Abstract

Background: Milk is a highly nutritious food, but its composition makes it an ideal medium for microbial growth, particularly for bacteria like Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus). In Ecuador, raw milk consumption is culturally rooted, and contamination risks are heightened, especially in informal markets. Staphylococcus aureus, a Gram-positive, coagulase-positive bacterium, commonly colonizes mucous membranes and can cause a range of infections due to its production of thermostable toxins. Its impact extends to bovine mastitis, severely affecting dairy production. Of particular concern is the emergence of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strains, associated with the acquisition of the mecA gene located on the “staphylococcal chromosomal cassette mec” (SCCmec) element and identification of a mecA homologue, mecC, further complicates detection and monitoring efforts. Objectives: This study evaluated the prevalence of S. aureus and MRSA strains in raw milk from Ecuadorian provinces Pichincha and Manabí. Methods: A total of 633 samples were collected and analyzed via real-time PCR (qPCR) and bacterial isolation methods, complemented by endpoint PCR assays for mecA and mecC genes detection. Results: A high prevalence of S. aureus (84%) was observed, with significant differences between regions. MRSA was detected in 23% of all samples, with mecA being more prevalent than mecC among isolates. Sequencing of 16S rDNA confirmed the identity of isolates, while phylogenetic analysis of mecA and mecC genes validated their presence. The findings suggest that suboptimal hygiene practices and varied biosecurity protocols, especially among small and medium dairy producers, may contribute to the persistence of resistant strains. Conclusions: This study highlights the presence of S. aureus and MRSA in raw milk, underscoring the need for strengthened surveillance, improved hygiene practices, the use of molecular diagnostic tools, and proper heat treatments to reduce the public health risks associated with contaminated milk and its derivatives.

1. Introduction

Milk is a highly nutritious food, which, due to its composition rich in minerals, vitamins, proteins and fats, serves as an essential food component for those sectors of the population with little access to other resources [1]. In Ecuador, the consumption of raw milk is deeply entrenched in the cultural fabric, particularly within rural communities where informal trade networks play a significant role, where at least 2.6 million liters of milk are consumed per year [2]. Due to its content, raw milk is an ideal medium for the growth of microorganisms such as bacteria, fungi and yeasts, where bacteria are the most common due to their high growth rate [3]. Among the most commonly found pathogenic bacteria in raw milk, Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) stands out due to the possible pathogenic effects on animals and humans caused by its virulence factors [4].

S. aureus is a spherical, Gram-positive, coagulase-positive bacterium belonging to the genus Staphylococcus, and is part of the microbiota of the mucous membranes, including healthy noses and viscera, of many animals [4,5]. Due to its ability to produce thermostable toxins, it can cause a wide variety of skin infections or more serious infections such as pneumonia, sepsis, endocarditis and toxic shock syndrome [6,7,8]. In cattle, S. aureus is one of the main causes of mastitis, both clinical and subclinical, being a problem for milk production, since it can cause permanent damage to mammary tissue [5,9]. When transmitted to humans, S. aureus can cause a wide range of infections, especially in moments of low immune response, where the high variety of toxins and its increasing resistance to antibiotics, especially methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains, represent a high risk to public health [10,11].

The development of methicillin resistance is due to the acquisition of the mecA gene, which is located in the mobile genetic element called the “staphylococcal chromosomal cassette mec” (SCCmec) [12]. The mecA gene encodes penicillin-binding protein 2a (PBP2a), an enzyme involved in the synthesis of cell wall peptidoglycan, which has a low affinity for β-lactams, ensuring cell wall integrity in these strains in the presence of these antibiotics [13,14]. In 2011 in the UK, a variant of mecA with 70% nucleotide similarity was identified in cattle samples, subsequently named mecC [15]. While mecA is mostly found in human and domestic animal isolates, mecC is more common in wild animal and bovine isolates, although it has a lower global distribution than mecA [13]. The difference between these two genes showed that most assays designed for mecA are not able to detect mecC so differential identification of these two genes is necessary [15,16].

The prevalence of MRSA strains in food, particularly in raw milk and dairy products has been documented worldwide with varying prevalences according to region [17]. In Algeria, a 2021 study reported a 23% prevalence of MRSA strains in dairy products, along with the detection of other enterotoxin genes [18]. In Italy, in 2015, 20% of S. aureus isolates from raw milk were found to be MRSA [19]. In the United States in 2021, a multi-regional study of 189 farms found that 62.4% had S. aureus but only 0.8% were MRSA [20]. In Brazil in 2016, 23.3% of S. aureus strains isolated from cattle corresponded to MRSA [21]. Finally, in Colombia, a country bordering Ecuador, a prevalence of up to 47% has been reported; in addition to being elevated, it was identified that 27% of the strains contained the mecA gene [22]. Although S. aureus is usually found in milk in at least 68.8% of investigations, for the most part the presence of MRSA is usually less than 5% and increases in this rate are related to poor husbandry practices [17]. However, there is limited information regarding the presence of mecA- and mecC-carrying strains in raw milk in Ecuador, and studies addressing mecC in South America are particularly scarce [15,23]. Considering that raw milk consumption is still common in rural and peri-urban areas, detecting these resistance determinants is relevant for both antimicrobial resistance (AMR) surveillance and dairy safety [24,25]. Therefore, identifying the occurrence of mecA and mecC in raw milk contributes to filling a regional knowledge gap and provides evidence that may support improvements in milk hygiene practices and public health monitoring frameworks under a One Health approach [17,23].

The use of molecular techniques for the identification of contaminants is presented as an effective way, with high sensitivity and specificity for the detection of contaminants in food as well as factors that position them as risk agents for public health [26,27,28]. The aim of this study is to ascertain the prevalence of S. aureus in raw bovine milk from two provinces of Ecuador (Pichincha and Manabí). The study will also detect the mecA and mecC genes associated with MRSA strains, and validate a qPCR assay for their molecular identification.

2. Results

2.1. Standard Curve and Sensitivity

The dilution run in base 10 resulted in a standard curve with 98.15% efficiency and a correlation coefficient of 0.998 (Supplementary Materials). Furthermore, a limit of detection (LoD) and limit of quantification (LoQ) of up to 1 copy of genetic material was determined.

