.00% and a coloration efficiency of 88.84 cm2/C at a wavelength of 700 nm. The incorporation of THMSs into the film can significantly improve the electrochromic performance of the hybrid film, and the content of THMSs plays a key regulatory role in the electrochromic performance of the hybrid film. However, the verification of long-term durability for practical applications is insufficient, and the switching time is relatively long.

In 2020, YT Park et al. [97] successfully prepared silver nanowire (AgNW)-embedded WO3 electrochromic thin films on fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO)-coated glass via an electrodeposition method. The research showed that the composite thin films had a rough surface and exhibited excellent redox reaction kinetics: their coloration efficiency reached 45.3 cm2/C, and the optical modulation amplitude was 62.52%. Based on the significant improvement in electrochromic performance, the AgNW-embedded WO3 composite-structured thin films are expected to be ideal candidate materials for fabricating high-performance electrochromic devices. However, the composite film’s transmittance modulation (62.52%) is lower than that of single-layer WO3 (76.03%).

In 2021, M Arslan et al. [98] directly grew vertically aligned aluminum-doped WO3 (Al:WO3) nanoplate arrays on ITO glass via a facile electrodeposition method, followed by annealing at 450 °C for 2 h in an argon atmosphere. They investigated the effect of aluminum (Al) doping on the electrochromic properties of WO3 films. The results showed that the direct band gap energies of pure WO3 and Al:WO3 films were 3.62 eV and 3.34 eV, respectively. Compared with pure WO3 films, the Al:WO3 films exhibited more excellent electrochromic performance at a wavelength of 632.8 nm, with an optical modulation amplitude of 55.9% and a coloration efficiency of 148.1 cm2/C. This work not only provides a highly promising electrode material for electrochromic display applications but also offers an economical and effective strategy for the preparation of other doped metal oxide films. However, the study did not evaluate the long-term cycling stability of Al:WO3 films under harsh conditions, nor did it systematically compare Al doping with other common dopants.

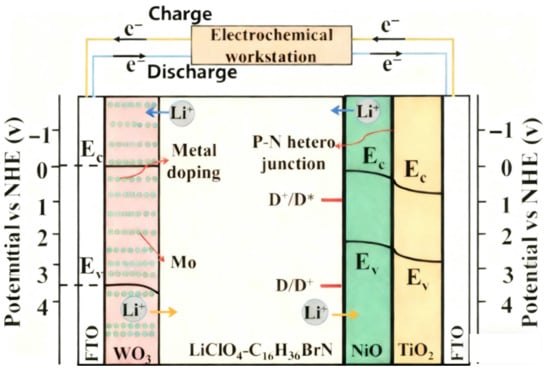

In 2024, AK Prasad et al. [99] prepared Mo-WO3 films by the electrochemical co-deposition method with Mo doping. The thin films were designed as multifunctional materials with both electrochromic (EC) and energy storage (ESD) functions. The optical modulation amplitude of the Mo-WO3 thin films is 84.5% and the coloration efficiency is 90.4 cm2/C. However, the integrated device showed significantly reduced optical modulation and slower response under solar power compared to external power.The relevant data are shown in Figure 13 [99].

Figure 13.

(a) Optical modulation measurement of colored and bleached states of optimized Mo–WO3 thin films; (b) Coloration efficiency curves for Mo-WO3 thin film (adapted from [99], with permission).

This section mainly introduces the research progress of the electrodeposition method, a chemical fabrication approach, in the field of WO3 thin film preparation. In this paper, the electrochromic properties of WO3 thin films prepared by the electrodeposition method are compared and analyzed, with specific details shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Comparison of Optical Modulation Amplitude and Coloration Efficiency of WO3 Thin Films Prepared by Electrodeposition Method Under Different Conditions.

In general, the electrodeposition method significantly enhances the electrochromic properties of WO3 thin films by precisely regulating their microtopography and chemical composition. Studies have shown that by constructing vertically oriented nanosheet arrays, two-dimensional (2D) grid structures, or incorporating composite materials such as mesoporous microspheres and silver nanowires, the electrodeposition method can greatly increase the specific surface area and ion diffusion channels of the thin films. This structural advantage is directly translated into outstanding performance: the optical modulation amplitude (ΔT%) can reach up to 84.5%, while the coloration efficiency (CE) is particularly excellent, with a maximum value of approximately 154.93 cm2/C. In the future, the electrodeposition method can achieve precise control of deposition parameters by introducing sensors and feedback control systems, thereby improving the uniformity of large-area thin films. It is also feasible to explore co-deposition with emerging 2D materials (such as graphene and MXene) or more functional nanostructures to develop intelligent thin films integrating multiple functions, including electrochromism, energy storage, and self-healing. Going forward, the electrodeposition method is expected to become one of the most competitive technical routes for preparing high-performance, low-cost, and flexible electrochromic devices.