2.2. Prevalence and Distribution of S. aureus in Raw Milk Samples

Based on qPCR results from pre-enriched milk samples, 531 of 633 samples were positive for S. aureus (84.0%) (Table 1). When comparing provinces, Pichincha accounted for 303 positive samples out of 322 analyzed (94.1%), representing 57.0% (303/531) of all positive detections. In contrast, Manabí presented 228 positive samples out of 311 (73.3%), and the difference in prevalence between provinces was statistically significant (p < 0.0001). When evaluating producer scale, small-scale producers showed 203 positive samples out of 266 (76.3%), corresponding to 38.2% (203/531) of all positives. Medium-scale producers had 187 positives out of 232 samples (80.6%), and large-scale producers had 141 positives out of 135 samples analyzed (65.6%), without statistically significant differences among these groups (p > 0.05). Considering both geographic origin and production scale, small-scale producers in Pichincha had the highest number of positive samples (119/127; 93.7%), although this value did not differ significantly from medium and large producers within the same province (p > 0.05).

Table 1.

Comparison between S. aureus detection by qPCR in pre-enriched milk and successful bacterial isolation from positive samples. Percentages of qPCR positivity are calculated based on the total samples analyzed in each province (Pichincha: n = 322; Manabí: n = 311). Percentages of isolation refer to the proportion of qPCR-positive samples from which S. aureus was successfully recovered. Statistically significant differences are indicated by *.

2.3. Isolation of Staphylococcus aureus and MRSA Strains Identification

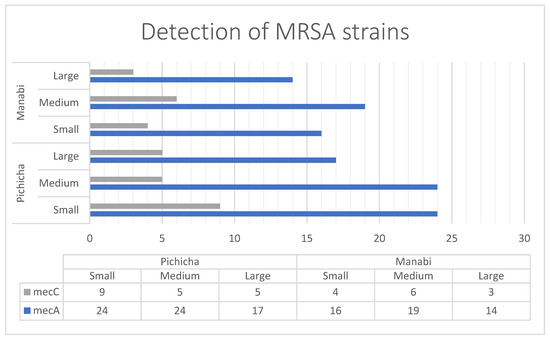

From the samples that tested positive for S. aureus by qPCR, the bacterium was successfully isolated in 89.83% of cases (Table 1), confirming a strong agreement between molecular detection and culture. The concordance between both methods was supported by a Cohen’s kappa coefficient of 0.74, indicating substantial agreement. Among the isolates, 146 out of 476 tested (30.61%) carried either mecA or mecC, corresponding to an overall MRSA prevalence of 23% across all raw milk samples analyzed. The mecA gene was more frequently detected (114 isolates) compared to mecC (32 isolates). The distribution of MRSA reflected the same regional pattern observed for S. aureus: in Pichincha, small-scale producers showed the highest number of mecA and mecC positive isolates, while in Manabí, the highest frequency of methicillin-resistant isolates occurred among medium-scale producers, despite small producers in Manabí having a greater number of S. aureus-positive samples overall (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Detection and distribution of mecA and mecC positives strains of S. aureus based on locality and producer size.

2.4. 16S Sequences Analysis

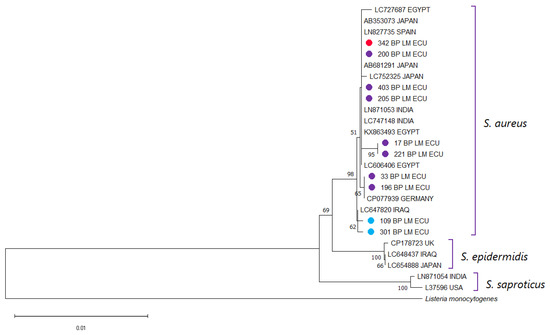

The 16S rDNA sequences obtained from the selected isolates showed >99% nucleotide identity with S. aureus reference sequences deposited in GenBank, confirming the taxonomic identity of the isolates. The phylogenetic tree constructed using these sequences and representative Staphylococcus spp. from GenBank grouped the isolates within the expected S. aureus clade, with clear separation from other species of the genus (Figure 2). As expected for a highly conserved gene such as 16S rDNA, no distinct subclustering patterns were observed among isolates carrying mecA or mecC compared to those lacking these genes. This result is consistent with the known limited ability of the 16S locus to resolve strain-level or gene-associated variation within S. aureus. Therefore, the 16S analysis served specifically to confirm species identity rather than to infer evolutionary relationships among isolates.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis was performed using the partial 16S rDNA sequences of the S. aureus isolates from this study together with reference sequences retrieved from NCBI. Multiple sequence alignment was carried out with Clustal X v2.0, and a phylogenetic tree was generated in MEGA 11. Bootstrap support values (1000 replicates) are indicated at the nodes, and the scale bar denotes the number of substitutions per nucleotide site. A 16S sequence of Listeria monocytogenes was used as an outgroup. Sequences obtained in the present work are labeled with ● for clear identification. Isolates harboring mecA are displayed in red, those positive for mecC in blue, and non-MRSA strains in purple.

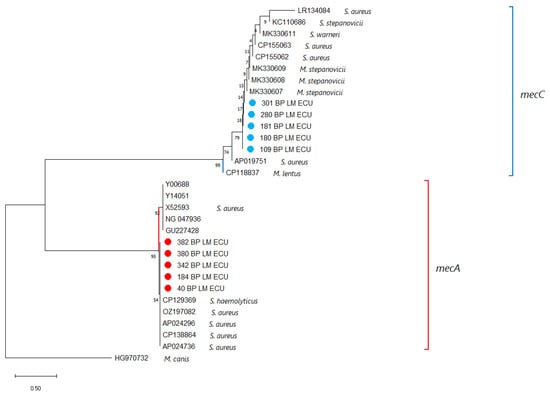

2.5. mecA and mecC Sequences Analysis

The mecA and mecC amplicons obtained from the isolates were sequenced and compared with reference sequences available in GenBank. Both genes showed 100% nucleotide identity with previously reported sequences, confirming that the resistance determinants detected in the isolates correspond to the known variants of mecA and mecC associated with methicillin resistance in S. aureus (Supplementary Materials). As the sequenced regions are highly conserved, no phylogenetic subdivision or variant differentiation was observed, and the sequencing results served to validate the presence of the resistance genes rather than to infer evolutionary relationships (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

A phylogenetic tree was generated using partial nucleotide sequences of the mecA and mecC genes from this study together with homologous sequences retrieved from NCBI. Sequence alignment was performed with Clustal X v2.0, and tree reconstruction was conducted in MEGA X. Bootstrap support values, calculated from 1000 replicates, are indicated at the nodes, and the scale bar shows the number of substitutions per site. A mecB sequence from Mammaliicoccus canis served as the outgroup. Sequences obtained here are marked with ●, with mecA-positive isolates displayed in red and mecC-positive isolates in blue.

3. Discussion

Due to its high nutritional content, several pathogenic microorganisms tend to proliferate in raw milk, which presents a risk to public health in those population niches where it is commonly consumed [29]. Among them, S. aureus is presented as a risk agent with a high contamination rate in bovine-related environments, including the udder of cows and thus the milk produced [30]. Molecular methods such as qPCR are presented as a viable way for rapid, high sensitivity and specificity molecular detection of these pathogens [31]. The identification of methicillin resistance genes mecA and mecC in S. aureus strains is essential to determine the risk of this pathogen as a contaminant, given the symptomatology it can cause in both cattle and humans consuming contaminated milk [32]. The importance of using specific methods for the detection of the mecC gene differentiated from the mecA gene arises from the fact that those designed for the latter do not tend to have the capacity to detect all variants [33]. This study was able to identify both the presence of S. aureus as a contaminant agent in raw milk by qPCR and the presence of the mecA gene and the mecC gene in different isolates. These findings suggest that the contamination detected is not only widespread, but may be associated with milking hygiene practices, equipment sanitation, or herd-level mastitis dynamics rather than sporadic contamination events [34]. Furthermore, the detection of both mecA and mecC indicates the simultaneous circulation of multiple resistance determinants, which has direct implications for antimicrobial stewardship and public health, particularly in settings where raw milk consumption is common [35]. From a One Health perspective, the concurrent detection of S. aureus and methicillin-resistance determinants in raw milk links animal health, on-farm practices, food safety, and community exposure, underscoring that effective mitigation requires coordinated actions across veterinary, dairy-processing, and public-health stakeholders rather than isolated, sector-specific interventions [35,36].

Of the 633 samples tested, the present study found the presence of S. aureus in 531 (84%), being an alarmingly high prevalence, it is a wake-up call to determine the source of the high contamination rates. The results of this study are consistent with data from a study in Italy in 2020, where 80% of milk samples showed the presence of S. aureus and were associated with contamination in storage tanks and milking equipment [37]. Similarly in China in 2021 a 58.1% prevalence of S. aureus was found in raw milk samples, where contamination was associated with unhygienic handling by farmers during milking [38]. However, the trend obtained in this work contrasts with the majority of studies where the prevalence of S. aureus tends to be less than 50%, indicating that the high rates in this study are a consequence of deficiencies in sanitation standards [39]. This highlights the importance of evaluating farm-level milking routines, cleaning protocols, and equipment maintenance as potential drivers of bacterial persistence in the production chain. The confirmation of the bacterial strains resulted in a correspondence of the 16S sequences obtained in this study with those previously deposited in the GenBANK close to 100% (Supplementary Material). Although bacterial isolation, even without the use of sequencing, can result in the detection of specific bacteria such as S. aureus, this method is more time consuming than molecular methods and can lead to a higher risk of failure due to external factors [40]. On the other hand, the isolation data shows an interesting value, where in the samples from small and medium producers at least 90% of the positives were isolated, while in the large producers this value was below 80% (Table 1). This may be due to the fact that large producers have greater control and biosecurity measures, implying that in some cases the contamination remains at low percentages of bacterial load, making isolation more difficult [41]. The isolation protocol can be made more efficient by varying the culture media used [42]. Baird-Parker agar, employed in this study, is the most suitable medium for isolating S. aureus in milk due to its high specificity [43]. However, using less selective media such as Mannitol Salt Agar in parallel can enhance recovery efficiency, although it increases the risk of false positives, which require careful interpretation [44]. Additionally, the use of a qPCR-based molecular method capable of detecting as few as one copy of genetic material, as implemented in this study, reduces the likelihood of false negatives [45]. Comparable surveys in other South American dairy systems report similar challenges regarding S. aureus contamination, although with variability linked to milking hygiene and equipment sanitation. For example, studies in Argentina and Peru have shown that herd management and milking routines heavily influence the bacterial load and strain diversity of S. aureus in raw milk, emphasizing the role of farm-level practices in driving contamination dynamics [46,47]. In practical terms, these findings support incremental policy measures within Ecuador’s dairy chain—such as routine screening of bulk-tank milk for S. aureus/MRSA at processing collection points, strengthened hygiene standard operating procedures during milking and tank sanitation, and targeted training for small and medium producers—while reinforcing existing recommendations on heat treatment for products entering formal markets [48].

MRSA among S. aureus isolates was particularly high (54.07%), corresponding to an overall MRSA prevalence of 23% in raw milk samples. This prevalence exceeds that reported in other studies in South America, where MRSA rates have been below 2% in dairy, indicating a potential regional problem [17]. In terms of resistance genes, mecA was found more frequently than mecC, in line with global epidemiological trends, where mecA remains the predominant determinant of methicillin resistance in cattle-associated S. aureus [17,49]. However, the detection of mecC in a significant proportion of isolates (32/146) is noteworthy, as mecC has been increasingly identified in S. aureus isolates of animal origin in Europe and, to a lesser extent, in South America [50,51]. This finding raises concerns about the potential for zoonotic transmission and the emergence of poorly characterized resistance mechanisms in the region. The differences observed between scales of production, with smallholders in Pichincha and medium-sized producers in Manabí harboring a higher number of mecA and mecC positive isolates, suggest that biosecurity practices and antimicrobial use policies may vary significantly depending on farm size. Previous research has shown that small farms tend to have less stringent hygiene and antibiotic stewardship practices, which may contribute to the selection and maintenance of resistant bacterial populations [52]. In contrast, medium-sized farms may experience different selection pressures due to more intensive husbandry practices and prophylactic antibiotic use, which may explain the relatively high prevalence of MRSA despite lower detection rates of S. aureus [53]. These findings highlight the importance of implementing training and quality control programs adapted to the size and characteristics of dairy farms [54]. This issue is particularly critical in Ecuador, where the informal consumption of milk and dairy products—those not subjected to standardized quality and safety testing—represents a significant public health concern. These products often bypass adequate heat treatment necessary to eliminate pathogenic microorganisms, and they frequently contain elevated levels of antibiotic residues [24,55]. At a broader scale, global meta-analyses indicate that the circulation of MRSA in dairy systems associated in livestock- is shaped by a combination of local antimicrobial use policies, milking system infrastructure, and mastitis control programs, rather than by geographic region alone [56]. This suggests that the patterns observed in Ecuador likely reflect production-level factors rather than intrinsic microbial characteristics [57]. In Latin America, mecC remains under-characterized compared with mecA, partly due to historical assay bias towards mecA and limited routine screening; therefore, documenting mecC alongside mecA provides regionally relevant evidence that can inform assay selection in laboratories and guide future source-tracking when resources allow, without over-interpreting the present cross-sectional data [58].