4.3. WO3-Based Electrochromic Devices

Although the electrochromic performance of the WO3 film itself is of crucial importance, its performance in practical devices strongly depends on the complete device stack structure. A typical electrochromic device usually adopts a “sandwich” structure, consisting of an electrochromic layer, an ion storage layer (counter electrode), an ion conductor (electrolyte), and transparent conductive layers on both sides. The selection and matching of these components directly determine the comprehensive performance of the device.

4.3.1. Device Structure

- •

- Electrochromic layer

The WO3 films reviewed in this paper play this role, achieving coloration and bleaching by virtue of the intercalation/extraction of ions and electrons.

- •

- Counter Electrode

This layer works in synergy with the WO3 layer: it provides an equivalent amount of ions (e.g., Li+) during the coloration of WO3, and stores these ions during the bleaching of WO3, so as to maintain the charge balance of the entire device. Commonly used counter electrode materials include:

- NiO

During the coloration of WO3 (with Li+ intercalated into NiO), the NiO layer bleaches itself, forming complementary coloration, which enhances the overall optical modulation range of the device.

- 2.

- Prussian Blue (PB

It has an open framework structure and high ionic conductivity, and can achieve fast and efficient synergistic color change with WO3.

- 3.

- V2O5

It has high ionic storage capacity and electrochemical stability, so it is often used as an ion storage layer, but its electrochromic contrast is relatively low.

- 4.

- Conductive polymers

They possess high electrical conductivity and rich color changes, and can be used to fabricate flexible devices, but their long-term cycling stability is generally inferior to that of inorganic materials.

- •

- Electrolyte

As the medium for ion transport, its selection (liquid, gel, or solid state) directly affects the device’s response speed, cycle life, and safety. Liquid electrolytes possess high ionic conductivity but carry the risk of encapsulation leakage; gel/solid electrolytes exhibit good mechanical stability, making them more suitable for flexible devices, yet they have relatively high ion migration resistance.

- •

- Transparent conductive substrate

Like ITO or FTO glass, their sheet resistance and transmittance will affect the energy consumption of the device and the overall transmittance.

Taking the high-performance electrochromic energy storage device recently reported by Liu et al. [82] as an example, FTO glass was used as the substrate and electrode (transparent conductive layer) on both sides; a Mo-WO3 thin film was used as the device’s cathode (electrochromic layer); a TiO2/NiO/N719 composite film was used as the device’s anode (counter electrode); and the system composed of C16H36BrN and LiClO4 dissolved in propylene carbonate was used as the electrolyte. As shown in Figure 14 [82].

Figure 14.

The structure of the Mo-WO3@TiO2/NiO/N719 Device (adapted from [82], with permission).

4.3.2. The Interaction Between the Morphology of WO3 Thin Film and Device Structure

The morphologies of WO3 thin films obtained via different preparation methods directly determine their interfacial interactions with other components in the device and the final device performance. This paper summarizes the mutual influences between the morphologies of WO3 thin films (prepared by physical methods and chemical methods) and the device, as shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Comparison of WO3 Thin Films Prepared by Physical and Chemical Methods for Device Integration.

Table 8.

Comparison of WO3 Thin Films Prepared by Physical and Chemical Methods for Device Integration.

| Aspect | Physically Prepared Films (Dense) | Chemically Prepared Films (Porous/Nanostructured) |

|---|---|---|

| Morphological | Dense, Uniform, Smooth | Porous, High Specific Surface Area, Nanostructured |

| Adhesion to Substrate | Strong | Relatively Weaker |

| Interface with Electrolyte | Facilitates good contact with dense solid-state electrolytes (e.g., Ta2O5, LiNbO3); suitable for constructing all-solid-state devices. | Forms an interpenetrating interface with gel or liquid electrolytes, offering a large contact area. |

| Ion Transport Path | Limited, primarily interfacial diffusion; slower ion kinetics. | Bulk diffusion; provides abundant channels for fast ion transport. |

| Key Advantage | Suitable for fabricating high-performance, long-lifetime all-solid-state devices. | Capable of achieving high coloration efficiency and fast response. |

| Primary Challenge | The dense structure restricts bulk ion diffusion, often requiring a thinner counter electrode layer for matching kinetics. | Excessive porosity can compromise film compactness and cycling stability. |

| Strategy | Requires interface optimization with solid-state electrolytes and selection of stable counter electrodes (e.g., NiO). | Hydrothermally grown WO3 nanorod arrays can form a core–shell structure with a Prussian blue counter electrode, leveraging synergistic effects and the large contact area for fast response. |