Despite the valuable information obtained in this study on S. aureus as a common contaminant in raw milk and the detection of strains carrying the mecA and mecC genes, the precise impact of this problem, either as a cause of sporadic infections in farmers and consumers or as a factor associated with increased rates of bovine mastitis, is not yet known [59]. Further studies are needed to determine the real risk posed by these circulating strains [60]. Although partial 16S rDNA sequencing confirmed the taxonomic identity of the isolates as S. aureus, this marker is highly conserved and therefore provides limited discriminatory power for resolving phylogenetic structure among strains [61]. Similarly, the partial mecA and mecC sequences analyzed in this study allowed the confirmation of methicillin resistance determinants, but not enabling differentiation at the lineage or clonal complex level [62]. For this reason, only broad genetic relatedness was interpreted. Future work should incorporate sequencing of more variable genomic regions or whole-genome sequencing approaches, allowing higher-resolution phylogenomic analysis and epidemiological tracing of transmission events, particularly in the context of One Health surveillance [63,64]. At the surveillance level, integrating MRSA monitoring in raw milk into national systems would align with international reporting frameworks—WHO/GLASS for antimicrobial resistance, EFSA’s risk-based food-chain monitoring approaches in the EU context, and WOAH guidance for animal-origin AMR data—facilitating comparability and priority-setting without requiring changes to the present study design. Overall, the results of this study emphasize that both detection and control strategies must consider not only pathogen identification but also the management practices that facilitate its persistence in dairy environments [65,66,67,68].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sampling

The sample size required to estimate the prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus in bovine raw milk from Ecuador was calculated using the formula n = (Z2 × Pexp × (1 − Pexp))/d2, assuming an unknown population [69]. In this equation, n represents the number of samples, Pexp the expected prevalence, d the desired absolute precision, and Z the standard normal deviate corresponding to a 95% confidence level (1.96). Following this approach, a total of 633 samples were obtained over one climatic year; 322 from the highland province of Pichincha and 311 from the coastal province of Manabí, in accordance with the NTE ISO 707 standard [70]. Farms were selected using convenience sampling based on producer availability and willingness to participate. Sampling was conducted across the full annual climatic cycle to incorporate potential seasonal variation. No prior filtering based on herd health status was applied, as the goal was to capture naturally occurring prevalence in routine production settings. Producers were classified according to the Ministry Agreement No. 095 [71]: farms with fewer than 50 head of cattle were considered “small producers,” whereas those with 50–200 heads were categorized as “medium producers” (Supplementary Materials). Raw milk samples were collected directly from the bulk cooling tank after agitation to ensure homogenization. In cases where bulk tanks were not available (small producers), milk was collected immediately after milking. Before sampling, teats were cleaned with potable water and then dried, collectors used disposable sterile gloves. Approximately 50 mL of milk was aseptically transferred into sterile screw-cap containers. Milk was collected aseptically into sterile containers, transported under refrigeration (4 °C), and processed upon arrival at the laboratories of Universidad de Las Américas (UDLA). All procedures were performed under the ethical approval of the Committee for the Care and Use of Laboratory and Domestic Animals of AGROCALIDAD (authorization #INT/DA/019 2018-01-31).

4.2. BHI Enrichment and DNA Extraction

The collected bovine milk samples were pre-enriched in Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) broth (D, Sparks, MD, USA; Cat. No. 237500) at a 1:9 sample-to-broth ratio in a final volume of 40 mL. The cultures were incubated at 37 °C with agitation (200 rpm) for approximately 24 h [28]. After incubation, a 1 mL aliquot of the pre-enrichment was taken and subjected to DNA extraction using a Phenol-chloroform based method, using GT reagent according to the previously described protocol [72]. The procedure involved chemical lysis, phase separation, ethanol precipitation, a 70% ethanol wash, and resuspension of the pellet in 30 µL volume with UltraPure™ DNase/RNase-Free Distilled Water (Invitrogen by Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA 92008, USA). The extracted DNA was stored at −20 °C until use.

4.3. Bacteria Isolation

The pre-enrichments were used for the isolation of Staphylococcus aureus. According to ISO 6888-1:2021 standard [73], after incubation the pre-enrichment BHI samples were seeded on Baird Parker Agar plates (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, CA, USA). The inoculated plates were incubated at 37 °C for approximately 19 h; after incubation, black, shiny colonies with clear halos were identified as apparently positive for S. aureus. To extract DNA from the isolates, selected colonies were taken and placed in 200 µL of Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer and the Boiling method was applied [74]. This consists of a thermal cell lysis followed by centrifugation to recover the supernatant containing the bacterial DNA. The extracted DNA was stored at −20 °C until use.

4.4. qPCR for S. aureus Detection

For specific identification of S. aureus, a qPCR assay was performed using previously reported primers and the corresponding hydrolysis probe (Table 2). To determine sensitivity of assay, a standard curve was constructed. For this purpose, the target fragment was first amplified by end-point PCR using only the primers Qnuc-S and Qnuc-AS (Table 2) using the 2× Promega GoTaq Green Master Mix kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After amplicon confirmation, an enzyme purification with ExoZap-IT kit (Applied Biosystems, Santa Clara, CA 95051, USA) was carried. The generated product was inserted into a PCR 2.1-TOPO vector, (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), transformed and cloned into Escherichia coli competent cells according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The Plasmid DNA was extracted from the bacterial culture using the PureLink Quick Plasmid Miniprep Kit (Invitrogen by Thermo Fisher Scientific Baltics UAB Vilnius, Lithuania) following the manufacturer’s instructions. This was used as the basis for standard curve construction. Using the web tool DNA copy number and dilution Calculator (Thermo Fisher Scientific) it was determined the quantity of DNA plasmid necessary to make a first dilution with a known quantity of DNA copies (109 copies), then, serial dilutions in base 10 were performed resulting in a standard curve from 109 copies to 1 plasmid copy numbers. The qPCR assay was performed using 2× of TaqMan™ Universal Master Mix II, with UNG (Applied Biosystems by Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 0.2 µM of each primer, 0.1 µM of hydrolysis probe (Table 2), 1 µL of extracted DNA, and made up to 10 µL volume with UltraPure™ DNase/RNase-Free Distilled Water (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The qPCR protocol was performed using the following temperature conditions: started with an initial denaturation cycle for 5 min, followed for forty cycles heated to 95 °C denaturation for 10 s, 58 °C annealing for 30 s (reading was performed at this step), and 72 °C extension for 30 s; and carried out on the CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). All DNA extracted from pre-enriched samples and isolates were subjected to this qPCR assay in duplicate, incorporating ddH2O as the negative control, dilutions of the previously generated curve as positive control, and a non-template control.

Table 2.

Primers and probes used in this study.

4.5. Identification of mecA and mecC Genes

To detect methicillin resistance, end-point PCR assays targeting the mecA and mecC genes were performed using the primer pairs listed in Table 2. Reactions were prepared using 2× GoTaq Green Master Mix (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), 0.3 µM of each primer, 1 µL of extracted DNA, and UltraPure™ DNase/RNase-free distilled water to a final volume of 10 µL. PCR amplification was carried out following previously reported thermal cycling parameters, and amplification products were separated by electrophoresis and stained using SYBR® Safe DNA gel stain (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Amplicon sizes of 155 bp (mecA) and 106 bp (mecC) were verified using the TrackIt™ 50 bp DNA Ladder (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Isolates positive for either gene were classified as MRSA.

4.6. End Point PCR for 16S rDNA Sequencing

To confirm the identity of the isolates, a subset of 10 randomly selected samples was subjected to amplification of an approximately 1400 bp fragment of the 16S rDNA gene, following the protocol using the primers 27F and 1482R [75]. PCR reactions were performed using 2× GoTaq Green Master Mix (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), 0.3 µM of each primer (Table 2), 2 µL of template DNA, and UltraPure™ DNase/RNase-Free Distilled Water to a final volume of 25 µL. Thermocycling conditions followed standard kit specifications with an annealing step at 55 °C for 30 s. The resulting amplicons were purified using ExoZAP-IT enzyme (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and sequenced using the BigDye® Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit, followed by capillary electrophoresis on an ABI 3500 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The raw data generated were analyzed in Geneious Prime v2024.0.7 (https://www.geneious.com) and aligned with sequences of Staphylococcus species previously deposited in GenBank using CLUSTAL X v2.0 [76], with which a Neighbor-Joining statistics method conduced in MEGA 11 [77], phylogenetic tree was constructed using the p-distance substitution model and phylogeny test bootstrap model with 1000 replicates. The sequences obtained were appropriately uploaded to GenBank and can be found under accession numbers PX525570-PX525578.

4.7. mecA and mecC Sequencing

To validate the veracity of the amplicons generated for mecA and mecC, 5 positive amplicons were randomly taken for each gene, sequenced and analyzed using the conditions previously indicated in the 16S rDNA sequencing section.

4.8. Statistical Analysis

A descriptive analysis was conducted using variables such as province, producer size, qPCR results, and the presence of mecA and mecC in the samples. Data distribution was assessed using a Shapiro–Wilk test, and a Kruskal–Wallis test was performed to determine whether there were significant differences between variables. A cutoff of p ≤ 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. To determine the difference between the pre-enriched milk qPCR and bacterial isolation assays, the Cohen’s Kappa coefficient between the S. aureus detection results of these two methods was calculated. The formula was used to determine the prevalence of the results obtained: Prevalence = (N° of positive cases)/(Total size of the assessed population). All analyses were conducted in RStudio software (version 4.4.0) 1 D

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the significant prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus contamination in raw milk, with a notable detection of methicillin resistance genes (mecA and mecC) among isolates. The high rates of S. aureus and MRSA found, particularly in small and medium-sized dairy operations, point towards deficiencies in hygiene practices and antimicrobial stewardship, which may contribute to the persistence and dissemination of resistant strains. The observed concordance between molecular detection by qPCR and conventional isolation supports the reliability of both methods, indicating that the applied diagnostic approach is appropriate for accurate pathogen monitoring. Furthermore, the detection of mecC—although less frequently reported in South America—underscores the need to strengthen genomic surveillance systems to prevent the silent spread of emerging resistance determinants with zoonotic potential. In view of the findings, it is recommended that priority be given to the following measures as part of a One Health public health framework: the improvement of routine monitoring programs, the reinforcement of milking hygiene, and the promotion of responsible antimicrobial use in livestock production. Future research should include phenotypic antimicrobial resistance profiling and whole-genome sequencing to determine transmission dynamics, virulence characteristics, and the potential impact of these strains on both bovine health and human consumers.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/antibiotics14121255/s1, Data, Standard Curve qPCR and Matrix 16S.

Author Contributions

A.L.-G. Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, formal analysis, Data curation, Writing—original draft; C.S.-C. contributed to the formal analysis, Writing—review and editing; B.P.-T. Methodology, Writing—review and editing; S.S.-P. Validation and Writing—review and editing and L.N. Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Writing—review and editing, Supervision, Project administration, and Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Universidad de Las Américas, Quito—Ecuador (grant numbers: VET.LNN.23.01 and 543.A.XVI.25).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures performed in this study were approved by the Committee for the Care and Use of Domestic and Laboratory Animal Resources of the Agency for Regulation and Phytosanitary and Zoosanitary Control of Ecuador (AGROCALIDAD) under number INT/DA/019 (31 January 2018).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the farmers who provided us with the milk samples and the students from the Universidad Central del Ecuador who helped us with the collection process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| S. aureus | Staphylococcus aureus |

| AMR | Antimicrobial Resistance |

| ABI | Applied Biosystems |

| AGROCALIDAD | Agencia de Regulación y Control Fito y Zoosanitario (Ecuador) |

| BHI | Brain Heart Infusion |

| bp | Base pairs |

| BHQ1 | Black Hole Quencher 1 |

| CA | California |

| CFX96 | CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR System |

| CV | Coefficient of Variation |

| Cq | Quantification Cycle |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| SCCmec | Staphylococcal chromosomal cassette mec |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| qPCR | Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| EFSA | European Food Safety Authority |

| EU | European Union |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| LoD | Limit of Detection |

| LoQ | Limit of Quantification |

| mecA | Methicillin resistance gene A |

| mecC | Methicillin resistance gene C |

| MEGA | Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis |

| MRSA | Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| NCBI | National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| NTC | Non-Template Control |

| PBP2a | Penicillin-Binding Protein 2a |

| Pexp | Expected prevalence |

| rpm | Revolutions per minute |

| Tris | Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane |

| UDLA | Universidad de Las Américas |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| UNG | Uracil-N-glycosylase |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| GLASS | Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System |

| WOAH | World Organisation for Animal Health |

| NGS | Next Generation Sequencing |

References

- Vranješ, A.P.; Popović, M.; Jevtić, M. Raw Milk Consumption and Health. Srp. Arh. Celok. Lek. 2015, 143, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos (INEC) Encuesta de Producción Agropecuaria Continua. Available online: https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/encuesta-superficie-produccion-agropecuaria-continua-2021/ (accessed on 28 September 2024).

- Quigley, L.; O’Sullivan, O.; Stanton, C.; Beresford, T.P.; Ross, R.P.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; Cotter, P.D. The Complex Microbiota of Raw Milk. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 37, 664–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalaby, M.; Reboud, J.; Forde, T.; Zadoks, R.N.; Busin, V. Distribution and Prevalence of Enterotoxigenic Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcal Enterotoxins in Raw Ruminants’ Milk: A Systematic Review. Food Microbiol. 2024, 118, 104405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.Y.C.; Bae, J.S.; Otto, M. Pathogenicity and Virulence of Staphylococcus aureus. Virulence 2021, 12, 547–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lister, J.L.; Horswill, A.R. Staphylococcus aureus Biofilms: Recent Developments in Biofilm Dispersal. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2014, 4, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löffler, B.; Tuchscherr, L. Staphylococcus aureus Toxins: Promoter or Handicap during Infection? Toxins 2021, 13, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowy, F.D. Staphylococcus aureus Infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 339, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abril, A.G.; Villa, T.G.; Barros-Velázquez, J.; Cañas, B.; Sánchez-Pérez, A.; Calo-Mata, P.; Carrera, M. Staphylococcus aureus Exotoxins and Their Detection in the Dairy Industry and Mastitis. Toxins 2020, 12, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassat, J.E.; Thomsen, I. Staphylococcus aureus Infections in Children. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 34, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, S.Y.C.; Davis, J.S.; Eichenberger, E.; Holland, T.L.; Fowler, V.G. Staphylococcus aureus Infections: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, Clinical Manifestations, and Management. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 28, 603–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubukata, K.; Nonoguchi, R.; Matsuhashi, M.; Konno, M. Expression and Inducibility in Staphylococcus aureus of the MecA Gene, Which Encodes a Methicillin-Resistant S. aureus-Specific Penicillin-Binding Protein. J. Bacteriol. 1989, 171, 2882–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.S.; de Lencastre, H.; Garau, J.; Kluytmans, J.; Malhotra-Kumar, S.; Peschel, A.; Harbarth, S. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2018, 4, 18033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, T.; Katayama, Y.; Hiramatsu, K. Cloning and Nucleotide Sequence Determination of the Entire Mec DNA of Pre-Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus N315. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1999, 43, 1449–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Álvarez, L.; Holden, M.T.; Lindsay, H.; Webb, C.R.; Brown, D.F.; Curran, M.D.; Walpole, E.; Brooks, K.; Pickard, D.J.; Teale, C.; et al. Meticillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus with a Novel MecA Homologue in Human and Bovine Populations in the UK and Denmark: A Descriptive Study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2011, 11, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taher, E.M.; Hemmatzadeh, F.; Aly, S.A.; Elesswy, H.A.; Petrovski, K.R. Survival of Staphylococci and Transmissibility of Their Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in Milk after Heat Treatments. LWT 2020, 129, 109584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanal, S.; Boonyayatra, S.; Awaiwanont, N. Prevalence of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Dairy Farms: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 947154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekhloufi, O.A.; Chieffi, D.; Hammoudi, A.; Bensefia, S.A.; Fanelli, F.; Fusco, V. Prevalence, Enterotoxigenic Potential and Antimicrobial Resistance of Staphylococcus aureus and Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Isolated from Algerian Ready to Eat Foods. Toxins 2021, 13, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riva, A.; Borghi, E.; Cirasola, D.; Colmegna, S.; Borgo, F.; Amato, E.; Pontello, M.M.; Morace, G. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Raw Milk: Prevalence, SCCmec Typing, Enterotoxin Characterization, and Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns. J. Food Prot. 2015, 78, 1142–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutu, I.; Lungu, B.C.; Spataru, I.I.; Torda, I.; Iancu, T.; Barrow, P.A.; Mircu, C. Microbiological and Molecular Investigation of Antimicrobial Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus Isolates from Western Romanian Dairy Farms: An Epidemiological Approach. Animals 2024, 14, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabello, R.F.; Bonelli, R.R.; Penna, B.A.; Albuquerque, J.P.; Souza, R.M.; Cerqueira, A.M.F. Antimicrobial Resistance in Farm Animals in Brazil: An Update Overview. Animals 2020, 10, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez López, J.C.; Tovar Cuevas, J.R.; Bergonzoli, G.; Lucumí Moreno, A. Prevalencia Bayesiana de Staphylococcus aureus En Vacas Lecheras En El Valle Del Cauca, Colombia. CES Med. Vet. Zootec. 2021, 16, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, G.K.; Harrison, E.M.; Holmes, M.A. The Emergence of MecC Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Trends Microbiol. 2014, 22, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puga-Torres, B.; Aragón, E.; Contreras, A.; Escobar, D.; Guevara, K.; Herrera, L.; López, N.; Luje, D.; Martínez, M.; Sánchez, L.; et al. Analysis of Quality and Antibiotic Residues in Raw Milk Marketed Informally in the Province of Pichincha—Ecuador. Food Agric. Immunol. 2024, 35, 2291321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puga-Torres, B.; Aragón Vásquez, E.; Ron, L.; Álvarez, V.; Bonilla, S.; Guzmán, A.; Lara, D.; De la Torre, D. Milk Quality Parameters of Raw Milk in Ecuador between 2010 and 2020: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Foods 2022, 11, 3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bano, S.A.; Hayat, M.; Samreen, T.; Asif, M.; Habiba, U.; Uzair, B. Detection of Pathogenic Bacteria Staphylococcus aureus and Salmonella sp. from Raw Milk Samples of Different Cities of Pakistan. Nat. Sci. 2020, 12, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirci, M.; Yigin, A.; Altun, S.; Uysal, H.; Saribas, S.; Kocazeybek, B. Salmonella Spp. and Shigella Spp. Detection via Multiplex Real-Time PCR and Discrimination via MALDI-TOF MS in Different Animal Raw Milk Samples. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2019, 22, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, T.; Suo, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, D.; Ye, X.; Chen, S.; Zhao, Y. A Multiplex RT-PCR Assay for S. aureus, L. Monocytogenes, and Salmonella Spp. Detection in Raw Milk with Pre-Enrichment. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucey, J.A. Raw Milk Consumption. Nutr. Today 2015, 50, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre, A.A.; Pachá, P.A.; González-Rocha, G.; San Martín, I.; Quezada-Aguiluz, M.; Aguayo-Reyes, A.; Bello-Toledo, H.; Oliva, R.; Estay, A.; Pugin, J.; et al. On-Farm Surfaces in Contact with Milk: The Role of Staphylococcus aureus-Containing Biofilms for Udder Health and Milk Quality. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2020, 17, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botaro, B.G.; Cortinhas, C.S.; Março, L.V.; Moreno, J.F.G.; Silva, L.F.P.; Benites, N.R.; Santos, M.V. Detection and Enumeration of Staphylococcus aureus from Bovine Milk Samples by Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 6955–6964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aklilu, E.; Chia, H.Y. First MecC and MecA Positive Livestock-Associated Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MecC MRSA/LA-MRSA) from Dairy Cattle in Malaysia. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupieux, C.; Bouchiat, C.; Larsen, A.R.; Pichon, B.; Holmes, M.; Teale, C.; Edwards, G.; Hill, R.; Decousser, J.-W.; Trouillet-Assant, S.; et al. Detection of MecC-Positive Staphylococcus aureus: What to Expect from Immunological Tests Targeting PBP2a? J. Clin. Microbiol. 2017, 55, 1961–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touaitia, R.; Ibrahim, N.A.; Touati, A.; Idres, T. Staphylococcus aureus in Bovine Mastitis: A Narrative Review of Prevalence, Antimicrobial Resistance, and Advances in Detection Strategies. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titouche, Y.; Akkou, M.; Houali, K.; Auvray, F.; Hennekinne, J. Role of Milk and Milk Products in the Spread of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the Dairy Production Chain. J. Food Sci. 2022, 87, 3699–3723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nhatsave, N.; Garrine, M.; Messa, A.; Massinga, A.J.; Cossa, A.; Vaz, R.; Ombi, A.; Zimba, T.F.; Alfredo, H.; Mandomando, I.; et al. Molecular Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus Isolated from Raw Milk Samples of Dairy Cows in Manhiça District, Southern Mozambique. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomao, P.; Pirolo, M.; Agnoletti, F.; Pantosti, A.; Battisti, A.; Di Martino, G.; Visaggio, D.; Monaco, M.; Franco, A.; Pimentel de Araujo, F.; et al. Molecular Epidemiology of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus from Dairy Farms in North-Eastern Italy. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 332, 108817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, X.; Cai, H.; Huang, S.; Ni, Y.; Luo, B.; Qian, H.; Ji, H.; Wang, X. Prevalence and Characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus Isolated from Retail Raw Milk in Northern Xinjiang, China. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 705947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deddefo, A.; Mamo, G.; Leta, S.; Amenu, K. Prevalence and Molecular Characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus in Raw Milk and Milk Products in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Food Contam. 2022, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchini, A. Recent Developments in Phenotypic and Molecular Diagnostic Methods for Antimicrobial Resistance Detection in Staphylococcus aureus: A Narrative Review. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, D.M.; Wieland, B.; Knight, G.M.; Lines, J.; Naylor, N.R. The Effectiveness of Biosecurity Interventions in Reducing the Transmission of Bacteria from Livestock to Humans at the Farm Level: A Systematic Literature Review. Zoonoses Public Health 2021, 68, 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanardi, G.; Caminiti, A.; Delle Donne, G.; Moroni, P.; Santi, A.; Galletti, G.; Tamba, M.; Bolzoni, G.; Bertocchi, L. Short Communication: Comparing Real-Time PCR and Bacteriological Cultures for Streptococcus Agalactiae and Staphylococcus aureus in Bulk-Tank Milk Samples. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 5592–5598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO. Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Enumeration of Coagulase-Positive Staphylococci (Staphylococcus aureus and Other Species)—Part 1: Technique Using Baird-Parker Agar Medium; International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.-W.; Wang, L.-J. Impact of Culture Media and Sampling Methods on Staphylococcus aureus Aerosols. Indoor Air 2015, 25, 488–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graber, H.U.; Casey, M.G.; Naskova, J.; Steiner, A.; Schaeren, W. Development of a Highly Sensitive and Specific Assay to Detect Staphylococcus aureus in Bovine Mastitic Milk. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 4661–4669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molineri, A.I.; Signorini, M.L.; Cuatrín, A.L.; Canavesio, V.R.; Neder, V.E.; Russi, N.B.; Bonazza, J.C.; Calvinho, L.F. Association between Milking Practices and Psychrotrophic Bacterial Counts in Bulk Tank Milk. Rev. Argent. Microbiol. 2012, 44, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Facundo, G.B.A.; Maquen, J.A.R.; Calderón, N.U.; Espinoza-Montes, F. Effect of Hygiene on Milk Quality and Milking Factors of Small Andean Herds during the Rainy Season. World’s Vet. J. 2024, 14, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kümmel, J.; Stessl, B.; Gonano, M.; Walcher, G.; Bereuter, O.; Fricker, M.; Grunert, T.; Wagner, M.; Ehling-Schulz, M. Staphylococcus aureus Entrance into the Dairy Chain: Tracking S. aureus from Dairy Cow to Cheese. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalayu, A.A.; Woldetsadik, D.A.; Woldeamanuel, Y.; Wang, S.-H.; Gebreyes, W.A.; Teferi, T. Burden and Antimicrobial Resistance of S. aureus in Dairy Farms in Mekelle, Northern Ethiopia. BMC Vet. Res. 2020, 16, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butaye, P.; Argudín, M.A.; Smith, T.C. Livestock-Associated MRSA and Its Current Evolution. Curr. Clin. Microbiol. Rep. 2016, 3, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, H.; Howard, J.; Elvy, J.; Campbell, P.; Anderson, T.; Bakker, S.; Eustace, A.; Perez, H.; Winter, D.; Dyet, K. Genomic Epidemiology of MecC-Carrying Staphylococcus aureus Isolates from Human Clinical Cases in New Zealand. Access Microbiol. 2024, 6, 000849.v2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankhomwa, J.; Tolhurst, R.; M’biya, E.; Chikowe, I.; Banda, P.; Mussa, J.; Mwasikakata, H.; Simpson, V.; Feasey, N.; MacPherson, E.E. A Qualitative Study of Antibiotic Use Practices in Intensive Small-Scale Farming in Urban and Peri-Urban Blantyre, Malawi: Implications for Antimicrobial Resistance. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 876513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sineke, N.; Asante, J.; Amoako, D.G.; Abia, A.L.K.; Perrett, K.; Bester, L.A.; Essack, S.Y. Staphylococcus aureus in Intensive Pig Production in South Africa: Antibiotic Resistance, Virulence Determinants, and Clonality. Pathogens 2021, 10, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, Z.; Lopez-Benavides, M.; Gentilini, M.B.; Ruegg, P.L. Impact of Training Dairy Farm Personnel on Milking Routine Compliance, Udder Health, and Milk Quality. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 1615–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puga-Torres, B.; Vera-Mendieta, M.D. Factors Associated with the Presence of Antibiotic Residues in Raw Milk from Cows in the Canton of El Carmen, Manabí, Ecuador. Rev. Med. Vet. Zoot. 2025, 72, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetsch, A.; Etter, D.; Johler, S. Livestock-Associated Meticillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus—Current Situation and Impact from a One Health Perspective. Curr. Clin. Microbiol. Rep. 2021, 8, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- More, S.J.; McAloon, C.; Silva Boloña, P.; O’Grady, L.; O’Sullivan, F.; McGrath, M.; Buckley, W.; Downing, K.; Kelly, P.; Ryan, E.G.; et al. Mastitis Control and Intramammary Antimicrobial Stewardship in Ireland: Challenges and Opportunities. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 748353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Machado, C.; Capita, R.; Alonso-Calleja, C. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in Dairy Products and Bulk-Tank Milk (BTM). Antibiotics 2024, 13, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.; Godden, S.M.; Royster, E.E.; Crooker, B.A.; Johnson, T.J.; Smith, E.A.; Sreevatsan, S. Prevalence, Antibiotic Resistance, Virulence and Genetic Diversity of Staphylococcus aureus Isolated from Bulk Tank Milk Samples of U.S. Dairy Herds. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lienen, T.; Schnitt, A.; Hammerl, J.A.; Maurischat, S.; Tenhagen, B.-A. Genomic Distinctions of LA-MRSA ST398 on Dairy Farms from Different German Federal States with a Low Risk of Severe Human Infections. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 575321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassler, H.B.; Probert, B.; Moore, C.; Lawson, E.; Jackson, R.W.; Russell, B.T.; Richards, V.P. Phylogenies of the 16S RRNA Gene and Its Hypervariable Regions Lack Concordance with Core Genome Phylogenies. Microbiome 2022, 10, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manara, S.; Pasolli, E.; Dolce, D.; Ravenni, N.; Campana, S.; Armanini, F.; Asnicar, F.; Mengoni, A.; Galli, L.; Montagnani, C.; et al. Whole-Genome Epidemiology, Characterisation, and Phylogenetic Reconstruction of Staphylococcus aureus Strains in a Paediatric Hospital. Genome Med. 2018, 10, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chieffi, D.; Fanelli, F.; Cho, G.-S.; Schubert, J.; Blaiotta, G.; Franz, C.M.A.P.; Bania, J.; Fusco, V. Novel Insights into the Enterotoxigenic Potential and Genomic Background of Staphylococcus aureus Isolated from Raw Milk. Food Microbiol. 2020, 90, 103482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, J.R.; Didelot, X.; Crook, D.W.; Llewelyn, M.J.; Paul, J. Whole Genome Sequencing in the Prevention and Control of Staphylococcus aureus Infection. J. Hosp. Infect. 2013, 83, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbehiry, A.; Marzouk, E.; Abalkhail, A.; Edrees, H.M.; Ellethy, A.T.; Almuzaini, A.M.; Ibrahem, M.; Almujaidel, A.; Alzaben, F.; Alqrni, A.; et al. Microbial Food Safety and Antimicrobial Resistance in Foods: A Dual Threat to Public Health. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Organisation for Animal Healt. Towards a Healthier Future for All—AMR Progress Report; WOAH: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Manual for Reporting 2024 Antimicrobial Resistance Data under the Framework of Food-Producing Animals and Foodstuffs Derived Therefrom. In Global Antibiotic Resistance Surveillance Report 2025; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Antibiotic Resistance Surveillance Report 2025; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Dharmarajan, S.; Lee, J.; Izem, R. Sample Size Estimation for Case-crossover Studies. Stat. Med. 2019, 38, 956–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Ecuatoriano de Normalización (INEN). NTE INEN ISO 707: Leche y Productos Lácteos. Orientaciones Para El Muestreo (ISO 707:2008, IDT); Instituto Ecuatoriano de Normalización (INEN): Quito, Ecuador, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Agricultura y Ganaderia (MAG) Acuerdo Ministerial No. 095. Available online: https://www.agricultura.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/ACUERDO-095-2021-1.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Green, M.R.; Sambrook, J. Isolation of High-Molecular-Weight DNA Using Organic Solvents. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2017, 2017, pdb.prot093450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 6888-1:2021/Amd 1:2023; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Enumeration of Coagulase-Positive Staphylococci (Staphylococcus aureus and Other Species)—Part 1: Method Using Baird-Parker Agar Medium. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Dashti, A.A.; Dashti, H. Heat Treatment of Bacteria: A Simple Method of DNA Extraction for Molecular Techniques. Kuwait Med. J. 2009, 41, 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, J.A.; Reich, C.I.; Sharma, S.; Weisbaum, J.S.; Wilson, B.A.; Olsen, G.J. Critical Evaluation of Two Primers Commonly Used for Amplification of Bacterial 16S RRNA Genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 2461–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, M.A.; Blackshields, G.; Brown, N.P.; Chenna, R.; McGettigan, P.A.; McWilliam, H.; Valentin, F.; Wallace, I.M.; Wilm, A.; Lopez, R.; et al. Clustal W and Clustal X Version 2.0. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 2947–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).